Fundamentals of Cooling Rate and Its Thermodynamic Interactions in Material Extrusion

Abstract

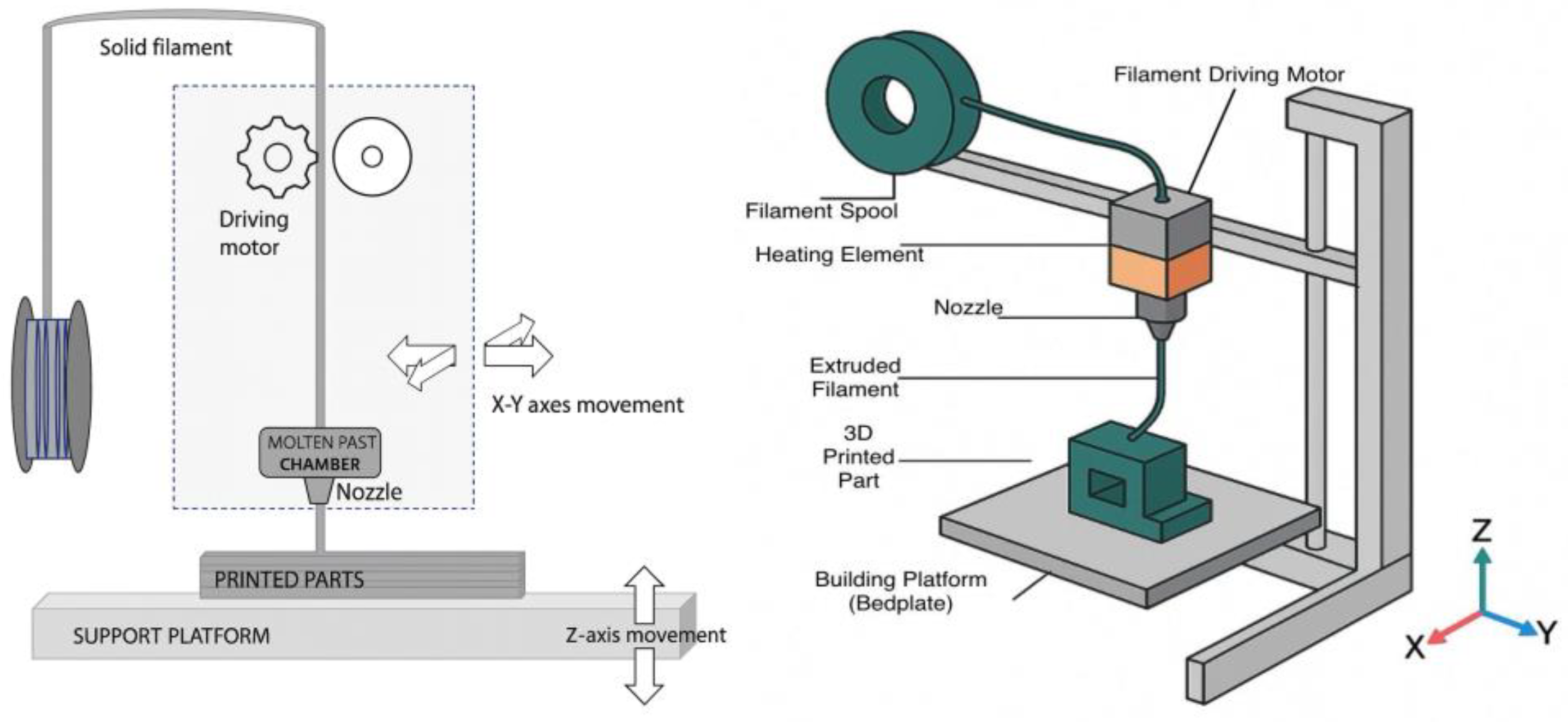

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of Cooling Rates in ME

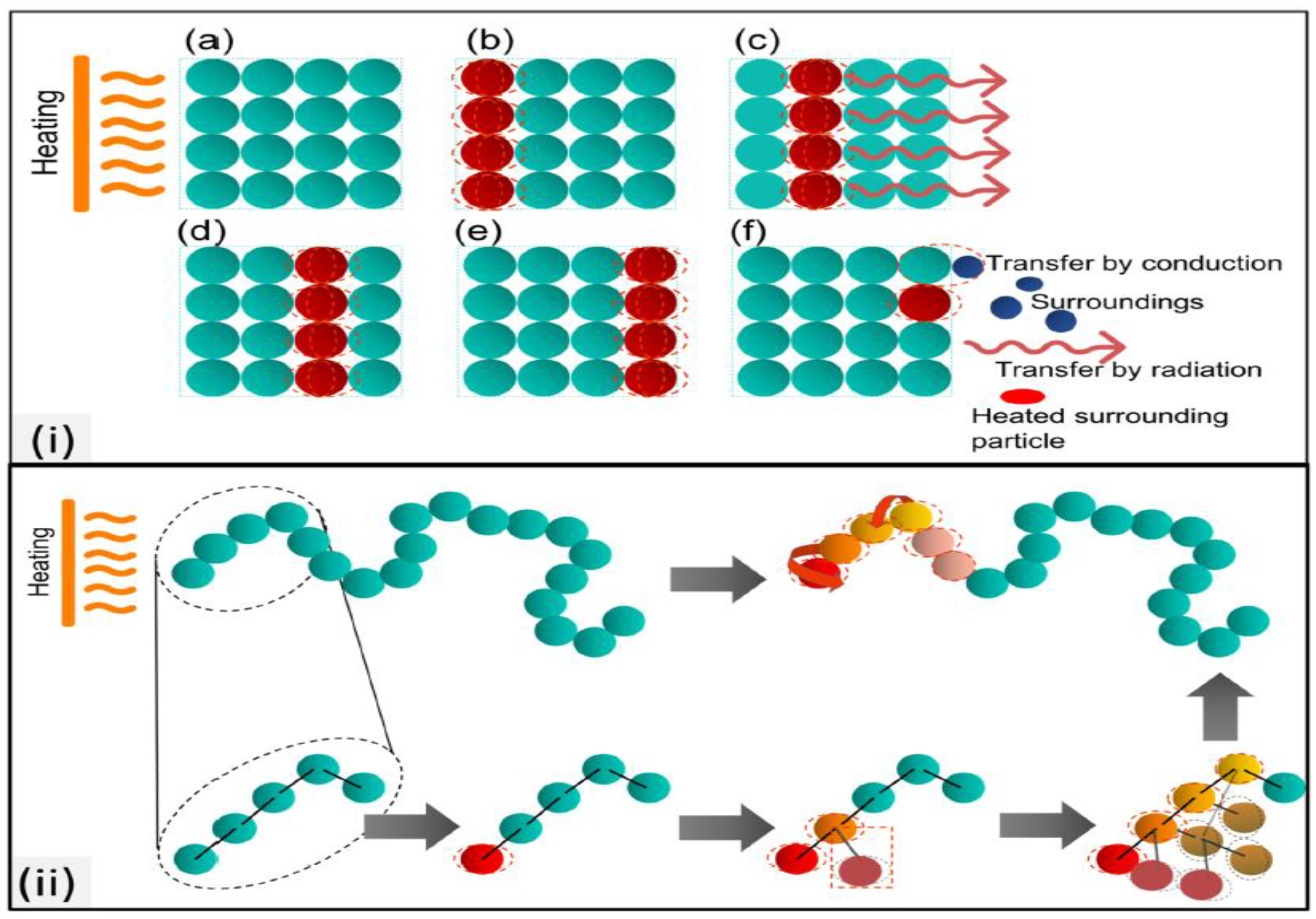

2.1. Heat Transfer Mechanisms

2.1.1. Conduction

2.1.2. Convection

2.1.3. Radiation

2.2. Key Factors Influencing Cooling Rates

2.2.1. Material Thermal Properties

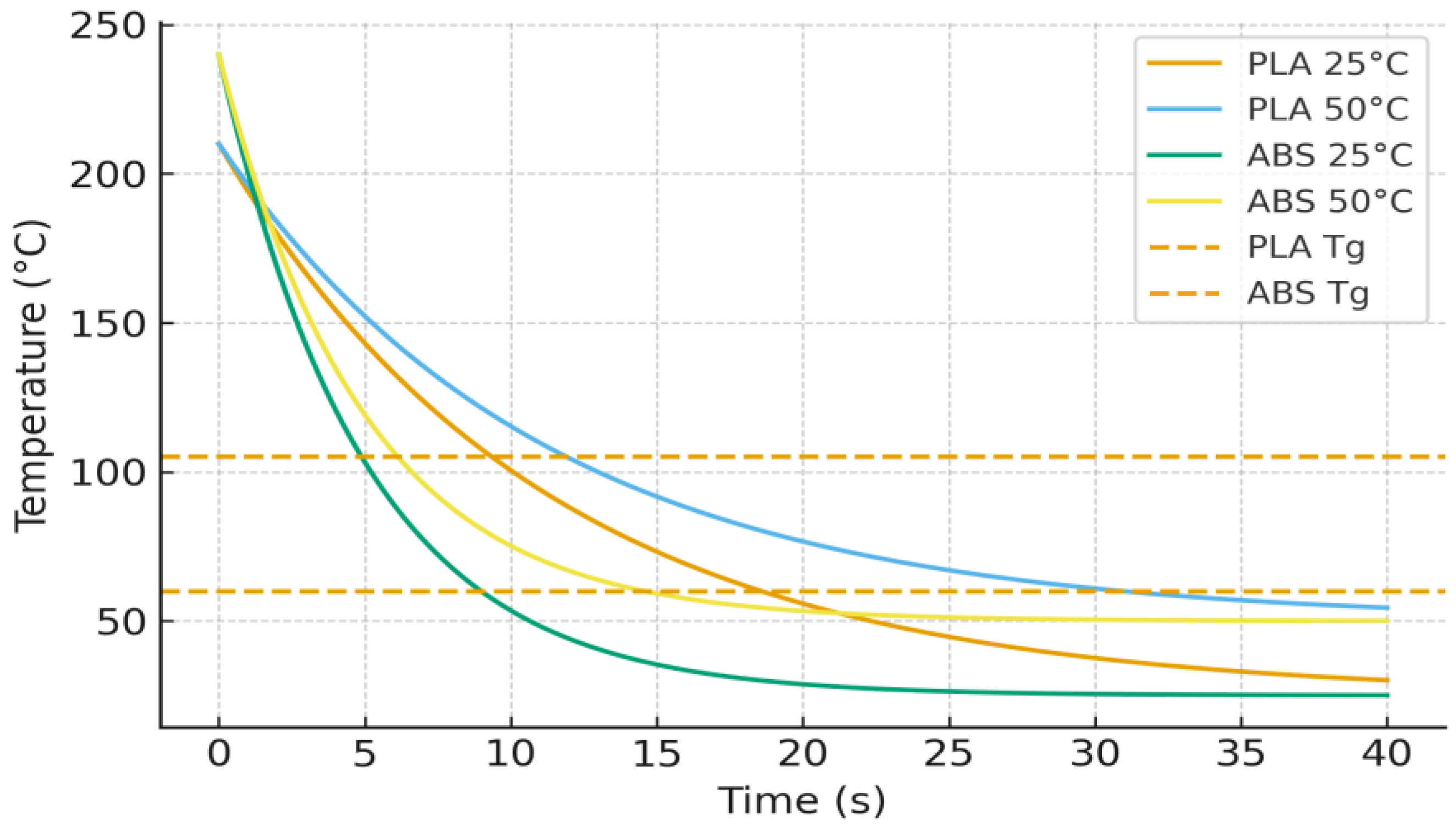

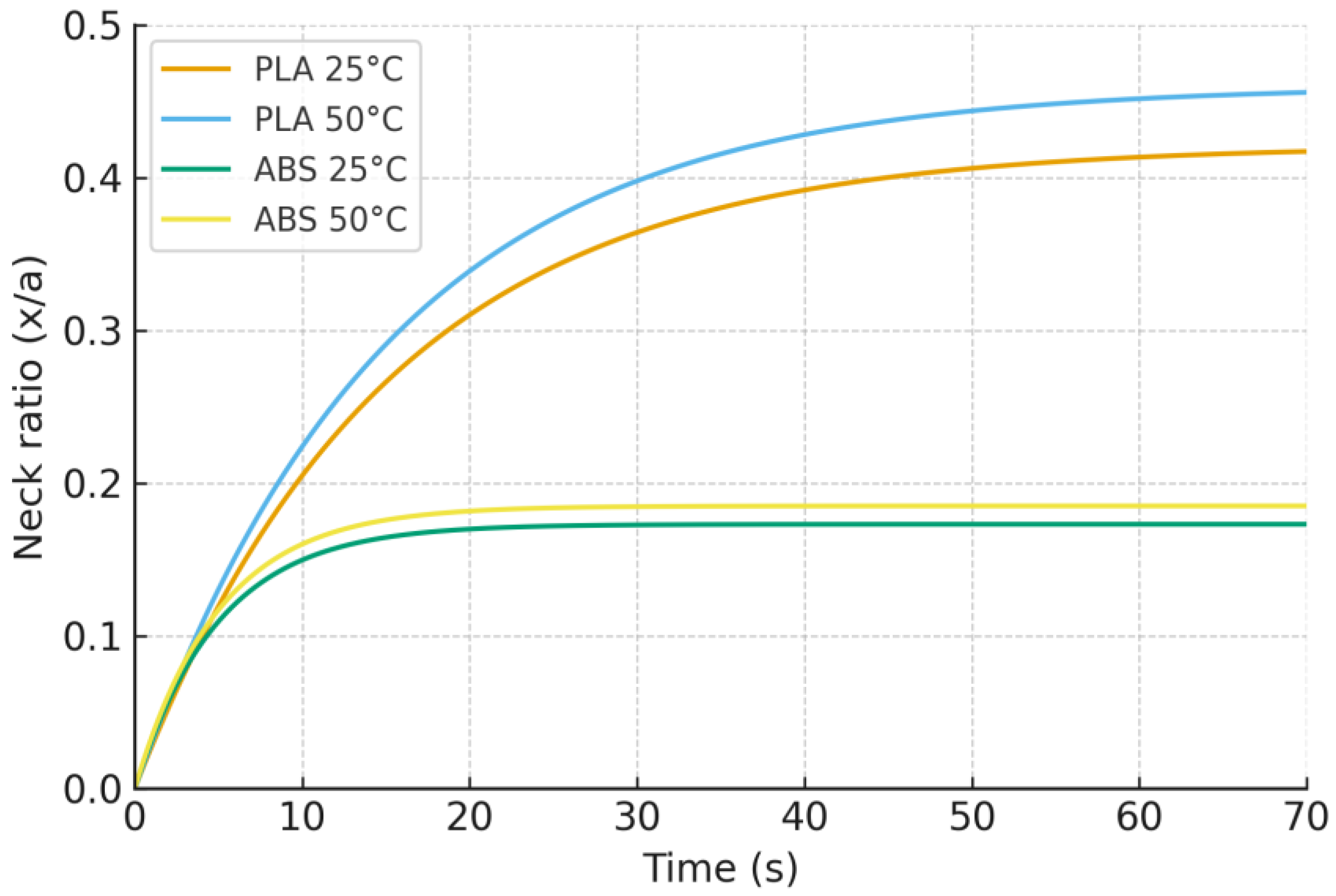

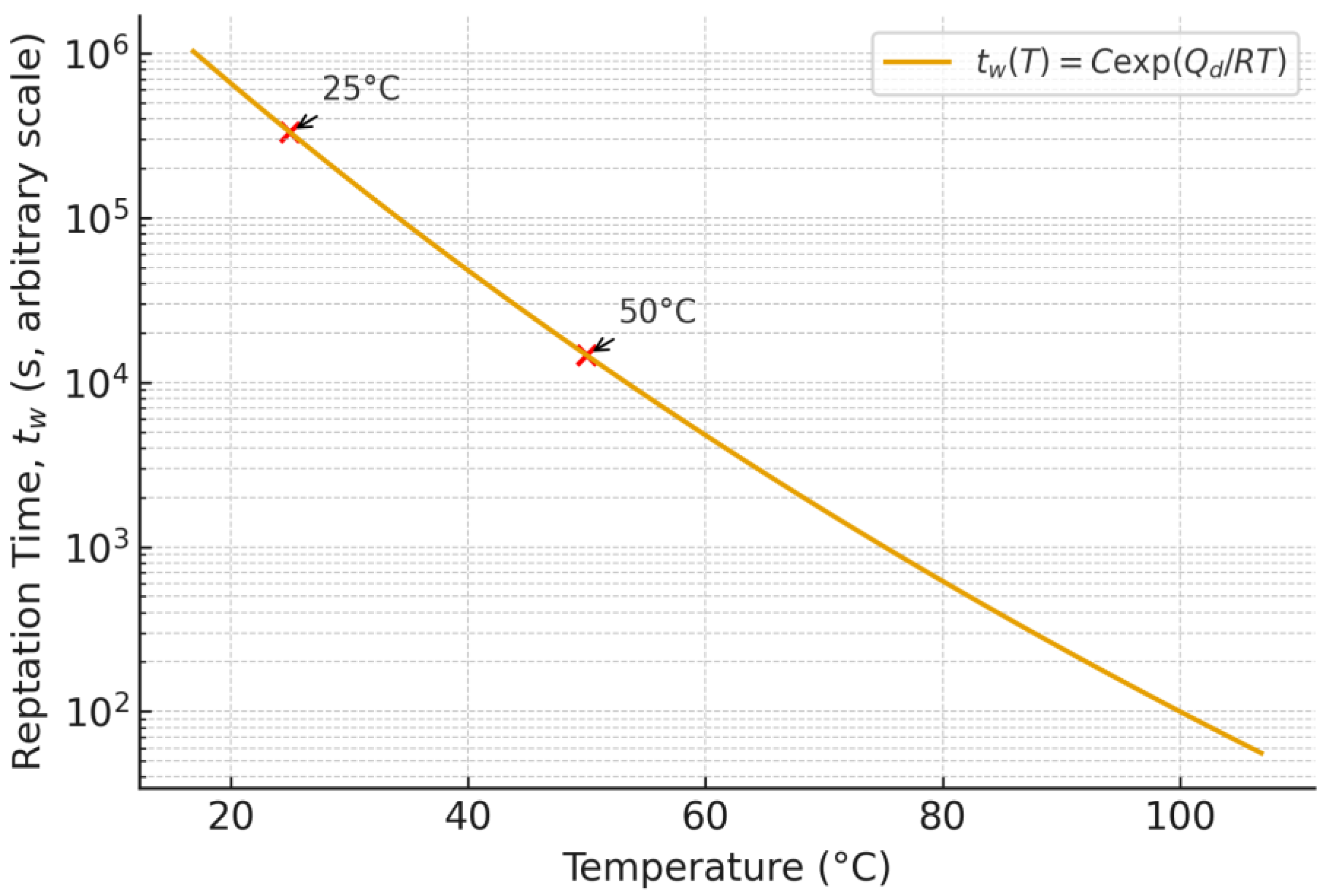

- The glass transition temperature (Tg) is a temperature range where the polymer transitions from a rigid, glassy, and often brittle state to a more flexible, rubbery, or pliable state. Unlike the melting point (Tm), where a crystalline material changes from a solid to a viscous liquid, the glass transition is a transition in the material’s mechanical properties, not a complete phase change [16]. The melting temperature, typically 20–50 °C above Tg for amorphous polymers like ABS, dictates the nozzle temperature required to achieve optimal viscosity for extrusion. In comparison, semi-crystalline polymers such as PEEK require precise control of Tm (≈343 °C) to prevent degradation [11]. Therefore, Tg is a fundamental material property that heavily influences thermoplastic behaviour during and after the FDM 3D printing process [11]. Because all surfaces that are in contact should be above the Tg to perform the adhesion process [16].

- Thermal conductivity (k), which usually ranges from 0.1–0.3 (W·m−1·K−1) for most polymers, regulates heat dissipation from the freshly extruded filament into the underlying substrate or the adjacent filament. Therefore, it is directly affecting the microstructure of the layers as well as influencing the cooling behaviour [26]. Because low k values contribute to thermal gradients, increasing residual stresses and warping due to uneven contraction during cooling, particularly in large prints [34].

