Abstract

Purpose The Société Internationale d’Urologie (SIU) conducted a survey to determine whether the pandemic has harmed the mental health of practicing urologists worldwide. Methods Members of the Executive Board of the SIU designed a self-selected survey consisting of multiple- choice questions about the safety and mental health of urologists during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was disseminated by email to SIU members worldwide. Result A total of 3448 SIU members from 109 countries responded to the survey, which sought to determine the extent of mental health symptoms, including depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress—experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, 21% of urologists who responded reported that their mental health was very challenged, with 58% indicating increased stress levels, and 15% indicating greatly increased stress levels. Older urologists were less likely to report any of the negative mental health symptom queried (ie, delirium [rs = −0.06, P = 0.001], psychosis [rs = −0.04, P = 0.019], anxiety [rs = −0.09, P < 0.001], depression [rs = −0.08, P <0.001], distress [rs = −0.07, P < 0.001]), except insomnia (P > 0.20). Furthermore, 29% of urologists indicated they were afraid to go to work, while 53% reported being afraid to go home to their families after work. Conclusions In this worldwide survey of practicing urologists, more than half of the participants reported an increase in insomnia, distress, and other psychological symptoms as they managed patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, although half of respondents did not experience any mental health symptoms. Institutions should provide psychological coping resources to all health care staff, not only for the front-line workers during the pandemic.

Introduction

Data have begun to emerge about the ongoing pandemic’s psychological impacts on the front-line health care workers who have faced severe and unprecedented stressors in providing patient care [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. As the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak began in late 2019, leading health organizations rushed to provide resources to help front- line health care workers cope with the psychological stress, basing their response on experiences with the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic and the Ebola epidemic (2013–2016), among others [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

COVID-19 has altered the way in which health care workers currently practice medicine and deliver care, regardless of specialty or discipline. From the curtail- ment of routine and elective care to the intensification of protective protocols to the redeployment of non-specialist physicians to assist with direct care of COVID-19 patients, the practice of medicine in the first months of 2020 differs substantially from late 2019 norms.

Urologists (one of the affected groups of medical specialists) typically divide their time between patient consultations and surgery. They are not on the front line as emergency responders. However, because of increased staffing needs during the pandemic, some urologists and physicians in other second-line specialties have been redeployed to the emergency departments or COVID-19 tents to assist with triage of presumed COVID-19 patients, as well as to COVID-19 in-patient units and to intensive care units to manage critically ill patients.

As the clinical demands faced by health care practitioners have changed, so have the challenges of maintaining mental health equilibrium during an uncertain time. Thus, the mental health of all medical workers, including those outside the emergency medicine and critical care disciplines, warrants evaluation during the pandemic. In this survey, the Société Internationale d’Urologie (SIU) aimed to capture the mental health challenges urologists are facing and to determine if these challenges vary by region, gender, or age groups.

Methods

Members of the Executive Board of the SIU designed the survey on safety and mental health. This was a self- selected survey comprising multiple-choice questions about respondents’ demographics, as well as concerns related to contracting COVID-19 and the provision by health care institutions of personal protective equipment (PPE); information about how to protect staff and patients from COVID-19; and tools/support for managing increased stress. The full survey has been published, and issues related to PPE have been addressed separately [17]. This analysis deals with participants’ reports of concerns and stresses related to COVID-19, and the support they received from their institutions.

The survey was opened on April 16, 2020, and closed on May 1, 2020. It was administered online using the Aventri platform (Connecticut, US). Distribution of the survey took place via email, using names on the SIU eNews mailing distribution list (15 252 contacts). The survey included the reasons why it was being conducted and the importance of participation. No compensation was offered for its completion. All responses were anonymous.

To facilitate analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on health care settings as it spread from East to West, respondents were grouped into the following regions: East/Southeast Asia and nearby regions, West/Southwest Asia and nearby regions, Europe, Africa, North America, and South America. The list of countries included in each region has been published elsewhere [17]. Information about age and gender was also analyzed to determine the impact of these parameters on mental health.

Statistical Analysis Strategy

Continuous variables were analyzed using omnibus one-way ANOVAs, with follow-up pairwise tests that were Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons. Categorical questions were analyzed using omnibus Pearson chi-square tests, with a follow-up examination of the adjusted standardized residuals, which were also Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons.

Data were analyzed by respondent age (selected from the following 4 categories: <40, 40–50, 51–60, >60), gender, and geographical region. Age was analyzed using Spearman rank-order correlations (rs).

Results

The SIU has a Central Office located in Montreal, Canada, and is governed by an international Board of Directors, with representatives in all continents. The SIU currently has 10018 members in 131 countries. A total of 3488 participants took the survey and the background demographics have been published elsewhere [17].

