Effects of Binder Saturation and Drying Time in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing on Dimensional Deviation and Density of SiC Green Parts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Method

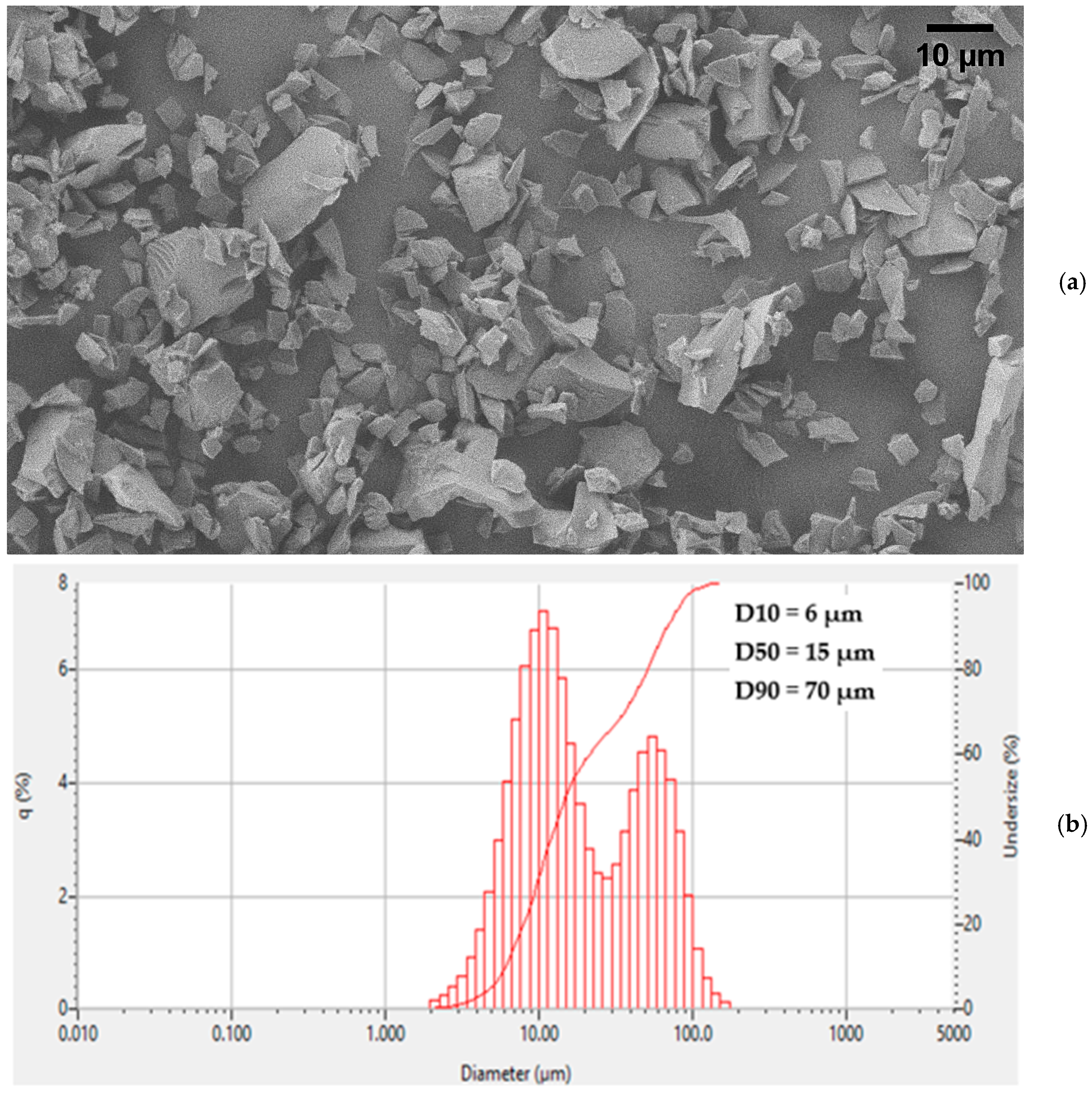

2.1. Feedstock Material

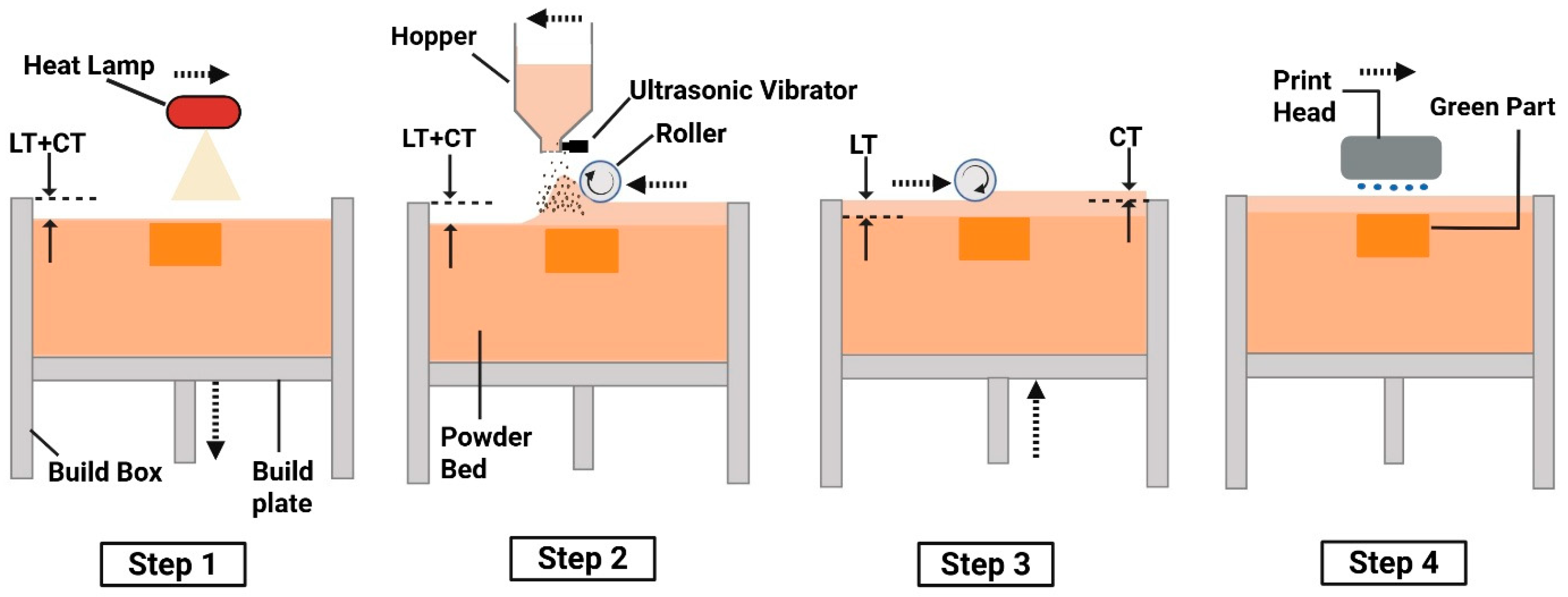

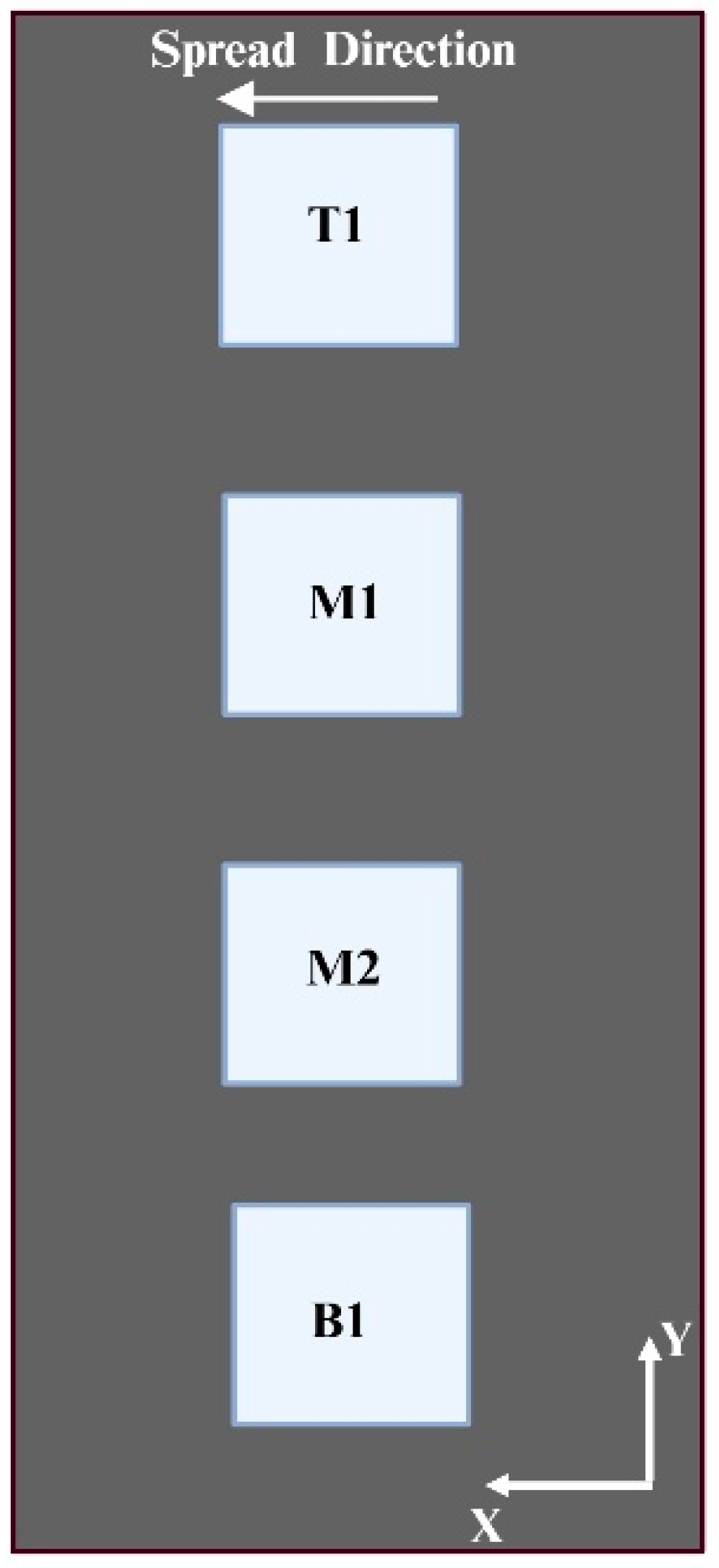

2.2. Binder Jetting of Green Parts

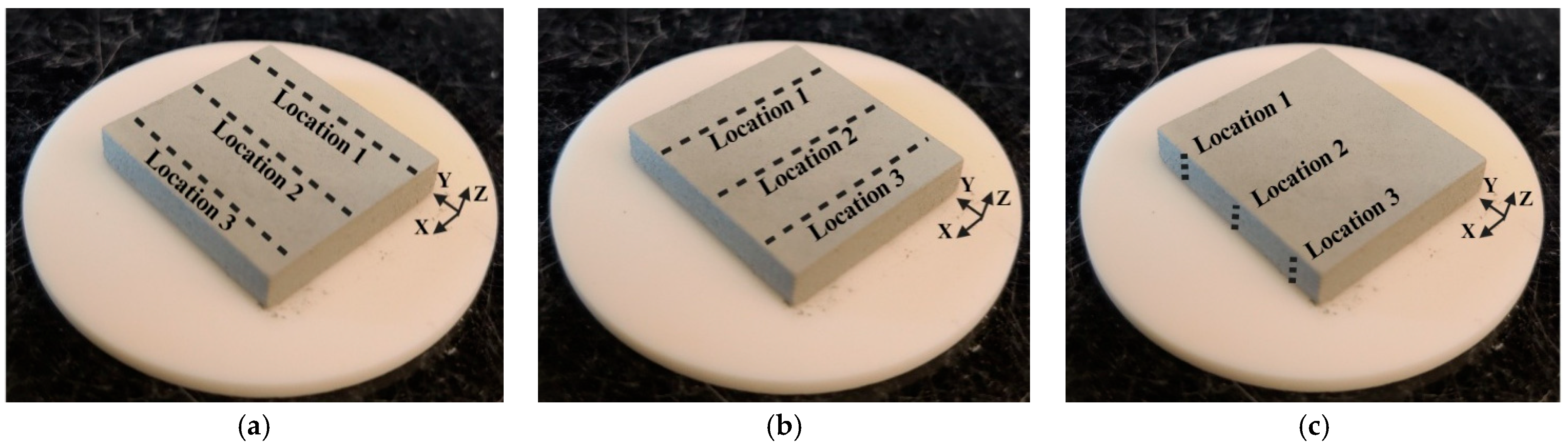

2.3. Measurement of Dimensional Deviation of Green Parts

2.4. Measurement of Density of Green Parts

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Binder Saturation

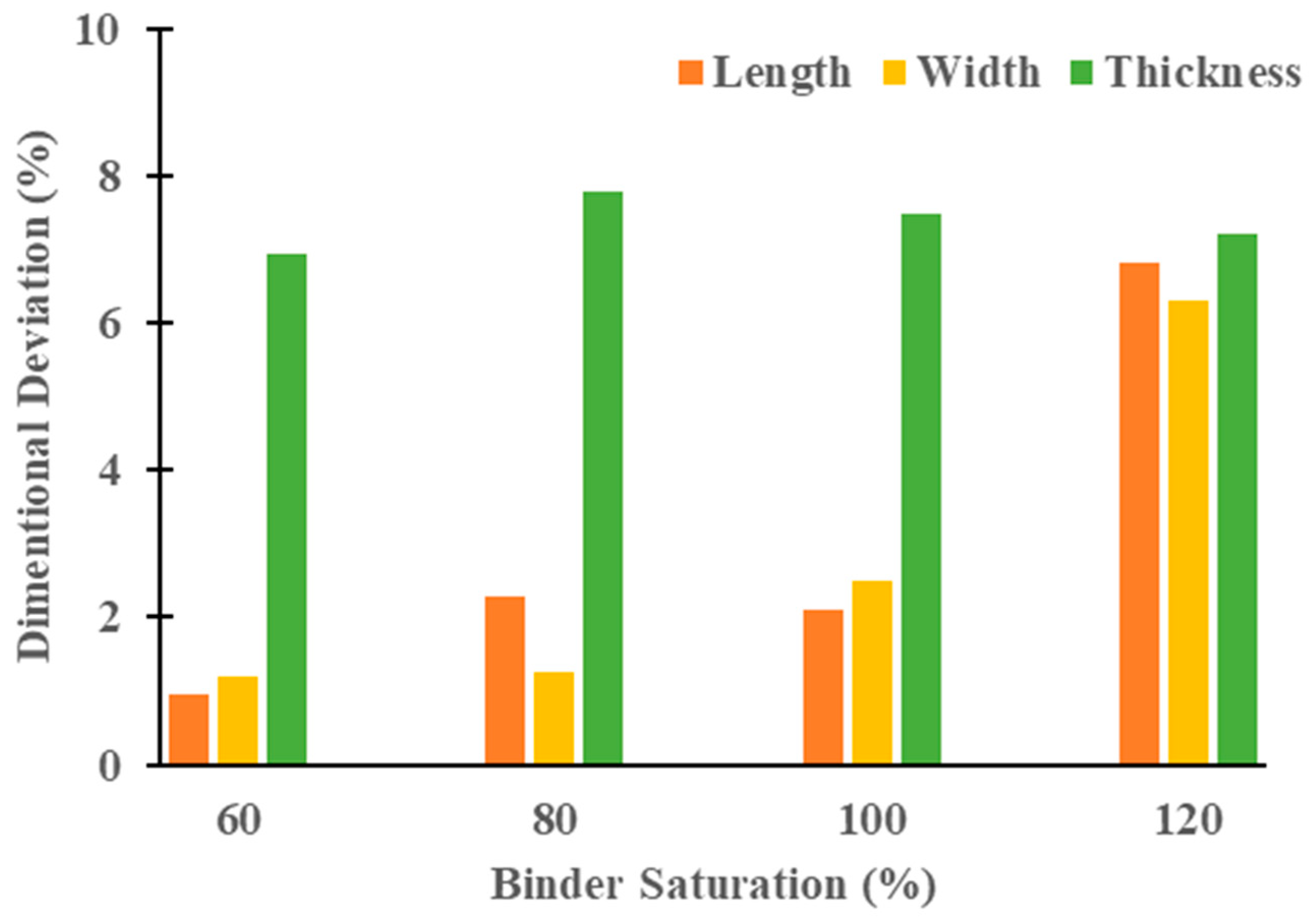

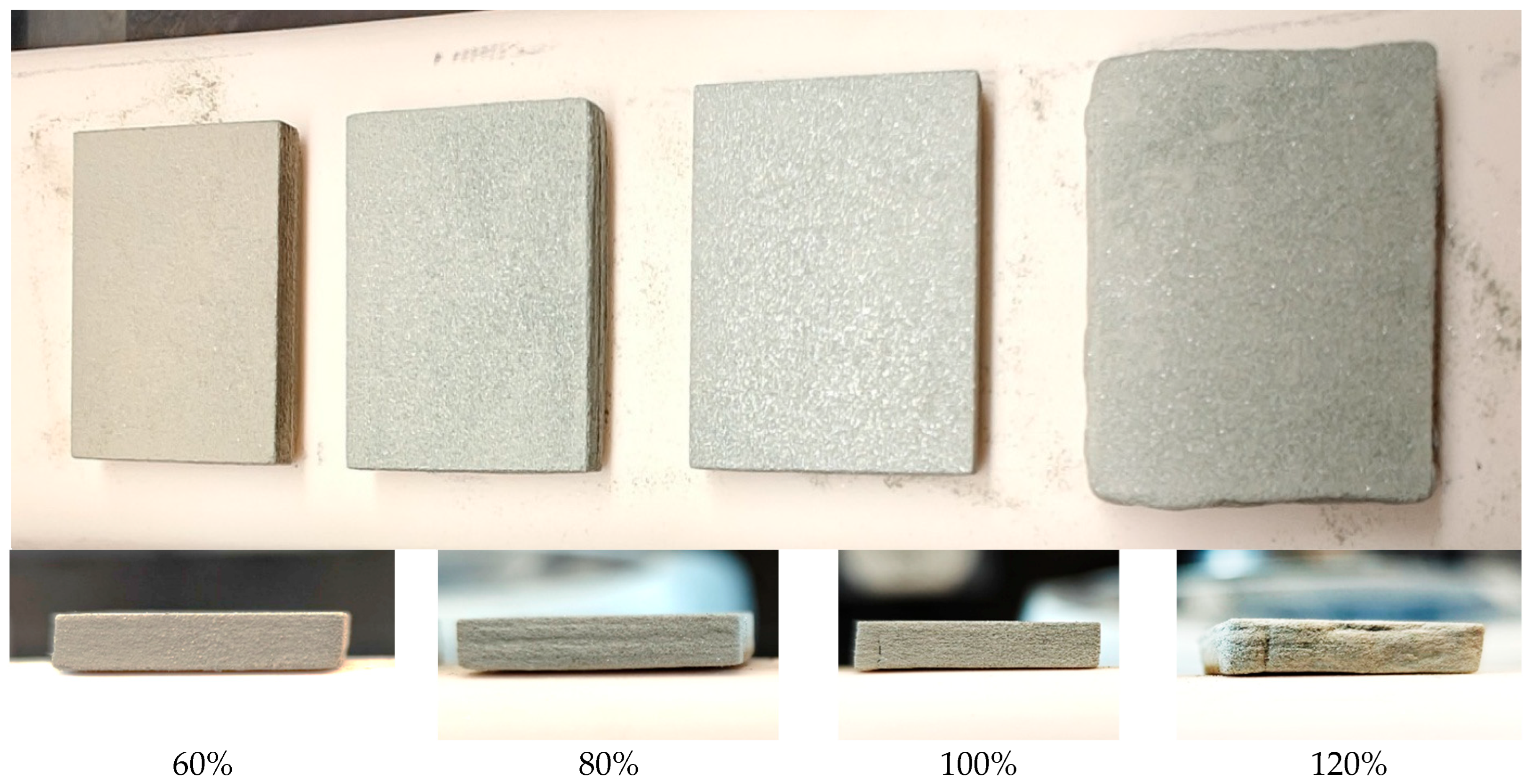

3.1.1. Effect of Binder Saturation on Dimensional Deviation of Green Parts

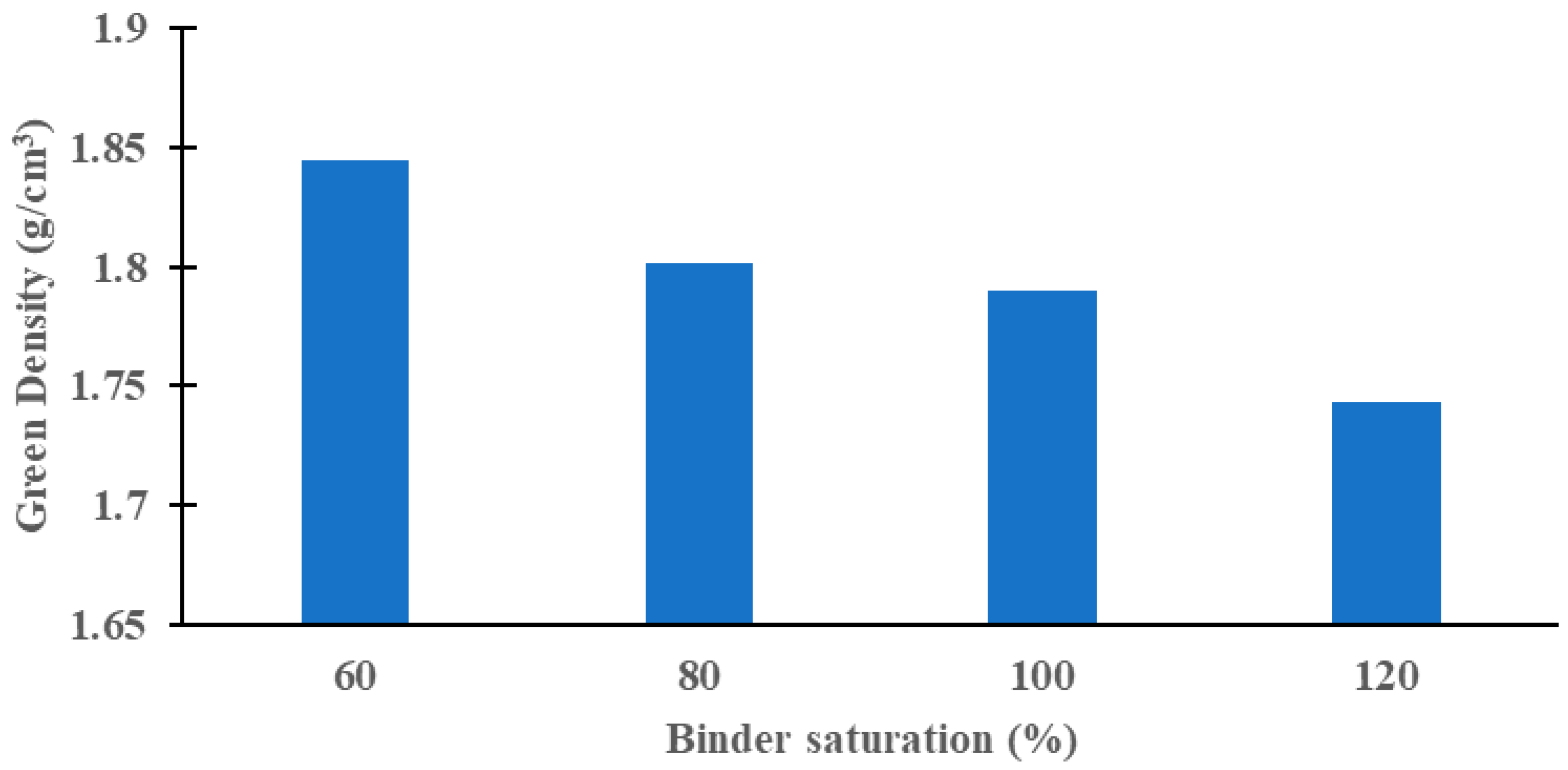

3.1.2. Effect of Binder Saturation on Density of Green Parts

3.2. Effect of Drying Time

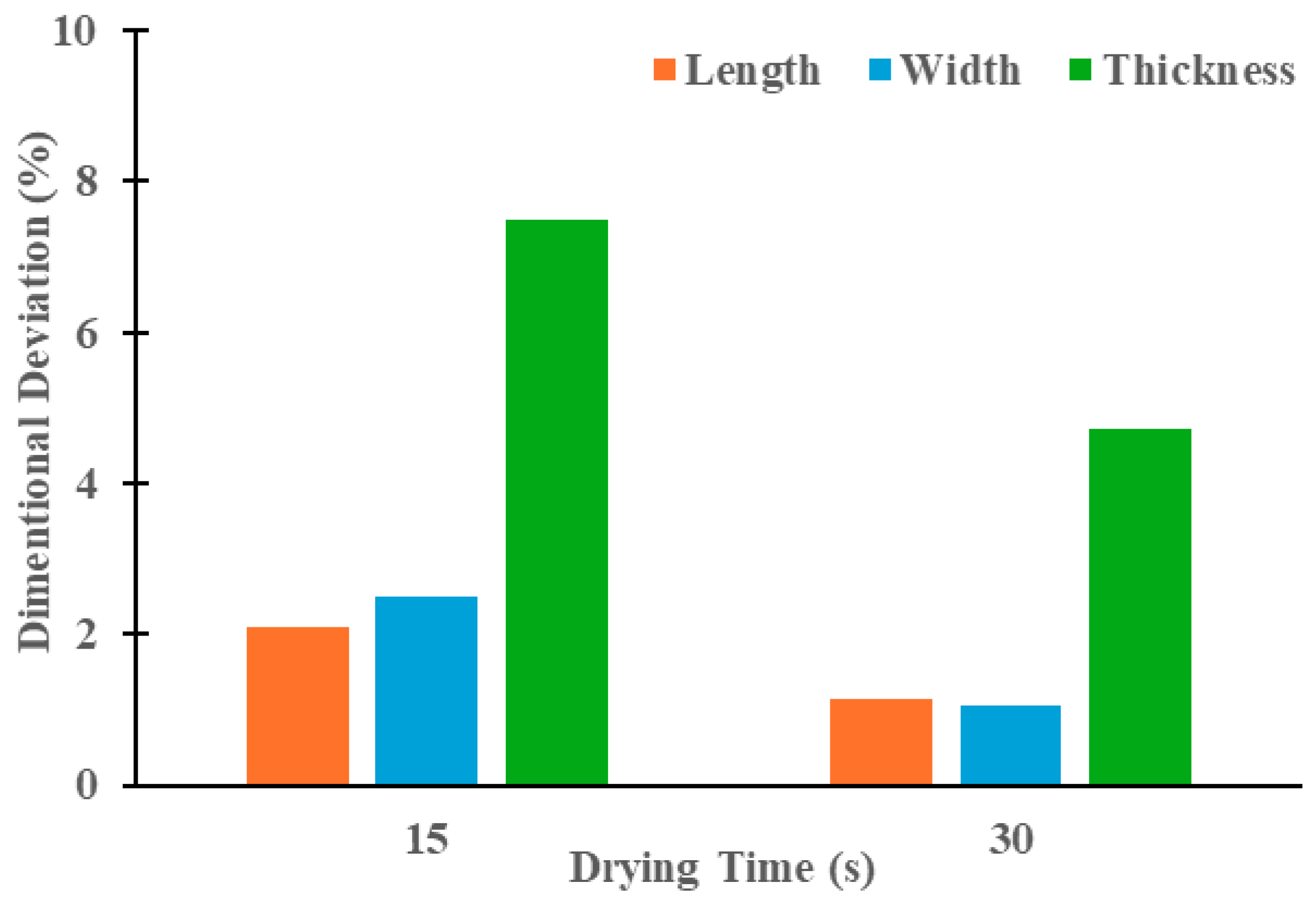

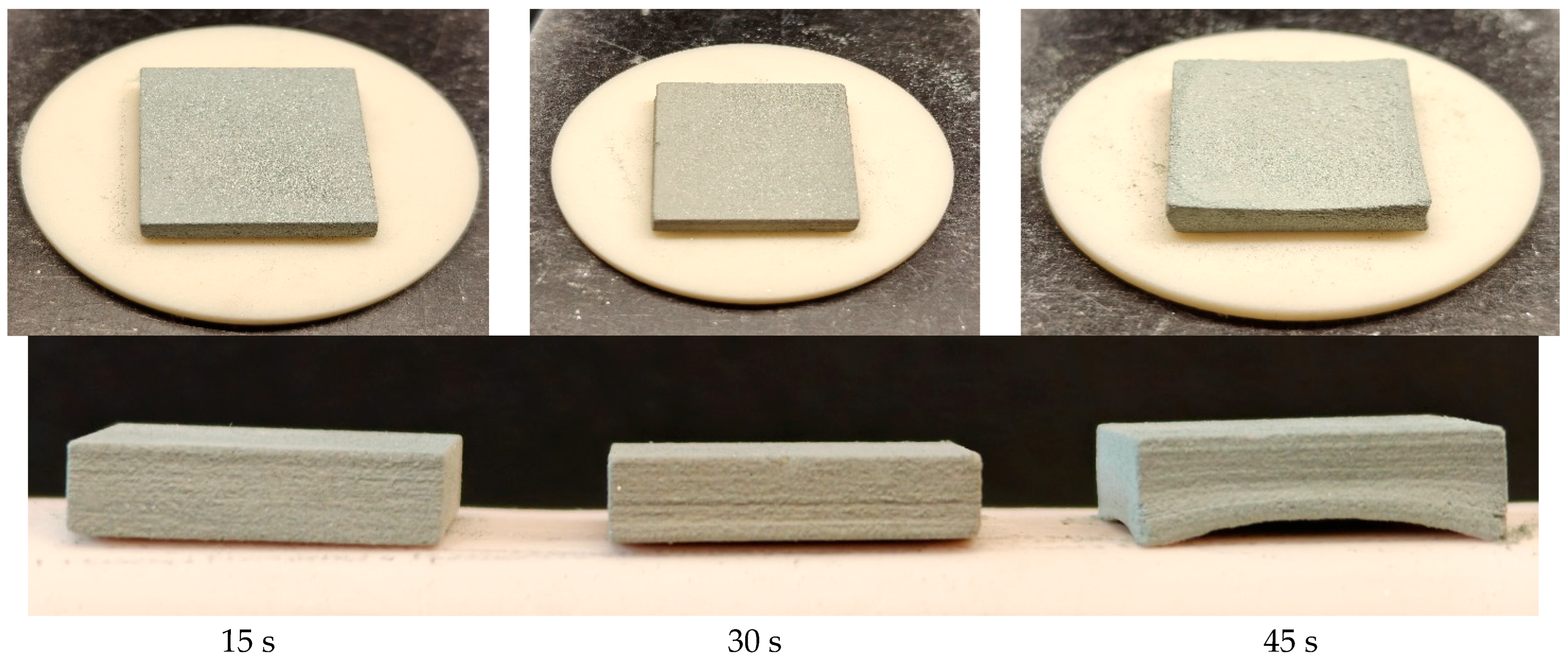

3.2.1. Effect of Drying Time on Dimensional Deviation of Green Parts

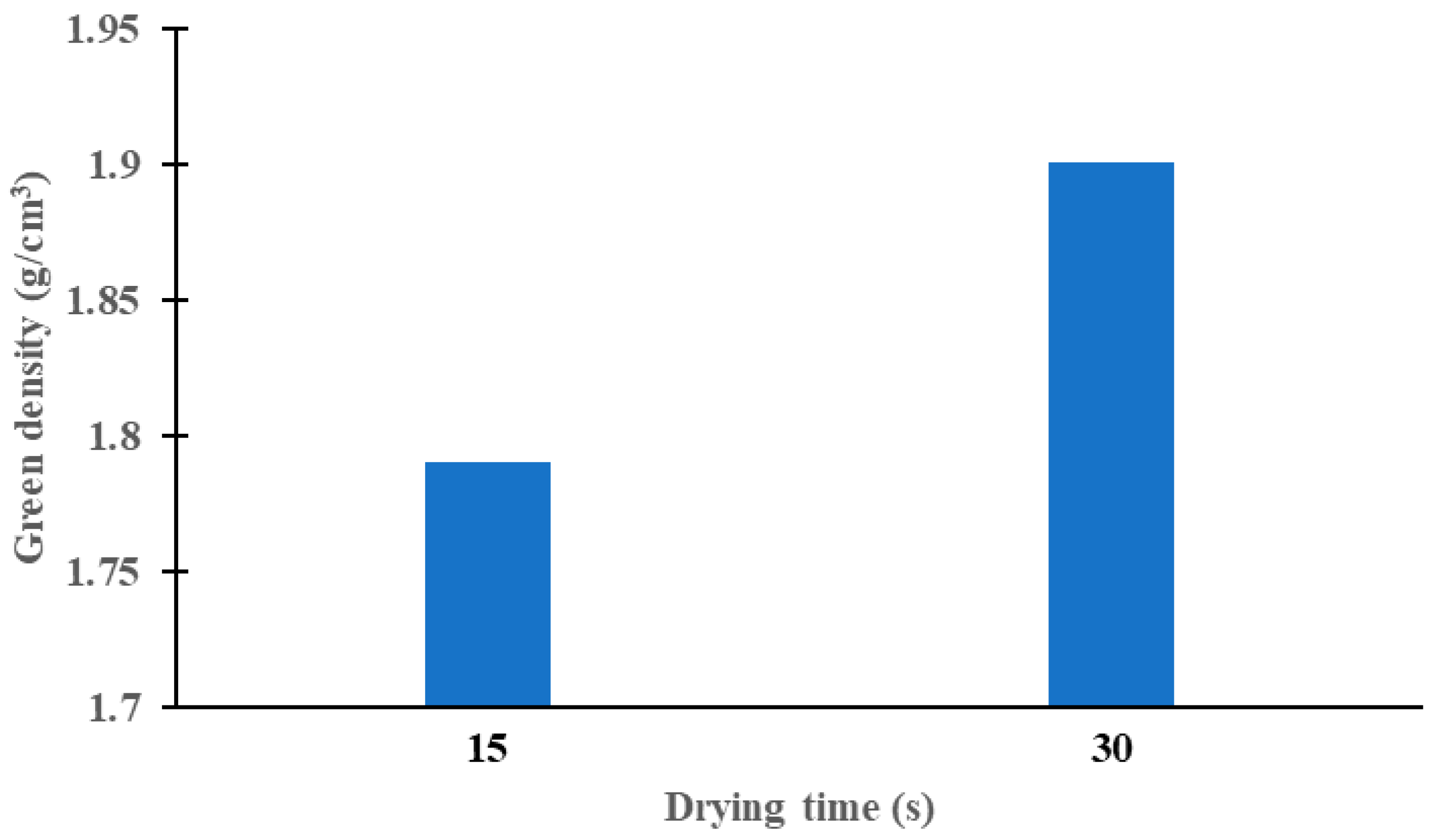

3.2.2. Effect of Drying Time on Density of Green Parts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boretti, A.; Castelletto, S. A perspective on 3D printing of silicon carbide. