This section presents a detailed evaluation of the proposed CVML framework, focusing on two aspects: the accuracy of cross-view ground–aerial image matching using VSCM-Net, and the cross-view localization performance of CVML in real-world environments. To validate the proposed algorithm, two datasets were employed, one is the publicly available CVIAN dataset [

27], and another one is a self-constructed low-altitude cross-view (LACV) dataset. All experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

4.1. Implementation Details

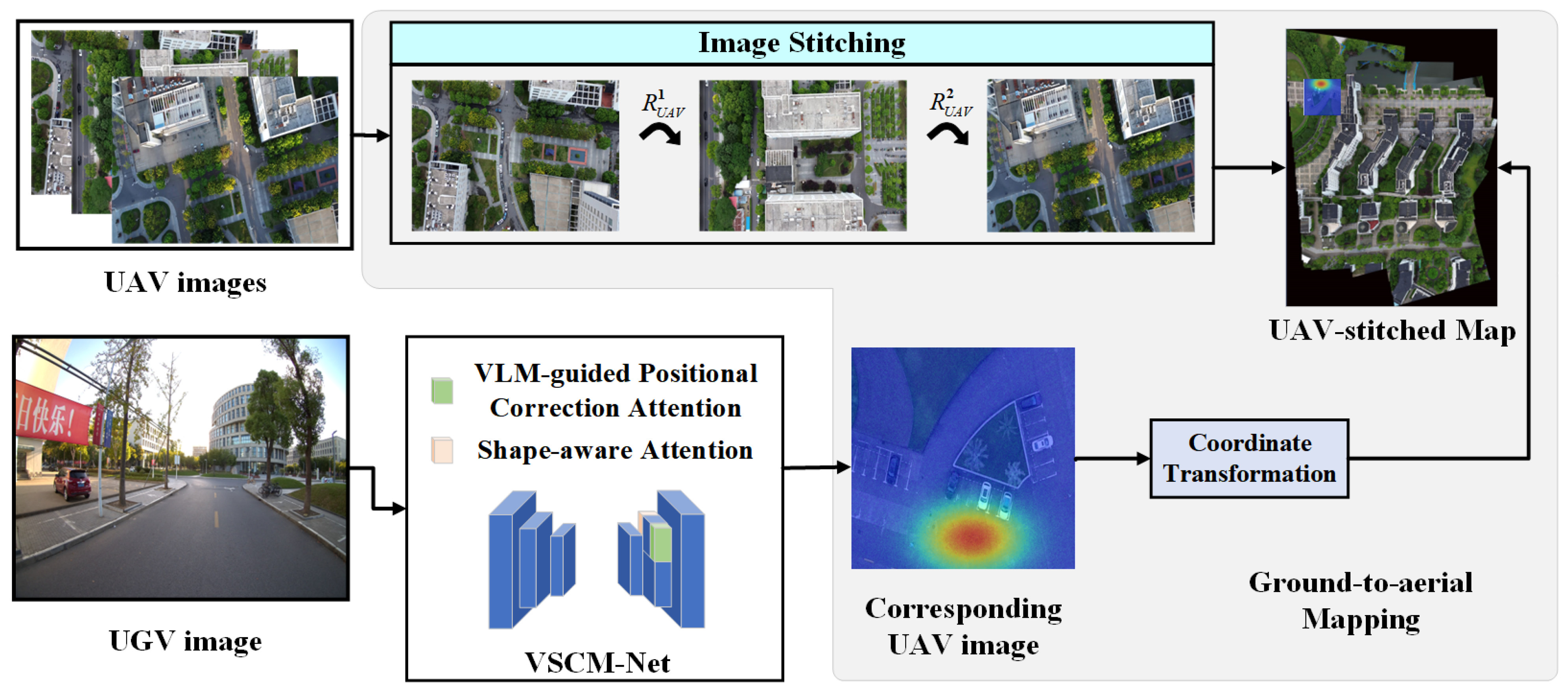

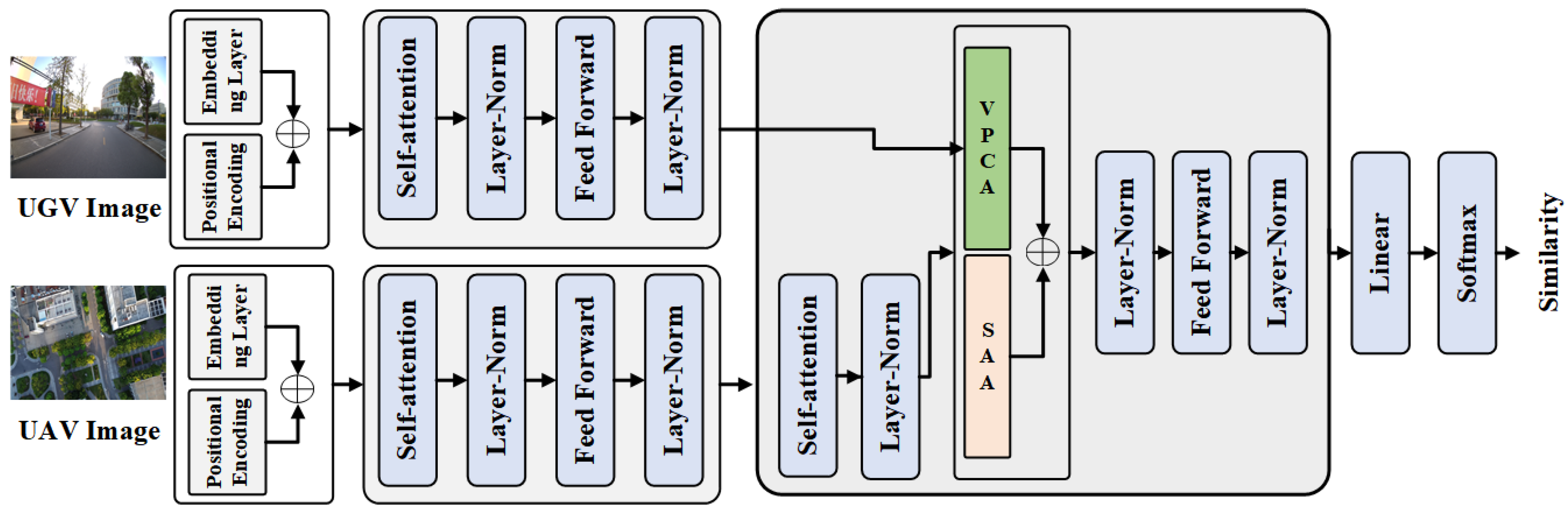

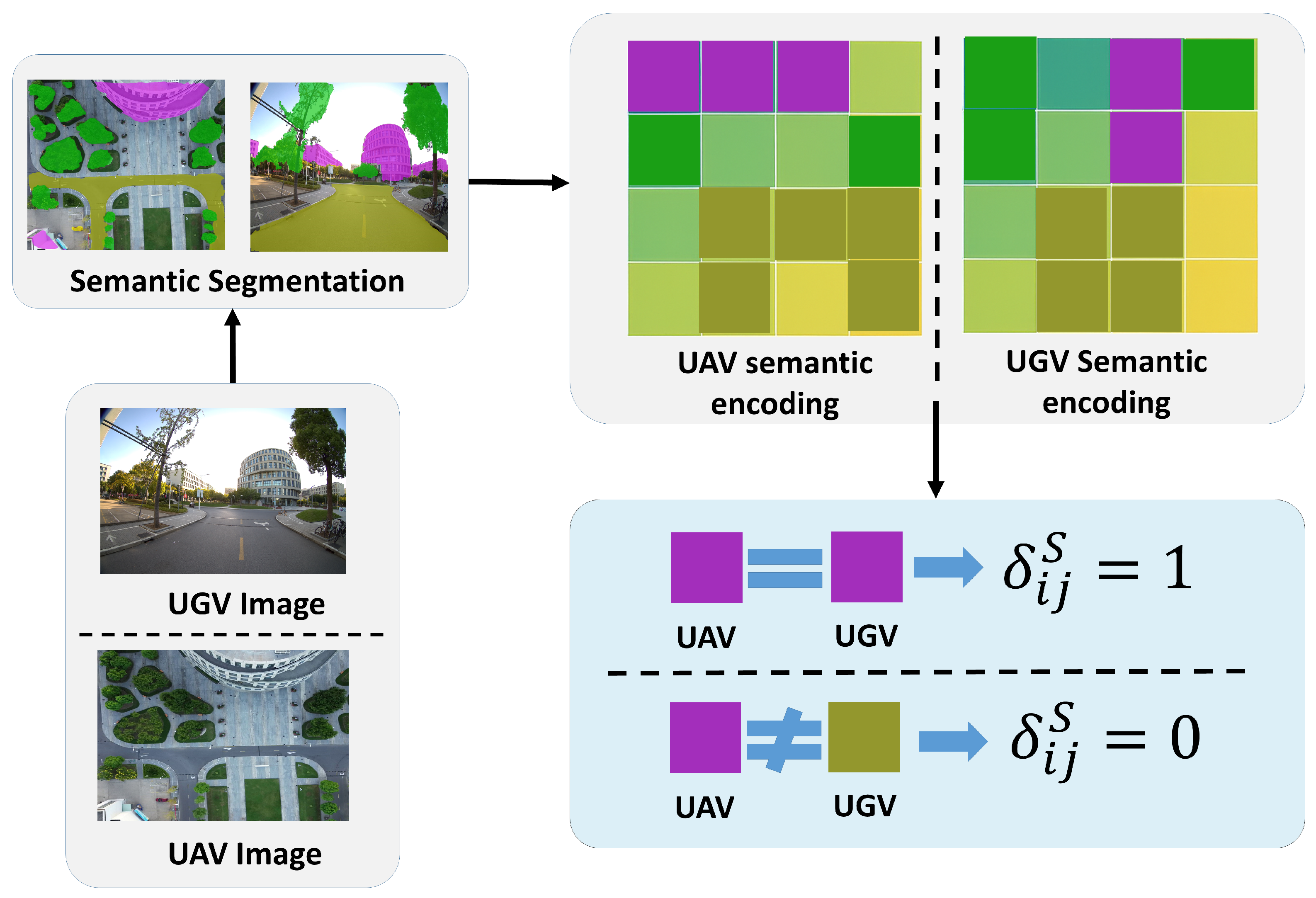

This section presents a detailed description of the training strategy employed for the proposed VSCM-Net, outlining the network configuration, optimization settings, and the two-stage learning paradigm designed to ensure stable and effective cross-view matching. In the first stage, the VSCM-Net equipped with a ConvNeXt-Base backbone is pretrained without the VPCA and SAA components. In the second stage, the full framework, incorporating both VPCA and SAA, is fine-tuned to capture geometry-corrected and shape-aware alignment cues. The Transformer layer adopts a 512-dimensional embedding space, an eight-head multi-head attention mechanism, and a 2048-dimensional feed-forward network. Additionally, 2D sinusoidal positional encoding with a dimensionality of 512 is applied to both the UAV and UGV tokens to preserve spatial structure within the Transformer. For both stages, training is performed for 100 epochs with a batch size of 16 using the AdamW optimizer. The initial learning rate is set to with a weight decay of . To stabilize early optimization, a linear warm-up is applied during the first of the training process, after which a cosine decay strategy is employed to gradually anneal the learning rate. Regularization is achieved through a dropout rate of within the Transformer layers.

