Propeller Design Within the Overall Configuration of a Near-Space Airship

Highlights

- In the overall configuration design of a near-space airship, propeller efficiency improvement only has a limited effect on overall weight reduction.

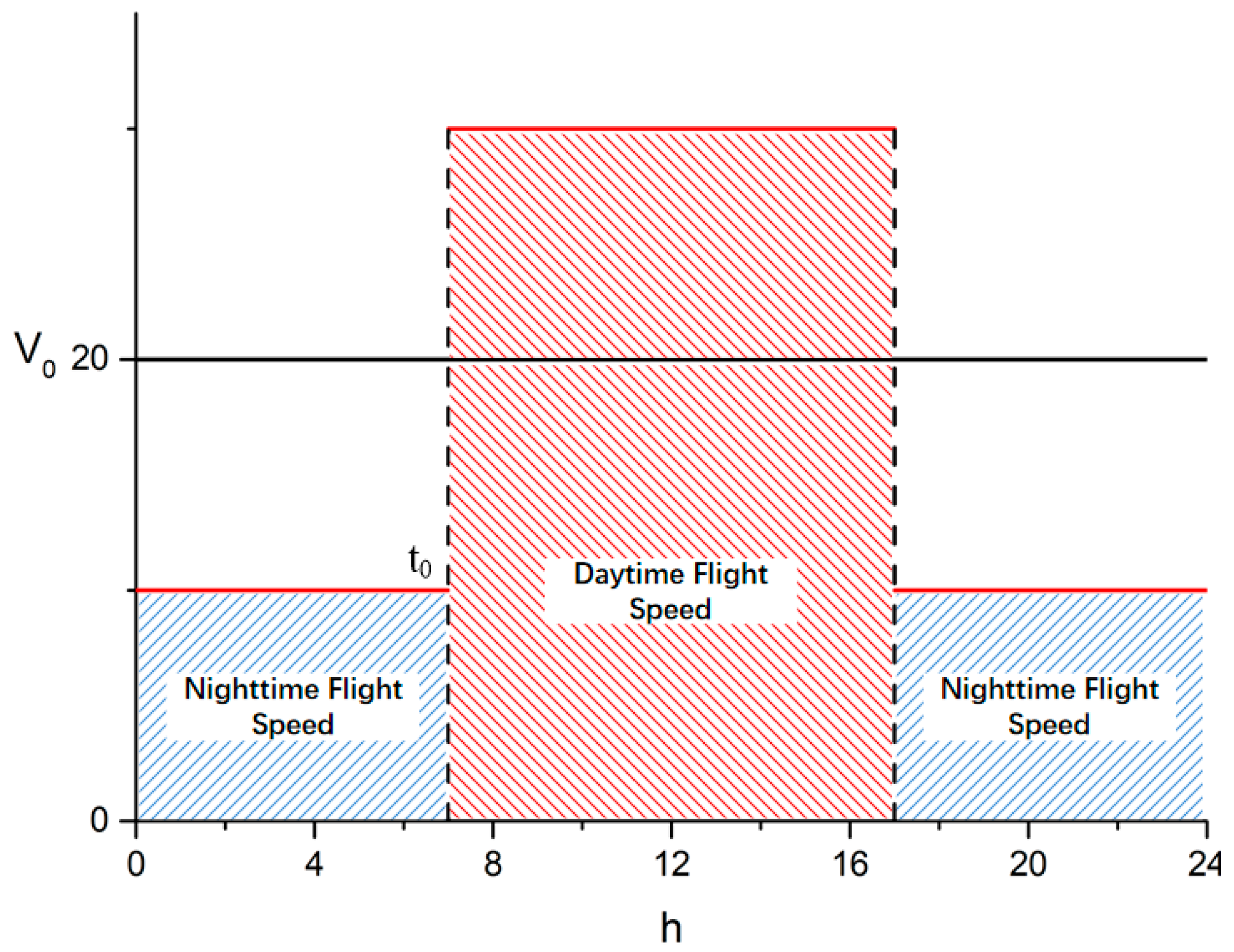

- A differentiated daytime–nighttime flight speed is introduced to significantly reduce the nighttime energy demand, enabling up to a 29.6% reduction in total airship mass.

- An engineering method based on characteristic blade elements can provide a propeller adequately optimized for airship overall configuration design.

- The variable-speed strategy offers an effective pathway for the lightweight design of near-space airships, enhancing feasibility for long-endurance station-keeping missions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Significance

