A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach for the Selection of Explainable AI Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Empower individuals to combat any negative consequences of automated decision-making.

- Help individuals make more informed decisions.

- Detect and prevent security vulnerabilities.

- Integrate algorithms with human values.

- Improve industry standards for the development of AI-based products, thereby increasing consumer and business trust.

- Promote a Right of Explanation policy.

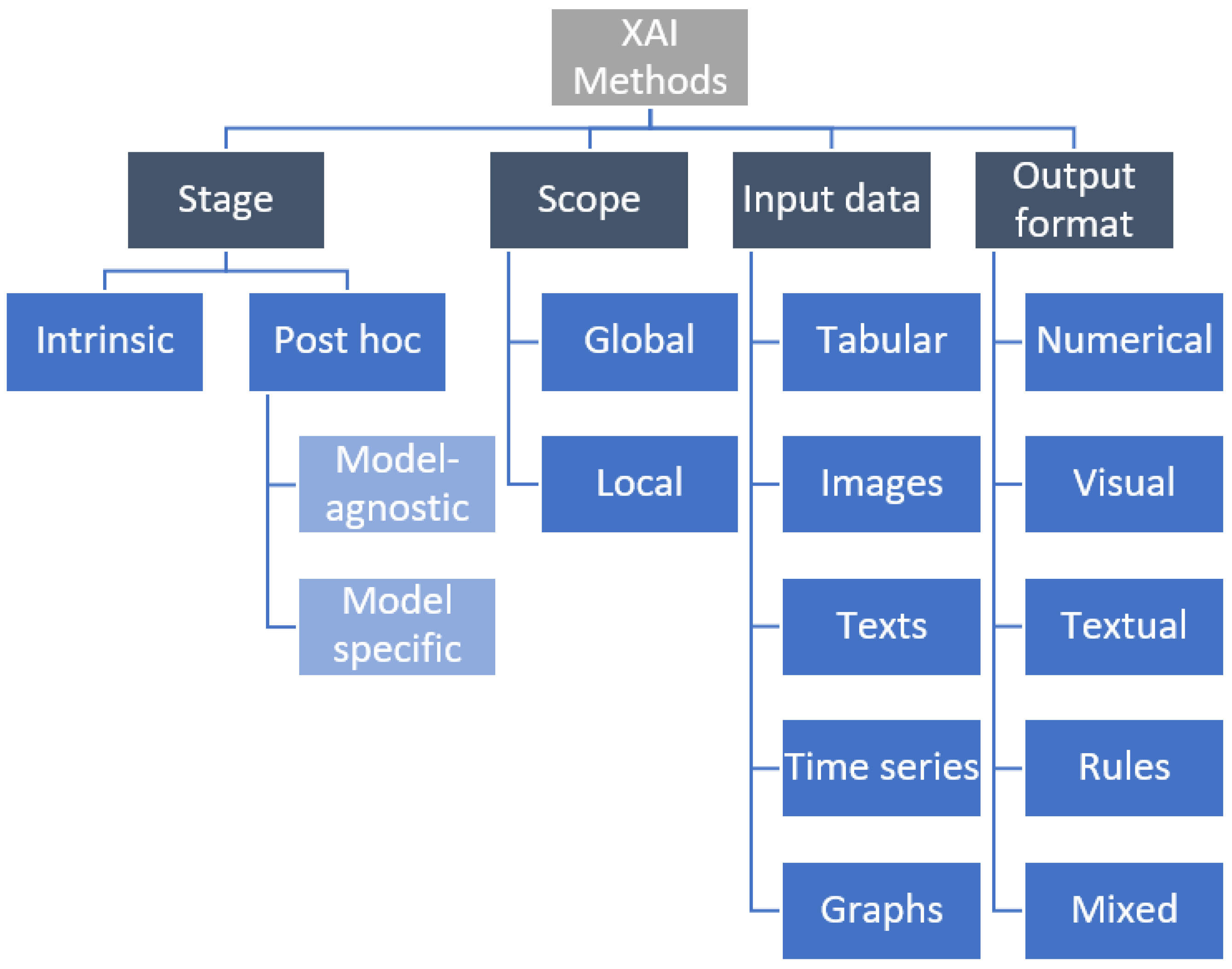

2. Basic Taxonomy of XAI Methods

2.1. Intrinsic and Post hoc Methods

2.2. Model-Specific and Model-Agnostic Methods

2.3. Local and Global Methods

2.4. Methods by Input Data

2.5. Methods by Explanation Type

3. Related Work

3.1. Selecting the XAI Method

3.2. Evaluation of XAI Methods

- Content: Correctness, Completeness, Consistency, Continuity, Contrastivity, Covariate complexity;

- Presentation: Compactness, Composition, Confidence;

- User: Context, Coherence, Controllability.

- Application-grounded evaluation: This involves implementing models and testing them on a real-world task by running experiments with end users. The best way to show that a model works is to evaluate it on the task for which it was created.

- Human-grounded evaluation: This level is also tested in practice, the difference being that these experiments are not performed with domain experts, but with laypeople. Since no domain experts are needed, the experiments are cheaper, and it is easier to find more testers.

- Functionally grounded evaluation: This level does not require human evaluation. Instead, it uses a formal definition of explainability as a model of the quality of explanation. This evaluation is most appropriate when we have models that have already been validated, e.g., through human-based experiments.

3.2.1. Objective XAI Metric

3.2.2. Subjective XAI Metric

3.2.3. Benchmarks and Libraries Focused on Evaluating XAI Methods

4. Methods

4.1. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making

4.1.1. Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

4.1.2. Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC)

4.1.3. Additive Ratio Assessment (ARAS)

4.1.4. Borda Count

4.1.5. Combinative Distance-Based Assessment (CODAS)

4.1.6. Evaluation Based on Distance from Average Solution (EDAS)

4.1.7. Multi-Attributive Border Approximation Area Comparison (MABAC)

4.1.8. Measurement of Alternatives and Ranking According to Compromise Solution (MARCOS)

4.1.9. Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment of Evaluations II (PROMETHEE II)

4.1.10. The Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solutions (TOPSIS)

4.1.11. Višekriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Rešenje (VIKOR)

4.1.12. Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment (WASPAS)

4.1.13. Weighted Sum Model (WSM)

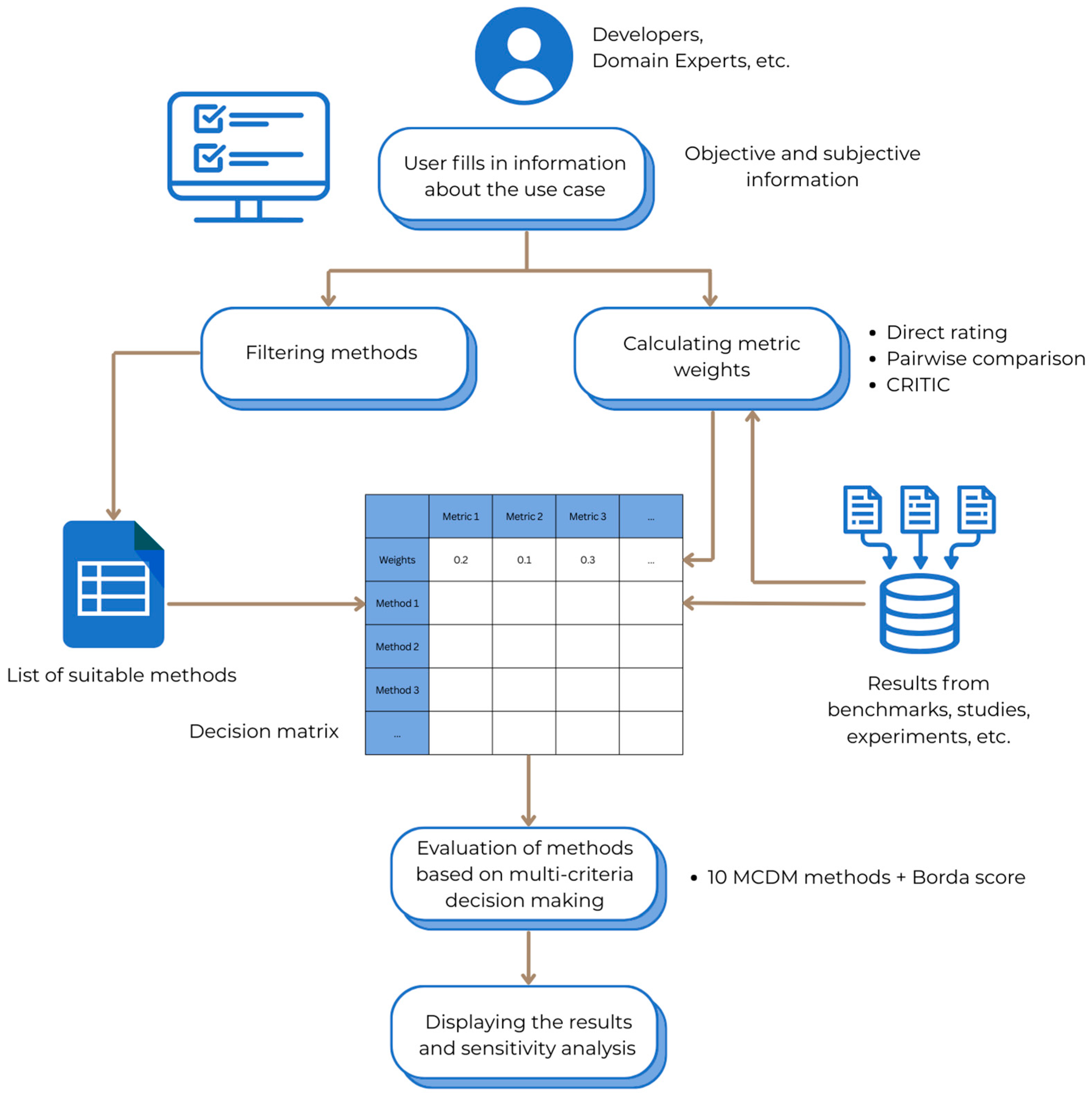

5. Proposed Tool for Selection of Explainable AI Methods

5.1. Filtering Methods

- The first column must strictly contain the names of the XAI methods (serving as the alternatives).

- The subsequent columns must specify the names of the evaluation metrics (serving as the criteria) and the corresponding performance results for each method against these metrics.

5.2. Choosing a Method Using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making

- Direct Rating—The first option is to enter the criteria weights directly for each of them as a number on a scale from 1 (unimportant) to 10 (very important). This option is suitable when the user has a clear idea of the importance of the metrics.

- Pairwise comparison—The second option is a pairwise comparison of metrics (based on AHP). This method is not suitable for a higher number of metrics, because in that case, it is necessary to make many comparisons, which can be cognitively demanding and confusing. The recommended number is a maximum of 9 [83], ideally 3 to 7.

- CRITIC—The third option is the use of the CRITIC method, which serves to objectively determine weights based on variability and relationships between criteria. This method is also suitable for a larger number of metrics.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

5.4. Use Cases

- 1.

- Define Context, Metrics, and XAI Methods

- Identify XAI candidates: Filter the set of XAI methods to be evaluated (e.g., the 3–5 methods relevant to the user’s specific ML model).

- Define evaluation metrics: Determine the key performance indicators that the XAI method must satisfy. These should include standard measures and domain-specific needs.

- Determine metric type: Classify each metric as either a Benefit (higher value is better) or a Cost (lower value is better).