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-W.; Raju, S. Processing and properties of macroporous silicon carbide ceramics: A review. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2013, 1, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polozov, I.; Razumov, N.; Masaylo, D.; Silin, A.; Lebedeva, Y.; Popovich, A. Fabrication of silicon carbide fiber-reinforced silicon carbide matrix composites using binder jetting additive manufacturing from irregularly-shaped and spherical powders. Materials 2020, 13, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steibel, J. Ceramic matrix composites taking flight at GE Aviation. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull 2019, 98, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D. Aerospace Ceramic Materials: Thermal, Environmental Barrier Coatings and SiC/SiC Ceramic Matrix Composites for Turbine Engine Applications; Glenn Research Center: Sandusky, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Ma, H.; Yang, W. Advances in modifications and high-temperature applications of silicon carbide ceramic matrix composites in aerospace: A focused review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 4671–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C.L.; Elliott, A.M.; Lara-Curzio, E.; Flores-Betancourt, A.; Lance, M.J.; Han, L.; Blacker, J.; Trofimov, A.A.; Wang, H.; Cakmak, E. Properties of SiC-Si made via binder jet 3D printing of SiC powder, carbon addition, and silicon melt infiltration. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 5467–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrani, K.; Jolly, B.; Trammell, M. 3D printing of high-purity silicon carbide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocca, A.; Lima, P.; Diener, S.; Katsikis, N.; Günster, J. Additive manufacturing of SiSiC by layerwise slurry deposition and binder jetting (LSD-print). J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Arman, M.S.; Sanders, J.; Pasha, M.M.; Rahman, A.M.; Pei, Z.; Dong, T. Binder Jetting 3D Printing Utilizing Waste Algae Powder: A Feasibility Study. Intell. Sustain. Manuf. 2024, 1, 10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, A.; Elliott, A.M.; Barnes, J.E.; Li, F.; Tan, W.; Cramer, C.L.; Nandwana, P.; Chmielus, M. Binder jet 3D printing—Process parameters, materials, properties, modeling, and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 119, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanaji, H.; Zhang, S.; Lassell, A.; Zandinejad, A.; Yang, L. Process development of porcelain ceramic material with binder jetting process for dental applications. JOM 2016, 68, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytan, S.; Cadena, M.; Karim, H.; Delfin, D.; Lin, Y.; Espalin, D.; MacDonald, E.; Wicker, R. Fabrication of barium titanate by binder jetting additive manufacturing technology. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 6610–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, N.B. Impact of part thickness and drying conditions on saturation limits in binder jet additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 33, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, A.; De Vecchis, P.R.; Kimes, K.A.; Elhassid, D.; Chmielus, M. Effect of binder saturation and drying time on microstructure and resulting properties of sinter-HIP binder-jet 3D-printed WC-Co composites. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, H.; Jiang, C.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, L.; Yang, P.; Deng, X.; Wu, S. Preparation of high-strength ZrO2 ceramics by binder jetting additive manufacturing and liquid glass infiltration. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 44175–44185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanaji, H.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L. A new physics-based model for equilibrium saturation determination in binder jetting additive manufacturing process. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2018, 124, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Reynolds, W.T. 3DP process for fine mesh structure printing. Powder Technol. 2008, 187, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.; Chua, C.K. Effects of layer thickness and binder saturation level parameters on 3D printing process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 53, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enneti, R.K.; Prough, K.C. Effect of binder saturation and powder layer thickness on the green strength of the binder jet 3D printing (BJ3DP) WC-12% Co powders. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 84, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Song, X.; Tian, R.; Lei, Y.; Long, W.; Zhong, S.; Feng, J. Wettability and joining of SiC by Sn-Ti: Microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, M.M.; Arman, M.S.; Pei, Z.; Khan, F.; Sanders, J.; Kachur, S. Effects of Compaction Thickness on Density, Integrity, and Microstructure of Green Parts in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing of Silicon Carbide. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, M.M.; Arman, M.S.; Khan, F.; Pei, Z.; Kachur, S. Effects of Layer Thickness and Compaction Thickness on Green Part Density in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing of Silicon Carbide: Designed Experiments. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, R.D.; Edwards, D.J. Bayesian D-optimal screening experiments with partial replication. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2017, 115, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorula, M.; Khademitab, M.; Jamalkhani, M.; Mostafaei, A. Location dependency of green density and dimension variation in binder jetted parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 2853–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, K.J.; Nychka, J.A.; Chalaturnyk, R.J. Process limitations of 3D printing model rock. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Powder Material | Particle Size Distribution (μm) | Layer Thickness (μm) | Binder Saturation (%) | Drying Time (s) | Response Variable | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barium titanate (BaTiO3) | 0.85–1.45 | 30 | 60, 75, 120 | N/A | Density of sintered parts | [13] |

| Plaster (gypsum)-based ZP102 | N/A | 100 and 87 | 90, 125 | N/A | Surface quality, dimensional deviation, and strength of sintered parts | [19] |

| Porcelain | 10 to 30 | N/A | 50, 75 | 30, 45, 60 | Dimensional deviation and strength of green parts | [12] |

| 420 and 316 stainless steel | 25.5–63.2, 9.8–35 | 100 | 30–140 | 12 | Density of sintered parts | [14] |

| Ti-6Al-4V, 420 stainless steel | average 32 and 35, respectively | N/A | 50, 100 | 40 | Dimensional deviation of sintered parts | [17] |

