Enhancing Geometric Deviation Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Varied Process Parameters Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

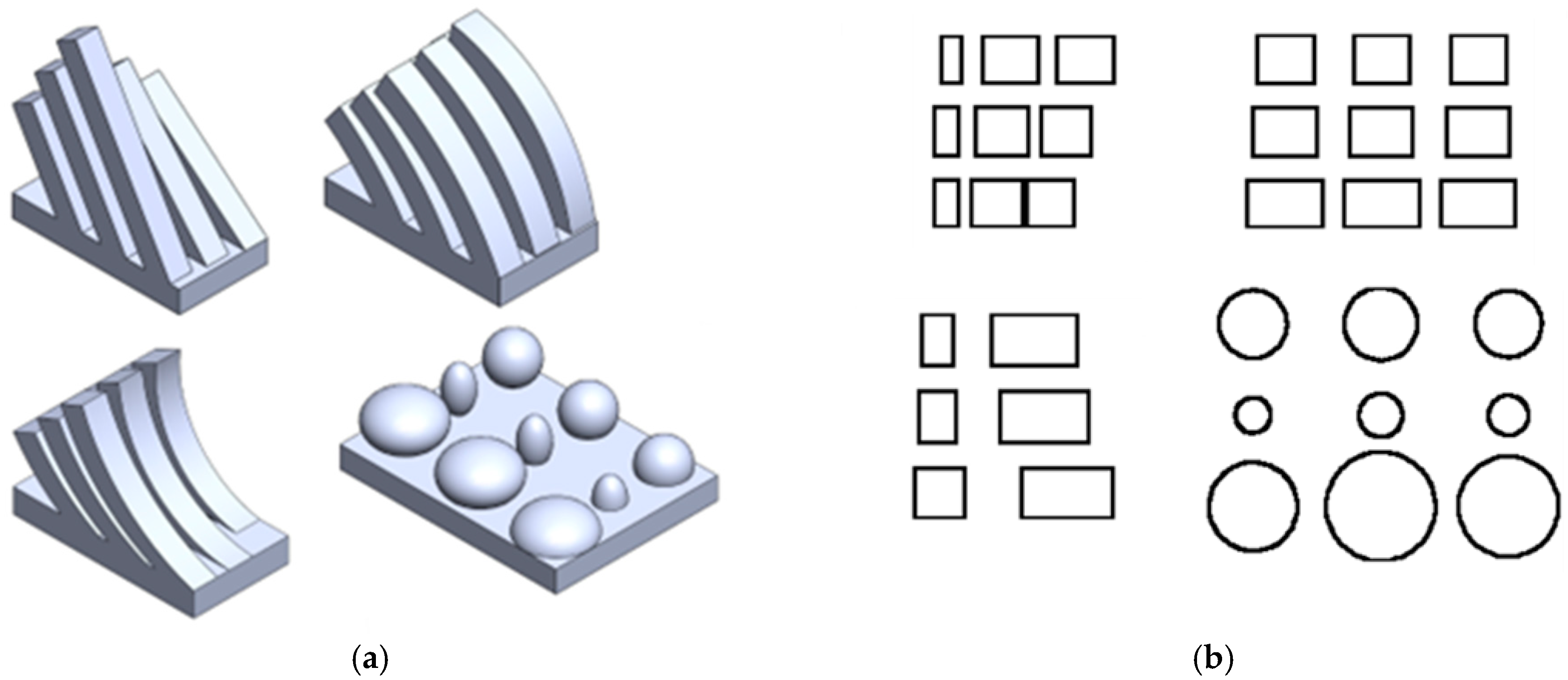

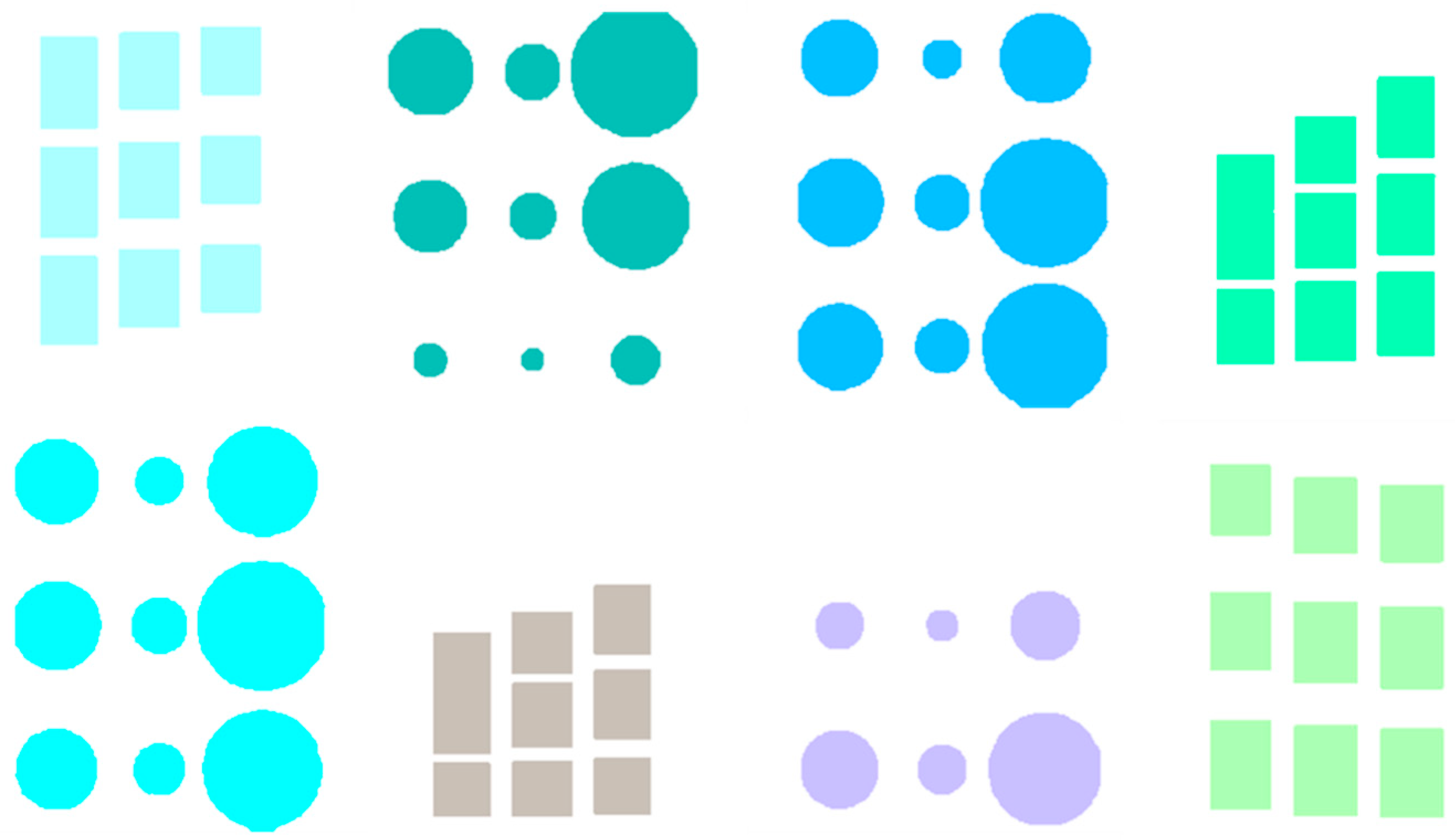

3.1. Test Artifact Design and Experimental Setup

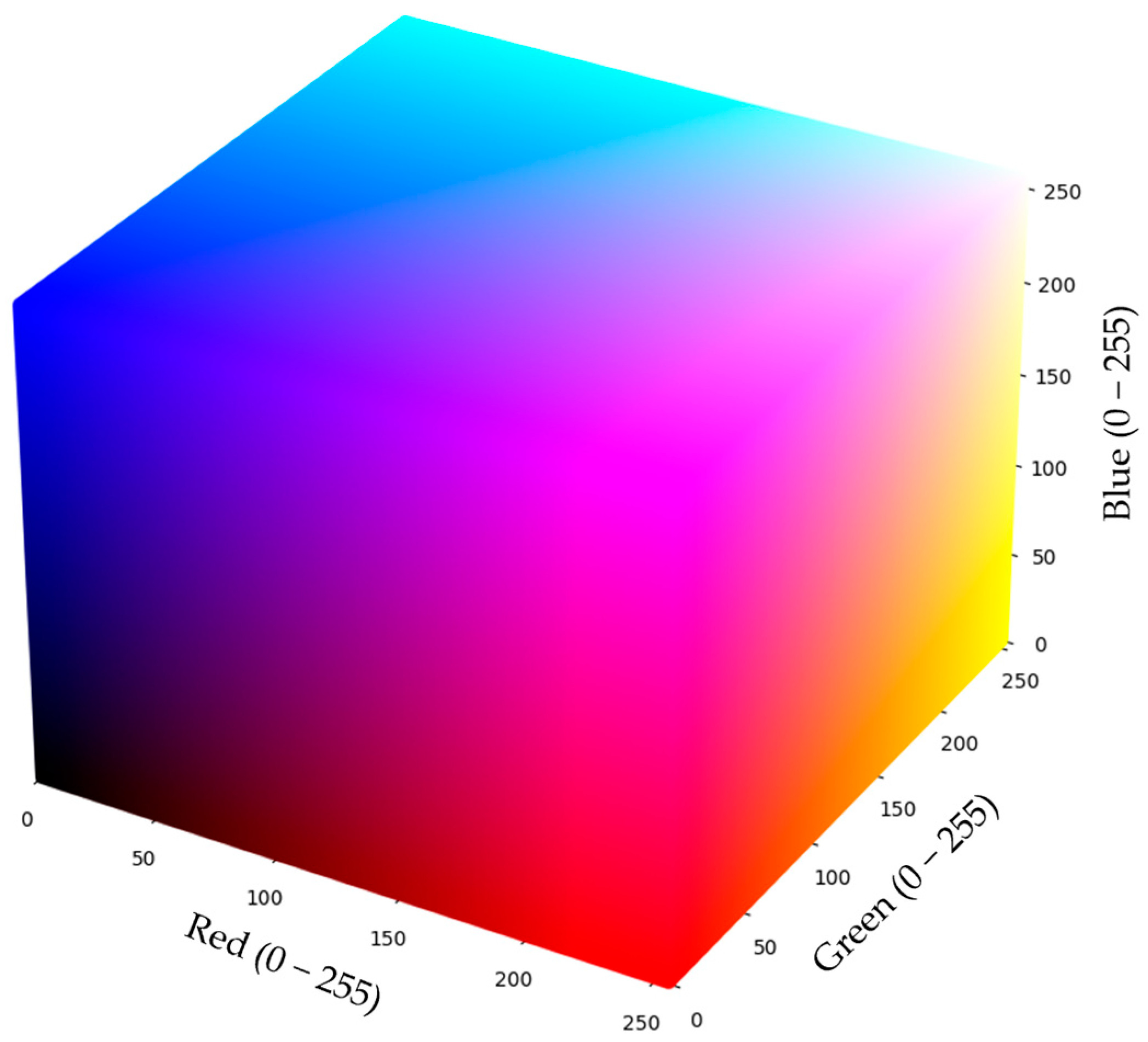

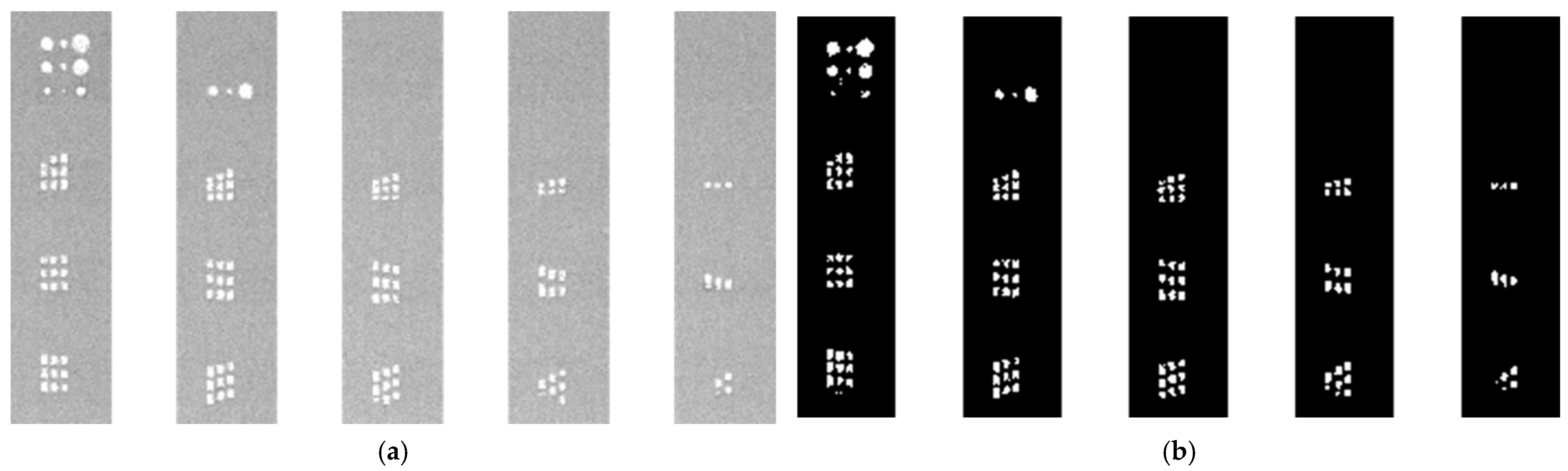

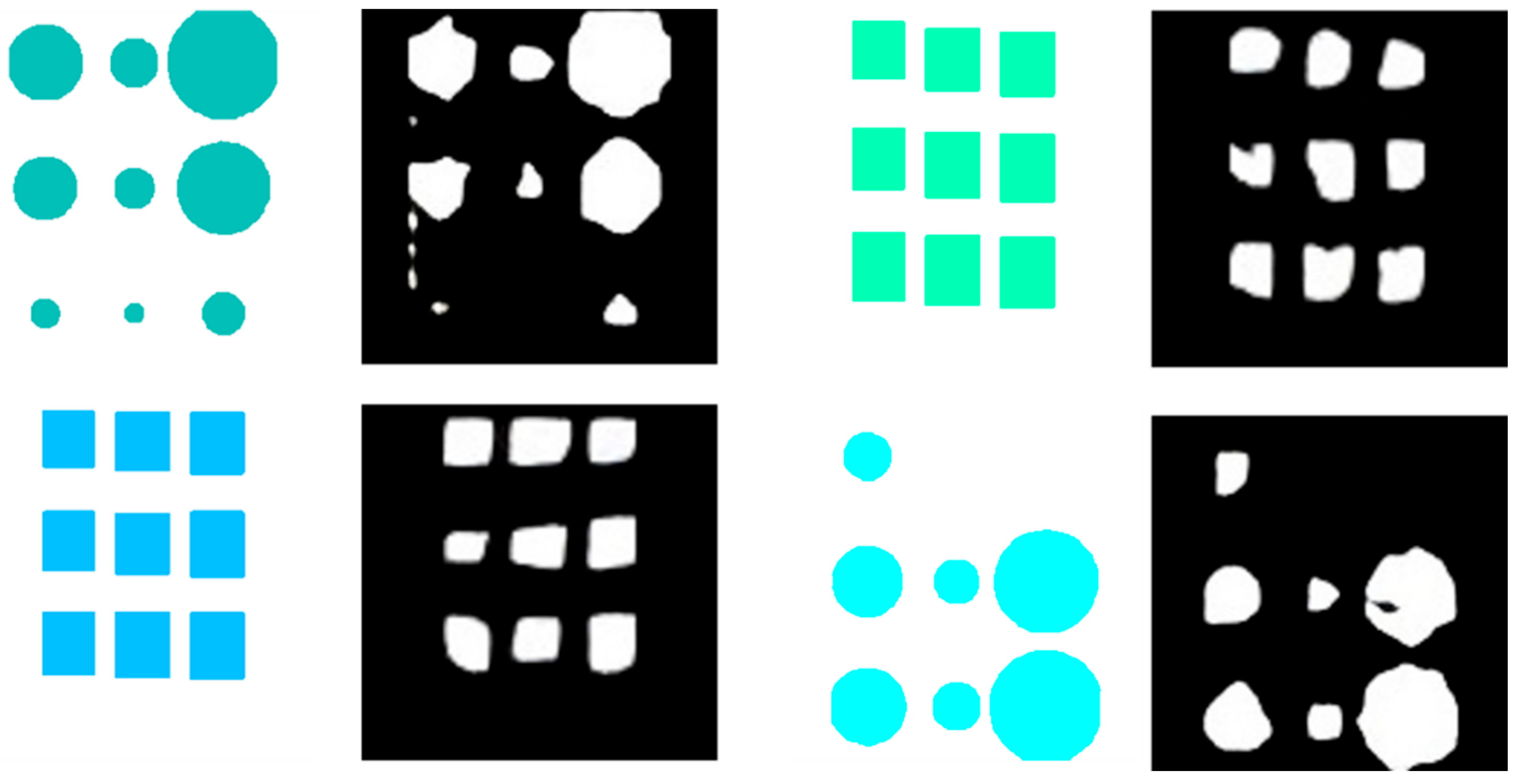

3.2. Data Set Preparation

3.3. Pix2Pix Model Architecture and Training

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results

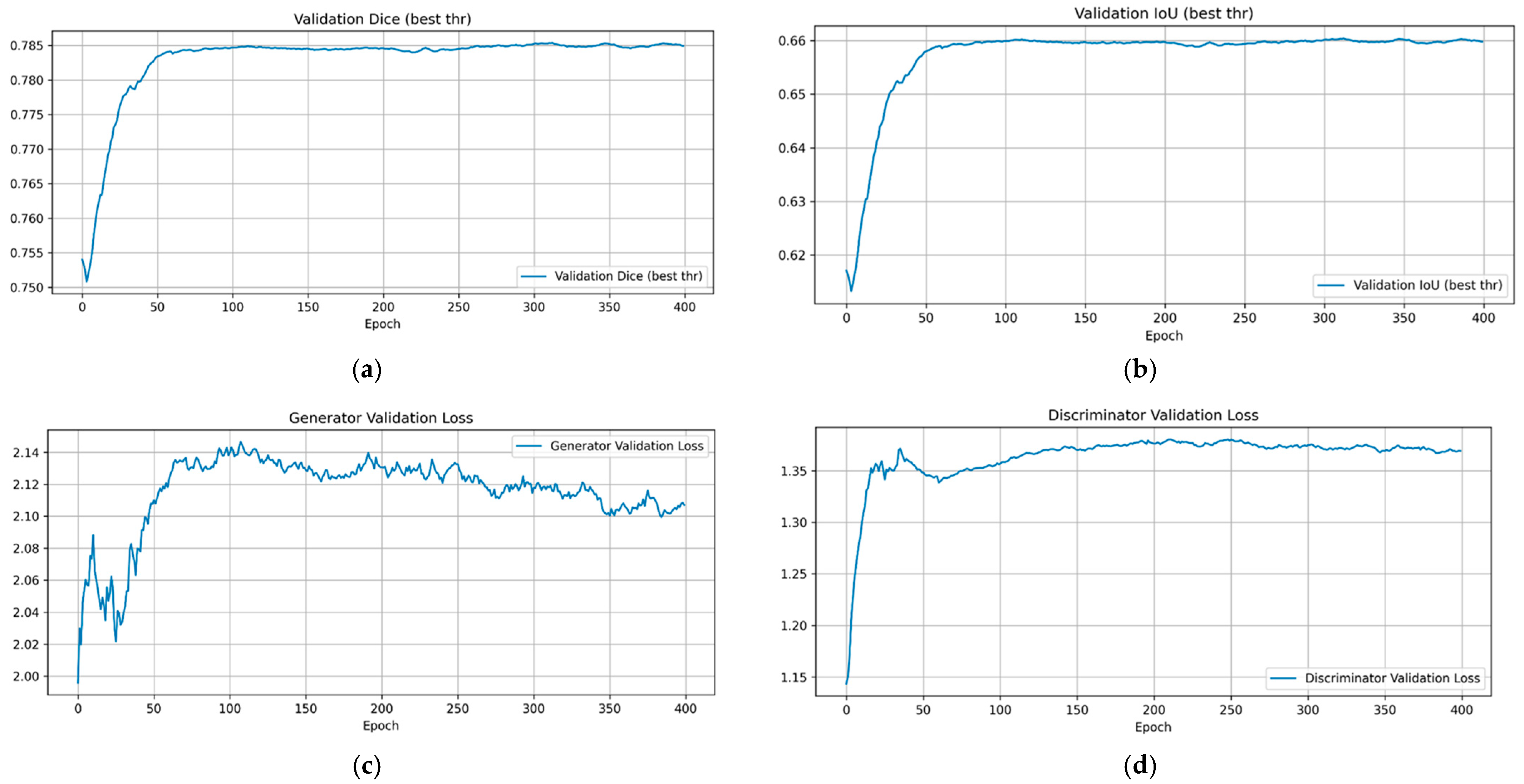

4.1. Model Training and Validation Performance

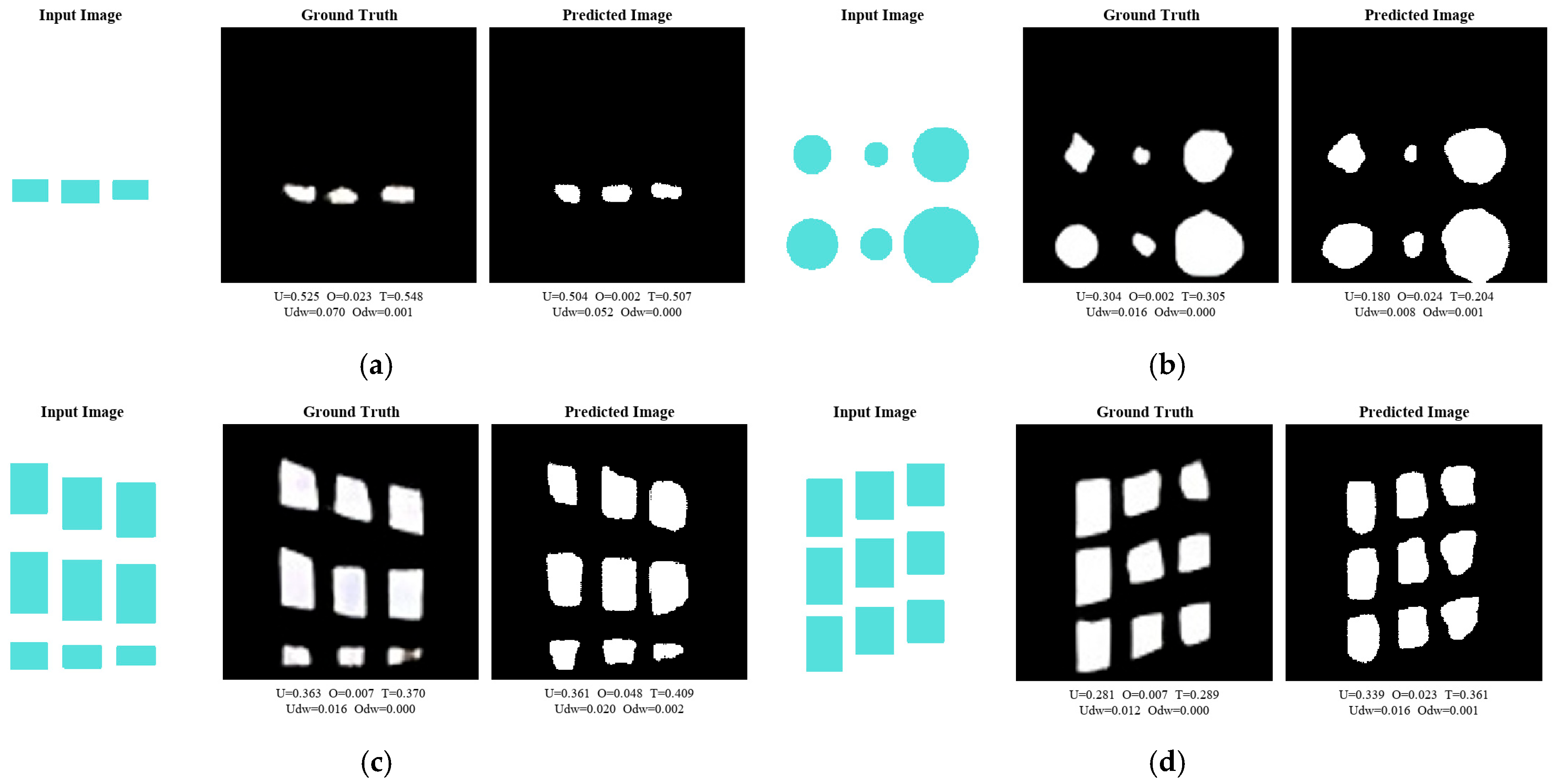

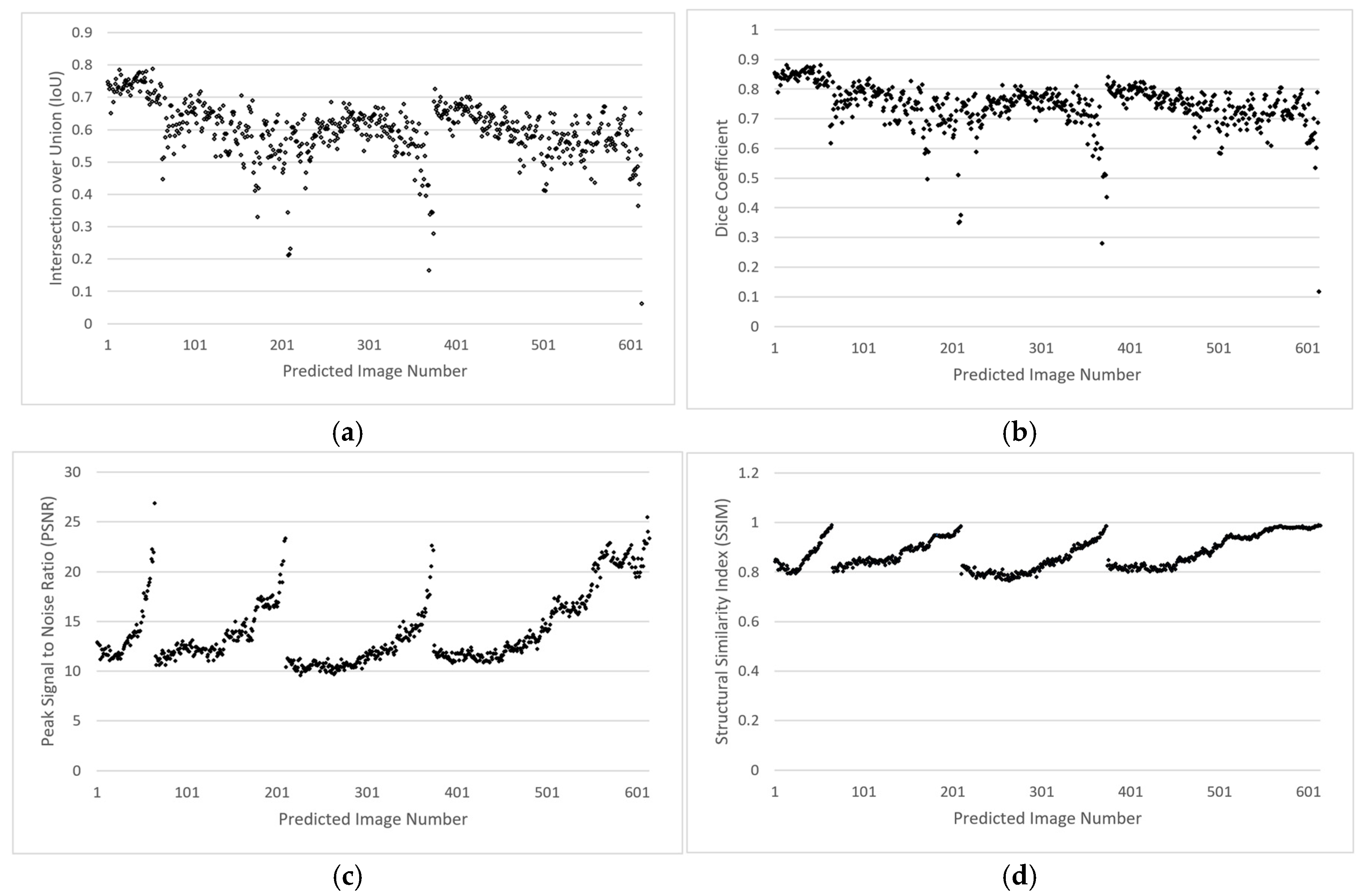

4.2. Visual and Quantitative Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ASTM International. Standard Terminology for Additive Manufacturing Technologies; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, M.; Lyons, K.W.; Gupta, S.K. Sustainability Characterization for Additive Manufacturing. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2014, 119, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.M.; Bian, L.; Shamsaei, N.; Yadollahi, A. An Overview of Direct Laser Deposition for Additive Manufacturing: Part I—Transport Phenomena, Modeling and Diagnostics. Addit. Manuf. 