Pupillometry as an Objective Measure of Auditory Perception and Listening Effort Across the Lifespan: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

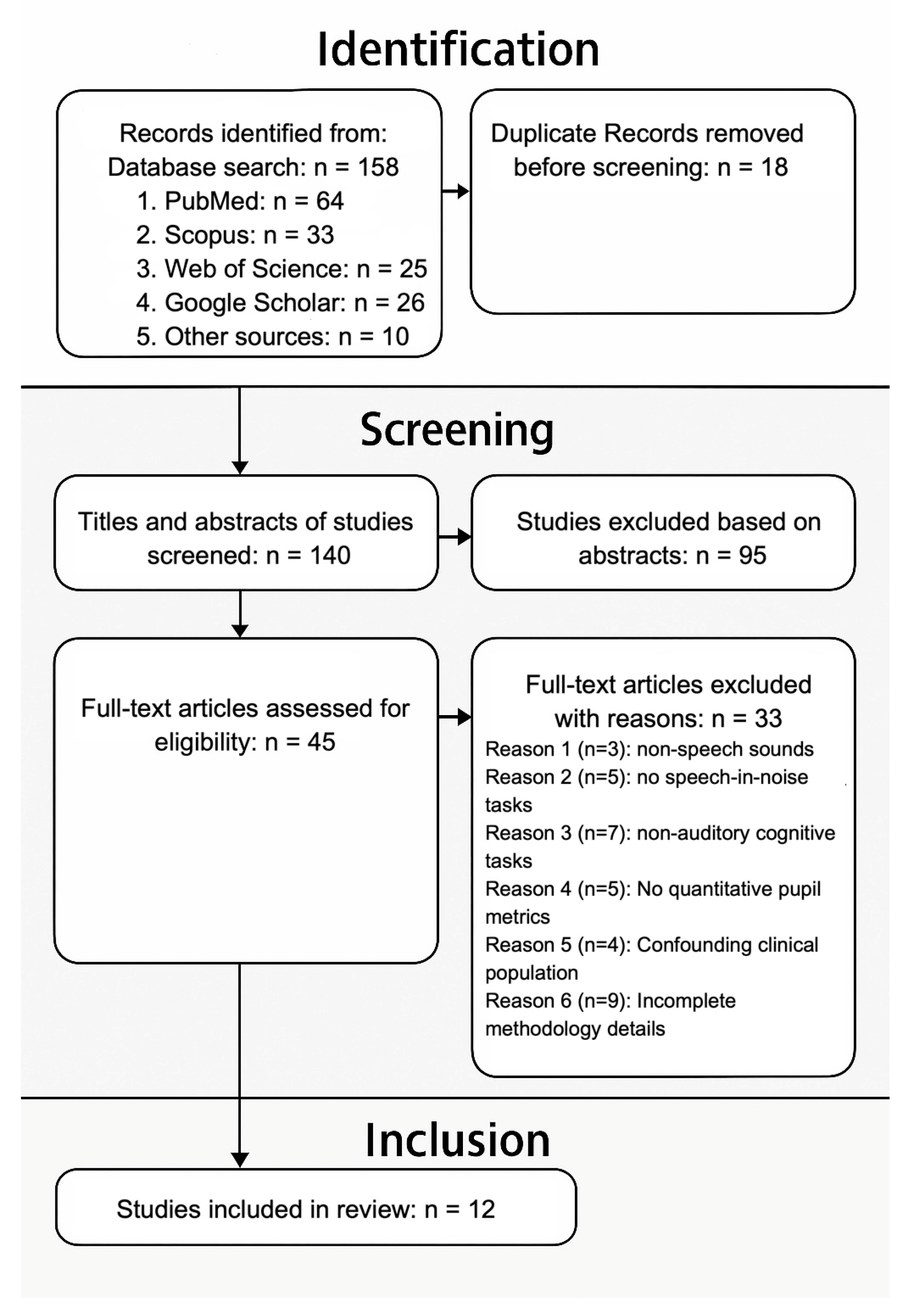

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Use pupillometry as a primary measure of auditory processing or listening effort.

