Late Quaternary Evolution and Internal Structure of an Insular Semi-Enclosed Embayment, Kalloni Gulf, Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

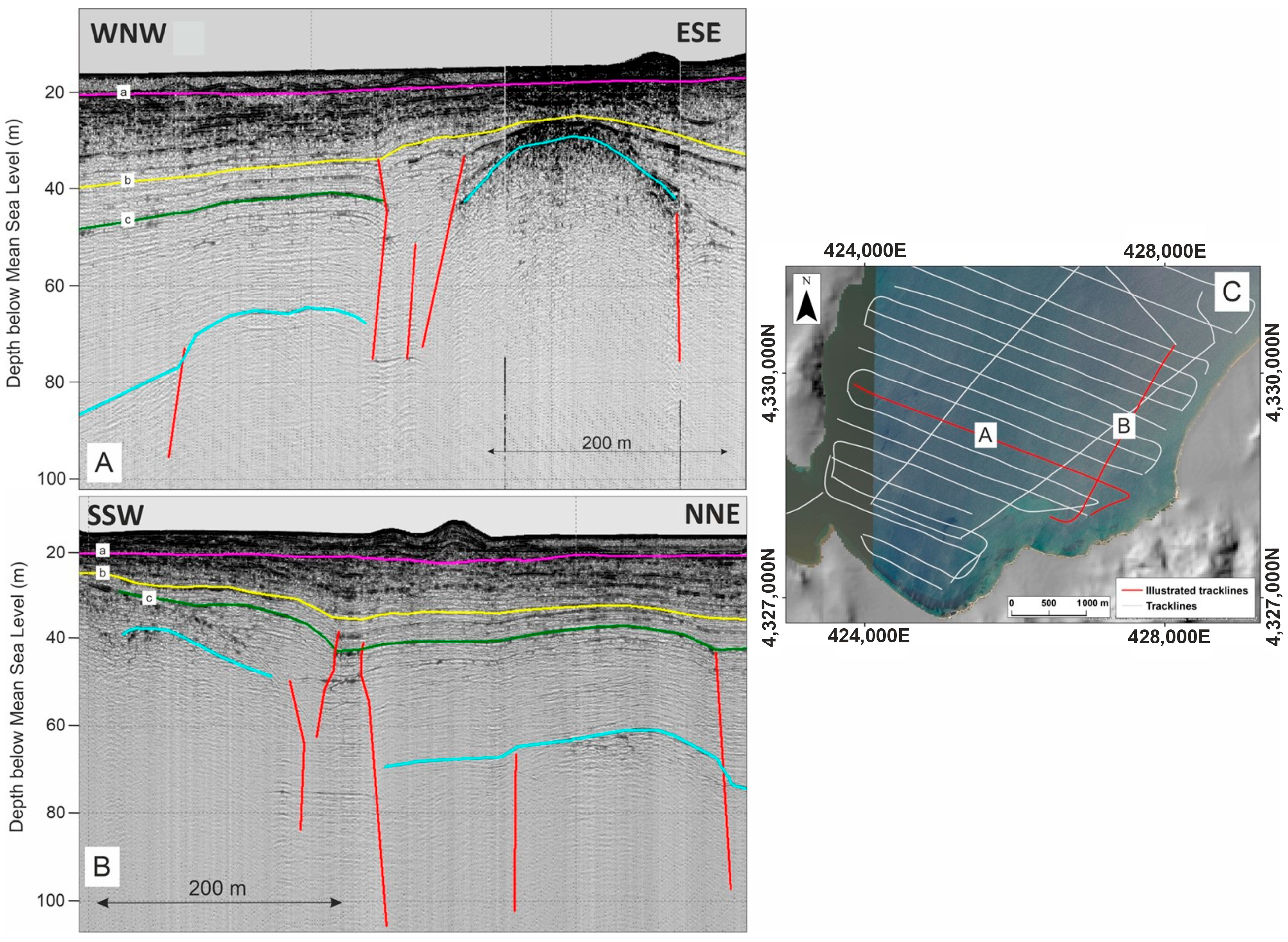

4.1. Seismic Units and Bounding Key Reflectors

4.2. Pre-Holocene Gulf Morphology

4.3. SU Sediment Thickness

4.4. Structural Features

5. Discussion

5.1. Stratigraphic Framework and Sea Level Changes

5.2. Tectonic Features

6. Conclusions

- SU1 which corresponds to the last marine transgression and sea-level highstand period from ~9700 BP to present (linked to MIS 1).

