N-Gram and RNN-LM Language Model Integration for End-to-End Amazigh Speech Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

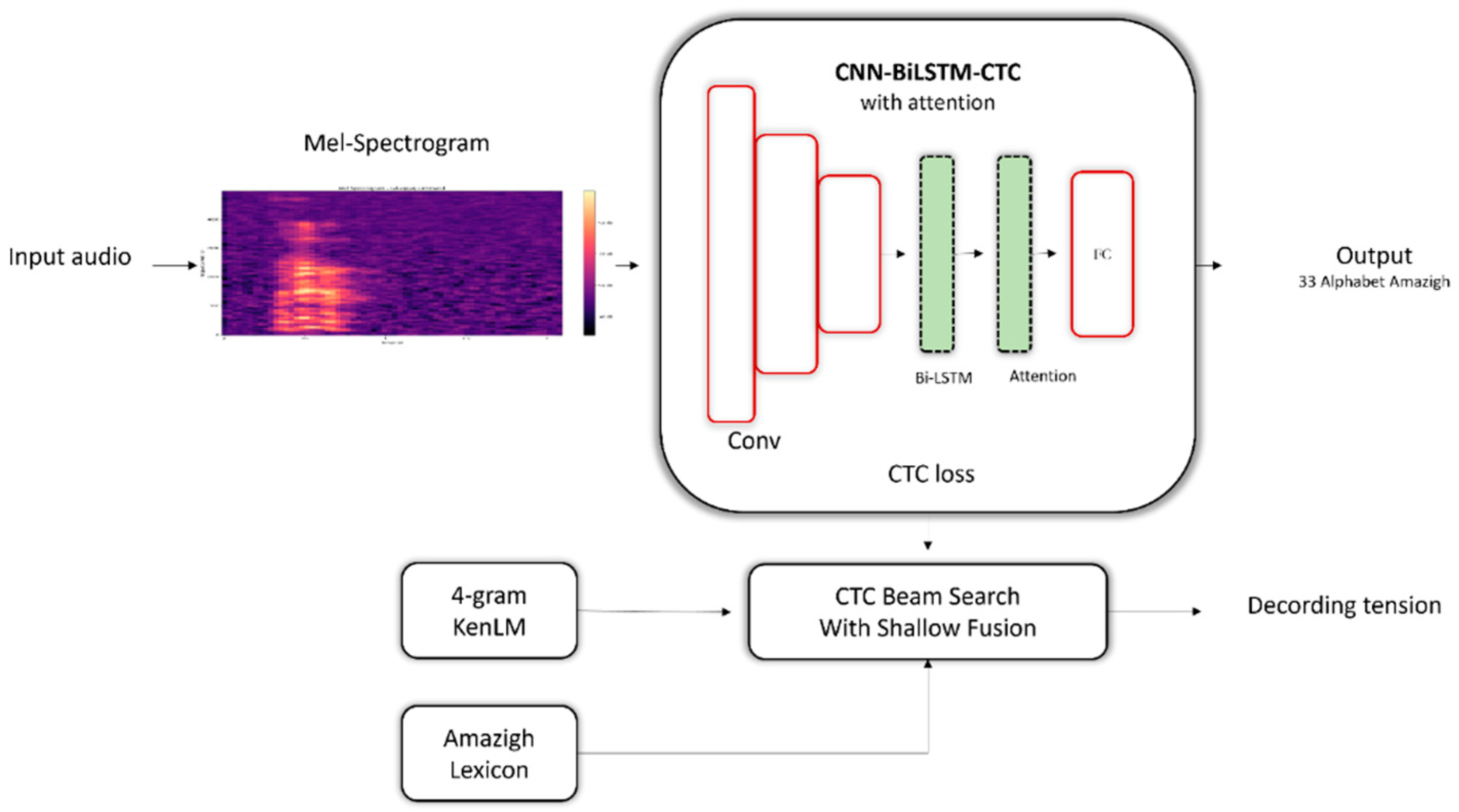

- Development of a baseline ASR system for the Amazigh language based on a convolutional neural network, bidirectional long short-term memory, and connectionist temporal classification model CNN-BiLSTM-CTC enhanced with an attention mechanism, designed for recognizing the 33-letter Tifinagh alphabet.

