1. Introduction

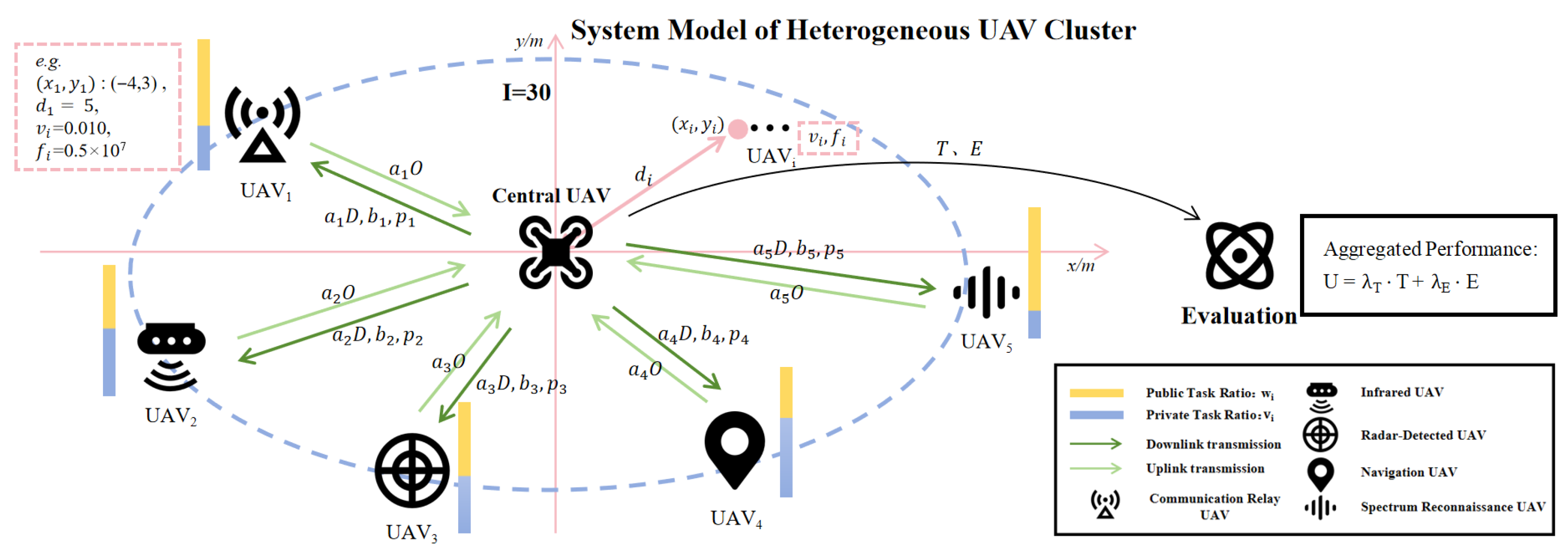

With the rapid advancement of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology and artificial intelligence, UAV swarms are evolving from simple formations characterized by “homogeneity and single-task capabilities” to intelligent systems featuring “heterogeneity and multifunctionality.” Within next-generation non-terrestrial networks (NTNs) and 6G application scenarios, diverse UAVs—including communication relays, infrared monitors, navigation units, spectrum scouts, and radar detectors—are organically integrated into a cluster system characterized by unified “communication, sensing, remote control, and guidance” capabilities. Such systems not only execute dedicated private missions (e.g., infrared UAVs performing target identification and navigation nodes conducting positioning calibration) but also collectively undertake shared system tasks (e.g., large-scale situational awareness, joint reasoning, and emergency communication support) through information sharing and resource coordination, significantly enhancing overall effectiveness [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A growing body of research and applications indicates that heterogeneous UAV swarms are emerging as a critical trend in unmanned system development and a vital component of future integrated air–ground–space networks [

5,

6].

Notably, with the emergence of large-scale artificial intelligence models, UAV clusters are gaining unprecedented capabilities. These models enable heterogeneous UAV nodes to perform more complex collaborative tasks—such as cross-modal target recognition, intelligent navigation, emergency communications, and scenario simulation—driven by multi-source sensor data. This is achieved through unified semantic representation, cross-modal information fusion, and powerful reasoning capabilities. However, despite these advances, the introduction of foundation models also exposes a significant algorithmic gap between the computational demands of large-model inference and the limited onboard resources available in UAV clusters. This trend is propelling UAV swarms toward “large-modelization”: some nodes focus on private tasks, while others collectively support public tasks through knowledge sharing and unified reasoning powered by large models. Bridging this gap requires a new generation of cooperative optimization algorithms that can maintain decision quality while drastically reducing computational and communication costs.

Large-model inference typically demands substantial computational power and high-throughput communication bandwidth. In practice, executing a single inference of a foundation model often requires billions of floating-point operations and extensive memory access, which already pose challenges even for edge servers [

7]. In UAV swarm systems, however, individual aerial nodes are generally equipped with lightweight processors and limited battery capacity, making it difficult to sustain the intensive workload of on-board inference. At the same time, wireless links among UAVs usually offer constrained spectrum resources and are vulnerable to channel fading and interference, resulting in insufficient throughput for the massive parameter exchanges required by large-model inference. These constraints not only hinder the direct deployment of large AI models on UAV nodes, but also amplify the energy–latency trade-off: increasing computational frequency accelerates energy depletion, while expanding transmission bandwidth intensifies spectrum contention and inter-node interference. Overall, reconciling the inherent resource scarcity of UAV swarms with the heavy demands of large-model inference is one of the most critical challenges in practical UAV intelligence. Therefore, addressing the scalability bottleneck between large-model reasoning and swarm-level coordination has become an open research problem that current UAV optimization frameworks cannot adequately solve.

In recent years, the application of multi-agent deep reinforcement learning (MADRL) in drone swarms has gained momentum, offering novel solutions to the aforementioned challenges. Existing studies demonstrate that MADRL outperforms traditional optimization methods in typical scenarios such as integrated air–ground networks, vehicle-to-everything edge computing, drone-assisted internet of things (IoT) systems, and drone edge resource management [

8,

9,

10]. Reinforcement learning frameworks enable the concurrent enhancement of task offloading, resource scheduling, and energy efficiency optimization in complex dynamic environments, demonstrating superior adaptability and scalability compared to traditional approaches [

11,

12,

13]. Concurrently, advancements in core algorithms such as centralized training–distributed execution (CTDE), counterfactual policy gradient, and soft actor–critic have significantly improved training stability and decision accuracy [

14,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, most existing MADRL frameworks are designed under full-model assumptions and overlook the constraints of computation, bandwidth, and latency that dominate large-model-driven UAV clusters.

More recent research has further integrated emerging technologies such as reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RISs), 3D trajectory planning, and energy-efficient scheduling, continuously advancing the evolution of UAV cooperative optimization [

17,

18,

19]. Against this backdrop, MADRL and large AI models form a natural complementarity: the former provides dynamic scheduling and online optimization capabilities for UAV swarms, while the latter plays a central role in semantic understanding and cross-modal reasoning. Their integration holds promise as a key direction for the intelligent evolution of heterogeneous UAV systems.

Nevertheless, existing approaches such as weighted multi-agent deep deterministic policy gradient (WMADDPG) and multi-agent soft actor–critic (MASAC) still suffer from high computational complexity, slow convergence, and significant deployment overhead, particularly when the number of devices increases or node heterogeneity intensifies [

20]. These limitations constrain their application in resource-constrained UAV clusters. This motivates the present work, which aims to close this gap by proposing a low-complexity multi-agent optimization framework that preserves MASAC’s stability while achieving near-constant parameter scalability. To address this issue, this paper proposes a low-complexity multi-agent optimization method based on the MASAC framework. Through parameter sharing, lightweight network architecture design, and a resource proportional normalization mechanism, it significantly reduces the computational burden of training and deployment while maintaining performance. In summary, the contributions of this work are threefold: (1) a scalable MASAC architecture integrating parameter sharing and twin-critic regularization; (2) a lightweight design that achieves over 14× parameter compression; and (3) a set of adaptive training mechanisms ensuring stability and rapid convergence in heterogeneous UAV swarms. The method also naturally accommodates a dual-layer structure of “private tasks–public tasks,” providing scalable algorithmic support for the future evolution of heterogeneous UAV swarms toward “large-modelization.”

As summarized in

Table 1, prior MADRL-based approaches—such as MADDPG, WMADDPG, and MASAC—have progressively improved UAV coordination through centralized training–decentralized execution (CTDE) mechanisms. However, they still face scalability and efficiency challenges when extended to large-scale heterogeneous UAV clusters. In contrast, our proposed low-complexity MASAC integrates parameter sharing, twin-critic regularization, and adaptive entropy scheduling to achieve near-constant parameter scalability while maintaining training stability. This design enables efficient deployment in large-model-driven UAV systems, bridging the gap between algorithmic feasibility and real-world applicability.

