An Efficient and Accurate UAV State Estimation Method with Multi-LiDAR–IMU–Camera Fusion

Highlights

- The proposed DLIC method reformulates the complex, coupled UAV state estimation problem in multi-LiDAR–IMU–camera systems as an efficient distributed subsystem optimization framework. The designed feedback mechanism effectively constrains and optimizes the UAV state using the estimated subsystem states.

- Extensive experiments demonstrate that DLIC achieves superior accuracy and efficiency on a resource-constrained embedded UAV platform equipped with only an 8-core CPU. It operates in real time while maintaining low memory usage.

- This work demonstrates that the challenging, coupled UAV state estimation problem in multi-LiDAR–IMU–camera systems can be effectively addressed through distributed optimization techniques, paving the way for scalable and efficient estimation frameworks.

- The proposed DLIC method offers a promising solution for real-time state estimation in resource-limited UAVs with multi-sensor configurations.

Abstract

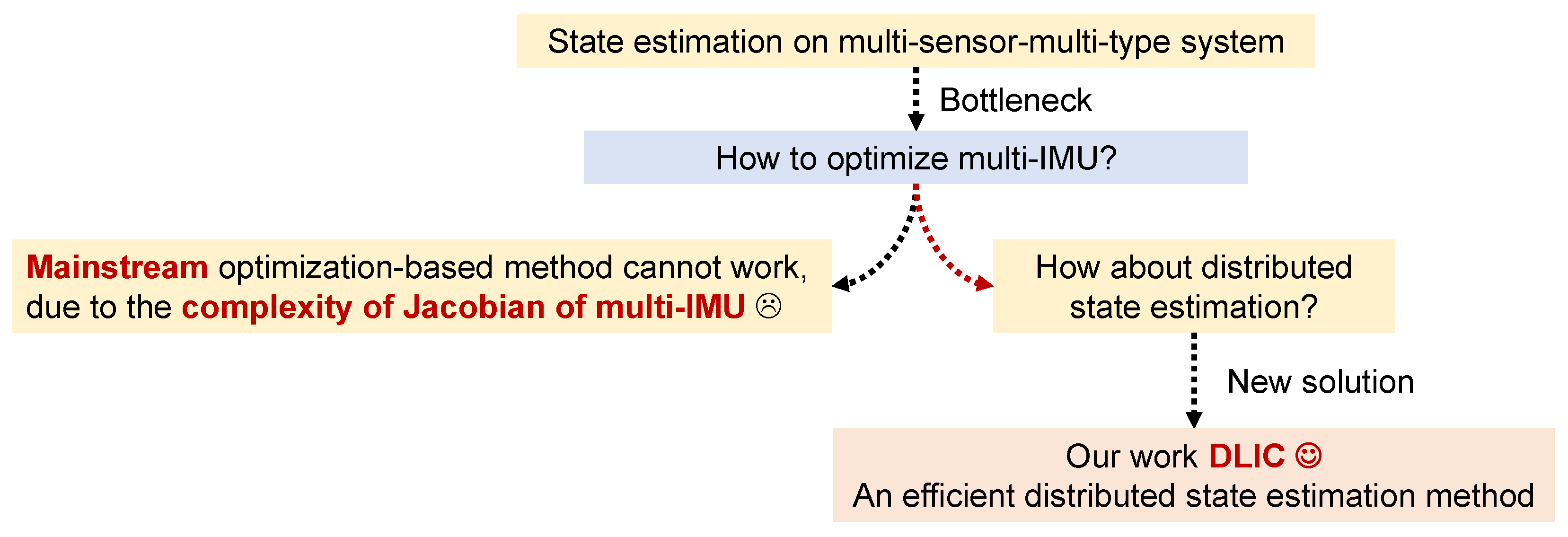

1. Introduction

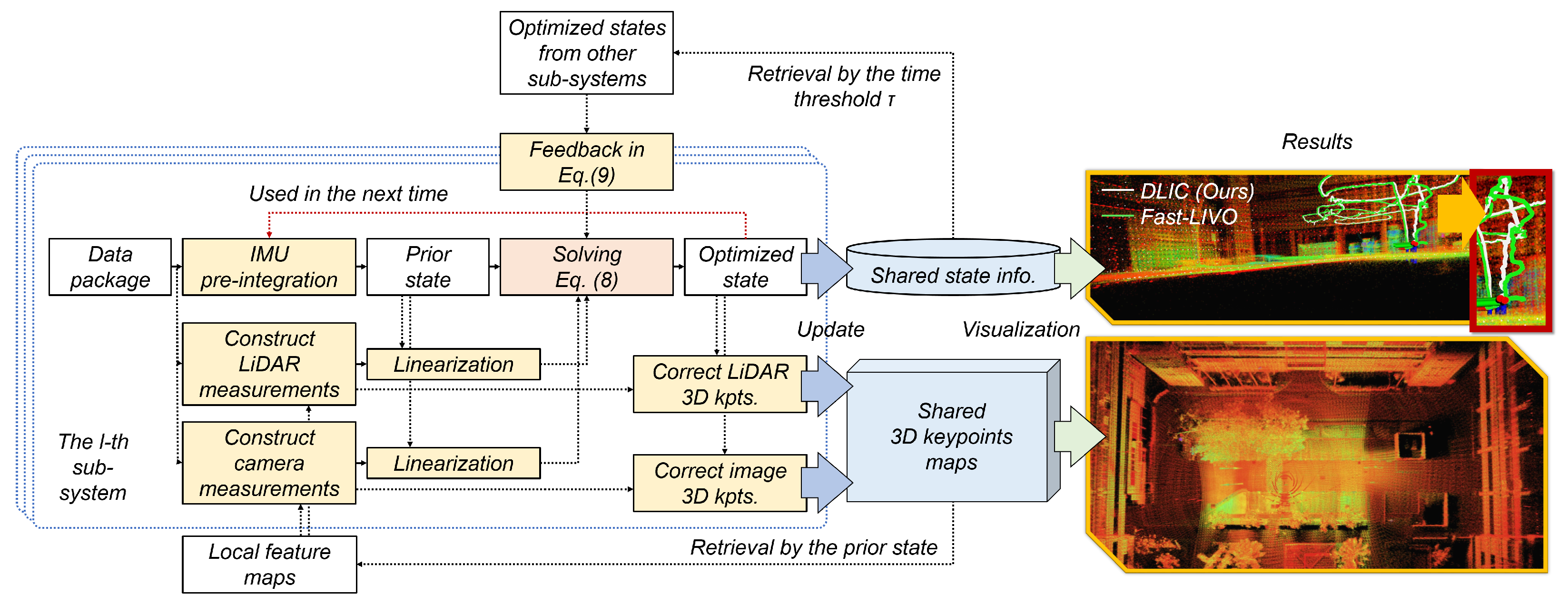

- We propose an efficient and accurate distributed state estimation method, DLIC, which fuses data from multiple LiDARs, IMUs, and cameras to achieve accurate UAV state estimation.

- DLIC decomposes the complex, coupled multi-LiDAR–IMU–camera system into a series of single LiDAR–IMU–camera subsystems. A feedback function is then derived to effectively constrain and optimize the global UAV state based on the estimated subsystem states.

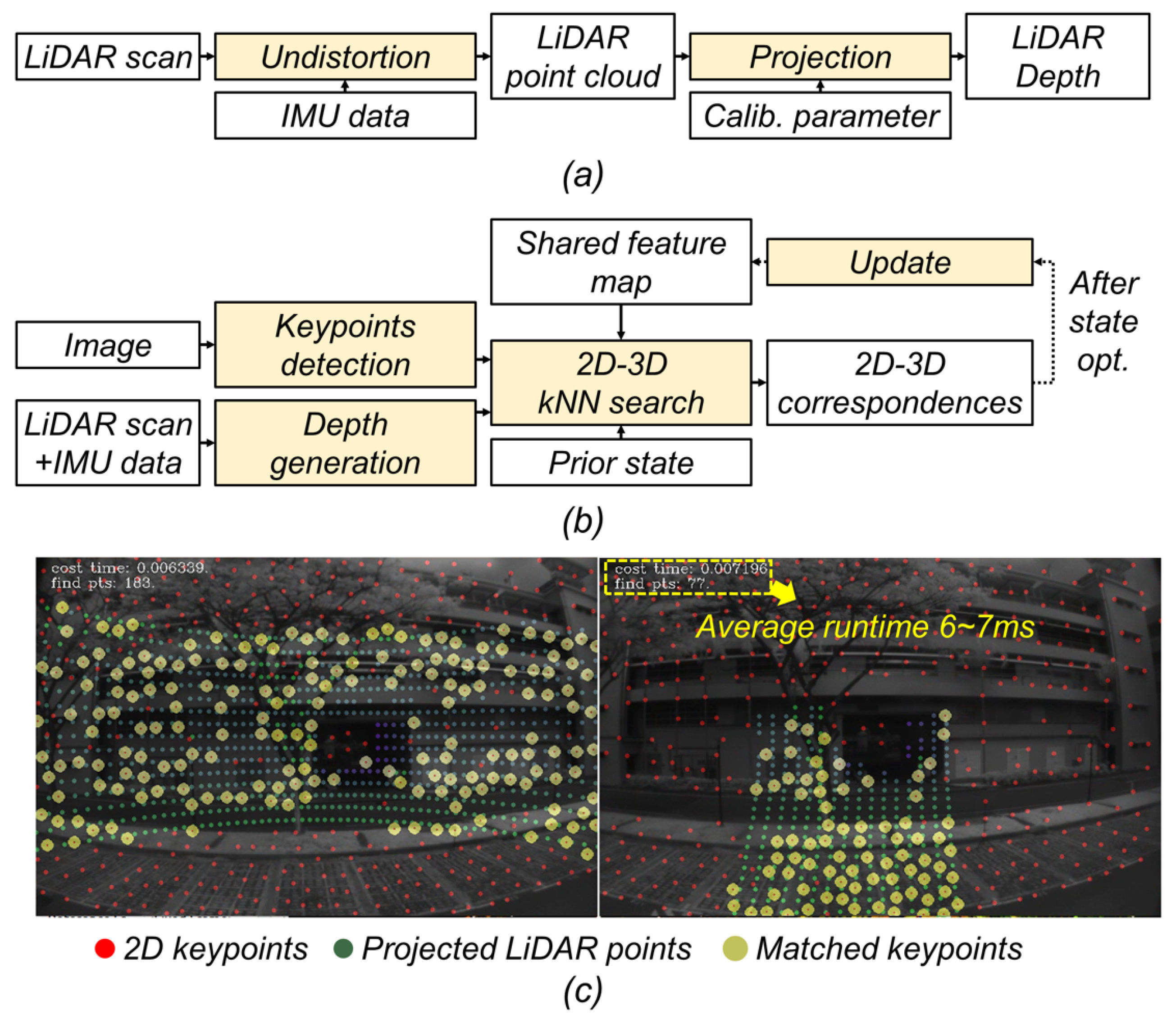

- To further accelerate state estimation, we develop an efficient I2P module that establishes high-quality 2D–3D correspondences and constructs reliable visual measurements efficiently.

