Dynamic Mechanical Performance of 3D Woven Auxetic Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Development of 3D Woven Structures

2.3. Fabrication of 3D Woven Thermoplastic Composites

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

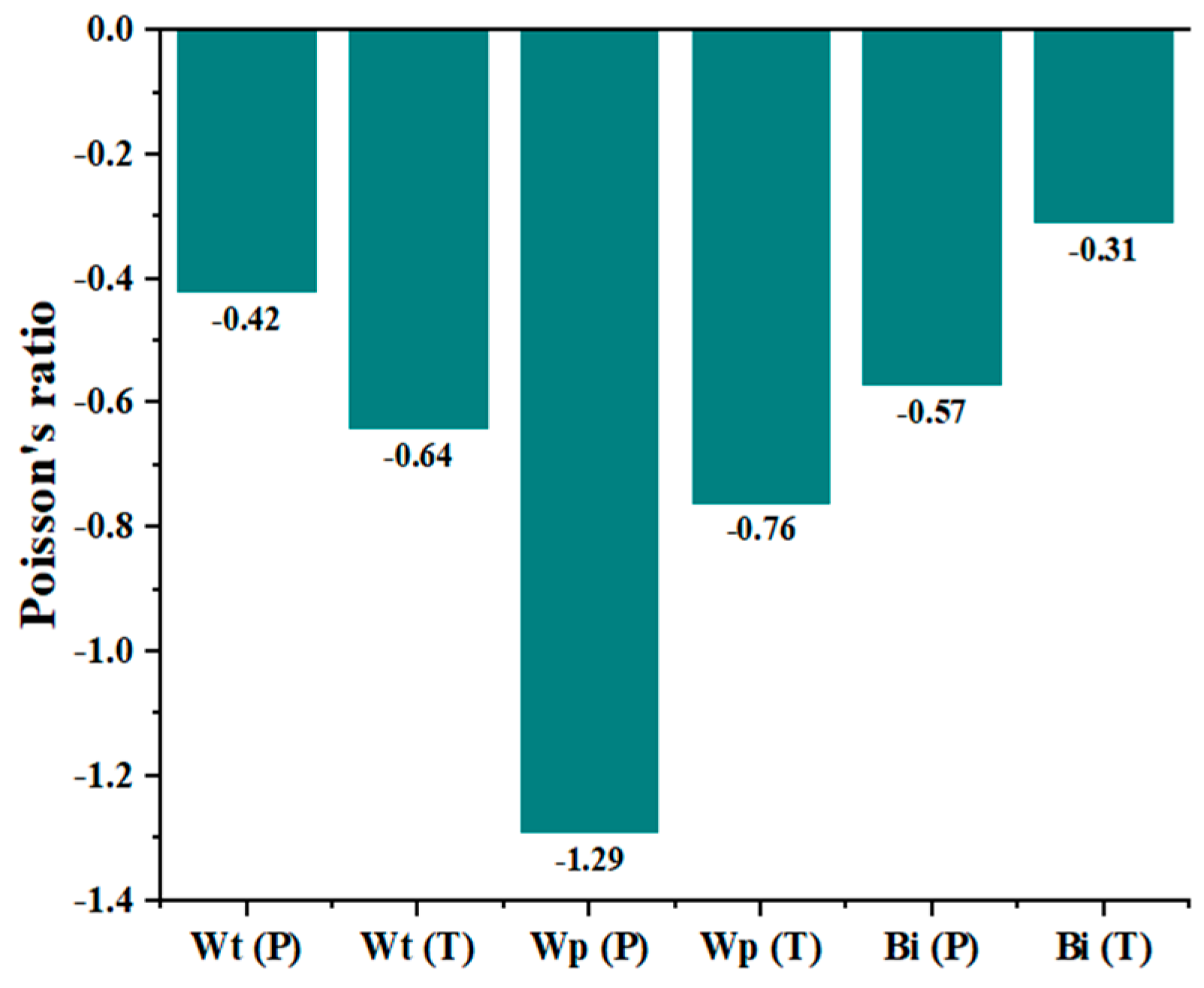

3.1. Reinforcement Auxeticity

