Interactive Influence of Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Recycled Steel Fibers on the Fresh and Hardened Performance of Eco-Efficient Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions

2.3. Casting and Testing Methods

2.3.1. Rheological Properties

2.3.2. Mechanical Properties

2.3.3. Density and Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Testing

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Fresh Properties of Recycled Self-Compacting Concrete

3.1.1. Slump Flow

3.1.2. The V-Funnel Flow

3.1.3. The L-Box Blocking Ratio (H2/H1)

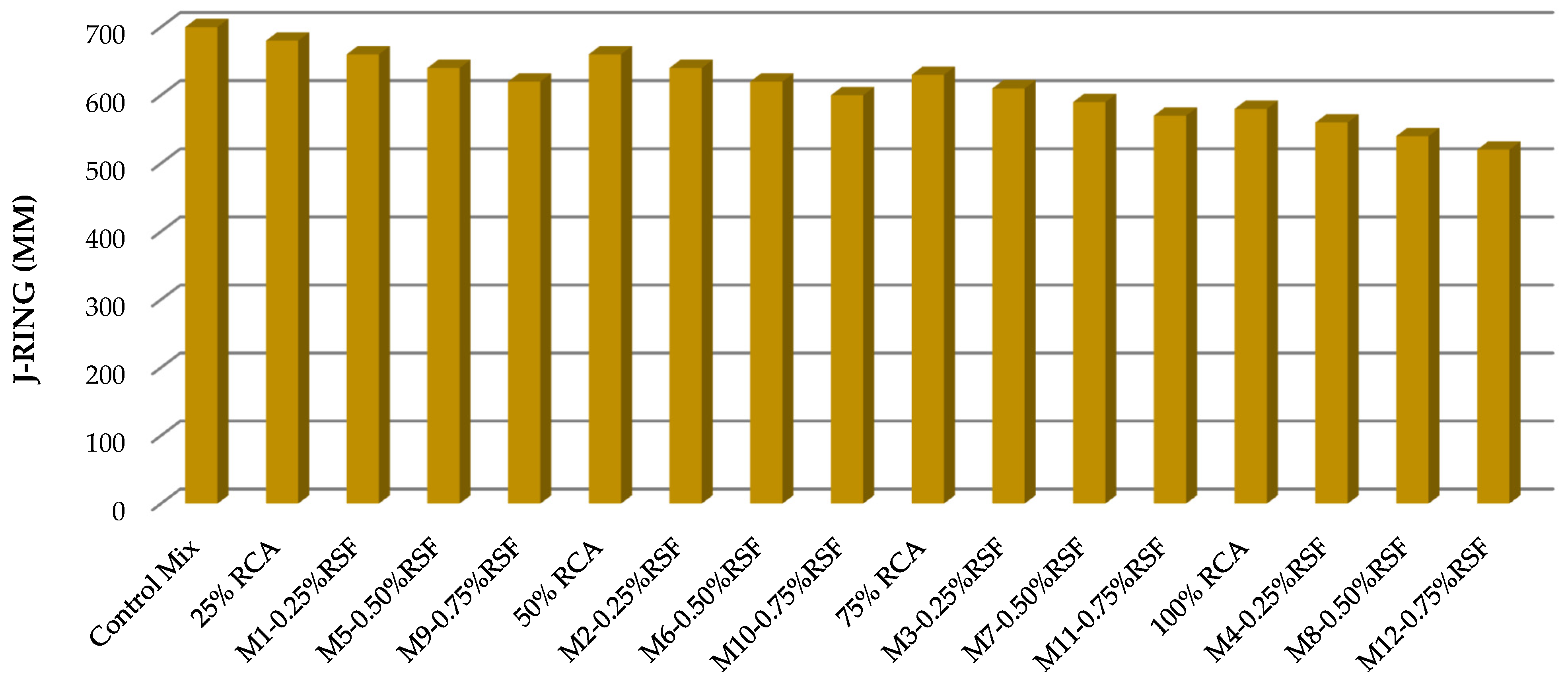

3.1.4. J-Ring Assessment

3.2. Mechanical Properties of the Recycled SCC Mixtures

3.2.1. Compressive Strength Development

3.2.2. Splitting Tensile Strength Behaviour of SCC Incorporating RCA and RSF

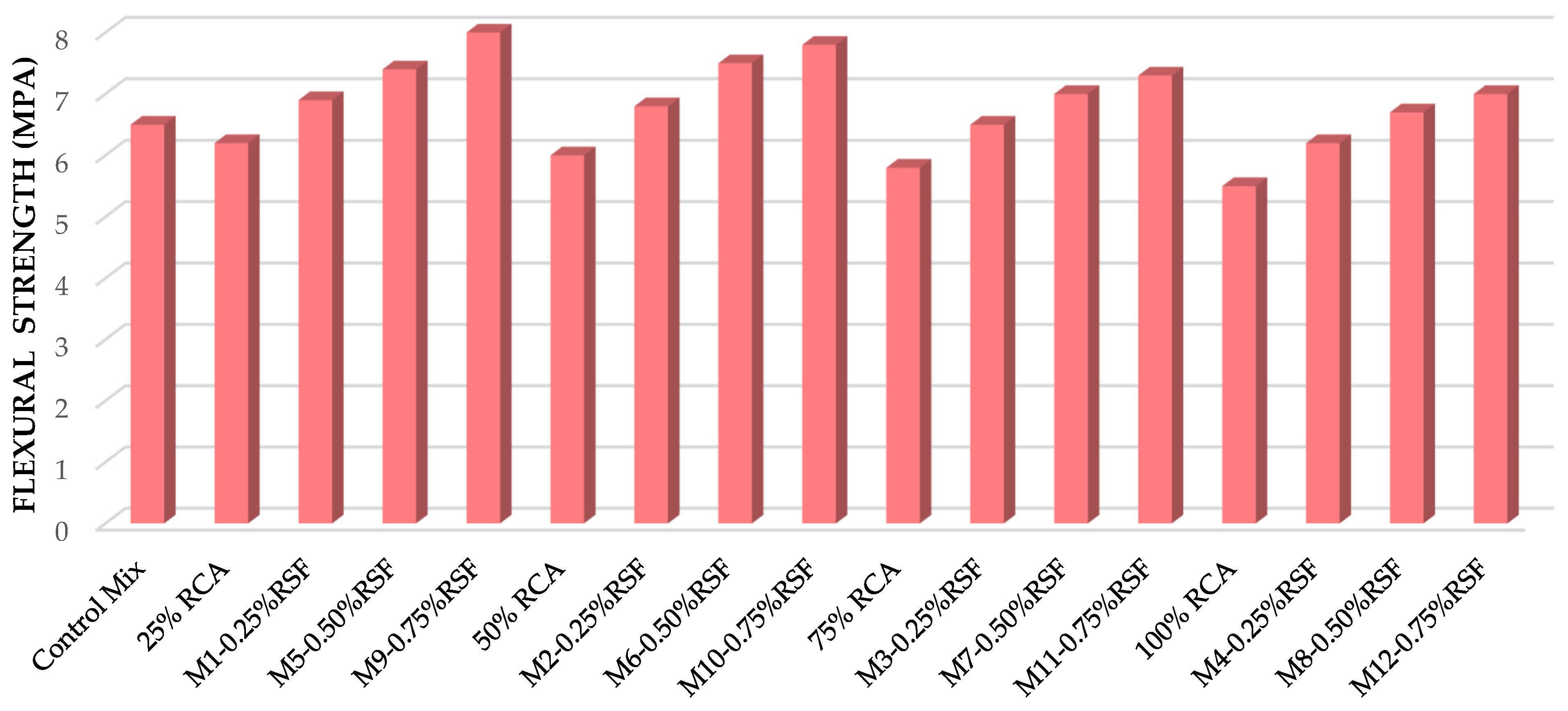

