1. Introduction

Green light laser photosensitive vaporisation of the prostate (GLL-PVP) is an alternative to transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for the surgical treatment of bladder outlet obstruction in men. GLL-PVP has been the second most common bladder outlet surgery procedure performed after TURP in Australia over the past few years [

1]. Compared to TURP, GLL -PVP is associated with decreased postoperative bleeding, decreased time with a catheter, and a low incidence of a failed first trial of void (TOV) post operation (between approximately 3.7% and 9%) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These factors allow for a postoperative day 1 TOV rather than on day 2, as is standard for TURP.

At Northern Health, the standard protocol for postoperative patients undergoing GLL-PVP to receive two bags of two-litre bladder washout at the full rate, which is then ceased Patients then proceed to a trial of void (TOV) day 1 after the operation after a morning review. It has been shown that patients undergoing GLL-PVP can perform the TOV on the same day as surgery, with some success [

7,

8]. However, same-day discharge with TOV has been trialled in patients treated with Holmium enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP). The findings indicated a steep learning curve for staff as well as significant time resource requirements and was impacted by extraneous factors, such as changes in surgical scheduling [

9,

10].

To mitigate these issues, our centre has implemented an at-home TOV pilot program. Even though patients were discharged on the day of surgery, they remained admitted under the care of Northern Health’s Hospital in the Home (HITH) service. The TOV was commenced on postoperative day (POD) 1 in the comfort of their own home. The benefit to the hospital was the freeing up of a bed, which would otherwise have been occupied during the time taken for the TOV. This improved patient flow and allowed for additional revenue generation from the freed acute inpatient bed, occupied by a new patient. The aim of this study was to audit the outcomes of the patients enrolled in this pilot program, as well as the health economics of running such a program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a retrospective audit of all patients enrolled in the pilot at-home TOV program after GLL-PVP between March 2023 and June 2024.

