Morphostratigraphy and Dating of Last Glacial Loess–Palaeosol Sequences in Northwestern Europe: New Results from the Track of the Seine-Nord Europe Canal Project (Northern France)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hermies-Ruyaulcourt: From the First Palaeolithic Discoveries to Recent Research

3. Methods

3.1. Stratigraphy and Sampling

3.2. Sedimentology

3.2.1. Grain-Size Distribution

3.2.2. Magnetic Susceptibility

3.2.3. Total Organic Carbon (TOC)

3.3. OSL Dating

3.3.1. Equivalent Dose Determination

Protocol Used at Archéosciences Bordeaux

Protocol Used at the Re.S.Artes Laboratory

3.3.2. Annual Dose Determination

Field (In Situ) Gamma Spectrometry

Laboratory Gamma Spectrometry and Dose-Rate Calculation

3.3.3. Modelling of Moisture Content

4. Results

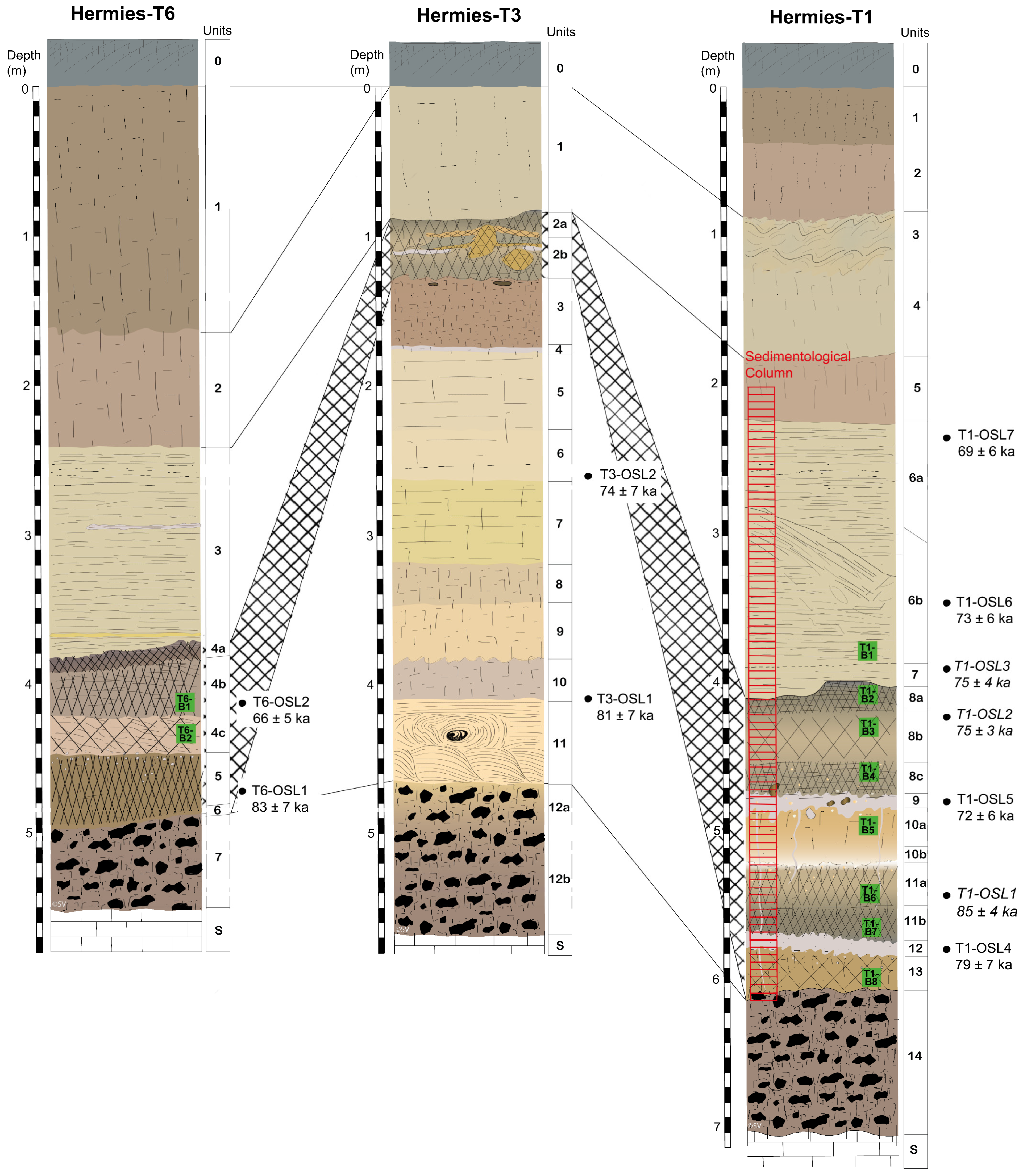

4.1. Stratigraphy and Morphostratigraphy

4.1.1. Description of Units

4.1.2. Morphostratigraphy

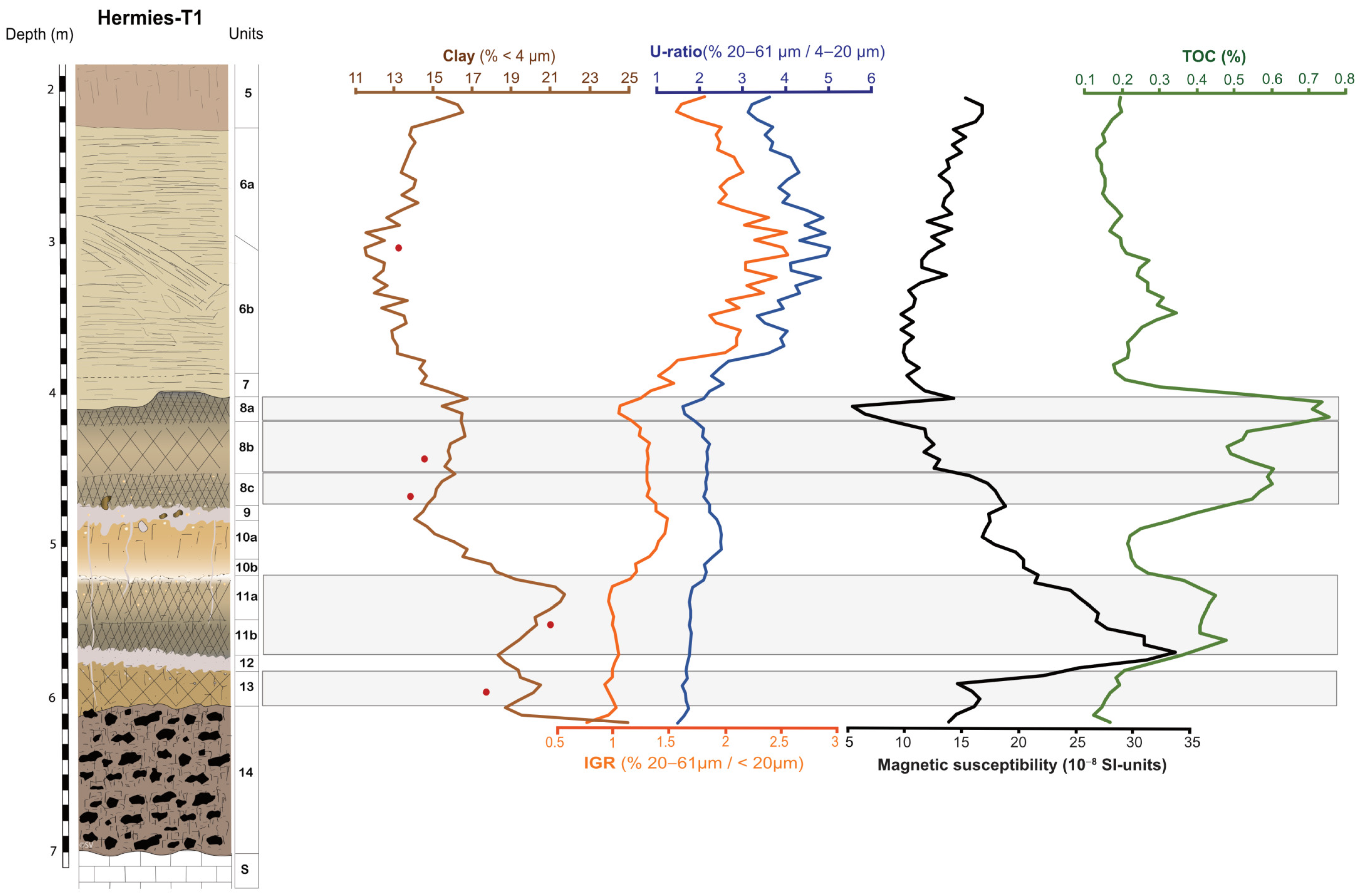

4.2. Sedimentology

4.3. Micromorphology

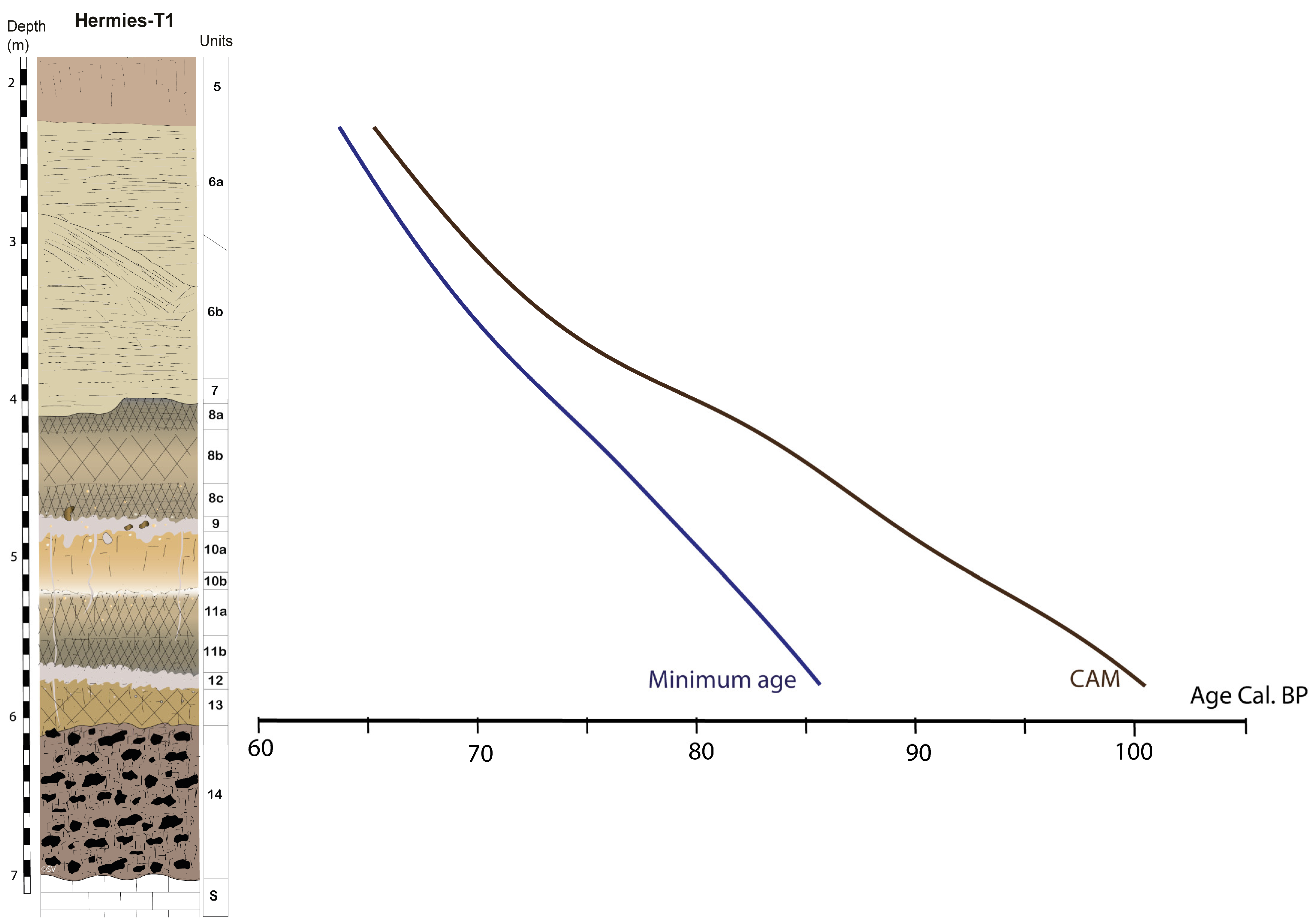

4.4. Dating

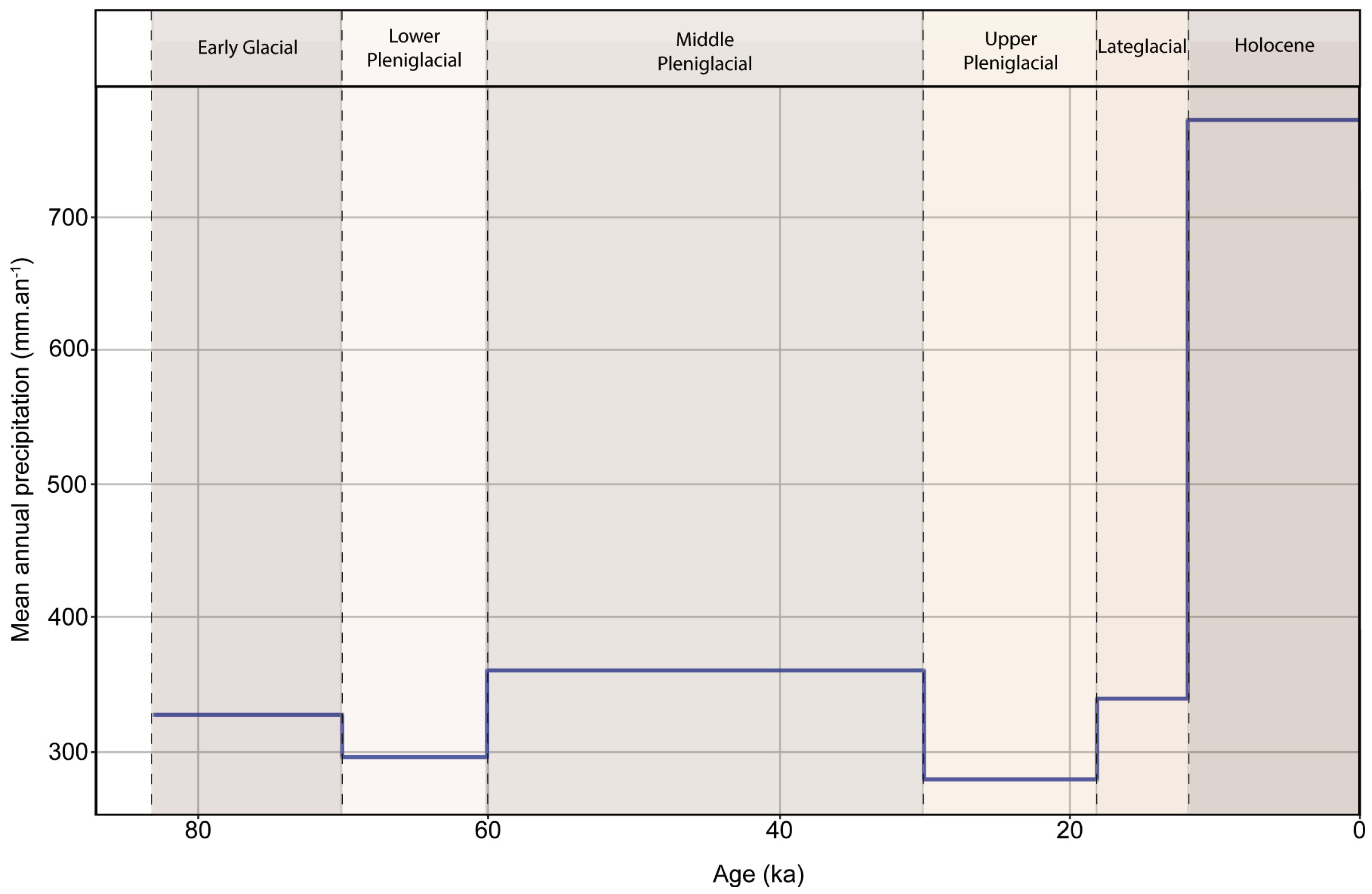

4.4.1. Modelling of Moisture Content

4.4.2. OSL Results

5. Discussion

5.1. The Weichselian Early Glacial Humic Soil Complex

5.1.1. Grey Forest Soils SS-1 and BSO

5.1.2. The Steppe Soil SS-2

5.1.3. Bleached Horizons of the Early Glacial

5.1.4. Humic Soil Complex: Chronological Framework and Erosion

5.1.5. Human Occupations During the Early Glacial

5.2. The “Hermies Laminated Colluvial Deposits”: A Marker Facies of the Lower Pleniglacial

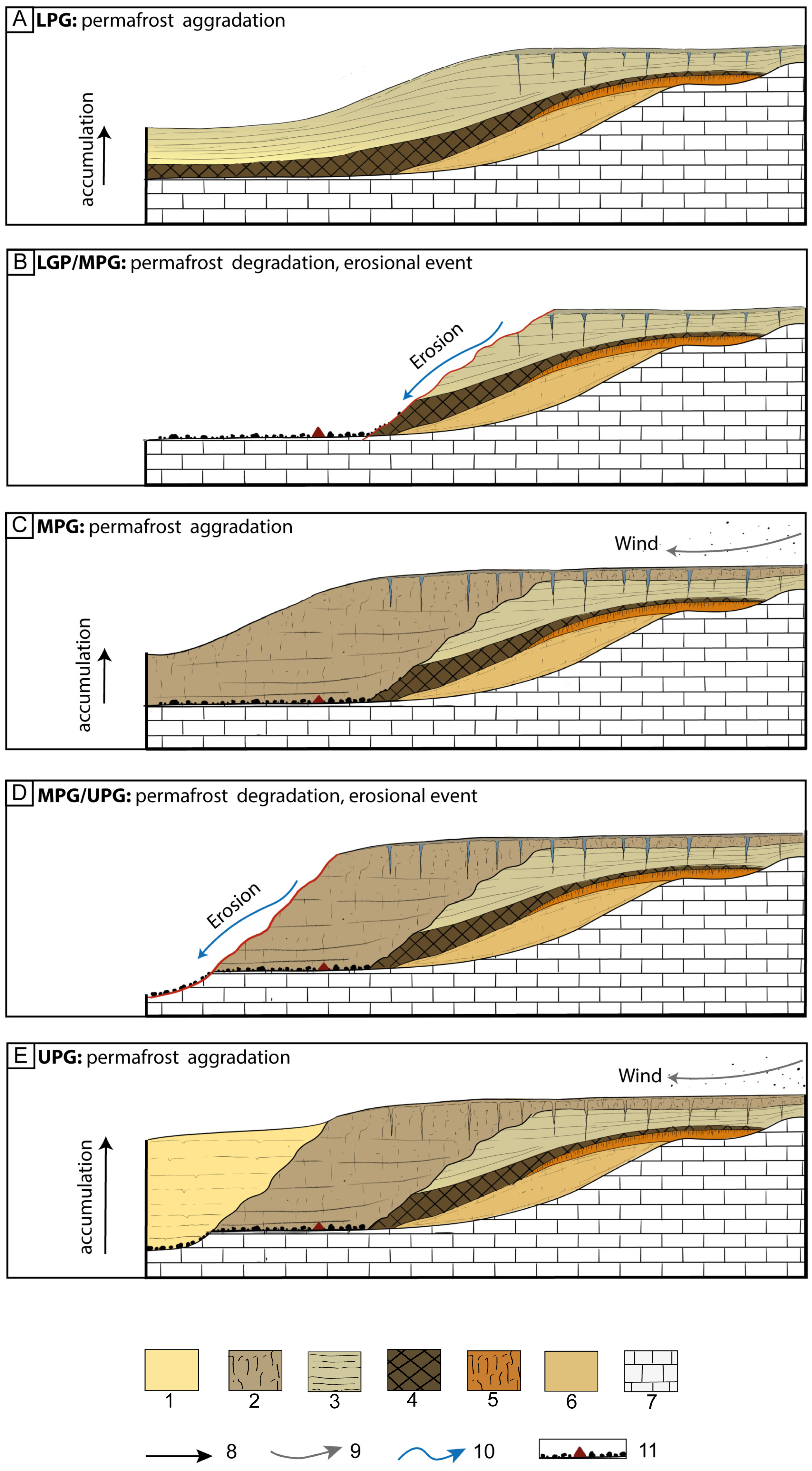

5.3. Middle and Upper Pleniglacial: Erosional Events and Slope Periglacial Dynamics

- Phase 1: A cold phase promoting the development of ice-rich permafrost and large ice-wedge networks in a very cold but sufficiently humid environment to allow major ice accumulation in the ground.

- Phase 2: A phase of rapid warming leading to ice-wedge melting, thickening of the active layer, concentrated slope runoff, and incision by thermokarst channels. These channels widened and deepened to form gullies strongly incising slopes. Such processes caused large-scale remobilisation of slope materials, enhancing colluviation and the reworking of older horizons.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EG | Early Glacial |

| LPG | Lower Pleniglacial |

| MPG | Middle Pleniglacial |

| UPG | Upper Pleniglacial |

References

- Haesaerts, P.; Mestdagh, H. Pedosedimentary evolution of the last interglacial and early glacial sequence in the European loess belt from Belgium to central Russia. Geol. Mijnb. 2000, 79, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Rousseau, D.-D.; Moine, O.; Kunesch, S.; Hatté, C.; Lang, A.; Zöller, L. Evidence of rapid and cyclic eolian deposition during the Last Glacial in European loess series (Loess Events): The high-resolution records from Nussloch (Germany). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 2955–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Coutard, S.; Guerin, G.; Deschodt, L.; Goval, E.; Locht, J.