1. Introduction

Modern smart manufacturing that complies with Industry 5.0 practices emphasizes proactive quality control, zero-defect production, and waste reduction by leveraging AI and IoT in human-centric environments [

1,

2]. In principle, this framework is visible in the emerging Quality 5.0 paradigm, which integrates advanced technologies with sustainability and stakeholder-oriented strategies to achieve resilient and intelligent manufacturing processes [

3,

4]. Moreover, zero defect manufacturing and zero waste strategies are increasingly crucial in high volume industries, aiming to minimize defects and waste through advanced, sustainable approaches [

5]. As a result, industrial quality inspection has widely adopted automatic optical inspection (AOI) and machine vision technologies, with AOI being especially transformative in electronics production by offering rapid and accurate automatic detection of defects and proper quality control [

6]. Similarly, in steel manufacturing, computer vision systems enable continuous monitoring of surface defects, such as cracks, with high precision at production speeds [

7].

Several reports confirm the extensive adoption of camera-based defect detection over various manufacturing and industrial domains. For example, automated visual inspection (AVI) has been widely adopted as a solution for quality inspection, resulting in enhancing performance, efficiency, profitability and product quality [

8,

9]. However, entirely vision-based methods face challenges with complex surface modeling and often lack the accuracy and speed necessary for practical use, particularly for detecting 3D or subsurface anomalies [

10]. These limitations can increase the risk of incorrectly rejecting parts that are indeed acceptable, and in some cases, they can lead to unwanted scrapping of partially good products.

Many advanced non-contact inspection technologies, such as laser triangulation sensors, play a pivotal role in modern manufacturing quality control. These sensors provide high-precision, non-contact measurements of component surfaces and dimensions, which facilitate the detection of even small defects that traditional contact gauges or 2D vision methods might ignore [

11]. Furthermore, the deployment of in-line laser-based sensors helps increase inspection accuracy and efficiency, which ultimately ensures that only really defective parts are flagged for rejection. This high precision solution reduces false rejects and prevents unnecessary processing or scrapping of acceptable products, hence saving material and energy that would otherwise be wasted [

12]. Noteworthy is that the adoption of sensor-based inspection supports broader sustainability goals, where implementing non-destructive, in-line inspection systems can significantly reduce material waste and resource consumption during production, which directly contributes to more sustainable, “zero-waste” manufacturing practices [

5]. This approach aligns quality improvement with environmental responsibility, as early defect removal conserves valuable materials and reduces scrap.

