1. Introduction

Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction (MAKE) is an established research field at the intersection of data-driven learning and knowledge-centric reasoning, which forms a methodological foundation for Artificial Intelligence (AI).

While machine learning (ML) uncovers statistical patterns in data, knowledge extraction helps transform these patterns into structured, interpretable, and actionable knowledge in the physical world. MAKE therefore bridges data-driven modelling and knowledge discovery, advancing explainable, trustworthy, and sustainable AI.

Machine learning serving as the algorithmic workhorse of AI, enabling computational systems to learn from data without being explicitly programmed, has a well-established and extensive historical development [

1,

2,

3], and ML has become a central driver of fundamental scientific progress.

Research in MAKE has also entered a new phase in which AI acts as an active research collaborator [

4].

In scientific machine learning (SciML) [

5], AI is tightly integrated into the scientific process, accelerating discovery in domain-specific applications across agriculture, biology, climate research, forestry, engineering, medicine, physics, and many more. MAKE thus supports a research ecosystem in which human expertise and AI systems co-evolve. Traditional priorities remain central, including interpretability [

6,

7], trustworthy and responsible AI [

8,

9], incorporation of prior knowledge [

10], causal reasoning [

11], and fairness [

12]. However, these goals must now be reassessed in the context of AI agents [

13] and foundation models [

14], which introduce new opportunities and risks. This dynamic landscape calls for a timely re-evaluation of the research priorities originally defined when MAKE first emerged as a field.

In this article, we revisit and expand the original MAKE topics [

15]. These were structured around seven thematic areas that together captured the full spectrum of machine learning and knowledge extraction nearly a decade ago: First, the data area focused on preprocessing, integration, mapping, and fusion, emphasising a deep understanding of the physical nature of raw data and the broader data ecosystem within specific application domains. The Learning area addressed algorithms across all facets, from design and development to experimentation and evaluation, both in general and domain-specific contexts. Visualisation centred on the challenge of translating results from high-dimensional spaces into human-perceivable forms, acknowledging that every analytical pipeline ultimately served a human interpreter with perceptual limits. The Privacy area highlighted data protection, safety, and security, reflecting growing global regulatory demands and the need for privacy-aware machine learning approaches such as federated learning and glass-box models, always grounded in usability and societal acceptance. Network Science introduced graph-based data mining, using graph theory to represent complex data structures and to uncover relationships using statistical, graph-theoretic, and ML techniques. Topology-focused data mining, especially homology and persistence, integrates with machine learning and shows significant potential for addressing practical problems. Finally, the Entropy area is centred on entropy-based data mining, leveraging entropy as a measure of uncertainty and linking theoretical and applied information science, for example, through metrics such as the Kullback–Leibler divergence.

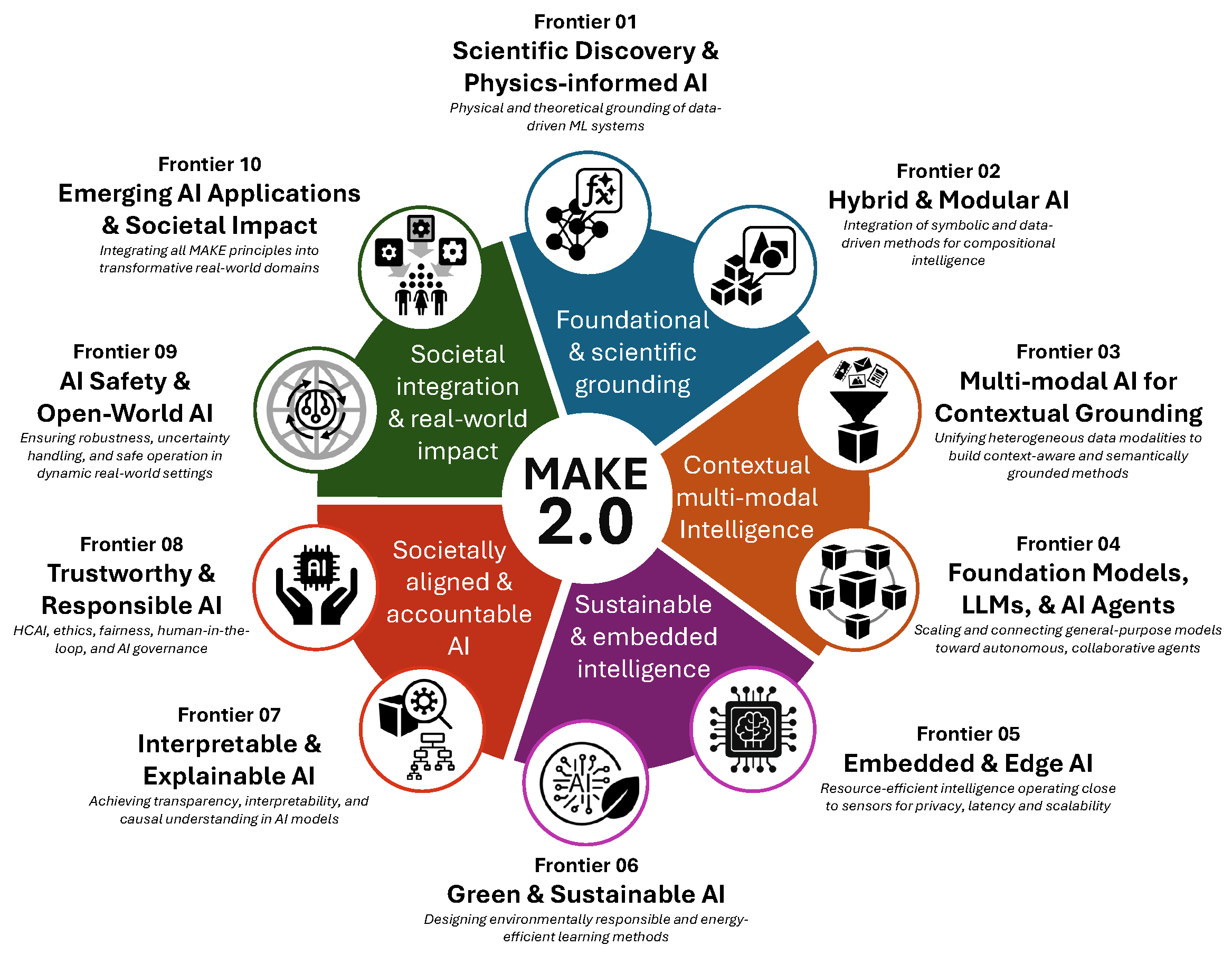

Our research agenda is organised around ten interrelated Frontier areas illustrated in

Figure 1, ordered from low-level to high-level:

Frontier 01: Scientific Discovery and Physics-informed AI (physical and theoretical grounding of data-driven learning systems)

Frontier 02: Hybrid and Modular AI (integration of symbolic and data-driven methods, bridging structured reasoning with data-driven learning for compositional intelligence)

Frontier 03: Multi-modal AI for Contextual Grounding (unifying heterogeneous data modalities to build context-aware and semantically grounded methods)

Frontier 04: Foundation Models, LLMs, and AI Agents (scaling and connecting general-purpose models toward autonomous, collaborative agents)

Frontier 05: Embedded and Edge AI (resource-efficient intelligence operating close to sensors, including federated learning and real-world environments)

Frontier 06: Green and Sustainable AI (designing environmentally responsible and energy-efficient AI methods)

Frontier 07: Interpretable and Explainable AI (achieving transparency, interpretability, and causal understanding in models)

Frontier 08: Trustworthy and Responsible AI (including Human-Centred AI, embedding ethics, fairness, human-in-the-loop, and human oversight into method design and governance)

Frontier 09: AI Safety and Open-World AI (ensuring robustness, uncertainty handling, and safe operation in dynamic real-world settings)

Frontier 10: Emerging AI Applications and Societal Impact (integrating all MAKE principles into transformative real-world domains, including agriculture, biology, climate, disaster management, economy, forestry, geology, health, industry, law, manufacturing, nutrition, oceanography, physics, robotics, safety, telecommunications, urban systems, veterinary science, water management, and zoology, among others)

Each Frontier constitutes a fundamental dimension of the evolving MAKE landscape, spanning the scientific and computational foundations of AI to its broader societal implications and transformative applications. Collectively, these Frontiers delineate a coherent and holistic research trajectory that integrates knowledge extraction with interpretability, sustainability, and human-centred responsibility.