- Input performance data: The user must run each candidate XAI method and input the performance data into the tool.

- 2.

- Establish Weights

- 3.

- Obtaining the Borda count based on MCDM methods results

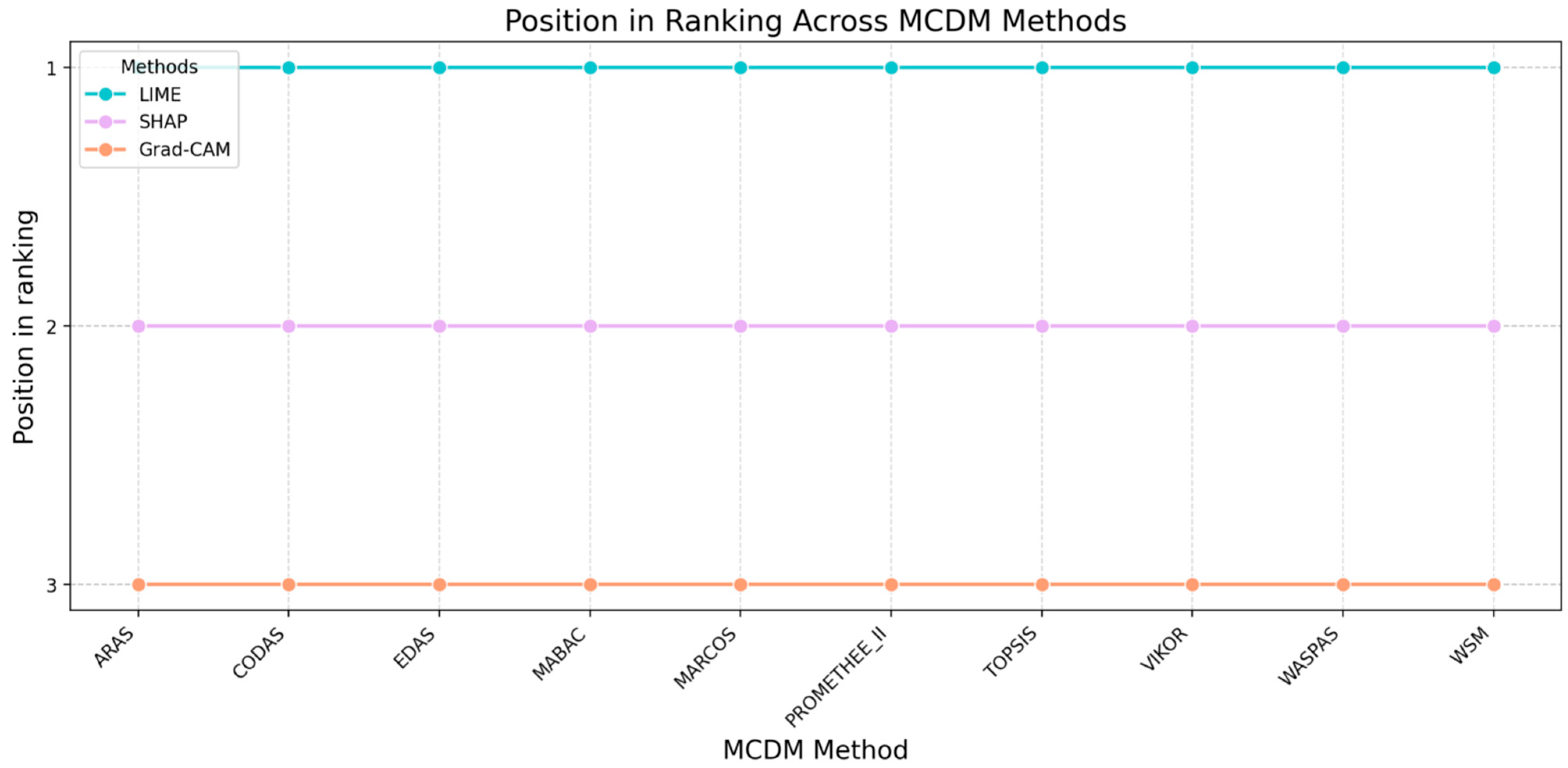

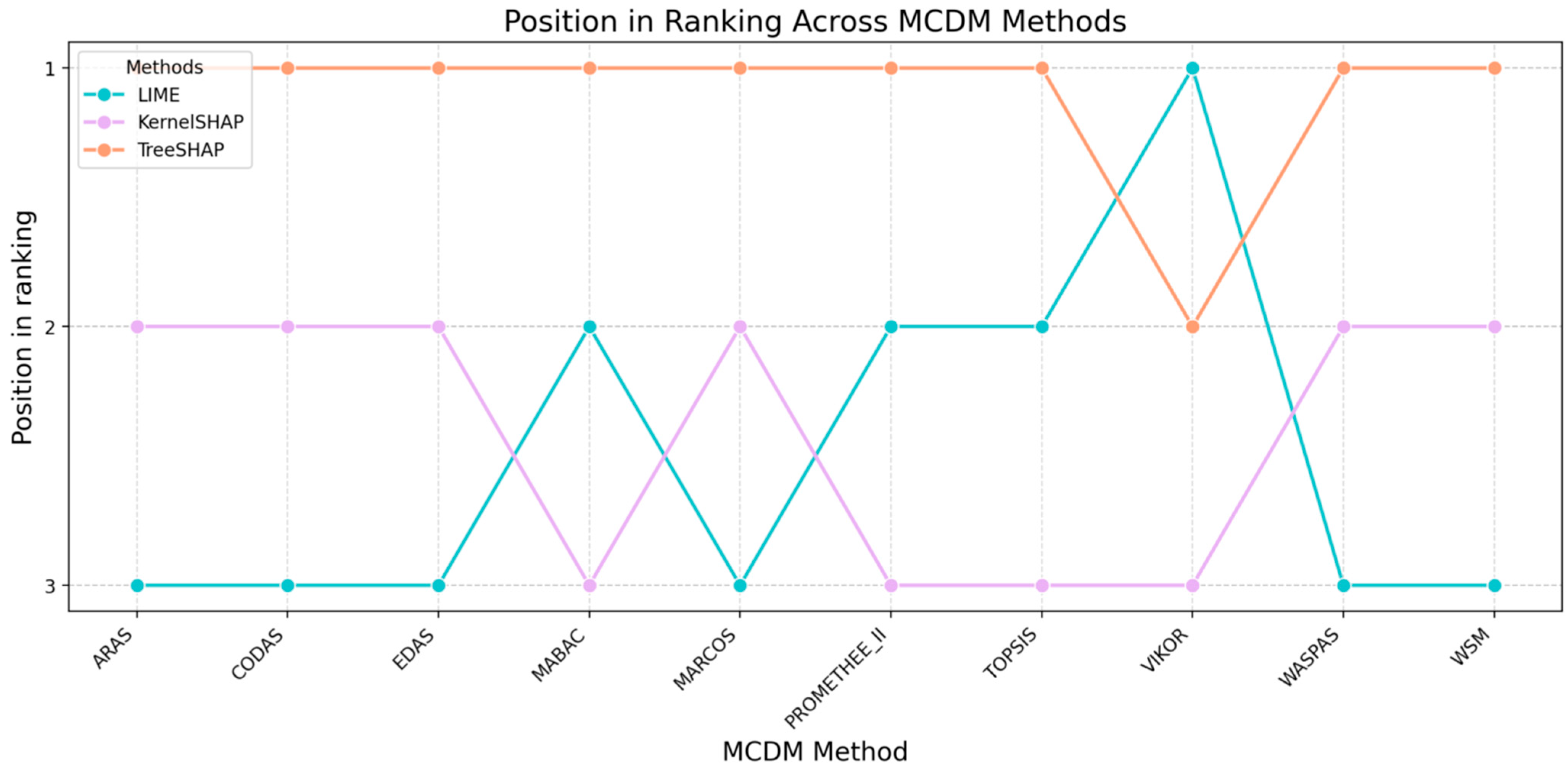

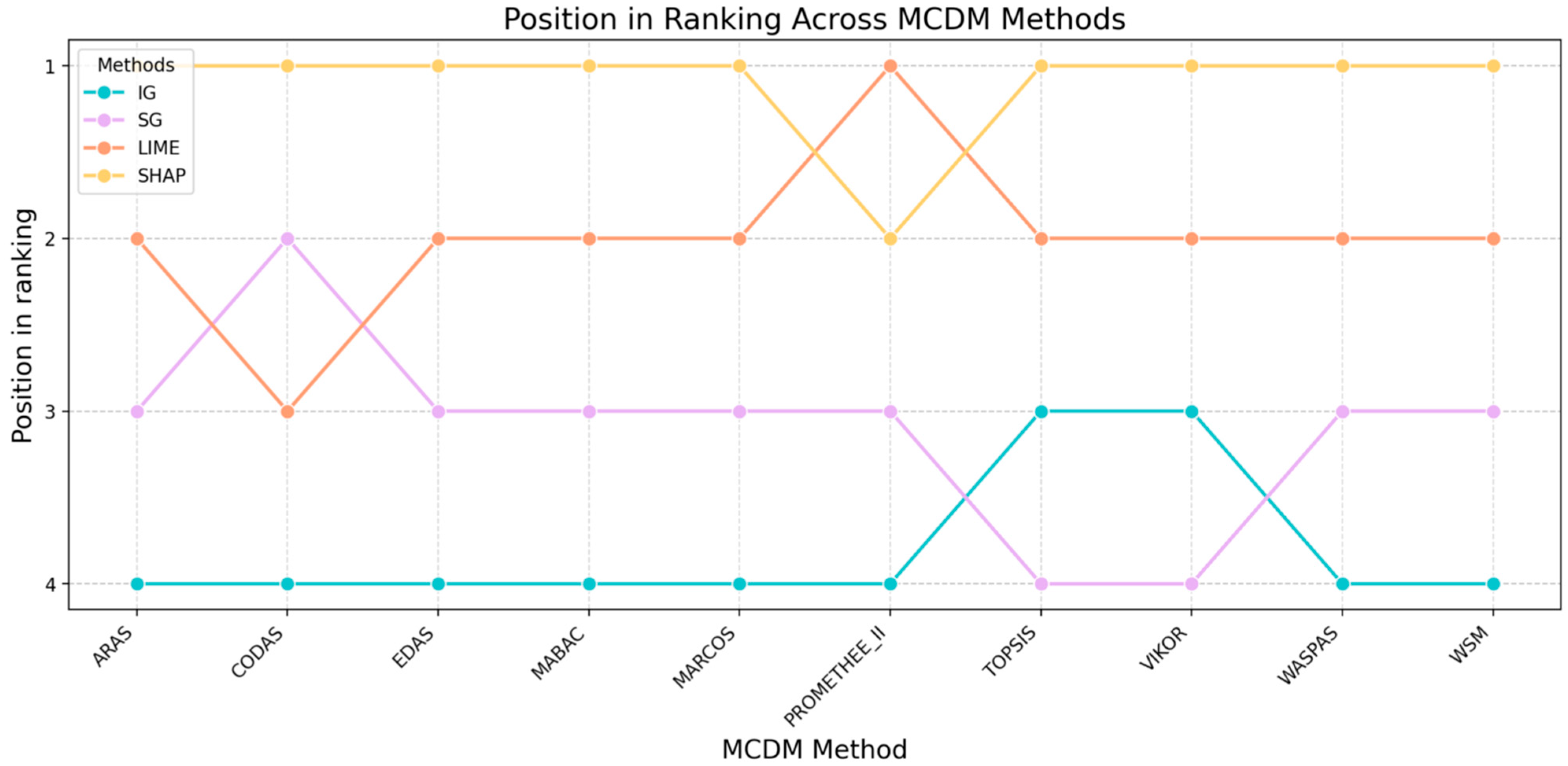

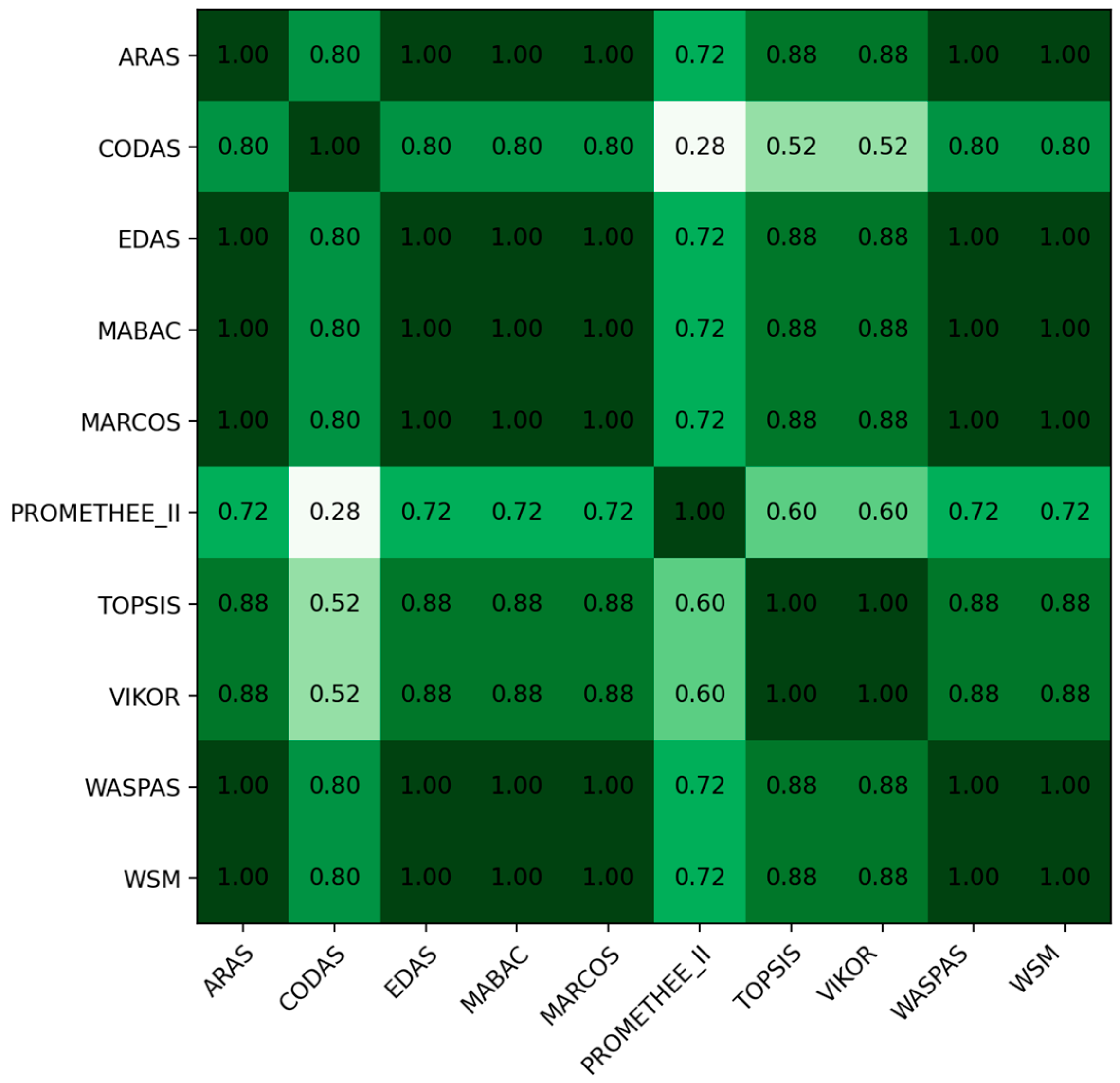