| TiNiHf shape memory alloy | 2.5–20, mean 5.50 | 20, 35, 50 | N/A | 60 | Strength and dimensional deviation of green parts | [18] |

| Tungsten carbide (WC)-12% cobalt (Co) | 18.8–39.5 | 50, 60, and 70 | 40, 65, and 75 | 7 | Strength of green parts | [20] |

| WC-Co composite | particle sizes < 63 | 100 | 100, 150, 175, 200, 225, 250 | 30, 45 | Density of green parts, density and strength of sintered parts | [15] |

| Zirconia (ZrO2) | mean 63.1 | 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 | 7 to 17 | N/A | Dimensional deviation, density, and strength of green parts | [16] |

| Printing Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Layer Thickness (µm) | 60 |

| Compaction Thickness (µm) | 50 |

| Roller traverse speed during compaction (mm/s) | 5 |

| Roller rotation speed during spreading (rpm) | 300 |

| Roller traverse speed during spreading (mm/s) | 15 |

| Ultrasonic intensity (%) | 100 |

| Bed temperature (°C) | 50 |

| Binder set time (s) | 30 |

| Packing rate (%) | 52 |

| Experimental Condition | Binder Saturation (%) | Drying Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 15 |

| 2 | 80 | 15 |

| 3 | 100 | 15 |

| 4 | 120 | 15 |

| 5 | 100 | 30 |

| 6 | 100 | 45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pasha, M.M.; Pei, Z.; Arman, M.S.; Kachur, S. Effects of Binder Saturation and Drying Time in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing on Dimensional Deviation and Density of SiC Green Parts. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2026, 10, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10010026

Pasha MM, Pei Z, Arman MS, Kachur S. Effects of Binder Saturation and Drying Time in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing on Dimensional Deviation and Density of SiC Green Parts. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2026; 10(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10010026

Chicago/Turabian StylePasha, Mostafa Meraj, Zhijian Pei, Md Shakil Arman, and Stephen Kachur. 2026. "Effects of Binder Saturation and Drying Time in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing on Dimensional Deviation and Density of SiC Green Parts" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 10, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10010026

APA StylePasha, M. M., Pei, Z., Arman, M. S., & Kachur, S. (2026). Effects of Binder Saturation and Drying Time in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing on Dimensional Deviation and Density of SiC Green Parts. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 10(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10010026