4.4. Cross-View Matching Experiments

4.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

We first evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm on the cross-view similarity matching task.

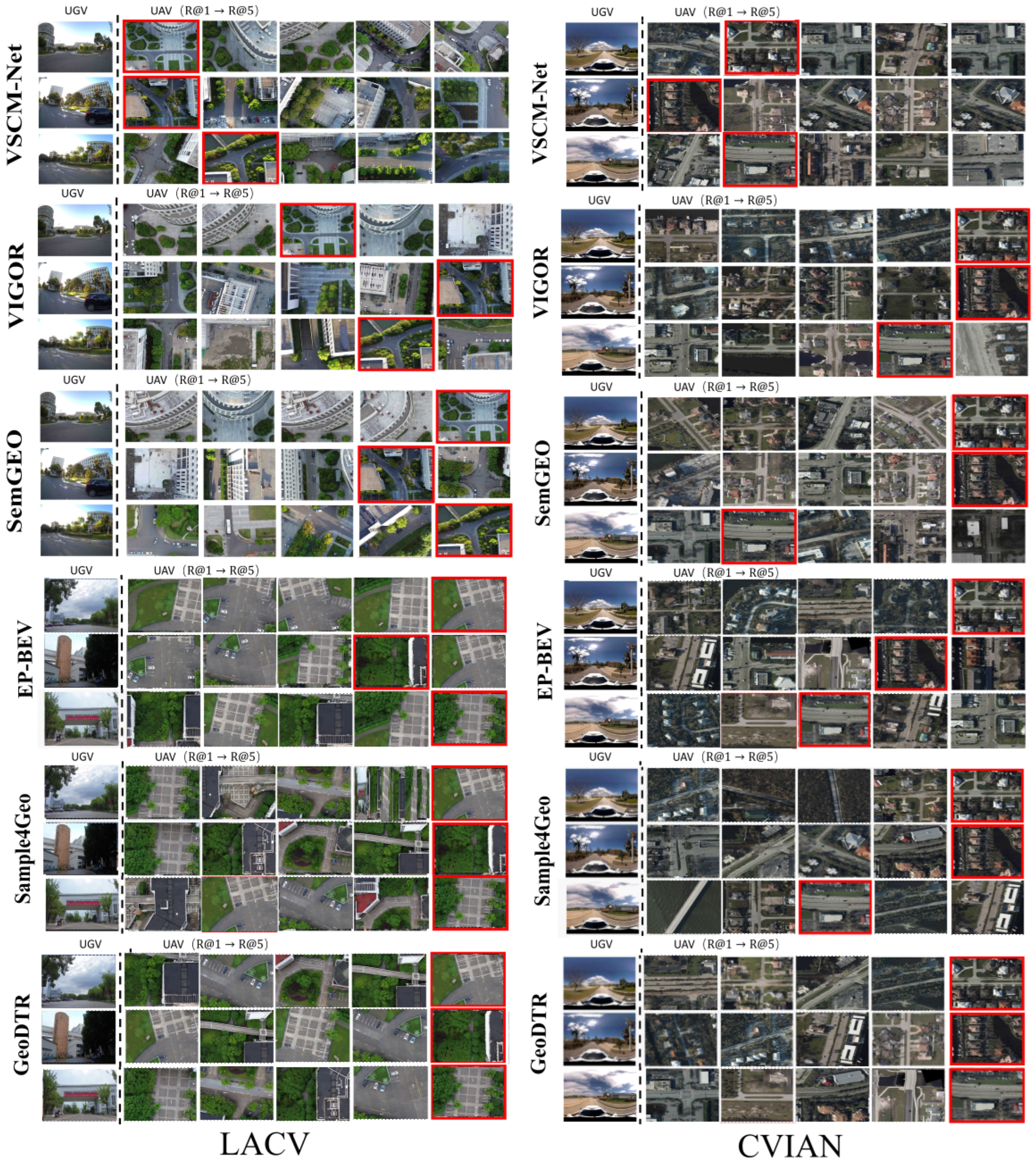

Figure 6 illustrates some typical similarity recognition results of the five methods on the two datasets. For each group, the left column shows the UGV query image, while the right column presents five UAV candidate images ranked from R@1 to R@5. The red bounding box highlights the first correct match, with its column position indicating the corresponding Top-K rank.

Across the qualitative evaluations on the LACV dataset, it’s obvious that the proposed VSCM-Net consistently achieves high Top-1 accuracy. Its advantage derives from the dual-branch architectures: The VLM-guided positional correction leverages semantic and spatial topology priors to enhance cross-view semantic alignment, while the shape-aware attention module explicitly captures the geometric relationships between aerial and ground perspectives. The synergy of these two components enables robust matching under severe viewpoint variations, repetitive structural patterns, and occlusions, allowing the network to consistently locate the correct UAV candidate image within the top two ranks. In contrast, SemGEO demonstrates partial effectiveness. Even though SemGEO utilizes semantic segmentation to improve localization in low-texture regions (e.g., open grounds, road boundaries, lawns), the method lacks joint modeling of spatial geometry across aerial and ground perspectives, relying primarily on semantic category consistency. As a result, it struggles with challenges such as cross-scale discrepancies, repetitive structures, and occlusions. For instance, in Rows 1, visually similar but spatially incorrect regions are mistakenly identified as matches, highlighting the limitations of its semantic generalization ability. VIGOR and EP-BEV shows weaker adaptability on the LACV dataset due to their sensitivity to occlusions, scale variations, and asymmetric urban layouts. As a consequence, they often confuse highly textured but irrelevant regions (e.g., building facades or parking lots) with the correct match.