5. Complexity Reduction Methods

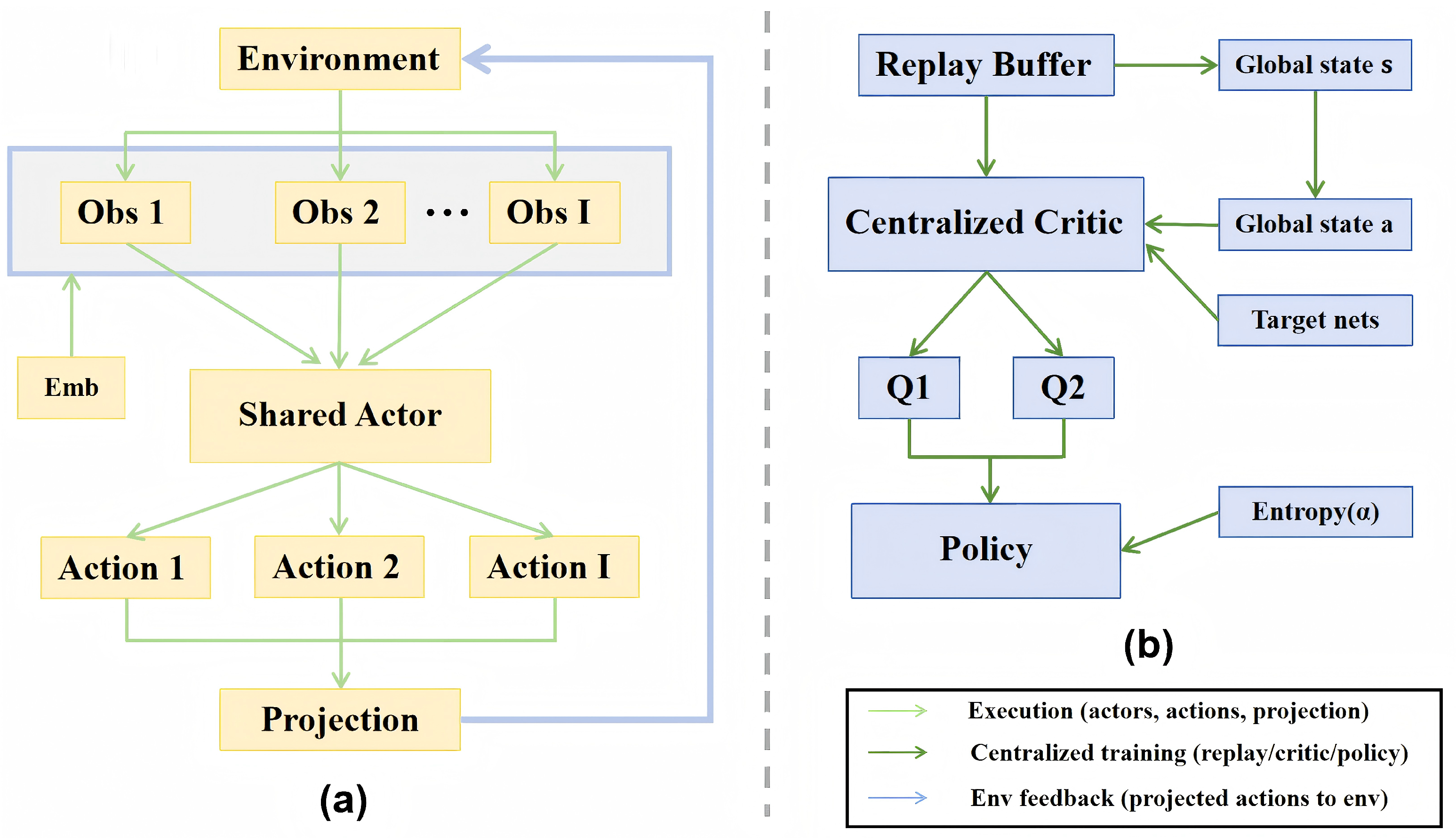

To intuitively present the structural adjustments made in this chapter, the overall algorithm framework with complexity reduction mechanisms is illustrated in

Figure 3. The figure highlights how parameter sharing, structural lightweighting, and training stabilization are integrated into the MASAC framework. Specifically, the left-hand side depicts the training loop with entropy scheduling, the replay buffer, and optimization; the middle block illustrates the shared actor enhanced by device embeddings and projection; and the right-hand side shows the centralized critic with twin Q-heads and the min aggregator. This visual overview provides context for the following sections, which detail each component and its role in reducing computational and memory overhead while maintaining training robustness.

This chapter systematically outlines three approaches—parameter sharing, structural lightweighting, and training robustness—to reduce computational complexity without altering problem assumptions or interfaces. These adaptations address the real-time and resource-constrained demands of UAV swarms. The core idea is to achieve maximum parameter and computational savings with minimal structural modifications within the CTDE framework. A set of training-side mechanisms aligned with optimization objectives ensures that policy performance and convergence stability are maintained or even enhanced under low-cost conditions.

5.1. Parameter Sharing at the Model Level

5.1.1. Device-Conditioned Shared Actor (DCSA)

In traditional multi-agent reinforcement learning, each agent typically maintains an independent policy network. This approach leads to linear growth in parameter size and computational overhead in large-scale UAV scenarios. To address this, we employ parameter sharing by retaining only one global actor network. By introducing device identity embedding vectors, different UAVs can generate differentiated actions within the same network. Specifically, for the

ith UAV, its input is concatenated from the local observation

and the device embedding

:

Here,

represents local features such as channel gain and computational power, while

denotes a low-dimensional, learnable representation of the UAV node identity. The shared actor network

processes the input

to output continuous actions:

where

denotes the public task allocation ratio and

represents the bandwidth allocation ratio.

Through this design, the parameter scale of the actor network no longer increases linearly with the number of heterogeneous UAVs I, but remains at a constant level. Simultaneously, the device embedding vector ensures that different drones can still learn differentiated strategies under the shared architecture, thereby balancing model lightweighting and strategy personalization [

21].

5.1.2. Centralized Twin Critic (Shared Backbone + Dual Head)

In multi-agent reinforcement learning, value function estimation often suffers from overestimation bias, leading to unstable policy updates. To address this issue, this paper introduces a twin-critic architecture based on centralized critics. This approach employs a shared backbone network for global feature extraction, which then branches into two independent Q-value heads.

Specifically, the centralized critic receives the global state

and joint action

. It first obtains representations through the shared feature extractor

:

Subsequently, two independent Q-heads provide estimates:

During policy updates, a minimum value decision mechanism is employed:

effectively mitigating value function overestimation.

This “shared-backbone + dual-head” design avoids the redundant overhead of multiple independent critics while maintaining estimation robustness. This approach enhances training stability while ensuring model compactness.

5.1.3. Qualitative Comparison of Parameters and Computational Complexity

The parameter scale of this paper converges from O(I) networks to “a single shared actor + a single shared-backbone critic + two linear Q-heads.” The drone identity embedding introduces only a minimal increment proportional to I × embedding dimension. Forward computation similarly converges from multiple parallel branches to a single reused backbone. The primary increase with drone count stems from input concatenation and lightweight loops required to generate actions for each drone, with an overall growth rate significantly lower than that of independent network schemes. This organization proves particularly effective in scenarios with I = 30 devices, keeping both inference latency and memory overhead within manageable ranges.

5.2. Structural Lightweighting

5.2.1. Fixed-Width MLP Backbone

For the feature extractors in both actor and critic backbone networks, this paper employs fixed-width Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs). Unlike variable-width or low-rank approximation designs, this approach maintains structural simplicity and avoids additional implementation complexity. Between the input and output layers, the network width is fixed at the preset value

, with each layer structured as

where

denotes the input to layer

l, and

and

represent the weight matrix and bias of the linear layer, respectively.

This fixed-width MLP backbone maintains sufficient expressive power while avoiding network size inflation as the number of drones increases. Combined with parameter sharing strategies, its overall complexity remains within acceptable limits, providing a stable foundation for subsequent normalization and residual mechanisms.

5.2.2. Normalization and Residual Mechanisms

To further enhance training stability, this paper introduces normalization and residual structures in key layers of the MLP backbone. First, Layer Normalization standardizes the output of linear layers:

This is then directly added to the input vector to form a residual connection, followed by nonlinear activation:

This architecture effectively mitigates gradient vanishing or exploding issues in moderately deep networks, ensuring numerical stability across drones of varying scales while sharing parameters. Experiments demonstrate that this mechanism significantly reduces training jitter and accelerates convergence, serving as a crucial auxiliary means for complexity optimization.

5.3. Training Stability and Efficiency

5.3.1. Experience Replay and Target Network

In reinforcement learning, training often encounters two common issues: first, correlated sampling data leads to unstable training; second, value function updates are prone to oscillation. This paper employs two mechanisms—replay buffer and target network—to address these challenges.