The following sections explore each Frontier in detail, situating it within its historical context, identifying current challenges, and highlighting emerging trends and promising directions for future research.

2. Frontier 01: Scientific Discovery and Physics-Informed AI

Physics-informed AI has emerged as a response to the limitations of purely data-driven methods, which often struggle in domains where data are sparse, noisy, or insufficient to capture underlying physical mechanisms. Traditional ML models, while effective at pattern recognition, typically operate as black boxes: they infer correlations without understanding causality or adhering to known physical laws. This can result in poor generalisation, unreliable predictions, and limited insight into the phenomena being modelled.

Physics-informed AI addresses these challenges by embedding physical laws, conservation principles, and structural priors directly into learning architectures. This integration improves model robustness and interpretability and also opens new avenues for scientific discovery.

By constraining models with domain knowledge, researchers can explore regimes where data alone would be insufficient, validate theoretical hypotheses, and even uncover previously unknown relationships.

An illustrative example arises in climate modelling, where predicting ocean currents or atmospheric dynamics requires understanding complex interactions governed by fluid mechanics and thermodynamics. A purely data-driven model might struggle to extrapolate beyond observed conditions. However, a Physics-informed neural network that incorporates the Navier-Stokes equations and energy conservation laws can simulate these systems more accurately and reveal emergent behaviours (such as tipping points or feedback loops) that may not be evident from data alone. This capability transforms AI from a passive tool of approximation to an active partner in scientific exploration.

Thus, this first research frontier represents a shift from opaque, correlation-based learning to transparent, mechanism-aware AI, enabling better performance and alignment with real-world dynamics, as well as the generation of new scientific knowledge. Physics-informed AI empowers researchers to ask deeper questions, test theoretical models, and accelerate innovation across disciplines ranging from materials science to astrophysics.

2.1. Origins and Evolution

The origins of scientific and physics-informed AI lie at the intersection of classical numerical modelling and the rapid progress of modern ML. Traditional scientific computing has long relied on mechanistic models, typically expressed as systems of Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), to describe physical, biological, and engineering processes. Numerical techniques, such as finite element and spectral methods, have enabled large-scale simulations. However, their computational cost has often limited their applicability in real-time or high-dimensional settings.

In parallel, ML has advanced rapidly in fields such as computer vision and natural language processing, where deep neural networks achieved unprecedented predictive performance but remained largely correlation-driven and detached from physical principles [

3]. The integration of physics with ML gained momentum in the 2010s, when researchers recognised the need to embed prior scientific knowledge into data-driven architectures to improve generalisation, data efficiency, and trustworthiness. A landmark development was the introduction of physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), which demonstrated how physical laws expressed as PDEs could be incorporated directly into neural network loss functions. This approach revealed that incorporating conservation laws and boundary conditions can guide training, yielding solutions that remain faithful to the underlying dynamics even when data are scarce or noisy. Building on these ideas, the field has evolved toward more general frameworks, such as neural operators and operator learning, that aim to approximate mappings between function spaces rather than individual solutions to equations.

These advances extend the reach of scientific ML to problems involving parametric families of PDEs, enabling the creation of fast surrogates for large-scale simulations in climate science, fluid dynamics, and material modelling. At the same time, methods for uncertainty quantification and probabilistic scientific ML have emerged, combining Bayesian inference with physical priors to produce accurate, well-calibrated and thereby reliable predictions [

16]. The trajectory of this evolution reflects a broader paradigm shift: moving away from black-box predictors that maximise short-term accuracy toward mechanistic AI systems that embed the invariants, symmetries, and constraints of the natural world. Scientific and physics-informed ML thus represents the convergence of two traditions (data-driven learning and mechanistic modelling) into a unified framework that aspires to transform both AI research and the practice of science.

2.2. Problem

The central problem in this frontier area is that modern ML systems remain largely pattern-driven and insufficiently grounded in scientific knowledge. Most contemporary models rely on gradient-based optimisation to fit flexible function approximators to data (for example, deep neural networks). Although powerful, this learning approach is fundamentally statistical: it excels at capturing correlations and patterns in the training distribution. Still, it lacks a causal understanding of the underlying mechanisms that generate the data. As a result, these models often struggle with:

Distributional shifts: When deployed in environments that differ from the training data, predictions can become unreliable.

Physical implausibility: Without constraints from known laws, models may produce outputs that violate conservation principles or other scientific truths.

Limited interpretability: The lack of mechanistic grounding makes it difficult to explain or trust model behaviour, especially in domains subject to high-risk decisions.

These shortcomings are particularly problematic in critical scientific and engineering applications, such as climate modelling, ecosystem management, biomedical research, and materials design. In these domains, trust, generalisation, and physical consistency are essential. In such contexts, purely data-driven models may fail to support hypothesis testing, theory validation, or the generation of new insights.

To address this, the field is moving toward hybrid models that integrate mechanistic knowledge with statistical learning. Physics-informed AI exemplifies this approach by embedding differential equations, conservation laws, and domain-specific priors into learning architectures. This improves robustness and generalisation, and also transforms AI into a tool for scientific discovery, capable of revealing hidden structures, suggesting new theories, and guiding experimental design.

In short, the problem steps beyond technicalities: it is essentially epistemological. Without obeying the principles that govern the natural world, AI remains limited in its ability to contribute meaningfully to science. Bridging this gap is essential for building models that are accurate, explanatory, trustworthy, and discovery-enabling.

2.3. Why Is It a Problem?

Traditional data-driven models are fundamentally limited by their inability to guarantee physically valid or scientifically consistent outcomes. These models learn statistical patterns from data, but without explicit constraints, they can produce outputs that violate well-established physical laws. For example, a neural network trained to predict climate variables might generate temperature or pressure fields that violate conservation of mass or energy, rendering the predictions implausible and potentially misleading for scientific decisions. Similarly, in engineering applications, classifiers or regressors may perform well under nominal conditions but fail catastrophically when exposed to out-of-distribution scenarios, such as extreme loads or rare failure modes. Because these edge cases are often under-represented in training data, the model’s behaviour becomes unpredictable, leading to unsafe or unreliable recommendations.

The lack of principled uncertainty quantification further compounds these issues. Without calibrated confidence estimates, decision-makers cannot assess the reliability of AI outputs, especially in high-stakes domains where errors carry significant consequences. This undermines trust and limits the adoption of AI in scientific and industrial settings.

Moreover, real-world systems are inherently multi-scale and partially observed. They involve interactions across multiple spatial and temporal scales and often involve incomplete or noisy measurements. Capturing such complexity requires models that can incorporate prior knowledge, reason under uncertainty, and generalise beyond the observed data. Current data-driven approaches rarely achieve this level of robustness or expressiveness.

2.4. How Can It Be Tackled? Emerging Trends

Recent developments in scientific AI are converging around the need to embed domain knowledge directly into learning systems, moving beyond purely data-driven approaches. One of the most prominent trends is the use of physics-informed neural networks and neural operators, which incorporate governing equations, conservation laws, and symmetries into the training process. These models do not merely fit data. Instead, they are constrained to produce outputs that adhere to physical principles, even in regions with sparse or noisy data. Neural operators extend this idea by learning mappings between function spaces, enabling fast and generalizable solutions to families of partial differential equations. This is particularly valuable in fields such as fluid dynamics, electromagnetism, and climate modelling, where traditional solvers are computationally expensive and data alone are insufficient to capture the full complexity of the system.