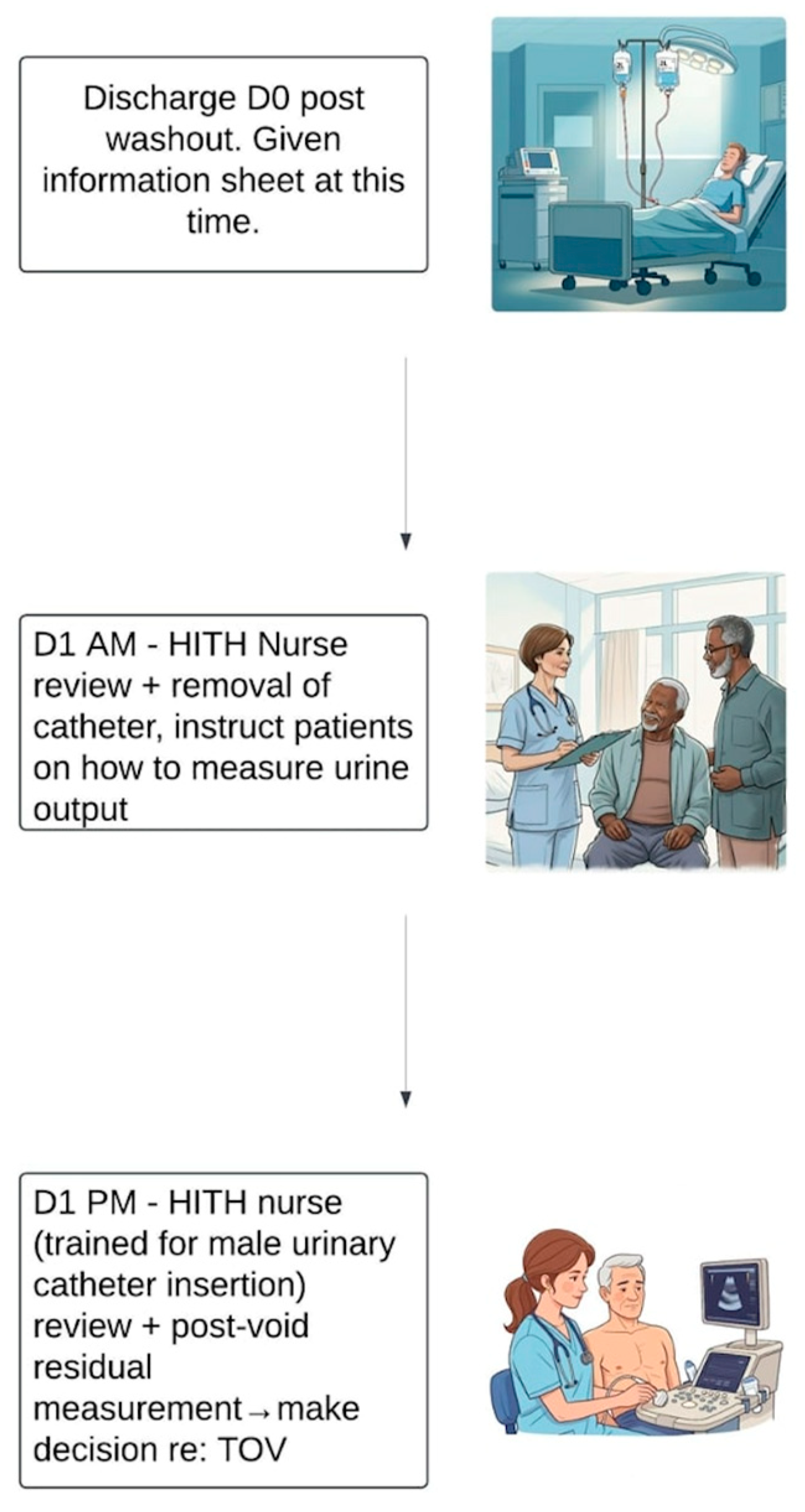

After GLL-PVP, all patients received bladder irrigation, consisting of two bags of 2 L saline, running at full rate. There was no further washout after this time. Following this, patients were transferred to the HITH service and discharged home on the day of surgery. Patients or carers were given an instruction sheet by the HITH nursing staff, which included the contact numbers of the HITH service and Northern Health’s virtual emergency department (ED). Catheter education was also provided prior to the patient going home.

The next morning, a HITH nurse visited the patient, assessed the status of the urine colour, and, if appropriate, commenced the TOV. The nurse instructed the patient or carer on how to measure their urine output; a bottle was given as an aid to assist with measuring this. Fluid input was also recorded. Approximately three hours after catheter removal, the HITH service contacted the patient to assess their progress, and any issues were escalated. Otherwise, a HITH nurse, trained in male urinary catheter insertion, returned in the afternoon to assess the patient. They reviewed the urine volume passed and performed a bladder scan, ideally soon after voiding.

In general, if the bladder scan was less than 250 mL and there were no other concerns, the TOV was considered successful. If the bladder scan found to be between 250 and 450 mL, the nurse encouraged the patient to double void, and then repeated the ultrasound. If the bladder scanned greater than 450 mL or there were clinical concerns regardless of the values, the HITH nurse escalated the case and contacted the urology team for advice. If advised, an indwelling urinary catheter (IDC) was reinserted. If the nurse was unable to re-insert the catheter after one attempt, the urology team was notified, and the patient was brought to hospital to a ward-located procedural room. Thus, the emergency department was bypassed (unless there was a co-existing medical concern). The patient had the catheter re-inserted by the on-duty urology resident. After catheter re-insertion, the patient was either discharged back home or, if indicated, admitted directly to the ward.

On day two after surgery, the HITH team performed a telehealth assessment, and, if clinically well, the patient was discharged from the HITH. If the patient consented, a standardised HITH questionnaire was conducted (

Appendix A).

Figure 1 visually details the study design as detailed above.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

All patients who underwent GLL-PVP that were either independent functionally or had a carer able to manage the urinary catheter and assist with measuring urine volumes were able to be included. Notably, the indication for surgery and anaesthetic type used during surgery were not factors that affected eligibility. Patients on anticoagulation at time of surgery, patients who refused the at-home TOV service, patients with a clinical concern upon time of transfer to home, and patients not able to be admitted to the HITH were excluded.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were the rate of success of the trial of void, as well as incidence of re-admission, urinary retention, and emergency department presentations within 48 h post operation. The incidences of re-admission, urinary retention, and emergency department presentations within 30 days after the operation were secondary outcome measures. Patient satisfaction, assessed through the HITH questionnaire, and additional revenue generation compared to costs involved were also assessed. Costs involved within 48 h post operation were calculated by Northern Health’s audit team.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For continuous variables, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normality. For normally distributed continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation were calculated, with Student’s t-test used for comparison across outcomes. For non-normally distributed, continuous variables, the median and 25th–75th quartiles were calculated, with the Mann–Whitney U test used for comparison across outcomes. For all categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison across outcomes. Univariate logistic regression analysis of all continuous and binary categorical variables was conducted to identify potential predictors of failed TOV.

3. Results

Within the study period, 30 out of 45 GLL-PVP patients underwent the at-home TOV process. The patient demographics of the whole cohort can be observed in

Table 1.