1.2. Research Background

1.2.1. Near-Space Propellers

1.2.2. Overall Design Methods of Near-Space Airships

2. Propeller Design Methods

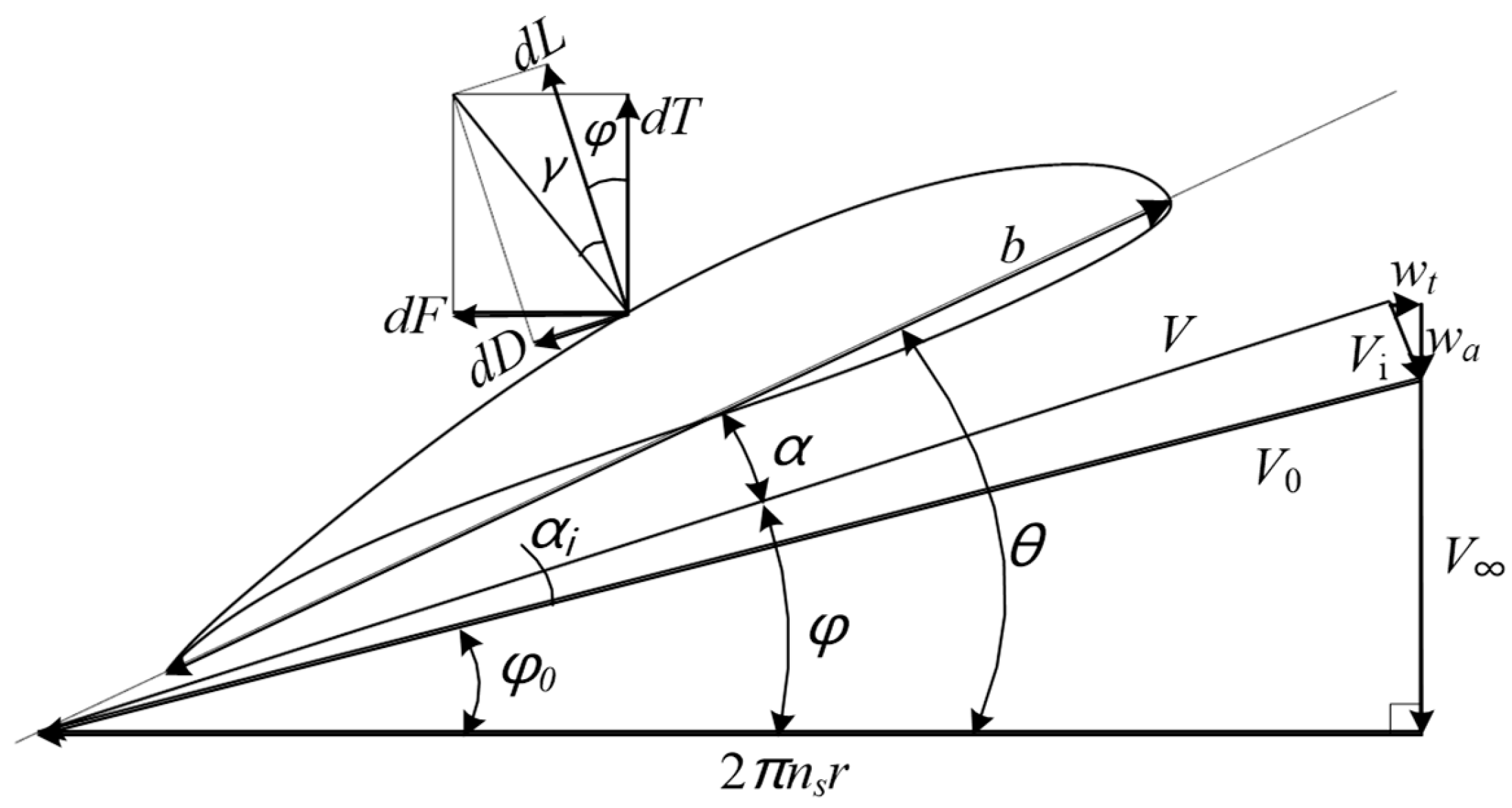

2.1. Propeller Performance Prediction Based on Blade Element Momentum Theory

2.2. Propeller Performance Prediction Based on Characteristic Blade Element

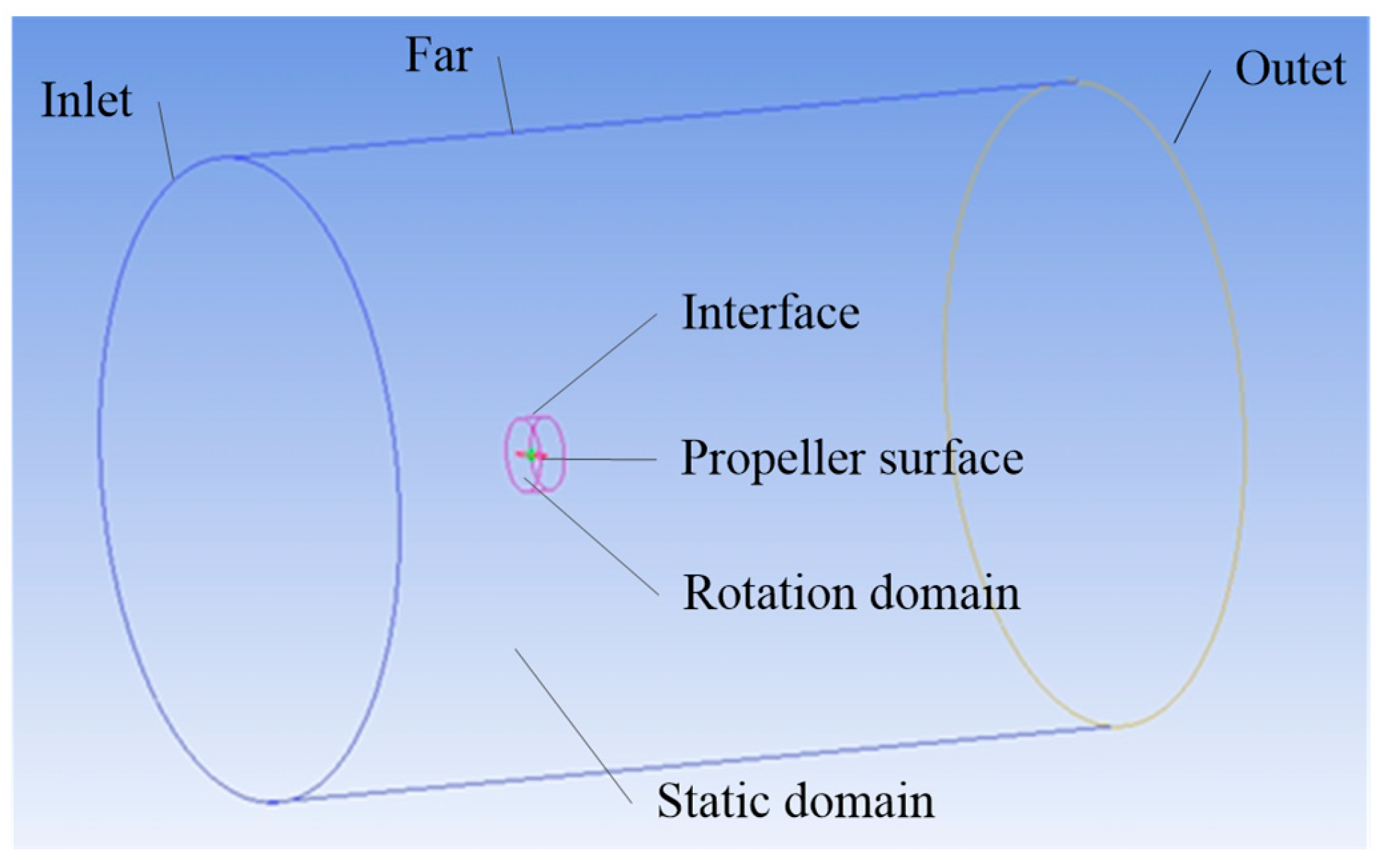

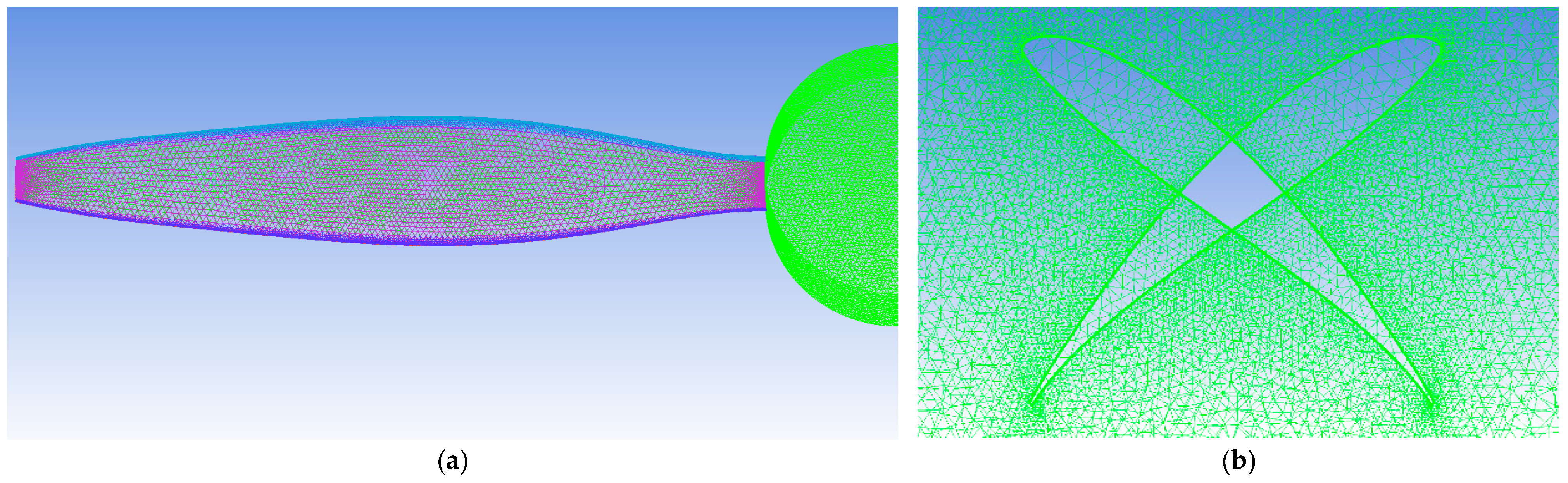

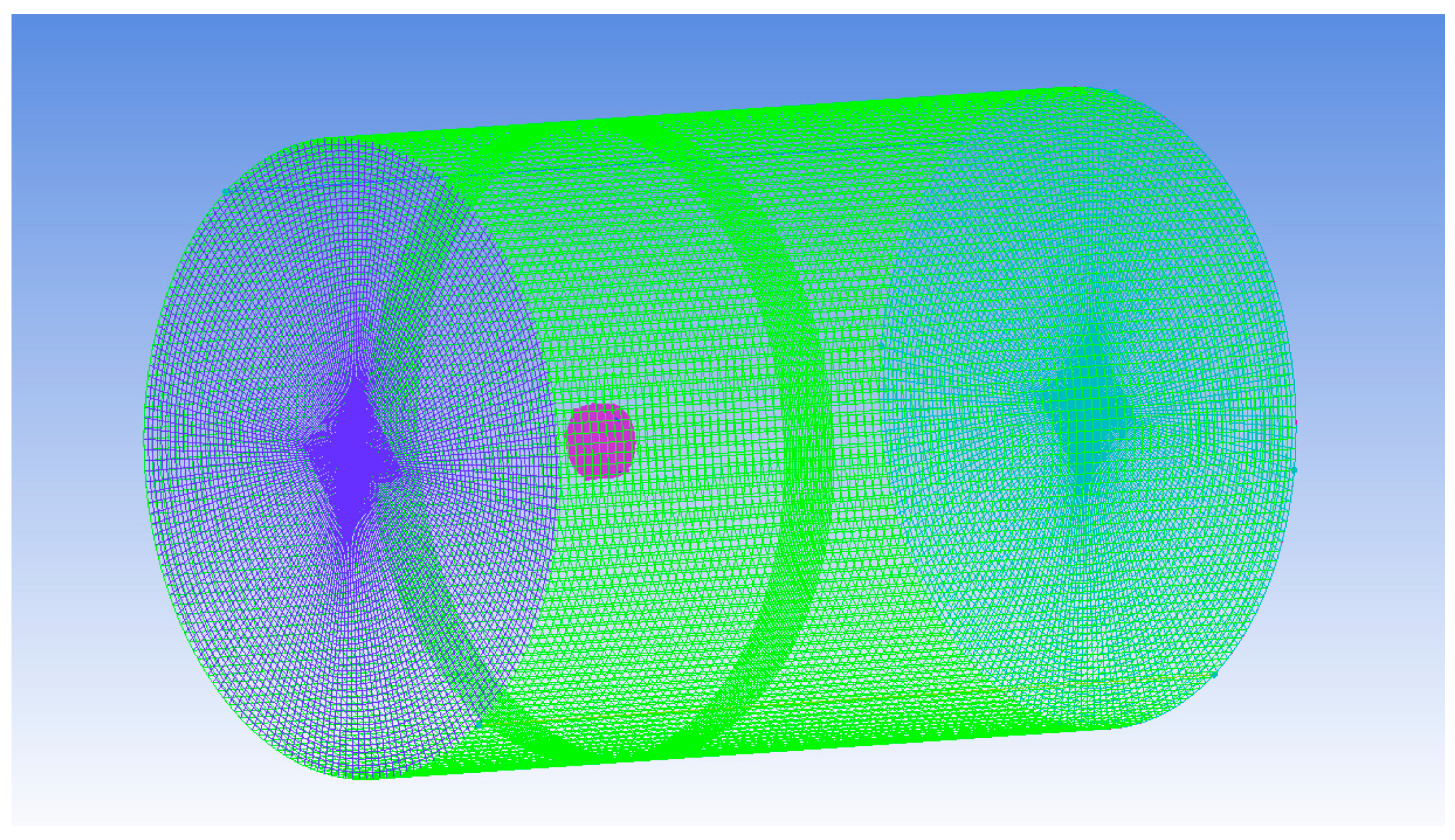

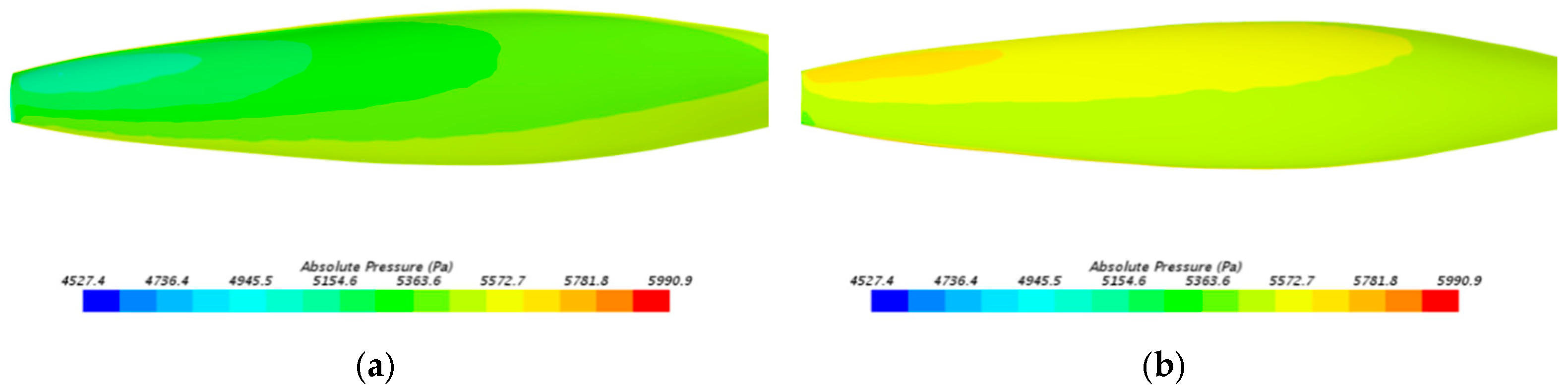

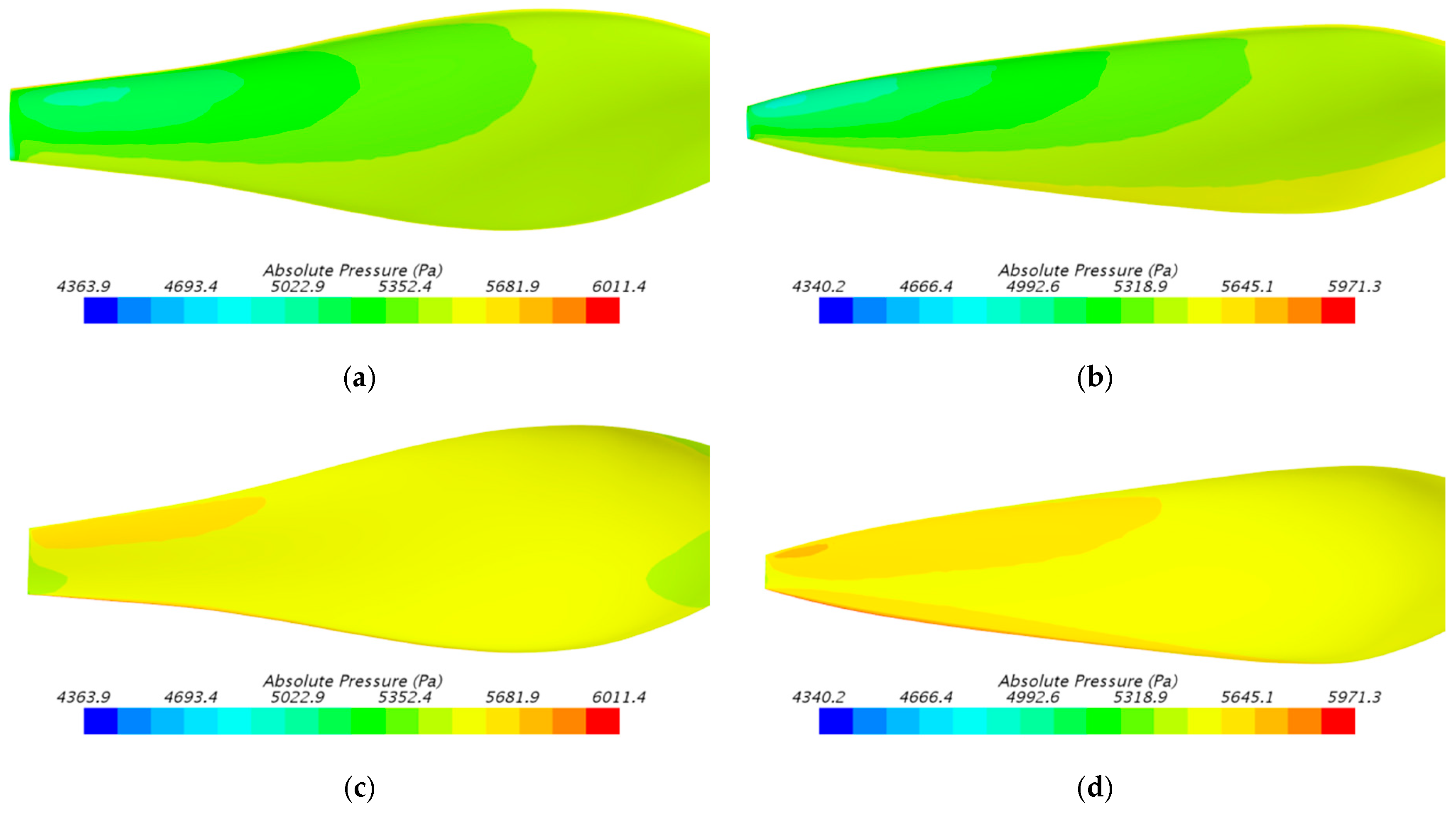

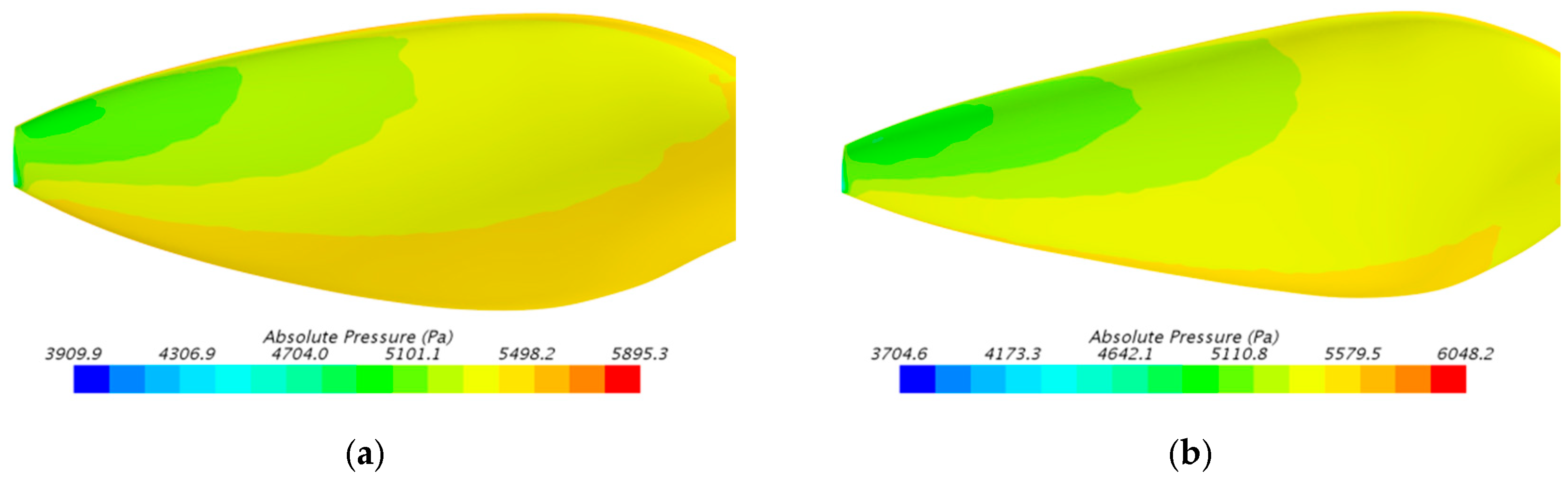

2.3. Propeller Performance Verification with CFD

2.4. Particle Swarm Optimization

- Firstly, initialize the parameters such as the particle swarm size , iteration count , inertia factor , local acceleration factor , and global acceleration factor ;

- Randomly generate the position and velocity of individual particles within the feasible region;

- 3.