Another important direction is the integration of differentiable simulators and hybrid modelling frameworks, which combine mechanistic models with data-driven components. Differentiable simulators enable physical models to be embedded in gradient-based learning pipelines, allowing refinement of simulations using observational data. Hybrid approaches, meanwhile, pair classical numerical solvers with neural surrogates that approximate computationally expensive evaluations, significantly accelerating simulations while maintaining fidelity to physical laws. These methods are increasingly used in engineering, robotics, and materials science, where real-time performance and physical accuracy are both critical. Alongside these developments, uncertainty quantification is gaining attention as a foundational requirement for trustworthy AI. Techniques such as Bayesian deep learning, ensemble modelling, and conformal prediction are being employed to provide calibrated confidence estimates, helping practitioners assess the reliability of predictions and make informed decisions under uncertainty.

A third emerging area focuses on interpretable scientific modelling using techniques such as symbolic regression and sparse identification of nonlinear dynamics (SINDy). These methods aim to rediscover governing equations from data, yielding compact, human-readable models that resonate with scientific intuition. Rather than producing opaque black-box outputs, these approaches generate symbolic expressions that can be analysed, validated, and potentially generalised across systems. This is particularly promising for domains where theoretical models are incomplete or where empirical observations suggest new dynamics. In parallel, researchers are developing architectures capable of handling multi-scale and partially observed systems, which are common in real-world applications. These models incorporate hierarchical structures, latent representations, and physics-informed priors to capture interactions across spatial and temporal scales, even when data is incomplete or noisy.

2.5. Desiderata

Progress in this frontier will require the development of AI systems that are physically consistent, meaning they must respect known scientific laws and constraints across all stages of learning and inference. This includes embedding conservation principles, symmetries, and governing equations into model architectures, ensuring that outputs remain plausible even in extrapolative or data-scarce regimes. Physical consistency is a prerequisite for trusting models in domains where violations of known laws can lead to misleading conclusions or unsafe decisions. At the same time, these systems must retain the flexibility to learn from complex, noisy, and incomplete data, allowing them to adapt to real-world conditions where idealised assumptions often break down.

Equally important are interpretability and uncertainty quantification. Models should produce outputs that are accurate and explainable in terms of underlying mechanisms or governing principles. Interpretability enables domain experts to validate predictions, trace errors, and build confidence in the system’s reasoning.

Alongside interpretability, robust uncertainty estimates are essential. These estimates must be reliable and actionable to inform and prioritise scientific trials. Techniques that provide calibrated confidence intervals, probabilistic forecasts, or bounds on model error will be central to this capability.

Scalability and auditability are also critical. Scientific AI systems must operate across multiple spatial and temporal scales, from microscopic interactions to system-level dynamics, and integrate multi-fidelity data sources, including simulations, experiments, and observational datasets. This demands architectures that can generalise across regimes and reconcile heterogeneous inputs. Moreover, these systems must be auditable and reproducible, allowing researchers to trace predictions back to the data and assumptions that generated them. Transparency in model design, training and inference procedures is vital for scientific rigour and verifiable progress.

Finally, efficiency and sustainability in both training and deployment must be prioritised, given the growing environmental and computational costs associated with large-scale AI. Models that are resource-aware and optimised for performance without excessive overhead will be better suited for widespread adoption in scientific practice.

2.6. Application Benefits

The potential benefits of scientific and physics-informed machine learning (ML) span a wide range of domains where physical consistency, interpretability, and robustness are essential. In forestry and agriculture, physics-informed digital twins are being developed to simulate ecosystem responses to interventions such as thinning, irrigation, or species-mix strategies. These models can incorporate hydrological cycles, soil dynamics, and plant physiology to predict outcomes under drought or climate stress, offering decision-makers reliable tools for sustainable land management. Unlike purely empirical models, these systems can generalise across regions and conditions, enabling proactive planning even in the face of uncertain environmental futures.

In climate science and geoscience, physics-informed models enable physically consistent projections of emission-reduction scenarios, land-use changes, and extreme weather events. By embedding conservation laws and thermodynamic principles, these models can simulate long-term dynamics with greater fidelity, helping policymakers evaluate the consequences of mitigation strategies and adaptation plans. Similarly, in medicine, integrating mechanistic physiological models with ML enables personalised treatment planning that respects biological constraints. For example, cardiovascular simulations informed by fluid dynamics and tissue mechanics can be combined with patient-specific data to assess risks, optimise interventions, and support clinical decision-making in a transparent and interpretable manner.

In robotics and engineering, the fusion of physical laws with data-driven learning enhances safety, reliability, and transferability. Models that incorporate dynamics, contact mechanics, and control constraints can support robust planning and sim-to-real transfer, reducing the gap between simulation and deployment. This is particularly valuable in autonomous systems, where failure to generalise across environments can lead to unsafe behaviour. More broadly, the adoption of scientific and physics-informed ML is redefining the role of AI, from a tool for predictive inference to a mechanism-aware collaborator in scientific exploration and decision support. By grounding learning in physical reality, these systems enable deeper insights, more reliable predictions, and a stronger foundation for innovation across disciplines.

2.7. Recent Advances and Road Ahead

Realizing the full potential of physics-informed ML requires a level of interdisciplinary collaboration that goes beyond current norms [

17]. Researchers from computer science, physics, engineering, mathematics, and the applied sciences must work together to co-design technically sound, scientifically meaningful models.

This includes developing shared benchmarks that reflect the complexity and constraints of real-world systems, as well as open datasets that are representative, multi-scale, and annotated with physical context. Reproducible protocols and transparent evaluation criteria are essential to ensure that progress is measurable and transferable across domains. Without these foundational elements, the field risks fragmentation and limited impact.

Equally important is the cultivation of interdisciplinary training and education. The next generation of researchers must be equipped to navigate both the theoretical foundations of scientific modelling and the practical tools of ML. This requires curricula that integrate physics, statistics, and computational methods, along with hands-on experience with real-world data and simulation environments. Training programs should emphasise technical proficiency jointly with scientific reasoning, interpretability, and ethical responsibility. By fostering a shared language and mindset across disciplines, these efforts can help bridge the gap between data-driven inference and mechanistic understanding.

Looking ahead, progress will also depend on fostering international collaborations, joint initiatives, and cross-community dialogue. The challenges addressed by scientific AI (including climate change, energy systems, healthcare, and infrastructure) are global in nature and require coordinated responses. Collaborative platforms that bring together academic institutions, industry, and public agencies can accelerate innovation and ensure solutions align with societal needs. The opportunity is significant and involves creating data-driven models that achieve high accuracy, while also explaining, supporting and guiding decisions in domains that matter most to society.

3. Frontier 02: Hybrid and Modular AI

The long-standing divide between symbolic reasoning and statistical learning has shaped the trajectory of AI research. Symbolic methods offer structure, interpretability, and logical guarantees, while statistical approaches excel in perception and large-scale pattern recognition. However, neither alone appears sufficient for building trustworthy, adaptive, and generalizable systems. Hybrid and modular AI emerges as a promising frontier by combining these complementary strengths within modular architectures. This integration aims to unite perception with reasoning, enabling AI systems that can both learn from data and adhere to rules, constraints, and human-understandable logic. In light of these facts, this second frontier aims at addressing one of the most pressing challenges in contemporary AI: bridging the gap between low-level statistical learning and high-level cognitive reasoning.

3.1. Origins and Evolution

Symbolic approaches dominated early AI research in the mid-20th century [

18], such as logic programming [

19,

20], knowledge bases, and rule-based expert systems [

21], initially employing monotonic logics. These methods emphasised explicit reasoning and interpretability [

22], yet suffered from brittleness and poor scalability in the face of uncertainty and noisy data. In parallel, statistical and connectionist approaches emerged, focusing on pattern recognition and probabilistic modelling.

The ‘AI winter’ [

23] periods highlighted the limitations of both paradigms when pursued in isolation. Although symbolic systems struggled with adaptability and learning, purely statistical models lacked transparency and the capacity to incorporate structured domain knowledge.

