Sensitivity to Time Delays in VDM-Based Navigation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Proposed Approach

2. VDM-Based Navigation

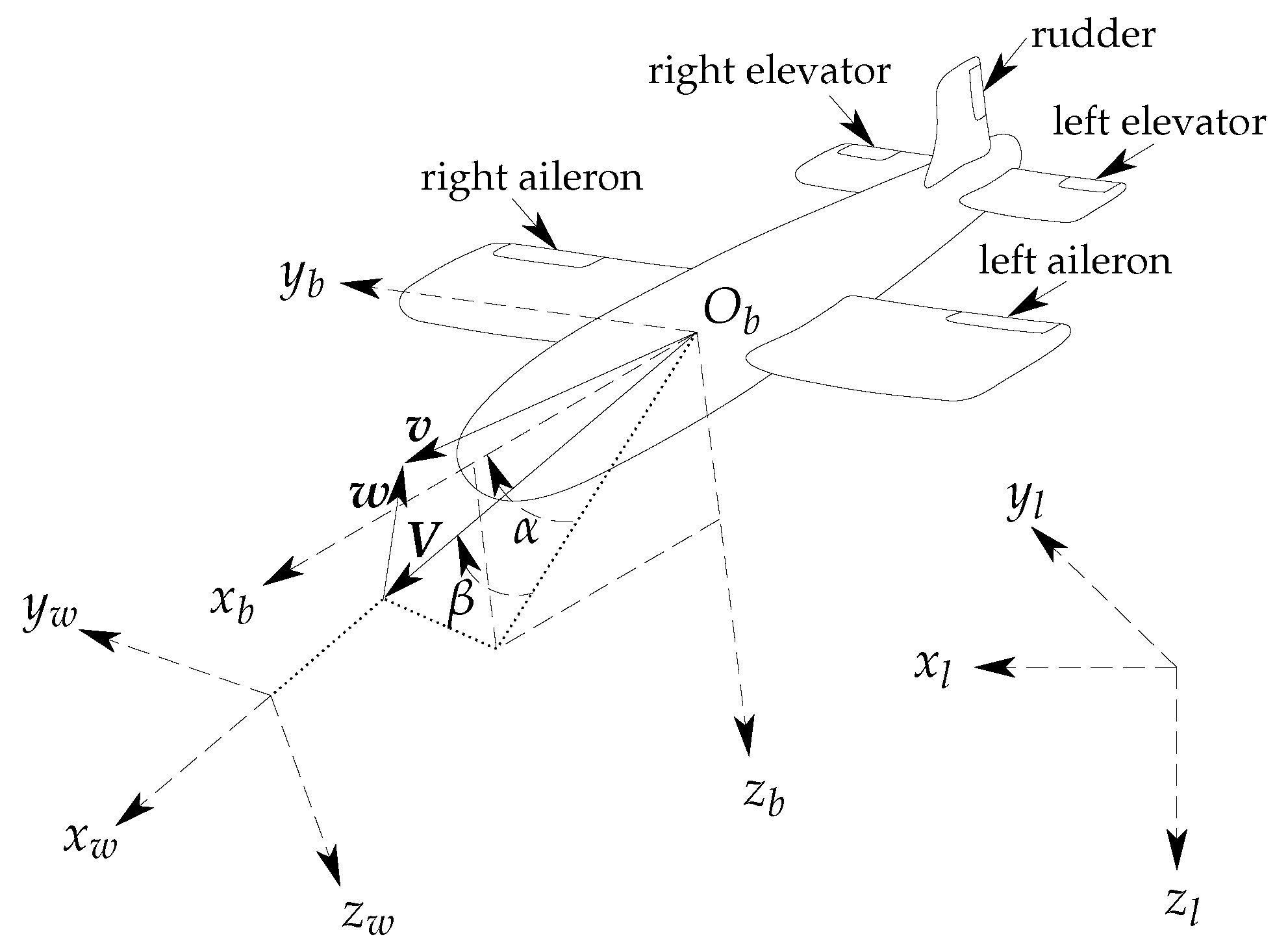