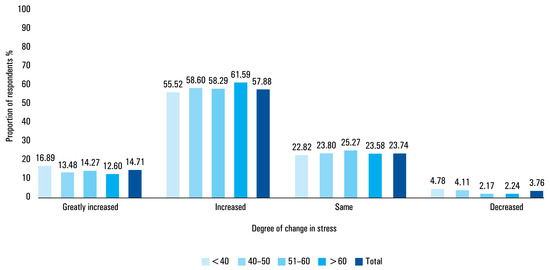

Overall, 21% of urologists reported that their mental health and that of their colleagues was very challenged during this pandemic, with 58% indicating that their stress levels increased, and 15% indicating their stress levels greatly increased (Figure 1). While urologists reported feeling appreciated as doctors involved in treating patients during the COVID-19 pandemic (median score, 7; range, 0–10), they reported that their mental health has been challenged significantly during the pandemic (median score, 6; range, 0–10).

Figure 1.

Impact of COVID-19 on stress level, by age (Survey question 22).

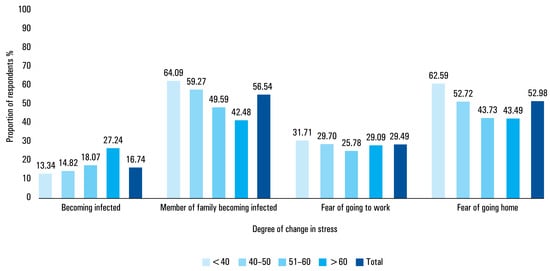

In total, 29% of urologists reported that they were afraid to go to work and 53% reported that they were afraid to go home to their families after work. Urologists’ greatest reported fear relating to their work was infecting their families (57%), with 17% reporting fear that they might infect themselves (Figure 2). In addition, 14% of urologists reported that their biggest fear was that their ability to provide patient care would be compromised, and 10% reported that their biggest fear was that their institutions would not be able to handle the patient load.

Figure 2.

Biggest fears about COVID-19, by age (Survey question 23).

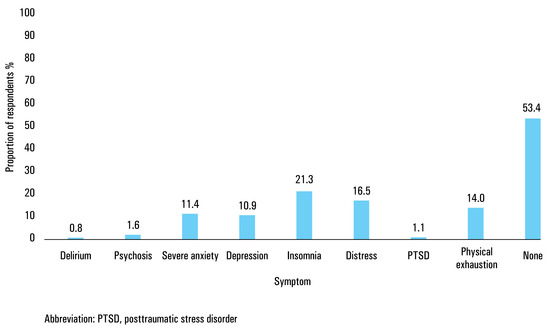

Many urologists reported that the challenge to their mental health may have resulted in symptoms of insomnia (21%), distress (17%), physical exhaustion (14%), severe anxiety (11%), depression (11%), psychosis (1.6%), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1%), or delirium (1%). More than half (53%) the respondents reported experiencing no symptoms due to stress from COVD-19 (Figure 3). Overall, 84% of urologists reported that they know how to protect themselves, and 74.5% said they were getting enough time off work to be healthy and recharge.

Figure 3.

Experience of symptoms due to COVID-19 (Survey question 24).

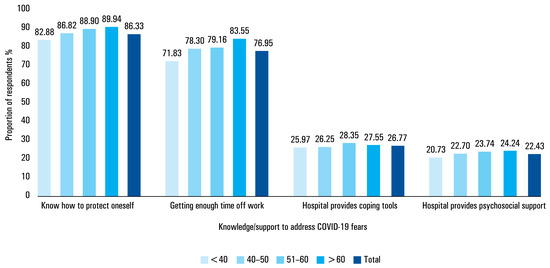

In total, only 27% of urologists reported receiving psychological or emotional coping tools or suggestions from their institutions (Figure 4). Among urologists who reported receiving these tools, 61% indicated they were provided with the option of meeting with mental health professionals, 33% reported receiving handouts on mental health, and 25% reported having access to workshops. In addition, 10% reported being required to meet with a mental health professional. Also, among urologists who reported receiving psychological or emotional coping tools, 53% received only one such tool, while 24% received 2 and 22% received 3 or more.

Figure 4.

Ability/support received to address fears about COVID-19, by age (survey question 25).

Only 22% of respondents indicated there was a team member, such as a nurse, psychosocial worker, or community social worker, trained to provide support to the health care team (Figure 4). Among the 78% who reported not receiving such support, 53% thought it would be helpful to have it.

Analyses were performed by gender, region, and age. The analysis of gender and geographical region did not yield clinically relevant results.