- Input the current position as the optimal position of the individual particle, , and calculate the fitness of the individual particle. Compare the fitnesses to obtain the global optimal position, ;

- 4.

- Calculate the velocity and position information of individual particles, and adjust them based on possible velocity and position constraints;

- 5.

- Determine the optimal position of individual particles, denoted as , and calculate the fitness of each particle. Based on the comparison of fitnesses, obtain the global optimal position, denoted as ;

- 6.

- Repeat steps 4 and 5. If the result meets the requirements, stop calculating and output the result.

2.5. The Single-Objective Optimization Method for Propeller Design

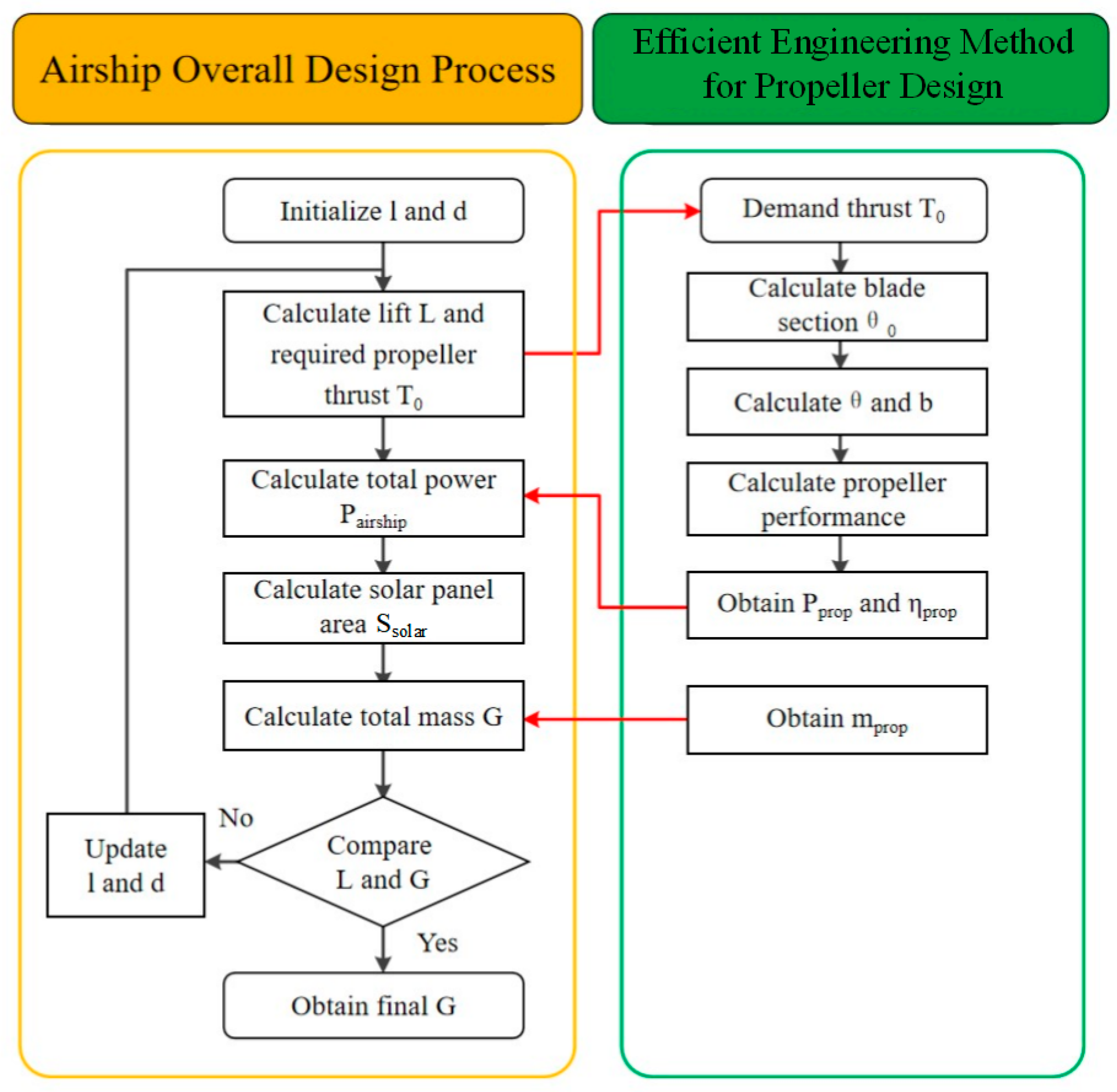

2.6. Efficient Engineering Method for Propeller Design

3. Overall Design Method for Near-Space Airships

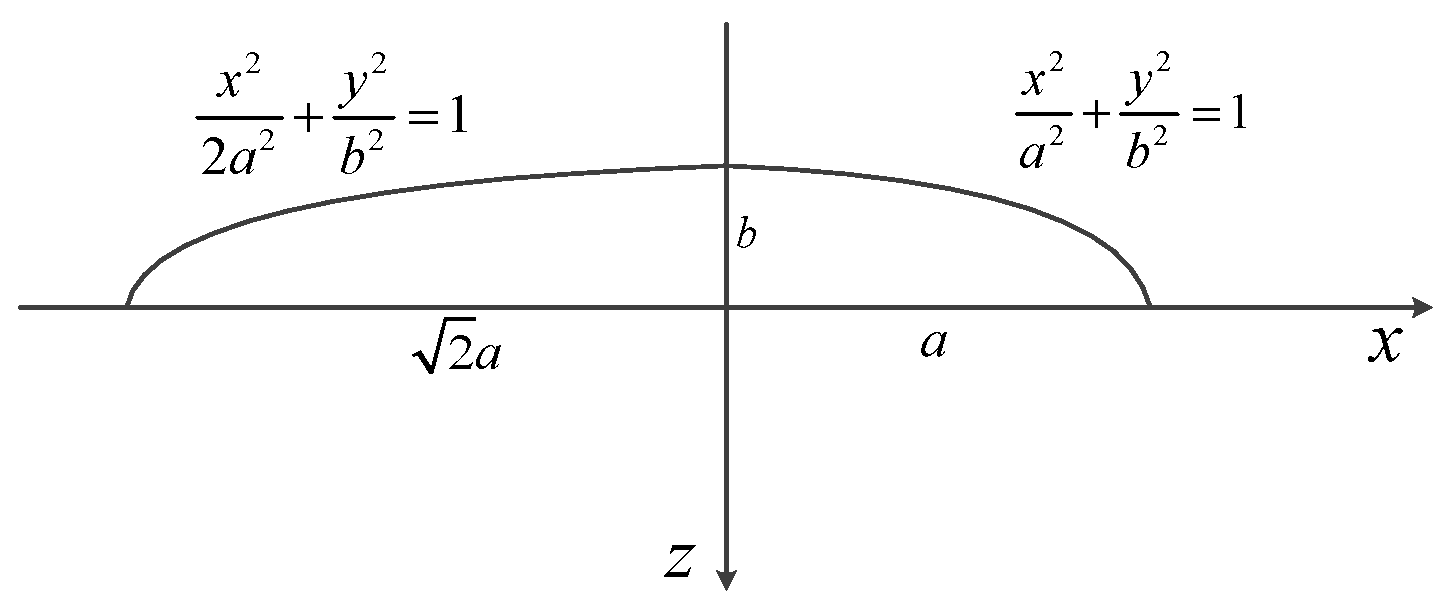

3.1. Airship Geometric Parameters

3.2. Thrust–Drag Equilibrium Equation

- 7.

- Airship Drag

- 8.

- Airship Thrust

- 9.

- Thrust–Drag Equilibrium

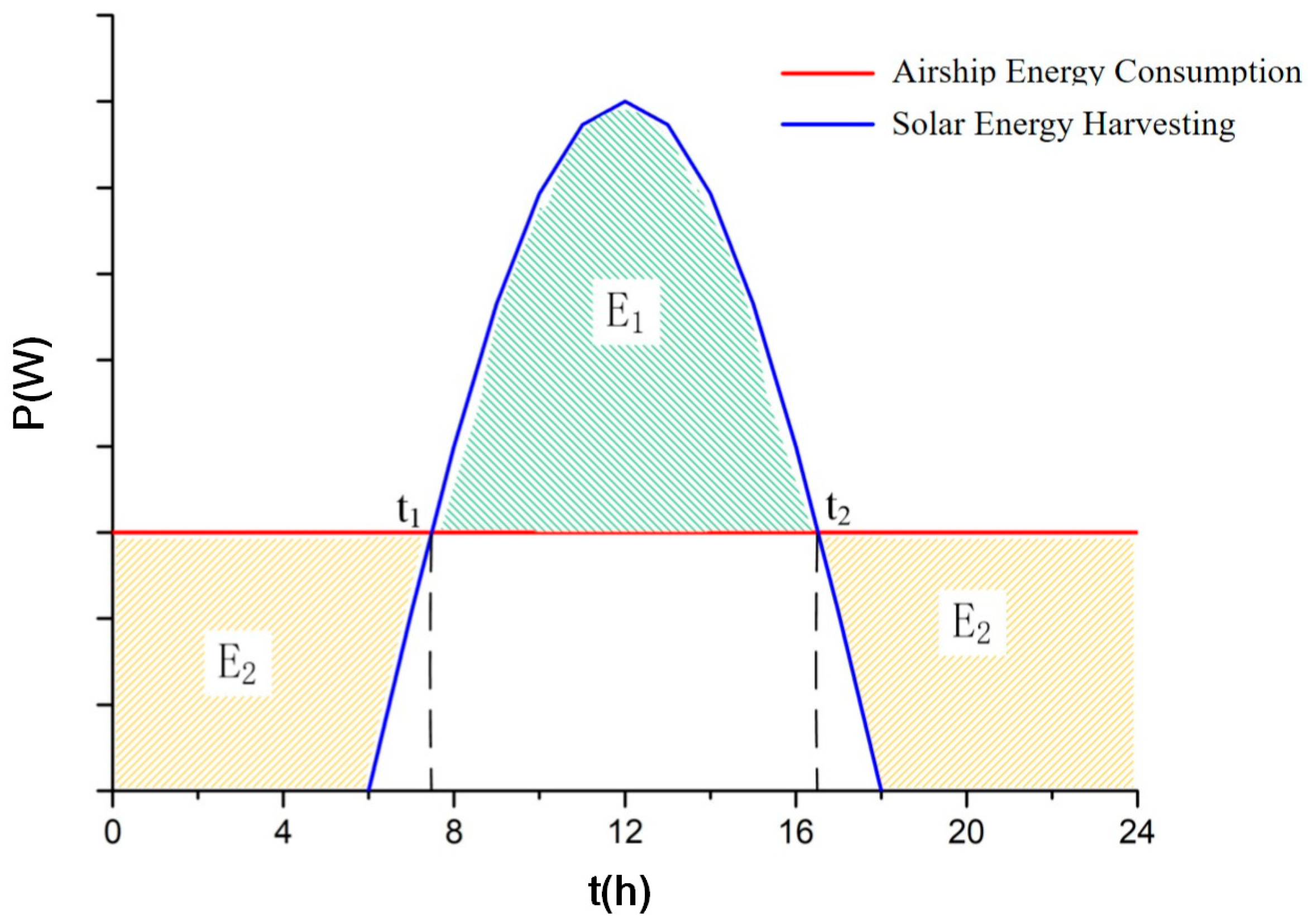

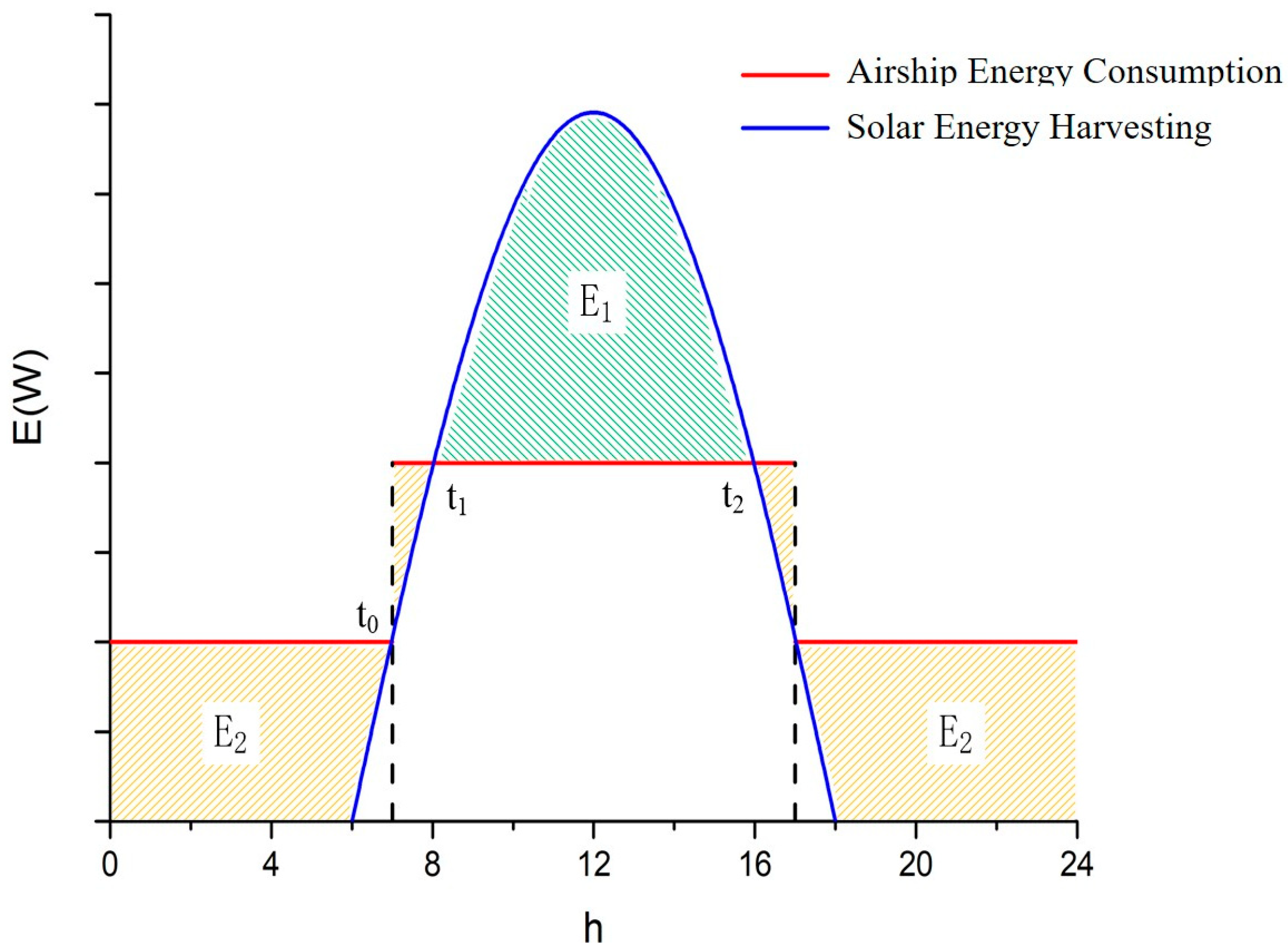

3.3. Energy Equilibrium Equation

- Airship Operating Power

- 2.

