What Was the “Devil’s” Body Size? Reflections on the Body Mass and Stature of the Foresta Hominin Trackmakers (Roccamonfina Volcano, Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

Why Is the Foresta/Devil’s Trails Ichnosite So Unique?

2. Materials and Methods

Material

3. Results

3.1. Body Mass and Stature Estimates

3.1.1. Variation Ranges of the Body Mass and Stature Estimates

3.1.2. Quantitative Analysis: Box Plots, Normality Tests, One-Way ANOVA, and Principal Component Analysis

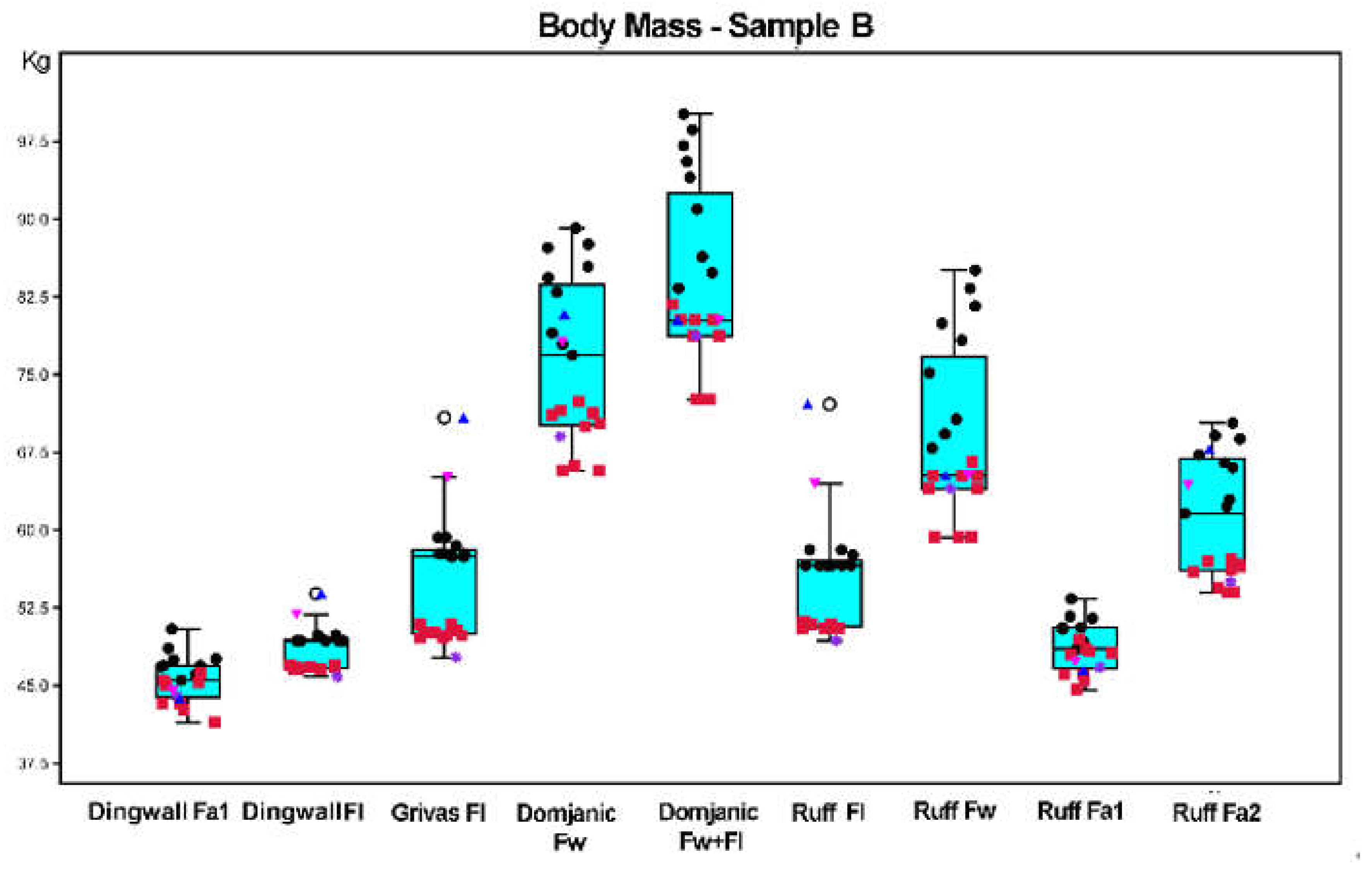

