1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder that contributes to cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, and preventable accidents, yet most cases remain undiagnosed [

1,

2]. Polysomnography (PSG) is the clinical gold standard for diagnosing OSA because it records multiple physiological signals simultaneously, including electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), nasal airflow, thoracoabdominal respiratory effort, oxygen saturation, and body position. Although highly accurate, PSG is expensive and resource-intensive, requires expert supervision, and needs an overnight stay in a dedicated sleep laboratory with multiple attached sensors, which many patients find uncomfortable. Its limited accessibility, long waiting times, and high operational cost contribute to the low diagnosis rate of obstructive sleep apnea worldwide [

3,

4]. These barriers have motivated interest in cost-effective and accessible screening methods. As apneic events produce different sound signals in breathing, acoustic monitoring has recently been explored as a non-invasive alternative [

5]. Detection is one part of the challenge, as an interpretation of the results and guidance for next steps are equally important. Recent work in digital health shows that visual feedback, progress tracking, and conversational support can improve engagement and adherence in chronic conditions [

6]. In the context of sleep disorders, such features can complement monitoring by turning nightly measurements into actionable insights on sleep hygiene, progress follow up, and lifestyle adjustment. These observations suggest that OSA systems should not be limited to classification, but also provide analysis, visualisation, and patient-centric coaching to support ongoing self-management.

Early smartphone prototypes explored consumer hardware for OSA detection, such as SleepMonitor, which used earbuds to capture breathing, and ApneaApp to track chest motion [

7,

8]. Both demonstrated feasibility but had practical drawbacks: earbuds disturbed sleep, sonar missed airway acoustics, and neither achieved fully on-device real-time classification. Concurrently, in related healthcare fields, work stress detection from audio streams [

9], wearables with AI for the detection of anxiety and depression [

10,

11], and the complexities of chronic diseases such as Diabetes [

12] have been reported. In addition to these early prototypes, other groups have tested different ways to reduce reliance on PSG. Romero et al. [

13] applied deep neural networks to breathing and snoring sounds recorded at home and showed that the acoustic features can support OSA screening. Montazeri Ghahjaverestan et al. [

14] extended this by combining tracheal motion, tracheal sounds, and oximetry, which improved accuracy but also required more sensors and a higher computational load. Bedside devices have also been trialled, such as the breath-indicating monitor evaluated by Rowe et al. [

15] for use in postoperative care. Contactless methods, including radar, have been reviewed by Tran et al. [

16]; these can detect breathing without attaching sensors to the patient but show mixed accuracy and still depend on specialised hardware. Reviews of OSA diagnosis and management [

17] continue to stress the need for low-cost and portable tools that can be used in convenient and cost-effective settings outside of sleep laboratories. Audio signal classification (ASC) methods continue to use compact acoustic features to train conventional classifiers, with Mel frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) being the most widely used [

18]. MFCCs approximate human auditory perception and retain key information while reducing redundancy [

19]. Direct use of raw waveforms is rarely practical, since important structures such as phonetic or respiratory patterns are not easily visible to learning algorithms. Instead, signals are divided into short frames and converted into compact descriptors. MFCCs have become the standard representation in many domains, including speech recognition, respiratory analysis, and environmental sound classification [

20]. Under PSG-based OSA screening settings, individuals benefit from contextual explanations and behavioural guidance rather than raw detection outputs alone. Achieving this level of interpretability and user-centred support calls for models capable of summarising complex patterns, answering user queries, and providing personalised recommendations that Generative AI models are uniquely positioned to offer.

Generative AI has emerged as an enabling general purpose technology for such complex needs [

21]. Unlike discriminative models that only classify or predict outcomes, Generative AI systems can summarise information, reason over contextual cues, and generate natural language responses that facilitate patient understanding and engagement. Among Generative AI approaches, diffusion-based architectures have demonstrated significant clinical utility across medical imaging tasks. These models can synthesise realistic chest X-rays and CT slices to augment limited datasets, improving disease classification performance beyond conventional convolutional neural network (CNN) baselines [

22]. They can also generate counterfactual healthy images for each patient scan; subtracting these synthetic normals from the original data automatically highlights pathological regions, reducing dependence on labour-intensive manual annotation [

23]. Beyond medical imaging, large language model-based Generative AI systems have demonstrated complementary strengths in multimodal health monitoring and patient interaction. Recent work shows their ability to interpret user intent, support conversational interfaces, and interact with structured data such as SQL tables or code fragments [

24,

25,

26]. In the context of OSA screening, these capabilities enable Generative AI to translate structured acoustic measurements into meaningful summaries, provide contextual explanations of apnea patterns, and deliver patient-centred sleep coaching. Additionally, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) allows these models to ground their responses in established clinical knowledge bases [

27], while integrated reasoning modules enable the analysis of smartphone-recorded sleep sounds—an approach supported by recent acoustic monitoring studies [

6,

7]. Together, these advances in Generative AI for disease detection, clinical data augmentation, and conversational health support make such models particularly well suited for digital health applications where personalised interpretation and dialogue-based guidance substantially improve user understanding and adherence.

Drawing on the effectiveness of MFCCs and recent developments in Generative AI, this paper proposes a novel smartphone-based framework of four Generative AI agents for bedside sleep apnea detection and sleep coaching [

28]. The four agents are the following: (1) Classifier Agent: It detects apneic events from MFCC features using Random Forest classification. (2) Analyser Agent: It manages nightly records and computes the Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI). (3) Visualiser Agent: It produces summaries and trend plots. (4) Sleep Coach Agent: It provides recommendations based on sleep data and a related evidence base. The entire framework was demonstrated and empirically evaluated on a standard smartphone using a quantised Llama 3.2-1B-Instruct-Q4 model. This bedside setup ensures that OSA detection and management can occur without the requirement for external sensors or specialised laboratory equipment [

29,

30]. By combining detection, analysis, presentation, and advice in one local framework, the system supports low-cost private screening in everyday settings. The rest of this paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology of the proposed framework,

Section 3 reports the experiments and results,

Section 4 outlines the ethics of data collection, analysis, and Generative AI agents,

Section 5 presents a discussion of the experimental validations, limitations, and future work, and finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of the main outcomes.