A total of 93.3% (28/30) of patients passed their TOV at home. The same two patients who failed their TOV at home were the only patients who showed urinary retention within 48 h post operation; these patients are now catheter-free. There were no re-admissions within 48 h of the operation. A total of 3 out of the 30 patients presented to the ED within 48 h post operation. One of the ED presentations was for a blocked IDC, which was resolved with a flush, and the patient subsequently proceeded to a successful TOV with the HITH. Another was for haematuria that did not require admission. The third ED presentation was for one of the patients that failed the TOV for their catheterisation; they did not go attend the treatment room for catheterisation due to a logistical error.

There were four patients who required re-admission during the 30-day period post operation. Three of these were for urinary tract infections (UTIs) requiring intravenous antibiotics, and one was for clot retention, which required a washout and evacuation in theatre. The clot retention in this patient occurred in the context of recommencing recent anticoagulation therapy. This patient was the same individual that had failed his TOV at home and had presented to the ED for catheterisation in error. There were six more ED presentations within the 30-day postoperative period; two of these were for dysuria, two were for haematuria, and the final two were for UTIs. Notably, one of the haematuria ED presentations was for a patient who subsequently required re-admission for their UTI, as mentioned above. The two further incidences of retention were in a patient who was re-admitted for a UTI and in a patient who presented to the ED with a UTI.

Table 2 shows that there were no statistically significant differences between those who experienced urinary retention, those who presented to the ED, and those who required re-admission compared to those who did not. This was true for both the 48 h and 30-day time periods post operation. There were no significant differences in the results when a univariate logistic regression was conducted to investigate the factors associated with the failed TOV; thus, no multivariate analysis was performed.

A total of 83% (25/30) patients consented and participated in the HITH questionnaire at the end of their admission. The results of the questionnaire are detailed in

Table 3. Most patients had no concerns with the service, and all reported as being happy with their care. Patient satisfaction was extremely high; 20 patients rated the service as very good, and 5 patients rated the service as good on the five-point scale. The most common experiences and positive remarks expressed were related to positive interactions with the HITH nursing staff.

An extra AUD 3377.56 in revenue was generated (0.56 of a national-weighted activity unit) per patient in the program by admitting another patient in the freed inpatient bed. This amounted to AUD 101,326.80 gross revenue generated. The revenue generation was in the context of a once-off purchase of a bladder scanner for AUD 15,249. The cost of the three ED presentations that occurred within 48 h of the GLL-PVPs was estimated to be AUD 3060.97. Since there was no impact on Northern Health’s HITH services’ workload or capacity, there was no additional costs to the HITH; if the volume of work increased, then additional HITH-equivalent full time would be an additional expense. Therefore, a net revenue of AUD 83,016.83 was generated over the study period.

4. Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study, it was found that TOV at home after GLL-PVP was highly successful with the framework that was used. Whilst this study was limited due to low number of patients overall, there were still various conclusions and areas of improvement that could be extrapolated from the patterns and trends observed in this study. Additionally, the review of the patient experience and economics involved provided vital insight and further justified the use of a program such as ours. The program could be identically translated to incorporate patients with HoLEP, which is also associated with lower postoperative bleeding than TURP [

11,

12]. Furthermore, TOV at home could be used for all patients after urological surgery, including TURP (on POD 2).

The zero re-admission rate at 48 h postoperation and the extremely high rate of success of TOV in this study’s patient group attest to the robustness of our study design. There could be unknown factors that pertain to a higher rate of success of TOV at home compared to in the hospital, which could be further investigated in a prospective study. Additionally, with better patient and staff communication, we believe that the all ED presentations during the 48 h after the operation could have been prevented; two patients could have been reviewed in the treatment room instead of the ED, and the other could have been cleared by review of our hospital’s virtual ED.

It is not suspected that 30-day retention rates, re-admission rates, and emergency department presentations would differ between patients having a TOV at home and in hospital. Having a control, which this study lacked, would prove this definitively. However, the postoperative UTI rate observed in the patients in the study cohort (16.7%) is within the rates seen in the literature for TURP (1–26%) and photosensitive vaporisation of the prostate (PVP) (18–20%) [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The occurrence of haematuria requiring admission of one of the patients (3.3%) was also not high given the sample size in the study cohort [

14,

17]. In terms of the 30-day ED presentations, better patient education on discharge and a follow-up call, as well as encouragement to use Northern Health’s virtual ED, could have prevented a significant amount of these. Specifically, a flowchart could have been provided on what to do if specific symptoms such as dysuria or haematuria were experienced. Confounding factors included the particular low health literacy and high prevalence of non-English-speaking patients in the Northern Health service district [

18,

19,

20].