- Initial ranking: Review the initial preference scores and the resulting ranking from each method.

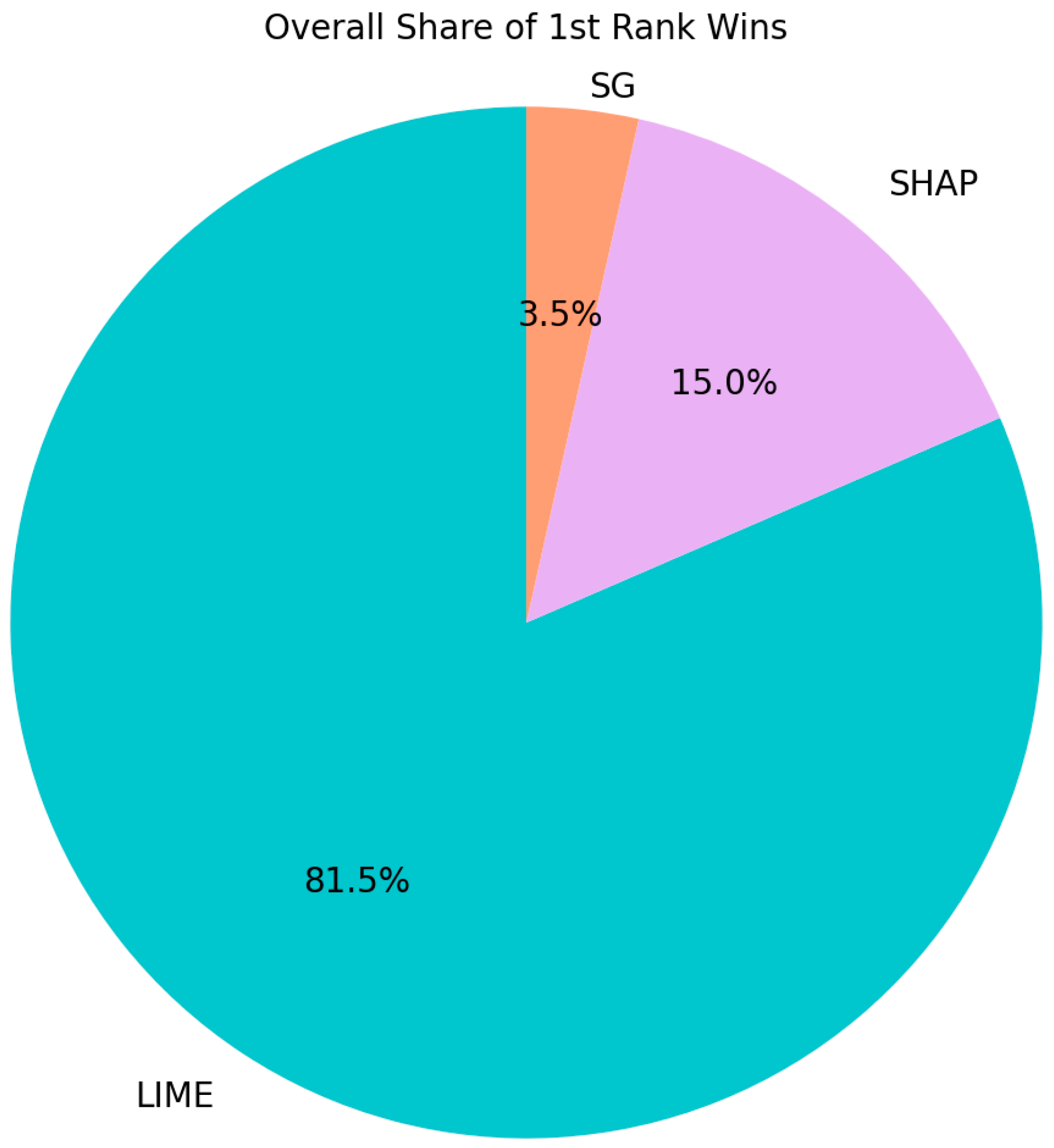

- Borda count: The Borda count provides a balanced overall rank for each XAI method.

- 4.

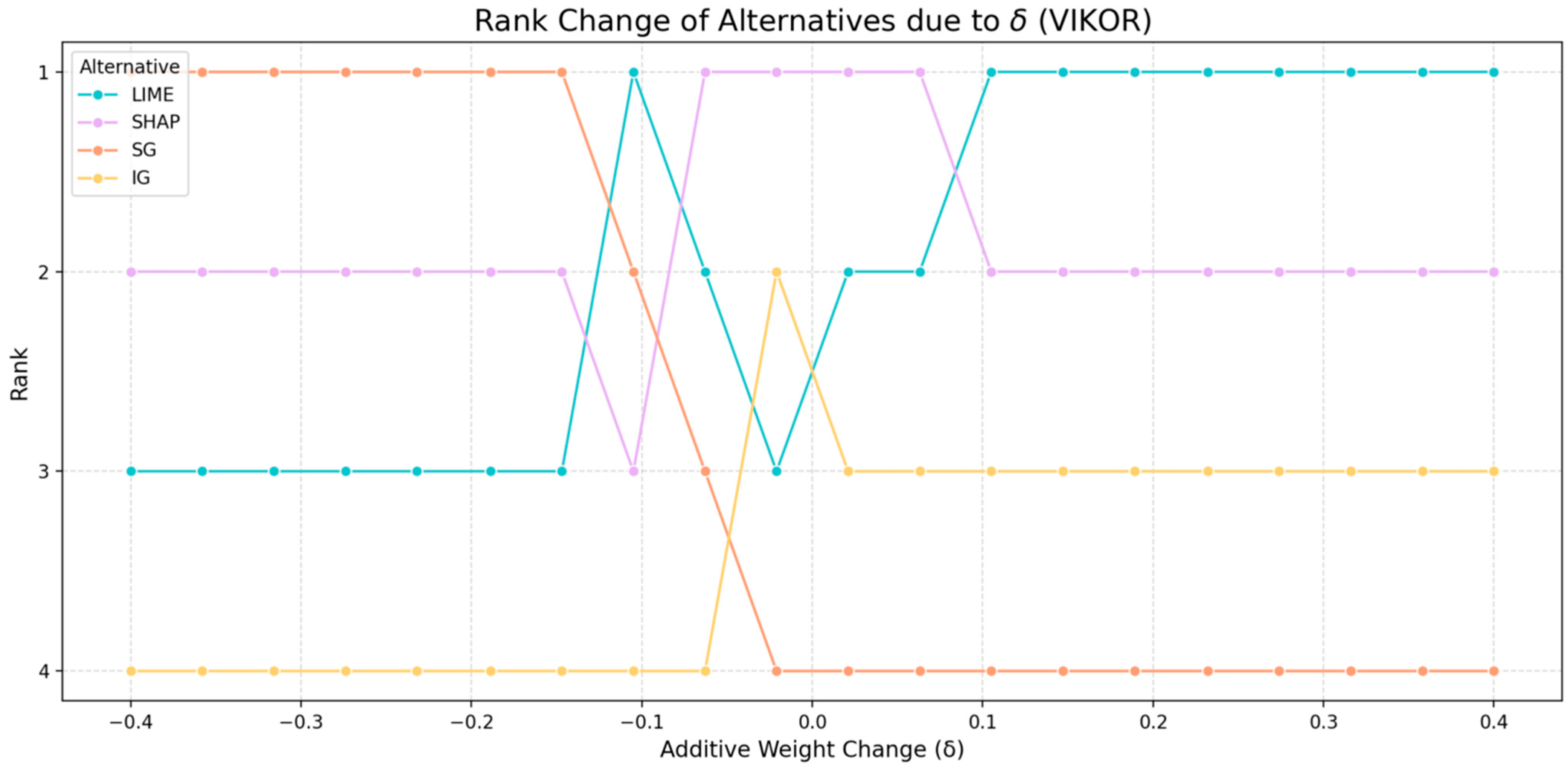

- Validate Robustness (Sensitivity Analysis)

- Sensitivity tests: Observe how the resulting order of methods changes when changing the weights by a factor of .