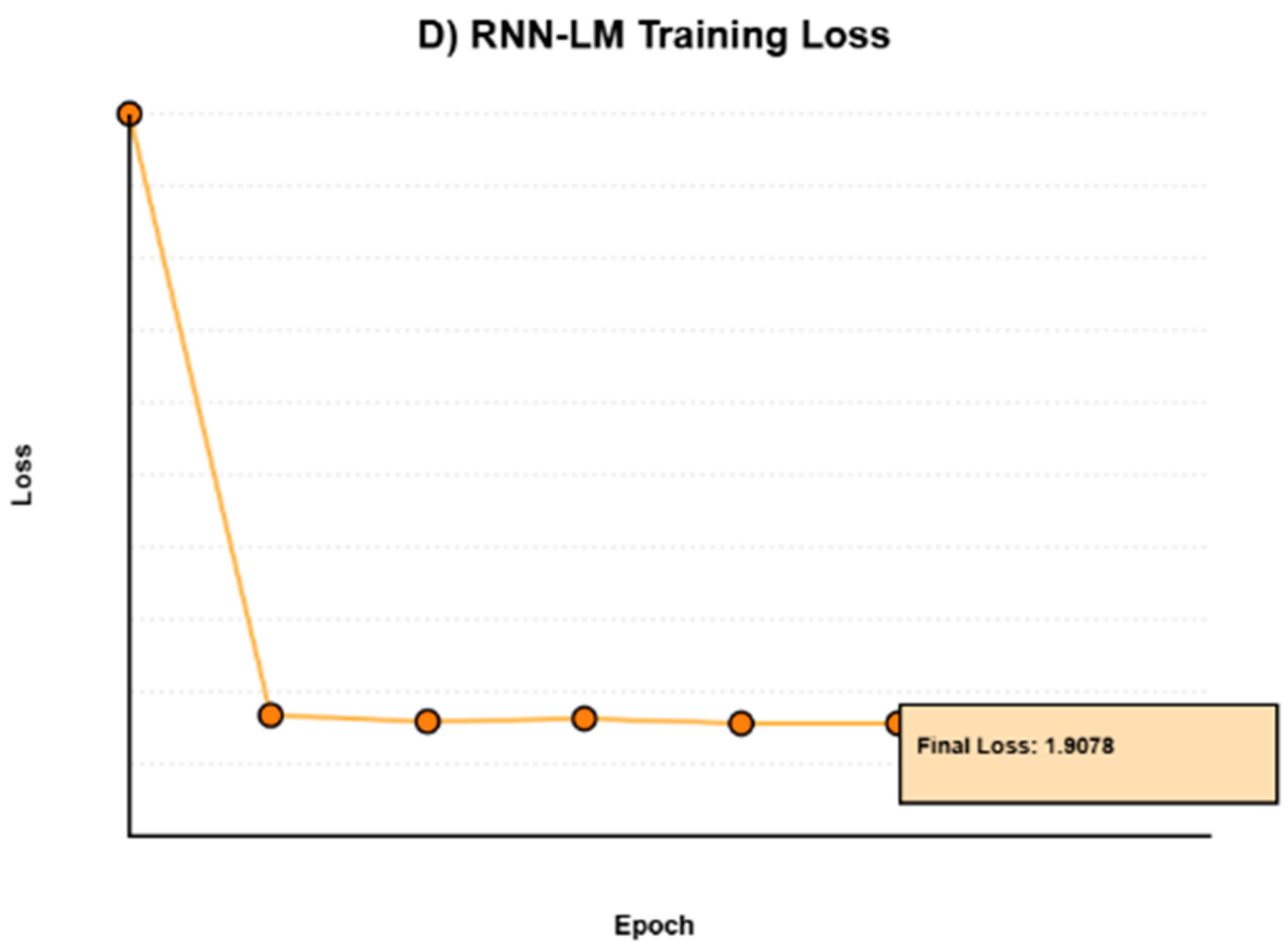

- Compact RNN-LM architecture optimized for low-resource scenarios.

