Deep Learning Algorithms for Defect Detection on Electronic Assemblies: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the principal DL architectures to detect defects in EA?

- RQ2: What is the distribution of research focused on the processes of PCB and PCBA?

- RQ3: What defect types are detected by DL architectures in PCB and PCBA processes?

- RQ4: Which programming languages or frameworks are most commonly employed to detect defects using DL architectures?

- RQ5: What datasets are employed to train DL models for defect detection in EA?

2. Background and Relevant Research

2.1. Automatic Optical Inspection Machines

2.2. Related Works

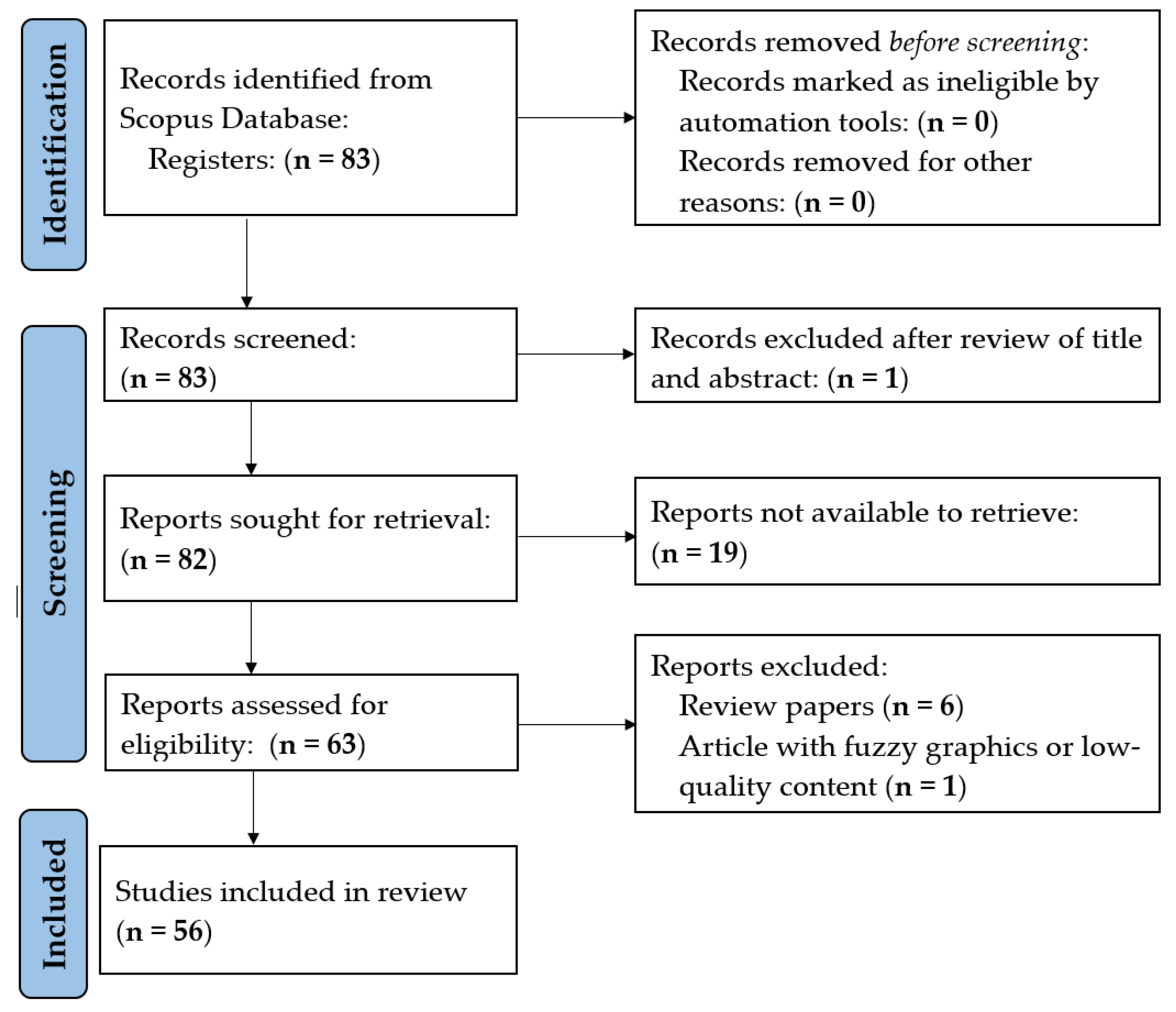

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Ten Most-Cited Works

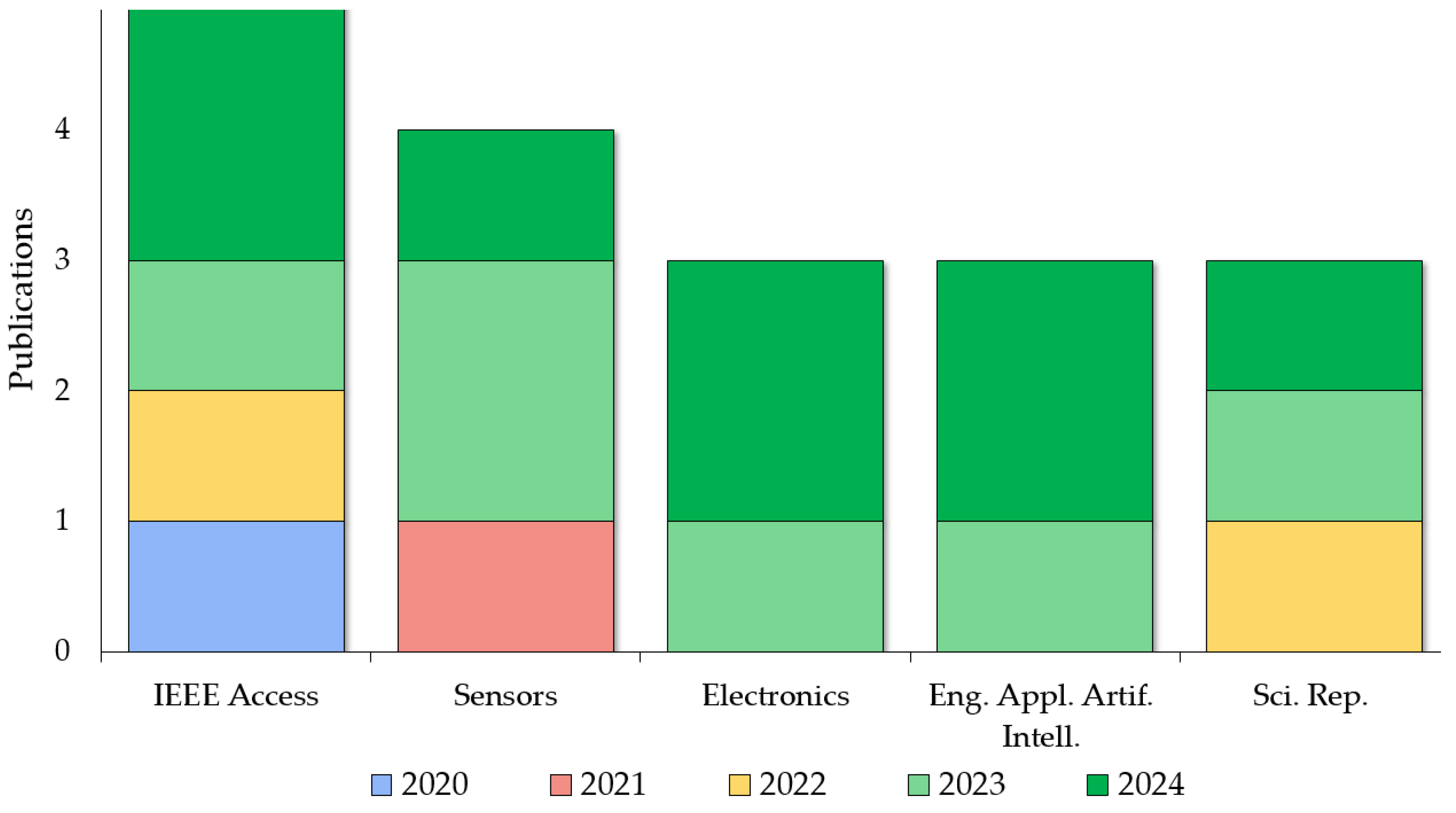

4.2. Summary of the Analyzed Articles

