Intraurethral Steroid and Clean Intermittent Self-Dilatation for Lichen Sclerosus Proven Urethral Stricture Disease—A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

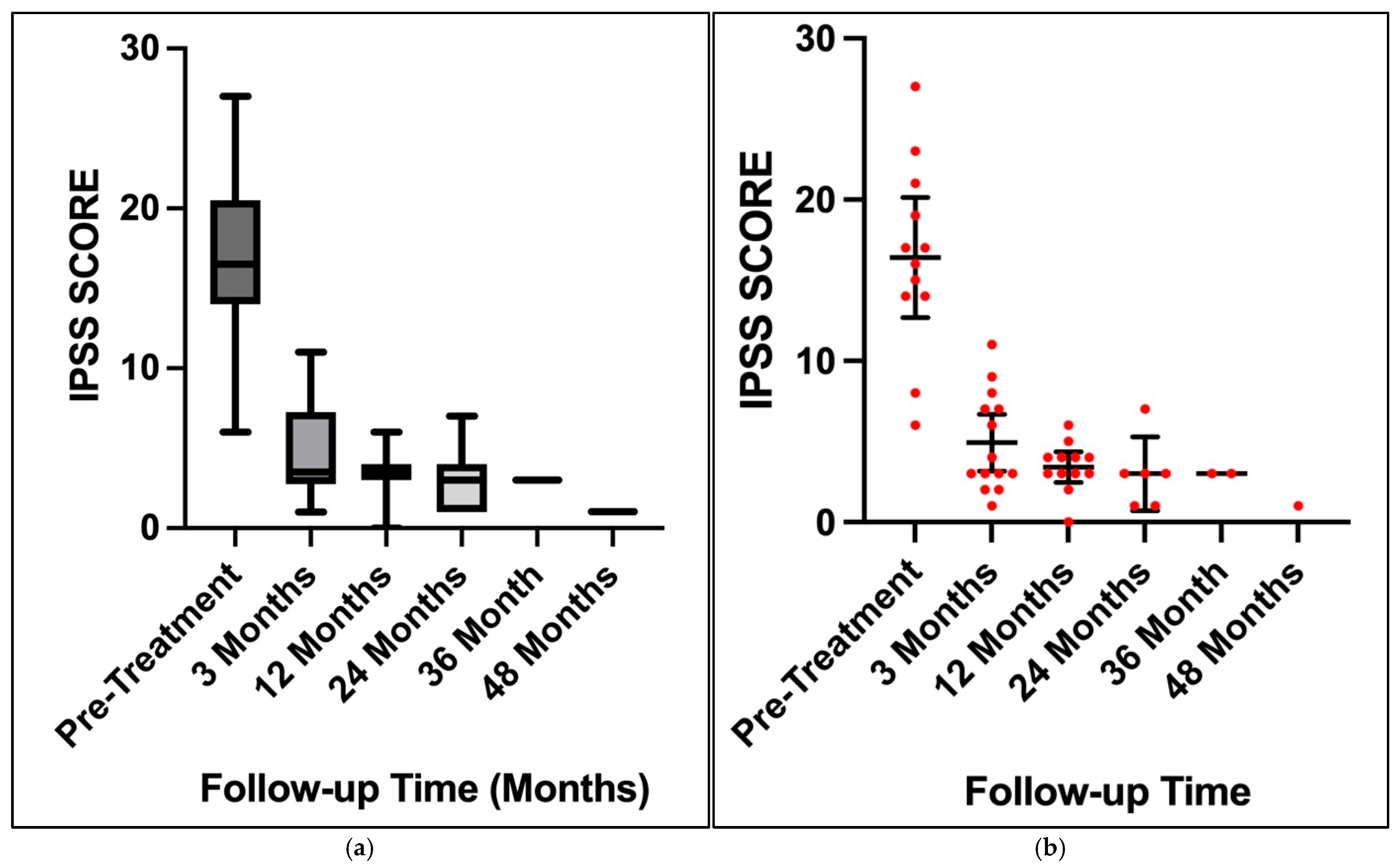

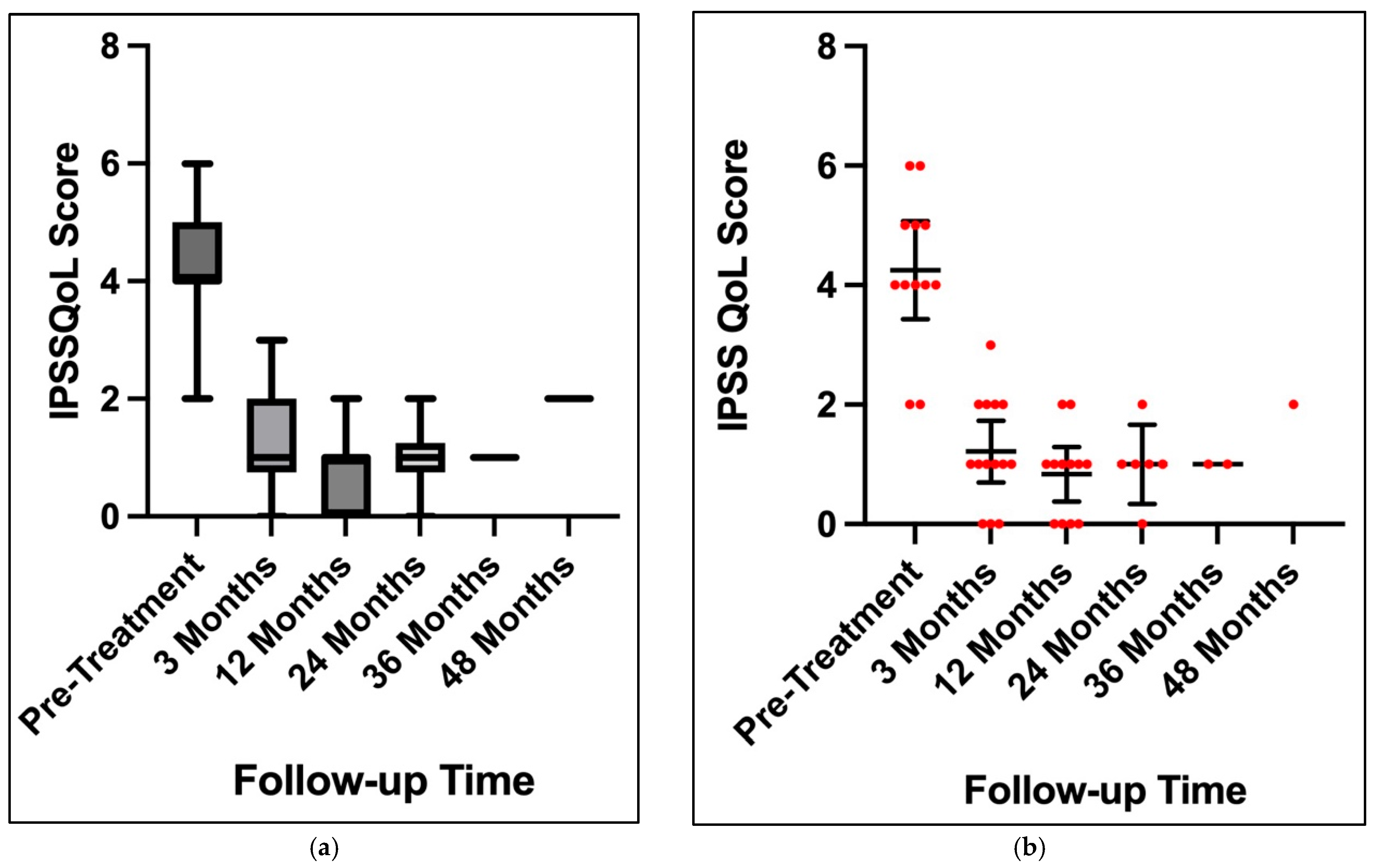

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LS | Lichen Sclerosus |

| IPSS | International Prostate Symptom Score |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| LUTS | Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| CISD | Clean Intermittent Self Dilation |