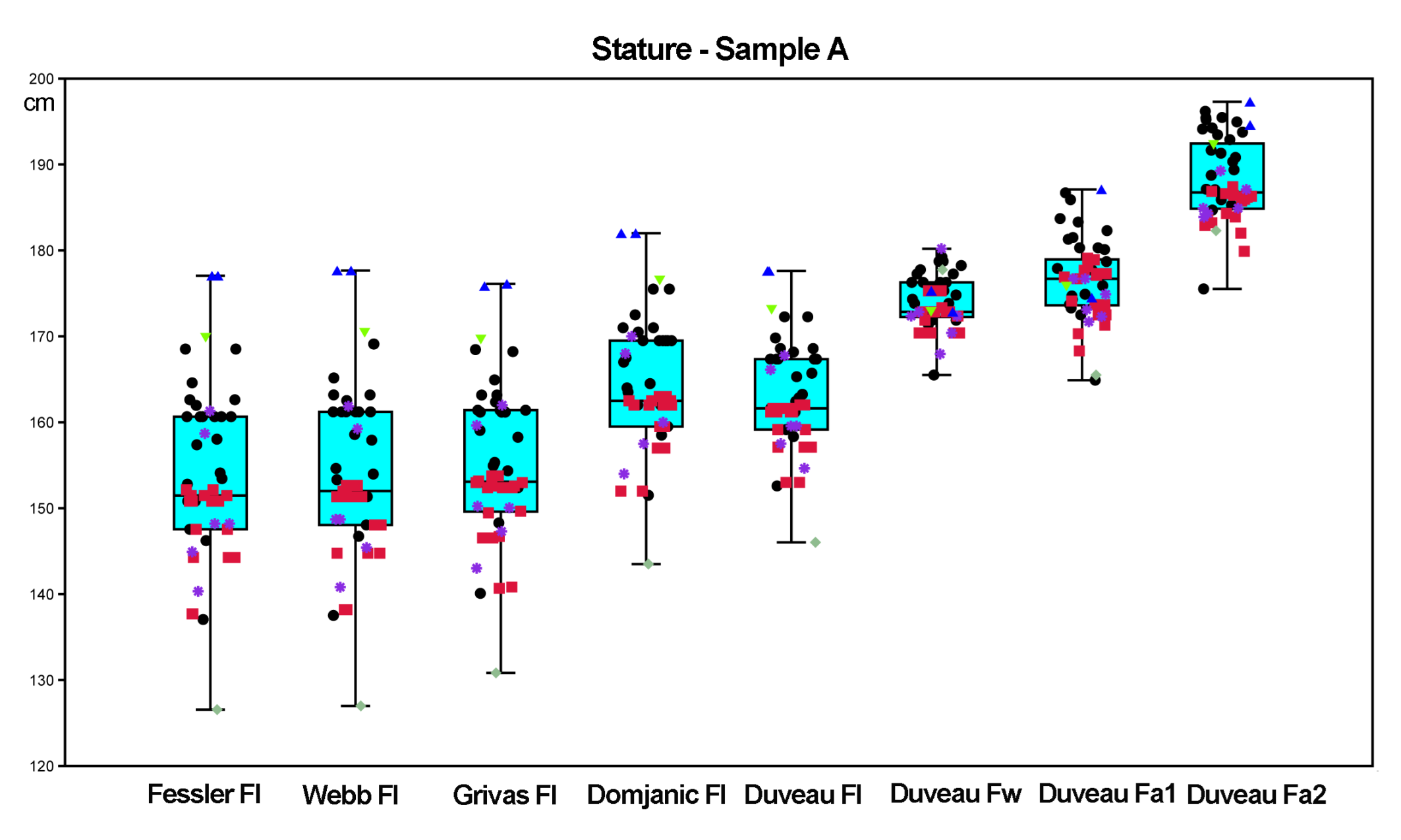

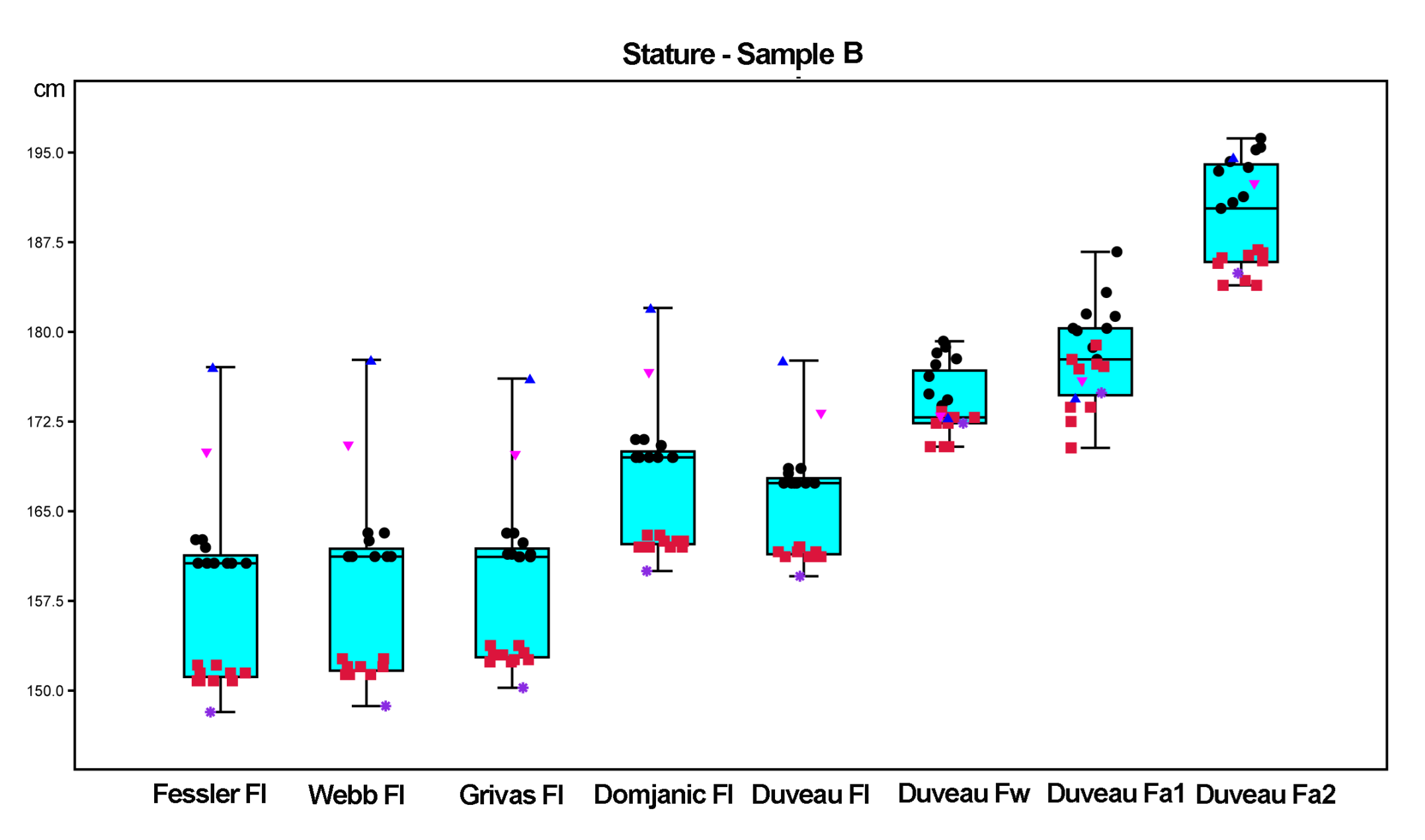

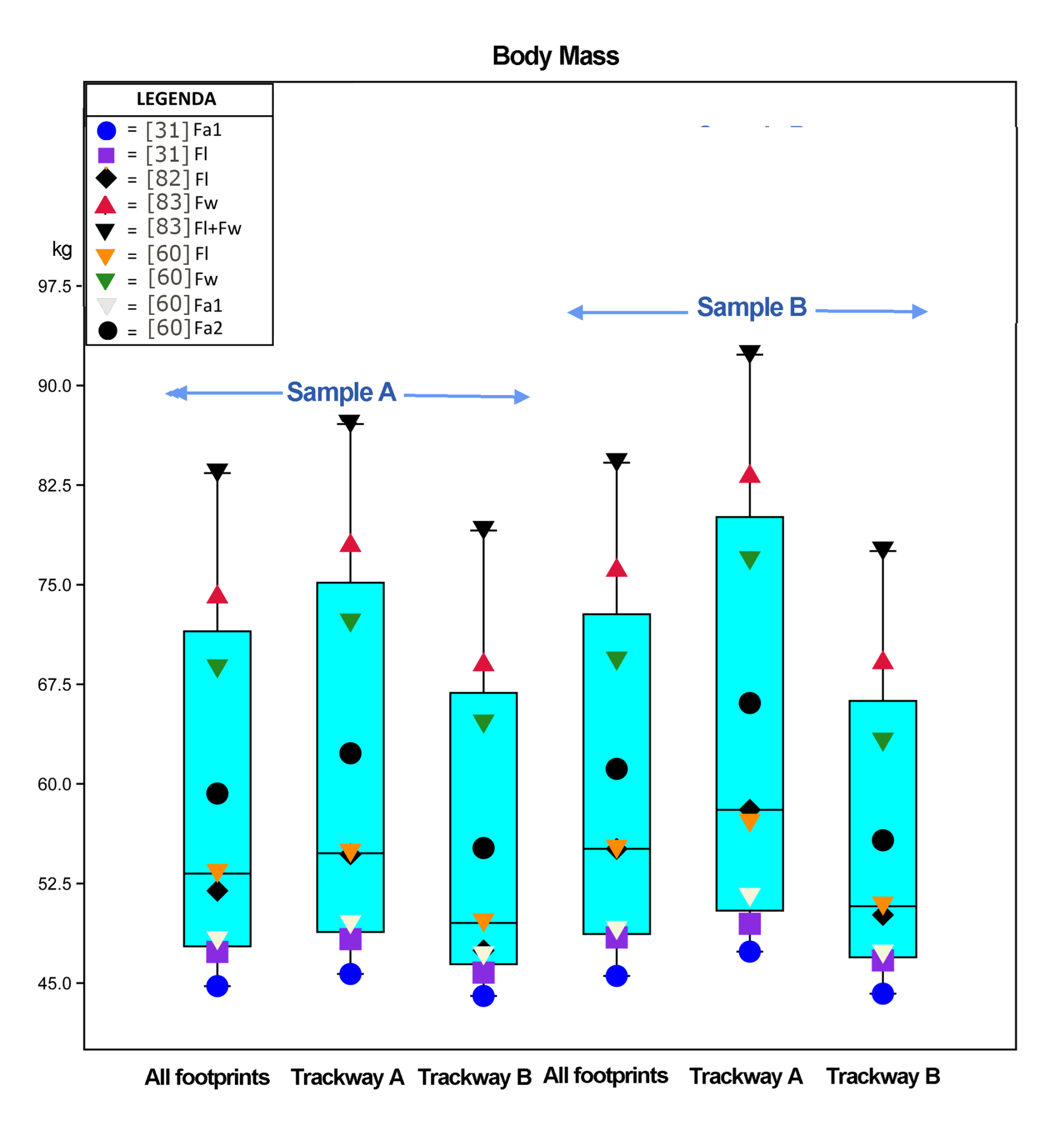

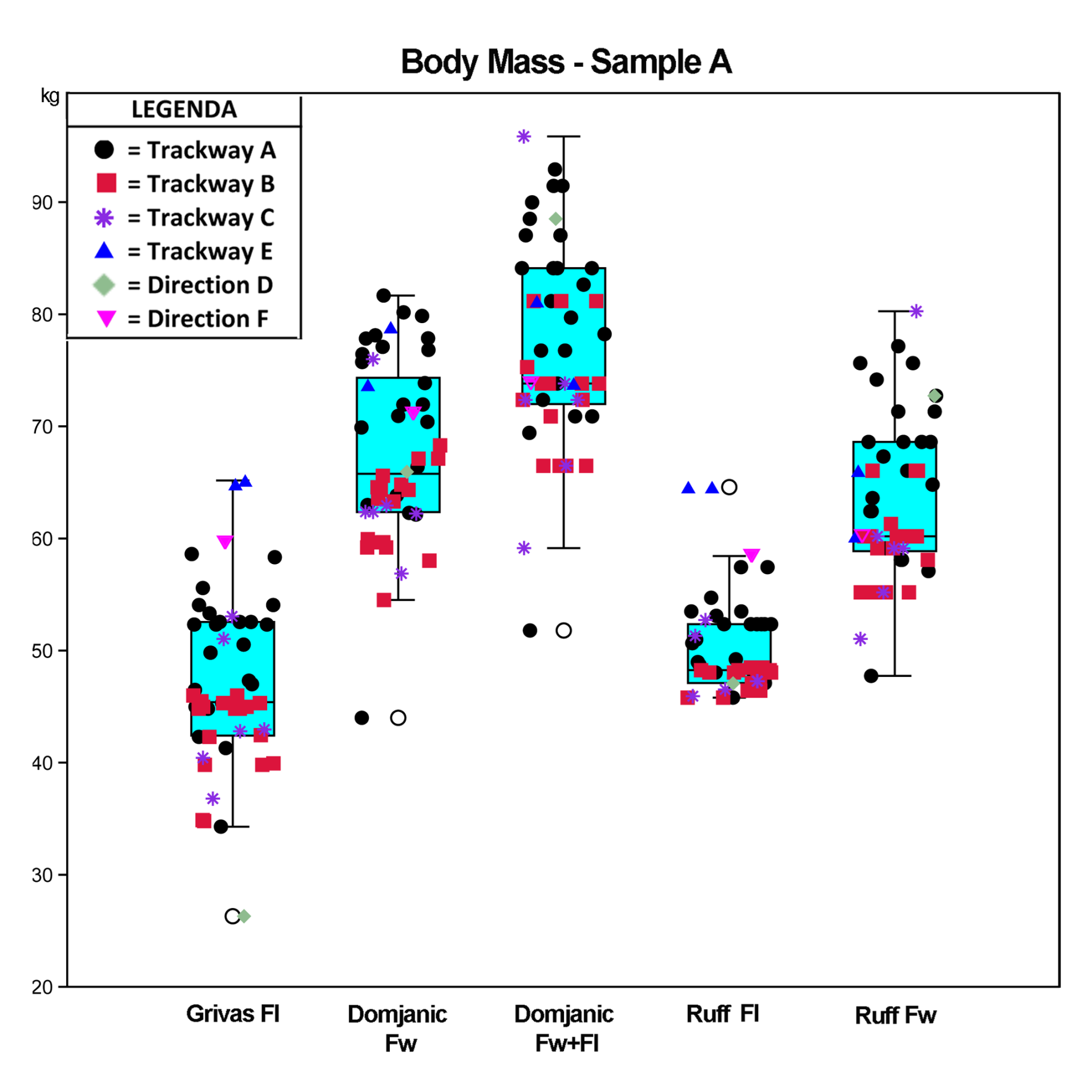

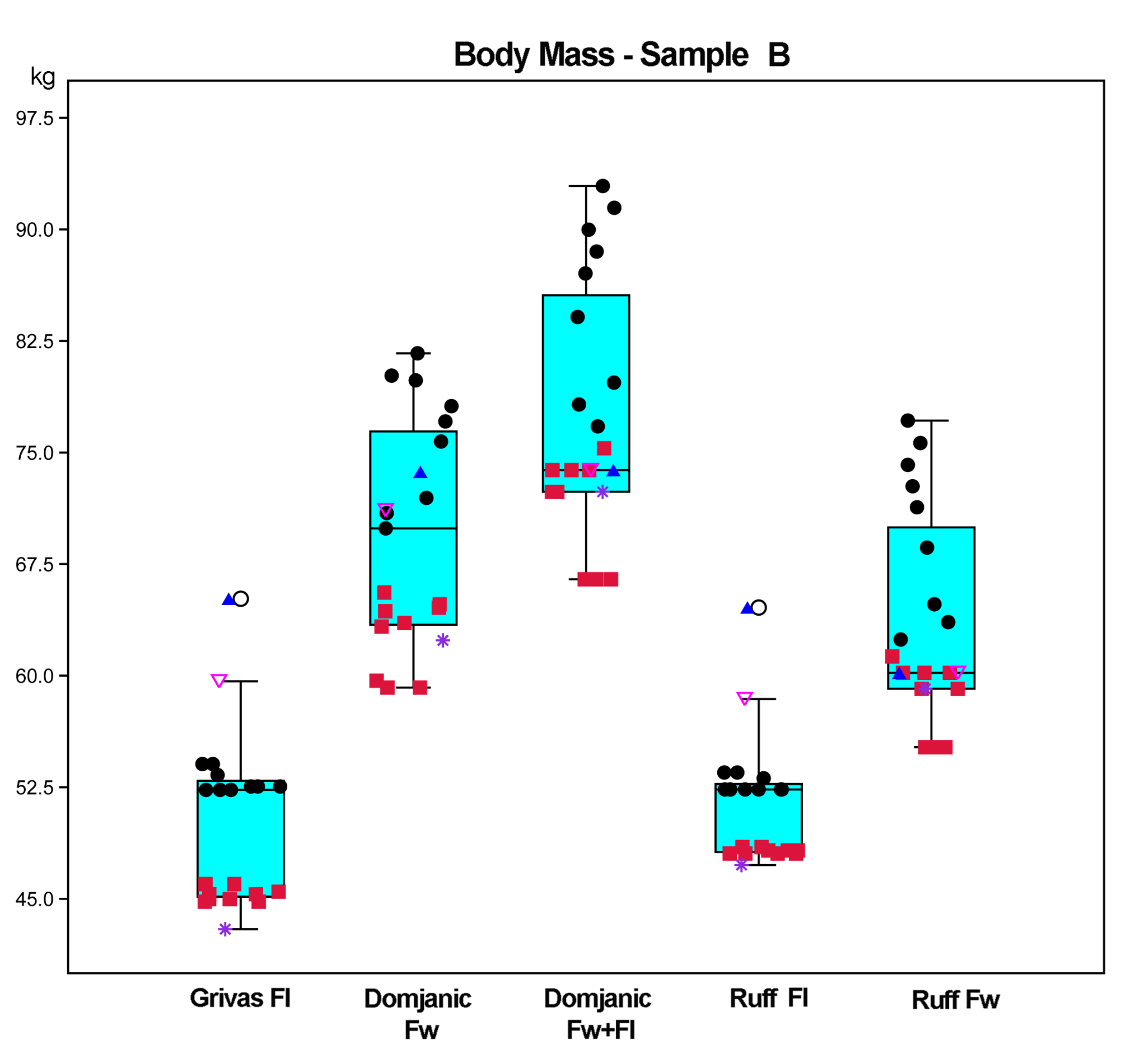

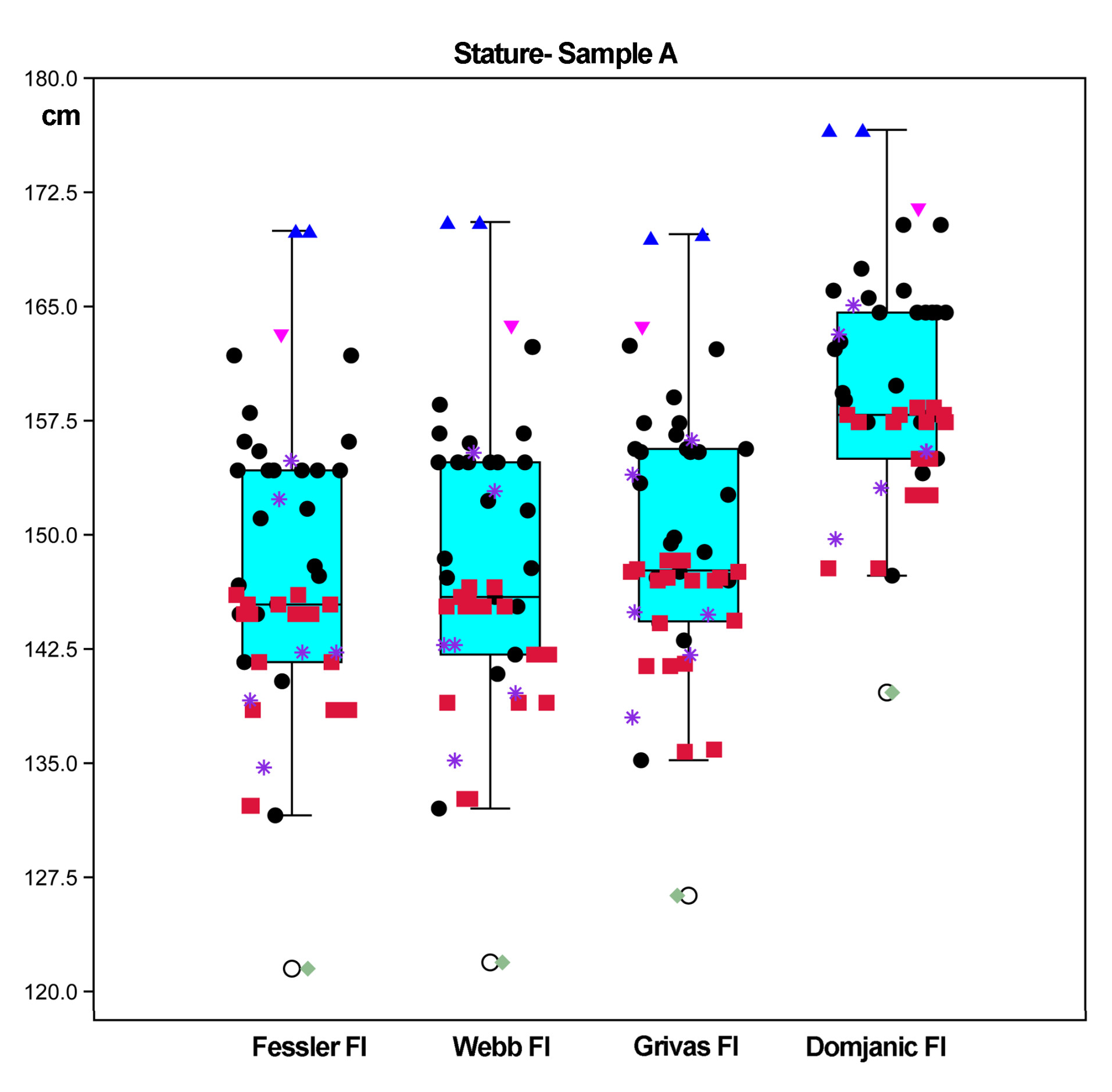

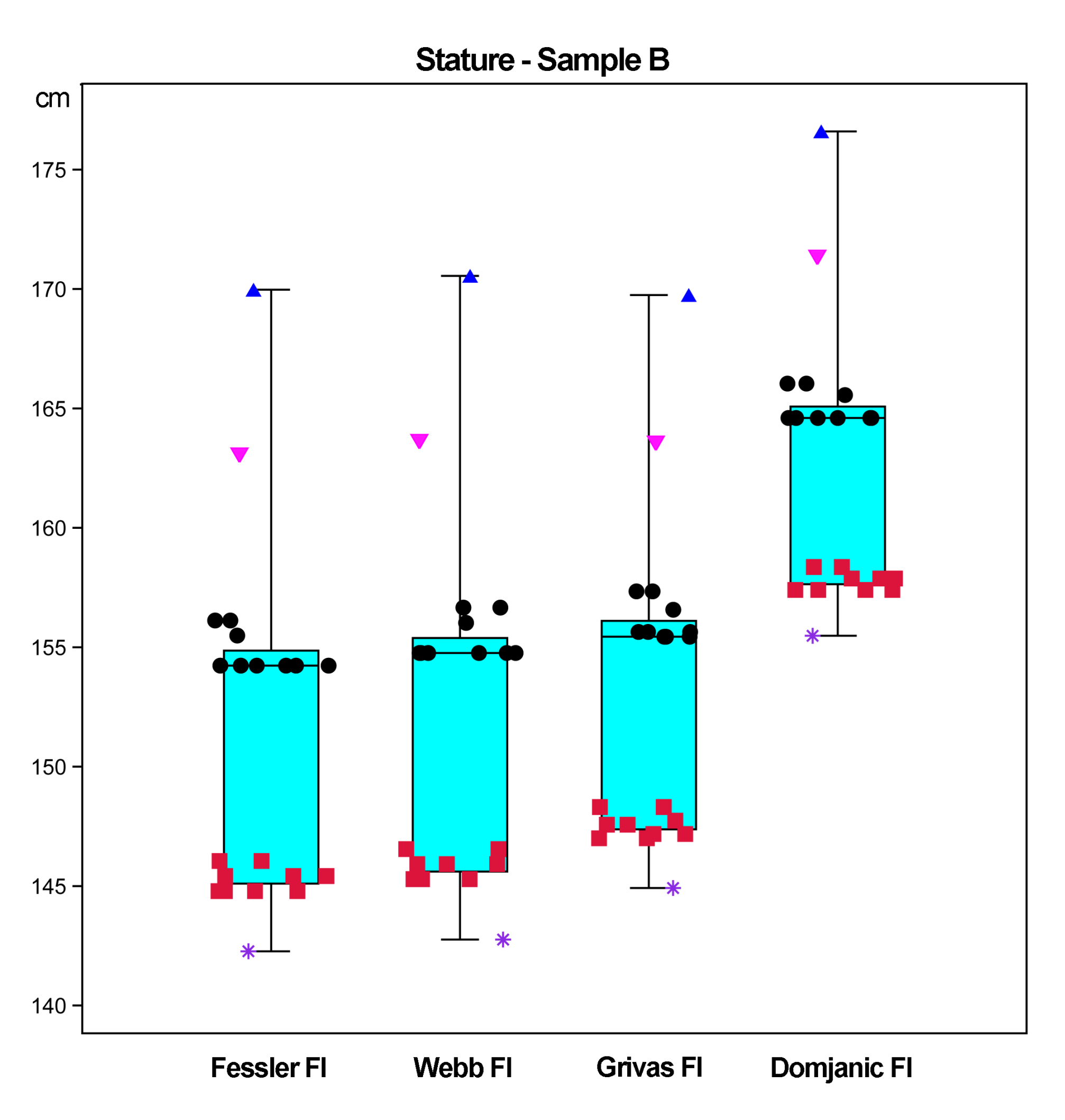

Box Plots

Normality Tests

One-Way ANOVA Repeated Measurements

Principal Component Analysis

3.2. Comparison

3.3. Remarks on the Differences Resulting from the Comparative Analysis Obtained by Using Footprints and Inferred Fleshy Foot Dimensions

