Bifunctionalized Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization for Removal of Diclofenac from Aqueous Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

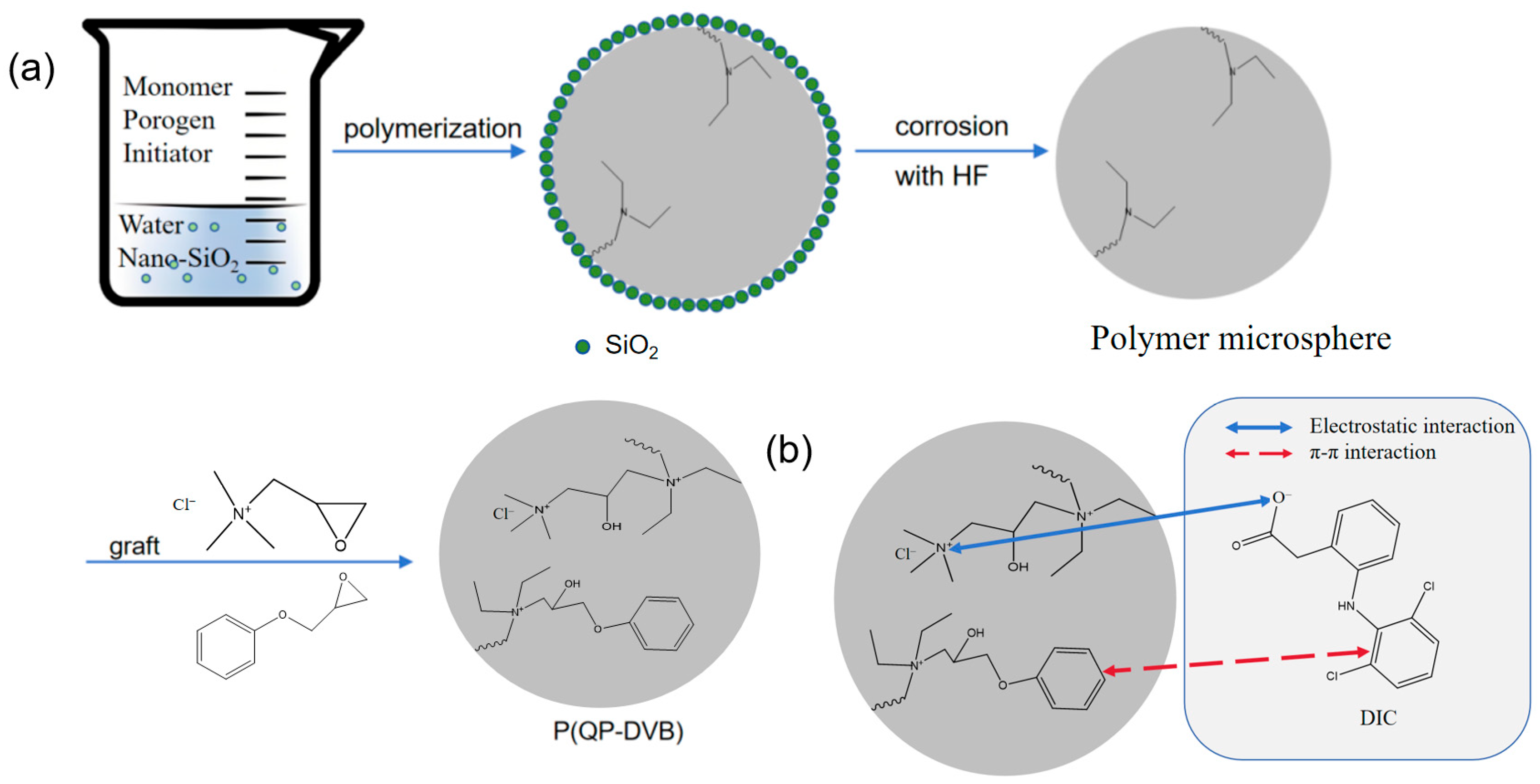

2.2. Synthesis of P(QP-DVB) Microspheres

2.3. Characterizations and Instruments

2.4. Batch Adsorption Experiments

2.5. Regeneration and Recycling Studies

3. Results and Discussion

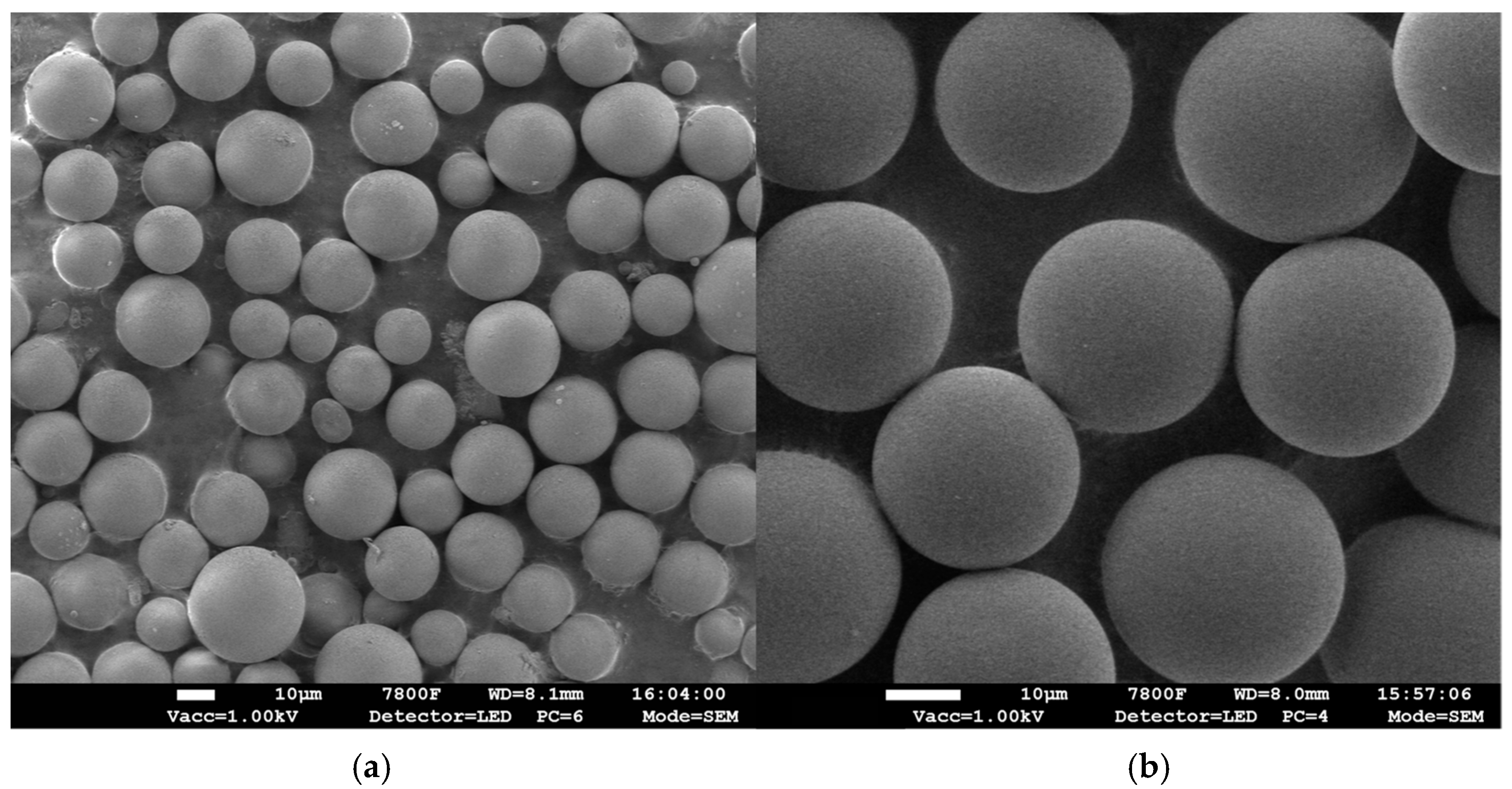

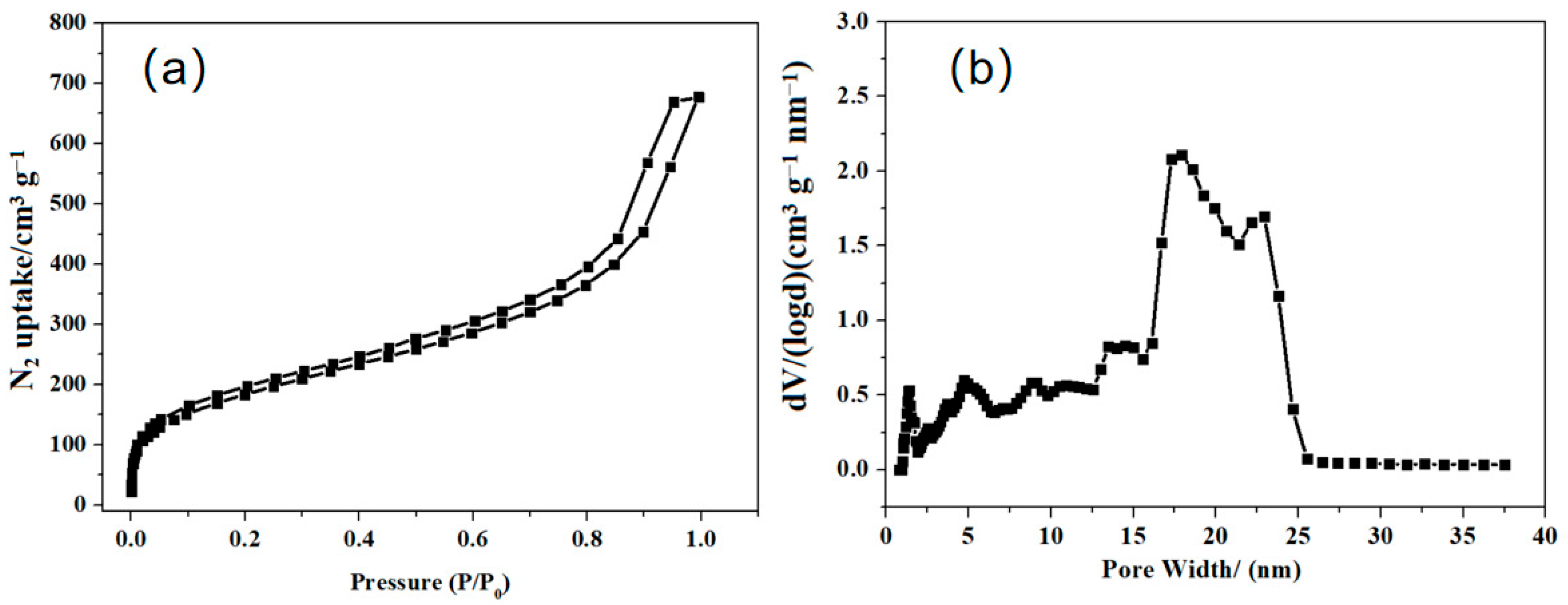

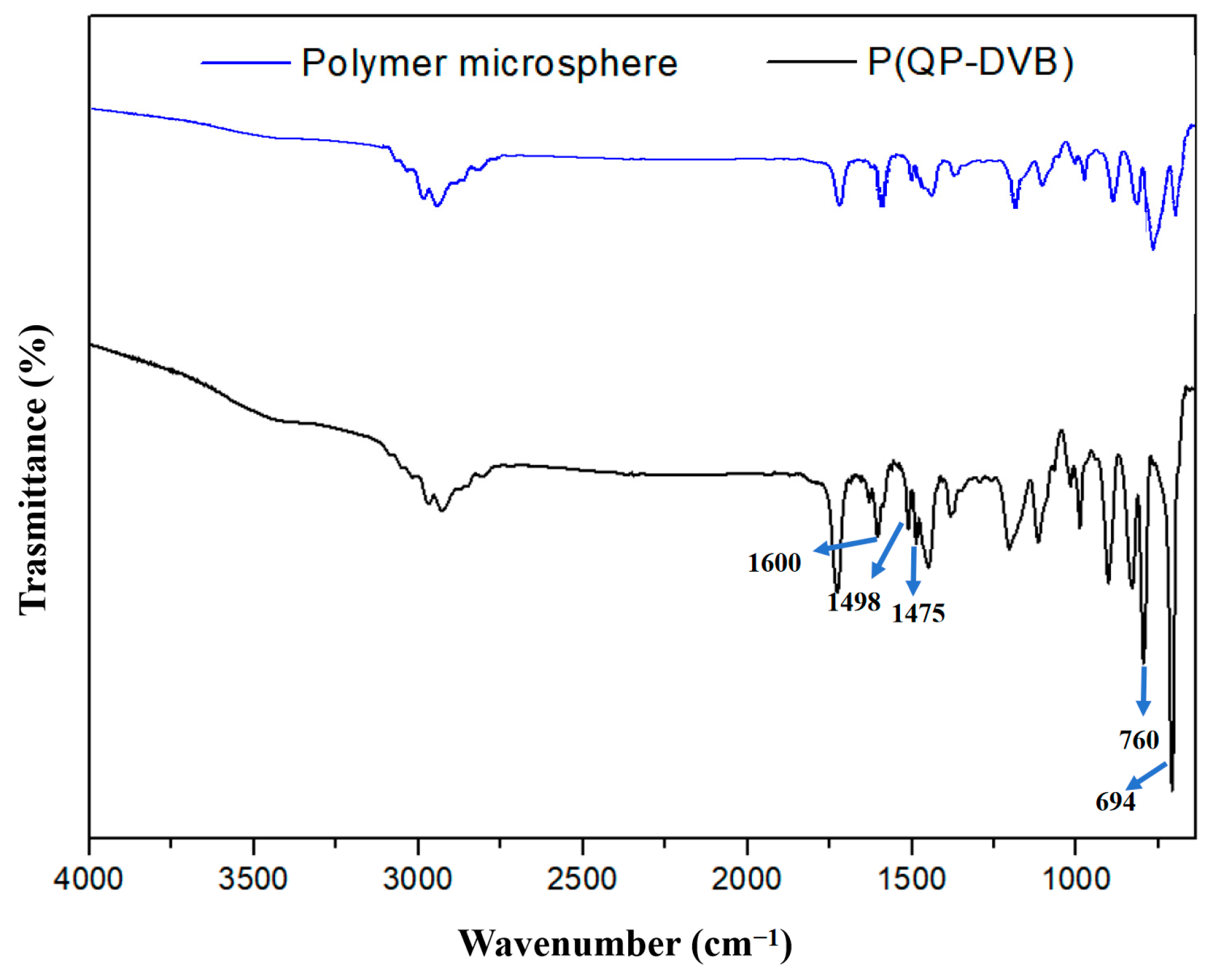

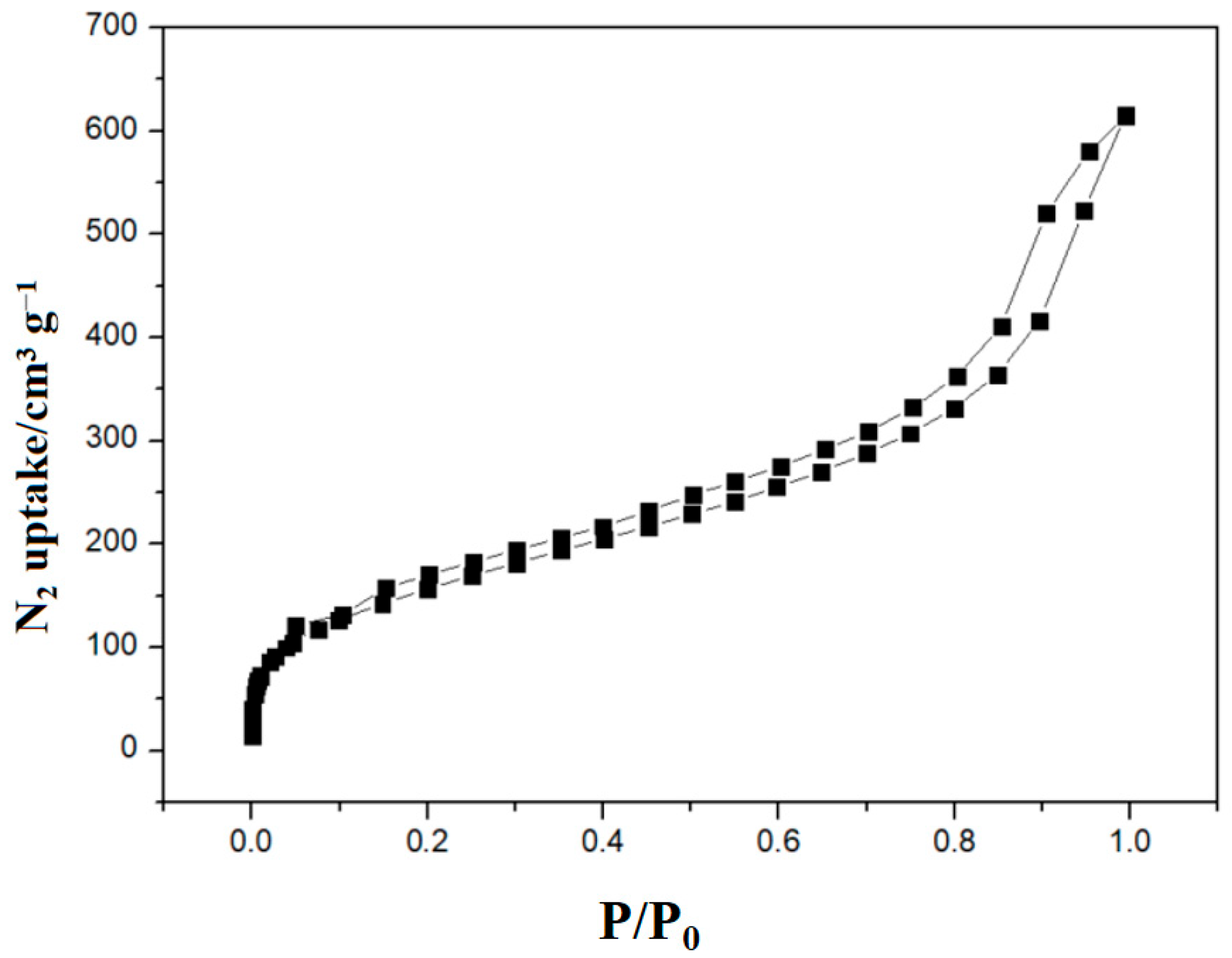

3.1. Characterizations of P(QP-DVB)

3.2. Adsorption Properties of P(QP-DVB) for DIC

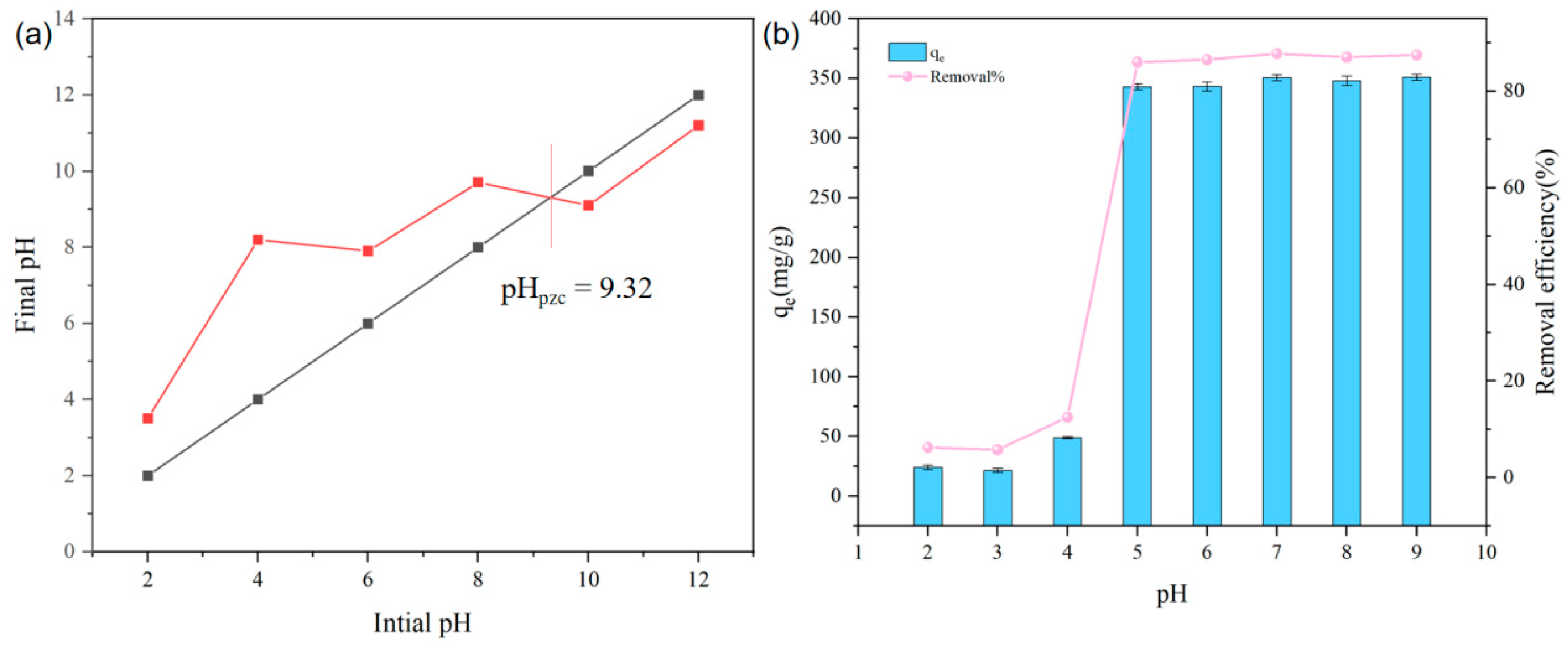

3.2.1. Effect of Solution pH

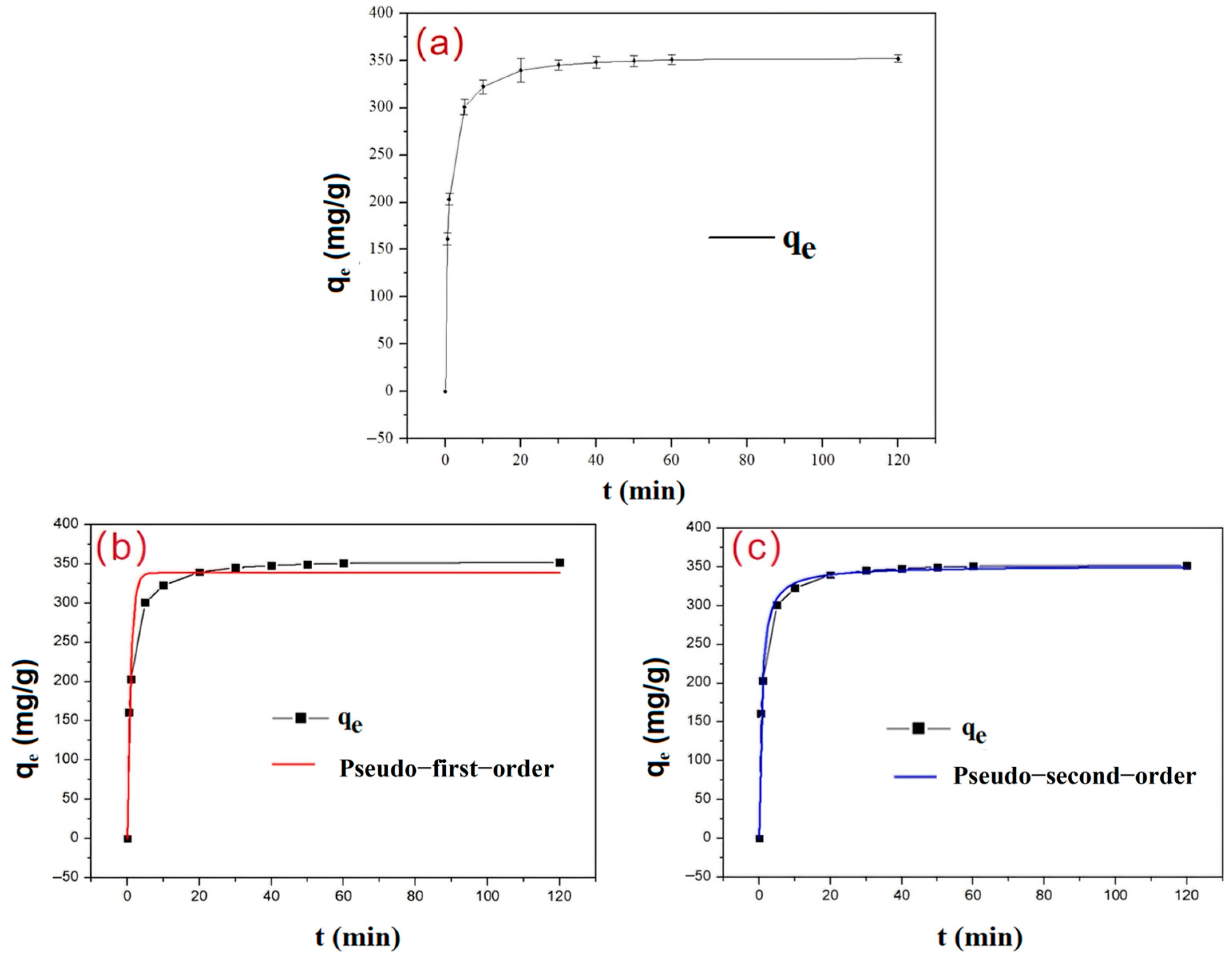

3.2.2. Adsorption Kinetic Study

3.2.3. Adsorption Isotherm Study

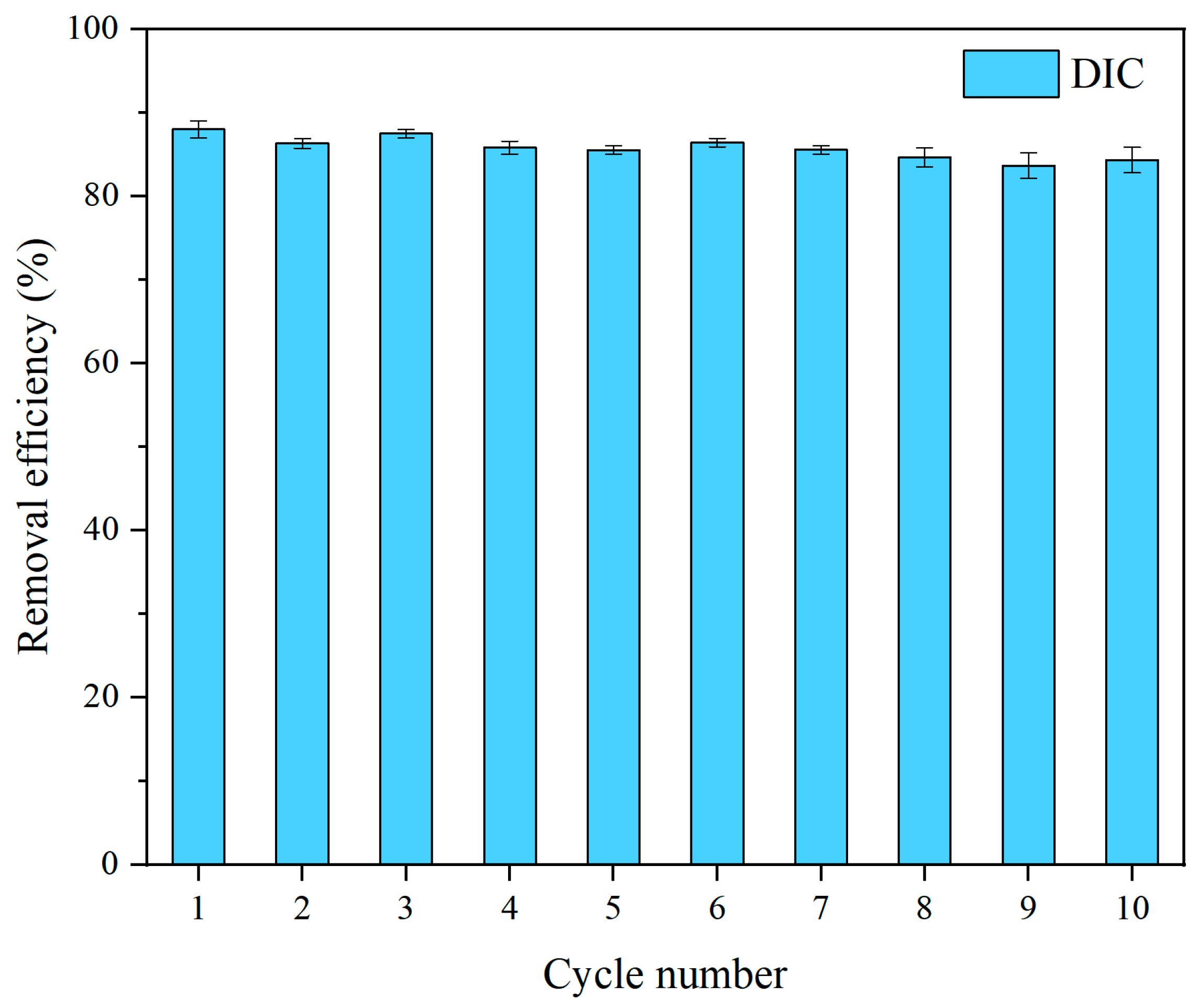

3.3. Regeneration and Reusability

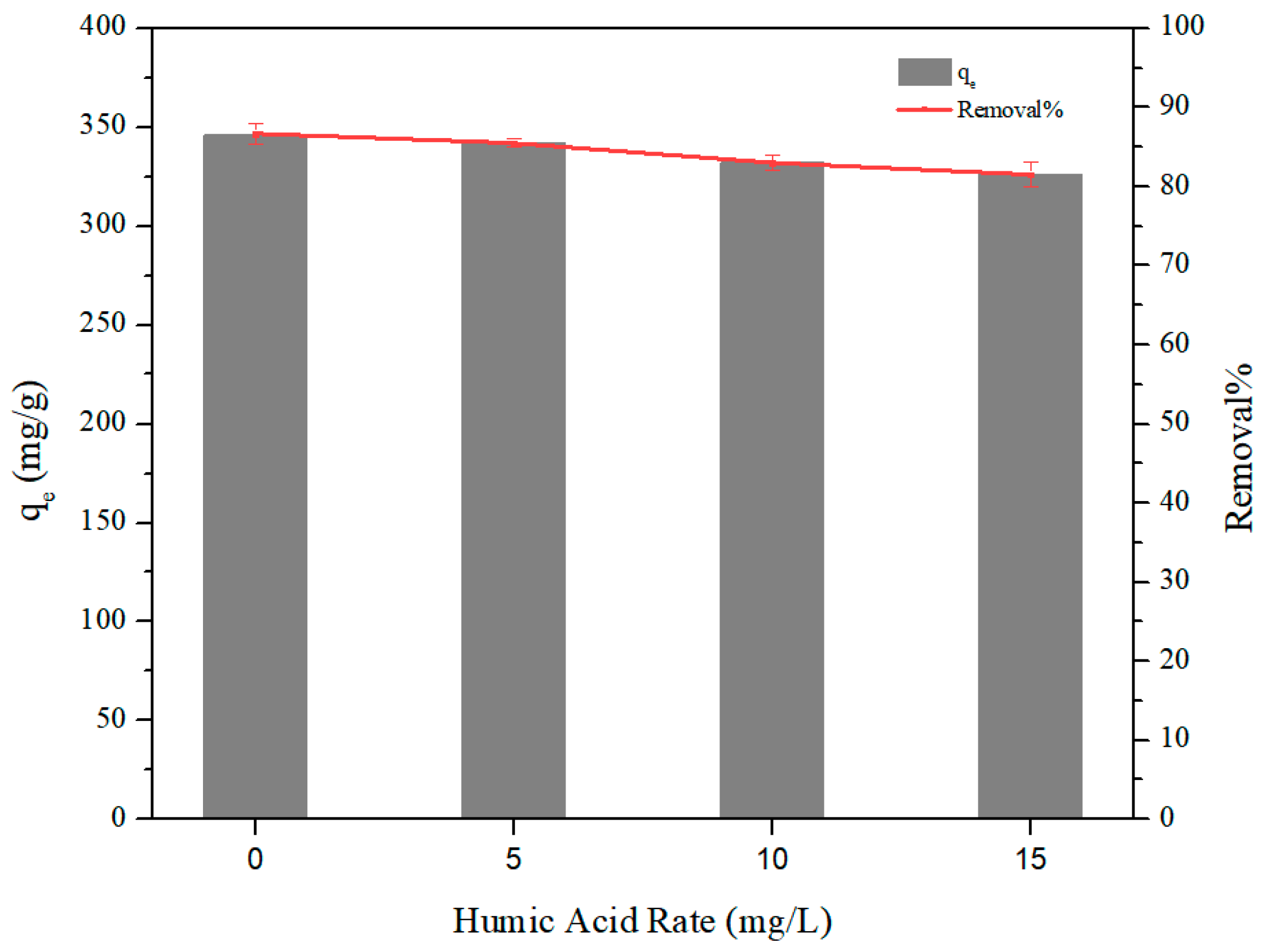

3.4. Adsorption Selectivity

3.5. Comparison with Other Sorbents

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohd Hanafiah, Z.; Wan Mohtar, W.H.M.; Abd Manan, T.S.B.; Bachi’, N.A.; Abdullah, N.A.; Abd Hamid, H.H.; Beddu, S.; Mohd Kamal, N.L.; Ahmad, A.; Wan Rasdi, N. The Occurrence of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) in Malaysian Urban Domestic Wastewater. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Galletti, A.; Petrovic, M.; Barceló, D. Hospital Effluent: Investigation of the Concentrations and Distribution of Pharmaceuticals and Environmental Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 430, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosma, C.I.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Albanis, T.A. Occurrence and Removal of PPCPs in Municipal and Hospital Wastewaters in Greece. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, C.; Faragó, N.; Faludi, T.; Kovács, Z.; Kobak, J.; Serfőző, Z. Organic Pollutants in a Large Shallow Lake, and the Potential of the Local Quagga Mussel Population for Their Removal. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 296, 118201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzhelele, E.P.; Mudzielwana, R.; Ayinde, W.B.; Gitari, W.M. Pharmaceutical Contaminants in Wastewater and Receiving Water Bodies of South Africa: A Review of Sources, Pathways, Occurrence, Effects, and Geographical Distribution. Water 2024, 16, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Flowers, R.C.; Weinberg, H.S.; Singer, P.C. Occurrence and Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in an Advanced Wastewater Reclamation Plant. Water Res. 2011, 45, 5218–5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Esposito, G.; Oturan, M.A. Removal of Residual Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Pharmaceuticals from Aqueous Systems by Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes. A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 944–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.A.; Lester, J.N.; Voulvoulis, N. Pharmaceuticals: A Threat to Drinking Water? Trends Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebskorn, R.; Casper, H.; Heyd, A.; Eikemper, R.; Köhler, H.-R.; Schwaiger, J. Toxic Effects of the Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Diclofenac. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004, 68, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, V.; Ginebreda, A.; Mor, J.R.; Petrovic, M.; Sabater, S.; Sumpter, J.; Barceló, D. Balancing the Health Benefits and Environmental Risks of Pharmaceuticals: Diclofenac as an Example. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ying, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.-F.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, X. Determination of Phenolic Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Acidic Pharmaceuticals in Surface Water of the Pearl Rivers in South China by Gas Chromatography–Negative Chemical Ionization–Mass Spectrometry. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ying, G.; Zhao, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Tao, R.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L. Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Acidic Pharmaceuticals in the Yellow River, Hai River and Liao River of North China. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3139–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, B.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, L.; Huang, J.; Deng, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G. Characterization of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds in Dongting Lake, China: Occurrence, Chiral Profiling and Environmental Risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 557–558, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dihingia, H.; Pathak, S.; Lalmalsawmdawngliani; Lalhmunsiama; Tiwari, D.; Kim, D.-J. A Sustainable Solution for Diclofenac Degradation from Water by Heterojunction Bimetallic Nanocatalyst. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 166, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul Zaman, H.; Baloo, L.; Pendyala, R.; Singa, P.K.; Ilyas, S.U.; Kutty, S.R.M. Produced Water Treatment with Conventional Adsorbents and MOF as an Alternative: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yan, R.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Facile Fabrication of Hollow Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization Stabilized with TiO2 Nanoparticles. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; An, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, B. Controlled Preparation of Hollow N-Al/Fe2O3 MICs Microspheres by Two-Droplet Microfluidic Technique and Performance Study. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 29538–29547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Yu, S.; Liang, X.; Hong, Y.; Shi, W.; Jiang, C.; Wu, D. Xylan Nanocrystal-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion for Templating Polymer Microspheres with Tunable Structures. Polymer 2025, 335, 128824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, H.; Yang, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, A. A Novel Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by Rational Designed Agar Microsphere. LWT 2023, 181, 114751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jing, C.; Zhai, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.-G. MIL-101(Fe)/Polysulfone Hollow Microspheres from Pickering Emulsion Template for Effective Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 667, 131394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yun, J.; Song, J.; Sun, J.; Lan, Q. Pickering Emulsion Based on Chitosan with Uniform Droplet Size for High-Efficient and Stable Treatment of 4-Nitrophenol Wastewater. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 309, 121522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Feng, X.; Liu, S. Porous Imprinted Microspheres with Covalent Organic Framework-Based, Precisely Designed