Recent Trends and Future Directions in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers

Abstract

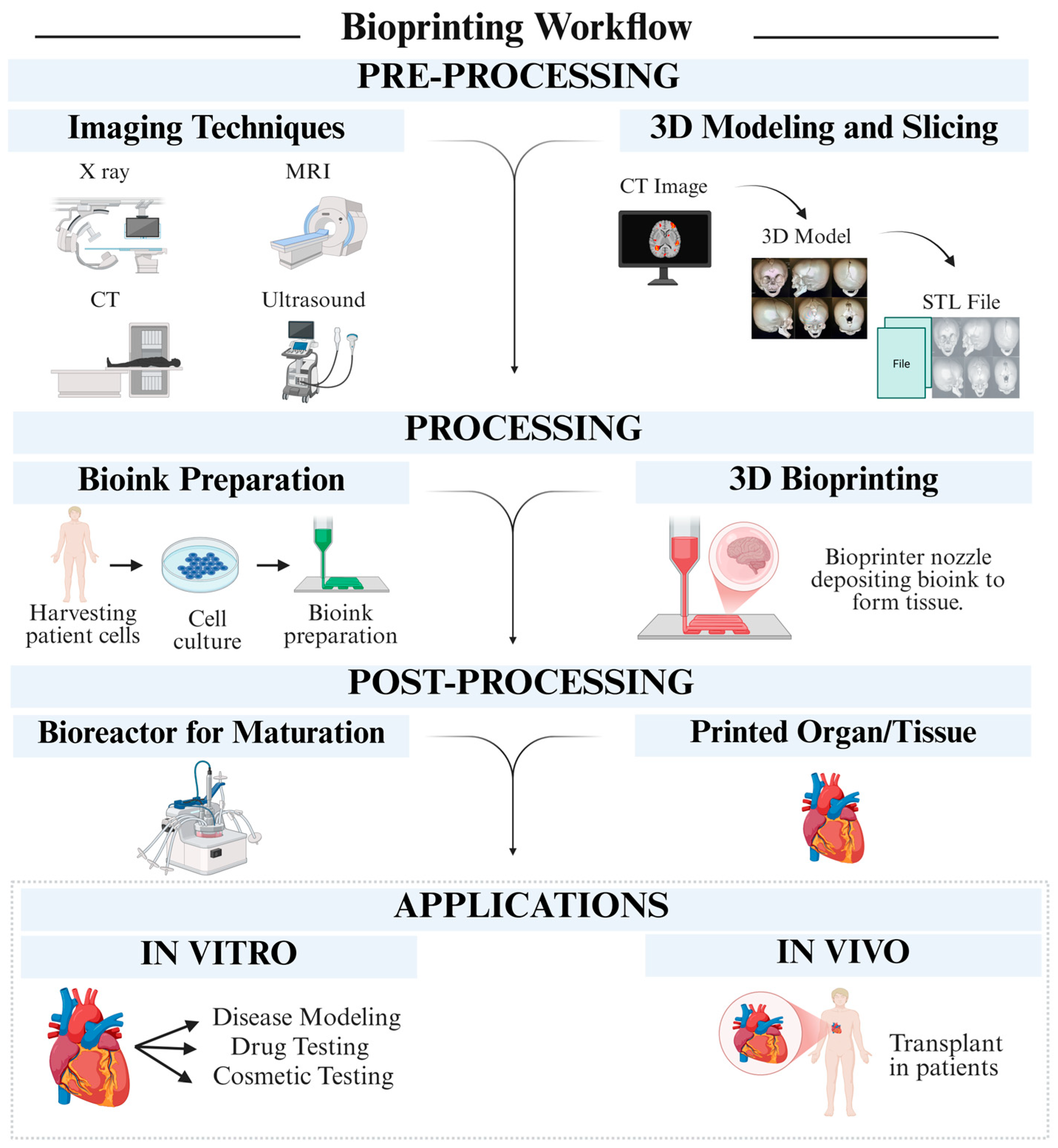

1. Introduction

2. Advantages and Limitations of Biocompatible Polymers

3. Fundamentals of 3D Printing and Biocompatible Polymers

3.1. Natural Polymers

3.1.1. Chitosan

3.1.2. Cellulose

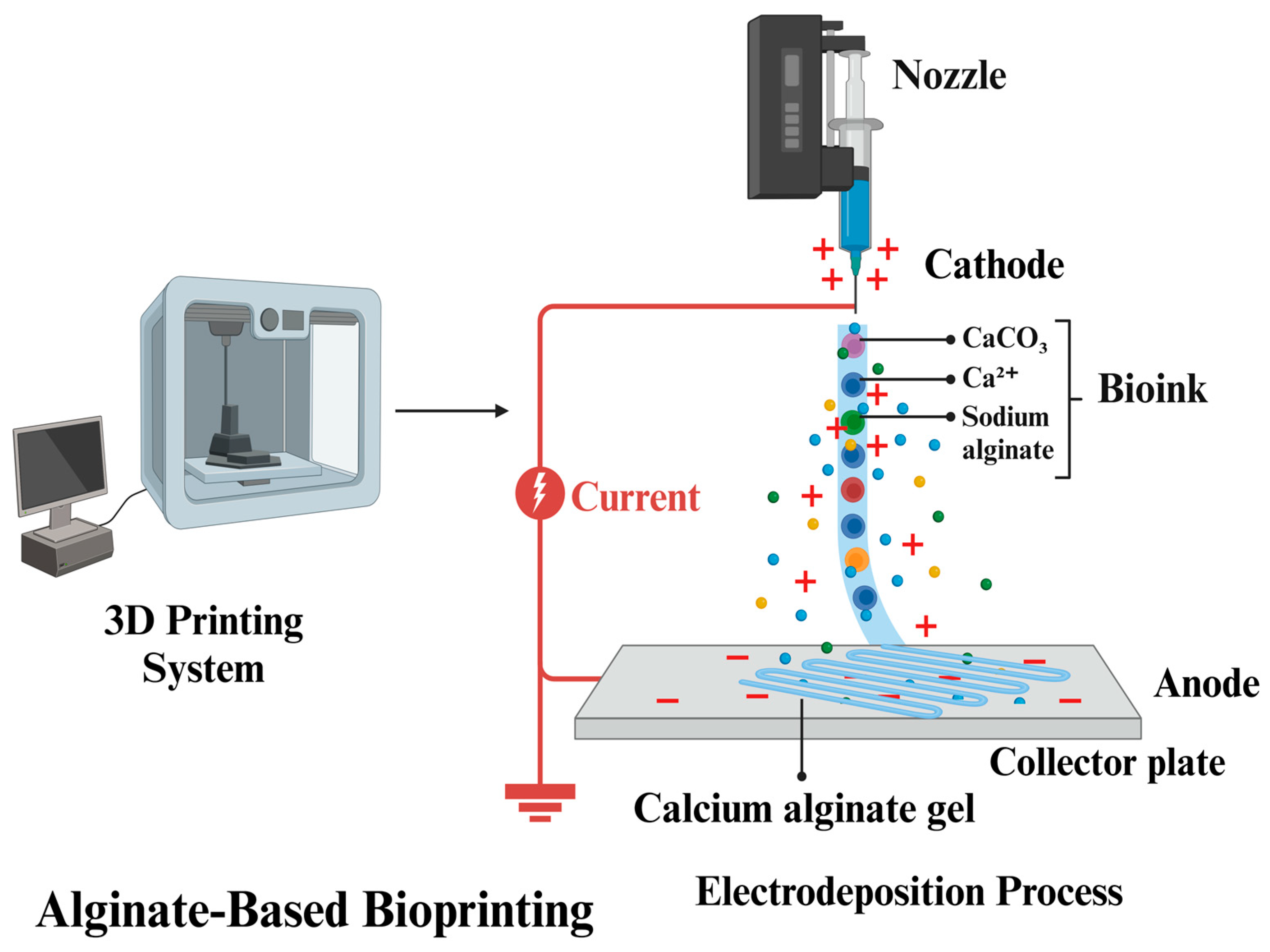

3.1.3. Alginate

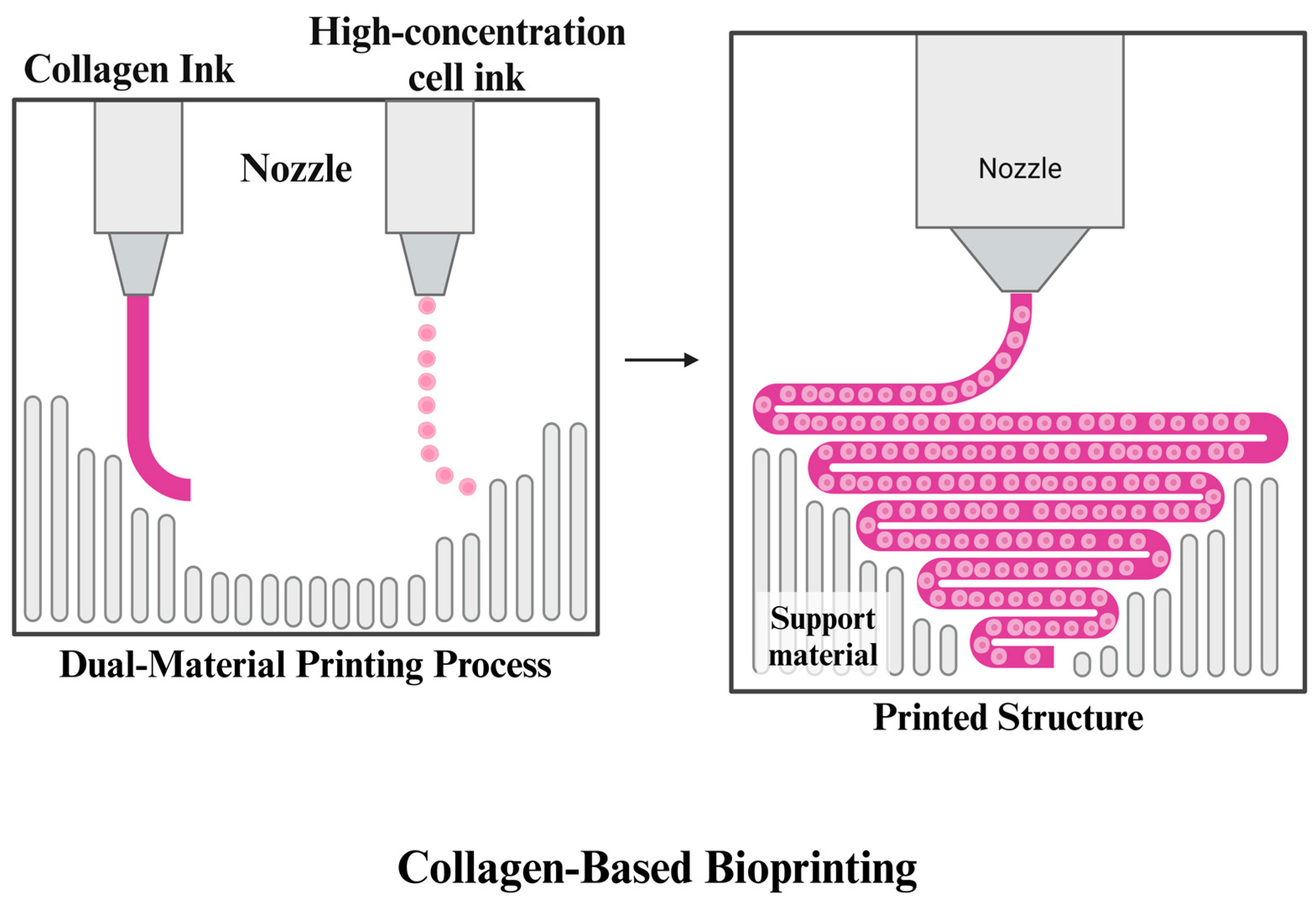

3.1.4. Collagen

3.1.5. Dextran

3.2. Synthetic Polymers

3.2.1. Polylactic Acid (PLA)

3.2.2. Polycaprolactone (PCL)

3.2.3. Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)