2. Related Works

2.1. Single-Sensor-Multi-Type Case

2.2. Multi-Sensor-Single-Type and Multi-Sensor-Multi-Type Case

2.3. Discussions

3. Problem Statement

3.1. Basic State Estimation Model

3.2. Challenge in Multi-Sensor-Multi-Type Case

4. Proposed Method DLIC

4.1. Efficient Distributed State Estimation Model

4.2. Feedback Function in Distributed State Estimation

4.3. Distributed State Estimation in a Multi-LiDAR–IMU–Camera System

4.4. Assisted Image-to-Point-Cloud Registration

5. Experiments and Discussions

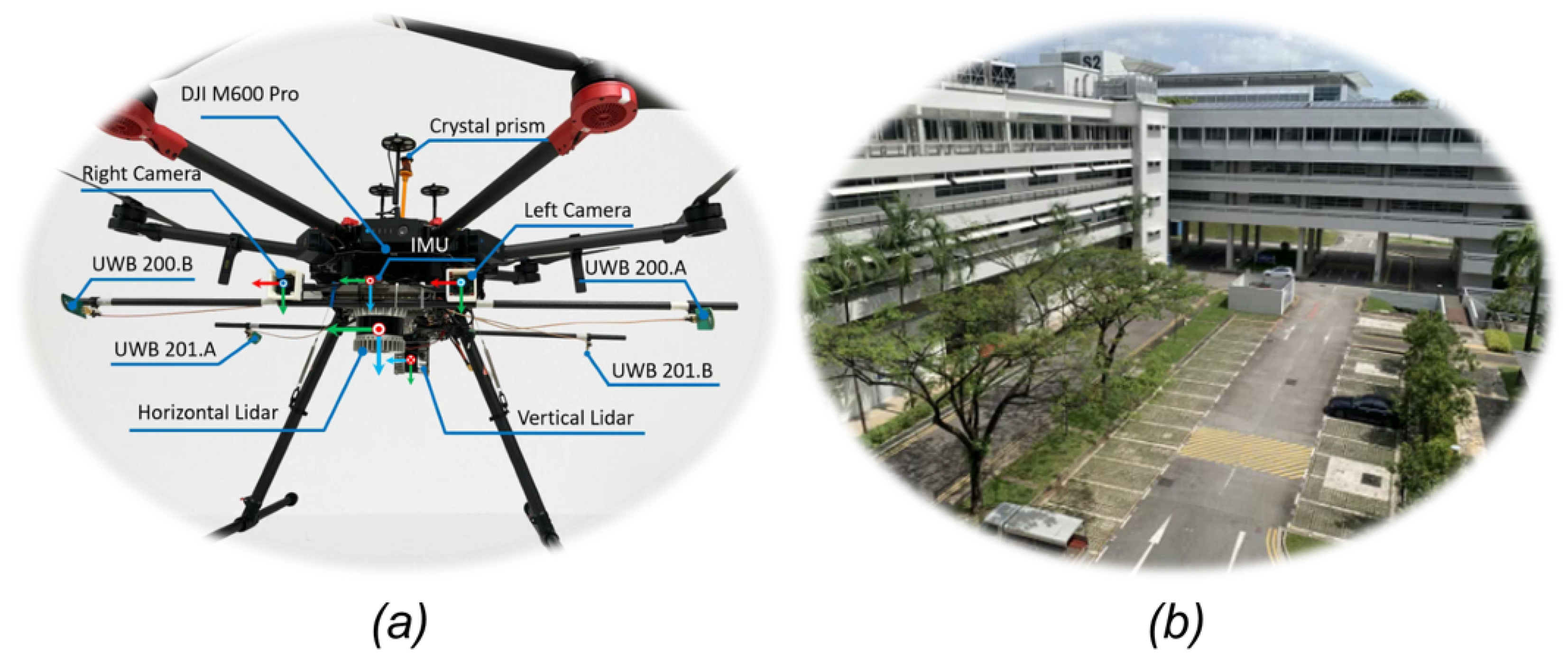

5.1. Dataset Configuration

5.2. Comparison Results

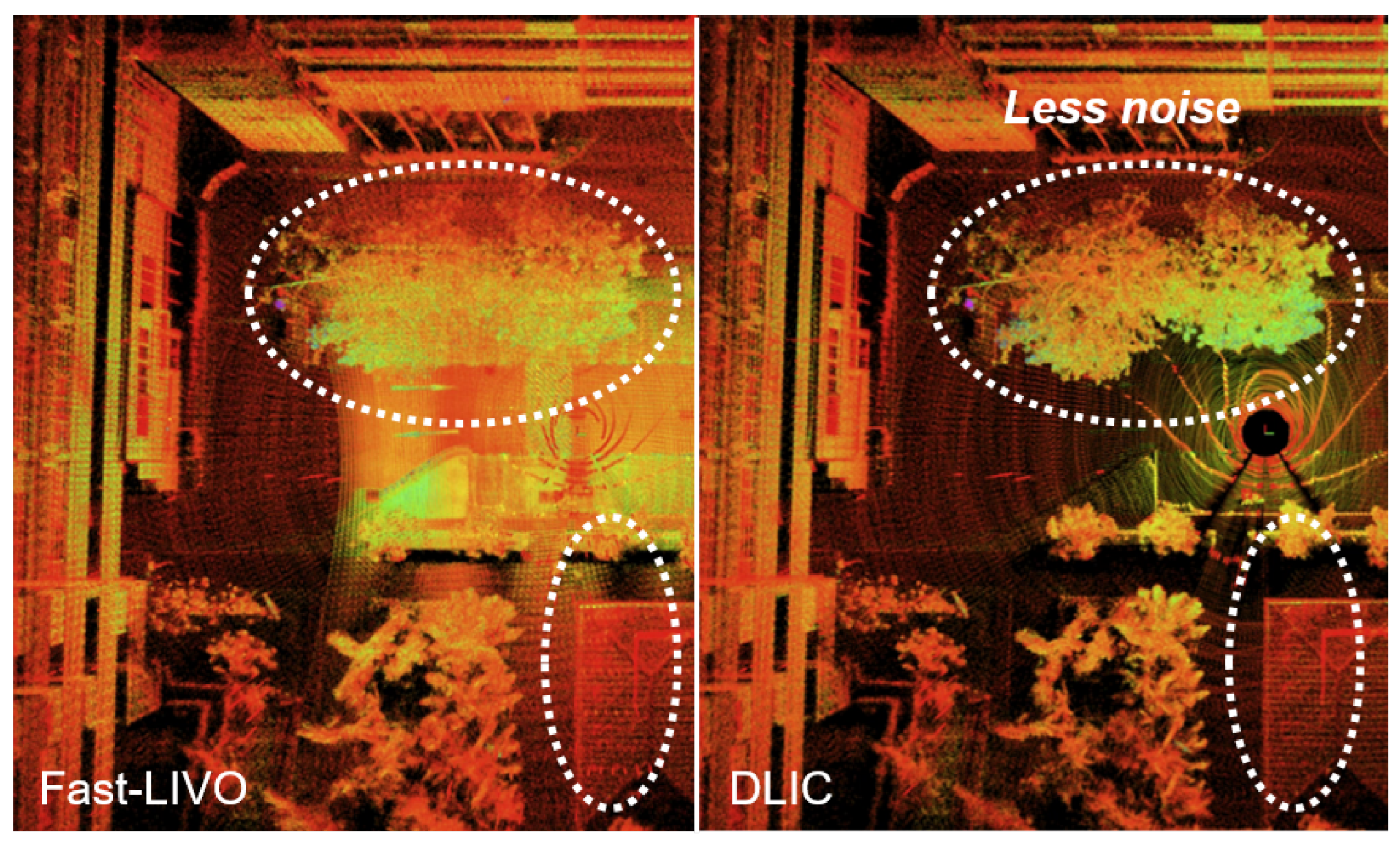

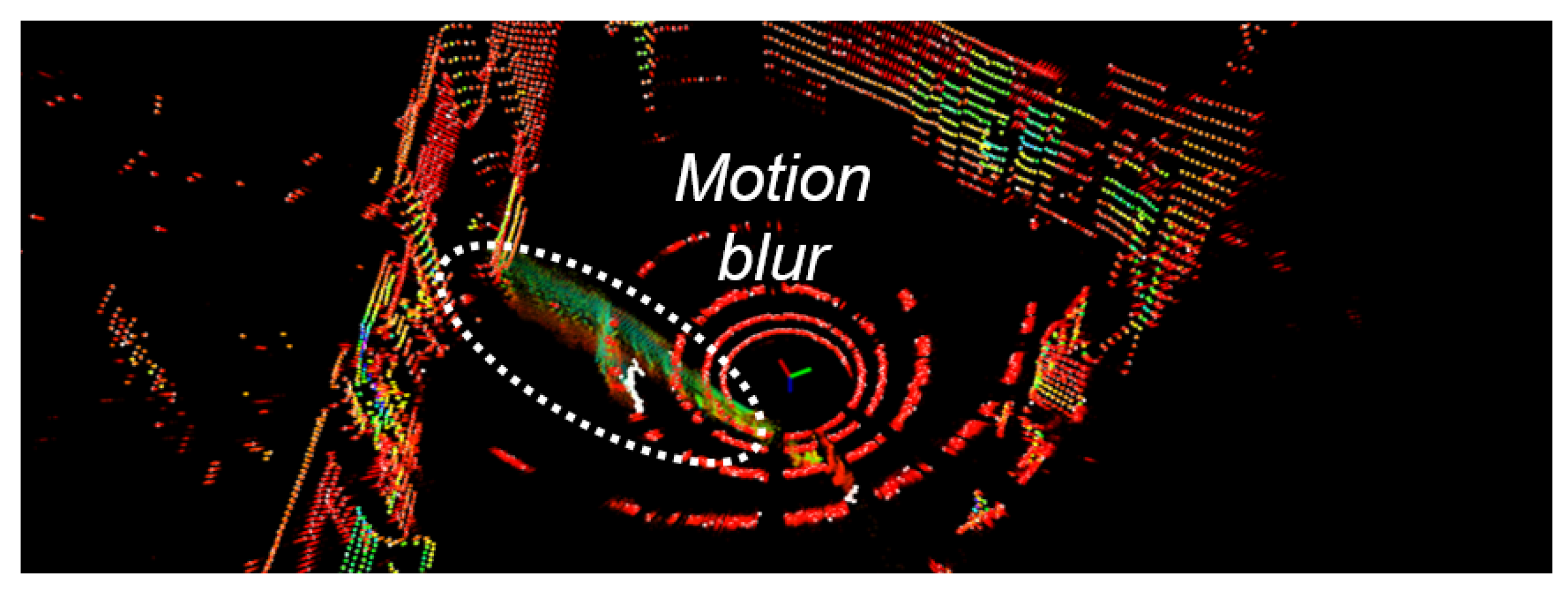

5.3. Visualization Verifications

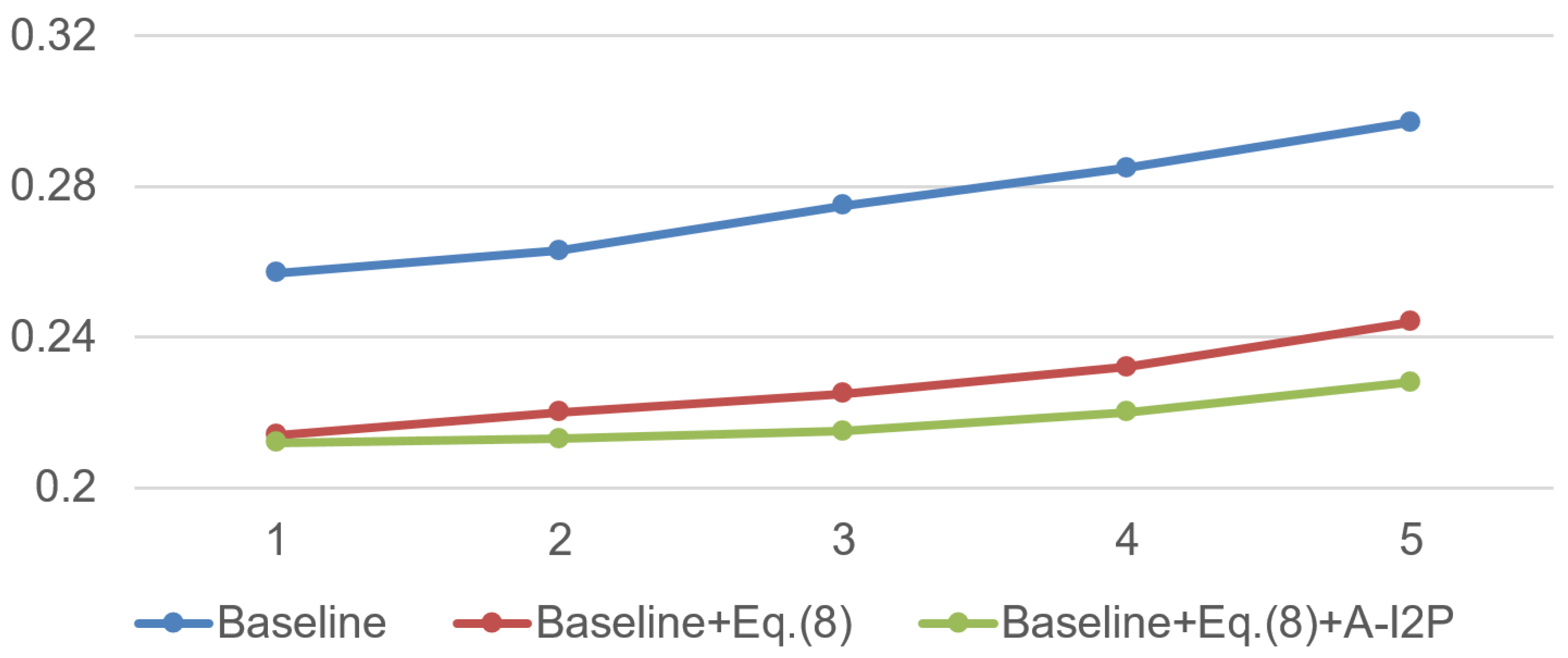

5.4. Ablation Studies

5.5. Limitations and Future Works

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| FoV | Field of view |

| RGB | Red, green, blue |

| LiDAR | Light detection and ranging |

| IMU | Inertial measurement unit |

| CPU | Central processing unit |

| I2P | Image-to-point cloud |

| LIVO | LiDAR-inertial-visual odometry |

| LIO | LiDAR-inertial odometry |

| ESIKF | Error state iterative Kalman filter |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SSE | Sum of squared errors |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| SLAM | Simultaneous localization and mapping |

| UWB | Ultra wide band |

| GT | Ground truth |

| kNN | k-nearest neighbor |

| MAP | Maximum a posterior |

| EKF | Extended Kalman filter |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

