1. Introduction

The construction industry is a cornerstone of modern society, responsible for shaping our built environment and supporting economic development [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, it also faces considerable challenges in reducing its environmental footprint and transitioning toward more sustainable practices [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Concrete production, in particular, relies heavily on natural aggregates (sand, gravel, crushed stone) whose extraction causes habitat destruction, landscape alteration, and depletion of finite resources [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. These materials are finite resources, and their extraction often results in habitat destruction, landscape alteration, and depletion of natural reserves [

16,

17]. Moreover, the processes involved in quarrying, processing, and transporting these aggregates consume substantial energy, generate significant carbon emissions, and contribute to pollution, further exacerbating the environmental costs associated with conventional concrete [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Globally, demand for sand and gravel has tripled in the last two decades, reaching an estimated 50 billion tonnes per year—a rate far exceeding natural replenishment and prompting warnings of an emerging “sand crisis”. Additionally, cement manufacturing (a key component of concrete) is a major CO

2 emitter, accounting for roughly 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

In response to these pressing issues, the industry, researchers, and policymakers are increasingly searching for innovative solutions to enhance the sustainability of construction materials while maintaining stringent performance standards [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. A promising strategy involves the utilization of industrial and mining waste materials as partial substitutes for traditional aggregates [

38,

39]. Such approaches offer multiple benefits: they help reduce reliance on natural resources, mitigate waste disposal problems, and promote a circular economy by converting waste into valuable materials for construction [

40]. This not only lessens environmental degradation but can also lead to economic savings and resource efficiency [

39,

41,

42].

Recent advances in sustainable concrete technologies underline the potential of incorporating supplementary cementitious materials like including fly ash, slag, marble powder, and quarry dust—can improve concrete’s mechanical properties and durability while addressing disposal issues [

43,

44,

45]. For example, Mostofinejad et al. [

46] explored the combined effects of these materials on high-strength concrete (HSC), revealing significant improvements in strength, carbonation resistance, and steel protection. Their work demonstrated that optimizing the composition of concrete mixes could substantially enhance performance while contributing to environmental goals. Substituting a portion of cement with ultrafine mineral admixtures has been shown to densify the microstructure and enhance strength. Umar et al. demonstrated that using locally available bentonite clay and quarry dust as supplementary cementitious materials led to a ~7% increase in compressive strength and ~20% increase in flexural strength of concrete, compared to a conventional mix [

26]. Such findings highlight that sustainable material innovations need not come at the expense of performance—on the contrary, judicious use of waste materials can confer beneficial filler effects and even pozzolanic reactions that improve concrete quality [

47].

Amid these developments, stone quarry sludge (SQS)—the fine-grained slurry waste from stone cutting and crushing operations—emerges as a noteworthy candidate for sustainable reuse [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Large quantities of this sludge are generated by the dimension stone industry (often 30–40% of the quarried stone ends up as waste fines), posing disposal and pollution challenges. If dumped in land or water bodies, SQS can cause soil contamination, clogging of waterways, and other environmental hazards. Valorizing SQS as a partial replacement for natural fine aggregate in concrete offers an attractive solution to this problem. Quarry sludge consists predominantly of inert mineral particles (e.g., stone dust rich in silica and calcium carbonate) with a particle size distribution generally finer than that of natural sand. These characteristics suggest that SQS could act as a micro-filler in the cementitious matrix, potentially enhancing particle packing and reducing voids. In fact, the chemical makeup of granite-based quarry dust has been found to meet standard requirements for pozzolanic materials [

50], indicating that stone sludge may impart not only physical filler effects but also mild cementitious behavior. By replacing a fraction of sand with SQS, there is potential to improve concrete density and strength while simultaneously diverting waste from landfills [

54,

55,

56].

Recent investigations confirm that although stone quarry sludge and related residues have been incorporated into various concrete formulations, the existing literature remains predominantly case-specific, lacking systematic classification, cross-study comparability, and quantitative synthesis. For example, Scioti et al. [

48] explored the reuse of stone waste sludge in building blocks, emphasizing environmental benefits but omitting comparative mechanical benchmarks across different replacement levels or concrete grades. In another study, Kabashi et al. [

57] examined stone dust as a partial substitute for fine aggregates and cement, focusing primarily on compressive strength without integrating microstructural or environmental performance indicators.

In contrast, the present study offers a more comprehensive contribution by:

Systematically varying SQS replacement levels from 10% to 50% to identify the optimal dosage for HSC.

Integrating mechanical, microstructural (FTIR), and environmental (carbon footprint) assessments within a unified experimental framework.

Quantifying performance gains and sustainability trade-offs, which are seldom addressed concurrently in prior research. This multi-dimensional approach addresses a critical gap in the literature by providing a holistic evaluation of SQS in HSC applications—an area that remains relatively underexplored despite its sustainability potential.

A thorough review of current studies reveals that most research has focused on incorporating stone dust or sludge into conventional or normal-strength concrete, which typically exhibits lower structural demands. Only a limited number of investigations have specifically targeted HSC, defined by compressive strengths exceeding 50 MPa. Quantitatively, prior studies have generally explored replacement levels between 10% and 25%, often reporting modest improvements in mechanical properties. For example, Silva et al. [

55] found that substituting natural sand with stone dust at approximately 25% increased 28-day compressive strength by around 7%. Some studies have also reported comparable or superior tensile and flexural strengths relative to control mixes.

However, the literature lacks a comprehensive meta-analysis or standardized dataset that defines optimal replacement thresholds for HSC, particularly considering its unique microstructural and durability requirements. Moreover, limited insight exists regarding the influence of SQS on durability-related parameters such as permeability, microstructural integrity, and long-term performance under aggressive environmental conditions.

Silva et al. [

55] further noted that replacement levels exceeding 30% tend to impair mechanical performance, primarily due to increased water demand, reduced workability, and disruption of the aggregate skeleton—factors that contribute to weaker internal bonding and potential microcrack formation. These observations suggest a narrow window for optimal SQS incorporation, where benefits are maximized without compromising structural integrity or durability.

Despite these findings, existing research remains fragmented, often constrained by localized material sources, specific slurry characteristics, and limited experimental scopes. This variability hinders the development of generalizable conclusions and industrial-scale implementation guidelines.

Recognizing these limitations, the present study systematically expands upon previous work by investigating a broader range of SQS replacement levels—up to 50% by weight of sand. The primary objective is to determine the optimal dosage that enhances HSC performance, particularly in terms of compressive strength, flexural strength, and modulus of elasticity—key parameters for structural applications. To this end, a rigorous experimental protocol is employed, encompassing both fresh and hardened concrete properties, as well as microstructural evolution via FTIR analysis.

By establishing detailed, quantitative relationships between SQS content and performance metrics, this research aims to deliver a statistically robust and environmentally informed understanding of SQS as a sustainable material for high-performance concrete. Ultimately, the findings are expected to inform evidence-based guidelines for optimal application rates and support the advancement of eco-efficient construction practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The main materials utilized in this study include Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), natural fine aggregate (sand), coarse aggregate, and SQS, which functions as a partial replacement for fine aggregate. The OPC employed conforms to the relevant industry standards, ensuring consistent quality. The natural sand and coarse aggregates were sourced from local suppliers, selected based on their compliance with ASTM standards for grading and cleanliness.

The quarry sludge was procured from nearby stone processing plants, where it is generated as a byproduct during the cutting and polishing of stone blocks.

It is important to note that SQS is commonly classified as an inert mineral residue predominantly composed of siliceous and calcareous constituents, similar to conventional aggregates and fillers. As such, in many jurisdictions (e.g., under European Waste Codes), it does not trigger immediate concerns regarding hazardous leachates unless contaminated by external industrial agents. Since the SQS used in this study was sourced from a controlled quarry environment without known contamination, the likelihood of hazardous leaching was considered minimal.

As the percentage of SQS replacement increased, the mix exhibited higher water demand due to the increased surface area and fineness of the sludge particles. To maintain uniform workability, the dosage of polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer was systematically adjusted for each mix. The optimization was carried out iteratively during trial batching, targeting a slump consistency of approximately 20 cm for all mixtures to comply with the workability requirements of HSC applications.

Slump testing was conducted for every mix to validate these adjustments, and the final superplasticizer dosages were recorded accordingly. This approach ensured comparability between the mixes and eliminated variability in fresh-state properties that could otherwise skew the mechanical and durability assessments. Chemical specifications of quarry sludge are listed in

Table 1.