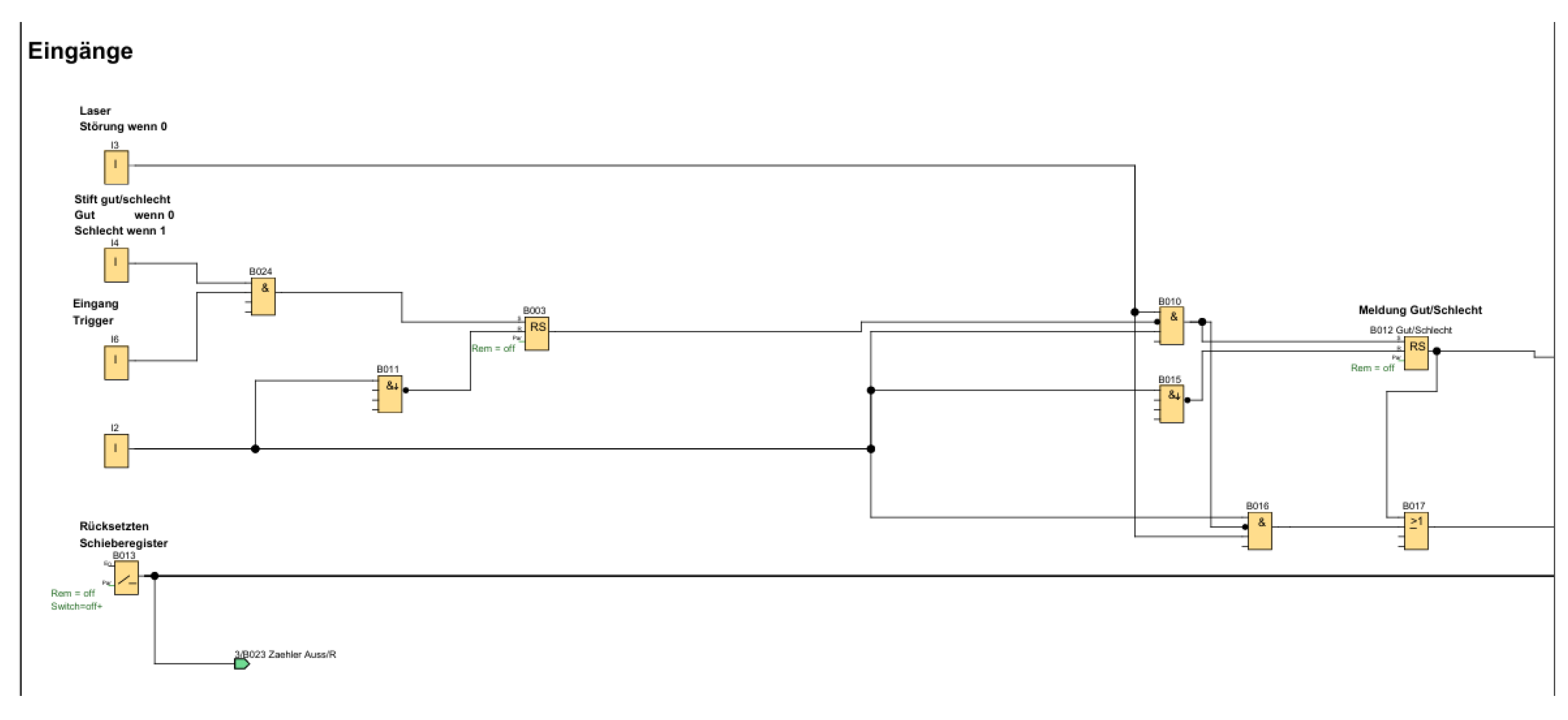

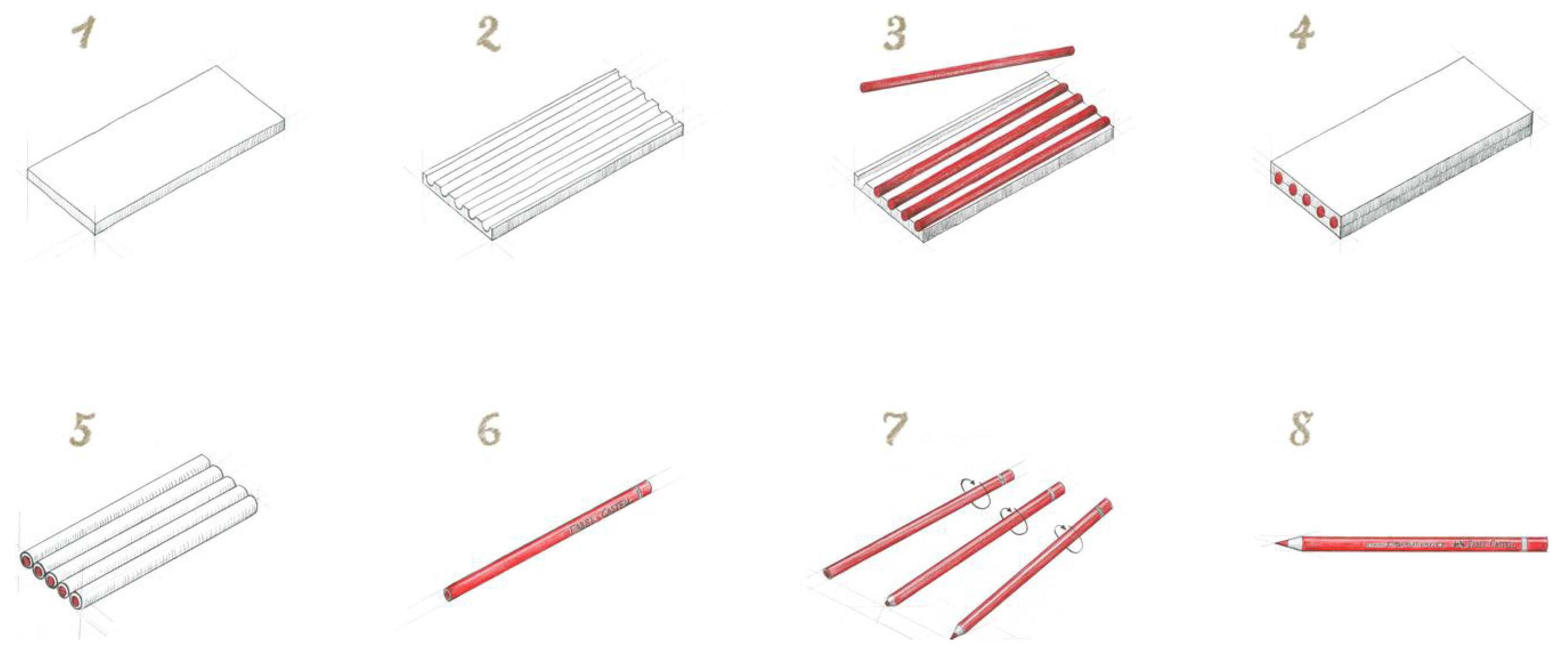

In pencil manufacturing, a specific quality problem illustrates these challenges. Wooden slats are machined with grooves and filled with graphite leads (i.e., usually 7–10 per slat) which are later bonded and cut into individual pencils.

Figure 1 illustrates the general pencil manufacturing process at Faber-Castell. Due to minor dimensional variability in the lead placement machinery and occasional bent or fractured leads, a small percentage (i.e., less than 1%) of slats end up missing one or more leads [

13]. At the slat stage, optical vision systems are frequently employed to identify slats with missing leads, enabling the disposal of all pencils from defective slats prior to additional processing. This ensures defective pencils do not reach consumers but leads to substantial material waste, as both the missing lead and the remaining intact leads and wood from the slat are wasted. Annually, a small but significant fraction of slats may have one or more missing leads. This results in the disposal of hundreds of thousands of otherwise usable products, representing substantial material and economic loss. This approach is not considered the most environmentally or economically sustainable solution and conflicts with Faber-Castell’s sustainability commitments and broader sustainability initiatives, such as the EU “zero-waste” goals and corporate sustainability commitments, thereby motivating the development of a more detailed inspection approach.

This study aims to develop an inline inspection system capable of detecting and eliminating defective pencils (i.e., pencils with missing or recessed leads) once the slat has been divided, thus preserving the unaffected pencils. By intercepting defective units at the pencil level, material waste is expected to be significantly reduced, while high product quality is maintained. This solution is designed to operate at up to ∼180 pencils/min and integrate into the existing process flow without causing slowdowns. A solution utilizing a laser triangulation sensor for high-precision, non-contact measurement of each pencil’s end profile was sought. Laser profile scanning can capture minute geometric differences, such as a missing or sunken lead, that 2D cameras might miss or misinterpret [

11]. Previous studies have applied laser scanning in industrial inspection for similar reasons. For example, 3D laser triangulation was used to detect subtle surface anomalies in tires that were invisible to traditional imaging [

14], and multi-line laser scanners are common in high-speed dimensional measurement tasks [

11]. Compared to a full vision system, a laser sensor-based approach can be simpler to calibrate for depth measurements and less sensitive to color or lighting variations [

15], which is advantageous given the dark graphite and wood colors in pencils.

In the following, the development and evaluation of the proposed laser-based pencil inspection system are presented. A structured methodology was adhered to in the design process, in accordance with VDI2221 guidelines for engineering design [

16], encompassing an analysis of requirements, the formulation of various solution concepts, and the selection of the optimal concept using weighted criteria. The adopted solution was prototyped and tested under conditions that replicate factory throughput. The paper details the system architecture, including the configuration of the laser sensor and real-time control logic for defect detection and rejection. It also presents the findings which illustrate the detection accuracy and false rejection rate of the system and analyze how these results substantiate the proposed methodology. Lastly, the paper evaluates the system’s economic viability and its conformity with overarching smart manufacturing trends. The deployment leads to a considerable decrease in material waste and ensures a swift return on investment, as elaborated in

Section 4, thus offering a tangible step forward in achieving “zero-defect, zero-waste” manufacturing within the pencil production sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design Approach and System Overview

The development of the system was conducted following a systematic design methodology consistent with VDI2221/2222 engineering design standards [

16].

Figure 2 outlines the design process. Key functional requirements and constraints were first defined, considering both technical performance and production integration aspects. Next, multiple conceptual solutions for defect detection and rejection were generated and evaluated against the requirements. A morphological analysis was used to explore different combinations of sensing and actuation principles. For example, we considered concepts based on (A) camera vision with image processing, (B) infrared or time-of-flight distance sensors in multiple zones, and (C) laser triangulation profiling. Each concept was assessed for expected detection accuracy, reaction speed, integration complexity, and cost. A weighted scoring matrix; including technical and economic criteria was applied to quantitatively compare the concepts. The structured design methodology was used to ensure industrial applicability and measurement robustness. The system follows established principles of inline sensor-based metrology, integrating non-contact triangulation sensing directly into the production flow to maintain full line speed and geometric accuracy [

17]. The design also aligns with modern automated-inspection practices that prioritise real-time, in-line measurement to reduce setup complexity and avoid process interruptions [

18]. The selected architecture of laser displacement sensors with a dynamic region of interest, was selected based on accuracy, throughput, cost, and integration requirements, ensuring suitability for high-speed pencil manufacturing.

