1. Introduction

The field of materials science and engineering is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the exponential growth of experimental data, multiscale simulations, and advanced characterization techniques [

1]. Traditionally, progress in this domain has relied heavily on expert knowledge accumulated through time-consuming cycles of trial, intuition, and refinement. Although indispensable for developing physical understanding and generating scientific hypotheses, such expert-driven approaches are increasingly insufficient to address the complexity of modern material systems [

2,

3]. The rational design of new materials, especially at the nanoscale, remains constrained by the vast combinatorial space of chemical compositions, structural configurations, and processing conditions that must be explored to achieve optimal functionality [

4,

5]. In this context, nanomaterials have gained particular attention due to their unique properties arising from quantum confinement, high surface-to-volume ratios, and nanoscale structural effects [

6,

7].

Nanomaterials are generally defined as materials with at least one characteristic dimension lower than 100 nm, where deviations from bulk behavior become significant [

8]. Several classes of nanomaterials are commonly distinguished: (i) zero-dimensional (0D) nanomaterials, with all the dimensions in the range of nanometers, such as metallic nanoparticles and semiconductor quantum dots [

9]; (ii) one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures, where two dimensions are confined to the nanometer scale and the third dimension extends beyond the nanoscale, including nanowires, nanorods, and carbon nanotubes, which exhibit direction-dependent mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties [

10,

11]; and two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials, characterized by one dimension (thickness) in the nanometer range, such as graphene, borophene, and transition metal dichalcogenides, characterized by atomically thin layers with exceptional electronic mobility and mechanical flexibility [

12,

13]. In this regard, it is important to highlight the importance of nanocomposites, where nanoscale fillers embedded within polymeric, ceramic, or metallic matrices significantly enhance mechanical reinforcement, electrical conductivity, thermal stability, or optical performance [

14]. These types of nano-based materials promote advances in energy storage and conversion, photonics, catalysis, sensing, environmental remediation, and biomedical engineering. However, predicting and optimizing their behavior requires navigating highly nonlinear, multidimensional relationships among structure, morphology, chemistry, defects, and processing conditions.

In response to these challenges, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in material research. ML algorithms can learn complex patterns from large datasets, capture nonlinear structure–property relationships, and provide accurate predictions without requiring explicit analytical models [

15,

16]. Their applications now span the prediction of electronic, optical, catalytic, and mechanical properties; the modeling of synthesis pathways; the segmentation and interpretation of microscopy data; and the inverse design of nanomaterials and nanostructured devices. The ML paradigms most relevant to nanotechnology include: (i) supervised learning, where models such as neural networks, support vector machines, random forests, and regression frameworks are trained to predict properties or classify samples based on labeled data [

17,

18]; (ii) unsupervised learning, used for clustering, dimensionality reduction, and pattern discovery in unlabeled datasets (e.g., spectral classification, microstructure identification) [

19,

20]; (iii) semi-supervised learning, which leverages limited labeled data jointly with large unlabeled datasets—a frequent scenario in materials databases [

21]; (iv) reinforcement learning, increasingly applied to autonomous synthesis control, design optimization, and active search in high-dimensional chemical spaces [

22,

23]; and deep learning, encompassing convolutional neural networks for image-based characterization [

24], graph neural networks for crystal and molecular graphs [

25], recurrent architectures for sequential synthesis data, and encoder–decoder models for microstructural segmentation [

26]. These techniques have demonstrated remarkable capabilities, enabling, for example, predictive performance approaching quantum-mechanical accuracy, accelerated discovery of electrocatalysts through active learning loops, machine-learned interatomic potentials for multiscale simulations, and closed-loop robotic laboratories for automated nanoparticle synthesis.

Despite these advances, many of the most powerful ML models such as deep learning architectures operate as black boxes, providing high accuracy at the expense of interpretability [

27]. This lack of transparency raises concerns about reliability, generalization, and reproducibility, particularly in high-stakes domains such as nanomedicine, energy materials, and environmental nanotechnology. Scientific discovery requires both accurate predictions and mechanistic understanding; therefore, interpretability becomes essential.

Although ML has become increasingly influential in accelerating nanomaterial discovery and design, existing review studies largely concentrate on the applicability of specific ML models, material systems, or narrowly defined application domains [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. These reviews typically provide valuable methodological perceptions and detailed case studies; however, they remain predominantly qualitative, application-focused, and fragmented across subfields. As a result, a comprehensive and structured understanding of how ML methodologies are being adopted across the entire nanomaterial research scenery, which techniques dominate at different stages of development, and how research activity has evolved globally over time is still lacking. There is a noticeable gap in large-scale, data-driven analyses that systematically map scientific production, identify influential actors and publication venues, and reveal the thematic structure and emerging research fronts of the field. In this context, the present review aims to provide a comprehensive and overview of the application of ML in nanomaterial discovery and design. Specifically, this study conducts a large-scale bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed research articles published between 2010 and 2025 and indexed in the Scopus and Web of Science databases. The objectives of the review are threefold: (i) to quantitatively characterize the growth, geographical distribution, and institutional structure of scientific production in this rapidly evolving field; (ii) to identify the most influential journals, articles, and research actors shaping its development; and (iii) to uncover the main thematic clusters, emerging research fronts, and strategic directions through keyword co-occurrence and thematic mapping analyses. By offering a data-driven perspective on the intellectual structure and global evolution of machine-learning-enabled nanomaterial research, this review complements existing application-focused studies and provides a consolidated reference background to guide upcoming research, interdisciplinary collaboration, and methodological innovation.

2. Methods

This study employs a structured bibliometric approach to map the scientific development of ML for nanomaterial research. Bibliometric analysis was selected because it enables the systematic quantification of research dynamics, including publication growth, intellectual foundations, and thematic evolution [

34,

35]. Such quantitative evidence is essential for characterizing an emerging multidisciplinary domain that spans materials science, data-driven modeling, and computational engineering.

To strengthen reproducibility and methodological transparency, the workflow incorporated the core principles of the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, which provide a standardized framework for documenting the identification, screening, and inclusion of scientific records [

36,

37]. Although PRISMA 2020 is primarily associated with systematic reviews, its structured screening logic is increasingly adopted in large-scale bibliometric studies to ensure rigorous traceability of dataset construction.