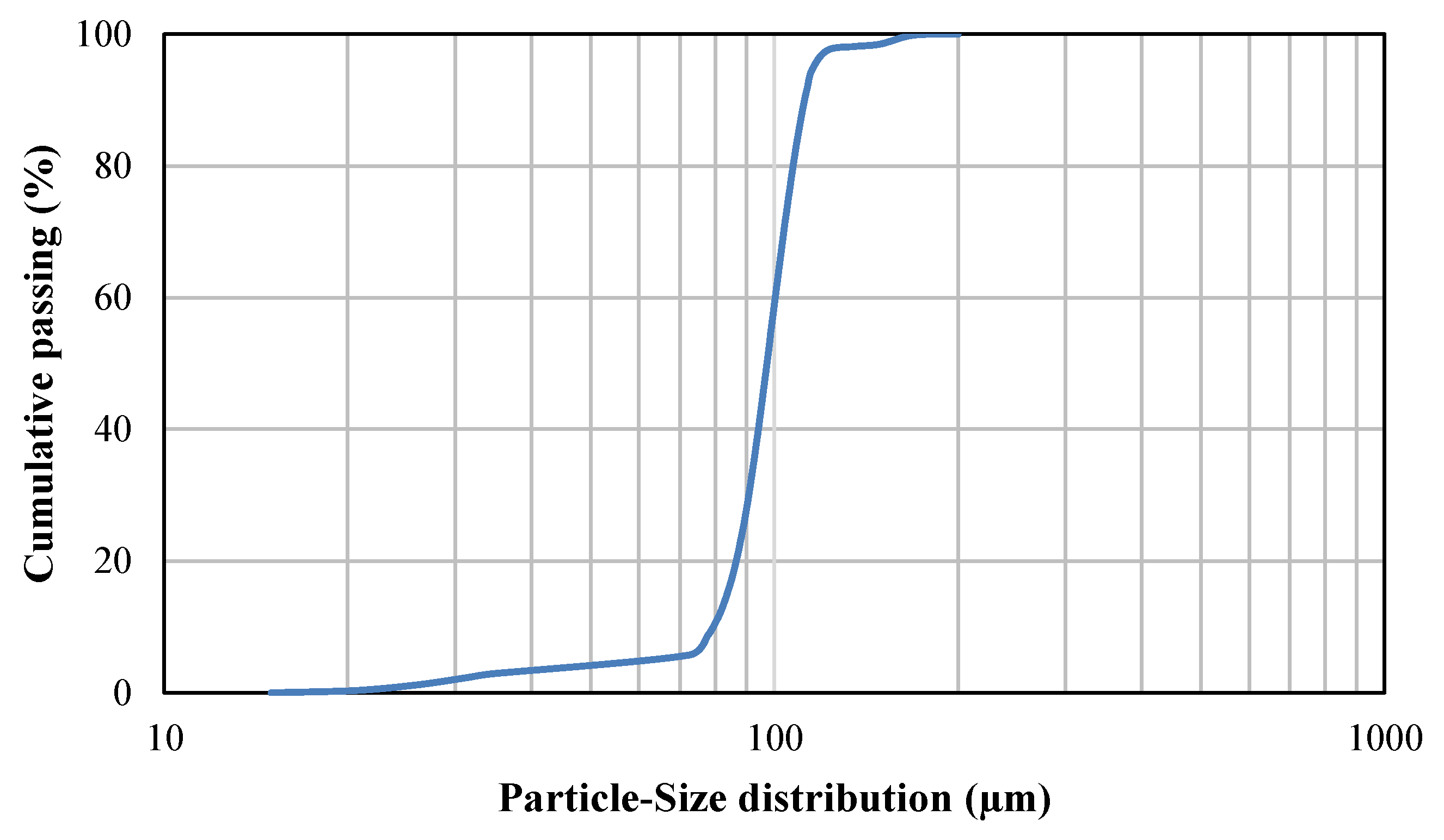

To provide experimental evidence of the fineness of the quarry sludge mentioned above,

Figure 1 shows the particle-size distribution of SQS used in this study. The particle size distribution analysis showed that the D50 and D90 values are 97 μm and 112 μm, respectively.

2.2. Mix Design

To systematically investigate the impact of quarry sludge on concrete properties, five different mix proportions were devised by substituting fine sand with quarry sludge at levels of 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% by weight (

Table 2). A control mix, without any sludge replacement, was also prepared to serve as a baseline for comparison. The mix proportions were calculated following standard methods, ensuring an optimal balance between workability, density, and strength.

In each mix, the water-cement ratio was carefully maintained constant to isolate the effects of sludge substitution. Superplasticizers were added as needed to achieve desired workability, particularly at higher sludge contents where increased surface area could affect rheology. All materials were batched and mixed following consistent procedures to produce uniform concrete specimens suitable for testing.

2.3. Experimental Procedures

For each mix proportion, three specimens were prepared and tested for every experimental measurement to evaluate the physical and mechanical properties of the modified concrete mixes:

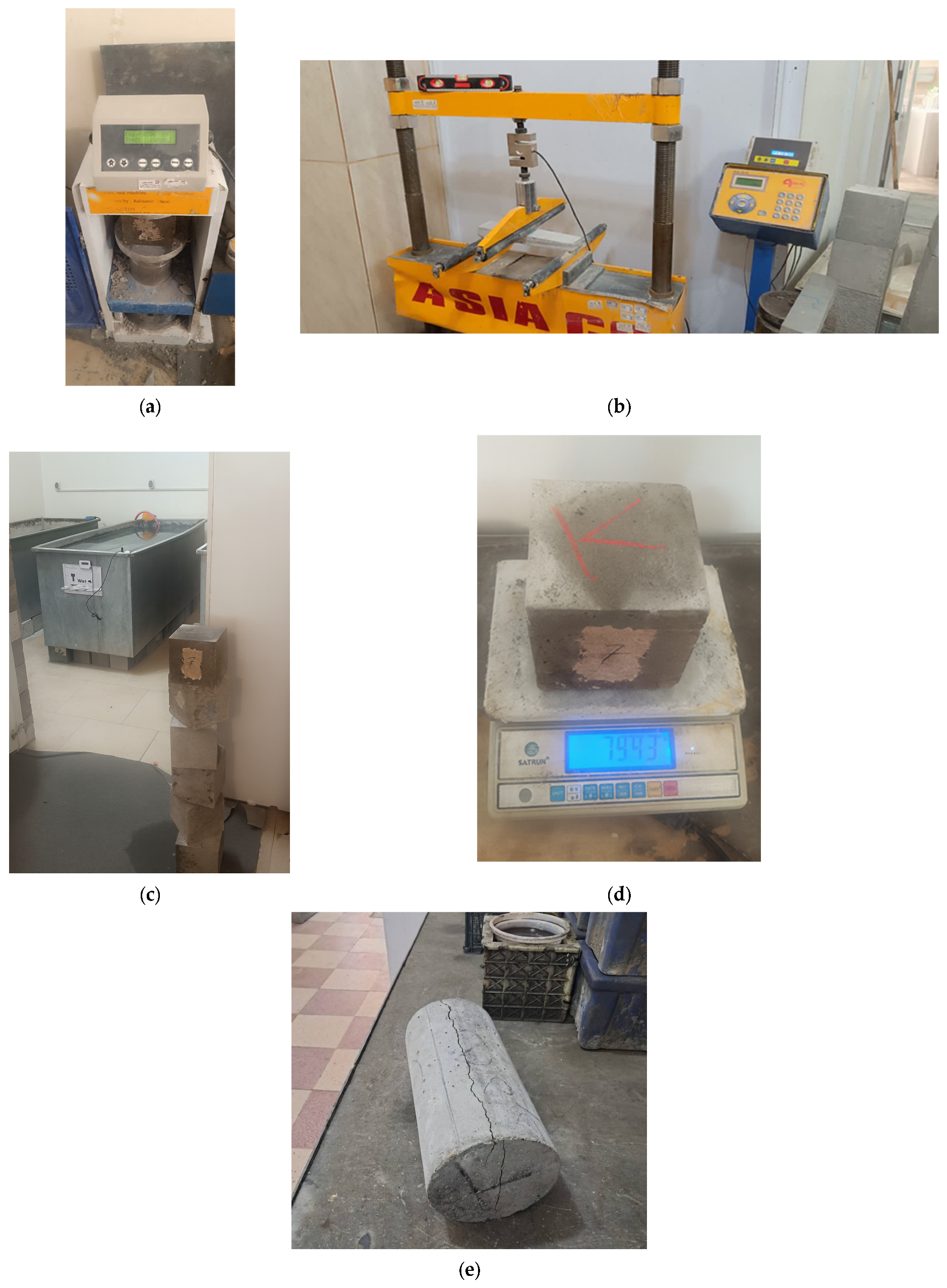

Compressive Strength Test: Cubic specimens (typically 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm) were cast and cured under controlled conditions (temperature and humidity). After 28 days of curing, compressive strength was measured using a universal testing machine in accordance with ASTM C39-12 [

58] (

Figure 2a).

