1. Introduction

Driven by rapid advances in autonomous aviation and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technologies, the demand for high-precision, safe, and robust full flight-envelope control (covering takeoff, cruise, and landing) of fixed-wing aircraft has intensified [

1,

2]. Among these phases, takeoff and landing are the most critical and challenging, featuring strong nonlinear coupling between airframe dynamics and landing-gear–ground interactions, complex force transmission within three-point landing gear systems, and susceptibility to external disturbances such as crosswinds and uneven runways [

3,

4]. During the takeoff roll and touchdown, landing gear compression, friction, and normal-force distribution directly influence attitude stability; improper handling may lead to structural impacts, lateral skidding, or mission failure [

3,

5].

Accurate landing gear modeling is fundamental to effective control. Wu et al. [

3] proposed an elastic structural dynamics model based on Hamilton’s variational principle, enabling analysis of stochastic landing responses. Xin et al. [

4] developed a three-dimensional ground-taxiing model incorporating tire-friction characteristics, underscoring the importance of integrating landing gear effects into control design. Early work by Yan and Wu [

6] addressed taxi modeling and takeoff control for UAVs, laying the groundwork for ground-phase dynamics. Wang et al. [

7] examined key factors in ski-jump takeoff, including landing gear buffering and deck wind fields, highlighting the need for coupled airframe–gear control. He et al. [

2] established a longitudinal dynamic model for UAV taxiing takeoff, partitioning the process into three phases and emphasizing phase-adaptive control strategies.

In response, a variety of control methods have been proposed for takeoff and landing. High-fidelity modeling has been leveraged to enhance ground-phase control: Liang [

8] introduced a CFD-based automatic takeoff ground-roll controller; Wang et al. [

9] combined detailed ground-motion modeling with adaptive backstepping for large UAVs to compensate taxiing disturbances. Classical proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control and hierarchical strategies (e.g., MPC–PID coordination) remain prevalent for their simplicity and engineering practicality [

10,

11]. Pan et al. [

12] designed a longitudinal–lateral hierarchical controller integrating PID and MPC, improving landing trajectory tracking. Dong et al. [

10] proposed an MPC–PID coordinated method for carrier-based landing, enhancing robustness against air-wake disturbances. Recent advances include fault-tolerant MPC for actuator failures [

13], deep vision-based marker tracking [

14], fixed-time anti-saturation control [

15], and adaptive terminal sliding-mode techniques [

16]. Particularly for ground-operation uncertainties, Wu et al. [

17] developed an adaptive robust optimal control framework that combines LQR, sliding-mode control, and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference to address parametric uncertainties. Nonetheless, many methods treat longitudinal and lateral dynamics separately or rely on gain scheduling across discrete phases, lacking real-time perception of ground-contact states and adaptation to landing gear load variations [

18,

19]. Nonlinear control techniques such as nonlinear dynamic inversion (NDI) and backstepping have also been applied: Lungu [

18] designed an automatic landing system using backstepping and NDI to handle external disturbances but neglected airframe–gear coupling; Lungu et al. [

19] combined H2/H-infinity control with NDI to improve disturbance rejection while still overlooking phase-specific dynamics. Robust adaptive strategies [

20] and post-stall NMPC [

21] show promise yet do not incorporate ground-contact dynamics.

Extreme operating conditions—such as crosswinds during takeoff and landing and uneven runways—pose additional challenges. Emerging approaches include wind-preview MPC for forced landing [

22], eVTOL design-trajectory co-optimization [

23], and helicopter ground-force feedback [

24]. Castilho et al. [

24] employed Systems-Theoretic Process Analysis to identify hazards in crosswind takeoffs, underscoring the necessity of robust disturbance compensation. Tourajizadeh et al. [

5] proposed a robust optimal controller to mitigate nose landing gear shimmy, highlighting the centrality of landing gear stability control. Liang et al. [

25] developed a path-tracking controller for skid-equipped aircraft, addressing yaw stability but focusing on specific gear types rather than general three-point configurations. Xin et al. [

26] addressed longitudinal decoupling for altitude and velocity regulation. Overall, current control frameworks—whether classical or advanced—tend to target specific flight phases (e.g., landing) or overlook the synergy between attitude stabilization and landing gear load distribution, complicating balanced performance across the full flight envelope [

2,

27].

Although several representative studies [

6,

8,

9,

17] have advanced ground-phase modeling and control, they primarily target isolated phases (e.g., ground taxiing in [

6,

8] or the takeoff roll in [

9,

17]) with control objectives confined to ground trajectory tracking. More importantly, their adaptive or robust mechanisms—whether fuzzy rule–based [

6], data-driven neuro-fuzzy inference [

17], or disturbance estimation within backstepping [

9]—treat ground interactions and uncertainties as generalized disturbances to be compensated, rather than exploiting explicit, real-time physics from high-fidelity landing-gear models. This decouples the control design from the precise physical coupling between the airframe and the landing gear. To address these gaps, this paper proposes a landing-contact-aware adaptive nonlinear dynamic inversion (GCA-ANDI) controller for full flight-envelope control of fixed-wing aircraft. Unlike conventional methods [

10,

12,

15,

16,

18,

27] and recent phase-specific approaches with decoupled adaptation strategies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

17], GCA-ANDI integrates real-time ground-contact perception with adaptive NDI to provide a unified control architecture that jointly regulates a 12-dimensional airframe state (e.g., roll, pitch, yaw, and their angular rates) and manages landing-gear loads (nose/main wheel compression, normal force, and longitudinal/lateral friction) across takeoff, cruise, and landing. The key innovations are as follows: (1) a ground-contact perception module that monitors landing gear–ground interaction in real time—drawing on modeling insights from refs. [