2. Methodology

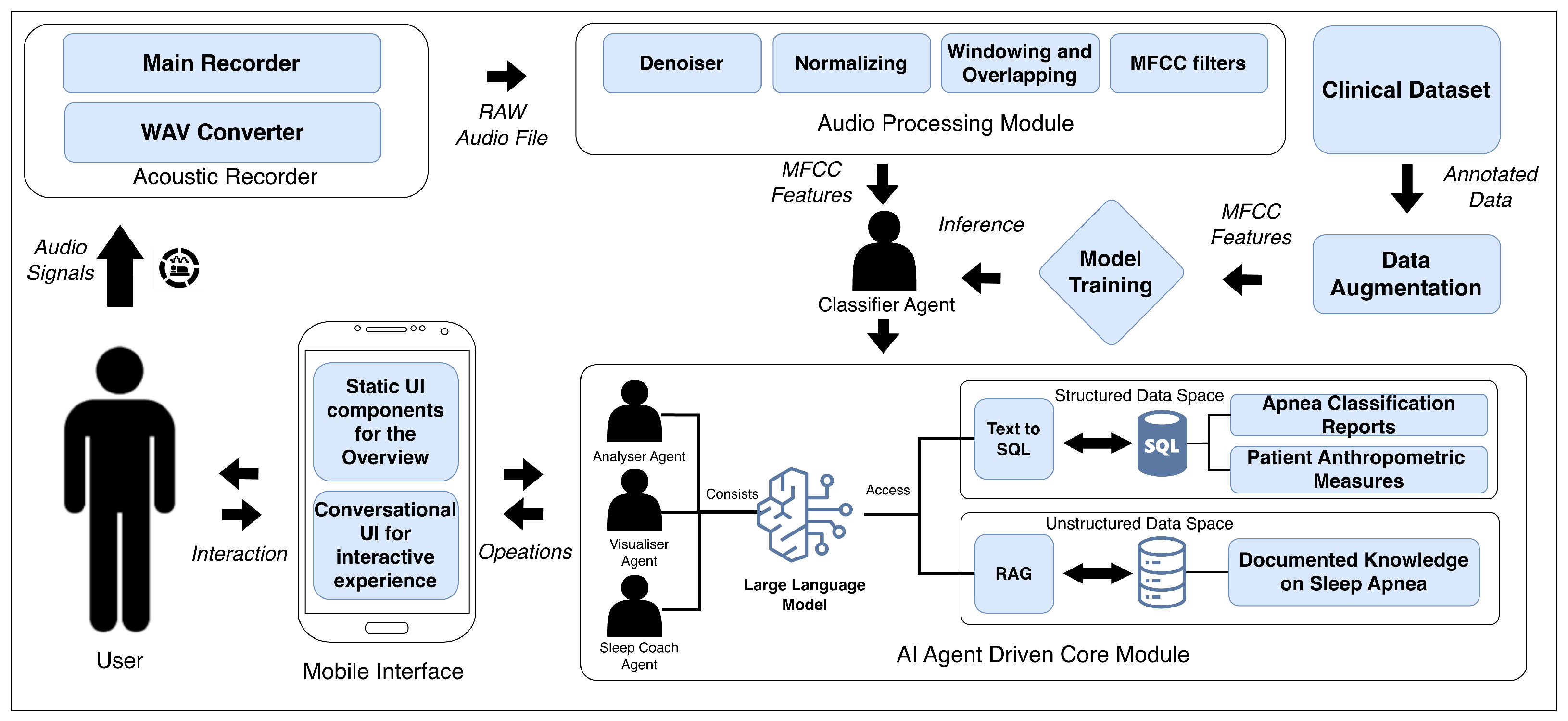

The proposed framework consists of four coordinated agents that are aligned with specific functional modules. The Classifier Agent operates on audio input recorded through the smartphone’s microphone, without requiring any external sensors or auxiliary recording devices. The Acoustic Recorder and Audio Processing modules are used to extract MFCC features and detect apneic events. The Analyser Agent integrates the outputs from the classifier with the AI Core module to compile nightly records and calculate the AHI. The Visualiser Agent links with the Mobile Interface to generate plots, summaries, and long-term trend visualisations. Finally, the Sleep Coach Agent uses the AI Core together with the retrieval of embedded sleep medicine knowledge to provide personalised feedback and recommendations.

Figure 1 shows the overall architecture of the framework, including the Acoustic Recorder, Audio Processing Module, Classifier Agent, AI Agent-Driven Core Module, Mobile Interface, and optimisation components. The following subsections describe the composition and functionality of each part in detail.

2.1. Acoustic Recorder Module

During overnight monitoring, the Acoustic Recorder captures audio through two submodules. Main Recorder: A background thread opens the native microphone API in mono PCM16, 16 kHz mode, streams 100 ms buffers into an in-memory queue, and tags each buffer with millisecond timestamps for later alignment with sleep stage annotations. WAV Converter: A producer–consumer worker pulls the queued buffers, assembles them into a RIFF-compliant stream, saves to /AudioLogs/<session>.wav, finalises the header on stop, and audits free space and I/O errors to prevent data loss.

2.2. Audio Processing Module

This module applies four signal processing stages to the WAV files generated by the Acoustic Recorder Module: de-noising, normalising, windowed framing with overlap, and MFCC extraction. Because they condense the spectral envelope into a compact, perceptual vector, the underlying Mel scale is quasi-linear below 1 kHz and logarithmic above, mirroring the decreasing frequency selectivity at higher pitches [

19].

A normal adult respiratory cycle (inspiration, expiration, and pause) lasts about 2 s to 3 s when sleeping, and for an apnea event, about 10 s [

31,

32]. After the raw waveform is saved as a WAV file, it is de-noised and peak-normalised. The cleaned signal is segmented into 10 s analysis windows with a 1 s hop so that any recovery breath straddling a boundary is captured at least once [

33]. Each frame undergoes an FFT, passes through a 26-band Mel filter bank, and is decorrelated via a discrete cosine transform; the lowest 12 MFCCs are retained. This reduces each sample frame to a compact feature vector that can be classified on the smartphone in real time.

2.3. Classifier Agent

The extracted MFCC feature vectors are then fed to this agent for classification. This module is powered by a supervised machine learning classifier, a Random Forest ensemble, that runs entirely on the device. Once the classification is complete, the results are stored in a structured SQLite database for further analysis. A Random Forest ensemble was selected as the classification model due to its strong performance on tabular feature data (MFCCs), its computational efficiency for on-device inference, and its relative robustness with moderately sized training datasets compared to more data-intensive deep learning approaches [

34].