-L.; Paris, C. Upper Pleistocene loess–palaeosol records from Northern France in the European context: Environmental background and dating of the Middle Palaeolithic. Quat. Int. 2016, 411A, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Coutard, S.; Bahain, J.-J.; Locht, J.-L.; Hérisson, D.; Goval, E. The last 750 ka in loess–palaeosol sequences from northern France: Environmental background and dating of the western European Palaeolithic. J. Quat. Sci. 2021, 36, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesaerts, P.; Di Modica, K.; Pirson, S. Le gisement paléolithique de la Sablière Gritten à Rocourt (province de Liège). In Le Paléolithique Moyen en Belgique. Mélanges Marguerite Ulrix-Closset; Toussaint, M., Di Modica, K., Pirson, S., Eds.; ERAUL: Liège, Belgium, 2011; Volume 128, pp. 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Haesaerts, P.; Damblon, F.; Gerasimenko, N.; Spagna, P.; Pirson, S. The Late Pleistocene loess–palaeosol sequence of Middle Belgium. Quatern. Int. 2016, 411, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmkuhl, F.; Zens, J.; Krauß, L.; Schulte, P.; Kels, H. Loess-paleosol sequences at the northern European loess belt in Germany: Distribution, geomorphology and stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 153, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmkuhl, F.; Nett, J.J.; Pötter, S.; Schulte, P.; Sprafke, T.; Jary, Z.; Antoine, P.; Wacha, L.; Wolf, D.; Zerboni, A.; et al. Loess landscapes of Europe—Mapping, geomorphology, and zonal differentiation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 215, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Limondin-Lozouet, N. Late Middle Pleistocene (MIS 10–6) glacial–interglacial records from loess–palaeosol and fluvial sequences from northern France: A cyclostratigraphic approach. Boreas 2024, 53, 476–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatté, C.; Fontugne, M.; Rousseau, D.D.; Antoine, P.; Zöller, L.; Tisnéra-Laborde, N.; Bentaleb, I. Variations of loess organic matter as a record of the vegetation response to climatic changes during the Weichselian. Geology 1998, 26, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Rousseau, D.-D.; Zöller, L.; Lang, A.; Munaut, A.-V.; Hatté, C.; Fontugne, M. High-resolution record of the last Interglacial–glacial cycle in the Nussloch loess–palaeosol sequences, Upper Rhine area, Germany. Quat. Int. 2001, 76–77, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moine, O.; Rousseau, D.-D.; Antoine, P.; Hatté, C. Mise en évidence d’événements climatiques rapides par les faunes de mollusques terrestres des loess weichseliens de Nussloch (Allemagne). Quaternaire 2002, 13, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moine, O. West-European malacofauna from loess deposits of the Weichselian Upper Pleniglacial: Compilation and preliminary analysis of the database. Quaternaire 2008, 19, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moine, O.; Antoine, P.; Hatté, C.; Landais, A.; Mathieu, J.; Prud’homme, C.; Rousseau, D.-D. The impact of Last Glacial climate variability in west-European loess revealed by radiocarbon dating of fossil earthworm granules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6209–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.