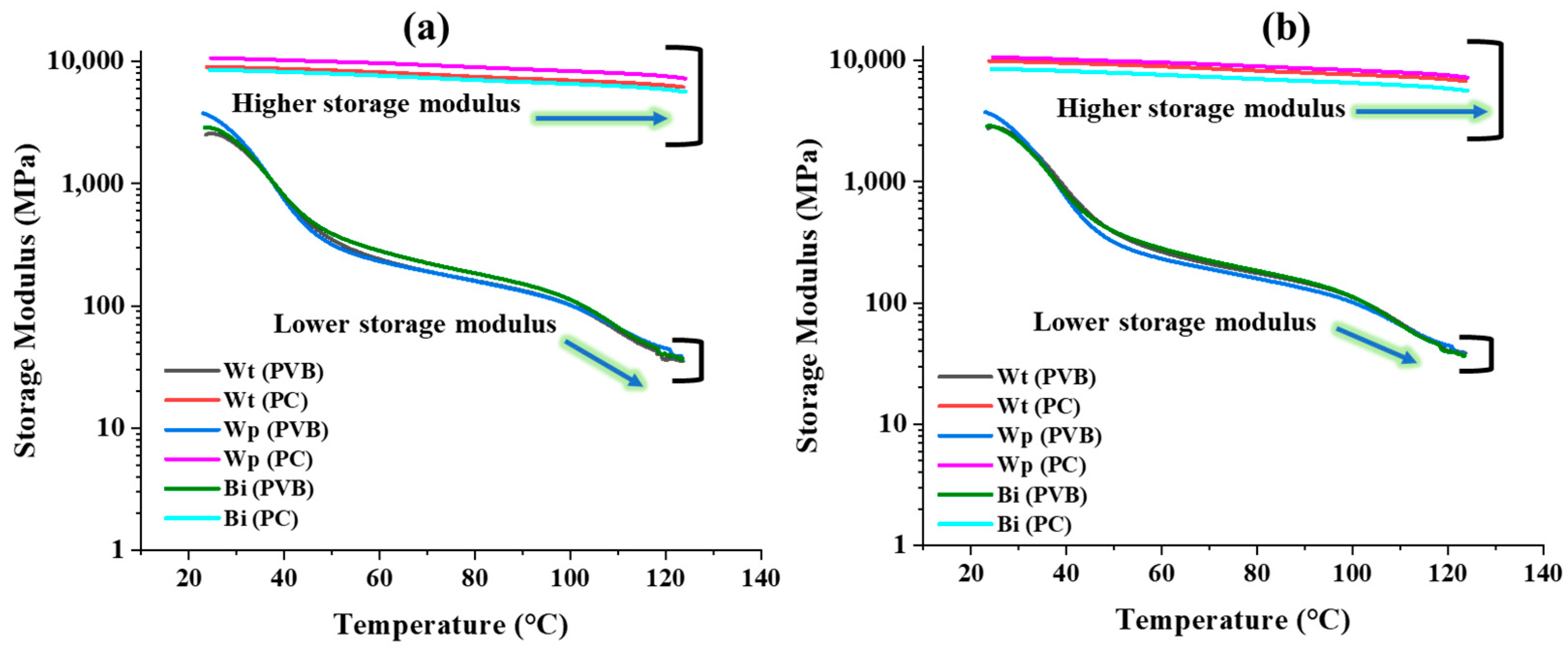

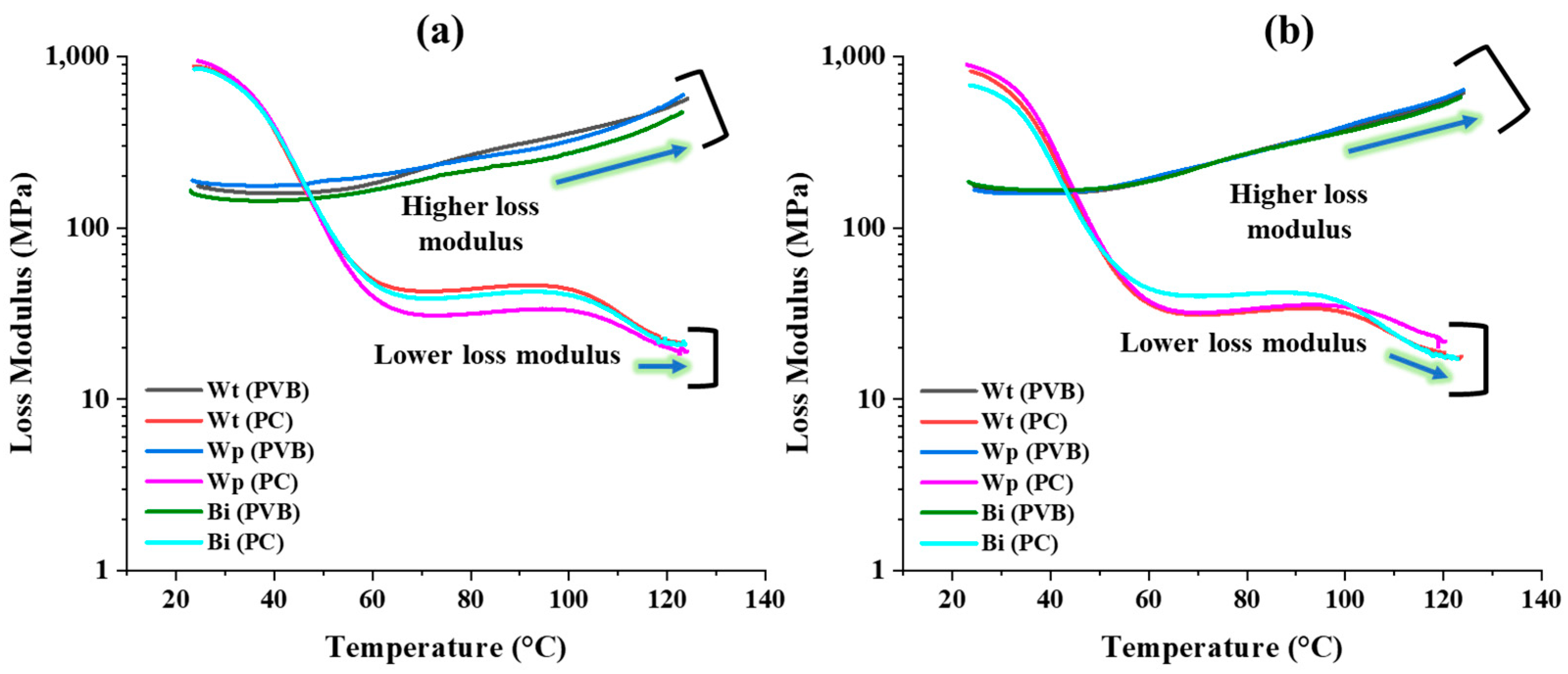

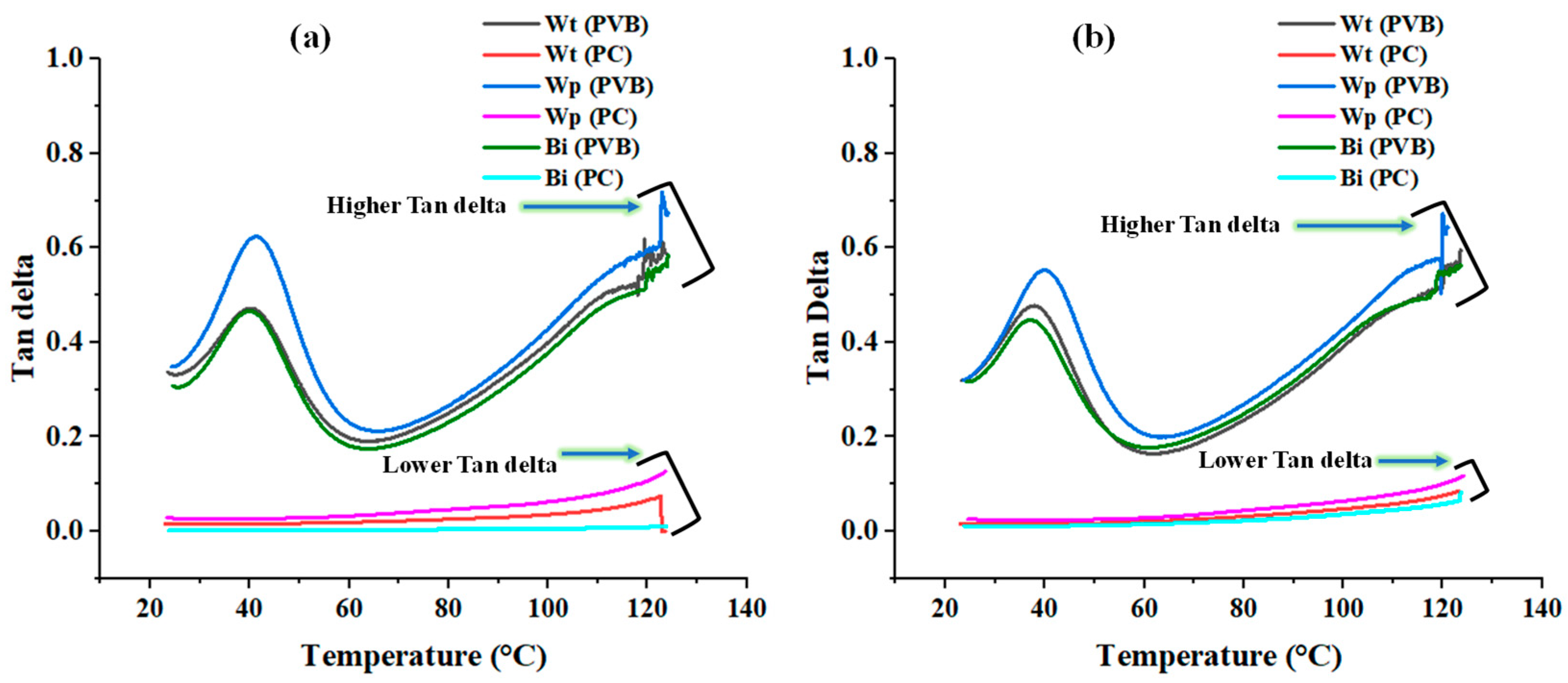