On the CVIAN dataset, the evaluation reveals notable performance degradation across all five methods compared with their results on the LACV dataset. SemGEO exhibits a marked performance decline on the CVIAN dataset. This decline may be attributed to the low resolution of satellite imagery and the sparse distribution of recognizable semantic objects such as roads, which weakens the performance of SemGEO, which heavily relies on semantic information. Among all algorithms, VIGOR performs the worst, with only a few correct matches appearing within the Top-5. This weakness mainly arises from VIGOR’s reliance on feature-based coarse-to-fine retrieval under the assumption of local appearance consistency between the ground and aerial views.

4.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the Top-K Recall and AP results for five methods on the LSCV and CVIAN datasets separately. The results show that VSCM-Net consistently outperforms representative approaches VIGOR, SemGEO, Sample4Geo and EP-BEV in terms of R@1, validating the robustness and generalization of the proposed cross-view matching framework in diverse scales and semantic distributions.

On the LACV dataset, our method achieves the best performance across all three key metrics. In particular, the Top-1 recall reaches , markedly higher than GeoDTR , VIGOR , SemGEO (), Sample4Geo () and EP-BEV(), highlighting the model’s strong capability in producing highly accurate top-rank matches and ensuring robust localization reliability. The Top-5 recall attains , exceeding SemGEO by 12.61 percentage points and VIGOR by 34.77 percentage points, which indicates stable retrieval of the correct region within a compact candidate set. Furthermore, the AP of the proposed VSCM-Net reaches , substantially outperforming GeoDTR , VIGOR (), SemGEO (), Sample4Geo () and EP-BEV(), respectively, demonstrating that our approach yields more consistent and well-structured ranking distributions, thereby facilitating multi-candidate fusion and confidence-based decision-making.

Table 5 presents the comparative results on the CVIAN dataset. Overall, the proposed VSCM-Net achieves the best performance in R@1(

) and competitive results in both R@5(

) and AP(

), demonstrating its superior discriminative capability under challenging cross-view conditions. Compared with GeoDTR, VIGOR and SemGEO, our method yields a significant improvement of

,

and

in R@1, respectively, indicating more accurate top-ranked retrieval. With methods such as Sample4Geo and EP-BEV exhibiting higher R@5 values (

and

, respectively), their R@1 scores remain notably lower, suggesting that these models tend to retrieve the correct matches within the top-5 candidates but lack fine-grained discriminability for precise top-1 localization. In contrast, the proposed VSCM-Net achieves a more balanced trade-off between retrieval accuracy and ranking precision, reflecting its ability to maintain stable correspondence across significant viewpoint and appearance variations.

Compared with the LACV dataset, the performance degradation observed on CVIAN can be attributed to its fundamentally different sensing configuration. In the LACV dataset, UGV images are front-view observations captured using a standard pinhole camera, which provides an undistorted perspective aligned with a common robotic perception system. In contrast, the CVIAN dataset employs panoramic ground images acquired by a camera. These panoramic observations need to be projected into equirectangular representations during preprocessing, introducing strong nonlinear geometric distortions in object shapes, scales, and spatial boundaries. Such distortions produce image structures that differ substantially from those of perspective pinhole images and violate the spatial assumptions required by the VPCA and SAA modules. As a result, the geometry-aware corrections designed for undistorted front-view inputs become less effective when applied to these panoramic representations, leading to reduced matching accuracy.

Another potential cause of the performance drop lies in the disparity of aerial viewpoints. The proposed VSCM-Net is tailored for matching between low-altitude UAV imagery and ground-level UGV view, which share a higher degree of spatial overlap and structural correspondence. In contrast, the CVIAN dataset pairs ground-level panoramas with high-altitude satellite images whose extremely large field-of-view results in severe scale inconsistencies. Under such conditions, the UGV-visible area occupies only a small portion of the satellite image, making spatial layout correction highly challenging and further degrading registration performance.

It is important to note that these limitations reflect the characteristics of the CVIAN sensing setup rather than the generalizability of the proposed framework in real-world deployments. In practical disaster-response scenarios, up-to-date satellite imagery is rarely available due to sudden environmental changes, and panoramic ground cameras are not commonly used on rescue robots. Instead, low-altitude UAV scanning is typically employed to obtain real-time post-disaster aerial imagery, and most UGVs are equipped with standard pinhole RGB cameras due to their robustness and simplicity. The sensing configuration assumed by the proposed CVML framework, front-view UGV images paired with the low-altitude stitched-UAV map, therefore directly corresponds to practical field conditions and ensures strong applicability in real-world environments.

4.4.3. Ablation Experimental Results on VPCA and SAA Modules

To further investigate the impact of the proposed VPCA and SAA modules on cross-view matching performance, we conducted a series of ablation experiments on the LACV dataset. Specifically, we first adopt the network without VPCA or SAA biases as the baseline. On this basis, we then introduce VPCA and SAA attention modules individually, followed by their joint integration, which corresponds to the proposed VSCM-Net. All experiments are conducted on the LACV dataset, with Top-1 recall, Top-5 recall, and AP employed as the primary evaluation metrics. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 6.