The bibliographic dataset was compiled from two leading scientific indexing platforms: Scopus and the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS). These databases were selected due to their extensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals, robust citation indexing, and high metadata quality, which are essential for network-based analyses. The search was executed in November 2025. The search covered the period from 2010 to 2025 to capture the development of research involving ML techniques applied to nanomaterials over the past 15 years. This timeframe was selected because the integration of modern ML methods into materials science began to gain clear momentum after 2010, following advances in computational power, the emergence of large-scale materials databases, and the widespread adoption of data-driven modeling workflows in materials design. All retrieved records were exported with complete metadata and saved in formats compatible with Bibliometrix 5.0, an R 4.5.2 tool [

38].

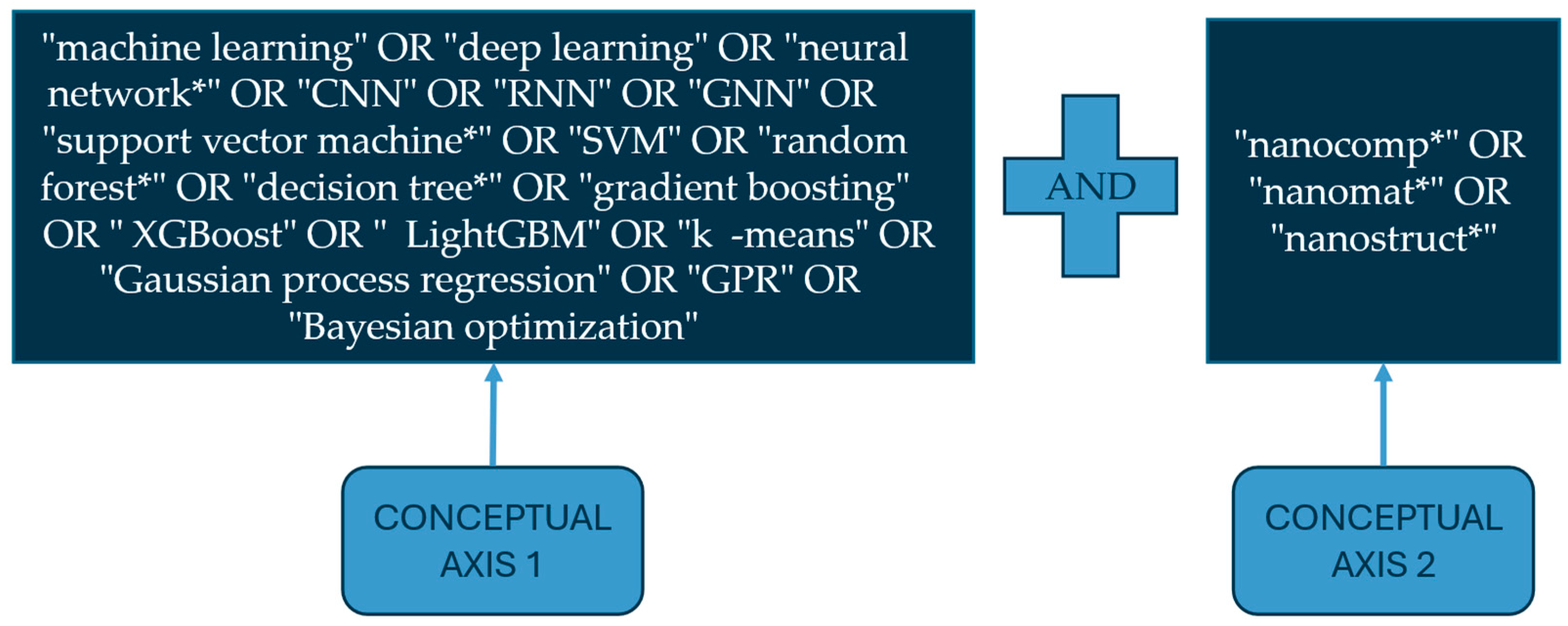

The construction of the search strategy was guided by two complementary conceptual axes that define the intersection between ML and nanomaterial research, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The first conceptual axis encompasses methodological terminology associated with ML and data-driven modeling, covering general AI descriptors as well as specific algorithmic families widely used in predictive modeling, pattern recognition, and optimization. The second conceptual axis captures the scientific domain of nanomaterials, including descriptors commonly employed to denote nanoscale materials, nanostructured systems, and related material classes. This approach ensures broad coverage while maintaining a manageable search strategy. Within each axis, synonymous or closely related expressions were internally linked to maximize coverage, and the wilcard (*) was applied to capture variations in word endings and plural forms. The two axes were subsequently combined using the Boolean operator AND, ensuring that the retrieved publications explicitly lay at the intersection of ML methodologies and nanomaterial discovery and design.

