A Tiered Occupational Risk Assessment for Ceramic LDM: On-Site Exposure, Particle Morphology and Toxicity of Kaolin and Zeolite Feedstocks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Printer, Material Mixture

2.2. Risk Assessment Methodology

2.2.1. Tier 1—Information Gathering

2.2.2. Tier 2—On-Site Exposure Measurements

2.2.3. Tier 3—Toxicological, Morphological, and Elemental Assessment

Cell Lines and Cell Cultures

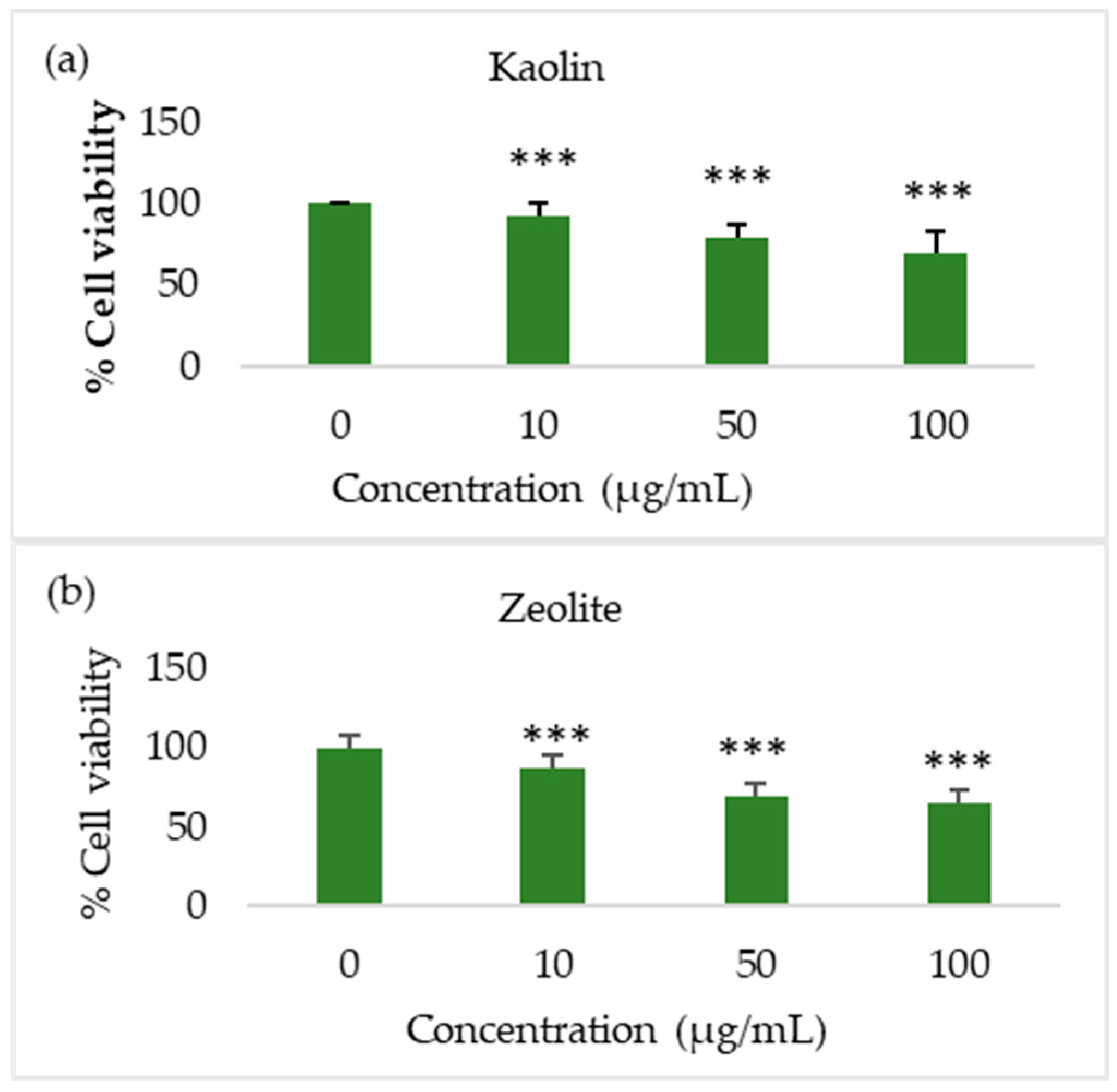

Cell Viability—MTT

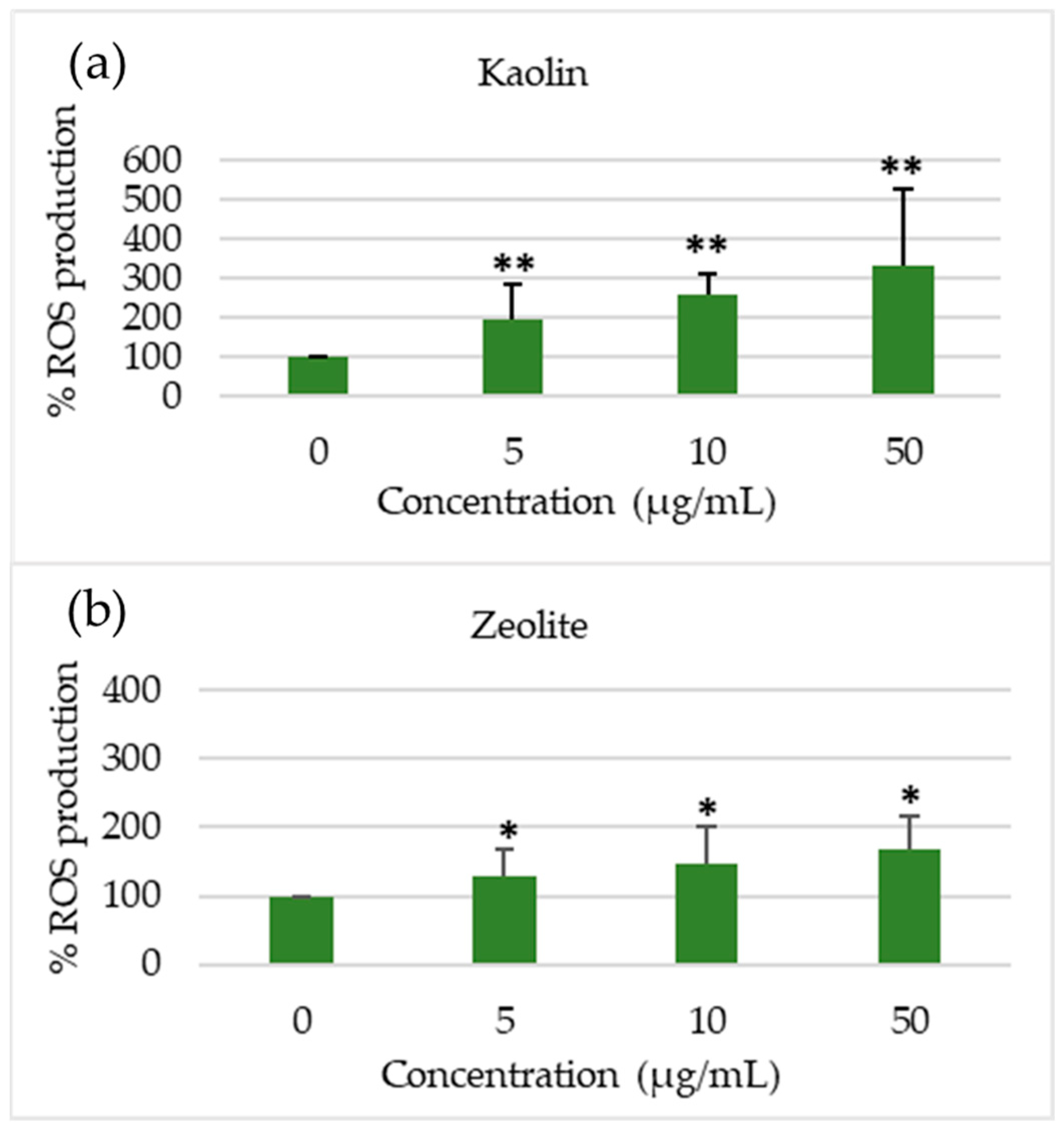

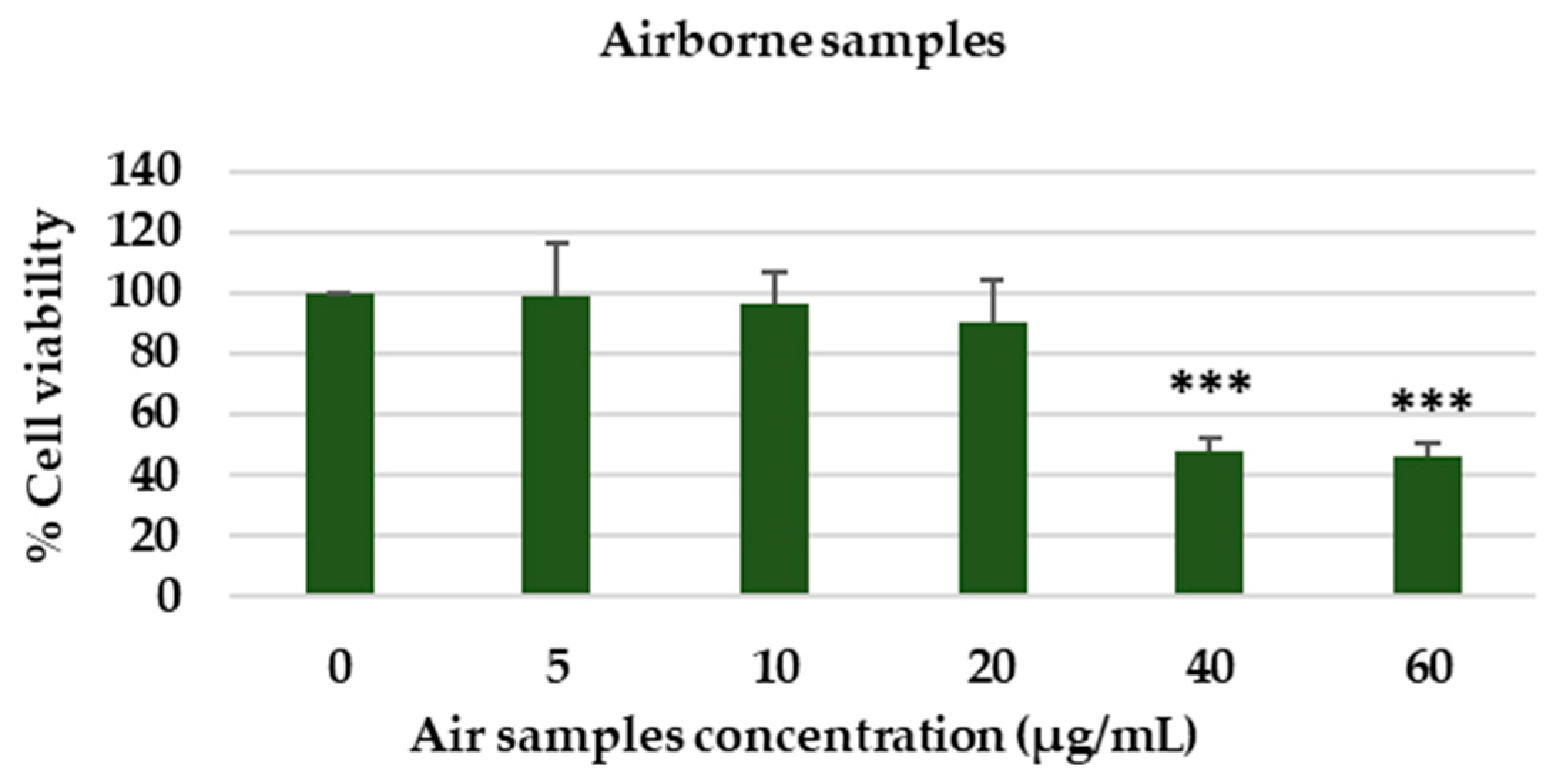

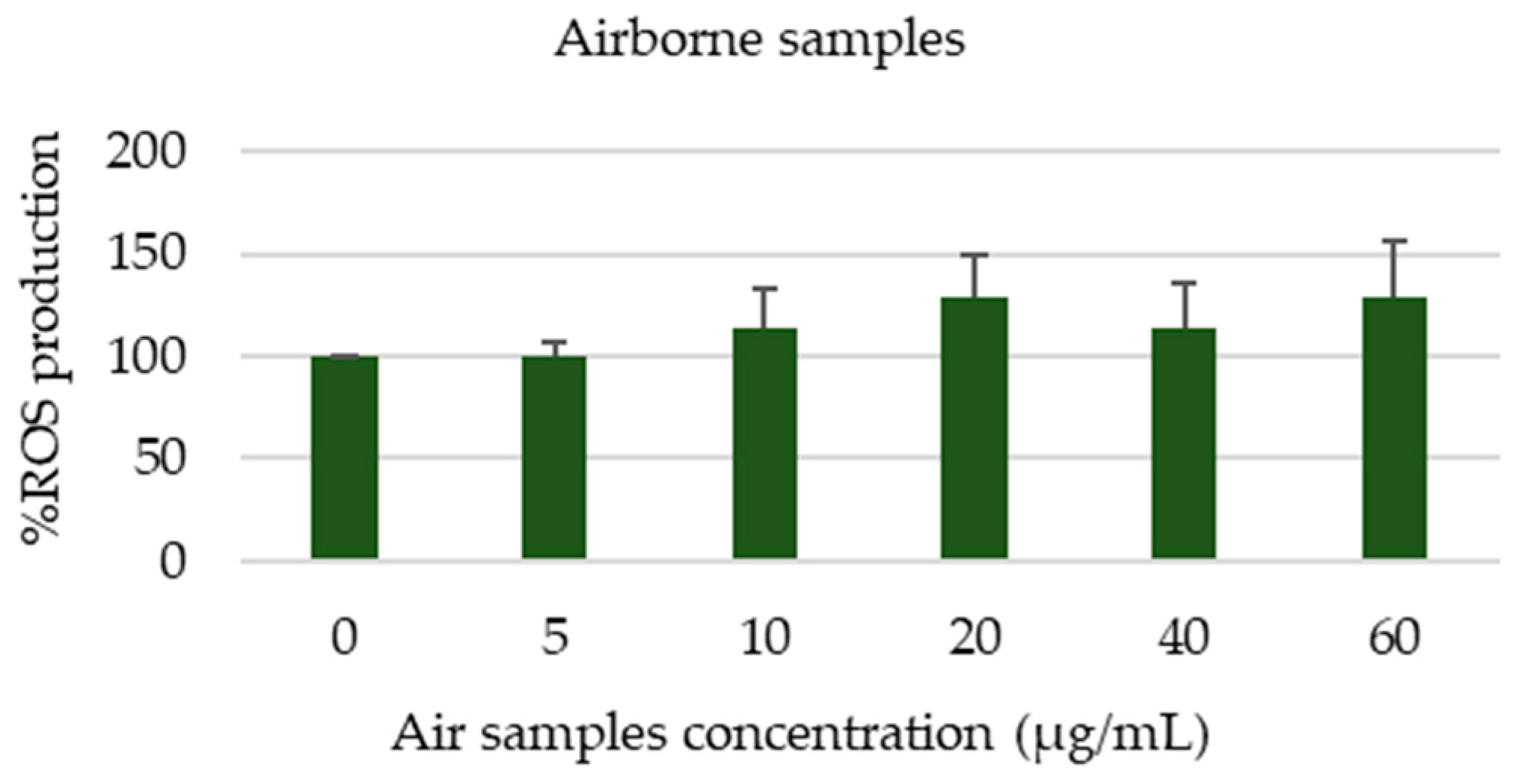

Reactive Oxygen Species Production

