Comparison of Typical and Atypical Community Acquired Pneumonia Cases in Hospitalized Patients in Two Tertiary Centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Highlights

- Of all episodes hospitalized with CAP, 65% underwent molecular testing via PCR.

- Of those, atypical pneumonia organisms were identified in 2.09%, with Mycoplasma pneumoniae being the most common identified atypical pathogen.

- Molecular testing should be utilized more frequently in CAP hospitalized patients.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistics Presentation

2.4. Tools Used

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Atypical CAP

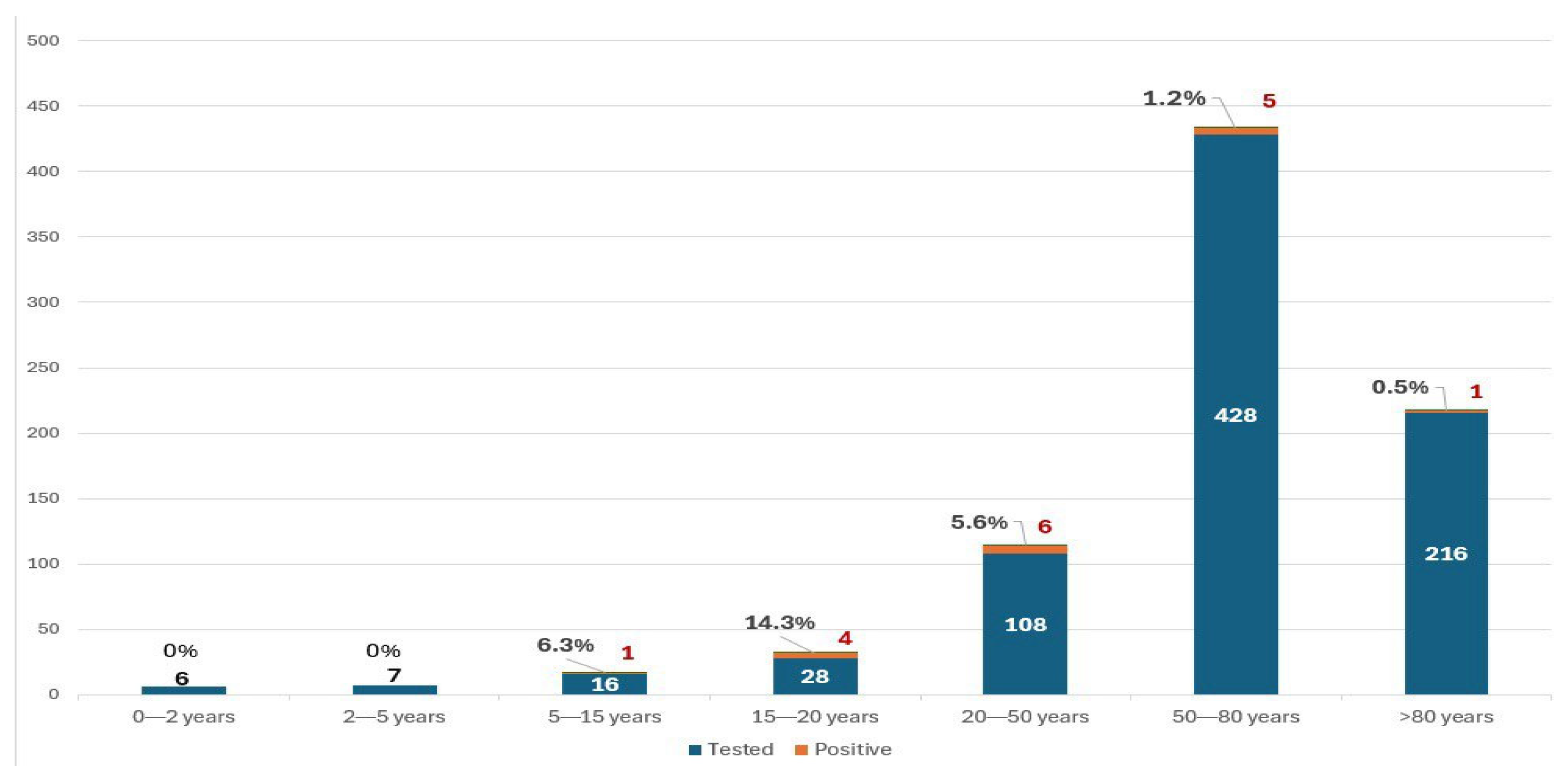

3.2. Demographics

3.3. Pathogens

3.4. Hospitalization and ICU Stay

3.5. Outcome

3.6. Recurrence

3.7. Readmission

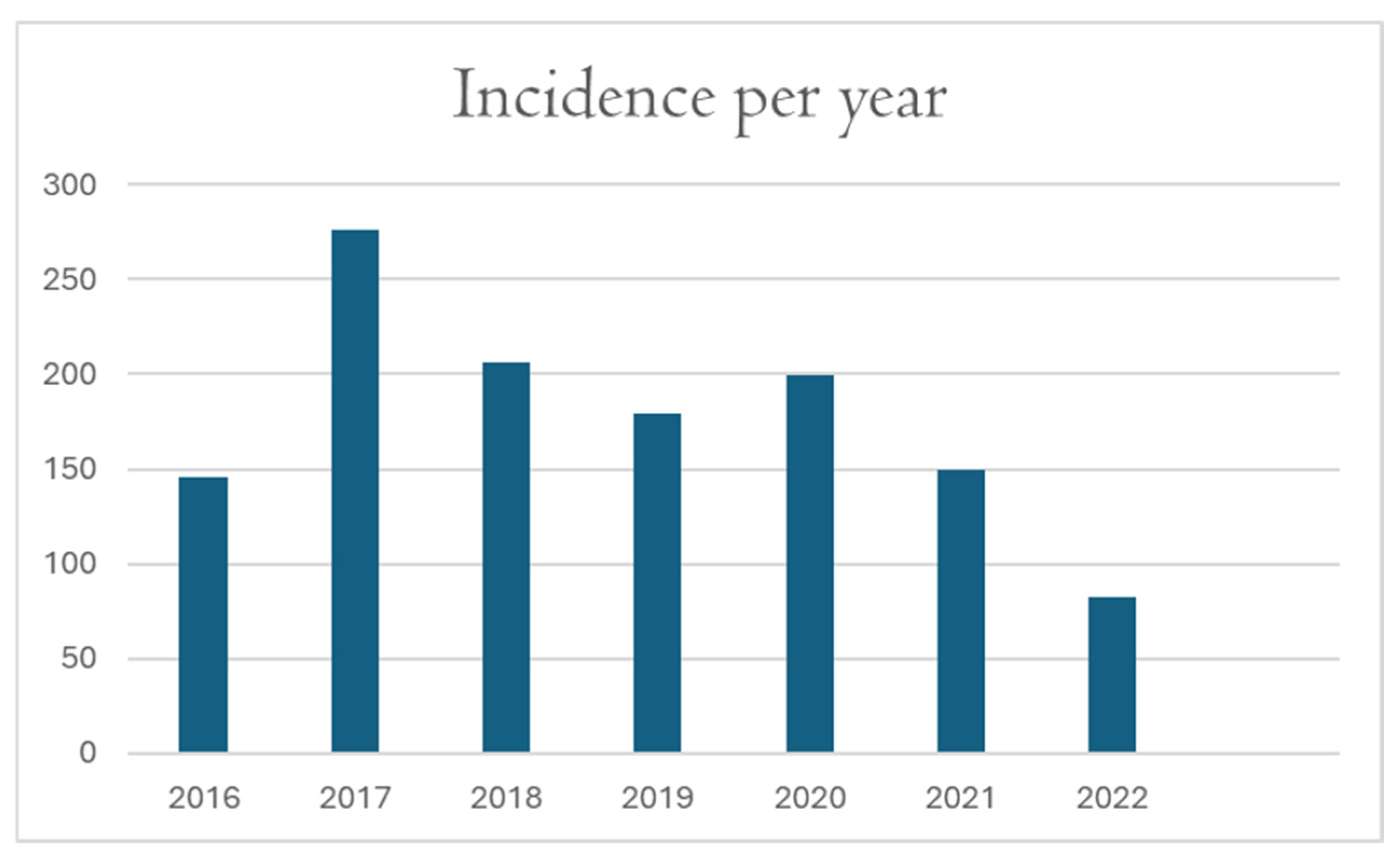

3.8. Incidence per Year

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAP | Community-Acquired Pneumonia |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| KAMC | King Abdulaziz Medical City |

| KASCH | King Abdullah Specialized Children Hospital |

| KAIMRC | King Abdullah International Medical Research Center |

References

- Wang, H.; Naghavi, M.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; Coates, M.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarab, M.; Macrae, M.B.; Curtis, C.M. Atypical pneumonia. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2014, 20, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikura, Y.; Somekawa, K.; Manabe, T.; Horita, N.; Takahashi, H.; Higa, F.; Yatera, K.; Miyashita, N.; Imamura, Y.; Iwanaga, N.; et al. Aetiological agents of adult community-acquired pneumonia in Japan: Systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Islam, S.; Eva, I.; Zafar, S.; Yeasmin, D.; Afreen, K.; Hossain, M. Clinical Presentation and Severity Assessment of Community Acquired Pneumonia in Adults Admitted to a Teaching Hospital. Ibrahim Card. Med. J. 2021, 10, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, T.J. Community-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994, 18, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Perusis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pinkbook/hcp/table-of-contents/chapter-16-pertussis.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pert.html# (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Raeven, V.M.; Spoorenberg, S.M.; Boersma, W.G.; van de Garde, E.M.