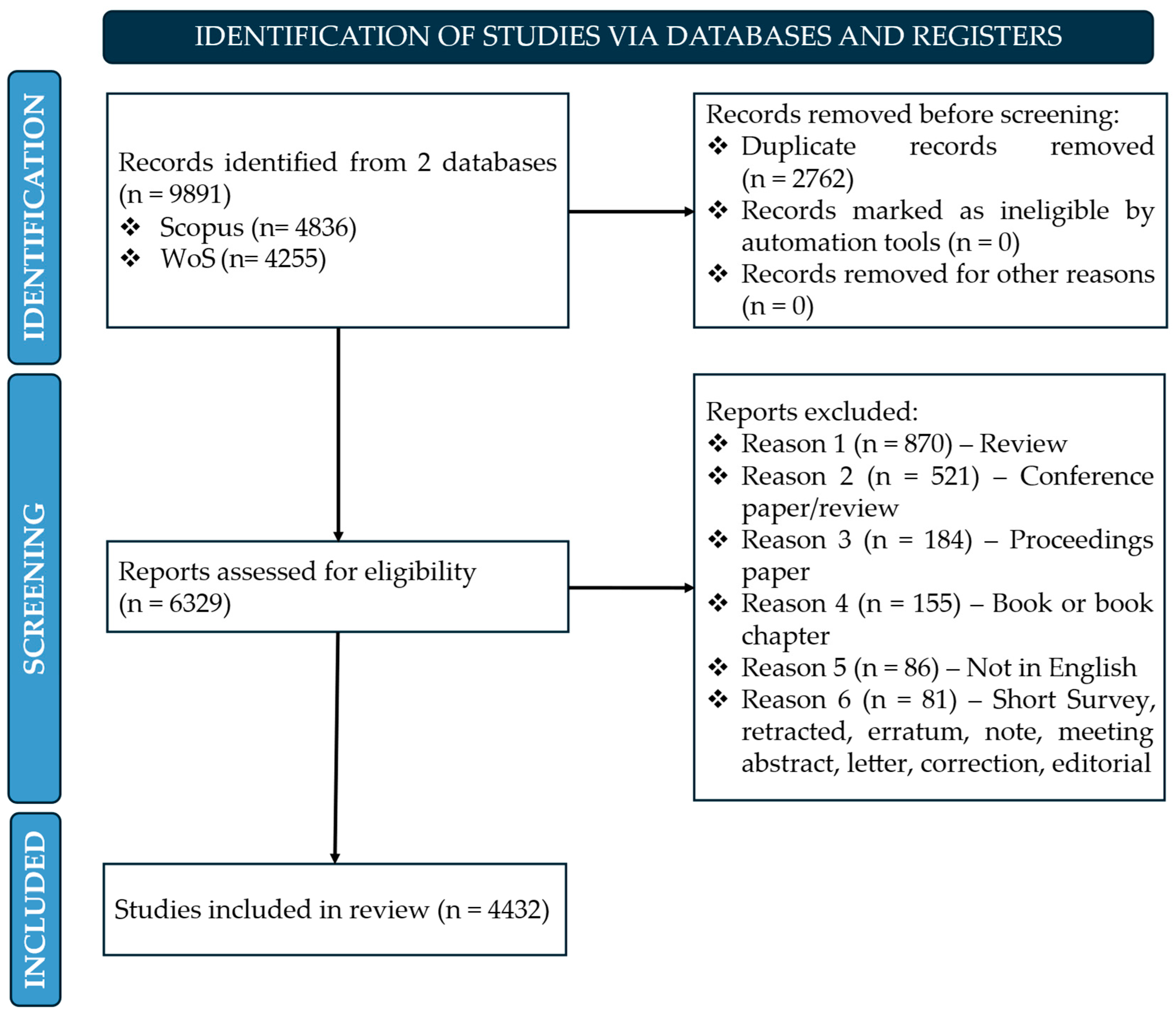

The identification and selection of records followed a structured workflow aligned with PRISMA 2020 principles, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The initial search across Scopus and WOS yielded 9891 records, which were merged into a single dataset. An automated de-duplication procedure removed 2762 duplicates, resulting in a preliminary corpus for screening. The remaining records of 6329 documents were then subjected to a multi-stage filtering process. First, documents were excluded based on type, including 870 review articles, 521 conference papers or conference reviews, 184 proceedings papers, 155 books or book chapters, and 81 non-research items such as editorials, letters, notes, corrections, or retractions. These exclusions were applied to ensure that the final dataset consisted exclusively of peer-reviewed research articles, which offer the highest degree of scientific rigor and are the standard source material for bibliometric analyses [

39,

40,

41]. A language filter removed an additional 86 non-English publications. After these exclusion criteria were applied, 4432 records were included in the review. The complete sequence of identification, screening, eligibility evaluation, and inclusion is summarized in the PRISMA flowchart shown in

Figure 2.

Following the completion of the PRISMA-based screening process, the resulting corpus of 4432 peer-reviewed research articles was prepared for bibliometric analysis. All records were standardized to harmonize metadata fields across Scopus and WoS, including author names, institutional affiliations, journal titles, and keyword variations. This pre-processing phase also involved the normalization of country names, the consolidation of synonymous keywords, and the correction of inconsistent or incomplete metadata to ensure reliable quantitative and network analyses. The final dataset was then analyzed using Bibliometrix 5.0, implemented in R version 4.5.2. All clustering, classification, and thematic analyses presented in the Results and Discussion sections were generated with these tools. In particular, keyword co-occurrence networks and strategic thematic maps were constructed through co-word analysis applied to author keywords and indexed terms. Thematic clusters were identified based on network connectivity, and their properties were quantified using centrality and density metrics. For graphical representation of trends and indicators, additional software tools were used: Origin 2020 Pro for advanced statistical plots and high-resolution charts, and Datawrapper for producing clean, publication-ready visualizations suitable for online dissemination.

Despite the robustness of the PRISMA-guided bibliometric framework adopted in this study, some limitations should be stated. First, the dataset was constructed from the Scopus and Web of Science databases; while these sources ensure high-quality and well-curated records, relevant studies indexed in other databases or preprint repositories may not be included. Second, the search strategy relies on predefined keywords, which may introduce a degree of selection bias despite the use of broad methodological descriptors designed to maximize inclusiveness. Third, only English-language publications were considered, potentially excluding relevant contributions published in other languages. These limitations are common to large-scale bibliometric analyses and should be considered when interpreting the quantitative results presented in this review.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Bibliometric Results