4. Discussion

4.1. The Intriguing Matter of the Reliability of Body Size Estimates

4.2. Comparison Among Body Size Estimated at Different Sites and Related Issues: A Short Account

4.3. Glancing at the Body Size Estimated from Bone Dimensions

4.4. Notes About the Comparison Among Foresta/Devil’s Trails Body Size Estimates of and Those Derived from Bone Dimensions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Acronyms and Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BM | Body mass |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| Dir | Direction |

| F/DT | Foresta/Devil’s Trails |

| Fa1 | Footprint area calculated by tracing the perimeter of the footprint through a polyline of at least 40 points |

| Fa2 | Footprint area calculated according to [31] |

| Fl | Inferred foot length |

| Fw | Inferred foot width |

| fpD | Footprint dimension |

| ftD | Inferred dimension of the flesh foot |

| ka | Kilo years |

| Ma | Million years |

| rFl and Fl (in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11) | Footprint length |

| rFw and Fw (in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11) | Footprint width |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| ST | Stature |

| Tr | Trackway |

References

- Topinard, P. L’Anthropologie, 2nd ed.; Reinwald: Paris, France, 1857; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.M. Lehrbuch der Anthropologie in Systematischer Darstellung: Mit Besonderer Berücksichtigung der Anthropologischen Methoden; Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Pales, L. Les Empreintes de Pieds Humains Dans les Cavernes: Les Empreintes du Reseau Nord de la Caverne de Niaux (Ariege); Masson: Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.R.; Morse, S.A. Human Footprints: Fossilised Locomotion? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, K. Prehistoric Avian, Mammalian and H. Sapiens Footprint-Tracks from Intertidal Sediments as Evidence of Human Palaeoecology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 2010; pp. 1–593. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.R.; Reynolds, S.C. Inferences from Footprints: Archaeological Best Practice. In Reading Prehistoric Human Tracks. Methods & Material; Pastoors, A., Lenssen-Erz, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.R.; Bustos, D.; Odess, D.; Urban, T.M.; Lallensack, J.N.; Budka, M.; Santucci, V.L.; Martinez, P.; Wiseman, A.L.A.; Reynolds, S.C. Walking in mud: Remarkable Pleistocene human trackways from White Sands National Park (New Mexico). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 249, 106610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavdekar, S.B.; Sathe, S.; Jani, P. Prediction of weight of Indian children aged up to two years based on foot-length: Implications for emergency areas. Indian Pediatr. 2006, 43, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanchan, T.; Menezes, R.G.; Moudgil, R.; Kaur, R.; Kotian, M.S.; Garg, R.K. Stature estimation from foot dimensions. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 179, 241.e1–241.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, K. Determination of Stature from Foot and Its Segments in a North Indian Population. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2008, 29, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanti, B.B.; Agrawal, D.; Mishra, K.; Samantsinghar, P.; Chinara, P.K. Estimation of height of an individual from foot lenght: A study on the population of Odisha. Int. J. Rev. Life Sci. 2012, 2, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, M.; Tyagi, A.K.; Ranga, V.K.; Rani, Y.; Murari, A. Stature estimates from foot dimensions. J. Punjab. Acad. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2011, 11, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H.B.M.A.; Nataraja Moorthy, T. Estimation of stature from foot outline measurements in Ibans of East Malaysia by regression analysis. Int. J. Biomed. Adv. Res. 2013, 4, 889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Kautilya, D.V.; Bodkha, P.; Poothanathan, P. Determination of stature and sex from anthropometry of the foot among south Indians. Int. J. Rev. Life Sci. 2013, 3, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sherke, A.R.; Tamgire, D.W. Correlations of stature with foot length in Andhra region. Int. J. Biomed. Res. 2013, 4, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S.; Swathi, S.; Athavale, A. Estimation of stature from hand and foot measurements in a rare tribe of Kerala State in India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, HC01–HC04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.R.; Akhter, N.; Ali, R.; Farrukh, R.; Aziz, K. A Study on estimation of stature from foot length. Prof. Med. J. 2015, 22, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraja Moorthy, T.; Khan, H.B.M.A. Stature estimation from anthropometric measurements of footprints in Lun Bawang, an indigenous ethnic group of East Malaysia by linear regression analysis. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2016, 45, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nataraja Moorthy, T.; Mostapa, A.M.B.; Boominathan, R.; Raman, N. Stature estimation from footprint measurements in Indian Tamils by regression analysis. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 4, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraja Moorthy, T.; Ling, A.Y.; Sarippudin, S.A.; Hassan, F.N.H. Estimation of stature from footprint and foot outline measurements in Malaysian Chinese. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 46, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, K. Individualizing characteristics of footprints in Gujjars of North India—Forensic aspects. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007, 169, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, K. Establishing correlation of footprints with body weight–Forensic aspects. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 179, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, K. Estimation of stature from footprint and foot outline dimensions in Gujjars of North India. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 175, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, K.; Kanchan, T.; Passi, N. Estimation of stature from the foot and its segments in a sub-adult female population of North India. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2011, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P.; Meena, M.C.; Rani, Y.; Sharma, G.K. Stature estimations from the dimensions of foot in females. Antrocom Online J. Anthropol. 2013, 9, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shariff, S.M.; Thamilvaani, M.; Shariff, A.A.; Merican, A.F. Evaluation of Foot Arch in Adult Women: Comparison between Five Different Footprint Parameters. Sains Malays. 2017, 46, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.H.; Lodha, A.S.; Das, S. Stature estimation from footprint: A study on Central Indian population. Eur. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 4, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Awais, M.; Naeem, F.; Rasool, R.; Mahmood, S. Identification of sex from footprint dimensions using machine learning: A study on population of Punjab in Pakistan. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abledu, J.K.; Abledu, G.K.; Offei, E.B.; Antwi, E.M. Determination of Sex from Footprint Dimensions in a Ghanaian Population. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyeampong, J.G. Correlation of Sex, Height and Handedness with Anthropometric Foot and Hand Measurement of Young Adults Ghanaians. Master’s Thesis, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, 2017; pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall, H.L.; Hatala, K.G.; Wunderlich, R.A.; Richmond, B.G. Hominin stature, body mass, and walking speed estimates based on 1.5 million-year-old fossil footprints at Ileret, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 2013, 64, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, I.A.; Kamal, N.N. Stature and Body Weight Estimation from Various Footprint Measurements among Egyptian Population. J. Forensic Sci. 2010, 55, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubike, E.A.; Ibeabuchi, N.M.; Olabiyi, O.A.; Nandi, M.E. Stature Estimation from Footprint Dimensions in an Adult Nigerian Student Population. J. Forensic Sci. Med. 2018, 4, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamtürk, D.; Duyar, I. Age-Related Factors in the Relationship Between Foot Measurements and Living Stature and Body Weight. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeybek, G.; Ergur, I.; Demiroglu, Z. Stature and gender estimation using foot measurements. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 181, 54.e1–54.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.; Muñoz-Barús, J.I.; Wasterlain, S.; Cunha, E.; Vieira, D.N. Predicting adult stature from metatarsal length in a Portuguese population. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 193, 131.e1–131.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reel, S.; Rouse, S.; Vernon, W.; Doherty, P. Estimation of stature from static and dynamic footprints. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 219, 283e1–283e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrova, P.; Beňuš, R.; Masnicová, S.; Obertová, Z.; Kramárová, D.; Kyselicová, K.; Dörnhöferová, M.; Bodoriková, S.; Neščáková, E. Estimation of stature using hand and foot dimensions in Slovak adults. Legal Med. 2015, 17, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, N.-I. Sex and Stature Estimation Using Hand and Handprint Measurements in a Western Australia Population. Master’s Thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia, 2010; pp. 1–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, N.-I.; Hemy, N.; Franklin, D. Estimation of sex from hand and handprint dimensions in a Western Australian population. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 221, 154.e1–154.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemy, N.; Flavel, A.; Ishak, N.-I.; Franklin, D. Sex estimation using anthropometry of feet and footprints in a Western Australian population. Forensic Sci. Int. 2013, 231, 402.e1–402.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemy, N.; Flavel, A.; Ishak, N.-I.; Franklin, D. Estimation of stature using anthropometry of feet and footprints in a Western Australian population. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2013, 20, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, M.; Gleser, G. Estimation of stature from long bones of American whites and Negroes. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1952, 10, 463–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, M.; Gleser, G.C. A re-evaluation of estimation of stature based on measurement of stature taken during life and of long bones after death. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1958, 16, 79–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.W. Comparative Anthropometry of the Foot; United States Army, Natick Research and Development Laboratories: Natick, MA, USA, 1982; 320p. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, C.C.; Churchill, T.; Clauser, C.E.; Bradtmiller, B.; McConville, J.T.; Tebbetts, I.; Walker, R.A. 1988 Anthropometric Survey of U.S. Army Personnel: Methods and Summary Statistics; United States Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center: Natick, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 1–638. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.T. The Foot Length to Stature Ratio: A Study of Racial Variance. Unpublished. Master of Art Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 1990; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Wyatt, H.R.; Thompson, H.; Peters, J.C.; Hill, J.O. Pedometer-Measured Physical Activity and Health Behaviors in U.S. Adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1819–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, P.J.; Sarjeant, W.A. Lower Cretaceous dinosaur footprints from the Peace River Canyon, British Columbia, Canada. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1979, 28, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasenko, M.R. Quantitative and qualitative data of footprints produced by Asian (Elephas maximus) and African (Loxodonta africana) elephants and with a discussion of significance towards fossilized proboscidean footprints. Quat. Int. 2017, 443, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, M.R.; Panarello, A. How many hominins walked on the slope of the Foresta ignimbrite deposit (Roccamonfina volcano, central Italy)? J. Mediterr. Earth Sci. 2023, 15, 229–271. [Google Scholar]

- Duveau, J. From footprint morphometrics to the stature of fossil hominins: A common but uncertain estimate. L’Anthropologie 2022, 126, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duveau, J.; Berillon, G.; Verna, C.; Laisné, G.; Cliquet, D. The composition of a Neandertal social group revealed by the hominin footprints at Le Rozel (Normandy, France). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19409–19414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.; Mansilla, F.; Arsuaga, J.L.; Santos, E.; Jiménez-Díaz, A.; Egea-González, I. The speed and displacement of the Laetoli Site G track-maker hominins. Ichnos 2022, 29, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastoors, A.; Lenssen-Erz, T.; Ciqae, T.; Kxunta, U.; Thao, T.; Bégouën, R.; Biesele, M.; Clottes, J. Tracking in Caves: Experience based reading of Pleistocene human footprints in French caves. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2015, 25, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastoors, A.; Lenssen-Erz, T.; Breuckmann, B.; Ciqae, T.; Kxunta, U.; Rieke-Zapp, D.; Thao, T. Experience based reading of Pleistocene human footprints in Pech-Merle. Quat. Int. 2017, 430, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N. Steps from History. In Reading Prehistoric Human Tracks; Pastoors, A., Lenssen-Erz, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Carretero, J.; Rodríguez, L.; García-González, R.; Arsuaga, J.; Gómez-Olivencia, A.; Lorenzo, C.; Bonmatí, A.; Gracia, A.; Martínez, I.; Quam, R. Stature estimation from complete long bones in the Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sima de los Huesos, Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 2012, 62, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablos, A.; Lorenzo, C.; Martínez, I.; Bermúdez de Castro, J.M.; Martinón-Torres, M.; Carbonell, E.; Arsuaga, J.L. New foot remains from the Gran Dolina-TD6 Early Pleistocene site (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 2012, 63, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, C.B.; Wunderlich, R.E.; Hatala, K.G.; Tuttle, R.H.; Hilton, C.E.; D’Août, K.; Webb, D.M.; Hallgrímsson, B.; Musiba, C.; Baksh, M. Body mass estimation from footprint size in hominins. J. Hum. Evol. 2021, 156, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santello, L. Analysis of a Trampled Formation: The Brown Leucitic Tuff (Roccamonfina Volcano, Southern Italy). Ph.D. Thesis, Padua University, Padova, Italy, 2010; 136p. [Google Scholar]

- Mietto, P.; Avanzini, M.; Rolandi, G. Human footprints in Pleistocene volcanic ash. Nature 2003, 422, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, M.A. Il Geosito Delle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. In 2001–2021: Vent’anni di Ricerche Sulle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. Dalla Leggenda Alla Realtà Scientifica; Mietto, P., Panarello, A., Di Vito, M.A., Eds.; Misc. INGV: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 64, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Panarello, A.; Palombo, M.R.; Biddittu, I.; Di Vito, M.A.; Farinaro, G.; Mietto, P. On the devil’s tracks: Unexpected news from the Foresta ichnosite (Roccamonfina volcano, central Italy). J. Quat. Sci. 2020, 35, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarello, A.; Palombo, M.R.; Biddittu, I.; Mietto, P. Fifteen years along the “Devil’s Trails”: New data and perspectives. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 2017, 30, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Panarello, A.; Santello, L.; Farinaro, G.; Bennett, M.R.; Mietto, P. Walking along the oldest human fossil pathway (Roccamonfina volcano, Central Italy)? J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 13, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarello, A.; Farinaro, G.; Mietto, P. L’icnosito Della Località “Foresta” di Tora e Piccilli e le Impronte Umane Fossili. In 2001–2021: Vent’anni di Ricerche Sulle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. Dalla Leggenda Alla Realtà Scientifica; Mietto, P., Panarello, A., Di Vito, M.A., Eds.; Misc. INGV: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 64, pp. 123–164. [Google Scholar]

