A Morphing Land–Air Robot with Adaptive Capabilities for Confined Environments

Highlights

- A morphing wheeled land–air robot is developed by integrating a multi-link foldable arm mechanism and a variable-diameter wheel mechanism to achieve land–air mode switching, in-flight morphing, flexible dual landing strategies, and smooth transitions between wheeled and legged locomotion.

- The study systematically investigates the aerodynamic effects induced by the addition of wheels, evaluates the performance of the two morphing mechanisms, and validates the robot’s performance through comprehensive outdoor tests, including obstacle traversal and folded takeoff/landing.

- The proposed design greatly enhances mobility and flexibility across air and ground environments, reducing unnecessary takeoffs, lowering energy consumption, and improving overall reliability.

- The unique multi-modal architecture forms a unified aerial–ground operational framework, offering higher efficiency, stability, and robustness when navigating complex real-world environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Robot’s System Design

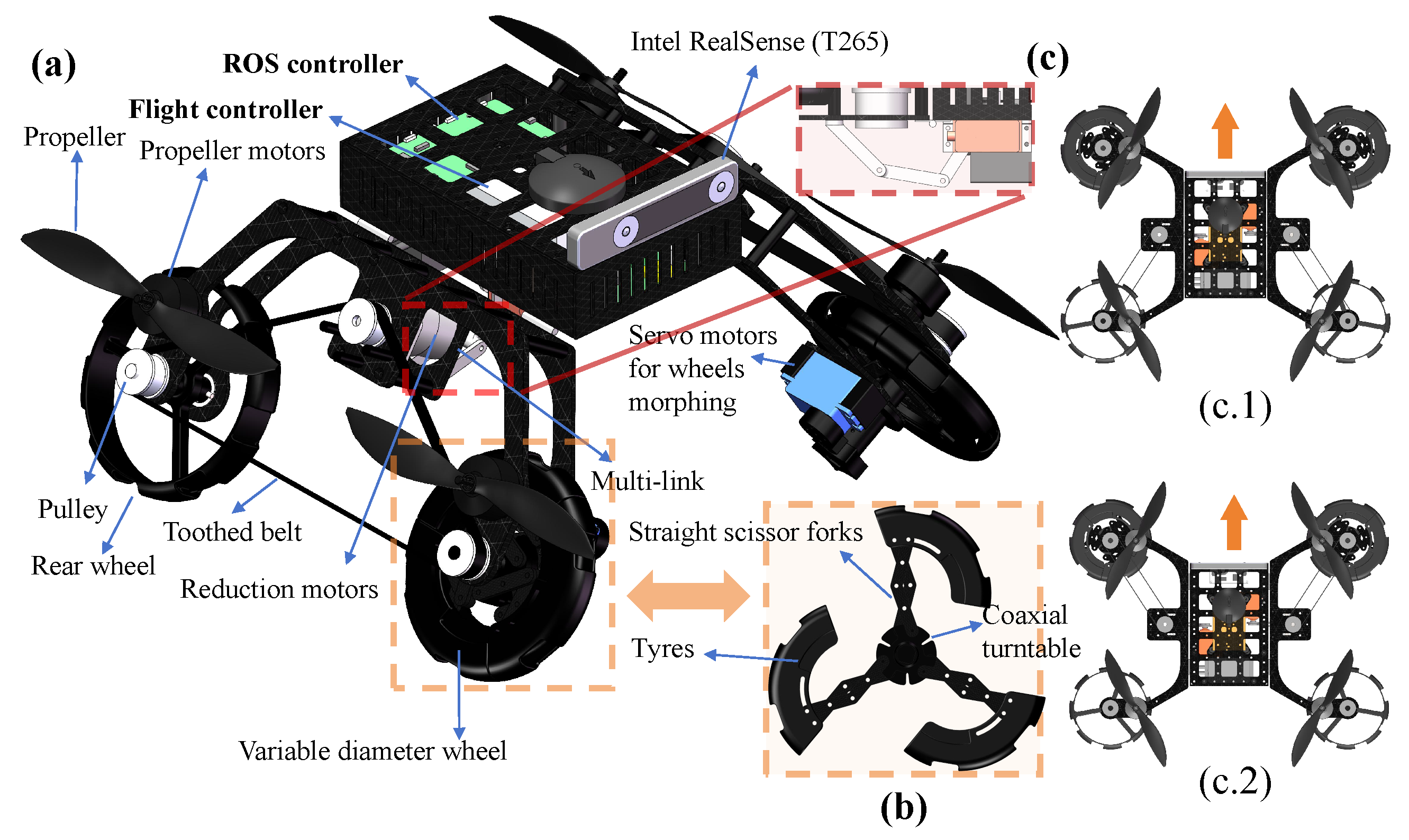

2.1. System Overview of the MW-LAR