3.2.4. Poly β-Amino Ester (PBAE)

3.2.5. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)

3.2.6. Polyvinyl Pyrrolidine (PVP)

4. Recent Trends in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers

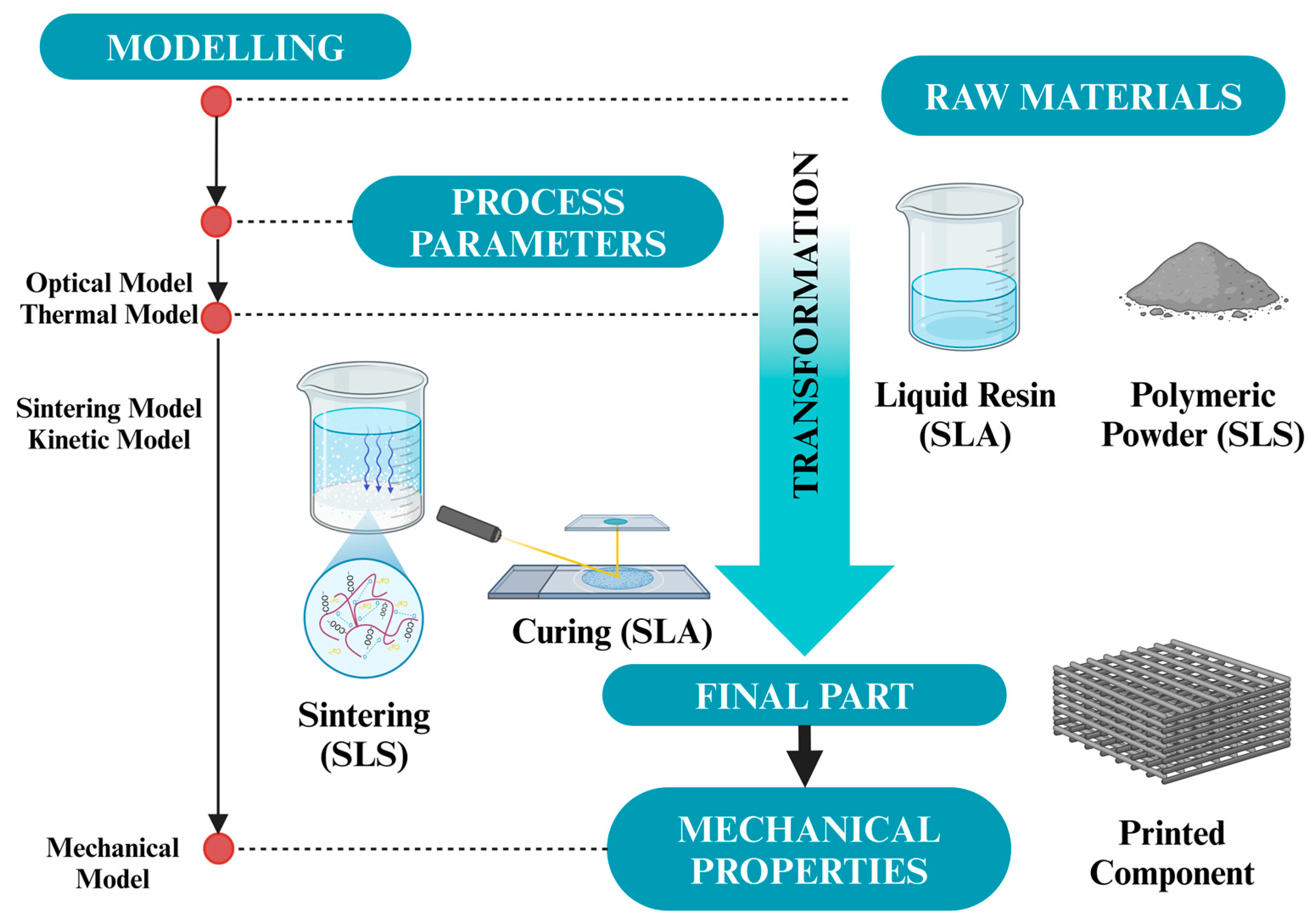

4.1. Additive Manufacturing Technologies

4.1.1. Stereolithography (SLA)

| Bioprinting Technique | Description | Advantages | Applications | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Uses UV light to polymerize resin in a layer-by-layer fashion. | - High resolution and detail; fast print times for small objects | Tissue engineering; organ models | - Limited material options; resin toxicity during printing | [115] |

| Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) | Extrudes thermoplastic filament through a nozzle to create layers. | - Cost-effective; widely available technology; can use various materials | Drug delivery systems; scaffolds for tissue repair | - Lower resolution compared to SLA; limitations in material strength | [116] |

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | Utilizes a laser to fuse powdered materials based on a digital model. | - Can utilize various materials; no support structures needed due to powder bed | Bone grafts; complex structures requiring precision | - Expensive equipment; post-processing needed for powder removal | [117] |

| Inkjet Bioprinting | Droplets of bioink are deposited to form 2D and 3D structures. | - High throughput; suitable for living cells; allows for precise patterns | Printing cell arrays; skin substitutes; vascular models | - Limited viscosity range; cell damage from heat during droplet formation | [118] |

| Direct Ink Writing (DIW) | Involves extruding a gel-like bioink through a nozzle to create 3D structures. | - High versatility in material use; good control over structure | Soft tissue engineering; cell-laden constructs | - Requires precise control of bioink viscosity; limited to certain material types | [119] |

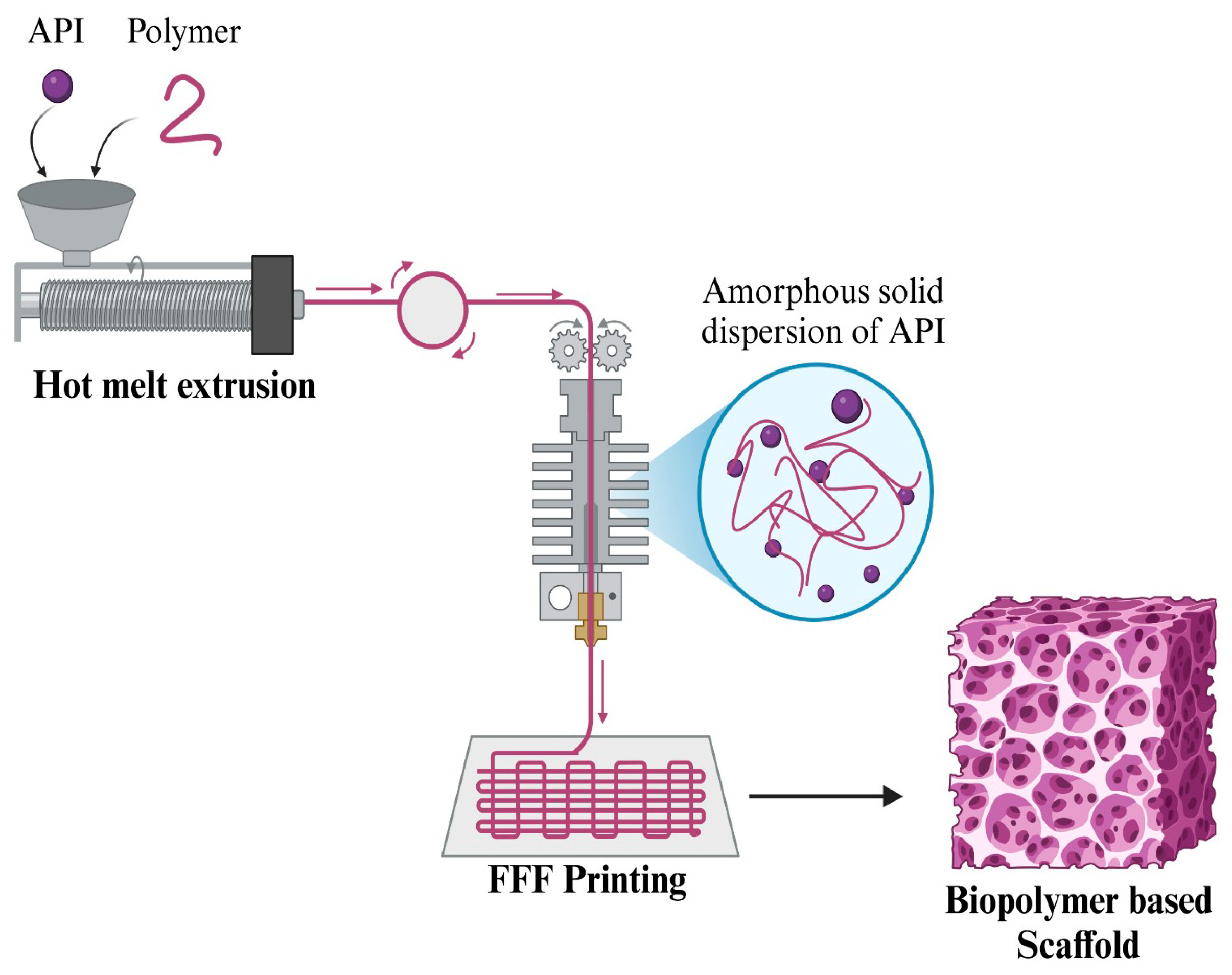

4.1.2. Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF)

4.1.3. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

4.1.4. Inkjet Printing and Direct Ink Writing

4.2. Advancements in Polymer Modification

4.3. Applications

4.3.1. Tissue Engineering Scaffolds

4.3.2. Drug Delivery Systems

4.3.3. Biosensors and Medical Devices

4.4. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)/European Medicines Agency (EMA) Guidelines in 3D Printing of Biomedical Devices