- Integration of an external N-gram language model via shallow fusion during decoding, effectively combining acoustic and linguistic knowledge and improving recognition accuracy.

- Integration of an external recurrent neural network language model (RNN-LM) via shallow fusion.

- Utilization of the Tifdigit corpus, comprising 8940 speech samples recorded by 50 native speakers, as a key resource in the study of low-resource languages such as Amazigh.

- First comprehensive comparison of four decoding methods for Amazigh ASR. an in-depth analysis was carried out of decoding strategies and error patterns, including word-level improvements, error correction mechanisms (insertion, substitution, and deletion), and syllabic structures.

2. Motivation

3. Related Works

4. Methodology

4.1. Principle of Speech Recognition (ASR)

- P(X|Y): describes the probability of an audio signal given a sequence of words (acoustic model).

- P(Y): expresses the probability of a sequence of words in the language (language model).

4.2. Language Models Used in This Work

N-Gram Model

- n = 1: unigram model.

- n = 2: bigram model.

- n = 3: trigram model

4.3. Shallow Fusion Strategy Connectionist Temporal Classification

4.4. Shallow Fusion Strategy

4.5. CNN-BiLSTM-CTC Architecture

5. Amazigh Language

- 27 Consonants labial: ⴼ, ⴱ, ⵎ dental ⵜ, ⴷ, ⵟ, ⴹ, ⵏ, ⵔ, ⵕ, ⵍ alveolar ⵙ, ⵣ, ⵚ, ⵥ palatal ⵛ, ⵊ velar ⴽ, ⴳ labiovelar ⴽⵯ, ⴳⵯ uvular ⵇ, ⵅ, ⵖ pharyngeal ⵃ, and ⵄ laryngeal ⵀ;

- 2 Semi-consonants: ⵢ and ⵡ;

- 4 Vowels: full vowel ⴰ, ⵉ, and ⵓ, neuter vowel (schwa) ⴻ.