| IDC | Indwelling Catheter |

| CISC | Clean Intermittent Self-Catheterisation |

| BPH | Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia |

References

- Neill, S.M.; Lewis, F.M.; Tatnall, F.M.; Cox, N.H. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus 2010. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fistarol, S.K.; Itin, P.H. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: An update. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2013, 14, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.M.; Peterson, A.C. Lichen sclerosus: Epidemiological distribution in an equal access health care system. J. Urol. 2011, 185, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, H.J. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans. St. Johns. Hosp. Dermatol. Soc. 1971, 57, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Depasquale, I.; Park, A.J.; Bracka, A. The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU Int. 2000, 86, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumen, N.; Campos-Juanatey, F.; Greenwell, T.; Martins, F.E.; Osman, N.I.; Riechardt, S.; Waterloos, M.; Barratt, R.; Chan, G.; Esperto, F.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Urethral Stricture Disease (Part 1): Management of Male Urethral Stricture Disease. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, B.A.; Belsante, M.J.; Peterson, A.C. Intraurethral Steroids are a Safe and Effective Treatment for Stricture Disease in Patients with Biopsy Proven Lichen Sclerosus. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Leslie, S.W.; Baradhi, K.M. Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanski, A.T.; Zhang, L.T.; Muise, A.C.; Copacino, S.A.; Holst, D.D.; Zinman, L.N.; Buckley, J.C.; Vanni, A.J. Conservative Management of Lichen Sclerosus Male Urethral Strictures: A Multi-Institutional Experience. Urology 2021, 152, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, K.B.; Lee, A.W.; Baradaran, N.; Cohen, A.J.; Stohr, B.A.; Erickson, B.A.; Mmonu, N.A.; Breyer, B.N. Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment of lichen sclerosus: A systematic review. Urology 2020, 135, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, F.M.; Tatnall, F.M.; Velangi, S.S.; Bunker, C.B.; Kumar, A.; Brackenbury, F.; Mohd Mustapa, M.F.; Exton, L.S. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus, 2018. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, R.K.; Khan, I.; Khan, D. Study of intraurethral instillation of tacrolimus for urethral involvement following lichen sclerosus. Int. J. Sci. Study 2017, 5, 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, K.H.; Chapple, C.R.; Chatters, R.; Downey, A.P.; Harding, C.K.; Hind, D.; Watkin, N.; Osman, N.I. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Adjuncts to Minimally Invasive Treatment of Urethral Stricture in Men. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Hossain, S.M.; Islam, M.T.; Kobir, G.; Basu, B.K. Use of intra-urethral steroid clobetasol cream to prevent the recurrence of urethral stricture after optical urethrotomy: Randomized clinical trial. Mediscope 2019, 6, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperto, F.; Verla, W.; Ploumidis, A.; Barratt, R.; La Rocca, R.; Lumen, N.; Yuan, Y.; Campos-Juanatey, F.; Greenwell, T.; Martins, F.; et al. What is the role of single-stage oral mucosa graft urethroplasty in the surgical management of lichen sclerosus-related stricture disease in men? A systematic review. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Qi, E.; Zhang, Y.; Sa, Y.; Fu, Q. Efficacy and safety of local steroids for urethra strictures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Endourol. 2014, 28, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, S.; Adhikari, S.C.; Yadav, S.; Singh, R.R.; Bastakoti, R. Efficacy of Use of Triamcinolone Ointment for Clean Intermittent Self Catheterization following Internal Urethrotomy. JNMA J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2018, 56, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergün, O.; Güzel, A.; Armağan, A.; Koşar, A.; Ergün, A.G. A prospective, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of clean intermittent catheterization versus triamcinolone ointment and contractubex ointment of catheter following internal urethrotomy: Long-term results. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2015, 47, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.P.; Boysen, W.R.; Peterson, A.C. Medical Management of Penile and Urethral Lichen Sclerosus with Topical Clobetasol Improves Long-Term Voiding Symptoms and Quality of Life. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 1290–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, S.; Khare, E.; Pal, D.K. Comparative effect of intraurethral clobetasol and tacrolimus in lichen sclerosus-associated urethral stricture disease. Urol. Ann. 2023, 15, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, J.N.; Malkawi, I.; Dhradkeh, M.; Joshi, P.M.; Kulkarni, S.B.; Lazzeri, M.; Barbagli, G.; Mori, R.; Angermeier, K.W.; Storme, O.; et al. A Multi-institutional Evaluation of the Management and Outcomes of Long-segment Urethral Strictures. Urology 2015, 85, 1483–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsante, M.J.; Selph, J.P.; Peterson, A.C. The contemporary management of urethral strictures in men resulting from lichen sclerosus. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2015, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiguchi, A.; Shinchi, M.; Masunaga, A.; Ito, K.; Asano, T.; Azuma, R. Do Transurethral Treatments Increase the Complexity of Urethral Strictures? J. Urol. 2018, 199, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudak, S.J.; Atkinson, T.H.; Morey, A.F. Repeat transurethral manipulation of bulbar urethral strictures is associated with increased stricture complexity and prolonged disease duration. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 18 |