The resurgence of ML and its evolution into deep learning have driven remarkable progress in perception, language, and control [

24]. However, these systems remain largely opaque, data-hungry, and difficult to align with human reasoning [

25]. This has motivated renewed interest in hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of symbolic reasoning with the adaptability of statistical learning [

26,

27].

Current research directions include neurosymbolic integration, where neural networks handle perceptual tasks while symbolic modules provide reasoning, compositionality, and constraint enforcement [

28]. Modular AI architectures have also gained traction, with systems designed as modular components that can be combined, replaced, or fine-tuned for specific domains. These approaches address the growing demand for explainability, robustness, and generalisation across tasks, while aligning with cognitive theories of human problem-solving.

3.2. Problem

Modern ML systems have achieved impressive results in tasks like prediction and classification. However, they often operate as single, tightly connected units that are difficult to understand, modify, or trust. These systems tend to break down when faced with unfamiliar data and are challenging to evaluate or guide in real-world situations.

In contrast, systems based on structured logic offer clear rules, traceable decision paths, and reliable behaviour. However, they struggle with tasks that involve interpreting raw data, handling uncertainty, or scaling to complex environments. The central challenge is to bring together these two approaches (learning from data and reasoning with structure) into systems that are flexible, reliable, and easier to understand. This requires building systems from smaller, focused components that can be reused, adjusted, or combined as needed. Such modular designs support better generalisation, more precise explanations, and more control over behaviour.

The goal is to create systems that learn from experience while adhering to rules and making decisions that people can understand and trust. This means rethinking how we design and evaluate intelligent systems so they can work across different situations, adapt over time, and remain aligned with human values and expectations.

3.3. Why Is It a Problem?

One of the central challenges for hybrid and modular AI lies in the lack of compositional generalisation. End-to-end neural models often cannot recombine previously learned components in novel ways, limiting their systematicity and adaptability. This is particularly problematic in dynamic environments, where new situations require flexible reuse of existing knowledge.

A second limitation is the gap in explainability and verification. Black-box supervised predictors and knowledge-extraction self-supervised networks, while powerful, offer only limited auditability, and formal guarantees are scarce. This hinders their deployment in safety-critical or highly regulated domains, where accountability and certification are prerequisites. Moreover, current statistical models frequently hallucinate facts and struggle with discrete, multi-step reasoning tasks. They struggle to adhere to symbolic constraints or to plan reliably over long horizons, resulting in fragile performance outside narrow benchmarks.

Updating these monolithic systems is also problematic: incorporating new rules, ontologies, or regulations often demands costly retraining and carries the risk of catastrophic interference. These shortcomings are particularly evident in application domains. In forestry and agriculture, AI systems must adhere to management rules, safety requirements, and ecological thresholds. In healthcare, predictive models must integrate clinical guidelines, terminologies, and care pathways. In engineering or robotics, plans must remain compatible with both logical and physical constraints. In neuroscience, inference must be plausible following fundamental brain dynamics. Without hybrid and modular integration, meeting such requirements is challenging.

3.4. How Can It Be Tackled? Emerging Trends

Emerging research directions suggest multiple strategies to address these limitations. One promising approach is neuro-symbolic integration, which combines differentiable logic layers and constraint-driven learning with neural architectures.

Developments in neural theorem proving, inductive logic programming with neural components, and probabilistic soft logic or Markov logic hybrids exemplify how symbolic and statistical reasoning can be merged. A complementary direction focuses on modular architectures, such as mixture-of-experts models, tool-use orchestration, and program-of-thought frameworks, in which large language models act as controllers that delegate subtasks to symbolic solvers, planners, or external databases.

Another trend involves knowledge-grounded learning through retrieval-augmented pipelines that leverage ontologies and knowledge graphs. This is supported by schema- and type-aware prompting, as well as symbolic memory and domain-specific languages, which provide explicit task guidance. Program synthesis is also gaining traction, with neuro-guided methods generating executable code or queries, often in synergy with symbolic planning frameworks such as PDDL, hierarchical task networks, or SAT/SMT/ASP solvers. Alongside these developments, verification and monitoring techniques are being explored to enforce correctness at runtime. Formal methods, such as model checking and SMT solving, can be integrated with property-based testing and runtime contracts to ensure compliance with safety and regulatory requirements.

Ultimately, research into uncertainty-aware reasoning, including defeasible reasoning with non-monotonic logics, can focus on the integration of probabilistic programming and Bayesian inference with logical constraints for inference under uncertainty, whereas conformal prediction yields calibrated outputs that retain validity even when combined with symbolic rules.

3.5. Desiderata

Realising the long-term vision for hybrid and modular AI systems demands a well-defined set of desiderata. Foremost among these is composability, namely, the ability to seamlessly integrate modules for perception, memory, reasoning, and planning through standardised interfaces, typed inputs and outputs, and explicit contractual specifications. Neurosymbolic architectures must support modular integration of neural components (including perception, embeddings, pattern recognition) with symbolic modules (including logic, planning, knowledge representation). This demands well-defined interfaces, typed inputs and outputs, and formal specifications that enable flexible composition and interoperability across heterogeneous subsystems.

Equally critical is verifiability. AI systems must support checkable constraints, testable specifications, and formal guarantees for safety and correctness, particularly in high-stakes applications. To foster trust, systems should provide faithful, human-readable explanations, including transparent traces of reasoning, rule activations, and plan-generation steps. Provenance information must be embedded to ensure decisions are auditable and accountable.

Data efficiency and robustness can be enhanced by using symbolic priors, structured ontologies, and rule-based reasoning. These elements facilitate transfer learning across domains and bolster resilience against distributional shifts. Moreover, hybrid systems must support lifelong maintainability, allowing incremental updates to knowledge bases and modules without incurring costly retraining or catastrophic forgetting. Effective versioning and governance mechanisms will be essential for adapting to evolving requirements and ensuring system integrity over time.

Finally, achieving scalable performance will require efficient orchestration of large knowledge repositories and tool integrations, alongside hardware-aware design principles that minimise energy consumption and preserve real-time responsiveness.

3.6. Application Benefits

The successful realisation of hybrid and modular AI is expected to bring substantial benefits across science and industry. First, trustworthy AI would become a reality, as verifiable constraint satisfaction and transparent reasoning could accelerate certification processes and regulatory acceptance.

Second, modularity allows faster adaptation, since new rule sets or ontologies could be incorporated without destabilising perception models or retraining entire systems. The domain-specific impact would be considerable. In forestry and agriculture, AI systems could combine perception models for species identification or crop health monitoring with policy rules and ecological constraints, delivering decision support that is both compliant and sustainable. In healthcare, predictive models can be grounded in established guidelines and ontologies, providing recommendations that adhere to medical standards and build clinician trust. In engineering and robotics, modular planner–solver stacks can ensure that tasks are executed within both logical and physical constraints, thereby enhancing safety and reliability. These benefits would also reduce costs and risk, since module-level verification, targeted retraining, and contract testing can significantly lower integration debt and operational hazards. Finally, generalisation would improve: compositional reuse of knowledge, rules, and skills across tasks enables better out-of-distribution performance and supports robust reasoning over longer horizons. Altogether, hybrid and modular AI represents a crucial step toward AI systems that are reliable, interpretable, and adaptable across diverse application domains.

3.7. Recent Advances and Road Ahead

Hybrid modular AI (especially in its neurosymbolic form) offers a promising path beyond the limitations of purely symbolic or purely statistical approaches. By combining the capabilities of neural networks with the structure and interpretability of symbolic reasoning, this paradigm enables systems that are both perceptually grounded and logically coherent. Realising this vision will require a genuinely interdisciplinary effort. Researchers from ML, cognitive science, formal logic, software engineering, and knowledge representation must work together, bridging methodological divides and aligning on shared goals. This frontier calls for a cultural shift toward open research practices, interoperability across tools and frameworks, and a collaborative mindset that values transparency, modularity, and reproducibility. Looking ahead, neurosymbolic hybrid AI is likely to become a central paradigm for building trustworthy, generalizable, and adaptable systems. Key directions for future research include:

Scalable integration of symbolic knowledge into large-scale neural architectures, enabling structured reasoning over learned representations.