2,

3,

4])—to enable phase-adaptive control switching across taxiing, takeoff, climb, cruise, descent, and landing; (2) a synergistic control framework that reconciles attitude stabilization with landing-gear load distribution, explicitly addressing the nonlinear coupling between airframe and landing-gear dynamics (unresolved by refs. [

12,

16,

19] and distinct from decoupled adaptive/robust schemes in refs. [

8,

9]); and (3) enhanced robustness to phase-specific disturbances (e.g., crosswinds [

23] and ground-induced moments [

5]) via integral action within the control loops and adaptive gain tuning based on direct physical-state feedback from the landing gear (e.g., strut compression λ, impact force N), rather than generalized disturbance estimation, enabling targeted performance such as shock absorption, impact mitigation and precise flight trajectory tracking.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 develops a full flight-envelope dynamic model incorporating airframe–landing-gear coupling;

Section 3 details the GCA-ANDI controller, including the ground-contact perception module and adaptive control laws;

Section 4 presents the simulation setup and comparative evaluations against benchmark methods;

Section 5 discusses the results and outlines directions for future work.

2. Aircraft Dynamics Modeling and Multiphysics Coupling

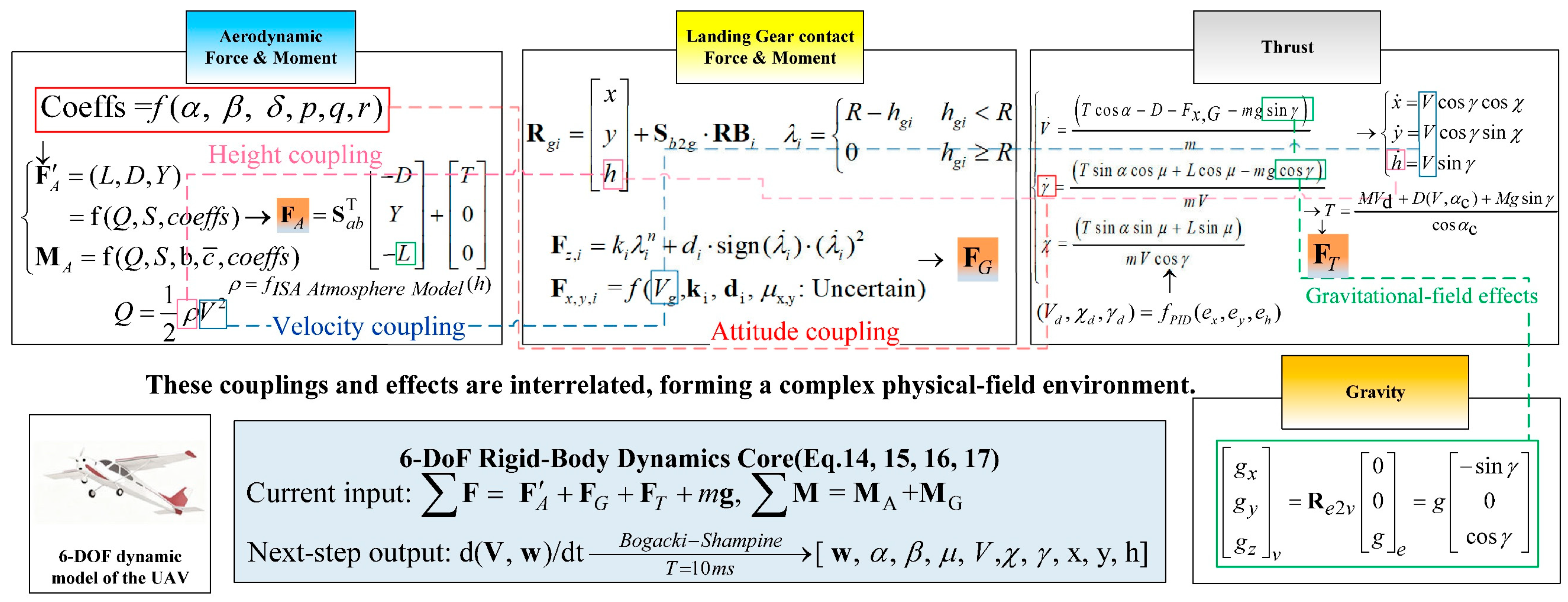

This chapter establishes a high-fidelity dynamic model for fixed-wing aircraft (as shown in

Figure 1) that incorporates an aerodynamic subsystem, a tricycle landing gear subsystem, and a six-degree-of-freedom rigid-body dynamics subsystem. The force and moment coupling mechanisms among the subsystems are elucidated, providing a physical basis for validating full-envelope control strategies.

2.1. Coordinate Systems and State Variables

A right-handed orthogonal coordinate system is employed to describe aircraft motion, with the core coordinate systems and state variables defined as follows:

Ground Coordinate System (E-frame, ): Origin is located at the runway threshold, extends forward along the runway, extends laterally to the right, and is vertically upward. This system is used to describe the aircraft’s position and ground speed.

Body Coordinate System (B-frame, ): Origin is located at the aircraft’s center of gravity, extends forward along the longitudinal axis of the fuselage, extends laterally to the right along the wing span, and is vertically downward, perpendicular to the plane (as per the American convention). This system is used to describe aerodynamic forces, moments, and angular velocities.

A 12-dimensional state vector

is defined to represent the aircraft’s motion state:

The state variables are defined as follows:

denote the angular velocities in the Body (B) frame (rad/s); are the angle of attack, side slip angle, and bank angle (rad), respectively; represents the true airspeed (m/s); stand for the course angle and flight path angle (rad), respectively; are the horizontal positions in the Earth (E) frame (m); is the altitude (m, where ).