- Specific heat capacity (Cp), representing the energy required to raise a material’s temperature, influences the energy input necessary to achieve phase transitions [31]. It plays a critical role in the thermal management and process stability of FDM. Polymers with higher Cp, such as PLA ≈ 1.8 J·g−1·K−1, demand greater thermal energy for melting compared to ABS ≈ 1.3 J·g−1·K−1, which necessitates adjustments in nozzle heating power and extrusion rates to maintain consistent melt flow [11]. This property also governs the cooling dynamics of deposited layers, where materials with elevated Cp retain heat longer, resulting in slow solidification and promoting interlayer molecular diffusion, which enhances bond strength but risks deformation if cooling is insufficient [34].

- The coefficient of thermal expansion (α) expresses the material’s tendency to change in length or volume for each degree of temperature change. In ME processes, this thermally driven deformation strongly influences dimensional stability, contributes to the build-up of residual stresses, and affects the final geometric accuracy of printed parts [11]. Polymers such as acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and polylactic acid (PLA) exhibit α values ranging from 60–200 µm·m−1·K−1, whereas in semi-crystalline polymers like PEEK demonstrate anisotropic expansion due to crystallinity gradients [36]. High α values exacerbate residual stresses as uneven cooling rates between adjacent layers induce differential contraction, leading to warping, interfacial delamination, or interlayer cracking [37]. For instance, ABS (α ≈ 90–110 µm·m−1·K−1) is more prone to warping than PLA (α ≈ 60–70 µm·m−1·K−1), necessitating heated build plates to minimize thermal gradients and adhesion loss [37]. In semi-crystalline polymers, α is further complicated by crystallization kinetics. During cooling, regions of crystallinity contract more than amorphous domains, amplifying internal stresses and distorting part geometry. This necessitates precise control of bed temperature and cooling rates to regulate crystallization and mitigate dimensional inaccuracies [38].