Modular frameworks that support reusability, composability, and domain adaptation, allowing components to be flexibly assembled and updated.

Embedded formal reasoning and verification capabilities within statistical models, ensuring reliability and interpretability in complex decision-making.

Progress in these areas could lead to AI systems that learn efficiently from limited data, reason under uncertainty using non-monotonic logic, and transfer knowledge across modalities and contexts. Ultimately, hybrid and modular AI aims to bridge the gap between low-level perception and high-level cognition, laying the foundation for systems that are both scalable and semantically rich.

4. Frontier 03: Multi-Modal AI for Contextual Grounding

This frontier research area calls for a shift in research focus: from isolated modality-specific models to multi-modal MAKE systems that can handle and integrate data across modalities, scales, and tasks while respecting physical constraints and domain knowledge. Only through such grounding can AI systems answer executable queries, provide trustworthy explanations, and adapt gracefully to incomplete, conflicting, or evolving inputs. At stake is the transition from fragile perception pipelines to robust and modular world-understanding engines that underpin critical applications in agriculture, climate science, healthcare, robotics, and beyond. The promise of multi-modal MAKE lies in enhanced data-driven modelling robustness and in enabling AI to bridge perception and reasoning: reducing hallucinations, aligning outputs with real-world constraints, and accelerating trustworthy human–AI collaboration.

4.1. Origins and Evolution

AI has made significant strides in single-modality domains, achieving state-of-the-art performance in areas such as natural language processing (NLP) [

29], computational linguistics [

30], conversational agents [

31], speech recognition [

32], and especially large language models [

33]. Similarly, breakthroughs in computer vision [

34], time series analysis [

35], and graph-based learning [

36] have demonstrated the power of specialised models tailored to specific data types.

However, the real world is inherently multi-modal. Complex environments and tasks often involve diverse streams of information that must be interpreted jointly. For instance, understanding a forest ecosystem may require integrating LiDAR point clouds, satellite imagery, weather simulations, and field reports. In healthcare, a patient’s condition is represented through medical images, lab results, physiological time series, and clinical notes. Similarly, a robot’s situational awareness emerges from visual input, tactile feedback, and natural language instructions [

37].

To operate effectively in such settings, AI systems must move beyond narrow pattern recognition and embrace contextual grounding, that means, the ability to fuse heterogeneous data sources into coherent, semantically rich world models [

38]. This shift marks a transition from modality-specific intelligence to systems capable of holistic understanding, where meaning is derived not just from isolated signals but from their interplay within a broader context.

4.2. Problem

Real-world decision-making requires that AI systems ground their internal representations in diverse, heterogeneous modalities, including text, images, audio, video, point clouds, time series, graphs, geospatial layers, and other sensor streams. These modalities often vary in structure, resolution, and temporal dynamics, yet must be interpreted in a unified, semantically coherent manner.

The central challenge lies in moving beyond isolated, single-modality pattern recognition toward context-aware, cross-modal world understanding. This involves not only aligning and integrating information across modalities, but also maintaining semantic consistency across different contexts, timescales, and tasks. Such grounding is essential for enabling AI systems to query, reason, and act effectively in complex, dynamic environments, whether interpreting a medical diagnosis, navigating a physical space, or responding to multimodal human inputs.

4.3. Why Is It a Problem?

The development of multimodal AI faces several persistent challenges. Single-modality systems inevitably suffer from fragmented perception, since they miss the complementary evidence that arises when different data streams are combined. For instance, imagery provides spatial detail, LiDAR provides three-dimensional structure, and text provides semantic context. Even when multiple modalities are considered, their alignment can be weak. Cross-modal mappings are often spurious, and models may hallucinate outputs when modalities disagree or when one of them is missing. Temporal and spatial incoherence further complicates this issue. Sensors operate asynchronously, data are sampled at irregular intervals, and real-world phenomena evolve across multiple scales, all of which disrupt conventional fusion pipelines. Limited grounding also hampers performance: many systems can map tokens to pixels but fail to account for units, ontologies, or operational constraints, resulting in semantically shallow outputs. Uncertainty is another blind spot. Few models offer calibrated confidence estimates or handle modality dropout and distribution shifts in a principled way, making them fragile in practice. Finally, the maintenance burden is considerable. Updating taxonomies, integrating new sensors, or revising schemas in monolithic end-to-end models is costly and often infeasible, restricting the adaptability of current systems.

4.4. How Can It Be Tackled? Emerging Trends

Several emerging trends point to promising solutions for achieving contextual reasoning capabilities on multimodal data. To begin with, self-supervised cross-modal learning has become a cornerstone, leveraging contrastive and masked objectives to learn joint embeddings of text, vision, audio, and sensor data. These approaches can be further improved by curricula that adapt across scales and sampling rates. Advances in hierarchical fusion architectures are also critical, leveraging early and late fusion, cross-attention mechanisms, and gating across temporal and spatial hierarchies, often augmented with mixture-of-experts adapters to support the addition of new modalities. Grounding models with structure is another key direction. Knowledge graphs, schemas, and unit-aware layers constrain outputs with ontologies, ensuring semantic validity and interpretability. Tool-augmented models further expand this idea by orchestrating perception tools, such as detectors, segmentation algorithms, SLAM systems, and GIS frameworks, through planner–solver patterns and executable domain-specific languages.

In parallel, sequence world models integrate multi-rate sensors, temporal entity tracking, and counterfactual rollouts for reasoning about future scenarios, while advances in robustness and uncertainty quantification, including distributionally robust objectives, Bayesian methods, ensembles, and conformal prediction, provide calibrated reliability. These developments are supported by multimodal data engines for large-scale curation, weak and synthetic supervision, and active learning, often with experts in the loop to improve labelling efficiency.

4.5. Desiderata

Realising the full potential of multi-modal AI will require systems with a set of key properties. Contextual coherence is paramount: models must maintain consistent semantics across modalities, track entities over time, and correctly interpret measurement units and scales. They should also enable grounded reasoning, aligning predictions and actions with ontologies, constraints, and executable queries over structured knowledge. Reliability will be essential, with systems capable of providing calibrated uncertainty estimates, degrading gracefully when signals are missing or conflicting, and monitoring their own performance under distributional shifts. Composability represents another desideratum. Modular adapters for new sensors or knowledge bases, combined with typed interfaces and explicit contracts between modules, will allow systems to evolve over time. Efficiency and sustainability cannot be ignored. Multi-fidelity training strategies, edge-friendly inference, and energy-aware operation will ensure that these systems are viable at scale. Ultimately, governance is indispensable, requiring models that preserve data and knowledge provenance and versioning while ensuring privacy-preserving learning in sensitive domains.

4.6. Benefits

The benefits of multi-modal contextual AI span a wide range of domains. In forestry and agriculture, digital twins that fuse LiDAR point clouds, UAV imagery, weather data, soil sensors, and management texts can provide robust monitoring of species and forest health, deliver timely risk alerts, and support precise intervention planning [

39]. In climate science and environmental management, multi-sensor earth observation (integrating SAR, optical imagery, and meteorological data) combined with knowledge-grounded queries, offers policy-relevant assessments that are both timely and reliable. In healthcare, multi-modal systems that jointly reason over clinical text, medical images, and physiological signals can deliver uncertainty-calibrated, guideline-aware outputs, thereby increasing clinician trust and improving patient outcomes. Robotics and industry will also benefit from systems that integrate vision, depth, force, and language instructions to achieve more reliable manipulation, inspection, and control in complex environments. More generally, multi-modal AI bridges perception and reasoning, reduces hallucinations, and improves knowledge transfer across contexts.