2.2. Aerodynamic Model

During flight, the primary forces acting on the aircraft are generated by aerodynamic forces and moments, although other forces such as gravitational and thrust forces also play significant roles. The modeling is based on the aerodynamic coefficient method, accounting for the coupling effects of angle of attack

, sideslip angle

, control surface deflections, and angular velocities. The angle of attack and sideslip angle are defined by the B-frame velocity components

:

where

denotes the true airspeed. Aerodynamic coefficients can be fitted via empirical formulas, incorporating dependencies on

,

, angular velocities

, and control surface deflections

(where

denotes the elevator,

the aileron, and

the rudder). The specific expressions are given as follows:

In these expressions, and are the drag and lift coefficients, respectively; is the side force coefficient; , , and denote the roll, pitch, and yaw moment coefficients, respectively. represents the mean aerodynamic chord, and is the wingspan. Dynamic pressure is defined as , where is the atmospheric density (obtained via altitude lookup tables or atmospheric models).

The aerodynamic forces (drag

, lift

, side force

) and moments (

) in the wind axis system are given as follows:

Using the transformation matrix

from the wind-axis frame to the body-axis frame, the aerodynamic forces in the wind-axis frame are converted to aerodynamic forces in the body-axis frame (B-frame):

The aerodynamic forces in the body-axis frame

need to be combined with the engine thrust

(along the

direction):

The aerodynamic moments in the body-axis frame are directly given by .

2.3. Dynamics Modeling of Tricycle Landing Gear

The installation coordinates of the landing gear in the B-frame are given by

(where

for the nose wheel,

for the left main wheel, and

for the right main wheel). The transformation matrix

from the body coordinate system to the ground coordinate system yields:

The height of the wheel center from the ground is given by

. Combining this with the wheel radius

, the compression

is defined as

The normal force consists of a nonlinear spring force and a damping force. The model for the nose wheel and the main wheels is the same, but with different parameters (the main wheels have higher stiffness):

where

is the stiffness coefficient,

is the damping coefficient,

is the nonlinear exponent, and

is the compression velocity. The longitudinal friction force (in the

direction) is opposite to the ground longitudinal velocity

and includes the contribution of the braking torque

:

where

is the longitudinal friction coefficient, and

is used to avoid division by zero. The lateral friction force (in the

direction) is driven by the sideslip angle

, with the main wheels being the primary contributors:

where

is the lateral friction coefficient (typically

). The total ground reaction force in the body-axis frame

and moments

are given by

(Here, is taken with a negative sign because its direction is consistent with the axis.)

2.4. Six-Degree-of-Freedom Rigid Body Dynamics Model

Based on the Newton-Euler equations, we integrate aerodynamic forces, landing gear forces, gravity, and thrust to establish the dynamics equations in the body-axis frame.

The acceleration of the center of mass in the body-axis frame is determined by the resultant force:

where

is the aircraft mass,

is the airspeed vector in the body frame, and

is the angular velocity vector. The terms on the right-hand side of the equation represent aerodynamic forces

, ground reaction forces from the landing gear

(components defined by Equation (12)), thrust force

, and gravitational force in the body frame

.

The angular acceleration is determined by the resultant moment and the inertia matrix (considering the effect of the product of inertia):

Among them, the coefficients are as follows: , , , , , , , , ,

The aerodynamic angle kinetic equations are

Relationship between position and velocity (derivative of position in the E-system):

In the angular acceleration equations (Equation (15)), are the comprehensive moments generated by support forces and friction forces. For example, the roll angular acceleration is influenced not only by the roll moment caused by the vertical support force but also significantly by the roll moment caused by the lateral friction force.

During the landing phase, the longitudinal friction force of the main wheels generates a pitch moment through , which works together with the aerodynamic moment to adjust the pitch angular velocity . It is necessary to compensate for the coupling effects of these two types of moments in the control system.

3. Design of the GCA-ANDI Full Envelope Control System

This chapter focuses on designing a GCA-ANDI control system for fixed-wing aircraft to handle the multi-phase dynamic characteristics of full-envelope flight (including takeoff run, cruise, turn, descent, and landing). In particular, it addresses the strong coupling interference between landing gear friction, elastic forces, and aerodynamics during the takeoff run and landing phases. The system employs a layered architecture of “outer guidance, middle decoupling, and inner tracking” to achieve precise control and smooth transitions across various flight phases, while enhancing robustness to landing gear coupling interferences.