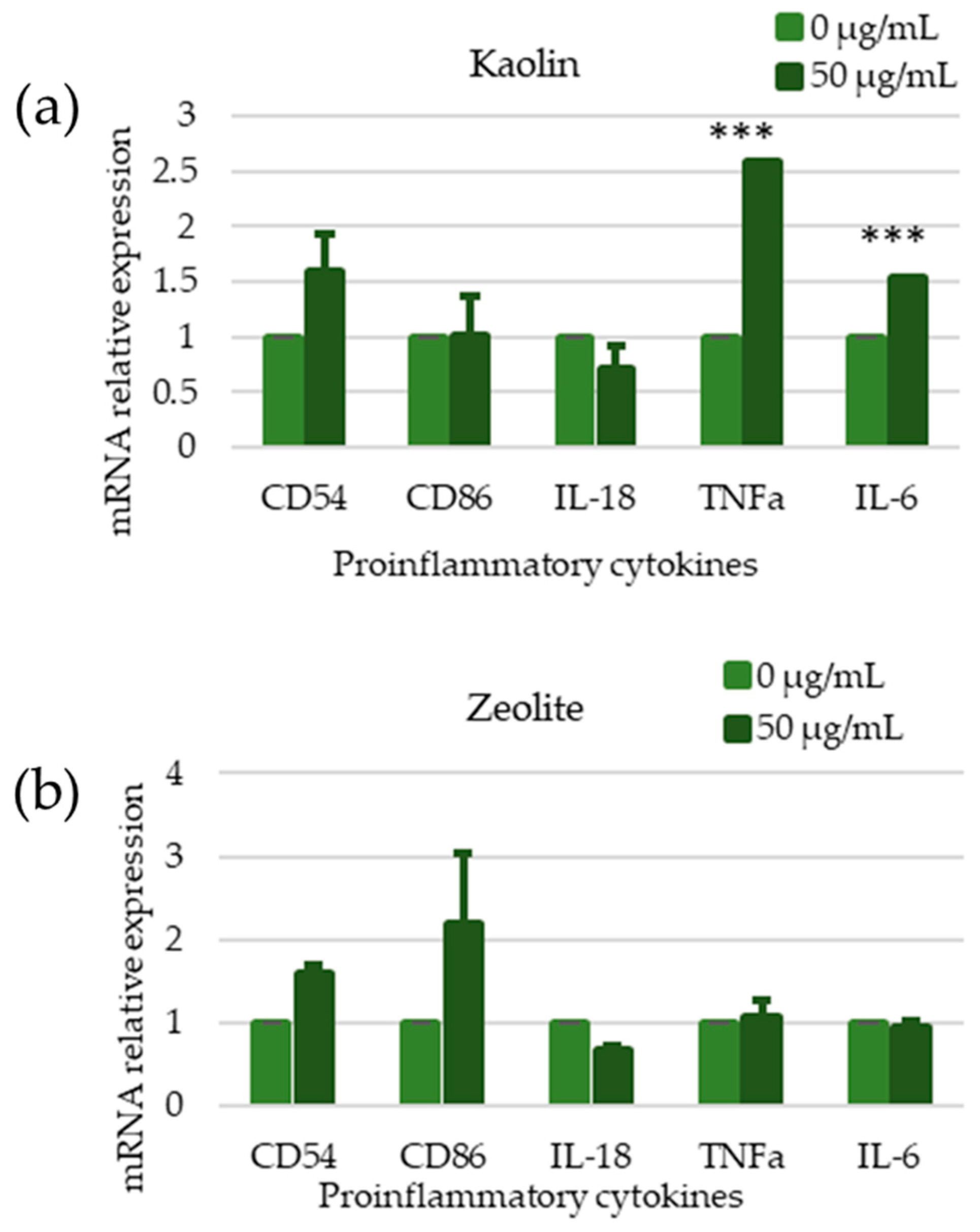

Inflammatory Gene Expression Levels—RT-PCR

Test Materials and Preparation for In Vitro Toxicological Assessments

Statistical Analyses

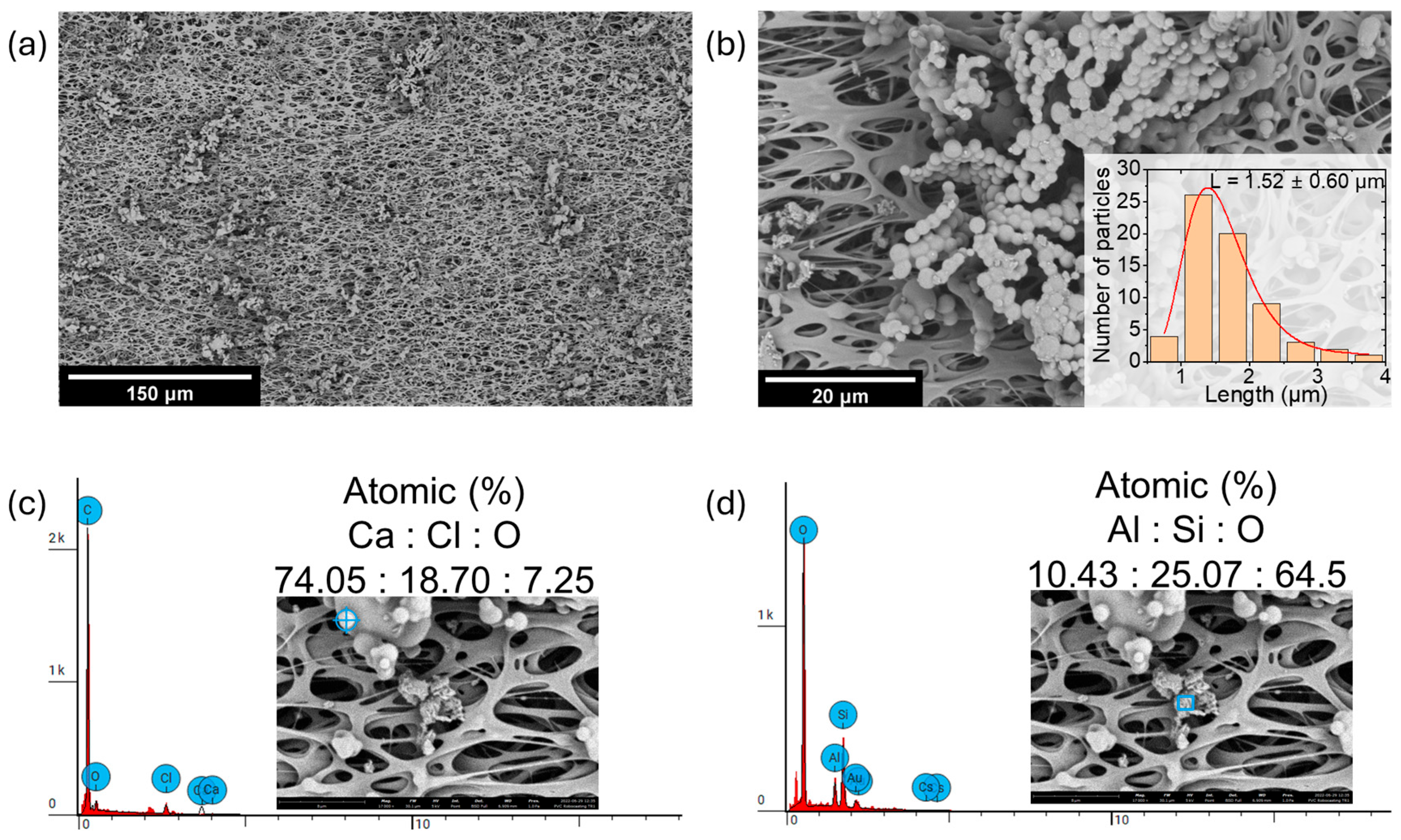

Morphological and Elemental Characterisation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Assessment