- Panarello, A.; Farinaro, G.; Mietto, P. Il dataset dimensionale completo delle “Ciampate del diavolo”. In 2001–2021: Vent’anni di Ricerche Sulle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. Dalla Leggenda Alla Realtà Scientifica; Mietto, P., Panarello, A., Di Vito, M.A., Eds.; Misc. INGV: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 64 S1, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Panarello, A.; Farinaro, G.; Mietto, P. Costruzioni geometriche per la creazione del dataset dimensionale completo delle “Ciampate del diavolo”. In 2001–2021: Vent’anni di Ricerche Sulle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. Dalla Leggenda Alla Realtà Scientifica; Mietto, P., Panarello, A., Di Vito, M.A., Eds.; Misc. INGV: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 64 S2, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Panarello, A.; Farinaro, G.; Mietto, P. Atlante Visuale Delle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. In 2001–2021: Vent’anni di Ricerche Sulle “Ciampate del Diavolo”. Dalla Leggenda Alla Realtà Scientifica; Mietto, P., Panarello, A., Di Vito, M.A., Eds.; Misc. INGV: Rome, Italy, 2022; Volume 64 S3, pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, C.W.; McCrea, R.T.; Cawthra, H.C.; Lockley, M.G.; Cowling, R.M.; Marean, C.W.; Thesen, G.H.H.; Pigeon, T.S.; Hattingh, S. A New Pleistocene Hominin Tracksite from the Cape South Coast, South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helm, C.W.; McCrea, R.T.; Lockley, M.G.; Cawthra, H.C.; Thesen, G.H.H.; Mwankunda, J.M. Late Pleistocene vertebrate trace fossils in the Goukamma Nature Reserve, Cape south coast, South Africa. Palaeontol. Afr. 2018, 52, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, C.W.; Lockley, M.G.; Cole, K.; Noakes, T.D.; McCrea, R.T. Hominin tracks in southern Africa: A review and an approach to identification. Palaeontol. Afr. 2019, 53, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, C.W.; Cawthra, H.C.; Hattingh, R.; Hattingh, S.; McCrea, R.T.; Thesen, G.H.G. Pleistocene vertebrate trace fossils of Robberg Nature Reserve. Palaeontol. Afr. 2019, 54, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Altamura, F.; Bennett, M.R.; Marchetti, L.; Melis, R.T.; Reynolds, S.C.; Mussi, M. Ichnological and archaeological evidence from Gombore II OAM, Melka Kunture, Ethiopia: An integrated approach to reconstruct local environments and biological presences between 1.2 and 0.85 Ma. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 244, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.; Lewis, S.G.; De Groote, I.; Duffy, S.M.; Bates, M.; Bates, R.; Hoare, P.; Lewis, M.; Parfitt, S.A.; Peglar, S.; et al. Hominin Footprints from Early Pleistocene Deposits at Happisburgh, UK. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, F.; Bennett, M.R.; D’Août, K.; Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S.; Melis, R.T.; Reynolds, S.C.; Mussi, M. Archaeology and ichnology at Gombore II-2, Melka Kunture, Ethiopia: Everyday life of a mixedage hominin group 700,000 years ago. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lumley, M.-A.; Lamy, P.; Mafart, B. Une empreinte de pied humain acheuléen dans la dune littorale du site de Terra Amata. Ensemble stratigraphique C1b. In Terra Amata: Nice, Alpes-Maritimes, France. Tome II: Palynologie, Anthracologie, Faunes, Mollusques, Ecologie et Biogéomorphologie, Paléoanthropologie, Empreinte de Pied Humain, Coprolithes; de Lumley, H., Ed.; CNRS: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 483–507. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, I.; Markó, A.; Hyodo, M.; Strickson, C.; Falkingham, P.L. A re-analysis of Chibanian Pleistocene tracks from Vértesszȍlȍs, Hungary, employing photogrammetry and 3D analysis. Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 2021, 91, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, F.; Lehmann, J.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, B.; Urban, B.; van Kolfschoten, T.; Verheijen, I.; Conard, N.J.; Serangeli, J. Fossil footprints at the late Lower Paleolithic site of Schöningen (Germany): A new line of research to reconstruct animal and hominin paleoecology. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2023, 310, 108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, F.; Serangeli, J. A tale of many tracks: An overview of fossil proboscidean footprints at Paleolithic sites around the world, with a particular focus on Schöningen, in Germany. J. Mediterr. Earth Sci. 2023, 15, 347–368. [Google Scholar]

- Grivas, T.B.; Mihas, C.; Arapaki, A.; Vasiliadis, E. Correlation of foot length with height and weight in school age children. J. Forensic Legal Med. 2008, 15, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domjanic, J.; Seidler, H.; Mitteroecker, P. A Combined Morphometric Analysis of Foot Form and Its Association with Sex, Stature, and Body Mass. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2015, 157, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S. Further research of the Willandra Lakes fossil footprints site, southeastern Australia. J. Hum. Evol. 2007, 52, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, D.M.T.; Haley, K.J.; Lal, R.D. Sexual dimorphism in foot length proportionate to stature. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2005, 32, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarello, A. A snapshot on some everyday actions of a Middle Pleistocene hominin: The Trackway B at the Devil’s Trails palaeontological site (Tora e Piccilli, Caserta, Central Italy). J. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 98, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, D.; Pisoni, R.; Purves, R. Statistics, 4th ed.; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2007; 608p. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, H.; Feldt, L.S. Estimation of the Box correction for degrees of freedom from sample data in randomized block and split-plot designs. J. Educ. Stat. 1976, 1, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhouse, S.W.; Geisser, S. On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika 1959, 24, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saborit, G.; Mondanaro, A.; Melchionna, M.; Serio, C.; Carotenuto, F.; Tavani, S.; Modafferi, M.; Panarello, A.; Mietto, P.; Raia, P.; et al. A dynamic analysis of Middle Pleistocene human walking gait adjustment and control. Ital. J. Geosci. 2019, 138, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A. On growth and form. Nature 1917, 100, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blueweiss, L.; Fox, H.; Kudzma, V.; Nakashima, D.; Peters, R.; Sams, S. Relationships between body size and some life history parameters. Oecologia 1978, 37, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, S.L.; Calder III, W.A. Body size, physiological time, and longevity of homeothermic animals. Q. Rev. Biol. 1981, 56, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damuth, J.D.; MacFadden, B.J. (Eds.) Body Size in Mammalian Paleobiology: Estimation and Biological Implications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McNab, B.K. The Physiological Significance of Body Size. In Body Size in Mammalian Paleobiology: Estimation and Biological Implications; Damuth, J.D., Damuth, J., MacFadden, B.J., John, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.H.; Marquet, P.A.; Taper, M.L. Evolution of body size: Consequences of an energetic definition of fitness. Am. Nat. 1993, 142, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.H.; Kodric-Brown, A.; Sibly, R.M. Chapter Nine. On Body Size and Life History of Mammals. In Body Size: Linking Pattern and Process Across Space, Time and Taxonomic Group; Smith, F.A., Lyons, S.K., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; pp. 206–234. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.H.; Burger, J.R.; Hou, C.; Hall, C.A. The pace of life: Metabolic energy, biological time, and life history. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2022, 62, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, P.A.; Navarrete, S.A.; Castilla, J.C. Body size, population density, and the energetic equivalence rule. J. Anim. Ecol. 1995, 64, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibly, R.M.; Brown, J.H. Effects of body size and lifestyle on evolution of mammal life histories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 17707–17712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.A.; Lyons, S.K. (Eds.) Body Size: Linking Pattern and Process across Space, Time and Taxonomic Group; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Magalhaes, J.P.; Costa, A.J. A database of vertebrate longevity records and their relation to other life-history traits. J. Evol. Biol. 2009, 22, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, P.; Korem, Y.; Moran, U.; Mayo, A.; Alon, U. The mass-longevity triangle: Pareto optimality and the geometry of life-history trait space. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, E.G.; Herfindal, I.; Solberg, E.J.; Sæther, B.E. Home ranges, habitat and body mass: Simple correlates of home range size in ungulates. Proc. R. Soc. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20161234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, S.S.B. Estimation of Body Size in Fossil Mammals. In Methods in Paleoecology. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology; Croft, D., Su, D., Simpson, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, S.K.; Smith, F.A. Macroecological Patterns of Body Size in Mammals Across Time and Space. In Animal Body Size: Linking Pattern and Process Across Space, Time, and Taxonomic Group; Smith, F.A., Lyons, S.K., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019; pp. 116–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, J.; Konarzewski, M.; Czarnoleski, M. Coevolution of body size and metabolic rate in vertebrates: A life-history perspective. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1393–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingerich, P.D.; Smith, B.H.; Rosenberg, K. Allometric scaling in the dentition of primates and prediction of body weight from tooth size in fossils. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 1982, 58, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, P.S. How big is a giant? The importance of method in estimating body size of extinct mammals. J. Mammal. 2002, 83, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, W.I.; Hepworth-Bell, J.; Falkingham, P.L.; Bates, K.T.; Brassey, C.A.; Egerton, V.M.; Manning, P.L. Minimum convex hull mass estimations of complete mounted skeletons. Biol. Lett. 2012, 8, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassey, C.A.; Gardiner, J.D. An advanced shape-fitting algorithm applied to quadrupedal mammals: Improving volumetric mass estimates. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 150302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larramendi, A. Shoulder height, body mass, and shape of proboscideans. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2016, 61, 537–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Manucci, F. Resizing Lisowicia bojani: Volumetric body mass estimate and 3D reconstruction of the giant Late Triassic dicynodont. Hist. Biol. 2019, 33, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, N.E.; Evans, D.C. The accuracy and precision of body mass estimation in non-avian dinosaurs. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1759–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Antonelli, M.; Palombo, M.R.; Rossi, A.; Agostini, S. Drone testing for 3D reconstruction of massive mounted skeletons in museums: The case of Mammuthus meridionalis from Madonna della Strada (Scoppito, L’Aquila). Hist. Biol. 2022, 34, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, L.M. Footprints: Collection, Analysis, and Interpretation; Charles, C., Ed.; Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.R.; Budka, M. Digital Technology for Forensic Footwear Analysis and Vertebrate Ichnology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle, R.; Webb, D.; Weidl, E.; Baksh, M. Further Progress on the Laetoli Trails. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1990, 17, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, S.A.; Bennett, M.R.; Gonzalez, S.; Huddart, D. Techniques for verifying human footprints: Reappraisal of pre-Clovis footprints in Central Mexico. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2010, 29, 2571–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, S.A.; Bennett, M.R.; Liutkus-Pierce, C.; Thackeray, F.; McClymont, J.; Savage, R.; Crompton, R.H. Holocene Footprints in Namibia: The Influence of Substrate on Footprint Variability. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2013, 151, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSilva, J.; McNutt, E.; Benoit, J.; Zipfel, B. One small step: A review of Plio-Pleistocene hominin foot evolution. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2019, 168, 63–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvedere, M.; Budka, M.; Wiseman, A.; Bennett, M.R. When is enough, enough? Questions of Sampling in Vertebrate Ichnology. Paleontology 2021, 64, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkingham, P.L.; Bates, K.T.; Avanzini, M.; Bennett, M.; Bordys, E.M.; Breithaup, B.H.; Castanera, D.; Citton, P.; Díaz-Martínez, I.; Farlow, J.O.; et al. A Standard Protocol for Documenting Modern and Fossil Ichnological Data. Palaeontology 2018, 61, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, E.J.; Hatala, K.G.; Miller, C.; Adams, J.; Casana, J.; Deane, A.S.; Dominy, N.J.; Fabian, K.; Fannin, L.D.; Gaughan, S.; et al. Footprint evidence of early hominin locomotor diversity at Laetoli, Tanzania. Nature 2021, 600, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamtürk, D.; Özbal, R.; Gerritsen, F.; Duyar, İ. Analysis and Interpretation of Neolithic Period Footprints from Barcın Höyük, Turkey. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2018, 18, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos, D.; Jakeway, J.; Urban, T.M.; Holliday, V.T.; Fenerty, B.; Raichlen, D.A.; Budka, M.; Reynolds, S.C.; Allen, B.D.; Love, D.W.; et al. Footprints preserve terminal Pleistocene hunt? Human-sloth interactions in North America. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.R.; Bustos, D.; Pigati, J.S.; Springer, K.B.; Urban, T.M.; Holliday, V.T.; Reynolds, S.C.; Budka, M.; Honke, J.S.; Hudson, A.M.; et al. Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 2021, 373, 1528–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S.; Cupper, M.L.; Robins, R. Pleistocene human footprints from the Willandra Lakes, southeastern Australia. J. Hum. Evol. 2006, 50, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Milàn, J. Variations in the morphology of emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) tracks reflecting differences in walking pattern and substrate consistency: Ichnotaxonomic implications. Palaeontology 2006, 49, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, F.; Palombo, M.R.; Pillola, G.L.; Ibba, A. Tracks and trackways of Praemegaceros cazioti (Dépèret, 1897) (Artiodactyla, Cervidae) in the Pleistocene coastal deposits from Sardinia (Western Mediterranean, Italy). Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 2007, 46, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Eren, M.I.; Durant, A.; Neudorf, C.; Haslam, M.; Shipton, C.; Bora, J.; Korisettar, R.; Petraglia, M. Experimental examination of animal trampling effects on artifact movement in dry and water saturated substrates: A test case from South India. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 3010–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, B.F.; Hasiotis, S.T.; Hirmas, D.R. Empirical determination of physical controls on megafaunal footprint formation through neoichnological experiments with elephants. Palaios 2012, 27, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A.R.; Hasiotis, S.T.; Gong, E.; Lim, J.D.; Brewer, E.D. A new experimental setup for studying avian neoichnology and the effects of grain size and moisture content on tracks: Trials using the domestic chicken (Gallus gallus). Palaios 2017, 32, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, D.; Strasser, A.; Meyer, C. Formation and Taphonomy of Human Footprints in Microbial Mats of Present-Day Tidal-flat Environments: Implications for the Study of Fossil Footprints. Ichnos 2009, 16, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, K.G.; Roach, N.T.; Ostrofsky, K.R.; Wunderlich, R.E.; Dingwall, H.L.; Villmoare, B.A.; Green, D.J.; Harris, J.W.K.; Braun, D.R.; Richmond, B.G. Footprints reveal direct evidence of group behaviour and locomotion in Homo erectus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, R. Footprint-Tracks of People and Animals. In Prehistoric Coastal Communities: The Mesolithic in Western Britain; Bell, M., Ed.; CBA Research Report: York, UK, 2007; Volume 149, pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Citton, P.; Romano, M.; Salvador, I.; Avanzini, M. Reviewing the upper Pleistocene human footprints from the ‘Sala dei Misteri’ in the Grotta della Bàsura (Toirano, northern Italy) cave: An integrated morphometric and morpho-classificatory approach. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017, 169, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Citton, P.; Salvador, I.; Arobba, D.; Rellini, I.; Firpo, M.; Negrino, F.; Zunino, M.; Starnini, E.; Avanzini, M. A multidisciplinary approach to a unique palaeolithic human ichnological record from Italy (Bàsura Cave). eLife 2019, 8, e45204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzini, M.; Salvador, I.; Starnini, E.; Arobba, D.; Caramiello, R.; Romano, M.; Citton, P.; Rellini, I.; Firpo, M.; Zunino, M.; et al. Following the Father Steps in the Bowels of the Earth: The Ichnological Record from the Bàsura Cave (Upper Palaeolithic, Italy). In Reading Prehistoric Human Tracks. Methods & Material; Pastoors, A., Lenssen-Erz, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Zunino, M.; Starnini, E.; Arobba, D.; Avanzini, M.; Caramiello, R.; Citton, P.; Clementi, L.C.; Firpo, M.; Giannotti, S.; Negrino, F.; et al. Toirano revisited: Nuove ricerche geoarcheologiche e paleontologiche nella Grotta della Bàsura (Toirano, SV). Primi risultati dello studio multidisciplinare delle tracce antropiche e dei depositi a fauna del Pleistocene superiore. Riv. Di Sci. Preist. 2023, 73, 371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Carretero, J.-M.; Rodríguez, L.; García-González, R.; Quam, R.-M.; Arsuaga, J.L. Exploring bone volume and skeletal weight in the Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sima de los Huesos site (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). J. Anat. 2018, 233, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pablos, A.; Arsuaga, J.L. Tarsals from the Sima de los Huesos Middle Pleistocene site (Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). Anat. Rec. 2024, 307, 2635–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lumley, M.-A. Chapitre 3. In ventaire. Répertition stratigraphique. Rèpresentation anatomique. In Les Restes Humaines Pléistocèns de la Caune de l’Arago; Tome, I.X., de Lumley, M.-A., Eds.; CNRS Editions: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 21–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, T. Chapitre 15. La corpulence de l’Homme de la Caune de l’Arago: Stature et masse corporelle. In Les Restes Humaines Pléistocèns de la Caune de l’Arago; Tome, I.X., de Lumley, M.-A., Eds.; CNRS Editions: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 615–693. [Google Scholar]

| Footprint Measurements * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trackway/Direction | Footprint | Footprint Length (rFl) (cm) | Footprint Width (rFw) (cm) | rFw/rFl × 100 (Fin) | Footprint Area 1 (Fa1) ** (cm2) | Footprint Area 2 (Fa2) *** (cm2) |