Bending (Flexural) Strength Test: Beam specimens (typically 100 mm × 100 mm × 350 mm) were prepared and cured under identical conditions. Flexural strength was evaluated using a three-point bending setup in accordance with ASTM C78 [

59], employing a span length of 300 mm and a loading nose/support width of 25 mm. This configuration satisfies the standard’s span-to-depth ratio requirement of 3.0 for beams with a 100 mm depth (

Figure 2b).

Specific Weight Measurement: The density of each concrete mixture was determined by measuring the weight of a specimen of known volume immediately after mixing, providing insights into how sludge inclusion affects the overall mass per unit volume according to the ASTM C642 [

60] (

Figure 2d).

Brazilian Tensile Strength: Concrete cylindrical samples are placed horizontally in a compression testing machine based on ASTM C496 [

61]. A load is applied along their diameter until failure. The tensile strength is calculated from the failure load using the formula:

where P is the failure load, D is the diameter, and L is the length of the specimen.

Water Absorption Percentage: Concrete samples are dried at 105 °C until constant weight (dry weight) is achieved and then weighed. They are submerged in water for 24 h, surface-dried, and weighed again (saturated weight). The percentage of water absorption is calculated as:

where W

s is the saturated weight and W

d is the dry weight.

All specimens were cured in water or a controlled curing environment to ensure optimal hydration. Testing was performed under standardized conditions to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of results.

In this study, all concrete specimens underwent a standard water curing regimen over a period of 28 days to ensure adequate hydration and strength development. Initially, the fresh concrete samples were cast into molds and allowed to set undisturbed for 24 h at ambient laboratory conditions. Following this initial curing phase, the specimens were carefully demolded to avoid surface damage and were then fully submerged in clean water maintained at room temperature. This immersion process was conducted in accordance with widely accepted curing protocols to promote uniform moisture retention and optimize the microstructural development of the cementitious matrix over the curing duration.

Figure 2e shows the sample after experiment.

Figure 2.

Test setup; (a) Compressive strength; (b) Flexural strength; (c) Curing environment; (d) Density; (e) Brazilian Tensile Strength.

Figure 2.

Test setup; (a) Compressive strength; (b) Flexural strength; (c) Curing environment; (d) Density; (e) Brazilian Tensile Strength.

2.4. Carbon Footprint Assessment

To complement the mechanical and durability analyses, a cradle-to-gate carbon footprint (CF) assessment was conducted to quantify the environmental impact of incorporating SQS into HSC. The analysis followed ISO 14040:2006/ISO 14044:2006 standards [

62,

63] and was performed using the IMPACT 2002+ life-cycle impact assessment method.

The system boundary encompassed all processes from raw-material extraction to concrete production at the batching plant, excluding transportation of finished products and end-of-life stages. Inventory data for cement, aggregates, water, and admixtures were collected and estimated based on values reported in previously published life-cycle assessment studies of concrete materials [

16]. For the SQS, zero-burden allocation was adopted, assuming it is a waste by-product of quarrying operations requiring only drying and sieving prior to reuse.

The CF was quantified following the principles of ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, using a cradle-to-gate approach that encompasses all stages from raw material extraction to concrete production at the batching plant. The functional unit was defined as 1 m3 of concrete produced. The inventory data for cement, aggregates, water, and admixtures were based on literature sources and standard databases (e.g., Ecoinvent v3.8) reflecting average production conditions.

For each mix, the total CO

2-equivalent emissions were calculated as the sum of material-specific emission factors multiplied by their respective mass contributions according to Equation (1):

where

Ei represents the embodied emission factor of component

i (kg CO

2-eq/kg) and

Mi is the mass of that component (kg) per cubic meter of concrete.

3. Results

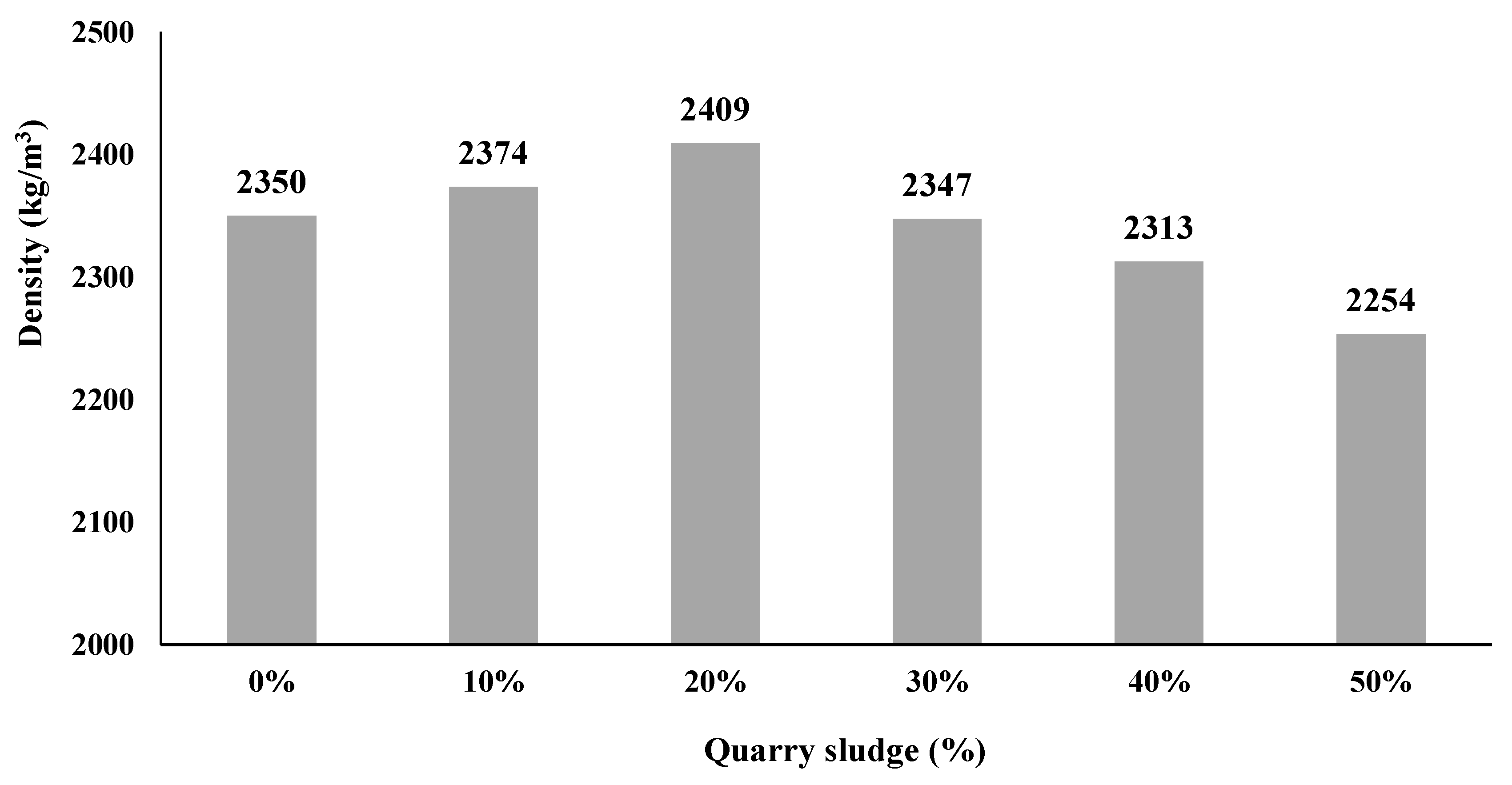

3.1. Density

The specific weight (or density) of the various concrete mix designs incorporating different proportions of SQS is illustrated in

Figure 3. This data reveals a clear trend in how the inclusion of quarry sludge influences the density of the concrete as the replacement percentage varies.