The concept behind experience replay is straightforward: trajectories generated by the agent during interactions are stored in an “experience pool.” During training, a batch of data is randomly sampled from this pool:

This approach breaks the temporal correlation between samples, stabilizing training while improving data utilization.

The target network prevents overly aggressive Q-value updates. When updating the critic, a delayed target network calculates the temporal difference objective:

where

represents the target network’s estimate and

denotes the discount factor. Since the target network’s parameters update more slowly, it acts as a “smoother” during training, preventing significant oscillations in the value function.

In summary, experience replay resolves data correlation issues, while the target network reduces volatility in value function updates. Together, they make the training process more robust and reliable in large-scale unmanned scenarios.

5.3.2. Entropy Coefficient Scheduling Mechanism

A core challenge in policy optimization is balancing exploration and exploitation: insufficient exploration traps the policy in local optima (e.g., uniform distribution), while excessive exploration hinders training convergence. To address this, this paper introduces an entropy regularization term within the MASAC framework and employs piecewise entropy coefficient scheduling to dynamically adjust exploration intensity.

In the standard SAC algorithm, the policy objective function is defined as follows:

where

represents the entropy coefficient controlling the exploration weight. A larger coefficient encourages a more uniform action distribution, while a smaller coefficient prioritizes pursuing high Q-values.

This model does not fix but employs a piecewise scheduling approach: during the early training phase, a large is set to ensure sufficient exploration; in the middle and late phases, is gradually reduced, allowing the policy to leverage learned experience more effectively. This approach is analogous to equipping exploration with a “gearbox”: more experimentation early on, more utilization later, and avoiding getting stuck in the middle.

5.3.3. Reward Normalization and Clipping

In large-scale drone optimization problems, the magnitude difference between the delay component and energy consumption component of reward values is often substantial. Feeding these raw rewards directly to the algorithm can easily lead to numerical instability during training, such as gradient explosion or convergence oscillations.

To address this, this paper introduces a reward standardization and clipping mechanism during training.

First, rewards are standardized to maintain a relatively stable scale:

where

and

denote the mean and standard deviation of the reward, respectively. This step smooths the reward distribution, preventing rewards of vastly different magnitudes from “canceling each other out.”

Second, to prevent extreme values from disrupting training, rewards are clipped using the Softplus function:

This ensures that even extremely large reward values are gently “compressed”, preventing disruption to the training process.

In summary, reward normalization stabilizes the training process, while reward clipping mitigates extreme cases. Together, these techniques enable the algorithm to converge faster and more smoothly in complex unmanned aerial scenarios.

5.4. Complexity Analysis

To rigorously evaluate the complexity characteristics of the proposed “shared policy + shared value backbone + lightweight embedding” framework, we analyze both parameter scale and computational cost as functions of the swarm size I.

For the

actor network, since parameters are shared across all UAVs, the majority of the model parameters remain constant regardless of

I. The only scaling component originates from the device identity embedding, whose size grows linearly with the swarm size

I and the embedding dimension

. Therefore, the parameter complexity of the actor network is as follows:

Here, refers to the asymptotic upper bound in algorithmic complexity analysis, while denotes the asymptotically tight bound.

For the

critic network, the centralized twin-critic architecture with a shared backbone ensures that its main parameter scale also remains constant. The only additional growth arises from concatenating

I device observations of dimension

, yielding

Accordingly, the overall parameter complexity can be expressed as follows:

where

C is the dominant constant term contributed by the shared actor and critic backbones. Empirical results confirm this formulation, giving an approximate decomposition:

This indicates that the parameter overhead is primarily constant, with only a negligible linear increment per additional UAV—far more efficient than the traditional “one network per UAV” approach with large coefficients.

6. Experiments and Comparative Analysis

6.1. Experimental Setup and Platform

All experiments were conducted in a self-developed heterogeneous UAV swarm simulation environment. The objective was to minimize the utility function while jointly optimizing the allocation ratio of shared tasks and downlink bandwidth.

All experiments in this study were conducted within a high-fidelity heterogeneous UAV swarm simulation platform developed by our research team. At the current stage, physical UAV flight experiments are not yet feasible due to the lack of an available real-world testbed. Nevertheless, the simulation environment is constructed using real UAV system parameters—including transmission power limits, bandwidth constraints, channel fading, and computational capacity—to closely reflect realistic operational conditions. This design ensures that the simulation results provide meaningful insights into practical UAV swarm deployment scenarios.

The objective of the experiments is to minimize the system utility function while jointly optimizing the allocation ratio of shared tasks and downlink bandwidth.

6.1.1. Environment and Task Parameters

The experiment employs a centralized training–distributed execution (CTDE) single-step simulation environment with a fixed number of heterogeneous UAV nodes set to I = 30. Each round, the environment generates observations for each UAV node based on the current round’s task load, UAV node computational power, and wireless channel conditions. Actions consist of two-dimensional continuous decisions: “task allocation ratio” and “bandwidth allocation ratio,” with values constrained within [0, 1]. The channel model accounts for shadow fading and is constrained by each UAV node’s bandwidth and downlink power. Before executing actions, the environment projects them onto the feasible domain and normalizes them to satisfy the overall system bandwidth constraint. Rounds are single-step to avoid interference from cumulative errors across steps. A global uniform reward signal is used, incorporating task allocation variance regularization to encourage load balancing. The evaluation phase uniformly employs deterministic execution (removing exploration noise). Specific environment and task parameters are detailed in

Table 4.

6.1.2. Model and Algorithm Configuration

Beyond structural differences and corresponding training mechanisms, the original and optimized models share identical training hyperparameters and evaluation metrics. To align with current implementations,

Table 5 lists key structural and training/evaluation parameters used for the optimized model in this chapter; the unoptimized model is annotated only where parameters differ.

6.1.3. Hardware and Software Platforms

Hardware and software platforms are as shown in

Table 6.

6.2. Performance Guarantees for Optimized Models at Small Scale ()

Under large-scale heterogeneous UAV clusters, the analytical optimal solution for the utility function U is difficult to obtain directly. To establish a theoretical baseline, we derived an analytical solution for the problem under the small-scale condition I = 5. This solution serves as a performance upper bound for comparison with the results of the optimization model.

Based on the modeling in

Section 3, under the configuration I = 5, the problem can be decomposed into the following three subproblems:

- (1)

Optimal Task Allocation Structure

From the KKT conditions, the active UAV nodes in the optimal solution satisfy , where denotes the active set; inactive nodes adopt the boundary solution .

- (2)

Downlink Bandwidth Allocation

Under optimal allocation, downlink transmission delays are equal across the active set . This yields the closed-form bandwidth allocation .

- (3)

Uplink Bandwidth Allocation

Applying the KKT conditions, the optimal uplink allocation satisfies , where is the Lagrange multiplier. This ultimately reduces to a one-dimensional equation: . Solving yields the unique optimal uplink bandwidth allocation .

Combining the three components, the theoretical optimal value for I = 5 is

Experimental comparisons show that under identical conditions, the optimized model yields

As shown in

Table 7.

When I = 5, the uniformly distributed resource allocation yields U = 0.005764. Thus, the optimized model achieves of the theoretical optimum. This result demonstrates that the proposed lightweight optimization framework can approximate theoretical limits in small-scale UAV clusters, providing robust support for subsequent complexity analysis and performance validation in large-scale scenarios.