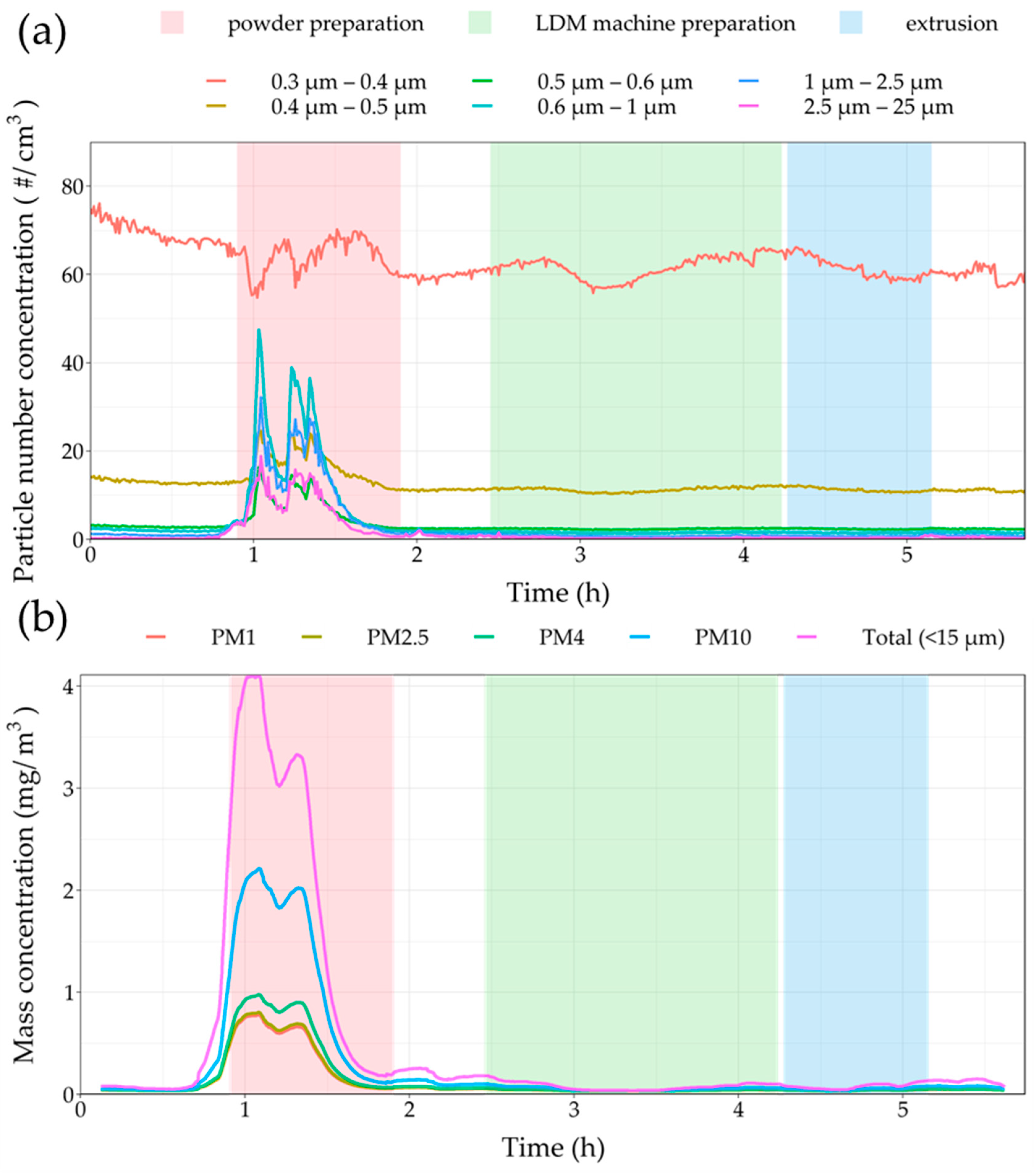

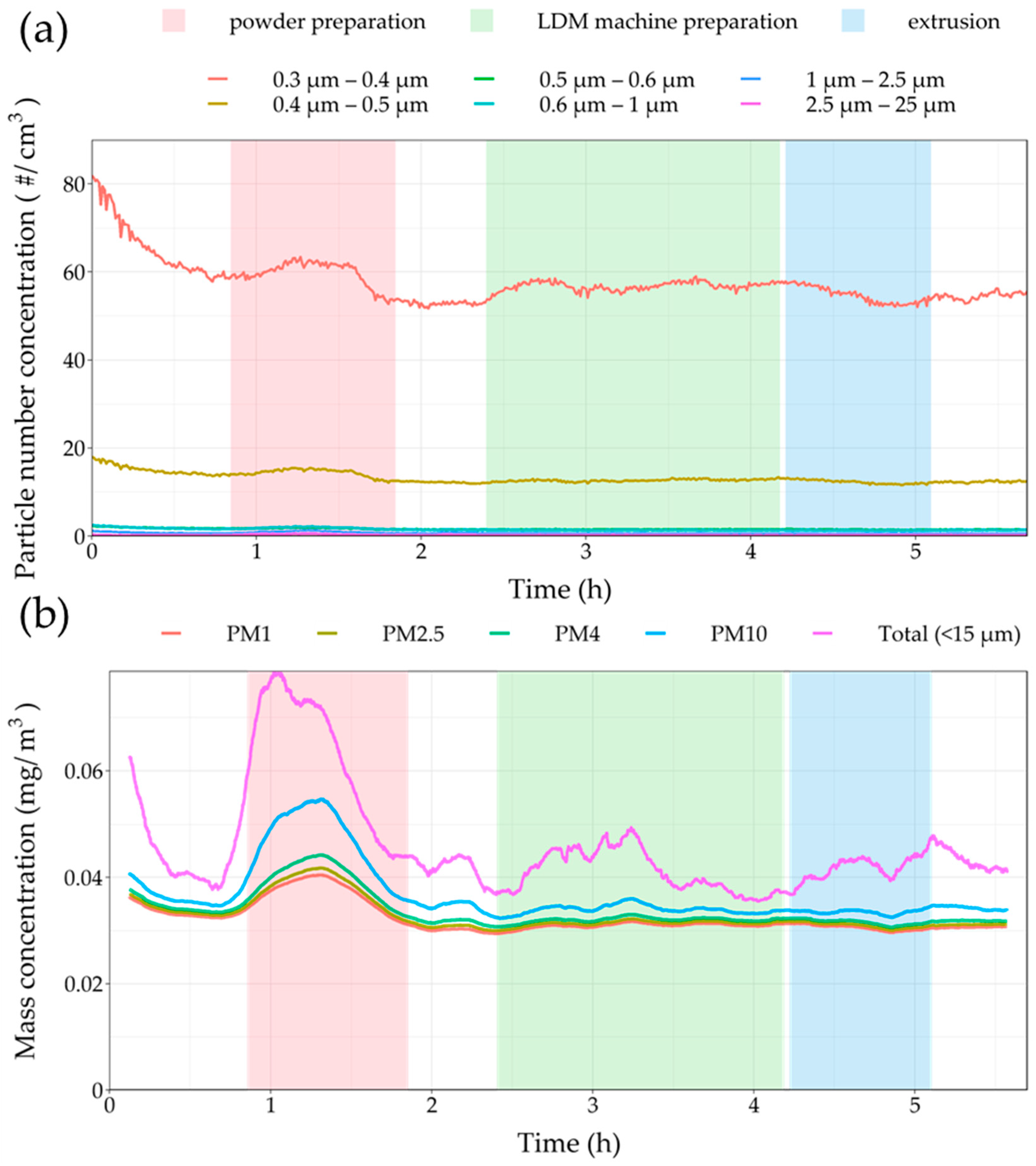

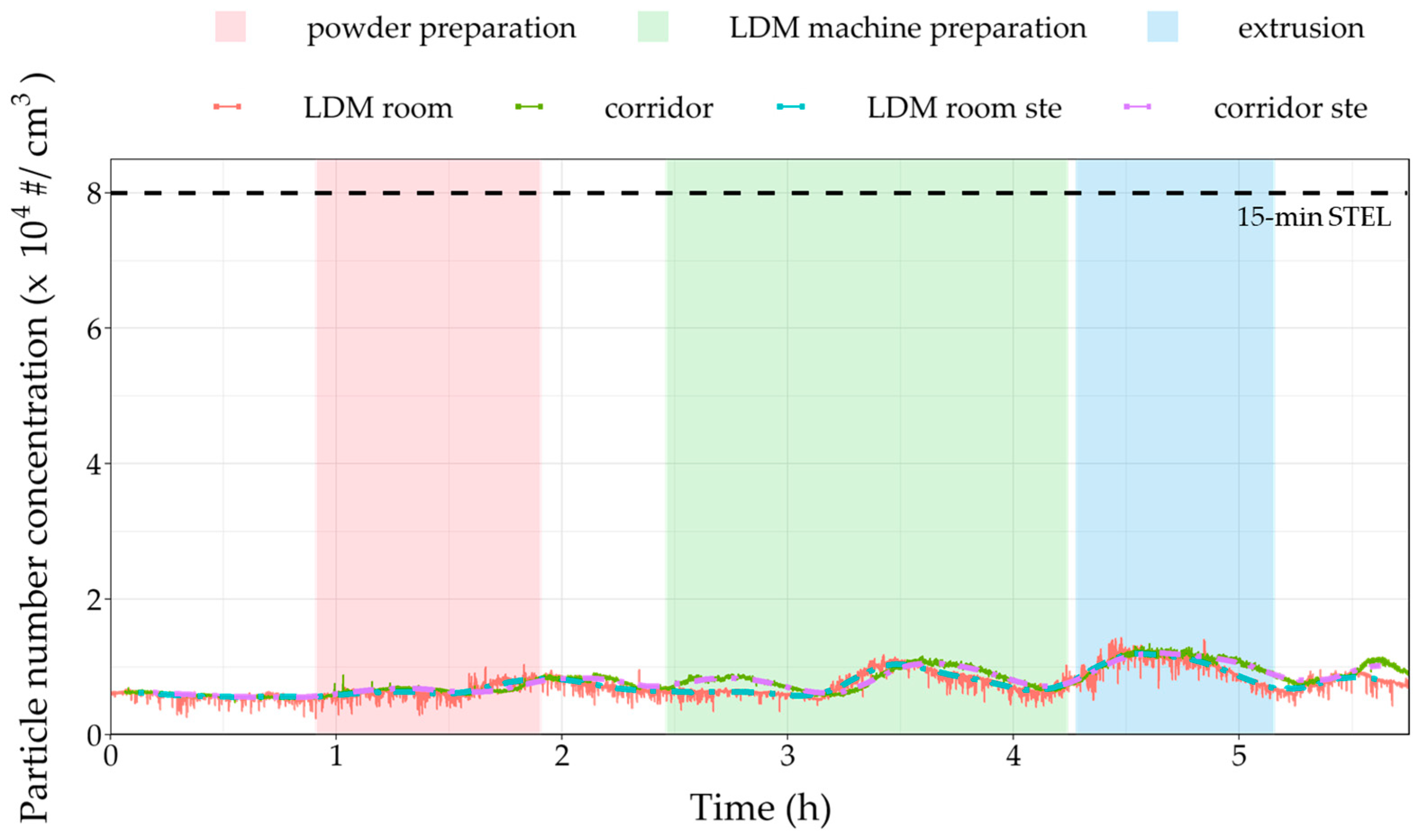

3.2. On-Site Measurements

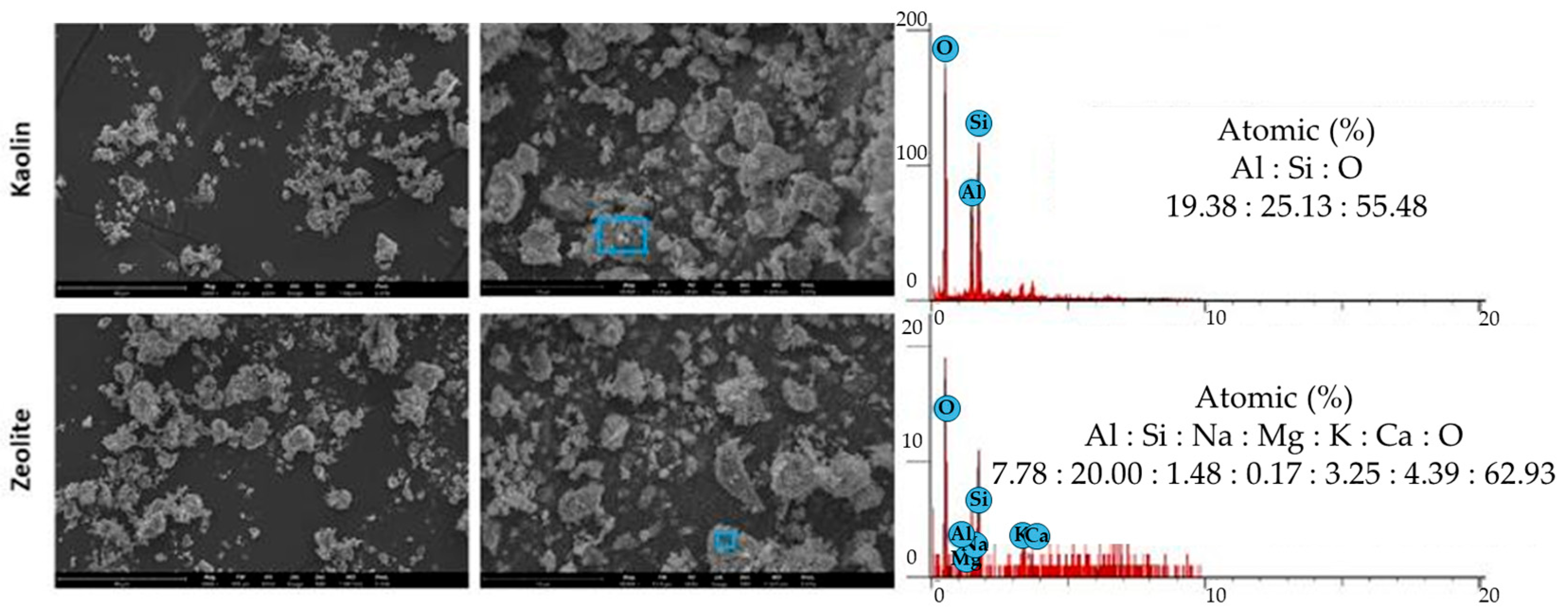

3.3. Morphological and Chemical Analysis

3.4. Toxicological Assessment

3.4.1. Toxicological Assessment of Raw Materials

3.4.2. Toxicological Assessment of Airborne Samples Collected During the Exposure Campaign

3.5. Limitations and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Ethics Statement

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

References

- Antić, J.; Mišković, Ž.; Mitrović, R.; Stamenić, Z.; Antelj, J. The Risk Assessment of 3D Printing FDM Technology. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 48, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-J.; Choi, S.-W.; Lee, E.-B. Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment During Simultaneous Operations in Industrial Plant Maintenance Based on Job Safety Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Kuntic, M.; Hahad, O.; Delogu, L.G.; Rohrbach, S.; Di Lisa, F.; Schulz, R.; Münzel, T. Effects of Air Pollution Particles (Ultrafine and Fine Particulate Matter) on Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Stress—Implications for Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 696, 108662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood-Garibay, J.A.; Angulo-Molina, A.; Méndez-Rojas, M.Á. Particulate Matter and Ultrafine Particles in Urban Air Pollution and Their Effect on the Nervous System. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 704–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-L.; Seeger, S. Systematic Ranking of Filaments Regarding Their Particulate Emissions during Fused Filament Fabrication 3D Printing by Means of a Proposed Standard Test Method. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonnalagedda, R. TerraMound—Exploration with TPMS Geometries. Available online: https://fifteen2023.bartlettarchucl.com/dfm-2023/terramound (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Gentile, V.; Vargas Velasquez, J.D.; Fantucci, S.; Autretto, G.; Gabrieli, R.; Gianchandani, P.K.; Armandi, M.; Baino, F. 3D-Printed Clay Components with High Surface Area for Passive Indoor Moisture Buffering. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, H.; Eastman, S.; Hajari, A.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Knox, J.C.; Rezaei, F. 3D-Printed Zeolite Monoliths for CO2 Removal from Enclosed Environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 27753–27761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longen, W.C.; Barcelos, L.P.; Karkle, K.K.; Schutz, F.d.S.; Valvassori, S.d.S.; Victor, E.G.; Rohr, P.; Madeira, K. Avaliação da incapacidade e qualidade de vida de trabalhadores da produção de indústrias cerâmicas. Rev. Bras. De Med. Do Trab. 2018, 16, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy Mahmoed, A.; Sobhy Abd El-Aziz, M.; Hamido Abo Sree, T. Occupational Health Hazards among Workers in Ceramic Factories. J. Nurs. Sci. Benha Univ. 2021, 2, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayannis, P.; Petrakli, F.; Gkika, A.; Koumoulos, E.P. 3D-Printed Lab-on-a-Chip Diagnostic Systems-Developing a Safe-by-Design Manufacturing Approach. Micromachines 2019, 10, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatikova, S.; Dudacek, A.; Prichystalova, R.; Klecka, V.; Kocurkova, L. Characterization of Ultrafine Particles and VOCs Emitted from a 3D Printer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzyńska, E.; Kondej, D.; Kowalska, J.; Szewczyńska, M. State of the Art in Additive Manufacturing and Its Possible Chemical and Particle Hazards—Review. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1733–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargioti, N.; Karavias, L.; Gargalis, L.; Karatza, A.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Karaxi, E.K. Physicochemical and Toxicological Properties of Particles Emitted from Scalmalloy During the LPBF Process. Toxics 2025, 13, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.C.Ø.; Harboe, H.; Brostrøm, A.; Jensen, K.A.; Fonseca, A.S. Nanoparticle Exposure and Workplace Measurements During Processes Related to 3D Printing of a Metal Object. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 608718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskov, A.; Ervik, T.K.; Tsivilskiy, I.; Gilmutdinov, A.; Thomassen, Y. Characterization of Ultrafine Particles Emitted during Laser-Based Additive Manufacturing of Metal Parts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijagic, A.; Engwall, M.; Särndahl, E.; Karlsson, H.; Hedbrant, A.; Andersson, L.; Karlsson, P.; Dalemo, M.; Scherbak, N.; Färnlund, K.; et al. Particle Safety Assessment in Additive Manufacturing: From Exposure Risks to Advanced Toxicology Testing. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 836447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.; Shineh, G.; Mobaraki, M.; Doughty, S.; Tayebi, L. Structural Parameters of Nanoparticles Affecting Their Toxicity for Biomedical Applications: A Review. J. Nanopart Res. 2023, 25, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster, G.; Oberdörster, E.; Oberdörster, J. Nanotoxicology: An Emerging Discipline Evolving from Studies of Ultrafine Particles. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larese Filon, F.; Mauro, M.; Adami, G.; Bovenzi, M.; Crosera, M. Nanoparticles Skin Absorption: New Aspects for a Safety Profile Evaluation. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 72, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzea, C.; Pacheco, I.I.; Robbie, K. Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles: Sources and Toxicity. Biointerphases 2007, 2, MR17–MR71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifemeje, J.C.; Udedi, S.C.; Okechukwu, A.U.; Nwaka, A.C.; Lukong, C.B.; Anene, I.N.; Egbuna, C.; Ezeude, I.C. Determination of Total Protein, Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase Activity and Lipid Peroxidation in Soil Macro-Fauna (Earthworm) from Onitsha Municipal Open Waste Dump. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2015, 6, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdal Dayem, A.; Hossain, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.; Saha, S.; Yang, G.-M.; Choi, H.; Cho, S.-G. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the Biological Activities of Metallic Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manke, A.; Wang, L.; Rojanasakul, Y. Mechanisms of Nanoparticle-Induced Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 942916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olympus Minerals Olympus Minerals. XRD Analysis of Greek Zeolite Performed by The Mineral Lab, Inc. 2017. Available online: https://olympus-minerals.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/XRD-ANALYSIS-OF-GREEK-ZEOLITE-PERFORMED-BY-THE-MINERAL-LAB-INC.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Prolat. Kaolin Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.prolat.gr/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Kaolin-Prolat_tds_en_v3_2021.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Harmonized Tiered Approach to Measure and Assess the Potential Exposure to Airborne Emissions of Engineered Nano-Objects and Their Agglomerates and Aggregates at Workplaces; ENV/JM/MONO(2015)19; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/TS 12901-2:2014; Nanotechnologies—Occupational Risk Management Applied to Engineered Nanomaterials—Part 2: Use of the Control Banding Approach. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Great Britain; Health and Safety Executive (HSE). COSHH Essentials, Easy Steps to Control Health Risks from Chemicals. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250122040128/http://coshh-tool.hse.gov.uk/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- GESTIS International Limit Values. Available online: https://limitvalue.ifa.dguv.de/ (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- van Broekhuizen, P.; van Veelen, W.; Streekstra, W.-H.; Schulte, P.; Reijnders, L. Exposure Limits for Nanoparticles: Report of an International Workshop on Nano Reference Values. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2012, 56, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baybutt, P. The ALARP Principle in Process Safety. Process Saf. Prog. 2014, 33, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, R.J.; Capes-Davis, A.; Davis, J.M.; Downward, J.; Freshney, R.I.; Knezevic, I.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Masters, J.R.W.; Meredith, J.; Stacey, G.N.; et al. Guidelines for the Use of Cell Lines in Biomedical Research. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1021–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Pardo, M.; Rudich, Y.; Kaplan-Ashiri, I.; Wong, J.P.S.; Davis, A.Y.; Black, M.S.; Weber, R.J. Chemical Composition and Toxicity of Particles Emitted from a Consumer-Level 3D Printer Using Various Materials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12054–12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C&L Inventory—ECHA—Quartz. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/en/information-on-chemicals/cl-inventory-database/-/discli/details/54394 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- ASHRAE Technical Committee 9.10, Laboratory Systems (Ed.). Classification of Laboratory Ventilation Design Levels; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ribalta, C.; López-Lilao, A.; Estupiñá, S.; Fonseca, A.S.; Tobías, A.; García-Cobos, A.; Minguillón, M.C.; Monfort, E.; Viana, M. Health Risk Assessment from Exposure to Particles during Packing in Working Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattenklott, M.; Pflaumbaum, W.; Smola, T.; Stamm, R.; Steinhausen, M.; Binde, G. IFA Report 6/2020e: Occupational Exposure to Inhalable and Respirable Dust Fractions; Deutsche Gesetzliche Unfallversicherung e.V. (DGUV): Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Azarmi, F.; Kumar, P.; Mulheron, M. The Exposure to Coarse, Fine and Ultrafine Particle Emissions from Concrete Mixing, Drilling and Cutting Activities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 279, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.F.; Miranda, R.M.; Oliveira, J.P.; Esteves, H.M.; Albuquerque, P.C. Evaluation of the Amount of Nanoparticles Emitted in LASER Additive Manufacture/Welding. Inhal. Toxicol. 2019, 31, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Wu, J.; Faccinetto, A.; Grimonprez, S.; Batut, S.; Yon, J.; Desgroux, P.; Petitprez, D. Influence of the Dry Aerosol Particle Size Distribution and Morphology on the Cloud Condensation Nuclei Activation. An Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 4209–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.R.; Schulthess, C.P. The Nanopore Inner Sphere Enhancement Effect on Cation Adsorption: Sodium, Potassium, and Calcium. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Gogvadze, V.; Orrenius, S.; Zhivotovsky, B. Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. Apoptosis 2007, 12, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-H.; Kumar, M.; Kim, I.W.; Rimer, J.D.; Kim, T.-J. A Comparative Analysis of In Vitro Toxicity of Synthetic Zeolites on IMR-90 Human Lung Fibroblast Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsabad, F.N.; Salehi, M.H.; Shams, J.; Ghazanfari, T. Cytotoxicity of Bentonite, Zeolite, and Sepiolite Clay Minerals on Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Immunoregulation 2023, 5, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, M.; Yoneda, R.; Totsuka, Y.; Yagi, T. Genotoxicity of Micro- and Nano-Particles of Kaolin in Human Primary Dermal Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts. Genes Environ. 2020, 42, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, O.Y.; Alikina, Y.A.; Brazovskaya, E.Y. Particles Morphology Impact on Cytotoxicity, Hemolytic Activity and Sorption Properties of Porous Aluminosilicates of Kaolinite Group. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitochondria in Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Aging: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Advances|Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-025-02253-4 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory Responses and Inflammation-Associated Diseases in Organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in Immunoregulation and Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, F. Diverse Roles of Lung Macrophages in the Immune Response to Influenza A Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1260543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussbacher, M.; Derler, M.; Basílio, J.; Schmid, J.A. NF-κB in Monocytes and Macrophages—An Inflammatory Master Regulator in Multitalented Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1134661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Tang, P.S.; Chan, W.C.W. The Effect of Nanoparticle Size, Shape, and Surface Chemistry on Biological Systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhalim, A.; Melegy, A.; Othman, D. Assessment of Synthetic Zeolites from Kaolin and Bentonite Clays for Wastewater and Fuel Gases Treatment. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2025, 227, 105621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. Factors Involved in the Cytotoxicity of Kaolinite towards Macrophages in Vitro. Environ. Health Perspect. 