- Involve human participants (pediatric or adult) with normal hearing or hearing impairment.

- Be published in English in peer-reviewed journals.

- Provide empirical data (e.g., pupil dilation metrics) related to auditory tasks.

- Focused solely on visual stimuli or non-speech sounds (e.g., tone pips, music).

- Did not involve speech-in-noise paradigms (e.g., quiet listening tasks).

- Used pupillometry for cognitive tasks unrelated to auditory effort (e.g., working memory, decision making unrelated to listening).

- Reported only qualitative pupil changes without quantitative analysis (e.g., no baseline-corrected pupil metrics).

- Examined clinical populations (e.g., dementia, stroke) where pupil response might reflect broader cognitive deficits rather than listening effort specifically.

- Did not provide clear methodological details necessary for reproducibility (e.g., missing noise type, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) level, pupil analysis window).

2.3. Study Selection and Screening Process

2.4. Level of Evidence Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Studies

3.2. Pupillometry in Pediatric Populations

3.3. Pupillometry in Adult Populations

3.4. Pupillometry in Specialized Populations

3.5. Methodological Considerations

3.6. Findings: Thematic Synthesis of Evidence

3.6.1. Listening Effort and Pupil Dilation

3.6.2. Influence of Hearing Status on Listening Effort

3.6.3. Impact of Auditory Scene Complexity

3.6.4. Influence of Technology

3.6.5. Lexical and Semantic Effects on Cognitive Load

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Research Implications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAHS | bone-anchored hearing systems |

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| MPD | Mean Pupil Dilation |

| NH | Normal-Hearing |

| NR | Noise Reduction |

| PPD | Peak Pupil Dilation |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SRT | Speech Reception Threshold |