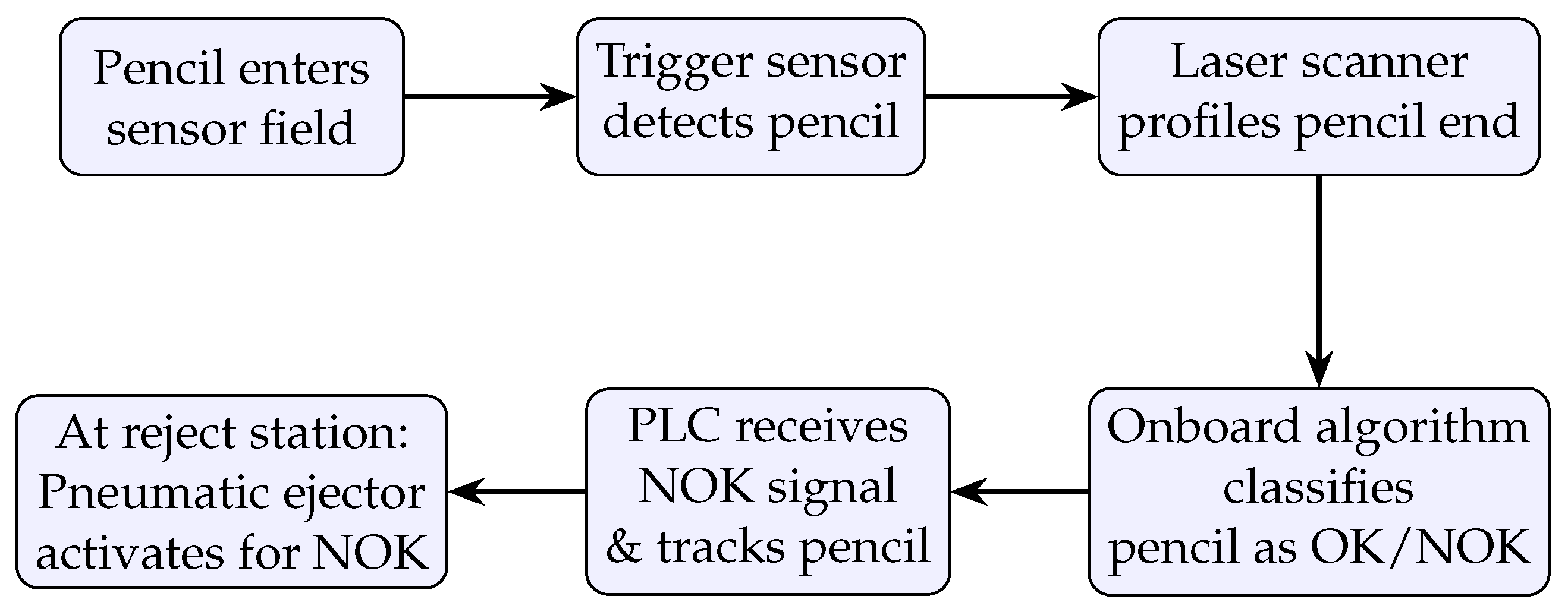

The laser triangulation-based concept emerged as the top solution, due to its high sensitivity to the geometric defect (i.e., missing lead) and robust performance at high speed, combined with relatively low cost and straightforward integration with the existing line. This concept was therefore selected for prototyping and detailed design. This system concept consists of an inline sensor module and an automatic rejection module, integrated around a section of the pencil conveyor. The overall system workflow is summarized in the block diagram in

Figure 3. It illustrates the control and signal flow from initial pencil detection through defect classification and actuator triggering, providing a clear step-by-step view of the inspection cycle.

The detection module uses a 2D laser line profile scanner mounted above the conveyor to scan the frontal cross-section of each pencil as it passes underneath. A laser line is projected vertically across the pencil’s end face, and the reflected profile is captured by the sensor’s internal camera via triangulation. This yields a high-resolution height profile of the pencil end, from which the presence or absence of the graphite core can be determined. The sensor is configured to internally evaluate each profile and output a discrete OK/NOK signal in real time; indicating whether the pencil is good or defective. Supporting sensors are included for precise triggering and tracking: a photoelectric trigger sensor detects when a pencil is exactly under the laser line, and a second sensor (i.e., encoder/counter) tracks conveyor movement to keep count of pencil positions.

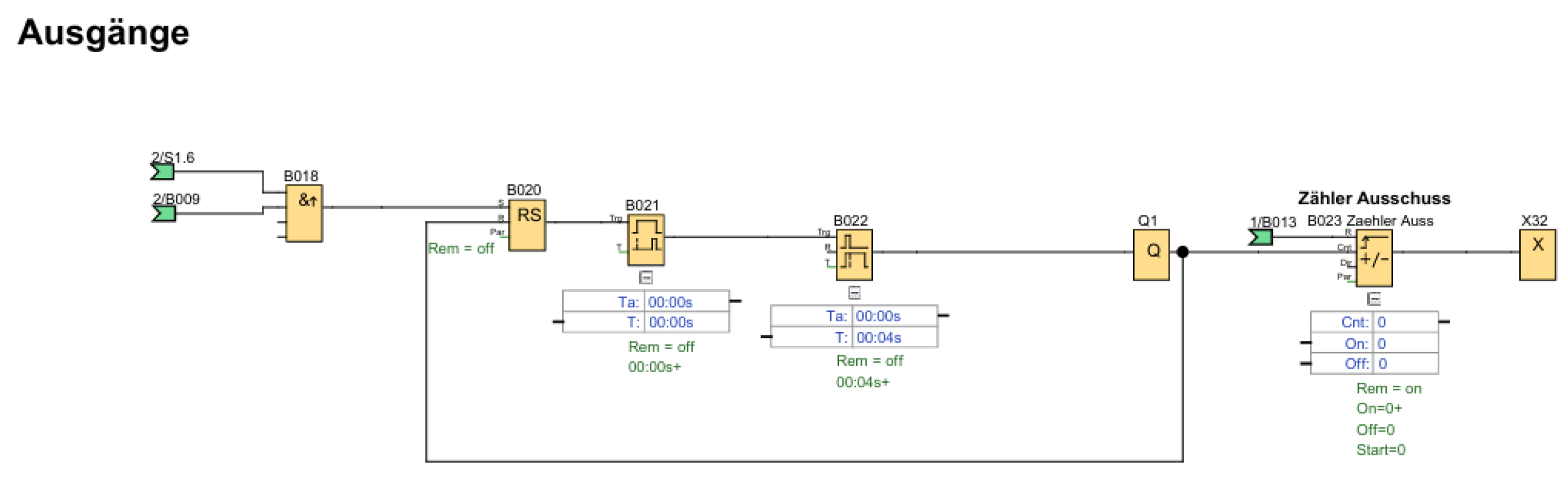

The rejection module is a pneumatic pusher positioned downstream, timed to fire and push a defective pencil into a reject bin when signaled. A compact PLC coordinates the system: it collects the trigger sensor input, reads the laser sensor’s OK/NOK output for each pencil, and activates the pneumatic cylinder at the correct time to eject defective pencils. The PLC uses a shift-register technique to associate the sensor’s classification with the corresponding physical pencil as it travels from the scanning point to the ejection point. The overall result is that any pencil identified with a missing or recessed lead is automatically removed from the moving line, while all good pencils continue unaffected.