3.2. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

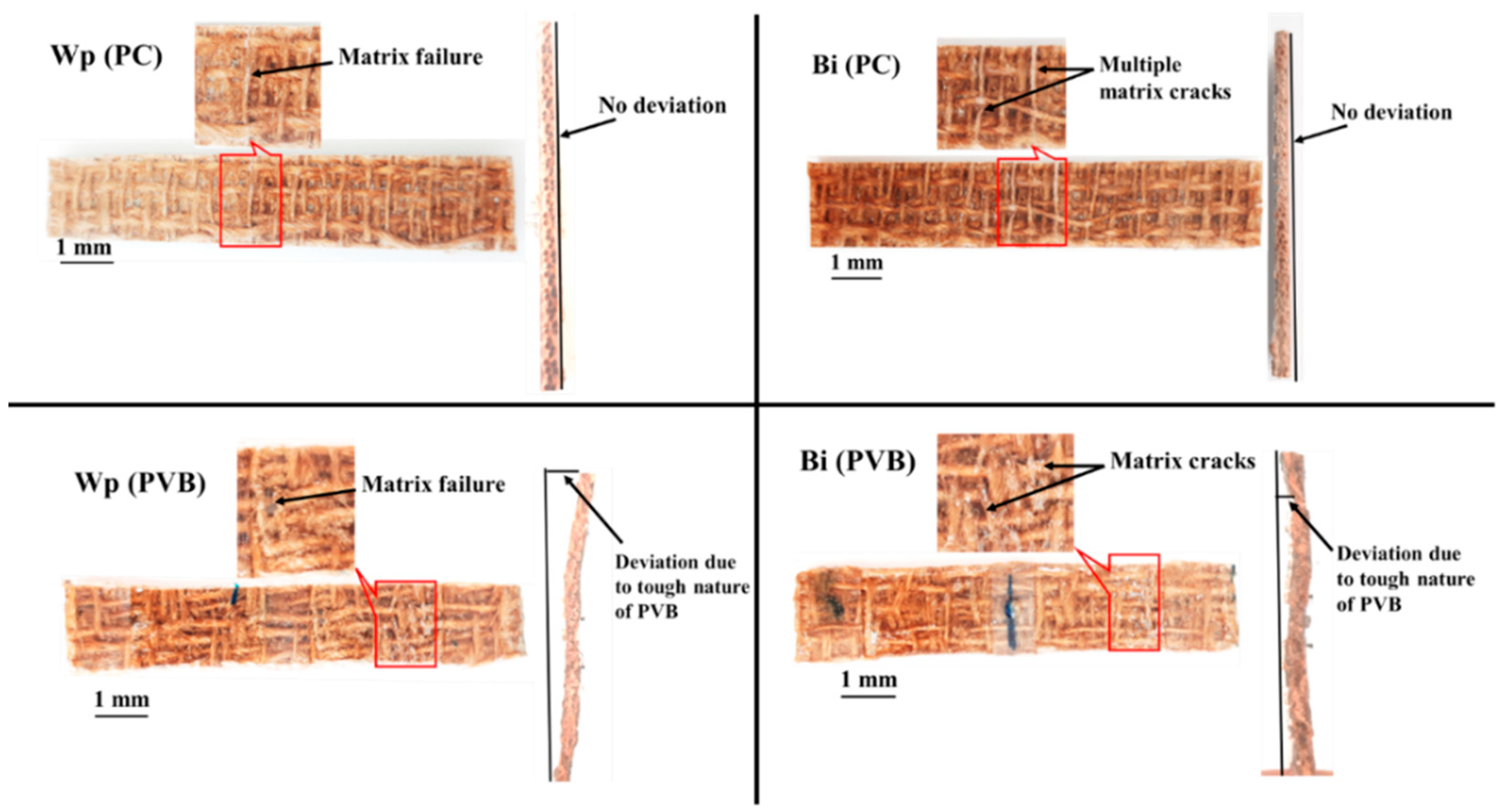

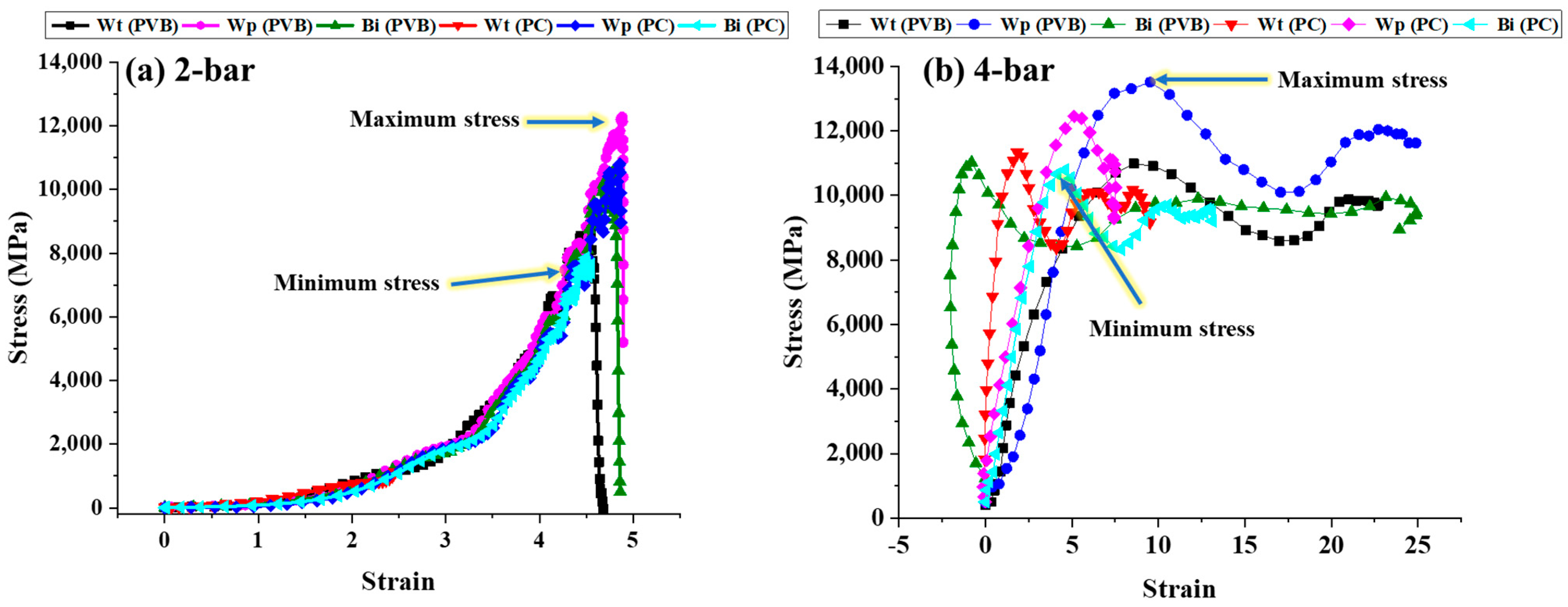

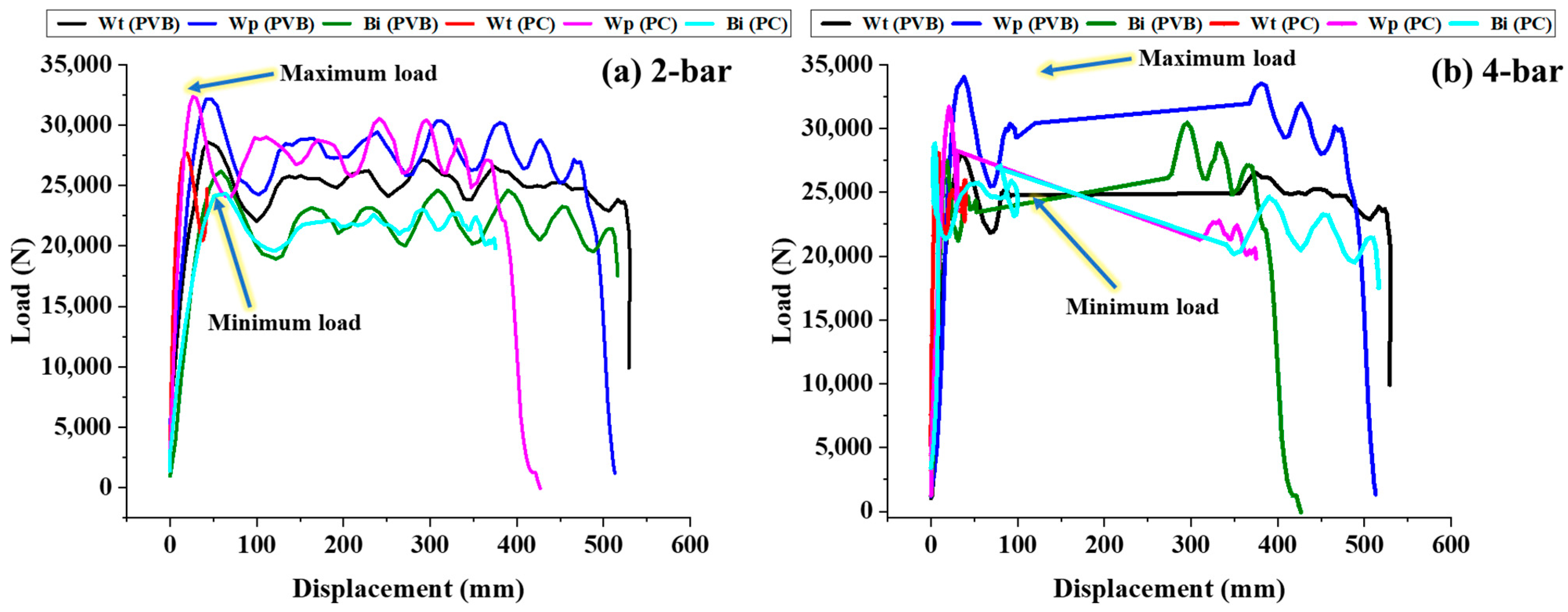