6.3. Training Efficiency Comparison Across Different Architectures

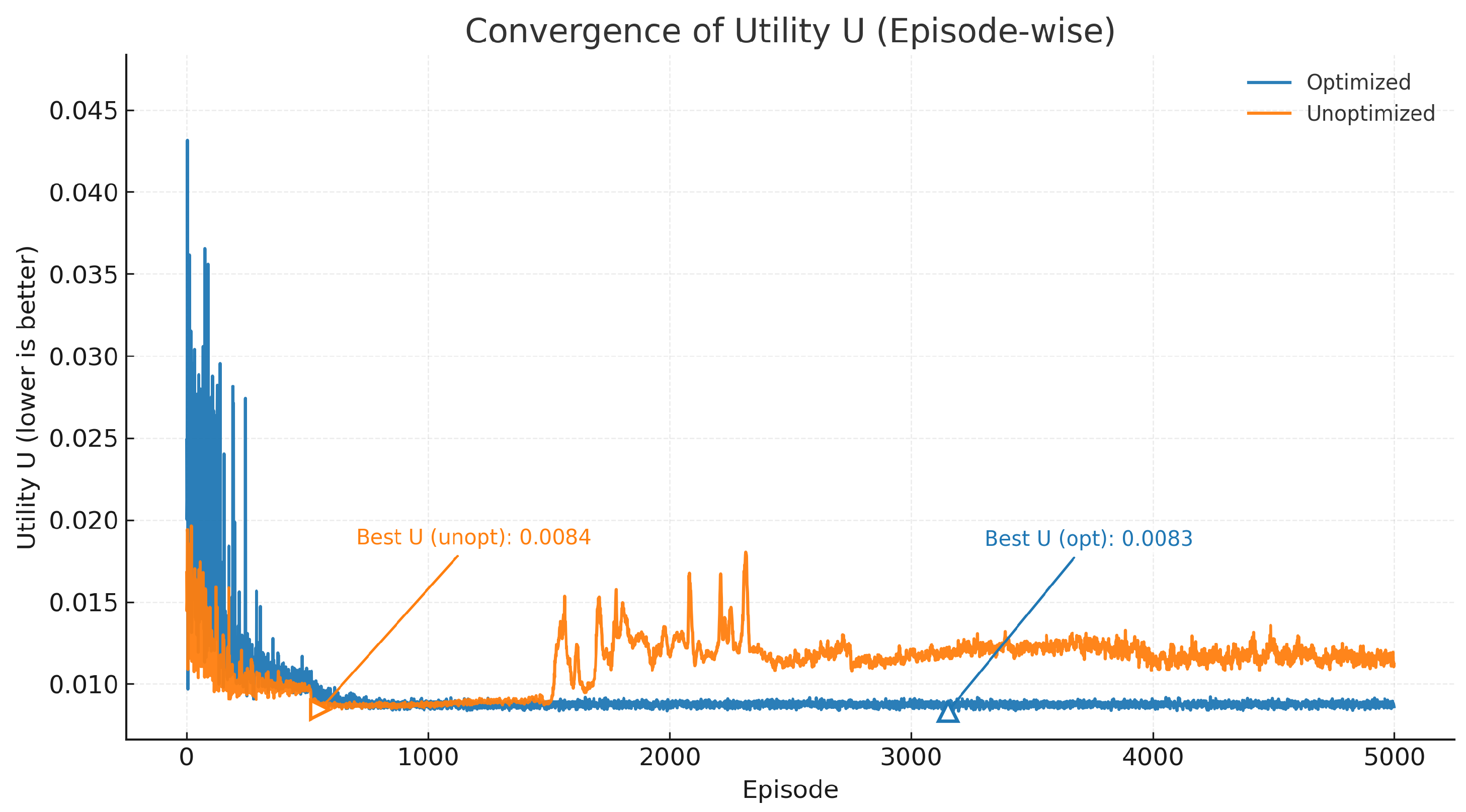

To evaluate the impact of optimization strategies on training efficiency and convergence performance, this study conducted comparative experiments between the unoptimized original MASAC architecture and the optimized MASAC architecture. Experiments were run under identical environmental parameters, task configurations, and random seed conditions to ensure reproducibility and fairness of results.

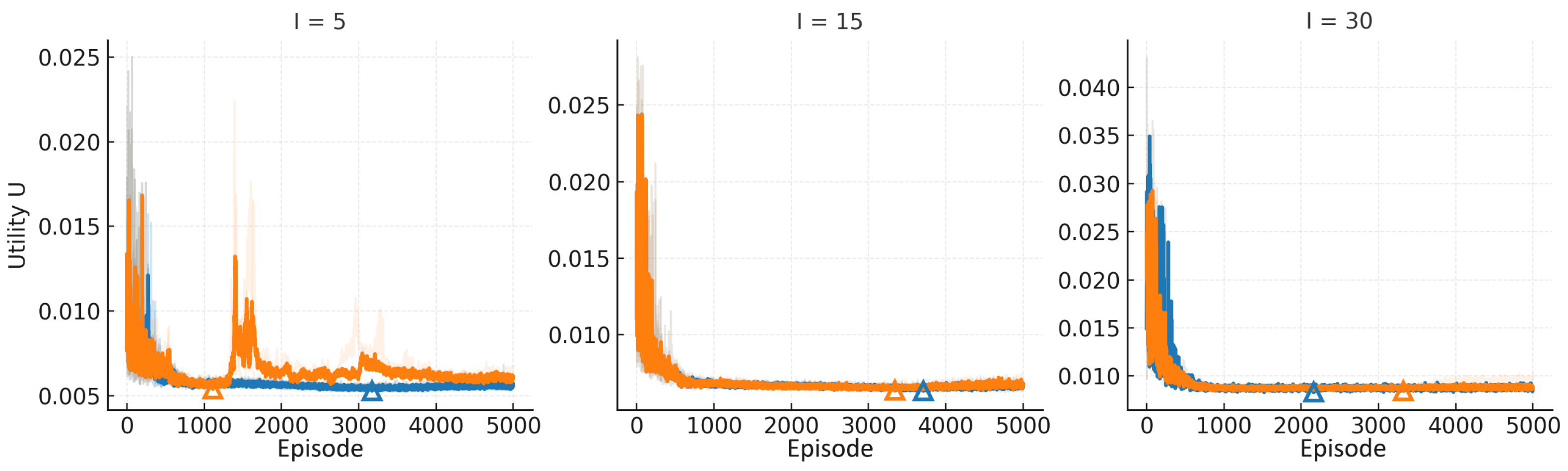

As shown in the training results in

Table 8 and

Figure 4, the unoptimized model exhibits significant fluctuations during training, with noticeable performance regression in the mid-to-late stages. It ultimately fails to converge within 5000 training steps, achieving its best result only during a brief convergence phase early in training, demonstrating unstable performance. In contrast, the optimized model converged faster and more smoothly near the optimal value of U = 0.008210, outperforming the unoptimized version. Furthermore, the training time for the optimized version was significantly reduced—from 4839.33 s for the original structure to 332.92 s—demonstrating that the optimized model substantially lowers computational complexity while maintaining performance.

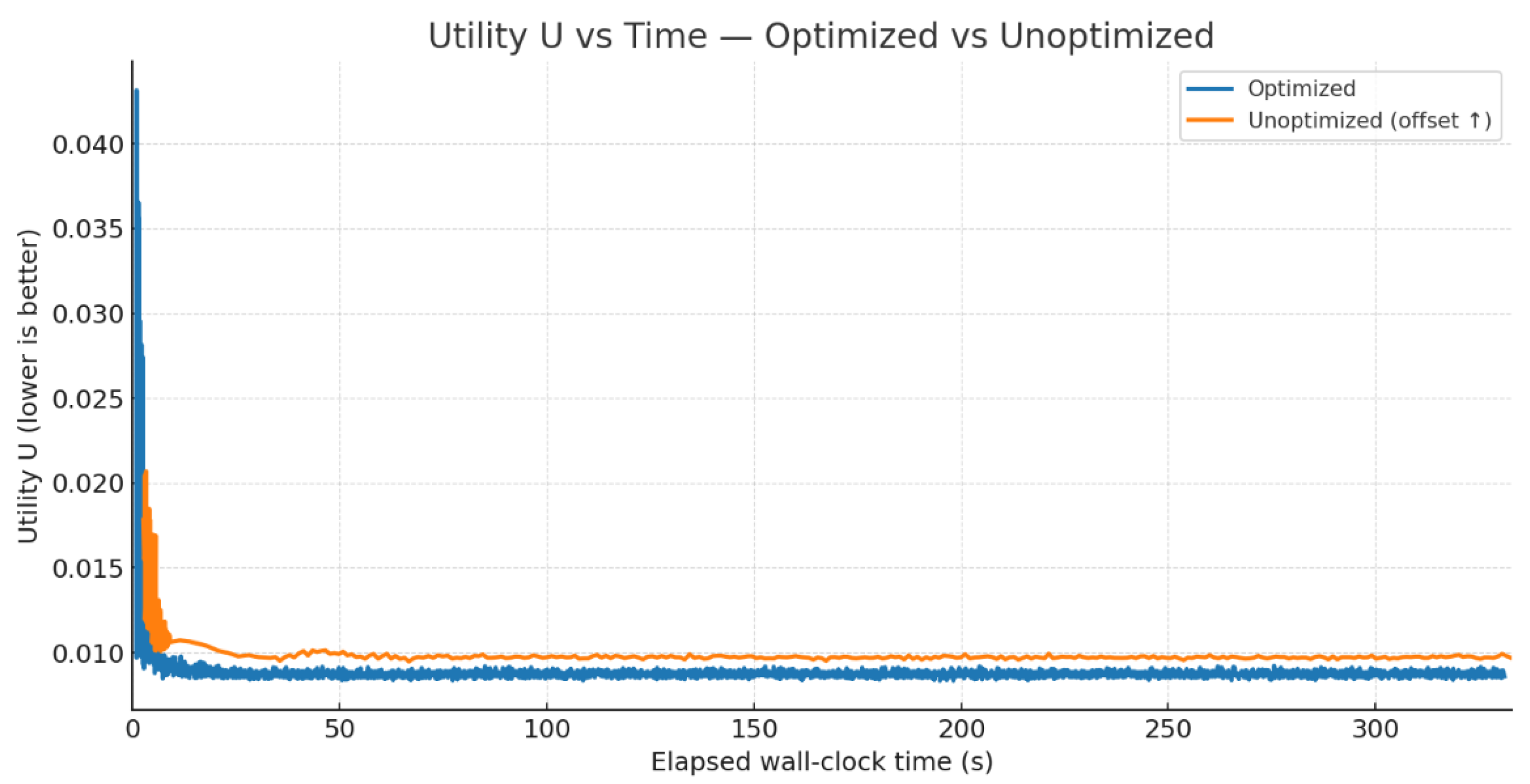

To compare the optimization effectiveness of both models within the same timeframe, we plotted a comparison of

U-convergence curves over identical durations, as shown in

Figure 5. On the time axis scaled to the maximum total training duration of the optimized model, the unoptimized curve exhibits no significant exploration transition within the initial 0–500 s, indicating that exploration has not yet commenced. In contrast, the optimized curve achieves primary convergence and enters a low-fluctuation steady state within the same timeframe. This demonstrates that under identical time budgets, the optimized architecture achieves superior performance more rapidly.