-D.; Antoine, P.; Hatté, C.; Lang, A.; Zöller, L.; Fontugne, M.; Ben Othman, D.; Luck, J.-M.; Moine, O.; Labonne, M.; et al. Abrupt millennial climatic changes from Nussloch (Germany) Upper Weichselian eolian records during the Last Glaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2002, 21, 1577–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesaerts, P.; Borziac, I.; Chekha, V.P.; Chirica, V.; Drozdov, N.I.; Koulakovska, L.; Orlova, L.A.; van der Plicht, J.; Damblon, F. Charcoal and wood remains for radiocarbon dating Upper Pleistocene loess sequences in Eastern Europe and Central Siberia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010, 29, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, C.; Fischer, P.; Jöris, O.; Gromov, S.; Vinnepand, M.; Hatté, C.; Vonhof, H.; Moine, O.; Vött, A.; Fitzsimmons, K.E. Millennial-timescale quantitative estimates of climate dynamics in central Europe from earthworm calcite granules in loess deposits. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautridou, J.-P.; Sommé, J. Les loess et les provinces climato-sédimentaires du Pléistocène supérieur dans le Nord-Ouest de la France. Essai de corrélation entre le Nord et la Normandie. Quaternaire 1974, 11, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P. Le complexe de sols de Saint-Sauflieu (Somme), micromorphologie et stratigraphie d’une coupe type du début Weichsélien. In Paléolithique et Mésolithique du Nord de la France; Publication du CERP, No. 1; Université des Sciences et des Techniques de Lille-Flandre-Artois: Lille, France, 1989; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Antoine, P.; Bahain, J.-J.; Debenham, N.; Frechen, M.; Gauthier, A.; Hatté, C.; Limondin-Lozouet, N.; Locht, J.-L.; Raymond, P.; Rousseau, D.-D. Nouvelles données sur le Pléistocène du Nord du Bassin Parisien: Les séquences loessiques de Villiers-Adam (Val d’Oise, France). Quaternaire 2003, 14, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Goval, E.; Jamet, G.; Coutard, S.; Moine, O.; Hérisson, D.; Auguste, P.; Guérin, G.; Lagroix, F.; Schmidt, E.; et al. Les séquences loessiques pléistocène supérieur d’Havrincourt (Pas-de-Calais, France): Stratigraphie, paléoenvironnement, géochronologie et occupations paléolithiques. Quaternaire 2014, 25, 321–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, J.-L. Bettencourt-Saint-Ouen (Somme): Cinq Occupations Paléolithiques au Début de la Dernière Glaciation; Nouvelle édition; Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, B.; Vallin, L. Un atelier de débitage levallois intact au sein des loess weichseliens du nord de la France à Hermies (Pas-de-Calais). Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 1993, 90, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, J.-L.; Deschodt, L.; Antoine, P.; Goval, É.; Sellier, N.; Coutard, S.; Debenham, N.; Coudenneau, A.; Caspar, J.-P.; Fabre, J.; et al. Le Gisement Paléolithique Moyen de Fresnoy-au-Val (Somme, France). Rapport Final D’opération Archéologique; INRAP: Paris, France, 2008.