- SU2 is related to a period of sea-level lowstand, during which the gulf was isolated from the open sea and terrestrial sedimentation prevailed. This likely occurred from ~77 ka BP to ~9700 BP, prior to the gulf’s inundation (after 9.7 ka BP) and it is linked to the MIS 2–4 period. On the top of SU2, the paleo-hydrographic network was well developed.

- SU3 is associated with a sea-level highstand that inundated the gulf probably between ~77 and ~130 ka BP (linked to MIS 5).

- SU4 corresponds to a period of sea-level fall, which isolated the gulf from the open sea, prior to ~130 ka BP (linked to MIS 6). On top of this seismic unit, the paleo-hydrographic network could not be directly detected in the seismic profiles, yet the R-c topography and the isopach map of the overlying SU3 provide indications for the existence of paleo-hydrographic network.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fairbanks, R.G.; Matthews, R.K. The Marine Oxygen Isotope Record in Pleistocene Coral, Barbados, West Indies. Quat. Res. 1978, 10, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, J.; Shackleton, N.J. Oxygen isotopes and sea level. Nature 1986, 324, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, B.U.; Hardenbol, J.A.N.; Vail, P.R. Chronology of fluctuating sea levels since the Triassic. Science 1987, 235, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzoli, P.A. Global sea-level changes and their measurement. Glob. Planet. Change 1993, 8, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Chappell, J. Sea level change through the last glacial cycle. Science 2001, 292, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaltırak, C.; İşler, E.B.; Aksu, A.E.; Hiscott, R.N. Evolution of the Bababurnu Basin and shelf of the Biga Peninsula: Western extension of the middle strand of the North Anatolian Fault Zone, Northeast Aegean Sea, Turkey. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 57, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, A.R.; Rood, D.H.; Rockwell, T.K. Correcting MIS5e and 5a sea-level estimates for tectonic uplift, an example from southern California. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 248, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.X.; Berne, S.; Saito, Y.; Lericolais, G.; Marsset, T. Quaternary seismic stratigraphy and paleoenvironments on the continental shelf of the East China Sea. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2000, 18, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelstuen, B.O.; Sejrup, H.P.; Haflidason, H.; Nygård, A.; Berstad, I.M.; Knorr, G. Late Quaternary seismic stratigraphy and geological development of the south Vøring margin, Norwegian Sea. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23, 1847–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, G.; Piper, D.J.; Tziavos, C. Sedimentological response to neotectonics and sea-level change in a delta-fed, complex graben: Gulf of Amvrakikos, western Greece. Mar. Geol. 2007, 236, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işler, E.B.; Aksu, A.E.; Yaltırak, C.; Hiscott, R.N. Seismic stratigraphy and Quaternary sedimentary history of the northeast Aegean Sea. Mar. Geol. 2008, 254, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, G.; Piper, D.J. The changing architecture of sea-level lowstand deposits across the Mid-Pleistocene transition: South Evoikos Gulf, Greece. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 73, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foutrakis, P.M.; Anastasakis, G. Quaternary continental shelf basins of Saronikos Gulf, Aegean Sea. Geo-Mar. Lett. 2020, 40, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kieu, N.; Vu, P.N.H.; Trang, P.H.; Man, H.Q. Late Quaternary high-resolution shallow seismic interpretation: Recognition of depositional sequences and systems tracts in response to sea-level changes in the northernmost part of the central Vietnam continental shelf. Mar. Geol. 2025, 480, 107465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, P. Depositional and erosional coastal processes during the last postglacial sea-level rise; an example from the central Tyrrhenian continental shelf (Italy). J. Sediment. Res. 1996, 66, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchi, M.; Rovere, A.; Chatzipetros, A.; Zouros, N.; Firpo, M. An updated database of Holocene relative sea level changes in NE Aegean Sea. Quat. Int. 2014, 328, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchi, M.; Rovere, A.; Zouros, N.; Desruelles, S.; Caron, V.; Firpo, M. Spatial distribution of sea-level markers on Lesvos Island (NE Aegean Sea): Evidence of differential relative sea-level changes and the neotectonic implications. Geomorphology 2012, 159, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykousis, V. Sea-level changes and shelf break prograding sequences during the last 400 ka in