3.2.3. Flexural Strength Development of SCC Mixtures

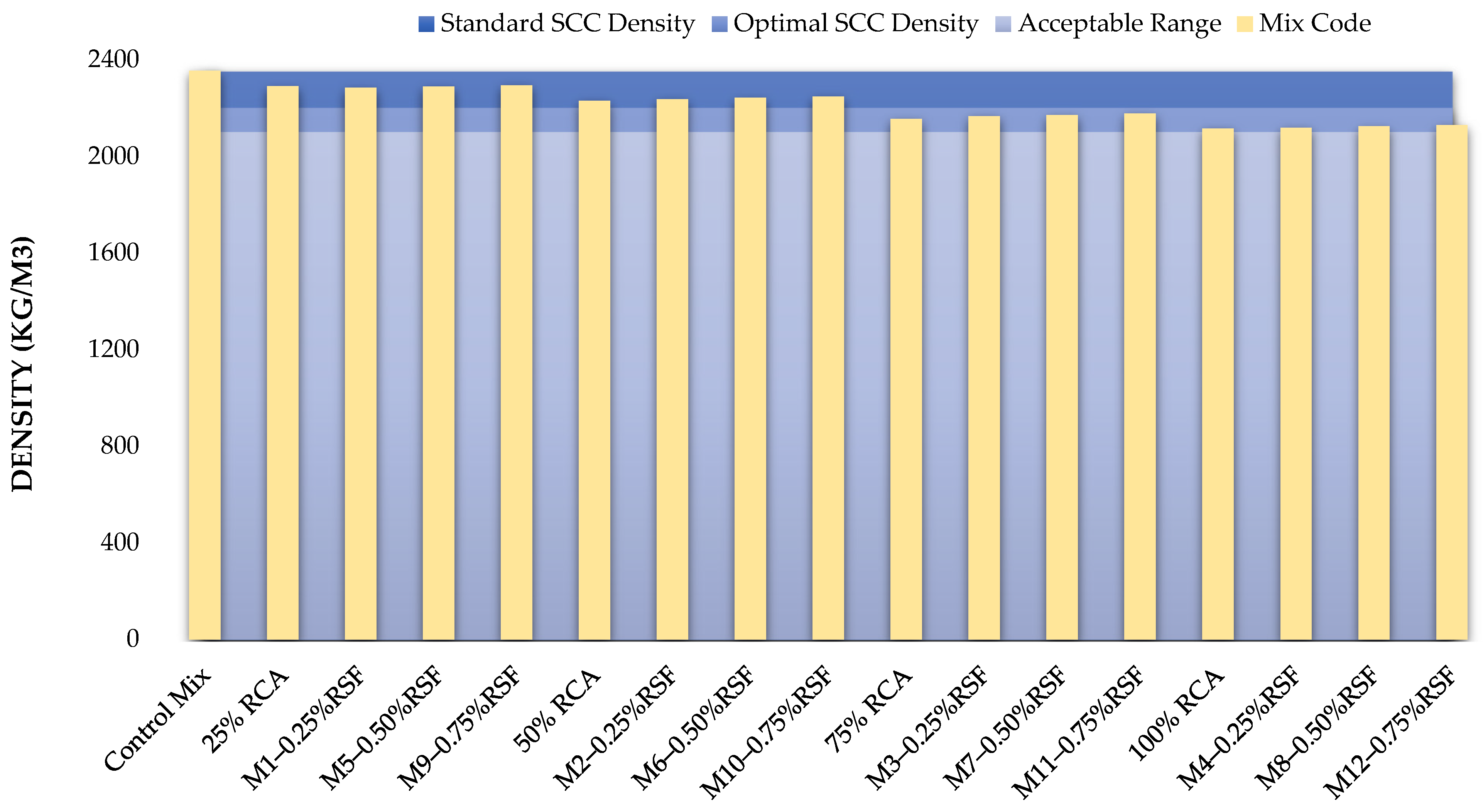

3.3. Density and Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) of Recycled SCC Mixtures

3.4. Correlation Between Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity and Mechanical Performance

4. Conclusions

- Rheological effect of RCA: Increasing RCA content systematically reduced workability: slump-flow decreased and T500, V-funnel, L-box, and J-ring values increased, due to the rougher texture, higher porosity, and greater water absorption of RCA.

- Rheological effect of RSF: RSF further decreased flowability by increasing mix viscosity and interparticle blocking, but all mixes remained within EFNARC [1] limits for filling and passing ability when admixture dosage was properly adjusted.

- Optimal fiber content for fresh performance: Very high fiber volume (0.75% RSF) noticeably impaired workability; an RSF range of about 0.25–0.50% offered the best compromise between self-compacting ability and strength enhancement.

- Compressive strength: Compressive strength declined with higher RCA replacement and, to a lesser extent, with increasing RSF, mainly because of higher matrix porosity and reduced compactability. Despite this reduction, all mixes achieved compressive strengths acceptable for the targeted C30/37.5 strength class.

- Splitting tensile and flexural strengths: RSF produced substantial gains in splitting tensile and flexural strengths across all RCA levels, with the highest values at 0.75% RSF, particularly for 25% RCA mixtures. The fibers improved crack-bridging and energy absorption, resulting in more ductile behaviour even when compressive strength was slightly reduced.

