Performance of Rubber Seals for Cable-Based Tsunameter with Varying Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer and Filler Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Compounding

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Testing Methods

2.4.1. Curing Properties

2.4.2. Mechanical Properties

2.4.3. Swelling Testing

2.4.4. Dynamic Mechanical -Analysis

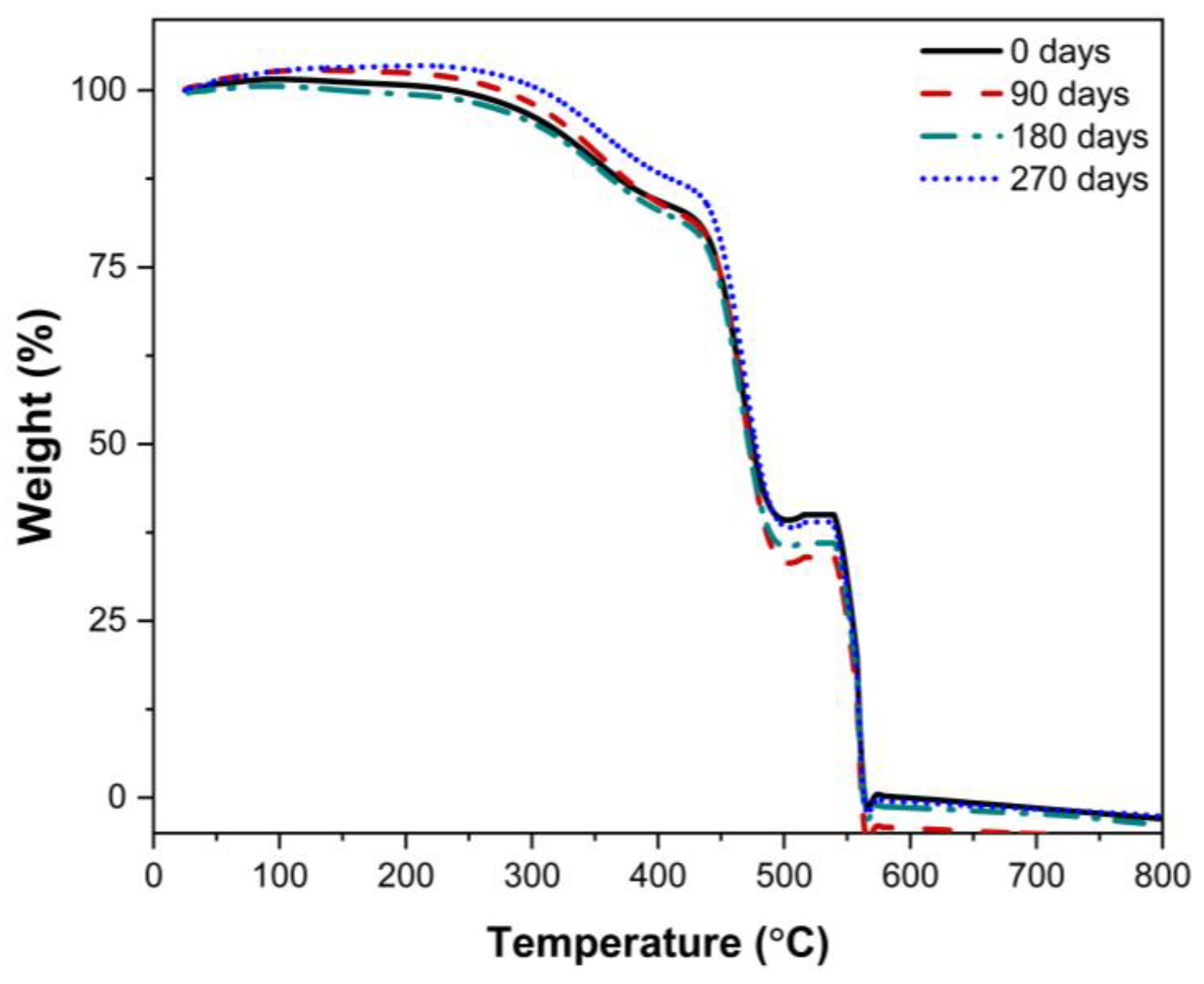

2.4.5. Thermal Analysis

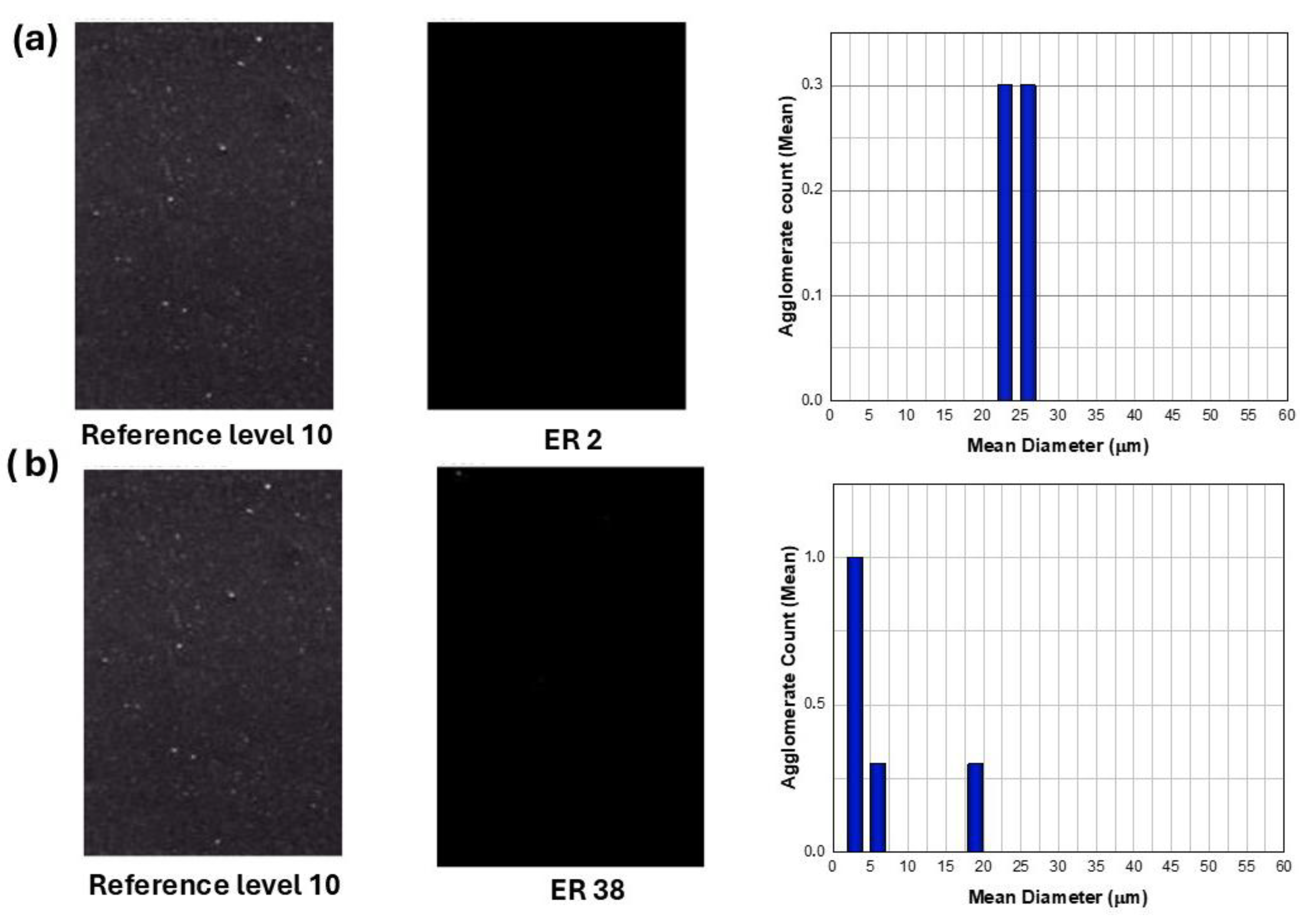

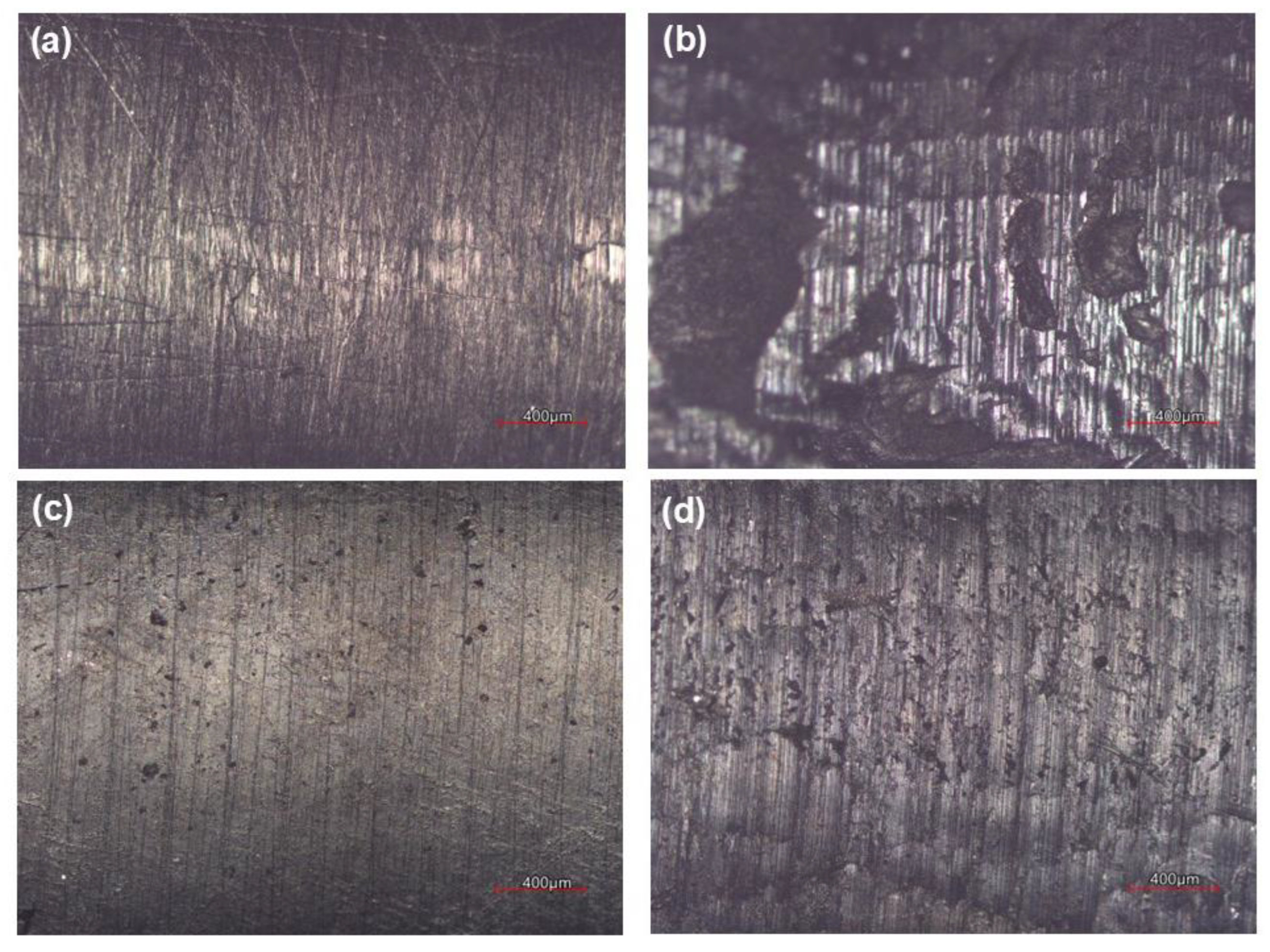

2.4.6. Dispersion, Morphology, and Fracture Surface Assessment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Curing Characteristics