1983, 51, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guo, B.; Zebda, R.; Drake, S.J.; Sayes, C.M. Synergistic Effect of Co-Exposure to Carbon Black and Fe2O3 Nanoparticles on Oxidative Stress in Cultured Lung Epithelial Cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2009, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Park, K.; Kim, I.; Kim, S.D. Combined Toxic Effect of Airborne Heavy Metals on Human Lung Cell Line A549. Environ. Geochem. Health 2018, 40, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Toyooka, T.; Ibuki, Y.; Masuda, S.; Watanabe, M.; Totsuka, Y. Effect of Physicochemical Character Differences on the Genotoxic Potency of Kaolin. Genes Environ. 2017, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awashra, M.; Młynarz, P. The Toxicity of Nanoparticles and Their Interaction with Cells: An in Vitro Metabolomic Perspective. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 2674–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytting, V.S.; Refsnes, M.; Låg, M.; Erichsen, E.; Røhr, T.S.; Snilsberg, B.; White, R.A.; Øvrevik, J. The Importance of Mineralogical Composition for the Cytotoxic and Pro-Inflammatory Effects of Mineral Dust. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemann, M.; Vennemann, A.; Wohlleben, W. Lung Toxicity Analysis of Nano-Sized Kaolin and Bentonite: Missing Indications for a Common Grouping. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seihei, N.; Farhadi, M.; Takdastan, A.; Asban, P.; Kiani, F.; Mohammadi, M.J. Short-Term and Long-Term Effects of Exposure to PM10. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 27, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, F.; Janssen, N.A.; Wesseling, J.; van Ratingen, S.; Strak, M.; Kerckhoffs, J.; Gehring, U.; Hendricx, W.; de Hoogh, K.; Vermeulen, R.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Ultrafine Particles and Natural and Cause-Specific Mortality. Environ. Int. 2023, 175, 107960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, J.I.; Gać, P. Short-Term and Long-Term Effects of Inhaled Ultrafine Particles on Blood Markers of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, J.I.; Gać, P. Short- and Long-Term Effects of Inhaled Ultrafine Particles on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, M.D.; Stefaniak, A.B.; Day, G.A.; Geraci, C.L. Exposure Assessment Considerations for Nanoparticles in the Workplace. In Nanotoxicology: Characterization, Dosing, and Health Effects; Informa healthcare: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ahire, S.A.; Bachhav, A.A.; Pawar, T.B.; Jagdale, B.S.; Patil, A.V.; Koli, P.B. The Augmentation of Nanotechnology Era: A Concise Review on Fundamental Concepts of Nanotechnology and Applications in Material Science and Technology. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Fan, J.; Claudel, M.; Sonntag, T.; Didier, P.; Ronzani, C.; Lebeau, L.; Pons, F. Density of Surface Charge Is a More Predictive Factor of the Toxicity of Cationic Carbon Nanoparticles than Zeta Potential. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honary, S.; Zahir, F. Effect of Zeta Potential on the Properties of Nano-Drug Delivery Systems—A Review (Part 1). Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 12, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoid, G.M.; Cohen, J.M.; Pyrgiotakis, G.; Pirela, S.V.; Pal, A.; Liu, J.; Srebric, J.; Demokritou, P. Advanced Computational Modeling for in Vitro Nanomaterial Dosimetry. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, F.; Ozaki, M. Evaluation of VOC Emissions from Electrical Components. FUJITSU Sci. Tech. J. 2025, 45, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kienzler, A.; Bopp, S.K.; van der Linden, S.; Berggren, E.; Worth, A. Regulatory Assessment of Chemical Mixtures: Requirements, Current Approaches and Future Perspectives. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 80, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damilos, S.; Saliakas, S.; Karasavvas, D.; Koumoulos, E.P. An Overview of Tools and Challenges for Safety Evaluation and Exposure Assessment in Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Measurement Type | Size Range | Cutoffs | Flow Rate | Sampling Rate | Log Interval | Uncertainty Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPC 3007, TSI | Particle number concentration | 10 nm–1 μm | - | 0.7 L/min | 1 s | 1 s | 20% |