- Analyze rank stability: Review the table that shows how often each XAI method retained Rank 1 across all weight perturbations and MCDM methods.

- Review rank change plots: Examine the visual plots to identify the following:

- ○

- Stable Leaders: Lines that stay consistently high.

- ○

- Crossover Points: Areas where lines intersect, indicating high instability and a change in the rank when the weights shift marginally.

- 5.

- Final Selection and Documentation

- Document Decision: Use the generated MCDM ranking tables and the sensitivity analysis plots as rigorous evidence to document the decision, thereby providing a clear audit trail for compliance and quality control.

5.4.1. Choosing the XAI Method in the Field of Hate Speech Detection

- The explanation contains information that is essential for me to understand the model’s decision. (Understandability)

- The explanation is useful to me for making better decisions or performing an action. (Usefulness)

- Based on the explanation, I have more confidence in the model’s decision. (Trustworthiness)

- The explanation provides sufficient information to explain how the system makes decisions. (Informativeness)

- I have a satisfied attitude towards the explanation of the model. (Satisfaction)

5.4.2. Choosing the XAI Method in the Field of Medicine

5.4.3. Choosing the XAI Method in Finance

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIS | Anti-Ideal Solution |

| ARAS | Additive Ratio Assessment |

| AS | Average Solution |

| BAA | Border Approximation Area |

| CDSS | Clinical Decision Support System |

| CODAS | Combinative Distance-based Assessment |

| CRITIC | Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation |

| EDAS | Evaluation Based on Distance from Average Solution |

| IS | Ideal Solution |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| MABAC | Multi-Attributive Border Approximation Area Comparison |

| MADM | Multi-Attribute Decision-Making |

| MARCOS | Measurement of Alternatives and Ranking according to Compromise Solution |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| MODM | Multi-Objective Decision-Making |

| ND | Negative Distance |

| NIS | Negative Ideal Solution |

| PD | Positive Distance |

| PROMETHEE II | Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment of Evaluations II |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| VIKOR | VIšeKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Rešenje |

| WASPAS | Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment |

| WSM | Weighted Sum Model |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

| Weight Change (δ) | W’1 | W’2 | W’3 | W’4 | W’5 | W’6 | W’7 | W’8 | W’9 | W’10 | W’11 | W’12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.4 | 0.036 | 0.0368 | 0.0434 | 0.0442 | 0.0421 | 0.045 | 0.0414 | 0.0451 | 0.0453 | 0.0451 | 0.0453 | 0.0437 |

| −0.358 | 0.035 | 0.0359 | 0.0434 | 0.0443 | 0.0419 | 0.0453 | 0.0412 | 0.0453 | 0.0455 | 0.0453 | 0.0455 | 0.0437 |

| −0.316 | 0.0337 | 0.0348 | 0.0434 | 0.0444 | 0.0416 | 0.0455 | 0.0408 | 0.0455 | 0.0458 | 0.0456 | 0.0458 | 0.0437 |

| −0.274 | 0.0319 | 0.0332 | 0.0434 | 0.0445 | 0.0413 | 0.0459 | 0.0403 | 0.0459 | 0.0463 | 0.046 | 0.0462 | 0.0438 |

| −0.232 | 0.0293 | 0.0309 | 0.0433 | 0.0448 | 0.0408 | 0.0465 | 0.0396 | 0.0465 | 0.0469 | 0.0466 | 0.0468 | 0.0438 |

| −0.189 | 0.0252 | 0.0272 | 0.0433 | 0.0452 | 0.04 | 0.0473 | 0.0385 | 0.0473 | 0.0479 | 0.0474 | 0.0478 | 0.0439 |

| −0.147 | 0.0177 | 0.0207 | 0.0432 | 0.0459 | 0.0386 | 0.0489 | 0.0365 | 0.0489 | 0.0496 | 0.0491 | 0.0496 | 0.0441 |

| −0.105 | 0.0002 | 0.0051 | 0.0431 | 0.0475 | 0.0353 | 0.0525 | 0.0317 | 0.0526 | 0.0538 | 0.0529 | 0.0537 | 0.0446 |

| −0.063 | 0.0644 | 0.0536 | 0.0294 | 0.039 | 0.0123 | 0.0501 | 0.0045 | 0.0502 | 0.0529 | 0.0508 | 0.0527 | 0.0327 |

| −0.021 | 0.1628 | 0.1492 | 0.0446 | 0.0325 | 0.0661 | 0.0185 | 0.0759 | 0.0184 | 0.015 | 0.0176 | 0.0153 | 0.0405 |

| 0.021 | 0.0849 | 0.0802 | 0.0439 | 0.0397 | 0.0513 | 0.0348 | 0.0548 | 0.0348 | 0.0336 | 0.0345 | 0.0337 | 0.0424 |

| 0.063 | 0.0686 | 0.0657 | 0.0437 | 0.0412 | 0.0482 | 0.0382 | 0.0503 | 0.0382 | 0.0375 | 0.038 | 0.0376 | 0.0428 |

| 0.105 | 0.0615 | 0.0594 | 0.0437 | 0.0418 | 0.0469 | 0.0397 | 0.0484 | 0.0397 | 0.0392 | 0.0396 | 0.0392 | 0.043 |

| 0.147 | 0.0575 | 0.0559 | 0.0436 | 0.0422 | 0.0461 | 0.0405 | 0.0473 | 0.0405 | 0.0401 | 0.0404 | 0.0402 | 0.0431 |

| 0.189 | 0.055 | 0.0537 | 0.0436 | 0.0424 | 0.0457 | 0.0411 | 0.0466 | 0.0411 | 0.0407 | 0.041 | 0.0408 | 0.0432 |

| 0.232 | 0.0532 | 0.0521 | 0.0436 | 0.0426 | 0.0453 | 0.0414 | 0.0461 | 0.0414 | 0.0412 | 0.0414 | 0.0412 | 0.0432 |

| 0.274 | 0.0519 | 0.051 | 0.0436 | 0.0427 | 0.0451 | 0.0417 | 0.0458 | 0.0417 | 0.0415 | 0.0417 | 0.0415 | 0.0433 |

| 0.316 | 0.0509 | 0.0501 | 0.0435 | 0.0428 | 0.0449 | 0.0419 | 0.0455 | 0.0419 | 0.0417 | 0.0419 | 0.0417 | 0.0433 |

| 0.358 | 0.0501 | 0.0494 | 0.0435 | 0.0429 | 0.0447 | 0.0421 | 0.0453 | 0.0421 | 0.0419 | 0.042 | 0.0419 | 0.0433 |

| 0.4 | 0.0495 | 0.0488 | 0.0435 | 0.0429 | 0.0446 | 0.0422 | 0.0451 | 0.0422 | 0.042 | 0.0422 | 0.0421 | 0.0433 |

| Weight Change (δ) | W’13 | W’14 | W’15 | W’16 | W’17 | W’18 | W’19 | W’20 | W’21 | W’22 | W’23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.4 | 0.0455 | 0.0451 | 0.0457 | 0.0442 | 0.0452 | 0.0447 | 0.0455 | 0.0447 | 0.0384 | 0.0427 | 0.045 |

| −0.358 | 0.0458 | 0.0453 | 0.0459 | 0.0443 | 0.0455 | 0.0448 | 0.0458 | 0.0449 | 0.0377 | 0.0426 | 0.0452 |

| −0.316 | 0.0462 | 0.0455 | 0.0463 | 0.0444 | 0.0458 | 0.045 | 0.0461 | 0.0451 | 0.0369 | 0.0425 | 0.0455 |

| −0.274 | 0.0467 | 0.0459 | 0.0468 | 0.0446 | 0.0462 | 0.0453 | 0.0466 | 0.0454 | 0.0356 | 0.0423 | 0.0459 |

| −0.232 | 0.0474 | 0.0465 | 0.0476 | 0.0448 | 0.0468 | 0.0457 | 0.0473 | 0.0458 | 0.0339 | 0.0421 | 0.0464 |

| −0.189 | 0.0485 | 0.0473 | 0.0488 | 0.0452 | 0.0478 | 0.0464 | 0.0484 | 0.0465 | 0.0311 | 0.0417 | 0.0472 |

| −0.147 | 0.0506 | 0.0489 | 0.0509 | 0.0459 | 0.0495 | 0.0475 | 0.0504 | 0.0478 | 0.0261 | 0.0409 | 0.0487 |

| −0.105 | 0.0554 | 0.0526 | 0.056 | 0.0475 | 0.0537 | 0.0503 | 0.0552 | 0.0507 | 0.0143 | 0.0392 | 0.0523 |

| −0.063 | 0.0564 | 0.0502 | 0.0577 | 0.039 | 0.0526 | 0.0453 | 0.0559 | 0.046 | 0.0336 | 0.021 | 0.0496 |

| −0.021 | 0.0107 | 0.0184 | 0.0089 | 0.0325 | 0.0154 | 0.0246 | 0.0112 | 0.0237 | 0.1239 | 0.0552 | 0.0191 |

| 0.021 | 0.0321 | 0.0348 | 0.0315 | 0.0397 | 0.0337 | 0.0369 | 0.0323 | 0.0366 | 0.0714 | 0.0476 | 0.035 |

| 0.063 | 0.0366 | 0.0382 | 0.0362 | 0.0412 | 0.0376 | 0.0395 | 0.0367 | 0.0393 | 0.0604 | 0.046 | 0.0384 |

| 0.105 | 0.0385 | 0.0397 | 0.0383 | 0.0418 | 0.0392 | 0.0406 | 0.0386 | 0.0405 | 0.0556 | 0.0453 | 0.0398 |

| 0.147 | 0.0396 | 0.0405 | 0.0394 | 0.0422 | 0.0402 | 0.0413 | 0.0397 | 0.0411 | 0.0529 | 0.0449 | 0.0406 |

| 0.189 | 0.0403 | 0.0411 | 0.0402 | 0.0424 | 0.0408 | 0.0417 | 0.0404 | 0.0416 | 0.0512 | 0.0446 | 0.0411 |

| 0.232 | 0.0408 | 0.0414 | 0.0407 | 0.0426 | 0.0412 | 0.0419 | 0.0408 | 0.0419 | 0.05 | 0.0444 | 0.0415 |

| 0.274 | 0.0412 | 0.0417 | 0.041 | 0.0427 | 0.0415 | 0.0421 | 0.0412 | 0.0421 | 0.0492 | 0.0443 | 0.0418 |

| 0.316 | 0.0414 | 0.0419 | 0.0413 | 0.0428 | 0.0417 | 0.0423 | 0.0415 | 0.0422 | 0.0485 | 0.0442 | 0.042 |

| 0.358 | 0.0416 | 0.0421 | 0.0415 | 0.0429 | 0.0419 | 0.0424 | 0.0417 | 0.0424 | 0.048 | 0.0441 | 0.0421 |

| 0.4 | 0.0418 | 0.0422 | 0.0417 | 0.0429 | 0.0421 | 0.0425 | 0.0418 | 0.0425 | 0.0475 | 0.0441 | 0.0422 |

| Weight Change (δ) | ARAS Rank | CODAS Rank | EDAS Rank | MABAC Rank | MARCOS Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.358 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.316 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.274 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.232 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.189 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.147 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.105 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.063 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| −0.021 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A3 > A4 > A1 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A4 > A3 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.021 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A3 > A1 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.063 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A3 > A1 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.105 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A3 > A1 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.147 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A3 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.189 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A3 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.232 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.274 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.316 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.358 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| Weight Change (δ) | PROMETHEE_II Rank | TOPSIS Rank | VIKOR Rank | WASPAS Rank | WSM Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| −0.358 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| −0.316 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.274 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.232 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.189 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.147 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A3 > A2 > A1 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.105 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 |

| −0.063 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| −0.021 | A2 > A1 > A4 > A3 | A2 > A4 > A1 > A3 | A2 > A4 > A1 > A3 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.021 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A4 > A3 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.063 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A2 > A1 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.105 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.147 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.189 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.232 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.274 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.316 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.358 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

| 0.4 | A1 > A3 > A2 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A4 > A3 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 | A1 > A2 > A3 > A4 |