Model Training and Data Augmentation

An anonymised dataset of 500 clinician-annotated 10 s audio clips from 10 clinically diagnosed OSA patients was collected. Each clip was labelled by an experienced sleep technologist following the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) scoring guidelines. To avoid patient-level data contamination, the subject-independent split of 200 original clips from held-out patients formed the evaluation set, while the remaining 300 original clips were used for training. Data augmentation was applied to the training set only: each training clip was duplicated with the addition of low-level pink noise, preserving class balance. This yielded 600 training examples in total (300 original + 300 augmented). The 200-clip evaluation set contained only original, non-augmented clips.

MFCC feature extraction used 12 coefficients, a 26-band Mel filter bank, DCT type II, a frame length of 10 s, and a 1 s frame overlap. A two-fold cross-validated grid search selected the optimal Random Forest configuration—100 trees, maximum depth of 20, a minimum of two samples per leaf, random state of 42—which reliably captured the apneic acoustic signature (a silent or inspiratory snore gap followed by a recovery breath) [

35,

36]. The final model was exported in WEKA format and bundled with the mobile app for real-time, on-device inference [

37].

2.4. Multi-Agent AI Module

Multi-agent frameworks are a common implementation of Gen AI systems in diverse industry sectors [

38]. This module of the framework consists of specialised Generative AI agents—the analyser, visualiser, and sleep coach. It operates over a dual-layer data space: (i) a relational

SQLite database that stores structured metrics emitted by the classifier and (ii) a vector store that indexes the unstructured domain knowledge listed in

Table 1. Deterministic SQL over numeric tables is combined with semantic retrieval from the vector store, enabling the three agents to explain anomalies, plot longitudinal trends, and deliver evidence-driven, personalised recommendations. Following each sleep session, the three agents auto-trigger a predefined set of queries (

Table 2); the resulting outputs are written to the daily_summary table (

Table 3) and populate the static daily summary dashboard. To render these results as concise, on-device natural language outputs without exposing data off-device, the agents rely on a compact LLM and RAG.

2.4.1. On-Device LLM Design and Rationale

Given the task’s narrow scope and retrieval-grounded design, we deployed an INT4-quantised 1B LLM Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct-Q4—on device. Developed by Meta, this model is part of the Llama 3.2 family of auto-regressive transformers, which are instruction-tuned using supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) to align with human preferences for helpfulness and safety [

41]. This tuning process optimises the model for dialogue and agentic retrieval tasks, making it ideal for our retrieval-grounded design. In this setting, the LLM primarily grounds and templates retrieved facts rather than perform broad, open-domain reasoning. This approach preserves handset-class latency and memory without loss of utility, a common strategy for optimising sub-billion parameter models for on-device use cases [

29].

Table 2.

Functionality and query structures of Gen AI agents.

Table 2.

Functionality and query structures of Gen AI agents.

| Agent | Description |

|---|

| Analyser (Anomaly Detection) | Summarise nightly AHI with the user’s 30-day baseline and American Academy of Sleep Medicine AASM thresholds; output a JSON risk profile.

Default Query: Summarise my weekly events for the last two months? |

| Visualiser (Plotly v4.0.0 Generator) | Receives the analyser’s JSON and optional date range; generates Plotly code that renders charts (e.g., 14-night AHI bar plot with 7-day moving average), which the sandbox executes on-device.

Default Query: Visualise AHI behaviour for most recent sleep? |

| Sleep Coach (Remedies and Recommendations) | Retrieves relevant guideline chunks from the local vector store, merges them with the risk profile and baseline characteristics, and returns up to three evidence-based recommendations, each cited to its source.

Default Query: Provide me health recommendations. |

Table 3.

Structure of the daily summary table.

Table 3.

Structure of the daily summary table.

| id | Session_Date | Total_h | ahi_est | Severity | ahi_idx | Δ30d | Alert | Created_at |

|---|

| 1 | 09-06-2025 | 7.8 | 18.4 | Moderate | 62.5 | 3.2 | 1 | 09-06-2025 |

| 2 | 08-06-2025 | 8.1 | 14.7 | Moderate | 55.0 | −0.5 | 0 | 08-06-2025 |

| 3 | 07-06-2025 | 7.5 | 32.1 | Severe | 91.3 | 12.4 | 1 | 07-06-2025 |

| 4 | 06-06-2025 | 6.9 | 9.8 | Mild | 40.2 | −7.4 | 0 | 06-06-2025 |

We ran the model with ExecuTorch, exporting to

.pte and executing on Android via the XNNPACK CPU delegate; while ExecuTorch also supports vendor delegates (e.g., Qualcomm AI Engine Direct, MediaTek AI accelerators), we do not rely on neural processing units (NPUs) in our deployment [

42]. This mirrors prior mobile deployments of Llama Guard 3-1B-INT4, which achieve practical on-device throughput (e.g., ≥30 tokens/s and ≤2.5 s time-to-first-token (TTFT)) on a commodity Android phone [

29].

Following the reference Android demo, we applied LLM-specific graph optimisations (e.g., scaled dot-product attention (SDPA), key–value (KV) cache quantisation), exported with torch.export, and lowered it to the XNNPACK delegate to produce the final ExecuTorch artefact [

43]. Our prompt+RAG agent then fused retrieved passages with the LLM’s constrained reasoning to transform raw event counts into concise, actionable guidance, with all inference performed locally on the handset.

2.4.2. RAG Pipeline

The Sleep Coach Agent delivers evidence-based recommendations to the user, supported by a RAG pipeline connected to a vector database on the device. To build this database, all knowledge documents are first semantically chunked and then indexed in a local Chroma vector store, creating the searchable knowledge base for the agent. When the user submits a question, the query is embedded, and the top chunks are retrieved by cosine similarity; these passages are used to enrich the context for grounded responses. The combined context is then passed through Lang-Chain wrappers to a quantised Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct-Q4 model running entirely on the handset, enabling privacy-preserving and retrieval-augmented answers.