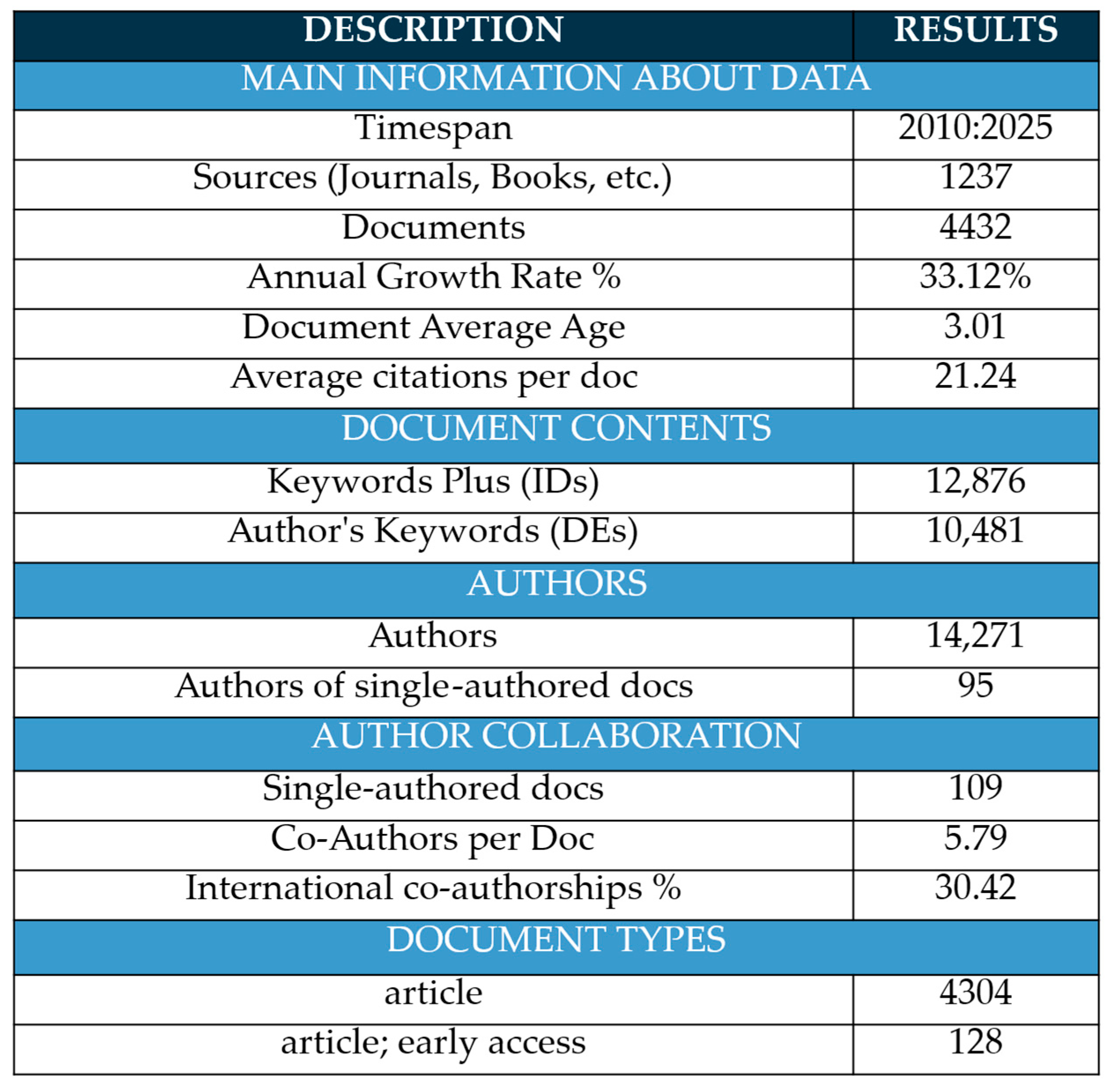

The descriptive bibliometric indicators presented in

Figure 3 offer an initial overview of the structural characteristics of the dataset and provide context for subsequent performance and network analyses. The corpus spans the period 2010–2025, comprising a total of 4432 peer-reviewed articles indexed in Scopus and WoS and distributed across 1237 distinct sources, which were scientific journals. The annual growth rate of 33.12% confirms the rapid and sustained expansion of research at the intersection of ML and nanomaterials, reflecting increasing adoption of data-driven methodologies within the materials science community.

Regarding document contents, the dataset includes more than 12,800 keywords and over 10,400 author keywords, highlighting the conceptual diversity of the field and the presence of multiple subdomains related to synthesis, characterization, modeling, and computational design of nanomaterials. Authorship statistics further demonstrate a substantial level of participation, with 14,271 contributing authors, yet only 109 single-authored documents, indicating that research in this area is predominantly collaborative. The average of 5.79 co-authors per article and an international co-authorship rate of 30.42% corroborate the highly cooperative and globally distributed nature of this research domain. In terms of document type, most contributions are research articles (4304), with 128 categorized as article–early access. This distribution aligns with the rigorous filtering applied during the PRISMA screening stage, which ensured that the dataset focused exclusively on peer-reviewed scientific publications.

The annual scientific production displayed in

Figure 4 reveals a clear exponential trajectory in research. Publication output remains modest between 2010 and 2016, with fewer than 100 articles per year, reflecting the early stages of integrating ML techniques into nanoscale material research. Beginning in 2017, however, the field enters a phase of accelerated growth, surpassing 200 annual publications by 2019 and showing a pronounced expansion from 2020 onward. This surge coincides with the widespread adoption of deep learning, the emergence of large-scale computational materials databases, and increased availability of high-performance computing infrastructures.

The steep growth observed between 2021 and 2024 (reaching 851 publications in 2024) highlights the rapid consolidation of the domain. The peak output reported for 2025 (950 publications) should be interpreted with caution, as these data correspond only to articles indexed up to November 2025; the full-year total is expected to be higher once indexing is complete. This partial-year effect also contributes to fluctuations in citation-based indicators for the most recent years.

Citation trends exhibit a complementary pattern. Mean total citations per article rise steadily throughout the 2010s, reflecting the increasing visibility and influence of foundational contributions. The decline observed after 2021 is a well-documented bibliometric effect resulting from recency bias: recent publications have had less time to accumulate citations, rather than reflecting diminished impact or quality. Thus, the combined evolution of publication volume and citation patterns underlines a high-impact interdisciplinary field.

3.2. Scientific Journal Impact

The distribution of publications across scientific journals provides comprehension into the disciplinary foundations and preferred dissemination channels of machine-learning-driven nanomaterial research.

Table 1 presents the ten most productive journals, revealing a marked concentration of output in a compact set of high-impact, multidisciplinary venues. According to Bradford’s Law, these journals form a distinct Zone 1, acting as the core publication cluster in the field. Scientific Reports, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, Nanoscale, ACS Nano, and Nature Communications occupy the top five positions, collectively accounting for more than 250 publications. Their prominence reflects the alignment between their editorial scope—materials science, nanotechnology, and computational methods—and the interdisciplinary nature of ML-based nanomaterial research.

Beyond productivity,

Table 2 provides a more nuanced understanding of journal influence by incorporating citation-based indicators and structural metrics (h-index, g-index, and m-index): (i) the h-index, which represents the number of publications that have received at least h citations, combining productivity and impact in a single measure; (ii) the g-index, which assigns greater weight to highly cited publications and captures how influential articles contribute disproportionately to a journal’s overall citation performance; and (iii) the m-index, a time-normalized version of the h-index that divides h by the number of years since the journal began publishing in the field, enabling more equitable comparisons across journals with different publication ages. Here, Nature Communications stands out with the largest number of publications (3368) and a strong combination of citation and index values, underscoring its role as a central platform for high-visibility research at the interface of data-driven modeling and nanoscale materials design. Similarly, ACS Nano and Advanced Materials exhibit high citation frequencies and substantial h- and g-indices, consistent with their established reputation for publishing impactful work in nanoscience, material synthesis, and computational materials engineering.

Other journals such as Nanoscale, Scientific Reports, and Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical demonstrate strong and sustained contributions, indicating that the field is supported by a diverse set of journals ranging from broad-scope open-access outlets to more specialized materials and chemical engineering venues. The presence of both generalist and domain-focused journals highlights the multidisciplinary of the field and the numerous application domains where ML is being employed, from materials discovery and optical design to catalysis and sensor development.