4.5. Commercially Accessible 3D-Printed Biomedical Products

5. Challenges in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers

| Tissue/Organ | Biopolymer Used | Outcomes | Challenges | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Collagen and Gelatin | Successful integration with surrounding tissues; improved functionality in wound healing | Limited durability; long-term effectiveness needs further study | [233] |

| Heart Valve | Alginate and Gelatin | Improved compliance and structural integrity; potential for transplantation | Need for precise mechanical properties to imitate natural heart valve function | [234] |

| Cartilage | Alginate and Chitosan | Enhanced chondrogenesis with promising tissue regeneration outcomes | Limited mechanical strength; heterogeneity in cellular distribution | [235] |

| Bone | Hydroxyapatite and Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Demonstrated osteoconductivity; integration into host bone with favorable healing | Ensuring adequate vascularization; long-term integration and biomechanical properties | [236] |

| Vascular Structures | Gelatin, PEG, and Fibrin | Formation of functional vascular networks within engineered tissues | Minimizing thrombosis; optimizing cell-laden delivery systems | [237] |

| Nerve Regeneration | Polycaprolactone (PCL) and Gelatin | Preliminary indications of successful neuroregeneration | Ensuring accurate alignment of nerve fibers; biocompatibility | [238] |

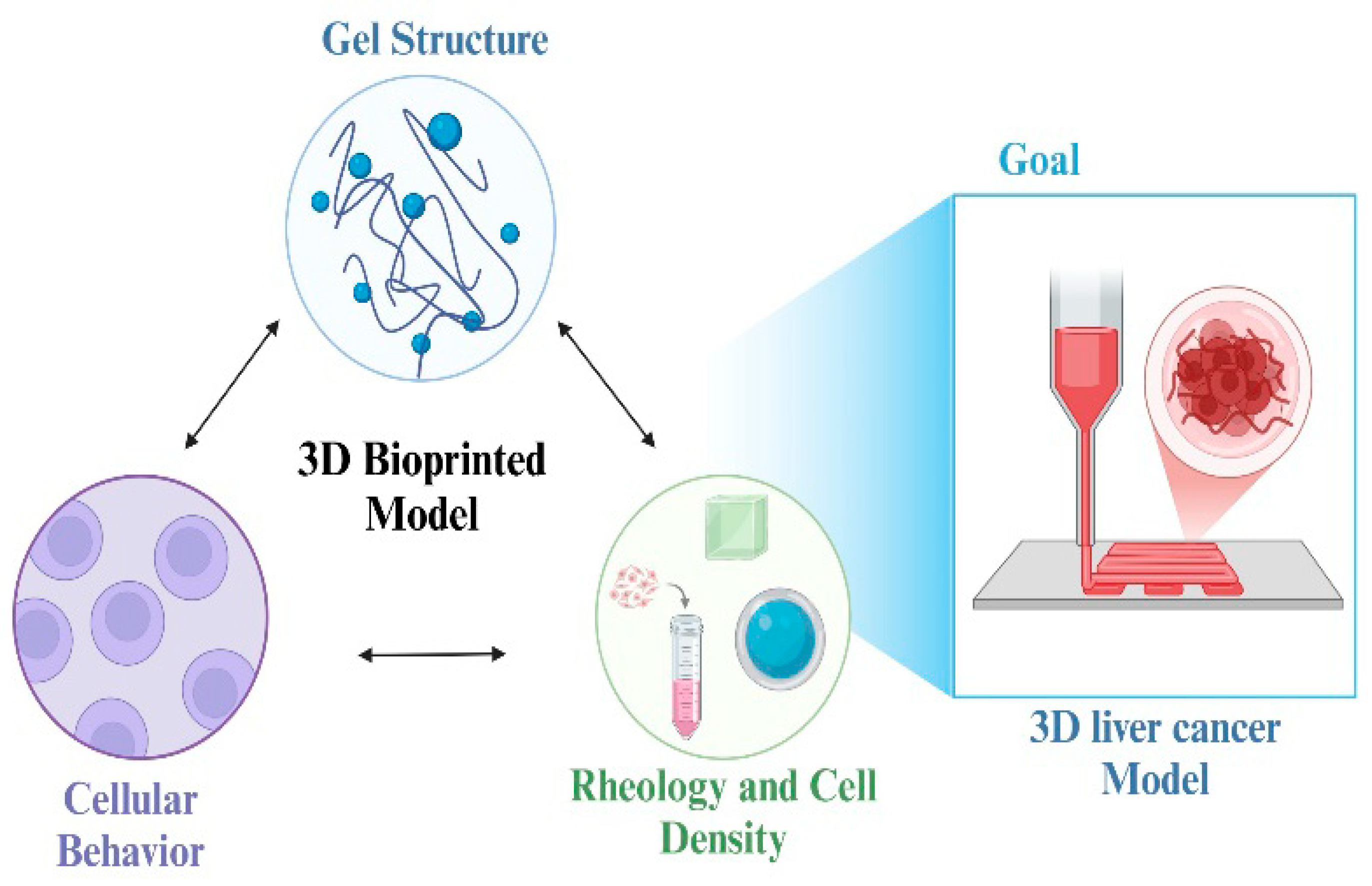

| Liver | Decellularized ECM and Gelatin | Enhanced hepatocyte function; improved model for drug testing | Recreating multi-cell interactions; maintaining liver-specific functions in vitro | [239] |

| Craniofacial Implants | PLA and PEEK | Customized fitness leading to improved clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction | Ensuring proper mechanical properties for longevity; challenges in integrating with existing bone | [240] |

| Tendon and Ligament | Gelatin, Fibrin | Improved cell survival and healing outcomes in volumetric structures | Limited understanding of the mechanical cue for differentiation; collagen organization | [241] |

6. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

7. Conclusions

- Advances in bioprinting methods have improved the capacity to print intricate tissue architectures.

- Enhanced rheological properties of bioinks have been essential for successful extrusion and print quality.

- 3D bioprinting has tremendous potential for applications in personalized medicine, drug discovery, and organ transplantation.

- The main obstacles to overcome are the mechanical instability of constructions, material anisotropy, and the necessity for improved biodegradability.

- Maintaining the structural stability of printed constructs under physiological loads is critical for clinical use.

- The creation of isotropic materials that behave consistently under different mechanical loads.

- The necessity for bioinks that not only support structure but also degrade in a predictable manner after serving their purpose in the body.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, G.; Dubey, S.; Sharma, G.; Singh, S.; Minz, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; et al. 3D Bioprinting for Skin and Tissue Engineering. In 3D Printing and Microfluidics in Dermatology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 125–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.; Wahab, A.; Khan, S.U.; Naeem, M.; Rehman, K.U.; Ali, H.; Ullah, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, N.R.; Rizg, W.Y.; et al. 3D printing technology: A new approach for the fabrication of personalized and customized pharmaceuticals. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 195, 112240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W.; Watson, J.A.; Ben-Nissan, B.; Watson, G.S.; Stamboulis, A. Synthetic tissue engineering with smart, cytomimetic protocells. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 120941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, F.; Kalva, S.N.; Koç, M. Additive Manufacturing of Polymer/Mg-Based Composites for Porous Tissue Scaffolds. Polymers 2022, 14, 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salg, G.A.; Poisel, E.; Neulinger-Munoz, M.; Gerhardus, J.; Cebulla, D.; Bludszuweit-Philipp, C.; Vieira, V.; Nickel, F.; Herr, I.; Blaeser, A.; et al. Toward 3D-bioprinting of an endocrine pancreas: A building-block concept for bioartificial insulin-secreting tissue. J. Tissue Eng. 2022, 13, 20417314221091033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furko, M.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Calcium Phosphate Loaded Biopolymer Composites—A Comprehensive Review on the Most Recent Progress and Promising Trends. Coatings 2023, 13, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaeigohar, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Nature-Derived and Synthetic Additives to poly(ɛ-Caprolactone) Nanofibrous Systems for Biomedicine; an Updated Overview. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 809676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monia, T. Sustainable natural biopolymers for biomedical applications. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 37, 2505–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Kathuria, H.; Dubey, N. Advances in 3D bioprinting of tissues/organs for regenerative medicine and in-vitro models. Biomaterials 2022, 287, 121639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, Z.; Johnston, J.D.; Cooper, D.M.L.; Chen, X. 3D Bioprinted Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: State-Of-The-Art and Emerging Technologies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 824156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu Queirós Osório, L.A. Can Electrospun Scaffolds Be Used for the Support of Breast Tissue Culture in a Breast-on-a-Chip Model? Ph.D. Thesis, Brunel University, London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, M.; Naniz, M.A.; Kouhi, M.; Saberi, A.; Zolfagharian, A.; Bodaghi, M. Recent progress in extrusion 3D bioprinting of hydrogel biomaterials for tissue regeneration: A comprehensive review with focus on advanced fabrication techniques. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 9, 535–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangarshahi, B.M.; Naghib, S.M. Multicomponent 3D-printed Collagen-based Scaffolds for Cartilage Regeneration: Recent Progress, Developments, and Emerging Technologies. Curr. Org. Chem. 2024, 28, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Wahab, A.; Khan, D.; Saeed, S.; Khan, S.U.; Ullah, N.; Saleh, T.A. Modified gold and polymeric gold nanostructures: Toxicology and biomedical applications. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 42, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamzadeh, V. High-Resolution Vat-Photopolymerization-Based 3D Printing of Biocompatible Materials for Organ-on-a-Chip Applications and Capillarics. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Siemiński, P. Introduction to fused deposition modeling. In Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 217–275. [Google Scholar]