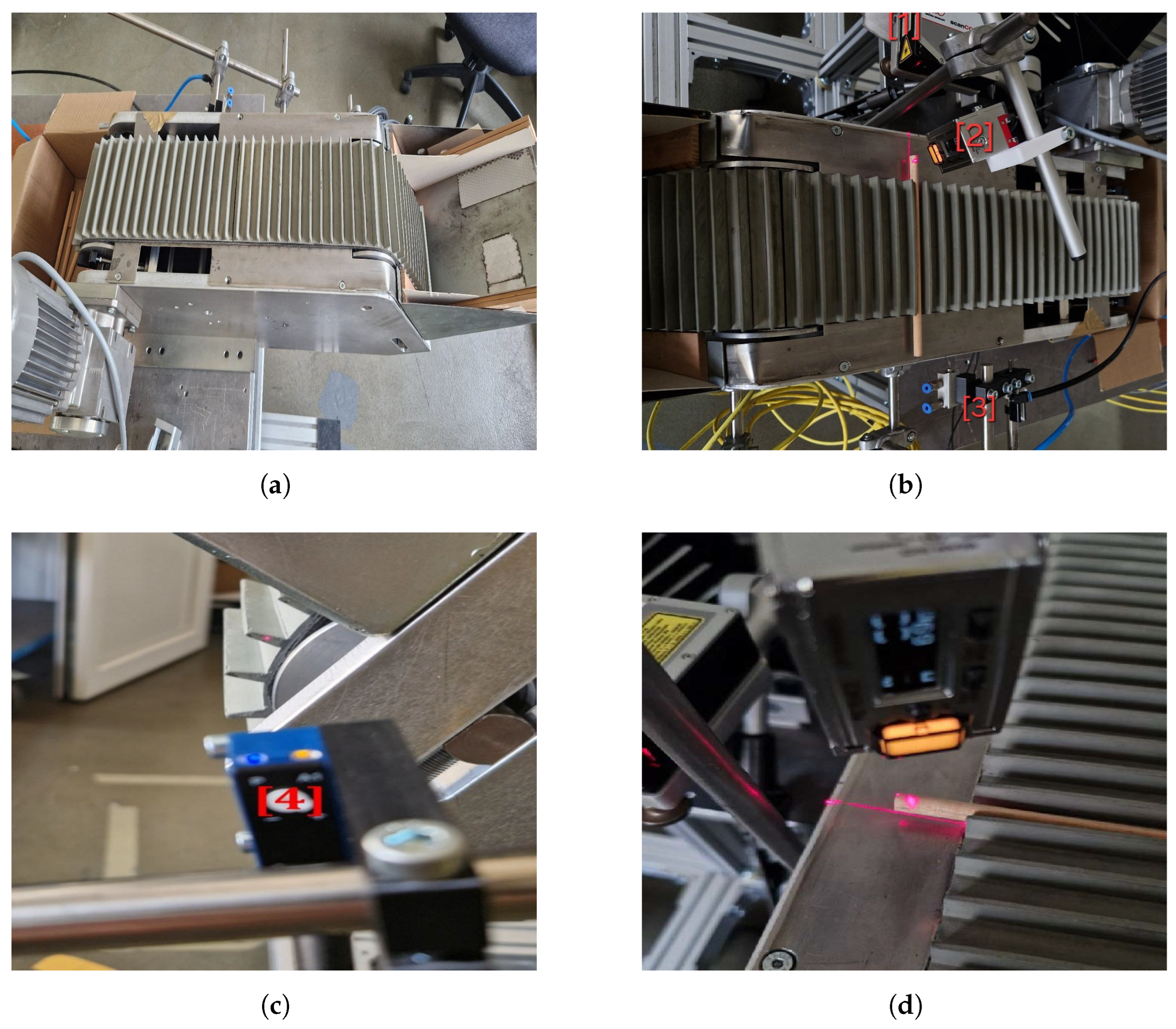

Figure 4 shows the prototype implementation on a test conveyor.

2.2. Hardware Components and Configuration

2.2.1. Laser Profile Sensor

A Micro-Epsilon scanCONTROL LLT25xx-25 2D laser triangulation sensor (Micro-Epsilon GmbH, Ortensburg, Germany) was used as the primary detection unit. It emits a 658 nm red Class 2 laser line to capture cross-sectional profiles, enabling high-resolution measurement of the pencil tip geometry. This wavelength is standard for triangulation sensors and was found to be well suited to the application, producing stable and accurate profiles on both wood and graphite surfaces. The sensor has a vertical range of 25 mm, a height resolution of 2 µm and a 25 mm lateral field of view across 640 data points. Operating at up to 2 kHz, it meets the speed requirements of the conveyor system. The sensor features onboard evaluation with direct binary output (pass/fail), eliminating the need for external processing. It was mounted above the conveyor at an optimal 70–120 mm distance using a custom adjustable bracket, allowing precise alignment across the pencil diameter. Sensor settings were adjusted for material reflectivity (HDR mode) and exposure, while ROIs were defined to focus on the lead groove. Dynamic tracking ensured robust detection despite lateral position shifts. Each pencil’s profile is captured and processed in 0.5 ms to detect missing or recessed leads.

2.2.2. Trigger and Counter Sensors

Two optical sensors were integrated for timing and position tracking. A Keyence LR-TB5000CL diffuse laser sensor, mounted above the conveyor (refer to

Figure 4, item [2]), served as a trigger to detect the presence of a pencil beneath the laser scanner. This ensured profile capture at the correct moment, aligned with the pencil’s end face. A custom holder maintained precise alignment with the laser line. A Wenglor P1KH008 retro-reflective sensor, positioned below the conveyor, acted as a position counter by detecting each slotted holder carrying a pencil. Each detection generated a pulse used to track pencil positions and implement a shift register in the PLC logic. This maintained alignment between scanned data and physical pencil locations. Both sensors interfaced with the PLC’s digital inputs, with the trigger sensor also connected directly to the scanner’s external trigger for hardware-level synchronization.

2.2.3. PLC Controller

A Siemens LOGO! 24CE (24 V DC) programmable logic controller was employed as the main control unit. It features 8 digital inputs, which are sufficient for handling trigger, counter, and sensor output signals, and 4 digital outputs to control actuators. The control program was developed in Siemens LOGO! Soft Comfort V8 using ladder logic. The PLC performs three main functions: (1) reading the laser sensor’s classification output via its digital interface, (2) buffering and synchronizing these outputs with physical pencil positions using pulses from the counter sensor, and (3) triggering the pneumatic ejector at the appropriate moment when a defective pencil reaches the rejection zone. The unit was selected for its real-time reliability, straightforward integration, and compatibility with the sensor’s digital bus coupler. The implemented control logic is further detailed in

Section 2.3.

2.2.4. Sensor Interface Module

To enable discrete communication between the laser sensor and the PLC, a Micro-Epsilon scanCONTROL Output Unit (bus coupler) was employed. This module converts the sensor’s internal evaluation into up to eight digital outputs readable by the PLC. In our setup, it was configured to output a single NOK signal (logic high upon defect detection) along with necessary handshake signals. This arrangement offloads data processing from the PLC, as the sensor performs onboard evaluation using a preconfigured program (via Micro-Epsilon’s Configuration Tools 6.9.2), and the output unit transmits a simple binary pass/fail result. This ensures fast, deterministic operation without requiring the PLC to handle raw profile data.

2.2.5. Pneumatic Ejection System

The rejection mechanism uses a compact pneumatic cylinder (Festo DSNU-10-30-P-A, 10 mm bore, 30 mm stroke) controlled by a solenoid valve (Festo CPE14-M1BH-5L-1/8). Mounted horizontally, the cylinder ejects defective pencils sideways into a rejection chute. Pneumatics were chosen for their high speed and simplicity, with the cylinder capable of extending in milliseconds, that is suitable for line speeds exceeding 180 parts/min. The 24 V DC solenoid valve connects to a 6 bar compressed air supply and is driven by a PLC output. It triggers the cylinder extension, followed by automatic spring-return retraction upon deactivation. The setup ensures accurate and isolated ejection of only the defective pencil, leaving adjacent items undisturbed.

Festo components were selected to match existing factory systems, easing maintenance and integration. The ejector was installed six pencil slots downstream of the laser scanner, corresponding to a predefined time delay that gives the PLC sufficient time to process the defect signal and actuate the cylinder precisely. All components were tested on a conveyor loop simulating a production line layout (refer to

Figure 4), enabling validation of speed, alignment, and timing before deployment.