- Density and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV): Density and UPV decreased with increasing RCA content, reflecting the lighter, more porous nature of recycled aggregates and a more heterogeneous internal structure. RSF slightly increased both density and UPV at each RCA level, indicating improved matrix integrity and fewer internal defects.

- Selection criteria for the recommended mix window: To identify the recommended range of RCA and RSF contents, a two-stage screening approach was applied based on: (i) fresh-property compliance and (ii) mechanical-performance adequacy. For the fresh state, mixtures were required to satisfy the EFNARC [1] acceptance thresholds adopted in this study—slump flow, T500, V-funnel time, L-box blocking ratio, and J-ring response (Table 8)—together with stable self-compacting behaviour (i.e., proper flow and filling without visible segregation). For the hardened state, mixtures were considered mechanically acceptable when the 28-day compressive strength met the intended structural-grade target (C30/37.5 design objective), while maintaining or improving the tensile-related performance (splitting tensile and flexural strengths) relative to the corresponding fiber-free mixtures at the same RCA level, thereby ensuring a balanced structural response rather than strength gain in only one metric.

- Key quantitative highlights: In the fresh state, increasing RCA and RSF contents produced the expected reduction in workability (lower slump-flow and higher T500 and V-funnel times), while the majority of mixtures retained satisfactory self-compacting behaviour in accordance with EFNARC-based performance criteria. In the hardened state, compressive strength decreased with RCA replacement (and to a lesser extent with increasing RSF), with an RCA-induced maximum reduction of ≈39% at 100% RCA relative to the control mixture. In contrast, RSF markedly enhanced tensile-related performance: at 25% RCA, 0.75% RSF increased splitting tensile and flexural strengths by ≈41% and ≈29%, respectively, compared with the corresponding fiber-free mixture. RCA reduced density and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) by approximately 10–14%, and these reductions were partially mitigated by RSF addition, indicating improved matrix continuity and crack-bridging effects.

- Perspectives and future work: The present findings provide a performance-based basis for designing eco-efficient SCC with recycled constituents; however, several avenues merit further investigation. Future work should (i) quantify durability under aggressive exposure conditions (e.g., chloride ingress, carbonation, sulfate attack, and freeze–thaw cycling) and evaluate transport properties; (ii) address time-dependent behaviour (shrinkage, creep, and cracking propensity) in RCA–RSF systems; (iii) employ microstructural techniques (e.g., SEM/EDS and X-ray micro-CT) to elucidate the RCA–paste and RSF–matrix interfacial mechanisms underlying the observed macroscopic trends; (iv) examine robustness and field implementation issues including workability retention, pumpability, and fiber dispersion control at larger batching scales; and (v) integrate life-cycle assessment and multi-objective optimization to identify mixture domains that simultaneously maximize structural performance and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EFNARC. The European Guidelines for Self-Compacting Concrete: Specification, Production and Use; EFNARC: Farnham, UK, 2005; Available online: http://www.efnarc.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Younis, K.H. Mechanical Performance of Concrete Reinforced with Steel Fibres Extracted from Post-Consumer Tyres. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEC 2016, Erbil, Iraq, 20–22 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, K.H.; Ahmed, F.S.; Najim, K.B. Self-Compacting Concrete Reinforced with Steel Fibers from Scrap Tires: Rheological and Mechanical Properties. Eurasian J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, G.H.; Taha, M.R.; Hameed, A.M. Effect of Recycled Aggregate Concrete and Steel Fibers on the Fresh Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 377, 02012. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.M.; Saafan, M.; Etman, Z.; Abd-Elbaki, M.A. Effect of Steel Fibers on the Properties of Recycled Self-Compacting Concrete in Fresh and Hardened State. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 13, 400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Balea, A.; Fuente, E.; Monte, M.C.; Blanco, A.; Negro, C. Recycled Fibers for Sustainable Hybrid Fiber Cement-Based Material: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabduljabbar, H.; Alyousef, R.; Alrshoudi, F.; Alaskar, A.; Fathi, A.; Mustafa Mohamed, A. Mechanical effect of steel fiber on the cement replacement materials of self-compacting concrete. Fibers 2019, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, F.; Hou, L.; Nejadi, S.; Sun, J.; Abbasi, S. Experimental analysis of fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete using waste recycled concrete aggregates, polypropylene, and steel fibers. Struct. Concr. 2019, 20, 1670–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.N.; Tang, K. Environment-Friendly Recycled Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128495. [Google Scholar]

