1. Introduction

With the acceleration of urbanization, urban transportation systems face immense pressure. The low-altitude economy has emerged to alleviate congestion and enhance the efficiency of passenger and cargo transportation. Within this context, Urban Air Mobility (UAM) represents a transportation method that utilizes manned aircraft or autonomous drones to carry passengers and cargo within urban low-altitude airspace. UAM combines the scheduled nature of civil aviation with the on-demand responsiveness of urban ground transportation, offering potential to relieve ground traffic congestion and positioning itself as a key future mode of travel.

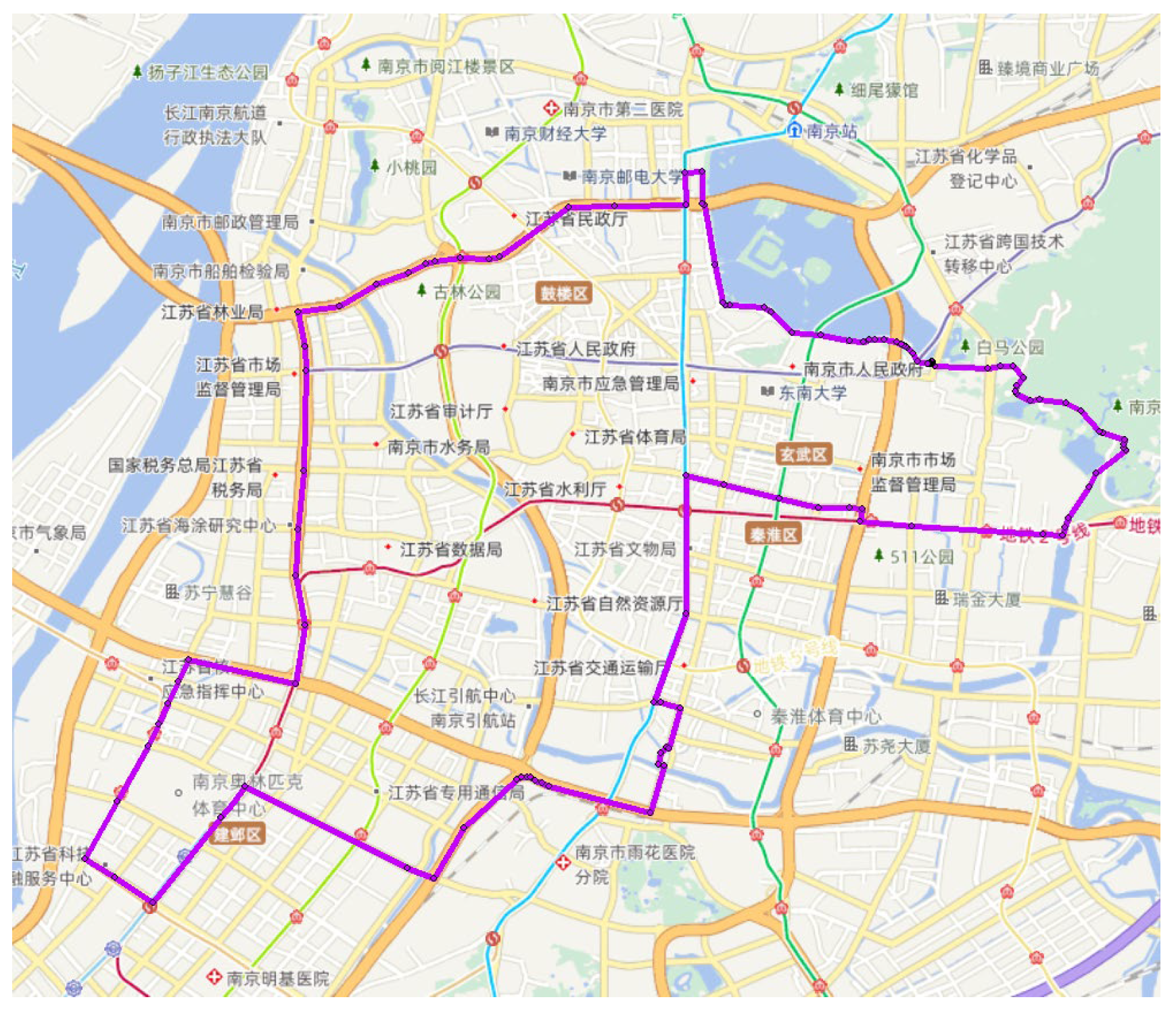

China’s modernization has entered a new stage, with the people’s aspirations for a better life growing ever higher. As urban modernization progresses, an increasing number of large-scale public events are being organized. Large-scale public events refer to activities organized by legal entities or other organizations for the general public, each expected to attract 1000 or more participants. These events include: sports competitions; concerts, musical performances, and other artistic events; exhibitions and trade shows; garden parties, lantern festivals, temple fairs, flower festivals, and fireworks displays; job fairs; and lottery sales with live draws [

1].

However, drone flights in urban environments, particularly during large public events such as marathons or concerts, can exert considerable influence on ground crowds and may even pose serious safety hazards. Chen Yijun et al. [

2] noted that drone flights can not only disrupt normal activities of ground crowds but also trigger panic and chaos, especially in densely populated areas. As drone flights become more frequent, Wei Wei [

3] highlighted in their research that particularly in low-altitude zones, beyond the risk of drone crashes, even drone noise and changes in flight posture can cause panic among gathered crowds, potentially leading to severe accidents like stampedes.

When drones fly into densely populated areas, not only the noise of their flight but even their mere presence can provoke unexpected reactions or anxiety among individuals in the crowd. Particularly in crowded conditions, sudden exposure to flying objects (even without actual crashes) may cause individuals to experience emotional agitation, anxiety, or panic. Such reactions can escalate into collective psychological tension and panic within the crowd, potentially leading to severe stampede incidents [

4].

French sociologist Le Bon [

5] studied psychological and behavioral shifts in crowds, such as conformity, bravado, emotional contagion, diminished sense of responsibility, and extreme actions. He developed the theory of crowd conformity, explaining how this phenomenon significantly impacts crowd safety during disasters. Following further investigations into crowd conformity psychology and associated behavioral patterns, Smelser [

6] noted that conformity as an irrational behavior can influence and precipitate accidents and disasters. David [

7] offered a psychological analysis explaining conformity behavior, highlighting the cyclical reactions inherent in crowd conformity phenomena.

Specifically, drones approaching crowds particularly during large-scale events like marathons or gatherings may trigger collective panic. In such scenarios, individual behavior is often influenced by the reactions of surrounding crowds, leading to a “bandwagon effect.” That is, individuals who initially feel no panic may rapidly develop unease upon observing others even just a few reacting with alarm, thereby fueling the spread of collective panic. This collective panic intensifies crowding in already dense areas, and once the situation spirals out of control, it can easily result in stampede accidents [

8].

According to the Interim Regulations on the Management of Unmanned Aircraft Operations, for large-scale public events held on the ground, unmanned aircraft are currently primarily restricted to isolated flight operations to prevent incidents such as drone crashes or interference with event surveillance. Temporary airspace control measures are implemented, with air traffic management authorities determining the vertical and horizontal boundaries of relevant zones and their usage periods [

9]. However, with the rapid growth of low-altitude economic activities, increasing drone traffic and cargo capacity, large-scale airspace closures become increasingly impractical and may disrupt overall urban air traffic operations. Particularly for large-scale sporting events like marathons, which span nearly the entire urban area and last for extended periods, simply closing airspace could potentially paralyze the entire urban air traffic system when tens of thousands of drones are in operation. This would constitute an unacceptable catastrophe, simultaneously failing to meet emergency response and rescue requirements. Therefore, future urban air traffic systems should not rely on simplistic, blanket closure zones.

Therefore, when designing and planning UAV flight routes, it is crucial to account for the safety of ground crowds and to establish an effective mechanism that integrates risk assessment with adaptive flight planning. However, most existing UAV path-planning studies still focus on static optimal routing, dynamic obstacle avoidance, multi-UAV coordination, or intelligent learning-based optimization [

10], with relatively limited attention paid to risk-aware routing in urban, dynamically sensitive areas within the emerging low-altitude economy.