The above comparison demonstrates that the optimized scheme offers significant advantages in training time without compromising convergence performance. Furthermore, its convergence process is more stable and smoother, indicating a substantial reduction in computational complexity for this problem.

6.4. Ablation Studies

All ablation experiments in this section compare with the optimized model described above, aiming to demonstrate the effectiveness of reducing computational complexity while improving performance. Specific ablation experiment configurations are shown in

Table 9.

Models A1–A3 retain all other configurations consistent with A0 except for the modifications listed above. Each model was independently trained three times with random seeds on the dataset to enhance the persuasiveness of this section.

6.4.1. Entropy Temperature Strategy Ablation (A1)

The objective of this subsection’s experiments is to compare the effects of two entropy temperature designs on training stability and convergence efficiency. The A0 model’s

was manually scheduled with a decay-then-increase pattern (first decreasing from 0.20 to 0.05 and then increasing to 0.25). To validate this strategy’s model improvement, the A1 model’s

was set to a constant 0.05. The convergence quality is measured in

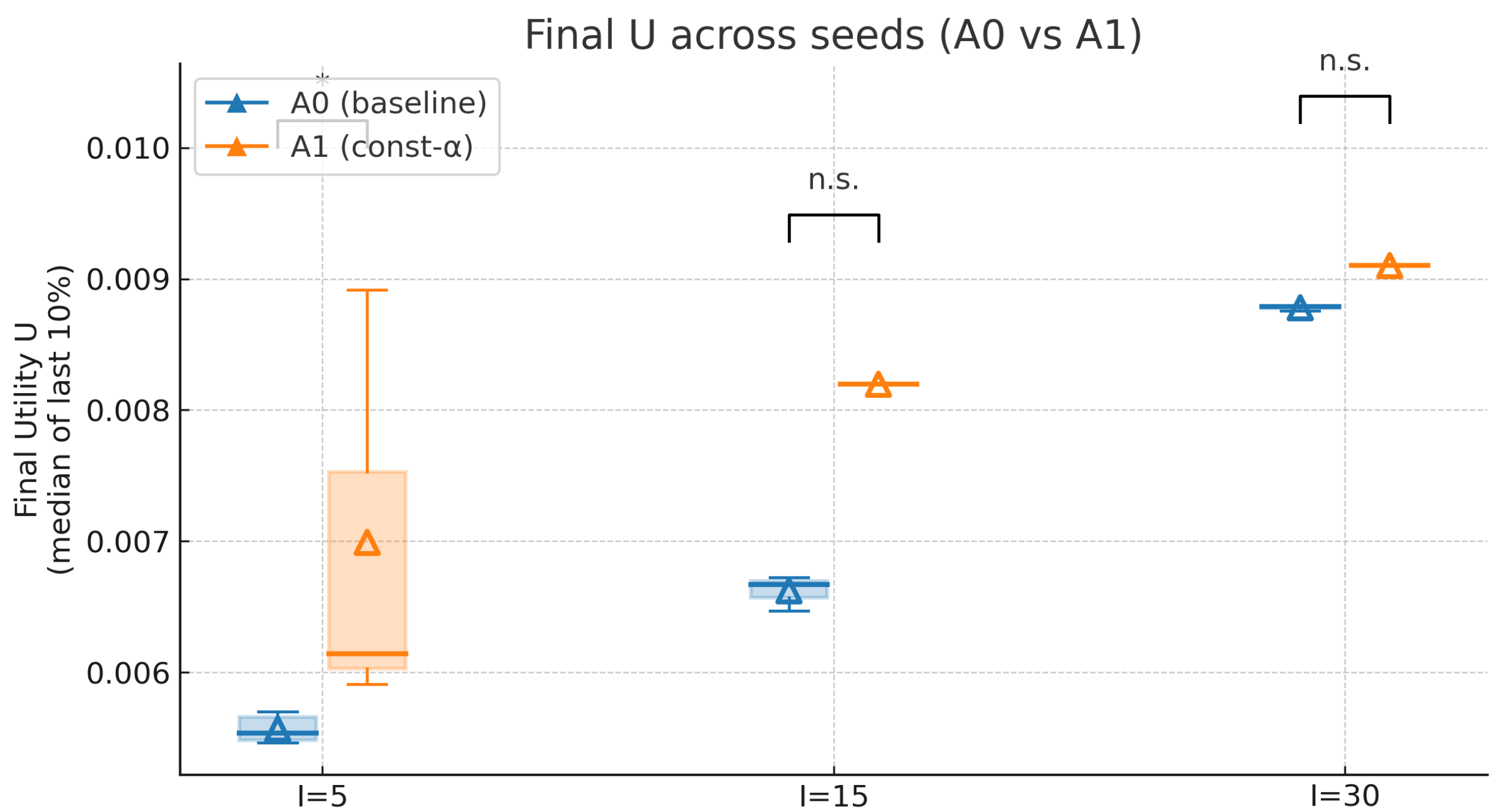

Figure 6. The convergence speed and time efficiency are measured in

Figure 7.

From

Figure 6, we compare the median U values of models A0 and A1 during the final

of training iterations across three scales (

). Results show the following: At a small scale I = 5, A1 exhibits significantly poorer convergence quality than A0, with a higher median and markedly increased variance. At medium–large scales I = 15 and I = 30, differences are not significant (labeled “n.s.”). However, A1’s median remains systematically higher than A0’s, indicating that fixed entropy temperature easily leads to “under-exploration/premature convergence,” leaving a performance gap in the tail. Across all three scales, the manually adjusted “decline-then-increase” entropy temperature schedule provides sufficient exploration early on and boosts perturbations later to escape suboptimal solutions. This approach enhances stability at small scales while maintaining a final U value no worse than that of the constant strategy at larger scales.