2.2. Motion Mechanisms

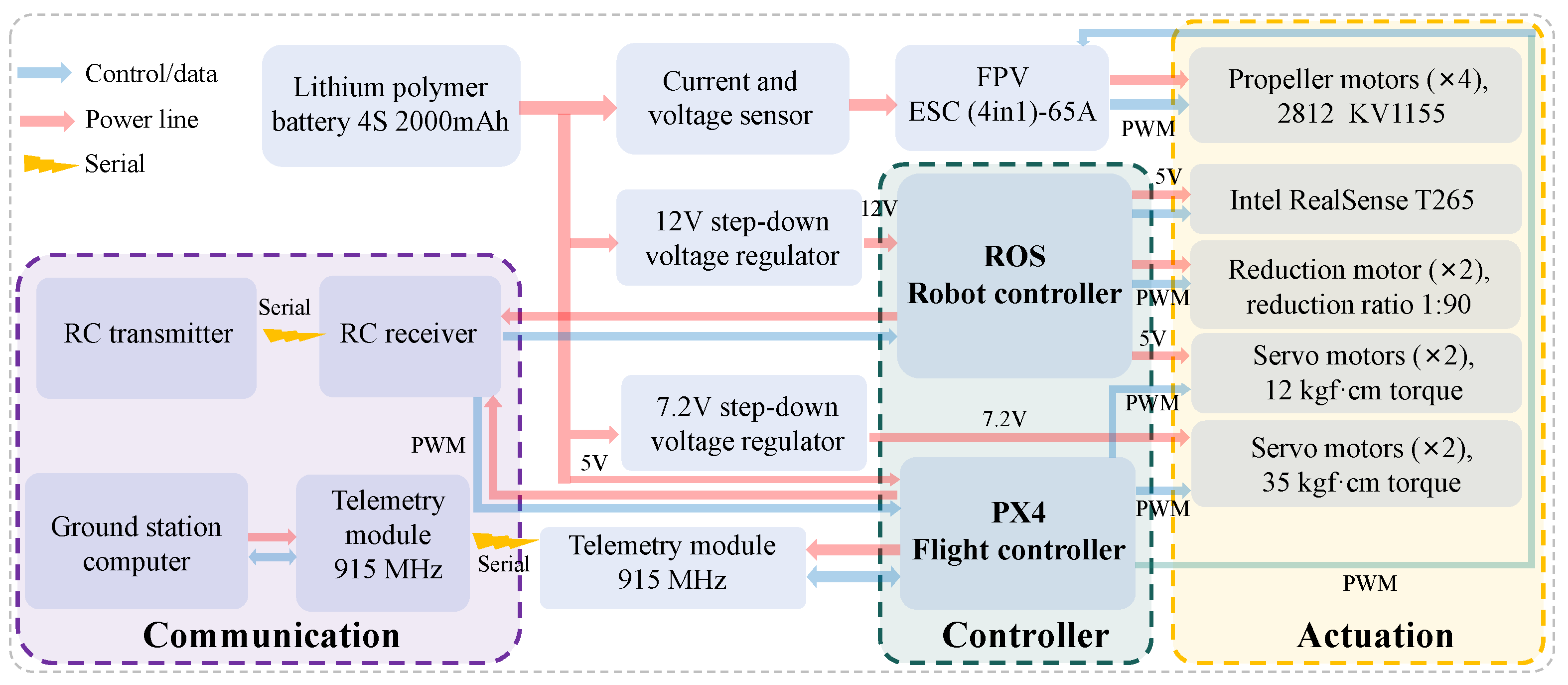

2.3. Actuation Mechanisms

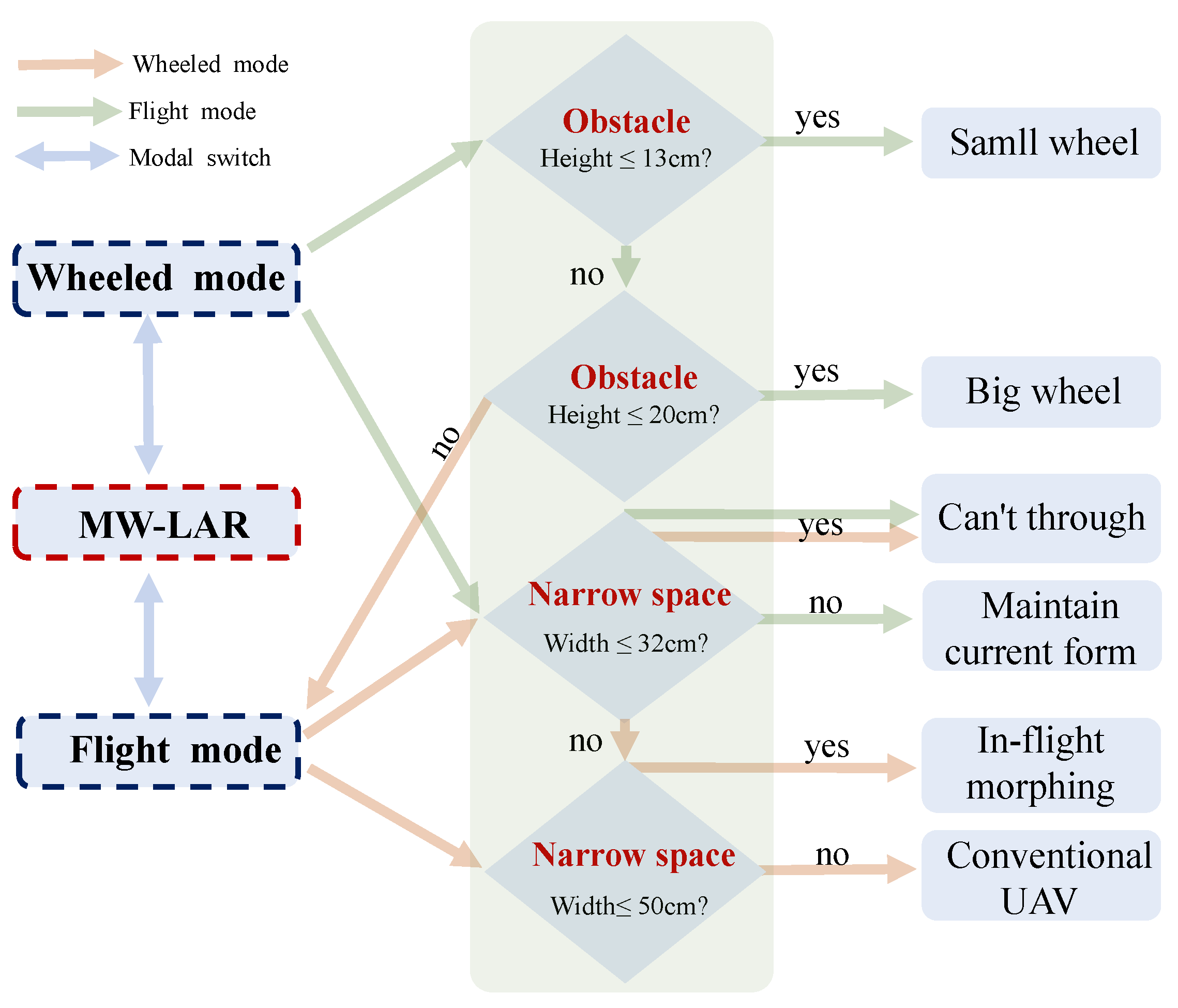

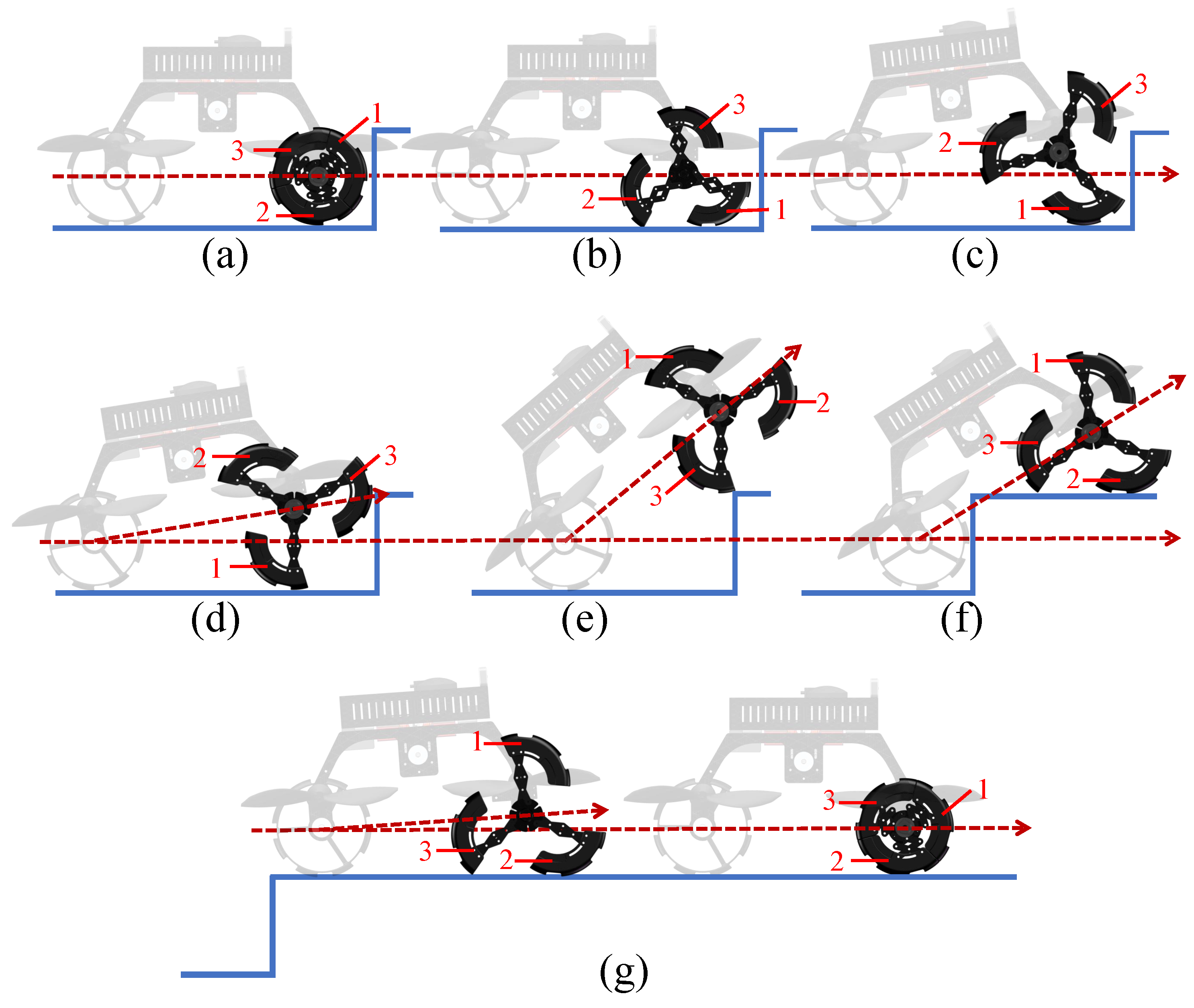

2.4. Overcoming Obstacles Strategy

3. Dynamic Modeling of the Robot

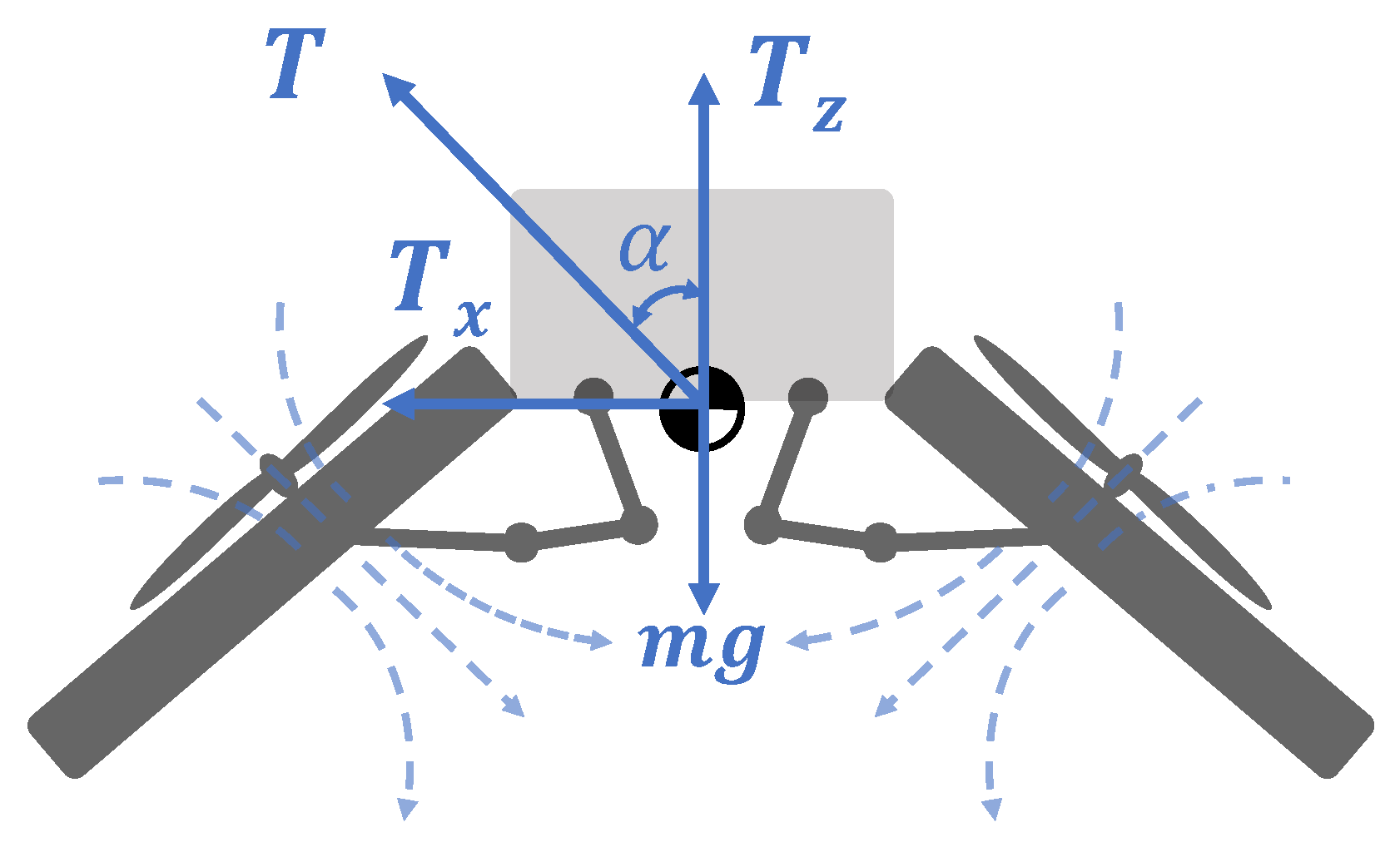

3.1. Dynamics in Flight Mode

3.2. Landing Force Analysis in Flight Mode

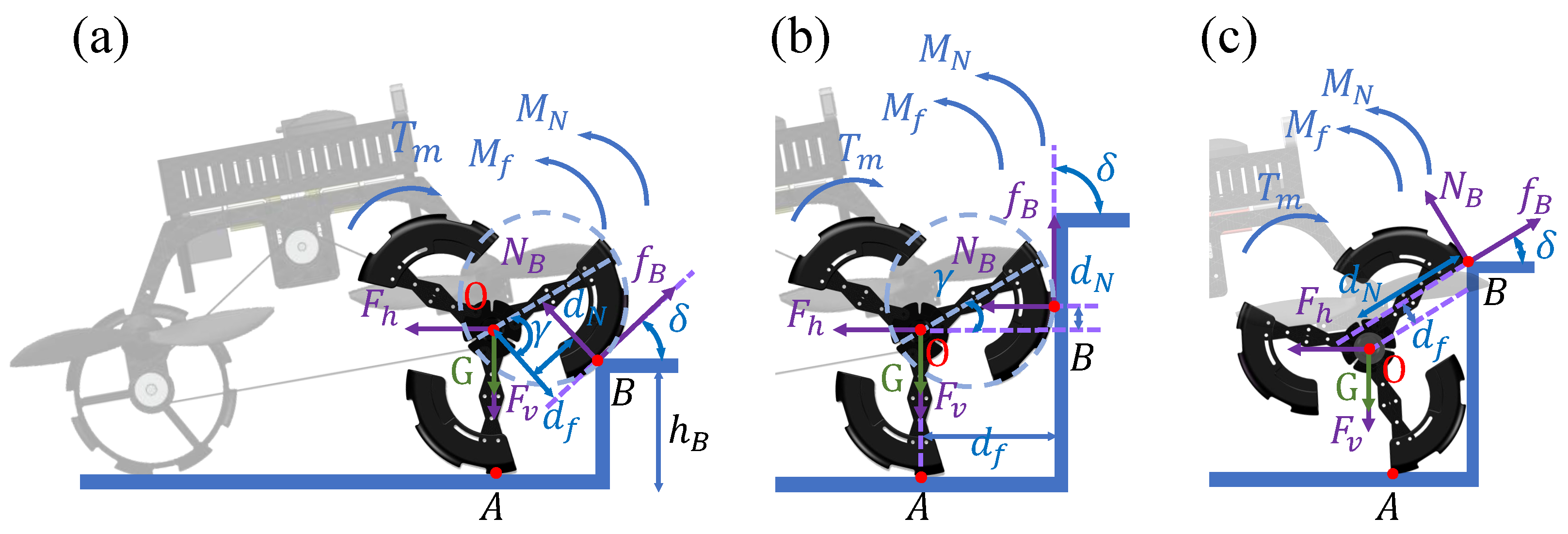

3.3. Obstacle-Crossing Force Analysis in Ground Mode

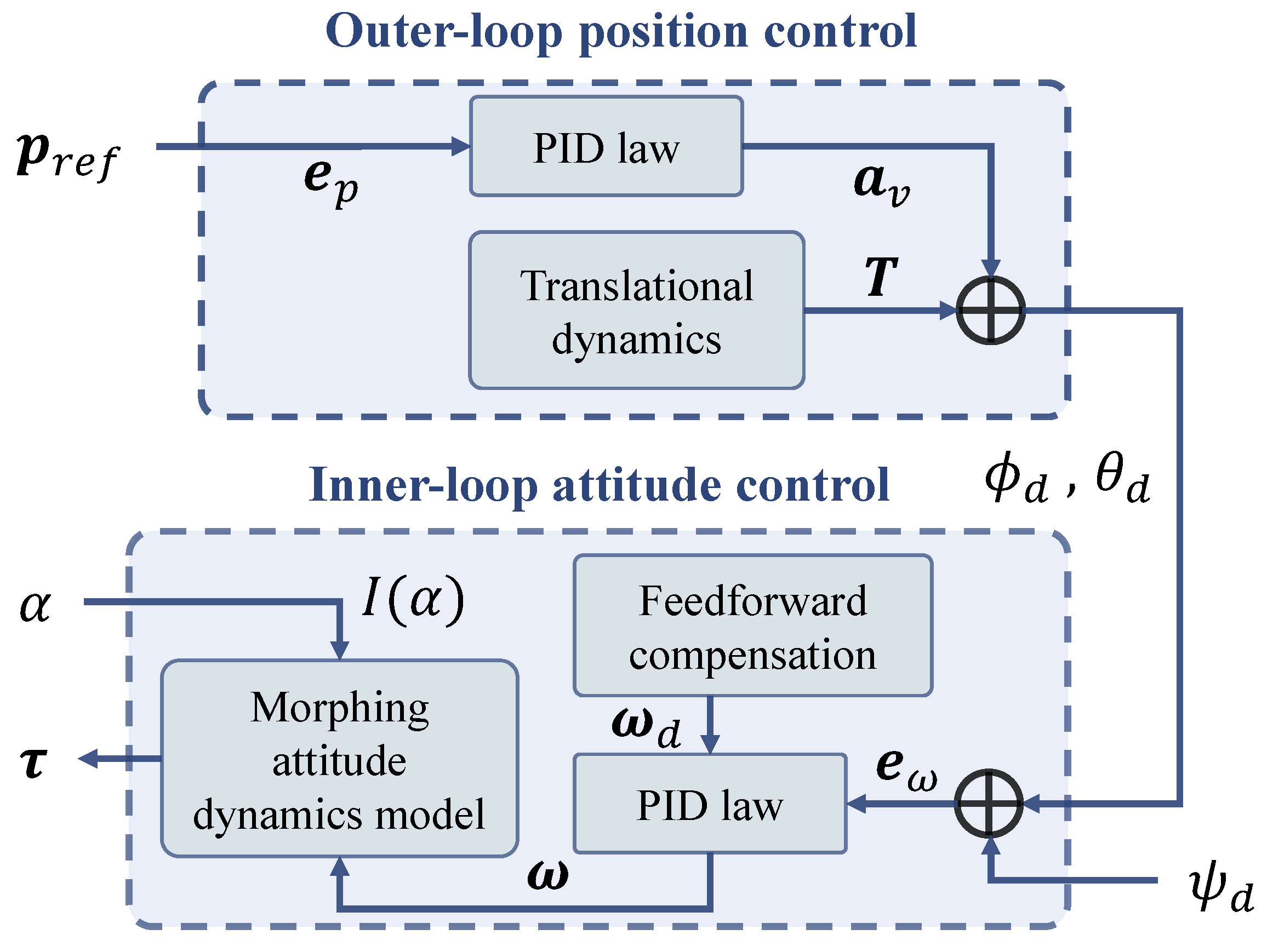

4. Control Design in Flight Mode

4.1. Outer Loop Control

4.2. Inner Loop Control

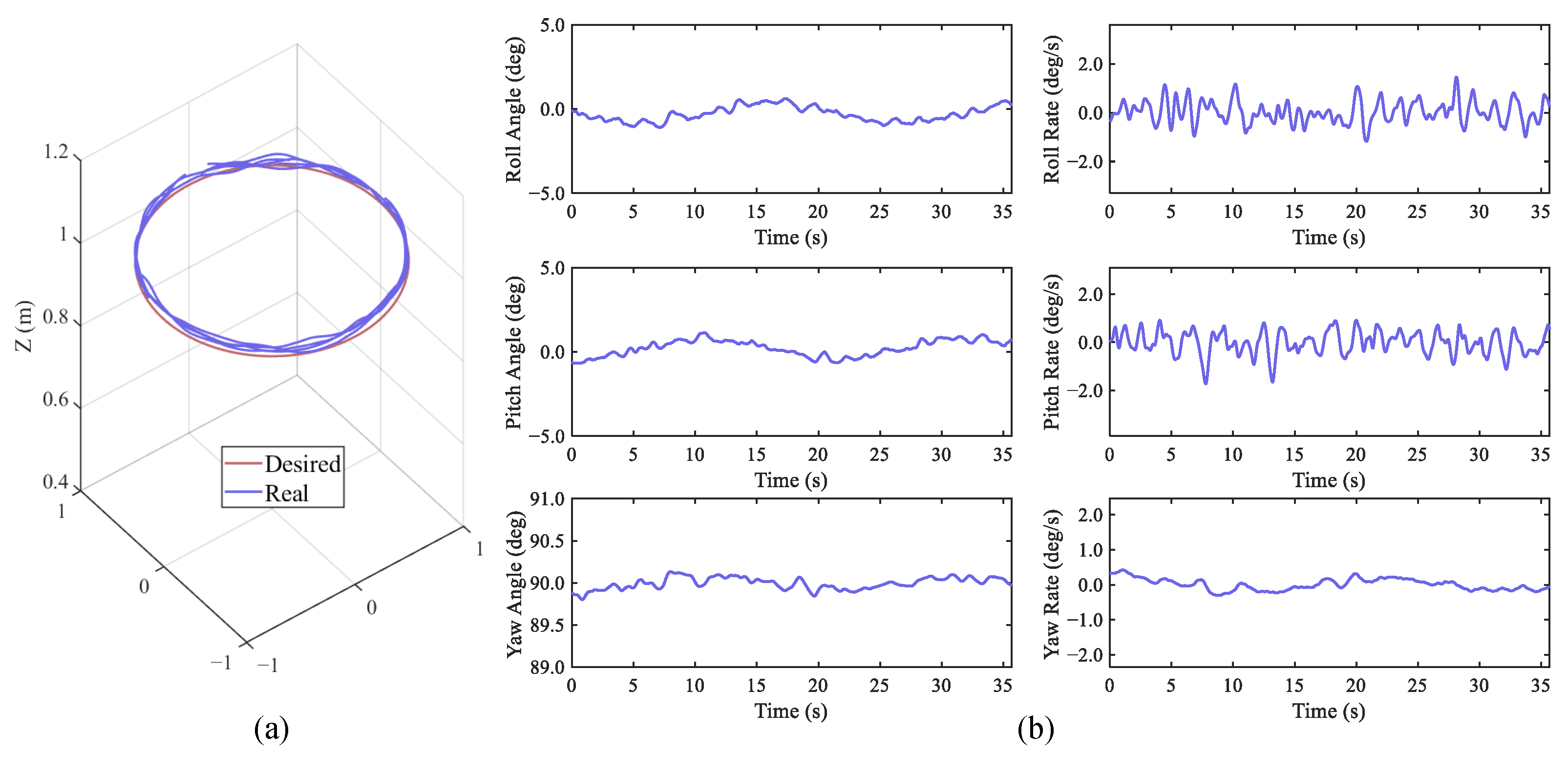

4.3. Simulation and Analysis

5. Experiments and Results

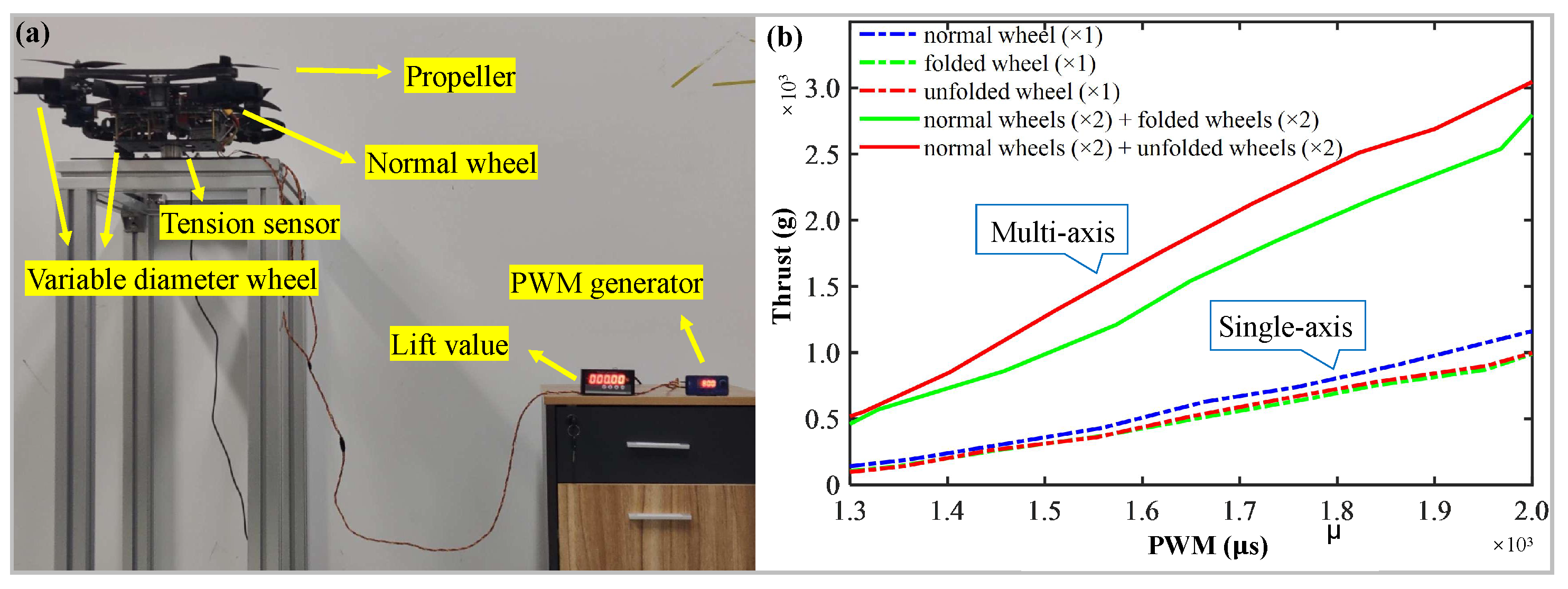

5.1. Investigation on the Influence of Wheels on Propeller Lift

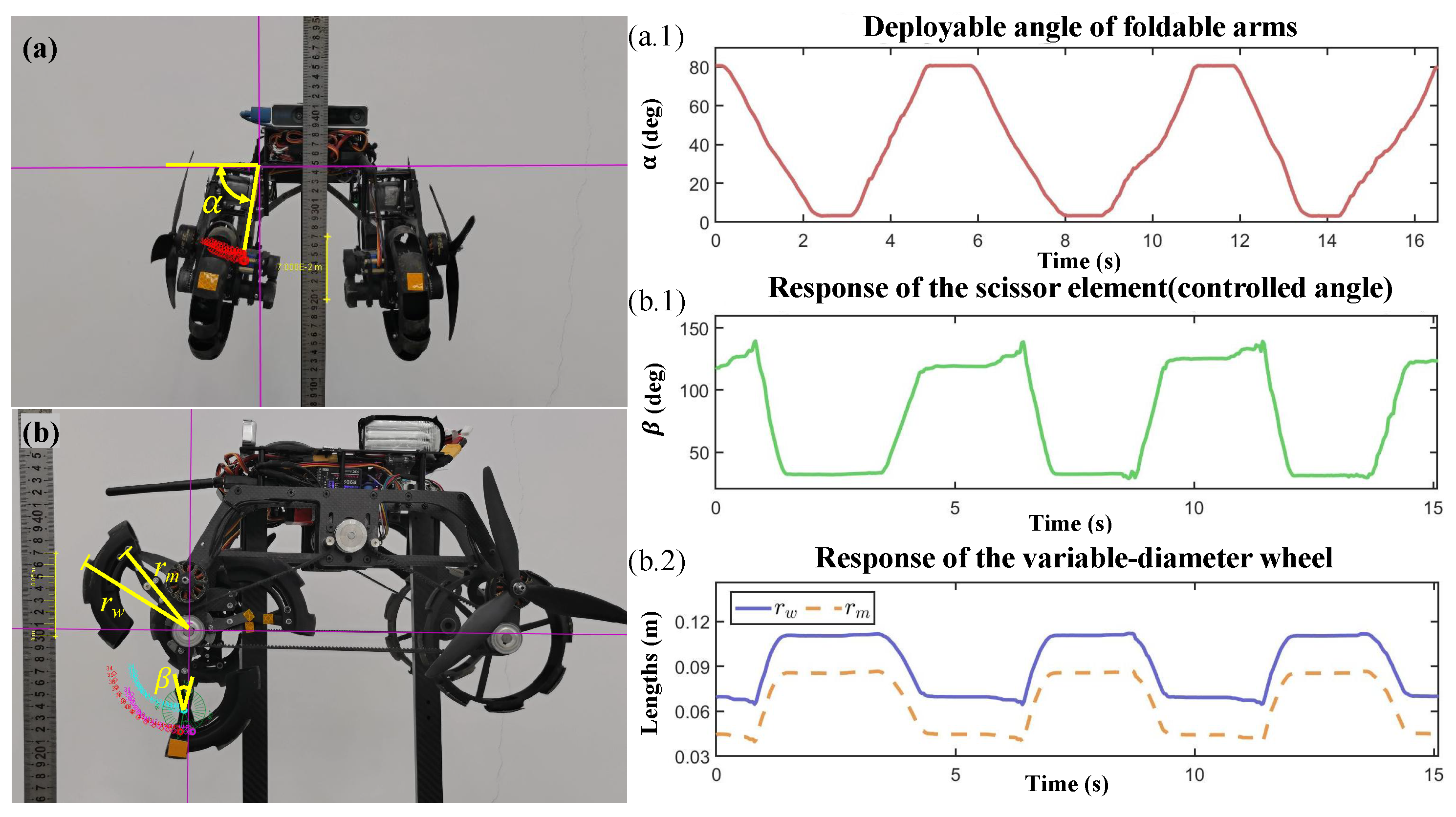

5.2. Performance of Foldable Arms and Morphing Wheels of the MW-LAR

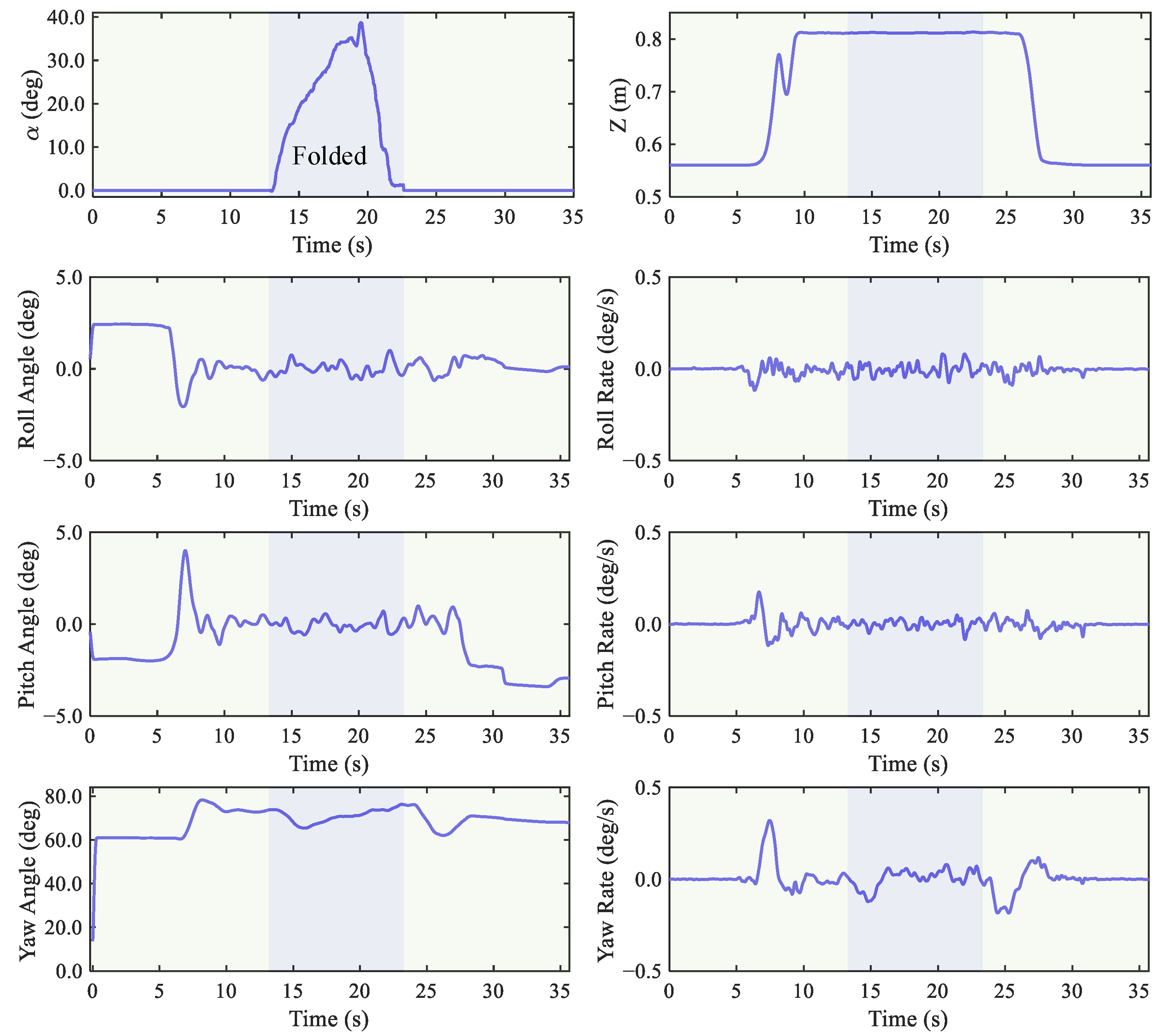

5.3. Bench-Top Flight Test of the MW-LAR

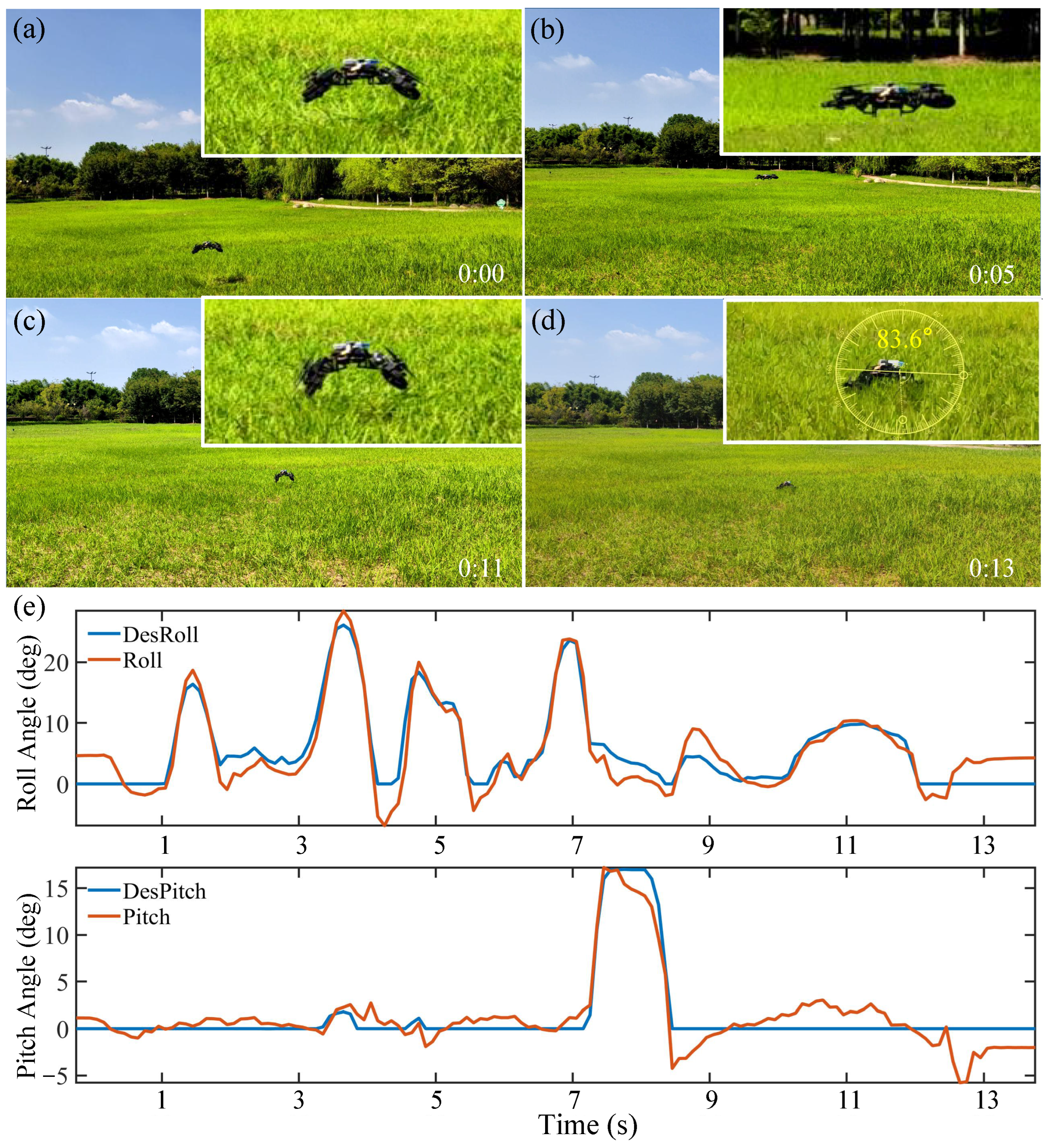

5.4. Traversal Performance Tests of the MW-LAR in Ground Mode

5.5. In-Flight Morphing Performance Tests of the MW-LAR