- Locht, J.-L.; Sellier, N.; Antoine, P.; Koehler, H.; Debenham, N. Mauquenchy (Seine-Maritime, France): Mise en évidence de deux niveaux d’occupation paléolithique dans un sol gris forestier daté du SIM 5A (début glaciaire weichselien)/Mauquenchy (Seine-Maritime, France): Evidence of two palaeolithic levels in a MIS 5 grey forest soil (early Weichselian). Quaternaire 2013, 24, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, J.-L.; Coutard, S.; Antoine, P.; Sellier, N.; Ducrocq, T.; Paris, C.; Guerlin, O.; Kiefer, D.; Defaux, F.; Deschodt, L.; et al. Données inédites sur le Quaternaire et le Paléolithique du Nord de la France. Rev. Archéol. Picardie 2014, 3–4, 5–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, J.-L.; Goval, E.; Antoine, P.; Coutard, S.; Auguste, P.; Paris, C.; Hérisson, D. Palaeoenvironments and prehistoric interactions in Northern France from the Eemian Interglacial to the end of the Weichselian Middle Pleniglacial. In “Wild Things”: Recent Advances in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research; Foulds, F.W.F., Drinkall, H.C., Perri, A.R., Clinnick, D.T.G., Walker, J.W.P., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goval, E. Peuplements Néandertaliens Dans le Nord de la France. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lille, Lille, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Limondin-Lozouet, N.; Gauthier, A. Biocénoses Pléistocènes des séquences loessiques de Villiers-Adam (Val d’Oise, France): Études malacologiques et palynologiques. Quaternaire 2003, 14, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Munaut, A.-V.; Sommé, J. Réponse des environnements aux climats du Début Glaciaire weichsélien: Données de la France du Nord-Ouest. Quaternaire 1994, 5, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, J.-L.; Antoine, P.; Bahain, J.-J.; Dwrila, G.; Raymond, P.; Limondin-Lozouet, N.; Gauthier, A.; Debenham, N.; Frechen, M.; Rousseau, D.-D.; et al. Le gisement paléolithique moyen et les séquences pléistocènes de Villiers-Adam (Val-d’Oise): Chronostratigraphie, environnement et implantations humaines. Gall. Préhist. 2003, 45, 1–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Auguste, P.; Beun, N.; Beauchamp, J.; Depaepe, P.; Ducrocq, T.; Engelmann, A.; Fagnart, J.-P.; Frechen, M.; Laurent, M.; et al. Le Quaternaire de la Vallée de la Somme et du littoral Picard. In Excursion de l’Association Française Pour l’Étude du Quaternaire (AFEQ); AFEQ: Amiens, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Frechen, M.; van Vliet-Lanoë, B.; van den Haute, P. The Upper Pleistocene loess record at Harmignies/Belgium—High resolution terrestrial archive of climate forcing. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2001, 173, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieux, E.; Bertran, P.; Saito, K. Spatial analysis of the French Pleistocene permafrost by a GIS database: French Pleistocene permafrost database. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2016, 27, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, J.; French, H.M.; Gorbunov, A.; Marchenko, S.; Velichko, A.A.; Jin, H.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wan, X. The last Permafrost Maximum (LPM) map of the Northern Hemisphere: Permafrost extent and mean annual air temperatures, 25–17 ka BP. Boreas 2014, 43, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechen, M.; Oches, E.A.; Kohfeld, K.E. Loess in Europe: Mass accumulation rates during the Last Glacial Period. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2003, 22, 1835–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosq, M.; Kreutzer, S.; Bertran, P.; Lanos, P.; Dufresne, P.; Schmidt, C. Last Glacial loess in Europe: Luminescence database and chronology of deposition. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 4689–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelot, S.; Antoine, P.; Moine, O.; Hérisson, D. Caractérisation stratigraphique et datation de la limite Pléniglaciaire moyen–Pléniglaciaire supérieur dans les lœss weichseliens du nord de la France: Apports de la séquence d’Haynecourt (Pas-de-Calais). Quaternaire 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sambourg, E.; Antoine, P.; Moine, O.; Saulnier-Copard, S.; Hatté, C.; Fichet, V. La séquence lœssique de Morcourt (Somme, France): Un enregistrement remarquable du Pléniglaciaire moyen et supérieur weichselien (≈55–20 ka) en contexte de versant. Quaternaire 2025, 36, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallin, L.; Masson, B. Le Gisement Moustérien d’Hermies—Le Champ Bruquette. Rapport de Fouilles Programmées, Campagne 1993; Service régional de l’Archéologie du Nord/Pas-de-Calais: Lille, France, 1994; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Goval, É.; Hérisson, D. Les Chasseurs des Steppes Durant le Dernier Glaciaire en France Septentrionale: Paléoenvironnement, Techno-économie, Approche Fonctionnelle et Spatiale du Gisement d’Havrincourt; Université de Liège—Service de Préhistoire: Liège, Belgium, 2018; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Feray, P.; Locht, J.-L.; Lantoine, J.; Coutard, S.; avec la collaboration de Clément, S.; Guerlin, O.; Heccan, L. Hauts-de-France, Hermies et Havrincourt, Canal Seine-Nord Europe—Secteur 4—Site Paléo 3—Tranche 2: Nouvelles Données Paléolithiques au “Tio Marché”. Rapport de Diagnostic Archéologique; INRAP: Paris, France, 2023.