The baseline network achieves R@1, R@5, and AP of , , and , respectively, demonstrating limited matching capability and indicating that relying solely on appearance texture features is insufficient for stable and accurate matching in complex cross-view scenarios. When the VPCA module is integrated into the baseline network, the R@1, R@5, and AP increase to , , and , respectively. This clearly demonstrates that the proposed VPCA module effectively compensates for the limitations of the Transformer in modeling spatial consistency under significant cross-view variations.

The performance also improves when the SAA module is incorporated into the baseline network. Specifically, the associated R@1, r@5, and AP reach , , and , respectively, indicating that the shape-aware attention module positively contributes to cross-view matching performance.

Finally, when both VPCA and SAA are integrated, i.e., in the proposed VSCM-Net, the model achieves the best results across all three metrics, with R@1 of , R@5 of , and AP of . These results confirm the complementary roles of the two modules: VPCA facilitates global geometric layout modeling, while SAA enhances local structural alignment, and their joint effect leads to significant improvements in matching accuracy and robustness under complex cross-view conditions. Overall, the ablation study provides clear evidence of the critical contribution of our design. Compared with the baseline Transformer, the complete model achieves a remarkable improvement of percentage points in Top-1 recall, demonstrating that incorporating spatial topology modeling and shape-aware attention substantially enhances cross-view matching accuracy, ranking stability, and generalization capability, thereby providing solid technical support and design insights for real-world applications.

4.4.4. Ablation Experimental Results on Depth Estimation Noises

In this section, we analyze how depth estimation errors propagate to the pseudo-UAV projection in the VPCA module and influence the UAG-UGV cross-view matching accuracy. In the LACV dataset, we inject zero-mean Gaussian noise with standard deviations of

,

, and

into the outputs of the depth estimation network

. The experimental results, summarized in

Table 7, show that the proposed VSCM-Net remains stable under low and moderate noise conditions. With

, the impact is negligible, and R@1 decreases only slightly from

to

. When

, R@1 declines to

, demonstrating that the proposed VPCA and SAA modules can effectively compensate for moderate depth-induced spatial deviations. However, at

, the pseudo-UAV projection becomes substantially distorted, causing R@1 to drop to

. These results indicate that the proposed modules exhibit strong robustness to realistic depth uncertainties, and significant performance degradation occurs only under extreme noise levels that are unlikely to arise in practice.

4.4.5. Ablation Experiments on Semantic Segmentation Noises

To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed VSCM-Net framework against uncertainties in semantic segmentation in the VPCA and SAA modules, we conduct an ablation study by perturbing the predicted semantic masks. Specifically, we introduce controlled segmentation noise by applying morphological dilation to the semantic masks using structuring elements of increasing size. The dilation kernel size

K serves as the noise level, where large kernels expand semantic boundaries more aggressively and thus simulate stronger boundary ambiguity and segmentation errors. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 8.

The results indicate that VSCM-Net remains stable under mild and moderate segmentation noise (), with only a slight degration in matching performance. This demonstrates that the proposed VPCA and SAA modules can effectively tolerate boundary-level inconsistencies in the semantic masks. However, when the dilation kernel is increased to , the masks become substantially distorted, merging or oversmoothing adjacent semantic regions. This serves to perturbation leads to a more noticeable performance drop, suggesting that cross-view matching begins to deteriorate when semantic structures deviate significantly from their true topology. Overall, the results confirm that the proposed VSCM-Net exhibits strong robustness to realistic semantic segmentation noise while revealing the limits under extreme perturbations.

4.4.6. Ablation Experiments on BLIP-2 in VPCA Module

In this section, we quantify the contribution of the VLM-guided spatial relationship correction module in the VPCA by conducting an ablation study comparing VSCM-Net with and without the BLIP-2 module on the LACV dataset. As shown in

Table 9, removing BLIP-2 leads to substantial performance degradation; the R@1 score drops from

to

, which shows a reduction of

. Additionally, the R@5 and AP exhibit similar declines. This phenomenon can be attributed to the limitations of pseudo-UAV images generated from the UGV viewpoint, which relay on depth estimation. In real-world environments, depth predictions are susceptible to discontinuities near object boundaries, often resulting in distorted relative positions and misaligned or deformed semantic regions in the pseudo-UAV projection. The VLM-guided spatial correction module incorporates high-level relationship priors derived from language-based semantic reasoning, enabling the model to infer plausible spatial locations. These findings underscore that VLM-derived relational information is not merely auxiliary but constitutes an essential component for achieving robust and semantically consistent cross-view matching in complex environments.