Existing advances in autonomous navigation and intelligent control span multiple domains, including urban multi-UAV planning, hybrid optimization for robotic motion, and hierarchical traffic control. For example, hierarchical UAV planning frameworks combining PSO with enhanced ACO have improved computational efficiency in structured low-altitude environments, while hybrid learning–optimization schemes in robotic manipulators demonstrate the benefits of integrating global trajectory planning with local adaptive correction. Similarly, hierarchical ground traffic-control strategies using real-time data show that selective, data-driven interventions often outperform full system restrictions. Despite these developments, current research primarily emphasizes algorithmic efficiency, energy consumption, or traffic throughput, and rarely addresses safety-critical scenarios involving dense, dynamic ground populations [

11,

12,

13].

To further clarify these limitations, prior work on collision-free robotic motion planning, such as hybrid global–local optimization for multi-manipulator synchronization—which mainly focuses on inter-robot collision avoidance within controlled settings [

14]. Although such approaches enhance local adaptability, they address only microscale agent-to-agent interactions and do not consider system-level safety constraints shaped by human crowd dynamics. In contrast, the present study targets a broader and more socially critical problem: ensuring UAV operational safety during large-scale public events by coupling global path optimization with real-time ground-risk evaluation. This shifts the planning objective from preventing autonomous-agent collisions toward safeguarding dynamic, densely distributed human populations, an aspect largely overlooked in existing literature.

Building on this motivation, this study develops a risk-aware flight-planning framework that integrates ground-density estimation, flight-path modeling, and real-time risk assessment. The proposed method dynamically adjusts UAV trajectories to avoid high-risk areas, thereby reducing accident probability while supporting the sustainable development of the low-altitude economy. Future real-world low-altitude route-network data can seamlessly replace the simulated data used in this study without altering the methodology or the main conclusions.

3. Model Construction and Methods

3.1. Scope Clarification and Simulation Assumptions

To maintain the focus on the methodological contributions of this study, several practical operational factors are intentionally simplified in the simulation environment. The objective of this work is to develop an effective dynamic risk-aware route-planning strategy for UAV operations over large public events, rather than to construct a full-fidelity flight-physics model. The assumptions adopted in the simulation are summarized as follows:

- (1)

Power consumption is not modeled.

Energy usage, battery discharge models, and power variations during straight flight versus hovering are crucial in real-world UAV mission planning. However, this study focuses on the algorithmic mechanism of dynamic risk assessment and route adaptation. Therefore, power-related constraints are excluded from the simulations and will be considered in future extensions.

- (2)

Weather effects are not considered.

Environmental factors such as wind fields, turbulence, rain, or temperature can influence UAV performance and routing decisions. These belong to the operational stage of urban low-altitude traffic management. Since the present work aims to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed risk-aware routing strategy, meteorological disturbances are omitted.

- (3)

Route-following control is abstracted.

The simulation adopts a centralized scheduling architecture equivalent to a virtual ground control station. UAV movement along each edge is modeled as kinematic motion at constant velocity without implementing a specific flight controller. Detailed actuator dynamics, tracking controllers, or attitude-stabilization loops are beyond the scope of this study.

- (4)

Urban environmental constraints are simplified.

Real-world low-altitude airspace is shaped by buildings, terrain, restricted zones, and existing transportation infrastructure. These constraints significantly influence the feasible structure of UAM corridors. In this study, the network is represented as an idealized graph of straight-line connections between nodes to isolate and examine the algorithmic behavior of the proposed risk-aware routing strategy. Incorporating realistic urban airspace constraints requires detailed geographic and regulatory datasets, which will be addressed in future work when such data become available.

These assumptions allow us to isolate and analyze the core contribution of this study: the integration of ground-crowd risk, air-traffic risk, and dynamic route adjustment strategies while keeping the simulation environment computationally tractable.

3.2. Path Planning Methods

After extracting drone flight zones via GIS or grid division, they are abstracted into a weighted directed graph G = (V, E), where:

V = {, , …, } Indicates flight nodes (such as takeoff/landing points, turning points);

E = {} Represents feasible flight segments between nodes, where each edge carries a length weight that integrates comprehensive costs such as flight distance and risk level.

The Ripple-Spreading Algorithm (RSA) [

18] is a heuristic optimization algorithm that simulates the propagation of water ripples for shortest path searches on graphs. By dynamically modeling the diffusion of information through “ripples,” this algorithm achieves path search from start to end points. At its core, it is a multi-source parallel shortest path exploration method based on distance expansion. Compared to the traditional Dijkstra algorithm [

19], RSA offers superior parallelism and scalability, making it suitable for path planning problems in complex networks. It is particularly well-suited for drone route planning involving multiple takeoff and landing locations in urban low-altitude airspace [

20].

3.3. Ground Risk Map Construction Methods

To effectively guide the safe operation of drones in low-altitude urban environments and prevent interference or risks to densely populated areas on the ground, this study developed a risk scoring system that integrates ground personnel density with flight-path traffic frequency. This system supports dynamic updates to risk maps and provides feedback for dynamic path planning. Drawing upon the

KNS risk assessment method from the research of Wu Xianguo et al. [

21], this study applies it to evaluate the risks posed by drones to personnel at large-scale ground events. A three-factor fusion model is introduced to construct a dynamic risk score R for each flight path segment, defined as follows:

where:

K: Fixed drone risk weight (set as a constant representing the inherent risk of drones, K = 4);

: Flight frequency score per unit time on the segment where edge is located;

: Ground personnel density score within the area corresponding to edge (unit: persons/m2, calculated by tier);

: Final risk level, used for heatmap visualization and path avoidance decisions.

This model flexibly integrates aerial activity intensity (flight density) with ground disturbance levels (crowd density), enabling a unified air-ground dynamic safety assessment.

The proposed KNS model follows the classical semi-quantitative risk evaluation logic, in which risk is expressed as the combination of accident likelihood, exposure frequency, and consequence severity. This logic originates from the LEC method developed by Graham and Kinney, which is widely used for the assessment of hazardous operations. In the context of urban low-altitude drone operations, the falling-object hazard to the ground population is analogous to impact hazards considered in LEC. Meanwhile, drones frequently fly above dense crowds during large-scale events, which corresponds to high exposure conditions. Therefore, the parameters K, N, and S are mapped to consequence severity (C), likelihood (L), and exposure frequency (E), respectively, forming a quantitative representation of the same risk decomposition logic.

- (1)

Basis for K Values

Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) is a methodology for evaluating ground and air risks associated with UAV operations. It provides air traffic management authorities, operators planning to conduct specific-category UAV operations, air traffic management service providers, and relevant third parties with a means to assess whether UAVs can operate safely at a risk-assessed confidence level. According to the “Management Procedures for Specific Category UAS Trial Operations (Interim)” (AC-92-2019-01) [

22], the inherent ground risk level (from 1 to 10) in SORA assessments is determined by the UAV characteristics (maximum characteristic dimensions and maximum speed) as well as the risk population density within the operational area and ground risk buffer zone. First, the “ground operational area type” of the UAV must be defined. The ground operating envelope includes the flight zone, contingency zone, and ground risk buffer zone. Ground operating envelope types are categorized based on the magnitude of the “maximum population density value.” Subsequently, the “inherent ground risk level (IGR)” is automatically determined using the matrix in

Table 1 below, based on the “maximum population density value” of the ground operating envelope and the UAV’s “maximum characteristic size” and “maximum operating speed.”

For a typical multi-rotor UAV configuration used in public-event monitoring—maximum dimension 0.3–0.6 m, maximum speed 15–20 m/s, operating over a high-density crowd area (≥10 persons/m2)—the SORA lookup matrix typically yields an IGR value in the range of 4 to 6. To adopt a conservative yet representative value for risk-scoring, this study selects K = 4, which corresponds to the lower bound of the applicable IGR range.

- (2)

Flight Density Modeling ()

The flight density score

for each edge

is calculated as follows:

where:

: Number of drones passing through edge within time window T;

T: Unit time/h;

Classify

into grades (I–V) based on drone traffic intervals (see

Table 2) to reflect route congestion levels.