4.7. Recent Advances and Road Ahead

This third frontier of AI is not about building ever larger models, but about building grounded models that can weave together the languages of pixels, words, waves, graphs, and sensors into a coherent understanding of the world we inhabit. Without a grounded contextualization of the knowledge captured by AI models from data, these models will not fully realise their potential, remain prone to hallucinations, and stay disconnected from the contexts in which humans live and act. With contextual grounding, AI can become a reliable partner in safeguarding ecosystems, advancing medicine, and enabling resilient industries.

Recent research is increasingly focused on developing architectures and mechanisms that support deep integration across modalities while preserving semantic alignment. Promising directions include concept alignment networks, which map representations across modalities into shared conceptual spaces, enabling coherent reasoning and retrieval. Probabilistic neural circuits allow the integration of symbolic structure with uncertainty-aware neural computation, supporting robust inference in noisy or incomplete environments. Other emerging approaches involve cross-modal transformers, multi-scale fusion mechanisms, and graph-based grounding frameworks that capture relational dependencies across modalities and time. These innovations are paving the way for AI systems that can build rich, context-sensitive world models, capable of understanding not just isolated signals, but the interconnected realities they represent.

The path ahead is ambitious, but the prize is clear: AI systems that no longer merely focus on pattern recognition but better understand, reason, and act in our multimodal world.

5. Frontier 04: Foundation Models, LLMs and AI Agents

The emergence of foundation models and large language models (LLMs) has reshaped the AI landscape, enabling systems that generalise across tasks, domains, and modalities with minimal supervision. These models serve as the backbone for increasingly capable AI agents that can perceive, reason, and act in open-ended environments. This frontier explores how foundation models are evolving from passive predictors into active agents, capable of interacting with tools, grounding their outputs in external knowledge, and adapting to dynamic contexts through memory, planning, and goal-directed behaviour.

5.1. Origins and Evolution

Large Language Models (LLMs) have rapidly evolved from pure text predictors into generalist problem-solvers that can plan, use tools, retrieve knowledge, and coordinate with humans and other agents [

40]. Building on these advances, AI agents and AI companions are emerging as new nonhuman ‘Lab members’ that assist with diverse tasks, including coding and text handling, interacting with robots [

41], and supporting domain experts even outside in the wild [

42]. This frontier marks a transition from static prompting toward agentic workflows that integrate memory, perception, action, and social interaction, while also addressing the challenges of safety, reliability, and responsible use.

Historically, LLMs were optimised for single-turn next-token prediction [

43] and were primarily evaluated against static benchmarks [

44]. Early systems were built on

n-gram models and probabilistic grammars, later enriched with distributed representations such as Word2Vec and GloVe, which capture semantic relationships in dense vector spaces. The rise of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) architectures enabled sequential modelling of arbitrary length, though they struggled with vanishing gradients and long-range dependencies. The Transformer architecture [

33] revolutionised this trajectory by introducing self-attention, allowing models to scale efficiently while capturing global contextual relationships. This breakthrough underpinned the emergence of large-scale pre-trained models such as BERT [

45] and GPT-3 [

46], which popularised the paradigm of pre-training on massive corpora followed by fine-tuning for downstream tasks.

As computational resources and data availability grew, LLMs rapidly scaled in size, producing qualitatively new capabilities. Emergent behaviours such as in-context learning, zero-shot reasoning, and few-shot adaptation appeared without being explicitly engineered. Present-day systems increasingly demonstrate chain-of-thought reasoning, retrieval-augmented generation, iterative self-correction, and tool integration, pushing them beyond passive prediction into interactive problem-solving. At the same time, multimodal extensions have expanded the reach of LLMs by integrating text with images, audio, and sensor data, enabling richer world modelling and perception-grounded reasoning. Retrieval augmentation and structured memory architectures have further improved factual accuracy and reduced hallucinations.

The evolution of LLMs has been as much cultural as technical. Their integration into research, industry, and daily life has raised pressing debates about fairness, interpretability, and societal alignment. Ethical and governance challenges around bias, misinformation, and human oversight have become inseparable from technical progress. Today, LLMs are evolving into agentic systems equipped with memory, long-horizon planning, and autonomy, supported by preference alignment and deference mechanisms that keep them within the bounds of human intent. Looking forward, LLM-based agents will function as persistent collaborators embedded in scientific and industrial workflows, with grounded perception, trustworthy autonomy, and calibrated human oversight at their core. This trajectory reflects a broader shift from next-token predictors toward adaptive collaborators designed not only to extend human capability but also to do so safely, reliably, and socially aligned.

5.2. Problem

Despite their impressive capabilities, large language models (LLMs) and the agents built upon them remain fundamentally fragile. They frequently hallucinate facts, overgeneralize beyond their training distributions, and struggle with tasks that require long-horizon credit assignment, grounded world models, or verifiable execution. These limitations undermine their reliability in real-world applications, especially when precision, safety, or accountability are critical.

Moreover, agentic behaviour introduces new layers of complexity. Autonomous loops where agents perceive, plan, and act can amplify errors, propagate unsafe actions, or drift away from user intent. Without principled mechanisms for control, robust memory systems, and reliable governance over tool use and external interactions, these agents risk becoming unpredictable or misaligned. Addressing these challenges requires rethinking the foundations of agent design, moving toward architectures that are not only powerful but also interpretable, grounded, and verifiable.

5.3. Why Is It a Problem?

Unreliable behaviour in LLM-based agents poses serious risks across scientific, industrial, and societal domains. Inaccurate outputs, such as hallucinations or miscalibrated confidence, undermine scientific reproducibility, software reliability, and decision-making safety in open-world settings. Weak grounding and sparse feedback loops hinder robust planning and long-term reasoning, while opaque internal states make it difficult to audit decisions, provide recourse, or ensure regulatory compliance.

These challenges are further amplified in multi-agent environments, where coordination failures, emergent behaviours, and social biases can arise unpredictably. Without mechanisms for principled control, transparent memory systems, and trustworthy governance over tool use and external interactions, agents may drift from user intent, propagate errors, or act in ways that are difficult to certify or constrain. Addressing these issues is critical to building AI systems that are not only capable but also safe, accountable, and aligned with human values.

5.4. How Can It Be Tackled? Emerging Trends

Promising research directions for large language model agents are converging at the intersection of modelling, systems, and evaluation. One avenue is tool use and program synthesis, in which agents act as planners that can invoke external tools, write and execute code, and verify outputs. These capabilities are supported by constrained decoding and execution guards that limit unsafe actions and reduce the risk of cascading errors. Another active trend is retrieval-augmented and structured reasoning. Approaches such as ReAct-style reasoning–acting loops, graph-structured planning, and memory-augmented architectures allow agents to ground their reasoning in external knowledge and adapt dynamically to evolving tasks. Counterfactual and self-reflective updates further reduce error accumulation by enabling agents to reconsider past choices. Long-term memory and autonomy are also becoming essential, with episodic and semantic memory architectures, curriculum-based learning, and continual adaptation providing the foundation for sustained engagement with complex tasks. These mechanisms are reinforced by preference alignment and instruction tuning, which help maintain consistency with human intent over extended interactions. In addition, multi-agent collaboration is emerging as a powerful paradigm, where role-specialised agents such as research assistants, code generators, reviewers, and operations managers interact through negotiation, critique, and consensus protocols to achieve more reliable results. Safety remains paramount, and human-in-the-loop methods are being developed to incorporate uncertainty-aware deferral, interactive oversight, and red-teaming strategies. Sandboxed environments and formal checks on tool APIs add layer of protection. Finally, progress depends on robust benchmarking and diagnostics, with agent-centric benchmarks for tasks such as scientific discovery, software engineering, and embodied control, alongside reproducible harnesses and standardised logging frameworks to ensure accountability and comparability across systems.