| SSD | Single-Sided Deafness |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Hearing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Lin, F.R.; Metter, E.J.; O’Brien, R.J.; Resnick, S.M.; Zonderman, A.B.; Ferrucci, L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, G.A.; Mills, J.H. Presbycusis. Lancet 2005, 366, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichora-Fuller, M.K.; Kramer, S.E.; Eckert, M.A.; Edwards, B.; Hornsby, B.W.Y.; Humes, L.E.; Lemke, U.; Lunner, T.; Matthen, M.; Mackersie, C.L.; et al. Hearing impairment and cognitive energy: The framework for understanding effortful listening (FUEL). Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 5S–27S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornsby, B.W.Y. The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands. Ear Hear. 2013, 34, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Beatty, J. Pupil diameter and load on memory. Science 1966, 154, 1583–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekveld, A.A.; Kramer, S.E.; Festen, J.M. Pupil response as an indication of effortful listening: The influence of sentence intelligibility. Ear Hear. 2010, 31, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, J. Task-evoked pupillary responses, processing load, and the structure of processing resources. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 91, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granholm, E.; Steinhauer, S.R. Pupillometric measures of cognitive and emotional processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2004, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, M.B.; Wendt, D.; Koelewijn, T.; Kuchinsky, S.E. Best practices and advice for using pupillometry to measure listening effort: An introduction for those who want to get started. Trends Hear. 2018, 22, 2331216518800869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, J.P.; Besser, J.; Lemke, U. Behavioral assessment of listening effort using a dual-task paradigm: A review. Trends Hear. 2017, 21, 2331216516687287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhanbali, S.; Dawes, P.; Millman, R.E.; Munro, K.J. Measures of listening effort are multidimensional. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, K.; McMahon, C.; Boisvert, I.; Ibrahim, R.; de Lissa, P.; Graham, P.; Lyxell, B. Objective assessment of listening effort: Coregistration of pupillometry and EEG. Trends Hear. 2017, 21, 2331216517706396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendra, S.; Chun, H.; Lee, S.; Chen, F.; Martin, B.A.; Tan, C. Cross-frequency coupling in cortical processing of speech. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackersie, C.L.; Calderon-Moultrie, N. Autonomic nervous system reactivity during speech repetition tasks: Heart rate variability and skin conductance. Ear Hear. 2016, 37 (Suppl. S1), 118S–125S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelewijn, T.; Zekveld, A.A.; Festen, J.M.; Kramer, S.E. Pupil dilation uncovers extra listening effort in the presence of a single-talker masker. Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, D.; Hietkamp, R.K.; Lunner, T. Impact of noise and noise reduction on processing effort: A pupillometry study. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.Y.; Hoen, M.; Karoui, C.; Demarcy, T.; Ardoint, M.; Tuset, M.-P.; De Seta, D.; Sterkers, O.; Lahlou, G.; Mosnier, I. Pupillometry assessment of speech recognition and listening experience in adult cochlear implant patients. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 556675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Chou, R. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, M.M.; Papsin, B.C.; Gordon, K.A. Binaural fusion and listening effort in children who use bilateral cochlear implants: A psychoacoustic and pupillometric study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.A.; Calloway, R.; Karunathilake, I.D.; Decruy, L.P.; Anderson, S.; Simon, J.Z.; Kuchinsky, S.E. Attention mobilization as a modulator of listening effort: Evidence from pupillometry. Trends Hear. 2024, 28, 23312165241245240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.A.; Bidelman, G.M. Autonomic nervous system correlates of speech categorization revealed through pupillometry. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, I.; Ellis, G.M.; McNamara, B.; Lefler, J.; DeRoy Milvae, K.; Gordon-Salant, S.; Kuchinsky, S.E.; Brungart, D.S. Examining the feasibility of integrating pupillometry measures of listening effort into clinical audiology assessments. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 153 (Suppl. S3), A79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM). The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, University of Oxford. 2011. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Bianchi, F.; Wendt, D.; Wassard, C.; Maas, P.; Lunner, T.; Rosenbom, T.; Holmberg, M. Benefit of higher maximum force output on listening effort in bone-anchored hearing system users: A pupillometry study. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burg, E.A.; Thakkar, T.; Fields, T.; Misurelli, S.M.; Kuchinsky, S.E.; Roche, J.; Lee, D.J.; Litovsky, R.Y. Systematic comparison of trial exclusion criteria for pupillometry data analysis in individuals with single-sided deafness and normal hearing. Trends Hear. 2021, 25, 23312165211013256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlenforst, B.; Zekveld, A.A.; Lunner, T.; Wendt, D.; Naylor, G.; Wang, Y.; Kramer, S.E. Impact of stimulus-related factors and hearing impairment on listening effort as indicated by pupil dilation. Hear. Res. 2017, 351, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Population | Sample Size | Methodology | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Adults with normal hearing | 38 | Measured pupil dilation to Dutch sentences in stationary noise at three speech reception threshold (SRT) levels using adaptive procedures. Tasks performed unaided as participants had normal hearing. | Peak dilation amplitude, mean pupil size, and peak latency increased as SNR decreased, while baseline pupil diameter remained unaffected by noise level alone. | Limited to normal hearing subjects restricts its relevance to hearing-impaired or older populations with different pupil response patterns. |

| [16] | Adults with normal hearing | 48 | Pupil dilation was recorded as participants (young and middle-aged) performed a speech-in-noise task under varying masker types (stationary, fluctuating, single-talker) and intelligibility levels. Tasks performed unaided as participants had normal hearing. | Only the single-talker masker increased pupil dilation, with no difference between fluctuating and stationary noise, regardless of intelligibility or age. | Limited to normal hearing subjects restricts its relevance to hearing-impaired or older populations with different pupil response patterns. |

| [20] | Children with hearing impairment peers with normal hearing | 25 + 24 | Listening effort measured when children listens to acoustic click-trains/electric pulses. Children with bilateral CIs performed tasks with their CIs active (aided condition). Normal-hearing children performed tasks unaided. | Children with bilateral CIs showed increased listening effort, reflected in greater pupil dilation. | Task complexity may confound pupil responses; Stimulus simplicity limit generalizability to real-world listening. |