2.3. Detection Logic and Signal Processing

A key innovation of the system is that the laser profile sensor performs real-time defect evaluation internally, eliminating the need for external data processing. Using the sensor’s configuration software, four custom measurement programs were implemented to analyze each scanned pencil profile for signs of missing or recessed leads. These programs run sequentially and their outputs are combined through logical conditions to produce a final binary classification (good/defective). The measurement functions were as follows:

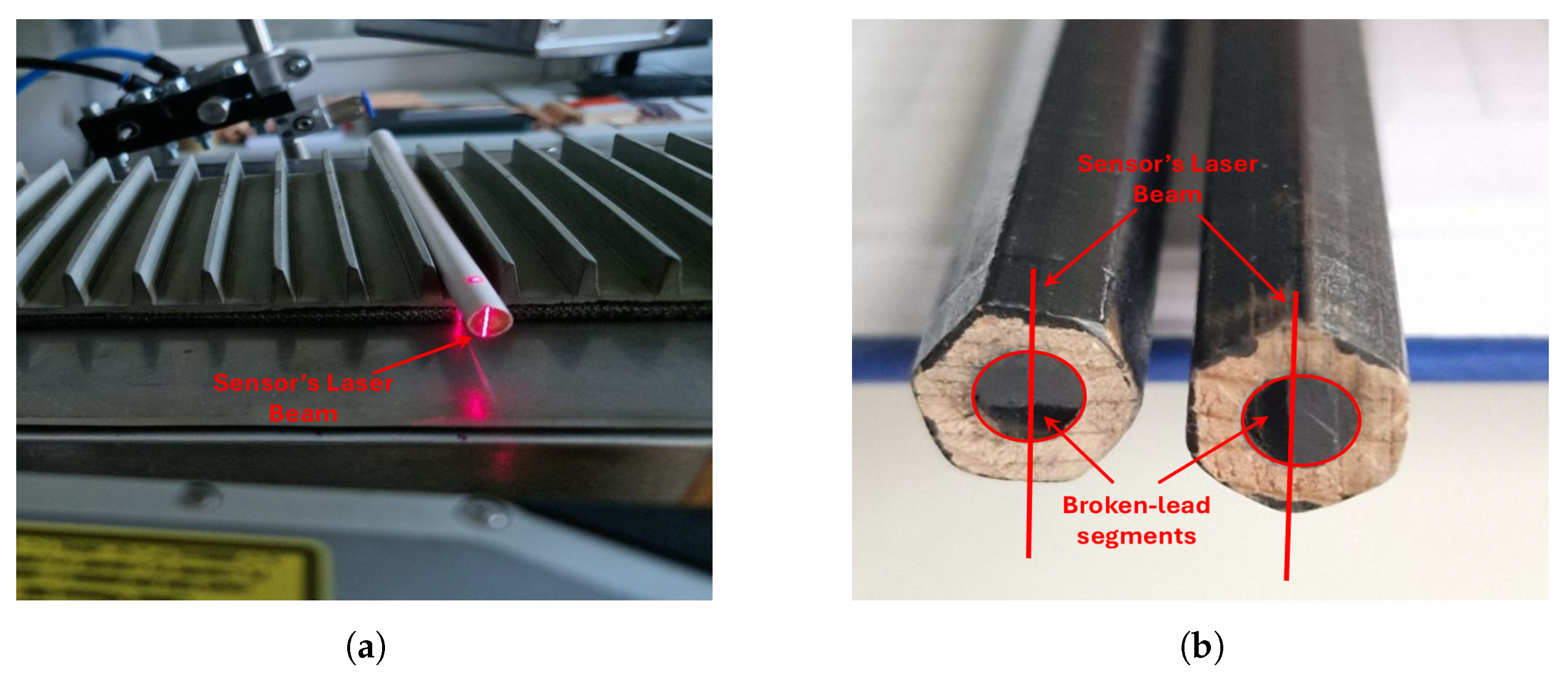

Lead Presence (Depth) Check: It measures the vertical distance between the highest point on the pencil’s wood surface and the lowest point in the groove, where the lead tip is expected (see

Figure 5a). If this depth exceeds a threshold (approximately 2.0 mm), the lead is considered recessed or missing, and the pencil is flagged as defective. The laser sensor computes the recess depth

D as the vertical distance between the pencil’s surface plane and the deepest point in the groove, formally:

Groove Width (Gap) Check: It measures the horizontal width of the groove at the pencil’s end face. Within a region of interest anchored to the pencil edge, the sensor identifies the gap where the lead should be. A properly placed lead nearly fills the cavity, while a missing lead results in a noticeably wider gap. If the measured width exceeds a defined threshold, the pencil is flagged as defective (see

Figure 5b). The groove width

W is computed as the horizontal span at the surface level between the detected left and right groove edges:

Profile Deviation Check: It evaluates the shape of the groove bottom by analyzing the distribution of profile points within the expected lead region. The sensor counts the number of points that rise above a defined height threshold, indicating the presence of lead material. It also checks for abnormal point patterns—such as scattered or irregular shapes—instead of a smooth or flat profile. If the region lacks sufficient elevated points or exhibits unusual deviations, the pencil is flagged as defective (see

Figure 5c, where red points highlight the groove profile).

Measurement Validity Check: It verifies the reliability of each sensor reading by ensuring the full profile was captured without dropout—such as from reflectivity issues or absence of a pencil. The sensor’s firmware provides a status flag for each measurement, which is used to validate data integrity before further processing.

Thresholds were defined based on the nominal pencil core diameter and refined through calibration. In the system, a threshold of 2.0 mm is applied for both depth and width. Any pencil with mm or mm is flagged as defective and rejected accordingly. These measurement programs define each defect category in operational terms: for example, a ‘missing or recessed lead’ corresponds to a groove depth exceeding 2.0 mm, while an abnormally wide groove (i.e., typically larger than 2.0 mm) suggests absence of the graphite core. This embedded evaluation logic serves as the basis for our sample classification and supports robust detection across a range of pencil geometries.

These criteria were combined logically using the sensor’s on-board “digital output logic” configuration. Essentially, the sensor outputs a NOK (bad) signal if any of the geometric checks indicate a defect, after certain gating conditions. Specifically, in our setup the final defect signal was triggered if the groove depth or profile deviation criteria were met, and simultaneously the gap width criterion was met in a preceding stage, to avoid noise. This was implemented as an

OR–

AND logic chain distributed over two digital output channels (refer to

Figure 6). In short, the sensor was tuned such that a pencil is classified defective if the laser profile shows a deep and wide groove (i.e., consistent with a missing or sunken lead) or other abnormal geometry, whereas any pencil that presents a normal lead profile (i.e., shallow groove, narrow gap) returns an OK. This processing all occurs within a few milliseconds on the device.