2.2.2. Effect of Process Parameters on Cooling Rate

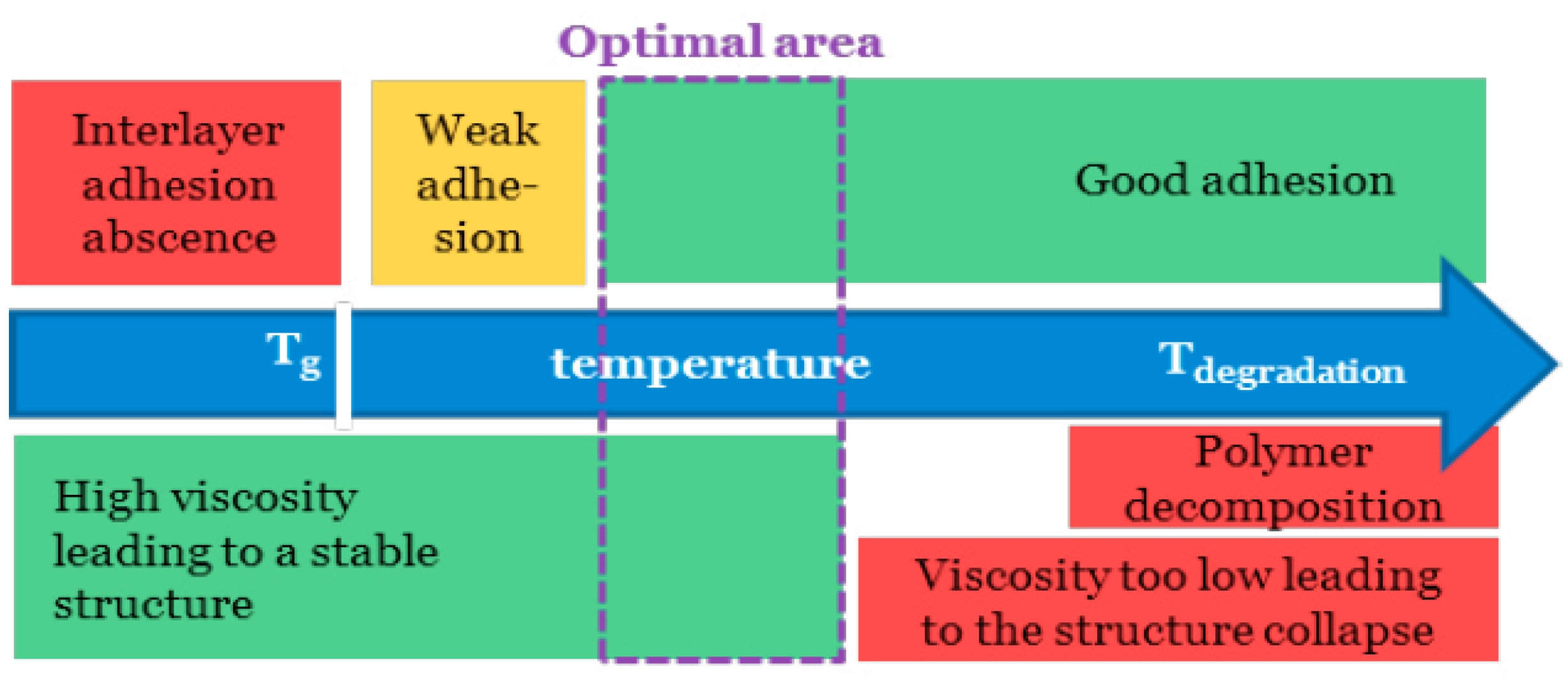

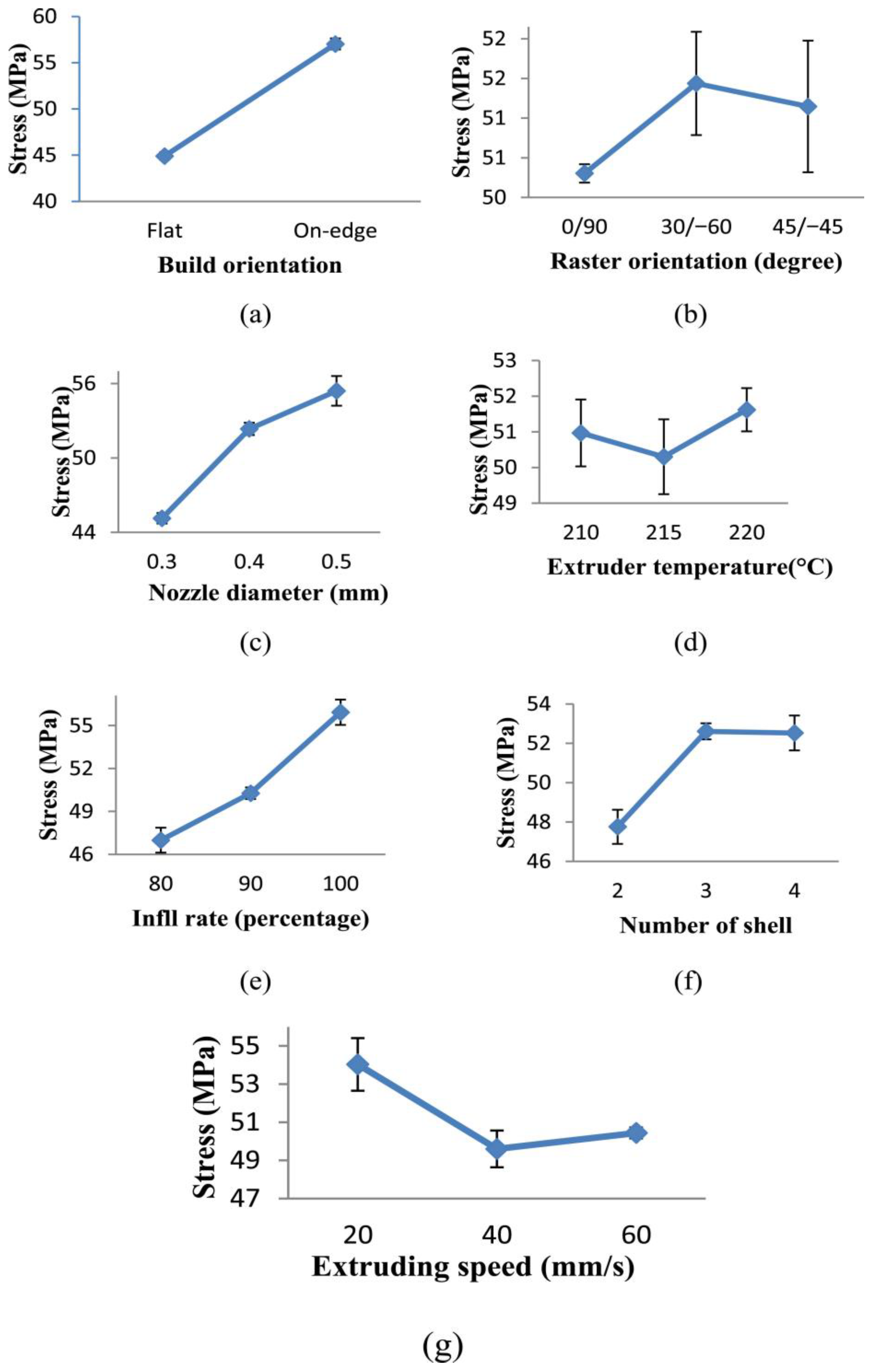

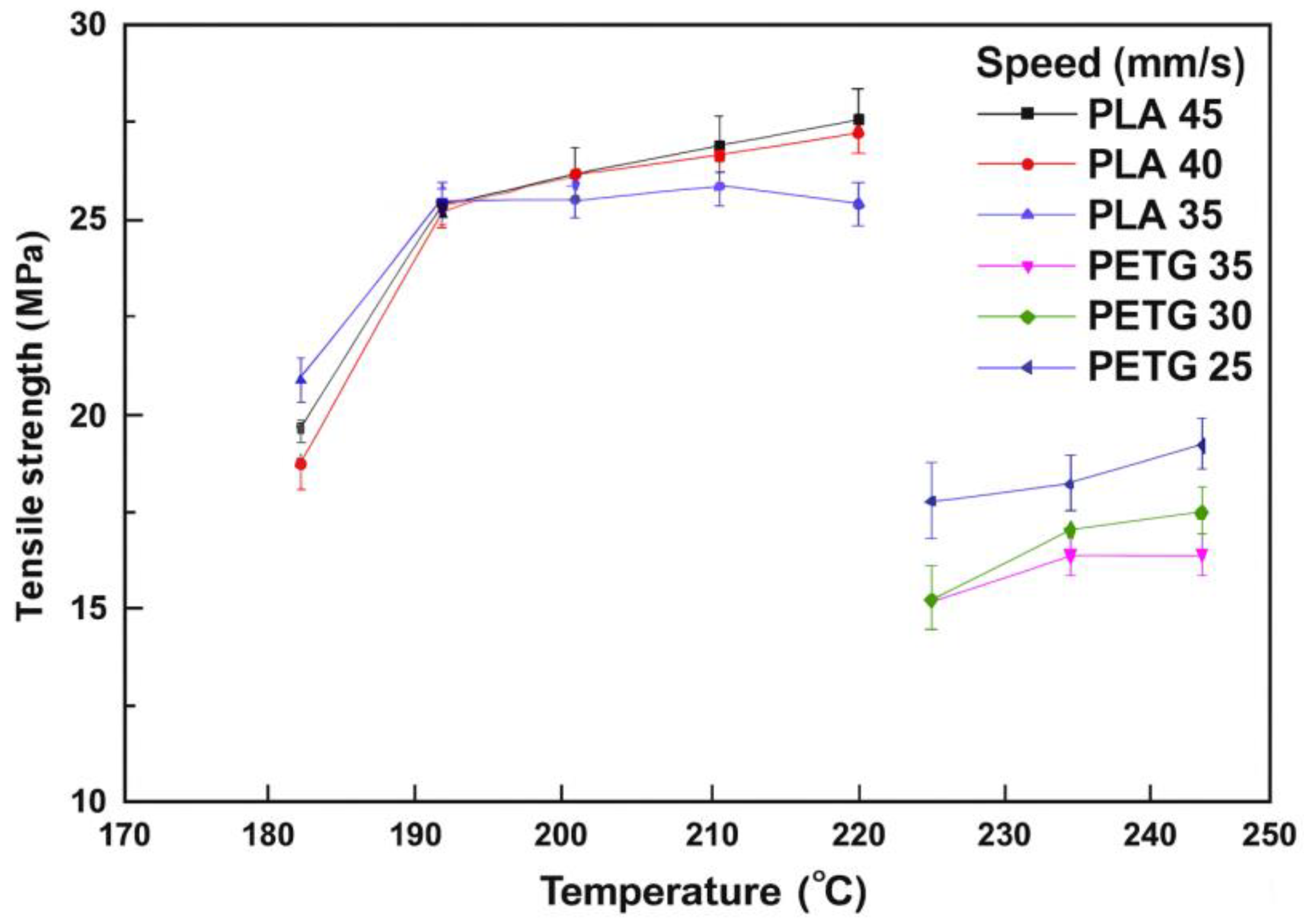

- The extrusion temperature significantly impacts the cooling rate by determining the initial thermal state of the deposited material. Higher extrusion temperatures increase the material’s fluidity, allowing for better layer adhesion but requiring longer cooling periods. Conversely, lower temperatures may lead to faster solidification but can compromise layer bonding [39]. The optimal temperature depends on the specific material properties, such as glass transition temperature and melt flow index, as shown in Figure 5. For instance, PLA typically requires lower extrusion temperatures (180–220 °C) compared to ABS (220–250 °C), affecting their respective cooling behaviours [40].

- The bedplate temperature affects the cooling rate, particularly for the initial layers of the print. A heated build plate helps maintain the first layers at an elevated temperature, promoting better adhesion and reducing warping. However, it also slows the cooling rate of these layers [41]. The temperature gradient between the bedplate and the upper layers influences the overall cooling behaviour and internal stresses in part [42]. Different materials often require specific build plate temperatures for optimal results [43].

- Print speed influences the cooling rate by determining the time interval between successive layer depositions. While higher print speeds shorten the deposition cycle and reduce the time available for each layer to cool before the next one is applied, and the slower print speeds do the opposite, the actual inter-layer delay is also strongly dependent on the printed geometry. Larger cross-sectional areas, complex contours, or long tool-paths inherently extend the deposition time for a single layer, even at a constant print speed, thereby modifying the cooling window experienced by the material. Conversely, smaller or simpler geometries result in shorter toolpaths, resulting in shorter cooling intervals. These combined effects govern the accumulation or dissipation of heat within the part, influencing deformation phenomena such as warping and dimensional inaccuracy. Accordingly, the optimal print speed represents a balance between productivity and thermal control, and its effectiveness is closely linked to the geometric characteristics of the printed component [22,44].

- Layer height affects the cooling rate through its impact on thermal mass and heat transfer. Thinner layers have less thermal mass and thus cool more quickly than thicker layers [45]. Additionally, thinner layers allow for more efficient heat transfer to the surrounding environment due to their increased surface area-to-volume ratio [33]. However, very thin layers may lead to longer print times and potential issues with material flow [46].

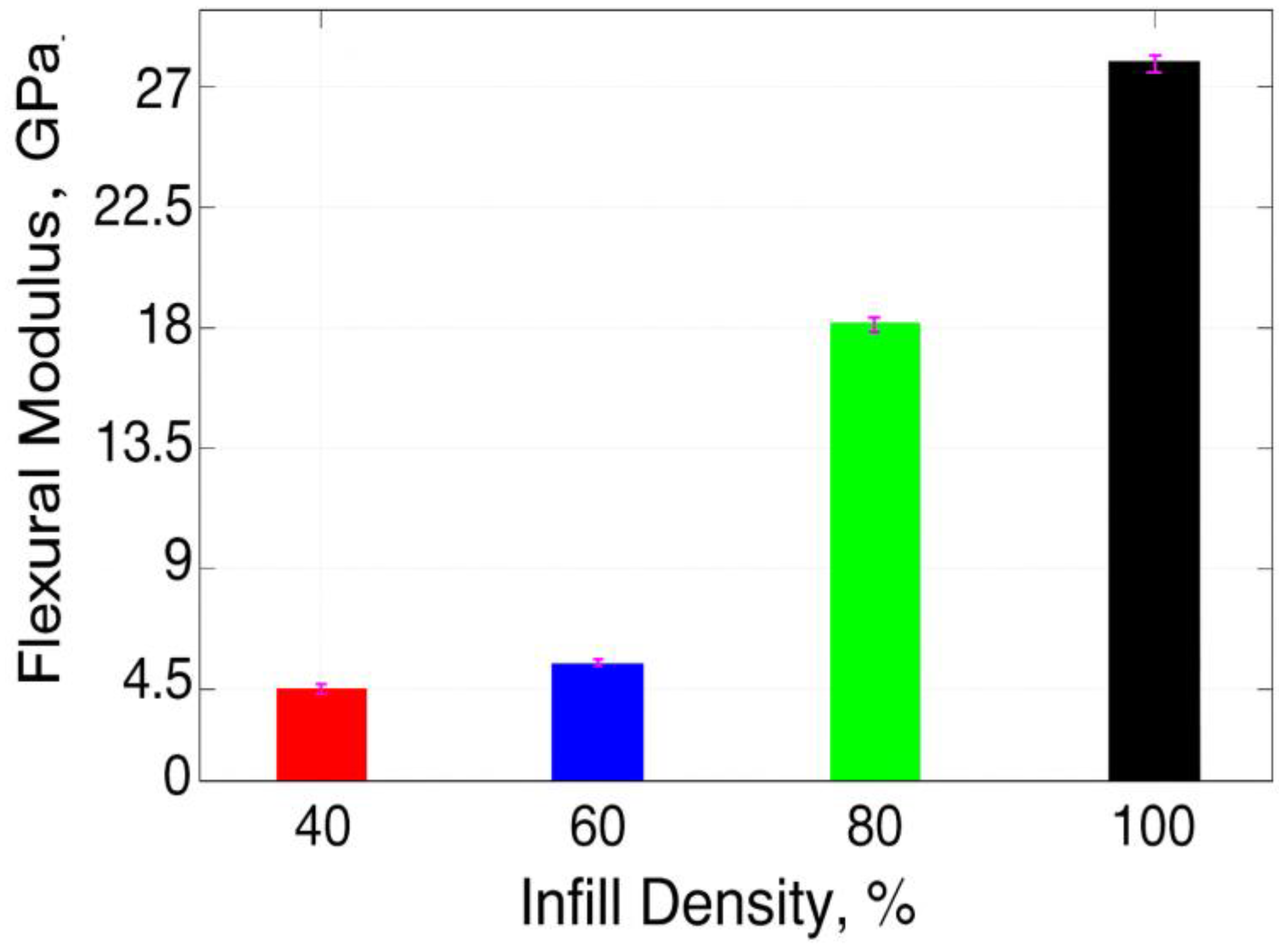

- Higher infill densities result in increased thermal mass within the printed part. This larger volume of material retains heat for longer periods, potentially slowing down the overall cooling rate [45]. Conversely, lower infill densities lead to reduced thermal mass, allowing for more rapid cooling. Also, the infill pattern and density affect heat distribution throughout the printed part [26]. Higher densities can lead to more uniform heat distribution, which may result in more consistent cooling rates across the object [35]. Lower densities, especially with certain infill patterns, can create air pockets that act as insulation, potentially leading to uneven cooling [22].