4.4.7. Ablation Experiments on Illumination

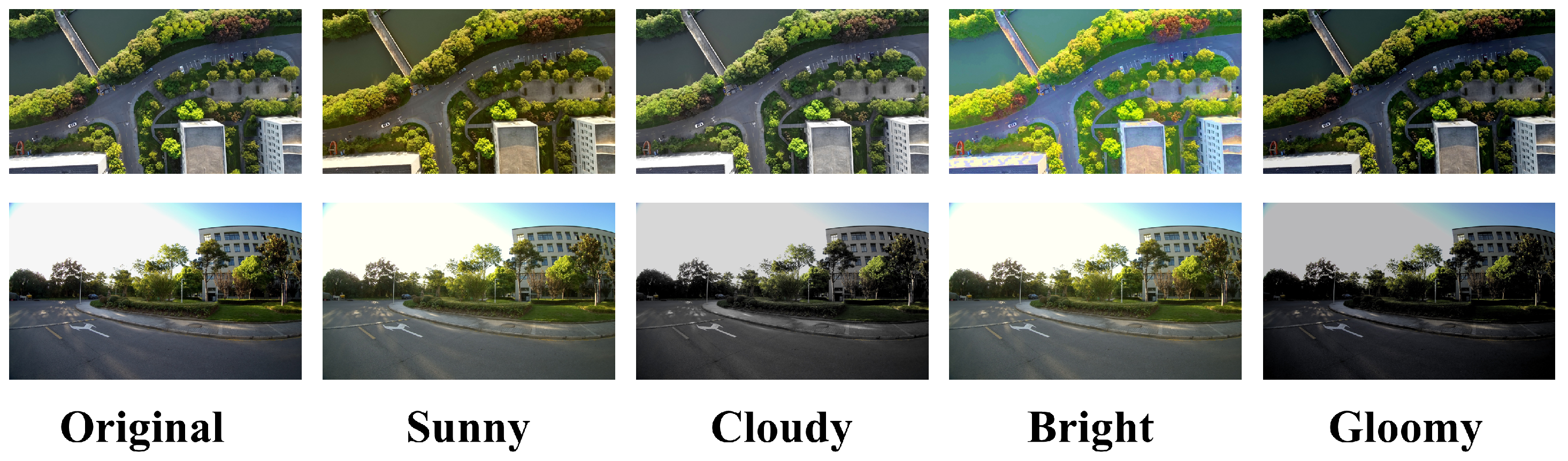

Seasonal changes in outdoor environments typically introduce significant variations in illumination, atmospheric conditions, and appearance characteristics. To systematically evaluate the robustness of the proposed framework under different seasonal conditions, we simulate diverse appearance variations on the LACV dataset through controlled photometric augmentation. Although the LACV dataset does not contain multi-season real-world captures, season-like variations can be approximated using image-level transformations that alter contrast and global brightness. As shown in

Figure 7, four representative scene conditions are generated, including sunny, cloudy, bright, and gloomy, corresponding, respectively, to high-saturation summer scenes, low-contrast overcast conditions, high-luminance morning scenes, and low-light winter-like environments. The augmented datasets are than used for evaluation of the proposed method.

As shown in

Table 10, the experimental results indicate that the proposed framework maintains strong localization performance under moderate illumination shifts. The sunny and cloudy conditions produce only minor decreases in R@1, R@5, and AP. In both cases, the illumination change does not substantially modify the structural edges or semantic boundaries of the scene. The dominant geometric features are largely preserved, enabling the network to extract consistent spatial cues. Therefore, semantic recognition and geometric structure estimation are not adversely affected, and the overall localization accuracy remained nearly unchanged. Performance degradation becomes more pronounced in the Bright condition, where excessive luminance reduces edge saliency and suppresses semantic segmentation cues. The diminished contrast also weakens the extraction of geometric structures, which together result in a noticeable drop in localization accuracy. The gloomy condition yields the largest performance reduction across all metrics, primarily due to substantial loss of texture, reduced semantic discriminability, and diminished contrast between built structures and surrounding terrain. Overall, this study demonstrates that the proposed VSCM-Net exhibits strong resilience under a wide range of illumination variations, while highlighting the challenges posed by extreme low-light conditions.