References

- Gunning, D. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI); Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA): Arlington, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods. Entropy 2021, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Explanation in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Social Sciences. Artif. Intell. 2017, 267, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Khanna, R.; Koyejo, O.O. Examples Are Not Enough, Learn to Criticize! Criticism for Interpretability. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2016, 29, 2288–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards A Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.08608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, L.H.; Bau, D.; Yuan, B.Z.; Bajwa, A.; Specter, M.; Kagal, L. Explaining Explanations: An Overview of Interpretability of Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics, Turin, Italy, 1–4 October 2018; pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo Arrieta, A.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Garcia, S.; Gil-Lopez, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, Taxonomies, Opportunities and Challenges toward Responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking Inside the Black-Box: A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F.; Pedreschi, D. A Survey of Methods for Explaining Black Box Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 51, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Khan, J.A.; De Falco, I.; Sannino, G. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Importance, Use Domains, Stages, Output Shapes, and Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeire, T.; Laugel, T.; Renard, X.; Martens, D.; Detyniecki, M. How to Choose an Explainability Method? Towards a Methodical Implementation of XAI in Practice. In Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD 2021); Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1524, pp. 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable, 2nd ed. Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Carvalho, D.V.; Pereira, E.M.; Cardoso, J.S. Machine Learning Interpretability: A Survey on Methods and Metrics. Electronics 2019, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z.C. The Mythos of Model Interpretability. Commun. ACM 2018, 61, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-Cam: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, S.; Binder, A.; Montavon, G.; Klauschen, F.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. On Pixel-Wise Explanations for Non-Linear Classifier Decisions by Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikumar, A.; Greenside, P.; Kundaje, A. Learning Important Features Through Propagating Activation Differences. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Centre, Sydney, 6–11 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; KDD ’16. Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; NIPS’17. Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Anchors: High-Precision Model-Agnostic Explanations. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; AAAI Press: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 2018; pp. 1527–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep Inside Convolutional Networks: Visualising Image Classification Models and Saliency Maps. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014—Workshop Track Proceedings, Banff, AB, Canada, 14–16 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic Attribution for Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; Volume 7, pp. 5109–5118. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A.; Kapelner, A.; Bleich, J.; Pitkin, E. Peeking Inside the Black Box: Visualizing Statistical Learning With Plots of Individual Conditional Expectation. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2015, 24, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Statist. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apley, D.W.; Zhu, J. Visualizing the Effects of Predictor Variables in Black Box Supervised Learning Models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2016, 82, 1059–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilone, G.; Longo, L. Classification of Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods through Their Output Formats. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2021, 3, 615–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Counterfactual Explanations Without Opening the Black Box: Automated Decisions and the GDPR. Harv. J. Law Technol. 2017, 31, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilone, G.; Longo, L. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirqueira, D.; Nedbal, D.; Helfert, M.; Bezbradica, M. Scenario-Based Requirements Elicitation for User-Centric Explainable AI: A Case in Fraud Detection. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. CD-MAKE 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12279, pp. 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.T. Explainability Scenarios: Towards Scenario-Based XAI Design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Proceedings IUI, Marina del Ray, CA, USA, 17–20 March 2019; pp. 252–257, Part. F147615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, U.; Xiang, A.; Sharma, S.; Weller, A.; Taly, A.; Jia, Y.; Ghosh, J.; Puri, R.; Moura, J.M.F.; Eckersley, P. Explainable Machine Learning in Deployment. In Proceedings of the FAT* 2020—Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.; Oster, D.; Speith, T.; Hermanns, H.; Kästner, L.; Schmidt, E.; Sesing, A.; Baum, K. What Do We Want from Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)?—A Stakeholder Perspective on XAI and a Conceptual Model Guiding Interdisciplinary XAI Research. Artif. Intell. 2021, 296, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, V.; Bellamy, R.K.E.; Chen, P.-Y.; Dhurandhar, A.; Hind, M.; Hoffman, S.C.; Houde, S.; Liao, Q.V.; Luss, R.; Mojsilović, A.; et al. One Explanation Does Not Fit All: A Toolkit and Taxonomy of AI Explainability Techniques. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, K.; Flach, P. Explainability Fact Sheets: A Framework for Systematic Assessment of Explainable Approaches. In Proceedings of the FAT* 2020—Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugny, R.; Aligon, J.; Chevalier, M.; Jimenez, G.R.; Teste, O. Why Should I Choose You? AutoXAI: A Framework for Selecting and Tuning EXplainable AI Solutions. In International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Proceedings; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Harborne, D.; Tomsett, R.; Galetic, V.; Quintana-Amate, S.; Nottle, A.; Preece, A. A Systematic Method to Understand Requirements for Explainable AI (XAI) Systems. In Proceedings of the IJCAI Workshop on eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI 2019), Macau, China, 11 August 2019; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Adomavicius, G.; Mobasher, B.; Ricci, F.; Tuzhilin, A. Context-Aware Recommender Systems. AI Mag. 2011, 32, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhao, K.; Chu, X. AutoML: A Survey of the State-of-the-Art. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 212, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullum, M.; Sjødin, J.; Prabhu, R.; Løland, A. EXplego: An Interactive Tool That Helps You Select Appropriate XAI-Methods for Your Explainability Needs. In Proceedings of the xAI (Late-breaking Work, Demos, Doctoral Consortium), CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Aachen, Germany, 26–28 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nauta, M.; Trienes, J.; Nguyen, E.; Peters, M.; Schmitt, Y.; Schlötterer, J.; Van Keulen, M.; Seifert, C. From Anecdotal Evidence to Quantitative Evaluation Methods: A Systematic Review on Evaluating Explainable AI.; From Anecdotal Evidence to Quantitative Evaluation Methods: A Systematic Review on Evaluating Explainable AI. ACM J. 2023, 55, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitruț, O.; Moise, G.; Moldoveanu, A.; Moldoveanu, F.; Leordeanu, M.; Petrescu, L. Clarity in Complexity: How Aggregating Explanations Resolves the Disagreement Problem. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, L.; Hansen, L.K. Aggregating Explanation Methods for Stable and Robust Explainability. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.00519. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Colombo, E.R.; Raimundo, M.M. Multi-Criteria Rank-Based Aggregation for Explainable AI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.24612. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorabaee, M.K.; Kazimieras, Z.; Olfat, L.; Turskis, Z. Multi-Criteria Inventory Classification Using a New Method of Evaluation Based on Distance from Average Solution (EDAS). Informatica 2015, 26, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.-L.; Yoon, K. Methods for Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; pp. 58–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.; Kaklauskas, A.; Šarka, V. The New Method of Multicriteria Complex Proportional Assessment of Projects. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 1994, 1, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B. The Promethee Methods for MCDM; The Promcalc, Gaia and Bankadviser Software. In Readings in Multiple Criteria Decision Aid; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; pp. 216–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z. A New Additive Ratio Assessment (ARAS) Method in Multicriteria Decision-Making. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2010, 16, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Zarate, P.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z. A Combined Compromise Solution (CoCoSo) Method for Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Problems. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2501–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorabaee, M.K.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Turkis, Z.; Antucheviciene, J. A New Combinative Distance-Based Assessment (Codas) Method for Multi-Criteria Decision-Making. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2016, 50, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pamučar, D.; Ćirović, G. The Selection of Transport and Handling Resources in Logistics Centers Using Multi-Attributive Border Approximation Area Comparison (MABAC). Expert. Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 3016–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderková, V.; Babič, F.; Paraličová, Z.; Javorská, D. Intelligent System Using Data to Support Decision-Making. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, J. Bordas Text „Mémoire Sur Les Élections Au Scrutin “von 1784: Einige Einführende Bemerkungen. In Jahrbuch für Handlungs-und Entscheidungstheorie; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodria, F.; Giannotti, F.; Guidotti, R.; Naretto, F.; Pedreschi, D.; Rinzivillo, S. Benchmarking and Survey of Explanation Methods for Black Box Models. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 37, 1719–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, N.; Huber, M.F. A Survey on the Explainability of Supervised Machine Learning. MF Huber J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2021, 70, 245–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Melis, D.; Jaakkola, T.S. Towards Robust Interpretability with Self-Explaining Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; NIPS’18; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 7786–7795. [Google Scholar]

- Moraffah, R.; Karami, M.; Guo, R.; Raglin, A.; Liu, H. Causal Interpretability for Machine Learning-Problems, Methods and Evaluation. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2020, 22, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.K.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Suggala, A.S.; Inouye, D.I.; Ravikumar, P. On the (In)Fidelity and Sensitivity for Explanations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2019, 32, 10967–10978. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.-N.; Wang, G.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z.; Cai, X.; Du, M.; Hu, X. Efficient XAI Techniques: A Taxonomic Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, W.; Montavon, G.; Lapuschkin, S.; Anders, C.J.; Müller, K.R. Explaining Deep Neural Networks and Beyond: A Review of Methods and Applications. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, W.; Wiegand, T.; Müller, K.-R. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Understanding, Visualizing and Interpreting Deep Learning Models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.08296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darias, J.M.; Bayrak, B.; Caro-Martínez, M.; Díaz-Agudo, B.; Recio-Garcia, J.A. An Empirical Analysis of User Preferences Regarding XAI Metrics. In Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development. ICCBR 2024; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14775, pp. 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, M.; Chen, J.; Chai, Y.; Lakkaraju, H.; Xiong, H. M4: A Unified XAI Benchmark for Faithfulness Evaluation of Feature Attribution Methods across Metrics, Modalities and Models. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; NIPS ’23. Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hedström, A.; Weber, L.; Bareeva, D.; Krakowczyk, D.; Motzkus, F.; Samek, W.; Lapuschkin, S.; Höhne, M.M.C. Quantus: An Explainable AI Toolkit for Responsible Evaluation of Neural Network Explanations and Beyond. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sithakoul, S.; Meftah, S.; Feutry, C. BEExAI: Benchmark to Evaluate Explainable AI. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 2153, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canha, D.; Kubler, S.; Främling, K.; Fagherazzi, G. A Functionally-Grounded Benchmark Framework for XAI Methods: Insights and Foundations from a Systematic Literature Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.R.; Emami, S.; Hollins, M.D.; Wong, T.C.H.; Villalobos Sánchez, C.I.; Toni, F.; Zhang, D.; Dejl, A. XAI-Units: Benchmarking Explainability Methods with Unit Tests. In ACMF AccT 2025—Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Athens, Greece, 23–26 June 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 2892–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaid, M.K.; Hüllermeier, E.; Rabus, M.; Krestel, R. Do We Need Another Explainable AI Method? Toward Unifying Post-Hoc XAI Evaluation Methods into an Interactive and Multi-Dimensional Benchmark. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.14160. [Google Scholar]