Age differences

Older urologists reported feeling more appreciated than younger urologists as doctors involved in treating patients during COVID-19 (rs = 0.11, P < 0.001). They were less likely than younger urologists to report that their own mental health and that of their colleagues was challenged during this pandemic (rs = −0.08, P < 0.001). Older urologists were also less likely than younger urologists to report fear of going to work (rs = −0.04, P = 0.025) or going home after work (rs = −0.16, P < 0.001). They also reported experiencing less avoidance by their family or community (rs = −0.10, P < 0.001), were more likely than younger urologists to report being most afraid that they would become infected (rs = 0.11, P < 0.001), and less likely to report being most afraid that members of their family would become infected (rs = −0.15, P < 0.001).

Every negative mental health symptom queried (except insomnia [P > 0.20]) was less common in older urologists: delirium (rs = −0.06, P = 0.001), psychosis (rs = −0.04, P = 0.019), anxiety (rs = −0.09, P < 0.001), depression (rs = −0.08, P < 0.001), distress (rs = −0.07, P < 0.001), PTSD (rs = −0.04, P = 0.025), and physical exhaustion (rs = −0.10, P < 0.001). Older urologists were less likely to report such outcomes overall (rs = −0.14, P < 0.001), but they were more likely to report having no symptoms (rs = 0.12, P < 0.001).

Older urologists were more likely than younger urologists to report feeling that they knew how to protect themselves at work from becoming infected with COVID-19 (rs = 0.08, P < 0.001), and were more likely to report getting enough time off work to recover and recharge (rs = 0.09, P < 0.001). Older urologists were also less likely to report sleeping at their institutions (rs = −0.24, P < 0.001).

Older urologists were not more likely than younger urologists to report that their institutions provided them with psychological or emotional coping tools (P > 0.25) or to report that there was someone on their team trained to provide psychosocial support (rs = 0.03, P = 0.065). Among urologists who said that there was no such person on their team, older urologists were less likely than younger urologists to say that such a person would be helpful (rs = −0.10, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Recent evidence suggests that COVID-19 has taken its toll on the mental and physical health of physicians and related health professionals, as well as on the general population [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

This survey addressed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental well-being of urologists, who typically do not work with infected patients. Nonetheless, physical or mental symptoms due to COVID-19 were reported by nearly half of urologists. Despite their lack of front-line exposure to COVID-19 patients, urologists reported overall high rates of negative mental health and well-being outcomes. Almost one-third reported that they were afraid to go to work, while more than half reported that they were afraid to go home to their families after work. These findings may be explained by the fact that health care workers are fighting an invisible and virulent enemy in high-risk settings. A continuous and seemingly endless number of COVID-19 patients have been treated by urologists during the past months, which has relentlessly challenged the boundaries of their own mental and physical limits.

With limited short-term perspective on the one hand, and lack of PPE and mental health support on the other, it comes as no surprise that the challenges we are facing are similar to those encountered during earlier pandemics such as SARS; however, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is novel. During the past decade(s), health care systems have evolved, with the training of physicians occurring under strict working directives and hours-of-service limits. An increasing number of physicians are working fewer hours per week and giving greater importance to their quality of life rather than making work their priority.

While we did not observe any striking differences in mental health impact by region or gender, we observed significant differences in various mental health domains among age groups. Older urologists reported that their mental health and that of their colleagues was less challenged during this pandemic than the mental health of younger urologists, and they were less likely than younger urologists to be afraid to go to work or afraid they would infect their family when they returned home. On the other hand, older urologists were more likely to be concerned about becoming infected themselves. Given that their age makes them more vulnerable, this is a reasonable reaction.

Although we did not observe high proportions of reports of severe negative mental health outcomes, such as delirium, psychosis, or PTSD, there were relatively high rates of reported anxiety, depression, insomnia, and distress. All symptoms except insomnia were more likely to be reported by younger urologists. Older urologists were also more likely than their younger counterparts to report having no mental health symptoms at all.

This analysis offers the prospect of constructing a profile of the most psychologically vulnerable. This would be difficult within the present dataset. While the initial analysis suggested that single urologists showed several worse mental health outcomes than those with partners, after controlling for age, the social environment factor no longer emerged as an independent predictor. Only age was predictive.

Older urologists reported feeling more appreciated than younger urologists, and they were less likely than younger urologists to indicate that their mental health and that of colleagues was challenged during this pandemic.

Despite the challenges that urologists face in terms of their mental health and well-being, they reported that they were not receiving adequate coping tools from their institutions. Only 22% had a team member trained to provide psychosocial support and 53% of those who did not have such support reported that it would be helpful.

Both patients and health care professionals have been affected by the psychosocial consequences of the COVID-19 crisis [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Several groups have been working on specific guidelines for mental health services for the COVID-19 outbreak, but their efforts may not have reached non-front-line health care professionals.