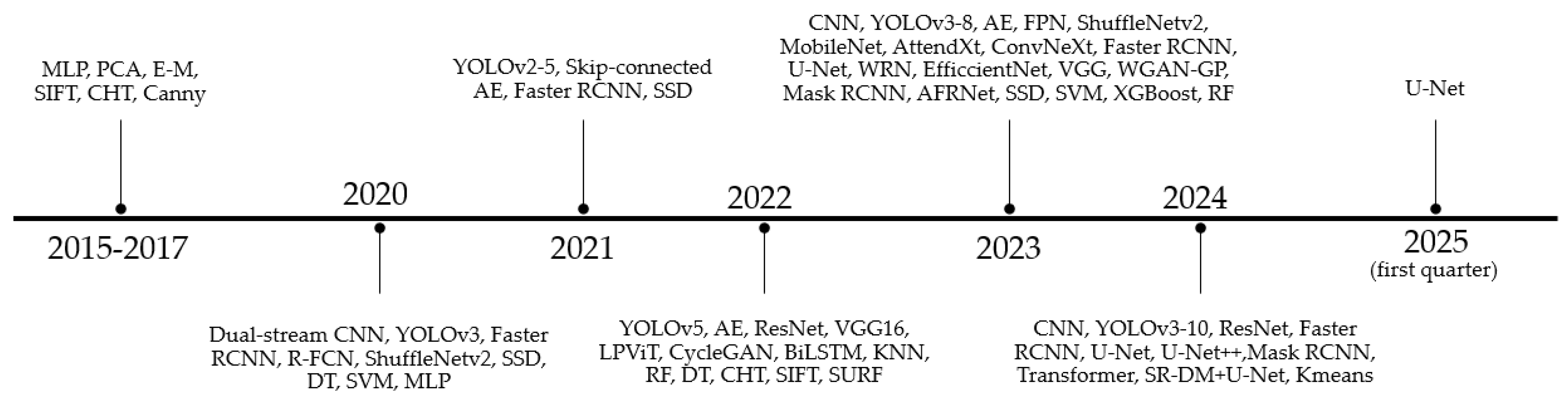

4.3. Principal DL Architectures to Detect Defects in Electronic Assemblies

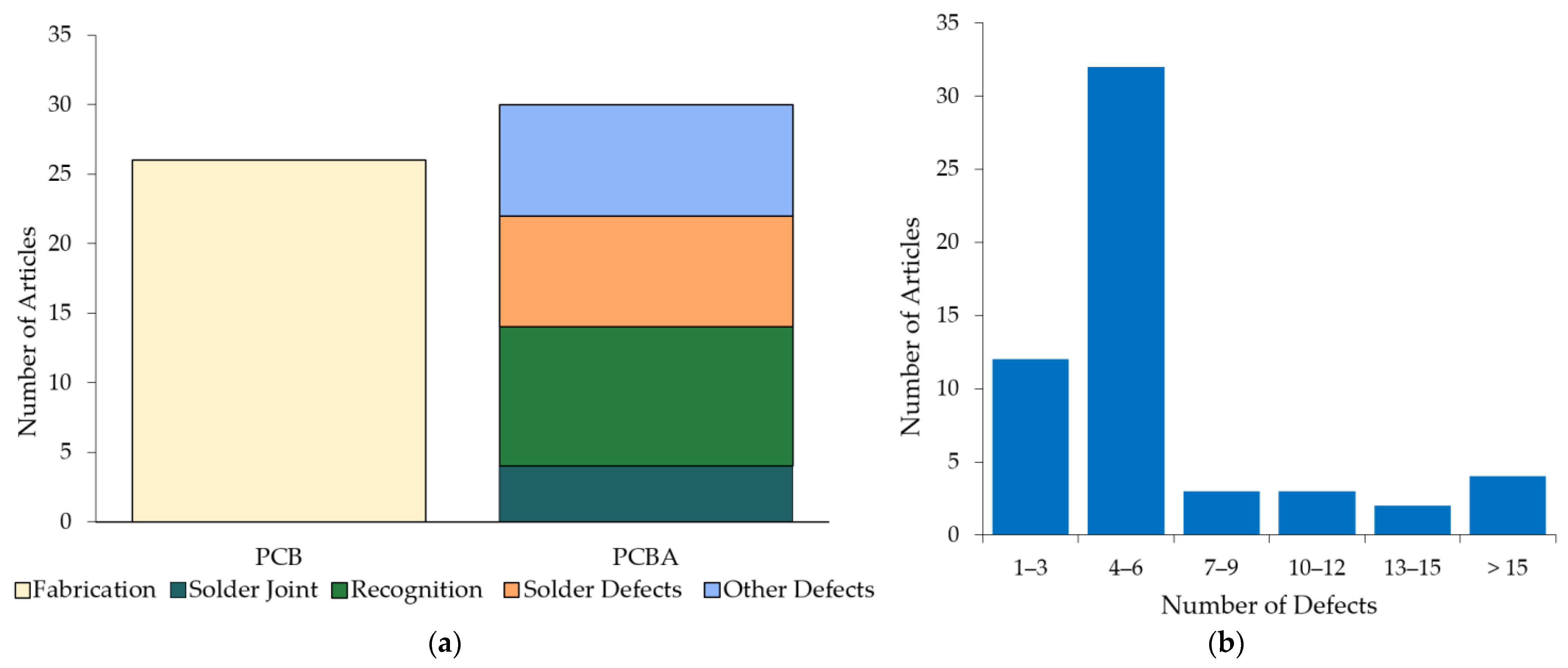

4.4. Distribution of Research Addressed to the Processes of PCB and PCBA

4.5. Defect Types Detected Using DL Architectures in PCB and PCBA Processes

4.6. Prevalent Programming Languages or Frameworks for Defect Detection Using DL Architectures

4.7. Datasets Employed to Train DL Models for Defect Detection in Electronic Assemblies

| PCB Defect Types | Qty. | Citation | PCBA Defect Types | Qty. | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spurious copper | 21 | [1,3,4,12,15,25,52,55,59,61,67,68,71,73,74,75,76,78,80,81,86] | Component (detection) | 15 | [5,13,18,21,24,26,53,62,65,72,77,79,84,85,87] |

| Mouse bite | |||||

| Spur | Component shifted | 6 | [13,21,24,53,65,84] | ||

| Open circuit | 20 | [1,3,4,12,15,25,52,55,59,61,67,68,71,73,74,75,76,78,80,81] | Insufficient solder | 5 | [2,13,53,60,70,85] |

| Short | Tombstone | 4 | [13,53,84,85] | ||

| Missing hole | Excess solder | 4 | [8,60,70,85] | ||

| Pinhole | 4 | [25,50,59,86] | Solder bridge | 4 | [8,13,60,79] |

| Scratch | 4 | [17,22,50,63] | Short | 3 | [2,24,54] |

| Missing conductor | 1 | [59] | Missing solder | 3 | [2,8,13,60] |

| Breakout | 1 | [59] | Flux side | 2 | [19,57] |

| Wrong size hole | 1 | [59] | Poor wetting | 2 | [19,53] |

| Others | 9 | [17,22,25,50,51,52,59,63,82] | Others | 18 | [5,6,8,13,18,19,21,22,24,53,54,56,58,60,64,65,66,69,70,72,77,79,83,84,85] |

| Datasets Employed to Train DL Models | PCB | PCBA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Custom | 5 | 21 | 26 |