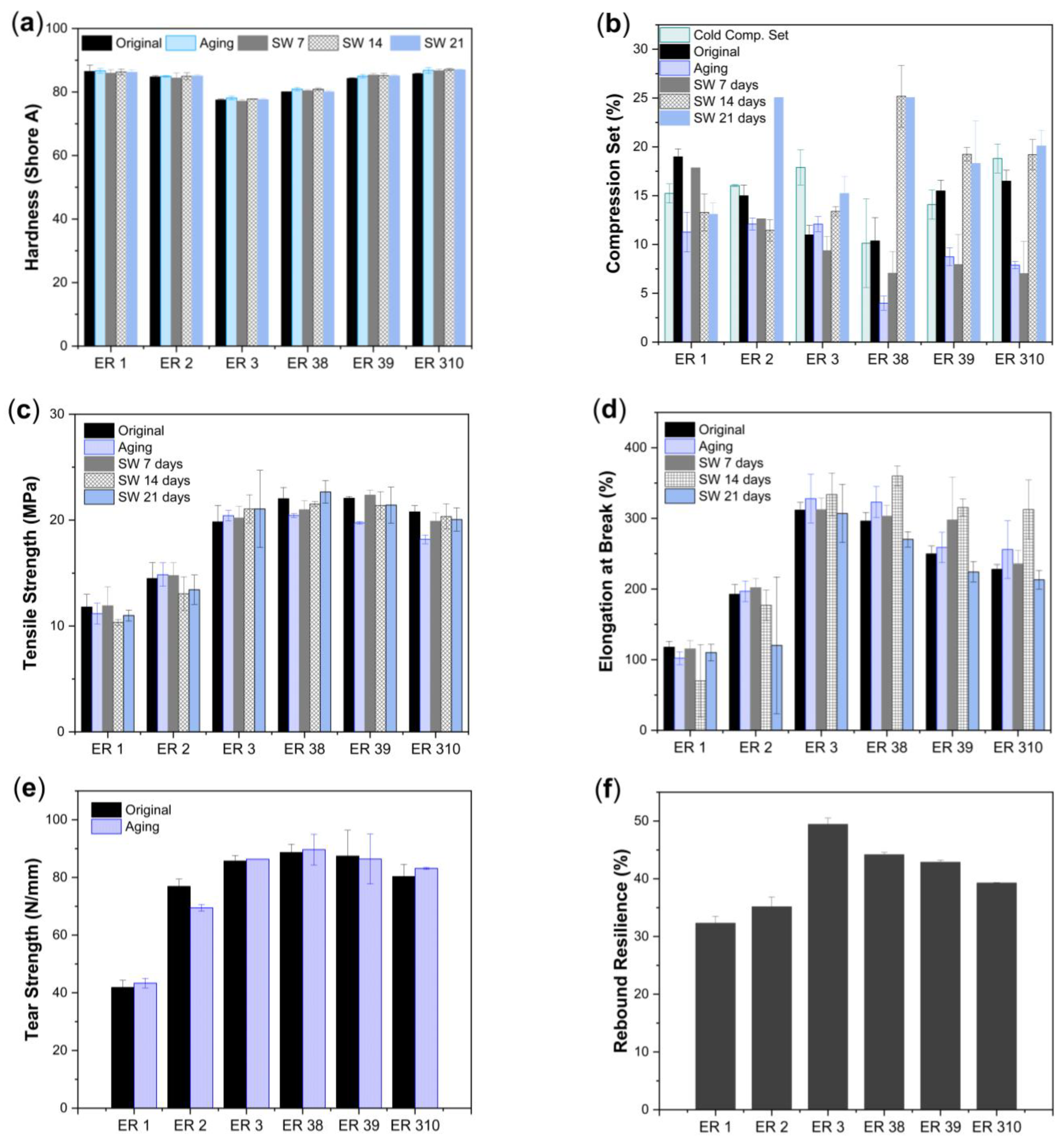

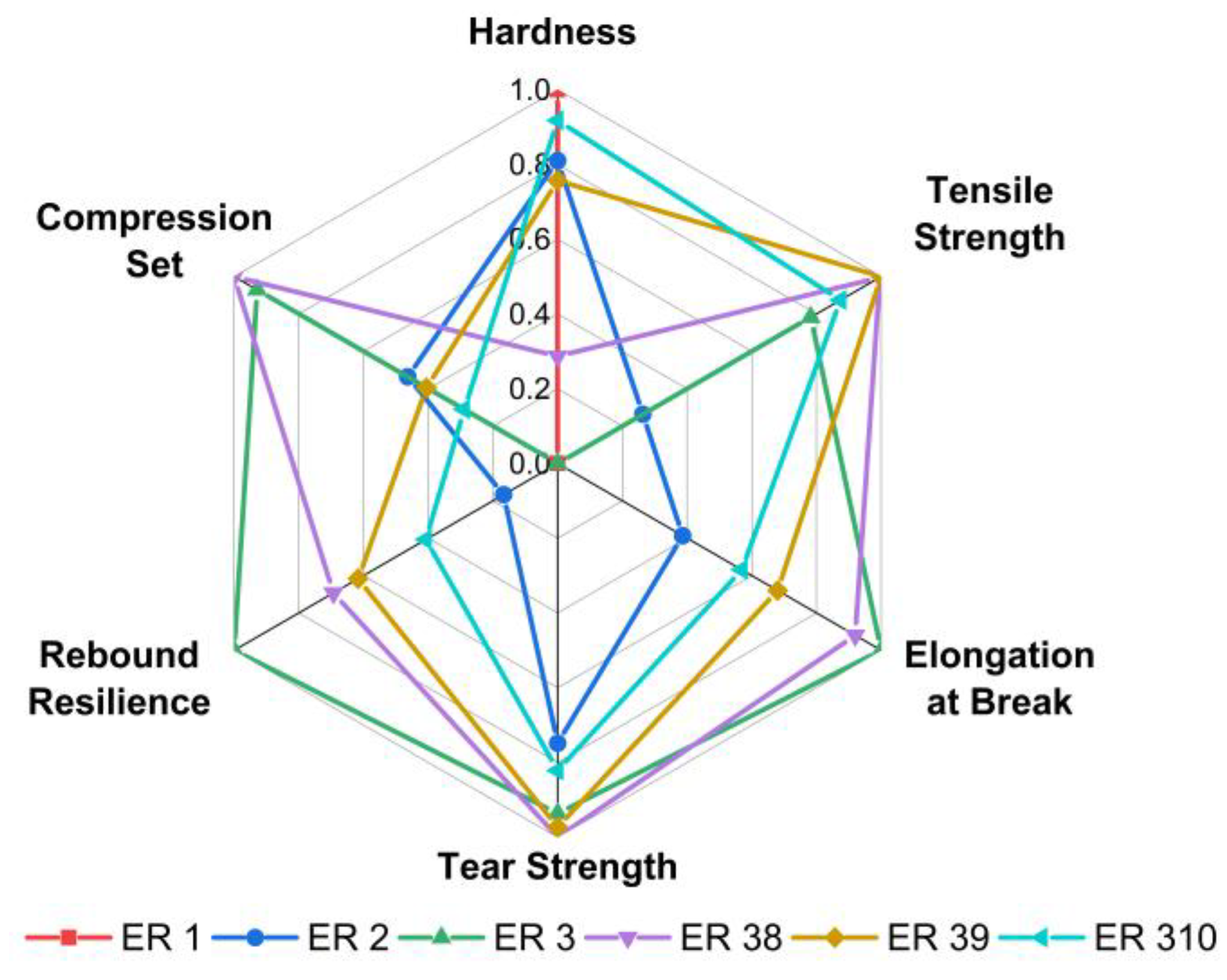

3.2. Mechanical Properties

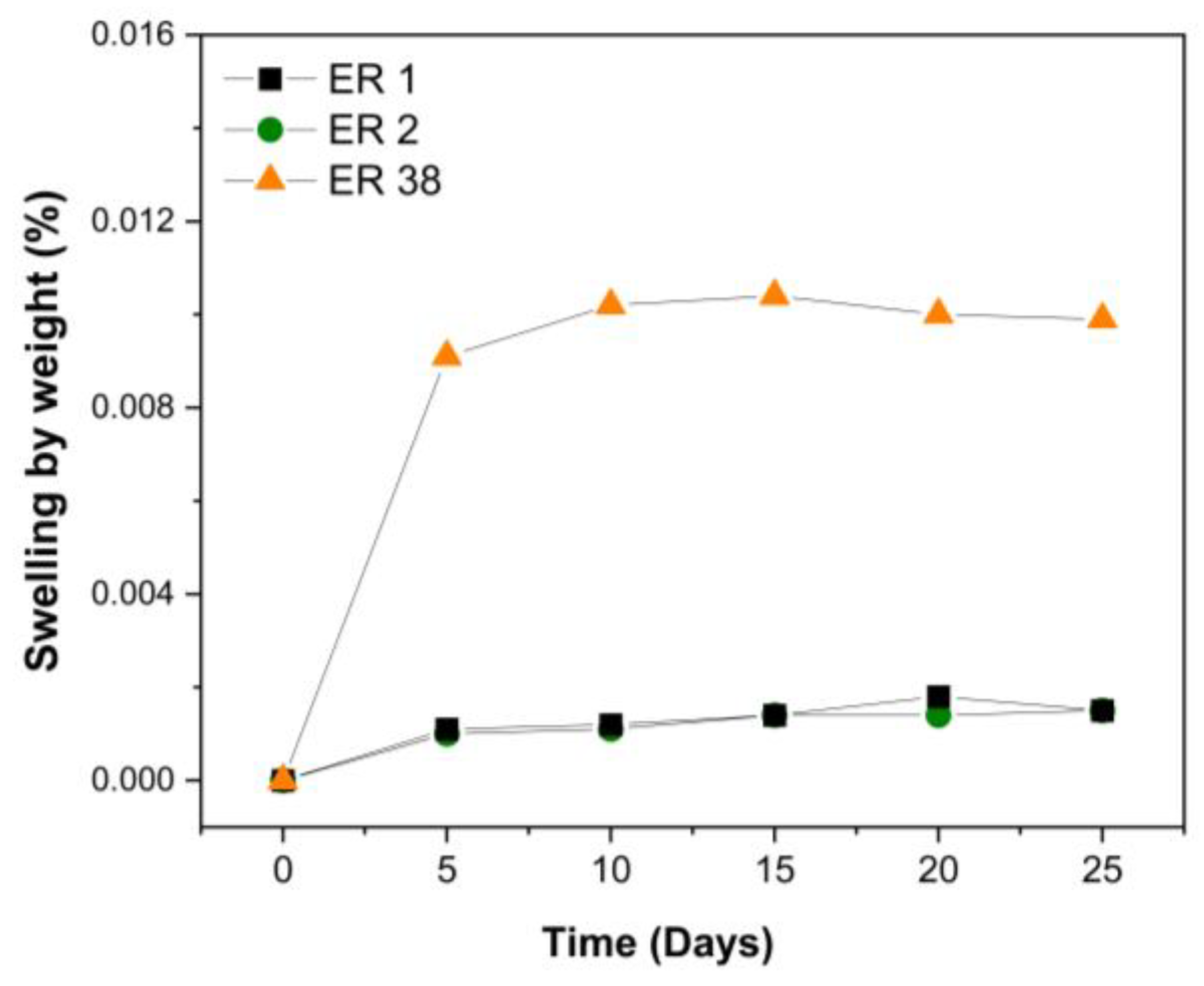