2015, 8, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzon, C. The Process Atmosphere as a Parameter in the Laser-Powder Bed Fusion Process; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.U.; Jacob, G.; Possolo, A.; Beauchamp, C.; Peltz, M.; Stoudt, M.; Donmez, A. The Effects of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Parameters on Material Hardness and Density for Nickel Alloy 625; NIST Advanced Manufacturing Series 100-19; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fotovvati, B.; Balasubramanian, M.; Asadi, E. Modeling and Optimization Approaches of Laser-Based Powder-Bed Fusion Process for Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Coatings 2020, 10, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, D.; Wahlquist, S.; Ali, A. Critical Review of LPBF Metal Print Defects Detection: Roles of Selective Sensing Technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malý, M.; Nopová, K.; Klakurková, L.; Adam, O.; Pantělejev, L.; Koutný, D. Effect of Preheating on the Residual Stress and Material Properties of Inconel 939 Processed by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2022, 15, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.; Yasin, M.S.; Ye, J.; Liu, J.; Vinel, A.; Shao, S.; Shamsaei, N. Feature-Based Volumetric Defect Classification in Metal Additive Manufacturing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, J.; Ponsot, A.G.; Jolma, C.J.; Lin, D. A Review on Scan Strategies in Laser-Based Metal Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 5425–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğu, M.N.; Ozer, S.; Yalçın, M.A.; Davut, K.; Obeidi, M.A.; Simsir, C.; Gu, H.; Teng, C.; Brabazon, D. A Comprehensive Study of the Effect of Scanning Strategy on IN939 Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion-Laser Beam. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 5457–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monu, M.C.C.; Afkham, Y.; Chekotu, J.C.; Ekoi, E.J.; Gu, H.; Teng, C.; Ginn, J.; Gaughran, J.; Brabazon, D. Bi-Directional Scan Pattern Effects on Residual Stresses and Distortion in As-Built Nitinol Parts: A Trend Analysis Simulation Study. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2023, 12, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, T.; Zou, Z.