Appendix A. Further Discussion of DLIC

References

- Cui, J.; Niu, J.; He, Y.; Liu, D.; Ouyang, Z. ACLC: Automatic Calibration for Nonrepetitive Scanning LiDAR-Camera System Based on Point Cloud Noise Optimization. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5001614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Ou, C.; Yan, D.; Zhang, H.; Xue, X. Open-Vocabulary Object Detection in UAV Imagery: A Review and Future Perspectives. Drones 2025, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhang, B.; Duan, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, C. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Formation Control and Safety Guarantee; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Bu, S.; Li, J.; Xia, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Distributed Relative Pose Estimation for Multi-UAV Systems Based on Inertial Navigation and Data Link Fusion. Drones 2025, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Lang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, X. Continuous-Time Fixed-Lag Smoothing for LiDAR-Inertial-Camera SLAM. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2023, 28, 2259–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, F. FAST-LIVO: Fast and Tightly-coupled Sparse-Direct LiDAR-Inertial-Visual Odometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 4003–4009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yu, B.; Jiang, C.; Hua, C.; Fu, X.; Kuang, X. IGE-LIO: Intensity Gradient Enhanced Tightly Coupled LiDAR-Inertial Odometry. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 8506411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wen, C.; Prakhya, S.M.; Yin, H.; Zhou, R.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Bai, H.; Wang, Y. Multimodal Features and Accurate Place Recognition with Robust Optimization for Lidar-Visual-Inertial SLAM. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5033916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zheng, C.; Xu, W.; Zhang, F. R2LIVE: A Robust, Real-Time, LiDAR-Inertial-Visual Tightly-Coupled State Estimator and Mapping. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 7469–7476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, F. R3LIVE: A Robust, Real-time, RGB-colored, LiDAR-Inertial-Visual tightly-coupled state Estimation and mapping package. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 10672–10678. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.; Ye, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M. Robust Odometry and Mapping for Multi-LiDAR Systems with Online Extrinsic Calibration. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Lou, Y.; Huang, F.; Tu, Z.; Zhang, S. Simultaneous Localization of Rail Vehicles and Mapping of Environment with Multiple LiDARs. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 8186–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F. A decentralized framework for simultaneous calibration, localization and mapping with multiple LiDARs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021; pp. 4870–4877. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Duberg, D.; Jensfelt, P.; Yuan, S.; Xie, L. SLICT: Multi-Input Multi-Scale Surfel-Based Lidar-Inertial Continuous-Time Odometry and Mapping. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2102–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Yuan, S.; Cao, M.; Lyu, Y.; Nguyen, T.H.; Xie, L. MILIOM: Tightly Coupled Multi-Input Lidar-Inertia Odometry and Mapping. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5573–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, Y. D-LIOM: Tightly-Coupled Direct LiDAR-Inertial Odometry and Mapping. IEEE Trans. Multim. 2023, 25, 3905–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Jung, S.; Kim, A. Asynchronous Multiple LiDAR-Inertial Odometry Using Point-Wise Inter-LiDAR Uncertainty Propagation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 4211–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Yuan, S.; Cao, M.; Lyu, Y.; Nguyen, T.H.; Xie, L. NTU VIRAL: A visual-inertial-ranging-lidar dataset, from an aerial vehicle viewpoint. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2022, 41, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Carlone, L.; Dellaert, F.; Scaramuzza, D. On-Manifold Preintegration for Real-Time Visual-Inertial Odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.J.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. LIO-SAM: Tightly-coupled Lidar Inertial Odometry via Smoothing and Mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021; pp. 5135–5142. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.J.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. LVI-SAM: Tightly-coupled Lidar-Visual-Inertial Odometry via Smoothing and Mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 5692–5698. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, F. FAST-LIO: A Fast, Robust LiDAR-Inertial Odometry Package by Tightly-Coupled Iterated Kalman Filter. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 3317–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. Low-drift and real-time lidar odometry and mapping. Auton. Robot. 2017, 41, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.J. LeGO-LOAM: Lightweight and Ground-Optimized Lidar Odometry and Mapping on Variable Terrain. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 4758–4765. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Ye, H.; Pranata, C.E.; Han, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, M. LINS: A Lidar-Inertial State Estimator for Robust and Efficient Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 8899–8906. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Tightly Coupled 3D Lidar Inertial Odometry and Mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 3144–3150. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Pei, L.; Xiang, Y.; Zuo, X.; Yu, W.; Truong, T. P3-LINS: Tightly Coupled PPP-GNSS/INS/LiDAR Navigation System with Effective Initialization. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 8501813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gassner, M.; Werlberger, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Semidirect Visual Odometry for Monocular and Multicamera Systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, F. R3LIVE++: A Robust, Real-time, Radiance reconstruction package with a tightly-coupled LiDAR-Inertial-Visual state Estimator. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 11168–11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. VINS-Mono: A Robust and Versatile Monocular Visual-Inertial State Estimator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furgale, P.T.; Tong, C.H.; Barfoot, T.D.; Sibley, G. Continuous-time batch trajectory estimation using temporal basis functions. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 1688–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duberg, D.; Jensfelt, P. UFOMap: An Efficient Probabilistic 3D Mapping Framework That Embraces the Unknown. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6411–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tomasi, C. Good features to track. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 21–23 June 1994; pp. 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, F. ikd-Tree: An Incremental K-D Tree for Robotic Applications. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.10808. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, A. DVL-SLAM: Sparse depth enhanced direct visual-LiDAR SLAM. Auton. Robot. 2020, 44, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Deng, J.; Ming, R.; Lang, F.; Yang, X. SR-LIVO: LiDAR-Inertial-Visual Odometry and Mapping with Sweep Reconstruction. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 5110–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| State of ground truth, estimation, residual error | |