- Locht, J.-L.; Feray, P.; Lantoine, J.; Coutard, S.; Auguste, P.; Clément, S.; Guerlin, O.; Kiefer, D. Hauts-de-France, Hermies/Ruyaulcourt—Paléo 2—CSNE—Sondages Profonds. Rapport de Diagnostic Archéologique; INRAP: Paris, France, 2023.

- Salomon, A. Découverte d’un gisement de silex taillés à Hermies (P.-de-C.). Ann. Soc. Géol. Nord. 1911, 40, 289–291. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, A. Découverte d’une station moustérienne, d’instruments néolithiques et d’une hache à douille près d’Hermies (Pas-de-Calais). Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 1912, 9, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, A. Récoltes de gros outils faisant présumer l’existence d’un atelier acheuléen sur le territoire de Ruyaulcourt (Pas-de-Calais). Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 1912, 9, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, A. Découverte de nouveaux ateliers paléolithiques à Hermies au lieudit «Bertincourt». Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 1912, 9, 673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, A. Découverte d’un troisième gisement moustérien sur le territoire d’Hermies (Pas-de-Calais) au lieudit la vallée de Bertincourt. Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 1913, 10, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallin, L.; Masson, B. Behaviour towards lithic production during the Middle Palaeolithic: Examples from Hermies le Champ Bruquette and Hermies le Tio Marché (Pas-de-Calais, France). In Lithics in Action. Papers from the Conference Lithic Studies in the Year 2000, Lithic Studies Society Occasional Paper No. 8; Wenban-Smith, E.A., Healy, F., Wenban-Smith, E.A., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vallin, L.; Masson, B.; Caspar, J.-P. Taphonomy at Hermies, France: A Mousterian Knapping Site in a Loessic context. J. Field Archaeol. 2001, 28, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallin, L.; Masson, B.; Caspar, J.-P. L’outil idéal. Analyse du standard Levallois des sites moustériens d’Hermies (Nord de la France). Paléo 2006, 18, 237–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, D.; Gustiaux, M.; Coutard, S.; Sellier, N.; Chaidron, C.; Morel, A.; Henton, A.; Coquelle, B.; Trawka, H. Sauchy-Lestrée, Marquion, Bourlon (Pas-de-Calais). Rapport de Diagnostic Archéologique; INRAP: Paris, France, 2009.

- Vandenberghe, J.; Mücher, H.J.; Roebroeks, W.; Gemke, D. Lithostratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the Pleistocene deposits at Maastricht–Belvedere, Southern Limburg (The Netherlands). Meded. Van de Rijks Geol. Dienst Nieuwe Ser. 1985, 39, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Újvári, G.; Kok, J.F.; Varga, V.; Kovács, J. The physics of wind-blown loess: Implications for grain size proxy interpretations in Quaternary paleoclimate studies. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 154, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makó, L.; Molnár, D.; Runa, B.; Bozsó, G.; Cseh, P.; Nagy, B.; Sümegi, P. Selected grain-size and geochemical analyses of the loess–paleosol sequence of Pécel (Northern Hungary): An attempt to determine sediment accumulation conditions and the source area location. Quaternary 2021, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A.; Taylor, R.M. Formation of ultrafine-grained magnetite in soils. Nature 1988, 336, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, J.A.; Dann, R.J.L.; Hay, K.; Lees, J.A.; Loveland, P.J.; Maher, B.A.; O’Grady, K. Frequency-dependent susceptibility measurements of environmental materials. Geophys. J. Int. 1996, 124, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradák, B.; Seto, Y.; Stevens, T.; Újvári, G.; Fehér, K.; Költringer, C. Magnetic susceptibility in the European Loess Belt: New and existing models of magnetic enhancement in loess. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 569, 110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.S.; Wintle, A.G. Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerative-dose protocol. Radiat. Meas. 2000, 32, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanos, P.; Dufresne, P. ChronoModel Version 3: Software for Chronological Modeling of Archaeological Data Using Bayesian Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://chronomodel.com (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Aitken, M.J. An Introduction to Optical Dating: The Dating of Quaternary Sediments by the Use of Photon-Stimulated Luminescence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; p. 267. [Google Scholar]

- Duller, G. Luminescence Dating: Guidelines on Using Luminescence Dating in Archaeology; English Heritage: Swindon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, D.; Richter, A.; Dornich, K. Lexsyg—A new system for luminescence research. Geochronometria 2013, 40, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.; Mercier, N.; Weinstein-Evron, M.; Weissbrod, L.; Shimelmitz, R. Chronology of the late Lower and Middle Palaeolithic at Tabun Cave (Mount Carmel, Israel) with insights into diagenesis and dose rate variation using post-IR IRSL (pIRIR290) dating and infrared spectroscopy. Quat. Geochronol. 2024, 84, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, R.F.; Roberts, R.G.; Laslett, G.M.; Yoshida, H.; Olley, J.M. Optical dating of single and multiple grains of quartz from Jinmium rock shelter, northern Australia: Part I, experimental design and statistical models. Archaeometry 1999, 41, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, N.; Falguères, C. Field gamma dose-rate measurement with a NaI(Tl) detector: Re-evaluation of the “threshold” technique. Anc. TL 2007, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, G.; Mercier, N.; Adamiec, G. Dose-rate conversion factors: Update. Anc. TL 2011, 29, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, G.; Mercier, N.; Nathan, R.; Adamiec, G.; Lefrais, Y. On the use of the infinite matrix assumption and associated concepts: A critical review. Radiat. Meas. 2012, 47, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.J.; Lyons, R.G.; Phillips, S.W. Attenuation of alpha particle track dose for spherical grains. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum. Part. D Nucl. Tracks Radiat. Meas. 1991, 18, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.R.; Hutton, J.T. Cosmic ray and gamma ray dosimetry for TL and ESR. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum. Part. D Nucl. Tracks Radiat. Meas. 1988, 14, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatté, C.; Guiot, J. Palaeoprecipitation reconstruction by inverse modelling using the isotopic signal of loess organic matter: Application to the Nussloch loess sequence (Rhine Valley, Germany). Clim. Dyn. 2005, 25, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautridou, J.-P. L’eau dans les loess de Normandie. Quaternaire 1993, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, D.; Brossard, T.; Cardot, H.; Cavailhes, J.; Hilal, M.; Wavresky, P. Les types de climats en France, une construction spatiale. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. Cartogr. Imag. SIG 2010, 501, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallin, L.; Masson, B. Le Gisement Moustérien d’Hermies—Le Tio Marché. Rapport de Fouille Programmée, Campagne 2001; Service Régional de l’Archéologie du Nord/Pas-de-Calais: Lille, France, 2002; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Fagnart, J.-P.; Coudret, P.; Antoine, P.; Vallin, L.; Sellier, N.; Masson, B. Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien dans le Nord de la France. Mémoires de la Société Préhistorique Française 2013, LVI, 198–214. [Google Scholar]