- Naghib, S.M.; Zarrineh, M.; Moepubi, M.R.; Mozafari, M.R. 3D Printing Chitosan-based Nanobiomaterials for Biomedicine and Drug Delivery: Recent Advances on the Promising Bioactive Agents and Technologies. Curr. Org. Chem. 2024, 28, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheilmoghaddam, F.; Rumble, M.; Cooper-White, J. High-Throughput Routes to Biomaterials Discovery. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10792–10864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirier, J. Rapid Liquid 3D-Printing of Microchannels Using Aqueous Two-Phase Systems: Towards Vascular Tissue Modelling Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.; Hamayun, S.; Wahab, A.; Khan, S.U.; Rehman, M.U.; Haq, Z.U.; Rehman, K.U.; Ullah, A.; Mehreen, A.; Awan, U.A.; et al. Smart Technologies used as Smart Tools in the Management of Cardiovascular Disease and their Future Perspective. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchin, A.; Farzaneh, S.; Porjabbar, B.; Sadegian, F.; Estaji, M.; Ranjbarvan, P.; Kanafimahbob, M.; Ranjbari, J.; Salehi-Nik, N.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; et al. Regenerative medicine under the control of 3D scaffolds: Current state and progress of tissue scaffolds. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 16, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornyak, G.L.; Moore, J.J.; Tibbals, H.; Dutta, J. Fundamentals of Nanotechnology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martău, G.A.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C. The Use of Chitosan, Alginate, and Pectin in the Biomedical and Food Sector—Biocompatibility, Bioadhesiveness, and Biodegradability. Polymers 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Awan, U.A.; Ali, H.; Wahab, A.; Khan, S.U.; Naeem, M.; Ruslin, M.; Mustopa, A.Z.; Hasan, N. Carbon Dots: New Rising Stars in the Carbon Family for Diagnosis and Biomedical Applications. J. Nanotheranostics 2024, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Singh, J.; Ilyas, R.A.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Razman, M.R. Critical Review of Biodegradable and Bioactive Polymer Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, G.; Galler, K.M. Biocompatibility of biomaterials–Lessons learned and considerations for the design of novel materials. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, T. Biopolymers for tissue engineering applications: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 41, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, J.M. Comparison of Statically and Dynamically Determined Young’s Modulus of Rocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1936, 22, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, C.C.; Smith, D.K. Multicomponent polysaccharide alginate-based bioinks. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8171–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biazar, E.; Moghaddam, S.Y.Z.; Esmaeili, J.; Kheilnezhad, B.; Goleij, F.; Heidari, S. Tannic Acid as a Green Cross-linker for Biomaterial Applications. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 1320–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Badgujar, N.P.; Nikzad, S.; Badgujar, S.; Choudhury, S.; Bhat, R.; Soni, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Gupta, S.; et al. Chitosan as a tool for tissue engineering and rehabilitation: Recent developments and future perspectives—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Awan, U.A.; Muhaymin, A.; Naeem, M.; Yoo, J.-W.; Mehreen, A.; Safdar, A.; Hasan, N.; Haider, A.; Fakhar-Ud-Din. Cancer nanomedicine: Smart arsenal in the war against cancer. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 174, 114030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.S.; Galarraga, J.H.; Cui, X.; Lindberg, G.C.J.; Burdick, J.A.; Woodfield, T.B.F. Fundamentals and Applications of Photo-Cross-Linking in Bioprinting. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10662–10694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, L.; Bocchetti, M.; Di Biase, A.; Regad, T. Cancer stem cells and targeting strategies. Cells 2019, 8, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambié, D.; Bottecchia, C.; Straathof, N.J.W.; Hessel, V.; Noël, T. Applications of Continuous-Flow Photochemistry in Organic Synthesis, Material Science, and Water Treatment. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10276–10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.S.B.; Ponnamma, D.; Choudhary, R.; Sadasivuni, K.K. A Comparative Review of Natural and Synthetic Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds. Polymers 2021, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bhende, M. An overview: Non-toxic and eco-friendly polysaccharides—Its classification, properties, and diverse applications. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 12383–12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Shanmugavadivu, A.; Selvamurugan, N. Tunable mechanical properties of chitosan-based biocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Sameen, D.E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, R.; Dai, J.; Li, S.; Qin, W. A review of cellulose and its derivatives in biopolymer-based for food packaging application. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Azadi, E.; Hussain, C.M. State-of-the-art of 3D printing technology of alginate-based hydrogels—An emerging technique for industrial applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 293, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasravi, M.; Ahmadi, A.; Babajani, A.; Mazloomnejad, R.; Hatamnejad, M.R.; Shariatzadeh, S.; Bahrami, S.; Niknejad, H. Immunogenicity of decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds: A bottleneck in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Pei, Y.; Tang, K.; Albu-Kaya, M.G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Structure, extraction, processing, and applications of collagen as an ideal component for biomaterials-a review. Collagen Leather 2023, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, T.; Helalat, S.H.; Yesibolati, M.N.; Sun, Y. Synthesis of eco-friendly multifunctional dextran microbeads for multiplexed assays. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 666, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalala, K.; Jadeja, D.; Dudhat, K. Microspheres: Preparation Methods, Advances, Applications, and Challenges in Drug Delivery. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025, 4, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, C.; Ghosh, S.; Saha, S.; Ray, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Pal, S.; Dey, S. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers–properties, applications and future prospects. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 192, 112068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahini, M.G. Polylactic acid (PLA)-based materials: A review on the synthesis and drug delivery applications. Emergent Mater. 2023, 6, 1461–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Shan, M.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Meng, L.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Convergence of 3D Bioprinting and Nanotechnology in Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wu, Z.; Chu, C.; Ni, Y.; Neisiany, R.E.; You, Z. Biodegradable Elastomers and Gels for Elastic Electronics. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, G. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Polycaprolactone Based Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Genova, Genova, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/6840 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Karlsson, J.; Rhodes, K.R.; Green, J.J.; Tzeng, S.Y. Poly(beta-amino ester)s as gene delivery vehicles: Challenges and opportunities. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 1395–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piluso, S.; Skvortsov, G.A.; Altunbek, M.; Afghah, F.; Khani, N.; Koç, B.; Patterson, J. 3D bioprinting of molecularly engineered PEG-based hydrogels utilizing gelatin fragments. Biofabrication 2021, 13, 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Aftab, M.; Ullah, M.; Nguyen, P.T.; Agustina, R.; Djabir, Y.Y.; Tockary, T.A.; Uchida, S. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery system for Oral Cancer: Mechanism, challenges, and therapeutic potential. Results Chem. 2025, 14, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.-F.; Yang, S.; Lin, J.-C.; Teng, H.-R.; Fan, L.-W.; Chiu, J.N.; Yuan, Y.-P.; Martin, V. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-enabled significant suppression of supercooling of erythritol for medium-temperature thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimi, A.; Okoro, O.V.; Podstawczyk, D.; Siminska-Stanny, J.; Shavandi, A. Natural Hydrogel-Based Bio-Inks for 3D Bioprinting in Tissue Engineering: A Review. Gels 2022, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrot, A.V.; Sathiyasree, M.; Rahim, S.B.A.; Renitta, R.E.; Kasipandian, K.; Krithika Shree, S.; Rajalakshmi, D.; Shobana, N.; Dhiva, S.; Abirami, S.; et al. Scaffold using chitosan, agarose, cellulose, dextran and protein for tissue engineering—A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhlouli, M.; Pourhadi, M.; Karami, F.; Talebi, Z.; Ranjbari, J.; Khojasteh, A. Applications of Bacterial Cellulose as a Natural Polymer in Tissue Engineering. Asaio J. 2021, 67, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifah, N.; Palungan, J.; Ardayanti, K.; Ullah, M.; Nurkhasanah, A.N.; Mustopa, A.Z.; Lallo, S.; Agustina, R.; Yoo, J.-W.; Hasan, N. Development of Clindamycin-Releasing Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogel with Self-Healing Property for the Effective Treatment of Biofilm-Infected Wounds. Gels 2024, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourehab, M.A.S.; Pramanik, S.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Abualsoud, B.M.; Kadi, A.; Ansari, M.J.; Deepak, A. Recent Advances of Chitosan Formulations in Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ravichandran, D.; Jambhulkar, S.; Kakarla, M.; Bawareth, M.; Lanke, S.; Song, K. Review of Fiber-Based Three-Dimensional Printing for Applications Ranging from Nanoscale Nanoparticle Alignment to Macroscale Patterning. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 7538–7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, K.; Ullah, M.; Yoo, J.W.; Aiman, U.; Ghazanfar, M.; Naeem, M. Role of Nutrition in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Recent Prog. Nutr. 2025, 5, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridou, M.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Lamprou, D.A. 3D Bioprinted Chitosan-Based Hydrogel Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering and Localised Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, K.; Heinze, T.; Groth, T.; Zhang, K. Recent Progress on Cellulose-Based Ionic Compounds for Biomaterials. Adv. Mater. 2020, 33, e2000717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendiran, B.; Muthusamy, S.; Sampath, S.; Jaisankar, S.; Popat, K.C.; Selvakumar, R.; Krishnakumar, G.S. Recent trends in natural polysaccharide based bioinks for multiscale 3D printing in tissue regeneration: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 564–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurminen, A. Novel Cornea-Specific Bioink for 3D Bioprinting. Master’s Thesis, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tunçer, S. Biopolysaccharides: Properties and applications. In Polysaccharides: Properties and Applications; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 95–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.; Wahab, A.; Khan, S.U.; Zaman, U.; Rehman, K.U.; Hamayun, S.; Naeem, M.; Ali, H.; Riaz, T.; Saeed, S.; et al. Stent as a Novel Technology for Coronary Artery Disease and Their Clinical Manifestation. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022, 48, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Shahid, M.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Sheikh, M.S.; Rahman, M.S.; Uddin, N.; Rahim, A.; Khan, R.A.; Hossain, I. Sources, extractions, and applications of alginate: A review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šurina, P. Optimization and In-Depth Analysis of Alginate Nanocellulose Hydrogels for 3D Printing of Vascular and Integumentary Systems. Master’s Thesis, University of Split, Faculty of Science, Department of Chemistry, Split, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wan, W.; Hu, C.; Liu, Z.; Wong, C.T.; Fukuda, T.; Shen, Y. Hybrid 3D printing and electrodeposition approach for controllable 3D alginate hydrogel formation. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 025032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphate (CaPO4) containing composites for biomedical applications: Formulations, properties, and applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Mei, X.; Cai, L.; Lin, K.; Rodríguez, J.F.; Ye, Z.; Parraguez, X.S.; Guajardo, E.M.; Luna, P.C.G.; et al. Engineered Living Systems Based on Gelatin: Design, Manufacturing, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.-M.; Bang, C.; Park, M.; Shin, S.; Yun, S.; Kim, C.M.; Jeong, G.; Chung, Y.-J.; Yun, W.-S.; Lee, J.H.; et al. 3D-Printed Collagen Scaffolds Promote Maintenance of Cryopreserved Patients-Derived Melanoma Explants. Cells 2021, 10, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Hudson, A.R.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Tashman, J.W.; Hinton, T.J.; Yerneni, S.; Bliley, J.M.; Campbell, P.G.; Feinberg, A.W. 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Science 2019, 365, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, M.C.; Lameirinhas, N.S.; Carvalho, J.P.F.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R. A Guide to Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogel Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescosolido, L.; Schuurman, W.; Malda, J.; Matricardi, P.; Alhaique, F.; Coviello, T.; van Weeren, P.R.; Dhert, W.J.A.; Hennink, W.E.; Vermonden, T. Hyaluronic Acid and Dextran-Based Semi-IPN Hydrogels as Biomaterials for Bioprinting. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, N.; Wang, Y.; Wan, H.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Nanoparticle-Stabilized Emulsion Bioink for Digital Light Processing Based 3D Bioprinting of Porous Tissue Constructs. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, e2102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Dana, H.R. Poly lactic acid (PLA) polymers: From properties to biomedical applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2022, 71, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Ahmad, S. A Review on Materials Application in Scaffold Design by Fused Deposition Method. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2023, 104, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, N.; Utzeri, M.A.; Sciortino, A.; Cannas, M.; Messina, F.; Cavallaro, G.; Giammona, G. Printable Thermo- and Photo-stable Poly(D,L-lactide)/Carbon Nanodots Nanocomposites via Heterophase Melt-Extrusion Transesterification. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamayun, S.; Ullah, M.; Rehman, M.U.; Hussain, M.; Khan, A.I.; Shah, S.N.A.; Waleed, A.; Muneeb, T.; Khan, T. Rational Therapeutic Approaches for the Management of Congestive Cardiac Failure. J. Bashir Inst. Health Sci. 2023, 4, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Torretti, M.; Madbouly, S. Biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL) based polymer and composites. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, 4391–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.R.; Modi, C.D.; Singh, S.; Mori, D.D.; Soniwala, M.M.; Prajapati, B.G. Recent Advances in Additive Manufacturing of Polycaprolactone-Based Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2024, 11, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathan, S.; Dejob, L.; Schipani, R.; Haffner, B.; Möbius, M.E.; Kelly, D.J. Fiber Reinforced Cartilage ECM Functionalized Bioinks for Functional Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1801501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Liu, M.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; et al. Hydrogels for 3D bioprinting in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: Current progress and challenges. Int. J. Bioprint. 2023, 9, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javkhlan, Z.; Hsu, S.-H.; Chen, R.-S.; Chen, M.-H. 3D-printed polycaprolactone scaffolds coated with beta tricalcium phosphate for bone regeneration. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2023, 123, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Yin, Z.; Butt, H.A.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. The synthesis, mechanisms, and additives for bio-compatible polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels: A review on current advances, trends, and future outlook. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2023, 29, 939–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wan, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, D.; Lu, H. Janus structure hydrogels: Recent advances in synthetic strategies, biomedical microstructure and (bio)applications. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 3003–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Xie, Z.; Dekishima, Y.; Kuwagaki, S.; Sakai, N.; Matsusaki, M. “Out-of-the-box” Granular Gel Bath Based on Cationic Polyvinyl Alcohol Microgels for Embedded Extrusion Printing. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, e2300025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Bibi, A.; Wahab, A.; Hamayun, S.; Rehman, M.U.; Khan, S.U.; Awan, U.A.; Riaz, N.-U.; Naeem, M.; Saeed, S.; et al. Shaping the Future of Cardiovascular Disease by 3D Printing Applications in Stent Technology and its Clinical Outcomes. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 49, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Ullah, M.; Saeed, S.; Saleh, E.A.M.; Kassem, A.F.; Arbi, F.M.; Wahab, A.; Rehman, M.; Rehman, K.U.; Khan, D.; et al. Nanotherapeutic approaches for transdermal drug delivery systems and their biomedical applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 207, 112819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.U.; Khalid, M.Y.; Noroozi, R.; Sadeghianmaryan, A.; Jalalvand, M.; Hossain, M. Recent advances in 3D-printed polylactide and polycaprolactone-based biomaterials for tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 930–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.J.; Im, H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.W.; Jung, Y. Toward Biomimetic Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: 3D Printing Techniques in Regenerative Medicine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 586406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolívar-Monsalve, E.J.; Alvarez, M.M.; Hosseini, S.; Espinosa-Hernandez, M.A.; Ceballos-González, C.F.; Sanchez-Dominguez, M.; Shin, S.R.; Cecen, B.; Hassan, S.; Di Maio, E.; et al. Engineering bioactive synthetic polymers for biomedical applications: A review with emphasis on tissue engineering and controlled release. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4447–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroia, J.; Yanen, W.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, K.; Lu, T.; Zhang, B. A review on biocompatibility nature of hydrogels with 3D printing techniques, tissue engineering application and its future prospective. Bio-Design Manuf. 2018, 1, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Wei, G.; Su, Z. Recent Advances in Peptide Engineering of PEG Hydrogels: Strategies, Functional Regulation, and Biomedical Applications. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2200385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh Krishna, B.; Francis Luther King, M.; Robert Singh, G.; Gopichand, A. 3D printing in drug delivery and healthcare. In Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Techniques for Biomedical Applications; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 241–274. [Google Scholar]