2.4.3. Text-to-SQL Builder

All three agents, the sleep coach, visualiser, and analyser, depend on a text-to-SQL module that is primed with few-shot examples and the complete structured schema shown in

Table 1. Given a natural language query, the prompt in

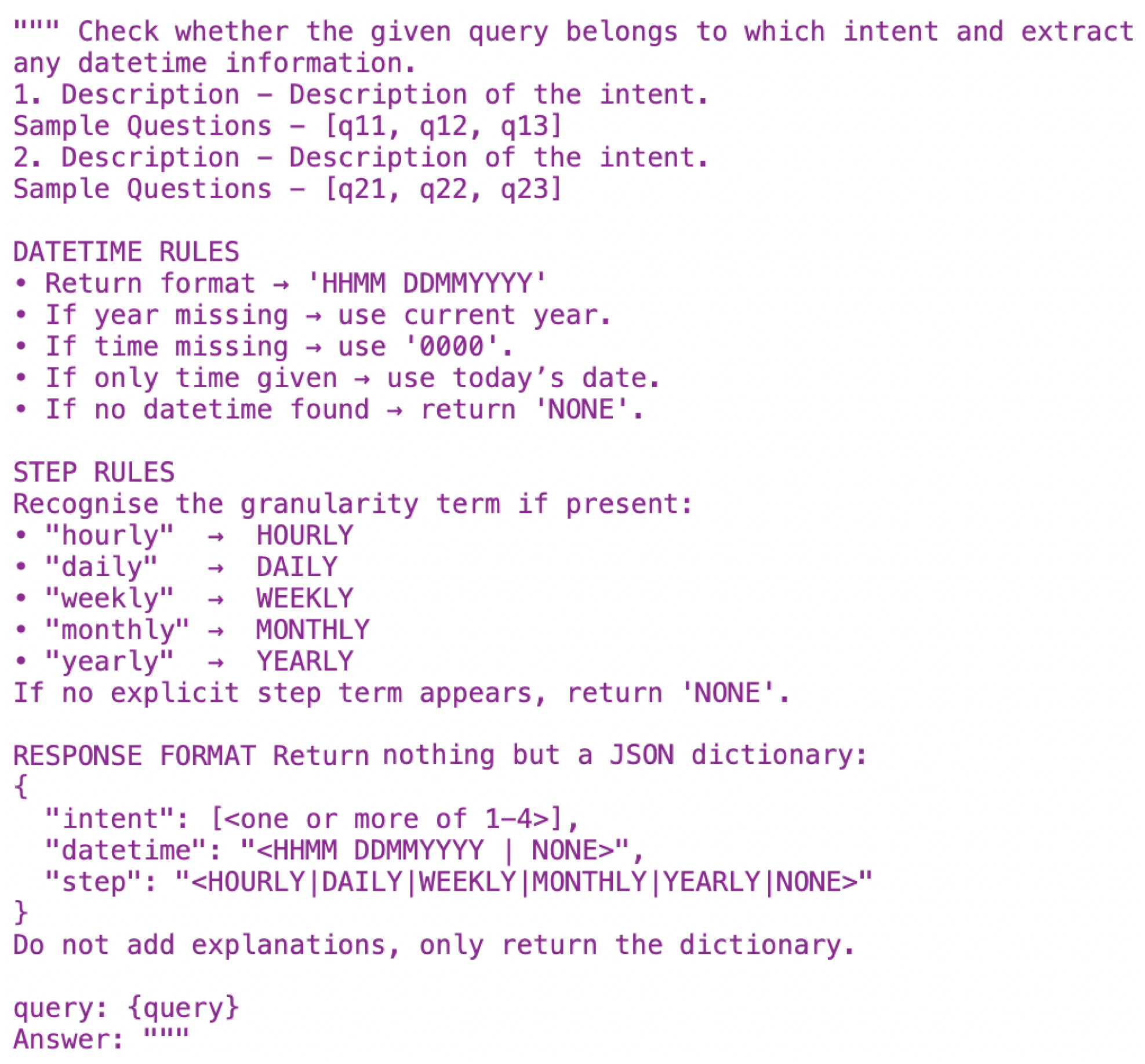

Figure 2 first extracts the time duration; for analyser queries, it also identifies the aggregation step (hourly, daily, weekly, etc.).

When the agentic core module receives queries, it undergoes initial processing. Its core function is to interpret these queries and extract key information for further processing steps. The intent extractor is vital for effectively interpreting user inputs. The following prompt in

Figure 2 is used to extract the intent. If the intent falls outside these three domains, a fallback agent answers general questions using RAG only.

If the intent is the analyser, the agent first feeds the utterance to its text-to-SQL prompt. Using the few-shot examples and schema context, the prompt in

Figure 2 extracts the required time span (start and end dates), and because this is an analyser request, it also detects the aggregation step. It then synthesises a valid SQLite query that selects and, if needed, groups data in the daily_summary table. The SQL engine then executes the query locally, and the resulting rows are returned as a dataframe. This dataframe is inserted into the LLM, summarising the data and determining the severity level, which is then passed to the on-device LLM. The LLM computes the median, maps it to the standard AHI severity bands, and produces a plain-language summary. The agent returns this summary to the chatbot, displaying the same explanation in the conversational view.

If the intent is the visualiser, the agent feeds the utterance to its text-to-SQL prompt. Only the time span is extracted (no aggregation step is needed for visualiser queries). The text-to-SQL module then produces an SQLite query that selects the relevant timestamp and AHI rows and passes it to the SQL engine. The engine executes this query locally and returns the result set as a dataframe. The LLM then generates Plotly code that renders the requested chart using that dataframe. The generated Python snippet is executed in the on-device code engine, producing the final plot image. The Visualiser Agent hands this plot back to the chatbot stream, giving the user an immediate visual depiction of the requested AHI trend.