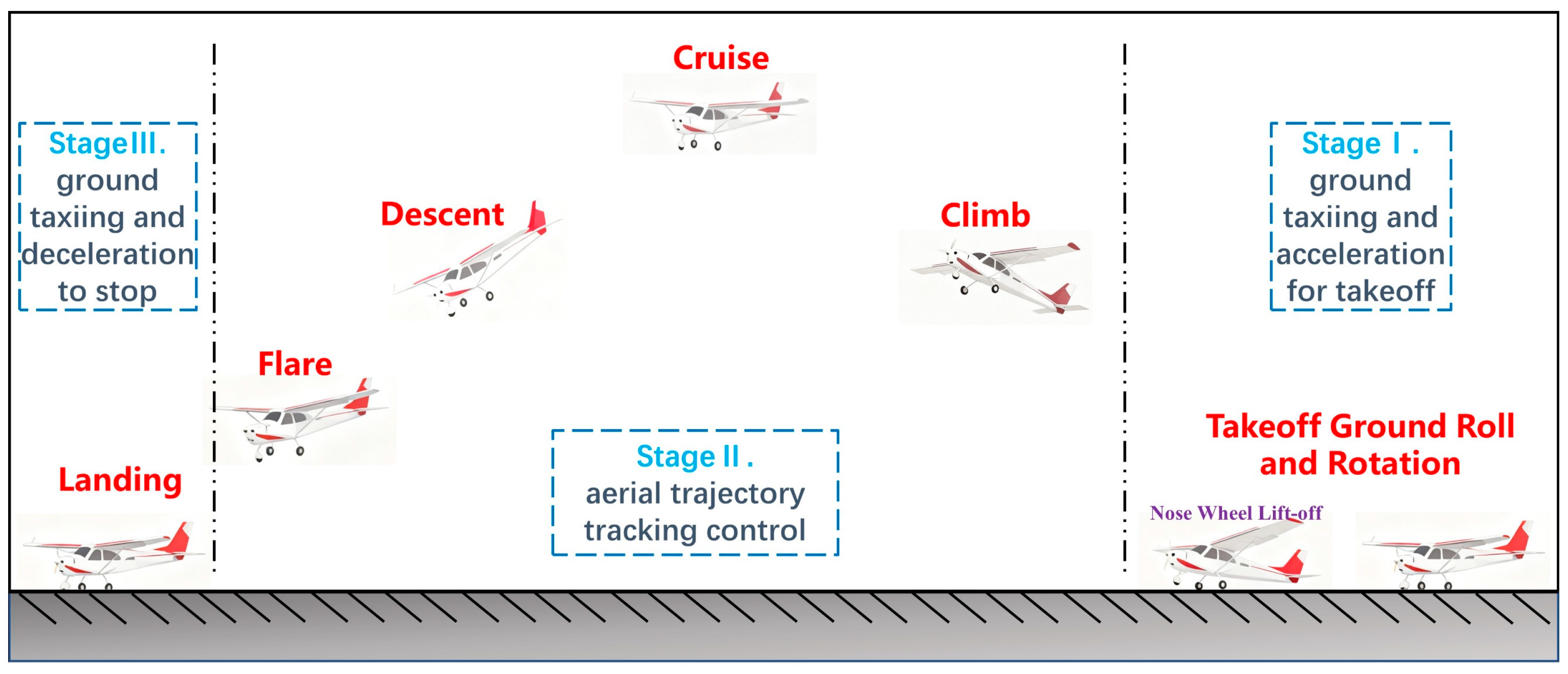

Figure 2 illustrates the longitudinal profile of the complete flight process.

3.1. Nonlinear Decoupling Ability of NDI

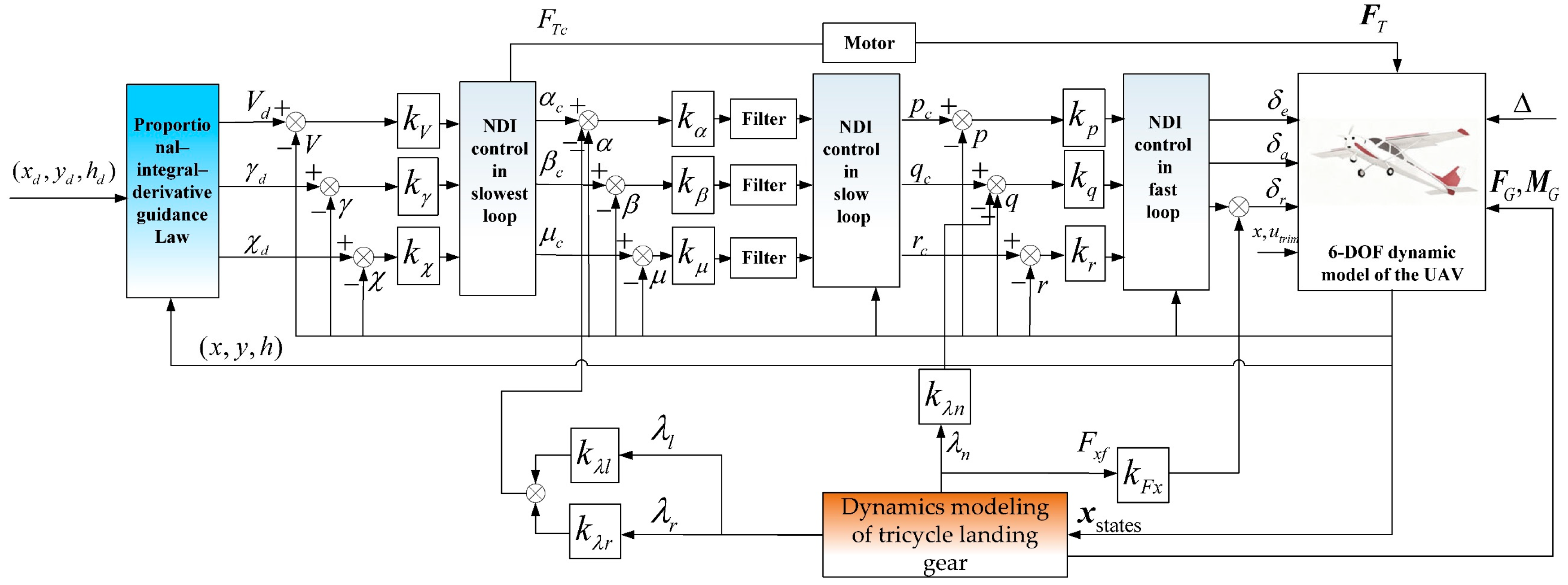

The nonlinear decoupling capability is utilized to separate the coupled effects of the aircraft’s pitch, roll, and yaw channels, especially to suppress the cross-interference of landing gear ground forces on the attitude channels: (I) The NDI strategy decouples the pitch, roll, and yaw dynamics, effectively isolating the interactions between these channels, which is crucial for maintaining stable and precise control during phases with complex dynamic interactions, such as the landing gear’s ground forces; (II) The integration of landing gear state feedback (compression amount, friction force) into the PID position loop and NDI loops to actively counteract ground disturbances; (III) Scheduling control gains based on flight phase characteristics (e.g., ground friction dominance during the taxiing phase, impact force dominance during the landing phase) to avoid control oscillations during phase transitions. The results of the proposed full-envelope adaptive UAV control system are shown in

Figure 3.