| Trackway A | A01-L | 25.7 | 11.1 | 43.2 | 240 | 285.27 |

| A02-R | 25.70 | 11.20 | 43.60 | 229.00 | 287.84 | |

| A03-L | 24.00 | 11.20 | 46.70 | 197.00 | 268.8 | |

| A04-R | 25.10 | 11.20 | 44.60 | 222.00 | 281.12 | |

| A05-L | 23.10 | 10.50 | 45.40 | 185.00 | 242.55 | |

| A06-R | 24.10 | 10.20 | 42.30 | 179.00 | 245.82 | |

| A07-L | 23.00 | 10.30 | 44.80 | 173.00 | 236.9 | |

| A08-R | 24.50 | 11.40 | 46.50 | 218.00 | 279.3 | |

| A09-R | 23.00 | 10.70 | 46.50 | 179.00 | 246.1 | |

| A10-L | 20.90 | 9.00 | 43.10 | 135.00 | 188.1 | |

| A11-R | 23.30 | 10.30 | 44.20 | 177.00 | 239.99 | |

| A12-L | 22.50 | 10.40 | 46.20 | 184.00 | 234 | |

| A13-R | 23.40 | 11.00 | 47.00 | 182.00 | 257.4 | |

| A14-L | 22.30 | 11.40 | 51.10 | 190.00 | 254.22 | |

| A16-L | 23.50 | 11.70 | 49.80 | 200.00 | 274.95 | |

| A17-R | 24.80 | 11.20 | 45.20 | 211.00 | 277.76 | |

| A18-L | 24.50 | 11.50 | 46.90 | 217.00 | 281.75 | |

| A21-R | 24.80 | 11.60 | 46.80 | 227.00 | 287.68 | |

| A22-L | 24.50 | 10.70 | 43.70 | 199.00 | 262.15 | |

| A23-R | 24.50 | 10.80 | 44.10 | 204.00 | 264.6 | |

| A24-L | 24.70 | 11.80 | 47.80 | 244.00 | 291.46 | |

| A25-R | 24.50 | 11.70 | 47.70 | 212.00 | 286.65 | |

| A26-L | 24.50 | 10.90 | 44.50 | 212.00 | 267.05 | |

| Trackway B | B00-L | 22.00 | 10.30 | 46.80 | 197.00 | 226.6 |

| B01-R | 22.00 | 11.00 | 50.00 | 194.00 | 242 | |

| B02-L | 23.00 | 10.50 | 45.60 | 206.00 | 241.5 | |

| B03-R | 23.00 | 10.00 | 43.50 | 179.00 | 230 | |

| B04-L | 21.00 | 10.00 | 47.60 | 152.00 | 210 | |

| B05-R | 23.20 | 10.50 | 45.20 | 199.00 | 243.6 | |

| B06-L | 22.50 | 10.00 | 44.40 | 173.00 | 225 | |

| B07-R | 23.00 | 10.50 | 45.60 | 196.00 | 241.5 | |

| B08-L | 22.00 | 11.00 | 50.00 | 201.00 | 242 | |

| B08a-R | 22.50 | 11.00 | 48.90 | 181.00 | 247.5 | |

| B10-R | 21.00 | 10.50 | 50.00 | 167.00 | 220.5 | |

| B11-L | 23.00 | 10.00 | 43.50 | 205.00 | 230 | |

| B12-R | 23.20 | 10.00 | 43.10 | 173.00 | 232 | |

| B13-L | 23.10 | 10.50 | 45.40 | 197.00 | 242.55 | |

| B15-R | 23.10 | 10.60 | 45.90 | 162.00 | 244.86 | |

| B16-L | 23.00 | 10.40 | 45.20 | 179.00 | 239.2 | |

| B18-L | 23.10 | 10.40 | 45.00 | 195.00 | 240.24 | |

| Trackway C | C05-R | 22.60 | 10.40 | 46.00 | 185.00 | 235.04 |

| C07-L | 22.60 | 10.40 | 46.00 | 169.00 | 235.04 | |

| C08-R | 22.10 | 10.50 | 47.50 | 172.00 | 232.05 | |

| C09-L | 21.40 | 12.00 | 56.10 | 194.00 | 256.8 | |

| C10-R | 24.60 | 10.00 | 40.60 | 194.00 | 246 | |

| C12-R | 24.20 | 9.50 | 39.20 | 176.00 | 229.9 | |

| Dir D | D01-R | 19.30 | 11.50 | 59.60 | 138.00 | 221.95 |

| Trackway E | E02-L | 27.00 | 11.00 | 40.70 | 246.00 | 297 |

| E03-R | 27.00 | 10.50 | 38.90 | 183.00 | 283.5 | |

| Dir F | F02-R | 25.90 | 10.50 | 40.50 | 189.50 | 271.95 |

| BODY MASS (kg) Estimates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Footprint | Right Footprint length (cm) | Left Footprint length (cm) | Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length and Width (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Area2 (cm2) |

| BM = −71.142 + 5.259 rFl | BM = −70.385 + 5.217 rFl | BM = 23.61 + 0.11 Fa | BM = 4.71 + 1.82 rFl | BM = −97.4 + 2.44 rFl + 10.7 rFw | BM = −80.4 + 15.3 rFw | BM = −21.9 rFl + 0.546 rFl2 + 265.4 | BM = −25.8 rFw + 1.84 rFw2 + 133.3 | BM = −0.250 Fa + 0.00099 Fa2 + 59.1 | BM = −0.250 Fa + 0.00099 Fa2 + 59.1 | |

| [82] | [31] | [83] | [60] | |||||||

| A01 (left) | 63.6919 | 50.01 | 51.484 | 84.078 | 89.43 | 63.19754 | 73.6264 | 56.124 | 68.347683 | |

| A02 (right) | 64.0143 | 48.8 | 51.484 | 85.148 | 90.96 | 63.19754 | 75.1496 | 53.76659 | 69.163346 | |

| A03 (left) | 54.823 | 45.28 | 48.39 | 81 | 90.96 | 54.296 | 75.1496 | 48.27091 | 63.430905 | |

| A04 (right) | 60.8589 | 48.03 | 50.392 | 83.684 | 90.96 | 59.69546 | 75.1496 | 52.39116 | 67.058169 | |

| A05 (left) | 50.1277 | 43.96 | 46.752 | 71.314 | 80.25 | 50.86106 | 65.26 | 46.73275 | 56.704697 | |

| A06 (right) | 55.5999 | 43.3 | 48.572 | 70.544 | 75.66 | 54.73226 | 61.5736 | 46.07059 | 57.468197 | |

| A07 (left) | 49.606 | 42.64 | 46.57 | 68.93 | 77.19 | 50.534 | 62.7656 | 45.47971 | 55.435393 | |

| A08 (right) | 57.7035 | 47.59 | 49.3 | 84.36 | 94.02 | 56.5865 | 78.3064 | 51.64876 | 66.503405 | |

| A09 (right) | 49.815 | 43.3 | 46.57 | 73.21 | 83.31 | 50.534 | 67.9016 | 46.07059 | 57.534557 | |

| A10 (left) | 38.6503 | 38.46 | 42.748 | 49.896 | 57.3 | 46.18826 | 50.14 | 43.39275 | 47.102793 | |

| A11 (right) | 51.3927 | 43.08 | 47.116 | 69.662 | 77.19 | 51.54794 | 62.7656 | 45.86571 | 56.121748 | |

| A12 (left) | 46.9975 | 43.85 | 45.66 | 68.78 | 78.72 | 49.0625 | 63.9944 | 46.61744 | 54.80844 | |

| A13 (right) | 51.9186 | 43.63 | 47.298 | 77.396 | 87.9 | 51.90776 | 72.14 | 46.39276 | 60.3422124 | |

| A14 (left) | 45.9541 | 44.51 | 45.296 | 78.992 | 94.02 | 48.55034 | 78.3064 | 47.339 | 59.526530 | |

| A16 (left) | 52.2145 | 45.61 | 47.48 | 85.13 | 98.61 | 52.2785 | 83.3176 | 48.7 | 65.204027 | |

| A17 (right) | 59.2812 | 46.82 | 49.846 | 82.952 | 90.96 | 58.09184 | 75.1496 | 50.42579 | 66.039111 | |

| A18 (left) | 57.4315 | 47.48 | 49.3 | 85.43 | 95.55 | 56.5865 | 79.94 | 51.46811 | 67.251731 | |

| A21 (right) | 59.2812 | 48.58 | 49.846 | 87.232 | 97.08 | 58.09184 | 81.6104 | 53.36371 | 69.112184 | |

| A22 (left) | 57.4315 | 45.5 | 49.3 | 76.87 | 83.31 | 56.5865 | 67.9016 | 48.55499 | 61.59789628 | |

| A23 (right) | 57.7035 | 46.05 | 49.3 | 77.94 | 84.84 | 56.5865 | 69.2776 | 49.29984 | 62.263028 | |

| A24 (left) | 58.4749 | 50.45 | 49.664 | 89.128 | 100.14 | 57.57914 | 85.0616 | 57.04064 | 70.334442 | |

| A25 (right) | 57.7035 | 46.93 | 49.3 | 87.57 | 98.61 | 56.5865 | 83.3176 | 50.59456 | 68.784040 | |

| A26 (left) | 57.4315 | 46.93 | 49.3 | 79.01 | 86.37 | 56.5865 | 70.6904 | 50.59456 | 62.940045 | |

| B00 (left) | 44.389 | 45.28 | 44.75 | 66.49 | 77.19 | 47.864 | 62.7656 | 48.27091 | 53.284084 | |

| B01 (right) | 44.556 | 44.95 | 44.75 | 73.98 | 87.9 | 47.864 | 72.14 | 47.85964 | 56.57836 | |

| B02 (left) | 49.606 | 46.27 | 46.57 | 71.07 | 80.25 | 50.534 | 65.26 | 49.61164 | 56.464027 | |

| B03 (right) | 49.815 | 43.3 | 46.57 | 65.72 | 72.6 | 50.534 | 59.3 | 46.07059 | 53.971 | |

| B04 (left) | 39.172 | 40.33 | 42.93 | 60.84 | 72.6 | 46.286 | 59.3 | 43.97296 | 50.259 | |

| B05 (right) | 50.8668 | 45.5 | 46.934 | 71.558 | 80.25 | 51.19904 | 65.26 | 48.55499 | 56.947550 | |

| B06 (left) | 46.9975 | 42.64 | 45.66 | 64.5 | 72.6 | 49.0625 | 59.3 | 45.47971 | 52.96875 | |

| B07 (right) | 49.815 | 45.17 | 46.57 | 71.07 | 80.25 | 50.534 | 65.26 | 48.13184 | 56.4640275 | |

| B08 (left) | 44.389 | 45.72 | 44.75 | 73.98 | 87.9 | 47.864 | 72.14 | 48.84699 | 56.57836 | |

| B08a (right) | 47.1855 | 43.52 | 45.66 | 75.2 | 87.9 | 49.0625 | 72.14 | 46.28339 | 57.868687 | |

| B10 (right) | 39.297 | 41.98 | 42.93 | 66.19 | 80.25 | 46.286 | 65.26 | 44.96011 | 52.109047 | |

| B11 (left) | 49.606 | 46.16 | 46.57 | 65.72 | 72.6 | 50.534 | 59.3 | 49.45475 | 53.971 | |

| B12 (right) | 50.8668 | 42.64 | 46.934 | 66.208 | 72.6 | 51.19904 | 59.3 | 45.47971 | 54.38576 | |

| B13 (left) | 50.1277 | 45.28 | 46.752 | 71.314 | 80.25 | 50.86106 | 65.26 | 48.27091 | 56.70469748 | |

| B15 (right) | 50.3409 | 41.43 | 46.752 | 72.384 | 81.78 | 50.86106 | 66.5624 | 44.58156 | 57.241855 | |

| B16 (left) | 49.606 | 43.3 | 46.57 | 70 | 78.72 | 50.534 | 63.9944 | 46.07059 | 55.944473 | |

| B18 (left) | 50.1277 | 45.06 | 46.752 | 70.244 | 78.72 | 50.86106 | 63.9944 | 47.99475 | 56.178105 | |

| C05 (right) | 47.7114 | 43.96 | 45.842 | 69.024 | 78.72 | 49.33496 | 63.9944 | 46.73275 | 55.031363 | |

| C07 (left) | 47.5192 | 42.2 | 45.842 | 69.024 | 78.72 | 49.33496 | 63.9944 | 45.12539 | 55.031363 | |

| C08 (right) | 45.0819 | 42.53 | 44.932 | 68.874 | 80.25 | 48.08186 | 65.26 | 45.38816 | 54.396230 | |

| C09 (left) | 41.2588 | 44.95 | 43.658 | 83.216 | 103.2 | 46.78616 | 88.66 | 47.85964 | 60.186777 | |

| C10 (right) | 58.2294 | 44.95 | 49.482 | 69.624 | 72.6 | 57.07736 | 59.3 | 47.85964 | 57.51084 | |

| C12 (right) | 56.1258 | 42.97 | 48.754 | 63.298 | 64.95 | 55.17944 | 54.26 | 45.76624 | 53.950469 | |

| D01 (right) | 30.3567 | 38.79 | 39.836 | 72.742 | 95.55 | 46.10954 | 79.94 | 43.45356 | 52.381684 | |

| E02 (left) | 70.474 | 50.67 | 53.85 | 86.18 | 87.9 | 72.134 | 72.14 | 57.51084 | 72.17691 | |

| E03 (right) | 70.851 | 43.74 | 53.85 | 80.83 | 80.25 | 72.134 | 65.26 | 46.50411 | 67.793527 | |

| F02 (right) | 65.0661 | 44.455 | 51.848 | 78.146 | 80.25 | 64.45226 | 65.26 | 47.276147 | 64.329734 | |

| STATURE Estimate * (cm) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Footprint | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Right Footprint Length (cm) | Left Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Area1 ** (cm2) | Footprint Area2 *** (cm2) |

| rFl 15.25% Ratio | ST = 6.58 rFl | ST = 17.369 + 5.879 rFl | ST = 17.592 + 5.861 rFl | ST = 47.0 + 5.00 rFl | ST = 4.1 rFl + 66.9 | ST = 4.9 rFw + 121.4 | ST = 0.2 Fa + 137.9 | ST = 0.2 Fa + 137.9 | |

| [85] | [84] | [82] | [83] | [52] | |||||

| A01 (left) | 168.52 | 169.106 | 168.22 | 175.5 | 172.27 | 175.79 | 185.9 | 194.954 | |

| A02 (right) | 168.52 | 169.106 | 168.459 | 175.5 | 172.27 | 176.28 | 183.7 | 195.468 | |

| A03 (left) | 157.38 | 157.92 | 158.256 | 167 | 165.3 | 176.28 | 177.3 | 191.66 | |

| A04 (right) | 164.59 | 165.158 | 164.932 | 172.5 | 169.81 | 176.28 | 182.3 | 194.124 | |

| A05 (left) | 151.47 | 151.998 | 152.981 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 172.85 | 174.9 | 186.41 | |

| A06 (right) | 158.03 | 158.578 | 159.053 | 167.5 | 165.71 | 171.38 | 173.7 | 187.064 | |

| A07 (left) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.395 | 161.2 | 171.87 | 172.5 | 185.28 | ||

| A08 (right) | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.404 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 177.26 | 181.5 | 193.76 | |