- Veeman, D.; Sai, M.S.; Sureshkumar, P.; Jagadeesha, T.; Natrayan, L.; Ravichandran, M.; Mammo, W.D. Additive Manufacturing of Biopolymers for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: An Overview, Potential Applications, Advancements, and Trends. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 2021, 4907027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y. Controllable and biocompatible 3D bioprinting technology for microorganisms: Fundamental, environmental applications and challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 69, 108243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyratsis, P.; Tzotzis, A.; Davim, J.P. A Review on CAD-Based Programming for Design and Manufacturing. In CAD-Based Programming for Design and Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jobczyk, H.; Homann, H. Automatic Reverse Engineering: Creating computer-aided design (CAD) models from multi-view images. In DAGM German Conference on Pattern Recognition; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zeb, F.; Saeed, R.F.; Shaheed, S.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.I.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.; Khan, M.; Khan, M.; Khan, M.; et al. Nutrition and Dietary Intervention in Cancer: Gaps, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. In Nutrition and Dietary Interventions in Cancer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 281–307. [Google Scholar]

- Karakullukcu, A.B.; Taban, E.; Ojo, O.O. Biocompatibility of biomaterials and test methods: A review. Mater. Test. 2023, 65, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüceer, Ö.M.; Öztürk, E.K.; Çiçek, E.S.; Aktaş, N.; Güngör, M.B. Three-Dimensional-Printed Photopolymer Resin Materials: A Narrative Review on Their Production Techniques and Applications in Dentistry. Polymers 2025, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çerlek, Ö.; Kesercioğlu, M.A.; Han, K. Stereolithography (SLA): An Innovative Additive Manufacturing Process. New Trends Front. Eng. 2024, 3, 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht, Y.S.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Thakur, A.K.; Priyadarshi, N.; Twala, B. Recent Trends and Technologies in rapid prototyping and its Inclination towards Industry 4.0. Sustain. Eng. Innov. 2024, 6, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.; Allen, W.S.; Arroyo-Currás, N.; Hur, S.C. Rapid prototyping of thermoplastic microfluidic devices via SLA 3D printing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LM, C.; Dimitrov, R. Rapid Prototyping Technologies-Advantages and Disadvantages; Annals of ‘Constantin Brancusi’ University of Targu-Jiu; Engineering Series/Analele Universităţii Constantin Brâncuşi din Târgu-Jiu; Seria Inginerie. 2021. Available online: https://www.utgjiu.ro/rev_ing/pdf/2021-4/23_C_R%C4%82DULESCU_RAPID%20PROTOTYPING%20TECHNOLOGIES%20-%20ADVANTAGES%20AND%20DISADVANTAGES.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Shahzadi, L.; Maya, F.; Breadmore, M.C.; Thickett, S.C. Functional Materials for DLP-SLA 3D Printing Using Thiol–Acrylate Chemistry: Resin Design and Postprint Applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 3896–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, C.; Civera, M.; Ruiz, O.G.; Pedullà, P.; Reinoso, M.R.; Tommasi, G.; Vollaro, M.; Burgio, V.; Surace, C. Effects of Curing on Photosensitive Resins in SLA Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Mech. 2021, 2, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matykiewicz, D. Hybrid Epoxy Composites with Both Powder and Fiber Filler: A Review of Mechanical and Thermomechanical Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Duan, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, B.; Wang, G.; Chen, F. Uniform rate debinding for Si3N4 vat photopolymerization 3D printing green parts using a specific-stage stepwise heating process. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 84, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, Í.L.D. Additive Manufacturing of Advanced Ceramics by Digital Light Processing: Equipment, Slurry, and 3D Printing. Ph.D. Thesis, Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos, University of São Paulo, São Carlos, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germaini, M.-M.; Belhabib, S.; Guessasma, S.; Deterre, R.; Corre, P.; Weiss, P. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering–A critical review of the state of the art and new concepts. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 130, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ravichandran, D.; Ramanathan, A.; Sobczak, M.T.; Sacco, A.F.; Patil, D.; Thummalapalli, S.V.; Pulido, T.V.; Lancaster, J.N.; et al. 3D-Printed Polymeric Biomaterials for Health Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 14, e2402571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasoglu, S.; Demirci, U. Bioprinting for stem cell research. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, R.; Wojasiński, M.; Małolepszy, A.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Ciach, T. Fabrication of 3D-Printed Scaffolds with Multiscale Porosity. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29186–29204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buj-Corral, I.; Tejo-Otero, A.; Fenollosa-Artés, F. Use of FDM technology in healthcare applications: Recent advances. In Fused Deposition Modeling Based 3D Printing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 277–297. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Fan, X.; Zhou, H. Recent advances in bioprinting techniques: Approaches, applications and future prospects. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, A.; Stelzl, C.; Eriksson, O.; O’callaghan, P.; Kreuger, J. An open source extrusion bioprinter based on the E3D motion system and tool changer to enable FRESH and multimaterial bioprinting. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiawan, R.B.; Imaduddin, F.; Ariawan, D.; Ubaidillah; Arifin, Z. A review on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing: Filament processing, materials, and printing parameters. Open Eng. 2021, 11, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanamsamy, L.; Harun, W.S.W.; Ishak, I.; Romlay, F.R.M.; Kadirgama, K.; Ramasamy, D.; Idris, S.R.A.; Tsumori, F. A comprehensive review on fused deposition modelling of polylactic acid. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 8, 775–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Roozbahani, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Handroos, H. 3D Printing of Plant-Derived Compounds and a Proposed Nozzle Design for the More Effective 3D FDM Printing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57107–57119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyman, S.M. Design and Development of a Small-Scale Pellet Extrusion System for 3D Printing Biopolymer Materials and Composites. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Engineering and Advanced Technology, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, S.E.; Gholami, M.; Shahmabadi, H.E.; Reher, P. Resorbable GBR Scaffolds in Oral and Maxillofacial Tissue Engineering: Design, Fabrication, and Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.K.; Rahman, M.H.; Slater, E.; Patel, R.; Evangelista, C.; Austin, E.; Tompkins, E.; McCarroll, A.; Rajak, D.K.; Menezes, P.L.; et al. Powder bed fusion–based additive manufacturing: SLS, SLM, SHS, and DMLS. In Tribology of Additively Manufactured Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nimry, S.S.; Daghmash, R.M. Three Dimensional Printing and Its Applications Focusing on Microneedles for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepelnjak, T.; Stojšić, J.; Sevšek, L.; Movrin, D.; Milutinović, M. Influence of Process Parameters on the Characteristics of Additively Manufactured Parts Made from Advanced Biopolymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Alghauli, M.A.; Aljohani, M.H.A.; Zafar, M.S. Advanced additive manufacturing in implant dentistry: 3D printing technologies, printable materials, current applications and future requirements. Bioprinting 2024, 42, e00356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhi, M.; Araújo, I.J.d.S.; Asa’ad, F.; Zeenat, L.; Bojedla, S.S.R.; Pati, F.; Zolfagharian, A.; Watts, D.C.; Bottino, M.C.; Bodaghi, M. Recent advances in additive manufacturing of patient-specific devices for dental and maxillofacial rehabilitation. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, M.A.S.R.; Maguire, A.; Pottackal, N.T.; Thakur, S.H.; Ikram, M.M.; Hart, A.J.; Ajayan, P.M.; Rahman, M.M. Direct Ink Writing: A 3D Printing Technology for Diverse Materials. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2108855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, J.A.S. Defect Identification of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Builds Using Photodiode Sensor Readings. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Khan, N.; Ullah, M.; Hamayun, S.; Makhmudov, N.I.; Mbbs, R.; Safdar, M.; Bibi, A.; Wahab, A.; Naeem, M.; et al. 3D printing technology and its revolutionary role in stent implementation in cardiovascular disease. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneja, H.; Salodkar, S.M.; Parmar, A.S.; Chaudhary, S. Hydrogel based 3D printing: Bio ink for tissue engineering. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 367, 120390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Wang, Z.; Lin, J.; Guo, X.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Huang, W. On-Demand Picoliter-Level-Droplet Inkjet Printing for Micro Fabrication and Functional Applications. Small 2024, 20, 2402638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bom, S.; Ribeiro, R.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Santos, C.; Marto, J. On the progress of hydrogel-based 3D printing: Correlating rheological properties with printing behaviour. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 615, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.E.; Rosenzweig, D.H. The rheology of direct and suspended extrusion bioprinting. APL Bioeng. 2021, 5, 011502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Blokzijl, M.M.; Levato, R.; Visser, C.W.; Castilho, M.; E Hennink, W.; Vermonden, T.; Malda, J. Assessing bioink shape fidelity to aid material development in 3D bioprinting. Biofabrication 2017, 10, 014102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin-Doroteo, M.; Mandujano-Tinoco, E.A.; Krötzsch, E. Tailoring of the rheological properties of bioinks to improve bioprinting and bioassembly for tissue replacement. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)–Gen. Subj. 2020, 1865, 129782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, A. Material Extrusion. In Springer Handbook of Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Baniasadi, H.; Ajdary, R.; Trifol, J.; Rojas, O.J.; Seppälä, J. Direct ink writing of aloe vera/cellulose nanofibrils bio-hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 266, 118114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Jiménez, M.S.; Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Fuentes-Aguilar, R.Q. Review on Porous Scaffolds Generation Process: A Tissue Engineering Approach. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Ogale, A.; Fu, J.; Markwald, R.R. Study of Droplet Formation Process during Drop-on-Demand Inkjetting of Living Cell-Laden Bioink. Langmuir 2014, 30, 9130–9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillotin, B.; Souquet, A.; Catros, S.; Duocastella, M.; Pippenger, B.; Bellance, S.; Bareille, R.; Rémy, M.; Bordenave, L.; Amédée, J.; et al. Laser assisted bioprinting of engineered tissue with high cell density and microscale organization. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7250–7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlGhamdi, K.M.; Kumar, A.; Moussa, N.A. Low-level laser therapy: A useful technique for enhancing the proliferation of various cultured cells. Lasers Med. Sci. 2011, 27, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antezana, P.E.; Municoy, S.; Ostapchuk, G.; Catalano, P.N.; Hardy, J.G.; Evelson, P.A.; Orive, G.; Desimone, M.F. 4D Printing: The Development of Responsive Materials Using 3D-Printing Technology. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, B.; Liu, Y.; Song, W.; Fu, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, S. An approach for mechanical property optimization of cell-laden alginate–gelatin composite bioink with bioactive glass nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2020, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-F.; Lu, T.-Y.; Li, Y.-C.E.; Teng, K.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wei, Y.; Lin, T.-E.; Cheng, N.-C.; Yu, J. Design and Synthesis of Stem Cell-Laden Keratin/Glycol Chitosan Methacrylate Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 2814–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Pr, A.K.; Yoo, J.J.; Zahran, F.; Atala, A.; Lee, S.J. A photo-crosslinkable kidney ECM-derived bioink accelerates renal tissue formation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1800992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Jeong, W.; Kang, H.-W. Liver dECM–Gelatin Composite Bioink for Precise 3D Printing of Highly Functional Liver Tissues. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasekharan, L.T.; Nair, P.D.; Nair, S.V.; Jayakumar, R.; Prabaharan, M.; Tamura, H.; Furuike, T.; Mori, K.; Kawano, T.; Nishida, H.; et al. Formulation and characterization of alginate dialdehyde, gelatin, and platelet-rich plasma-based bioink for bioprinting applications. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Y.; Liang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, G.; Yu, Y.; Chen, F. 3D Contour Printing of Anatomically Mimetic Cartilage Grafts with Microfiber-Reinforced Double-Network Bioink. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, e2200179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khati, V.; Ramachandraiah, H.; Pati, F.; Svahn, H.A.; Gaudenzi, G.; Russom, A. 3D Bioprinting of Multi-Material Decellularized Liver Matrix Hydrogel at Physiological Temperatures. Biosensors 2022, 12, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyan, B.P.; Kumar, L. 3D Printing: Applications in Tissue Engineering, Medical Devices, and Drug Delivery. Aaps Pharmscitech 2022, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannayiram, G.; Sendilvelan, S. Importance of nanocomposites in 3D bioprinting: An overview. Bioprinting 2023, 32, e00280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimington, R.; Goh, K.; Chua, C.; Leong, K.; Tan, L.; Tan, Y.; Lim, J.; Lee, J.; Tan, H.; Chia, S.; et al. Feasibility and Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Photopolymerized and Laser Sintered Polymers for Neuronal, Myogenic, and Hepatic Cell Types. Macromol. Biosci. 2018, 18, 1800113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.B.; Nagaraja, S.; Jayaram, N.; Sreenivasa, S.P.; Almakayeel, N.; Khan, T.M.Y.; Kumar, R.; Ammarullah, M.I. Kenaf Fiber and Hemp Fiber Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Filler-Reinforced Epoxy-Based Hybrid Composites for Biomedical Applications: Morphological and Mechanical Characterization. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamat, S.; Ishak, M.R.; Salit, M.S.; Yidris, N.; Ali, S.A.S.; Hussin, M.S.; Manan, M.S.A.; Suffin, M.Q.Z.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Khalil, A.N.M. The Effects of Self-Polymerized Polydopamine Coating on Mechanical Properties of Polylactic Acid (PLA)–Kenaf Fiber (KF) in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). Polymers 2023, 15, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, R.; Zepeda, H.; Zeng, L.; Qiu, J.; Wang, S. 3D Printing Super Strong Hydrogel for Artificial Meniscus. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, V.K.A.; Shyam, R.; Palaniappan, A.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Oh, T.H.; Nathanael, A.J. Self-Healing Hydrogels: Preparation, Mechanism and Advancement in Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulsoom, J.; Ali, S.; Raza, S.; Raza, M.; Shah, S.; Khan, M.; Hussain, S.; Ali, S.; Rehman, S.; Khan, A.; et al. Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Plants. In Revolutionizing Agriculture: A Comprehensive Exploration of Agri-Nanotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Yaneva, A.; Shopova, D.; Bakova, D.; Mihaylova, A.; Kasnakova, P.; Hristozova, M.; Semerdjieva, M. The Progress in Bioprinting and Its Potential Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, G.; Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Maniadi, A. Individualized Ophthalmic Exoplants by Means of Reverse Engineering and 3D Printing Technologies for Treating High Myopia Complications with Macular Buckles. Biomimetics 2020, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, W. MXene-Based Micro-Supercapacitors: Ink Rheology, Microelectrode Design and Integrated System. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 4651–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztorch, B.; Brząkalski, D.; Pakuła, D.; Frydrych, M.; Špitalský, Z.; Przekop, R.E. Natural and Synthetic Polymer Fillers for Applications in 3D Printing—FDM Technology Area. Solids 2022, 3, 508–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z. Exploring biomedical engineering (BME): Advances within accelerated computing and regenerative medicine for a computational and medical science perspective exploration analysis. J. Emerg. Med. OA 2024, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jeong, W.; Atala, A. 3D Bioprinting for Engineered Tissue Constructs and Patient-Specific Models: Current Progress and Prospects in Clinical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2408032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.J.; Jessop, Z.M.; Whitaker, I.S. 3D Bioprinting for Reconstructive Surgery: Techniques and Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Xu, M.; Cui, X.; Yin, J.; Wu, Q. Hybrid 3D Bioprinting of Sustainable Biomaterials for Advanced Multiscale Tissue Engineering. Small, 2025; early view. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaglia, C.; Sheng, Y.; Rodrigues, L.N.; Lei, I.M.; Shields, J.D.; Huang, Y.Y.S. Deployable extrusion bioprinting of compartmental tumoroids with cancer associated fibroblasts for immune cell interactions. Biofabrication 2023, 15, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parupelli, S.K.; Desai, S. The 3D Printing of Nanocomposites for Wearable Biosensors: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Prospects. Bioengineering 2023, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumaiselvan, U.; Kalimuthu, M.; Nagarajan, R.; Mohan, M.; Ismail, S.O.; Mohammad, F.; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Krishnan, K. Fabrication and Characterization of Poly (lactic acid) (PLA) 3D Printing Filament with Cryptostegia grandiflora (CGF) Fiber. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4710685 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Karp, N.; Ng, K.; Tan, Y.; Lim, J.; Lee, J.; Tan, H.; Chia, S.; Tan, L.; Goh, K.; Leong, K.; et al. The GalaFLEX “Empanada” for Direct-to-Implant Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025, 155, 488e–491e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranakoti, L.; Gangil, B.; Bhandari, P.; Singh, T.; Sharma, S.; Singh, J.; Singh, S. Promising Role of Polylactic Acid as an Ingenious Biomaterial in Scaffolds, Drug Delivery, Tissue Engineering, and Medical Implants: Research Developments, and Prospective Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, L.; Peña-Peña, J.; Alcantara-Quintana, L.; Olivares-Pinto, U.; Ruiz-Aguilar, C. Mechanical and In vitro evaluation of cell structures for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Valchanov, P.; Hristov, S.; Veselinov, D.; Gueorguiev, B. Management of Complex Acetabular Fractures by Using 3D Printed Models. Medicina 2022, 58, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enam, S.; Seng, G.H.; Ramlee, M.H. Patient-Specific Design of Knee and Ankle Implant: A Short Review on the Design Process, Analysis, Manufacturing, and Clinical Outcomes. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2024, 20, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.-H.; Pi, J.-K.; Zou, C.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Li, Q.-J.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Xing, F.; Nie, R.; Han, C.; Xie, H.-Q. Hydrogel-exosome system in tissue engineering: A promising therapeutic strategy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 38, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Sandler, N.; Willför, S.; Xu, C. Three-Dimensional Printing of Wood-Derived Biopolymers: A Review Focused on Biomedical Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5663–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Ma, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Xing, L.; Guo, Q.; Luo, D.; Weng, Z.; Ge, F.; Huang, Y.; et al. Characterization of excipients to improve pharmaceutical properties of sirolimus in the supercritical anti-solvent fluidized process. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 611, 121240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayubee, M.S.; Akter, F.; Ahmed, N.T.; Kabir, A.K.L.; Alam, L.; Hossain, M.M.; Kazi, M.; Islam, M.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, M.; et al. Chemical Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: A Comparative Study of Antibacterial Properties. Chem. Mater. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, T.C.; Amanah, A.Y.; Gluck, J.M. Electrospun Scaffolds and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes for Cardiac Tissue Engineering Applications. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemzadeh, G.; Jirofti, N.; Mehrjerdi, H.K.; Rajabioun, M.; Alamdaran, S.A.; Mohebbi-Kalhori, D.; Mirbagheri, M.S.; Taheri, R. A review on developments of in-vitro and in-vivo evaluation of hybrid PCL-based natural polymers nanofibers scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 52, 15280837221128314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-W.; Zhang, X.-W.; Mi, C.-H.; Qi, X.-Y.; Zhou, J.; Wei, D.-X. Recent advances in hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels for 3D bioprinting in tissue engineering applications. Smart Mater. Med. 2023, 4, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhang, W.; Gong, H.; Xu, K.; Luo, C.; Zhi, W.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Weng, J. Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan composite hydrogels with sustained release of traditional Tibetan medicine for promoting chronic diabetic wound healing. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 3821–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, E.B.; Amirul, A.A.; H.P.S., A.K.; Olaiya, N.G.; Iqbal, M.O.; Jummaat, F.; A.K., A.S.; Adnan, A.S. Insights into the Role of Biopolymer Aerogel Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Polymers 2021, 13, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Z.; Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Rehman, S.; Shah, S.; Hussain, S.; Ali, M.; Khan, M.; Raza, M.; Iqbal, M.; et al. Fundamentals of Nanotechnology. In Revolutionizing Agriculture: A Comprehensive Exploration of Agri-Nanotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P.; Nandi, A.; Adhikari, J.; Ghosh, A.; Seikh, A.H.; Ghosh, M. Current Progress and Future Perspectives of Biomaterials in 3D Bioprinting. In Advances in Additive Manufacturing; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sahebalzamani, M.; Ziminska, M.; McCarthy, H.O.; Levingstone, T.J.; Dunne, N.J.; Hamilton, A.R. Advancing bone tissue engineering one layer at a time: A layer-by-layer assembly approach to 3D bone scaffold materials. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 2734–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, M.; Mengqi, L.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Y. Comprehensive review of polyetheretherketone use in dentistry. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2025, 24, JPR_D_24_00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojio, K.; Nozaki, S.; Takahara, A.; Yamasaki, S. Influence of chemical structure of hard segments on physical properties of polyurethane elastomers: A review. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Paswan, K.K.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, V.; Sonker, M.; Khan, M.A.; Kumar, A.; Shreyash, N. Recent Advancements in Polyurethane-based Tissue Engineering. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdoz, J.C.; Johnson, B.C.; Jacobs, D.J.; Franks, N.A.; Dodson, E.L.; Sanders, C.; Cribbs, C.G.; Van Ry, P.M. The ECM: To scaffold, or not to scaffold, that is the question. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Luo, G.; Gelinsky, M.; Huang, P.; Ruan, C. 3D bioprinting scaffold using alginate/polyvinyl alcohol bioinks. Mater. Lett. 2017, 189, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaith, A.; Jain, N.; Kaul, S.; Nagaich, U. Polysaccharide-infused bio-fabrication: Advancements in 3D bioprinting for tissue engineering and bone regeneration. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddaszadeh, A.; Seddiqi, H.; Najmoddin, N.; Ravasjani, S.A.; Klein-Nulend, J. Biomimetic 3D-printed PCL scaffold containing a high concentration carbonated-nanohydroxyapatite with immobilized-collagen for bone tissue engineering: Enhanced bioactivity and physicomechanical characteristics. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 065029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Qiu, M.; Hwang, Y.-C.; Oh, W.-M.; Koh, J.-T.; Park, C.; Lee, B.-N. The Effects of 3-Dimensional Bioprinting Calcium Silicate Cement/Methacrylated Gelatin Scaffold on the Proliferation and Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Materials 2022, 15, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihemuti, A.; Zhang, H.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Q. 3D-printed fish gelatin scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 26, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. High-Strength and Injectable Supramolecular Hydrogel Self-Assembled by Monomeric Nucleoside for Tooth-Extraction Wound Healing. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-N.; Wang, X.; Yang, M.; Chen, Y.-R.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Deng, R.-H.; Zhang, Z.-N.; Yu, J.-K.; Yuan, F.-Z. Scaffold-based tissue engineering strategies for osteochondral repair. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 812383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majrashi, M.A.A.; Yahya, E.B.; Mushtaq, R.Y.; HPS, A.K.; Rizg, W.Y.; Alissa, M.; Alkharobi, H.; Badr, M.Y.; Hosny, K.M. Revolutionizing drug delivery: Exploring the impact of advanced 3D printing technologies on polymer-based systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 98, 105839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, L.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Empowering Precision Medicine: The Impact of 3D Printing on Personalized Therapeutic. Aaps Pharmscitech 2023, 24, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albisa, A.; Espanol, L.; Prieto, M.; Sebastian, V. Polymeric Nanomaterials as Nanomembrane Entities for Biomolecule and Drug Delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.; Ng, P.; Pinho, A.R.; Gomes, M.C.; Demidov, Y.; Krakor, E.; Grume, D.; Herb, M.; Lê, K.; Mano, J.; et al. Fabrication of antibacterial, osteo-inductor 3D printed aerogel-based scaffolds by incorporation of drug laden hollow mesoporous silica microparticles into the self-assembled silk fibroin biopolymer. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioumouxouzis, C.I.; Chatzitaki, A.-T.; Karavasili, C.; Katsamenis, O.L.; Tzetzis, D.; Mystiridou, E.; Bouropoulos, N.; Fatouros, D.G. Controlled Release of 5-Fluorouracil from Alginate Beads Encapsulated in 3D Printed pH-Responsive Solid Dosage Forms. Aaps Pharmscitech 2018, 19, 3362–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Recent advances in 3D printing hydrogel for topical drug delivery. MedComm–Biomater. Appl. 2022, 1, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H.; Dogan, N.O.; Yasa, I.C.; Musaoglu, M.N.; Kulali, Z.U.; Sitti, M. 3D printed personalized magnetic micromachines from patient blood–derived biomaterials. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh0273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykara, D.; Pilavci, E.; Ulag, S.; Okoro, O.V.; Nie, L.; Shavandi, A.; Koyuncu, A.C.; Ozakpinar, O.B.; Eroglu, M.; Gunduz, O. In vitro electrically controlled amoxicillin release from 3D-printed chitosan/bismuth ferrite scaffolds. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 193, 112105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Raza, A.; Ullah, M.; Hendi, A.A.; Akbar, F.; Khan, S.U.; Zaman, U.; Saeed, S.; Rehman, K.U.; Sultan, S.; et al. A Comprehensive Review: Epidemiological Strategies, Catheterization and Biomarkers used as a Bioweapon in Diagnosis and Management of Cardio Vascular Diseases. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Miao, S.; Esworthy, T.; Zhou, X.; Lee, S.-J.; Liu, C.; Yu, Z.-X.; Fisher, J.P.; Mohiuddin, M.; Zhang, L.G. 3D bioprinting for cardiovascular regeneration and pharmacology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 132, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, D.; Yi, H.; Est-Witte, S.; George, S.K.; Kengla, C.V.; Lee, S.J.; Atala, A.; Murphy, S.V. Bioprinted trachea constructs with patient-matched design, mechanical and biological properties. Biofabrication 2019, 12, 015022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, M.; Sarkar, A.; Singh, Y.P.; Derman, I.D.; Datta, P.; Ozbolat, I.T. Synergistic coupling between 3D bioprinting and vascularization strategies. Biofabrication 2023, 16, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.-D.; Hsu, S.-H. 4D bioprintable self-healing hydrogel with shape memory and cryopreserving properties. Biofabrication 2021, 13, 045029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Ivanovski, S. 3D bioprinted extracellular vesicles for tissue engineering—A perspective. Biofabrication 2022, 15, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetah, K.; Tebon, P.; Goudie, M.J.; Eichenbaum, J.; Ren, L.; Barros, N.; Nasiri, R.; Ahadian, S.; Ashammakhi, N.; Dokmeci, M.R.; et al. The emergence of 3D bioprinting in organ-on-chip systems. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 1, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, M.-J.; Plana, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Atta, L.; Achanta, A.; Yang, H.; Cramer, A.K.; Freake, J.; Sinha, M.S.; Yu, S.H.; et al. A Crisis-Responsive Framework for Medical Device Development Applied to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 617106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Yadav, S. Additive and Good Manufacturing Practices in Conformity Assessment. In Handbook of Quality System, Accreditation and Conformity Assessment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Adalbert, L.; Kanti, S.P.Y.; Jójárt-Laczkovich, O.; Akel, H.; Csóka, I. Expanding Quality by Design Principles to Support 3D Printed Medical Device Development Following the Renewed Regulatory Framework in Europe. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.L.; Turco, S.; Spina, F.; Costantino, A.; Visi, G.; Baronti, A.; Maiese, A.; Di Paolo, M. 3D printing and 3D bioprinting technology in medicine: Ethical and legal issues. Clin. Ter. 2023, 174, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J. Process attributes of goods, ethical considerations and implications for animal products. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, A.B.V.; Ballardini, R.M.; Mimler, M.; Li, P.; Salmi, M.; Minssen, T.; Gibson, I.; Mäkitie, A. Core Legal Challenges for Medical 3D Printing in the EU. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, E.A. Engineering the Microenvironment at the Protein-Hydrogel Interface to Investigate the Role of the Extracellular Matrix Protein Type in Single Cell Cardiomyocyte Structure and Function. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J. Clean bioprinting–Fabrication of 3D organ models devoid of animal components. ALTEX 2020, 38, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, C.; Camarero-Espinosa, S.; Baker, M.B.; Wieringa, P.; Moroni, L. Bioprinting: From Tissue and Organ Development to in Vitro Models. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10547–10607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, R.; Garg, A.; Deshmukh, R. A Snapshot of Current Updates and Future Prospects of 3D Printing in Medical and Pharmaceutical Science. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, A. The Use of Personalised 3D-Printed Cranio-Maxillofacial Implants in Future Healthcare, with a Focus on Reconstruction of Mandibular Continuity Defects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Wales, Newport, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Mu, M.; Yan, J.; Han, B.; Ye, R.; Guo, G. 3D printing materials and 3D printed surgical devices in oral and maxillofacial surgery: Design, workflow and effectiveness. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, M.; Mara, U.T.; Azlan, A.A.; Musa, N.N.S.M.; Arifin, S.S.; Mahmud, J. Compressive Failure Behaviour of Kevlar Epoxy and Glass Epoxy Composite Laminates Due to the Effect of Cutout Shape and Size with Variation in Fiber Orientations. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2022, 14, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olalla, Á.S.; Cerezo, J.L.; Abarca, V.R.; Soriano, L.R.; Mazzinari, G.; Torres, E.G. Impact of Raster Angle on 3D Printing of Poly (Lactic Acid)/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Blends: Effects on Mechanical and Shape Memory Properties. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar]