| Specific | 14 | 1 | 15 |

| General-purpose + custom | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| General-purpose + specific | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| General-purpose + (specific + custom) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Ko, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, H. Printed circuit board defect detection using deep learning via a skip-connected convolutional autoencoder. Sensors 2021, 21, 4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasekara, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yuen, C.; Zhang, M.; Woo, C.W.; Low, J. Detecting anomalous solder joints in multi-sliced PCB X-ray images: A deep learning based approach. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Hou, S.; Zhou, H. PCB defect detection algorithm based on CDI-YOLO. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Cloutier, S.G. End-to-end deep learning framework for printed circuit board manufacturing defect classification. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K. Using deep learning to automatic inspection system of printed circuit board in manufacturing industry under the internet of things. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2023, 20, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.P.G.; Bastos-Filho, C.J.A.; Oliveira, S.C. Non-invasive embedded system hardware/firmware anomaly detection based on the electric current signature. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2022, 51, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; He, X.; Ming, W. A comprehensive review of deep learning-based PCB defect detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 139017–139038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Kuo, P.; Guo, J.I. Automatic industry PCB board DIP process defect detection system based on deep ensemble self-adaption method. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manufact. Technol. 2021, 11, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, R.; Wang, B.; Lin, Z. Defect identification of bare printed circuit boards based on Bayesian fusion of multi-scale features. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhao, Z.; Weng, L. MAS-YOLO: A lightweight detection algorithm for PCB defect detection based on improved YOLOv12. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineo, R.; Sorrenti, A.; Faro, R.; Mineo, G.; Cancelliere, F.; Faro, A. PCB-SAID: A Low-Cost Camera-Based Dataset for Few-Shot SMD Assembly Inspection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yao, J.; Guo, Y. Multiple detection model fusion framework for printed circuit board defect detection. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Sci.) 2023, 28, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Pan, C.S.; Hung, P.Y.; Chang, M.; Chen, K.Y. Detection and classification of printed circuit board assembly defects based on deep learning. J. Chin. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2020, 41, 401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, L.A.L.O.; Iano, Y.; Oliveira, G.G.D.; Vaz, G.C.; Carnielli, G.P.; Pereira, J.C.; Arthur, R. Automatic printed circuit board inspection: A comprehensible survey. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lim, J.; Baskaran, V.M.; Wang, X. A deep context learning based PCB defect detection model with anomalous trend alarming system. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancha, V.K.; Sibai, F.N.; Gonuguntla, V.; Vaddi, R. Utilizing YOLO models for real-world scenarios: Assessing novel mixed defect detection dataset in PCBs. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 100983–100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Tsai, P.X. Applying machine learning to construct a printed circuit board gold finger defect detection system. Electronics 2024, 13, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. A PCB electronic components detection network design based on effective receptive field size and anchor size matching. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 6682710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunraj, H.; Guerrier, P.; Fernandez, S.; Wong, A. SolderNet: Towards trustworthy visual inspection of solder joints in electronics manufacturing using explainable artificial intelligence. AI Mag. 2023, 44, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantone, C.; Faro, A. An overview of the automated optical inspection edge AI inference system solutions. In Advancing Edge Artificial Intelligence, 1st ed.; River Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Bui, H.A. A real-time defect detection in printed circuit boards applying deep learning. EUREKA Phys. Eng. 2022, 2, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkau, I.; Mujeeb, A.; Dai, W.; Erdt, M.; Sourin, A. The impact of a number of samples on unsupervised feature extraction, based on deep learning for detection defects in printed circuit boards. Future Internet 2021, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W. Investigation of visual inspection methodologies for printed circuit board products. J. Opt. 2024, 53, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, M.; Ghadermazi, J.; Shah, A.; Zayas-Castro, J.L. Toward optimal defect detection in assembled printed circuit boards under adverse conditions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 127119–127131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, J. Detection of PCB surface defects with improved faster-RCNN and feature pyramid network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108335–108345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.S.; Wahab, M.N.A.; Mohamed, A.S.A.; Noor, M.H.M.; Kang, K.B.; Chuan, L.L.; Brigitte, L.W.J. Enhancing efficientnet-YOLOv4 for integrated circuit detection on printed circuit board (PCB). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 25066–25078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebayyeh, A.A.R.M.A.; Mousavi, A. A review and analysis of automatic optical inspection and quality monitoring methods in electronics industry. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183192–183271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K. AI-Driven defect detection in PCB manufacturing: A computer vision approach using convolutional neural networks. Eur. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2025, 12, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya, S.R. Automatic Optical Inspection-Based PCB Fault Detection Using Image Processing. Master’s Thesis, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, T.; Towell, G.; Tafoya, C.; Lozoya, A. Comparative Analysis of Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) Performance with Different Solder Alloys. In Proceedings of the SMTA International, Rosemont, IL, USA, 20–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- SMTnet. What Is Really Inside Your AOI? Available online: https://smtnet.com/library/index.cfm?fuseaction=view_article&article_id=1771&company_id=46029 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Ling, Q.; Isa, N.A.M. Printed circuit board defect detection methods based on image processing, machine learning and deep learning: A survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 15921–15944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Seo, H.; Cho, Y.