6. Language Model Integration for Amazigh Speech Recognition System

6.1. System Description

6.2. Corpus

6.3. Language Model

6.4. Decoding Strategies

6.5. Evaluation Metrics

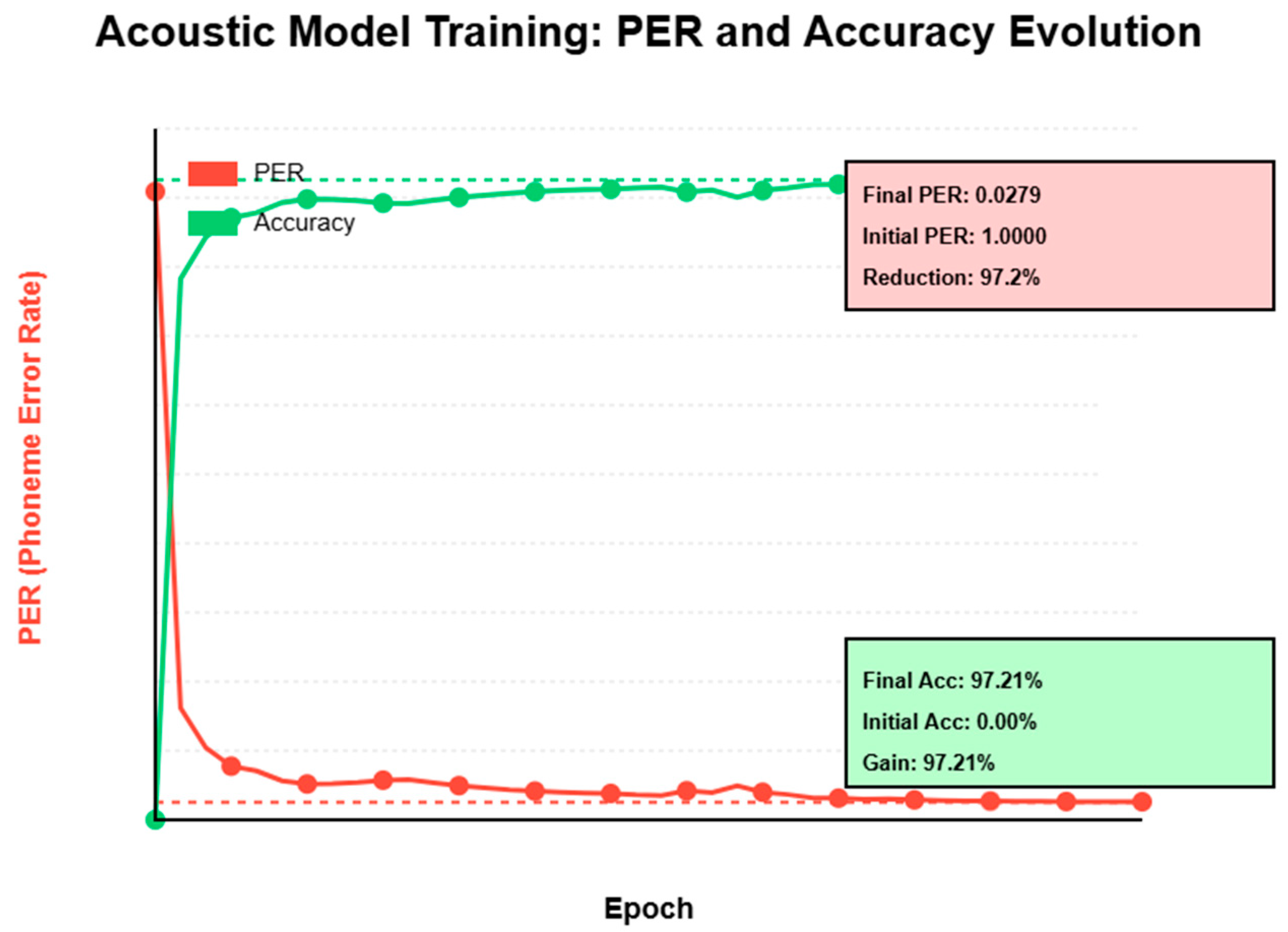

7. Results and Discussion

7.1. Word-Level Performance Analysis

- A high phonemic distinctiveness: the vowels /i/ and /u/ in these words are at opposite ends of the vowel spectrum.

- Simple syllabic structures (CV/CVV): ‘yi’, ‘you’, and ‘yef’ have limited coarticulation and long, stable vowels, which facilitates the extraction of acoustic features.

- Low lexical confusability: their closest phonetic neighbors are at an editing distance of at least 2, unlike ambiguous pairs such as ‘yas’ and ‘yaz’ (distance 1, PER = 0.0347).

- Therefore, the CNN-BiLSTM-CTC model effectively captures the spectro-temporal characteristics of these distinctive and simple words. Linguistic strategies become particularly useful in more complex phonetic contexts.

7.2. Error Correction Mechanisms

7.3. Influence of Language Models Across Amazigh Syllabic Structures

7.4. Comparative Analysis with State-of-the-Art

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition System |

| HMMs | Hidden Markov Model |

| E2E | End-to-End |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| CTC | Connectionist Temporal Classification |