At lower levels of substitution, specifically up to 20%, the specific weight of the concrete demonstrated a gradual increase. This indicates that the addition of quarry sludge within this range contributed to a denser and more compacted matrix. The fine particle nature of the sludge likely enhanced packing efficiency within the mix, filling voids more effectively and reducing overall porosity. As a result, the concrete achieved its highest observed specific weight of approximately 2409 kg/m3 at the 20% replacement level, suggesting an optimal balance where the material composition promotes maximum density without compromising workability or structural performance.

Beyond the 20% replacement threshold, however, the trend reversed. Higher proportions of quarry sludge—namely 30%, 40%, and 50%—led to a steady decrease in the specific weight of the concrete. This decline suggests that excessive sludge integration may have negatively impacted the density, possibly due to the formation of microscopic voids or the disruption of the cohesive bonding within the mix. The increased porosity and potential poor particle bonding introduced by higher sludge content can weaken the overall structure, resulting in a less dense and more porous material.

Several factors may explain this pattern. As sludge content increases beyond the optimal point, the distribution of sludge particles might become uneven, leading to segregation or agglomeration. Additionally, the chemical and physical interactions between the sludge and cementitious matrix may be less effective at higher concentrations, reducing the binding efficiency and creating voids or weak zones within the concrete. These effects collectively diminish the overall density and potentially compromise the material’s durability and mechanical integrity.

In conclusion, the results underscore the importance of identifying an optimal replacement level that maximizes benefits related to material density and sustainability without detrimentally affecting the concrete’s structural qualities. The 20% quarry sludge replacement stands out as the most advantageous, offering an improved density conducive to HSC while aligning with environmentally sustainable practices. These findings provide critical insights into the material behavior and practical limits of incorporating quarry sludge into concrete, supporting its viability as a resource-efficient, eco-friendly alternative in modern construction.

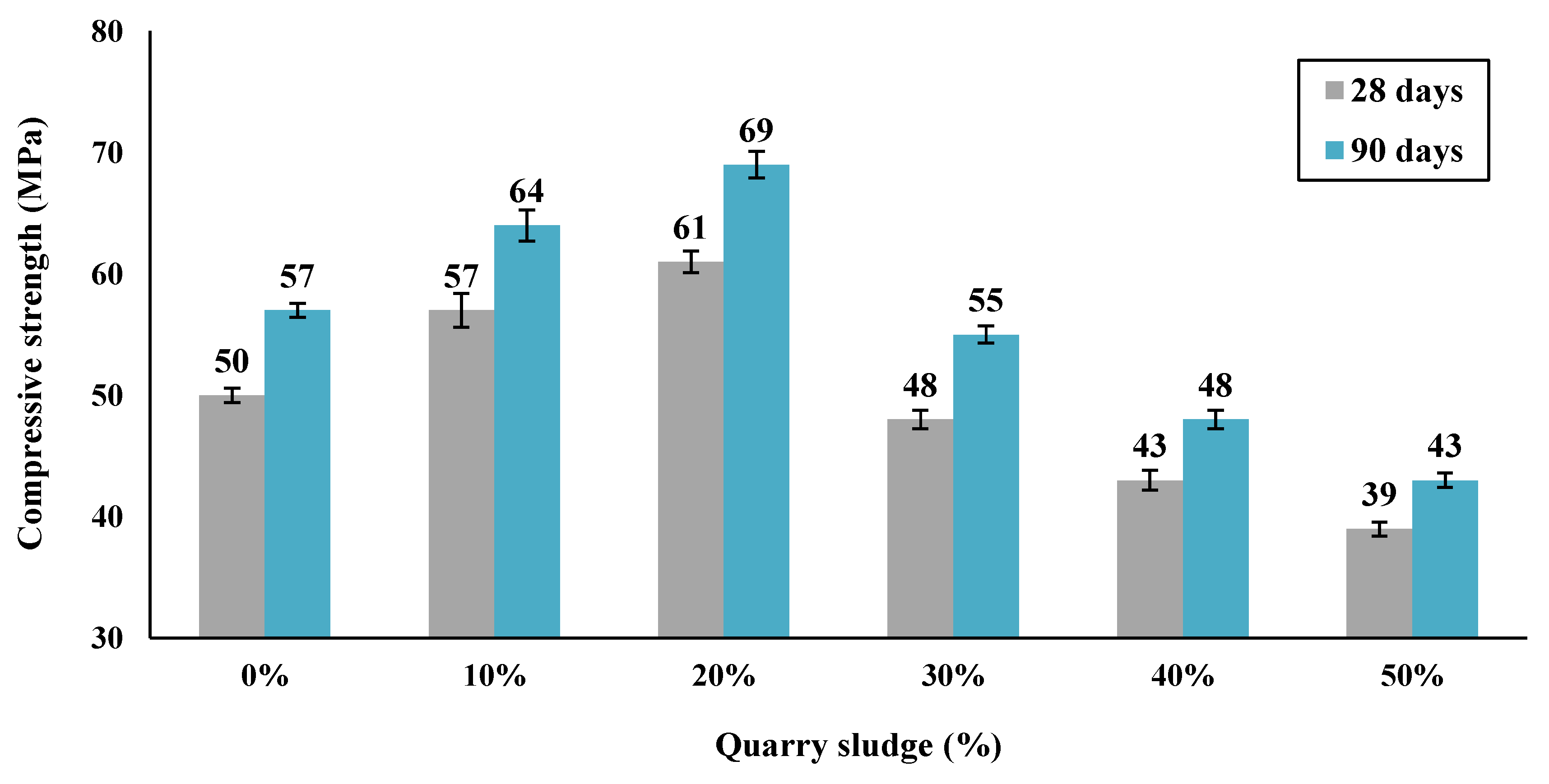

3.2. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength results of the various concrete mix designs incorporating different proportions of SQS as a partial replacement for fine sand are presented in

Figure 4. These data reveal a clear and noteworthy trend in how the percentage of quarry sludge affects the mechanical performance of HSC, particularly its load-bearing capacity.

In the early stages of sludge incorporation, up to a 20% replacement level, the compressive strength exhibited a steady and significant increase, culminating in a maximum value of 61 MPa. This improvement is primarily attributed to the physical characteristics of the quarry sludge. The finer particle size of the sludge compared to traditional sand contributes to a denser packing arrangement within the cementitious matrix, reducing voids and enhancing the interfacial transition zone between the cement paste and aggregates. This improved adhesion facilitates more efficient load transfer and resistance to compressive stresses.

At this optimal substitution level, the synergy between the sludge particles and the cement matrix appears to be most effective, suggesting that the sludge functions not only as a filler material but also potentially enhances the microstructure of the hardened concrete. However, this explanation remains at a macro level, relying on general physical observations. To gain deeper insight into the mechanisms driving strength development, further experimental investigations—such as microstructural analysis, hydration kinetics studies, and pore structure characterization—are recommended.

Beyond the 20% replacement threshold, compressive strength values showed a progressive decline as the sludge content increased to 30%, 40%, and 50%. This reduction likely results from disrupted aggregate interlocking, increased porosity, and potential interference with cement hydration due to excessive fine particles. These effects collectively compromise the density and cohesion of the hardened matrix, making it more susceptible to microcracking under load.

These findings underscore the importance of optimizing mix design to balance sustainability goals with structural performance requirements. The 20% replacement level emerges as the most promising composition, offering the highest compressive strength without compromising durability. Future research should focus on advanced characterization techniques to validate and expand upon these macro-level observations, enabling broader application of quarry sludge in sustainable concrete production.