2.2.3. Geometry

2.3. Mathematical Background for the Cooling Rates

3. Role of Cooling Rate in FDM

3.1. Cooling Rate Effect on Crystallinity and Microstructural Morphology

3.2. Cooling Rate Effect on Defect Formation

3.2.1. Warping Mechanisms

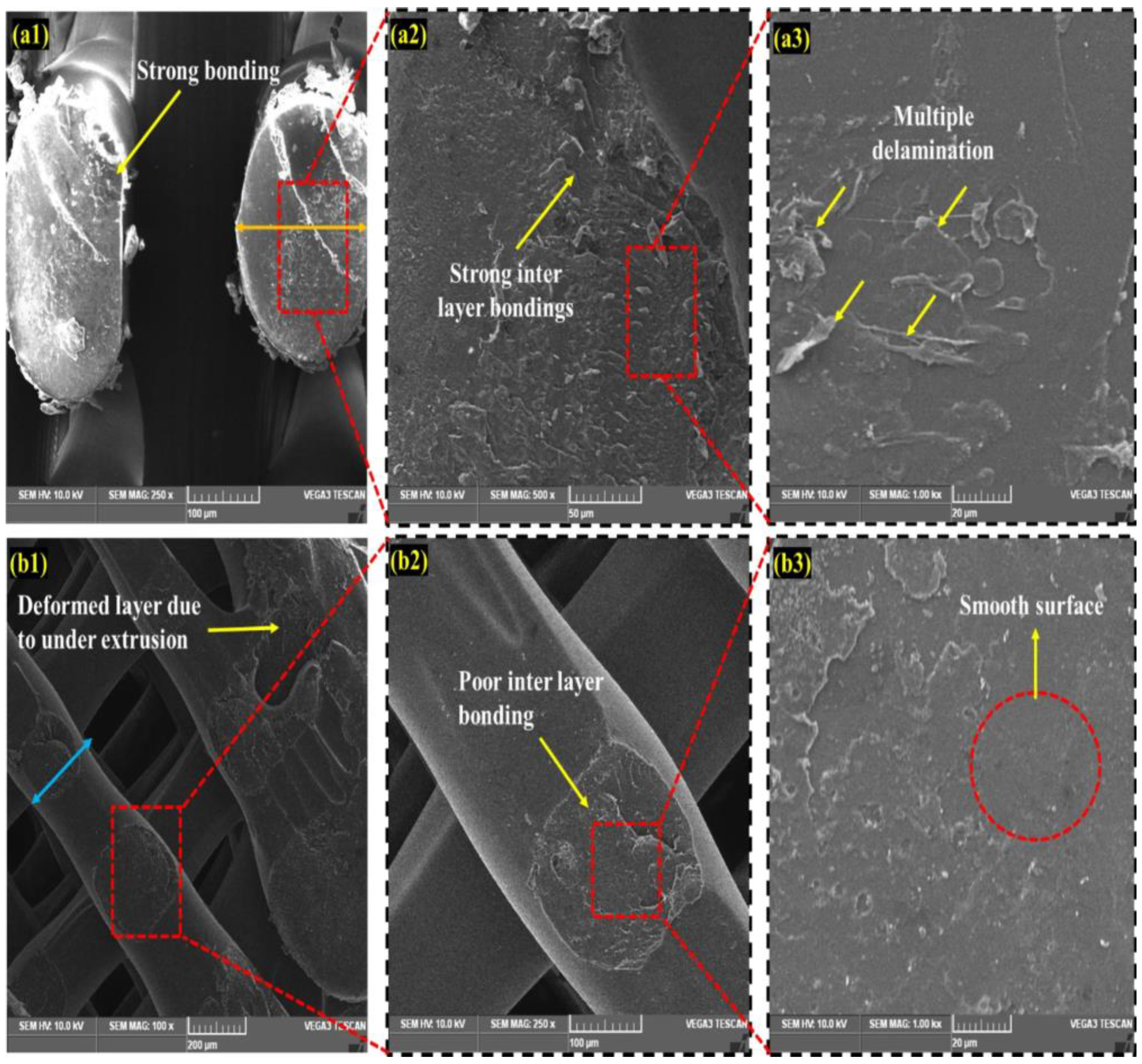

3.2.2. Delamination and Interlayer Bonding

3.2.3. Residual Stress Accumulation

4. Previous Work and Research on FDM Process Parameter Optimization and Its Interactions with Cooling Rate

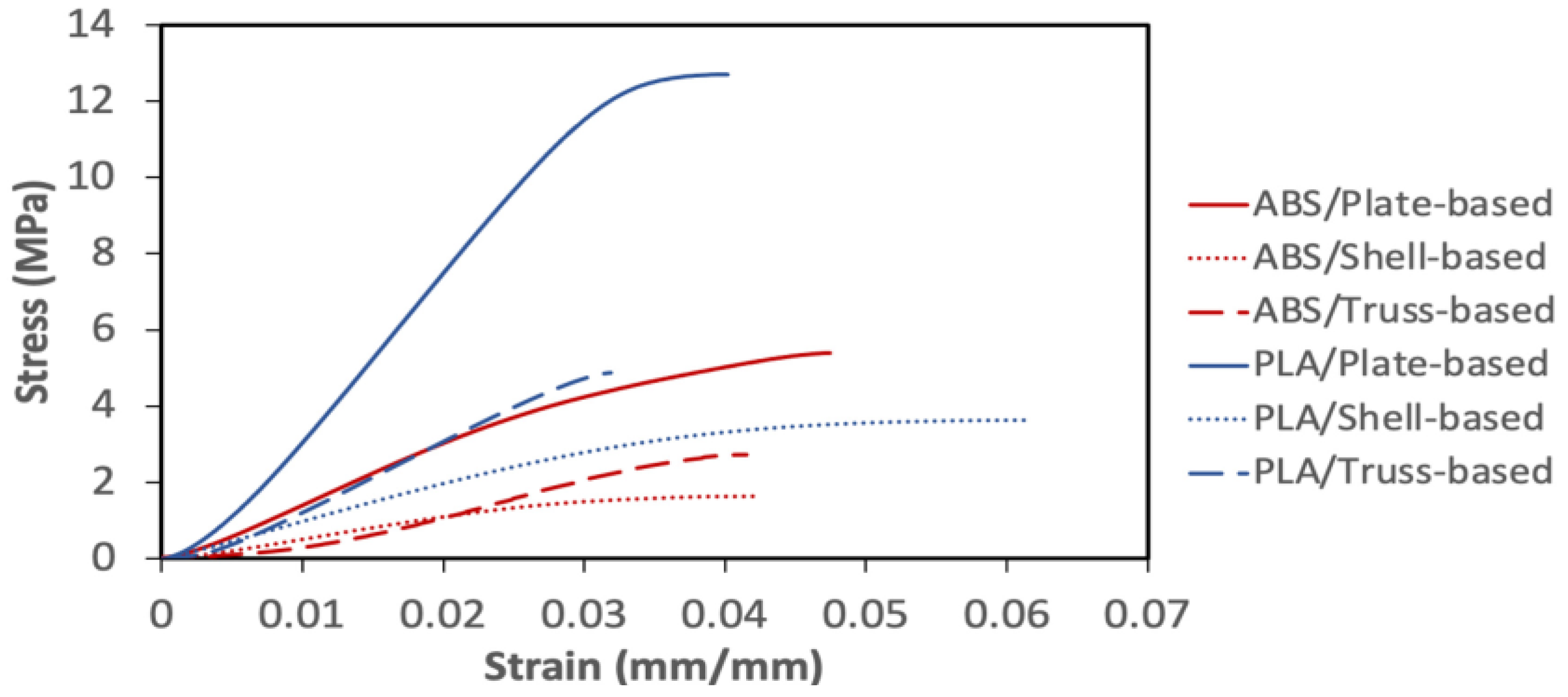

4.1. Polylactic Acid (PLA)

4.2. Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS)

4.3. Other Polymers

5. Cooling Rate Mechanism & Quantitative Characterization Methods

- Embedded thermocouples: They are positioned at the part/bed interface or between designated layers to record local time–temperature histories throughout the build. By capturing the full heating–cooling cycle—including reheating from subsequent layer deposition—they provide direct insight into thermal gradients, melt reheating behaviour, and layer-wise cooling rates. Such measurements have reported cooling rates ranging from only a few °C/s to hundreds of °C/s in polymer-quenching and material-extrusion studies [30,94]. However, several limitations affect accuracy. Thermocouples have a finite response time (typically 100–140 ms), which can smear rapid thermal transients. Reliable measurements also require excellent thermal contact with the surrounding polymer; any voids or incomplete bonding can insulate the junction, causing systematic underestimation of true cooling rates. Additionally, the sensor’s physical presence may disturb the local thermal field, especially in small features or thin layers, introducing further uncertainty into the captured data [30,31,32].

- Infrared Thermography: IR thermography offers non-contact, full-field temperature measurements with frame rates in the tens of hertz and spatial resolution below 100 µm, enabling direct visualization of weld-zone temperatures, surface cooling rates, and spatial thermal gradients during extrusion. Because IR cameras detect radiated energy rather than true temperature, accurate use requires careful handling of surface emissivity, mitigation of reflections from nearby hot components, and calibration against reference temperatures to convert raw signals into reliable thermal fields [31,32]. IR approaches are especially valuable for revealing the spatial heterogeneity of cooling, capturing phenomena such as asymmetric heat dissipation, cooling fronts, and thermally influenced defect formation [30,94].

6. Critical Analysis and Discussion

7. Challenges in FDM Process Optimization

8. Gaps and Suggested Future Work

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Manuscript Preparation Process

Abbreviations

| ABS | Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BF | Basalt Fibre |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| Cp | Specific Heat Capacity |

| DIC | Digital Image Correlation |

| DLP | Digital Light Processing |

| DMLS | Direct Metal Laser Sintering |

| DoE | Design of Experiment |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| DSD | Definitive Screening Design |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modelling |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FESEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FFBPNN | Feedforward Backpropagation Neural Network |

| FFD | Fractional Factorial Design |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GRA | Gray Relational Analysis |

| k | Thermal Conductivity |

| L-PA | Low-Temperature Polyamide |

| ME | Material Extrusion |

| Micro CT | Microcomputed Tomography |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PA-CF | Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Nylon |

| PAPC-II | Polyamide–Polyolefin–Cellulose Composite |

| PEEK | Polyether Ether Ketone |

| PEI | Polyetherimide |

| PETG | Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| RBFNN | Radial Basis Function Neural Network |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| S/N | Signal-to-Noise |

| SAEA | Surrogate-Assisted Evolutionary Algorithm |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| SLJs | Single Lap Joints |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

| Tcc | Cold Crystallization Temperature |

| Tg | Glass Transition Temperature |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| UTS | Ultimate Tensile Strength |