| LM | Language Model |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

References

- Li, J. Recent advances in end-to-end automatic speech recognition. APSIPA Trans. Signal Inf. Process. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandji, A.K.; Ba, C.; Ndiaye, S. State-of-the-Art Review on Recent Trends in Automatic Speech Recognition. In International Conference on Emerging Technologies for Developing Countries; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhavalkar, R.; Hori, T.; Sainath, T.N.; Schlüter, R.; Watanabe, S. End-to-end speech recognition: A survey. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 32, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slam, W.; Li, Y.; Urouvas, N. Frontier research on low-resource speech recognition technology. Sensors 2023, 23, 9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdou Mohamed, N.; Allak, A.; Gaanoun, K.; Benelallam, I.; Erraji, Z.; Bahafid, A. Multilingual speech recognition initiative for African languages. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2024, 20, 3513–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkani, F.; Hamidi, M.; Laaidi, N.; Zealouk, O.; Satori, H.; Satori, K. Amazigh speech recognition based on the Kaldi ASR toolkit. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2023, 15, 3533–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulal, H.; Hamidi, M.; Abarkan, M.; Barkani, J. Amazigh CNN speech recognition system based on Mel spectrogram feature extraction method. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2024, 27, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulal, H.; Bouroumane, F.; Hamidi, M.; Barkani, J.; Abarkan, M. Exploring data augmentation for Amazigh speech recognition with convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2025, 28, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telmem, M.; Laaidi, N.; Ghanou, Y.; Hamiane, S.; Satori, H. Comparative study of CNN, LSTM and hybrid CNN-LSTM model in Amazigh speech recognition using spectrogram feature extraction and different gender and age dataset. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2024, 27, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telmem, M.; Laaidi, N.; Satori, H. The impact of MFCC, spectrogram, and Mel-Spectrogram on deep learning models for Amazigh speech recognition system. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sui, M.; Wang, Z. Integrated method of deep learning and large language model in speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), Xi’an, China, 31 July 2024–2 August 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, N.M.T.; Sy, T.H. Improving speech recognition with prompt-based contextualized asr and llm-based re-predictor. In Interspeech; International Speech Communication Association (ISCA): Kos, Greece, 2024; Volume 2024, pp. 737–741. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Zhang, R. Large language models for disease diagnosis: A scoping review. Npj Artif. Intell. 2025, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telmem, M.; Ghanou, Y. The convolutional neural networks for Amazigh speech recognition system. TELKOMNIKA 2021, 19, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhamadiyev, A.; Mukhiddinov, M.; Khujayarov, I.; Ochilov, M.; Cho, J. Development of language models for continuous Uzbek speech recognition system. Sensors 2023, 23, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Venkateswaran, N.; Le Ferrand, É.; Prud’hommeaux, E. How important is a language model for low-resource ASR. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Anoop, C.S.; Ramakrishnan, A.G. CTC-based end-to-end ASR for the low resource Sanskrit language with spectrogram augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 National Conference on Communications (NCC), Kanpur, India, 27–30 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mamyrbayev, O.Z.; Oralbekova, D.O.; Alimhan, K.; Nuranbayeva, B.M. Hybrid end-to-end model for Kazakh speech recognition. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2023, 26, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labied, M.; Belangour, A.; Banane, M. Delve deep into End-To-End Automatic Speech Recognition Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (iSemantic), Semarang, Indonesia, 16–17 September 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, D.; Ohta, K.; Nishimura, R.; Ogawa, A.; Kitaoka, N. Advanced language model fusion method for encoder-decoder model in Japanese speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Tokyo, Japan, 14–17 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- El Ouahabi, S.; El Ouahabi, S.; Atounti, M. Comparative Study of Amazigh Speech Recognition Systems Based on Different Toolkits and Approaches. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2023; Volume 412, p. 01064. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge, J.; Gimenez, A.; Silvestre-Cerda, J.A.; Civera, J.; Sanchis, A.; Juan, A. Live streaming speech recognition using deep bidirectional LSTM acoustic models and interpolated language models. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 30, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Phadikar, S.; Bera, S.; Dey, T.; Nandi, U. Isolated word recognition based on a hyper-tuned cross-validated CNN-BiLSTM from Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 17309–17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, M.K.; Hock, G.C.; Abdulrazzak, H.N. Mathematical Modelling of Engineering Problems. Int. Inf. Eng. Assoc. 2025, 12, 1893–1910. Available online: http://iieta.org/journals/mmep (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Xue, J.; Zheng, T.; Han, J. Exploring attention mechanisms based on summary information for end-to-end automatic speech recognition. Neurocomputing 2021, 465, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawdi, A. MultiheadSelfAttention vs, Traditional Encoders: A Benchmark Study on Precision and Recall in Tajweed Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA), Ibb, Yemen, 5–6 August 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Addarrazi, I.; Zealouk, O.; Satori, H.; Satori, K. The Hmm Based Amazigh Digits Audiovisual Speech Recognition System. Math. Stat. Eng. Appl. 2022, 71, 2261–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Ouhnini, A.; Aksasse, B.; Ouanan, M. Towards an automatic speech-to-text transcription system: Amazigh language. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satori, H.; ElHaoussi, F. Investigation Amazigh speech recognition using CMU tools. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2014, 17, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.A.M. Low-Resource Automatic Speech Recognition Domain Adaptation: A Case-Study in Aviation Maintenance. Doctoral Dissertation, Purdue University Graduate School, West Lafayettem, IN, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Samin, A.M.; Kobir, M.H.; Kibria, S.; Rahman, M.S. Deep learning based large vocabulary continuous speech recognition of an under-resourced language Bangladeshi Bangla. Acoust. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Cho, E.; Kim, J.H. Integration of WFST Language Model in Pre-trained Korean E2E ASR Model. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2024, 18, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar]