The low sample size was a major factor in the inability to derive any statistically significant differences in

Table 2 and the insignificant results from the univariate analysis. With a larger sample size, it may have been possible to elucidate particular demographic or operative factors associated with the outcome measures used in this study to improve the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the novel model. For example, prostate volume, laser time, and 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors have been shown to be associated with urinary retention after GLL-PVP [

3]. Finally, the low sample size of patients studied and the low incidence of patients with urinary retention may have skewed the rate of TOV success favorably.

Despite the positive statistically significant results of the questionnaire, there were some key learning points derived. The education and teaching of the inpatient staff with the new model of care was not completely conducted, which caused confusion in one case (

Table 3). Also, as highlighted earlier, the patient education of the process throughout all steps could have been improved to address the case where the patient was unsure of the process (

Table 3). The patient who had to wait in the emergency department for a flush of their catheter could have easily had their issue managed in the ward treatment room (

Table 3). One patient would have preferred to have had his TOV at Northern Health’s infusion centre (where non-complex elective TOVs occur) (

Table 3). It has been previously shown that this has similar costs to TOV at home; however, it affects patient throughput and requires a different allocation of funding [

21]. In this study, even though our HITH nurses were trained in male IDC insertion, the patients who failed TOV did not have catheterisation attempted at home due to patient and nursing preference. Thus, this novel model of care could also be improved by training the HITH nurses beyond basic male IDC training.

A considerable strength of this study is the assessment of the costs involved and improved patient flow. It has been shown that improved patient flow leads to decreased exposure to iatrogenic risks but also improves quality of care and patient satisfaction [

22,

23]. The ability to increase patient flow whilst also increasing net revenue generated is extremely noteworthy.

5. Conclusions

This proof-of-concept study showed that a TOV at home after GLL-PVP is safe and feasible. Not only did the program have high patient satisfaction, but there were improved patient flow and additional revenue generated. A similar program may easily be adopted with success in other healthcare systems; other centres in Australia have already begun to adopt a similar model of care. The framework in this study can similarly be used for patients following HoLEP, TURP (on POD Day 2), as well as other procedures.

Author Contributions

A.G.—data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; S.F.—data curation (lead), formal analysis, investigation (lead), writing—review and editing; A.X.—formal analysis (lead), writing—review and editing; L.C.—investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; K.C.—writing—review and editing; D.G.—conceptualisation, methodology, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was granted by our centre’s Research Development and Governance Unit. Patients and carers involved all adequately consented regarding the at-home TOV process. Only anonymised data from patient medical records were extracted for analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study, as stated above.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge contributions from Northern Health’s Department of Urology and Hospital in the Home service.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GLL-PVP | Green Light Laser Photosensitive Vaporisation of the Prostate |

| TOV | Trial of Void |

| HITH | Hospital in the Home |

| TURP | Transurethral resection of the Prostate |

| HoLEP | Holmium Enuculation of the Prostate |

| POD | Postoperative Day |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| IDC | Indwelling Urinary Catheter |

| PVP | Photosensitive Vaporisation of the Prostate |

Appendix A

‘Community programs client experience survey’

1. Overall, how would you rate the care provided by our health service?

Very poor Poor Adequate Good Very good

2. Did you have any difficulties/problems with HITH (having the TOV@home)?

Yes No

If yes, detail the problems:

3. Happy with your care?

Yes No

Tell us what we did well:

4. What would have made a difference?

References

- Morton, A.; Williams, M.; Perera, M.; Teloken, P.E.; Donato, P.; Ranasinghe, S.; Chung, E.; Bolton, D.; Yaxley, J.; Roberts, M.J. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia in the 21st century: Temporal trends in Australian population-based data. BJU Int. 2020, 126 (Suppl. 1), 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, D.; Pirola, G.M.; Rubilotta, E.; Gubbiotti, M.; Scarcella, S.; Maggi, M.; Gauhar, V.; Teoh, J.Y.-C.; Galosi, A.B. GreenLight Laser™ Photovaporization versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Res. Rep. Urol. 2021, 13, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campobasso, D.; Acampora, A.; De Nunzio, C.; Greco, F.; Marchioni, M.; Destefanis, P.; Altieri, V.; Bergamaschi, F.; Fasolis, G.; Varvello, F.; et al. Post-Operative Acute Urinary Retention After Greenlight Laser. Analysis of Risk Factors from A Multicentric Database. Urol. J. 2021, 18, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ajib, K.; Mansour, M.; Zanaty, M.; Alnazari, M.; Hueber, P.A.; Meskawi, M.; Valdivieso, R.; Tholomier, C.; Pradere, B.; Misrai, V.; et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with the 180-W XPS-Greenlight laser: Five-year experience of safety, efficiency, and functional outcomes. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 12, E318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, J.C.; Suso-Palau, D.; Sejnaui, J.E.; Aluma, L.; Mendoza, L.; Ramirez, G.; Morales, C.; Usubillaga, F.; Mendoza, S.; Rivera, F.; et al. Outpatient 180 W XPS GreenLight Laser Photoselective Vaporization of the Prostate: 7-Year Experience. J. Endourol. 2021, 36, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangasamy, I.A.; Chalasani, V.; Bachmann, A.; Woo, H.H. Photoselective Vaporisation of the Prostate Using 80-W and 120-W Laser Versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis from 2002 to 2012. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmansy, H.; Shabana, W.; Ahmad, A.; Hodhod, A.; Hadi, R.A.; Tablowski, T.; Zakaria, A.S.; Fathy, M.; Labib, F.; Kotb, A.; et al. Factors Predicting Successful Same-Day Trial of Void (TOV) After Laser Vaporization of the Prostate. Urology 2022, 165, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, E.B.; Ravivarapu, K.T.; Levy, M.; Chin, C.P.; Omidele, O.; Tomer, N.; Al-Alao, O.; Araya, J.S.; Small, A.C.; Palese, M.A. The Utilization and Safety of Same-Day Discharge After Transurethral Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Surgery: A Case-Control, Matched Analysis of a National Cohort. Urology 2022, 165, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, D.K.; Large, T.; Tong, Y.; Stoughton, C.L.; Damler, E.M.; Nottingham, C.U.; Rivera, M.E.; Krambeck, A.E. Same Day Discharge is a Successful Approach for the Majority of Patients Undergoing Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lee, M.S.; Assmus, M.; Krambeck, A.E. Barriers to Implementation of a Same-Day Discharge Pathway for Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate. Urology 2022, 161, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naspro, R.; Suardi, N.; Salonia, A.; Scattoni, V.; Guazzoni, G.; Colombo, R.; Cestari, A.; Briganti, A.; Mazzoccoli, B.; Rigatti, P.; et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates >70 g: 24-month follow-up. Eur. Urol. 2006, 50, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tooher, R.; Sutherland, P.; Costello, A.; Gilling, P.; Rees, G.; Maddern, G. A systematic review of holmium laser prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 1773–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaywid, B.S.; Smith, G.H.H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for transurethral urological surgeries: Systematic review. Urol. Ann. 2013, 5, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, A.; Tubaro, A.; Barber, N.; d’Ancona, F.; Muir, G.; Witzsch, U.; Grimm, M.-O.; Benejam, J.; Stolzenburg, J.-U.; Riddick, A.; et al. 180-W XPS GreenLight Laser Vaporisation Versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Obstruction: 6-Month Safety and Efficacy Results of a European Multicentre Randomised Trial—The GOLIATH Study. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, K.; Motzer, J.; Roth, J.A.; Dangel, M.; Seifert, H.-H.; Widmer, A.F. High incidence of urinary tract infections after photoselective laser vaporisation of the prostate: A risk factor analysis of 665 patients. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colau, A.; Lucet, J.C.; Rufat, P.; Botto, H.; Benoit, G.; Jardin, A. Incidence and Risk Factors of Bacteriuria after Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. Eur. Urol. 2001, 39, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.E.; Casanova, N.F.; Wallner, L.P.; Dunn, R.L.; Hedgepeth, R.C.; Faerber, G.J.; Wei, J.T. Risk Factors for Delayed Hematuria Following Photoselective Vaporization of the Prostate. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, R.L.; Osborne, R.H.; Beauchamp, A.; Bourne, A.; Buchbinder, R. Health literacy of recently hospitalised patients: A cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, R.L.; Osborne, R.H.; Beauchamp, A.; Bourne, A.; Buchbinder, R. Differences in health literacy profiles of patients admitted to a public and a private hospital in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastistics ABo. Whittlesea, Hume, Moreland—Census All Persons QuickStats 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA27070 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Pugh, J.D.; Twigg, D.E.; Giles, M.; Myers, H.; Gelder, L.; Davis, S.M.; King, M. Impact and costs of home-based trial of void compared with the day care setting. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.; Ow, T.T.; Kohli, R. Examining the impact of information technology and patient flow on healthcare performance: A Theory of Swift and Even Flow (TSEF) perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, P.B.; Illg, M.L.; Sweeney, B.E. A Successful Model for a Comprehensive Patient Flow Management Center at an Academic Health System. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2014, 31, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).