Sites for the Specific Adsorption of Flavonoids. Separations 2025, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Gou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Dendritic Bifunctional Nanotraps inside SBA-15 for Highly Efficient Removal of Selected Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs from Wastewater. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, e14347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Choi, D.; Kim, S.; Her, N.; Zoh, K. Adsorption Characteristics of Selected Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Micropollutants in Water Using Activated Carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 270, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjan, A.M.; Premakshi, H.G.; Kariduraganavar, M.Y. Synthesis and Characterization of GTMAC Grafted Chitosan Membranes for the Dehydration of Low Water Content Isopropanol by Pervaporation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 25, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lu, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, F.; Ouyang, X. Fabrication of Polyethylenimine-Functionalized Sodium Alginate/Cellulose Nanocrystal/Polyvinyl Alcohol Core–Shell Microspheres ((PVA/SA/CNC)@PEI) for Diclofenac Sodium Adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 554, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Gou, X.; Fan, Y.; Chen, J. Underwater Suspended Bifunctionalized Polyethyleneimine-Based Sponge for Selective Removal of Anionic Pollutants from Aqueous Solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, X.; Ji, C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, F.; Yang, L.-Y. Fabrication of Cross-Linked Chitosan Beads Grafted by Polyethylenimine for Efficient Adsorption of Diclofenac Sodium from Water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, S.; Ribeiro, R.S.; Gomes, H.T.; Sotelo, J.L.; García, J. Synthesis of Carbon Xerogels and Their Application in Adsorption Studies of Caffeine and Diclofenac as Emerging Contaminants. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 95, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.F.; Fernandes, T.; Sacramento, M.; Trindade, T.; Daniel-da-Silva, A.L. Magnetic Quaternary Chitosan Hybrid Nanoparticles for the Efficient Uptake of Diclofenac from Water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 203, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godiya, C.B.; Kumar, S.; Xiao, Y. Amine Functionalized Egg Albumin Hydrogel with Enhanced Adsorption Potential for Diclofenac Sodium in Water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccar, R.; Sarrà, M.; Bouzid, J.; Feki, M.; Blánquez, P. Removal of Pharmaceutical Compounds by Activated Carbon Prepared from Agricultural By-Product. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