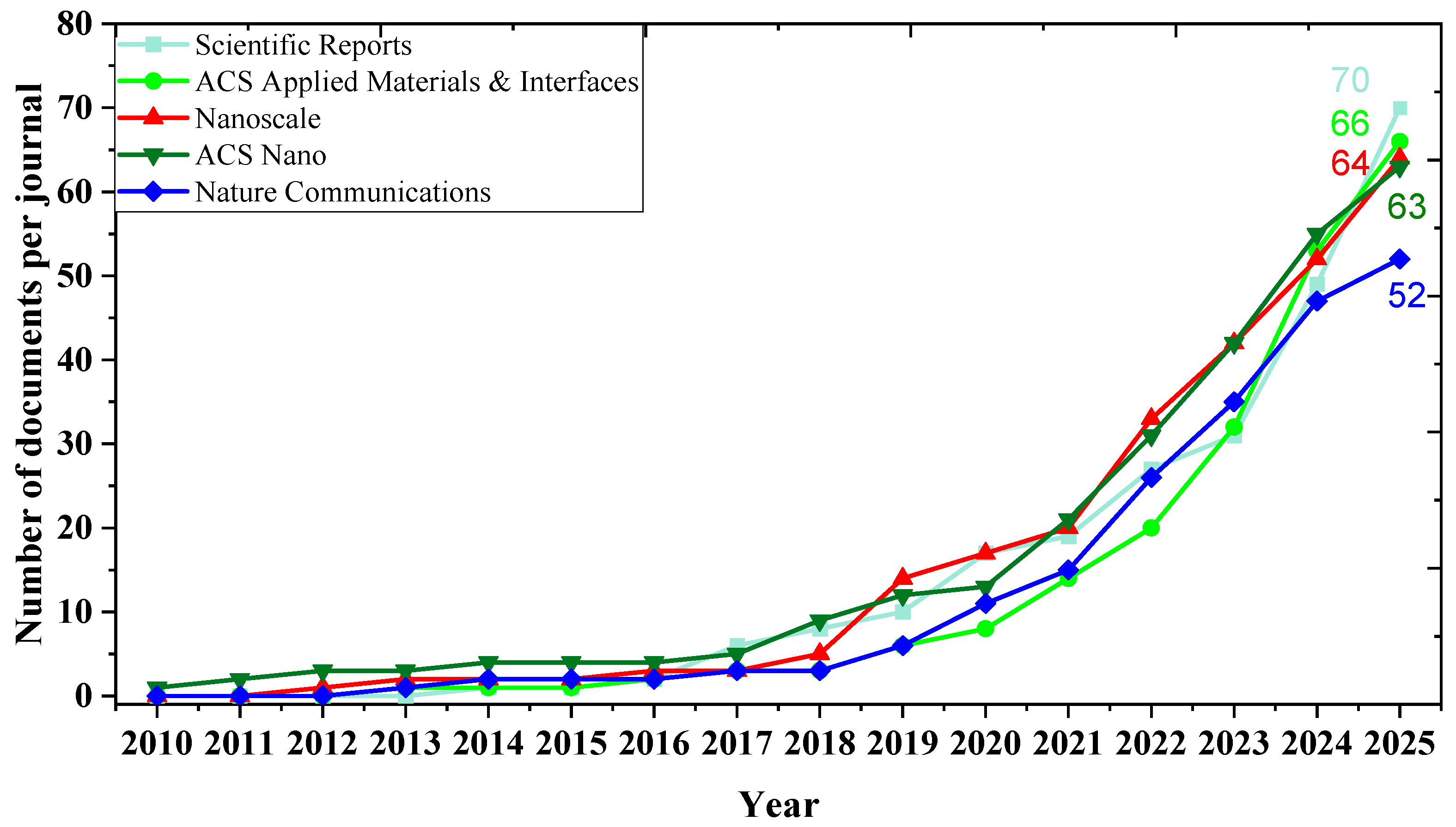

The temporal evolution of publication output across the top five journals, as depicted in

Figure 5, provides additional evidence of the accelerated growth and consolidation of research activity within the field. Between 2010 and 2016, output across the top journals remained limited, with most sources publishing fewer than five articles per year. A pronounced increase is observed from 2018 onward, with Scientific Reports, ACS Nano, Nanoscale, and ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces showing particularly strong growth. By 2025, several journals exceed 70 annual publications, highlighting the expansion of the research area.

Therefore, these patterns reveal an ecosystem of influential journals that both shape and reflect the evolution of ML in nanomaterial research. High-impact multidisciplinary titles catalyze visibility and citation impact, while specialized journals support the consolidation of emerging subfields and application domains.

3.3. Institutional and Country-Level Scientific Production

The analysis of institutional and national scientific production provides a thorough view of research capacity, collaboration networks, and geographic distribution. At the institutional level, the field is characterized by a strong presence of high-output organizations with well-established infrastructures in materials science and computational engineering. As shown in

Table 3, the Chinese Academy of Sciences leads with 234 publications, followed closely by the Islamic Azad University (205) and the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (182). These institutions reflect the strategic investment made by Asian and Middle Eastern countries in data-driven research, high-performance computing, and advanced experimental capabilities. Additional major contributors—including the University of California System, the Indian Institute of Technology System, and the U.S. Department of Energy—highlight the central role of large research systems and national laboratories in advancing ML-based approaches for materials discovery and nanoscale design. The presence of leading universities in Saudi Arabia (King Khalid University and King Saud University) and prominent Chinese institutions such as Zhejiang University further illustrates the rapidly expanding international research ecosystem supporting this domain.

The temporal evolution of institutional output presented in

Figure 6 reveals a consistent and marked dominance of the Islamic Azad University up to 2024, maintaining the highest productivity throughout this period. The Chinese Academy of Sciences displays a later but sharper growth trajectory; its publication output remains modest until around 2018 and subsequently increases exponentially, ultimately achieving the highest levels in 2025. In contrast, the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB), the University of California System, and the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) System also exhibit exponential growth patterns, although their publication volumes remain lower in recent years compared with those of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The country-level distribution of scientific output shown in

Table 4 reveals a highly uneven global landscape, with China emerging as the dominant contributor (1260 articles, 28.4%), supported by a very high number of single-country publications, indicating strong internal research capacity. The United States (479 articles) and India (446 articles) follow as major producers with more than 10% of total output each, while Iran also represents a significant contributor with 421 publications and a notable balance between national and international collaborations. A second tier of countries—including Korea, Germany, Australia, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Italy—shows moderate but meaningful activity, with publication shares between 1.9% and 3.7% and varying patterns of domestic versus international collaboration. Collectively, these results depict a research ecosystem dominated by a small group of highly productive nations, complemented by a diverse set of mid-level contributors.