-J. Analysis of training deep learning models for PCB defect detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zheng, S.; Kong, Y.; Chen, J. Recent advances in surface defect inspection of industrial products using deep learning techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 113, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.B.; Babiceanu, R.F. Deep CNN-based visual defect detection: Survey of current literature. Comput. Ind. 2023, 148, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xie, L.; Tian, H.; Li, X. Review of wafer surface defect detection methods. Electronics 2023, 12, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Chen, H.; Luo, Z. A survey of defect detection applications based on generative adversarial networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 113493–113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Luo, Q.; Zhou, B.; Li, C.; Tian, L. Research progress of automated visual surface defect detection for industrial metal planar materials. Sensors 2020, 20, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Hussain, M.; Al-Aqrabi, H.; Alsboui, T.; Hill, R. A review on defect detection of electroluminescence-based photovoltaic cell surface images using computer vision. Energies 2023, 16, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Kharche, S.; Chauhan, A.; Salvi, P. PCB defect detection methods: A review of existing methods and potential enhancements. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2024, 17, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarraga-Gómez, H.; Crosby, K.; Terada, M.; Rad, M.N. Assessing electronics with advanced 3D X-ray imaging techniques, nanoscale tomography, and deep learning. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2024, 24, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberironaghi, A.; Ren, J.; El-Gindy, M. Defect detection methods for industrial products using deep learning techniques: A review. Algorithms 2023, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Lee, C.; Charpentier, N.M.; Deng, Y.; Yan, Q.; Gabriel, J.P. Drivers and pathways for the recovery of critical metals from waste-printed circuit boards. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2309635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Ding, G.; Qin, S. Review of vision-based defect detection research and its perspectives for printed circuit board. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 70, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, L.; Kehtarnavaz, N. A survey of detection methods for die attachment and wire bonding defects in integrated circuit manufacturing. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 83826–83840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, C.O.; Borges, M.A.V.; Antunes, J.A.D.V. Industry 4.0: What makes it a revolution? A historical framework to understand the phenomenon. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotero. Available online: https://www.zotero.org/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Tsai, D.M.; Hsieh, Y.C. Machine vision-based positioning and inspection using expectation–maximization technique. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2017, 66, 2858–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibhatla, V.A.; Chih, H.C.; Hsu, C.C.; Cheng, J.; Abbod, M.F.; Shieh, J.S. Applying deep learning to defect detection in printed circuit boards via a newest model of You-Only-Look-Once. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 4411–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Zhang, Y. LPViT: A transformer based model for PCB image classification and defect detection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 42542–42553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Hwang, R.C.; Huang, H.C. PCB defect detection based on deep learning algorithm. Processes 2023, 11, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Yoo, S.; Kim, S.W. A contactless PCBA defect detection method: Convolutional neural networks with thermographic images. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 12, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Wan, F.; Lei, G.; Xu, L.; Xu, C.; Xiong, Y. YOLO-MBBi: PCB surface defect detection method based on enhanced YOLOv5. Electronics 2023, 12, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klco, P.; Koniar, D.; Hargas, L.; Pociskova Dimova, K.; Chnapko, M. Quality inspection of specific electronic boards by deep neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.T.; Mustapha, A.; Ibrahim, Z.B.; Ramli, S.; Eong, B.C. Real-time automatic inspection system for the classification of PCB flux defects. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2015, 8, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiawang, H.; Lurong, J.; Suoming, Z.; Renwang, L.; Changguo, X.; Xinxia, L.; Yongjian, S. Fast plug-in capacitors polarity detection with morphology and SVM fusion method in automatic optical inspection system. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 2555–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onshaunjit, J.; Srinonchat, J. Algorithmic scheme for concurrent detection and classification of printed circuit board defects. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 71, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.H.; Suo, Z.; Chan, T.T.L.; Nguyen, H.T.; Lun, D.P.K. PCB soldering defect inspection using multitask learning under low data regimes. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2300364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubiti, S.A.; Alenezi, F.; Shitharth, S.; K., S.; Reddy, C.V.S. Circuit manufacturing defect detection using vgg16 convolutional neural networks. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 1070405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, J.; Zhou, J.; Fan, X.; Tang, J. An efficient SMD-PCBA detection based on YOLOV7 network model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.A.; Thoi, D.K.T.; Choi, H.; Park, S. Defect detection in printed circuit boards using semi-supervised learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candido De Oliveira, D.; Nassu, B.T.; Wehrmeister, M.A. Image-based detection of modifications in assembled PCBs with deep convolutional autoencoders. Sensors 2023, 23, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruengrote, S.; Kasetravetin, K.; Srisom, P.; Sukchok, T.; Kaewdook, D. Design of deep learning techniques for PCBs defect detecting system based on YOLOv10. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 18741–18749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y.; Xia, M.; Gao, Z.; Ye, W. Automated void detection in high resolution x-ray printed circuit boards (PCBs) images with deep segmentation neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Meng, S.; Wang, X. Local and global context-enhanced lightweight CenterNet for PCB surface defect detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Tang, X.; Ning, H.; Yang, Z. LW-YOLO: Lightweight deep learning model for fast and precise defect detection in printed circuit boards. Symmetry 2024, 16, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Kieu, X.T.; Chu, D.T.; HoangVan, X.; Tan, P.X.; Le, T.N. Deep learning-enhanced defects detection for printed circuit boards. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, G.; Calabrese, M.; Agnusdei, L.; Papadia, G.; Del Prete, A. SolDef_AI: An open source PCB dataset for Mask R-CNN defect detection in soldering processes of electronic components. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Tang, X.; Wang, H.; Hao, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Jiang, B.; Liu, C. Industrial product surface defect detection via the fast denoising diffusion implicit model. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber. 2024, 15, 5091–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, G.G.; Caumo Vaz, G.; Antonio Andrade, M.; Iano, Y.; Ronchini Ximenes, L.; Arthur, R. System for PCB defect detection using visual computing and deep learning for production optimization. IET Circuits Devices Syst. 2023, 2023, 6681526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W. PCB defect detection algorithm based on deep learning. Optik 2024, 315, 172036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasumponthevar, M.K.; Jeyaraj, P.R. Reliability analysis and terahertz characterization of circuit board defect employing branchy neural network in edge-cloud fusion architecture. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138, 109468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.B.; Zhang, Z.F.; Zhang, T.L.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Zhou, M. SMC-YOLO: Surface defect detection of PCB based on multi-scale features and dual loss functions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 137667–137682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, E.; Karimian, G.; Shoaran, M.; Yadipour, R.; Sobhi, J. Valid-IoU: An improved IoU-based loss function and its application to detection of defects on printed circuit boards. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 84, 13905–13928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, Q.; Zhan, J.; Duan, L. A fast defect detection method for PCBA based on YOLOv7. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2024, 18, 2199–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Maidin, S.S.; Batumalay, M. PCB defect detection based on pseudo-inverse transformation and YOLOv5. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; He, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, K.; Ding, S.; Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Niu, Y.; Xiao, S.; et al. Industry-oriented detection method of PCBA defects using semantic segmentation models. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balizh, K.S.; Eremeev, P.M.; Simakhina, E.A. Proposals for development of the prospective system for optical quality control of the assembly of microelectronic devices. Russ. Microelectron. 2023, 52, S246–S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.P.R.; Parameshachari, B.D. Effective PCB defect detection using stacked autoencoder with Bi-LSTM network. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2022, 15, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelidis, A.; Dimitriou, N.; Leontaris, L.; Ioannidis, D.; Tinker, G.; Tzovaras, D. A deep regression framework toward laboratory accuracy in the shop floor of microelectronics. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2023, 19, 2652–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.U.; Bondrea, I.; Brad, R. Automated PCB inspection system. TEM J. 2017, 6, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lv, Q.; Yang, J.; Yan, X.; Xu, X. Electronic component detection based on image sample generation. Solder. Surf. Mt. Technol. 2022, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-G.; Park, T.-H. SMT assembly inspection using dual-stream convolutional networks and two solder regions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lai, J.; Zhu, J.; Han, Y. An adaptive feature reconstruction network for the precise segmentation of surface defects on printed circuit boards. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 3197–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E. Advancements in electronic component assembly: Real-time AI-driven inspection techniques. Electronics 2024, 13, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Podishetti, R.; Grossmann, D.; Bregulla, M. Benchmarking CNN architectures for tool classification: Evaluating cnn performance on a unique dataset generated by novel image acquisition system. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 96400–96422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Zhao, E.; Zhou, J.; Tan, C.; Shen, K.; Duan, L. Defect recognition of printed circuit board assemblies via enhanced swin-condinst network. Measurement 2025, 253, 117879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, S.K.; Kuehlkamp, A.; Nabrzyski, J. Advancing transparency and responsibility in machine learning: The critical role of FAIR principles-A comprehensive review. ACM J. Responsible Comput. 2025, 2, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei Khoei, T.; Ould Slimane, H.; Kaabouch, N. Deep learning: Systematic review, models, challenges, and research directions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 23103–23124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, I.H.; Kumar, S.; Gandomi, A.H. Breaking the data barrier: A review of deep learning techniques for democratizing AI with small datasets. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamer, F.; Jachemich, R.; Puttero, S.; Verna, E.; Galetto, M. Integrative inspection methodology for enhanced PCB remanufacturing using artificial intelligence. Procedia CIRP 2024, 132, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Ouyang, B.; Deng, Z.; Liang, T.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, K.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. A dataset for deep learning based detection of printed circuit board surface defect. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, L.; Tubaishat, A.; Shah, B.; Mussiraliyeva, S.; Maqbool, F.; Razzaq, S.; Anwar, S. Deepvoc: A linked open vocabulary for reproducible and reliable deep learning experiments. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 8755–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Jiang, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. Defects detection in screen-printed circuits based on an enhanced YOLOv8n algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Liu, G.; Gao, Y. GESC-YOLO: Improved lightweight printed circuit board defect detection based algorithm. Sensors 2025, 25, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, X. EAR-YOLO: An improved model for printed circuit board surface defect detection. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Ge, Y.; Meng, L. A survey of deep learning for industrial visual anomaly detection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; Sun, Z.; Luo, H.; Tao, D. A survey on self-supervised learning: Algorithms, applications, and future trends. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 9052–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.H.D.S.; Freire, A.; Azevedo, G.O.; Oliveira, S.C.; da Silva, C.M.; Fernandes, B.J. GEN self-labeling object detector for PCB recycling evaluation. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Xie, S.; He, K. Deconstructing denoising diffusion models for self-supervised learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Serag, A. Self-supervised learning powered by synthetic data from diffusion models: Application to X-Ray images. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 59074–59084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdem, B.; Kuzlu, M.; Gullu, M.K.; Catak, F.O.; Tabassum, M. Federated learning: Overview, strategies, applications, tools and future directions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Di, K.; Xu, Y.; Ye, H.J.; Luo, W.; Zou, N. FedDyMem: Efficient federated learning with dynamic memory and memory-reduce for unsupervised image anomaly detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.21012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yan, T.; Zhang, J. Vision-based structural adhesive detection for electronic components on PCBs. Electronics 2025, 14, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| The article focuses on defect detection on electronic assemblies (PCB or PCBA) using DL, ML, or CV algorithms. | The article reports defect detection using DL, ML, or CV not related to EA (PCB or PCBA). |