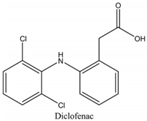

| pKa | CAS Number | Log P | Water Solubility (mg L−1) | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.15 | 15307-86-5 | 4.51 | 2.37 |  |

| SBET (m2 g−1) | Pore Volume (cm3 g−1) | Pore Size (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P(QP-DVB) | 637 | 1.1 | 2–25 |

| Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-First Order | Pseudo-Second Order | |||||

| qe,exp (mg/g) | qe (mg/g) | K1 (min−1) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg·min) | R2 |

| 352.0 | 328.0 | 0.12 | 0.974 | 351.2 | 0.0042 | 0.997 |

| Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir Isotherm | Freundlich Isotherm | ||||||

| qe,exp (mg/g) | qm (mg/g) | KL (L mg−1) | RL | R2 | Kf (L mg−1) | n | R2 |

| 415 | 487.56 | 0.055 | 0.045 | 0.996 | 52.70 | 0.53 | 0.981 |

| Adsorbent | C0 (mg/L) | T (K) | qmax (mg/g) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA/CNC/PVA@PEI composite | 100–1000 | 303 | 418.41 | [26] |

| SQP-PEI | 5–60 | 298 | 342.70 | [27] |

| EPCS@PEI adsorbent | 50–200 | 308 | 253.32 | [28] |

| Carbonxerogels | 0–60 | 298 | 182.50 | [29] |

| Fe3O4@SiO2/SiHTCC | 0–600 | 298 | 240.40 | [30] |

| ALB/PEI hydrogel | 100–300 | 298 | 232.5 | [31] |

| AC derived from agricultural by-product | 0–10 | 298 | 56.2 | [32] |

| P(QP-DVB) | 10–300 | 298 | 487.56 | Present work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gou, X.; Ahmad, Z.; You, Z.; Ren, Z. Bifunctionalized Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization for Removal of Diclofenac from Aqueous Solution. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120663

Gou X, Ahmad Z, You Z, Ren Z. Bifunctionalized Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization for Removal of Diclofenac from Aqueous Solution. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120663

Chicago/Turabian StyleGou, Xiaoyi, Zia Ahmad, Zaijin You, and Zhou Ren. 2025. "Bifunctionalized Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization for Removal of Diclofenac from Aqueous Solution" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120663

APA StyleGou, X., Ahmad, Z., You, Z., & Ren, Z. (2025). Bifunctionalized Microspheres via Pickering Emulsion Polymerization for Removal of Diclofenac from Aqueous Solution. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120663