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Voorn, G.P.; Bos, W.J.W.; van Steenbergen, J.E.; Alkmaar Study Group; Ovidius Study Group; et al. Atypical aetiology in patients hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia is associated with age, gender and season; a data-analysis on four Dutch cohorts. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, H.W.; Tuazon, C. Atypical pneumonias. Med. Clin. N. Am. 1980, 64, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasi, F. Atypical pathogens and respiratory tract infections. Eur. Respir. J. 2004, 24, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindiyeh, M.; Carroll, K.C. Laboratory diagnosis of atypical pneumonia. Semin. Respir. Infect. 2000, 15, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, N.; Akaike, H.; Teranishi, H.; Ouchi, K.; Okimoto, N. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in adolescents and adults: Clinical findings, drug susceptibility, and therapeutic efficacy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 5181–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Jia, Y.; Lin, F.; Xu, J. The prevalence of respiratory pathogens in adults with community-acquired pneumonia in an outpatient cohort. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Fei, A. Atypical pathogen infection in community-acquired pneumonia. Biosci. Trends 2016, 10, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurashi, N.Y.; Al-Hamdan, A.; Ibrahim, E.M.; Al-Idrissi, H.Y.; Al-Bayari, T.H. Community acquired acute bacterial and atypical pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. Thorax 1992, 47, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Batool, S.; Almaghaslah, D.; Alqahtani, A.; Almanasef, M.; Alasmari, M.; Vasudevan, R.; Attique, S.; Riaz, F. Aetiology and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates in community acquired pneumonia patients at Asir region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e13667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramegna, A.; Sotgiu, G.; Di Pasquale, M.; Radovanovic, D.; Terraneo, S.; Reyes, L.F.; Vendrell, E.; Neves, J.; Menzella, F.; Blasi, F.; et al. Atypical pathogens in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia: A worldwide perspective. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zong, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.B.; Ye, H.; Lv, X.J. PCR versus serology for diagnosing Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Arfaatabar, M.; Aminharati, F.; Azimi, G.; Ashtari, A.; Pourbakhsh, S.A.; Masoorian, E.; Pourmand, M.R. High frequency of Mycoplasma pneumoniae among patients with atypical pneumonia in Tehran, Iran. Germs 2018, 8, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.F.; Finn, N.; White, P.; Hales, S.; Baker, M.G. Global Perspective of Legionella Infection in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchello, C.; Dale, A.P.; Thai, T.N.; Han, D.S.; Ebell, M.H. Prevalence of Atypical Pathogens in Patients With Cough and Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, S.; Nagata, N.; Ueda, Y.; Ikeuchi, N.; Akagi, T.; Harada, T.; Miyazaki, H.; Ushijima, S.; Aoyama, T.; Yoshida, Y.; et al. Study of factors related to recurrence within 30 days after pneumonia treatment for community-onset pneumonia. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 27, 1683–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Dong, W.; Yuan, S.; Chen, J.; Lin, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, L. Comparison of respiratory pathogens in children with community-acquired pneumonia before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, R.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, R.; Zheng, G.; Wu, X. The Epidemiology of Pathogens in Community-Acquired Pneumonia Among Children in Southwest China Before, During and After COVID-19 Non-pharmaceutical Interventions: A Cross-Sectional Study. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2024, 18, e13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shabbir, A.; Abdullah, H.H.; Anayat, N.; Khan, A.A.; Mughal, H.M.I.; Usama, A. Predictors of mortality in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: A retrospective analysis identifying prognostic indicators for CAP mortality. Dev. Med. Life Sci. 2025, 2, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theilacker, C.; Sprenger, R.; Leverkus, F.; Walker, J.; Häckl, D.; von Eiff, C.; Schiffner-Rohe, J. Population-based incidence and mortality of community-acquired pneumonia in Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cillóniz, C.; Liapikou, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; García-Vidal, C.; Gabarrús, A.; Ceccato, A.; Magdaleno, D.; Mensa, J.; Marco, F.; Torres, A. Twenty-year trend in mortality among hospitalized patients with pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Age Group | (n) |