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, V.; Michael, N. Opportunities and challenges with autonomous micro aerial vehicles. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2012, 31, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; De, Q.; Yu, D.; Hu, A.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Biomimetic Morphing Quadrotor Inspired by Eagle Claw for Dynamic Grasping. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 2513–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, W.; Peng, C.; Wang, G.; Shen, Y. Comparative Validation Study on Bioinspired Morphology-Adaptation Flight Performance of a Morphing Quad-Rotor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5145–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Shen, Y. Minimum Snap Trajectory Planning and Augmented MPC for Morphing Quadrotor Navigation in Confined Spaces. Drones 2025, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Hu, J.; Xiang, C. Robust control in diagonal move steer mode and experiment on an X-by-wire UGV. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2019, 24, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihite, E.; Kalantari, A.; Nemovi, R.; Ramezani, A.; Gharib, M. Multi-Modal Mobility Morphobot (M4) with appendage repurposing for locomotion plasticity enhancement. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aucone, E.; Geckeler, C.; Morra, D.; Pallottino, L.; Mintchev, S. Synergistic morphology and feedback control for traversal of unknown compliant obstacles with aerial robots. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, T.; Basiri, M. BogieCopter: A Multi-Modal Aerial-Ground Vehicle for Long-Endurance Inspection Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 3303–3309. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, A.; Spenko, M. Design and experimental validation of HyTAQ, a Hybrid Terrestrial and Aerial Quadrotor. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6–10 May 2013; pp. 4445–4450. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Jiao, S.; Zhou, M.; Li, J. Multimodal dynamics analysis and control for amphibious fly drive vehicle. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Gao, F. Autonomous and adaptive navigation for terrestrial-aerial bimodal vehicles. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 3008–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, B.; Strang, J.; Pohorecky, S.; Qiu, C.; Naegeli, T.; Rus, D. Multi-robot path planning for a swarm of robots that can both fly and drive. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 5575–5582. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, A.; Touma, T.; Kim, L.; Jitosho, R.; Strickland, K.; Lopez, B.T.; Agha-Mohammadi, A.A. Drivocopter: A concept hybrid aerial/ground vehicle for long-endurance mobility. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Y.; Ding, Y. SytaB: A class of smooth-transition hybrid terrestrial/aerial bicopters. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 9199–9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Spieler, P.; Lupu, E.S.; Ramezani, A.; Chung, S.J. A bipedal walking robot that can fly, slackline, and skateboard. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabf8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, N.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, C.; Gao, F. Skywalker: A Compact and Agile Air-Ground Omnidirectional Vehicle. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2534–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.J.; Boria, F.J.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Ifju, P.G.; Quinn, R.D. A biologically inspired micro-vehicle capable of aerial and terrestrial locomotion. Mech. Mach. Theory 2009, 44, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintchev, S.; Floreano, D. A multi-modal hovering and terrestrial robot with adaptive morphology. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Aerial Robotics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 11–12 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, S.; Papanikolopoulos, N. A small hybrid ground-air vehicle concept. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 5149–5154. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, S.; Zhang, X.; Tian, J.; Xie, C.; Chen, Z.; Sun, J. Morphing Quadrotors: Enhancing Versatility and Adaptability in Drone Applications—A Review. Drones 2024, 8, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, O.; Honkavaara, E.; Botez, R.M.; Bayburt, D. Mechanisms and Control Strategies for Morphing Structures in Quadrotors: A Review and Future Prospects. Drones 2025, 9, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiri, N.; Zarrouk, D. Flying star, a hybrid crawling and flying sprawl tuned robot. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 5302–5308. [Google Scholar]