| ⴰ a yaa CVV | ⴱ b yab CVC | ⴳ g yag CVC | ⴳⵯ gw yagw CVCC | ⴷ d yad CVC | ⴹ ḍ yadd CVCC | ⴻ e yey CVC | ⴼ f yaf CVC | ⴽ k yak CVC | ⴽⵯ kw yakw CVCC | ⵀ h yah CVC |

| ⵃ ḥ yahh CVCC | ⵄ ɛ yaε CVC | ⵅ x yax CVCC | ⵇ q yaq CVC | ⵉ i yi CVC | ⵊ j yaj CVC | ⵍ l yal CVC | ⵎ m yam CVC | ⵏ n yan CVC | ⵓ u you CVV | ⵔ r yar CVC |

| ⵕ ṛ yarr CVCC | ⵖ γ yiγ CVC | ⵙ s yas CVC | ⵚ ṣ yass CVCC | ⵛ c yach CVCC | ⵜ t yat CVC | ⵟ ṭ yatt CVCC | ⵡ w yaw CVC | ⵢ y yay CVC | ⵣ z yaz CVC | ⵥ ẓ yazz CVCC |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number of audio files | 21,500 |

| Base duration | 2 h 18 min |

| Sampling | 16 kHz, 16 bits |

| Wave format | Mono, wav |

| Corpus | 33-letter Amazigh alphabet |

| Speakers | 50 (50% male and 50% female) |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of LSTM layers | 1 |

| Embedding dimension | 64 |

| Classifier | Fully connected layer |

| Dropout | p = 0.3 (after LSTM) |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Initial learning rate | 0.0005 |

| Weight decay | 0.01 |

| β1/β2 | 0.9/0.98 |

| Scheduler | Cosine annealing |

| T_max | 100 epochs |

| Minimum learning rate | η_min = 5 × 10−6 |

| Loss function | Cross-entropy with label smoothing |

| Label smoothing | α = 0.1 |

| Early stopping | Patience = 20 epochs |

| Training data | The Amazigh lexicon (33 words) |

| Data augmentation | Truncation, subsequence extraction, repetition |

| Augmentation factor | ≈×15 |

| Convergence | 67 epochs |

| Final validation loss | 0.0234 |

| Word | Transcription | Word | Transcription | Word | Transcription |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yaa | y-aa | yagh | y-ae | yar | y-ae-r |