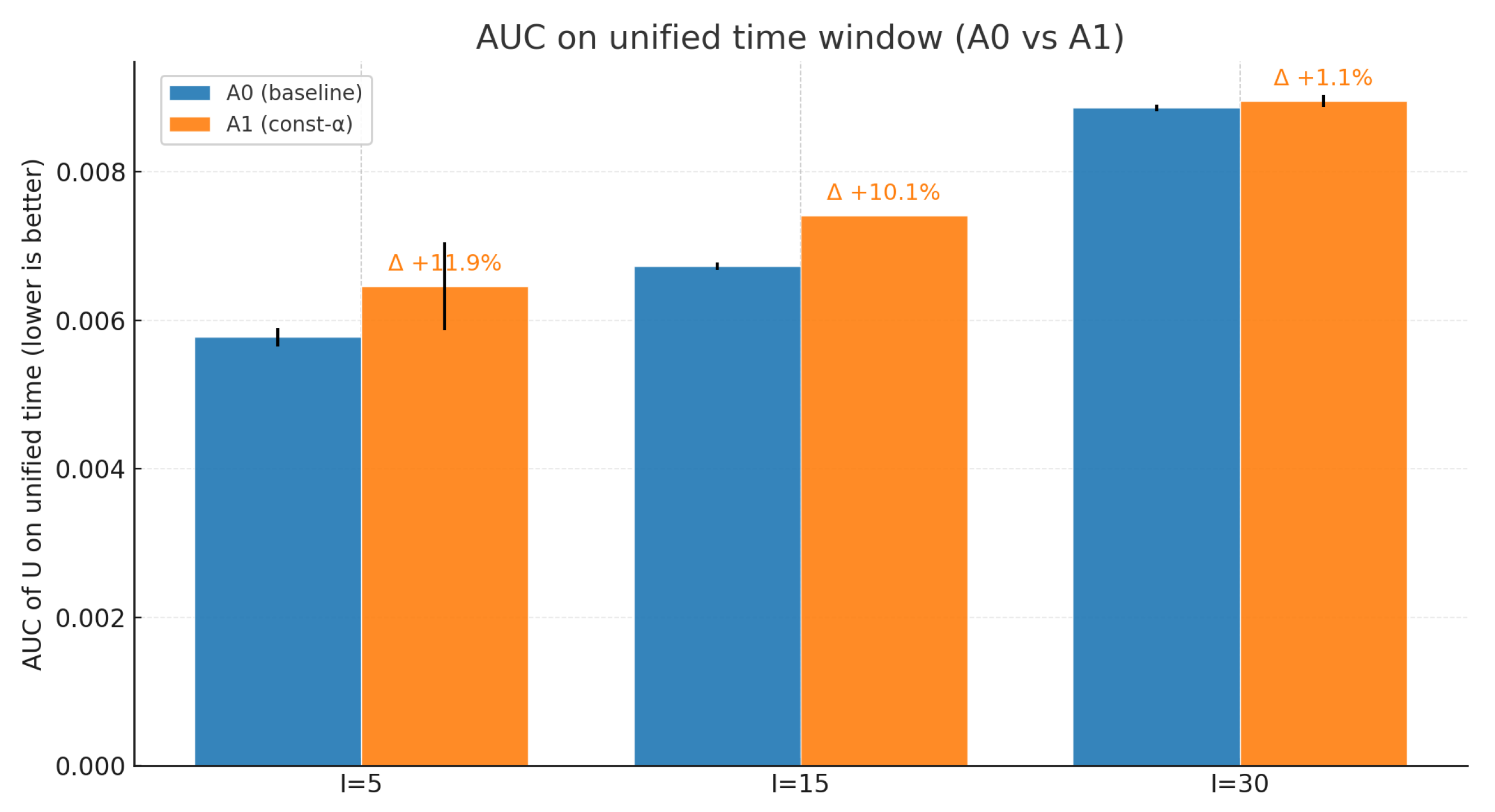

Figure 7 shows that across all three scales (

), A1 consistently achieves a higher AUC than A0, with the gap narrowing as scale increases. A smaller AUC indicates that the model reaches a lower U faster and more stably within the same timeframe; thus, A0 demonstrates overall superiority over A1 in temporal efficiency and convergence speed. Error bars reveal that A1 exhibits greater volatility, suggesting that a fixed entropy temperature fails to adapt well to training demands across different phases. In contrast, A0’s “decline-then-increase” scheduling achieves rapid convergence early on while maintaining moderate exploration later, resulting in a lower integral error within the same timeframe.

Summarizing this section’s experiments, altering only the entropy temperature strategy resulted in A1’s performance deteriorating compared to A0 in both temporal efficiency and convergence robustness. This confirms that the current entropy temperature adjustment strategy is essential for ensuring model performance.

6.4.2. Removing Device Identity Embeddings (A2)

This subsection removes the learnable embedding of discrete UAV device IDs to assess its impact on model performance.

Figure 8 measures the effect on convergence, while

Figure 9 evaluates model complexity.

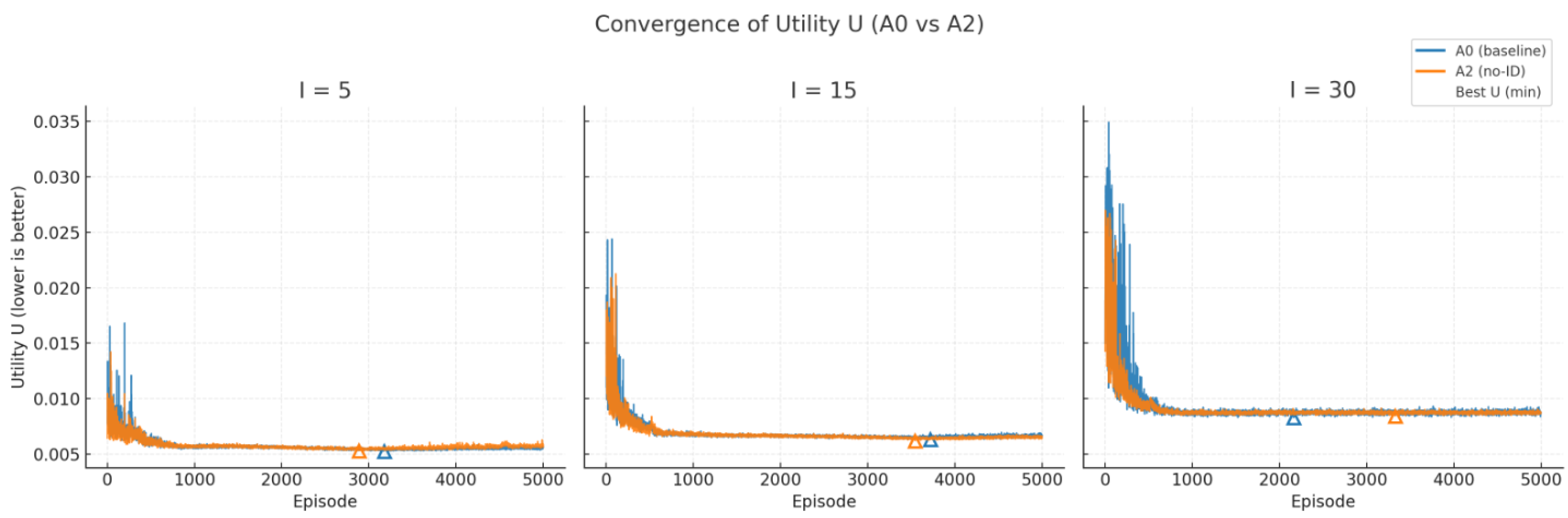

As shown in

Figure 8, for simulations across three scales, the overall jitter amplitude of A0 is smaller than that of A2 during the mid-to-late stages, with this difference becoming more pronounced as I increases. The best U of A0 is typically slightly lower than that of A2, though the difference is not significant.