- David, N.B.; Zarrouk, D. Design and analysis of FCSTAR, a hybrid flying and climbing sprawl tuned robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 6188–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, E.; Zarrouk, D. Flying star2, a hybrid flying driving robot with a clutch mechanism and energy optimization algorithm. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 115491–115502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, O.; Zarrouk, D. Analysis of climbing in circular and rectangular pipes with a reconfigurable sprawling robot. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 173, 104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhao, N.; Luo, Y.; Long, S.; Luo, X.; Deng, H. A Multi-modal Hybrid Robot with Enhanced Traversal Performance*. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 6193–6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MW-LAR | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Robot size ( = ) | 394 × 504 × 125 mm |

| Robot size ( = ) | 394 × 300 × 259 mm |

| Deployment angle of the arm | |

| Deployment angle of scissors | |

| Wheel’s size | 65110 mm |

| Minimum traversal width | 255 mm |

| Minimum traversal height | 167 mm |

| Maximum folding angle during in-flight morphing | |

| Turning radius | 360° turn in place |

| In-flight morphing | Maintain stable In-flight Morphing |

| Average current during hovering ( = ) | 11 A |

| Average current (ground mode) | 0.2 A |

| Average current (folding on concrete floor) | 0.3 A |

| Instantaneous current during diameter change | 0.9 A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Deng, H. A Morphing Land–Air Robot with Adaptive Capabilities for Confined Environments. Drones 2026, 10, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010045

He Z, Zhao N, Wang Y, Sun C, Wang H, Luo Y, Deng H. A Morphing Land–Air Robot with Adaptive Capabilities for Confined Environments. Drones. 2026; 10(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhipeng, Na Zhao, Yongli Wang, Chongping Sun, Haoyu Wang, Yudong Luo, and Hongbin Deng. 2026. "A Morphing Land–Air Robot with Adaptive Capabilities for Confined Environments" Drones 10, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010045

APA StyleHe, Z., Zhao, N., Wang, Y., Sun, C., Wang, H., Luo, Y., & Deng, H. (2026). A Morphing Land–Air Robot with Adaptive Capabilities for Confined Environments. Drones, 10(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010045