2.1. Frames Definition

2.2. Vehicle Dynamic Model (VDM)

2.3. Navigation System

3. Methodology

3.1. Reference and Flight Simulation

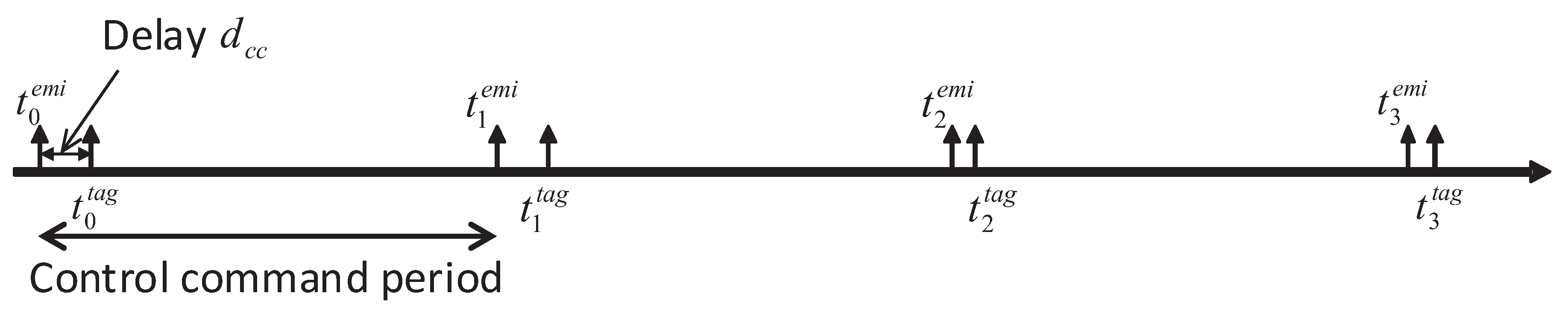

3.2. Time-Tagging Errors