The analysis of countries’ scientific production reveals a clear concentration of research output among a few leading nations, as stated in

Figure 7. China stands out decisively as the leading contributor, with 3381 publications, followed by the United States (1637), India (1342), and Iran (1115), together forming a dominant core responsible for most of the global output. Several other countries also make notable contributions, including Saudi Arabia (574), South Korea (546), Germany (353), the United Kingdom (282), Italy (275), and Australia (253). Additionally, Japan and Russia, with 253 and 251 publications, respectively, demonstrate substantial engagement in the field. In contrast, most remaining countries display minimal research output, with many producing fewer than ten publications. This pronounced imbalance likely reflects differences in national research investment, access to advanced experimental facilities and high-performance computing infrastructure, and the strategic prioritization of artificial intelligence and materials science within national research agendas. At the same time, the observed participation of a broader set of countries suggests a gradual expansion of the global research base, highlighting opportunities for capacity building, knowledge transfer, and strengthened international collaboration in regions with emerging or still developing activity in machine-learning-enabled nanomaterial research.

The institutional and country-level analyses reveal a research landscape dominated by a small group of highly productive organizations and nations, led by the Islamic Azad University and China. At the same time, a diverse set of emerging institutions and countries contributes to a steadily expanding global research base. This growing participation underscores both the maturation of machine-learning-driven nanomaterial research and the significant potential for broader international collaboration.

3.4. Highly Cited Documents

The most influential publications listed in

Table 5 illustrate the conceptual breadth and methodological impact of ML within nanomaterial research. The highest-cited works—such as those by Malkiel et al. [

42], Chen et al. [

43], and Wiecha et al. [

44]—have driven major advances in deep learning-based inverse design, nano-optics, and photonics, reflecting the early dominance of optical and plasmonic applications in the field. Other key contributions, including studies on memristive neuromorphic devices, quantitative nanostructure–activity relationships, autonomous materials discovery, and ML-enhanced interatomic potentials, demonstrate the field’s expansion toward catalysis, sensing, adsorption, and multiscale materials modeling. Overall, these highly cited documents highlight the interdisciplinary character and growing scientific influence of machine-learning-enabled approaches in nanomaterial discovery and design.

4. Discussion

4.1. Tendencies in Top Publications

The twelve most highly cited publications (

Table 5) reveal four overarching scientific clusters that define the intellectual trajectory of machine-learning-driven nanomaterial research: (i) ML-based nanophotonics, (ii) ML-enhanced chemical functionality and sensing, (iii) ML-accelerated predictive simulations, and (iv) intelligent nanodevices and autonomous discovery. These were grouped into four clusters based on shared research focus and methodological similarity, and their relative influence was evaluated using citation impact and conceptual relevance. These clusters reflect how ML has been adopted to solve high-impact problems across optics, chemistry, sensing, multiscale modeling, and autonomous experimentation.

The first and most influential cluster comprises publications applying ML to inverse design and computational nanophotonics, demonstrating the transformative impact of deep learning on optical device engineering. Malkiel et al. pioneered data-driven plasmonic nanostructure design by training neural networks to map optical spectra directly to geometry, eliminating the need for iterative full-wave simulations [

42]. Chen et al. advanced this approach with physics-informed neural networks capable of solving Maxwell-based inverse problems while enforcing physical constraints, achieving solver-level accuracy at dramatically reduced computational cost [

43]. Wiecha et al. expanded the methodological landscape by introducing a comprehensive deep-learning framework for forward modeling, inverse scattering, and generative design in nanophotonics, showing how convolutional and generative architectures can efficiently explore complex, high-dimensional design spaces [

44]. Complementing these contributions, Tahersima et al. demonstrated breakthrough performance in the inverse design of integrated photonic power splitters, achieving orders-of-magnitude speedups and robust generalization across diverse device geometries [

50]. Collectively, these works established nanophotonics as one of the earliest and most successful domains for machine-learning-enabled design acceleration, clearly illustrating how neural network models can augment or replace computationally intensive electromagnetic solvers.

The second cluster encompasses publications applying ML to chemically functional nanomaterials, demonstrating the capacity of ML to enhance adsorption, catalysis, sensing, and porous material design. Jawad et al. used ML-driven modeling to optimize the performance of mesoporous activated carbons derived from biomass, providing mechanistic insight into adsorption efficiency and guiding the rational design of high–surface area materials [

46]. Zhang et al. [

14] integrated metal-oxide-modified graphene sensors with neural network models to discriminate and quantify formaldehyde and ammonia concentrations, showing how ML significantly improves signal interpretation and selectivity in nanosensor arrays [

47]. Gao et al. advanced the field of catalysis by using machine-learned insights to overcome traditional adsorption-energy scaling limitations, achieving enhanced electrocatalytic nitrate reduction on CuPd nanocubes and demonstrating how ML can reveal previously inaccessible mechanistic relationships [

49]. Kim et al. applied artificial neural networks to inverse-design porous materials, uncovering complex structure–property correlations that govern adsorption and transport phenomena in nanoporous architectures [

53]. These works illustrate that ML serves as a predictive tool and as a powerful engine for improving functionality, uncovering chemical mechanisms, and accelerating the design of high-performance nanomaterials across catalysis, sensing, and adsorption.

The third cluster comprises influential contributions focused on ML for predictive modeling and multiscale simulation, illustrating how ML increasingly complements or replaces conventional physics-based computational methods. Fourches et al. introduced one of the earliest quantitative nanostructures–activity relationship frameworks, using ML to correlate nanomaterial descriptors with physicochemical and biological properties, thereby laying the foundations for data-driven nano-QSAR and predictive toxicology [

48]. Mortazavi et al. advanced the field by developing ML-driven interatomic potentials capable of reproducing density-functional-theory accuracy while enabling simulations of graphene/borophene heterostructures across scales that would be computationally prohibitive with traditional methods [

52]. Together, these works demonstrate the growing importance of ML-based surrogate models in extending the reach of multiscale simulations, accelerating parameter exploration, and enabling accurate predictions for complex nanoscale systems.

Finally, the fourth cluster encompasses pioneering efforts in ML-integrated nanodevice engineering and autonomous materials discovery. Querlioz et al. explored the resilience of spiking neural networks implemented with memristive nanodevices, showing how ML concepts can be embedded directly into nanoscale hardware to mitigate device variability and noise [

45]. Kusne et al. introduced an on-the-fly Bayesian active learning framework capable of steering experimental measurements in real time, enabling closed-loop, autonomous materials exploration [

51]. These studies represent the frontier of intelligent laboratory automation and neuromorphic device integration, marking the evolution of ML in nanomaterial research from computational prediction to hardware implementation and self-driving experimental workflows.