- Coutard, S.; Antoine, P.; Hérisson, D.; Pirson, S.; Balescu, S.; Forget Brisson, L.; Spagna, P.; Debenham, N.; Barré, M.; Chantreau, Y.; et al. La séquence loessique Pléistocène moyen à supérieur d’Etricourt-Manancourt (Picardie, France): Un enregistrement pédo-sédimentaire de référence pour les derniers 350 ka. Quaternaire 2018, 29, 311–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoops, G. Guidelines for Analysis and Description of Soil and Regolith Thin Sections, 2nd ed.; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Holdridge, L.R. Determination of world plant formations from simple climatic data. Science 1947, 105, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H. Communities and Ecosystems, 2nd ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Guiot, J.; Pons, A.; de Beaulieu, J.-L.; Reille, M. A 140,000-year continental climate reconstruction from two European pollen records. Nature 1989, 338, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.J. Thermoluminescence Dating; Academic Press: London, UK, 1985; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Valladas, H.; Valladas, G. Thermoluminescence dating of burnt flint and quartz: Comparative results. Archaeometry 1987, 29, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timar-Gabor, A.; Buylaert, J.-P.; Guralnik, B.; Trandafir-Antohi, O.; Constantin, D.; Anechitei-Deacu, V.; Jain, M.; Murray, A.S.; Porat, N.; Hao, Q.; et al. On the importance of grain size in luminescence dating using quartz. Quat. Geochronol. 2017, 37, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Kreutzer, S.; Rousseau, D.-D.; Antoine, P.; Hatté, C.; Lagroix, F.; Moine, O.; Gauthier, C.; Svoboda, J.; Lisá, L. The loess sequence of Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic): A new OSL-based chronology of the Last Climatic Cycle. Boreas 2013, 42, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timar, A.; Vandenberghe, D.; Panaiotu, E.C.; Panaiotu, C.G.; Necula, C.; Cosma, C.; Van den Haute, P. Optical dating of Romanian loess using fine-grained quartz. Quat. Geochronol. 2010, 5, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buylaert, J.P.; Vandenberghe, D.; Murray, A.S.; Huot, S.; De Corte, F.; Van den Haute, P. Luminescence dating of old (>70 ka) Chinese loess: A comparison of single aliquot OSL and IRSL techniques. Quat. Geochronol. 2007, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buylaert, J.P.; Murray, A.S.; Vandenberghe, D.; Vriend, M.; De Corte, F.; Van den Haute, P. Optical dating of Chinese loess using sand-sized quartz: Establishing a time frame for Late Pleistocene climate changes in the western part of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat. Geochronol. 2008, 3, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.P. Chronology and the upper dating limit for loess samples from Luochuan section in the Chinese Loess Plateau using quartz OSL SAR protocol. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2010, 37, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibus, E.; Rähle, W.; Wedel, J. Profilaufbau, Molluskenführung und Parallelisierungsmöglichkeiten des Altwürmabschnitts im Lössprofil Mainz-Weisenau. Eiszeitalt. Und Ggw. 2002, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, W. Late Pleistocene loess of the Lower Rhine. Quatern. Int. 2016, 393, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, W. Interglacial complex and solcomplex. Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. 2010, 2, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P. Les lœss en France et dans le Nord-Ouest européen. Rev. Française Géotech. 2002, 99, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Haute, P.; Frechen, M.; Buylaert, J.-P.; Vandenberghe, D.; De Corte, F. The Last Interglacial palaeosol in the Belgian loess belt: TL age record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2003, 22, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.O.; Bigler, M.; Blockley, S.P.; Blunier, T.; Buchardt, S.L.; Clausen, H.B.; Cvijanovic, I.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Johnsen, S.J.; Fischer, H.; et al. A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: Refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2014, 106, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, A.; Frechen, M. Datations TL/IRSL. In Le Quaternaire de la Vallée de la Somme et du Littoral Picard. Livret-Guide de L’excursion de l’AFEQ dans le Bassin de la Somme; Antoine, P., Ed.; AFEQ: Amiens, France, 1998; pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, A.; Frechen, M.; Antoine, P. Chronostratigraphie frühweichselzeitlicher kolluvialer Sedimente von Bettencourt-Saint-Ouen (Nord-Frankreich). In Terrestrische Quartärgeologie; Becker-Haumann, R., Frechen, M., Eds.; Logabook: Köln, Germany, 1999; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Haesaerts, P.; Mestdagh, H.; Bosquet, D. The sequence of Remicourt (Hesbaye, Belgium): New insights on the pedo- and chronostratigraphy of the Rocourt soil. Geol. Belg. 1999, 2, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijs, P.M. Loess stratigraphy in Dutch and Belgian Limburg. Eiszeitalt. Ggw. 2002, 51, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Rousseau, D.-D.; Degeai, J.-P.; Moine, O.; Lagroix, F.; Kreutzer, S.; Fuchs, M.; Hatté, C.; Gauthier, C.; Svoboda, J.; et al. High-resolution record of the environmental response to climatic variations during the Last Interglacial–Glacial cycle in Central Europe: The loess–palaeosol sequence of Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 67, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautridou, J.-P. Le Cycle Périglaciaire Pléistocène en Europe du Nord-Ouest et Plus Particulièrement en Normandie. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Caen, Caen, France, 1985. Volume 2. 908p. [Google Scholar]

- Sommé, J.; Lautridou, J.-P.; Heim, J.; Maucorps, J.; Puisségur, J.; Rousseau, D.-D.; Thévenin, A.; Van Vliet-Lanoë, B. Le cycle climatique du Pléistocène supérieur dans les loess d’Alsace à Achenheim. Bull. Assoc. Française Étude Quat. 1986, 23, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechen, M. Upper Pleistocene loess stratigraphy in Southern Germany. Quat. Sci. Rev. 1999, 18, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Catt, J.; Lautridou, J.P.; Sommé, J. The loess and coversands of Northern France and Southern England. J. Quat. Sci. 2003, 18, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, J.-L.; Hérisson, D.; Goval, E.; Cliquet, D.; Huet, B.; Coutard, S.; Antoine, P.; Feray, P. Timescales, space and culture during the Middle Palaeolithic in northwestern France. Quat. Int. 2016, 411, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woillard, G.M. Grande Pile peat bog: A continuous pollen record for the last 140,000 years. Quat. Res. 1978, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woillard, G.M.; Mook, W.G. Carbon-14 dates at Grande Pile: Correlation of land and sea chronologies. Science 1982, 215, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylik, J. Le thermokarst, phénomène négligé dans les études du Pléistocène. Ann. Géogr. 1964, 73, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesaerts, P.; Van Vliet-Lanoë, B. Évolution d’un pergélisol fossile dans les limons du Dernier Glaciaire à Harmignies. Bull. de L’assoc. Française Pour L’étude du Quat. 1973, 22, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tissoux, H.; Valladas, H.; Voinchet, P.; Reyss, J.-L.; Mercier, N.; Falguères, C.; Bahain, J.-J.; Zöller, L.; Antoine, P. OSL and ESR studies of aeolian quartz from the Upper Pleistocene loess sequence of Nussloch (Germany). Quat. Geochronol. 2010, 5, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibus, E.; Frechen, M.; Kösel, M.; Rähle, W. Das jungpleistozäne Lössprofil von Nussloch (SW-Wand) im Aufschluss der Heidelberger Zement AG. Eiszeitalt. Und Ggw. 2007, 56, 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, W. Rhein loess, ice cores and deep-sea cores during MIS 2–5. Z. Dtsch. Ges. Geowiss. 2000, 151, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschodt, L. Contribution des données du nord de la France à l’étude du rôle du thermokarst dans les phases d’activités pléistocènes des talwegs élémentaires. Géomorphologie Relief Process. Environ. 2022, 28, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, C.; Denuve, É.; Fagnart, J.-P.; Coudret, P.; Antoine, P.; Peschaux, C.; Lacarrière, J.; Coutard, S.; Moine, O.; Guérin, G. Premières observations sur le gisement gravettien à statuettes féminines d’Amiens-Renancourt 1 (Somme). Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 2017, 114, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P. Chronostratigraphie et Environnement du Paléolithique du Bassin de la Somme; Publication du Centre d’Études et de Recherches Préhistoriques, Université des Sciences et Techniques de Lille Flandres-Artois: Lille, France, 1990; Volume 2, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

| Units— Figure 5 | Units—T1 | Units—T2 | Units—T3 | Units—T4 | Units—T5 | Units—T6 | Units—T7 | Units—T8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holocene | 0, 1 | 0, 1 | 0, 1 | 0 | 0 | 0, 1 | 0, 1 | 0, 1 | 0, 1 | |

| Upper Plen. | 2 | 2–8 | ||||||||

| Weichselian | Middle Plen. | 3 | 2–5 | 2, 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2–9 | ||

| Lower Plen. | 4 | 6, 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Early Glacial | 5, 6 | 8–13 | 5, 6 | 2 | 2 | 3, 4 | 4–6 | |||

| Eemian | 7 | 7 | 3 | |||||||

| Saalian | 8 | 8, 9 | 4–11 | 3–8 | 5–7 | |||||

| Chalky deposit | 9 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 9, 10 | 8 | 7 | 10, 11 | ||

| Chalk | 10 | S | S | S | S |

| Step | Treatment |

|---|---|

| 1 | Dose (for n = 0) |

| 2 | Preheat (240 °C for 10 s) |

| 3 (Lx) | Green stimulation (125 °C for 100 s) |

| 4 | Test dose (24 Gy) |

| 5 | Cutheat (200 °C for 0 s) |

| 6 (Tx) | Green stimulation (125 °C for 100 s) |

| 7 | Return to step 1 |

| Step | Treatment |

|---|---|

| 1 | Dose (for n = 0) |

| 2 | Preheat (240 °C, 5 °C for 10 s) |

| 3 (Lx) | Blue stimulation (125 °C for 40 s) |

| 4 | Test dose (7 Gy) |

| 5 | Cutheat (160 °C for 10 s) |

| 6 (Tx) | Blue stimulation (125 °C for 40 s) |

| 7 | Return to step 1 |

| Profile T1 | Profile T3 | Profile T6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit No. | Description | Unit No. | Description | Unit No. | Description |