| subscript: IMU coordinate system, gyroscope, accelerometer, timestamp | |

| 3D position, velocity, rotation vector | |

| IMU basis of gyroscope and accelerometer, gravity vector | |

| Jacobian, covariance matrix of pre-integration on | |

| Feature map of the l-th Kalman filter | |

| 3D point at the current LiDAR coordinate system | |

| 3D point at the global coordinate system | |

| I | 2D pixel coordinate in the image |

| correspondence: LiDAR point, image point |

| RMSE Metric | Sensor Usage | EEE_01 | EEE_02 | EEE_03 | NYA_01 | NYA_02 | NYA_03 | SBS_01 | SBS_02 | SBS_03 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-LIO [22] | L1+I1 | 0.540 | 0.220 | 0.250 | 0.240 | 0.210 | 0.230 | 0.250 | 0.260 | 0.240 |

| Fast-LIVO [6] | L1+I1+C1 | 0.280 | 0.170 | 0.230 | 0.190 | 0.180 | 0.190 | 0.290 | 0.220 | 0.220 |

| DVL-SLAM [35] | L1+C1 | 2.880 | 1.650 | 3.080 | 2.090 | 1.450 | 1.820 | 1.080 | 2.310 | 2.230 |

| SVO [28] | I1+C1 | Fail | Fail | 4.120 | 2.290 | 2.910 | 3.320 | 7.840 | Fail | Fail |

| VINS-Fusion [30] | I1+C1 | 0.608 | 0.506 | 0.494 | 0.397 | 0.424 | 0.787 | 0.508 | 0.564 | 0.878 |

| R2Live [9] | L1+I1+C1 | 0.450 | 0.210 | 0.970 | 0.190 | 0.630 | 0.310 | 0.560 | 0.240 | 0.440 |

| M-LOAM [11] | L2 | 0.249 | 0.166 | 0.232 | 0.123 | 0.191 | 0.226 | 0.173 | 0.147 | 0.153 |

| D-EKF [13] | L2+I2 | 0.269 | 0.164 | 0.220 | 0.229 | 0.178 | 0.207 | 0.208 | 0.220 | 0.244 |

| IGE-LIO [7] | L1+I1 | 0.209 | 0.197 | 0.217 | 0.231 | 0.195 | 0.194 | 0.207 | 0.219 | 0.212 |

| R3Live [10] | L1+I1+C1 | 1.690 | − | 0.640 | 0.630 | 0.350 | 0.230 | 0.400 | 0.270 | 0.210 |

| SR-LIVO [36] | L1+I1+C1 | 0.210 | 0.230 | 0.220 | 0.180 | 0.190 | 0.200 | 0.120 | 0.220 | 0.210 |

| DLI (Our) | L2+I2 | 0.256 | 0.152 | 0.211 | 0.196 | 0.166 | 0.183 | 0.185 | 0.181 | 0.182 |

| DLIC (Our) | L2+I2+C2 | 0.237 | 0.146 | 0.208 | 0.166 | 0.143 | 0.170 | 0.162 | 0.160 | 0.173 |

| MAX RMSE Metric | EEE_01 | EEE_02 | EEE_03 | NYA_01 | NYA_02 | NYA_03 | SBS_01 | SBS_02 | SBS_03 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-LIO [22] | 0.633 | 0.732 | 0.638 | 0.649 | 0.463 | 0.542 | 0.654 | 0.587 | 0.513 |

| Fast-LIVO [6] | 0.586 | 0.628 | 0.582 | 0.641 | 0.459 | 0.488 | 0.588 | 0.556 | 0.492 |

| D-EKF [13] | 1.012 | 0.621 | 0.438 | 0.588 | 0.469 | 0.630 | 0.709 | 0.492 | 0.504 |

| DLI (Our) | 0.973 | 0.541 | 0.411 | 0.520 | 0.545 | 0.466 | 0.439 | 0.435 | 0.491 |

| DLIC (Our) | 0.519 | 0.407 | 0.364 | 0.608 | 0.443 | 0.455 | 0.420 | 0.415 | 0.464 |

| MAE Metric | EEE_01 | EEE_02 | EEE_03 | NYA_01 | NYA_02 | NYA_03 | SBS_01 | SBS_02 | SBS_03 |

| Fast-LIO [22] | 0.277 | 0.152 | 0.231 | 0.210 | 0.191 | 0.197 | 0.231 | 0.254 | 0.231 |

| Fast-LIVO [6] | 0.248 | 0.136 | 0.219 | 0.215 | 0.184 | 0.175 | 0.261 | 0.201 | 0.205 |

| D-EKF [13] | 0.252 | 0.141 | 0.208 | 0.190 | 0.161 | 0.181 | 0.198 | 0.207 | 0.232 |

| DLI (Our) | 0.242 | 0.129 | 0.199 | 0.167 | 0.134 | 0.150 | 0.165 | 0.159 | 0.163 |

| DLIC (Our) | 0.224 | 0.126 | 0.196 | 0.135 | 0.113 | 0.144 | 0.134 | 0.142 | 0.151 |

| RMSE Metric | RTP_01 | RTP_02 | RTP_03 | TNP_01 | TNP_02 | TNP_03 | SPMS_01 | SPMS_02 | SPMS_03 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-LIO [22] | 0.402 | 0.240 | 0.636 | 0.138 | 0.159 | 0.174 | 0.635 | 2.216 | 1.595 |

| Fast-LIVO [6] | − | − | − | 0.114 | 0.107 | 0.195 | 0.975 | 1.211 | 2.043 |

| D-EKF [13] | 0.298 | 0.165 | 0.633 | 0.096 | 0.109 | 0.178 | 0.363 | 2.047 | 1.505 |

| DLI (Our) | 0.216 | 0.157 | 0.572 | 0.095 | 0.104 | 0.144 | 0.301 | 1.898 | 0.684 |