The system input consists of the desired flight trajectory (position commands

). The outputs are the engine thrust command

and the control surface deflection commands (aileron

, elevator

, rudder

). These commands are ultimately applied to the high-fidelity dynamic model established in

Section 2 to achieve closed-loop state tracking.

3.2. Guidance Layer PID Position Tracking Control

The guidance layer uses the desired position in the ground coordinate system, denoted as , as input and outputs commands for true airspeed , heading angle , and flight path angle , which serve as reference trajectories for the subsequent NDI decoupling loops. Here, represents the desired true airspeed, is the desired heading angle (the angle between the X-axis of the ground coordinate system and the projection of the velocity vector), and is the desired flight path angle (the angle between the velocity vector and the horizontal plane).

Longitudinal position tracking involves the coordination of altitude

and longitudinal distance

control. The altitude error is defined as

(where

is the actual altitude), and a PID controller generates

to ensure altitude tracking accuracy. The expression for the PID controller is:

where

are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains for altitude control, respectively;

denotes the time derivative of the altitude error. Simultaneously, the longitudinal distance error is defined as

(where

is the actual longitudinal position), and a combination with the current flight path angle

generates

to avoid conflicts between altitude and distance tracking. The expression is

where

are the gains for longitudinal distance PID control;

is the reference speed (design speed during the cruise phase);

is the correction term for the longitudinal speed component, ensuring unbiased longitudinal speed tracking even during altitude changes.

Lateral position tracking takes the lateral error

(where

is the actual lateral position) as input and uses a PID controller to generate

. The expression is:

where

are the gains for lateral PID control. The values of these gains should consider both lateral response speed and stability, avoiding large sideslip angles

that could lead to roll coupling.

3.3. Outer Loop NDI Control for Speed and Flight Path Angle

The outer loop control law receives speed command

, heading angle command

, and flight path angle command

from the guidance layer. Through the maneuver command generator framework, it generates the desired angle of attack

, desired sideslip angle

, desired bank angle

, and thrust command

, thereby achieving dynamic decoupling control of speed and flight path angles. Considering the coupling effects of ground forces on the landing gear, the system dynamics can be described as

where

represents aerodynamic drag,

is the lift force,

is the longitudinal friction force from the landing gear, and

is the flight path roll angle (bank angle). The control law design begins with defining the error-driven terms:

The control inputs are adjusted using the following tracking gains

to achieve the desired performance. The bank angle command is calculated through the heading-flight path coordination relationship:

The angle of attack command is determined by jointly solving the lift requirement and moment equilibrium:

Thrust Command Generation Based on Velocity Tracking Requirements:

The sideslip angle command is set to

to maintain coordinated turns. This control structure ensures the desired closed-loop dynamics:

The tracking errors

,

, and

are designed to satisfy

, achieving global exponential convergence. Aerodynamic forces

and

are updated via real-time estimators, modeled as

and

, where

and

are the aerodynamic coefficients defined in

Section 2. The command limits are set for practical implementation:

to prevent stalling and

to avoid excessive bank instability. Ground friction variations are explicitly compensated through a feedforward term

.

3.4. Mid-Loop NDI Aerodynamic Angle Control

The mid-loop uses the outer loop outputs

as inputs and outputs the desired angular velocities

, ensuring rapid tracking and decoupling of aerodynamic angle channels. The mapping between the rate of change in aerodynamic angles and angular velocities is given by:

where

To track the airflow angle command, Equation (28) is inverted to obtain the desired angular rates

,

,

:

3.5. Inner-Loop NDI Angular Velocity Control

The inner loop, using the mid-loop outputs

as inputs, outputs control surface deflection commands

, achieving precise angular velocity tracking via NDI. This is crucial for mitigating high-frequency disturbances such as landing gear impact forces. The angular velocity tracking control is based on the angular velocity equations from Equation (15). Using roll angular velocity

as an example, its dynamic equation is

Here,

represents the roll aerodynamic moment, related to control surface deflections by:

where

is dynamic pressure,

is wing area,

is wingspan,

is the aileron roll moment coefficient, and

is the rudder roll moment coefficient (other parameters are defined in

Section 2.2).

To track

, Equation (30) is inverted and combined with the aerodynamic coefficient model, yielding the control surface deflection mapping. Similarly, the pitch and yaw angular velocity equations are inverted, forming the control surface deflection command matrix:

where

is the mapping matrix between control surface deflections and moments, expressed as

Here, is the mean aerodynamic chord, is the elevator pitch moment coefficient, is the aileron yaw moment coefficient, and is the rudder yaw moment coefficient. are the time derivatives of desired angular velocities, is the angular velocity error correction gain, and are the pitch and yaw aerodynamic moments, respectively, with representing pitch and yaw landing gear ground moments.

3.6. Control Adaptation Strategy Based on Landing Gear Characteristics

In full flight envelope operations, the landing and takeoff phases are most significantly influenced by landing gear dynamics (with no ground forces during cruise and turns). Control adaptation strategies for these phases are designed by optimizing control law parameters using landing gear state feedback.

During takeoff roll, ground frictional force disturbance predominates, necessitating robust heading and velocity control. The longitudinal ground friction force

feedback is incorporated into the lateral PID guidance layer to adjust rudder deflection

for heading error suppression, as

where

is the base rudder command and

is the friction compensation gain. During the takeoff rotation phase, the nose wheel compression feedback

(refer to Equation (8) is incorporated to limit the maximum pitch rate

, preventing excessive nose wheel compression and tail strike risk. The pitch rate command is adjusted as

where

is the base maximum pitch rate, and

is the compression compensation gain.