- (3)

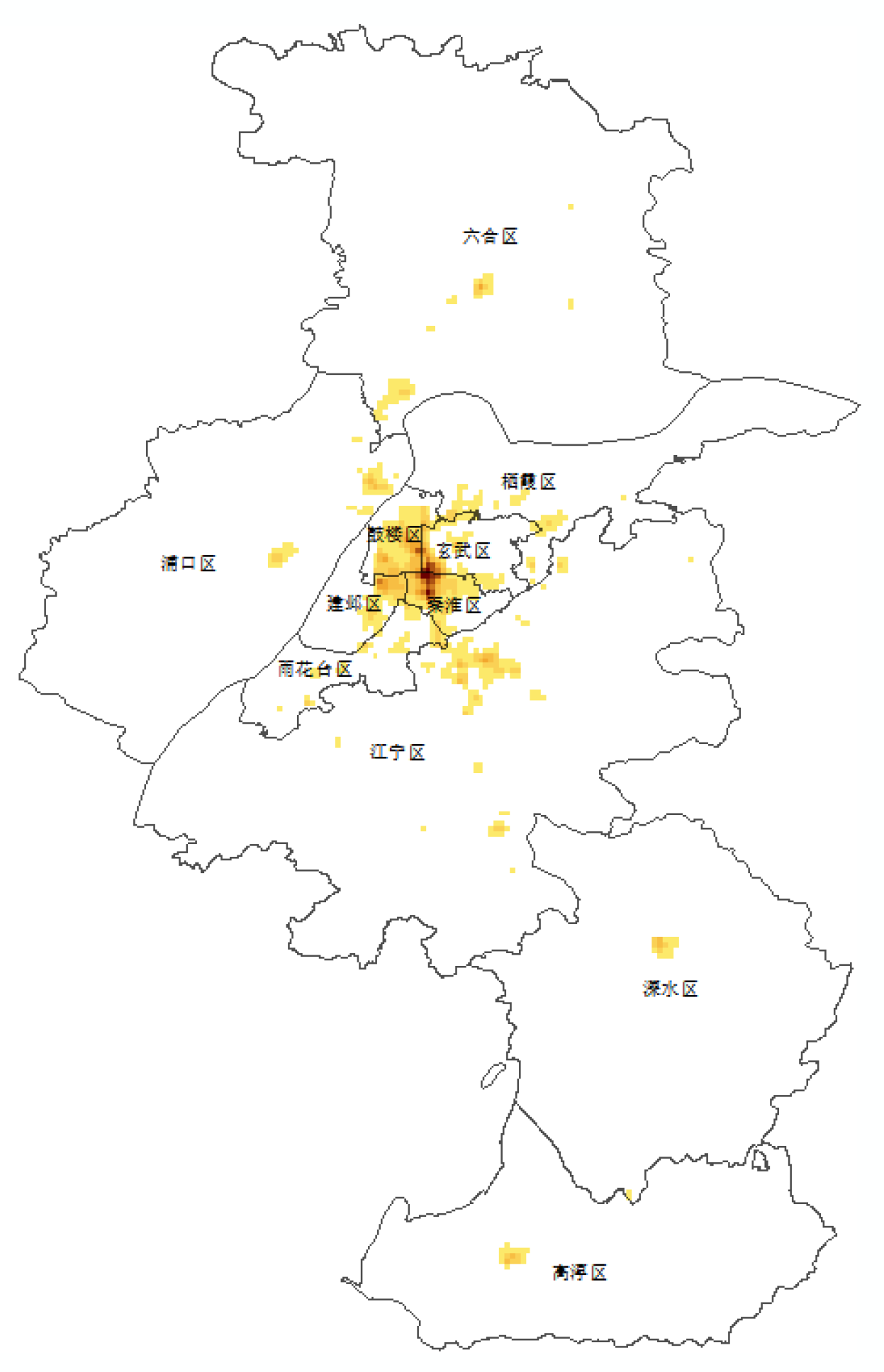

Ground Personnel Density Modeling ()

This study simulated two types of ground personnel: (1) Static personnel: such as spectators at the starting point and volunteers at aid stations, with fixed locations and constant numbers; (2) Dynamic crowds: such as marathon runners and mobile spectators, whose positions update over time. Using a grid partitioning method (each grid cell measuring 1 m × 1 m), this study calculated the number of people per unit area within each grid cell to construct a ground personnel density heatmap. Based on the density values proposed by Cai Mufu [

23] in his research on graded early warning systems for crowd density in open public spaces, this study classifies

into four levels as shown in

Table 3:

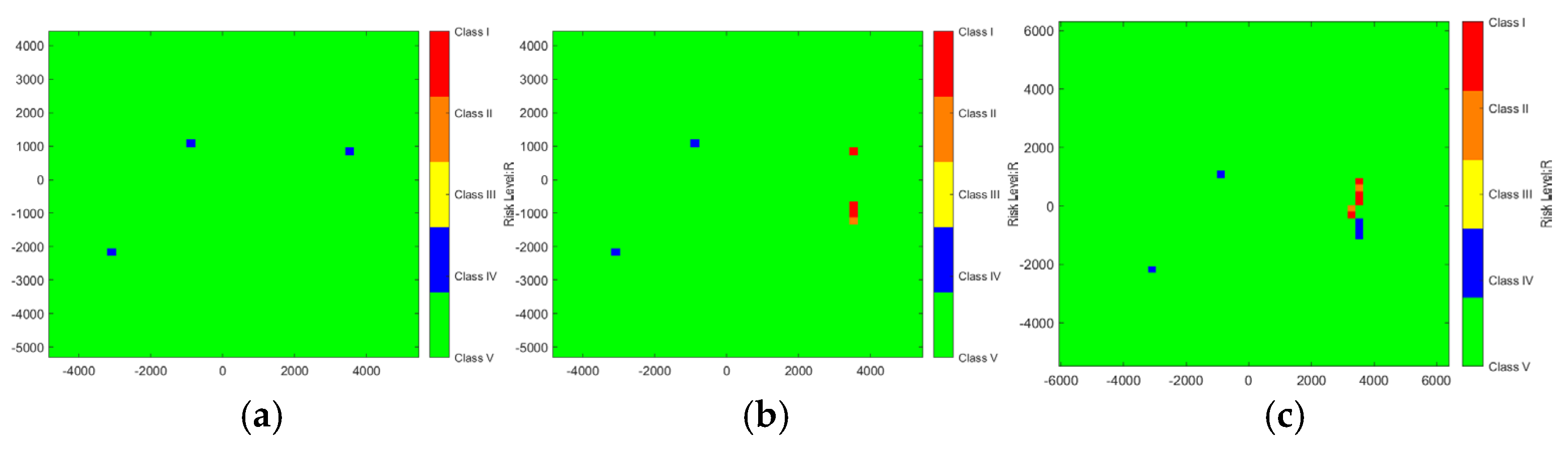

To visually demonstrate crowd density during the marathon, this study employs MATLAB to generate a crowd density heatmap. The heatmap uses color gradients to represent varying crowd densities and updates in real-time to reflect crowd movement. Red represents areas of high density, while blue indicates areas of low density.