| A09 (right) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.586 | 162 | 161.2 | 173.83 | 173.7 | 187.12 | |

| A10 (left) | 137.05 | 137.522 | 140.087 | 151.5 | 152.59 | 165.5 | 164.9 | 175.52 | |

| A11 (right) | 152.79 | 153.314 | 154.35 | 163.5 | 162.43 | 171.87 | 173.3 | 185.898 | |

| A12 (left) | 147.54 | 148.05 | 149.464 | 159.5 | 159.15 | 172.36 | 174.7 | 184.7 | |

| A13 (right) | 153.44 | 153.972 | 154.938 | 164 | 162.84 | 175.3 | 174.3 | 189.38 | |

| A14 (left) | 146.23 | 146.734 | 148.292 | 158.5 | 158.33 | 177.26 | 175.9 | 188.744 | |

| A16 (left) | 154.1 | 154.63 | 155.325 | 164.5 | 163.25 | 178.73 | 177.9 | 192.89 | |

| A17 (right) | 162.62 | 163.184 | 163.168 | 171 | 168.58 | 176.28 | 180.1 | 193.452 | |

| A18 (left) | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.186 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 177.75 | 181.3 | 194.25 | |

| A21 (right) | 162.62 | 163.184 | 163.168 | 171 | 168.58 | 178.24 | 183.3 | 195.436 | |

| A22 (left) | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.186 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 173.83 | 177.7 | 190.33 | |

| A23 (right) | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.404 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 174.32 | 178.7 | 190.82 | |

| A24 (left) | 161.97 | 162.526 | 162.359 | 170.5 | 168.17 | 179.22 | 186.7 | 196.192 | |

| A25 (right) | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.404 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 178.73 | 180.3 | 195.23 | |

| A26 (left) | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.186 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 174.81 | 180.3 | 191.31 | |

| B00 (left) | 144.26 | 144.76 | 146.534 | 157 | 157.1 | 171.87 | 177.3 | 183.22 | |

| B01 (right) | 144.26 | 144.76 | 146.707 | 157 | 157.1 | 175.3 | 176.7 | 186.3 | |

| B02 (left) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.395 | 162 | 161.2 | 172.85 | 179.1 | 186.2 | |

| B03 (right) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.586 | 162 | 161.2 | 170.4 | 173.7 | 183.9 | |

| B04 (left) | 137.7 | 138.18 | 140.673 | 152 | 153 | 170.4 | 168.3 | 179.9 | |

| B05 (right) | 152.13 | 152.656 | 153.762 | 163 | 162.02 | 172.85 | 177.7 | 186.62 | |

| B06 (left) | 147.54 | 148.05 | 149.464 | 159.5 | 159.15 | 170.4 | 172.5 | 182.9 | |

| B07 (right) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.586 | 162 | 161.2 | 172.85 | 177.1 | 186.2 | |

| B08 (left) | 144.26 | 144.76 | 146.534 | 157 | 157.1 | 175.3 | 178.1 | 186.3 | |

| B08a (right) | 147.54 | 148.05 | 149.646 | 159.5 | 159.15 | 175.3 | 174.1 | 187.4 | |

| B10 (right) | 137.7 | 138.18 | 140.828 | 152 | 153 | 172.85 | 171.3 | 182 | |

| B11 (left) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.395 | 162 | 161.2 | 170.4 | 178.9 | 183.9 | |

| B12 (right) | 152.13 | 152.656 | 153.762 | 163 | 162.02 | 170.4 | 172.5 | 184.3 | |

| B13 (left) | 151.47 | 151.998 | 152.981 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 172.85 | 177.3 | 186.41 | |

| B15 (right) | 151.47 | 151.998 | 153.173 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 173.34 | 170.3 | 186.872 | |

| B16 (left) | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.395 | 162 | 161.2 | 172.36 | 173.7 | 185.74 | |

| B18 (left) | 151.47 | 151.998 | 152.981 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 172.36 | 176.9 | 185.948 | |

| C05 (right) | 148.2 | 148.708 | 150.234 | 160 | 159.56 | 172.36 | 174.9 | 184.908 | |

| C07 (left) | 148.2 | 148.708 | 150.05 | 160 | 159.56 | 172.36 | 171.7 | 184.908 | |

| C08 (right) | 144.92 | 145.418 | 147.295 | 157.5 | 157.51 | 172.85 | 172.3 | 184.31 | |

| C09 (left) | 140.33 | 140.812 | 143.017 | 154 | 154.64 | 180.2 | 176.7 | 189.26 | |

| C10 (right) | 161.31 | 161.868 | 161.992 | 170 | 167.76 | 170.4 | 176.7 | 187.1 | |

| C12 (right) | 158.69 | 159.236 | 159.641 | 168 | 166.12 | 167.95 | 173.1 | 183.88 | |

| D01 (right) | 126.56 | 126.994 | 130.833 | 143.5 | 146.03 | 177.75 | 165.5 | 182.29 | |

| E02 (left) | 177.05 | 177.66 | 175.839 | 182 | 177.6 | 175.3 | 187.1 | 197.3 | |

| E03 (right) | 177.05 | 177.66 | 176.102 | 182 | 177.6 | 172.85 | 174.5 | 194.6 | |

| F02 (right) | 169.84 | 170.422 | 169.635 | 176.5 | 173.09 | 172.85 | 175.8 | 192.29 | |

| SAMPLE A—SUMMARY STATISTICS—BODY MASS (kg) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Length (cm) | BM Average Value Returned from Right plus Left Footprint Lengths (cm) | Footprint Length and Width (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Area2 (cm2) | |

| [31] | [82] | [83] | [60] | ||||||

| All footprints | |||||||||

| N | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Min | 38.46 | 39.84 | 30.36 | 49.9 | 57.3 | 46.11 | 43.39 | 50.14 | 47.1 |

| Max | 50.67 | 53.85 | 70.85 | 89.13 | 103.2 | 72.13 | 57.51 | 88.66 | 72.18 |

| Sum | 2238.54 | 2367.25 | 2597.58 | 3715.66 | 4170.09 | 2662.41 | 2409.54 | 3433.1 | 2963.75 |

| Mean | 44.7708 | 47.345 | 51.9516 | 74.3132 | 83.4018 | 53.2482 | 48.1908 | 68.662 | 59.275 |

| Std. error | 0.369671 | 0.3926168 | 1.133106 | 1.161128 | 1.327655 | 0.8522861 | 0.4617091 | 1.180532 | 0.8476943 |

| Variance | 6.832832 | 7.707397 | 64.19643 | 67.41089 | 88.13345 | 36.31958 | 10.65876 | 69.68278 | 35.92928 |

| Stand. dev | 2.613969 | 2.77622 | 8.012268 | 8.210413 | 9.387942 | 6.026573 | 3.264776 | 8.347621 | 5.994104 |

| Median | 44.95 | 46.75 | 50.235 | 72.56 | 80.25 | 50.86 | 47.86 | 65.26 | 57.095 |

| 25th percentile | 43.245 | 45.66 | 47.1425 | 68.9975 | 78.3375 | 49.06 | 46.02 | 63.685 | 54.975 |

| 75th percentile | 46.1875 | 49.3 | 57.7 | 81.4875 | 90.96 | 56.59 | 49.49 | 75.15 | 64.5475 |

| Skewness | 0.08393137 | 0.07289 | 0.07327954 | −0.19457 | −0.08107937 | 1.435316 | 1.179791 | 0.3971122 | 0.4807153 |

| Kurtosis | 0.4625451 | 0.5640185 | 0.5383206 | 0.1350823 | 0.171182 | 2.244626 | 1.297863 | −0.212417 | −0.715546 |

| Geom. mean | 44.6959 | 47.26505 | 51.32802 | 73.85462 | 82.87176 | 52.94127 | 48.08719 | 68.1724 | 58.98474 |

| Coeff. var | 5.838557 | 5.863808 | 15.42256 | 11.04839 | 11.25628 | 11.31789 | 6.774687 | 12.15756 | 10.11236 |

| Trackway A | |||||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Min | 38.46 | 42.75 | 38.65 | 49.9 | 57.3 | 46.19 | 43.39 | 50.14 | 47.1 |

| Max | 50.45 | 51.48 | 64.01 | 89.13 | 100.14 | 63.2 | 57.04 | 85.06 | 70.33 |

| Sum | 1050.79 | 1110.97 | 1258.09 | 1798.25 | 2003.34 | 1259.89 | 1136.19 | 1658.51 | 1433.05 |

| Mean | 45.68652 | 48.30304 | 54.69957 | 78.18478 | 87.10174 | 54.77783 | 49.39957 | 72.10913 | 62.30652 |

| Std. error | 0.5764689 | 0.4345583 | 1.258028 | 1.86164 | 2.053768 | 0.9297152 | 0.7402498 | 1.785604 | 1.247315 |

| Variance | 7.643278 | 4.34334 | 36.4006 | 79.71118 | 97.01319 | 19.88052 | 12.6033 | 73.33279 | 35.78331 |

| Stand. dev | 2.764648 | 2.084068 | 6.033291 | 8.928112 | 9.849527 | 4.458757 | 3.550113 | 8.563457 | 5.981915 |

| Median | 45.61 | 49.3 | 57.43 | 79.01 | 89.43 | 56.59 | 48.7 | 73.63 | 62.94 |

| 25th percentile | 43.63 | 46.75 | 50.13 | 71.31 | 80.25 | 50.86 | 46.39 | 65.26 | 57.47 |

| 75th percentile | 47.59 | 49.66 | 58.48 | 85.13 | 94.02 | 57.58 | 51.65 | 78.31 | 67.25 |

| Skewness | −0.466721 | −0.797872 | −0.7980345 | −1.476095 | −1.207619 | 0.0540664 | 0.5259357 | −0.595613 | −0.674611 |

| Kurtosis | 0.6873681 | 0.8236614 | 0.8081548 | 3.191563 | 2.365487 | −0.414261 | −0.319831 | 0.3495946 | 0.0753518 |

| Geom. mean | 45.60471 | 48.25902 | 54.35769 | 77.62703 | 86.5068 | 54.60367 | 49.27979 | 71.59165 | 62.01771 |

| Coeff. var | 6.051343 | 4.314569 | 11.02987 | 11.41924 | 11.30807 | 8.139712 | 7.186527 | 11.87569 | 9.600784 |

| Trackway B | |||||||||

| N | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Min | 40.33 | 42.93 | 39.17 | 60.84 | 72.6 | 46.29 | 43.97 | 59.3 | 50.26 |

| Max | 46.27 | 46.93 | 50.87 | 75.2 | 87.9 | 51.2 | 49.61 | 72.14 | 57.87 |

| Sum | 748.53 | 778.39 | 806.81 | 1176.46 | 1344.36 | 841.91 | 799.87 | 1096.53 | 937.91 |

| Mean | 44.03118 | 45.78765 | 47.45941 | 69.20353 | 79.08 | 49.52412 | 47.05118 | 64.50176 | 55.17118 |

| Std. error | 0.431933 | 0.3210948 | 0.9268644 | 0.9627068 | 1.302282 | 0.4098404 | 0.4325258 | 1.086267 | 0.5122534 |

| Variance | 3.171624 | 1.752732 | 14.60432 | 15.75567 | 28.83094 | 2.855476 | 3.180336 | 20.05959 | 4.460861 |

| Stand. dev | 1.780905 | 1.323908 | 3.82156 | 3.969342 | 5.369445 | 1.689815 | 1.78335 | 4.478793 | 2.112075 |

| Median | 44.95 | 46.57 | 49.61 | 70.24 | 80.25 | 50.53 | 47.86 | 65.26 | 56.18 |

| 25th percentile | 42.64 | 44.75 | 44.475 | 65.955 | 72.6 | 47.86 | 45.48 | 59.3 | 53.625 |

| 75th percentile | 45.39 | 46.75 | 50.13 | 71.97 | 81.015 | 50.86 | 48.41 | 65.91 | 56.64 |

| Skewness | −0.5911545 | −1.281413 | −1.266189 | −0.3908884 | 0.3288698 | −0.8811604 | −0.2199729 | 0.5034702 | −0.8979981 |

| Kurtosis | −0.7047984 | 0.6325628 | 0.5998547 | −0.5733045 | −0.69387 | −0.6151692 | −1.321385 | −0.5109379 | 0.05907432 |

| Geom. mean | 43.99676 | 45.76922 | 47.3046 | 69.09467 | 78.91009 | 49.49648 | 47.01919 | 64.35786 | 55.1323 |

| Coeff. var | 4.044646 | 2.891408 | 8.052269 | 5.735751 | 6.78989 | 3.412106 | 3.790234 | 6.943676 | 3.828222 |

| Trackway C | |||||||||

| N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Min | 42.2 | 43.66 | 41.26 | 63.3 | 64.95 | 46.79 | 45.13 | 54.26 | 53.95 |

| Max | 44.95 | 49.48 | 58.23 | 83.22 | 103.2 | 57.08 | 47.86 | 88.66 | 60.19 |

| Sum | 261.56 | 278.5 | 295.93 | 423.05 | 478.44 | 305.79 | 278.74 | 395.46 | 336.11 |

| Mean | 43.59333 | 46.41667 | 49.32167 | 70.50833 | 79.74 | 50.965 | 46.45667 | 65.91 | 56.01833 |

| Std. error | 0.4924812 | 0.9183851 | 2.674182 | 2.716923 | 5.23589 | 1.695678 | 0.4960757 | 4.846897 | 0.9743114 |

| Variance | 1.455227 | 5.060587 | 42.9075 | 44.29002 | 164.4872 | 17.25195 | 1.476547 | 140.9545 | 5.695697 |

| Stand. dev | 1.206328 | 2.249575 | 6.550381 | 6.655075 | 12.82526 | 4.153547 | 1.215132 | 11.87243 | 2.386566 |

| Median | 43.465 | 45.84 | 47.615 | 69.02 | 78.72 | 49.33 | 46.25 | 63.99 | 55.03 |

| 25th percentile | 42.4475 | 44.6125 | 44.125 | 67.4775 | 70.6875 | 47.7575 | 45.325 | 58.04 | 54.2875 |

| 75th percentile | 44.95 | 48.9325 | 56.655 | 73.02 | 85.9875 | 55.655 | 47.86 | 71.11 | 58.18 |

| Skewness | 0.1527514 | 0.4435695 | 0.4400401 | 1.697483 | 1.324025 | 0.8290244 | 0.2801229 | 1.772987 | 1.344063 |

| Kurtosis | −2.286171 | −1.314769 | −1.302941 | 4.037172 | 2.892181 | −1.307951 | −2.276134 | 3.904915 | 0.9758673 |

| Geom. mean | 43.57945 | 46.37162 | 48.96549 | 70.2626 | 78.94085 | 50.82775 | 46.44346 | 65.11618 | 55.97699 |

| Coeff. var | 2.76723 | 4.846481 | 13.28094 | 9.438706 | 16.08384 | 8.149802 | 2.615625 | 18.01309 | 4.26033 |

| Trackway E | |||||||||

| N | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Min | 43.74 | 53.85 | 70.47 | 80.83 | 80.25 | 72.13 | 46.5 | 65.26 | 67.79 |

| Max | 50.67 | 53.85 | 70.85 | 86.18 | 87.9 | 72.13 | 57.51 | 72.14 | 72.18 |

| Sum | 94.41 | 107.7 | 141.32 | 167.01 | 168.15 | 144.26 | 104.01 | 137.4 | 139.97 |