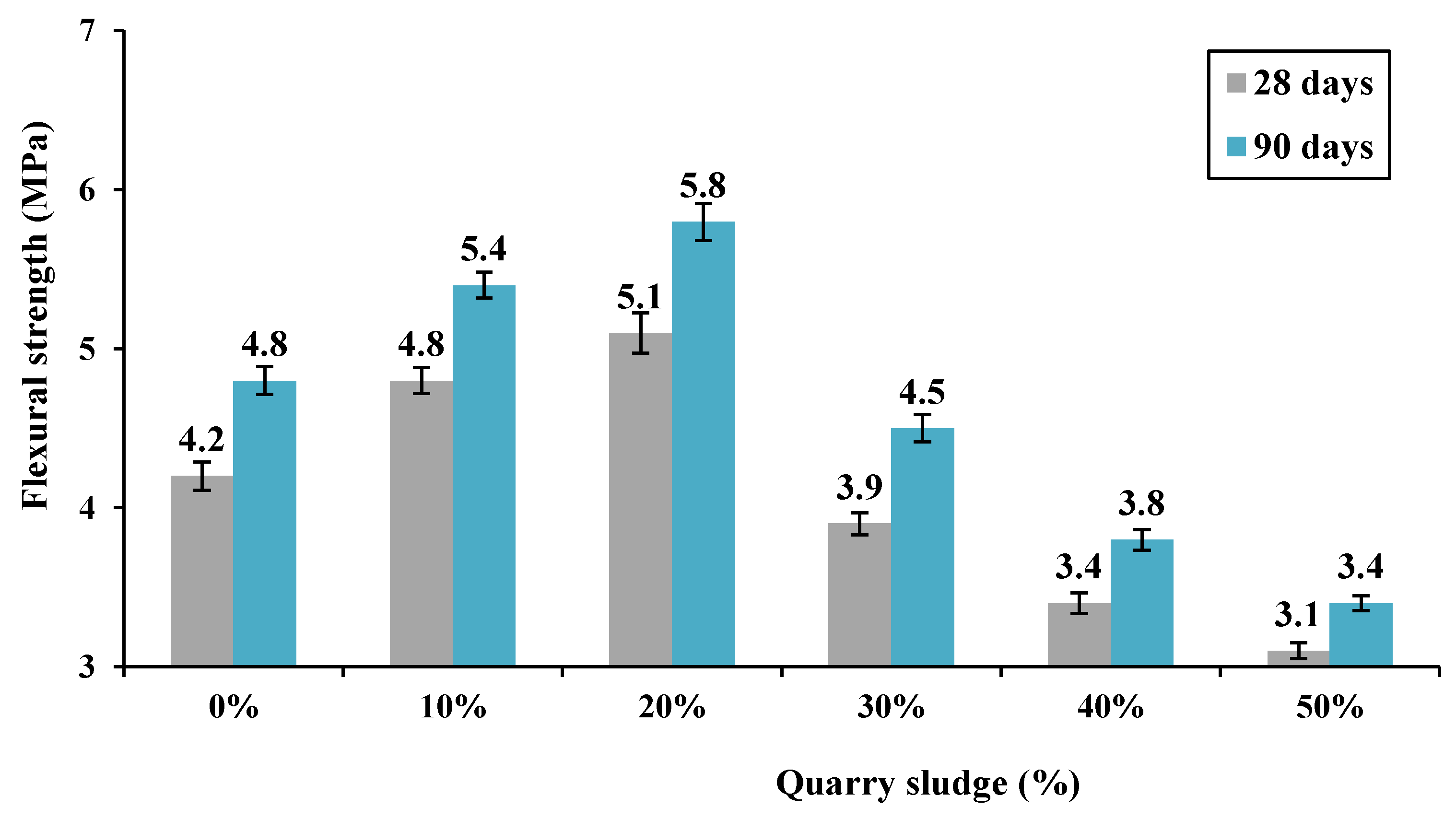

3.3. Flexural Strength

The flexural strength results of the various concrete mix designs incorporating different proportions of SQS as a partial replacement for sand are presented in

Figure 5. These data reveal a nuanced and systematic trend in the bending strength characteristics, providing critical insights into the mechanical performance and structural integrity of HSC modified with quarry sludge.

At lower replacement levels, particularly up to 20% sludge content, the flexural strength demonstrated a notable and consistent improvement, reaching a peak value of 5.1 MPa. This enhancement can be attributed to several sophisticated microstructural mechanisms. The fine-grained nature of quarry sludge particles enables more efficient packing within the cementitious matrix, creating a denser and more homogeneous microstructure. This improved particle arrangement facilitates enhanced interfacial transition zones between the cement paste and aggregate particles, promoting more effective stress transfer and load distribution.

The optimized particle packing at the 20% replacement level likely creates a more uniform stress distribution mechanism, allowing the concrete to resist bending forces more effectively. The sludge particles appear to act not merely as inert fillers but as active contributors to the concrete’s mechanical performance, potentially filling nano-scale voids and improving the overall cohesion of the material. This phenomenon suggests a synergistic interaction between the quarry sludge and the cement matrix that enhances the concrete’s flexural resistance.

Beyond the 20% replacement threshold, a clear and progressive decline in flexural strength was observed as sludge content increased to 30%, 40%, and 50%. This reduction can be attributed to multiple complex material science mechanisms. Excessive sludge incorporation disrupts the delicate balance of particle interactions within the concrete matrix, leading to several detrimental effects:

Increased Porosity: Higher sludge proportions create more void spaces, compromising the material’s structural continuity.

Reduced Aggregate Interlocking: Excessive fine particles impede the mechanical interlock between aggregates, weakening the overall load-transfer mechanism.

Altered Bonding Dynamics: The surplus sludge particles may interfere with proper cement hydration and bond formation, creating weaker interfacial zones.

These mechanisms collectively contribute to a progressive degradation of the concrete’s flexural performance, manifesting as reduced resistance to bending forces and increased susceptibility to microcracking.

The findings underscore the critical importance of precise mix design optimization in developing sustainable, high-performance concrete. The 20% quarry sludge replacement level emerges as the optimal composition, representing a strategic balance between environmental sustainability and mechanical performance. This replacement percentage maximizes the beneficial aspects of quarry sludge incorporation while mitigating potential structural compromises.

The results contribute significantly to the growing body of research on sustainable construction materials. By demonstrating the potential of industrial waste materials like quarry sludge to enhance concrete performance, the study provides a compelling argument for circular economy principles in the construction industry.