the Aegean margins: Subsidence rates and palaeogeographic implications. Cont. Shelf Res. 2009, 29, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoutsoglou, E.; Hasiotis, T.; Velegrakis, A.F. Holocene records of oyster reefs in a shallow semi-enclosed island embayment of the Aegean Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 302, 108781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikou, P.; Evangelidis, D.; Papanikolaou, D.; Lampridou, D.; Litsas, D.; Tsaparas, Y.; Koliopanos, I.; Petroulia, M. Morphotectonic Structures along the Southwestern Margin of Lesvos Island, and Their Interrelation with the Southern Strand of the North Anatolian Fault, Aegean Sea, Greece. GeoHazards 2021, 2, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipetros, A.; Kiratzi, A.; Sboras, S.; Zouros, N.; Pavlides, S. Active faulting in the north-eastern Aegean Sea Islands. Tectonophysics 2013, 597–598, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livaditis, G.; Alexouli-Livaditi, A. Morphology of Lesvos’ island and coasts. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2004, 36, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe-Piper, G.; Piper, D.J.; Zouros, N.; Anastasakis, G. Age, stratigraphy, sedimentology and tectonic setting of the Sigri Pyroclastic Formation and its fossil forests, Early Miocene, Lesbos, Greece. Basin Res. 2019, 31, 1178–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koglin, N.; Kostopoulos, D.; Reischmann, T. The Lesvos mafic–ultramafic complex, Greece: Ophiolite or incipient rift? Lithos 2009, 108, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrakis, N.J.; Stamatis, G.N. Contribution to the study of thermal waters in Greece: Chemical patterns and origin of thermal water in the thermal springs of Lesvos. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 2008, 22, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreemer, C.; Blewitt, G.; Klein, E.C. A geodetic plate motion and Global Strain Rate Model. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2014, 15, 3849–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, D.; Tsampouraki-Kraounaki, K. Plio-Quaternary extension and strike-slip tectonics in the Aegean. In Transform Plate Boundaries and Fracture Zones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 339–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, P.; Kassaras, I.; Kaviris, G.; Tselentis, G.A.; Voulgaris, N.; Lekkas, E.; Chouliaras, G.; Evangelidis, C.; Pavlou, K.; Kapetanidis, V.; et al. The 12th June 2017 Mw = 6.3 Lesvos earthquake from detailed seismological observations. J. Geodyn. 2018, 115, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilinger, R.; McClusky, S.; Paradissis, D.; Ergintav, S.; Vernant, P. Geodetic constraints on the tectonic evolution of the Aegean region and strain accumulation along the Hellenic subduction zone. Tectonophysics 2010, 488, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.D.; Geiger, A.; Kahle, H.-G.; Veis, G.; Billiris, H.; Paradissis, D.; Felekis, S. Velocity and deformation fields in the North Aegean domain, Greece, and implications for fault kinematics, derived from GPS data 1993–2009. Tectonophysics 2013, 597–598, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazachos, B.C.; Papazachou, C. The Earthquakes of Greece; Ziti Publ. Co.: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2003; p. 286. Available online: www.emidius.eu (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Nomikou, P.; Papanikolaou, D.; Lampridou, D.; Blum, M.; Hübscher, C. The active tectonic structures along the southern margin of Lesvos Island, related to the seismic activity of July 2017, Aegean Sea, Greece. Geo-Mar. Lett. 2021, 41, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlides, S.; Tsapanos, T.; Zouros, N.; Sboras, S.; Koravos, G.; Chatzipetros, A. Using active fault data for assessing seismic hazard: A case study from NE Aegean sea, Greece. In Proceedings of the Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering Satellite Conference XVIIth International Conference on Soil Mechanics & Geotechnical Engineering, Alexandria, Egypt, 2–3 October 2009; Volume 10, p. 2009. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257220587_Using_active_fault_data_for_assessing_seismic_hazard_a_case_study_from_NE_Aegean_sea_Greece (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Papanikolaou, D.; Nomikou, P.; Papanikolaou, I.; Lampridou, D.; Rousakis, G.; Alexandri, M. Active tectonics and seismic hazard in Skyros Basin, North Aegean Sea, Greece. Mar. Geol. 2019, 407, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourouzidou, O.; Pavlides, S.; Fytikas, M.; Zouros, N. The neotectonic characteristic structures at the area of Gavathas, Northern Lesvos Island (Aegean, Greece). In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Eastern Mediterranean Geology, Thessaloniki, Greece, 14–20 April 2004; pp. S1–S20. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258199559_The_neotectonic_characteristic_structures_at_the_area_of_Gavathas_Northern_Lesvos_island_Aegean_Greece (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Soulakellis, N.A.; Novak, I.D.; Zouros, N.; Lowman, P.; Yates, J. Fusing Landsat-5/TM Imagery and Shaded Relief Maps in Tectonic and Geomorphic Mapping. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fytikas, M.; Lombardi, S.; Papachristou, M.; Pavlides, S.; Zouros, N.; Soulakellis, N. Investigation of the 1867 Lesbos (NE Aegean) earthquake fault pattern based on soil-gas geochemical data. Tectonophysics 1999, 308, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavlas, N.; Kiratzi, A.; Margaris, B.; Karakaisis, G. Probabilistic seismic hazard assessment (PSHA) for Lesvos island using the logic tree approach. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2019, 55, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchum, R.M.; Vail, P.R.; Thompson, S., III. Seismic stratigraphy and global changes of sea level, part 2: The depositional sequence as a basic unit for stratigraphic analysis. In Seismic Stratigraphy—Applications to Hydrocarbon Exploration; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wagoner, J.C.; Posamentier, H.W.; Mitchum, R.M.; Vail, P.R.; Sarg, J.F.; Loutit, T.S.; Hardenbol, J. An overview of the fundamentals of sequence stratigraphy and key definitions. In Sea-Level Changes: An Integrated Approach; Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchum, R.M., Jr.; Van Wagoner, J.C. High-frequency sequences and their stacking patterns: Sequence-stratigraphic evidence of high-frequency eustatic cycles. Sediment. Geol. 1991, 70, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catuneanu, O.; Abreu, V.; Bhattacharya, J.P.; Blum, M.D.; Dalrymple, R.W.; Eriksson, P.G.; Fielding, C.R.; Fisher, W.L.; Galloway, W.E.; Gibling, M.R.; et al. Towards the standardization of sequence stratigraphy. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2009, 92, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoutsoglou, E.; Lioupa, V.; Hasiotis, T. Geomorphological patterns of modern and buried reefs in two insular land-locked embayments (Lesvos Island, Greece): A comparative study. J. Coast. Res. 2024, 113, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoutsoglou, E.; Hasiotis, T. Evidence of Holocene Sea-Level Rise from Buried Oyster Reef Terrain in a Land-Locked Insular Embayment in Greece. Geosciences 2025, 15, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, B.; Lamy, N. Spatial patterns and seasonal strategy of macrobenthic species relating to hydrodynamics in a coastal bay: Jour de Rech. Oceanographique 2002, 27, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lambeck, K.; Sivan, D.; Purcell, A. Timing of the last Mediterranean Sea Black Sea connection from isostatic models and regional sea-level data. In The Black Sea Flood Question: Changes in Coastline, Climate, and Human Settlement; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waelbroeck, C.; Labeyrie, L.; Michel, E.; Duplessy, J.C.; Mcmanus, J.F.; Lambeck, K.; Balbon, E.; Labracherie, M. Sea-level and deep-water temperature changes derived from benthic foraminifera isotopic records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2002, 21, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintanja, R.; Van De Wal, R.S.; Oerlemans, J. Modelled atmospheric temperatures and global sea levels over the past million years. Nature 2005, 437, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, F.; Ridente, D. Stratigraphic architecture and spatio-temporal variability of high-frequency (Milankovitch) depositional cycles on modern continental margins: An overview. Mar. Geol. 2014, 352, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddall, M.; Rohling, E.J.; Thompson, W.G.; Waelbroeck, C. Marine isotope stage 3 sea level fluctuations: Data synthesis and new outlook. Rev. Geophys. 2008, 46, RG4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanidou, N.; Athanassas, C.; Cole, J.; Iliopoulos, G.; Katerinopoulos, A.; Magganas, A.; McNabb, J. The acheulian site at rodafnidia, Lisvori, on Lesbos, Greece: 2010–2012. In Paleoanthropology of the Balkans and Anatolia: Human Evolution and Its Context; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinopoli, G.; Peyron, O.; Masi, A.; Holtvoeth, J.; Francke, A.; Wagner, B.; Sadori, L. Pollen-based temperature and precipitation changes in the Ohrid Basin (western Balkans) between 160 and 70 ka. Clim. Past 2019, 15, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalan, P.V. Identification of strike-slip faults in seismic sections. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SU | Illustration | Seismic Characteristics and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