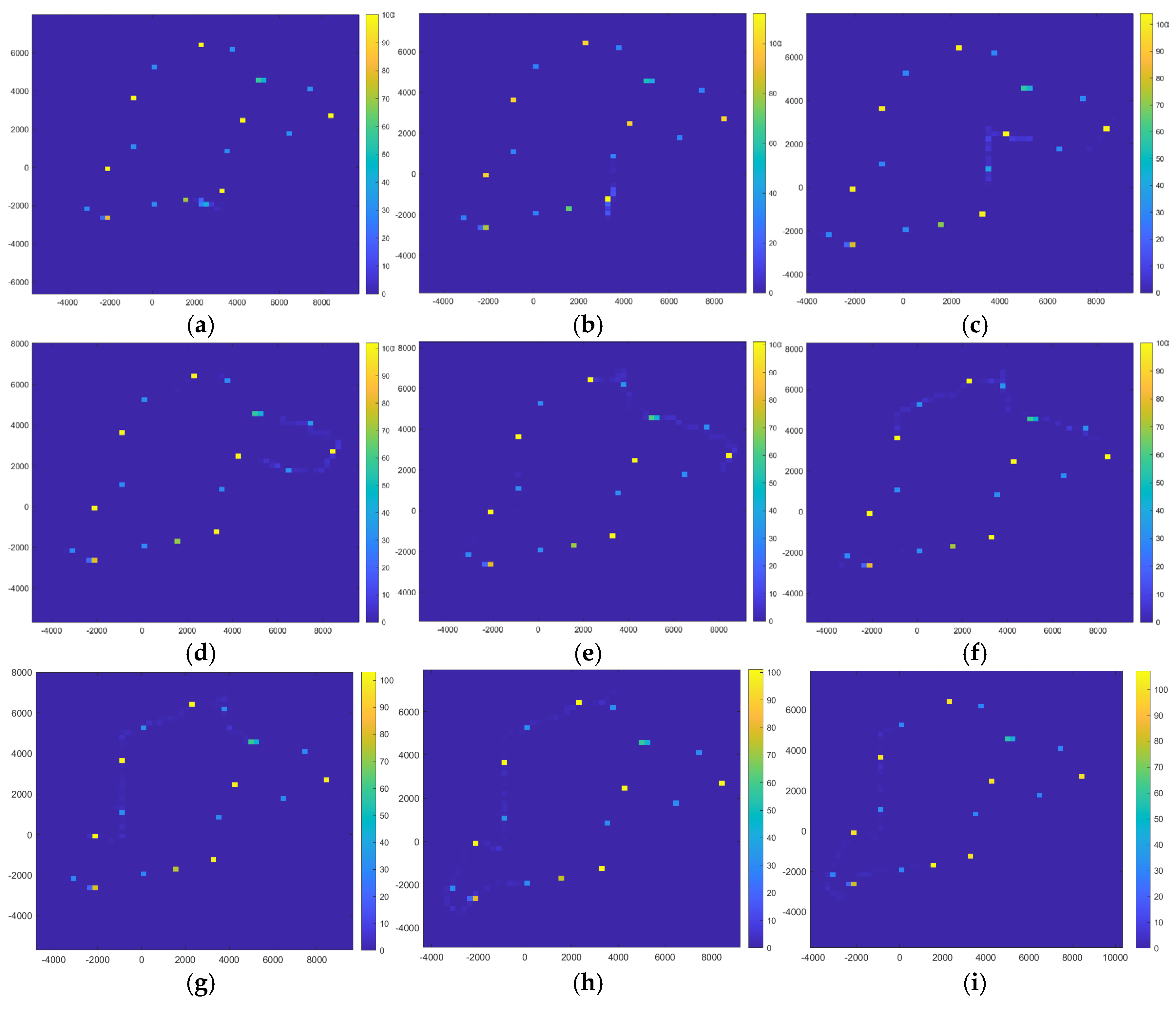

Figure 5 illustrates the dynamic evolution of crowd density throughout the simulation.

After calculating

for each edge using Formula (1), the results are classified into risk levels and mapped following the criteria in

Table 4:

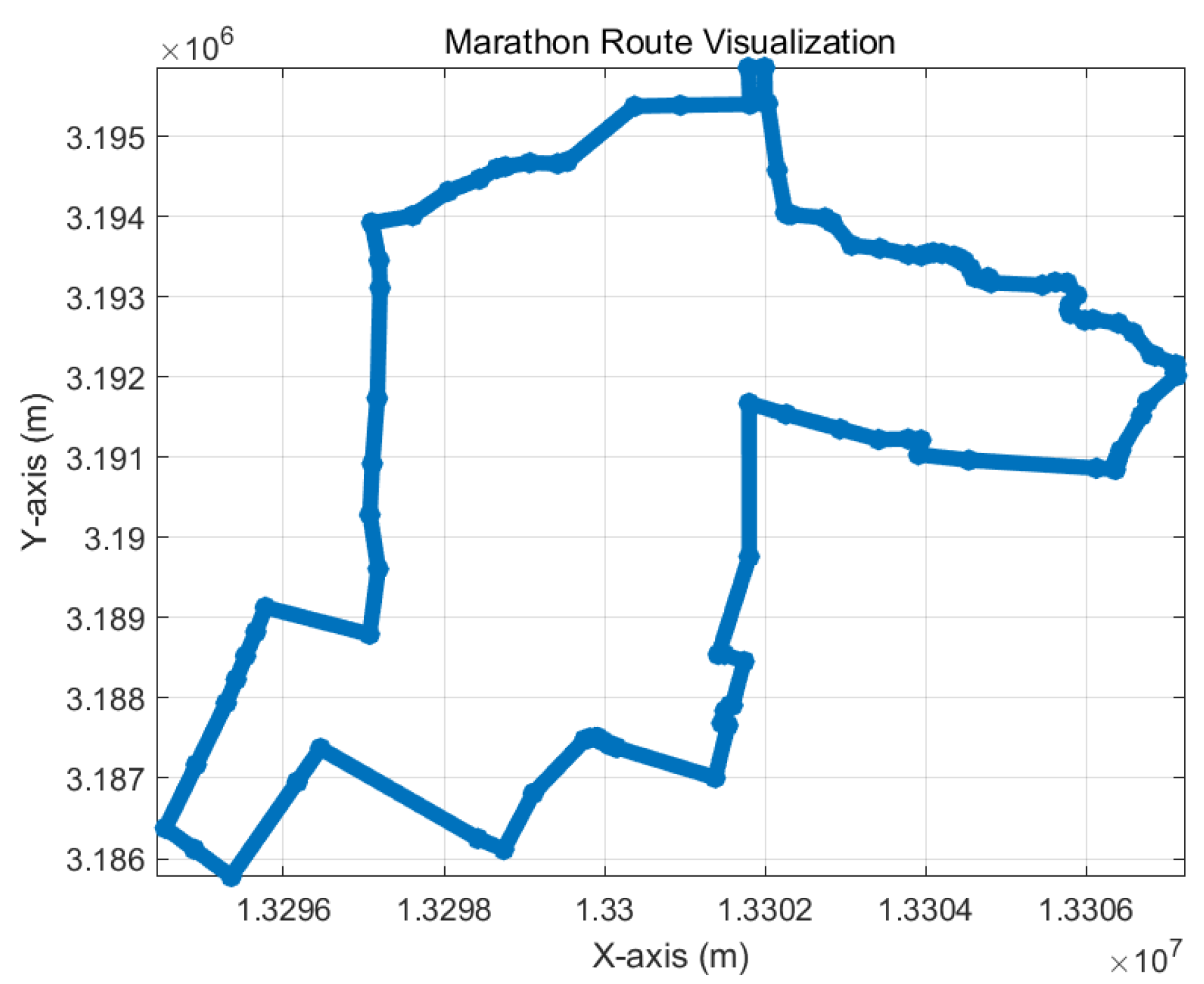

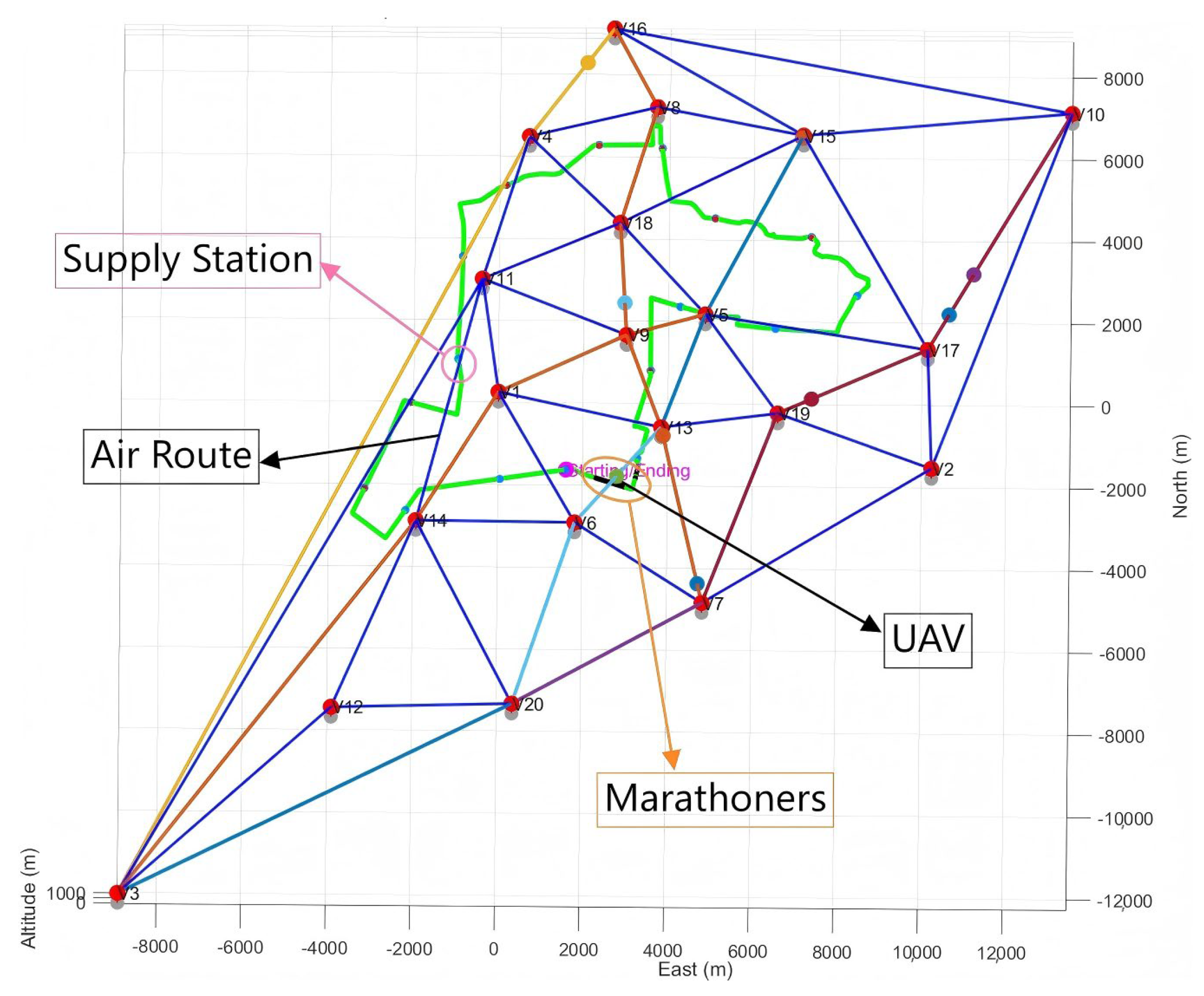

3.4. UAV Mission and Flight Plan Settings

First, node V20 in the urban air traffic network is selected as the UAV’s takeoff point, and node V16 as the destination, establishing a typical single-origin-single-destination (single-source-single-sink) takeoff-and-landing mission scenario. This path traverses multiple critical network zones, illustrating typical network connectivity and path complexity. The Ripple-Spreading Algorithm (RSA) is employed to dynamically compute all reachable paths within the network. The optimal path from V20 to V16 is identified as [V20-V6-V1-V11-V4-V16].

The simulation was then extended to a multi-origin-multi-destination (multi-source-multi-destination) scenario to align with the operational requirements of multiple drones simultaneously executing distributed tasks in real-world low-altitude economic operations. This simulation designates nodes V

3, V

7, and V

20 as drone takeoff points, corresponding to key landing zones in the western, central, and eastern urban areas, respectively. Nodes V

10, V

15, and V

16 are selected as flight mission destinations. The resulting multi-source multi-destination flight path is shown in

Table 5.

The results cover multiple core pathways and critical node connections within the urban aerial network, demonstrating the RSA’s strong adaptability and outstanding path planning performance in multi-task intensive scenarios.

Based on modeling single-source single-destination and multi-source multi-destination flight missions, drone flight planning modeling is performed for the entire urban air traffic network in Nanjing. The simulation runs from 8:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., at 5 min intervals, randomly generating drone flight missions across 20 nodes. A UAM drone flight schedule, including takeoff times, landing times, origin and destination node IDs, flight paths, estimated durations, and total distances, is generated as shown in

Table 6 for subsequent research purposes.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

Figure 6 shows that drones frequently traverse densely populated areas during missions, with supply stations often located along critical flight paths. To analyze potential impacts, this study developed a city-level ground risk heatmap within the simulation system, featuring dynamic updates and tiered risk visualization. Path adjustments are triggered in high-risk zones, involving detours or hovering maneuvers to ensure integrated ground-air coordination.

4.1. Evolutionary Patterns of Risk Maps

Based on the ground risk map construction method described in

Section 3.3, a risk heatmap for the simulation area is produced. This map covers the entire ground area in a grid format, providing real-time visualization of the potential disturbance risk for each region. By analyzing the risk maps at different time points shown in

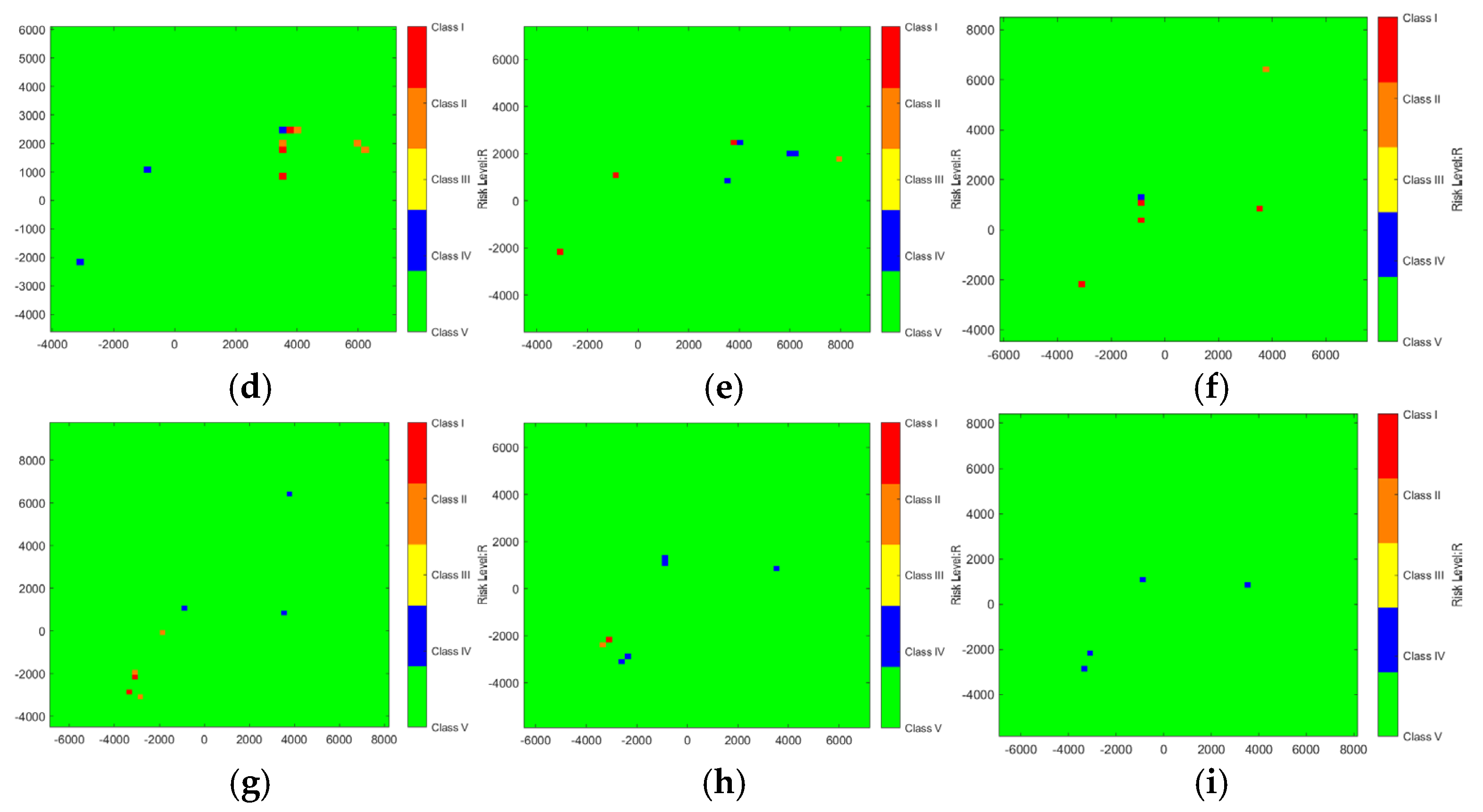

Figure 7 (alphabetical labels denote temporal sequence), the following patterns of risk map evolution can be summarized. The observed patterns are summarized as follows:

Initial Stage (

Figure 7a): The entire map displays extensive Level V (green) zones, with only localized Level IV (blue) warnings near certain nodes. Overall, the risk level remains within acceptable limits

Early Development Stage (

Figure 7b,c): As the UAV mission commenced, localized increases in aerial traffic density led to rapid activation of Level II (orange) and Level I (red) alerts in densely clustered node areas (approximately at coordinates x = 4000, y = 2000). This indicates coinciding risks between aerial flight paths and ground crowds.

Risk Diffusion Stage (

Figure 7d,e): As the marathon progressed, multiple overlapping high-risk clusters emerged throughout different zones, accompanied by a marked increase in red and orange areas. Continuous high-risk corridors formed, particularly around urban core nodes. This indicates that air traffic and ground activities frequently intersected during this stage, marking a critical period for dynamic risk management.