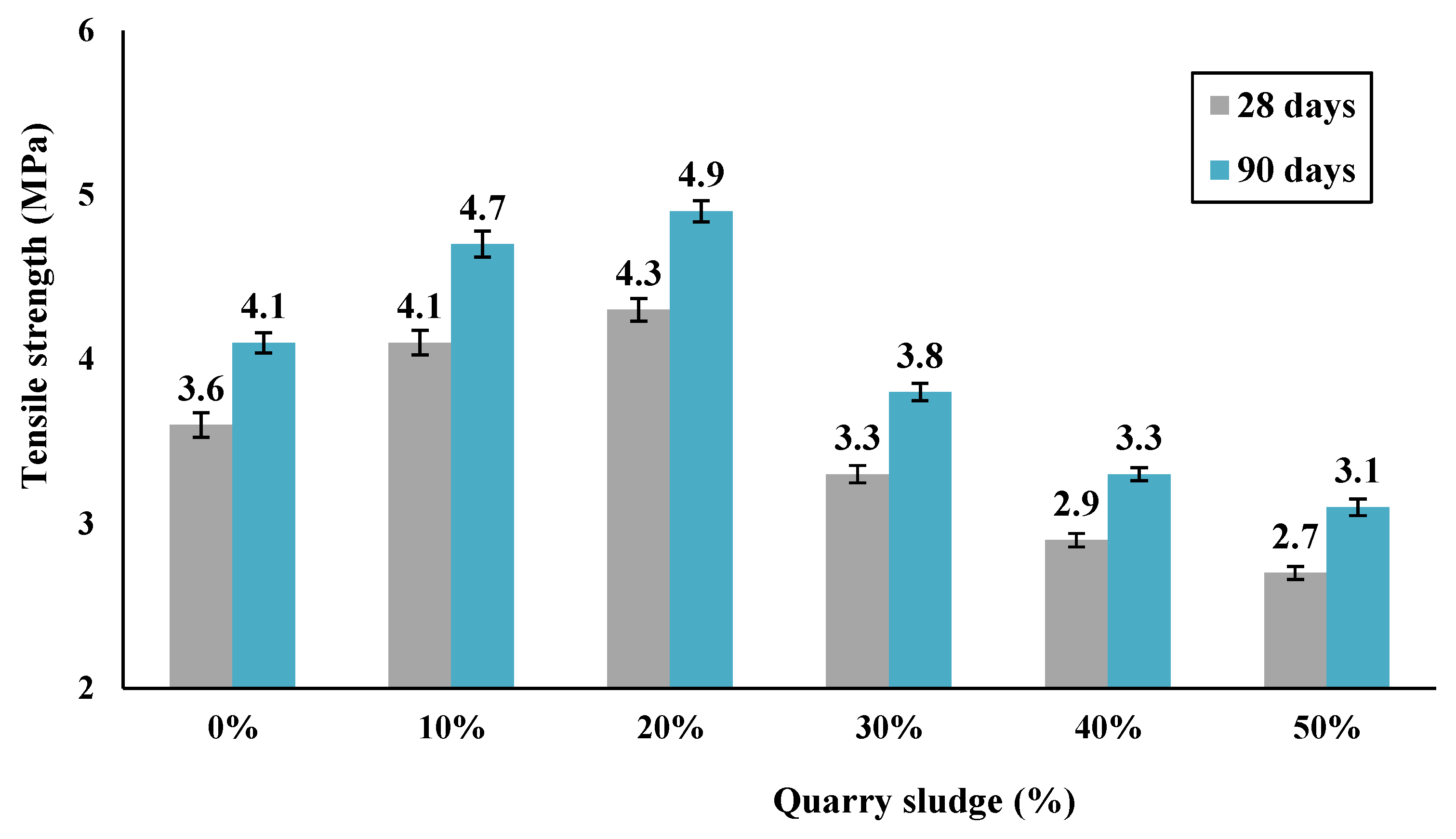

3.4. Tensile Strength

The tensile strength results of the various mix designs are presented in

Figure 6, revealing a distinct trend in response to varying replacement levels of stone quarry sludge (SQS) with fine aggregates. Specifically, tensile strength increases noticeably as the SQS replacement level rises from 0% to 20%. This enhancement can be attributed to several synergistic mechanisms. First, the fine particle size and angular morphology of SQS contribute to improved interfacial bonding between the cement paste and aggregate particles, thereby enhancing matrix cohesion. Second, the partial substitution introduces additional nucleation sites that may accelerate the formation of hydration products, particularly calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel, which plays a critical role in tensile load transfer. Third, the pozzolanic reactivity of SQS may consume calcium hydroxide and generate secondary C–S–H, further densifying the microstructure and reducing microcrack propagation under tensile stress.

However, when the replacement level exceeds 20%, a reverse trend is observed, with tensile strength gradually declining as the SQS content increases up to 50%. This re-duction is likely due to several compounding factors. Excessive SQS can disrupt the optimal particle packing density, leading to poor gradation and reduced internal friction among particles. The high surface area of SQS may also increase water demand, compromising workability and resulting in a less compact matrix. Moreover, elevated SQS levels may introduce microstructural discontinuities and weak interfacial transition zones (ITZs), which act as stress concentrators and reduce the material’s ability to resist tensile forces. Increased porosity and reduced aggregate interlock further exacerbate this decline in performance.

Overall, these findings suggest that a moderate SQS replacement level, specifically around 20%, strikes an optimal balance between microstructural enhancement and mechanical integrity. The adverse effects of excessive fines and disrupted packing outweigh the benefits, underscoring the importance of dosage control when incorporating SQS into high-strength concrete. This insight is critical for developing sustainable mix designs that maintain structural performance while promoting waste valorization.

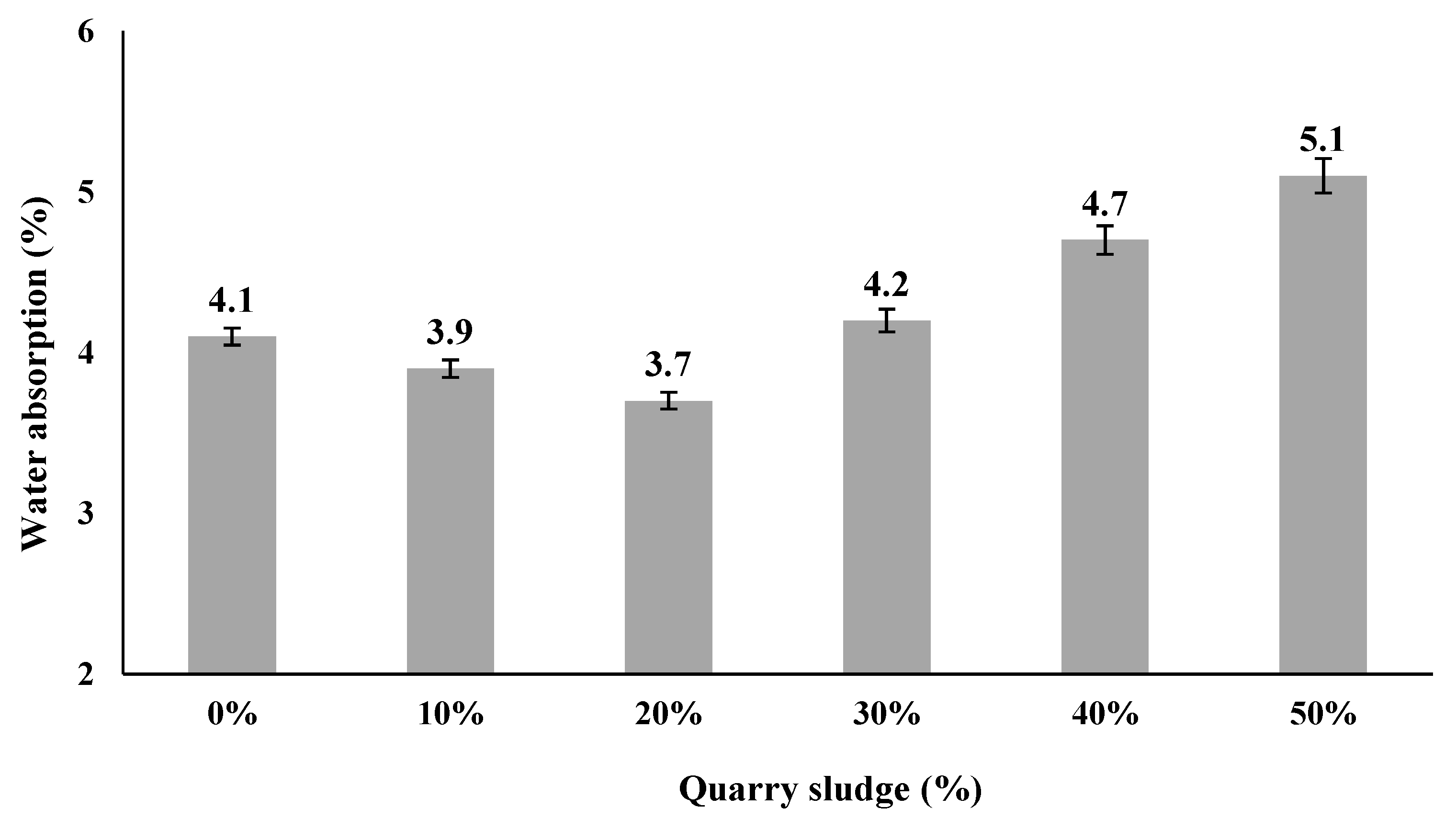

3.5. Percentage of Water Absorption: Cement Matrix Porosity and Durability Tests

Considering that the percentage of water absorption is a key indicator of the porosity of the cement matrix, it provides valuable insights into the material’s durability and overall performance. In this study, the water absorption test was conducted to evaluate how the inclusion of SQS affects the porosity of the composite. The results of these measurements are presented in

Figure 7.

As shown in

Figure 7, there is a clear trend observed with respect to the replacement levels of SQS. Initially, as the percentage of SQS replacement increases up to a certain point, the percentage of water absorption decreases significantly—by approximately 20%. This reduction in water absorption suggests that the pore structure of the cement matrix becomes less porous, which can be attributed to the improved packing density or possibly the filling effect of the SQS particles, leading to a denser and more durable material.

However, beyond this optimal replacement level, specifically when the percentage of SQS exceeds 20%, there is an observable increase in water absorption. The percentage of water absorbed by the specimens begins to rise with further increases in the SQS replacement from 20% to 50%. This increase indicates a corresponding rise in porosity, which can be linked to the potential formation of additional voids or weak interfaces within the cement matrix caused by excessive SQS content.