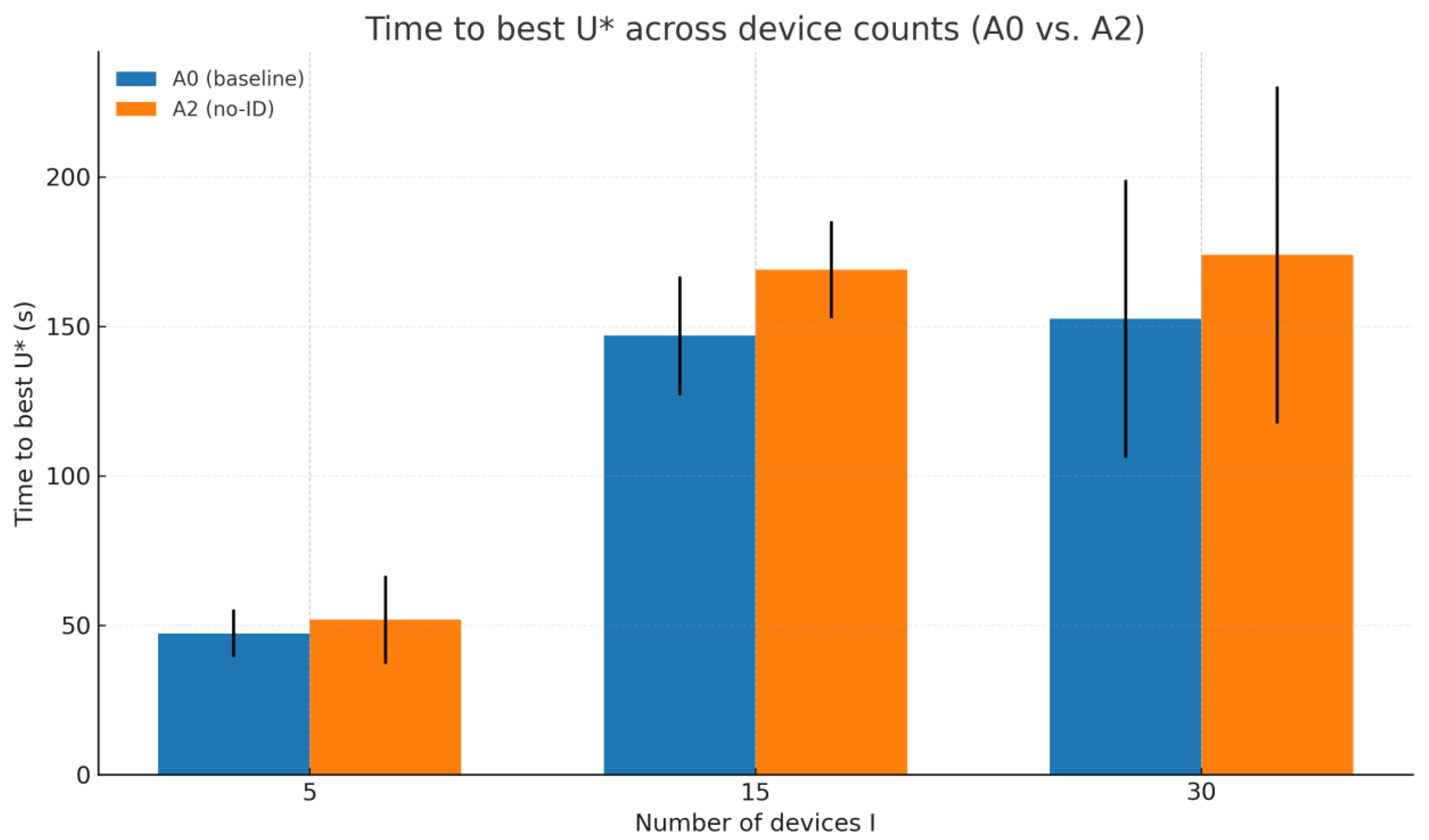

From

Figure 9, it is evident that the A2 model converges to the optimal U significantly slower, and the gap with the A0 model widens as the device scale I increases: at the small scale I = 5, A2 and A0 are essentially consistent, indicating that the benefits of identity embedding are limited under weak heterogeneity and low interaction intensity; when scale increases to I = 15, A2’s time cost rises by approximately

compared to A0, expanding further to

at I = 30. Concurrently, A2 exhibits higher variance at medium-to-large scales.

Overall, identity embedding primarily accelerates convergence to optimal solutions rather than improving final optimal values, with more pronounced effects in large-scale and highly heterogeneous scenarios.

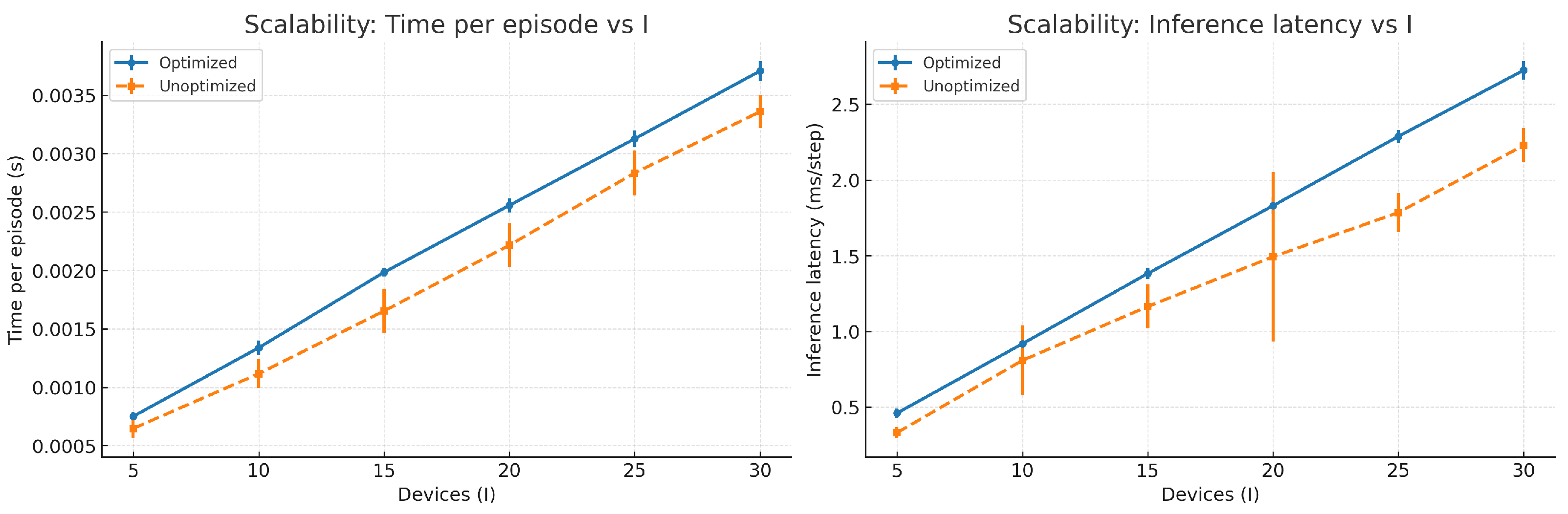

6.4.3. Removing Twin Critic (A3)

This subsection replaces the twin critic with a single critic in A0 to evaluate the practical contribution of the “dual critic” in suppressing overestimation bias and enhancing convergence stability and efficiency.

Figure 10 shows that A3 maintains convergence patterns similar to those of A0, indicating that replacing the twin critic with a single critic does not alter the model’s scientific validity or convergence behavior.

As shown in

Figure 11, when I = 5, A3 and A exhibit similar convergence times to the optimal U value, but A3 demonstrates significantly higher variance. As the scale increases to I = 15 and I = 30, A3’s average optimization time consistently exceeds that of A0 (by approximately

), with variance further amplifying at I = 30, revealing distinct “slow-converging tails” in individual runs. Overall, the single-critic approach fails to deliver training efficiency advantages, instead introducing longer convergence times and higher uncertainty at medium-to-large scales. This demonstrates that the twin critic provides faster and more stable convergence characteristics at comparable computational complexity.

As shown in

Figure 12, across all three scales, A3’s box and mean triangle consistently exceed those of A0, indicating larger U values for A3 during late convergence. A3’s taller box reflects greater inter-seed variability. As the number of devices increases, A3’s mean and median rise faster than A0’s, suggesting that the single critic accumulates more pronounced bias and variance at scaled-up scales.

The above results demonstrate that the twin-critic network significantly enhances model convergence performance, improves stability, reduces computational complexity, and increases model efficiency.

6.5. Visualization Results

6.5.1. Utility Function Curve

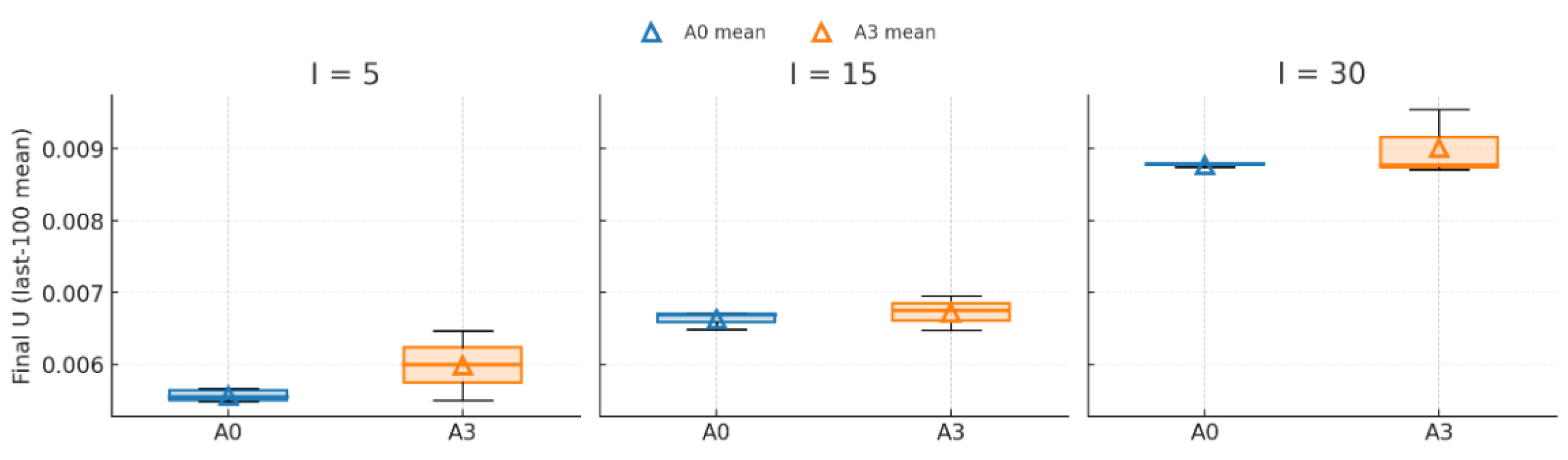

To visually demonstrate the convergence characteristics of the optimized MASAC algorithm during training, we plot the utility function U as a function of training iterations.

We reiterate the convergence curve of the utility function for the optimized model in this section, as shown in

Figure 13. The curve exhibits rapid descent during the initial phase (approximately the first few hundred episodes), completing the transition from exploration to exploitation. Subsequently, it enters a prolonged, gradual cooling phase where U fluctuates minimally around a stable interval while steadily declining, demonstrating the training process’s stability and reproducibility. The figure marks the optimal utility value throughout the process: Best U = 0.005216. The tail section where this annotation resides reveals that the optimal point is very close to multiple local minima in the vicinity. This indicates that the final performance is not an isolated point “accidentally picked up,” but rather resides in a relatively flat trough region. This implies a certain robustness to small perturbations in parameters such as learning rate and entropy temperature. Overall, the optimized model exhibits a “fast-then-stable” convergence characteristic, with U ultimately entering a plateau phase characterized by low noise and minimal drift.