Mid-to-Late Stage (

Figure 7f,g): Spatial shifts and new hotspots appear in specific high-risk areas. For instance, the upper region in

Figure 7f shows an orange Level II warning for the first time, indicating that a new task-concentration zone has emerged as a potential risk source. Meanwhile, the left area in

Figure 7g displays an interlacing of red and blue zones, suggesting that ground crowd gatherings coincide with new UAV tasks in this region.

Final Stage (

Figure 7h,i): The number of high-risk areas begins to decrease, with red and orange zones significantly diminishing. Most regions revert to blue and green statuses, indicating the marathon is nearing its conclusion and the overall system risk is gradually declining.

4.2. Flight Safety Management Strategy

Based on different risk levels in the heatmap, the system introduces corresponding safety strategy control mechanisms for flight path planning:

Level I and Level II High-Risk Areas: If a drone’s planned flight path traverses a high-risk area, the following strategies are applied for modifying the flight plan: (1) Replan new flight paths to bypass high-risk zones; (2) Hover in place until risks in high-risk zones decrease to a safe passage threshold; (3) If hovering exceeds a set threshold (e.g., 300 s), the system determines the mission is deemed unfeasible and automatically returns to base.

Level III Medium-Risk Area: The system permits flight passage, but recommends optimizing the flight path to minimize dwell time within this area.

Level IV and Level V Low-Risk Areas: These areas present lower risks and are prioritized as preferred segments for route planning. The system selects these routes first to enhance overall operational efficiency.

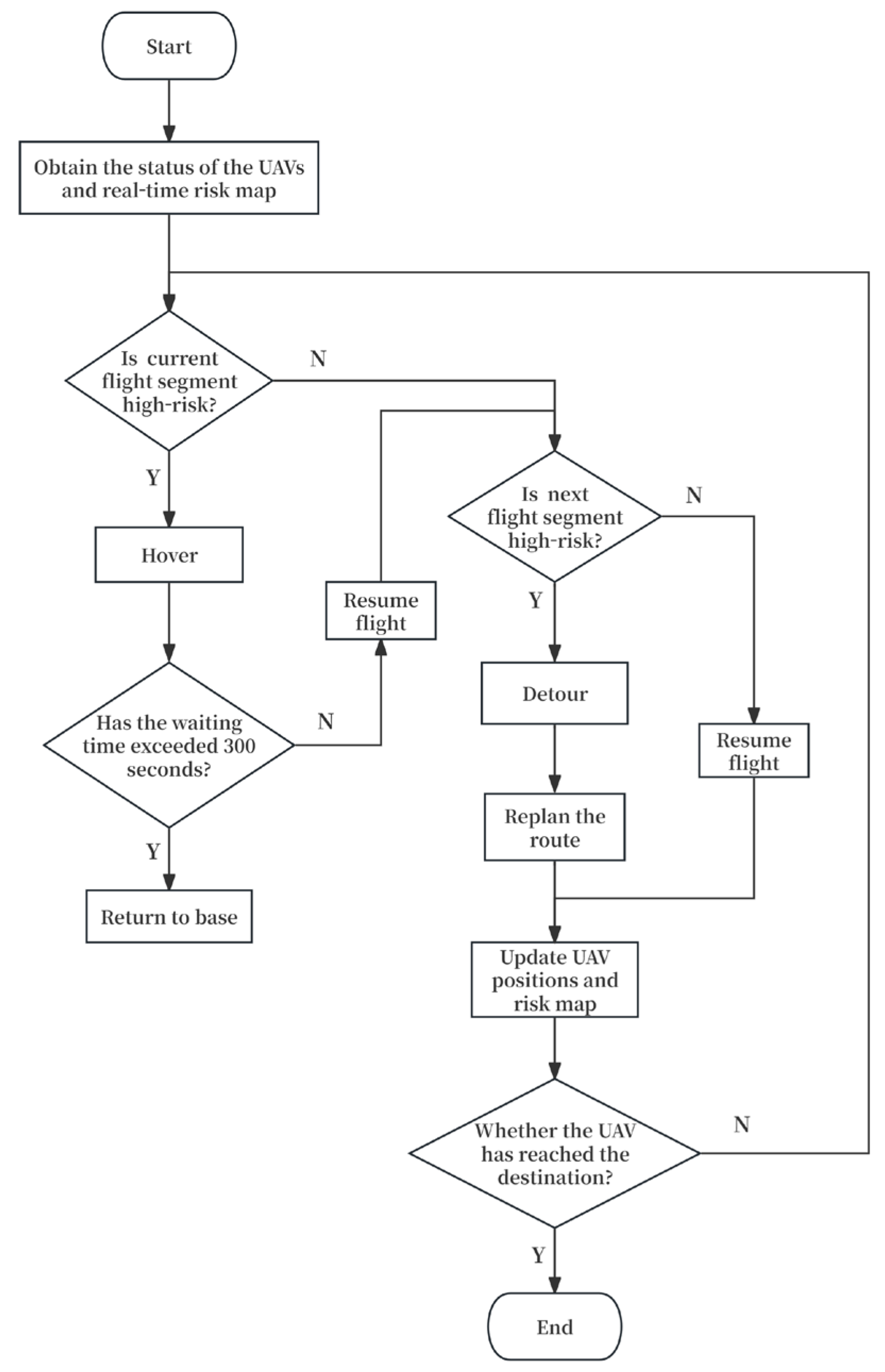

To further clarify the operational logic of the proposed risk-aware flight safety strategy, we summarize the key decision-making steps within a unified process flow, as shown in

Figure 8.

Figure 8 illustrates the dynamic safety control logic adopted in this study. Rather than representing a static or one-shot trajectory planning process, the proposed strategy operates in a closed-loop manner throughout the mission execution. During flight, the UAV continuously acquires its current state and the time-varying risk map, and risk evaluation is performed in a rolling manner for both the current and the upcoming flight segments.

Depending on the detected risk level, the UAV dynamically switches between temporal avoidance (hovering) and spatial avoidance (detouring), followed by path replanning when necessary. After each control action, the UAV position and the risk map are updated, and the decision process is repeated until the destination is reached. This iterative update-and-decision mechanism enables the proposed framework to adapt to evolving crowd-induced risks in real time.

To support the closed-loop safety control logic illustrated in

Figure 8, a path-planning algorithm capable of responding efficiently to frequent risk updates and replanning requests is required. In this study, the Ripple-Spreading Algorithm (RSA) is adopted as the underlying planning mechanism to enable incremental and adaptive path updates during mission execution.

The Ripple-Spreading Algorithm (RSA) is selected in this study due to its suitability for dynamic, risk-aware path planning rather than its optimality in static shortest-path problems. Compared with classical planners such as Dijkstra or A*, which typically require repeated global recomputation when edge costs change, RSA adopts a wavefront-based propagation mechanism that supports localized and incremental updates. This property aligns well with the proposed safety control framework, where risk levels evolve over time and replanning is triggered only in localized high-risk regions. Therefore, RSA provides a practical balance between computational efficiency and responsiveness for real-time UAV operations in dynamically changing risk environments.

Moreover, compared with sampling-based planners such as RRT*, which rely on probabilistic exploration in continuous space, RSA operates directly on the graph-based low-altitude airspace representation adopted in this study, resulting in more predictable behavior under frequent replanning. It is therefore employed here as a representative dynamic path-planning component to support risk-aware safety control, rather than as the primary object of algorithmic comparison. A comprehensive benchmarking against alternative planners is beyond the scope of the present work and is left for future research.

4.3. Model Performance Evaluation

To comprehensively illustrate how the proposed safety control strategy operates during mission execution, 412 UAV missions were simulated under two scenarios: a baseline scenario without safety control and a controlled scenario with the proposed strategy activated. A comparative analysis of UAV flight data across the two scenarios was then performed to extract the execution characteristics of safety control actions, which are summarized in

Table 7. The experiments presented in

Table 7 consider independent route executions to evaluate the risk-sensitive path-planning mechanism itself. Since this study focuses on ground–air risk interactions rather than UAV-to-UAV deconfliction, separation assurance and collision avoidance at nodes or edges are not considered.