This section shows that ML has evolved from a promising computational aid into a core driver of innovation across nanomaterial research. Despite the diversity of applications (spanning photonics, catalysis, sensing, multiscale modeling, and autonomous laboratories) these works share a unifying trajectory: they use data-driven methods to overcome long-standing bottlenecks in design, prediction, and experimentation. Their collective influence demonstrates how ML is reshaping the way nanomaterials are conceived, optimized, and understood, shifting the field toward faster, more predictive, and increasingly automated discovery pipelines.

4.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence Clustering

The keyword co-occurrence network displayed in

Figure 8 reveals the conceptual organization of the field through four major thematic keywords clusters, each corresponding to a distinct research orientation within ML-enabled nanomaterials. Here, four clusters have been identified: (i) Nanoparticle synthesis and characterization with ML (red cluster); (ii) ML-based optimization and property prediction in nanocomposites (green cluster); (iii) modeling carbon-based nanomaterials via ML (blue cluster); and (iv) ML applications in nanoscale chemistry, catalysis, and thermal processes (purple cluster).

The red cluster centers on nanoparticle synthesis and characterization with ML to accelerate the wet-chemical synthesis and analysis of nanoparticles, where controlling size, shape, and properties is traditionally laborious. A review published by Tao et al. (2021) [

31] showcases how ML can optimize nanoparticle syntheses to achieve precise morphology and surface chemistry. This work surveys ML algorithms for nanoparticle production and highlights methods to gather large datasets for model training, covering cases from semiconductor quantum dots to metal and carbon nanoparticles [

31]. As a representative original study, Mekki-Berrada et al. (2021) demonstrated a closed-loop Bayesian optimization strategy to tune a microfluidic silver nanoparticle synthesis for target optical absorbance spectra [

54]. By combining Gaussian-process regression with a neural network, their framework rapidly converged on reaction conditions yielding a desired plasmonic peak within around 120 experiments, illustrating how ML-guided experimentation can efficiently optimize nano-synthesis and unveil how precursors and process parameters influence nanoparticle optical properties. Complementing these, a recent perspective by Park et al. (2023) in Matter describes integrating robotic synthesis, real-time characterization, and ML into a self-driving lab for nanoparticles [

55].

The green cluster focuses on ML-driven design of nanocomposites, materials where nanoscale fillers (nanotubes, clays, graphene, etc.) are embedded in matrices to tailor properties. In this regard, Champa-Bujaico et al. (2022) outline how techniques like artificial neural networks, genetic algorithms, and Gaussian processes are applied to predict and optimize polymer nanocomposite performance [

56]. ML enables inverse design of nanocomposites by identifying optimal filler content or surface functionalization to maximize targeted properties, which would be infeasible via exhaustive experiments. For example, Gu et al. (2018) pioneered a data-driven approach to hierarchical composite design, using an ML algorithm trained on thousands of finite-element simulations to discover new microstructural patterns [

57]. Likewise, in the realm of property prediction, Doan Tran et al. (2020) introduced the Polymer Genome project, which built high-accuracy ML models for polymer (and nanocomposite) properties using a large materials database [

58]. Such models empower researchers to screen myriad nanocomposite formulations virtually before syntheses.

The blue cluster focuses on modeling carbon-based nanomaterials using ML, including carbon nanotubes and graphene, typically to predict their electrical, thermal, or mechanical behavior. On the one hand, Rao et al. (2021) developed an ML-driven experimental planner to selectively grow single-walled carbon nanotubes in two narrow diameter ranges (~0.92 nm and ~1.06 nm), confirmed by Raman spectroscopy [

59]. On the other hand, Alred et al. (2018), for example, trained a neural network to predict the electron density distribution in covalently cross-linked CNT frameworks, accelerating quantum calculations for these complex nanostructures [

60]. In the case of graphene, ML has enabled the inverse design of structure for targeted conductivity, for instance, Wan et al. (2020) applied a ML model to discover porous graphene microstructures with ultra-low lattice thermal conductivity, guiding where to introduce nanoscale holes to scatter phonons [

61]. Similarly, a recent study by Wang et al. combined ML with molecular dynamics to identify an optimal twist-stacking sequence of multilayer graphene that minimizes cross-plane thermal conduction via phonon localization [

62], underscoring how ML can pinpoint subtle structural configurations for extreme property tuning. These studies all leverage data-driven models to explore large parametric spaces (growth conditions, defect patterns, inter-tube bonding) and reveal optimal solutions for carbon-based nanomaterials that were previously unattainable through conventional methods.

The purple cluster encompasses ML use in nanoscale chemical reactions, catalysis, and nanomaterial applications in thermal or environmental contexts. Tran & Ulissi (2018) trained a model on a limited set of DFT adsorption energies, enabling their algorithm to predict promising alloy compositions and steer new calculations toward the most promising candidates [

63]. Moreover, Toyao et al. emphasize how data-driven models plus domain knowledge can uncover complex structure–activity relationships in heterogeneous catalysts that traditional intuition might miss, thereby guiding the design of improved nanocatalysts for fuel cells, CO

2 conversion, and pollution mitigation [

64]. A striking practical demonstration came from Zhong et al. (2020), who reported an ML-accelerated search for multi-component electrocatalysts by integrating an active-learning algorithm with high-throughput DFT, they rapidly identified a novel Cu–Al alloy as an outstanding catalyst for CO

2-to-ethylene conversion [

65]. As stated, this cluster shows a unifying theme: data-driven insight into complex chemical reaction systems at the nanoscale. By learning from quantum simulations or experimental data, ML models can identify optimal catalysts or process parameters far more quickly than conventional trial-and-error in designing high-entropy alloy catalysts.

4.3. Strategic Thematic Mapping

Figure 9 presents a thematic map plotting the centrality (relevance) and density (development) of keyword clusters, offering a strategic overview of how research topics in ML for nanomaterials are positioned within the field. This two-dimensional representation enables the classification of themes into four quadrants: motor themes, niche themes, basic themes, and emerging or declining themes, each reflecting different degrees of maturity and connectivity.