- Moiseev, I.; Balabaeva, K.; Kovalchuk, S. Open and Extensible Benchmark for Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods. Algorithms 2025, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Khandagale, S.; White, C.; Neiswanger, W. Synthetic Benchmarks for Scientific Research in Explainable Machine Learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, C.; Ley, D.; Krishna, S.; Saxena, E.; Pawelczyk, M.; Johnson, N.; Puri, I.; Zitnik, M.; Lakkaraju, H. OpenXAI: Towards a Transparent Evaluation of Model Explanations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 15784–15799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Gu, S.; Jiang, T.; Pan, B.; Bai, G.; Zhao, L. Saliency-Bench: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Evaluating Visual Explanations. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V.2, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2023; Volume 1, pp. 5924–5935. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Lai, V.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Hamilton, P.; Ljubenkov, D.; Lakkaraju, H.; Tan, C. OpenHEXAI: An Open-Source Framework for Human-Centered Evaluation of Explainable Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05565. [Google Scholar]

- Aechtner, J.; Cabrera, L.; Katwal, D.; Onghena, P.; Valenzuela, D.P.; Wilbik, A. Comparing User Perception of Explanations Developed with XAI Methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruldoss, M.; Lakshmi, T.M.; Venkatesan, V.P. A Survey on Multi Criteria Decision Making Methods and Its Applications. Am. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 1, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez, M.; Hester, P.T. An Analysis of Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 10, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ryciuk, U.; Kiryluk, H.; Hajduk, S. Multi-Criteria Analysis in the Decision-Making Approach for the Linear Ordering of Urban Transport Based on TOPSIS Technique. Energies 2021, 15, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczkiewicz, A.; Atróbski, J.W.; Kizielewicz, B.; Sałabun, W. Towards Objectification of Multi-Criteria Assessments: A Comparative Study on MCDA Methods. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2–5 September 2021; Volume 25, pp. 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizyldayeva, U.; Vlasov, O.; Kuandykov, A.A.; Akhmetov, T.B. Multi-Criteria Decision Support Systems. Comparative Analysis. Middle-East. J. Sci. Res. 2013, 16, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Habenicht, W.; Scheubrein, B.; Scheubrein, R. Multiple-Criteria Decision Making. Optim. Oper. Res. 2002, 4, 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Raut, R.D.; Rofin, T.M.; Chakraborty, S. A Comprehensive and Systematic Review of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods and Applications in Healthcare. Healthc. Anal. 2023, 4, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohekar, S.D.; Ramachandran, M. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Making to Sustainable Energy Planning—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic Hierarchy Process Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Diakoulaki, D.; Mavrotas, G.; Papayannakis, L. Determining Objective Weights in Multiple Criteria Problems: The Critic Method. Comput. Ops Res. 1995, 22, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stević, Ž.; Pamučar, D.; Puška, A.; Chatterjee, P. Sustainable Supplier Selection in Healthcare Industries Using a New MCDM Method: Measurement of Alternatives and Ranking According to COmpromise Solution (MARCOS). Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 140, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiří, M. The Robustness of TOPSIS Results Using Sensitivity Analysis Based on Weight Tuning. IFMBE Proc. 2018, 68, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckstein, L.; Opricovic, S. Multiobjective Optimization in River Basin Development. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z.; Antucheviciene, J.; Zakarevicius, A. Optimization of Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment. Elektron. Ir Elektrotechnika 2012, 122, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishburn, P.C.; Murphy, A.H.; Isaacs, H.H. Sensitivity of Decisions to Probability Estimation Errors: A Reexamination. Oper. Res. 1968, 16, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrumbelj, E.; Kononenko, I. Explaining Prediction Models and Individual Predictions with Feature Contributions. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2013, 41, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, P.W.; Liang, P. Understanding Black-Box Predictions via Influence Functions. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; Volume 4, pp. 2976–2987. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Wattenberg, M.; Gilmer, J.; Cai, C.; Wexler, J.; Viegas, F.; Sayres, R. Interpretability Beyond Feature Attribution: Quantitative Testing with Concept Activation Vectors (TCAV). In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Volume 6, pp. 4186–4195. [Google Scholar]

- Montavon, G.; Bach, S.; Binder, A.; Samek, W.; Müller, K.-R. Explaining NonLinear Classification Decisions with Deep Taylor Decomposition. Pattern Recognit. 2015, 65, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014. ECCV 2014; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; Volume 8689, pp. 818–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilkov, D.; Thorat, N.; Kim, B.; Viégas, F.; Wattenberg, M. SmoothGrad: Removing Noise by Adding Noise. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermans, P.J.; Schütt, K.T.; Alber, M.; Müller, K.R.; Erhan, D.; Kim, B.; Dähne, S. Learning How to Explain Neural Networks: PatternNet and PatternAttribution. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2018—Conference Track Proceedings, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Springenberg, J.T.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Brox, T.; Riedmiller, M. Striving for Simplicity: The All Convolutional Net. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015—Workshop Track Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, R.C.; Vedaldi, A. Interpretable Explanations of Black Boxes by Meaningful Perturbation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 3449–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ba, J.L.; Kiros, R.; Cho, K.; Courville, A.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Zemel, R.S.; Bengio, Y. Show, Attend and Tell: Neural Image Caption Generation with Visual Attention. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2015, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; Volume 3, pp. 2048–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Erhan, D.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Understanding Representations Learned in Deep Architectures; Department Dinformatique et Recherche Operationnelle, University of Montreal: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization. 2016, pp 2921–2929. Available online: http://cnnlocalization.csail.mit.edu (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Lei, T.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. Rationalizing Neural Predictions. In EMNLP 2016—Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Proceedings, Austin, TX, USA, 1–5 November 2016; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Pedreschi, D.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F. Local Rule-Based Explanations of Black Box Decision Systems. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.10820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zintgraf, L.M.; Cohen, T.S.; Adel, T.; Welling, M. Visualizing Deep Neural Network Decisions: Prediction Difference Analysis. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2017—Conference Track Proceedings, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Petsiuk, V.; Das, A.; Saenko, K. RISE: Randomized Input Sampling for Explanation of Black-Box Models. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2018, BMVC 2018, Newcastle, UK, 3–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dhurandhar, A.; Chen, P.-Y.; Luss, R.; Tu, C.-C.; Ting, P.; Shanmugam, K.; Das, P. Explanations Based on the Missing: Towards Contrastive Explanations with Pertinent Negatives. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; NIPS’18. Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 590–601. [Google Scholar]

- Van Looveren, A.; Klaise, J. Interpretable Counterfactual Explanations Guided by Prototypes. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 12976, pp. 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothilal, R.K.; Sharma, A.; Tan, C. Explaining Machine Learning Classifiers through Diverse Counterfactual Explanations. In FAT* 2020—Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Wexler, J.; Zou, J.; Kim, B. Towards Automatic Concept-Based Explanations. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 9277–9286. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, C.K.; Kim, B.; Arik, S.; Li, C.L.; Pfister, T.; Ravikumar, P. On Completeness-Aware Concept-Based Explanations in Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; NIPS ’20. Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 20554–20565. [Google Scholar]

- Frosst, N.; Hinton, G. Distilling a Neural Network into a Soft Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Comprehensibility and Explanation in AI and ML 2017 Co-Located with 16th International Conference of the Italian Association for Artificial Intelligence (AI*IA 2017), CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Bari, Italy, 16–17 November 2017; Volume 2071. [Google Scholar]

- Främling, K.; Graillot, D. Extracting Explanations from Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the ICANN’95 Conference, Paris, France, 9–13 October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yosinski, J.; Clune, J.; Nguyen, A.; Fuchs, T.; Lipson, H. Understanding Neural Networks Through Deep Visualization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.06579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.; Falk, C.; Friedler, S.A.; Nix, T.; Rybeck, G.; Scheidegger, C.; Smith, B.; Venkatasubramanian, S. Auditing Black-Box Models for Indirect Influence. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2016, 54, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, D.; Zhu, J.Y.; Strobelt, H.; Zhou, B.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Freeman, W.T.; Torralba, A. GAN Dissection: Visualizing and Understanding Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2019, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Poyiadzi, R.; Sokol, K.; Santos-Rodriguez, R.; De Bie, T.; Flach, P. FACE: Feasible and Actionable Counterfactual Explanations. In AIES 2020—Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, New York, NY, USA, 7–8 February 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Melnick, L.; Frosst, N.; Zhang, X.; Lengerich, B.; Caruana, R.; Hinton, G.E. Neural Additive Models: Interpretable Machine Learning with Neural Nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2020, 6, 4699–4711. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, Y.; Qu, H.; Bertini, E. RuleMatrix: Visualizing and Understanding Classifiers with Rules. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2019, 25, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized Gradient-Based Visual Explanations for Deep Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, WACV 2018, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Song, L.; Wainwright, M.J.; Jordan, M.I. Learning to Explain: An Information-Theoretic Perspective on Model Interpretation. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Volume 2, pp. 1386–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Plumb, G.; Molitor, D.; Talwalkar, A. Model Agnostic Supervised Local Explanations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2018, 31, 2515–2524. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, A.; Toloşi, L.; Sander, O.; Lengauer, T. Permutation Importance: A Corrected Feature Importance Measure. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniak, M.; Biecek, P. Explanations of Model Predictions with Live and BreakDown Packages. R. J. 2018, 10, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Matwin, S.; Pedreschi, D. Explaining Image Classifiers Generating Exemplars and Counter-Exemplars from Latent Representations. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 34, pp. 13665–13668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandl, S.; Molnar, C.; Binder, M.; Bischl, B. Multi-Objective Counterfactual Explanations. In Parallel Problem Solving from Nature –PPSN XVI; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12269, pp. 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D.; Provost, F. Explaining Data-Driven Document Classifications1. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2014, 38, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yamada, M.; Tian, Y.; Singh, D.; Chang, Y. GraphLIME: Local Interpretable Model Explanations for Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 35, 6968–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzu, M.; Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Turini, F. Global Explanations with Local Scoring. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 1167, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Justicia, A.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Martínez, S.; Sánchez, D. Machine Learning Explainability via Microaggregation and Shallow Decision Trees. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, G.; Molnar, C.; Bischl, B. Visualizing the Feature Importance for Black Box Models. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11051, pp. 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Sen, S.; Zick, Y. Algorithmic Transparency via Quantitative Input Influence: Theory and Experiments with Learning Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2016, San Jose, CA, USA, 23–25 May 2016; pp. 598–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucic, A.; Oosterhuis, H.; Haned, H.; de Rijke, M. FOCUS: Flexible Optimizable Counterfactual Explanations for Tree Ensembles. In Proceedings of the 36th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2022, Online, 22 February–1 March 2019; Volume 36, pp. 5313–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, D.; Tan, C.; Sharma, A. Preserving Causal Constraints in Counterfactual Explanations for Machine Learning Classifiers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.03277. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, C. Efficient Search for Diverse Coherent Explanations. In FAT* 2019—Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, B.; Spangher, A.; Liu, Y. Actionable Recourse in Linear Classification. In FAT* 2019—Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, K.; Takagi, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Arimura, H. DACE: Distribution-Aware Counterfactual Explanation by Mixed-Integer Linear Optimization. IJCAI Int. Jt. Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 2855–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.H.; Barthe, G.; Balle, B.; Valera, I. Model-Agnostic Counterfactual Explanations for Consequential Decisions. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 108, 895–905. [Google Scholar]