| 0 | Clayey greyish−brown silt with a granular structure. | 0 | Clayey greyish−brown silt with a granular structure. | 0 | Clayey greyish−brown silt with a granular structure. |

| 1 | Brown clayey silt with numerous recent roots. | 1 | Lightly clayey beige silt, structureless. | 1 | Reddish−brown clayey silt. |

| 2 | Dark beige silts with doublets, including grey−white centimetric layers, and small Fe−Mn concretions. | 2.a | Stratified silt of unit 1 with grey−brown humic material. Bioturbations, with a horizontal silt layer at −16 cm. | 2 | Lighter, more massive, greyish silt with lower clay content. |

| 3 | Grey−beige hydromorphic horizon with flowed structure and scattered orange oxidized streaks. The base rises towards the right−hand side of the profile. | 2.b | Brownish humic horizon with burrows filled with yellowish−beige silt. | 3 | Laminated silts with grey, brown, beige, and white layers within a dark beige loess matrix. Visible lenses. |

| 4 | Beige silt, very dense and compact. Structureless, with a few roots. Presence of a grey centimetric band at ~−1.56 m depth, possibly a relict gley horizon. | 3 | Reddish−orange silt with structure, containing humic fragments at the top. | 4.a | Brown−grey structured silt with horizontal siltans extending over 5 cm. |

| 5 | Beige−brown clayey silt with Fe−Mn concretions, mainly visible at the base. | 4 | Mixed silty horizon. | 4.b | Greyish silt with brown horizontal and rightward−oblique laminae, disappearing towards the base. |

| 6.a | Alternation of brown−beige and grey−white silts. The beds follow the concave shape of unit 6b, though to a lesser extent: they dip by 5–10 cm per metre (local deformation). | 5 | Beige and white silts with doublets, poorly defined. | 4.c | Bleached horizon with pellets and oblique bands. |

| 6.b | Alternation of beige and white silts with ferric illuviation features/stains at the base. At the base, the beds are horizontal, while at the top they dip towards the center with amorphous deposits and elongated blocks. Evidence of unconformities, cross−bedding, faults, and local deformations. | 6 | Silts with doublets, very diffuse silt, with Fe−Mn microconcretions. | 5 | Brownish silty horizon with silt pellets at the top. Brown to dark−brown clayey silt with structure. |

| 7 | Light beige−yellow silt, compact and dense, structureless. Presence of ferric stains and Fe−Mn microconcretions. Two thin black bands at the base. | 7 | Beige silts with well−defined doublets, Fe−Mn microconcretions and ferric oxides. Doublets become finer towards the base. | 6 | Lighter clayey silt (siltan?), orange−coloured. |

| 8.a | Top of the humic horizon: dark−brown silt with closely spaced black beds, silt veins and ferric illuviation features. The top surface dips to the left. | 8 | Light−brown slightly clayey silt, with very diffuse silt at the base. Fe−Mn microconcretions. | 7 | Flint gravel within the matrix of unit 6. |

| 8.b | Brown−greyish silt. | 9 | Yellow−brown silt with abundant diffuse silt. Homogeneous matrix, slightly structured. | S | Chalk bedrock at 4.30 m. |

| 8.c | Base of the humic horizon: brownish−grey silt with millimetric alternations. Apparent grain−size grading. Presence of burrows and pellets filled with material from units 9 and 10. | 10 | Brown to brownish silt, Fe−Mn microconcretions mainly at the base. A few grey bands, possibly corresponding to ghost gley horizons. | ||

| 9 | Silty horizon, mixed with the underlying unit at its base and with the overlying unit at its top. Presence of burrows filled with humic pellets from unit 10. | 11 | Yellow silt with frost−deformed beds; large Fe−Mn concretions at base. | ||

| 10.a | Compact orange−brown fine sandy silt, with small burrow casts at the top and larger burrows. | 12.a | Flint gravel in a loessic matrix, with few Fe−Mn features. | ||

| 10.b | Transition phase: lighter orange−brown silt. Structured white silt coating, with small burrow casts. | 12.b | Dark−brown clayey matrix with Fe−Mn accumulation. | ||

| 11.a | Homogeneous brown humic silt with root traces and a few pebbles. | S | Chalk bedrock, 70 cm below the gravel layer. | ||

| 11.b | Brownish−brown slightly clayey silt with prismatic structures and large Fe−Mn concretions. | ||||

| 12 | Mixed silty horizon with Fe−Mn concretions. | ||||

| 13 | Light−brown sandy silt with polyhedral structure, reddish−brown coatings, and pores filled with white silt. Bioturbation and Fe−Mn concretions. | ||||

| 14 | Heterometric flint gravel in a silty−clayey matrix. Fe−Mn concretions. Flint material: frost−shattered, knapped, worn, and patinated. Towards the chalk bedrock, less evidence of wear and more rounded shapes. | ||||

| S | Chalk bedrock at 7 m. |

| Profile T2 | |

| Unit No. | Description |

| 0 | Topsoil. |

| 1 | Brownish-orange clayey silt. |

| 2 | Beige silt with some oxides and hydromorphic features at the top. |

| 3 | Brown clayey silt, compact and weakly structured, with mm-scale Fe-Mn concretion. |

| 4 | Grey-yellow silt with silty bedding. |

| 5 | Humic silt with well-defined mm- to cm-scale silty bedding at the top. |

| 6 | Brown-grey humic silt with more or less diffuse silty beds and burrows, especially at the base. |

| 7 | Brown-orange clayey silt with polyhedral structure and reddish illuviation features. |

| 8 | Beige-orange clayey silt with polyhedral structure. |

| 9 | Brown/white silts with doublets (silt) showing strong deformation. |

| 10 | Flint gravel (partly frost-fractured); (10.a) brown loessic matrix, ~30 cm, mudflow deposit; (10.b) grey–blue hydromorphic fine-sand matrix with oxidation, ~30 cm. |

| Profile T4 | |

| Unit No. | Description |

| 0 | Topsoil. |

| 1 | Brown-grey silt disturbed by greyish bands. |

| 2 | Brown-orange clayey silt. |

| 3 | Silts with thick doublets (clayey, orange); lamellar silt structure. |

| 4 | Brown silt with diffuse white silt. |

| 5 | Silts with thick doublets, including 1–2 cm silty beds within an orange-beige matrix. |

| 6 | Grey-beige loess with less distinct doublets. |

| 7 | Grey-orange hydromorphic silt; convolute deformations. |

| 8 | Beige clayey loess. |

| 9 | Heterometric frost-fractured and weathered flint gravel in a brownish silty matrix, with Fe-Mn grains more abundant towards the base. |

| 10 | Chalk slope deposit composed of chalk, flint, and silt. |

| Profile T5 | |

| Unit No. | Description |

| 0 | Topsoil. |

| 1 | Orange-brown clayey silt, structured. |

| 2 | Grey and light-brown laminated silts; small vertical white bioturbations. Stratification fades towards the base due to bioturbation. |

| 3 | 3.a Dark-brown humic clayey silt with minor clay coatings. 3.b Humic clayey silt with abundant clay coatings; bioturbation (burrows) at the base. 3.c Grey-brown compact silt with burrows; Fe-Mn features; diffuse clay coatings. 3.d Chocolate-brown silt, polyhedral to subpolyhedral, with pockets, burrows, bioturbation, and networks of cracks and microcracks. A flint gravel horizon marks the contact between units 4 and 3.d. |

| 4 | Reddish brown-orange clayey silt, polyhedral, with numerous veins and fissures, visible illuviation features. |

| 5 | Lighter brown-orange silt, less clayey, less structured and less compact than unit 4. |

| 6 | Massive grey silt with oxides and clay coatings, 7–8 cm thick. |

| 7 | Orange silts with thick doublets, cut by silty veins in the upper part, with ferric illuviation features. |

| 8 | Gravel layer = loess-derived mudflow deposit. |

| S | Chalk with a very steep dip to the left. |

| Profile T7 | |

| Unit No. | Description |

| 0 | Topsoil. |

| 1 | Brown-orange clayey silt, weakly structured: crumbly to polyhedral; bioturbation, small burrow casts, earthworm channels, and some illuviation features. |

| 2 | Brown-beige clayey silt with a slight greyish tint and faint oxidation traces at the top. |

| 3 | Light-grey highly hydromorphic silt with horizontal and slightly oblique orange oxides; abundant Fe-Mn and oxides at the top (possibly organic matter?). |