| The article reports at least four of the following points: algorithms used, electronic assembly type, hardware, programming language, dataset employed, metrics applied, and classification of the EA as defective or not, or a description of defects detected. | The reviews, surveys, or exploratory studies are not considered. |

| The article presents illegible or fuzzy images. |

| Database | Search String |

|---|---|

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((manufactur * OR assembl *) AND (“quality inspection” OR “defect detection” OR “quality assurance” OR “defect inspection” OR “visual inspection”) AND (“machine vision” OR “computer vision” OR “artificial vision” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “CNN” OR “convolutional neural network”) AND (“electronic assembly” OR “printed circuit board”)) |

| Ref | Year | AI | Architecture | EA | PU | PL | FAL | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2021 | dl | Skip-connected AE, CAE | p | - | - | - | HRIPCB |

| [2] | 2023 | dl | CAE + ResNet101 | a | g | pn | py | Custom A + B (AXI) |

| [3] | 2024 | dl | enh. YOLOv7tiny (CA backbone and neck + DSConv + InnerCIoU) | p | c, g | pn | py, cu | PKU-Market-PCB |

| [4] | 2022 | dl | enh. YOLOv5 (transformer module at the junction neck and backbone + BiFPN+ PANet neck modules) | p | g | pn | py | HRIPCB |

| [5] | 2023 | dl | YOLOv3, SSD, RCNN, RetinaNet | a | - | pn | tf, ke, oc | Custom |

| [6] | 2022 | dl-mlcv | AE, RF, SIFT | a | c, g | pn | ke | Custom |

| [8] | 2021 | dl | (FRCNN + ResNet-101 + FPN)/(YOLOv2 + ResNet-101) | a | g | - | - | Custom A + B + C |

| [12] | 2023 | dl-mlcv | (SSD/YOLOv3/FPN) + XGBoost/RF/TPOT | p | - | - | - | Public Synth. PCB, D-PCB |

| [13] | 2020 | dl-mlcv | Kmeans + YOLOv3, R-FCN, SSD, FRCNN | a | g | - | - | Custom |

| [15] | 2023 | dl | enh. YOLOv5 (new FPN + modified CIoU loss) | p | g | pn | py, cu | COCO + TDD-Net |

| [17] | 2024 | dl | YOLOv3, FRCNN | p | - | - | - | Custom |

| [18] | 2021 | dl | enh. YOLOv3 (RFE and anchor matching), FRCNN, SSD | a | c, g | pn | tf, cu | Custom |

| [19] | 2023 | dl | ShuffleNetv2, MobileNet, AttenNeXt, ConvNeXt | a | c | - | - | ImageNet-1k + Custom |

| [21] | 2022 | dl-mlcv | ORB + RANSAC + ResNet-50 | a | c, g | - | - | Custom A, Custom B |

| [22] | 2022 | dl | enh. VGG16 (RotNet), ResNet-50 | a, p | c, g | pn | tf, ke | Imagenet + (Custom A, B) |

| [24] | 2023 | dl | YOLOv4, YOLOR-P6, FRCNN (ResNeXt-101-FPN 3x) | a | c | pn | - | COCO + Custom |

| [25] | 2020 | dl | enh. FRCNN (ResNet50, ResNet101) + GARPN + ShuffleNetV2 | p | c, g | pn | tf | Custom |

| [26] | 2024 | dl | enh. YOLOv4 (backbone EfficientNet) | a | g | pn | py, tf, ke | Custom (IC’s) |

| [50] | 2017 | mlcv | Spiral Search + Canny + PCA + E-M, SIFT | p | c | c++ | - | Custom |

| [51] | 2021 | dl | YOLOv5 (small, medium, large models) | p | g | pn | py | COCO + Custom |

| [52] | 2022 | dl | LPViT (ViT + Label Smooth + MPP), ResNet50, Swin Transformer | p, a | c, g | pn | py | D-PCB, Micro-PCB |

| [53] | 2023 | dl | Custom CNN | a | g | - | - | Custom A + Custom B |

| [54] | 2022 | dl | YOLOv5, SSIM + AE | a | c, g | pn | py, ke | Custom |

| [55] | 2023 | dl | enh. YOLOv5s (MBConv, CBAM attention, BiFPN, SIoU loss) | p | c, g | pn | py, cu | PKU-Market-PCB, D-PCB |

| [56] | 2023 | dl | YOLOv8n-s, YOLOv5m-n-s, FRCNN | a | c, g | pn | py | Custom |

| [57] | 2015 | mlcv | MLP (scaled conjugate gradient, Levenberg Marquardt, adaptive learning rate) | a | c | - | - | Custom (Flux) |

| [58] | 2023 | mlcv | SVM/HOG | a | c, g | - | - | Custom (Capacitors) |

| [59] | 2022 | mlcv | CHT + MR + CCL | p | c | - | - | Custom |

| [60] | 2023 | dl | enh. U-Net (multitask learning) | a | - | - | py | ImageNet + PCBSPDefect |

| [61] | 2022 | dl | VGG16, ResNet | p | c, g | - | tf, ke | ImageNet + (PKU-Market-PCB enriched with Custom) |

| [62] | 2023 | dl | enh. YOLOv7 (CA-based prediction, improved feature function, SEIoU loss) | a | g | pn | cu | COCO 2017 + FICS-PCB, PASCAL VOC 2012, COCO 2017 |

| [63] | 2023 | dl-mlcv | WRN-28-2, EfficientNet-B5, XGBoost | p | - | - | - | Custom |

| [64] | 2023 | dl | CAE/VGG19 | a | g | pn | tf, oc | ImageNet + (MPI-PCB, MVTec-AD) |

| [65] | 2024 | dl | YOLOv10, YOLOv5, YOLOv8, FRCNN | a | c, g | pn | - | Custom (components) |

| [66] | 2024 | dl | Resnet34 + UnetPlusPlus | a | g | - | py | ImageNet + Custom (AXI) |

| [67] | 2024 | dl | YOLOv8 backbone + transformer module | p | g | - | py | COCO + HRIPCB |

| [68] | 2024 | dl | enh. YOLOv8 (C2f, BiFPN, MPDIoU loss) | p | c, g | pn | py | PKU-Market-PCB |

| [69] | 2025 | dl-mlcv | ORB + RANSAC + U-Net | a | g | - | pqt | PreTrain + Custom (components) |

| [70] | 2024 | dl | Mask-RCNN | a | - | - | - | PreTrain + SolDef_AI |

| [71] | 2024 | dl | SR-DM (spectral radius featured guided diffusion model with U-Net) | p | - | pn | py | HRIPCB = PKU-Market-PCB |