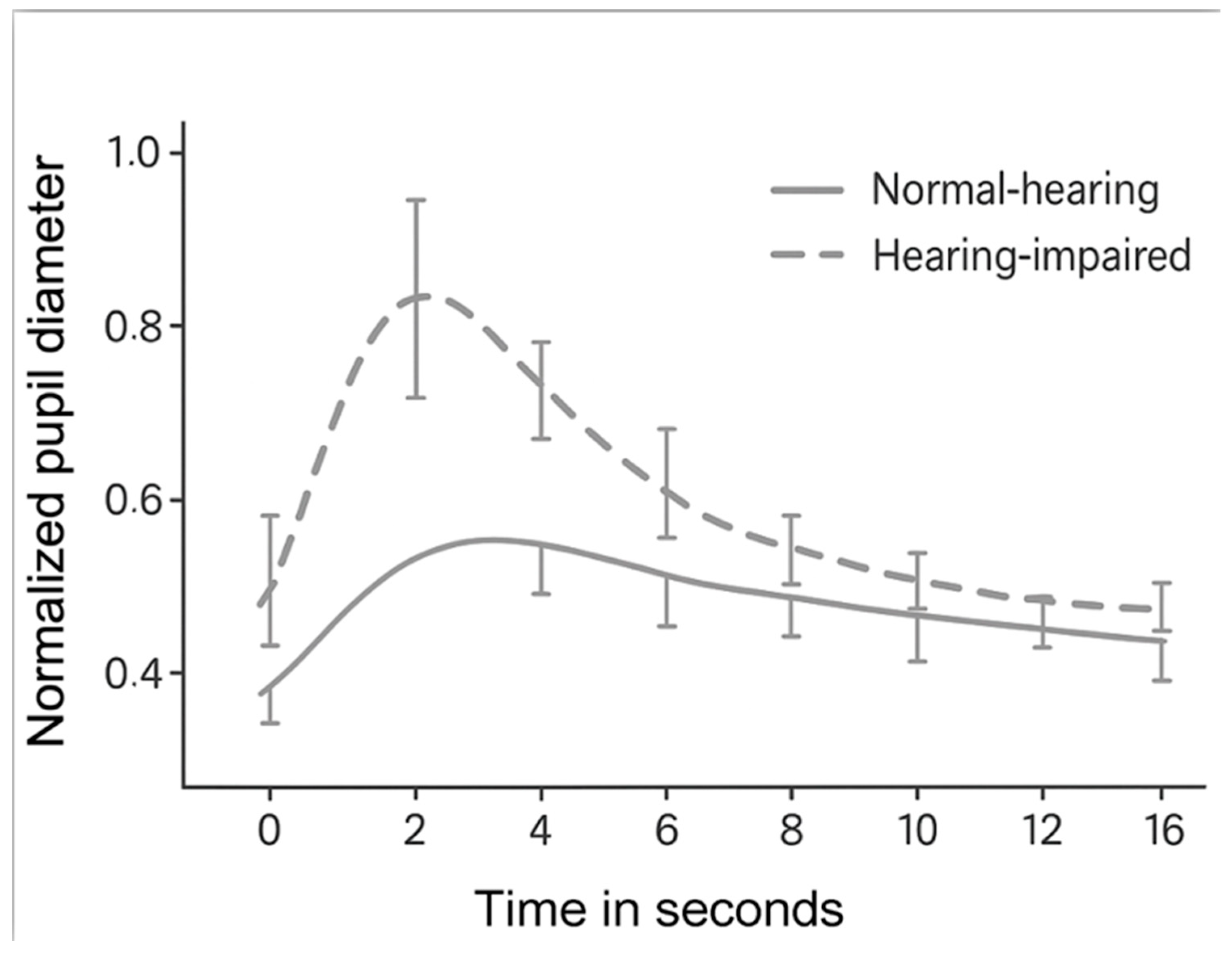

| [21] | Hearing-impaired and age-matched normal hearing participants | 25 + 32 | Pupil dilation measured when adults listened to sentences masked by stationary noise or a competing talker at varying SNRs. Hearing-impaired participants used their prescribed HA during tasks (aided condition). Normal-hearing participants performed tasks unaided. | Hearing-impaired listeners exert more effort, shown by greater pupil dilation, even when their speech understanding matches that of normal-hearing listeners. | Lab conditions and limited noise types reduce real-world generalizability. |