| 4 | Brown-grey clayey silt with granular to polyhedral structure and orange oxides. |

| 5 | Yellowish clayey silt; orange oxides. |

| 6 | Brown-yellow loess with fine black beds, micro- to mm-scale (Fe, organic matter?), and Fe-Mn features. |

| 7 | Two greyish hydromorphic horizons at the base of unit 6, about 5–7 cm thick. |

| 8 | Slightly orange-yellow loess with Fe-Mn features concentrated in the lower 20 cm. |

| 9 | Yellow silt, slightly more clayey and structured than the overlying unit, with Fe-Mn features. |

| 10 | Gravel in unit 9 matrix; transition to brown variably clayey silt with chalk concretions; chalk slope deposit. |

| Profile T8 | |

| Unit No. | Description |

| 0 | Topsoil. |

| 1 | Brown-grey silt with pellet structure and a Nagelbeek tongue-shaped horizon at the base. |

| 2 | Beige-yellow calcareous silt, finely bedded with mm- to cm-scale grey/light-brown layers; very powdery, with undulations and occasional orange oxide spots. |

| 3 | Bedded calcareous silt with a strong predominance of grey silt and some deformations. |

| 4 | Bedded beige calcareous silt, predominantly pale grey, with abundant orange oxidation. Bedding deformations and freeze–thaw fractures preferentially oriented to the right. Deformation and fractures fade towards the base. Basal boundary diffuse. |

| 5 | Light beige bedded calcareous silt with beds slightly thicker than in unit 4. Orange oxidation and Fe-Mn features. Diffuse upper boundary. |

| 6 | Hydromorphic mottled grey–orange calcareous silt with abundant orange oxides. |

| 7 | Yellow-beige calcareous loess forming a mottled matrix with several gley horizons. Gleys become thinner towards the top and the base. A yellow loess band, not fully continuous, occurs between 3.08 and 3.14 m. |

| 8 | Grey hydromorphic calcareous silt. |

| A | |||||||

| Sample | Depth (m) | Units from Figure 5 | Grain size (μm) | Dose rate (μGy/a) | Total | ||

| alpha | beta | gamma + cosmic | |||||

| T1-OSL1 | 5.41 | 5 | 80−125 | 0 | 1471 ± 94 | 1091 ± 55 | 2562 ± 108 |

| T1-OSL2 | 4.23 | 5 | 80−125 | 0 | 1503 ± 93 | 1145 ± 58 | 2648 ± 109 |

| T1-OSL3 | 3.9 | 4 | 80−125 | 0 | 1583 ± 91 | 1072 ± 54 | 2655 ± 106 |

| T1-OSL4 | 5.89 | 5 | 20−40 | 222 ± 31 | 1805 ± 15 | 1321 ± 12 | 3348 ± 37 |

| T1-OSL5 | 4.9 | 5 | 20−40 | 197 ± 28 | 1689 ± 15 | 1219 ± 12 | 3104 ± 34 |

| T1-OSL6 | 3.46 | 4 | 20−40 | 180 ± 26 | 1582 ± 15 | 1159 ± 12 | 2921 ± 32 |

| T1-OSL7 | 2.35 | 4 | 20−40 | 208 ± 30 | 1707 ± 15 | 1307 ± 12 | 3221 ± 35 |

| T3-OSL1 | 3.2 | 8 | 20−40 | 202 ± 29 | 1944 ± 15 | 1375 ± 63 | 3522 ± 71 |

| T3-OSL2 | 1.73 | 8 | 20−40 | 213 ± 30 | 1890 ± 15 | 1322 ± 59 | 3424 ± 68 |

| T6-OSL1 | 3.51 | 5 | 20−40 | 210 ± 30 | 1632 ± 15 | 1264 ± 12 | 3106 ± 35 |

| T6-OSL2 | 2.92 | 5 | 20−40 | 200 ± 28 | 1639 ± 15 | 1244 ± 12 | 3083 ± 34 |

| B | |||||||

| Sample | U (ppm) | Th (ppm) | K (%) | Water content (%) | |||

| T1-OSL1 | 2.99 ± 0.49 | 9.83 ± 0.42 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 10 | |||

| T1-OSL2 | 2.73 ± 0.4 | 8.89 ± 0.42 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 10 | |||

| T1-OSL3 | 2.62 ± 0.33 | 9.48 ± 0.32 | 1.50 ± 0.04 | 10.5 | |||

| T1-OSL4 | 3.56 ± 0.03 | 12.06 ± 0.09 | 1.55 ± 0.02 | 10 | |||

| T1-OSL5 | 3.28 ± 0.04 | 10.35 ± 0.09 | 1.49 ± 0.02 | 10 | |||

| T1-OSL6 | 3.02 ± 0.03 | 9.58 ± 0.08 | 1.42 ± 0.02 | 10.5 | |||

| T1-OSL7 | 3.25 ± 0.03 | 11.69 ± 0.09 | 1.49 ± 0.02 | 10.5 | |||

| T3-OSL1 | 3.1 ± 0.03 | 11.44 ± 0.09 | 1.85 ± 0.02 | 10 | |||

| T3-OSL2 | 3.31 ± 0.03 | 11.93 ± 0.09 | 1.72 ± 0.02 | 10 | |||

| T6-OSL1 | 3.36 ± 0.03 | 11.43 ± 0.1 | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 10 | |||

| T6-OSL2 | 3.35 ± 0.03 | 10.54 ± 0.08 | 1.4 ± 0.02 | 10 | |||

| C | |||||||

| Sample | nGGc | nLn/Tn | De (Gy) | Annual dose (µGy/a) | OSL age | (ka) | n/N |

| CAM | Minimum age | ||||||

| T1-OSL1 | 231 ± 1 | 2714 ± 109 | 103 ± 5 | 85 ± 4 | 4/18 | ||

| T1-OSL2 | 210 ± 1 | 2811 ± 109 | 86 ± 4 | 75 ± 3 | 3/18 | ||

| T1-OSL3 | 212 ± 2 | 2821 ± 106 | 82 ± 3 | 75 ± 4 | 4/18 | ||

| T1-OSL4 | 8 | 20 | 264 ± 10 | 2247.8 ± 35 | 79 ± 7 | ||

| T1-OSL5 | 8 | 20 | 225 ± 6 | 3104.7 ± 32 | 72 ± 6 | ||

| T1-OSL6 | 9 | 20 | 212 ± 6 | 2921 ± 30 | 73 ± 6 | ||

| T1-OSL7 | 10 | 20 | 222 ± 7 | 3221.5 ± 34 | 69 ± 6 | ||

| T3-OSL1 | 9 | 20 | 284 ± 14 | 3521.4 ± 70 | 81 ± 7 | ||

| T3-OSL2 | 9 | 20 | 252 ± 12 | 3424.5 ± 67 | 74 ± 7 | ||

| T6-OSL1 | 9 | 20 | 258 ± 6 | 3106 ± 34 | 83 ± 7 | ||

| T6-OSL2 | 10 | 20 | 205 ± 4 | 3082.8 ± 33 | 66 ± 5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vercelot, S.; Antoine, P.; Richard, M.; Vartanian, E.; Coutard, S.; Hérisson, D. Morphostratigraphy and Dating of Last Glacial Loess–Palaeosol Sequences in Northwestern Europe: New Results from the Track of the Seine-Nord Europe Canal Project (Northern France). Quaternary 2025, 8, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040075

Vercelot S, Antoine P, Richard M, Vartanian E, Coutard S, Hérisson D. Morphostratigraphy and Dating of Last Glacial Loess–Palaeosol Sequences in Northwestern Europe: New Results from the Track of the Seine-Nord Europe Canal Project (Northern France). Quaternary. 2025; 8(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleVercelot, Salomé, Pierre Antoine, Maïlys Richard, Emmanuel Vartanian, Sylvie Coutard, and David Hérisson. 2025. "Morphostratigraphy and Dating of Last Glacial Loess–Palaeosol Sequences in Northwestern Europe: New Results from the Track of the Seine-Nord Europe Canal Project (Northern France)" Quaternary 8, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040075

APA StyleVercelot, S., Antoine, P., Richard, M., Vartanian, E., Coutard, S., & Hérisson, D. (2025). Morphostratigraphy and Dating of Last Glacial Loess–Palaeosol Sequences in Northwestern Europe: New Results from the Track of the Seine-Nord Europe Canal Project (Northern France). Quaternary, 8(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040075