During landing, the main landing gear impact forces dominate, requiring reduced ground impact load and minimized attitude oscillations. In the mid-loop attitude control, the main landing gear compression feedback

(left and right main wheel compressions) is used to adjust the desired angle of attack

to optimize the landing attitude. The desired angle of attack command is modified as

where

is the base desired pitch angle, and

are the main wheel compression compensation gains. In the inner-loop angular velocity control, the main landing gear impact forces

(refer to Equation (9)) are used to adjust the gain matrix

. If the combined impact force exceeds a threshold

, the angular velocity error correction gain

is increased to enhance damping and suppress attitude oscillations caused by the impact:

Then

where

is the base angular velocity error correction gain, and

is the additional gain to enhance damping.

4. Simulation Analysis and Control Performance Verification

In this chapter, we compare three control schemes: GCA-ANDI, cascade PID, and NDI. Simulation results confirm the superior performance of GCA-ANDI across the full flight envelope. No path-planning algorithms are included; the reference trajectory comprises simple step inputs or piecewise-linear segments. The 12-dimensional state vector is defined in Equation (1). The focus is on assessing the closed-loop tracking performance of the fixed-wing UAV throughout the flight and its effectiveness in rejecting ground disturbances. The parameters of the multi-coupled fixed-wing aircraft model used in this section are listed in

Table 1. Numerical simulations were conducted on a personal computer (Intel i9-13900H, 2.60 GHz, 40 GB RAM) with a control time step of 10 ms. The GCA-ANDI controller parameters are listed in

Table 2.

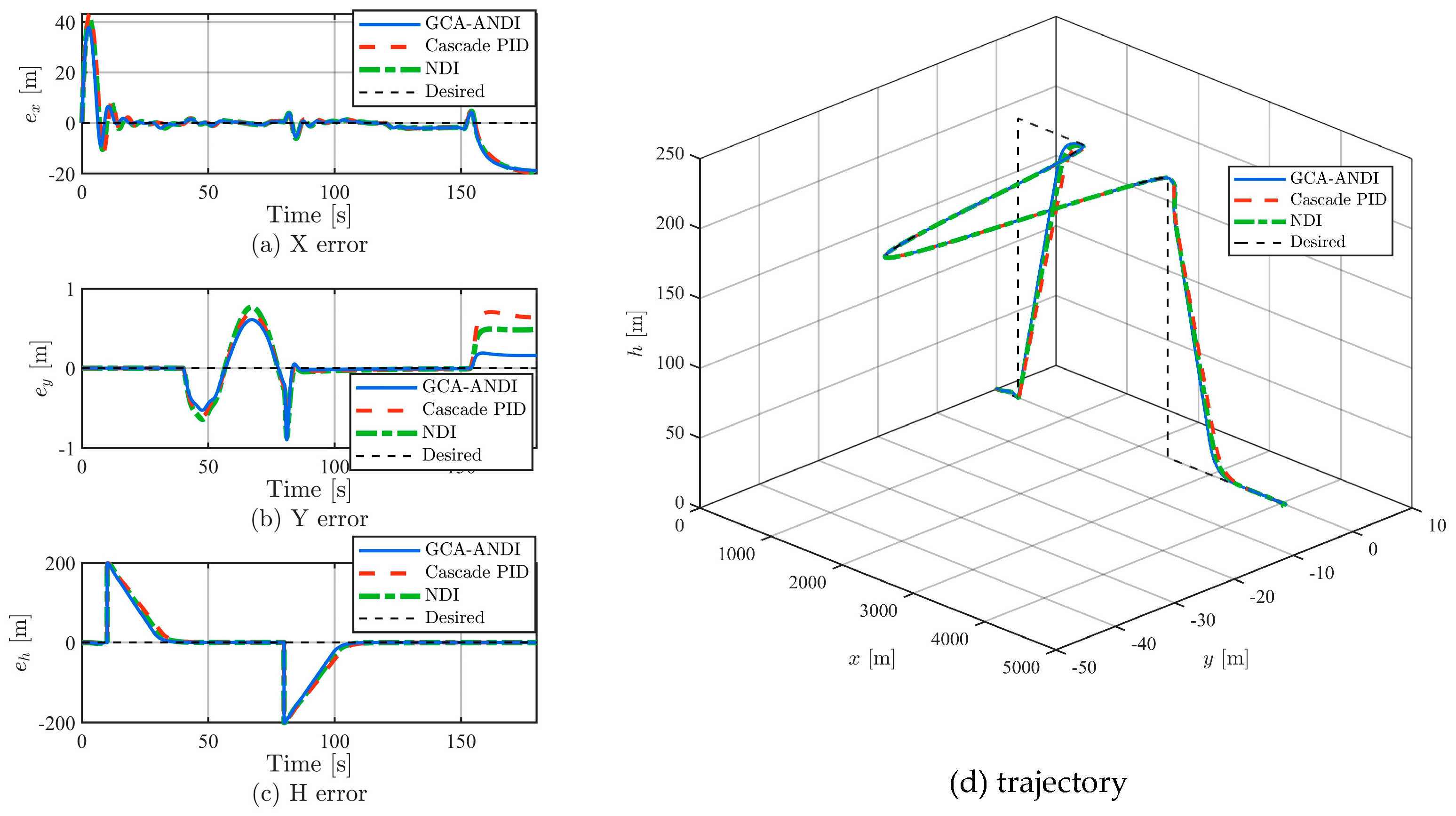

As shown in

Figure 4, GCA-ANDI performs excellently in three-dimensional trajectory tracking. Even with the presence of untrackable discontinuities in the reference trajectory, GCA-ANDI can still achieve dynamically feasible flight trajectories across the entire envelope, demonstrating robust adaptability and low dependency on complex trajectory optimization algorithms.