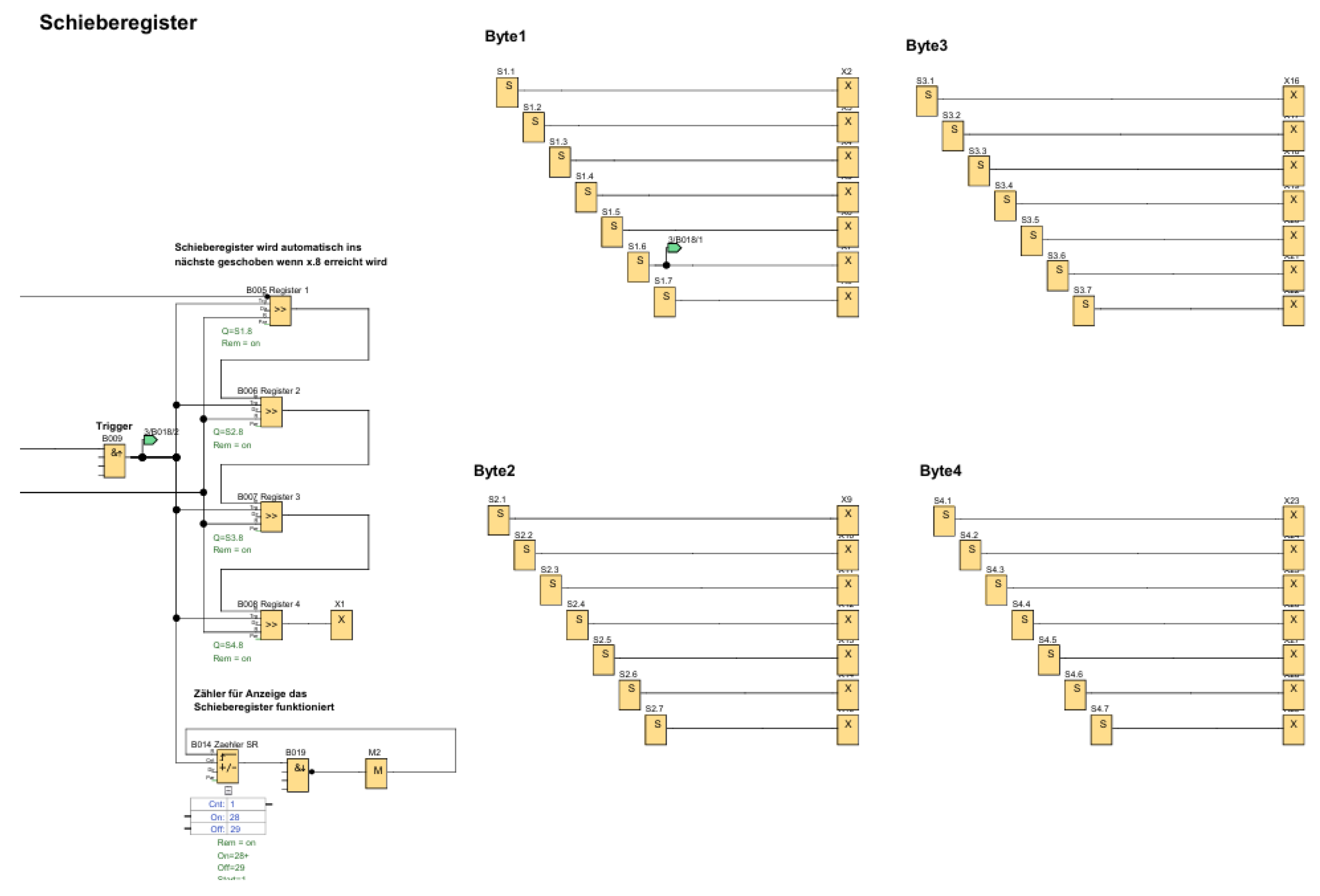

On the PLC side, the logic is designed primarily for timing and synchronization rather than re-evaluating defect criteria. The program implements a shift register (first-in-first-out buffer) that advances with each detected pencil slot. When the trigger sensor confirms a pencil is being scanned, the PLC captures the sensor’s NOK output and loads it into the register. Each pulse from the counter sensor then shifts the register forward, effectively tracking the physical movement of the pencil along the conveyor. The shift register length is configured to match the number of slots between the scanner and the ejector. In our prototype, this was set to six. As the defective pencil reaches the ejector position, the corresponding bit exits the register and activates the ejector output.

The ladder logic includes input conditioning (to detect valid triggers and ignore empty slots), register control (based on counter pulses), and output activation. Additional safety logic enforces a minimum time interval between successive ejections to allow the actuator to reset. The ladder program was structured into two main parts: input signal processing and output control. For reference, all PLC-related diagrams and implementation screenshots, including the shift register configuration, memory logic, and output coil control—are provided in the

Appendix A (

Figure A1,

Figure A2 and

Figure A3).

2.4. Prototype Testing Procedure

To evaluate the system’s performance, a series of experiments were conducted using a laboratory-scale conveyor setup. Sample pencils were fabricated to represent three categories: (1) good pencils with intact leads and no defects; (2) missing or recessed lead pencils, where the graphite tip was deliberately removed or pushed back by more than 2 mm to simulate the target defect; and (3) broken lead pencils, in which the graphite core was fractured at approximately half its length, resulting in a visible but shortened tip that represents a more subtle defect case. A total of 50 defective pencils (40 in the missing/recessed category, 10 with broken leads) were prepared, along with over 160 good pencils, to serve as test samples. The prototype was tested in multiple runs under different conditions:

Mixed-run test: A total of 160 good and 40 defective pencils were randomly intermingled on the conveyor to assess detection accuracy and false positives. The test was repeated twice to increase data reliability.

Defect-only stress test: The 40 defective pencils were run five times each (200 total passes) without good pencils present, to evaluate true positive rate and detection consistency.

Orientation variability test: Ten broken-lead pencils were manually rotated and scanned 10 times each (100 trials) to assess detection sensitivity to lead orientation.

Continuous throughput test: The system was run continuously with 600 pencil passes to simulate production conditions and verify long-term timing and PLC logic reliability.

Throughout testing, the PLC’s log of classification decisions and ejection actions was continuously recorded. Additionally, the laser sensor’s internal software logging was used to verify measurement outputs for selected cases. Each pencil pass was categorized into one of four outcomes: true positive (TP), where a defective pencil was correctly identified and ejected; true negative (TN), where a good pencil was correctly retained; false positive (FP), where a good pencil was incorrectly flagged as defective; and false negative (FN), where a defective pencil was missed and not ejected.

From these classifications, key performance metrics were calculated, including overall detection accuracy, false positive rate, and false negative rate, both globally and per defect type.

Table 1 summarizes the results by pencil category, while the confusion matrix in

Table 2 presents the aggregated outcomes across all test runs. All tests were conducted under controlled lab conditions, with the conveyor speed set to 180 pencils per minute (approximately 0.33 m/s). Standard ambient lighting was used, but the laser sensor’s performance remained unaffected due to its active illumination and filtering. Prior to testing, sensor thresholds (e.g., 2.0 mm depth, 2 mm groove width) were fine-tuned using a small calibration set. No further adjustments were made during the main experiments. The system operated continuously throughout the tests, and no drift or temperature-related instability was observed, confirming stable performance via the sensor’s internal calibration.

3. Results

The system demonstrated excellent performance in detecting pencils with missing or recessed leads, with no false detections on good pencils. The overall accuracy measures the proportion of all correct predictions.

Over the course of 620 pencil evaluations, including repeated runs, the system achieved an overall accuracy of about 98.2% in classifying pencils, as listed in

Table 1. All good pencils (320 out of 320 trials) were correctly recognized as good, yielding a false positive rate of 0%. Hence, the system did not mistakenly reject any intact pencil during testing. For the primary defect category of missing or significantly recessed leads, the system correctly identified 197 out of 200 instances, resulting in a detection rate of 98.5% for that defect type. Only 3 pencils in this category were missed (i.e., false negatives). For the more challenging defect type of partially broken leads, 92 out of 100 trials were correctly flagged, corresponding to a 92% detection rate. These broken-lead cases accounted for the majority of misses in our tests, as discussed below.

The aggregated confusion matrix in

Table 2 further illustrates system performance. Out of 320 passes of good pencils, none triggered a false eject (TN = 320, FP = 0). Out of 300 total defect passes (200 missing-lead + 100 broken-lead), 289 were correctly rejected (TP = 289) and 11 were missed (FN = 11). This yields an overall detection accuracy of

98.2% and zero false positive rate. The false negative rate was low (approximately 3.7% of defective pencils were missed, all in the broken lead subset). These results meet the design objectives of high defect removal efficiency while preserving all good product.

3.1. Detection of Primary Defects

The missing/recessed lead category—the primary defect targeted by this system—was detected with high reliability. After initial threshold tuning, only 3 of 200 instances were missed, all borderline cases with lead recession near the 2 mm threshold. Such cases could likely be eliminated by slightly tightening the threshold or incorporating additional checks, such as detecting graphite presence. Importantly, each of these pencils was identified as defective in subsequent runs or orientations, ensuring no defective unit consistently escaped detection. This robust performance confirms that the laser triangulation method is well-suited for detecting the absence of material where it should exist. Depth and gap measurements provided clear separation between normal pencils (groove depth ∼0–0.5 mm; gap width ≈0 mm) and missing-lead pencils (groove depth 3–5 mm; gap width 4–5 mm), making classification straightforward and consistent. Performance remained stable across all tested pencil shapes and sizes (round, hexagonal, varying diameters), with no false rejections due to geometry differences, demonstrating strong generalization.