- Shuai, C.; Guo, W.; Wu, P.; Yang, W.; Hu, S.; Xia, Y.; Feng, P. A graphene oxide-Ag co-dispersing nanosystem: Dual synergistic effects on antibacterial activities and mechanical properties of polymer scaffolds. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimington, R.P.; Capel, A.J.; Christie, S.D.R.; Lewis, M.P. Biocompatible 3D printed polymers via fused deposition modelling direct C 2 C 12 cellular phenotype in vitro. Lab A Chip 2017, 17, 2982–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remington, L.A.; Goodwin, D. Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of the Visual System E-Book: Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of the Visual System E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S.V.; Atala, A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Hua, Y.; Zeng, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, D.; Zhou, G.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H. Bioprinting and regeneration of auricular cartilage using a bioactive bioink based on microporous photocrosslinkable acellular cartilage matrix. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 16, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdamadi, E.; Tashman, J.W.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Palchesko, R.N.; Feinberg, A.W. FRESH 3D Bioprinting a Full-Size Model of the Human Heart. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 6453–6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramiah, P.; du Toit, L.C.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kondiah, P.P.D.; Pillay, V. Hydrogel-Based Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting in Tissue Regeneration. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.M.; Lindsay, C.D.; Brunel, L.G.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Tashman, J.W.; Roth, J.G.; Myung, D.; Feinberg, A.W.; Heilshorn, S.C. 3D Bioprinting using UNIversal Orthogonal Network (UNION) Bioinks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 31, 2007983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Schwarz, B.; Forget, A.; Barbero, A.; Martin, I.; Shastri, V.P. Advanced Bioink for 3D Bioprinting of Complex Free-Standing Structures with High Stiffness. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Shiotsuki, M. Perspective Chapter: Design and Characterization of Natural and Synthetic Soft Polymeric Materials with Biomimetic 3D Microarchitecture for Tissue Engineering and Medical Applications. In Biomimetics-Bridging the Gap; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abert, A.A.; Akiah, M.-A. Preparation of Bioink for Hydrogel Printing in Additive Manufacturing. Malays. J. Compos. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 12, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özenler, A.K.; Yilmaz, E.; Koc, B.; Yildirim, E.D.; Yildiz, S.; Aydin, H.M.; Kose, G.T.; Demirbilek, M.; Gokce, A.; Akca, G.; et al. 3D bioprinting of mouse pre-osteoblasts and human MSCs using bioinks consisting of gelatin and decellularized bone particles. Biofabrication 2024, 16, 025027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashman, J.W.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Coffin, B.; Ruesch, A.; Lanni, F.; Kainerstorfer, J.M.; Feinberg, A.W. In situ volumetric imaging and analysis of FRESH 3D bioprinted constructs using optical coherence tomography. Biofabrication 2022, 15, 014102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magli, S.; Rossi, G.B.; Risi, G.; Bertini, S.; Cosentino, C.; Crippa, L.; Ballarini, E.; Cavaletti, G.; Piazza, L.; Masseroni, E.; et al. Design and Synthesis of Chitosan—Gelatin Hybrid Hydrogels for 3D Printable in vitro Models. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, P.; Singh, R.; Mahto, S.K. FRESH-based 3D bioprinting of complex biological geometries using chitosan bioink. Biofabrication 2024, 16, 045007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, A.; Mukasheva, F.; Moazzam, M.; Sultanova, D.; Abdikhan, B.; Trifonov, A.; Akilbekova, D. Dual-Crosslinking of Gelatin-Based Hydrogels: Promising Compositions for a 3D Printed Organotypic Bone Model. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Abedi-Dorcheh, K.; Vaziri, A.S.; Kazemi-Aghdam, F.; Rafieyan, S.; Sohrabinejad, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Adib, F.R.; Ghasemi, Z.; Klavins, K.; et al. A Review of Recent Advances in Natural Polymer-Based Scaffolds for Musculoskeletal Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2022, 14, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, N.; Yazdi, I.K.; Nabavinia, M.; Gemma, A.; Fanelli, A.; Caizzone, A.; Ptaszek, L.M.; Sinha, I.; Khademhosseini, A.; Ruskin, J.N.; et al. Patient-Specific Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, e1701347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | Polymers | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Chitosan | Non-toxicity; biocompatibility; biodegradability | Poor mechanical properties | [37,38] |