5.5. Desiderata

Future LLM-based agents should embody several key properties to be both valuable and trustworthy. Transparent, inspectable reasoning traces are crucial, enabling humans to follow the logic of decisions and trace data provenance. Tool use must be verifiable, with execution constraints, typed interfaces, and comprehensive audit logs ensuring both correctness and accountability. Calibrated uncertainty estimates are needed to guide safe decision-making, complemented by deferral mechanisms and fallback behaviours that enable agents to pause or request oversight when risk is high. Grounded world models that integrate perception, simulation, and structured domain knowledge will be necessary for reliable reasoning beyond purely textual environments. Agents must also demonstrate competence in long-horizon planning, supported by memory, reflection, and goal-consistency mechanisms that prevent drift over time. Finally, social alignment will be essential in both multi-agent and companion settings, ensuring that agents respect principles of privacy, dignity, and consent when engaging with humans and one another.

5.6. Application Benefits

The successful realisation of these capabilities would yield transformative benefits. Research and engineering processes could be significantly accelerated by reliable, auditable AI co-workers that reduce repetitive work, propose alternative strategies, and provide continuous support across disciplines. Software and data quality would improve as test-driven agents automate documentation, enforce standards, and carry out continuous verification. Inclusive collaboration would also be enhanced, as LLM companions serve as accessible tutors, co-authors, and lab assistants, lowering barriers for learners and researchers across diverse contexts. Most importantly, autonomy could be deployed more safely, with agents that defer to humans when necessary, explain their reasoning, and comply with governance requirements. This combination of reliability, inclusivity, and safety positions LLM agents as central enablers of the next wave of human–AI collaboration.

5.7. Recent Advances and Road Ahead

Recent work demonstrates tool-augmented LLMs, reasoning-acting loops, self-reflection, and multi-agent collaboration, alongside agent-focused benchmarks in web interaction and software engineering. The road ahead requires unifying planning, memory, and verification under principled safety envelopes; standardising interfaces for tools, simulations, and data provenance; and establishing rigorous agent evaluations tied to domain outcomes. AI companions as lab members should be framed not as replacements, but as accountable collaborators that amplify human expertise under transparent governance.

To address these challenges, ongoing research is exploring how MAKE techniques can be used to minimise hallucinations and improve alignment through targeted interventions. Structured knowledge bases, retrieval-augmented generation, and concept-level grounding can help constrain model outputs and reduce factual errors. Techniques such as probabilistic reasoning, symbolic overlays, and fine-grained feedback mechanisms are being developed to support more reliable planning and execution. Additionally, ensuring the right to be forgotten, reducing toxicity, and enforcing value-sensitive constraints are becoming central goals in the design of responsible agents. Notably, LLM-based agents are also being used to analyse and critique other AI models, serving as foundational judges that can evaluate behaviour, detect biases, and propose corrections, ultimately opening new possibilities for self-regulating AI ecosystems.

6. Frontier 05: Embedded and Edge AI

As AI systems become increasingly pervasive, there is a growing need for intelligence that operates near data sources on distributed, resource-constrained, embedded devices in real-world environments. This frontier focuses on embedded and edge AI, where models are deployed directly on sensors, mobile devices, autonomous machines, and Internet of Things (IoT) nodes. These systems must function reliably under strict constraints on energy, memory, and compute, while supporting real-time decision-making, privacy preservation, and autonomy.

6.1. Origins and Evolution

Embedded AI refers to the design and deployment of intelligent systems that operate at the network edge, often in decentralised and resource-limited settings [

47,

48]. Unlike traditional cloud-based paradigms, embedded AI runs locally on devices such as drones, robots, wearables, smartphones, and sensors. This approach is critical for applications where low latency, privacy, and autonomy are non-negotiable, such as smart agriculture, environmental monitoring, healthcare diagnostics, autonomous vehicles, and industrial automation.

Historically, AI was centralised: large models were trained and executed on powerful servers, while edge devices were primarily passive data collectors. However, recent advances in model compression, quantisation, pruning, and efficient architectures such as MobileNets and TinyML have enabled real-time inference on resource-constrained devices, making edge devices intelligent [

49]. In parallel, federated learning has emerged as a decentralised training paradigm, allowing devices to collaboratively learn without sharing raw data, thereby addressing privacy and bandwidth limitations [

50]. The evolution of embedded AI is now moving toward systems that are not only efficient and autonomous but also capable of lifelong learning, contextual adaptation, and seamless integration with heterogeneous cloud infrastructures [

51].

6.2. Problem

Most state-of-the-art AI models are computationally intensive and energy-hungry, making them unsuitable for direct deployment on embedded platforms. Communication bottlenecks, intermittent connectivity, and privacy concerns further complicate the deployment of intelligent systems at the edge. Without efficient and scalable approaches, embedded AI risks being unreliable, non-adaptive, or overly dependent on centralised infrastructure. Moreover, the heterogeneity of edge environments demands models that can generalise across diverse contexts while remaining lightweight. Ensuring robustness, security, and real-time responsiveness under such constraints is a non-trivial task, mainly when devices must operate autonomously and collaboratively in dynamic settings.

6.3. Why Is It a Problem?

Several issues make embedded AI particularly challenging and distinguish it from conventional ML settings. Edge devices are inherently constrained by limited memory, compute power, and battery life, which restricts the complexity of models that can be deployed. Relying on centralised cloud processing exacerbates the problem by introducing latency, which is unacceptable in safety-critical tasks such as autonomous driving or medical monitoring, where split-second decisions are required. Privacy and security are also pressing concerns, since transmitting raw data to cloud servers increases the risk of breaches and misuse of sensitive information. The scalability challenge compounds these difficulties: a large number of interconnected devices operating simultaneously places enormous strain on bandwidth and energy infrastructures, creating bottlenecks for widespread deployment. Finally, robustness remains a persistent challenge, as embedded AI systems must operate reliably in uncontrolled environments where data streams are noisy, incomplete, or subject to adversarial manipulation.

6.4. How Can It Be Tackled? Emerging Trends

Emerging research is addressing these challenges through a diverse set of strategies. Model compression techniques, such as quantisation, pruning, and knowledge distillation, enable complex neural networks to be reduced into lightweight versions that can operate efficiently on resource-constrained devices. Purpose-built architectures like MobileNets and SqueezeNet exemplify this trend toward efficiency. Federated and decentralised learning provide another avenue by enabling devices to collaborate on model training without exchanging raw data, thereby preserving privacy while reducing bandwidth demands. Hardware-software co-design is also gaining momentum, driven by advances in neuromorphic computing, low-power AI accelerators, and embedded GPUs tailored for edge environments. On-device continual learning extends these efforts by enabling models to adapt incrementally over time without requiring full retraining. Privacy-preserving techniques, including differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, and homomorphic encryption, are being combined to create secure edge AI systems that protect sensitive information. Finally, hybrid edge–cloud orchestration offers a pragmatic solution that dynamically balances local computation and cloud resources to optimise latency, efficiency, and reliability.

6.5. Desiderata

Future embedded AI systems should embody several defining characteristics to be effective. Efficiency in computation, memory, and energy consumption is critical, ensuring that devices can operate sustainably in constrained environments. Privacy preservation requires integrating federated and encrypted learning mechanisms to prevent the leakage of sensitive information. Adaptability will also be key, with systems expected to support lifelong and transfer learning directly at the edge, enabling continuous improvement without reliance on large-scale retraining. Robustness must be built in, allowing models to withstand environmental noise, distribution shifts, and adversarial conditions. Interoperability across heterogeneous devices and platforms is essential to create flexible ecosystems that integrate seamlessly into broader infrastructures. Finally, autonomy should be prioritised, ensuring that embedded AI systems can make local decisions without requiring constant connectivity to external servers, which is particularly vital in remote or bandwidth-limited contexts.