| Mean | 47.205 | 53.85 | 70.66 | 83.505 | 84.075 | 72.13 | 52.005 | 68.7 | 69.985 |

| Std. error | 3.465 | 0 | 0.19 | 2.675 | 3.825 | 0 | 5.505 | 3.44 | 2.195 |

| Variance | 24.01245 | 0 | 0.0722 | 14.31125 | 29.26125 | 0 | 60.61005 | 23.6672 | 9.63605 |

| Stand. dev | 4.90025 | 0 | 0.2687006 | 3.783021 | 5.409367 | 0 | 7.785246 | 4.864895 | 3.104199 |

| Median | 47.205 | 53.85 | 70.66 | 83.505 | 84.075 | 72.13 | 52.005 | 68.7 | 69.985 |

| 25th percentile | 43.74 | 53.85 | 70.47 | 80.83 | 80.25 | 72.13 | 46.5 | 65.26 | 67.79 |

| 75th percentile | 50.67 | 53.85 | 70.85 | 86.18 | 87.9 | 72.13 | 57.51 | 72.14 | 72.18 |

| Skewness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kurtosis | −2.75 | 0 | −2.75 | −2.75 | −2.75 | 0 | −2.75 | −2.75 | −2.75 |

| Geom. mean | 47.07766 | 53.85 | 70.65974 | 83.46214 | 83.98795 | 72.13 | 51.71281 | 68.61382 | 69.95057 |

| Coeff. var | 0.38079 | 0 | 0.3802725 | 4.530293 | 6.433978 | 0 | 14.97019 | 7.08136 | 4.43552 |

| SAMPLE B—SUMMARY STATISTICS—BODY MASS (kg) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Length (cm) | BM Average Value Returned from Right plus Left Footprint Lengths (cm) | Footprint Length and Width (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Area2 (cm2) | |

| [31] | [82] | [83] | [60] | ||||||

| All footprints | |||||||||

| N | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Min | 41.43 | 45.84 | 47.71 | 65.72 | 72.6 | 49.33 | 59.3 | 44.58 | 53.97 |

| Max | 50.45 | 53.85 | 70.85 | 89.13 | 100.14 | 72.13 | 85.06 | 57.04 | 70.33 |

| Sum | 956.33 | 1017.09 | 1157.26 | 1602.7 | 1767.87 | 1156.31 | 1453.99 | 1028.08 | 1283.76 |

| Mean | 45.53952 | 48.43286 | 55.10762 | 76.31905 | 84.18429 | 55.06238 | 69.23762 | 48.95619 | 61.13143 |

| Std. error | 0.4632728 | 0.4490027 | 1.299169 | 1.678367 | 1.878528 | 1.211011 | 1.761088 | 0.6367714 | 1.26044 |

| Variance | 4.507055 | 4.233671 | 35.44462 | 59.1552 | 74.10621 | 30.79751 | 65.13005 | 8.515035 | 33.36287 |

| Stand. dev | 2.122983 | 2.057589 | 5.953538 | 7.691242 | 8.608496 | 5.54955 | 8.070319 | 2.918053 | 5.77606 |

| Median | 45.5 | 49.3 | 57.43 | 76.87 | 80.25 | 56.59 | 65.26 | 48.55 | 61.6 |

| 25th percentile | 43.85 | 46.66 | 49.975 | 70.12 | 78.72 | 50.695 | 63.99 | 46.615 | 56.06 |

| 75th percentile | 46.93 | 49.48 | 58.09 | 83.655 | 92.49 | 57.085 | 76.73 | 50.59 | 66.875 |

| Skewness | 0.2474294 | 0.9258756 | 0.9489392 | 0.2181195 | 0.5611684 | 1.614559 | 0.7481781 | 1.011529 | 0.206689 |

| Kurtosis | 0.260093 | 0.7828594 | 0.8460032 | −1.303617 | 0.7797774 | 3.399786 | 0.6522837 | 1.596323 | −1.629715 |

| Geom. mean | 45.49261 | 48.39212 | 54.81613 | 75.95273 | 83.77642 | 54.81705 | 68.80872 | 48.87594 | 60.87358 |

| Coeff. var | 4.661846 | 4.248332 | 10.80348 | 10.07775 | 10.22578 | 10.07866 | 11.65597 | 5.96054 | 9.448594 |

| Trackway A | |||||||||

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Min | 45.5 | 49.3 | 57.43 | 76.87 | 83.31 | 56.59 | 67.9 | 48.55 | 61.6 |

| Max | 50.45 | 49.85 | 59.28 | 89.13 | 100.14 | 58.09 | 85.06 | 57.04 | 70.33 |

| Sum | 426.33 | 445.16 | 522.43 | 750.49 | 830.88 | 513.3 | 691.26 | 462.98 | 594.81 |

| Mean | 47.37 | 49.46222 | 58.04778 | 83.38778 | 92.32 | 57.03333 | 76.80667 | 51.44222 | 66.09 |

| Std. error | 0.4850544 | 0.0831460 | 0.256346 | 1.499347 | 2.078593 | 0.227034 | 2.114199 | 0.8373914 | 1.05805 |

| Variance | 2.1175 | 0.0622194 | 0.5914194 | 20.23237 | 38.88495 | 0.4639 | 40.22855 | 6.311019 | 10.07523 |

| Stand. dev | 1.455163 | 0.2494383 | 0.769038 | 4.498041 | 6.23578 | 0.681102 | 6.342598 | 2.512174 | 3.174149 |

| Median | 46.93 | 49.3 | 57.7 | 84.36 | 94.02 | 56.59 | 78.31 | 50.59 | 66.5 |

| 25th percentile | 46.435 | 49.3 | 57.43 | 78.475 | 85.605 | 56.59 | 69.985 | 49.865 | 62.6 |

| 75th percentile | 48.085 | 49.755 | 58.88 | 87.4 | 97.845 | 57.835 | 82.465 | 52.505 | 68.945 |

| Skewness | 1.138383 | 1.022525 | 1.056239 | −0.342424 | −0.324487 | 1.017394 | −0.241141 | 1.481712 | −0.266815 |

| Kurtosis | 1.854589 | −1.049007 | −0.6454625 | −1.507641 | −1.575313 | −1.068391 | −1.594955 | 2.749306 | −1.456052 |

| Geom. mean | 47.35047 | 49.46166 | 58.04328 | 83.27875 | 92.13025 | 57.02974 | 76.57071 | 51.38956 | 66.02172 |

| Coeff. var | 3.071909 | 0.5043005 | 1.324836 | 5.394125 | 6.754528 | 1.194218 | 8.257874 | 4.883487 | 4.802768 |

| Trackway B | |||||||||

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Min | 41.43 | 46.57 | 49.61 | 65.72 | 72.6 | 50.53 | 59.3 | 44.58 | 53.97 |

| Max | 46.16 | 46.93 | 50.87 | 72.38 | 81.78 | 51.2 | 66.56 | 49.45 | 57.24 |

| Sum | 397.84 | 420.39 | 451.2 | 624.21 | 697.77 | 457.1 | 568.22 | 424.59 | 501.8 |

| Mean | 44.20444 | 46.71 | 50.13333 | 69.35667 | 77.53 | 50.78889 | 63.13556 | 47.17667 | 55.75556 |

| Std. error | 0.5284256 | 0.05 | 0.1612538 | 0.8997886 | 1.269321 | 0.0928924 | 0.9920603 | 0.5513947 | 0.4325927 |

| Variance | 2.513103 | 0.0225 | 0.234025 | 7.286575 | 14.50058 | 0.0776611 | 8.857653 | 2.736325 | 1.684228 |

| Stand. dev | 1.585277 | 0.15 | 0.4837613 | 2.699366 | 3.807962 | 0.2786774 | 2.976181 | 1.654184 | 1.297778 |

| Median | 45.06 | 46.75 | 50.13 | 70.24 | 78.72 | 50.86 | 63.99 | 47.99 | 56.18 |

| 25th percentile | 42.97 | 46.57 | 49.715 | 65.965 | 72.6 | 50.53 | 59.3 | 45.775 | 54.18 |

| 75th percentile | 45.39 | 46.84 | 50.605 | 71.435 | 80.25 | 51.03 | 65.26 | 48.41 | 56.825 |

| Skewness | −0.574503 | 0.5005714 | 0.6532765 | −0.617553 | −0.637303 | 0.5245505 | −0.604219 | −0.285933 | −0.564837 |

| Kurtosis | −0.891577 | −1.275429 | −0.8538516 | −1.650747 | −1.68395 | −1.232761 | −1.673007 | −1.362187 | −1.571133 |

| Geom. mean | 44.17889 | 46.70979 | 50.13127 | 69.30936 | 77.44543 | 50.78821 | 63.07222 | 47.15074 | 55.74204 |

| Coeff. var | 3.586239 | 0.3211304 | 0.9649494 | 3.892006 | 4.911598 | 0.5486976 | 4.713954 | 3.506361 | 2.327621 |

| SAMPLE A—SUMMARY STATISTICS—STATURE (cm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Right and Left Footprint Lengths (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Area2 (cm2) | |

| [85] | [84] | [82] | [83] | [52] | ||||

| All footprints | ||||||||

| N | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Min | 126.56 | 126.994 | 130.833 | 143.5 | 146.03 | 165.5 | 164.9 | 175.52 |

| Max | 177.05 | 177.66 | 176.102 | 182 | 177.6 | 180.2 | 187.1 | 197.3 |

| Sum | 7680.59 | 7707.154 | 7749.843 | 8206.5 | 8147.33 | 8692.97 | 8818.7 | 9404.948 |

| Mean | 153.61180 | 154.14310 | 154.99690 | 164.13 | 163 | 17 | 176 | 188 |

| Std. error | 1.41478 | 1.41972 | 1.26890 | 1.07881 | 0.8846271 | 0.4251968 | 0.6721322 | 0.6770617 |

| Variance | 100.08 | 100.78010 | 80.50549 | 58.19194 | 39.12826 | 9.39618 | 22.58809 | 22.92063 |

| Stand. dev | 10.00400 | 10.03893 | 8.97249 | 7.62836 | 6.25526 | 3.00660 | 4.75269 | 4.78755 |

| Median | 151.47 | 151.99800 | 153 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 172.85 | 176.7 | 186.746 |

| 25th percentile | 147.54 | 148.05 | 149.60050 | 159.5 | 159.15 | 172.23750 | 173.6 | 184.856 |

| 75th percentile | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 176.28 | 178.95 | 192.44 |

| Skewness | 0.07220779 | 0.0719521 | 0.07425825 | 0.0719521 | 0.0719521 | −0.08107937 | 0.08404799 | 0.0754895 |

| Kurtosis | 0.5653688 | 0.5649397 | 0.5399276 | 0.5649397 | 0.5649397 | 0.171182 | 0.462491 | −0.3409452 |

| Geom. mean | 153.29160 | 153.82170 | 154.74180 | 163.95610 | 162.82890 | 173.83390 | 176.31130 | 188.03930 |

| Coeff. var | 6.51252 | 6.51273 | 5.78882 | 4.64776 | 3.83884 | 1.72933 | 2.69467 | 2.54523 |

| Trackway A | ||||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Min | 137.05 | 137.522 | 140.087 | 151.5 | 152.59 | 165.5 | 164.9 | 175.52 |

| Max | 168.52 | 169.106 | 168 | 175.5 | 172.27 | 179.22 | 186.7 | 196.192 |

| Sum | 3612.41 | 3624.922 | 3635.803 | 3835.5 | 3797.39 | 4026.02 | 4094.9 | 4380 |

| Mean | 157.06130 | 157.60530 | 158.07840 | 166.7609 | 165.10390 | 175.04430 | 178.03910 | 190.43440 |

| Std. error | 1.56620 | 1.57192 | 1.40883 | 1.19447 | 0.979462 | 0.6577428 | 1.04813 | 1.02219 |

| Variance | 5.64188 | 5.68312 | 4.56505 | 3.42180 | 2.20650 | 9.95039 | 2.52670 | 2.40319 |

| Stand. dev | 7.51124 | 7.53865 | 6.75652 | 5.72846 | 4.69734 | 3.15442 | 5.02663 | 4.90224 |

| Median | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 175.79 | 177.9 | 191.31 |

| 25th percentile | 151.47 | 151.99800 | 152.98100 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 172.85 | 174.3 | 187.064 |

| 75th percentile | 161.97 | 162.52600 | 162 | 170.5 | 168.17 | 177.26 | 181.5 | 194.25 |

| Skewness | −0.7969578 | −0.7968577 | −0.8003321 | −0.7968577 | −0.7968577 | −1.207619 | −0.4667217 | −1.288343 |

| Kurtosis | 0.8241726 | 0.8235094 | 0.8185646 | 0.8235094 | 0.8235094 | 2.365487 | 0.6873681 | 2.352714 |

| Geom. mean | 156.88490 | 157.42830 | 157.93700 | 166.66500 | 165.03900 | 175.01680 | 177.97060 | 190.37280 |

| Coeff. var | 4.78236 | 4.78325 | 4.27416 | 3.43513 | 2.84508 | 1.80207 | 2.82333 | 2.57424 |

| Trackway B | ||||||||

| N | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Min | 137.7 | 138.18 | 140.673 | 152 | 153 | 170.4 | 168.3 | 179.9 |

| Max | 152.13 | 152.656 | 154 | 163 | 162.02 | 175.3 | 179.1 | 187.4 |

| Sum | 2516.03 | 2524.746 | 2549.402 | 2717.5 | 2710.47 | 2932.08 | 2975.5 | 3144.11 |

| Mean | 148.00180 | 148.51450 | 149.96480 | 159.8529 | 159.43940 | 172.47530 | 175.02940 | 184.94760 |

| Std. error | 1.15772 | 1.16150 | 1.03808 | 0.882598 | 0.7237304 | 0.4170706 | 0.7853327 | 0.4964395 |

| Variance | 22.78528 | 22.93436 | 18.31932 | 13.24265 | 8.90436 | 2.95711 | 10.48471 | 4.18969 |

| Stand. dev | 4.77339 | 4.78898 | 4.28011 | 3.63905 | 2.98402 | 1.71963 | 3.23801 | 2.04687 |

| Median | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152 | 162 | 161.2 | 172.85 | 176.7 | 185.948 |

| 25th percentile | 144.26 | 144.76 | 146.62050 | 157 | 157.1 | 170.4 | 172.5 | 183.56 |

| 75th percentile | 151.47 | 151.99800 | 152.981 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 173 | 177.5 | 186.355 |

| Skewness | −1.280483 | −1.280016 | −1.268375 | −1.280016 | −1.28002 | 0.3288698 | −0.5911545 | −1.07773 |

| Kurtosis | 0.6307901 | 0.6295855 | 0.6032519 | 0.6295855 | 0.6295855 | −0.69387 | −0.7047984 | 0.64397 |

| Geom. mean | 147.92750 | 148.43990 | 149.90610 | 159.81330 | 159.4127 | 172.4672 | 175,001 | 184.9369 |

| Coeff. var | 3.22523 | 3.22459 | 2.85407 | 2.27650 | 1.87157 | 0.9970275 | 1.84998 | 1.10673 |

| Trackway C | ||||||||

| N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Min | 140.33 | 140.812 | 143.017 | 154 | 154.64 | 167.95 | 171.7 | 183.88 |

| Max | 161.31 | 161.868 | 162 | 170 | 167.76 | 180.2 | 176.7 | 189.26 |

| Sum | 901.65 | 904.75 | 912229 | 969.5 | 965.15 | 1036.12 | 1045.4 | 1114.3660 |