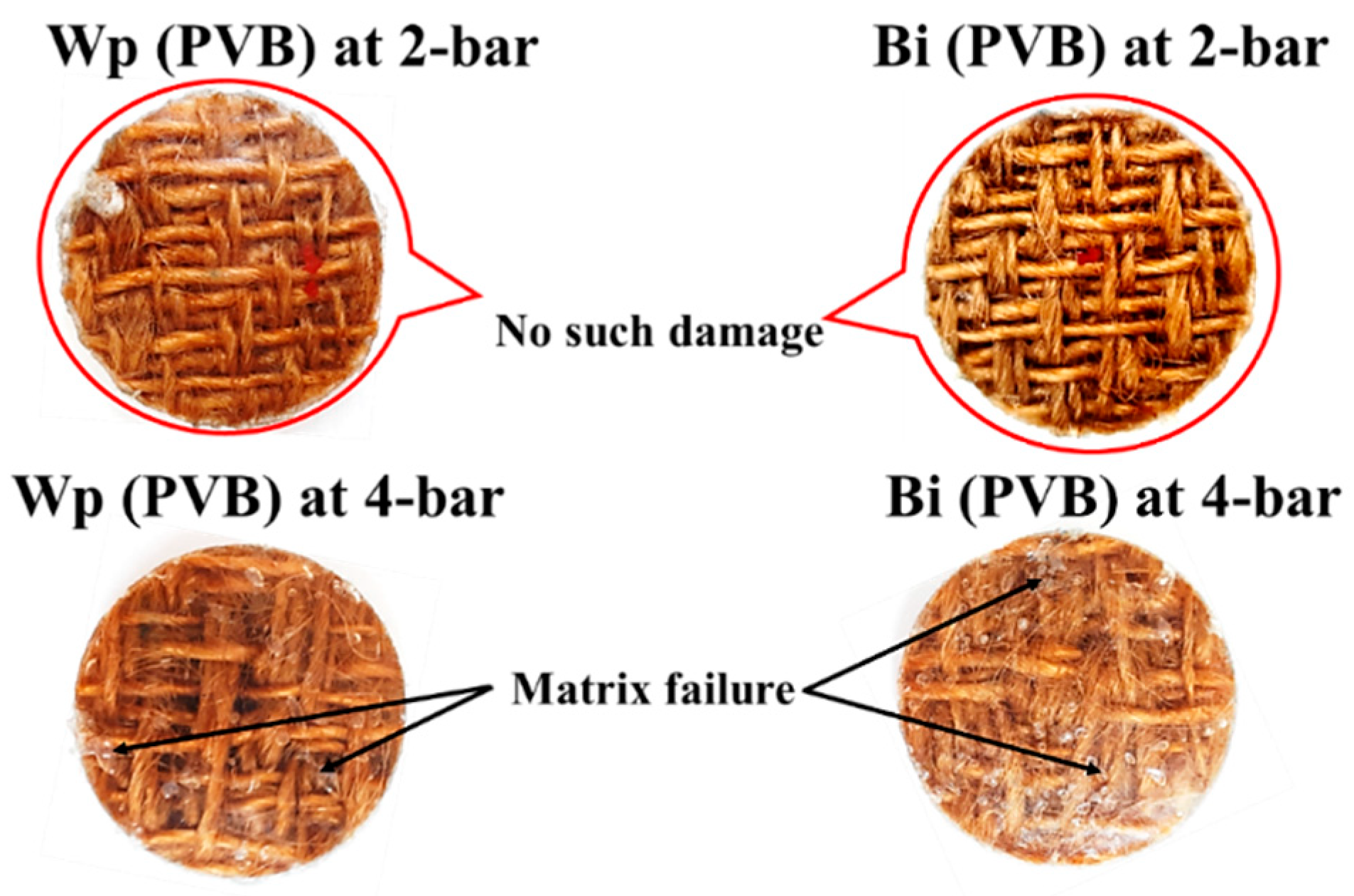

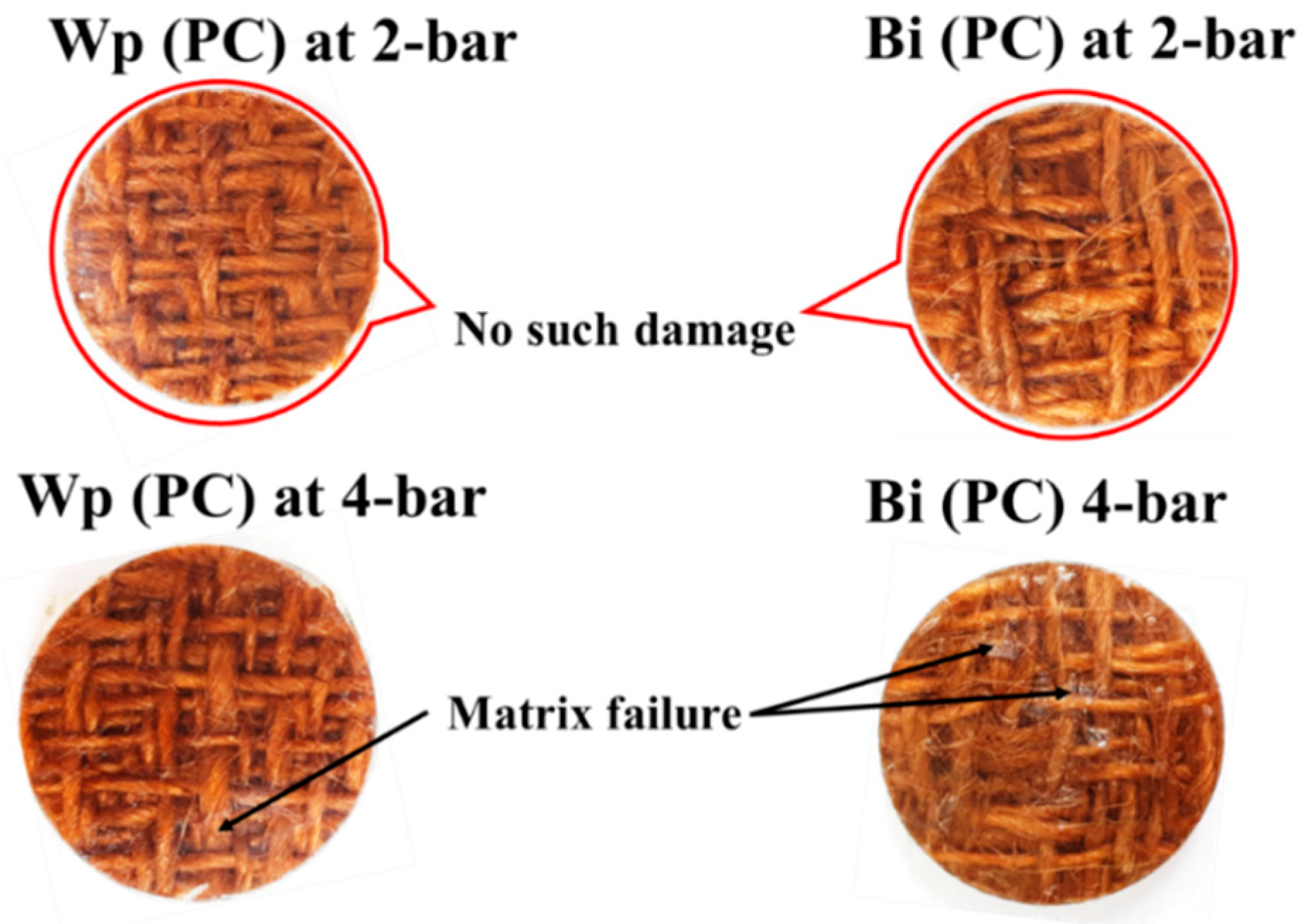

3.3. Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB)