- Hatungimana, D.; Mardani, A.; Mardani, N.; Assaad, J. Feasibility of Steel Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete Containing Recycled Aggregates—Compliance to EFNARC Guidelines. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4888511 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Grdić, Z.J.; Topličić-Ćurčić, G.A.; Despotović, I.M.; Ristić, N.S. Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete Prepared with Coarse Recycled Concrete Aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, O.R.; Al-Mishhadani, S.A.; Abdul Razak, H. The Effect of Coarse Aggregate on Fresh and Hardened Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC). Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, K.; Roussel, Y. Testing and Performance of Fiber Reinforced, Self-Consolidating Concrete. Mater. Struct. 2000, 33, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhonde, H.B.; Mo, Y.; Hsu, T.T.C.; Vogel, J. Fresh and Hardened Properties of Self-Consolidating Fiber Reinforced Concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2007, 104, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Shi, N.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y. Research on working and mechanical properties of self-compacting steel-fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Hsu, K.-C.; Chai, H.-W. A Simple Mix Design Method for Self-Compacting Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna Rao, B.; Ravindra, V. Steel Fiber Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete Incorporating Class F Fly Ash. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 4936–4943. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C.X.; Stroeven, P. Development of Hybrid Polypropylene–Steel Fibers-Reinforced Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, N. The Effect of Steel Fibers Type and Content on the Development of Fresh and Hardened Properties and Durability of Self-Consolidating Concrete. Ph.D. Thesis, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Cananda, 2012. No. 794. [Google Scholar]

- Centonze, G.; Leone, M.; Aiello, A.M. Steel Fibers from Waste Tires as Reinforcement in Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, Y.V.; Parikh, K.B.; Raviya, T.H. A Critical Review of Self-Compacting Concrete Using Recycled Coarse Aggregate. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2016, 13, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ajith, V.; Mathew, P. A Study on the Self-Compacting Properties of Recycled Concrete Incorporating a New Mix Proportioning Method. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2015, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pilakoutas, K.; Neocleous, K.; Tlemat, H. Reuse of Steel Fibres as Concrete Reinforcement. Eng. Sustain. 2004, 157, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Shui, Z.H.; Lam, L. Effect of Microstructure of ITZ on Compressive Strength of Concrete Prepared with Recycled Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; El-Zohairy, A.; Eisa, A.S.; Mohamed, M.A.E.-A.B.; Abdo, A. Experimental Investigation of Self-Compacting Concrete with Recycled Concrete Aggregate. Buildings 2023, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, F.; AliBoucetta, T.; Behim, M.; Bellara, S.; Senouci, A.; Maherzi, W. Sustainable Self-Compacting Concrete with Recycled Aggregates, Ground Granulated Blast Slag, and Limestone Filler: A Technical and Environmental Assessment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessoum, M.; Boukhelf, F.; Khadraoui, F. Full Characterization of Self-Compacting Concrete Containing Recycled Aggregates and Limestone. Materials 2023, 16, 5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Rapallo, A.; Kuchta, K. Recycled Concrete Aggregate in Self-Consolidating Concrete: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Fresh and Hardened Performance. Recycling 2025, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wang, M.; Yao, D.; Yang, W. Study on Flexural Behavior of Self-Compacting Concrete Beams with Recycled Aggregates. Buildings 2022, 12, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadesh, P.; Juan-Valdés, A.; Guerra-Romero, M.I.; Morán-del Pozo, J.M.; García-González, J.; Martínez-García, R. Effect of Design Parameters on Compressive and Split Tensile Strength of Self-Compacting Concrete with Recycled Aggregate: An Overview. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, R.; Jagadesh, P.; Búrdalo-Salcedo, G.; Palencia, C.; Fernández-Raga, M.; Fraile-Fernández, F.J. Impact of Design Parameters on the Ratio of Compressive to Split Tensile Strength of Self-Compacting Concrete with Recycled Aggregate. Materials 2021, 14, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulkarim, A.; El-Sayed, A.K.; Alsaif, A.S.; Fares, G.; Alhozaimy, A.M. Behavior of Lightweight Self-Compacting Concrete with Recycled Tire Steel Fibers. Buildings 2024, 14, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, F.; Tajalizadeh, H.; Kheyroddin, A.; Naderpour, H. Bond Behavior of Recycled Tire Steel Fiber Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete with BFRP Bars after Seawater Exposure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Ali, M.; Ajwad, A.; Abbas, S.; Niazi, M.S.K.; Iqbal, M.; Akbar, A.; Khan, A.R. A Comprehensive Review of Incorporating Steel Fibers in Self-Compacting Concrete: Flexural and Rheological Characteristics. Materials 2022, 15, 7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, A.; Chyliński, F.; Bobrowicz, J.; Pichór, W. Effectiveness of Concrete Reinforcement with Recycled Tyre Steel Fibres. Materials 2022, 15, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemical Composition | OPC Type I (42.5 R) |