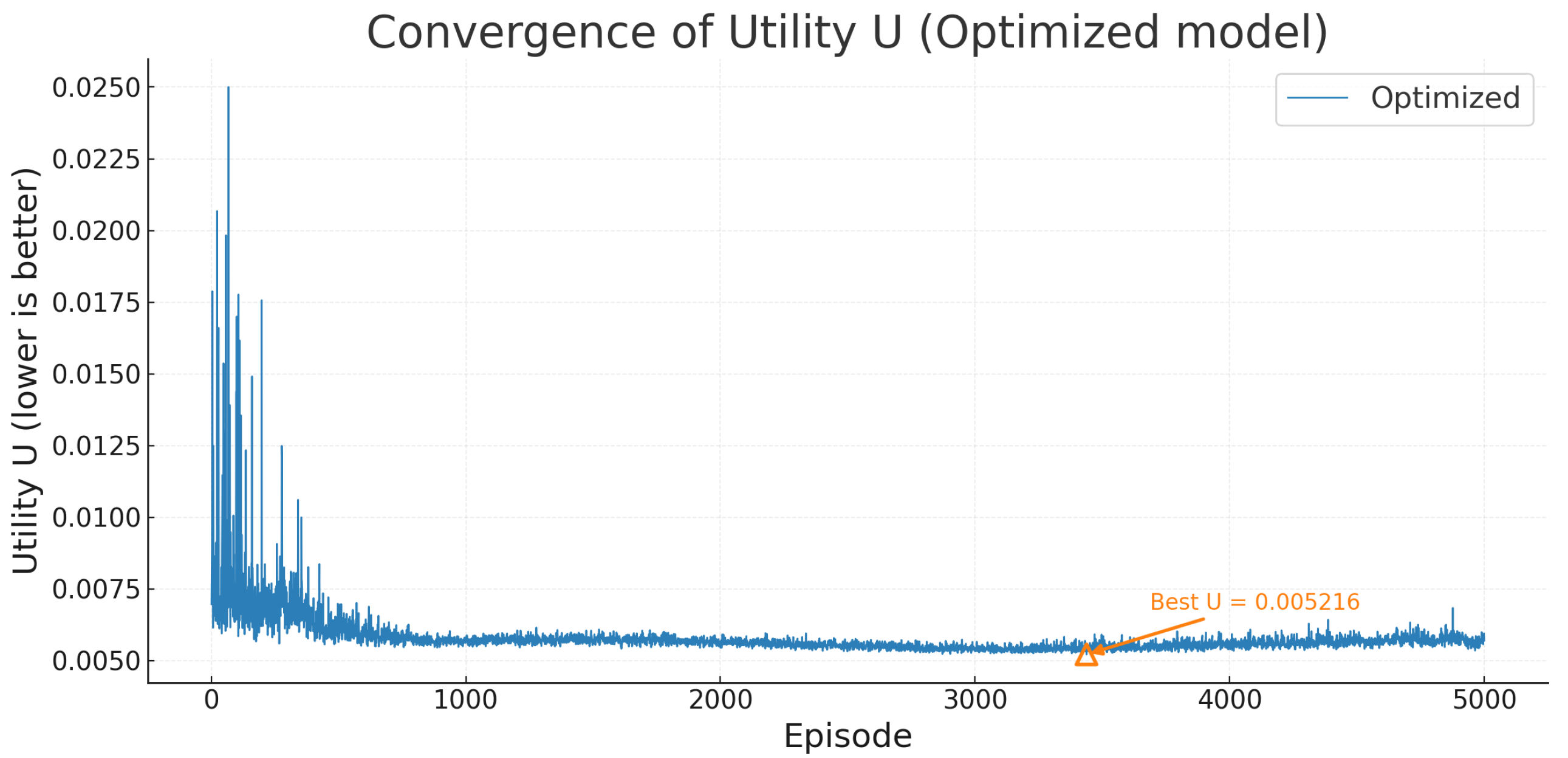

6.5.2. Scalability and Complexity Evaluation

To evaluate computational overhead across different device scales I, we measured both the per-iteration training time (end-to-end training cost) and the per-step forward latency during inference (policy inference cost only). Multiple independent measurements were conducted at each scale point, with the standard deviation plotted as error bars. Results are shown in

Figure 14.

From the training perspective (left figure), the “time per round” for both architectures increases approximately linearly with I, demonstrating good scalability. The optimized model curve generally outperforms the unoptimized model. For instance, at I = 5, it achieves approximately 0.75 ms/ep compared to 0.65 ms/ep for the unoptimized model; at I = 30, it reaches 3.71 ms/ep versus 3.36 ms/ep for the unoptimized model. The gap primarily stems from constant-term overhead introduced by shared embeddings and dual critics, yet overall remains at a low millisecond-per-epitome level. Short error bars indicate a stable and controllable training duration.

From the inference side (right figure), the per-step forward delay also increases linearly with I. At I = 5, the optimized version has a delay of approximately 0.46 ms/step, while that for the unoptimized version is 0.33 ms/step; at I = 30, these values are 2.73 ms/step and 2.23 ms/step, respectively. The latency gap gradually increases with scale but remains within the millisecond range, with minimal error fluctuations, meeting real-time decision requirements. While ensuring training and inference complexities scale linearly with size and remain controllable, the optimized model trades a slight computational overhead for faster convergence and a lower utility function U.

Overall, the optimized model maintains good scalability while incurring only a minimal constant-term overhead in training and inference complexity, achieving faster convergence and a superior utility function U.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

This work introduces several key innovations in multi-agent optimization for heterogeneous UAV swarms, summarized as follows:

Low-Complexity MASAC Framework: A low-complexity multi-agent soft actor–critic (MASAC) framework is developed under the centralized training and decentralized execution (CTDE) paradigm. It effectively mitigates the challenges of high computational complexity and long training time in UAV swarm task allocation and communication resource scheduling, achieving scalable and deployable multi-agent coordination.

Parameter Sharing and Structural Lightweighting: The proposed architecture integrates a shared actor network with device identity embeddings and a centralized twin critic featuring a shared backbone and dual Q-heads. This eliminates linear parameter growth with respect to the number of agents while maintaining strategy diversity. Combined with fixed-width MLP backbones, Layer Normalization, and residual connections, the design achieves over 14-fold parameter compression and significantly enhances training stability.

Training Stabilization and Performance Enhancement: Multiple mechanisms—piecewise entropy coefficient scheduling, reward normalization and clipping, experience replay, and delayed target networks—are incorporated to balance exploration and exploitation, suppress overestimation bias, and accelerate convergence. These mechanisms jointly achieve over a 90% reduction in training time while improving the delay–energy trade-off utility, demonstrating superior robustness and efficiency.

Building upon these innovations, this paper proposes a low-complexity multi-agent soft actor–critic method to address the challenges of high computational complexity, long training times, and deployment difficulties in heterogeneous unmanned aerial vehicle swarm task allocation and resource distribution. The approach integrates parameter sharing, lightweight network design, and a centralized training–decentralized execution framework to ensure scalability while preserving decision accuracy.

Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves more than 14-fold parameter compression and reduces training time by approximately 93%, while improving the system utility function U from 0.008431 to 0.008210. These results confirm that the method significantly lowers computational overhead and accelerates convergence without compromising optimization performance, effectively alleviating the bottlenecks of traditional multi-agent soft actor–critic in large-scale unmanned aerial vehicle clusters.

This approach shows promising applications across various unmanned aerial vehicle swarm tasks. In communication relay, it enables efficient bandwidth and power allocation for emergency links. In infrared monitoring and radar reconnaissance, it balances task partitioning to reduce single-node loads and improve real-time sensing. In navigation and spectrum monitoring, it ensures reliable operation under strict energy constraints.

Looking ahead, two directions are worth exploring: validating robustness under dynamic environments such as mobility, channel variations, and task fluctuations and integrating emerging paradigms like federated learning and meta-learning to enhance transferability and rapid adaptation. These extensions will further promote the practical deployment of low-complexity multi-agent soft actor–critic in future large-scale unmanned aerial vehicle swarm systems.

Although current experiments are conducted in high-fidelity simulations due to the lack of an available physical UAV testbed, the environment parameters are carefully designed to reflect real-world conditions. In future work, small-scale physical UAV flight experiments will be implemented to further validate the proposed algorithm’s practicality and deployment readiness. These extensions will further promote the practical deployment of low-complexity multi-agent soft actor–critic in future large-scale unmanned aerial vehicle swarm systems.