| α | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion |

References

- He, F.; Thakur, V.K.; Khan, M. Evolution and new horizons in modelling crack mechanics of 3D printing polymeric structures. Mater. Today Chem. 2021, 20, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergene, B.; İnci, Y.E.; Çetintaş, B.; Daysal, B. An experimental study on the wear performance of 3D printed polylactic acid and carbon fibre reinforced polylactic acid parts: Effect of infill rate and water absorption time. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dixit, A.R.; Sreenivasa, S. Mechanical properties of additively manufactured polymeric composites using sheet lamination technique and fused deposition modelling: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofangchi, A.; Han, P.; Izquierdo, J.; Iyengar, A.; Hsu, K. Effect of ultrasonic vibration on interlayer adhesion in fused filament fabrication 3D printed abs. Polymers 2019, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.J.; Sevvel, P.; Gunasekaran, J. A review on the various processing parameters in fdm. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 37, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faes, M.; Ferraris, E.; Moens, D. Influence of inter-layer cooling time on the quasi-static properties of abs components produced via fused deposition modelling. Procedia CIRP 2016, 42, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. A study on fused deposition modeling (fdm) and laser-based additive manufacturing (lbam) in the medical field. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.A.; Shah, O.R.; Ghafoor, U.; Qureshi, Y.; Bhutta, M.R. Additive manufacturing of continuous fiber-reinforced polymer composites via fused deposition modelling: A comprehensive review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, D.; Patti, A. Fused deposition modelling (fdm) of thermoplastic-based filaments: Process and rheological properties—An overview. Materials 2023, 16, 7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Babu, K.; Kannan, G.; Mensah, R.A.; Samantaray, S.K.; Das, O. The thermal properties of fdm printed polymeric materials: A review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 225, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Yodo, N. A systematic survey of fdm process parameter optimization and their influence on part characteristics. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Mishra, V.; Negi, S. An overview of research on fff based additive manufacturing of polymer composite. In Recent Advancements in Mechanical Engineering; ICRAMERD 2022, Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jaisingh Sheoran, A.; Kumar, H. Fused deposition modeling process parameters optimization and effect on mechanical properties and part quality: Review and reflection on present research. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 21, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H.; Chen, Q.; Advincula, R.C. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed polymers. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 20, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyan, M.; Amu-Darko, J.N.O.; Issaka, E.; Abban, O.J. Advances in fused deposition modeling on process, process parameters, and multifaceted industrial application: A review. J. Phys. Commun. 2024, 6, 012401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Yüksel, C. A comparative analysis of printing parameter effects of tensile and flexural specimens produced with two different printers by the taguchi method. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaei, H.R.; Khelladi, S.; Deligant, M.; Shirinbayan, M.; Tcharkhtchi, A. Numerical prediction for temperature profile of parts manufactured using fused filament fabrication. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 76, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, N. Investigating the material properties and microstructural changes of fused filament fabricated pla and tough-pla parts. Polymers 2021, 13, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.M.; Xi, J.T.; Jin, Y. A model research for prototype warp deformation in the fdm process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 33, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, J.; Zaoutsos, S. Effects of 3D-printing processing parameters on fff parts’ porosity: Outlook and trends. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2024, 39, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancy, C.K. Influence of Thermal Gradient on Mechanical Properties in Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Additive Manufacturing. Master’s Thesis, A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Rizvi, G.M.; Bellehumeur, C.T.; Gu, P. Effect of processing conditions on the bonding quality of fdm polymer filaments. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2008, 14, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoivre, A.; Boyard, N.; Levy, A.; Sobotka, V. Heat transfer and adhesion study for the fff additive manufacturing process. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 47, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.F.; Duarte, F.M.; Covas, J.A. Thermal conditions affecting heat transfer in fdm/ffe: A contribution towards the numerical modelling of the process. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2015, 10, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekmes, I.A.; Kochetov, R.; Morshuis, P.H.F.; Smit, J.J. Thermal conductivity of polymeric composites: A review. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Solid Dielectrics (ICSD), Bologna, Italy, 30 June–4 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A.P. Polymer crystallinity determinations by dsc. Thermochim. Acta 1970, 1, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebewele, R.O. Polymer Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 1–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kanbur, B.B.; Markussen, W.B.; Duan, F.; Seat, M.H.; Kærn, M.R. Experimental indirect cooling performance analysis of the metal 3D-printed cold plates with two different supporting elements. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 148, 107046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Lynch, S.P.; Meisel, N.A. Heat transfer simulation of material extrusion additive manufacturing to predict weld strength between layers. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janna, W.S. Engineering Heat Transfer, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; pp. 1–750. [Google Scholar]

- Cosson, B.; Asséko, A.C.A.; Pelzer, L.; Hopmann, C. Radiative thermal effects in large scale additive manufacturing of polymers: Numerical and experimental investigations. Materials 2022, 15, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Van Hooreweder, B.; Ferraris, E. T4f3: Temperature for fused filament fabrication. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.N.; Strong, R.; Gold, S.A. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: I. process design and modeling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, T.; Jin, X.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Temperature analyses in fused filament fabrication: From filament entering the hot-end to the printed parts. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 9, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsika-Klossa, C.; Chatzidai, N.; Kousiatza, C.; Karalekas, D. Characterization of thermal expansion coefficient of 3D printing polymeric materials using fiber bragg grating sensors. Materials 2024, 17, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, B.; Postole, M.; Teodorescu-Drăghicescu, H.; Alexandru, H.; Constantin, G.; Răducanu, A.; Dănilă, M. Thermal expansion of plastics used for 3D printing. Polymers 2022, 14, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, J.L.; Kelly, P.G.; Jones, B.D.; Roy-Mayhew, J.D. Effects of coefficient of thermal expansion and moisture absorption on the dimensional accuracy of carbon-reinforced 3D printed parts. Polymers 2021, 13, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhattab, K.; Bhaduri, S.B.; Sikder, P. Influence of fused deposition modelling nozzle temperature on the rheology and mechanical properties of 3D printed β-tricalcium phosphate (tcp)/polylactic acid (pla) composite. Polymers 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiru, A.B.; Valencia, V.V.; Liu, D. Additive Manufacturing Handbook: Product Development for the Defense Industry, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–600. [Google Scholar]