The system did not reject any good pencils during mixed tests, correctly allowing all intact products to pass. This zero false positive rate is significant, as it ensures the solution introduces no additional waste by mistakenly discarding acceptable items—a common issue with overly sensitive vision systems. The onboard logic, combining multiple criteria (depth, gap, etc.), effectively prevented false triggers caused by noise or minor surface irregularities. For example, small chips or wood irregularities near the lead occasionally created minor gaps or shadows, yet the requirement for both depth and width anomalies to occur simultaneously avoided misclassification. The counter sensor also ensured precise ejection timing, removing only the targeted pencil without disturbing adjacent ones. This result meets a key objective: eliminating false scrap, in contrast to the previous system, which discarded all pencils from any affected slat, leading to substantial unnecessary waste.

3.2. Rare Defect and Orientation Sensitivity

The slightly lower detection rate for broken-lead cases (90–92%) highlighted an orientation-dependent limitation. Analysis of missed cases showed that detection could fail when the fractured facet of the lead was oriented away from the laser plane. As illustrated in

Figure 7, when the laser line intersects the break at a shallow angle (left pencil in

Figure 7), the resulting profile shows groove depth and width within normal ranges, leading to a false negative. In contrast, when the line crosses the widest part of the break (right pencil in

Figure 7), the profile exceeds the defect thresholds and correctly triggers rejection. Rotating the same broken-lead pencil confirmed this effect, with detection success varying by angle. This limitation is inherent to single-plane 2D laser triangulation, which captures only one cross-sectional slice; if the defect is not optimally intersected, it may remain undetected. All eleven false negatives observed in our tests were due to this orientation sensitivity. It should be noted that such broken lead defects are relatively rare (they occurred in a minority < 5% of defect cases in real production) and even when present, not all orientations will escape detection. In our continuous tests, a pencil missed in one pass was often detected on a subsequent pass after some jostling or rotation on the conveyor. Nonetheless, this is an identified limitation: the current 2D approach has an orientation dependency. We discuss possible solutions in

Section 4, such as adding a second sensor at a different angle or employing a full 3D scanning approach to eliminate this gap in coverage.

3.3. System Robustness, Performance, and Economic Feasibility

The prototype system consistently met the target throughput of 180 pencils/min, completing a continuous run of approximately 600 pencils without synchronization errors. Each detected defect triggered a single, correctly timed ejection, and no misses occurred due to timing. The PLC’s shift register logic operated reliably even at minimum pencil spacing, while the pneumatic ejector cycled smoothly and could theoretically exceed 3 operations per second. All defective pencils were successfully removed from the conveyor; in a few cases, broken-lead pencils were only partially displaced but still dropped off due to gravity. Minor adjustments in ejector force or angle could fully resolve this.

The laser sensor maintained stable measurements under intentional conveyor vibration and varying lighting conditions, with no calibration drift observed. Dynamic ROI tracking effectively compensated for minor lateral pencil misalignments, although in rare instances (1 in 600 runs) an extreme off-center position prevented full groove coverage, resulting in a missed detection. Such occurrences could be eliminated with improved physical guides or a wider scan area.

From an economic perspective, the estimated implementation cost per production line is less than €10,000 (sensor, controllers, actuators, and installation), well below the threshold Faber-Castell considers acceptable for a two-year payback. Based on annual savings from reduced material waste (

Section 3.2), the payback period is projected at less than one year—potentially as a few months. Even with additional costs for installation, training, and maintenance, the payback period comfortably falls within the first operational year.

Overall, the laser triangulation-based inspection system fulfills its intended purpose: accurately detecting defective pencils without false rejects, operating reliably at production speeds, and providing a technically and financially viable solution. The system successfully detected 98.5% of pencils with missing leads and maintained a zero false-reject rate at a throughput of 200 pencils/min, thereby validating its suitability for high-speed production lines. The full detection and classification workflow is supported by the accompanying data in

Table 1 and

Table 2 and

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. While rare misses due to extreme misalignment highlight an area for refinement, the system is robust, scalable, and cost-effective for deployment across multiple production lines.

4. Discussion

The successful prototype results confirm that the proposed laser triangulation inspection system effectively addresses the quality issue in pencil manufacturing and holds potential for similar inspection applications. This section discusses the significance of the findings, compares the approach with alternative methods, examines its limitations, and outlines possible enhancements.

4.1. Waste Reduction and Quality Improvement

The system was able to intercept defective pencils (missing or recessed leads) with high accuracy, thereby preventing them from advancing to later stages (such as the dot printing machine) where they would cause disturbances. More importantly, unlike the existing vision system which discards an entire multi-pencil slat for one missing lead, the new approach removes only the individual defective units. This granular removal translates into a drastic reduction in material waste: instead of losing on average 7–8 good pencils per defective slat, those pencils are now recovered. Based on the earlier analysis of production figures, implementing this system across lines could save on the order of tens of thousands of pencils per year, leading to significant financial savings. This is a noteworthy contribution to sustainable manufacturing, aligning with Industry 5.0 objectives and Sustainable Development Goal 12 (responsible production and waste reduction [

19]). It also supports Faber-Castell’s corporate sustainability goals [

20] of minimizing waste and efficient resource use. In essence, the system turns a previously scrapped portion of production into recoverable yield, improving both economic and environmental performance.

Quality-wise, the system ensures that virtually no pencil with a missing core will pass through to packaging. The detection rate for such defects was 98.5% in our trials, which is already an improvement over the older camera system that sometimes missed subtle cases (the older system’s false negatives were not quantified here, but anecdotal reports suggested a small percentage could slip through or cause jams at dotting). Our system’s slight vulnerability to some broken leads is a minor trade-off; those defects are rarer and less likely to cause customer complaints (a pencil with a half-length lead still writes, albeit not for as long). Nonetheless, in a production context, even those would ideally be removed, which we address in the next subsection.

An added quality benefit is that the system eliminated false positives, i.e., it does not reject good pencils. The previous approach’s “false positives” were entire good pencils sacrificed along with a bad slat. By avoiding any unnecessary rejects, our method preserves maximum throughput and does not inadvertently reduce output. The sorting precision thereby improves overall process yield and customer satisfaction (since more good pencils make it to the final product sets). These improvements reflect the proactive quality control ethos of Quality 5.0 [

4], where advanced sensing and analytics enable addressing defects at the root without collateral damage to good product.

4.2. Comparison with Alternative Inspection Methods

The proposed system was benchmarked against sensor-based inspection methods reported in the literature, as summarized in

Table 3. Earlier studies using laser triangulation or displacement sensors have shown solid detection performance for wood-based or cylindrical items, yet many solutions operated at reduced throughput or exhibited notable false-reject rates. In contrast, our system achieves 98–100% detection for missing leads and 92% for broken leads, with zero false positives and full compatibility with a 200-units-per-minute production speed. This comparison highlights the method as a high-performance, low-complexity alternative to existing industrial inspection approaches.

It is instructive to compare the proposed laser-based solution with other potential approaches. Wang et al. [

24] presented a comprehensive review of surface-defect detection methods for industrial products, classifying existing approaches into traditional image-processing, classical machine-learning, and deep-learning techniques. The study highlighted current challenges such as limited sample availability and small defect sizes, and discussed emerging trends including lightweight deep models, unsupervised learning, and multi-modal sensing for robust industrial inspection.