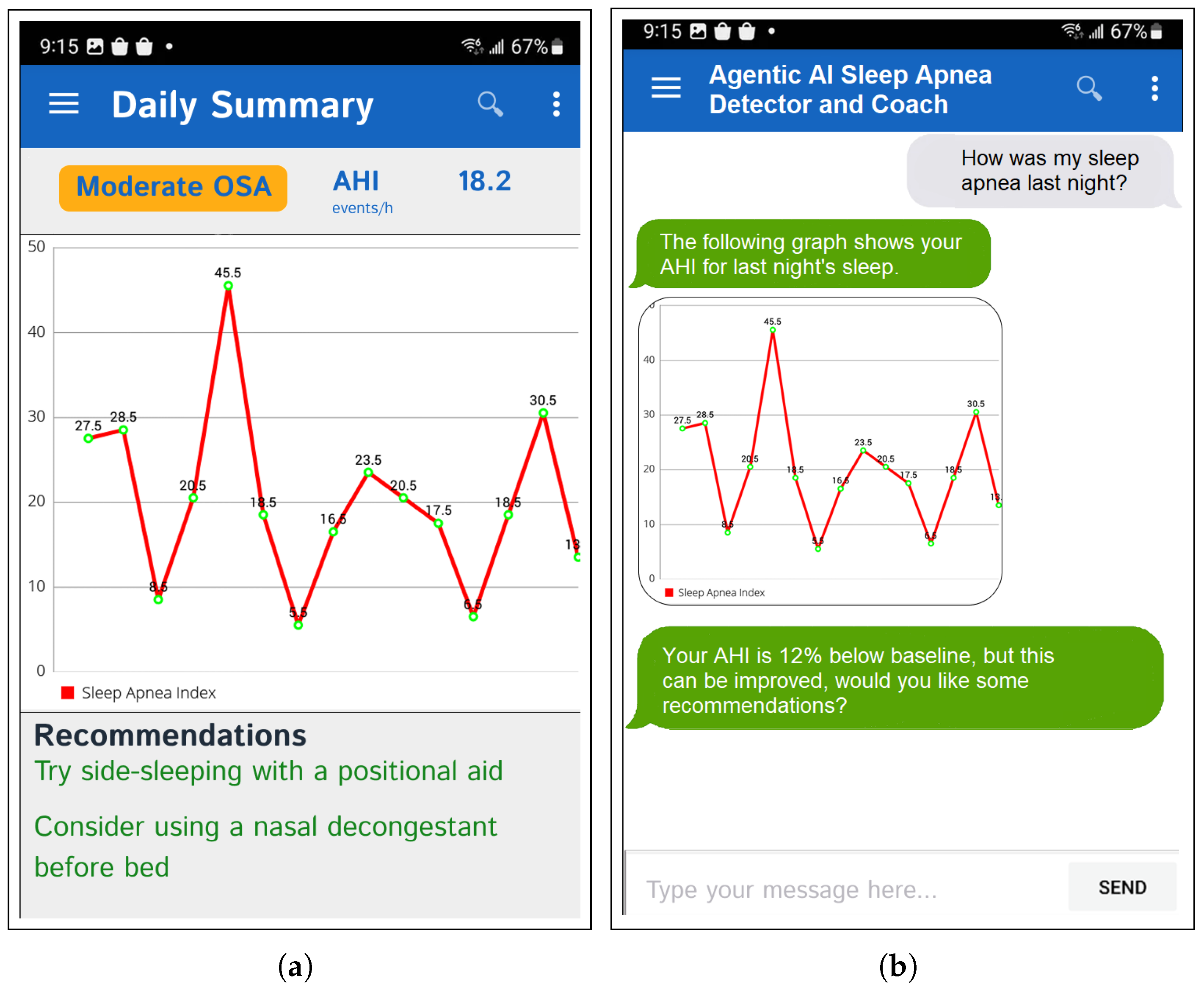

Figure 3 further showcases the end-to-end workflow of the Visualiser Agent in the chatbot system.

When a user requests guidance, the Sleep Coach Agent orchestrates a multi-agent cascade designed with explicit technical guardrails to generate safe, grounded recommendations and mitigate the risk of model hallucination. The process begins by delegating an analytics query to the Analyser Agent, which returns a concise dataframe of the user’s recent AHI trend and baseline characteristics. The primary guardrail is a multi-modal grounding process. The Sleep Coach Agent’s RAG component retrieves up to five relevant passages from the local, evidence-based vector store. These retrieved passages, along with the structured data summary from the analyser, are inserted into a single prompt for the on-device, quantised Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct-Q4 model. This ensures the resulting text is contextualised to both the patient’s own event history and established standards of care. As a final guardrail, the model’s output—an actionable recommendation list—is validated against a Pydantic schema to ensure structural integrity and block malformed responses before being delivered to the user. This entire inference loop is completed on the handset.

To guarantee deterministic rendering and block malformed code from entering the execution sandbox, every agent response is validated against a Pydantic contract (riskProfile, plotSpec, recommendationSet); if parsing fails, a structured repair prompt is issued once before the request aborts gracefully.

This pipeline, therefore, blends deterministic SQL over structured metrics with semantic retrieval over the domain literature, constraining generative steps through Pydantic-validated contracts to deliver privacy-preserving, clinically aligned decision support on a consumer handset.

2.5. Performance and Optimisation

The deployment of a multi-agent Generative AI system on a commodity smartphone necessitates a rigorous approach to managing the device’s constrained resources.

The primary challenge is the significant memory footprint of the quantised Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct-Q4 model and the Chroma vector store. To operate within the RAM limitations of a standard handset, the system employs a dynamic loading strategy. The core AI models and the vector index are not held in-memory continuously. Instead, they are loaded into RAM only upon the initiation of a user query and are programmatically released once the generative process is complete, ensuring a minimal standing memory footprint during idle periods. Power consumption is a critical factor for the viability of mobile applications. We conducted empirical tests to quantify battery drain under typical usage conditions.

2.6. Mobile Interface

The static UIs are updated on a daily basis, providing users with a consistent overview of their key metrics and insights. In addition to the static UIs and periodic agent triggers, the framework includes a conversational interface for questions in natural language and customised representations of the data. The static dashboard panel of the agent-generated daily summary is illustrated in

Figure 4a, while

Figure 4b shows further personalised information being requested and explained interactively through the chat window. This app can also trigger local push notifications to notify the user based on the overnight summary.

3. Experiments

This section presents the details and results of the empirical evaluation of the proposed framework. All on-device experiments were performed on a Samsung Galaxy S24-Plus device running Android 15, configured with a Qualcomm Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 chipset and 12 GB of RAM. First, the Classifier Agent was tested using the 200-clip hold-out set, which contained data entirely unseen by the model during training. This set, which was partitioned from the full 500-clip dataset described in the Methodology, consisted of subject-independent clips from 10 clinically diagnosed OSA patients, and was used to report the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 (

Section 3.1). Second, we examined operational robustness by varying the phone–sleeper distance (100–700 cm) (

Section 3.2). Third, we assessed robustness in diverse acoustic environments by re-running the same 200-clip hold-out set under three background-noise conditions, mixed at a fixed 15 dB SNR without retraining (

Section 3.3). Fourth, the Analyser Agent was validated by comparing nightly AHI against clinician-annotated reference tallies over 10 nights (5 participants), including Bland–Altman analysis (

Section 3.4). Finally, we profiled on-device resource use—memory, power, and surface temperature—during a 30 min interactive session (

Section 3.5). Unless stated otherwise, models operated on 10 s windows, and the results are reported as the median (p50), mean ± SD, and p95.