- Solar Power Acquisition

- 3.

- Energy Equilibrium and Battery Capacity

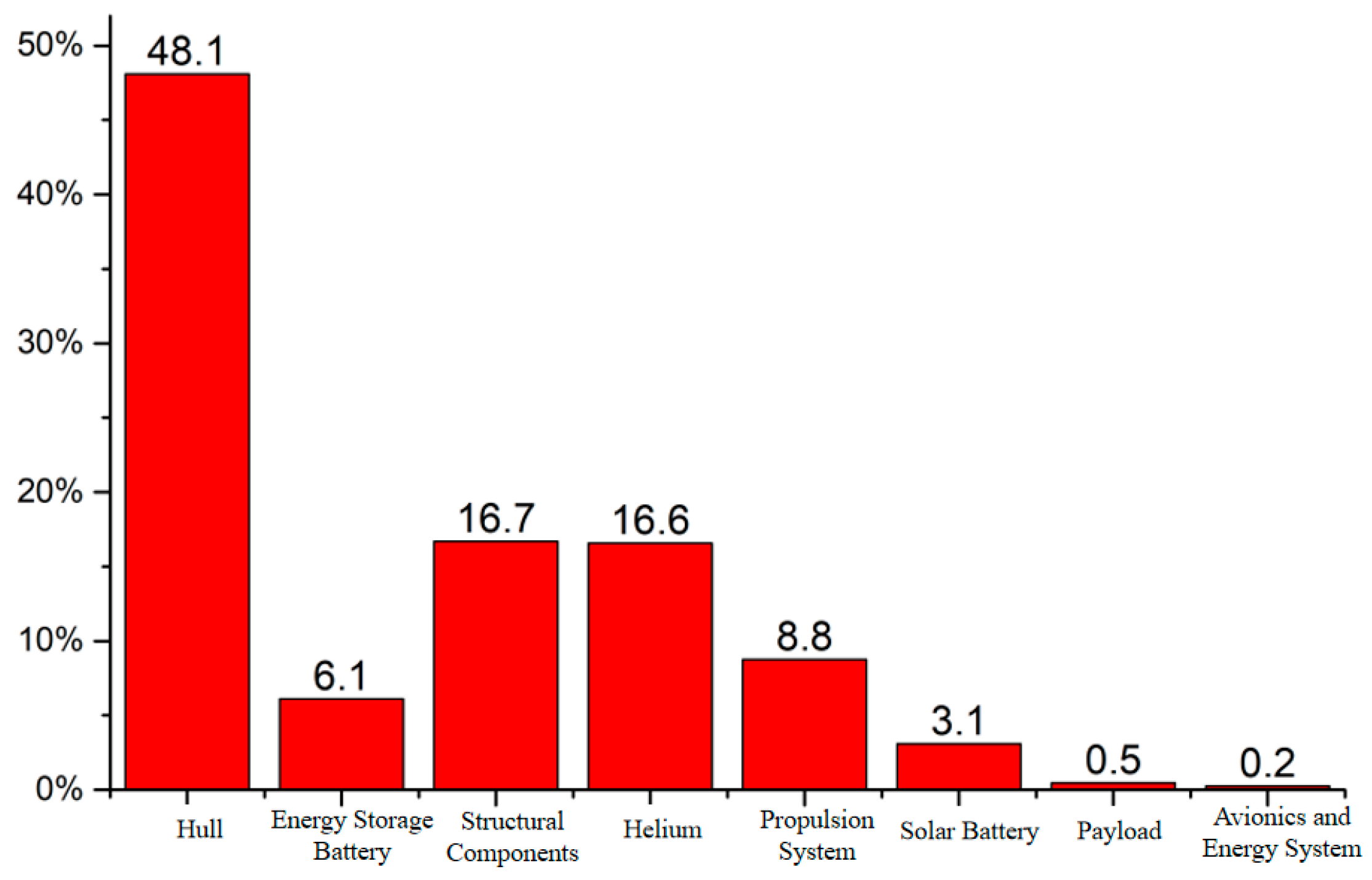

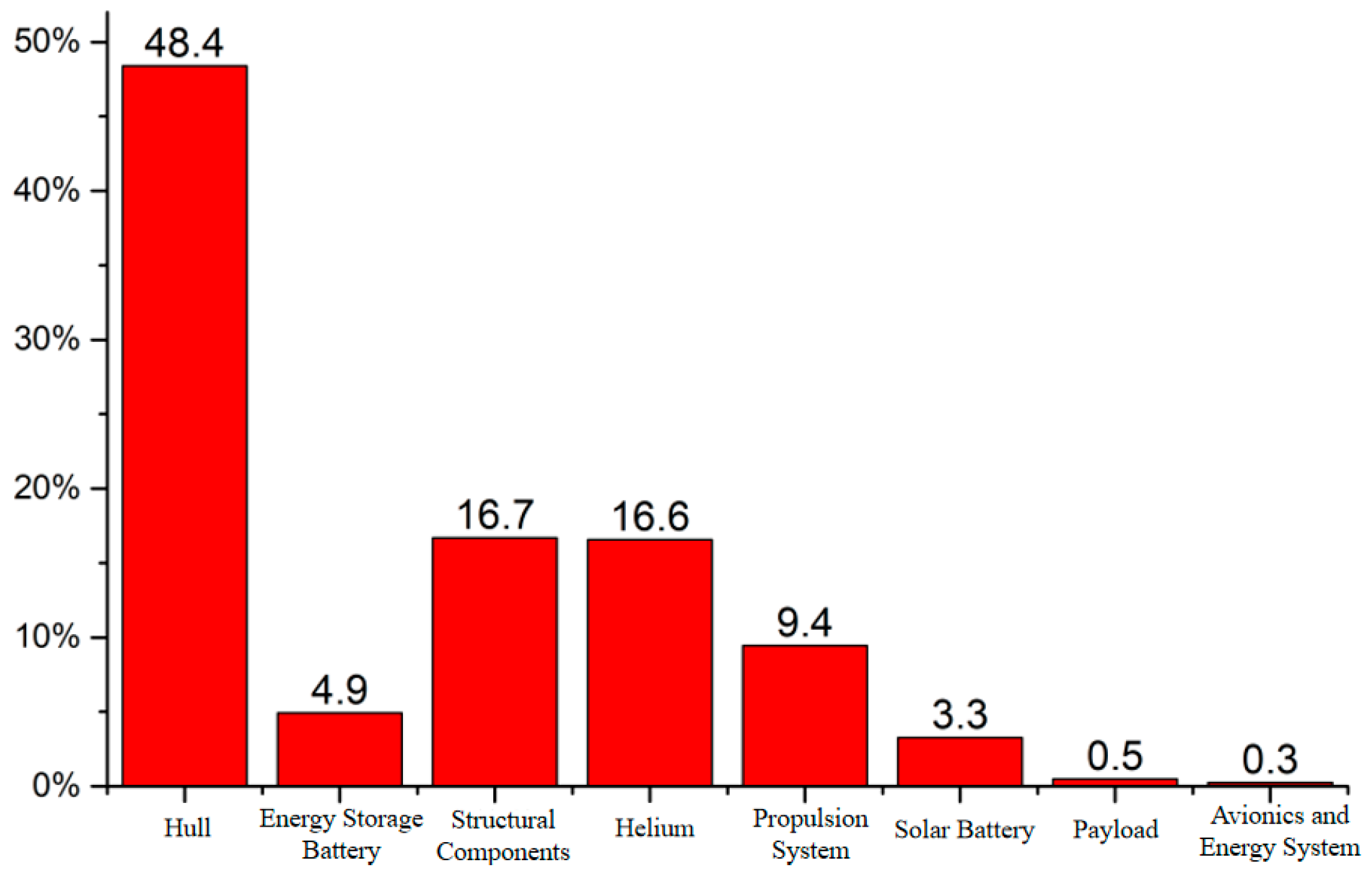

3.4. Buoyancy–Weight Equilibrium Equation

- Airship Total Buoyancy

- 2.

- Helium Mass

- 3.

- Envelope Mass

- 4.

- Propulsion System Mass

- 5.

- Energy System Mass

- 6.

- Structural Mass

- 7.

- Total Airship Mass

- 8.