| [17] | Adults with hearing impairment | 24 | Peak pupil dilation measured in speech recognition tasks with varying noise levels. Participants used HA with noise reduction (NR) schemes enabled during tasks (aided condition). | Noise reduction (NR) schemes in HAs reduced listening effort, as reflected by smaller pupil dilation. | The study focused on specific NR schemes. |

| [10] | Young adults with normal hearing and adults with CIs | 40 + 10 | Pupil dilation measured in CI and normal-hearing adults listening to high- and low-context sentences followed by silence or distractors. CI users performed tasks with their CIs active (aided condition). Normal-hearing participants performed tasks unaided. | CI listeners had lower intelligibility scores than normal hearing listeners across all word types, and while context did not affect preceding words. | The controlled lab setting with specific distractors like digits may not fully capture the complexity of real-world listening environments, limiting the generalizability of the findings. |

| [22] | Adults with bone-anchored hearing systems (BAHS) | 21 | Listening effort measured across different sound processors in noise with pupil dilation. Participants used BAHS during tasks, comparing advanced processors to baseline processors (aided condition). | Advanced sound processors reduced pupil dilation compared to the baseline processor, indicating lower listening effort. | Small sample; specific to BAHS users, limiting generalizability. |

| [23] | Adults with normal hearing | 15 | Listening effort measured across different speech tokens with varying SNRs. Tasks performed unaided as participants had normal hearing. | Pupil responses showed greater effort and delayed timing for ambiguous speech in moderate noise, highlighting the role of categorical perception in resisting degradation. | Limited ecological validity due to the controlled lab setting. |

| [18] | Adults with CIs | 10 | Pupillometry used to measure pupil dilation during speech recognition tasks with sentences presented in varying noise levels. Participants used their CI during tasks (aided condition). | CI users with poorer speech perception showed larger pupil dilations, indicating higher cognitive effort during speech recognition. | The small sample size limits the generalizability of findings across diverse CI populations. |

| [24] | Adults with single-sided deafness (SSD) and participants with normal hearing | 9 + 20 | Pupil measures during participants listened to sentences in quiet or with speech maskers. SSD participants performed tasks unaided (no hearing devices specified). Normal-hearing participants performed tasks unaided. | Pupil dilation increased in speech masker conditions compared to quiet for both SSD and normal hearing groups. | Study’s findings may not generalize to individuals with other hearing loss types. |

| [25] | Younger adults with normal hearing | 46 | Pupil dilation measured during pure-tone audiometry, gaps-in-noise (GIN), dichotic digits, and speech-in-noise tasks. Tasks performed unaided as participants had normal hearing. | Task-evoked pupil responses increased with higher listening demands across tasks, showing sensitivity to differences in effort during clinically relevant audiologic tests | Limited to NH listeners |

| [26] | Adults with normal hearing | 19 | Pupil measures during speech-in-noise tasks. Tasks performed unaided as participants had normal hearing. | Greater pupil dilation occurred when listeners anticipated challenging listening conditions. | Baseline pupil size range may not fully reflect individual attentional states, affecting generalizability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raghavendra, S. Pupillometry as an Objective Measure of Auditory Perception and Listening Effort Across the Lifespan: A Review. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Hear. Balance Med. 2025, 6, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020024

Raghavendra S. Pupillometry as an Objective Measure of Auditory Perception and Listening Effort Across the Lifespan: A Review. Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine. 2025; 6(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaghavendra, Shruthi. 2025. "Pupillometry as an Objective Measure of Auditory Perception and Listening Effort Across the Lifespan: A Review" Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine 6, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020024

APA StyleRaghavendra, S. (2025). Pupillometry as an Objective Measure of Auditory Perception and Listening Effort Across the Lifespan: A Review. Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, Hearing and Balance Medicine, 6(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ohbm6020024