3.1. Performance in Classifier Agent’s Accuracy

To evaluate the preliminary performance of the Classifier Agent, we conducted a pilot experiment using audio data from ten clinically diagnosed OSA patients. The model was assessed using standard metrics of Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score [

44,

45]. Out of a total of 200 hold-out audio clips, the Classifier Agent correctly identified 179, yielding an overall Accuracy of 0.89 (95% CI: 84.1–93.0).

The system detected 88 of the 100 true apneic clips (Recall = 0.88; 95% CI: 80–93) and produced 9 false positives among the 97 clips classified as apneic (Precision = 0.91; 95% CI: 84–95). The resulting F1-Score of 0.89 for the apnea class demonstrates a strong balance between sensitivity and specificity.

3.2. Performance of the Framework at Various Distances

A test was carried out using several different distances between the smartphone and the user. The smartphone was kept 100 cm, 300 cm, 500 cm, and 700 cm away, and the performance was measured. It was noticed that the accuracy gradually decreased after 500 cm. This means that the acoustic waves captured were not detailed enough to obtain a classification beyond this distance.

When the distance is increased, the reception of the most accurate acoustics is interrupted by the quality of the recording and the details.

Table 4 shows the results.

3.3. Performance in Diverse Acoustic Environments

To evaluate the system’s robustness in non-ideal acoustic environments, the classification experiment was repeated using the same 200-clip hold-out set under three simulated background noise conditions in addition to the quiet baseline. Background noise recordings were sourced from publicly available acoustic datasets: HVAC hum and urban traffic from the DEMAND dataset [

46], and snoring audio from the PhysioNet Snore Database [

47]. Approximate sound pressure levels (dBA) for each noise type were derived from the RMS amplitude of the source recordings, calibrated against a 1 kHz reference tone of the known sound pressure level. The tested conditions were as follows: (1) Baseline: quiet room environment (<35 dBA); (2) HVAC Noise: constant, low-frequency hum from a window air conditioning unit (≈45 dBA); (3) Urban Noise: intermittent, variable traffic sounds recorded from a window facing a residential street (≈50 dBA); (4) Competing Snorer: audio recordings of a snoring bed partner, acoustically similar to some respiratory events (≈55 dBA). Noise mixing and SNR calibration were performed in Python 3.10 using the librosa and numpy libraries. For each condition, the noise track was amplitude-scaled to achieve a target signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 15 dB relative to the clean apnea clip, and then digitally mixed. After mixing, all clips were RMS-normalised to maintain consistent loudness across conditions. The trained Random Forest model was evaluated without retraints. Model performance for each condition was computed using scikit-learn’s classification_report, extracting Precision, Recall, and F1-score for the apnea class.

Table 5 summarises these results and illustrates the degradation in performance under acoustically challenging scenarios, particularly with competing snoring due to its spectral similarity to target events.

The system is relatively robust to constant background noise but is more affected by intermittent and acoustically similar interference, particularly competing snorer scenarios. This highlights the need for advanced noise suppression or multi-modal sensing to enhance real-world reliability.

3.4. Performance of System AHI Validation

From the hold-out dataset, each night’s audio recordings were segmented into hourly blocks, with each block manually annotated for apneic events by a sleep technologist following AASM criteria to establish a reference AHI. The demographic characteristics of the 10 participants included in this study are shown in

Table 6.