3.3. Swelling Behavior

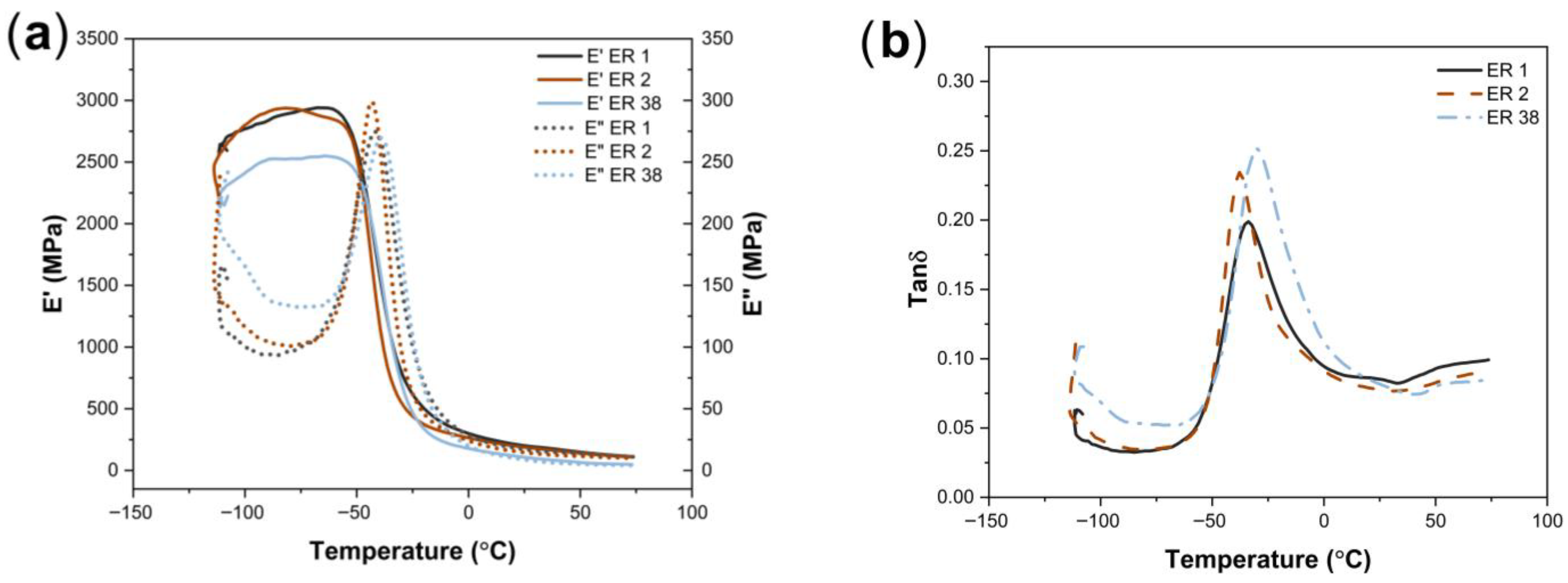

3.4. Dynamic Mechanical Properties

3.5. Thermal Properties

3.6. Dispersion, Morphology, and Fracture Surface Assessment

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPDM | Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer |

| ENB | 5-ethylene-2-norbornene |

| CBT | Cable-Based Tsunameter |

| OBU | Ocean Bottom Unit |

References

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, P.; Duan, M.; Yang, X.; Shi, W.; An, C.; Li, Z. Investigation on structural behavior of ring-stiffened composite offshore rubber hose under internal pressure. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 79, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchalla, S.T.; Gac, P.Y.L.; Maurin, R.; Créac’hcadec, R. Polychloroprene behaviour in a marine environment: Role of silica fillers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 139, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xue, L.; An, Y.; Liu, J. Vibration isolation characteristics of a rubber isolator in the deep water condition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2707, 012114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soehadi, G.; Setianingrum, L.; Rahardjo, S.; Yogantara, I.W.W.; Purnomo, E.; Purwoadi, M.A.; Santoso, I. Technology content assessment for Indonesia-cable based tsunameter development strategy using technometrics model. J. Sist. Manaj. Ind. 2023, 7, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, B.; Ivano, O.; Setyawan, A.; Perkasa, M. Rancang Bangun Dummy Canister Sistem Pendeteksi Tsunami Tipe CBT (Cable-Based Tsunameter) untuk Kedalaman Laut 3000 M. J. Tek. Mesin Cakram 2022, 5, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.-J.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Yang, C.-J.; Zhi, H. Active temperature-preserving deep-sea water sampler configured with a pressure-adaptive thermoelectric cooler module. Deep Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2022, 181, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, C. Rubbers Mostly Used in Process Equipment Lining. In Anticorrosive Rubber Lining; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Wang, L. The Effect of Cross-Linking Type on EPDM Elastomer Dynamics and Mechanical Properties: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Polymers 2022, 14, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.; Brull, R.; MAcko, T.; Arndt, J.-H.; Bernardo, R.; Niessen, S. Characterization of ethylene-propylene-diene terpolymers using high-temperature size exclusion chromatography coupled with an ultraviolet detector. Polymer 2022, 242, 124585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. Data on specific polymers. In Handbook of Material Weathering, 6th ed.; Chemtec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 369–590. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X.; Wang, C.-C.; Shi, Y.; Liu, L.-Z.; BAi, N.; Song, L.-F. Effects of Dynamic Crosslinking on Crystallization, Structure and Mechanical Property of Ethylene-Octene Elastomer/EPDM Blends. Polymers 2021, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perejón, A.; Jimenez, P.E.S.; Gonzales, E.G.; Maqueda, L.A.P.; Criado, J.M. Pyrolysis kinetics of ethylene–propylene (EPM) and ethylene–propylene–diene (EPDM). Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2013, 98, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.F.; Bai, N.; Shi, Y.; WAng, Y.-X.; Song, L.-X.; Liu, L.-Z. Effects of Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomers (EPDMs) with Different Moony Viscosity on Crystallization Behavior, Structure, and Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Vulcanizates (TPVs). Polymers 2023, 15, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, C.M.L.; Hiranobe, C.T.; Santos, R.J.; Cabrera, F.C.; Job, A.A. Effect of sulfur donor and co-agent as scorch delay system over third monomer EPDM-ENB content. J. Rubber Res. 2021, 24, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-N.; Shen, S.-L.; Zhou, A.-N.; Xu, Y.-S. Experimental Evaluation of Aging Characteristics of EPDM as a Sealant for Undersea Shield Tunnels. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D 2240-15; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property—Durometer Hardness. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D 412a-16; Standard Test Methods for Vulcanized Rubber and Thermoplastic Elastomers—Tension. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM D 624-00; Standard Test Method for Tear Strength of Conventional Vulcanized Rubber and Thermoplastic Elastomers. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D 395-16; Standard Test Methods for Rubber Property—Compression Set, ASTM International. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM D 6370-99; Standard Test Method for Rubber—Compositional Analysis by Thermogravimetry (TGA). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Kruzelak, J.; Dzuganova, M.; Kvasnicakova, A.; Preto, J.; Hronkovic, J.; Hudec, I. Influence of Plasticizers on Cross-Linking Process, Morphology, and Properties of Lignosulfonate-Filled Rubber Compounds. Polymers 2025, 17, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechurai, W.; Chiangta, W.; Tharuen, P. Effect of Vegetable Oils as Processing Aids in SBR Compounds. Macromol. Symp. 2015, 354, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguedad, D.; Mekhaldo, A.; Jbara, O.; Hadjadj, A.; Douglade, J.; Dony, P. Physico-chemical study of thermally aged EPDM used in power cables insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2015, 22, 3207–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kömmling, A.; Jaunich, M.; Wolff, D. Revealing effects of chain scission during ageing of EPDM rubber using relaxation and recovery experiment. Polym. Test. 2016, 56, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisojodharmo, L.A.; Amry, A.; Taqwatomo, G.; Fidyaningsih, R.; Arti, D.K.; Utami, W.T.; Saputra, D.A.; Gumelar, M.D.; Husin, S.; Susanto, H.; et al. Influence of NR/EPDM Ratios on the Performance of Pneumatic Fenders in Seawater. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 503, 06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akulichev, A.G.; Alcock, B.; Echtermeyer, A.T. Elastic recovery after compression in HNBR at low and moderate temperatures: Experiment and modelling. Polym. Test. 2017, 61, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, M.; Kömmling, A.; Jaunich, M.; Wolff, D. Understanding the recovery behaviour and the degradative processes of EPDM during ageing. Polym. Test. 2023, 121, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, B.F.; Mendoza, P.C.; Ortiz, C.J.C.; Ramos, V.L.F. Effect of the ethylene content on the properties m-propylene/EPDM blends. Polym. Sci. 2017, 1, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, A.P.; Santos, H.F.D.; Ribeiro, G.D.; Hiranobe, G.T.; Goveia, D.; Gennaro, E.M.; Paim, L.L.; Santos, R.J.D. Sustainable Composites: Analysis of Filler-Rubber Interaction in Natural Rubber-Styrene-Butadiene Rubber/Polyurethane Composites Using the Lorenz-Park Method and Scanning Electron Microscopy. Polymers 2024, 16, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Seyger, R.; Dierkes, W.K.; Bielinski, D.; Noordermeer, J.W.M. Swelling of EPDM rubbers for oil-well applications as influenced by medium composition and temperature Part I. Literature and theoretical background. Elastomery 2016, 20, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.; Kim, A.S. Temperature Effect on Forward Osmosis; InTech: London, UK, 2018; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, M.; Qamar, S.Z.; Mehdi, S.M.; Hussain, A. Diffusion-based swelling in elastomers under low- and high-salinity brine. J. Elastomers Plast. 2018, 51, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisang, W.; Supap, T.; Idem, R.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Study of Physical and Chemical Resistance of Elastomers in Aqueous MEA and MEA+CO2 Solutions during the Carbon Dioxide Absorption Process. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, C. The link between swelling ratios and physical properties of EPDM rubber compound having different oil amounts. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.R.; Borges, L.A.; Costa, M.F.; Soares, B.G.; Castello, D.A. Comparisons of complex modulus provided by different DMA. Polym. Test. 2018, 72, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.A. Use of Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) for Characterizing Interfacial Interactions in Filled Polymers. Solids 2021, 2, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandzierz, K.; Reuvekamp, L.; Dryzek, J.; Dierkes, W.; Blume, A.; Bielinski, D. Influence of Network Structure on Glass Transition Temperature of Elastomers. Materials 2016, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokmen, S.; Osswald, K.; Reincke, K.; Ilisch, S. Influence of Treated Distillate Aromatic Extract (TDAE) Content and Addition Time on Rubber-Filler Interactions in Silica Filled SBR/BR Blends. Polymers 2021, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, N.; Kodal, M.; Ozkoc, G. Lab-Scale Twin-Screw Micro-Compounders as a New Rubber-Mixing Tool: ‘A Comparison on EPDM/Carbon Black and EPDM/Silica Composites’. Polymers 2021, 13, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, N.L.; Hiranobe, C.T.; Cardim, H.P.; Dognani, G.; Sanchez, J.C.; Carvalho, J.A.J.; Torres, G.B.; Paim, L.L.; Pinto, L.F.; Cardim, G.P.; et al. A Review of EPDM (Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer) Rubber-Based Nanocomposites: Properties and Progress. Polymers 2024, 16, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Ethylene Content (wt%) | ENB Content (wt%) | Oil Content (phr) | Mooney Viscosity ML (1 + 4) 125C (MU) | MWD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPDM 4869 | 64 | 8.7 | 100 | 52 | CLCB |