- Pawelczyk, M.; Broelemann, K.; Kasneci, G. Learning Model-Agnostic Counterfactual Explanations for Tabular Data. In Web Conference 2020—Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, WWW 2020, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 3126–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, G.; Lee, Y.C.; Albarghouthi, A. Synthesizing Action Sequences for Modifying Model Decisions. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 34, pp. 5462–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Ming, Y.; Qu, H. DECE: Decision Explorer with Counterfactual Explanations for Machine Learning Models. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 27, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.H.; Schölkopf, B.; Valera, I. Algorithmic Recourse: From Counterfactual Explanations to Interventions. In FAccT 2021—Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event/Toronto, Canada, 3–10 March 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; pp. 353–362. [CrossRef]

- Laugel, T.; Lesot, M.-J.; Marsala, C.; Renard, X.; Detyniecki, M. Inverse Classification for Comparison-Based Interpretability in Machine Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.08443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henderson, J.; Ghosh, J. CERTIFAI: A Common Framework to Provide Explanations and Analyse the Fairness and Robustness of Black-Box Models. In AIES 2020—Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Madrid, Spain, 20–22 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, O.; Holter, S.; Yuan, J.; Bertini, E. ViCE: Visual counterfactual explanations for machine learning models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Proceedings IUI 2020, Cagliari, Italy, 24–27 March 2020; pp. 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucic, A.; Haned, H.; de Rijke, M. Why Does My Model Fail? Contrastive Local Explanations for Retail Forecasting. In FAT* 2020—Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon, Y.; Martens, D.; Provost, F.; Evgeniou, T. A Comparison of Instance-Level Counterfactual Explanation Algorithms for Behavioral and Textual Data: SEDC, LIME-C and SHAP-C. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 2020, 14, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; D’Avila Garcez, A. Measurable Counterfactual Local Explanations for Any Classifier. Front. Artif. Intell. Appl. 2019, 325, 2529–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.; Bourgeois, D.; You, J.; Zitnik, M.; Leskovec, J. GNNExplainer: Generating Explanations for Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 9244–9255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wiens, J.; Lundberg, S. Shapley Flow: A Graph-Based Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 130, 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi, O.; Rokach, L. Explainable Decision Forest: Transforming a Decision Forest into an Interpretable Tree. Inf. Fusion 2020, 61, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatwell, J.; Gaber, M.M.; Azad, R.M.A. CHIRPS: Explaining Random Forest Classification. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 5747–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, D.; Bergmeir, C.; Buntine, W. LoRMIkA: Local Rule-Based Model Interpretability with k-Optimal Associations. Inf. Sci. (N. Y.) 2020, 540, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loor, M.; De Tré, G. Contextualizing Support Vector Machine Predictions. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2020, 13, 1483–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Mueller, K.; Chen, X. Beyond Saliency: Understanding Convolutional Neural Networks from Saliency Prediction on Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation. Image Vis. Comput. 2019, 83–84, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.R.; Khan, N.M. DLIME: A Deterministic Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations Approach for Computer-Aided Diagnosis Systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.10263. [Google Scholar]

- Mollas, I.; Bassiliades, N.; Tsoumakas, G. LioNets: Local Interpretation of Neural Networks through Penultimate Layer Decoding. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 1167, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapishnikov, A.; Bolukbasi, T.; Viegas, F.; Terry, M. XRAI: Better Attributions Through Regions. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 4947–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampridis, O.; Guidotti, R.; Ruggieri, S. Explaining Sentiment Classification with Synthetic Exemplars and Counter-Exemplars. In Discovery Science. DS 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12323, pp. 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, B.; Strobelt, H.; Gehrmann, S. exBERT: A Visual Analysis Tool to Explore Learned Representations in Transformers Models. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacovi, A.; Shalom, O.S.; Goldberg, Y. Understanding Convolutional Neural Networks for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the EMNLP 2018—2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, Proceedings of the 1st Workshop, Brussels, Belgium, 1 November 2018; pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, Q.; Qiu, Q.; Jiao, J. Weakly Supervised Instance Segmentation Using Class Peak Response. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–20 June 2018; pp. 3791–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Kamnitsas, K.; Ancha, S.; Nanavati, J.; Cottrell, G.; Criminisi, A.; Nori, A. Autofocus Layer for Semantic Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11072, pp. 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, A.; Aleksejeva, L.; Jumutc, V.; Borisov, A. Classification Tree Extraction from Trained Artificial Neural Networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 104, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.; Thomason, J.; Tansey, W. Interpreting Black Box Models via Hypothesis Testing. In FODS 2020—Proceedings of the 2020 ACM-IMS Foundations of Data Science Conference, Virtual Event, 19–20 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Modarres, C.; Louie, M.; Paisley, J. Global Explanations of Neural Network: Mapping the Landscape of Predictions. In AIES 2019—Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengerich, B.J.; Konam, S.; Xing, E.P.; Rosenthal, S.; Veloso, M. Towards Visual Explanations for Convolutional Neural Networks via Input Resampling. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.09641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S. InterpNET: Neural Introspection for Interpretable Deep Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.09511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Manupriya, P.; Sarkar, A.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Neural Network Attributions: A Causal Perspective. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 1660–1676. [Google Scholar]

- Panigutti, C.; Perotti, A.; Pedreschi, D. Doctor XAI An Ontology-Based Approach to Black-Box Sequential Data Classification Explanations. In FAT* 2020—Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, K.; Takagi, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Ike, Y.; Uemura, K.; Arimura, H. Ordered Counterfactual Explanation by Mixed-Integer Linear Optimization. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11564–11574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, E.M.; Keane, M.T. On Generating Plausible Counterfactual and Semi-Factual Explanations for Deep Learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11575–11585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Heer, J.; Weld, D.S. Polyjuice: Generating Counterfactuals for Explaining, Evaluating, and Improving Models. In ACL-IJCNLP 2021—59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Proceedings of the Conference, Online, 1–6 August 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 6707–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, M.; Geng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Suciu, D. GeCo: Quality Counterfactual Explanations in Real Time. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2021, 14, 1681–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.R.; Martín de Diego, I.; Aceña, V.; Fernández-Isabel, A.; Moguerza, J.M. Random Forest Explainability Using Counterfactual Sets. Inf. Fusion 2020, 63, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, J.; Pushkarna, M.; Bolukbasi, T.; Wattenberg, M.; Viegas, F.; Wilson, J. The What-If Tool: Interactive Probing of Machine Learning Models. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 26, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazimatin, A.; Balalau, O.; Roy, R.S.; Weikum, G. Prince: Provider-Side Interpretability with Counterfactual Explanations in Recommender Systems. In WSDM 2020—Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Houston, TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Palacios, C.; Munoz-Romero, S.; Rojo-Alvarez, J.L. Cold-Start Promotional Sales Forecasting through Gradient Boosted-Based Contrastive Explanations. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 137574–137586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, M.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, S.; Mardziel, P.; Hu, X. Score-CAM: Score-Weighted Visual Explanations for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoukou, S.I.; Brunel, N.J.-B.; Salaün, T. The Shapley Value of Coalition of Variables Provides Better Explanations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.13342. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Sturm, B.L.; Dixon, S. Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations for Music Content Analysis. In Proceedings of the 18th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference, Suzhou, China, 23–27 October 2017; pp. 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, S.H.; Refsgaard, H.H.F.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Clemmensen, L.H. Forest Floor Visualizations of Random Forests. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.09196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, L.; Hinselmann, G.; Jahn, A.; Zell, A. Interpreting Linear Support Vector Machine Models with Heat Map Molecule Coloring. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, A.R.; Wang, S.; Zhu, S.C. CoCoX: Generating Conceptual and Counterfactual Explanations via Fault-Lines. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 34, pp. 2594–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Cauteruccio, F.; Corradini, E.; Marchetti, M.; Terracina, G.; Ursino, D.; Virgili, L. A Model-Agnostic, Network Theory-Based Framework for Supporting XAI on Classifiers. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Schnake, T.; Eberle, O.; Montavon, G.; Müller, K.R.; Wolf, L. XAI for Transformers: Better Explanations through Conservative Propagation. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 162, 435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, M.; Samwald, M. Post-Hoc Explanation of Black-Box Classifiers Using Confident Itemsets. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2021, 165, 113941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousselham, W.; Boggust, A.; Chaybouti, S.; Strobelt, H.; Kuehne, H. LeGrad: An Explainability Method for Vision Transformers via Feature Formation Sensitivity. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Amara, K.; Sevastjanova, R.; El-Assady, M. SyntaxShap: Syntax-Aware Explainability Method for Text Generation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Kerrville, TX, USA, 2024; pp. 4551–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Parimala, N. A Sensitivity Analysis on Weight Sum Method MCDM Approach for Product Recommendation. In Distributed Computing and Internet Technology. ICDCIT 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11319, pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiela, D.; Firooz, H.; Mohan, A.; Goswami, V.; Singh, A.; Ringshia, P.; Testuggine, D. The Hateful Memes Challenge: Detecting Hate Speech in Multimodal Memes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2020, 33, 2611–2624. [Google Scholar]

- Statlog (German Credit Data)—UCI Machine Learning Repository. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/144/statlog+german+credit+data (accessed on 31 October 2025).