| Aerotrak 9306-V2, TSI | Particle number concentration | 300 nm–25 μm | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 1, 2.5) μm | 2.83 L/min | 1 s (for 40 s followed by 20 s reset) | 1 min | 10% |

| DustTrak DRX 8534, TSI | Particle mass concentration | 100 nm–15 μm | (1, 2.5, 4, 10) μm | 3 L/min | 1 s | 1 min | 10% |

| Substance | Limit (mg/m3) | Authority |

|---|---|---|

| respirable dust | TWA: 5 STE: 10 | Austria |

| TWA: 3 | Belgium, Spain, Switzerland | |

| TWA: 1.25 | Germany | |

| TWA: 6 | Hungary | |

| TWA: 4 | Ireland | |

| TWA: 0.9 | France | |

| TWA: 5 | USA | |

| kaolin (respirable) | TWA: 2 | Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Spain |

| TWA: 10 | France, Poland | |

| zeolite | TWA: 2 | Latvia |

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | CD54 | AGCGGCTGACGTGTGCAGTAAT | TCTGAGACCTCTGGCTTCGTCA |

| CD86 | CCATCAGCTTGTCTGTTTCATTCC | GCTGTAATCCAAGGAATGTGGTC | |

| IL-18 | GATAGCCAGCCTAGAGGTATGG | CCTTGATGTTATCAGGAGGATTCA | |

| TNFa | CTCTTCTGCCTGCTGCACTTTG | ATGGGCTACAGGCTTGTCACTC | |

| IL-6 | AGACAGCCACTCACCTCTTCAG | TTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTTGCTG | |

| Endogenous control | PMAIP1 | CTGGAAGTCGAGTGTGCTACTC | TGAAGGAGTCCCCTCATGCAAG |

| GAPDH | GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG | ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA |

| Material | Hazard Band | |

|---|---|---|

| ISO/TS 12901-2 | COSHH E-Tool | |

| Kaolin | A | Not classified |

| Zeolite | A | Not classified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saliakas, S.; Glynou, V.; Prokopiou, D.E.; Argyrou, A.; Tsiokou, V.; Damilos, S.; Karatza, A.; Koumoulos, E.P. A Tiered Occupational Risk Assessment for Ceramic LDM: On-Site Exposure, Particle Morphology and Toxicity of Kaolin and Zeolite Feedstocks. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110367

Saliakas S, Glynou V, Prokopiou DE, Argyrou A, Tsiokou V, Damilos S, Karatza A, Koumoulos EP. A Tiered Occupational Risk Assessment for Ceramic LDM: On-Site Exposure, Particle Morphology and Toxicity of Kaolin and Zeolite Feedstocks. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2025; 9(11):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110367

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaliakas, Stratos, Vasiliki Glynou, Danai E. Prokopiou, Aikaterini Argyrou, Vaia Tsiokou, Spyridon Damilos, Anna Karatza, and Elias P. Koumoulos. 2025. "A Tiered Occupational Risk Assessment for Ceramic LDM: On-Site Exposure, Particle Morphology and Toxicity of Kaolin and Zeolite Feedstocks" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 9, no. 11: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110367

APA StyleSaliakas, S., Glynou, V., Prokopiou, D. E., Argyrou, A., Tsiokou, V., Damilos, S., Karatza, A., & Koumoulos, E. P. (2025). A Tiered Occupational Risk Assessment for Ceramic LDM: On-Site Exposure, Particle Morphology and Toxicity of Kaolin and Zeolite Feedstocks. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 9(11), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9110367