3.3. VDM-Based Navigation

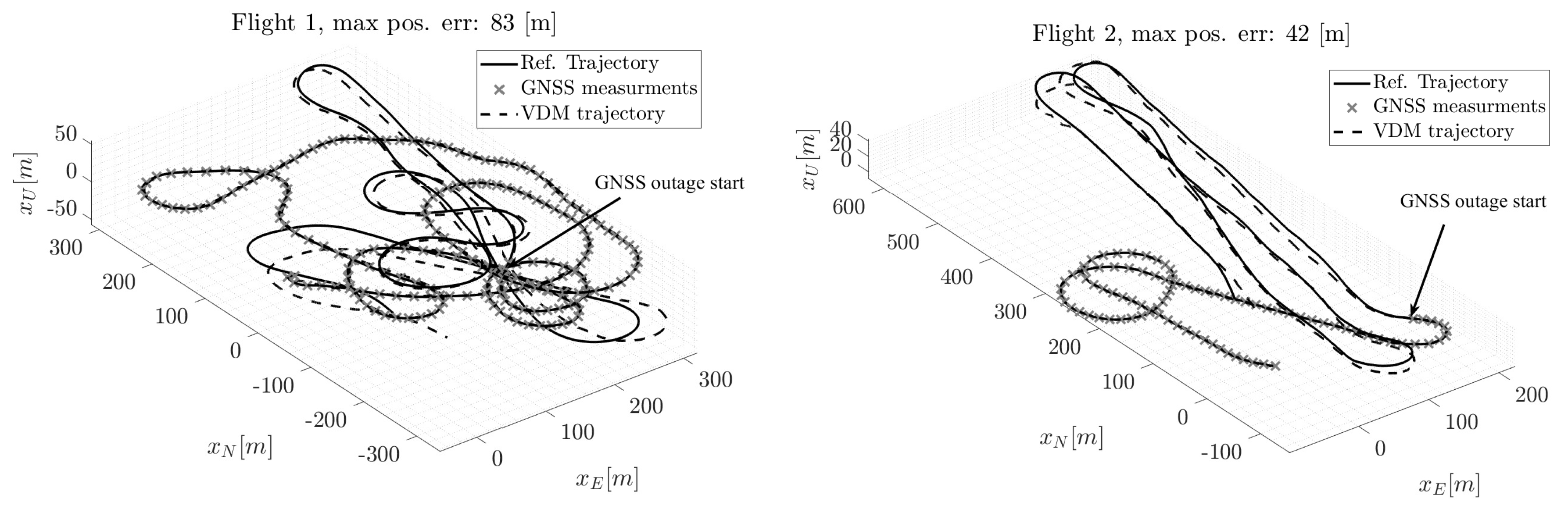

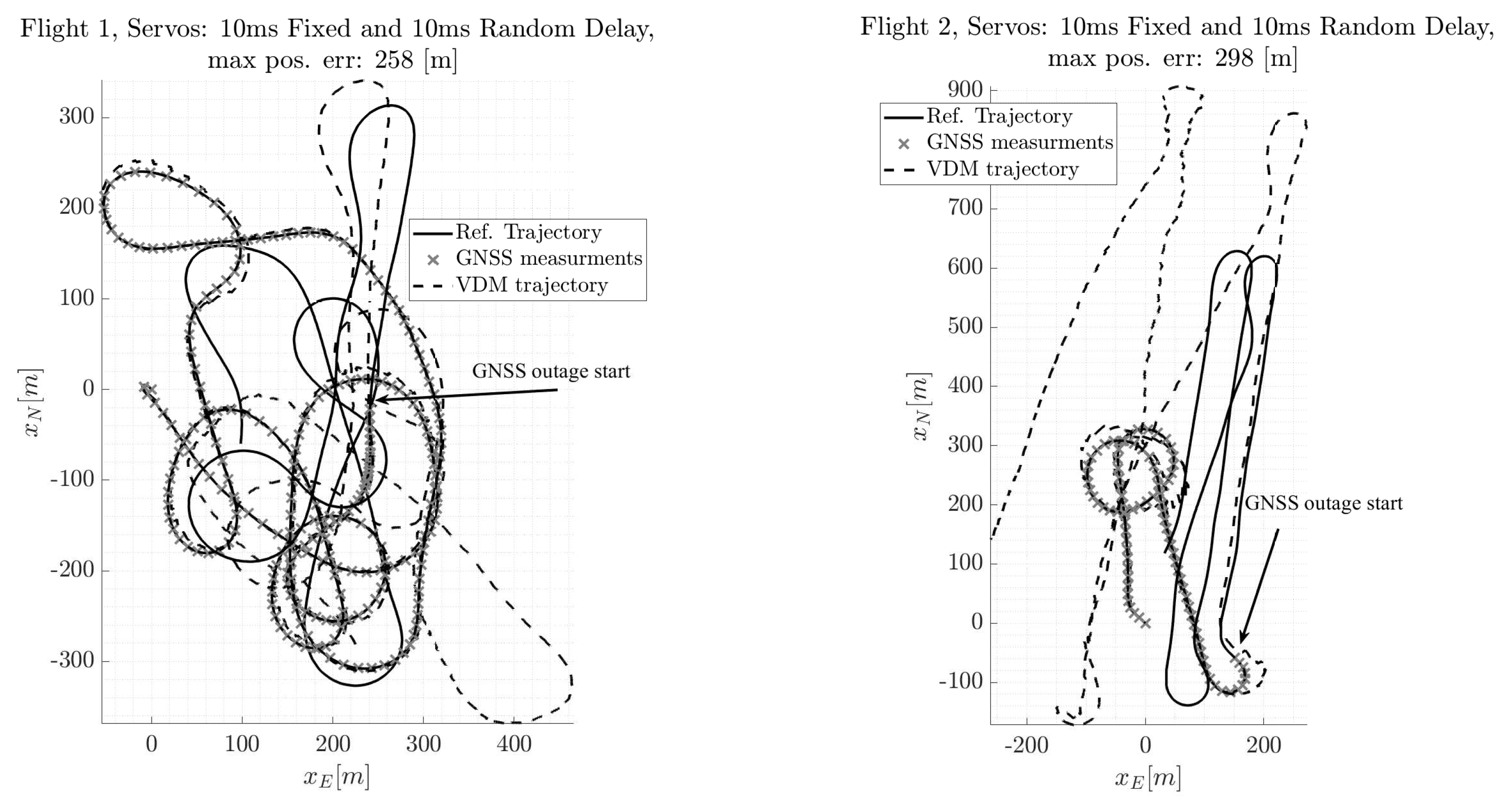

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Motor Data Time-Tagging Errors