A conventional vision-based AOI system could, in principle, inspect individual pencils after separation using high-speed imaging. Such a setup would likely require multiple high-resolution cameras to capture different angles of each pencil end, controlled lighting, and real-time image processing at rates exceeding 180 fps. Deep learning methods, such as the line-scan camera system demonstrated by Kim et al. [

25] for precision defect detection, could be adapted for missing-lead identification. However, this would involve substantial hardware, computational resources, and the development of large, diverse training datasets. Vision systems may also face challenges with graphite–wood contrast and could require careful color calibration. In contrast, the laser triangulation method is deterministic, operates with a single sensor, does not require extensive data training, and is more cost-effective and straightforward to integrate at production speeds, making it the more practical choice for this application.

Another concept considered was the use of an array of infrared or time-of-flight (ToF) distance sensors aimed at different points on the pencil tip. A defect would be flagged if any sensor in the array measured an abnormally large distance, indicating a cavity. This approach, explored as Concept B in our design stage, would be simpler than a full profile scanner and potentially cheaper per sensor. While ToF sensors have been used in low-cost defect detection systems, achieving coverage and resolution comparable to the laser profile scanner would be challenging. Reliable detection of a small missing lead would require multiple ToF beams, potentially one for each possible groove position, and calibration could drift over time. Our analysis indicated that such an arrangement would either be unreliable or require a large number of precisely positioned sensors, negating the simplicity advantage. In contrast, the single laser scanner effectively captures hundreds of distance measurements (640 points) across the pencil end, providing far superior resolution in a single device.

For maximum detection capability, a full 3D scanning approach could be employed, using either multiple laser triangulation sensors (e.g., scanning from opposite sides) or alternative 3D imaging technologies such as conoscopic holography or structured light. Giganto et al. [

26] compared laser triangulation and conoscopic holography for inspection of metal parts, highlighting their respective strengths. In this application, two opposing laser scanners could capture the pencil tip from different angles, eliminating the orientation blind spot, where any defect missed by one sensor would be detected by the other. Alternatively, a structured-light projector or a holography-based sensor could capture the full 3D geometry of the pencil tip in a single scan. Such a 3D acquisition, whether achieved through a dedicated 3D sensor or through multi-angle 2D scanning, would eliminate the orientation dependence of the current approach and could enable near-perfect detection of broken leads. However, these methods introduce substantial trade-offs. Capturing full 3D data increases acquisition time, data volume, and system complexity, and it raises hardware costs. Dual-sensor configurations require precise synchronization, while conoscopic holography systems are significantly more expensive and may exceed what is necessary for detecting this relatively simple geometric feature. As a result, any shift to 3D imaging must balance these costs against the incremental gains in detection performance.

The proposed design philosophy was to adopt the simplest solution that meets requirements, leading to the selection of a single laser sensor, which proved largely sufficient with only a minor limitation. If broken leads become a more significant issue in practice, adding a secondary low-cost sensor—such as a small angled laser, which could be a practical upgrade. In summary, compared to a vision-based AOI, the laser triangulation method provided a high-precision, immediate measurement of the feature of interest (lead recess) with minimal processing overhead. It avoided many variables that vision introduces (lighting, color, focus, etc.). The presented approach essentially reduces to a metrological check—measuring a distance/height—which is highly reliable. This is consistent with trends in quality control where optical sensors are increasingly used for in-line metrology and defect sensing, and complements machine vision by focusing on the 3D aspect. The excellent performance of our system reinforces the suitability of laser triangulation for fast, precise inspection tasks, as also evidenced in other industries (e.g., tire inspection, where lasers detected subtle bulges invisible to cameras [

14].

4.3. Limitations and Further Work

The main limitation of the current system is its orientation-dependent gap in detecting certain broken leads that do not present clearly in the scanned cross-section. Although rare, such misses could number in the dozens per day in high-volume production. While less critical than missing leads, they remain a quality concern. Potential enhancements include adding a second laser sensor or using dual-angle scanning to reduce orientation sensitivity, implementing software-based 3D contour reconstruction from successive profiles, or improving mechanical guidance to keep pencils centered under the sensor. A more detailed investigation of orientation effects, such as systematically rotating broken-lead samples through fixed angular increments and mapping detection probabilities, was not conducted in this study but represents a valuable avenue for future work. Such an analysis could yield quantitative insights into the critical angular ranges responsible for misclassification and help optimize sensor placement or develop orientation-agnostic detection schemes.

While upstream detect-and-repair mechanism at the slat stage, where missing leads are identified before cutting and replaced, could in principle achieve near-complete material utilization. This was not implemented in the current system because the existing machine layout does not allow inserting replacement leads into slats with missing cores, and automated rework at production speeds remains technically impractical. Addressing this limitation would require a substantial redesign of the equipment. We therefore present detect-and-repair as a promising direction for the next generation of machines, where future layouts may be capable of supporting such functionality.

A pilot installation on a production line is recommended to validate long-term reliability, confirm false negative rates in real conditions, and assess maintenance needs (e.g., occasional lens cleaning in dusty environments). The system’s flexibility also allows expansion to detect other defects, such as cracked wood, split ends, or protruding leads, by modifying the evaluation logic. This adaptability makes it a potential platform for broader automated optical inspection of pencils.

Future iterations of the system could incorporate tighter sensor fusion by integrating the conveyor encoder and photoelectric sensor signals directly with the laser profile data. Combining these inputs within the detection logic has the potential to improve target tracking and measurement accuracy beyond the current dynamic ROI method used to compensate for minor misalignments.

4.4. Implications for Smart Manufacturing

This project illustrates how targeted, low-cost sensor integration can transform a coarse batch removal process into precise, unit-level defect rejection, aligning with Industry 4.0/5.0 and zero-waste goals. The approach reduces material waste, improves quality, and offers a strong return on investment. Similar methods could be applied to other woodworking or assembly processes where small defects currently cause large-scale scrap.

5. Conclusions

This paper present the design, implementation, and evaluation of a laser triangulation-based inspection system for inline detection and rejection of pencils with missing or defective leads. The system addresses a major waste problem in pencil manufacturing by targeting defects at the individual pencil level, preserving good products that would otherwise be discarded. The proposed system incorporates a laser-triangulation inspection unit designed to reliably detect defects in pencil leads. The main outcomes of this work are summarized as follows:

Detection accuracy and reliability: The system achieved more than 98% accuracy for missing or recessed leads and approximately 92% for broken-lead defects, with zero false positives. Stable operation was maintained at production speeds of 180–200 pencils/min, supported by reliable synchronization between sensing and pneumatic ejection.

Waste reduction and economic viability: By rejecting individual defective pencils rather than entire slats, the system can save tens of thousands of usable pencils per production line annually. These material savings correspond to a projected payback period well under one year, taking installation, training, and maintenance into account.

Inline feasibility using low-cost hardware: The prototype operated at full line speed using only a single laser scanner and a PLC, demonstrating practicality for high-throughput manufacturing and ease of retrofitting into existing production environments.

The findings showed that the proposed system is fast, robust, cost-effective, and suitable for scalable use in industrial environments that require rapid and selective defect removal. Future work will first highlight the pilot implementation and continuous performance assessment within the production environment; second, extend defect detection capabilities using the current sensing system; and third, evaluate dual-sensor or wide-angle configurations to address potential detection gaps. Additional efforts might aim to integrate the system with plant control networks to enhance traceability and process feedback while simultaneously investigating cost-effective strategies for large-scale, multiline deployments.