4.5. Cross-View Localization in Real-World Experiments

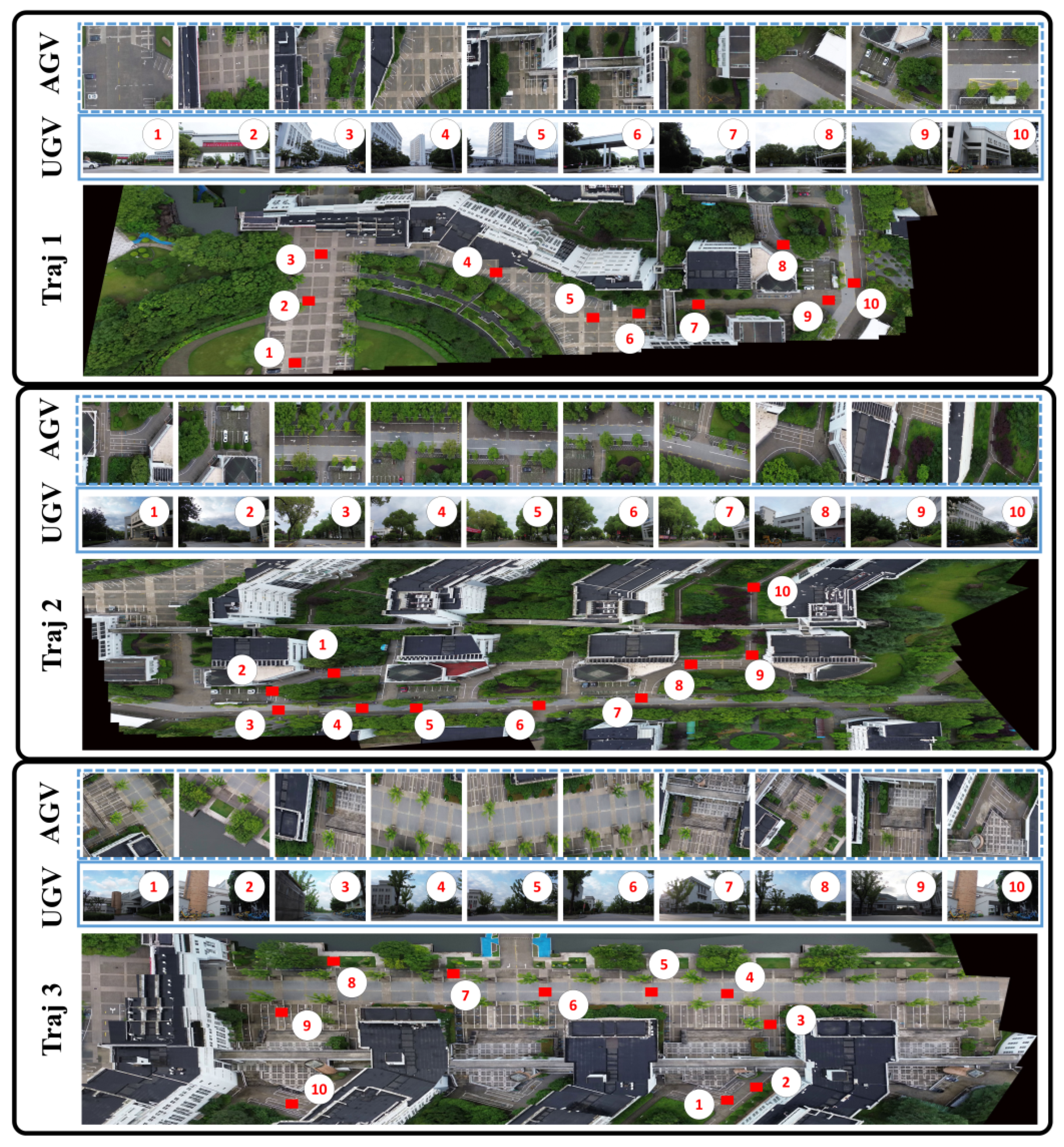

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed CVML framework, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of global localization accuracy using three representative trajectories (Traj 1, Traj 2, and Traj 3) from the LACV dataset. The evaluation includes two complementary components. First, for each trajectory, ten representative target points (a1–a10) with distinct scene characteristics—such as road intersections, turning points, and regions with significant viewpoint variation—were selected to assess the ground-truth localization error at these positions. Second, we analyzed the localization accuracy throughout the entire motion sequence of each trajectory. Note that the reported localization error in the proposed CVML framework combines both matching and stitching effects. In our experiments, visual checks of seam alignment and trajectory overlay did not reveal apparent stitching artifacts, suggesting that the majority of the error is induced by the matching component.

4.5.1. Landmark Point Localization Experiment and Analysis

Figure 8 illustrates the ground-truth positions of the testing landmark points on the stitched global map, together with their corresponding UGV and UAV image pairs. The selected landmarks encompass diverse geographic scenes, including open areas, narrow passages, branch intersections, main roads, and greenbelts. Such diversity enables a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed algorithm’s robustness and stability across various environmental conditions. The corresponding landmark point localization errors are summarized in

Table 11.

It can be observed that CVML consistently achieves the lowest localization error across all landmark points of the evaluated trajectories, with average errors of 4.8 m, 8.6 m, and 12.4 m in the three scenarios, respectively. In contrast, VIGOR reports errors of 28.4 m, 25.9 m, and 29.3 m, indicating that CVML improves localization accuracy by , , and , respectively.

Taking Traj 1 as an example, its ten landmarks can be grouped into four representative scene types: open areas (a1–a2), shape-transition segments covering straight-to-curve transitions and urban facades (a3–a5), occluded passages (a6–a7), and complex intersections involving multiple turns (a8–a10). The segmented statistics reveal that CVML achieves an average error of m in open areas (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO), m in shape-transition segments (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO), m in occluded passages (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO), and m at complex intersections (vs. m for VIGOR and m for SemGEO).

These results clearly demonstrate that, regardless of continuous shape variation, severe occlusion, or complex intersection topology, the proposed CVML framework maintains low mean errors with reduced variance, underscoring its robustness and stability across diverse environments.