4.2. Servos Data Time-Tagging Errors

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EKF | Extended Kalman filter |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| IMU | Inertial Measurment Unit |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| PVA | Position, Velocity and Attitude |

| RPM | Rotations Per Minute |

| PPK | Post-Processed Kinematic |

| PVT | Position, Velocity, and Time |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VDM | Vehicle Dynamic Model |

References

- Khaghani, M.; Skaloud, J. Assessment of VDM-based Autonomous Navigation of a UAV under Operational Conditions. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 106, 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Koifman, M.; Bar-Itzhack, I.Y. Inertial navigation system aided by aircraft dynamics. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 1999, 7, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cork, L.R. Aircraft Dynamic Navigation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, M.; Sukkarieh, S. UAV Localization Using Inertial Sensors and Satellite Positioning Systems. In Handbook of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 433–460. [Google Scholar]

- Crocoll, P.; Seibold, J.; Scholz, G.; Trommer, G.F. Model-Aided Navigation for a Quadrotor Helicopter: A Novel Navigation System and First Experimental Results. Navigation 2014, 61, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIMA WGS84 Update Committee. Department of Defense. World Geodetic System 1984, Its Definition and Relationships with Local Geodetic Systems, 3rd ed.; Technical Report; National Imagery and Mapping Agency: Springfield, VA, USA, 2000.

- Stebler, Y. Modeling and Processing Approaches for Integrated Inertial Navigation. Ph.D. Thesis, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ducard, G. Fault-Tolerant Flight Control and Guidance Systems: Practical Methods for Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, A. (Ed.) Applied Optimal Estimation; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Khaghani, M.; Skaloud, J. Evaluation of Wind Effects on UAV Autonomous Navigation Based on Vehicle Dynamic Model. In Proceedings of the 29th International Technical Meeting of The Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2016), Portland, OR, USA, 12–16 September 2016; pp. 1432–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, L.; Tanskanen, P.; Heng, L.; Lee, G.H.; Fraundorfer, F.; Pollefeys, M. PIXHAWK: A Micro Aerial Vehicle Design for Autonomous Flight using Onboard Computer Vision. Auton. Robots 2012, 33, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intersense. Navchip. Available online: http://www.intersense.com/pages/16/246 (accessed on 10 December 2015).

- Guerrier, S.; Skaloud, J.; Stebler, Y.; Victoria-Feser, M.P. Wavelet-Variance-based Estimation for Composite Stochastic Processes. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2013, 108, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Sensor | Error Type | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelero-meters | Bias | 8 | mg | |

| White Noise | 67 | g/ | ||

| 1st order Gauss–Markov | 0.15 | mg | ||

| T | 200 | s | ||

| Gyro-scopes | Bias | 720 | /h | |

| White Noise | 0.005 | |||

| 1st order Gauss–Markov | 31 | /h | ||

| T | 200 | s |

| Fixed Delays [ms] | Random Delays [ms] |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 10 |

| 50 | 20 |

| 100 | 50 |

| 200 | 100 |

| 300 | ∅ |

| Fixed Delays [ms] | Random Delays [ms] |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 5 |

| 10 | 10 |

| 15 | 15 |

| 20 | 20 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laupré, G.; Khaghani, M.; Skaloud, J. Sensitivity to Time Delays in VDM-Based Navigation. Drones 2019, 3, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones3010011

Laupré G, Khaghani M, Skaloud J. Sensitivity to Time Delays in VDM-Based Navigation. Drones. 2019; 3(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones3010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaupré, Gabriel, Mehran Khaghani, and Jan Skaloud. 2019. "Sensitivity to Time Delays in VDM-Based Navigation" Drones 3, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones3010011

APA StyleLaupré, G., Khaghani, M., & Skaloud, J. (2019). Sensitivity to Time Delays in VDM-Based Navigation. Drones, 3(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones3010011