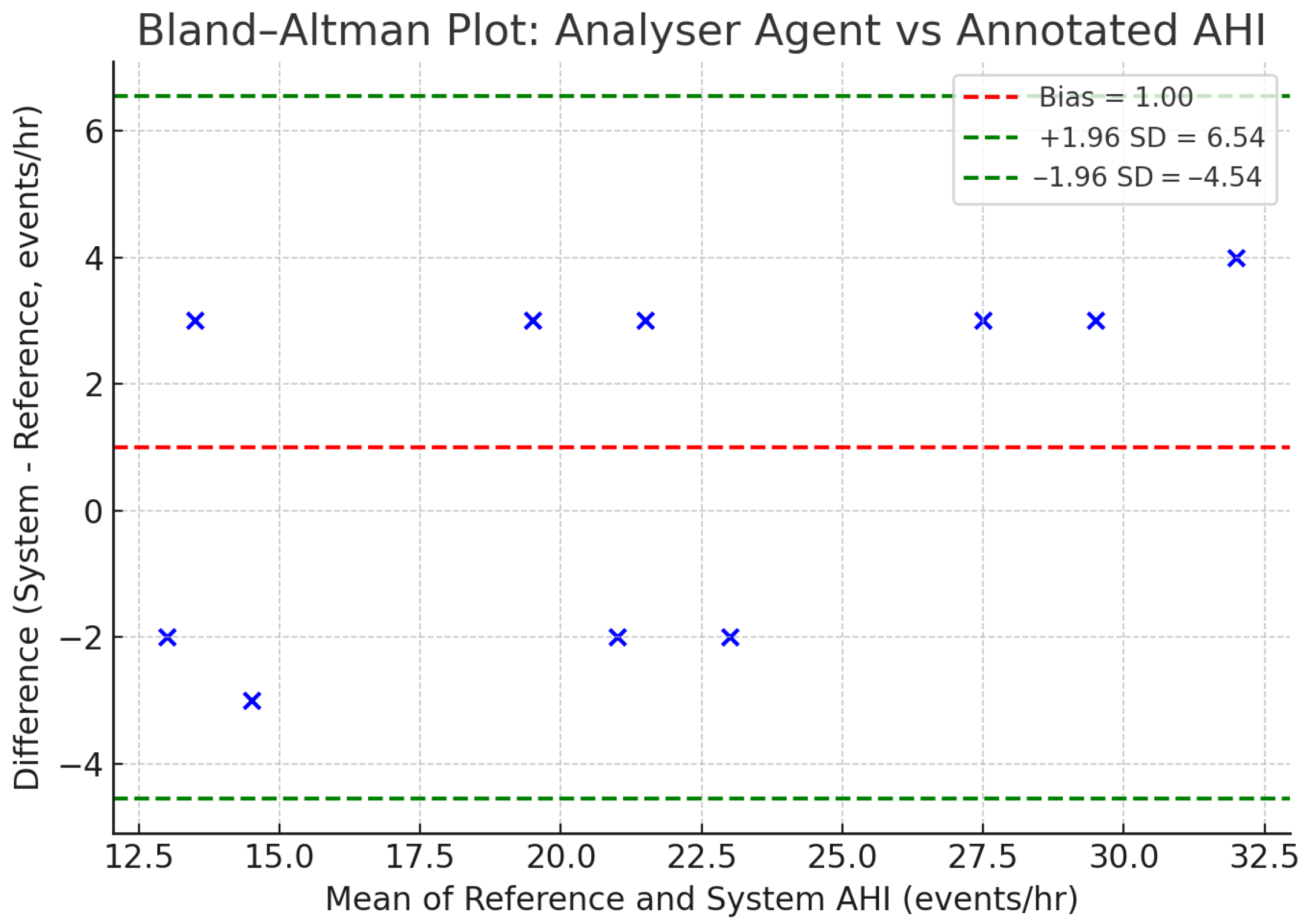

The Analyser Agent aggregated 10 s classifier outputs within each hourly block to generate system-estimated AHI values, which were then compared against the manual annotations. Across the ten nights, manually annotated reference AHI values ranged from 12 to 30 events/h, while the system-estimated AHI values ranged from 12 to 34 events/h. A detailed, night-by-night comparison of the reference and system AHI values is presented in

Table 7. The median absolute difference between the two methods was 3.0 events/h.

To visually assess the agreement between the two measurement methods, a Bland–Altman plot was constructed [

48], as shown in

Figure 5. The plot illustrates the difference between the system and reference AHI against their mean for each recording. The analysis revealed a mean difference (bias) of +1.0 events/hour, indicating a slight systematic tendency for the Analyser Agent to overestimate the AHI compared to the reference standard. The 95% limits of agreement were −4.54 to +6.54 events/hour, with all ten data points from

Table 7 falling within this range. Furthermore, per-night AHI estimates from the system correlated strongly with derived clinical AHI values (Pearson’s r = 0.80,

p < 0.01, N = 10 nights), supporting the feasibility of the approach as a first-line screening tool.

3.5. System’s On-Device Resource Consumption and Latency

To complement the clinical efficacy analysis, we designed a dedicated on-device benchmark to quantify technical performance and resource impact on consumer hardware, targeting a responsive user experience within acceptable thermal/power envelopes. All benchmarks were executed from a fully charged state (100%), with non-essential background applications closed; device temperature was allowed to return to an ambient steady-state before each run. A standardised interactive session was scripted to simulate typical engagement: 20 distinct queries over 30 min, including simple look-ups (e.g., “What was the AHI last night?”), chart generation, and complex RAG-based questions (e.g., “Explain how my sleep position affected my breathing events”). Real-time CPU, memory, energy, and temperature were captured using Android Studio profilers. Energy per step was computed as

(average power

from OS counters;

t is step latency). For pipeline latency, we measured the end-to-end timing from audio ingestion to the first coaching output on device: after a 60-window warm-up, we streamed 20 min of 10 s windows at a bedside distance of 100 cm (optimal capture range from

Section 3.2), and then invoked the visualiser and a single sleep coach prompt. For each window, stage entry/exit times were logged using a monotonic clock, and we report the medians (p50), means ± SD, and 95th percentiles (p95).

The per-agent and per-stage latency, CPU, memory, and energy are summarised in

Table 8. The core detection loop comfortably meets real-time constraints: the classifier achieves a total of 30 ms (p50; p95

ms) at ≤21% CPU,

GB RSS (mean), and ≈0.48 mWh per 10 s window, while the analyser achieves 18 ms (p50; p95

ms) at ≤14% CPU,

GB RSS, and ≈0.28 mWh. Visualiser chart generation remains interactive with a p50 of 1700 ms (p95

ms),

CPU,

GB RSS, and

mWh per chart. The sleep coach RAG turn is the dominant cost: p50

ms (p95

ms),

CPU,

GB RSS, and ≈10.90 mWh per query (with the LLM step accounting for the majority of this budget). Overall, the on-device three-agent framework is feasible on modern handsets; interactive coaching is the primary latency/energy driver.

4. Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitive nature of health data and that of patient decision making, this section addresses the key considerations of data governance, algorithmic fairness, clinical responsibility, medical ethics, and responsible Generative AI and health literacy. The framework was evaluated according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the WHO guidance on ethical issues in public health surveillance [

49,

50]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for the anonymised use of their data in research and publication.

4.1. Data Governance and Privacy Protection

All audio clips were irreversibly de-identified prior to analysis, with personal identifiers permanently removed and replaced with anonymous codes. The privacy-by-design approach ensures all user-generated data, including raw audio recordings, personal anthropometric data, MFCC features, and nightly AHI results, is processed and stored exclusively on the user’s device. Sensitive health information is not transmitted to external servers, eliminating the risk of interception during transmission. Vector databases, model weights, and user profiles remain entirely on-device. The system adheres to data minimisation principles by collecting only the audio data necessary for classification and retaining only aggregated, non-identifying metrics for longitudinal trend analysis.

4.2. Algorithmic Fairness and Bias Mitigation

The classifier was trained on only ten individuals with demographic skew (male = 8, female = 2, age = 45 ± 6 years). This limits statistical validity and population generalisability. Model performance may vary across genders, ages, ethnicities, body types, and comorbidity profiles. To address these limitations, performance metrics are reported for balanced datasets to prevent inflated accuracy from class imbalance, and, where possible, we report performance across available demographic subgroups. As planned future work, addressing bias includes expanding data collection across diverse clinical sites and populations, implementing privacy-preserving federated learning to improve model generalisability, and establishing ongoing bias-monitoring protocols for deployed systems.

4.3. Clinical Responsibility and Medical Ethics

This framework was explicitly designed as a detection and coaching tool, and not a diagnostic medical device. It is not a regulated medical device and is not intended for the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease. The system does not provide medical diagnoses and cannot replace clinical PSG. Instead, it is intended to help identify individuals who may benefit from formal evaluation in a clinical setting and to increase awareness of sleep apnea symptoms and risk factors. All recommendations are based on established clinical guidelines (AASM) and the peer-reviewed literature. The system was designed to support, not replace, clinical decision-making, and users are strongly encouraged to discuss all results with a qualified healthcare provider.