The greater impact on the psychological functioning of younger doctors warrants further exploration. The effectiveness of this approach has been demonstrated among health care workers in China, where early intervention decreased the prevalence of insomnia in front-line professions within a short time period [18]. In addition, during the previous SARS outbreak, health care workers with higher levels of trust in equipment or infection-control initiatives showed lower levels of emotional exhaustion and mental problems [19].

The present survey provides a global snapshot of a group of medical specialists who are partly involved in handling and treating COVID-19-infected patients. Adverse psychological effects were common, and adequate support was rare. We propose that large-scale epidemiological surveys be conducted to help examine the prevalence of mental health problems associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in different sub- populations, including health care workers. We hope that these findings may be shared with our colleagues in psychology/psychiatry to benefit further research and address the growing problem in mental health issues during the pandemic.

These are extraordinary times demanding extraordi- nary actions. We believe that health care workers need and are entitled to adequate work-related psychosocial supports from their institutions. We conclude by quoting Greenberg et al.: “There is a pressing need to ensure that the tasks ahead do not cause long-lasting damage to health care staff. They will be the heroes of the day, but we will need them for tomorrow” [7].

There are several limitations to this survey. First, the questionnaire itself was not validated, as we aimed to capture the data rapidly during the initial stages of the pandemic. This survey is limited by its self- selected nature. The survey was restricted to urologists, because of the composition of SIU membership. The participation by region of urologists in Africa and South America was low, as was the participation of women (11.4%). Unfortunately, the subdivision of regions was decided at the time of the survey preparation and did not directly correspond to the WHO regional classification, so it was not possible to compare the pandemic load by region with the WHO data [8]. In addition, we did not find any significant differences in outcome by region. The survey’s strength is that it provides a global snapshot of the mental health conditions in a significant sample size (3488 participants). It seems apparent from the survey that there is a worldwide need for further resources to address the adverse mental health effects of the pandemic on urologists and other health care workers.

Conclusions

Urologists face substantial struggles with respect to their mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many are not offered adequate coping tools or support from their institutions. Older urologists reported better mental health and well-being outcomes than younger urologists.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the SIU Central Office, including Merveille de Souza, Carrie Thompson, Melissa St-Onge, Susie Petrusa, and Christine Albino, for editorial support; and the contributions of Darcy Lewis and Alison Palkhivala for medical writing support, and Michael Barlev for statistical support.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felice, C.; Di Tanna, G.; Zanus, G.; Grossi, U. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on health care workers in Italy: Results from a national e-survey. J. Community Health. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, J. Prioritizing physician mental health as COVID-19 marches on. JAMA 2020, 323, 2235–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, D.; Haase, J.E.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, S.; et al. The experience of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e790–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, N.; Docherty, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Wessely, S. Managing mental health challenges faced by health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak. World Health Organization, 18 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/ docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations. pdf?sfvrsn=6d3578af_10 (accessed on 26 May 2020.).

- American Medical Association. Managing Mental Health During COVID-19. American Medical Association, 24 April 2020. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ managing-mental-health-during-covid-19 (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Smith, M.W.; Smith, P.W.; Kratochvil, C.J.; Schwedhelm, S. The psychosocial challenges of caring for patients with Ebola virus disease. Health Secur. 2017, 15, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.C.; Shu, B.C.; Chang, Y.Y.; Lung, F.W. The mental health of hospital workers dealing with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Psychother Psychosom. 2006, 75, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancee, W.J.; Maunder, R.G.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Coauthors for the Impact of SARS Study. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Toronto hospital workers one to two years after the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlonan, G.M.; Lee, A.M.; Cheung, V.; Cheung, C.; Tsang, K.W.T.; Sham, P.C.; et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Can. J. Psychiatry 2007, 52, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.M.; Lin, C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Chue, C.M.; Chou, P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004, 55, 1055–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kang, W.S.; Cho, A.R.; Kim, T.; Park, J.K. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018, 87, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.; Hunter, J.; Vincent, L.; Bennett, J.; Peladeau, N.; Leszcz, M.; et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ 2003, 168, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de la Rosette, J.; Laguna, P.; Álvarez-Maestro, M.; Eto, M.; Mochtar, C.A.; Albayrak, S.; et al. Cross-continental comparison of safety and protection measures amongst urologists during COVID-19. Int. J. Urol. 2020, 27, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Jin, Y.; Cheung, T. Joint International collaboration to combat mental health challenges during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 989–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, Z.; Greenglass, E.R.; Coffey, S. The relevance of psychosocial variables and working conditions in predicting nurses’ coping strategies during the SARS crisis: an online questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

This is an open access article under the terms of a license that permits non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. © 2021 The Authors. Société Internationale d'Urologie Journal, published by the Société Internationale d'Urologie, Canada.