According to

Table 3, in x-direction position tracking, the root mean square error (RMSE) of GCA-ANDI is 7.9981 m, improving by 8.90% and 6.00% compared to cascade PID and NDI, respectively. Its ITAE metric also achieves the best performance, indicating lower cumulative error in longitudinal tracking. The improvement in the y-direction is particularly significant, with an RMSE of 0.2098 m, representing an enhancement of 30.21% to 36.40% compared to the other methods. During coordinated turns at constant altitude, GCA-ANDI effectively suppresses overshoot, reflecting its capability to manage trajectory commands and lateral friction.

In height tracking, the RMSE of GCA-ANDI is 57.0802 m (noting that transient errors at ascent and descent points can reach up to 200 m, this value indicates good performance). This represents an improvement of 7.38% and 3.93% compared to cascade PID and NDI, respectively. Analysis combined with

Figure 5 shows that, aside from inherent errors caused by physical limitations during the final ground roll, GCA-ANDI achieves better error convergence across the entire flight envelope through its adaptive nonlinear compensation mechanism. Despite the seemingly large RMSE in height, the tracking performance at non-discontinuous points is excellent, and the error curve rapidly converges to near zero after leaving discontinuous points, achieving superior trajectory tracking performance.

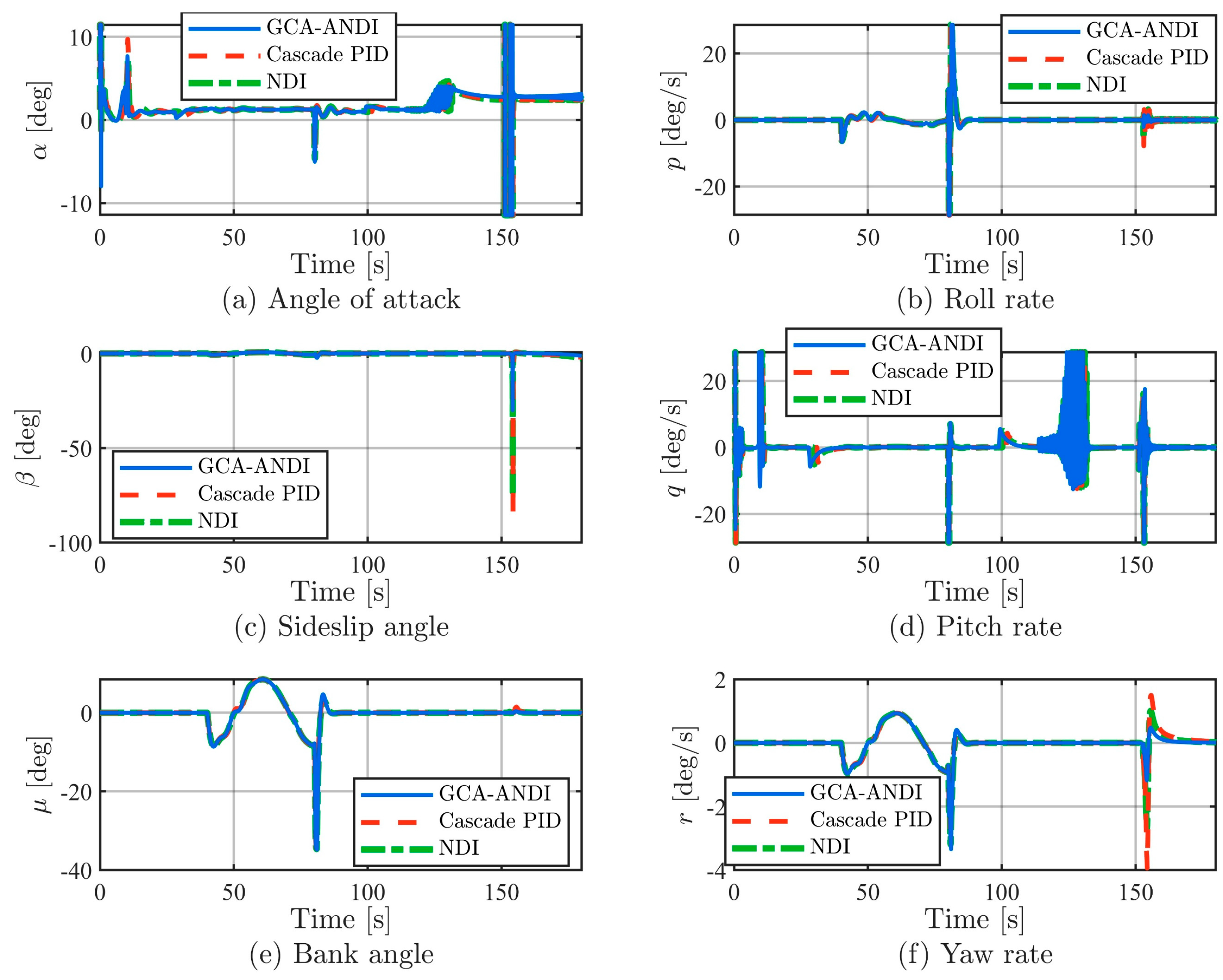

As illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, GCA-ANDI demonstrates exceptional integrated control capabilities for both flight and ground states. By deeply integrating landing gear dynamics into the control architecture, the system can sense and compensate for ground interaction forces in real-time. During the takeoff phase, GCA-ANDI proactively suppresses disturbances from the landing gear, significantly reducing initial state deviations and laying the foundation for precise tracking of true airspeed

, heading angle

, and flight path angle

.

The angle of attack

response curve clearly shows that, compared to traditional controllers, GCA-ANDI effectively suppresses the pitch overshoot peak caused by the elasticity and force transients of the landing gear at the main wheel touchdown. Through precise longitudinal allocation, it significantly reduces landing impact risk at the slight cost of switching angle of attack during the roll phase, greatly increasing the system’s safety margin (as seen in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) and reducing energy consumption.