- (1)

Mission distribution by risk-avoidance strategy

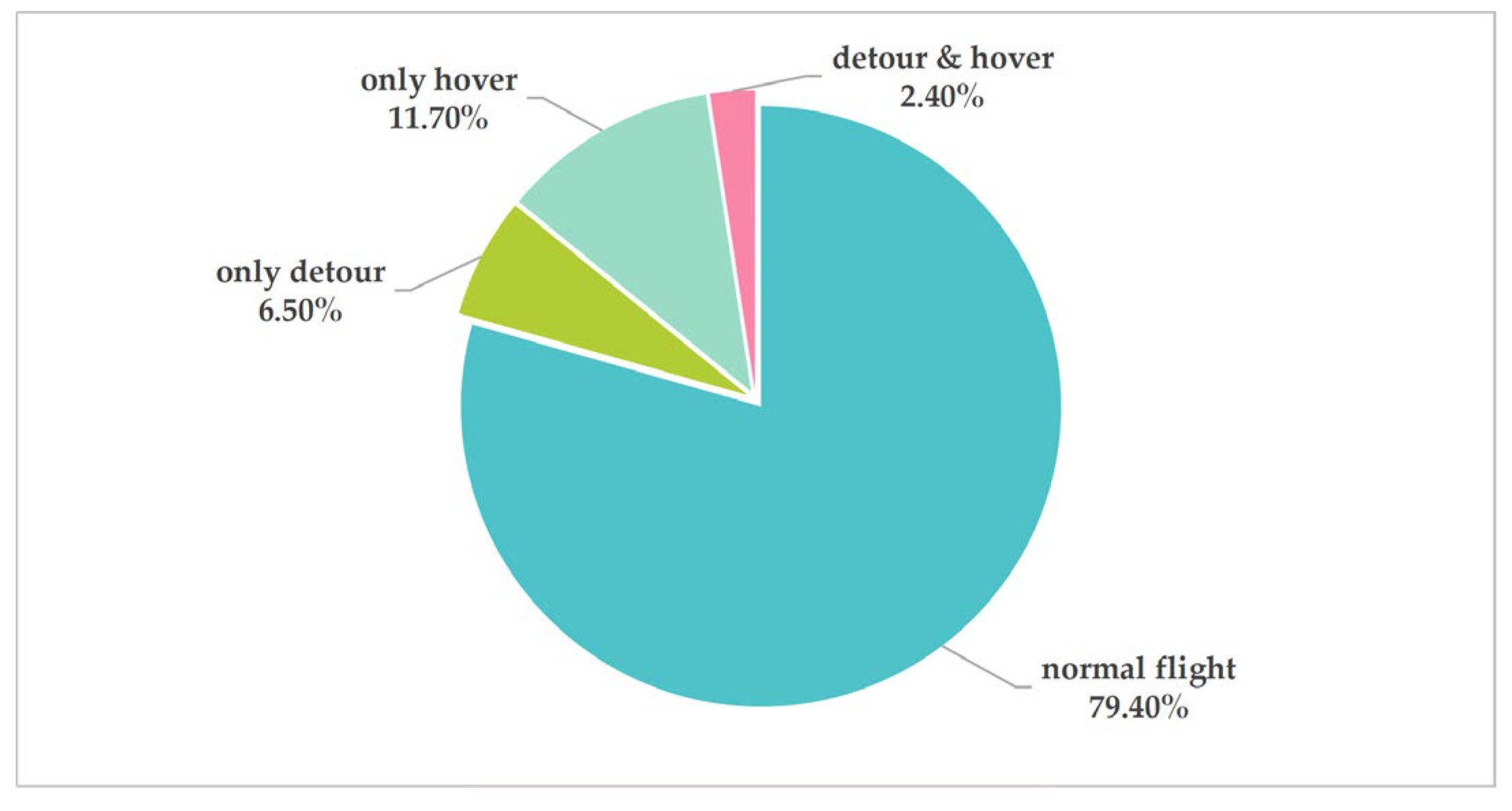

From the perspective of mission distribution by flight strategy (

Figure 9), the proposed safety control framework was activated selectively rather than ubiquitously across missions. Among all simulated UAVs, 8.9% UAVs triggered detouring behavior, 14.1% UAVs executed hovering at least once during their missions, while missions executing both strategies concurrently accounted for only 2.4%. This distribution indicates that most missions can be completed without invoking complex avoidance actions, and that the proposed security policy intervenes only when local risk levels exceed predefined thresholds. Such selective activation demonstrates that the system prioritizes maintaining nominal flight efficiency while retaining the capability to promptly mitigate elevated ground risks when necessary.

- (2)

Detouring behavior and spatial efficiency impact

The characteristics of spatial risk avoidance are further reflected in the detouring behavior statistics. Among UAVs performing detours, the average additional flight distance was 2466 m, while the maximum detour distance reached 6960 m in the worst-case scenario. The gap between the average and maximum values suggests that extreme detouring occurred only in a small number of missions, likely under highly constrained spatial conditions. Overall, the moderate average detour distance indicates that most rerouting actions were spatially limited, allowing UAVs to bypass high-risk zones without inducing excessive deviations from their original flight paths.

- (3)

Hovering behavior as a lightweight temporal buffer

Hovering was triggered by a larger number of UAVs compared to detouring; however, its temporal cost remained limited. The average cumulative hovering duration per UAV was only 12.3 s, with a maximum hovering time of 77 s. These results indicate that hovering primarily served as a short-term temporal buffer rather than a prolonged holding strategy. In most cases, UAVs were able to resume flight shortly after transient risk levels subsided, demonstrating the system’s ability to respond efficiently to short-lived crowd dynamics without incurring significant delays or energy overhead.

- (4)

Path replanning frequency and system stability

The frequency of path replanning further reflects the stability of the proposed security policy. On average, each UAV performed only 1.08 replanning events, with a maximum of two replanning events observed across all missions. This low replanning frequency indicates that the system does not suffer from oscillatory behavior or excessive trajectory adjustments when responding to dynamic crowd risks. Instead, risk mitigation decisions tend to converge rapidly, preserving both operational stability and computational efficiency.

- (5)

Combined Detouring and Hovering Under Persistent High-Risk Condition

Some missions simultaneously required detours and hovering, indicating that high-risk zones exhibit persistence and spatial chain reactions. Due to the long-term presence of dense crowds along marathon routes—such as at starting/finishing points, aid stations, and critical sections—even after detours, alter-native flight paths may still overlap with crowds, forming continuous strip-like high-risk zones that maintain elevated risk levels for extended periods. This re-quires drones to hover and wait during subsequent flight segments to avoid new risks after completing a detour. This phenomenon not only reflects the spatiotemporal stability of risk zones but also underscores the importance of implementing dynamic risk assessments and safety control strategies in the context of such activities.

Overall, this strategy reduces the probability of drones entering high-risk zones and shortens exposure time to hazards. Although flight duration and distance increase for some missions, the costs remain within acceptable limits while ensuring public safety. The simulation results demonstrate the strategy’s robust adaptability, enhancing mission completion rates and preventing numerous mission aborts. Additionally, high-risk zones exhibit localized clustering and periodic outbreaks, providing valuable insights for optimizing dynamic scheduling of aerial networks in future applications. In future work, the proposed framework can be extended to larger-scale simulations with 1000–5000 missions to investigate airspace capacity under risk-aware detour and hovering strategies, as well as their implications for UAV energy consumption.

Figure 9.

Pie chart of task proportions under different flight strategies.

Figure 9.

Pie chart of task proportions under different flight strategies.

4.4. Safety Benefits and Efficiency Costs of the Proposed Control Strategy

This section quantitatively evaluates the safety improvements achieved by the proposed safety control strategy and the associated impacts on flight efficiency. By comparing the baseline scenario with the controlled scenario, the trade-off between risk reduction and additional time and distance incurred during flight is systematically examined.

4.4.1. Safety Benefits: Reduction in High-Risk Exposure

To quantify the safety improvement, two indicators are defined: the reduction rate of cumulative high-risk exposure time and the reduction rate of high-risk segment crossings.

The reduction rate of cumulative high-risk exposure time is defined as follows:

where

denotes the cumulative duration during which a UAV trajectory is exposed to high-risk zones (risk levels I–III).

Similarly, the reduction rate of high-risk segment crossings is defined as follows:

where

represents the total number of flight segments classified as high risk that are traversed during mission execution.

Compared with the baseline scenario using conventional path planning, the proposed safety control strategy achieves a reduction of 49.1% in cumulative high-risk exposure time and 32.3% in high-risk segment crossings, indicating effective mitigation of both prolonged and repeated interactions with hazardous airspace regions.

4.4.2. Efficiency Costs: Time and Distance Expenditure

The safety improvements are achieved at the consumption of additional time and distance overheads caused by detouring and hovering behaviors. To quantify these effects, the relative increases in total flight distance and mission duration are defined as follows:

The system flight distance increase ratio is defined as follows:

where

denotes the total flight distance of a mission.