4.5.2. Trajectory Following Experiment and Analysis

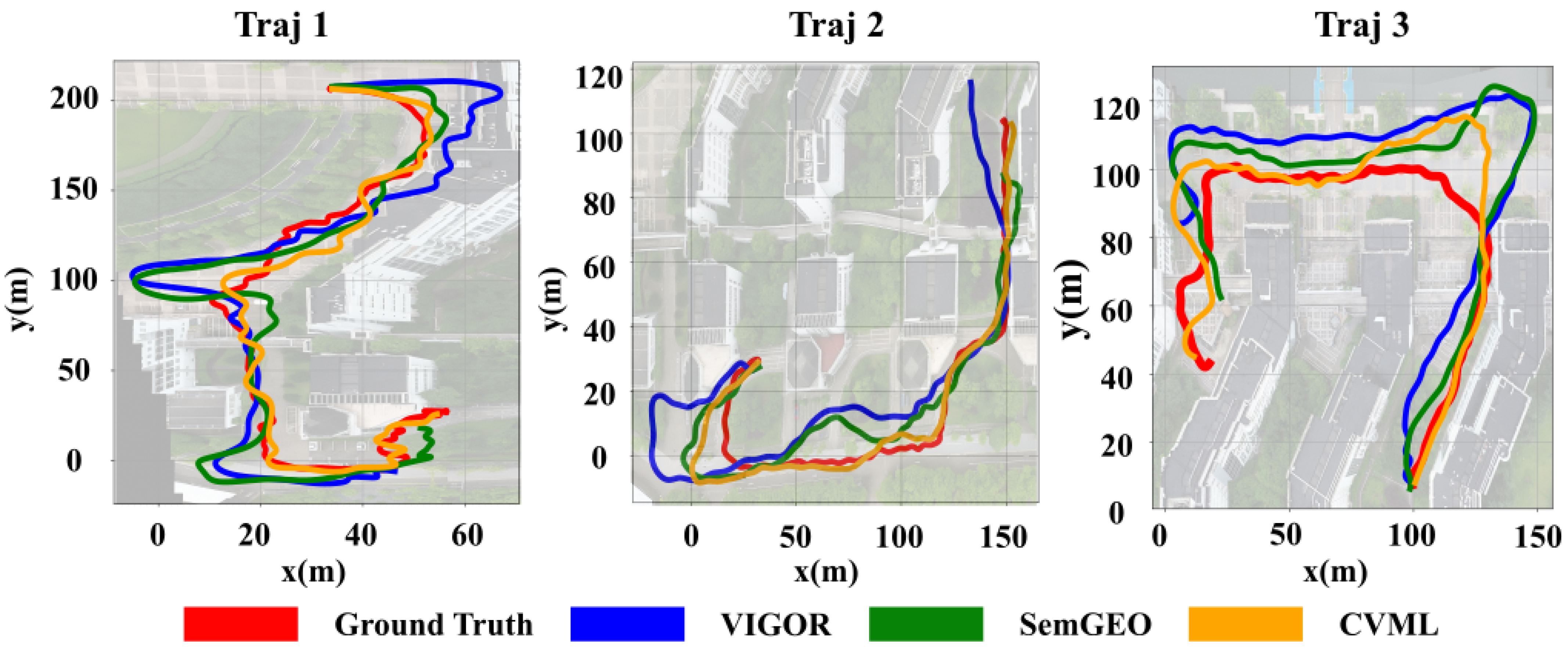

Beyond the analysis of individual landmark points, we further carried out a comprehensive evaluation on the trajectory following performance of the proposed method. The full-trajectory following experiments not only provide an overall assessment of error distribution and stability during continuous motion but also demonstrate the practical applicability and deployment potential of the proposed framework in real-world scenarios.

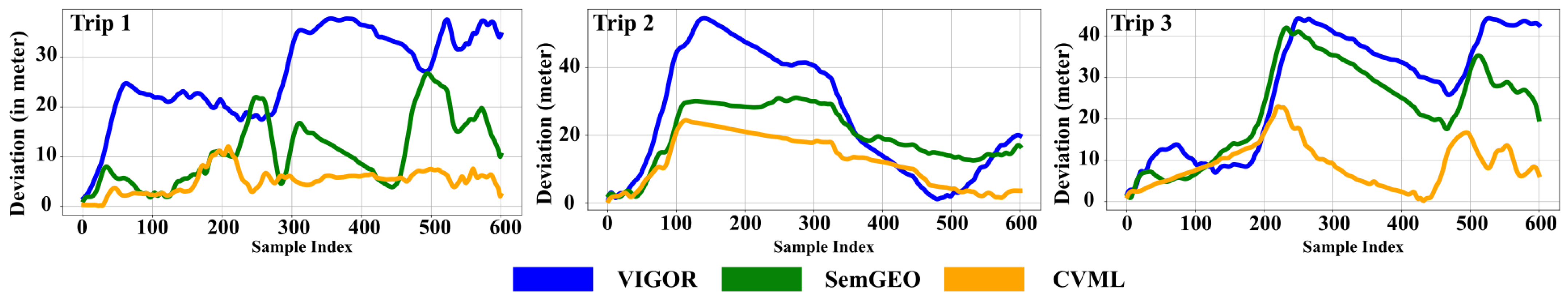

Figure 9 illustrates the comparison between the ground truth and the trajectories generated by VIGOR, SemGEO, and the proposed CVML, separately. The associated error distribution relative to the ground truth of each algorithm is shown in

Figure 10. Overall, the trajectories generated by the proposed CVML align most closely with the ground truth, followed by SemGEO, while VIGOR exhibits the largest deviations. The most significant discrepancies are usually observed at turning regions, as shown in Traj 1 and Traj 3. The turning regions typically correspond to complex environments containing buildings, roads, trees, and other structures. Moreover, the UGV’s limited field of view may result in incomplete visual information, which degrades the matching performance of compared algorithms. This limitation is particularly detrimental to VIGOR, as its framework relies heavily on panoramic street-view imagery for accurate matching.

Table 12 summarizes the trajectory localization errors of the three methods, and the proposed CVML consistently achieves the lowest average localization error across all trajectories, reducing the error by up to

compared with VIGOR and by more than

compared with SemGEO. Additionally, the proposed CVML exhibits the smallest standard deviation in all trajectories as well, indicating superior robustness and stability.

Tanking Traj 3 as an example, the path includes two turns along the route. In the main road segment between two buildings (the lower-right part of the Traj 3), all algorithms achieve satisfactory matching and localization performance. This may be attributed to the relatively simple road structure in this segment, where the salient feature on the road’s sides are well-defined and can be effectively observed from the aerial viewport. However, a noticeable offset occurs for all three methods at the first turn. The proposed CVML promptly corrects its trajectory and converges back to the ground-truth path, whereas both VIGOR and SemGEO exhibit substantial errors in this region. For VIGOR and SemGEO, these deviations likely stem from their insufficient modeling of topological dependencies among complex semantic objects in UGV images captured at the turn, which hinders effective matching with the UAV image.

The intended use of the proposed CVML framework is GNSS-denied emergency response, where satellite imagery is often outdated, and ground conditions may have changed. In such scenarios, UAVs can generate a fresh stitched map, and localizing the UGV on this map supports rapid reconnaissance, route planning, and search tasks. Typical urban roads are 4–6 m wide, and our best results are sufficient for navigation and turning at road-scale resolutions.