6.6. Benefits

The realisation of embedded AI promises a wide array of benefits with far-reaching societal impact. Low-latency, real-time AI services would become feasible in critical applications, from continuous healthcare monitoring to autonomous vehicles, where rapid decision-making can save lives. By reducing dependence on centralised cloud infrastructure, embedded AI enables greater scalability for IoT and sensor networks, preventing these systems from overwhelming communication backbones. Enhanced data privacy will strengthen compliance with regulatory frameworks and foster user trust, particularly in domains involving personal or sensitive information. The emphasis on efficient computation and energy use will enable the sustainable deployment of AI across a large number of devices, reducing the environmental footprint of widespread adoption. Ultimately, embedded AI can democratise access to intelligence, enabling advanced services even in low-resource or remote environments, thereby narrowing global digital divides and ensuring more equitable access to AI’s benefits.

6.7. Recent Advances and Road Ahead

To overcome these limitations, research is increasingly focused on resource-aware learning, on-device adaptation, and privacy-preserving intelligence. Techniques such as neural architecture search for edge devices, energy-efficient training, and continual learning under constraints are being explored to make embedded AI more scalable and resilient. Recent advances include TinyML deployments, neural architecture search for efficient models, and scalable frameworks for federated learning, such as Google’s Federated Averaging. Hardware innovations, including edge TPUs, neuromorphic chips, and low-power AI accelerators, are reshaping the landscape. Federated learning is evolving to support heterogeneous data distributions, personalised models, and secure aggregation, enabling collaborative intelligence across distributed networks.

Looking ahead, the future of embedded and edge AI lies in building self-improving, context-aware systems. This includes developing mechanisms for local reasoning, on-device anomaly detection, and edge-to-cloud orchestration that balances autonomy with global coordination. The road ahead requires bridging gaps between algorithms, hardware, and systems. Research must prioritise unified frameworks that balance efficiency, robustness, and privacy. Future embedded AI will evolve into adaptive, collaborative ecosystems where edge devices not only infer but also learn in real time, contributing to a resilient and sustainable AI infrastructure.

7. Frontier 06: Green and Sustainable AI

As AI systems scale in size and influence, their environmental impact has come under increasing scrutiny. This frontier focuses on developing green, sustainable AI to reconcile the growing computational demands of modern models with the urgent need for ecological responsibility. The goal is to design AI methods, systems, and policies that minimise energy consumption, reduce carbon emissions, and promote sustainability, while still enabling innovation and progress.

7.1. Origins and Evolution

AI is a double-edged sword for sustainability. On one hand, AI can help optimise energy use, accelerate climate science, and enable sustainable resource management [

52]. On the other hand, the rapid growth of large-scale models and data centres has raised serious concerns about energy consumption [

53], carbon footprint [

54], and environmental sustainability [

55]. Green and sustainable AI aims to balance these tensions by designing methods, systems, and policies that reduce the ecological impact of AI while leveraging its power to foster environmental sustainability [

56,

57,

58].

In the past, efficiency was a secondary concern in AI, as research prioritised accuracy and model capacity. The rise of deep learning and large-scale foundation models, however, has made the environmental cost of training and deployment a pressing issue. At present, awareness of AI’s carbon footprint has grown, with tools emerging to measure energy use and frameworks advocating sustainable practices [

59]. The future envisions AI that is not only accurate and trustworthy but also resource-efficient, carbon-conscious, and explicitly aligned with the goals of the green transition and the UN Sustainable Development Goals [

60].

7.2. Problem

Modern AI models, particularly large-scale deep learning systems, require vast computational resources for training and deployment. This translates into significant electricity consumption and a growing carbon footprint. For example, training a single large language model can emit as much CO2 as several cars over their entire lifetimes. As AI adoption accelerates across industries, the cumulative environmental impact of data centres, model training, and inference pipelines is becoming a serious concern.

Without sustainable design principles, AI risks contributing to global energy demand and environmental degradation, undermining the very goals it could help achieve. The pursuit of ever-larger models without regard for efficiency exacerbates this issue, especially when performance gains are marginal compared to the ecological cost. Addressing this problem requires a shift in priorities from raw performance to resource-aware innovation, where energy efficiency, carbon accountability, and environmental impact are treated as first-class design objectives.

7.3. Why Is It a Problem?

The pursuit of ever-larger, more complex AI models has driven escalating energy demands that are increasingly unsustainable. Training state-of-the-art models often requires immense computational resources, consuming energy at a scale that is difficult to justify outside of a handful of wealthy institutions. This creates a growing inequity in the field, as resource-intensive AI development privileges elite organisations and exacerbates the digital divide, excluding smaller institutions, researchers in resource-constrained environments, and communities in the Global South.

Beyond energy consumption, AI systems carry a significant carbon footprint. Non-renewable energy sources frequently power data centres, and the environmental cost extends far beyond computation. The production and disposal of specialised hardware involve rare earth mineral extraction, manufacturing emissions, and e-waste challenges, adding hidden burdens across the entire supply chain. Most concerning is the contradiction that arises when AI is promoted as a solution to climate challenges while simultaneously contributing to environmental degradation. Without a fundamental rethinking of how AI is designed, trained, and deployed, the field risks undermining its own potential to support sustainability.

7.4. How Can It Be Tackled? Emerging Trends

Several promising trends are beginning to address AI’s sustainability challenges by reorienting development toward resource-aware design. Advances in efficient architectures (such as lightweight neural networks, pruning, quantisation, and knowledge distillation) aim to reduce the computational overhead of training and inference without compromising performance. These techniques are complemented by green training strategies, including adaptive scheduling, early stopping, and energy-aware neural architecture search, which optimise learning within explicit resource constraints.

At the infrastructure level, efforts are underway to power data centres with renewable energy and implement carbon offset programs, reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Decentralised approaches such as federated learning and edge computing help minimise data transfer and centralised server load, thereby reducing energy consumption and improving privacy. Sustainability is also pursued from a life-cycle perspective, with circular-economy principles guiding hardware design to reduce e-waste and promote recycling.

There is also growing recognition that sustainability must be measurable and accountable. While measuring energy efficiency spans multiple disciplines (including hardware engineering, systems design, and environmental science, among others), AI researchers are beginning to adopt standardised metrics for tracking energy use and carbon emissions. These metrics provide a foundation for transparent reporting and informed decision-making. However, interdisciplinary collaboration remains essential to ensure that assessments are accurate, meaningful, and actionable across the full AI development pipeline.

7.5. Desiderata

To achieve a truly sustainable trajectory, future Green AI systems must embody several critical desiderata. Energy efficiency should not be an afterthought but a primary design criterion, ensuring that advances in performance do not come at unsustainable ecological costs. Carbon transparency is equally essential, with reporting and auditing frameworks that make emissions visible and comparable across projects. Equity must also be prioritised by lowering entry barriers for resource-constrained institutions, thereby democratizing access to AI development and deployment. Hardware design must embrace sustainability, using recyclable, low-impact materials to mitigate the environmental impacts of large-scale production. Most importantly, AI must be aligned with broader sustainability goals, including climate action, biodiversity preservation, and the responsible use of natural resources, ensuring that the technology contributes positively to global challenges rather than exacerbating them.

7.6. Benefits

The benefits of green and sustainable AI extend well beyond reduced environmental impact. By prioritising energy efficiency, organisations can significantly cut operational costs, making AI more affordable and scalable across diverse contexts. These cost reductions, combined with lower entry barriers, help democratise the field and enable broader participation from smaller institutions and underrepresented regions. At the societal level, embracing sustainability enhances public perception of AI, presenting it as a force that not only drives innovation but also helps address humanity’s most pressing environmental and ethical challenges. Most critically, aligning AI with sustainability objectives ensures that technological progress reinforces, rather than undermines, global commitments to climate action and responsible stewardship of the planet. In this way, green AI has the potential to position AI as both a driver of scientific discovery and a partner in building a more sustainable future.

7.7. Recent Advances and Road Ahead

Recent advances in sustainable AI reflect a growing shift toward designing models and systems that are both environmentally responsible and computationally efficient. Early efforts focused on lightweight architectures such as TinyBERT, DistilBERT, and MobileNet. Nowadays, the scope has broadened to include a broader range of techniques across domains beyond language modelling and embedded systems.