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liao, W. Monitoring of Warping Deformation of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Formed Parts. Chin. J. Lasers 2024, 51, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Wang, M.; Trofimov, V.; Yang, Y.; Song, C. Research on the Warping and Dross Formation of an Overhang Structure Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liang, A.; Bellin, M.; Bressloff, N.W. Effects of Process Parameters and Geometry on Dimensional Accuracy and Surface Quality of Thin Strut Heart Valve Frames Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Yin, J.; Li, Y.; Nie, Z.; Li, X.; You, D.; Guan, K.; Duan, W.; Cao, L.; et al. A Review of Spatter in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: In Situ Detection, Generation, Effects, and Countermeasures. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, D.; Elwany, A.; Du, Y. Deep Learning to Analyze Spatter and Melt Pool Behavior During Additive Manufacturing. Metals 2025, 15, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, N.D.; Tucho, W.M.; Lemu, H.G. Effects of Scanning Strategies, Part Orientation, and Hatching Distance on the Porosity and Hardness of AlSi10Mg Parts Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, D.; Meiners, W.; Pirch, N.; Wissenbach, K.; Schrage, J. Investigation on Reducing Distortion by Preheating During Manufacture of Aluminum Components Using Selective Laser Melting. J. Laser Appl. 2013, 26, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamert, V. Machine Learning Approaches for Process Monitoring in Powder Bed Fusion of Polymers; Technische Universität Wien: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Tang, D.; Yang, L.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, J.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y. Multi-Physics Modeling for Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 954, 170207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afazov, S.; Rahman, H.; Serjouei, A. Investigation of the Right First-Time Distortion Compensation Approach in Laser Powder Bed Fusion of a Thin Manifold Structure Made of Inconel 718. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 69, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S.; Nedeljkovic-Groha, V. Distortion Compensation of Thin-Walled Parts by Pre-Deformation in Powder Bed Fusion with Laser Beam. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 75, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Lan, B.; Jiang, C.; Terzi, S.; Zheng, C.; Eynard, B.; Anwer, N.; Huang, H. Graph Attention-Based Knowledge Reasoning for Mechanical Performance Prediction of L-PBF Printing Parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 4175–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xiao, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, G.; Xiao, W. Knowledge Graph Network-Driven Process Reasoning for Laser Metal Additive Manufacturing Based on Relation Mining. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 11472–11483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Eynard, B.; Anwer, N.; Durupt, A.; Le Duigou, J.; Danjou, C. STEP/STEP-NC-Compliant Manufacturing Information of 3D Printing for FDM Technology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 1713–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, P.; Sapkota, H.; Jung, S. In-Situ Monitoring and Prediction of Geometric Deviation in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASNT Rearch Symposiu, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Fardo, F.; Conforto, V.; Oliveira, F.; Rodrigues, P. A Formal Evaluation of PSNR as Quality Measurement Parameter for Image Segmentation Algorithms. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.07116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment: From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Lin, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, W.; Hu, K.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, Z. Optimization-Based Non-Equidistant Toolpath Planning for Robotic Additive Manufacturing with Non-Underfill Orientation. Robot Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 84, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, T.; Doubrovski, E.L.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.C. A Framework for Adaptive Width Control of Dense Contour-Parallel Toolpaths in Fused Deposition Modeling. Comput.-Aided Des. 2020, 128, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, V.; Weltsch, Z. Full-Surface Geometric Analysis of DMLS-Manufactured Stainless Steel Parts after Post-Processing Treatments. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Breuning, C.; Körner, C. Electron-Optical In Situ Imaging for the Assessment of Accuracy in Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2021, 14, 7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) Workshops 2021, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