- Rosli, A.A.; Shuib, R.K.; Ishak, K.M.K.; Hamid, Z.A.A.; Abdullah, M.K.; Rusli, A. Influence of bed temperature on warpage, shrinkage and density of various acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (abs) parts from fused deposition modelling (fdm). AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2267, 020072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaçoğlu-Turan, B.; Kırkköprü, K.; Çakan, M. Numerical modeling and analysis of transient and three-dimensional heat transfer in 3D printing via fused-deposition modeling (fdm). Computation 2024, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, E.; Napolitano, F.; Papa, I.; Squillace, A.; Astarita, A. Influence of the heated-bed material on pla mechanical properties and energy consumption in the fdm process. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 2443–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.A.; Kamil, M. Effect of print speed and extrusion temperature on properties of 3D printed pla using fused deposition modeling process. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 5462–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Liu, C.Y. The influence of forced-air cooling on a 3D printed pla part manufactured by fused filament fabrication. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 25, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Ardiansyah, R.; Rusita, L.; Larasati, I.L. Effect of layer thickness on flexural properties of pla (polylactid acid) by 3D printing. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1130, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armillotta, A.; Bellotti, M.; Cavallaro, M. Warpage of fdm parts: Experimental tests and analytic model. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2018, 50, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwania, F.; Maringa, M.; Nsengimana, J.; van der Walt, J.G. Investigating surfaces, geometry and degree of fusion of tracks printed using fused deposition modelling to optimise process parameters for polymeric materials at meso-scale. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2024, 30, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olleak, A.; Adcock, E.; Hinnebusch, S.; Dugast, F.; Rollett, A.D.; To, A.C. Understanding the role of geometry and inter-layer cooling time on microstructure variations in lpbf ti6al4v through part-scale scan-resolved thermal modeling. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 9, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benwood, C.; Anstey, A.; Andrzejewski, J.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Improving the impact strength and heat resistance of 3D printed models: Structure, property, and processing correlationships during fused deposition modeling (fdm) of poly(lactic acid). ACS Omega 2018, 3, 4400–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chou, K. A parametric study of part distortions in fused deposition modelling using three-dimensional finite element analysis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. B J. Eng. Manuf. 2008, 222, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipov, S.; Faragó, I. Implicit euler time discretization and fdm with newton method in nonlinear heat transfer modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.06337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Rizvi, G.M.; Bellehumeur, C.T.; Gu, P. Experimental study of the cooling characteristics of polymer filaments in fdm and impact on the mesostructures and properties of prototypes. In Proceedings of the 2003 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 4–6 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pokluda, O.; Bellehumeur, C.T.; Vlachopoulos, J. Modification of frenkel’s model for sintering. AIChE J. 1997, 43, 3253–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellehumeur, C.T.; Kontopoulou, M.; Vlachopoulos, J. The role of viscoelasticity in polymer sintering. Rheol. Acta 1998, 37, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellehumeur, C.; Li, L.; Sun, Q.; Gu, P. Modeling of Bond Formation Between Polymer Filaments in the Fused Deposition Modeling Process. J. Manuf. Process. 2004, 6, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Pitchumani, R. Healing of thermoplastic polymers at an interface under nonisothermal conditions. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 3213–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon-Hernandez, S.; Garcia-Gonzalez, D.; Jérusalem, A.; Arias, A. Design of FDM 3D Printed Polymers: An Experimental–Modelling Methodology for the Prediction of Mechanical Properties. Mater. Des. 2020, 188, 108414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymrak, B.M.; Kreiger, M.; Pearce, J.M. Mechanical Properties of Components Fabricated with Open-Source 3-D Printers under Realistic Environmental Conditions. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Panes, A.; Claver, J.; Camacho, A.M. The Influence of Manufacturing Parameters on the Mechanical Behaviour of PLA and ABS Pieces Manufactured by FDM: A Comparative Analysis. Materials 2018, 11, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K.; Kaseem, M.; Deri, F. Melt Rheology of Poly (Lactic Acid)/Low Density Polyethylene Polymer Blends. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 1, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzanin, O.; Movrin, D.; Stathopoulos, V.; Pandis, P.; Radusin, T.; Guduric, V. Impact of processing parameters on tensile strength, in-process crystallinity and mesostructure in fdm-fabricated pla specimens. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2019, 25, 1398–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloyaydi, B.A.; Sivasankaran, S.; Ammar, H.R. Influence of infill density on microstructure and flexural behavior of 3D printed pla thermoplastic parts processed by fusion deposition modeling. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2019, 6, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Hao, W. Effect of process parameters on mechanical properties of 3D printed pla lattice structures. Compos. C Open Access 2020, 3, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.H.M.; Coutinho, R.R.T.P.; Drummond, F.R.; Conceição, M.N.; Thiré, R.M.S.M. Evaluation of printing parameters on porosity and mechanical properties of 3D printed pla/pbat blend parts. Macromol. Symp. 2020, 394, 2000157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Windheim, N.; Collinson, D.W.; Lau, T.; Brinson, L.C.; Gall, K. The influence of porosity, crystallinity and interlayer adhesion on the tensile strength of 3D printed polylactic acid (pla). Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 27, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikmat, M.; Rostam, S.; Ahmed, Y.M. Investigation of tensile property-based taguchi method of pla parts fabricated by fdm 3d printing technology. Results Eng. 2021, 11, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, M.S.; Temiz, Ş.; Yaykaşlı, H.; Kaya, A.; Akay, O. Effect of printing speed on fdm 3D-printed pla samples produced using different two printers. Int. J. 3D Print. Technol. Digit. Ind. 2022, 6, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffray, L.; Gouge, P.A.; Hattali, L. Design of experiment analysis on tensile properties of pla samples produced by fused filament fabrication. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 4123–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Farooq, M.U.; Ross, N.S.; Yang, C.H.; Kavimani, V.; Adediran, A.A. Achieving effective interlayer bonding of pla parts during the material extrusion process with enhanced mechanical properties. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.A.; Ahmed, E.S.; Elshaer, A.; Mekhemer, W.; Alsaleem, F.M.; Mohamed, O.A.; Serhatlı, U. Printing parameter optimization of additive manufactured pla using taguchi design of experiment. Polymers 2023, 15, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbart, R.; Papasavvas, A.; Robert, C.; Truong Hoang, T.Q.; Martinez-Hergueta, F. An experimental and numerical study of the mechanical response of 3D printed pla/cb polymers. Compos. Struct. 2023, 319, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M.; Pjević, M.; Milovanović, A.; Mladenović, G.; Milošević, M. Printing parameter optimization of pla material concerning geometrical accuracy and tensile properties relative to fdm process productivity. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Exploring the effects of processing parameters on the flexural performance of polylactic acid fabricated through a customized high extrusion rate fused filament fabrication system. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 14525–14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadete, M.S.; Gomes, T.E.P.; Gonçalves, I.; Neto, V. Influence of 3D-printing deposition parameters on crystallinity and morphing properties of pla-based materials. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajjar, T.; Yang, R.; Ye, L.; Zhang, Y.X. Effects of key process parameters on tensile properties and inter-layer bonding behavior of 3D printed pla using fused filament fabrication. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 1261–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizaan, M.; Baloor, S.S.; Nunna, S.; Mallya, R.; Udupi, S.R.; Kini, C.R.; Kada, S.R.; Creighton, C. A study on the overall variance and void architecture on mex-pla tensile properties through printing parameter optimisation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, B.; Safi Jahanshahi, A. An experimental study on the influence of printing parameters on inter-raster bonding in a single-layer polylactic acid fabricated via fused filament fabrication. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 21270–21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, J.D.; Fountas, N.A.; Papantoniou, I.; Vaxevanidis, N.M. Interlaminar bonding assessment in vertical-oriented filament material extrusion bending specimens. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 4977–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layeb, N.; Barhoumi, N.; Oldal, I.; Keppler, I. Improving the strength properties of pla acetabular liners by optimizing fdm 3D printing: Taguchi approach and finite element analysis validation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 2649–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, K.; Warner, G.; Brown, C.; Ajide, O.; Owolabi, G.; Azimi, A. The effects of build parameters and strain rate on the mechanical properties of fdm 3D-printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene. Open J. Org. Polym. Mater. 2019, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Pridhar, T.; Ramprasath, L.S.; Charan, N.S.; Ruban, W. Prediction of tensile strength in fdm printed abs parts using response surface methodology (rsm). Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, F.; Kurniawan, B.; Yoningtias, M. Optimization of 3D printing process parameters on tensile strength of abs filament material product using taguchi method. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Engineering Science iCAST-ES, Samarinda, Indonesia, 23–24 October 2023; pp. 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaphan, S.; Trutassanawin, W. Effects of process parameters on compressive property of fdm with abs. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 27, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.F.; Mansor, K.K.; Ali, H.B. The effect of fdm process parameters on the compressive property of abs prints. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2022, 49, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Yahya, A. Effects of 3D printing parameters on mechanical properties of abs samples. Designs 2023, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankin, A.; Alipov, Y.; Temirgali, A.; Serik, G.; Danenova, S.; Talamona, D.; Perveen, A. Optimization of printing parameters to enhance tensile properties of abs and nylon produced by fused filament fabrication. Polymers 2023, 15, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, R.T.; Iqbal, A.; Wang, Y.; Rehman, M.; Petra, M.I. Investigation and optimization of effects of 3D printer process parameters on performance parameters. Materials 2023, 16, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaee, A.; Abedini, V.; Kami, A. Effects of fused filament fabrication (fff) process parameters on tensile and flexural properties of abs/pla multi-material. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zou, B.; Wang, P.; Ding, H. Effects of nozzle temperature and building orientation on mechanical properties and microstructure of peek and pei printed by 3d-fdm. Polym. Test. 2019, 78, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Khan, M.S.; Mishra, S.B. Effect of machine parameters on strength and hardness of fdm printed carbon fiber reinforced petg thermoplastics. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hart, C.; Weese, N.A.; Rankin, C.M.; Kuzma, J.; Day, J.B.; Salary, R. Experimental and computational analysis of the mechanical properties of biocompatible bone scaffolds fabricated using fused deposition modeling additive manufacturing process. In Proceedings of the ASME 2020 15th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Virtual, 3 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mao, K.; Leigh, S.; Shah, A.; Chao, Z.; Ma, G. A parametric study of 3D printed polymer gears. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 107, 4481–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, D.; Coppens, M.; Goderis, B.; Zoetelief, W.; Van Puyvelde, P. The extent of interlayer bond strength during fused filament fabrication of nylon copolymers: An interplay between thermal history and crystalline morphology. Polymers 2021, 13, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, M.-H.; Lai, C.-J.; Wang, S.-H.; Zeng, Y.-S.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Pan, C.-Y.; Huang, W.-C. Effect of printing parameters on the thermal and mechanical properties of 3D-printed pla and petg, using fused deposition modeling. Polymers 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamshinath, K.; Kumar, N.N.; Kumar, R.T.; Nagaraju, D.S.; Sateesh, N.; Subbaiah, R. Analysis of the effect of the process parameters on the mechanical strength of 3D printed and adhesively bonded petg single lap joint. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 4509–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, P.; Challa, B.T.; Gummadi, S.K. A comprehensive analysis on the processing-structure-property relationships of fdm-based 3-d printed polyetheretherketone (peek) structures. Materialia 2022, 22, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, C.; Simhambhatla, S.; Bhattacharjee, D. Ensembled surrogate assisted material extrusion based 3D printing process parameter optimization for enhanced mechanical properties of peek. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Wang, X.; Ding, L.; Zeng, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z. Effects of fabrication parameters on the mechanical properties of short basalt-fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites for fused deposition modeling-based 3D printing. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 3341–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortega, A.; Piedra, S.; Mondragón-Rodríguez, G.C.; Camacho, N. Dependence of the mechanical properties of nylon-carbon fiber composite on the fdm printing parameters. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 186, 108419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.B.; Celik, E.; Karkkainen, R.L. Investigation of Interlayer Interface Strength and Print Morphology Effects in FDM 3D-Printed PLA. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 8, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Downey, A.; Yuan, L.; Pratt, A.; Balogun, Y. In situ monitoring for fused filament fabrication process: A review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, V.; Ajinjeru, C.; Nycz, A.; Post, B.; Lindahl, J.; Kunc, V.; Duty, C. Infrared Preheating to Improve Interlayer Strength of Big Area Additive Manufacturing (BAAM) Components. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 14, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.E.N.; Lewis, J.; Moore, A.L. In Situ Infrared Temperature Sensing for Real-Time Defect Detection in Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBean, M.; Yi, N.; Chaplin, A.; Ghita, O. In-Process Thermal Monitoring of the Extrusion Additive Manufacturing Process with High Temperature Polymers. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2555497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqasah, H.; He, F.; Zai, B.A.; Asif, M.; Khan, K.A.; Thakur, V.K.; Khan, M.A. In-situ dynamic response measurement for damage quantification of 3D-printed ABS cantilever beam under thermomechanical load. Polymers 2019, 11, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, M.A.E.; Shaban, I.A.; Mourad, A.-H.; Hegab, H. Advances in Interlayer Bonding in Fused Deposition Modelling: A Review. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2522951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Khan, S.Z.; Sohail, W.; Khan, H.; Sohaib, M.; Nisar, S. Mechanical fatigue in aluminium at elevated temperature and remaining life prediction based on natural frequency evolution. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2015, 38, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğanay Kati, H.; He, F.; Khan, M.; Gökdağ, H.; Alshammari, Y.L.A. Effect of printing parameters on the dynamic characteristics of additively manufactured abs beams: An experimental modal analysis and response surface methodology. Polymers 2025, 17, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ning, H.; Khan, M. Effect of 3D printing process parameters on damping characteristic of cantilever beams fabricated using material extrusion. Polymers 2023, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Khan, M. Effects of printing parameters on the fatigue behaviour of 3D-printed abs under dynamic thermo-mechanical loads. Polymers 2021, 13, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Zheng, B.; Khan, M.; He, F. Influence of sliding direction relative to layer orientation on tribological performance, noise, and stability in 3D-printed abs components. Tribol. Int. 2025, 210, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusabir, A.; Khan, M.A.; Asif, M.; Khan, K.A. Effect of Architected Structural Members on the Viscoelastic Response of 3D Printed Simple Cubic Lattice Structures. Polymers 2022, 14, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; He, F.; Khan, M. Optimization of printing parameters for self-lubricating polymeric materials fabricated via fused deposition modelling. Polymers 2025, 17, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Khan, M.; Aldosari, S. Interdependencies between dynamic response and crack growth in a 3D-printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (abs) cantilever beam under thermo-mechanical loads. Polymers 2022, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Q (kg·m−3) | Cp (J·kg−1·K−1) | k (W·m−1·K−1) | Tg (°C) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 1240 | 1800 | 0.13 | 60 | [58,59] |

| ABS | 1100 | 900 | 0.10 | 105 | [56,60] |

| Material | Ambient (°C) | (s) | Neck Ratio x/a | Healing Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 25 | 18.6 | 0.421 | W = 2.53 × 10−10 |