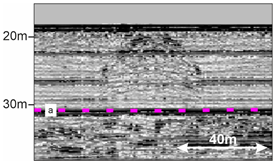

| 1 |  | Acoustically semi-transparent surficial layer underlain by low amplitude continuous reflections that are interrupted by two higher amplitude reflections and hummocky-chaotic mounds of various relief on the seafloor and at different stratigraphic levels. Holocene marine deposits hosting abundant oyster reefs (purple line (a): R-a). |

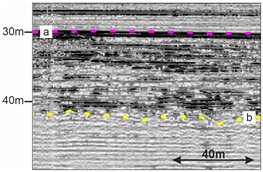

| 2 |  | Continuous, high-amplitude and rugged upper reflector, locally V or U-shaped, with underlying high amplitude, continuous or discontinuous reflections and locally chaotic lenses or layers. Occasionally internal hyperbolas. Dominantly coarse-grained and/or compacted low-stand deposits incised by channels (purple line (a): R-a, yellow line (b): R-b). |

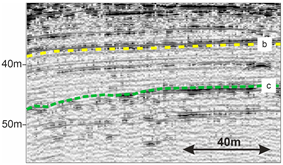

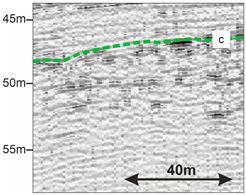

| 3 |  | Medium-amplitude, continuous upper reflector, with underlying lower-amplitude, parallel and laterally continuous seismic reflections. Two distinct, internal medium-amplitude reflectors are observed. Fine-grained high-stand deposits (yellow line (b): R-b, green line (c): R-c). |

| 4 |  | Continuous, high-amplitude and rugged upper reflector, with underlying medium to high-amplitude, parallel to sub-parallel and locally chaotic reflections. Coarse-grained and/or compacted low-stand deposits (green line (c): R-c). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karsiotis, P.; Hasiotis, T.; Petsimeris, I.T.; Manoutsoglou, E.; Andreadis, O. Late Quaternary Evolution and Internal Structure of an Insular Semi-Enclosed Embayment, Kalloni Gulf, Greece. Quaternary 2025, 8, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040074

Karsiotis P, Hasiotis T, Petsimeris IT, Manoutsoglou E, Andreadis O. Late Quaternary Evolution and Internal Structure of an Insular Semi-Enclosed Embayment, Kalloni Gulf, Greece. Quaternary. 2025; 8(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarsiotis, Panagiotis, Thomas Hasiotis, Ivan Theophilos Petsimeris, Evangelia Manoutsoglou, and Olympos Andreadis. 2025. "Late Quaternary Evolution and Internal Structure of an Insular Semi-Enclosed Embayment, Kalloni Gulf, Greece" Quaternary 8, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040074

APA StyleKarsiotis, P., Hasiotis, T., Petsimeris, I. T., Manoutsoglou, E., & Andreadis, O. (2025). Late Quaternary Evolution and Internal Structure of an Insular Semi-Enclosed Embayment, Kalloni Gulf, Greece. Quaternary, 8(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040074