| RGB Values | Process Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Red | 0 | Laser Speed | 100 mm/s |

| 255 | 1000 mm/s | ||

| Green | 0 | Laser Power | 20 W |

| 255 | 100 W | ||

| Blue | 0 | Hatch Spacing | 30 µm |

| 255 | 100 µm | ||

| S.N. | Laser Speed (mm/s) | Laser Power (W) | Hatch Spacing (µm) | Layer Thickness (µm) | Energy Density (J/mm3) | Red | Green | Blue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 400 | 80 | 80 | 30 | 83.3 | 85 | 191.25 | 182.14 |

| 2 | 400 | 80 | 100 | 30 | 66.7 | 85 | 191.25 | 255 |

| 3 | 400 | 100 | 80 | 30 | 104 | 85 | 255 | 182.14 |

| 4 | 400 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 83.3 | 85 | 255 | 255 |

| 5 | 800 | 80 | 80 | 30 | 41.7 | 198 | 191.25 | 182.14 |

| 6 | 800 | 80 | 100 | 30 | 33.3 | 198 | 191.25 | 255 |

| 7 | 800 | 100 | 80 | 30 | 52.1 | 198 | 255 | 182.14 |

| 8 | 800 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 41.7 | 198 | 255 | 255 |

| 9 | 600 | 90 | 90 | 30 | 55.6 | 142 | 223.125 | 218.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhandari, S.; Sapkota, H.; Jung, S. Enhancing Geometric Deviation Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Varied Process Parameters Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120411

Bhandari S, Sapkota H, Jung S. Enhancing Geometric Deviation Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Varied Process Parameters Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(12):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120411

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhandari, Subigyamani, Himal Sapkota, and Sangjin Jung. 2025. "Enhancing Geometric Deviation Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Varied Process Parameters Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 12: 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120411

APA StyleBhandari, S., Sapkota, H., & Jung, S. (2025). Enhancing Geometric Deviation Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion with Varied Process Parameters Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(12), 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9120411