| PLA | 50 | 30.9 | 0.460 | W = 2.99 × 10−10 (+18%) |

| ABS | 25 | 4.9 | 0.173 | Dh ≈ 0 |

| ABS | 50 | 6.1 | 0.185 | Dh ≈ 0 |

| Author | Parameters Studied | Cooling/Microstructure Effects | Mechanical Outcomes | Optimal Settings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luzanin et al. [62] | Layer thickness, extrusion speed, extrusion temp, bed temp | Thin layers & slow speeds → reduced porosity, stronger bonding | Max tensile strength, crystallinity ≈ 19.6% | 0.2 mm LT, 30 mm/s, 230 °C nozzle, 50 °C bed |

| Aloyaydi et al. [63] | Infill density | Higher infill = lower porosity, shift from brittle to ductile | Optimal flexural strength & toughness at 80% infill | 80% infill |

| Tang et al. [64] | Printing temp, speed, LT, shell thickness | Higher temp → less porosity but brittle fracture; slower speeds improved fusion | Tensile ≈ 51.5 MPa; Elastic modulus ≈ 5102 MPa | 230 °C, 60 mm/min |

| Cardoso et al. [65] | LT, deposition speed, build direction | Thin layers + low speed → denser parts, better bonding | Flexural ≈ 52.5 MPa vs. ≈23.2 MPa at worst settings | 0.10 mm LT, 40 mm/s, 0° build |

| Von Windheim et al. [66] | LT, speed, orientation, annealing | Sub-Tcc anneal healed welds; crystallinity increase alone ineffective | UTS: 64 MPa (XY), 37 MPa (YZ) | 0.1 mm LT, 20 mm/s, 65 °C anneal |

| Hikmat et al. [67] | Orientation, raster, nozzle dia., temp, infill, shells, speed | Build orientation largest effect on cooling paths and bonding | Build orientation: 44.7% influence; nozzle dia. 0.5 mm & 100% infill optimal | On-edge orientation, 0.5 mm nozzle, 100% infill |

| Kamer et al. [68] | Print speed | High speeds ↑ porosity, ↓ strength; slower speeds ↓ voids | Tensile strength decreased sharply at >80 mm/s | ≤30 mm/s |

| Auffray et al. [69] | Infill pattern, LT, infill density, speed, raster, overlap, temp | Dense infill retained heat, reduced porosity | Infill density & pattern most significant | 100% infill, optimized pattern |

| Kumar et al. [70] | LT, speed, nozzle temp | Thin layers & moderate speeds improved crack resistance | Tensile ≈ 45.5 MPa; Flexural ≈ 78.5 MPa | 0.10 mm LT, 60 mm/s, 200 °C |

| Ahmed et al. [71] | Infill density, pattern, LT, nozzle temp, annealing | Annealing at 90 °C improved bonding diffusion | UTS ≈ 37.2 MPa | 90 °C annealing, gyroid infill |

| Delbart et al. [72] | Nozzle dia., raster angle, LT | High crystallinity improved ductility > porosity effects | Strong crystallinity–toughness link | Larger nozzle, 45° raster |

| Popović et al. [73] | Nozzle temp, speed | Moderate heat + low speed optimised accuracy & bonding | Max tensile & lowest roughness at 190 °C, 40 mm/min | 190 °C, 40 mm/min |

| Wang et al. [74] | Nozzle dia., bead width, infill orientation | Bead width dominated void geometry → flexural strength | Flexural strength ↑ 15% by bead width control | Wider beads at optimal width |

| Cadete et al. [75] | Speed, bed temp, nozzle temp, fan speed, flow | Slow speed + high bed temp promoted crystallinity | Crystallinity ≈ 71% (max) | 10 mm/s, 80 °C bed |

| Gajjar et al. [76] | LT, raster angle, feed, nozzle temp | Thin layers + high temp ↓ voids, ↑ fusion | Strength ↑ 40% with raster optimisation | 0.2 mm LT, 0° raster, 220 °C |

| Faizaan et al. [77] | Nozzle dia., LT | Large nozzle + fine layers ↓ porosity → strong bonding | CV ≈ 5.5% for tensile reproducibility | 0.8 mm nozzle, 0.1 mm LT |

| Akhoundi & Jahanshahi [78] | Nozzle temp, extrusion width, LT, speed, infill | Zigzag infill + high temp improved inter-raster bonding | UTS ≈ 72 MPa | 210 °C, 0.8 mm width, 0.3 mm LT, 80 mm/s |

| Kechagias et al. [79] | Flow rate, nozzle temp, speed | Heat input (flow, temp) governed fusion quality | Flexural ≈ 67 MPa; Surface Ra ≈ 13 µm | 100% flow, 227 °C |

| Layeb et al. [80] | Nozzle temp, speed, LT, raster | Thin layers + 0° raster yielded strong bonding | UTS ≈ 51 MPa, E ≈ 3.4 GPa | 210 °C, 30 mm/s, 0.1 mm LT, 0° raster |

| Author | Parameters Studied | Cooling/Microstructure Effects | Mechanical Outcomes | Optimal Settings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hibbert et al. [81] | Raster angle, layer thickness, fill style | Thicker layers altered cooling, residual stress, bonding | Modulus of toughness ↑; UTS ≈ 27.4 MPa | 0.254 mm LT, [0°/90°] raster, solid fill |

| Srinivasan et al. [82] | Infill pattern, infill density, LT | Dense infill slowed cooling, reduced air gaps | Max tensile strength with triangular infill | Triangular infill, high density, thin LT |

| Rachman et al. [83] | LT, infill pattern, nozzle temp | Thinner layers improved heat distribution & bonding | Highest tensile strength at 0.2 mm LT | 0.2 mm LT, line infill, 230 °C nozzle |

| Nathaphan & Trutassanawin [84] | Nozzle temp, bed temp, shells, LT, speed, orientation | Elevated bed temp slowed cooling, enhanced bonding | Max compressive stress at low LT, low speed | 0.20 mm LT, 41–50 mm/s, 109–120 °C bed |

| Abbas et al. [85] | Shell width, infill density, pattern, LT | Dense infill & thin layers moderated cooling, reduced voids | Compressive strength ↑ at 60% infill | 0.8 mm shell, 60% infill, 0.2 mm LT |

| Ahmad & Yahya [86] | Infill pattern, raster orientation, LT, speed | Orientation controlled cooling paths, reducing voids | 45° raster & 0.3 mm LT gave highest UTS | 45° raster, 0.3 mm LT, normal speed |

| Yankin et al. [87] | Infill pattern, density, speed | Dense triangular infill retained heat, ↓ porosity | Max tensile at 100% density, tri-hex infill | 100% infill, tri-hex pattern, 65 mm/s |

| Mushtaq et al. [88] | LT, infill density, speed | High infill slowed cooling, reduced porosity | Optimal multi-objective performance at high density | 0.27 mm LT, 84% infill, 51 mm/s |

| Khodaee et al. [89] | Infill density, raster angle, speed | Dense infill & 0° raster promoted uniform cooling & bonding | Max tensile & flexural strength | 100% infill, 0° raster, 26 mm/s |

| Author | Material | Parameters Studied | Cooling/Microstructure Effects | Mechanical Outcomes | Optimal Settings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding et al. [90] | PEEK, PEI | Nozzle temp, orientation | High temp slowed cooling, ↓ porosity, ↑ bonding | PEEK: Flexural ≈ 135 MPa; Density ≈ 92.8% | 390–400 °C nozzle, horizontal |

| Ajay Kumar et al. [91] | PETG-CF | Speed, infill density, LT | Dense infill slowed cooling, improved fibre bonding | Tensile, flexural, hardness improved | 60 mm/s, 80% infill, 0.2 mm LT |

| Zhao et al. [92] | PAPC-II | Flow, LT, infill, shell, speed, raster | High flow & density slowed cooling, reduced voids | Tensile ≈ 140 MPa; Yield stress ≈ 115 MPa | 125% flow, 0.25 mm LT, 90% infill |

| Zhang et al. [93] | Nylon 618 | Temp, speed, bed temp, infill | Crystallinity ↑ → wear resistance; but ↓ bond strength | Fatigue life up to ≈52 h | 250 °C, 70 mm/s, 80% infill |

| Vaes et al. [94] | Nylon copolymers | Liquefier temp, bed temp, speed | High crystallinity restricted diffusion, ↓ bond strength | Tear energy ↑ at 260 °C but weld weak | 260 °C nozzle, 110 °C bed |

| Hsueh et al. [95] | PLA, PETG | Temp, speed | High temp ↑ fusion, ↓ porosity | PLA > PETG in strength; PETG > PLA in thermal resistance | High temp + high speed (PLA) |

| Vamshinath et al. [96] | PETG joints | Raster angle, raster width, LT, adhesive thickness | Raster alignment & thin LT improved adhesion | Tensile ≈ 61 MPa, high stiffness | 0° raster, 1 mm width, 0.2 mm LT |

| Sikder et al. [97] | PEEK | Nozzle, bed, chamber temp, LT, speed | High nozzle & chamber temps ↑ crystallinity, ↓ voids | Tensile, flexural, compressive improved | 410 °C nozzle, 90 °C chamber |

| Padhy et al. [98] | PEEK | LT, speed, orientation, nozzle temp | Orientation & temp controlled cooling, crystallinity | UTS up to ≈97.8 MPa; Elongation up to ≈121% | 0.1 mm LT, 16 mm/s, 401 °C nozzle |

| Hua et al. [99] | BF–Polyamide | Temp, speed, LT | High temp & fine layers ↓ voids, ↑ fibre adhesion | Tensile ≈ 36.7 MPa; Compression ≈ 30.6 MPa | 215 °C, 35 mm/s, 0.2 mm LT |

| Gómez-Ortega et al. [100] | PA-CF | Wall thickness, infill %, nozzle temp | High infill ↑ bonding but risked voids | Tensile ≈ 52.8 MPa; Modulus ≈ 1366 MPa | 99% infill, 1.2 mm wall, 230 °C nozzle |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alzahrani, A.S.; Khan, M.; He, F. Fundamentals of Cooling Rate and Its Thermodynamic Interactions in Material Extrusion. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120412

Alzahrani AS, Khan M, He F. Fundamentals of Cooling Rate and Its Thermodynamic Interactions in Material Extrusion. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120412

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlzahrani, Ahmad Saeed, Muhammad Khan, and Feiyang He. 2025. "Fundamentals of Cooling Rate and Its Thermodynamic Interactions in Material Extrusion" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120412

APA StyleAlzahrani, A. S., Khan, M., & He, F. (2025). Fundamentals of Cooling Rate and Its Thermodynamic Interactions in Material Extrusion. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120412