- Buoyancy–Weight Balance

3.5. Airship Design Process

4. Propeller Design in the Overall Airship Configuration

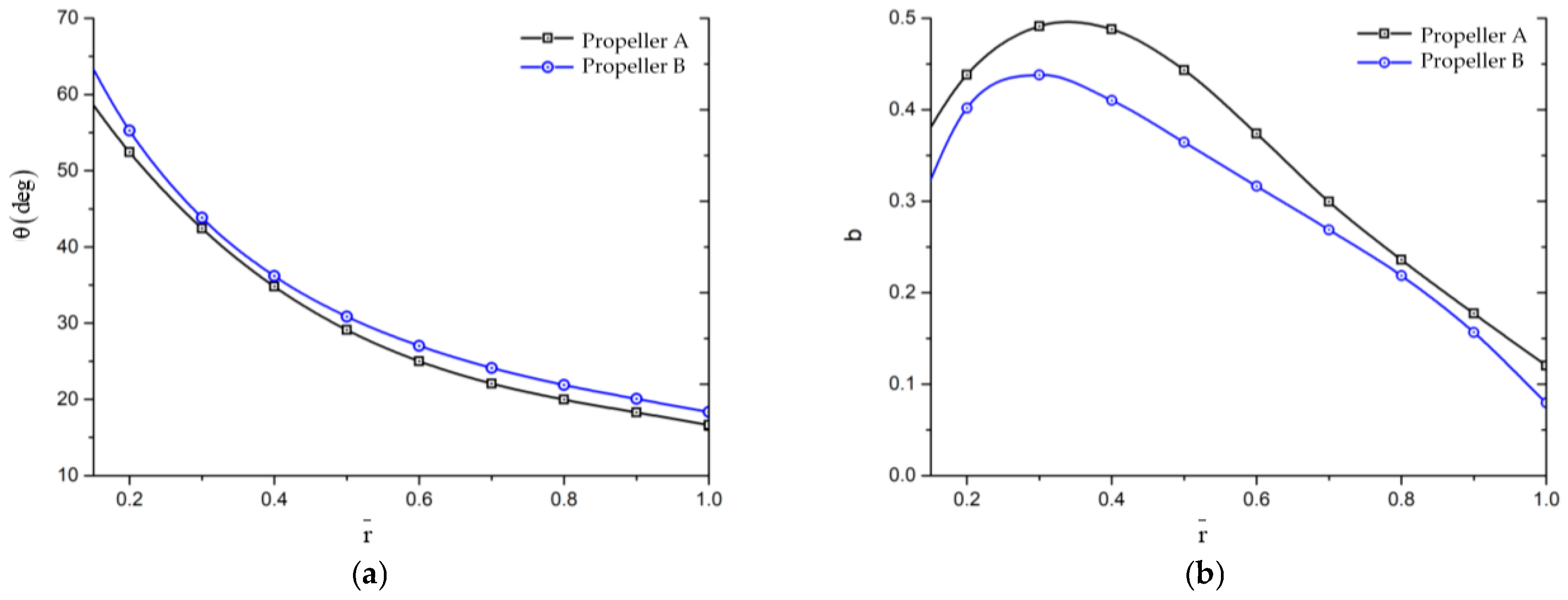

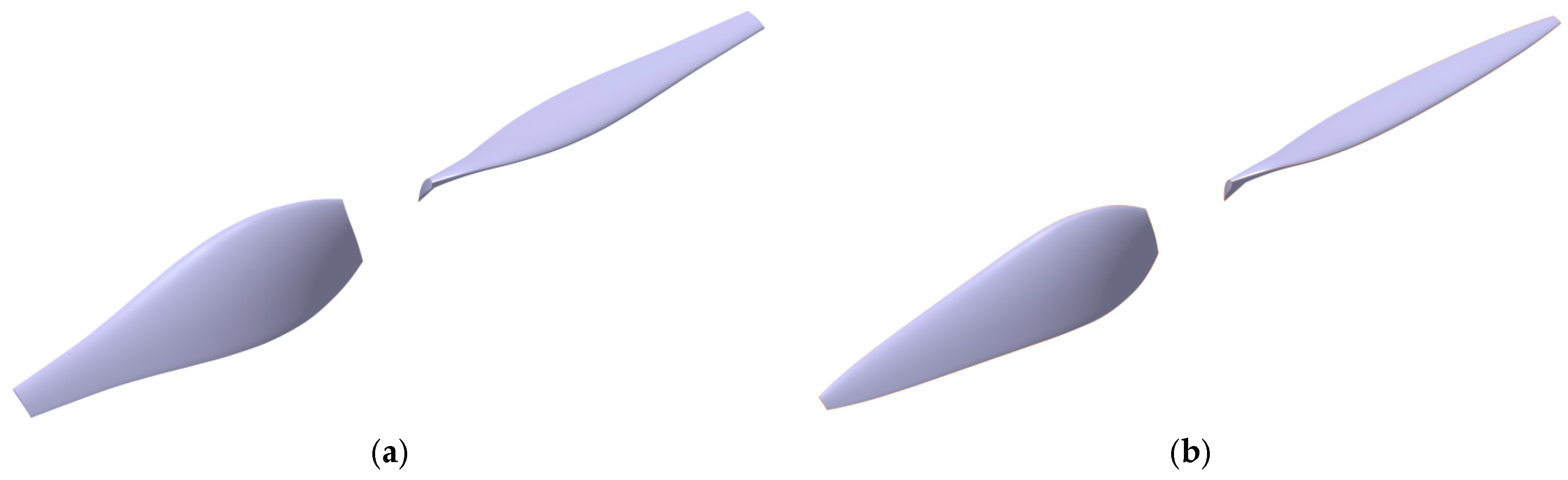

4.1. Comparison of Propeller Design Results Obtained by Different Optimization Methods

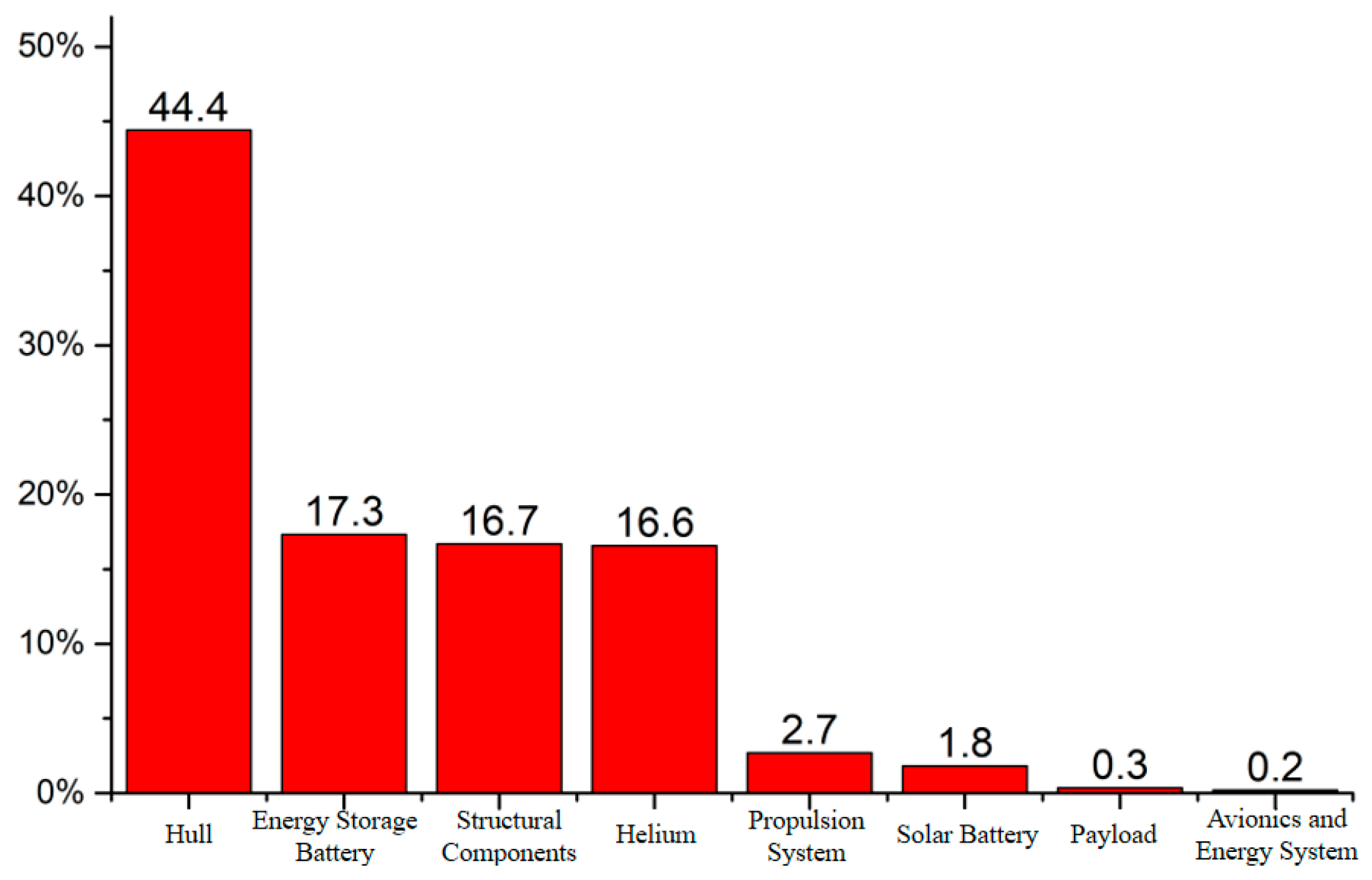

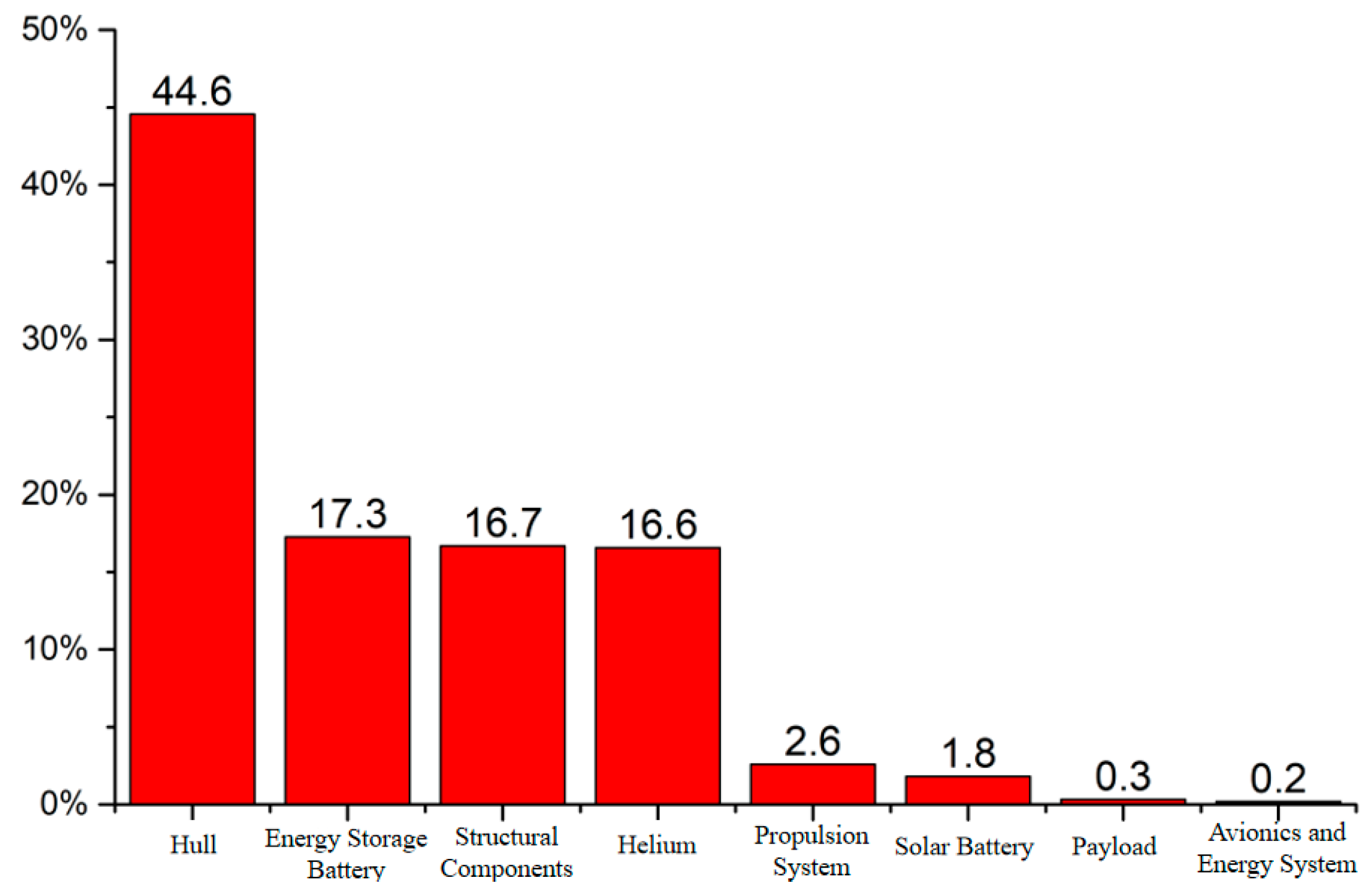

4.2. Comparison of Overall Airship Configurations Obtained Using Different Propeller Designs

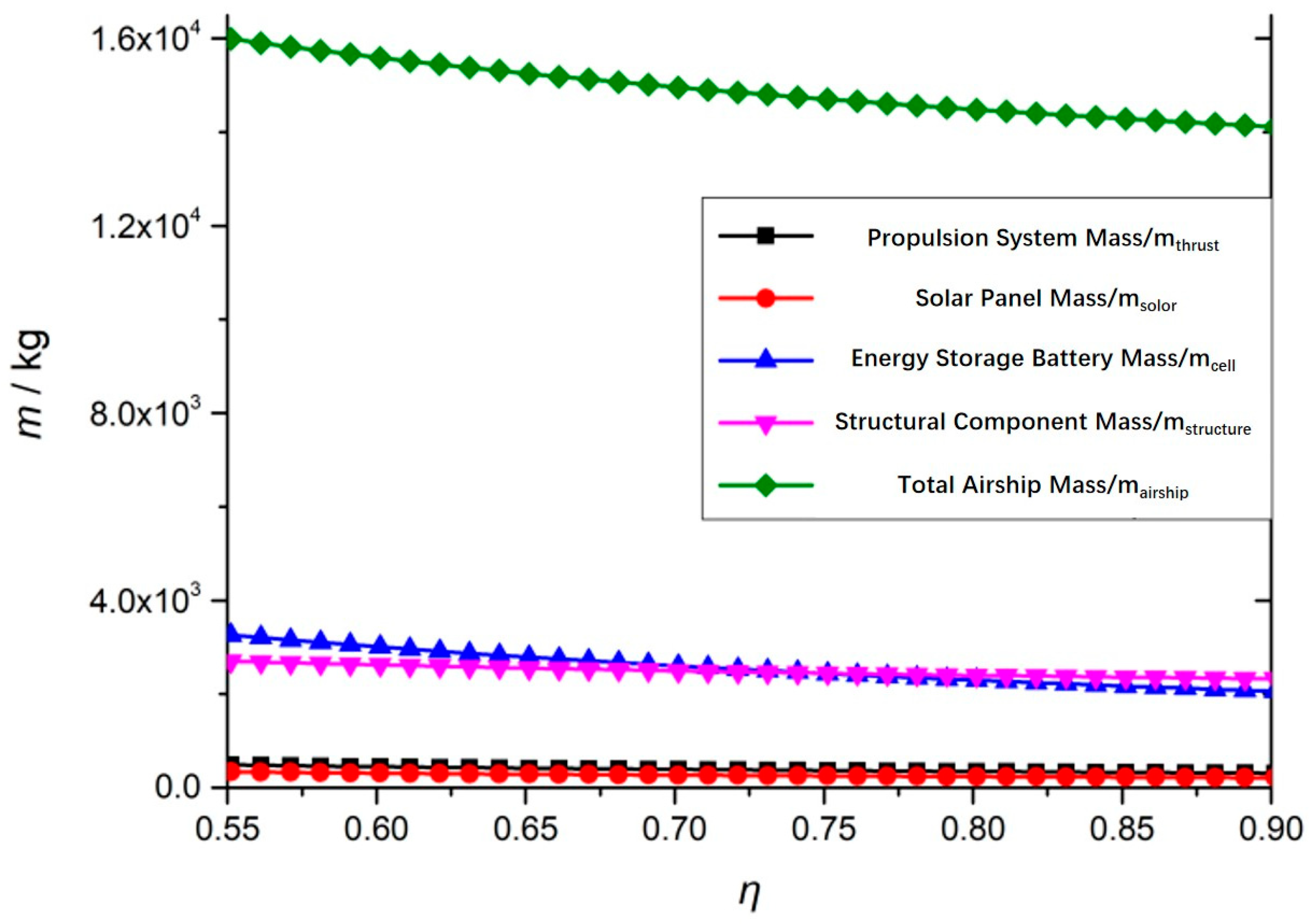

4.3. Influence of Propeller Performance on the Overall Airship Configuration

5. Propeller Design Considering Different Daytime and Nighttime Flight Speeds

5.1. Overall Configuration with Different Daytime and Nighttime Flight Speeds

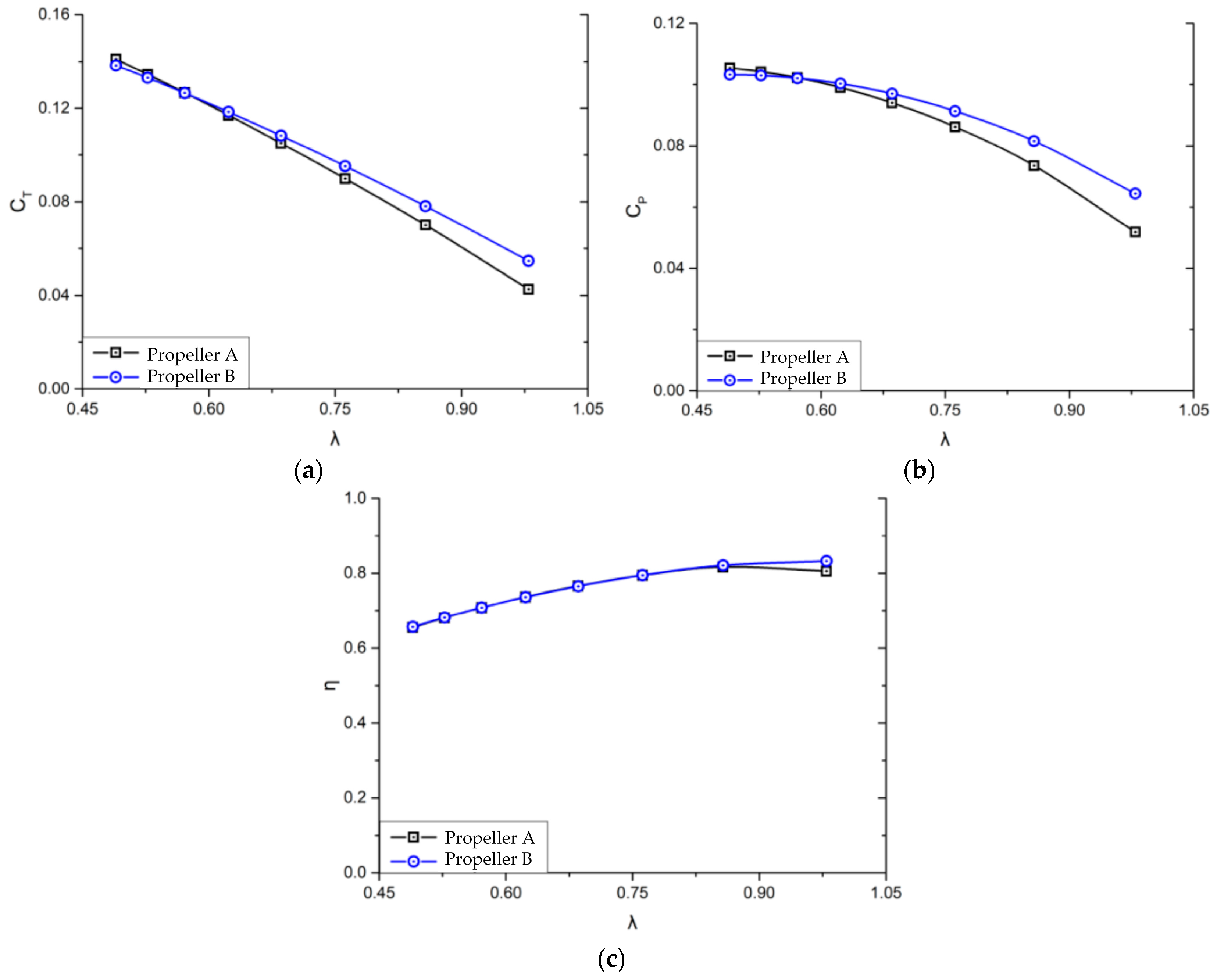

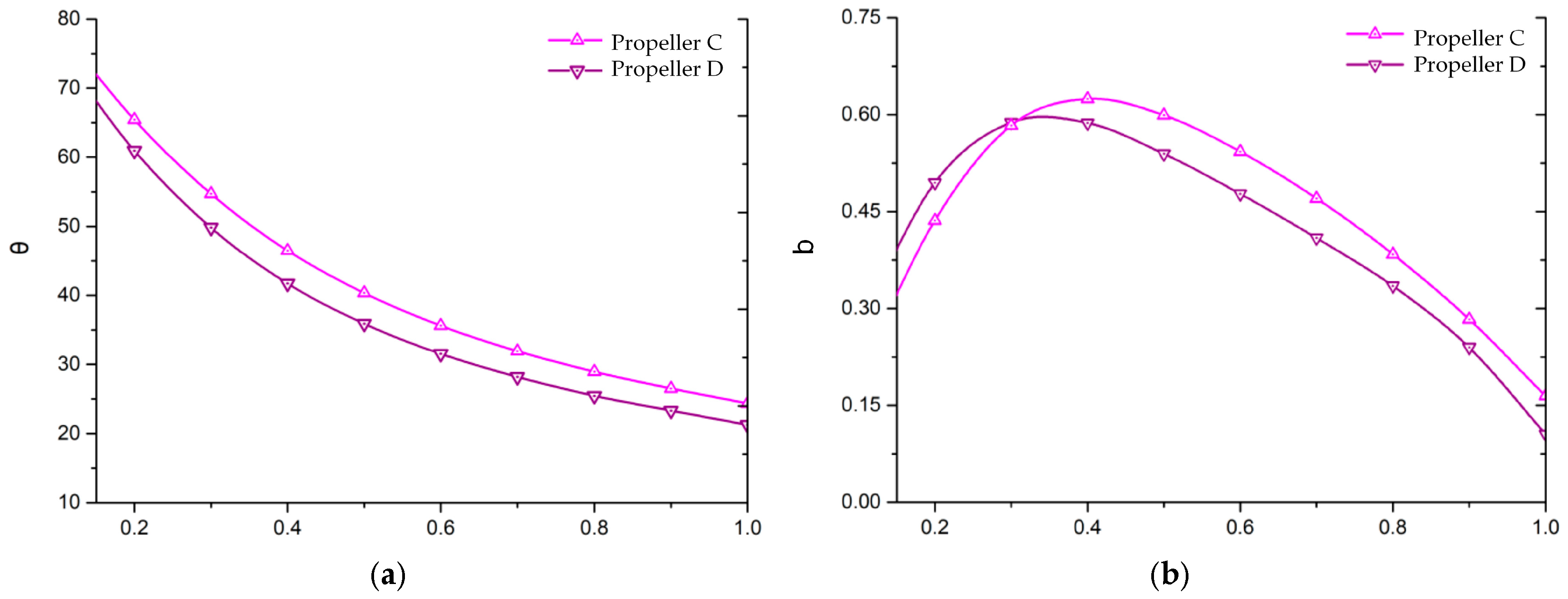

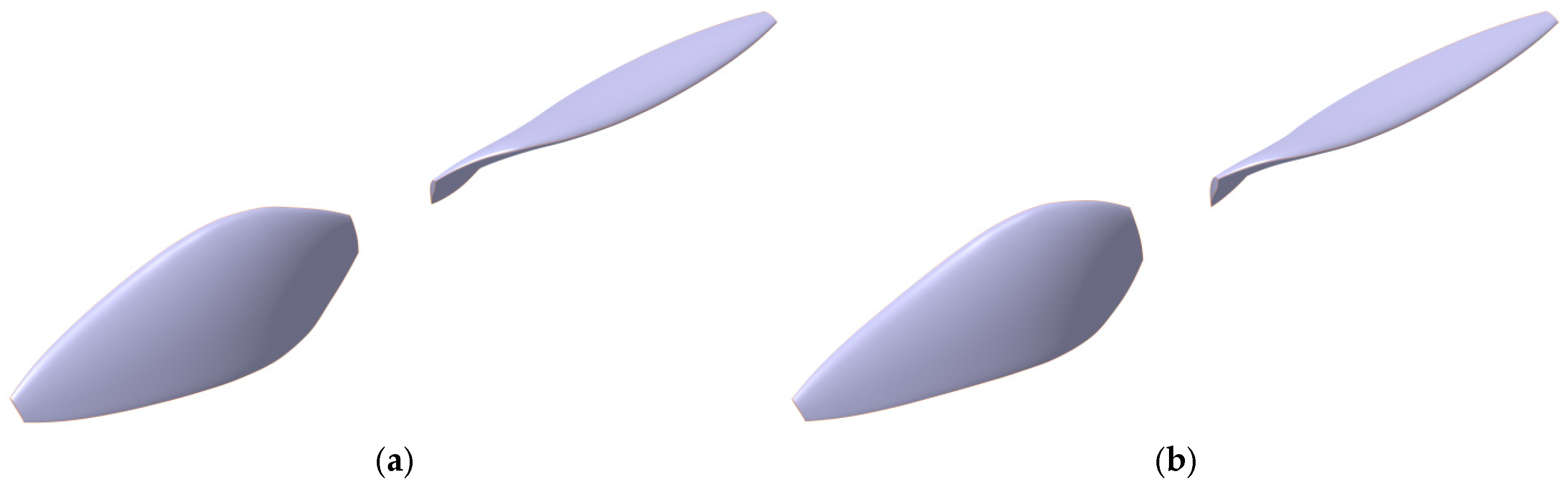

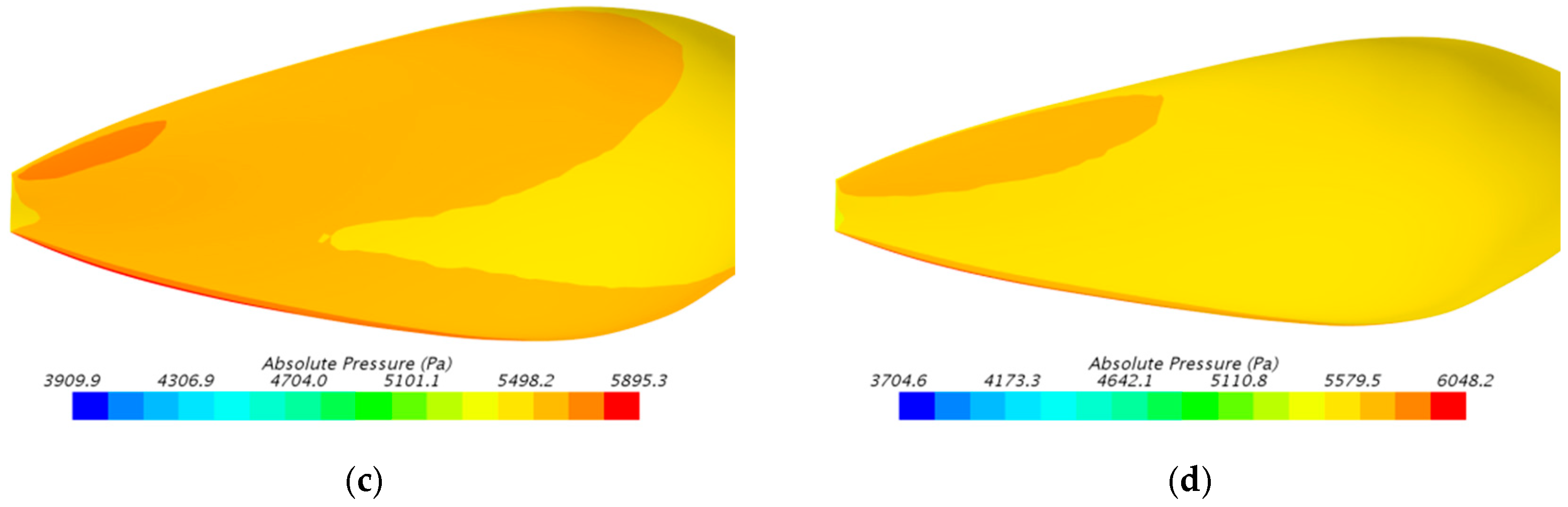

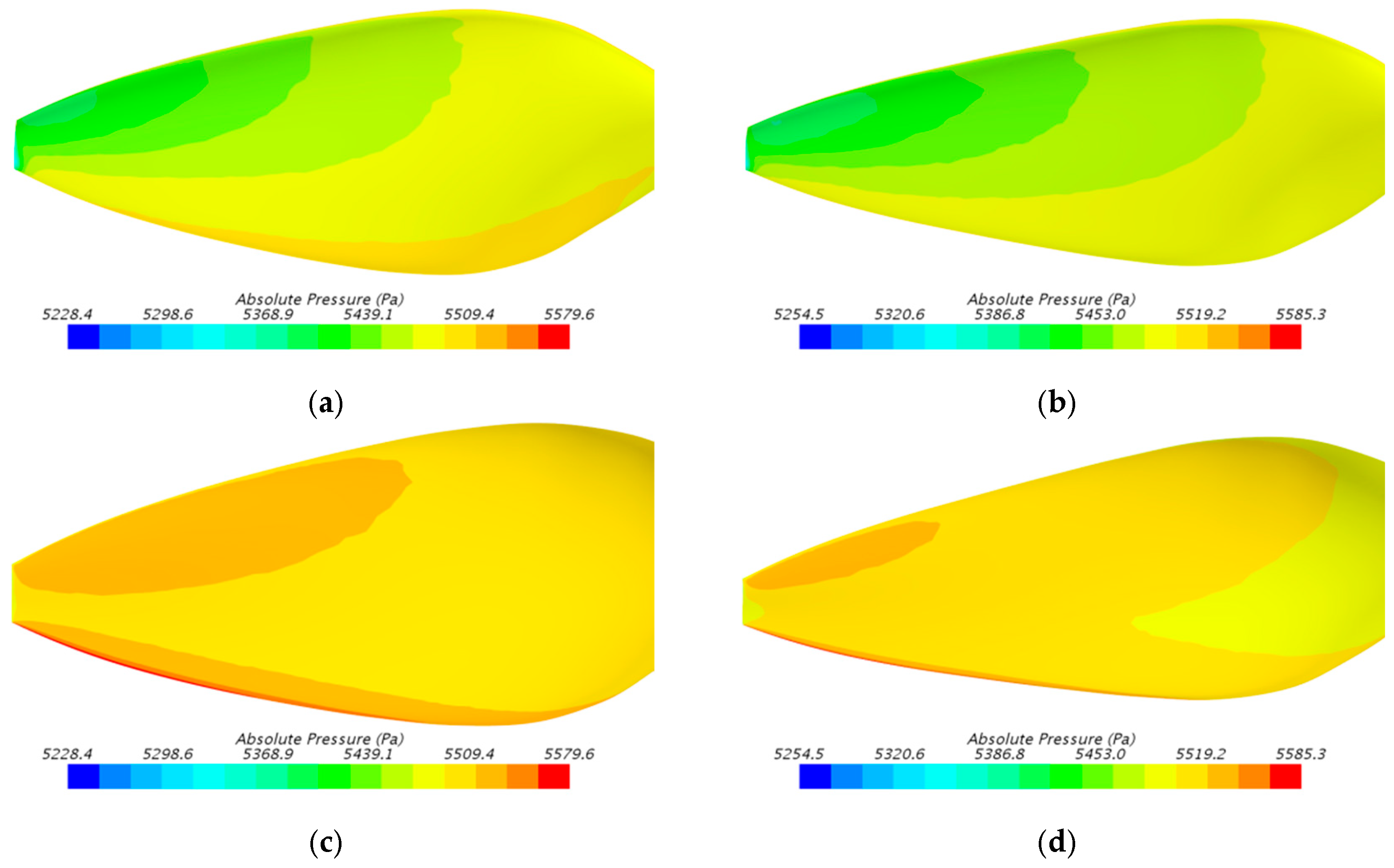

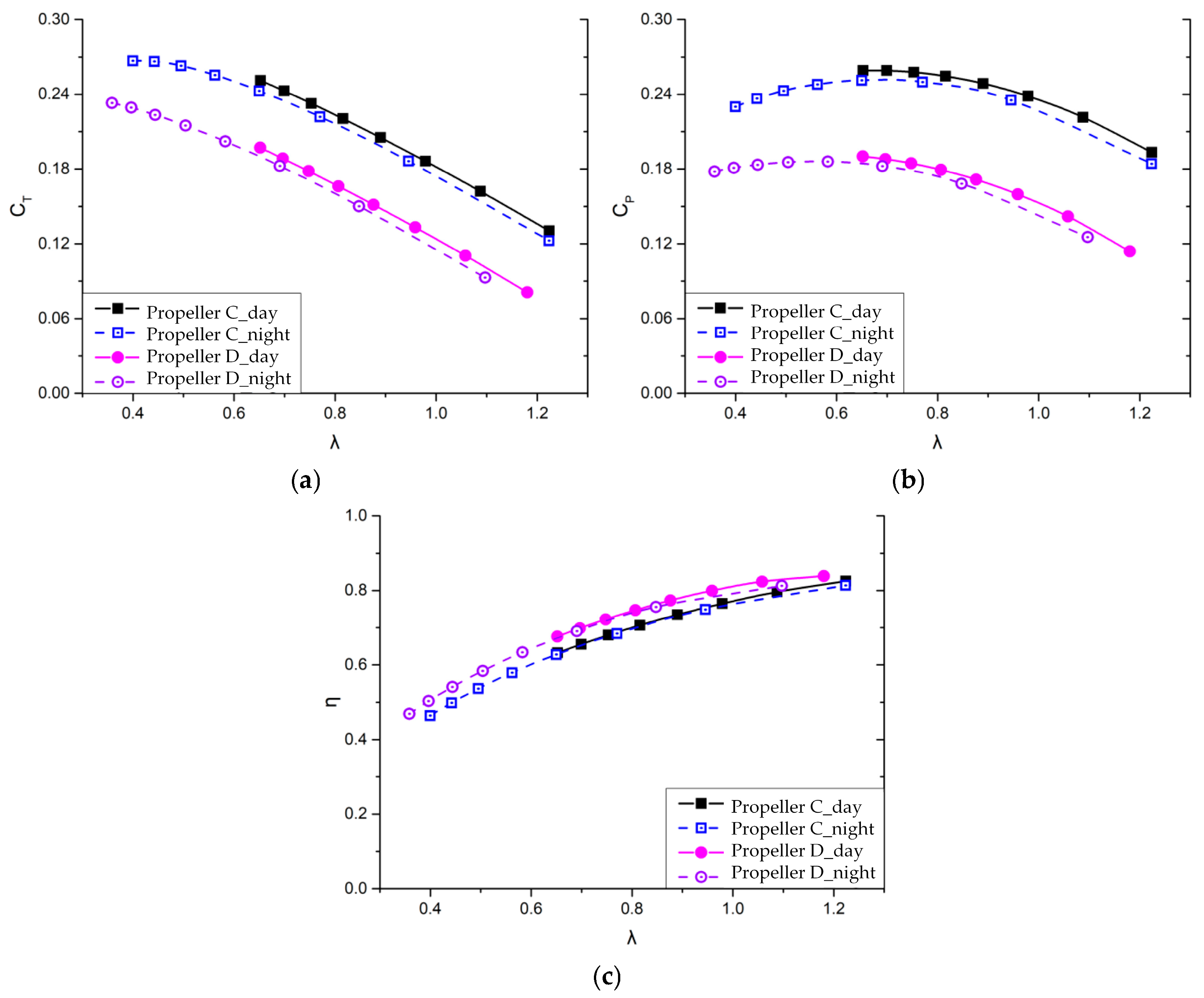

5.2. Comparison of Propeller Design Results Obtained by Maximizing Daytime and Nighttime Propeller Efficiency

5.3. Comparison of Overall Configurations Obtained by Maximizing Daytime and Nighttime Propeller Efficiency

- Optimum Propeller Efficiency During Daytime

- 2.

- Optimum Propeller Efficiency During Nighttime

6. Comparison of Different Design Schemes

7. Conclusions

- The propeller’s efficiency affects the total mass by influencing the mass of the storage battery, while the mass of the propeller itself has a smaller impact on the total mass.

- The propeller obtained through the efficient engineering method and the propeller obtained through single-objective optimization exhibit an almost identical performance, and the airship’s total mass is also nearly the same. Therefore, the efficient engineering method can be used to design the propeller, and can reduce the calculation load and improve optimization efficiency.

- Although the increased daytime speed raises the airship’s flight drag and increases the daytime power output, leading to an increased mass for the propulsion system and solar panels, the reduced nighttime speed lowers the nighttime energy consumption, thereby substantially reducing the mass of the storage battery.

- In the daytime-optimized scheme, although both daytime and nighttime propeller efficiencies are lower than those achieved by the constant speed design, the total airship mass still decreased by 28.0%. In the nighttime-optimized scheme, the propeller efficiencies during both day and night improved compared to the daytime-optimized scheme, resulting in a 29.6% decrease in the airship’s total mass.

8. Discussion

- In this paper, the aerodynamic performance is mainly obtained from theoretical analysis and numerical simulations. In the next step, wind tunnel tests or real-environment experiments can be conducted to further validate the performance prediction method.

- The next step may include collaborative optimization with the airfoil geometry to further improve propeller efficiency.

- Although the overall design method is improved in this paper, the daytime and nighttime speeds are still fixed values. In the future, variable flight speeds that change with time or with the input energy during daytime operation may be considered, to fully utilize the abundant daytime energy, reduce nighttime energy demand, and ultimately achieve a further reduction in the total mass. The effect of speed variation on other systems such as the structure integrity, control system and station keeping accuracy can also be investigated in the future.

- Maintaining the average speed of daytime and nighttime at a constant value is an initial criterion to ensure that the movement and station-keeping ability of the airship is on the same level as the original design. Further research can be performed to look into whether low speeds at night are detrimental to the station keeping ability of the airship.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HALE-D | High Altitude Long Endurance Demonstrator |

| NPL | National Physical Laboratory |

| BEMT | Blade Element Momentum Theory |

| CBE | Characteristic Blade Element |

References