| DLIC (Our) | − | − | − | 0.088 | 0.098 | 0.111 | 0.285 | 1.198 | 1.328 |

| MAX RMSE Metric | RTP_01 | RTP_02 | RTP_03 | TNP_01 | TNP_02 | TNP_03 | SPMS_01 | SPMS_02 | SPMS_03 |

| Fast-LIO [22] | 1.667 | 0.741 | 1.991 | 0.392 | 0.328 | 0.422 | 4.376 | 7.046 | 5.250 |

| Fast-LIVO [6] | − | − | − | 0.304 | 0.421 | 0.377 | 2.165 | 4.607 | 4.631 |

| D-EKF [13] | 1.902 | 0.498 | 2.003 | 0.332 | 0.485 | 0.604 | 1.957 | 8.055 | 5.695 |

| DLI (Our) | 0.782 | 0.339 | 1.976 | 0.310 | 0.401 | 0.421 | 1.112 | 5.432 | 3.305 |

| DLIC (Our) | − | − | − | 0.251 | 0.295 | 0.511 | 1.062 | 4.161 | 3.574 |

| MAE Metric | RTP_01 | RTP_02 | RTP_03 | TNP_01 | TNP_02 | TNP_03 | SPMS_01 | SPMS_02 | SPMS_03 |

| Fast-LIO [22] | 0.318 | 0.196 | 0.578 | 0.126 | 0.148 | 0.143 | 0.489 | 1.641 | 1.405 |

| Fast-LIVO [6] | − | − | − | 0.096 | 0.097 | 0.181 | 0.897 | 0.989 | 1.779 |

| D-EKF [13] | 0.287 | 0.150 | 0.563 | 0.078 | 0.121 | 0.152 | 0.287 | 1.554 | 1.318 |

| DLI (Our) | 0.252 | 0.143 | 0.517 | 0.075 | 0.093 | 0.102 | 0.260 | 1.388 | 0.464 |

| DLIC (Our) | − | − | − | 0.068 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.251 | 0.947 | 1.240 |

| Metrics | Fast-LIO [22] | Fast-LIVO [6] | D-EKF [13] | DLIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 0.101 | 0.071 | 0.068 | 0.062 |

| SSE | 12.338 | 10.212 | 10.075 | 9.241 |

| Noise Levels | Fast-LIO [22] | Fast-LIVO [6] | D-EKF [13] | DLIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.540 | 0.280 | 0.269 | 0.237 |

| 1 | 0.548 | 0.285 | 0.272 | 0.241 |

| 2 | 0.552 | 0.288 | 0.278 | 0.242 |

| 3 | 0.563 | 0.291 | 0.280 | 0.245 |

| 4 | 0.578 | 0.293 | 0.284 | 0.247 |

| 5 | 0.583 | 0.298 | 0.290 | 0.256 |

| Method | RMSE Metric | MAE Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline-1 | 0.250 | 0.210 |

| Baseline-2 | 0.284 | 0.233 |

| Baseline-1+A-I2P | 0.219 | 0.207 |

| Baseline-2+A-I2P | 0.231 | 0.211 |

| Baseline + Equation (8) (DLI) | 0.211 | 0.199 |

| Baseline + Equation (8) + A-I2P (DLIC) | 0.208 | 0.196 |

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| RMSE | 0.248 | 0.245 | 0.244 | 0.251 | 0.254 |

| 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | |

| RMSE | 0.244 | 0.241 | 0.234 | 0.221 | 0.238 |

| 2.5 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 12.5 | |

| RMSE | 0.221 | 0.219 | 0.228 | 0.231 | 0.234 |

| Method | Average Runtime per Loop |

|---|---|

| D-EKF | 18.89 ms |

| Baseline | 18.32 ms |

| Baseline + A-I2P | 24.31 ms |

| Baseline + Equation (9) (DLI) | 19.56 ms |

| Baseline + Equation (9) + A-I2P (DLIC) | 25.86 ms |

| Method | Sensor Usage | Peak Memory Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Fast-LIVO [6] | L1+C1+I1 | 1821 MB |

| Fast-LIVO † [6] | L2+C2+I2 | 3277 MB |

| DLIC | L2+C2+I2 | 2741 MB |

| Voxel Size | 0.025 m | 0.050 m | 0.100 m |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 0.201 m | 0.208 m | 0.352 m |

| Peak memory usage | 8421 MB | 2741 MB | 723 MB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, J.; An, P.; Yu, K.; Ma, T.; Fang, B.; Ma, J. An Efficient and Accurate UAV State Estimation Method with Multi-LiDAR–IMU–Camera Fusion. Drones 2025, 9, 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120823

Ding J, An P, Yu K, Ma T, Fang B, Ma J. An Efficient and Accurate UAV State Estimation Method with Multi-LiDAR–IMU–Camera Fusion. Drones. 2025; 9(12):823. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120823

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Junfeng, Pei An, Kun Yu, Tao Ma, Bin Fang, and Jie Ma. 2025. "An Efficient and Accurate UAV State Estimation Method with Multi-LiDAR–IMU–Camera Fusion" Drones 9, no. 12: 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120823

APA StyleDing, J., An, P., Yu, K., Ma, T., Fang, B., & Ma, J. (2025). An Efficient and Accurate UAV State Estimation Method with Multi-LiDAR–IMU–Camera Fusion. Drones, 9(12), 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120823