|---|---|

| 0–2 years | 9 |

| 2–5 years | 10 |

| 5–15 years | 21 |

| 15–20 years | 41 |

| 20–50 years | 135 |

| 50–80 years | 676 |

| More than 80 years | 346 |

| Total | 1238 |

| Organism | n. of Cases Tested | Positive Cases (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 808 | 14 | 1.73% |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | 808 | 3 | 0.37% |

| Bordetella parapertussis | 392 | 0 | 0 |

| Bordetella pertussis | 390 | 0 | 0 |

| Legionella pneumophila | 180 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Polish Respiratory Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almufleh, A.; Altuwayjiri, A.; Alshehri, A.; Alzouman, A.; Alotaibi, A.; Alsaedy, A. Comparison of Typical and Atypical Community Acquired Pneumonia Cases in Hospitalized Patients in Two Tertiary Centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060058

Almufleh A, Altuwayjiri A, Alshehri A, Alzouman A, Alotaibi A, Alsaedy A. Comparison of Typical and Atypical Community Acquired Pneumonia Cases in Hospitalized Patients in Two Tertiary Centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 2025; 93(6):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060058

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmufleh, Abdullah, Abdulrahman Altuwayjiri, Abdulmalik Alshehri, Abdulaziz Alzouman, Abdulhadi Alotaibi, and Abdulrahman Alsaedy. 2025. "Comparison of Typical and Atypical Community Acquired Pneumonia Cases in Hospitalized Patients in Two Tertiary Centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia" Advances in Respiratory Medicine 93, no. 6: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060058

APA StyleAlmufleh, A., Altuwayjiri, A., Alshehri, A., Alzouman, A., Alotaibi, A., & Alsaedy, A. (2025). Comparison of Typical and Atypical Community Acquired Pneumonia Cases in Hospitalized Patients in Two Tertiary Centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Advances in Respiratory Medicine, 93(6), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060058