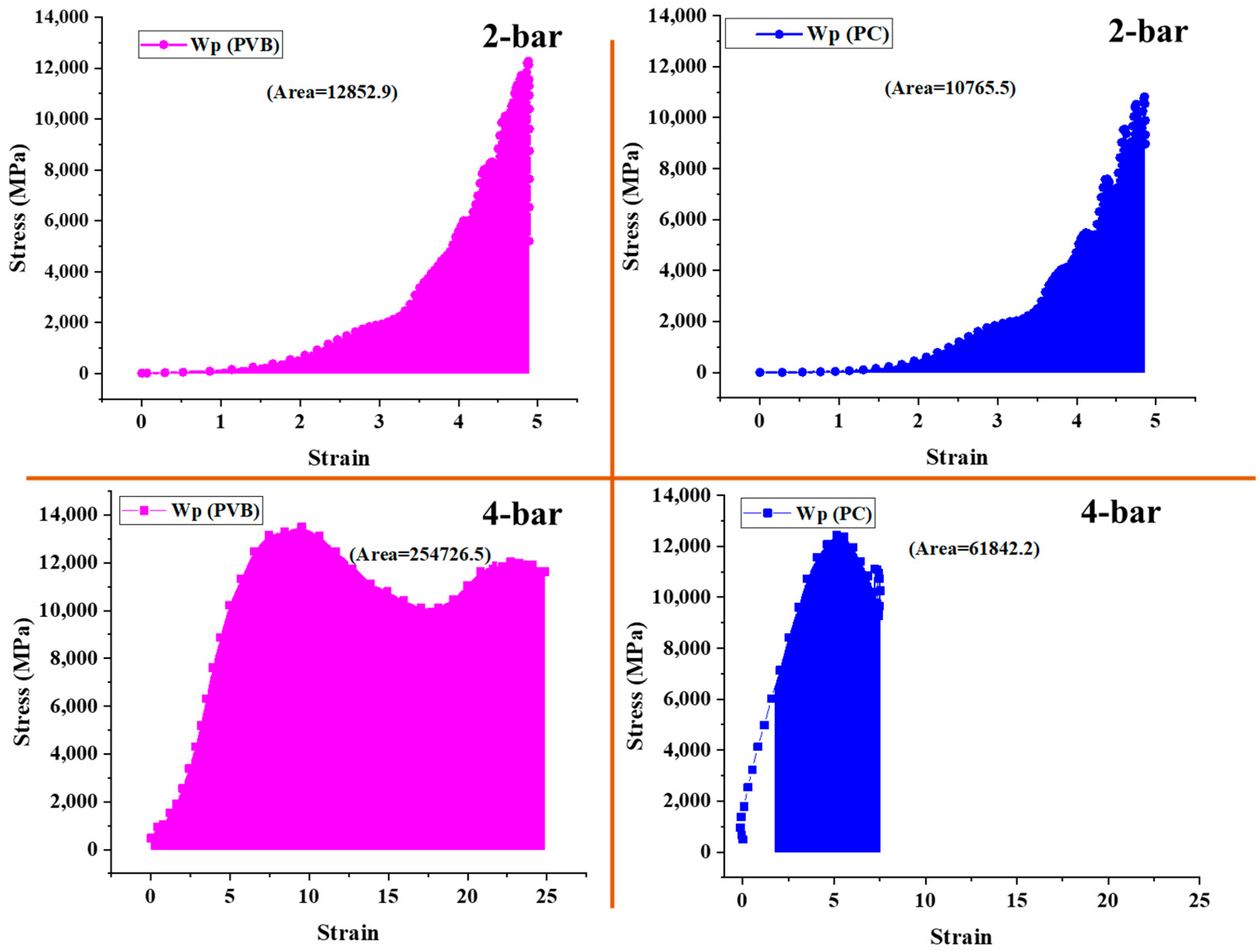

3.4. Energy Absorption/Toughness Behavior

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grosicki, Z.J. Watson’s Textile Design and Colour, 7th ed.; Butter Worths Group: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Nawab, Y.; Hamdani, T.; Shaker, K. Structural Textile Design: Interlacing and Interlooping; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, L.; Mouritz, A.; Bannister, M. Chapter 2—Manufacture of 3D fibre preforms. In 3D Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Advances in 3D Textiles; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Mouritz, A.; Bannister, M. Chapter 5—3D woven composites. In 3D Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’ANno, G.; Partridge, I.; Cartié, D.; Hamlyn, A.; Chehura, E.; James, S.; Tatam, R. Automated manufacture of 3D reinforced aerospace composite structures. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2012, 3, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.N.; Kumar, A. 3d Multilayer Woven Preform for Civil Works; Kanpur, India, 2013.

- Dufour, C.; Pineau, P.; Wang, P.; Soulat, D.; Boussu, F. Three-dimensional textiles in the automotive industry. In Advances in 3D Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K. Thermoplastics and thermoplastic—Matrix composites for lightweight automotive structures. In Materials, Design and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 187–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, T.; Nawab, Y.; Umair, M. 3D woven natural fiber structures. In Multiscale Textile Preforms and Structures for Natural Fiber Composites; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Nawab, Y.; Malik, M.H.; Shaker, K. Development and characterization of three-dimensional woven-shaped preforms and their associated composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2015, 34, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Hamdani, S.T.A.; Asghar, M.A.; Hussain, T.; Karahan, M.; Nawab, Y.; Ali, M. Study of influence of interlocking patterns on the mechanical performance of 3D multilayer woven composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2018, 37, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, D.; Fatima, N.; Rehan, M.; Hu, H. Sustainable jute fiber-reinforced auxetic composites with both in-plane and out-of-plane auxetic behaviors. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, S922–S939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomarah, A.; Masood, S.H.; Ruan, D. Out-of-plane and in-plane compression of additively manufactured auxetic structures. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 106107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, D.; Zhang, M.; Hu, H. Auxetic Materials for Personal Protection: A Review. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic Res. 2022, 259, 2200324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.I.; Umair, M.; Nawab, Y.; Hamdani, S.T.A. Development of 3D auxetic structures using para-aramid and ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene yarns. J. Text. Inst. 2020, 112, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, F.; Umair, M.; Shaker, K.; Nawab, Y.; Ullah, T.; Ahmad, S. Investigation of Chemical Treatments to Enhance the Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhare, K.S.; Mahesh, V.; Joladarashi, S.; Kulkarni, S.M. Comparative study on low velocity impact behavior of natural hybrid and non hybrid flexible thermoplastic based composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2022, 36, 089270572211455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, D.; Hoa, S.V.; Tsai, S.W. Composite Materials: Design and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.H. Applications of composites: An overview. In Concise Encyclopedia of Composite Materials; Pergamon Press plc: Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Baillie, C. Green Composites: Polymer Composites and the Environment; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, Z.; Razzaq, W.; Abbas, A.; Hussain, F.; Ghalib, E.; Ayyoob, M.; Hamdani, S.T.A. Thermal activation and dynamic mechanical characterization of glass-reinforced shape memory polymer composites for medical applications. Text. Res. J. 2025, 95, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Guan, Z.; Qin, J.; Wen, Y.; Lai, Z. Strain rate effect of concrete based on split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Chen, L.; Gao, J.; Wu, Z.-Y. Improving the dynamic stiffness and vibration characteristics of 3D orthogonal woven by implanting SMA instead of a warp yarn. Compos. Struct. 2023, 307, 116637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Xu, Q.; Lv, J.; Xu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Qin, J. Bioinspired 3D helical fibers toughened thermosetting composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 216, 108855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Zhang, F.; Peng, X.; Scarpa, F.; Huang, Z.; Tao, G.; Liu, H.-Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, H. Improving the damping properties of carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites by interfacial sliding of oriented multilayer graphene oxide. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 224, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, T.; Hussain, M.; Ali, M.; Umair, M. Impact of auxeticity on mechanical properties of 3D woven auxetic reinforced thermoplastic composites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, T.; Hussain, M.; Ali, M.; Umair, M. Impact performance of jute 3D woven auxetic reinforced thermoplastic (PC/PVB) composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2024, 43, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, T.; Gao, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, H.; Han, Q.; Qin, Z. An iterative method for identification of temperature and amplitude dependent material parameters of fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 184, 105818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Yuvaraj, N.; Bajpai, P.K. Influence of reinforcement architecture on static and dynamic mechanical properties of flax/epoxy composites for structural applications. Compos. Struct. 2021, 255, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, B.; Gu, B.; Hu, M. Modeling impact compressive behaviors of 3D woven composites under low temperature and strain rate effect. Compos. Struct. 2024, 345, 118402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, D.-S.; Jia, X.-L.; Zuo, H.-M.; Jiang, L.; Lomov, S.V.; Desplentere, F. Experimental and numerical validation of high strain rate impact response and progressive damage of 3D orthogonal woven composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 258, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Niu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Gu, B. Mechanical Behaviors of 2D and 3D Basalt Fiber Woven Composites Under Various Strain Rates. J. Compos. Mater. 2010, 44, 1779–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wei, H.; Gu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, C. Size-dependent mechanical behaviors of 3D woven composite under high strain-rate compression loads. Polym. Test. 2023, 127, 108176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, T.; Hussain, M.; Ali, M.; Umair, M. Auxetic behavior of 3D woven warp, weft and bi-directional interlock structures. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 24, 2168823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.; Gong, L.; Zhou, H. A molecular dynamics assisted insight on damping enhancement in carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites with oriented multilayer graphene oxide coatings. Microstructures 2024, 4, 2024051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Khan, M.; Akram, J.; Umair, M.; Hamdani, S.T.; Shaker, K.; Nawab, Y.; Zeeshan, M. Development of composites, reinforced by novel 3D woven orthogonal fabrics with enhanced auxeticity. J. Ind. Text. 2019, 49, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.T.; da Silveira, P.H.P.M.; Figueiredo, A.B.-H.d.S.; Monteiro, S.N.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Neuba, L.d.M.; Simonassi, N.T.; Filho, F.d.C.G.; Nascimento, L.F.C. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis and Ballistic Performance of Kenaf Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Huang, J.; Chen, M.; Dong, W. Polycarbonate blends with high environmental stress crack resistance, high strength and high toughness by introducing polyvinyl butyral at small fraction. Polymer 2022, 242, 124578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, M.; Akin, E.; Renda, G. Mechanical properties of carbon-aramid hybrid fiber-reinforced epoxy/poly (vinyl butyral) composites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 4826–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilento, F.; Bassano, A.; Sorrentino, L.; Martone, A.; Giordano, M.; Palmieri, B. PVB Nanocomposites as Energy Directors in Ultrasonic Welding of Epoxy Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, K.; Jabbar, A.; Karahan, M.; Karahan, N.; Nawab, Y. Study of dynamic compressive behaviour of aramid and ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene composites using Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar. J. Compos. Mater. 2017, 51, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.F.; Akil, H.M.; Ahmad, Z.A.; Mazuki, A.; Yokoyama, T. Dynamic properties of pultruded natural fibre reinforced composites using Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar technique. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 4209–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.A.A.; Iannucci, L.; Greenhalgh, E.S. On the dynamic tensile behaviour of thermoplastic composite carbon/polyamide 6.6 using split hopkinson pressure bar. Materials 2021, 14, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, Z.; Ali, M. 3D woven auxetic composites using on-loom shaped reinforcement. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 13137–13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadi, E.; Zhang, M.; Gholikord, M.; Li, K.; Ho, M.M.P.; Hu, H. Quasi-static and dynamic behavior analysis of 3D CFRP woven laminated composite auxetic structures. Compos. Struct. 2024, 340, 118182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanical Properties | Jute Yarn | PC | PVB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear density (tex) | 236.2 | - | - |