- He, Y. Military Applications of Near-Space Platforms. Guofang Keji 2007, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, W. Study on Airship Networking Methods for Detecting Near-Space Hypersonic Targets. Xiandai Fangyu Jishu 2017, 45, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Current Status and Prospects of Emergency Communication Technology Development in China. Xiandai Dianxin Keji 2011, 41, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Shen, H. Analysis of the Development and Application of Near-Space Vehicles. Zhuangbei Zhihui Jishu Xueyuan Xuebao 2008, 19, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Dong, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Combat Capability Analysis of the Stratospheric Airship-Borne SIAR System. Jianchuan Dianzi Duikang 2018, 41, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, F. Early-Warning Capability Analysis of Near-Space Vehicles. Zhuangbei Zhihui Jishu Xueyuan Xuebao 2008, 19, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yue, S.; He, Z.; Sun, W. Research on Future Near-Space Defense Operations. Feihang Daodan 2017, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Chen, L.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Z.; Hu, W. Channel Characteristics and System Analysis of Near-Space Laser Communication. Dian Guang Yu Kongzhi 2008, 15, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, M.; Cai, R. Development Status and Application Prospects of Near-Space Science and Technology. Keji Daobao 2019, 37, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Zheng, W. Development Plan and Progress of U.S. Stratospheric Airships. Hangtianshi Gongcheng 2008, 17, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. The Theory of Air Propellers and Its Applications, 1st ed.; Beihang University Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beemer, J.D.; Parsons, R.R.; Rueter, L.L.; Seuferer, P.A.; Swiden, L.R. POBAL-S, the Analysis and Design of a High Altitude Airship. Final Report, October 1972March 1975. [For Station Keeping at an Altitude of 21 km for 7 Days; 500 W Fuel Cell Power Supply]; AD-A-012292; R-0275006; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1975.

- Smith, I.; Lee, M. The HiSentinel Airship. In Proceedings of the 7th AIAA ATIO Conf, 2nd CEIAT Int’l Conf on Innov and Integr in Aero Sciences, 17th LTA Systems Tech Conf; Followed by 2nd TEOS Forum; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2007; p. 7748. [Google Scholar]

- Androulakakis, S.P.; Judy, R. Status and Plans of High Altitude Airship (HAATM) Program. In Proceedings of the AIAA Lighter-than-Air Systems Technology (LTA) Conference, Daytona Beach, FL, USA; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2013; p. 1362. [Google Scholar]

- Schawe, D.; Rohardt, C.H.; Wichmann, G. Aerodynamic design assessment of Strato 2C and its potential for unmanned high altitude airborne platforms. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2002, 6, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wang, H.; Yang, X. Progress and Challenges in Stratospheric Airship Propulsion Systems. In Proceedings of the 3rd High-Resolution Earth Observation Annual Conference (Near-Space Earth Observation Technology Session), Changsha, China, 11–14 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama, M.; Shibata, M.; Yokokawa, A.; Kimura, K. Study of Propulsion Performance and Propeller Characteristics for Stratospheric Platform Airship; JAXA-RR-05-056; Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, P.; Ma, R. Aerodynamic Design of High-Altitude Airship Propellers. In Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of the Beijing Society of Mechanics, Beijing, China, 30 July–1 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y. Design and Experimental Study of High-Efficiency Propellers for Stratospheric Airships. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Duan, Z.; Ma, L.; Ma, R. Aerodynamics Properties and design method of high efficiency-light propeller of stratospheric airships. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tao, G. Numerical Simulation and Wind Tunnel Testing of a High-Altitude Propeller’s Aerodynamic Characteristics. Beijing Hangkong Hangtian Daxue Xuebao 2013, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, J.; Abdollahzadeh, M.; Silvestre, M.A.R.; Páscoa, J.C. High altitude propeller design and analysis. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.K.; Wang, X.L.; Cheng, Z.J.; Han, D. The efficiency analysis of high-altitude propeller based on vortex lattice lifting line theory. Aeronaut. J. 2017, 121, 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.; Song, B.F.; Zhang, Y.G.; Li, Y.B. Optimal design and experiment of propellers for high altitude airship. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 232, 1887–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, W. Performance Calculation and Design of Stratospheric Propeller; IEEE Access: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 14358–14368. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Tao, G.; Wu, Z. Performance Prediction and Design of Stratospheric Propeller. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, F.J. HASPA Design & Flight Test Objectives. In Proceedings of the AIAA 1975 Lighter-than-Air (LTA) Systems Technology Conference, Snowmass, CO, USA, 15–17 July 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ozoroski, T.; Mas, K.; Hahn, A. A PC-Based Design and Analysis System for Lighter-Than-Air Unmanned Vehicles. In Proceedings of the AIAA “Unmanned Unlimited” Technical Conference, Workshop, and Exhibit, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Lv, X. Configurations analysis for high-altitude/long-endurance airships. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2010, 82, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaupp, W.; Mundschau, E. Photovoltaic-hydrogen energy systems for stratospheric platforms. In 3rd World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion, 2003. Proceedings of; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.I.; Pant, R.S. A Methodology for Conceptual Design and Optimization of a High Altitude Airship. In Proceedings of the AIAA Lighter-than-air Systems Technology (LTA) Conference, Daytona Beach, FL, USA, 25–26 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kayhan, Z. A Thermal Model to Investigate the Power Output of Solar Array for Stratospheric Balloons in Real Environment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 139, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, G.; Wu, Z. Overall Design and Optimization of Stratospheric Airships Based on Improved CO-RS. Beijing Hangkong Hangtian Daxue Xuebao 2013, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, B.; Liu, B.; An, W. Research on Overall Design Methods for High-Altitude Airships. Xibei Gongye Daxue Xuebao 2007, 25, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Miao, J. Shape Optimization and Simulation of Near-Space Airships. Zhongguo Kongjian Kexue Jishu 2011, 31, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Gu, Y.; Li, Y. Multidisciplinary Optimization of Near-Space Airships Based on Genetic Algorithms. Jisuanji Fangzhen 2012, 29, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Research on Optimization Methods for Stratospheric Airship Overall Design. Master’s Thesis, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, D.; Hou, Z. Overall Parameter Optimization Design of Stratospheric Airships Based on Renewable Energy Simulation. In Proceedings of the 35th Chinese Control Conference, Yichang, China, 20–22 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Overall Design of a Small Solar/Hydrogen Hybrid-Powered UAV. Doctoral Thesis, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Song, B.; Wang, H.; Jiao, J. Modeling and Optimization of Stratospheric Airship Propulsion Systems Based on Energy Balance. Hangkong Donglixue Xuebao 2020, 35, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Song, B.; Yao, Q. Research on Solar Energy Systems for Stratospheric Airships. Zhongguo Kongjian Kexue Jishu 2009, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Sun, J.L.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Xing, J.; Xu, H.; Jia, L.; Lü, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, L. Solar Radiation Environment Research of Near Space in China. Guangpuxue Yu Guangpu Fenxi 2016, 36, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauert, H. Airplane Propellers. In Aerodynamic Theory: A General Review of Progress Under a Grant of the Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics; Durand, W.F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1935; pp. 169–360. [Google Scholar]