These findings are consistent with the results observed in the mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and compressive strength, where a similar trend was detected. The initial decrease in water absorption corroborates the improvement in mechanical strength at lower replacement levels, while the subsequent increase at higher replacement percentages explains the observed decline in mechanical performance. Overall, these results highlight the importance of optimizing the SQS replacement percentage to balance porosity and strength, ultimately enhancing the durability and longevity of the cement-based material.

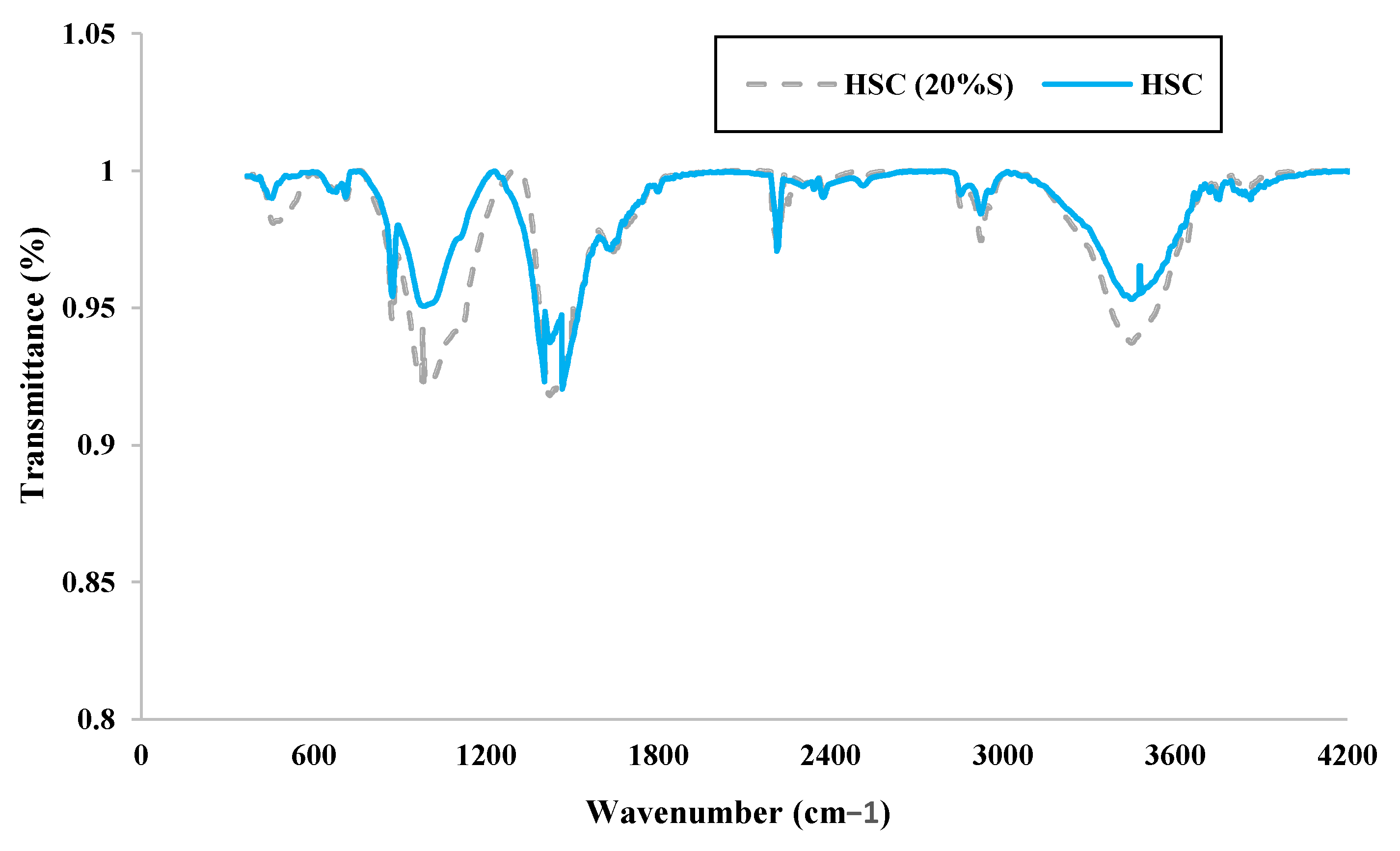

3.6. FTIR Test

To gain deeper insight into the microstructural implications of quarry sludge incorporation, FTIR spectroscopy was performed on two representative mix designs: the control high-strength concrete (HSC) and HSC containing 20% stone quarry sludge (SQS) as a partial replacement for fine aggregates. This comparative analysis was designed to elucidate the chemical transformations and hydration product evolution associated with the optimal replacement level, thereby linking spectroscopic features to mechanical performance.

Figure 8 presents the FTIR spectra of both mixes, revealing distinct differences in their chemical profiles. A pronounced absorption band appears in the region of 960–1120 cm

−1, which corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si–O bonds in calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel—a primary hydration product responsible for strength development in cementitious systems. The HSC (20% SQS) sample exhibits a notably higher peak intensity in this region compared to the control mix, indicating a greater concentration of C–S–H phases.

This enhancement in C–S–H formation is attributed to the pozzolanic activity of the fine particles present in SQS, which react with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) liberated during cement hydration. The secondary reaction produces additional C–S–H gel, thereby densifying the microstructure and improving the continuity of the cement matrix. Such densification is critical for enhancing compressive and flexural strength, as well as reducing porosity and permeability.

In addition to peak intensity, the spectral shape and sharpness of the C–S–H band in the HSC (20% SQS) mix suggest a more polymerized and refined silicate network. This structural refinement implies improved gel connectivity and reduced microstructural defects, which are favorable for long-term durability. The presence of sharper bands also indicates a higher degree of crystallinity or ordered gel structure, which may contribute to enhanced resistance against environmental degradation.

Furthermore, minor shifts in peak positions and the emergence or suppression of secondary bands—such as those near 1420 cm−1 (associated with carbonate phases) and 3640 cm−1 (linked to hydroxyl groups)—were observed. These changes reflect subtle alterations in hydration dynamics and chemical interactions induced by the SQS addition.

Overall, the FTIR analysis provides robust spectroscopic evidence of enhanced hydration and microstructural development in the HSC (20% SQS) mix. These findings corroborate the mechanical test results and validate the beneficial role of SQS in promoting the formation of strength-contributing phases. The integration of FTIR data with mechanical and environmental assessments strengthens the scientific foundation of this study and supports the viability of quarry sludge as a sustainable additive in high-performance concrete.