| Tenacity (cN/tex) | 11.45 | - | - |

| Elongation (%) | 1.30 | - | - |

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.35 | 1.20 | 1.12 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | - | 2.3 | 1.9 |

| Yield stress (MPa) | - | 65 | 25 |

| Strain to failure (%) | - | 100 | 150 |

| Toughness (Mj/m3) | - | 70 | 20 |

| Weave Structure | Ends/Inch | Picks/Inch | Areal Density (g/cm2) | Crimp % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warp | Weft | ||||

| Warp interlock (Wp) | 37 ± 01 | 36 ± 01 | 745 ± 01 | 2.10 ± 0.01 | 1.25 ± 0.01 |

| Weft interlock (Wt) | 38 ± 01 | 37 ± 01 | 785 ± 02 | 2.20 ± 0.02 | 1.75 ± 0.01 |

| Bidirectional interlock (Bi) | 41 ± 01 | 39 ± 01 | 845 ± 02 | 2.40 ± 0.02 | 1.85 ± 0.02 |

| 3D Woven Reinforcements | Sample Code | 3D Woven Composites | Sample Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weft interlock (warp-wise) | Wt (P) | Weft interlock with PVB | Wt (PVB) |

| Weft interlock (weft-wise) | Wt (T) | Weft interlock with PC | Wt (PC) |

| Warp interlock (warp-wise) | Wp (P) | Warp interlock with PVB | Wp (PVB) |

| Warp interlock (weft-wise) | Wp (T) | Weft interlock with PC | Wp (PC) |

| Bidirectional interlock (warp-wise) | Bi (P) | Bidirectional interlock with PVB | Bi (PVB) |

| Bidirectional interlock (weft-wise) | Bi (T) | Bidirectional interlock with PC | Bi (PC) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Umair, M.; Ullah, T.; Abbas, A.; Nawab, Y.; Seyam, A.-F.M. Dynamic Mechanical Performance of 3D Woven Auxetic Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120649

Umair M, Ullah T, Abbas A, Nawab Y, Seyam A-FM. Dynamic Mechanical Performance of 3D Woven Auxetic Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):649. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120649

Chicago/Turabian StyleUmair, Muhammad, Tehseen Ullah, Adeel Abbas, Yasir Nawab, and Abdel-Fattah M. Seyam. 2025. "Dynamic Mechanical Performance of 3D Woven Auxetic Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120649

APA StyleUmair, M., Ullah, T., Abbas, A., Nawab, Y., & Seyam, A.-F. M. (2025). Dynamic Mechanical Performance of 3D Woven Auxetic Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120649