- Clerc, M.; Kennedy, J. The particle swarm-explosion, stability, and convergence in a multidimensional complex space. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Hatamlou, A. Multi-Verse Optimizer: A nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, S.; Joshi, P.; Pant, R. A generic methodology for determination of drag coefficient of an aerostat envelope using CFD. In AIAA 5th ATIO and16th Lighter-than-Air Sys Technology and Balloon Systems Conferences; Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Conferences; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P. Airship Design; University Press of the Pacific: Forest Grove, OR, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, G.A. Airship Technology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Project or Designer | Diameter (m) | Number of Blades | Propeller Efficiency | Design Altitude (km) | Inflow Velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POBAL-S airship [12] | 10.36 | 3 | 78% | 21 | 8 |

| HiSentinel airship [13] | 3 | 2 | 43% | 20 | 10 |

| HALE-D airship [14] | 2 | 2 | 40% | 18.3 | 10 |

| DLR airship [15] | 6 | 5 | 84% | 22 | - |

| Helions UAV [15] | 2 | 2 | 86% | - | - |

| Zephyr UAV [16] | 1 | 2 | 75% | 21.7 | 25 |

| Okuyama [17] | 4.2 | - | 68% | 18 | 16 |

| Hu Ying [18] | 5.95 | 3 | 60.3% | 20 | 20 |

| Nie Ying [19] | 9 | 2 | 64% | 21 | 20 |

| Liu Peiqing [20] | 6.5 | 3 | 75.8% | 20 | 20 |

| Wang Yufu [21] | 8 | 2 | 53% | 20 | 6 |

| Morgado [22] | 6 | 6 | 53% | 16 | 30 |

| Zheng [23] | 7.2 | 3 | 73% | 20 | 20 |

| Jiao Jun [24] | 6.8 | 2 | 70% | 20 | 20 |

| Liu Xinqiang [25] | 2.5 | 2 | 73.8% | 20 | 30 |

| Xie Cong [26] | 3.5 | 2 | 73.3% | 20 | 20 |

| Performance | CFD | BEMT | Difference | CBE | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0760 | 0.0766 | 0.79% | 0.0756 | −0.53% | |

| 0.0592 | 0.0576 | −2.70% | 0.0593 | 0.17% | |

| 0.7336 | 0.7598 | 3.57% | 0.7285 | −0.70% |

| Parameters | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 65.05 | −13.49 | 2.539 | −8.608 | −0.0099 | 0.1882 | 2.92 × 10−4 | 0.0703 | 0.0115 |

| (m/s) | RPM | T (N) | Efficiency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Objective Optimization | Efficient Engineering Method | Difference | |||

| 10 | 600 | 100 | 58.20% | 57.99% | −0.21% |

| 15 | 69.85% | 69.75% | −0.10% | ||

| 20 | 76.69% | 76.56% | −0.13% | ||

| 25 | 80.95% | 80.75% | −0.20% | ||

| 30 | 83.71% | 83.47% | −0.24% | ||

| 20 | 500 | 100 | 76.44% | 76.14% | −0.30% |

| 550 | 76.68% | 76.59% | −0.09% | ||

| 600 | 76.69% | 76.56% | −0.13% | ||

| 650 | 76.55% | 76.52% | −0.03% | ||

| 700 | 76.30% | 76.10% | −0.20% | ||

| 20 | 600 | 50 | 80.77% | 79.31% | −1.46% |

| 75 | 78.95% | 78.77% | −0.18% | ||

| 100 | 76.69% | 76.56% | −0.13% | ||

| 125 | 74.42% | 74.37% | −0.05% | ||

| 150 | 72.22% | 71.85% | −0.37% | ||

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Flight altitude | 20 km |

| Flight speed | 20 m/s |

| Mission payload | 100 kg |

| Mission power | 5 kW |

| Symbol | Parameter Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of propellers | 8 | - | |

| Avionics power | 1000 | W | |

| Payload power | 2000 | W | |

| Envelope area density | 0.26 | kg/m2 | |

| Solar panel area density | 0.20 | kg/m2 | |

| Propulsion system power density | 0.008 | kg/W | |

| Battery energy density | 0.0036 | kg/Wh | |

| Propulsion system efficiency | 0.82 | - | |

| Average solar panel efficiency | 0.15 | - | |

| MPPT conversion efficiency | 0.96 | - | |

| Battery charge/discharge efficiency | 0.95 | - | |

| Battery depth of discharge | 0.90 | - |

| Design Method | Propeller | Thrust T (N) | Torque M (N·m) | Thrust Coefficient | Power Coefficient | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-objective optimization | A | 167.36 | 75.21 | 0.1266 | 0.1022 | 70.79% |

| Efficient engineering method | B | 167.07 | 75.11 | 0.1265 | 0.1021 | 70.81% |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airship length l (m) | 127.59 | Propulsion system mass mthrust (kg) | 403 |

| Airship diameter d (m) | 50.31 | Structural mass mstructure (kg) | 2487 |

| Envelope surface area Senvelope (m2) | 20,167 | Envelope mass menvolope (kg) | 6619 |

| Envelope volume Venvelope (m3) | 169,102 | Helium mass mhelium (kg) | 2467 |

| Solar panel area Ssolar (m2) | 1343 | Solar panel mass msolar (kg) | 269 |

| Battery energy Ecell (Wh) | 723,043 | Battery mass mcell (kg) | 2582 |

| Propeller efficiency ηpropeller | 70.79% | Total airship mass mtotal (kg) | 14,904 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airship length l (m) | 128.41 | Propulsion system mass mthrust (kg) | 387 |

| Airship diameter d (m) | 50.20 | Structural mass mstructure (kg) | 2489 |

| Envelope surface area Senvelope (m2) | 20,252 | Envelope mass menvolope (kg) | 6647 |

| Envelope volume Venvelope (m3) | 169,457 | Helium mass mhelium (kg) | 2472 |

| Solar panel area Ssolar (m2) | 1341 | Solar panel mass msolar (kg) | 268 |

| Battery energy Ecell (Wh) | 721,674 | Battery mass mcell (kg) | 2577 |

| Propeller efficiency ηpropeller | 70.81% | Total airship mass mtotal (kg) | 14,917 |

| Design Method | Propeller | Time of Day | Speed V (m/s) | RPM | Thrust T (N) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime-optimized | C | Day | 28.56 | 600 | 285.43 | 70.64% |

| Night | 12.14 | 269.9 | 59.44 | 68.42% | ||

| Nighttime-optimized | D | Day | 29.73 | 681.7 | 304.52 | 72.23% |

| Night | 10.88 | 270 | 48.20 | 69.09% |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airship length l (m) | 107.44 | Propulsion system mass mthrust (kg) | 940 |

| Airship diameter d (m) | 46.53 | Structural mass mstructure (kg) | 1789 |

| Envelope surface area Senvelope (m2) | 15,707 | Envelope mass menvolope (kg) | 5157 |

| Envelope volume Venvelope (m3) | 121,813 | Helium mass mhelium (kg) | 1777 |

| Solar panel area Ssolar (m2) | 1652 | Solar panel mass msolar (kg) | 330 |

| Battery energy Ecell (Wh) | 183,058 | Battery mass mcell (kg) | 654 |

| Propeller nighttime speed RPMnight | 269.9 | Total airship mass mtotal (kg) | 10,732 |

| Nighttime flight speed Vnight (m/s) | 12.14 | Propeller nighttime efficiency ηpropeller | 68.44% |

| Daytime flight speed Vday (m/s) | 28.56 | Propeller daytime efficiency ηpropeller | 70.64% |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airship length l (m) | 106.36 | Propulsion system mass mthrust (kg) | 991 |

| Airship diameter d (m) | 46.26 | Structural mass mstructure (kg) | 1750 |

| Envelope surface area Senvelope (m2) | 15,456 | Envelope mass menvolope (kg) | 5074 |

| Envelope volume Venvelope (m3) | 119,160 | Helium mass mhelium (kg) | 1738 |

| Solar panel area Ssolar (m2) | 1716 | Solar panel mass msolar (kg) | 343 |

| Battery energy Ecell (Wh) | 144,536 | Battery mass mcell (kg) | 516 |

| Propeller daytime speed RPMday | 681.7 | Total airship mass mtotal (kg) | 10,490 |

| Daytime flight speed Vday (m/s) | 29.73 | Propeller nighttime efficiency ηpropeller | 72.23% |

| Nighttime flight speed Vnight (m/s) | 10.88 | Propeller daytime efficiency ηpropeller | 69.09% |

| Parameter Name | Single-Objective Optimization | Engineering Method Based on Characteristic Blade Element | Daytime- Optimized | Nighttime- Optimized | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airship length l (m) | 127.59 | 128.41 | +0.6% | 107.44 | −15.8% | 106.36 | −16.6% |

| Airship diameter d (m) | 50.31 | 50.2 | −0.2% | 46.53 | −7.5% | 46.26 | −8.1% |

| Daytime flight speed Vday (m/s) | 20 | 20 | 0.0% | 28.56 | +42.8% | 29.73 | +48.7% |

| Nighttime flight speed Vnight (m/s) | 12.14 | −39.3% | 10.88 | −45.6% | |||

| Propeller daytime efficiency ηpropeller | 70.79% | 70.81% | 0.0% | 70.64% | −0.2% | 72.23% | +2.0% |

| Propeller nighttime efficiency ηpropeller | 68.44% | −3.3% | 69.09% | −2.4% | |||

| Propulsion system mass mthrust (kg) | 403 | 387 | −4.0% | 940 | +133.3% | 991 | +145.9% |

| Structural mass mstructure (kg) | 2487 | 2489 | +0.1% | 1789 | −28.1% | 1750 | −29.6% |

| Envelope mass menvolope (kg) | 6619 | 6647 | +0.4% | 5157 | −22.1% | 5074 | −23.3% |

| Helium mass mhelium (kg) | 2467 | 2472 | +0.2% | 1777 | −28.0% | 1738 | −29.6% |

| Solar panel mass msolar (kg) | 269 | 268 | −0.4% | 330 | +22.7% | 343 | +27.5% |

| Battery mass mcell (kg) | 2582 | 2577 | −0.2% | 654 | −74.7% | 516 | −80.0% |

| Total airship mass mtotal (kg) | 14,904 | 14,917 | +0.1% | 10,732 | −28.0% | 10,490 | −29.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tao, G.; Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Song, R.; Xiang, B.; Chen, J.; Kang, Q.; Yin, J. Propeller Design Within the Overall Configuration of a Near-Space Airship. Drones 2026, 10, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020108

Tao G, Zhang J, Xie C, Song R, Xiang B, Chen J, Kang Q, Yin J. Propeller Design Within the Overall Configuration of a Near-Space Airship. Drones. 2026; 10(2):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020108

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Guoquan, Jizheng Zhang, Cong Xie, Ruixue Song, Bin Xiang, Jialin Chen, Qingyu Kang, and Jun Yin. 2026. "Propeller Design Within the Overall Configuration of a Near-Space Airship" Drones 10, no. 2: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020108

APA StyleTao, G., Zhang, J., Xie, C., Song, R., Xiang, B., Chen, J., Kang, Q., & Yin, J. (2026). Propeller Design Within the Overall Configuration of a Near-Space Airship. Drones, 10(2), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020108