|---|---|

| CaO | 65.10% |

| SiO2 | 19.10% |

| Al2O3 | 4.20% |

| Fe2O3 | 2.70% |

| SO3 | 2.90% |

| MgO | 1.40% |

| Na2O | 0.65% |

| K2O | 0.98 |

| Physical Properties | OPC Type I (42.5 R) |

| Specific Gravity (g/m3) | 3.16 |

| Specific surface area (m2/kg) | 325.2 |

| Loss on ignition | 3.9% |

| Physical Properties | Coarse Aggregate | Fine Aggregate |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Gravity (g/m3) | 2.64 | 2.68 |

| Water Absorption % | 0.41 | 0.24 |

| Fineness Modulus | 6.4 | 2.75 |

| Physical Properties | Recycled Coarse Aggregate |

|---|---|

| Specific Gravity (g/m3) | 2.52 |

| Water Absorption % | 4.3 |

| Physical Properties | Recycled Steel Fiber |

|---|---|

| Diameter(mm) | 0.25–0.3 |

| Length(mm) | 20–35 |

| Specific Gravity (g/m3) | 7.85 |

| Tensile Strength (Mpa) | 1250 |

| Chemical Compositions and Physical Properties | Superplasticizer |

|---|---|

| Form | Liquid |

| Color | Light Yellow |

| Odor | Slight/Faint |

| Boiling Point (C) | >100 |

| Freezing point | −4 |

| Relative Density | 1.05–1.08 |

| Water Solubility | Soluble |

| Chemical Composition | Silica Fume |

|---|---|

| CaO | 1.50% |

| SiO2 | 95.10% |

| Al2O3 | 1.20% |

| Fe2O3 | 1% |

| SO3 | 0.12% |

| MgO | 0.9% |

| Na2O | 0.24% |

| K2O | 0.78 |

| Specific Gravity (g/m3) | 2.21 |

| Specific surface area (m2/kg) | 2.0 |

| Loss on ignition | 1.5% |

| Mix Code | Cement kg/m3 | Fine Aggregate (Sand) kg/m3 | Coarse Aggregate (Gravel) kg/m3 | Recycled Coarse Aggregate kg/m3 | Recycled Steel Fiber kg/m3 | Silica Fume kg/m3 | Water Liter/m3 | Admixture (SP) Liter/m3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM | 350 | 925 | 850 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 180 | 12 | |

| R25 | M1 | 350 | 925 | 638 | 212 | 19 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R50 | M2 | 350 | 925 | 425 | 425 | 19 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R75 | M3 | 350 | 925 | 212 | 638 | 19 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R100 | M4 | 350 | 925 | 0 | 850 | 19 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R25 | M5 | 350 | 925 | 638 | 212 | 39 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R50 | M6 | 350 | 925 | 425 | 425 | 39 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R75 | M7 | 350 | 925 | 212 | 638 | 39 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R100 | M8 | 350 | 925 | 0 | 850 | 39 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R25 | M9 | 350 | 925 | 638 | 212 | 59 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R50 | M10 | 350 | 925 | 425 | 425 | 59 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R75 | M11 | 350 | 925 | 212 | 638 | 59 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| R100 | M12 | 350 | 925 | 0 | 850 | 59 | 10 | 180 | 12 |

| Mix Code | RCA Content (%) | RSF Content (%) | Slump Flow (mm) | Slump T500 (s) | V-Funnel (s) | L-Box (H2/H1) | J-Ring (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Mix | 0% | 0% | 780 ± 12 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 700 ± 15 |

| 25% | 0% | 700 ± 15 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 680 ± 14 | |

| M1 | 0.25% | 680 ± 18 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 660 ± 16 | |

| M5 | 0.5% | 660 ± 20 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 640 ± 18 | |

| M9 | 0.75% | 640 ± 22 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 620 ± 20 | |