3.7. Carbon Footprint Results

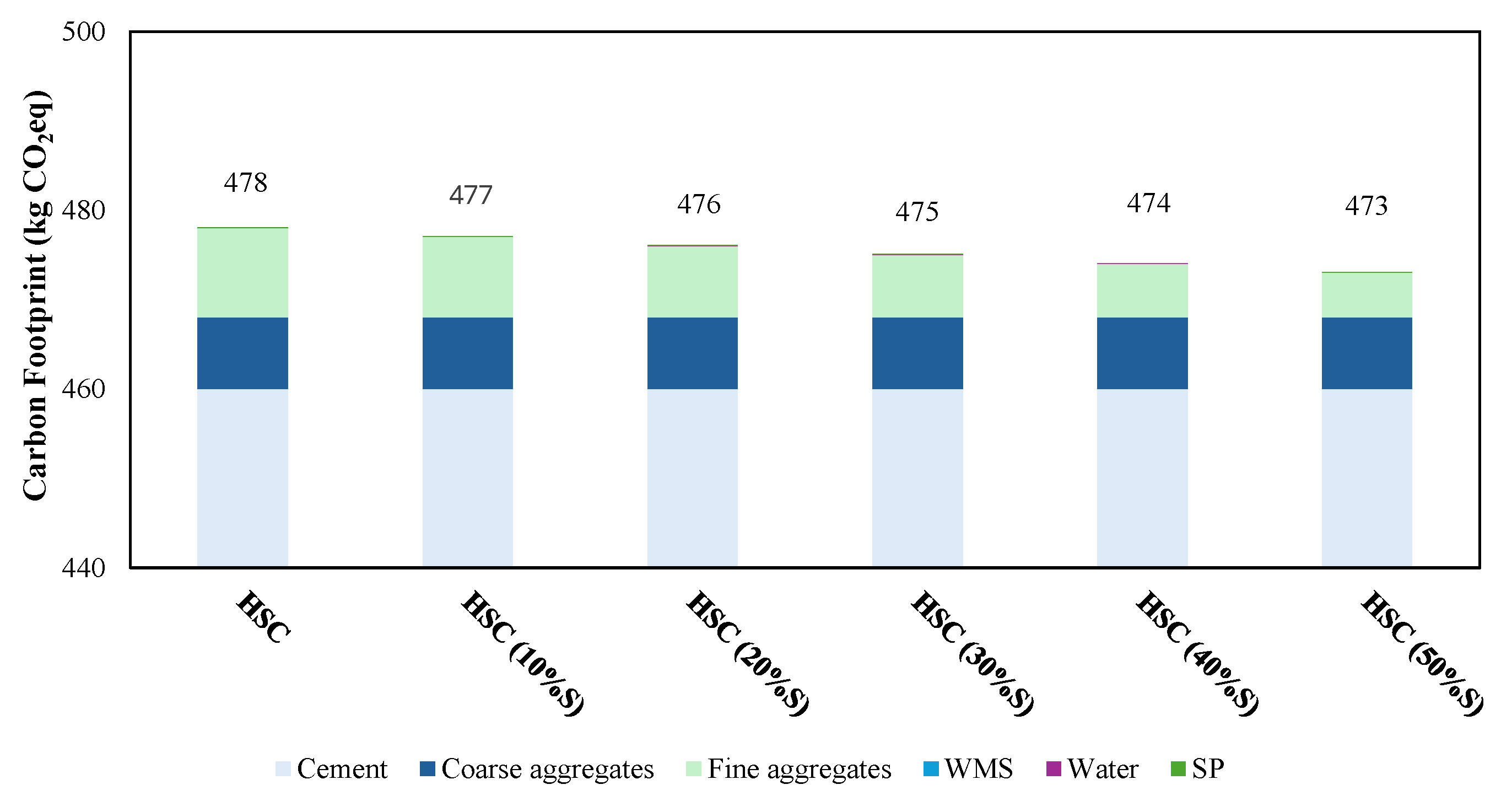

The estimated carbon footprint values for all high-strength concrete (HSC) mixtures incorporating varying proportions of stone quarry sludge (SQS) are presented in

Figure 9. The calculated results reveal a clear declining trend in the total embodied carbon with increasing SQS content. The control mix (HSC without sludge) exhibited the highest footprint at approximately 478 kg CO

2-eq/m

3, primarily due to the high contribution of cement production. As the replacement of fine aggregates by SQS increased from 10% to 50%, the carbon footprint gradually decreased from 477 kg CO

2-eq/m

3 to 473 kg CO

2-eq/m

3.

This reduction in embodied carbon, although moderate in absolute terms (≈1% decrease between the control and 50% SQS mix), highlights the positive environmental potential of replacing natural sand with quarry sludge—particularly when considering that SQS is a waste by-product requiring minimal processing. The declining trend corresponds to the avoided environmental burdens associated with quarrying, crushing, and transporting natural aggregates. The most efficient balance between environmental performance and mechanical strength was achieved at the 20% replacement level, which not only exhibited the highest compressive and flexural strengths but also achieved a 2–3 kg CO2-eq/m3 reduction relative to the control.

These findings confirm that even limited substitution of natural aggregates with quarry sludge can yield measurable environmental benefits without compromising the mechanical integrity of the concrete. Moreover, the inclusion of SQS aligns with circular economy principles by reducing natural resource consumption and promoting waste valorization in concrete production. Future work should expand this assessment to include the transportation phase, long-term durability benefits, and end-of-life recycling to provide a complete cradle-to-grave life-cycle evaluation.

3.8. Benchmarking Against International Standards

To validate the structural applicability of the obtained mechanical test results, particularly the compressive and flexural strengths of HSC incorporating stone quarry sludge (SQS), the data have been benchmarked against relevant national and international standards for HSC performance.

According to standard practice for fabricating and testing specimens of Ultra-High Performance Concrete, high-strength concrete is typically defined as having compressive strength values exceeding 50 MPa, with structural-grade mixes often reaching up to 120 MPa under optimized conditions. Similarly, EN widely adopted across Europe, classifies HSC as concrete achieving compressive strengths of ≥55 MPa, designated under strength classes such as C55/67, C60/75, and beyond.

The current study’s findings, particularly the peak compressive strength of 61 MPa achieved at a 20% SQS replacement level, demonstrate clear compliance with both benchmarks. This value exceeds the minimum thresholds established by EN 206 [

64] and aligns with the performance range considered acceptable under ASTM for structural applications in high-performance environments.

Furthermore, the recorded flexural strength of 5.1 MPa at the same replacement level aligns favorably with typical structural concrete flexural performance, especially in applications requiring enhanced crack resistance and durability, such as precast elements and beams. While neither ASTM prescribe specific flexural strength requirements, these values fall within the performance envelope expected of HSC with optimized mix design and curing conditions.

Overall, while the study does not claim full certification against ASTM or EN standards (as this would require standard-specific testing protocols and validations), the comparative performance analysis demonstrates that the SQS-modified HSC meets—and in certain aspects exceeds—minimum mechanical thresholds for structural-grade concrete. These results, therefore, provide a solid foundation for considering SQS as a viable and sustainable alternative material in high-performance concrete applications, pending further long-term durability and environmental safety evaluations.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a novel approach to enhancing high-strength concrete (HSC) by partially replacing natural sand with stone quarry sludge (SQS), aiming to improve material performance while contributing to sustainability goals. Through a comprehensive experimental program—including compressive strength, flexural strength, and specific weight tests—the feasibility of SQS incorporation was systematically evaluated, yielding valuable insights into its mechanical behavior and environmental implications.

The results indicate that moderate substitution, particularly at a 20% replacement level, improves key performance metrics, with compressive and flexural strengths reaching 61 MPa and 5.1 MPa, respectively. This enhancement is attributed to improved particle packing and matrix densification, suggesting that SQS can serve as a viable, low-cost alternative to natural aggregates. However, higher replacement levels led to strength reductions, underscoring the importance of optimized mix design to maintain structural integrity.

A carbon footprint analysis further revealed a modest but consistent reduction in embodied carbon—from 478 to 473 kg CO2-eq/m3—primarily due to reduced reliance on virgin sand. While the environmental impact is incremental, the findings support the potential of SQS to contribute to more resource-efficient concrete production. Overall, this work contributes to the growing body of research on sustainable concrete technologies by demonstrating the mechanical viability and environmental benefit of quarry sludge utilization. It opens avenues for further exploration into synergistic material combinations, durability enhancement strategies, and lifecycle-based optimization of eco-efficient concrete.

5. Limitations and Future Work

While this study provides promising evidence for the mechanical and environmental viability of incorporating SQS into HSC, several limitations should be acknowledged. The current investigation primarily focuses on macro-scale performance indicators such as compressive strength, flexural strength, and specific weight, supported by FTIR analysis for microstructural interpretation. However, the explanation of strength development mechanisms remains largely phenomenological and would benefit from more detailed microstructural characterization.

To deepen the understanding of the interactions between SQS particles and the cementitious matrix, advanced analytical techniques such as Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP), Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) are recommended. These methods can provide insights into pore structure evolution, hydration product morphology, and elemental distribution, thereby clarifying the role of SQS in modifying the microstructure and influencing mechanical behavior.

Additionally, the study did not address long-term durability aspects such as resistance to chloride penetration, sulfate attack, freeze–thaw cycles, or carbonation—all of which are critical for structural applications. Future research should incorporate these durability assessments under various environmental exposures to validate the long-term performance of SQS-based HSC.

Another limitation lies in the specificity of the SQS source. Since the chemical and physical properties of quarry sludge can vary significantly depending on geological origin and processing methods, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Broader studies involving multiple SQS sources and regional aggregates are necessary to establish robust mix design guidelines.

Finally, life cycle assessment (LCA) beyond embodied carbon—encompassing energy consumption, water usage, and end-of-life scenarios—would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the environmental benefits of SQS utilization.

In summary, while the current study demonstrates the feasibility and potential of SQS as a sustainable partial sand replacement in HSC, further interdisciplinary investigations are essential to fully unlock its performance capabilities and support its adoption in practical construction applications.