| Benchmark | XAI Methods | Metrics | Data Type | Supported Models | Extensible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M4 [63] | LIME | Faithfulness | IMG | ResNets | Yes |

| Integrated Gradient | TXT | MobileNets | |||

| SmoothGrad | VGG | ||||

| GradCAM | ViT | ||||

| Generic Attribution | MAE-ViT-base | ||||

| Bidirectional Explanations | BERTs | ||||

| DistilBERT | |||||

| ERNIE-2.0-base | |||||

| RoBERTa | |||||

| Quantus [64] | GradientShap | Faithfulness | IMG | NN | Yes |

| IntegratedGradients | Robustness | TAB | |||

| DeepLift | Localisation | TS | |||

| DeepLiftShap | Complexity | ||||

| InputXGradient | Randomisation (Sensitivity) | ||||

| Saliency | Axiomatic | ||||

| Feature Ablation | |||||

| Deconvolution | |||||

| Feature Permutation | |||||

| LIME | |||||

| Kernel SHAP | |||||

| LRP | |||||

| Gradient | |||||

| Occlusion | |||||

| Layer GradCam | |||||

| Guided GradCam | |||||

| Layer Conductance | |||||

| Layer Activation | |||||

| Internal Influence | |||||

| Layer GradientXActivation | |||||

| Control Var. Sobel Filter | |||||

| Control Var. Constant | |||||

| Control Var. Random Uniform | |||||

| Vanilla Gradients | |||||

| Gradients Input | |||||

| Occlusion Sensitivity | |||||

| GradCAM | |||||

| SmoothGrad | |||||

| BEExAI [65] | Feature Ablation | Sensitivity | TAB | Linear Regression | Yes |

| LIME | Infidelity | Logistic Regression | |||

| Shapley Value Sampling | Comprehensiveness | Random Forest | |||

| Kernel SHAP | Sufficiency | Decision Tree | |||

| Integrated Gradients | Faithfulness Correlation | Gradient Boosting | |||

| Saliency | AUC-TP | XGBoost | |||

| DeepLift | Monotonicity | Dense Neural Network | |||

| InputXGradient | Complexity | ||||

| Sparseness | |||||

| FUNCXAI-11 [66] | Not defined | Representativeness | TAB | Not defined | Yes |

| Structure | IMG | ||||

| Selectivity | TXT | ||||

| Contrastivity | |||||

| Interactivity | |||||

| Fidelity | |||||

| Faithfulness | |||||

| Truthfulness | |||||

| Stability | |||||

| (Un)certainty | |||||

| Speed | |||||

| XAI UNITS [67] | DeepLIFT | Infidelity | TAB | MLP | Yes |

| Shapley Value Sampling | Sensitivity | IMG | CNN | ||

| InputXGradient | MSE | TXT | ViT | ||

| IntegratedGradients | Mask Error | LLM | |||

| LIME | Mask Proportion Image | ||||

| Kernel SHAP | Mask Proportion Text | ||||

| Feature Ablation | |||||

| Gradient SHAP | |||||

| DeepLIFT SHAP | |||||

| Saliency | |||||

| Deconvolution | |||||

| Guided Backpropagation | |||||

| Guided GradCAM | |||||

| Feature Permutation | |||||

| Occlusion | |||||

| Compare-xAI [68] | Exact Shapley Values | Comprehensibility: | TAB | Not defined | Yes |

| Kernel SHAP | • Fidelity | ||||

| LIME | • Fragility | ||||

| MAPLE | • Stability | ||||

| Partition | • Simplicity | ||||

| Permutation | • Stress tests | ||||

| Permutation Partition | Portability | ||||

| Saabas | Average execution time | ||||

| SAGE | |||||

| SHAP Interaction | |||||

| Shapley Taylor Interaction | |||||

| Tree SHAP | |||||

| Tree SHAP Approximation | |||||

| XAIB [69] | Constant | Model Randomization Check (MRC) | TAB | SVC | Yes |

| LIME | Small Noise Check (SNC) | MLP | |||

| SHAP | Label Difference (LD) | KNN | |||

| KNN | Different Methods Agreement (DMA) | ||||

| Sparsity (SP) | |||||

| Covariate Regularity (CVR) | |||||

| Target Discriminativeness (TGD) | |||||

| Same Class Check (SCC) | |||||

| XAI-Bench [70] | LIME | Faithfulness | TAB | Linear Regression | No |

| SHAP | Monotonicity | Decision Tree | |||

| MAPLE | ROAR | MLP | |||

| SHAPR | GT-Shapley | ||||

| BF-SHAP | Infidelity | ||||

| L2X | |||||

| BreakDown | |||||

| OpenXAI [71] | LIME | Faithfulness: | TAB | NN | Yes |

| SHAP | • Feature Agreement (FA) | Logistic regression | |||

| Vanilla Gradients | • Rank Agreement (RA) | ||||

| InputXGradient | • Sign Agreement (SA) | ||||

| SmoothGrad | • Signed Rank Agreement (SRA) | ||||

| Integrated Gradients | • Rank Correlation (RC) | ||||

| • Pairwise Rank Agreement (PRA) | |||||

| • Prediction Gap on Important feature perturbation (PGI) | |||||

| • Prediction Gap on Unimportant feature perturbation (PGU) | |||||

| Stability: | |||||

| • Relative Input Stability (RIS) | |||||

| • Relative Representation Stability (RRS) | |||||

| • Relative Output Stability (ROS) | |||||

| Fairness | |||||

| Saliency bench [72] | Grad CAM | mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) | IMG | CNN | Yes |

| GradCAM++ | Pointing Game (PG) | ViT | |||

| Integrated Gradients | Insertion (iAUC) | ||||

| InputXGradient | Precision | ||||

| Occlusion | Recall | ||||

| RISE | |||||

| OpenHEXAI [73] | LIME | Accuracy | TAB | NN | Partially |

| SHAP | F1 | Logistic regression | |||

| Vanilla Gradients | AVG Time | ||||

| InputXGradient | Over-Reliance | ||||

| SmoothGrad | Under-Reliance | ||||

| Integrated Gradients | Average Absolute Odds Difference (AAOD) | ||||

| Equal Opportunity Difference (EOD) | |||||

| Method | Year | Portability | Model | Scope | Data Type | Problem | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIME [18] | 2016 | MA | L | TAB, IMG, TXT | C, R | N, V | |

| SHAP [19] | 2017 | MA | L, G | TAB, IMG, TXT | C, R | N, V | |

| Shapley values [91] | 2014 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | N | |

| LRP [16] | 2015 | MS | DNN | L | IMG, TXT | C | N, V |

| Saliency Maps [21] | 2013 | MS | DNN | L | IMG, TXT | C | V |

| Grad-CAM [15] | 2019 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| IntGrad [22] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG, TXT | C | N, V |

| Anchors [20] | 2018 | MA | L | TAB, TXT | C | RU | |

| DeepLIFT [17] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG, TXT | C | N, V |

| Influence Functions [92] | 2017 | MA | L | IMG | C | N, V | |

| TCAV [93] | 2017 | MA | G | IMG | C | N | |

| ICE [23] | 2015 | MA | G | TAB | C, R | V | |

| DTD [94] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| DeconvNet [95] | 2013 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| SmoothGrad [96] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| PDP [24] | 2001 | MA | G | TAB | C, R | V | |

| PatternAttribution [97] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| Guided BackProp [98] | 2014 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| Meaningful Perturbation [99] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| PatternNet [97] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | N, V |

| Show, Attend and Tell [100] | 2015 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | T, V |

| Activation Maximization [101] | 2010 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| CAM [102] | 2015 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| Rationales [103] | 2016 | MS | NLP model | L | TXT | C | T |

| LORE [104] | 2018 | MA | L | TAB | C | RU | |

| PDA [105] | 2017 | MS | DNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| RISE [106] | 2018 | MA | L | IMG | C | N, V | |

| CEM [107] | 2018 | MA | L | IMG, TAB, TXT, GRH, TS, VID | C | N, T | |

| Guided Proto [108] | 2019 | MA | L | IMG, TAB | C | V, T | |

| DICE [109] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| ACE [110] | 2019 | MA | G | IMG | C | N, T | |

| ConceptSHAP [111] | 2020 | MA | G | IMG | C | N, V | |

| Soft DT [112] | 2017 | MS | Decision Tree | G | IMG | C | RU |

| ALE [25] | 2016 | MA | G | TAB | C, R | V | |

| CIU [113] | 1995 | MA | L, G | IMG, TAB | C, R | N | |

| Regularisation [114] | 2015 | MS | L | IMG | C | N | |

| GFA [115] | 2016 | MA | G | TAB | C, R | N, V | |

| GAN Dissection [116] | 2018 | MS | GAN | L | IMG | C | V |

| FACE [117] | 2019 | MA | L | IMG, TAB, TXT, GRH, TS, VID | C | N, T | |

| NAM [118] | 2020 | MS | L | TAB | C, R | V | |

| RuleMatrix [119] | 2018 | MA | G | TAB | C | RU, V | |

| Grad-CAM++ [120] | 2018 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| L2X [121] | 2018 | MA | L | IMG, TXT | C | N | |

| MAPLE [122] | 2018 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | N, RU | |

| PIMP [123] | 2010 | MA | G | TAB | C | N | |

| BreakDown [124] | 2018 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | N, T | |

| ABELE [125] | 2020 | MA | L | IMG | C | N, T | |

| MOC [126] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | N, T | |

| SEDC [127] | 2014 | MA | L | TXT | C | V, RU | |

| LIVE [124] | 2018 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | V | |

| GraphLIME [128] | 2020 | MA | L | GRH | C | N, V | |

| GLocalX [129] | 2020 | MA | L, G | TAB | C | RU | |

| Privacy-Preserving Explanations [130] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N | |

| PI, ICI [131] | 2018 | MA | G | TAB | C, R | N | |

| QII [132] | 2016 | MA | G | TAB | C | N | |

| FOCUS [133] | 2021 | MA | G | TAB | C, R | N | |

| EBCF [134] | 2020 | MS | Recommender Systems | L | TAB | C | V, T |

| DCE [135] | 2019 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| Actionable Recourse [136] | 2019 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| DACE [137] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| MACE [138] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | N, T | |

| C-CHVAE [139] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| SYNTH [140] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | V | |

| DECE [141] | 2020 | MA | L, G | TAB | C | N, T | |

| ALG-REC [142] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| Growing Spheres [143] | 2017 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| CERTIFAI [144] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB, IMG, TXT | C, R | N | |

| ViCE [145] | 2020 | MA | L | TXT | C | V, T | |

| MC-BRP [146] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | RU | |

| LIME-C/SHAP-C [147] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, V | |

| CLEAR [148] | 2019 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | T, RU | |

| GNNExplainer [149] | 2019 | MA | L | GRH | C | N, V | |

| Shapley Flow [150] | 2020 | MA | L, G | TAB | C, R | N, V | |

| FBT [151] | 2020 | MS | DT Ensambles | G | TAB | C | N |

| CHIRPS [152] | 2020 | MS | Random Forest | L | TAB | C | N, V |

| LoRMIka [153] | 2019 | MA | L | TAB | C | RU, V | |

| Color-based monogram [154] | 2016 | MA | G | TAB | C | V | |

| SR map [155] | 2019 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | RU, V |

| DLIME [156] | 2019 | MA | L | IMG, TAB, TXT, GRH, TS, VID | C, R | N | |

| LioNets [157] | 2019 | MS | Intrinsically Interpretable DNN | L | TXT | C | RU |

| SkopeR | 2020 | MA | L, G | TAB | C | RU | |

| XRAI [158] | 2019 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| XSPELLS [159] | 2020 | MA | L | TXT | C | RU | |

| exBERT [160] | 2019 | MS | Transformer model | L | TXT | C | V |

| Slot Activation Vectors [161] | 2018 | MS | Slot Attention Model | L | TXT | C | N |

| Peak Response [162] | 2018 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| Autofocus-Layer [163] | 2018 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | N |

| NNKX [164] | 2017 | MS | DNN | G | TAB | C | N, V |

| Hypothesis Testing [165] | 2019 | MA | L | IMG, TXT | C | N | |

| GAM [166] | 2019 | MA | G | IMG, TAB | C | V | |

| Important Neurons and Patches [167] | 2017 | MS | CNN | G | IMG | C | N, V |

| InterpNET [168] | 2017 | MA | L | IMG | C | V | |

| ACE [169] | 2019 | MS | DNN | G | IMG, TAB, TXT, GRH, TS, VID | C | N, T |

| DoctorXAI [170] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| ORDCE [171] | 2021 | MA | L | TAB | C | N, T | |

| PIECE [172] | 2021 | MS | CNN | L | IMG | C | V |

| POLYJUICE [173] | 2021 | MA | L | TXT | C, R | T | |

| GeCO [174] | 2021 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | N, T | |

| RF-OCSE [175] | 2020 | MA | L | TAB | C, R | RU | |

| What-If [176] | 2020 | MA | G | TAB, IMG, TXT | C, R | V, N | |