| [72] | 2023 | dl | U-Net + (VGG + CAE + WGAN-GP) | a | - | pn | tf, oc | Custom (components) |

| [73] | 2024 | dl-mlcv | Kmeans + enh. YOLOv7 (triplet attention mechanism + WIoUv2 loss + RFE) | p | g | pn | cu | PKU-Market-PCB |

| [74] | 2024 | dl | Enh. YOLOX (Swin Transformer block) + side branch edge nodes | p | c, g | - | tf | PKU-Market-PCB, Kaggle PCB surface |

| [75] | 2024 | dl | enh. YOLOv7tiny (add conv. layers to SPPCSPC, an extra feature channel, EIoU/NWD loss) | p | g | pn | py, cu | PreTrain +PKU-Market-PCB |

| [76] | 2024 | dl | enh.YOLOv4 (VIoU loss) | p | g | - | cu, oc | HRIPCB |

| [77] | 2024 | dl | enh. YOLOv7 (mish activation f., SEAM attention mechanism, SIoU loss) | a | g | pn | py | Custom |

| [78] | 2024 | dl | enh. YOLOv5 (transformer encoder module replace Bottleneck module) | p | - | - | - | PreTrain + PKU-Market-PCB |

| [79] | 2024 | dl | U-Net/rule-based defect recognition | a | g | pn | py | Custom (obtained by AOI system) |

| [80] | 2023 | dl | YOLOv8 | p | - | - | - | HRIPCB |

| [81] | 2022 | dl-mlcv | BRISK + SURF + Stacked AE + (BiLSTM, KNN, RF, DT) | p | c | m | - | PKU-Market-PCB |

| [82] | 2023 | dl | Mask-RCNN + FRCNN+ enh. ResNet (class. layer replaced by regression) | p | g | - | - | ImageNet + Custom (Glue) |

| [83] | 2017 | mlcv | Histogram + CHT + Euclidean dis. | a | c | m | - | Custom (AXI) |

| [84] | 2022 | dl | CycleGAN + CNN | a | g | pn | tf, ke | Custom |

| [85] | 2020 | dl-mlcv | Dual-stream CNN, DT, SVM, MLP | a | g | - | cntk | Custom (components) |

| [86] | 2023 | dl | AFRNet (Siamese encoder + asymmetrical feature reconstruction modules) | p | g | - | py, cu | PCB surface-defect |

| [87] | 2024 | dl | Custom CNN | a | g | pn | tf | Custom |

| Base | Example of Models | PCB | PCBA | SUM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO | YOLOv2, YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv10 | 15 | 11 | 26 |

| CNN | VGG, SSD, ResNet, ShuffleNet, MobileNet, EfficientNet, AttendNeXt, ConvNeXt, AFRNet | 8 | 17 | 25 |

| R-CNN | Faster R-CNN, Mask R-CNN, R-FCN | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| AE | Variational AE (VAE), Denoising AE | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| U-Net | U-Net, U-Net++, Attention U-Net | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| GAN | CycleGAN, WGAN | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Transformer | LPViT | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| RNN | BiLSTM | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ML-CV | MLP, SVM, PCA, XGBoost, Kmeans, KNN, RF, DT, SIFT, CHT, Canny | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| Description | Metrics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1_Score | ||

| Architecture | YOLO | 91.5% | 96.2% | 92.4% | 93.2% |

| CNN | 93.0% | 88.3% | 89.6% | 85.9% | |

| R-CNN | 77.9% | 84.3% | 79.6% | 79.6% | |

| AE | 93.8% | 91.6% | 83.0% | 92.2% | |

| U-Net | 97.5% | 83.3% | 99.8% | 90.9% | |

| GAN | 94.6% | - | 94.7% | - | |

| Transformer | 99.1% | 99.0% | 99.0% | 99.0% | |

| RNN | 100.0% | - | 98.3% | 99.4% | |

| ML-CV | 96.8% | 99.5% | 99.1% | 99.8% | |

| Datasets | Custom | 94.4% | 93.8% | 91.3% | 92.9% |

| Specific | 97.7% | 92.2% | 94.5% | 93.1% | |

| General-purpose + custom | 84.2% | 94.4% | 84.0% | 79.8% | |

| General-purpose + specific | 77.5% | 97.6% | 91.8% | 99.7% | |

| General-purpose + (specific + custom) | - | 74.5% | 77.2% | 75.8% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Montoya Magaña, B.; Hernández-Uribe, Ó.; Cárdenas-Robledo, L.A.; Cantoral-Ceballos, J.A. Deep Learning Algorithms for Defect Detection on Electronic Assemblies: A Systematic Literature Review. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2026, 8, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/make8010005

Montoya Magaña B, Hernández-Uribe Ó, Cárdenas-Robledo LA, Cantoral-Ceballos JA. Deep Learning Algorithms for Defect Detection on Electronic Assemblies: A Systematic Literature Review. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. 2026; 8(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/make8010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontoya Magaña, Bernardo, Óscar Hernández-Uribe, Leonor Adriana Cárdenas-Robledo, and Jose Antonio Cantoral-Ceballos. 2026. "Deep Learning Algorithms for Defect Detection on Electronic Assemblies: A Systematic Literature Review" Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 8, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/make8010005

APA StyleMontoya Magaña, B., Hernández-Uribe, Ó., Cárdenas-Robledo, L. A., & Cantoral-Ceballos, J. A. (2026). Deep Learning Algorithms for Defect Detection on Electronic Assemblies: A Systematic Literature Review. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/make8010005