4.4. Responsible Generative AI and Health Literacy

The inherent Gen AI risk of model hallucination is acknowledged, whereby the LLM could generate factually incorrect or potentially harmful advice. To mitigate this, we implemented a multi-layered safety strategy consisting of the interconnected technical guardrails detailed in

Section 2. This strategy includes (i) a multi-modal grounding process to ensure responses are based on both the user’s data and curated clinical evidence; (ii) instructional constraints within the agent’s meta-prompt to prevent it from exceeding its designated coaching scope; and (iii) a post-generation validation layer to ensure the structural integrity of all outputs before they are presented to the user.

5. Discussion

This section consists of the experimental findings, positions the proposed framework within the broader clinical and technological landscape, and outlines the limitations and future work required for robust deployment in real-world settings. The experimental results demonstrate that MFCC-based acoustic features, combined with Random Forest classification, provide effective detection of apneic events. The achieved Accuracy of 0.89, Precision of 0.91, and Recall of 0.88 indicate that respiratory sound patterns contain sufficient structure for reliable screening when processed in short, frame-based segments. The Analyser Agent’s AHI estimation shows strong correlation with clinician annotations, suggesting that simple acoustic cues when consistently captured can reflect nightly apnea burden. The robustness experiments further highlight that the system performs well under typical bedroom conditions. On-device evaluations confirm that quantised Generative AI models can operate within the computational and battery constraints of modern smartphones, enabling entirely offline, privacy-preserving deployment.

The smartphone-based framework was explicitly designed as a pre-screening and longitudinal self-monitoring tool rather than a diagnostic replacement for PSG. The smartphone-based approach offers several practical advantages: it is non-invasive, has a low cost, and is deployable at the bedside using only the built-in microphone, thereby avoiding electrodes, wearable sensors, and specialised laboratory infrastructure. Also, given its low operational cost, it has the ability to conduct repeated measurements in natural home environments without expert intervention. These features improve accessibility and enable early identification of individuals who may benefit from formal clinical evaluation. Furthermore, the integrated Generative AI agents provide immediate nightly summaries, trend visualisation, and personalised sleep coaching features not present in conventional PSG workflows. Unlike PSG, which typically captures only one or two nights of data, the proposed framework enables continuous nightly monitoring, allowing users to observe short-term and long-term changes in apnea patterns and track progress over time. However, PSG remains the gold standard for diagnosing and staging OSA because it measures a comprehensive set of physiological channels, including EEG, EOG, EMG, airflow, respiratory effort, and oxygen saturation. As an audio-only system, the proposed framework cannot assess sleep architecture, arousal patterns, or multi-channel respiratory physiology. The framework is presented as a research prototype that can complement clinical diagnostics by enabling non-invasive and accessible early screening.

The following limitations are inherent in the proposed framework, and we intend to address them in future work, as deliberated below. Firstly, the dataset used for training and evaluation consisted of 500 annotated respiratory sound clips from 10 clinically diagnosed OSA patients. This is a small sample size, but we addressed the inherent statistical uncertainty by calculating 95% confidence intervals (CI) for our performance metrics. As reported in

Section 3.1, while the mean Accuracy was 0.89, the 95% CI ranged from 84.1% to 93.0%. Second, the system relies exclusively on the built-in microphone of the smartphone and does not incorporate posture, movement, or oximetry information factors known to influence the severity of apnea. Regarding error analysis, we assessed clinical agreement using Bland–Altman plots, as shown in

Figure 5, which confirmed that despite the sample size, the systematic bias remains low (+1.0 events/h) with limits of agreement (−4.54 to +6.54) falling within clinically relevant ranges. This indicates that errors are generally consistent rather than erratic. However, our robustness evaluation

Table 5 revealed specific failure modes: the presence of a “competing snorer” caused the F1-Score to drop to 0.68, indicating that the model struggles to differentiate the target user’s recovery breaths from a bed partner’s snoring. As the model was evaluated on patients with diagnosed OSA (high pre-test probability), the reported False Positive Rate (FPR) may not reflect performance in a healthy, low-prevalence population. Consequently, the current system was validated as a screening tool for suspected cases rather than a general population diagnostic. To mitigate over-fitting despite these limitations, we employed a strict subject-independent holdout validation strategy and utilized a Random Forest classifier to reduce the data hungriness associated with deep learning. The Visualiser and Sleep Coach Agents preclude standard quantitative accuracy benchmarking due to the lack of a deterministic ground truth.

The current sample size limitations will be addressed through a larger multi-institution data collection initiative. By expanding data collection across multiple institutions, healthy controls will be included to calibrate the model’s decision threshold for low-prevalence populations. The integration of low-cost posture or motion sensors may enable position-specific accuracy improvements and richer behavioural insights. Federated learning approaches will be explored to allow collaborative model training across clinical sites while preserving device privacy. Implementing such an initiative presents a data collection challenge in requiring HIPAA/GDPR compliance frameworks for cross-institutional sharing. Furthermore, recruiting healthy controls is operationally difficult as sleep clinics predominantly service symptomatic patients, with high manual annotation costs due to the need for expert sleep technologists to counter inter-scorer variability. Generalisability and federated learning are impacted by computational and algorithmic challenges. As indicated by our benchmarks in

Table 8, full on-device model tuning demands more energy than inference [

29,

30]. To make FL feasible, we must explore parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods to reduce the communication and computation overhead of weight updates [

51]. Continuous bias monitoring also presents a challenge in a deployed setting, as “ground truth” (PSG) is absent. Detecting model drift or demographic bias shifts in real time requires establishing costly proxy metrics to validate performance without daily clinical labels.

6. Conclusions

This paper reports the design, development, and evaluation of a low-cost, smartphone-based Generative AI agent framework for sleep apnea detection and sleep coaching at the bedside. The framework consists of four agents: a classifier, analyser, visualiser, and sleep coach. The key agentic activities performed are sleep apnea detection, sleep data management, data analysis, and natural language sleep coaching. This system is not intended to replace PSG; instead, it is positioned as a pre-screening and awareness tool that may complement, but not substitute, formal clinical evaluation. The framework was empirically evaluated on a subject-independent hold-out set drawn from a dataset of 500 clinician-annotated clips collected from 10 clinically diagnosed OSA patients. Further evaluations were conducted to assess operational robustness, robustness in diverse acoustic environments, comparison against clinician annotated references, and on-device resource usage. These evaluations were based on a small, demographically limited dataset, and hardware testing was restricted to a single high-end consumer smartphone. Future work will address these limitations as well as develop agentic capabilities for the privacy preservation of patients using federated learning, operational optimisation of on-device Gen AI models, and training on balanced datasets for generalisable classification accuracy.