| Mean | 150.27500 | 150.79170 | 152.03820 | 161.5833 | 160.8583 | 172.6867 | 174.2333 | 185.7277 |

| Std. error | 3.31046 | 3.32238 | 2.98869 | 2.52460 | 2.070173 | 1.676854 | 0.8954204 | 0.8392067 |

| Variance | 65.75475 | 66.22906 | 53.59375 | 38.24167 | 25.713700 | 16.871030 | 4.810667 | 4.225607 |

| Stand. dev | 8.10893 | 8.13812 | 7.32078 | 6.18399 | 5.070867 | 4.107436 | 2.193323 | 2.055628 |

| Median | 148.2 | 148.70800 | 150.14200 | 160.00000 | 159.56 | 172.36 | 174 | 184.9080 |

| 25th percentile | 143.77250 | 144.26650 | 146.22550 | 156.625 | 156.7925 | 169.7875 | 172.15 | 184.2025 |

| 75th percentile | 159.34500 | 159.89400 | 160 | 168.5 | 166.53 | 174.6875 | 176.7 | 187.64 |

| Skewness | 0.4414537 | 0.4418692 | 0.4366665 | 0.4418692 | 0.4418692 | 1,324,025 | 0.1527514 | 1.257172 |

| Kurtosis | −1.314707 | −1.314453 | −1.299535 | −1.314453 | −1.314453 | 2.892181 | −2.03526 | 0.6430052 |

| Geom. mean | 150.09440 | 150.61030 | 151.89250 | 161.48540 | 160.792100 | 172.646500 | 174.221800 | 18.571820 |

| Coeff. var | 5.39606 | 5.39693 | 4.81509 | 3.82712 | 3.152381 | 2.378548 | 1.258842 | 1.106797 |

| Trackway E | ||||||||

| N | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Min | 177.05 | 177.66 | 175.839 | 182 | 177.6 | 172.85 | 174.5 | 194.6 |

| Max | 177.05 | 177.66 | 176.102 | 182 | 177.6 | 175.3 | 187.1 | 197.3 |

| Sum | 354.1 | 355.32 | 351941 | 364 | 355.2 | 348.15 | 361.6 | 391.9 |

| Mean | 177.05 | 177.66 | 175.97050 | 182 | 177.6 | 174.075 | 180.8 | 195.95 |

| Std. error | 0 | 0 | 0.1315 | 0 | 0 | 1,225 | 6.3 | 1.35 |

| Variance | 0 | 0 | 0.0345845 | 0 | 0 | 3.00125 | 79.38 | 3.645 |

| Stand. dev | 0 | 0 | 0.1859691 | 0 | 0 | 1.732412 | 8.909545 | 1.909188 |

| Median | 177.05 | 177.66 | 176 | 182 | 177.6 | 174.075 | 180.8 | 195.95 |

| 25th percentile | 177.05 | 177.66 | 175.839 | 182 | 177.6 | 172.85 | 174.5 | 194.6 |

| 75th percentile | 177.05 | 177.66 | 176.102 | 182 | 177.6 | 175.3 | 187.1 | 197.3 |

| Skewness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kurtosis | 0 | 0 | −2.75 | 0 | 0 | −2.75 | −2.75 | −2.75 |

| Geom. mean | 177.05 | 177.66 | 175.97050 | 182 | 177.6 | 174.0707 | 180.6902 | 195.9453 |

| Coeff. var | 0 | 0 | 0.105682 | 0 | 0 | 0.9952099 | 4.927846 | 0.9743242 |

| SAMPLE B—SUMMARY STATISTICS—STATURE (cm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Right and Left Footprint Lengths (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Length (cm) | Footprint Width (cm) | Footprint Area1 (cm2) | Footprint Area2 (cm2) | |

| [85] | [84] | [82] | [83] | [52] | ||||

| All footprints | ||||||||

| N | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Min | 148.2 | 148.708 | 150.234 | 160 | 159.56 | 170.4 | 170.3 | 183.9 |

| Max | 177.05 | 178 | 176 | 182 | 177.6 | 179.22 | 186.7 | 196.192 |

| Sum | 3308.15 | 3319.61 | 3329.057 | 3509.5 | 3473.35 | 3656.31 | 3733.2 | 3982.468 |

| Mean | 157.531 | 158.0767 | 158.5265 | 167.119 | 165.3976 | 174.11 | 177.7714 | 189.6413 |

| Std. error | 1.616977 | 1.62254 | 1.45261 | 1.232933 | 1.011005 | 0.60162 | 0.8423647 | 0.9530677 |

| Variance | 54.90694 | 55.28538 | 44.31161 | 31.92262 | 21.46477 | 7.60088 | 14.90114 | 19.0751 |

| Stand. dev | 7.409922 | 7.435414 | 6.656696 | 5.650011 | 4.633009 | 2.756969 | 3.8602 | 4.367505 |

| Median | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.186 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 172.85 | 177.7 | 190.33 |

| 25th percentile | 151.145 | 152 | 153 | 162 | 161.405 | 172.36 | 174.7 | 186 |

| 75th percentile | 161.31 | 162 | 162 | 170 | 167.76 | 176.77 | 180.3 | 194 |

| Skewness | 0.9277592 | 0.9267267 | 0.9409921 | 0.9267267 | 0.9267267 | 0.5611684 | 0.2476553 | 0.09977926 |

| Kurtosis | 0.7895747 | 0.7872371 | 0.823292 | 0.7872371 | 0.7872371 | −0.7797774 | 0.2594083 | −1.679183 |

| Geom. mean | 157.3689 | 157.914 | 158.3963 | 167.0297 | 165.3367 | 174.0893 | 177.7316 | 189.5935 |

| Coeff. var | 4.703788 | 4.703676 | 4.199106 | 3.38083 | 2.801134 | 1.583464 | 2.17144 | 2.303034 |

| Trackway A | ||||||||

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Min | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.186 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 173.83 | 177.7 | 190.33 |

| Max | 162.62 | 163.184 | 163.168 | 171 | 168.58 | 179.22 | 186.7 | 196.192 |

| Sum | 1451.11 | 1456.154 | 1456.465 | 1529.5 | 1509.43 | 1590.44 | 1629.9 | 1740.78 |

| Mean | 161.2344 | 161.7949 | 161.8294 | 169.9444 | 167.7144 | 176.7156 | 181.1 | 193.42 |

| Std. error | 0.2988409 | 0.2992201 | 0.2801032 | 0.2273709 | 0.1864441 | 0.6656933 | 0.8819171 | 0.7128782 |

| Variance | 0.8037528 | 0.8057941 | 0.7061203 | 0.4652778 | 0.3128528 | 3.988328 | 7.00342 | 4.573758 |

| Stand. dev | 0.8965226 | 0.8976604 | 0.8403096 | 0.6821127 | 0.5593324 | 1.99708 | 2.645751 | 2.138635 |

| Median | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.404 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 177.26 | 180.3 | 193.76 |

| 25th percentile | 160.65 | 161.21 | 161.186 | 169.5 | 167.35 | 174.565 | 179.4 | 191.065 |

| 75th percentile | 162.295 | 162.855 | 162.7635 | 170.75 | 168.375 | 178.485 | 182.4 | 195.333 |

| Skewness | 1.008125 | 1.011219 | 1.060382 | 1.011219 | 1.011219 | −0.3244872 | 1.138383 | −0.3358208 |

| Kurtosis | −1.103583 | −1.091812 | −0.7509011 | −1.091812 | −1.091812 | −1.575313 | 1.854589 | −1.453989 |

| Geom. mean | 161.2322 | 161.7927 | 161.8275 | 169.9432 | 167.7136 | 176.7055 | 181.083 | 193.4095 |

| Coeff. var | 0.5560366 | 0.5548138 | 0.5192563 | 0.401374 | 0.3335028 | 1.13011 | 1.460934 | 1.105695 |

| Trackway B | ||||||||

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Min | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.395 | 162 | 161.2 | 170.4 | 170.3 | 183.9 |

| Max | 152.13 | 152.656 | 153.762 | 163 | 162.02 | 173.34 | 178.9 | 187 |

| Sum | 1361.95 | 136.6666 | 137.6621 | 1461.5 | 1453.67 | 1547.81 | 1578.1 | 1669.89 |

| Mean | 151.3278 | 151.8518 | 152.9579 | 162.3889 | 161.51890 | 171.97890 | 175.34440 | 185.54330 |

| Std. error | 0.1817796 | 0.1827778 | 0.1768089 | 0.1388889 | 0.1138889 | 0.4065145 | 0.9607739 | 0.3953952 |

| Variance | 0.2973944 | 0.3006694 | 0.2813526 | 0.1736111 | 0.1167361 | 1.487286 | 8.307778 | 1.407036 |

| Stand. dev | 0.5453388 | 0.5483333 | 0.5304268 | 0.4166667 | 0.3416667 | 1.219543 | 2.882322 | 1.186185 |

| Median | 151.47 | 151.998 | 152.981 | 162.5 | 161.61 | 172.36 | 176.9 | 185.948 |

| 25th percentile | 150.82 | 151.34 | 152.4905 | 162 | 161.2 | 170.4 | 173.1 | 184.1 |

| 75th percentile | 151.8 | 152.327 | 153.4675 | 162.75 | 162 | 172.85 | 177.5 | 186.515 |

| Skewness | 0.5128099 | 0.5005714 | 0.635682 | 0.5005714 | 0.5005714 | −0.6373039 | −0.5745038 | −0.5966515 |

| Kurtosis | −1.253661 | −1.275429 | −0.9259342 | −1.275429 | −1.275429 | −1.68395 | −0.8915777 | −1.56587 |

| Geom. mean | 15.13269 | 151.8509 | 152.9571 | 162.3884 | 1,615,186 | 172 | 175.3233 | 185.54 |

| Coeff. var | 0.3603693 | 0.3610977 | 0.3467796 | 0.2565857 | 0.2115336 | 0.7091239 | 1.643805 | 0.6393037 |

| SAMPLE A | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Footprints | |||||||||

| DingwallFa1 | DingwallFl | Grivas | DomjanicFw | DomjanicFl + Fw | RuffFa1 | RuffFl | RuffFw | RuffFa2 | |

| DingwallFa1 | 100.00 | 105.75 | 116.04 | 165.99 | 186.29 | 107.64 | 118.94 | 153.36 | 132.40 |

| DingwallFl | 94.56 | 100.00 | 109.73 | 156.96 | 176.16 | 101.79 | 112.47 | 145.02 | 125.20 |

| Grivas | 86.18 | 91.13 | 100.00 | 156.96 | 160.54 | 92.76 | 63.85 | 132.17 | 114.10 |

| DomjanicFw | 60.25 | 63.71 | 69.91 | 100.00 | 112.23 | 64.85 | 71.65 | 92.40 | 79.76 |

| DomjanicFl + Fw | 53.68 | 56.77 | 62.29 | 89.10 | 100.00 | 57.78 | 63.85 | 82.33 | 71.07 |

| RuffFa1 | 92.90 | 98.24 | 107.80 | 154.21 | 173.07 | 100.00 | 110.49 | 142.48 | 123.00 |

| RuffFl | 84.08 | 88.91 | 97.56 | 139.56 | 156.63 | 90.50 | 100.00 | 128.95 | 111.32 |

| RuffFw | 65.20 | 68.95 | 75.66 | 108.23 | 121.47 | 70.19 | 77.55 | 100.00 | 86.33 |

| RuffFa2 | 75.53 | 79.87 | 87.65 | 125.37 | 140.70 | 81.30 | 89.83 | 115.84 | 100.00 |

| Trackway A | |||||||||

| DingwallFa1 | DingwallFl | Grivas | DomjanicFw | DomjanicFl + Fw | RuffFa1 | RuffFl | RuffFw | RuffFa2 | |

| DingwallFa1 | 100.00 | 105.73 | 119.73 | 171.13 | 190.65 | 108.13 | 119.90 | 157.83 | 136.38 |

| DingwallFl | 94.58 | 100.00 | 113.24 | 161.86 | 180.32 | 102.27 | 113.40 | 149.28 | 128.99 |

| Grivas | 83.52 | 83.52 | 100.00 | 142.93 | 159.24 | 90.31 | 100.14 | 131.83 | 113.91 |

| DomjanicFw | 58.43 | 58.43 | 69.96 | 100.00 | 111.40 | 63.18 | 70.06 | 92.23 | 79.69 |

| DomjanicFl + Fw | 52.45 | 52.45 | 62.80 | 89.76 | 100.00 | 56.71 | 62.89 | 82.79 | 71.53 |

| RuffFa1 | 92.48 | 92.48 | 110.73 | 158.27 | 176.32 | 100.00 | 110.89 | 145.97 | 126.13 |

| RuffFl | 83.40 | 83.40 | 99.86 | 146.83 | 159.01 | 90.18 | 100.00 | 131.64 | 113.74 |

| RuffFw | 63.36 | 63.36 | 75.86 | 108.43 | 120.79 | 68.51 | 75.97 | 100.00 | 86.41 |

| RuffFa2 | 73.33 | 73.33 | 87.79 | 125.48 | 139.80 | 79.28 | 87.92 | 115.73 | 100.00 |

| Trackway B | |||||||||

| DingwallFa1 | DingwallFl | Grivas | DomjanicFw | DomjanicFl + Fw | RuffFa1 | RuffFl | RuffFw | RuffFa2 | |

| DingwallFa1 | 100 | 103.99 | 107.79 | 157.17 | 179.60 | 106.86 | 112.48 | 146.49 | 125.30 |

| DingwallFl | 96.16 | 100 | 103.65 | 151.14 | 172.71 | 102.76 | 108.16 | 140.87 | 120.49 |

| Grivas | 92.78 | 96.48 | 100 | 145.82 | 166.63 | 99.14 | 104.35 | 135.91 | 116.25 |

| DomjanicFw | 63.63 | 66.16 | 68.58 | 100 | 114.27 | 67.99 | 71.56 | 93.21 | 79.72 |

| DomjanicFl + Fw | 55.68 | 57.90 | 60.01 | 87.51 | 100 | 59.50 | 62.63 | 81.57 | 69.77 |

| RuffFa1 | 93.58 | 97.31 | 100.87 | 147.08 | 168.07 | 100 | 105.26 | 137.09 | 117.26 |

| RuffFl | 88.91 | 92.46 | 95.83 | 139.74 | 159.68 | 88.91 | 100 | 130.24 | 111.40 |

| RuffFw | 68.26 | 70.99 | 73.58 | 107.29 | 122.60 | 70.71 | 76.78 | 100 | 85.53 |

| RuffFa2 | 79.81 | 82.99 | 86.02 | 125.43 | 143.34 | 80.08 | 89.76 | 116.91 | 100 |

| SAMPLE B | |||||||||

| All Footprints | |||||||||

| DingwallFa1 | DingwallFl | Grivas | DomjanicFw | DomjanicFl + Fw | RuffFa1 | RuffFl | RuffFw | RuffFa2 | |

| DingwallFa1 | 100 | 106.35 | 121.01 | 167.59 | 184.86 | 107.50 | 120.91 | 152.04 | 134.24 |

| DingwallFl | 94.03 | 100 | 113.78 | 157.58 | 173.82 | 101.08 | 113.69 | 142.96 | 126.22 |

| Grivas | 82.64 | 87.89 | 100 | 138.49 | 152.76 | 88.84 | 99.92 | 125.64 | 110.93 |