| Cellulose | Adhesive and bioactive; abundant and biodegradable | Mechanical stability lost during processing | [39] | |

| Alginate | Ease of use for 3D printing; rapid gelation with divalent cations | Poorly adhesive; may damage cells during printing | [40] | |

| Collagen | Adhesive and bioactive; abundant and biodegradable; tolerant of functionalization | Mechanically weak; contamination can lead to immunogenicity | [41,42] | |

| Dextran | Cost-effective; biocompatibility | Low reproducibility due to variations in composition | [43,44] | |

| Synthetic | Polylactic acid (PLA) | Degradable by hydrolysis; properties dependent on monomer feedstock | Hydrolysis products may cause inflammation; physically cross-linked gels are weak | [45,46] |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Degradable by hydrolysis; stable hydrogels over wide concentration range | Insufficient mechanical strength: crystallinity may slow hydrolysis beyond relevant timeframe | [47,48] | |

| Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | High elasticity; high biocompatibility and hydrophilicity | Non-degradable; non-adhesive | [49] | |

| Poly β-amino ester (PBAE) Polyethylene glycol (PEG) Polyvinyl pyrrolidine (PVP) | Biocompatibility; biodegrability; tunable chemistry; ease of synthesis Hydrophilicity; biocompatibility; controlled drug release Biocompatibility; non-toxicity | Limited structural variability; degradation affected by pH High concentrations required for drug delivery Viscosity adjustment required; thermally unstable at high temperatures | [50,51,52,53] |

| Bioink Composition | Cross-Linking Method | Mechanical Properties | Target Tissue | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate–Gelatin | Ionic cross-linking (calcium ions) | Moderate stiffness; bioactive | Cartilage; bone | [146] |

| Chitosan–Silk | Chemical cross-linking (glutaraldehyde) | High tensile strength; moderate flexibility | Skin; cartilage | [147] |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photopolymerization (UV light) | Adjustable stiffness; high biocompatibility | Cartilage; vascular structures | [148] |

| Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM)—Gelatin | Solvent evaporation (non-crosslinked) | Variable viscosity; low tensile strength | Liver; cardiac tissues | [149] |

| Alginate Dialdehyde | Chemical cross-linking (transglutaminase) | Moderate, adjustable; adhesion-enhancing | Bone; skin | [150] |

| Hyaluronic Acid–Fibrin | Ionic cross-linking (calcium ions) | Soft and flexibility; promotes cell adhesion | Cartilage; muscle | [151] |

| Keratin–Glycol Chitosan | Chemical cross-linking (methacrylation) | Moderate stiffness; good biocompatibility | Skin; connective tissues | [147] |

| Methacrylated Hyaluronic Acid (MeHA) | Photopolymerization (UV light) | Tunable mechanical properties | Cartilage; vascular tissues | [152] |

| Biomaterials | Key Applications | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | 3D-Printed Face Implantations | PLA applications in developing face implants in reconstructive surgery with emphasis on patient outcomes and surgical accuracy. | [171] |

| Use of PLA in customized surgical guides and implants for facial surgery with improved integration with surrounding tissues. | [172] | ||

| PLA scaffolds in face implants aided complex reconstruction with improved outcomes. | [173] | ||

| Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK) | Personalized Cranial Implants | Formation of customized PEEK implants for cranioplasty, illustrating mechanical stability and patient-specific adjustments. | [174] |

| PEEK utilization in management of complex acetabular fractures to improve surgical results and accuracy. | [175] | ||

| Assessment of PEEK implants in total talus replacements with a focus on restoration of anatomical naturalness. | [176] | ||

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Drug Delivery Systems | PEG hydrogels as localized drug delivery systems for effective healing in tissue repair processes. | [177] |

| PEG formulations in bio-inks for the 3D printing of soft tissue scaffolds to enhance cell viability and function. | [54] | ||

| Regeneration of cartilage and drug delivery systems as an application of PEG hydrogels in clinical research. | [178] | ||

| Polyvinyl Pyrrolidone (PVP) | Drug Delivery and Stabilization of Nanoparticles | Nanoparticle stabilizing agent for the use as PVP in formulation of drugs to deliver prolonged release profiles. | [179] |

| Case studies clarifying applications of PVP in enlightening delivery effectiveness of therapeutics with the help of nanocarriers. | [180] | ||

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Tissue Engineering Scaffolds | PCL scaffold formation for engineering of bone tissue with improved cell adhesion and propagation in vitro and in vivo. | [181] |

| PCL mixed with biodegradable polymers use to form hybrid scaffolds for soft tissue engineering. | [182] | ||

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Bio-Inks and Hydrogel Applications | PVA in 3D printing to be used as bio-inks, improving mechanical properties and cell viability in tissue engineering applications. | [183] |

| Examples depicting PVA hydrogels in curing wounds and drug delivery systems. | [184] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aftab, M.; Ikram, S.; Ullah, M.; Khan, N.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.A.; Bakhtiyor o’g’li, R.B.; Qizi, K.S.S.; Erkinjon Ugli, O.O.; Abdurasulovna, B.M.; et al. Recent Trends and Future Directions in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9040129

Aftab M, Ikram S, Ullah M, Khan N, Naeem M, Khan MA, Bakhtiyor o’g’li RB, Qizi KSS, Erkinjon Ugli OO, Abdurasulovna BM, et al. Recent Trends and Future Directions in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(4):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9040129

Chicago/Turabian StyleAftab, Maryam, Sania Ikram, Muneeb Ullah, Niyamat Khan, Muhammad Naeem, Muhammad Amir Khan, Rakhmonov Bakhrombek Bakhtiyor o’g’li, Kamalova Sayyorakhon Salokhiddin Qizi, Oribjonov Otabek Erkinjon Ugli, Bekkulova Mokhigul Abdurasulovna, and et al. 2025. "Recent Trends and Future Directions in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 4: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9040129

APA StyleAftab, M., Ikram, S., Ullah, M., Khan, N., Naeem, M., Khan, M. A., Bakhtiyor o’g’li, R. B., Qizi, K. S. S., Erkinjon Ugli, O. O., Abdurasulovna, B. M., & Qizi, O. K. A. (2025). Recent Trends and Future Directions in 3D Printing of Biocompatible Polymers. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(4), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9040129