| EPDM 5467 | 58 | 4.5 | 75 | 48 | CLCB |

| EPDM 8570 | 70 | 5.0 | 80 | CLCB |

| Component | Amount (phr) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER 1 | ER 2 | ER 3 | ER 38 | ER 39 | ER 310 | |

| EPDM 4869 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EPDM 5467 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EPDM 8570 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Polyoctenamer | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Zinc oxide | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Stearic acid | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Carbon black | 80 | 80 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

| 6PPD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Processing oil | 2 | 2 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Sulfur | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| CBS | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Compound | S′max [dNm] | S′min [dNm] | ΔTorque (S′max − S′min) [dNm] | T90 [min] | TS2 [min] | Cure Rate Index (CRI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER 1 | 44.37 | 39.46 | 4.91 | 8.05 | 0.8 | 12.55 |

| ER 2 | 40.6 | 34.75 | 5.85 | 15.04 | 1.12 | 6.89 |

| ER 3 | 29.95 | 26.98 | 2.97 | 25.41 | 1.17 | 4.09 |

| ER 38 | 32.97 | 29.63 | 3.34 | 30.59 | 1.24 | 3.34 |

| ER 39 | 36.57 | 32.25 | 4.32 | 29.46 | 1.04 | 3.46 |

| ER 310 | 39.57 | 33.83 | 5.84 | 30.54 | 1.06 | 3.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fidyaningsih, R.; Arti, D.K.; Susanto, H.; Hidayat, A.S.; Anggaravidya, M.; Amry, A.; Mustika, T.; Efendi Harahap, M.; Haryanto, V.M.; Effendi, M.D. Performance of Rubber Seals for Cable-Based Tsunameter with Varying Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer and Filler Content. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120705

Fidyaningsih R, Arti DK, Susanto H, Hidayat AS, Anggaravidya M, Amry A, Mustika T, Efendi Harahap M, Haryanto VM, Effendi MD. Performance of Rubber Seals for Cable-Based Tsunameter with Varying Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer and Filler Content. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120705

Chicago/Turabian StyleFidyaningsih, Riastuti, Dewi Kusuma Arti, Herri Susanto, Ade Sholeh Hidayat, Mahendra Anggaravidya, Akhmad Amry, Tika Mustika, Muslim Efendi Harahap, Vian Marantha Haryanto, and Mochammad Dachyar Effendi. 2025. "Performance of Rubber Seals for Cable-Based Tsunameter with Varying Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer and Filler Content" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120705

APA StyleFidyaningsih, R., Arti, D. K., Susanto, H., Hidayat, A. S., Anggaravidya, M., Amry, A., Mustika, T., Efendi Harahap, M., Haryanto, V. M., & Effendi, M. D. (2025). Performance of Rubber Seals for Cable-Based Tsunameter with Varying Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer and Filler Content. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120705