| yab | y-ae-b | yagw | y-ae-g-w | yarr | y-ae-r |

| yach | y-ae-ch | yah | y-aa | yas | y-ae-z |

| yad | y-ae-d | yahh | y-ae-hh | yass | y-ae-s |

| yadd | y-ae-d | yaj | y-ae-jh | yat | y-ae-t |

| yag | y-ae-g | yak | y-ae-k | yatt | y-ae-t |

| yakh | y-ae-k | yal | y-ae-l | yaw | y-ao |

| yakw | y-ae-k-w | yam | y-ae-m | yay | y-ey |

| yan | y-ae-n | yaq | y-ae-k | yaz | y-ae-z |

| yazz | y-ae-z | yef | y-eh-f | yey | y-iy |

| yi | y-iy | you | y-uw | ya | y-aa |

| Decoding Method | Greedy | Beam Search | Beam + 4-Gram LM | Beam + RNN-LM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER | 0.0279 | 0.0273 | 0.0268 | 0.0277 |

| Relative Improvement | Baseline | 2.30% | 4.00% | 0.9% |

| Mot | Greedy | Beam | N-Gram | RNN-LM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ya | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 |

| yaa | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0417 | 0.0417 |

| yab | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0417 |

| yach | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0 | 0.0069 |

| yad | 0.0486 | 0.0486 | 0.0486 | 0.0417 |

| yadd | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 |

| yag | 0.0417 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0417 |

| yagh | 0.0104 | 0.0104 | 0.0104 | 0.0104 |

| yagw | 0.0365 | 0.0365 | 0.0312 | 0.0469 |

| yah | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0521 |

| yahh | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 |

| yaj | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0417 |

| yak | 0.0486 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0208 |

| yakh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| yakw | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0365 |

| yal | 0.0417 | 0.0417 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 |

| yam | 0.0486 | 0.0486 | 0.0486 | 0.0486 |

| yan | 0.0972 | 0.0972 | 0.0972 | 0.0972 |

| yaq | 0.0278 | 0.0278 | 0.0278 | 0.0278 |

| yar | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 |

| yarr | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 |

| yas | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0208 |

| yass | 0.0278 | 0.0278 | 0.0278 | 0.0417 |

| yat | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 |

| yatt | 0.0278 | 0.0278 | 0.0278 | 0.0278 |

| yaw | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 |

| yay | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0521 |

| yaz | 0.0139 | 0.0139 | 0.0139 | 0.0139 |

| yazz | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0139 |

| yef | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| yey | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0104 |

| yi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| you | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Error Type | N-gram (Improvement %) | RNN-LM (Improvement %) |

|---|---|---|

| Insertion | yach (100%), yahh (16.7%), yal (16.7%) | yahh (16.7%), yal (16.7%) |

| Substitution | yagw (14.3%), yag (16.7%) | yak (57.1%), yas (40.0%), yey (50.0%), yazz (33.3%) |

| Deletion | ----- | yad (14.3%) |

| Structure | Words | PER Greedy | PER Beam | PER N-Gram | PER RNN-LM | Error Reduction Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVV | 2 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | ~0% (no gain) |

| CVC | 22 | 0.0303 | 0.0297 | 0.0292 | 0.0303 | 3.6% |

| CVCC | 9 | 0.0247 | 0.0244 | 0.0228 | 0.0236 | 7.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Telmem, M.; Laaidi, N.; Ghanou, Y.; Satori, H. N-Gram and RNN-LM Language Model Integration for End-to-End Amazigh Speech Recognition. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040164

Telmem M, Laaidi N, Ghanou Y, Satori H. N-Gram and RNN-LM Language Model Integration for End-to-End Amazigh Speech Recognition. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. 2025; 7(4):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040164

Chicago/Turabian StyleTelmem, Meryam, Naouar Laaidi, Youssef Ghanou, and Hassan Satori. 2025. "N-Gram and RNN-LM Language Model Integration for End-to-End Amazigh Speech Recognition" Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 7, no. 4: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040164

APA StyleTelmem, M., Laaidi, N., Ghanou, Y., & Satori, H. (2025). N-Gram and RNN-LM Language Model Integration for End-to-End Amazigh Speech Recognition. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 7(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040164