| Mean age at diagnosis (Years) | 52.27 (26–73) |

| Median Follow-up Time in Months (Range) | 24.5 (5–50) |

| Disease Location | Number of Patients (n) |

|---|---|

| Meatal/Submeatal | 4 |

| Meatal/Submeatal + Bulbar Urethra | 2 |

| Meatal//Submeatal + Penile Urethra | 1 |

| Bulbar Urethra | 1 |

| Penile + Bulbar Urethra | 2 |

| Panurethral | 5 |

| Data Missing | 3 |

| Complication | Total (n) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Haematuria | 1 | Developed significant haematuria following self-catheterisation which prompted an admission for bladder washout at the bedside. Able to continue treatment following resolution. |

| Balanitis | 1 | Recurrent flares of balanitis with steroids and CISD, unable to tolerate despite multiple attempts leading to cessation of treatment. |

| Treatment Required | Total (n) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Repeat endoscopic dilatation | N = 1 | After their initial 3-month review, the patient chose to discharge from the clinic due to stable symptoms. He was re-referred 27 months after initial dilatation with deterioration of symptoms requiring repeat dilatation—he informed our staff that he was non-compliant with treatment in the intervening period. He is now compliant with stable lower urinary tract symptoms. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buckby, A.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Kahokehr, A. Intraurethral Steroid and Clean Intermittent Self-Dilatation for Lichen Sclerosus Proven Urethral Stricture Disease—A Retrospective Cohort Study. Soc. Int. Urol. J. 2025, 6, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6040050

Buckby A, Shanmugasundaram R, Kahokehr A. Intraurethral Steroid and Clean Intermittent Self-Dilatation for Lichen Sclerosus Proven Urethral Stricture Disease—A Retrospective Cohort Study. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal. 2025; 6(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuckby, Alex, Ramesh Shanmugasundaram, and Arman Kahokehr. 2025. "Intraurethral Steroid and Clean Intermittent Self-Dilatation for Lichen Sclerosus Proven Urethral Stricture Disease—A Retrospective Cohort Study" Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal 6, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6040050

APA StyleBuckby, A., Shanmugasundaram, R., & Kahokehr, A. (2025). Intraurethral Steroid and Clean Intermittent Self-Dilatation for Lichen Sclerosus Proven Urethral Stricture Disease—A Retrospective Cohort Study. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal, 6(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6040050