The system mission time increase ratio is defined as follows:

where

represents the total flight time of all UAVs required to complete their missions.

The results indicate that, at the system level, the total flight distance and cumulative mission duration increased by 2.26% and 0.35%, respectively. These increases remain moderate relative to the overall mission scale, suggesting that the proposed safety control strategy achieves risk mitigation without causing excessive system-level time or distance consumption.

4.4.3. Safety–Efficiency Trade-Off Analysis

To jointly assess safety gains and efficiency consumption, a safety–efficiency trade-off index is introduced. This index quantifies the relationship between the reduction in high-risk exposure and the combined increases in system-level flight distance and mission duration:

The index is defined as the ratio between the relative reduction in high-risk exposure time and the relative increases in system-level flight distance and mission duration. It quantifies the effectiveness of the proposed safety control strategy in converting additional flight time and distance consumption into tangible safety improvements. It serves as a system-level indicator of how efficiently additional flight consumption is transformed into safety gains.

Based on the simulation results, the safety–efficiency ratio reaches 18.8, suggesting that the reduction in high-risk exposure substantially outweighs the additional distance and time overheads introduced by risk-avoidance maneuvers. This demonstrates a favorable balance between enhanced operational safety and acceptable efficiency degradation.

Overall, the proposed safety control strategy achieves significant safety benefits while maintaining efficiency costs within a controllable range, supporting its applicability in low-altitude UAV operations over large-scale public events.

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Risk Model Parameters

To examine the robustness of the proposed risk-aware safety control framework and to address potential concerns regarding the linear formulation of the risk model, a quantitative sensitivity analysis was conducted on the core risk parameters. The dynamic risk score is formulated as a multiplicative index where K represents UAV-related factors, N denotes airspace traffic intensity, and S characterizes ground crowd density.

In the sensitivity analysis, each component was independently perturbed while all other model components, mission configurations, and safety control logic remained unchanged. Specifically, scaling factors of ±20% were applied to

K,

N and

S in a one-at-a-time manner, resulting in nine representative test cases. For each case, two scenarios were simulated under identical mission settings: a baseline scenario without safety control and a controlled scenario with the proposed detouring and hovering strategy activated. The performance of the safety control strategy was then evaluated by comparing key system-level metrics between the two scenarios. Detailed results are shown in

Table 8.

The results show that the proposed framework exhibits stable and consistent safety benefits under parameter perturbations. Across all sensitivity cases, the reduction in cumulative high-risk exposure time remains within a relatively narrow range, approximately between 39% and 47%, while the reduction in high-risk segment crossings varies between 17% and 32%. These variations reflect reasonable responsiveness of the control strategy to changes in risk weighting rather than instability or performance degradation. Importantly, no parameter configuration led to a loss of safety effectiveness or reversal of the observed safety gains.

From a system stability perspective, the average number of replanning events per replanning UAV remains close to one across all sensitivity cases. This indicates that the dynamic replanning mechanism does not exhibit oscillatory or excessive intervention behavior when the risk parameters vary, and that the safety control logic remains well-regulated under uncertainty. The limited sensitivity of the replanning frequency further suggests that the framework avoids overreacting to moderate changes in risk assessment.

Overall, the sensitivity analysis demonstrates that the effectiveness of the proposed safety control framework is not overly dependent on precise parameter tuning. The observed safety improvements persist under reasonable variations in all risk model components, supporting the robustness of the multiplicative risk formulation as a decision-making index in large-scale UAM operations over dynamic public events. The results indicate that the linear aggregation used in the risk model provides sufficient stability and interpretability for the intended application scope while maintaining consistent system-level safety benefits.

It should be noted that the proposed risk formulation adopts a linear aggregation of multiple risk components, which inevitably simplifies potential nonlinear interactions among ground risk, air traffic density, and crowd exposure. This limitation is acknowledged. However, the primary objective of the present study is not fine-grained probabilistic risk estimation, but classification-based, real-time risk awareness and decision triggering under dynamic operational conditions. Within this scope, the linear risk index provides a transparent, computationally efficient, and interpretable decision variable that supports timely risk level classification and rolling control.

4.6. Execution Characteristics Under Extended Mission Scale

4.6.1. Safety Control Execution Characteristics

To further examine the robustness of the proposed safety control framework under a larger mission scale, an extended simulation involving 1873 UAV missions was conducted using the same airspace configuration and risk modeling settings as in the previous experiments. Similar to the earlier mission-generation scheme, UAV tasks were randomly generated between arbitrary node pairs at one-minute intervals throughout the duration of the marathon event, resulting in a total of 1873 simulated missions.

Table 9 provides a quantitative comparison of safety, efficiency, and trade-off metrics under different mission scales (412 vs. 1873 UAV missions).

Overall, the proposed framework successfully processed the extended mission set of 1873 UAV missions without system-level failures. Safety control actions, including detouring and hovering, continued to be selectively triggered in response to detected high-risk zones, indicating that the control logic remains effective under a substantially larger number of concurrent missions.

From a safety perspective, the controlled scenario under the extended mission scale exhibited a clear and consistent reduction in both cumulative high-risk exposure time and high-risk segment crossings when compared with the corresponding baseline planning scenario. Specifically, the high-risk exposure reduction rate reached 35.9%, while the reduction in high-risk segment crossings was 24.8%. Although these relative reduction rates are lower than those observed in the 412-mission experiments, the results indicate that a substantial portion of high-risk exposure is still effectively mitigated in a significantly denser operational environment.

In terms of efficiency, the additional operational costs introduced by safety control actions remained moderate. The system-level flight distance increased due to detouring rose slightly to 2.50%, while the average mission time increase caused by hovering was limited to 0.43%, both remaining close to the levels reported under the smaller mission set. Moreover, the average number of replanning events per mission remained nearly unchanged (1.06 compared with 1.08), suggesting that the proposed framework does not induce oscillatory behavior or computational instability when applied at a larger scale. Meanwhile, the proportion of missions triggering safety control actions increased moderately to 23.55%, reflecting more frequent encounters with high-risk conditions as mission density increases while still preserving selective activation.

Taken together, the extended simulation results demonstrate that the proposed safety control strategy maintains stable execution characteristics and a favorable safety–efficiency balance under a significantly increased mission scale. The corresponding safety–efficiency trade-off ratio remains at 12.3, indicating that the achieved safety benefits continue to outweigh the associated efficiency costs.

Although both the relative reduction rate of high-risk exposure and the safety–efficiency trade-off ratio decrease under the extended mission scale, this behavior is expected in denser and more congested operational scenarios. As the number of missions increases, a larger proportion of flights inevitably operate closer to high-risk zones, thereby limiting the marginal risk reduction achievable through detouring and hovering. Importantly, the proposed framework continues to deliver substantial safety benefits while maintaining controlled efficiency costs, indicating that the observed decrease reflects realistic operational constraints rather than a degradation of the control strategy.

4.6.2. Endurance-Related Execution Characteristics

To further examine the endurance-related execution characteristics under extended mission scale,

Table 10 summarizes the statistical distributions of flight distance and mission duration obtained from the 412-mission and 1873-mission simulations under the full safety control scenario.

As shown in

Table 10, the endurance-related execution characteristics remain stable when the mission scale increases from 412 to 1873 UAV flights. The average flight distance increases only marginally, from 10.03 km to 10.29 km, while the average mission duration rises slightly from 8.37 min to 8.58 min. These results indicate that the introduction of additional missions does not significantly increase the typical endurance demand per UAV.

Regarding worst-case behavior, the maximum flight distance increases from 25.37 km to 31.03 km, and the maximum mission duration from 21.17 min to 25.87 min. This increase reflects the presence of a small number of extreme missions involving multiple detours and replanning actions under higher mission density. Importantly, these maximum values remain within the feasible operational envelope of commercial multi-rotor UAVs and do not represent the dominant mission profile.

It is worth noting that, under both the 412-mission and 1873-mission scenarios, no UAV reached the predefined maximum hovering time limit of 300 s. This observation indicates that the proposed safety control strategy rarely relies on prolonged hovering to mitigate risk. Instead, most high-risk situations are resolved through short-term waiting or spatial detouring as risk levels evolve over time. The absence of limit-reaching cases suggests that the chosen hovering threshold functions as a safety constraint rather than an active operational bound, and that the framework operates well within practical endurance margins.