In the upper-right quadrant, the cluster comprising neural network, chemistry, nanotechnology, and algorithm emerges as both central and highly developed, a motor theme. This indicates that these concepts represent the driving force of the field, combining methodological sophistication with wide applicability. Their strong internal cohesion and influence across other topics confirm their role as core enablers in current ML-guided nanomaterial research, often underlying both experimental and modeling efforts.

The green cluster located in the upper-central zone contains terms like artificial neural network, optimization, adsorption, and water. This group remains highly relevant with considerable structural coherence, suggesting a specialized but influential research stream. These topics align with studies on ML-enhanced adsorption modeling, often related to water purification, environmental remediation, and porous material design, pointing to robust subfields that integrate both experimental data and optimization algorithms.

In contrast, the blue cluster on the bottom-right, that is in basic themes zone, features terms such as prediction, performance, graphene oxide, graphene, and carbon nanotubes. Although these themes are foundational and widely connected across the field (high centrality), they exhibit relatively lower internal development (density). This implies that while these topics are integral to the research landscape, they serve as general entry points or supporting elements rather than self-contained research niches. Their positioning reflects their utility across various applications—from sensors and electronics to thermal transport—but also suggests opportunities for deeper methodological refinement.

The red cluster, situated in the lower-left quadrant, that is an emerging or declining theme, includes terms like nanoparticles, nanomaterials, ML, artificial intelligence, model, and size. This grouping reflects broad but currently less structurally cohesive topics. The combination of general ML terms with core nanoscience concepts suggests an ongoing reconfiguration, possibly due to diversification into more specialized subdomains or a shift toward more integrated, application-specific lines of inquiry. Their lower density may also indicate the fragmentation or redefinition of research directions as the field matures.

Finally, the purple cluster in the top-left quadrant comprises terms such as memristor, memory, neuromorphic computing, and resistive switching, in the niche themes zone. These represent highly specialized and methodologically rich areas with limited cross-topic connectivity. Despite their low centrality, their high-density points to internally consistent research fronts. Such themes, particularly in neuromorphic materials and computational memory devices, suggest advanced yet isolated investigations that could potentially become more integrated into mainstream nanomaterial design workflows in the future.

The strategic thematic mapping shows a maturing research field structured around a set of motor themes (e.g., neural networks and data-driven chemistry) that act as core enablers, alongside highly connected basic themes related to carbon-based nanomaterials. At the same time, emerging and niche themes reflect increasing specialization and the exploration of new application-oriented directions, indicating a progressive diversification of machine-learning-enabled nanomaterial research.

4.4. Outlook and Prospects

Based on the bibliometric trends and thematic structures identified in this review, this section outlines key future research directions, highlighting emerging methodological, experimental, and interdisciplinary opportunities for advancing machine-learning-driven nanomaterial discovery and design. As ML continues to mature and integrate with nanomaterials science, the field is poised for several transformative developments. First, the rise of autonomous laboratories (combining robotics, real-time analytics, and ML) will likely accelerate the pace of materials discovery by enabling self-driving experimentation. This paradigm allows iterative synthesis, characterization, and optimization without human intervention, potentially compressing years of trial-and-error research into weeks. Early demonstrations in nanoparticle synthesis and photonics have already validated this approach, and broader adoption is anticipated as infrastructure and algorithms become more accessible.

Second, the fusion of multi-modal data sources such as microscopy, spectroscopy, simulation outputs, and experimental metadata will become a central focus. ML models capable of leveraging such heterogeneous data will improve generalizability and uncover hidden correlations across length scales and modalities. This evolution requires more standardized data sharing practices and interoperable ontologies, which are still nascent in the nanoscience community.

Third, explainability and interpretability of ML models remain a critical frontier. As many of the most powerful algorithm’s function as black boxes, their adoption in high-stakes nanomaterial design (e.g., biomedical, environmental, or electronic applications) depends on improved transparency. Future work will increasingly incorporate interpretable architecture, causal inference, and uncertainty quantification to enable trust and regulatory compliance.

Moreover, integration with first-principles physics through hybrid models (e.g., physics-informed neural networks) offers a promising strategy for reducing data requirements while preserving scientific rigor. These approaches can enforce physical constraints, guide learning in low-data regimes, and provide actionable insights into underlying mechanisms.

Finally, a more inclusive and globally distributed research ecosystem is needed to bridge the stark disparities revealed in this bibliometric mapping. Increased collaboration across countries and institutions, supported by open-access platforms, multilingual resources, and shared datasets, could democratize innovation and foster new lines of inquiry in underrepresented regions.

5. Conclusions

This bibliometric review provides comprehensive mapping of scientific production at the intersection of machine learning (ML) and nanomaterial research over the past fifteen years, revealing an exponentially expanding and increasingly influential domain. Through a PRISMA-guided workflow and the integration of data from Scopus and Web of Science, a curated dataset of 4432 peer-reviewed articles was analyzed using advanced performance indicators, network analyses, keyword clustering, and strategic thematic mapping. The results highlight the exponential growth of publications since 2017, driven by the widespread adoption of deep learning techniques, the emergence of large materials databases, and improved computational capabilities. Leading journals, institutions, and countries (particularly China, the United States, India, and Iran) form a highly productive global research core, although notable disparities persist across regions.

The co-occurrence and thematic analyses show that research activity is organized around four major clusters: (i) ML-assisted nanoparticle synthesis and characterization; (ii) ML-driven design and optimization of nanocomposites; (iii) data-driven modeling of carbon-based nanomaterials; and (iv) ML-enhanced nanoscale chemistry, catalysis, and environmental applications. These clusters demonstrate how ML has transitioned from a computational support tool to a central driver of innovation in nanomaterial discovery, property prediction, and functional optimization. At the same time, the presence of emerging themes such as autonomous experimentation, neuromorphic nanodevices, and hybrid physics-informed models indicate the consolidation of new research frontiers that integrate ML models more deeply into experimental workflows.

Despite this progress, the mapping reveals several critical challenges. Research output is concentrated within a limited number of countries and institutions, highlighting the need for capacity-building and broader international collaboration. Data heterogeneity, and limited standardization also remain major barriers to reproducibility and model generalization. Moreover, the predominance of black-box deep learning methods raises concerns regarding interpretability, transparency, and trustworthiness, particularly in high-impact applications such as nanomedicine, energy materials, and environmental nanotechnology.

Finally, future work should focus on expanding multimodal datasets, integrating explainable AI techniques, promoting fair data practices, and advancing autonomous laboratory systems capable of accelerating discovery cycles. These efforts will shape the next generation of ML-guided nanomaterial design and contribute to a more efficient, interpretable, and global research ecosystem.