| 50% | 0% | 680 ± 17 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 660 ± 16 | |

| M2 | 0.25% | 660 ± 19 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 640 ± 18 | |

| M6 | 0.5% | 640 ± 21 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 620 ± 19 | |

| M10 | 0.75% | 620 ± 23 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 600 ± 21 | |

| 75% | 0% | 650 ± 18 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.4 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 630 ± 17 | |

| M3 | 0.25% | 630 ± 20 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 610 ± 18 | |

| M7 | 0.5% | 610 ± 22 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 590 ± 20 | |

| M11 | 0.75% | 780 ± 12 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 700 ± 15 | |

| 100% | 0% | 700 ± 15 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 680 ± 14 | |

| M4 | 0.25% | 680 ± 18 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 660 ± 16 | |

| M8 | 0.5% | 660 ± 20 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 640 ± 18 | |

| M12 | 0.75% | 640 ± 22 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 620 ± 20 | |

| EFNARK Limits | 650–800 | 2–6 | 8–12 | 0.8–1.0 | 650–800 |

| Mix Code | RCA Content (%) | RSF Content (%) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Splitting Tensile Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Mix | 0% | 0% | 44.2 | 3.4 | 6.5 |

| 25% | 0% | 41.4 | 3.2 | 6.2 | |

| M1 | 0.25% | 42.1 | 3.7 | 6.9 | |

| M5 | 0.50% | 40.2 | 4.1 | 7.4 | |

| M9 | 0.75% | 38.0 | 4.5 | 8.0 | |

| 50% | 0% | 35.6 | 3.0 | 6.0 | |

| M2 | 0.25% | 36.5 | 3.5 | 6.8 | |

| M6 | 0.50% | 32.0 | 4.0 | 7.5 | |

| M10 | 0.75% | 30.5 | 4.3 | 7.8 | |

| 75% | 0% | 30.0 | 2.8 | 5.8 | |

| M3 | 0.25% | 29.5 | 3.3 | 6.5 | |

| M7 | 0.50% | 27.0 | 3.7 | 7.0 | |

| M11 | 0.75% | 25.5 | 4.0 | 7.3 | |

| 100% | 0% | 27.0 | 2.5 | 5.5 | |

| M4 | 0.25% | 24.5 | 3.0 | 6.2 | |

| M8 | 0.50% | 23.0 | 3.4 | 6.7 | |

| M12 | 0.75% | 22.5 | 3.7 | 7.0 |

| Mix Code | RCA Content (%) | RSF Content (%) | Density (Kg/m3) | Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity UPV (km/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Mix | 0% | 0% | 2355 | 4.3 |

| 25% | 0% | 2290.4 | 4.1 | |

| M1 | 0.25% | 2284.5 | 4.2 | |

| M5 | 0.50% | 2289.2 | 4.25 | |

| M9 | 0.75% | 2294.8 | 4.3 | |

| 50% | 0% | 2230.5 | 4.0 | |

| M2 | 0.25% | 2237.2 | 4.05 | |

| M6 | 0.50% | 2242.7 | 4.1 | |

| M10 | 0.75% | 2247.4 | 4.15 | |

| 75% | 0% | 2155.5 | 3.85 | |

| M3 | 0.25% | 2166.9 | 3.9 | |

| M7 | 0.50% | 2171.3 | 3.95 | |

| M11 | 0.75% | 2176.8 | 4 | |

| 100% | 0% | 2115.8 | 3.7 | |

| M4 | 0.25% | 2119.1 | 3.75 | |

| M8 | 0.50% | 2124.5 | 3.8 | |

| M12 | 0.75% | 2129.6 | 3.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdul-Rahman, A.R.; Younis, K.H.; Taha, B.O. Interactive Influence of Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Recycled Steel Fibers on the Fresh and Hardened Performance of Eco-Efficient Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010009

Abdul-Rahman AR, Younis KH, Taha BO. Interactive Influence of Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Recycled Steel Fibers on the Fresh and Hardened Performance of Eco-Efficient Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdul-Rahman, Ahmed Redha, Khaleel Hasan Younis, and Bahman Omar Taha. 2026. "Interactive Influence of Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Recycled Steel Fibers on the Fresh and Hardened Performance of Eco-Efficient Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010009

APA StyleAbdul-Rahman, A. R., Younis, K. H., & Taha, B. O. (2026). Interactive Influence of Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Recycled Steel Fibers on the Fresh and Hardened Performance of Eco-Efficient Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010009