In terms of sideslip angle control, GCA-ANDI’s advantages are particularly notable: during the critical phase after landing contact, traditional controllers exhibit abnormal sideslip angle peaks due to the inability to accurately model complex lateral friction forces. In contrast, GCA-ANDI, through its real-time force sensing and compensation mechanism, can suppress the instantaneous peak of the sideslip angle to the lowest physically achievable level and quickly apply damping to converge it near zero, while maintaining the heading angle minimally affected by ground disturbances.

In the longitudinal channel, the pitch rate response generated by GCA-ANDI is the smoothest, effectively suppressing the load transients caused by traditional controllers during takeoff rotation and landing contact. In the lateral-directional channel, the roll rate and yaw rate exhibit highly coordinated dynamic characteristics, providing excellent motion damping through precise cross-channel decoupling control.

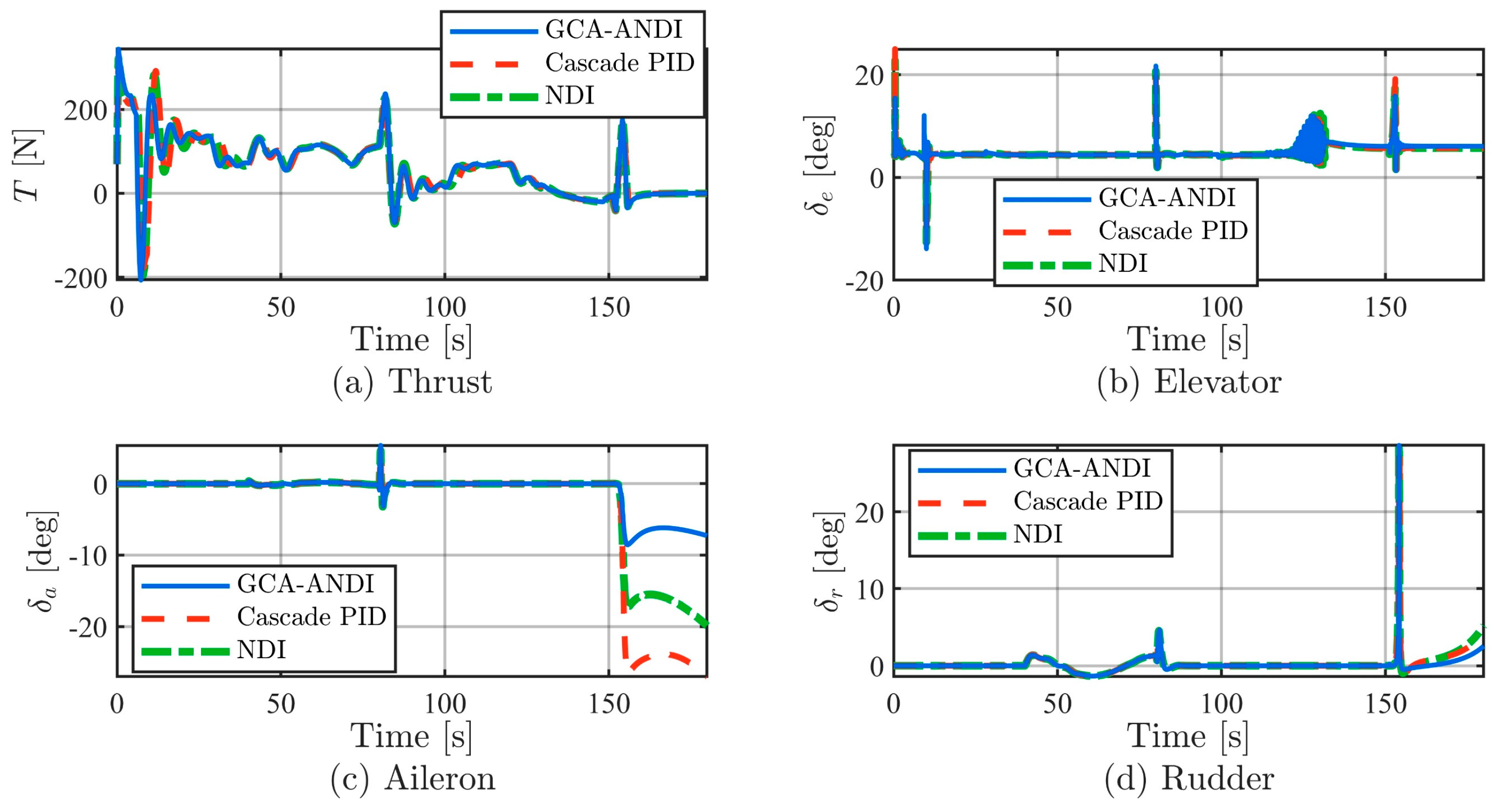

In terms of control input characteristics, GCA-ANDI demonstrates significant operational efficiency advantages (as shown in

Figure 7. By utilizing ground-sensing adaptive compensation and parameter adjustment mechanisms, GCA-ANDI achieves smooth surface deflections and coordinated thrust adjustments. Specifically, the elevator primarily handles angle of attack

and flight path angle

tracking control, while the ailerons and rudder only need to provide minor compensatory actions. Throughout the entire flight, no saturation of control surfaces occurs, significantly reducing the workload on actuators. In contrast, NDI suffers from performance degradation in trajectory tracking due to excessive control input variations caused by model inaccuracies. The slow thrust response and high control surface loads further exacerbate the tracking deterioration due to delays. Although the PID controller shows more stable input characteristics compared to NDI, its effectiveness in handling complex nonlinear systems and ground effects falls short of GCA-ANDI. Overall, GCA-ANDI exhibits the best performance in terms of control input characteristics. This efficient control allocation strategy directly translates to a higher energy efficiency ratio, which is of significant engineering importance for extending UAV flight endurance.

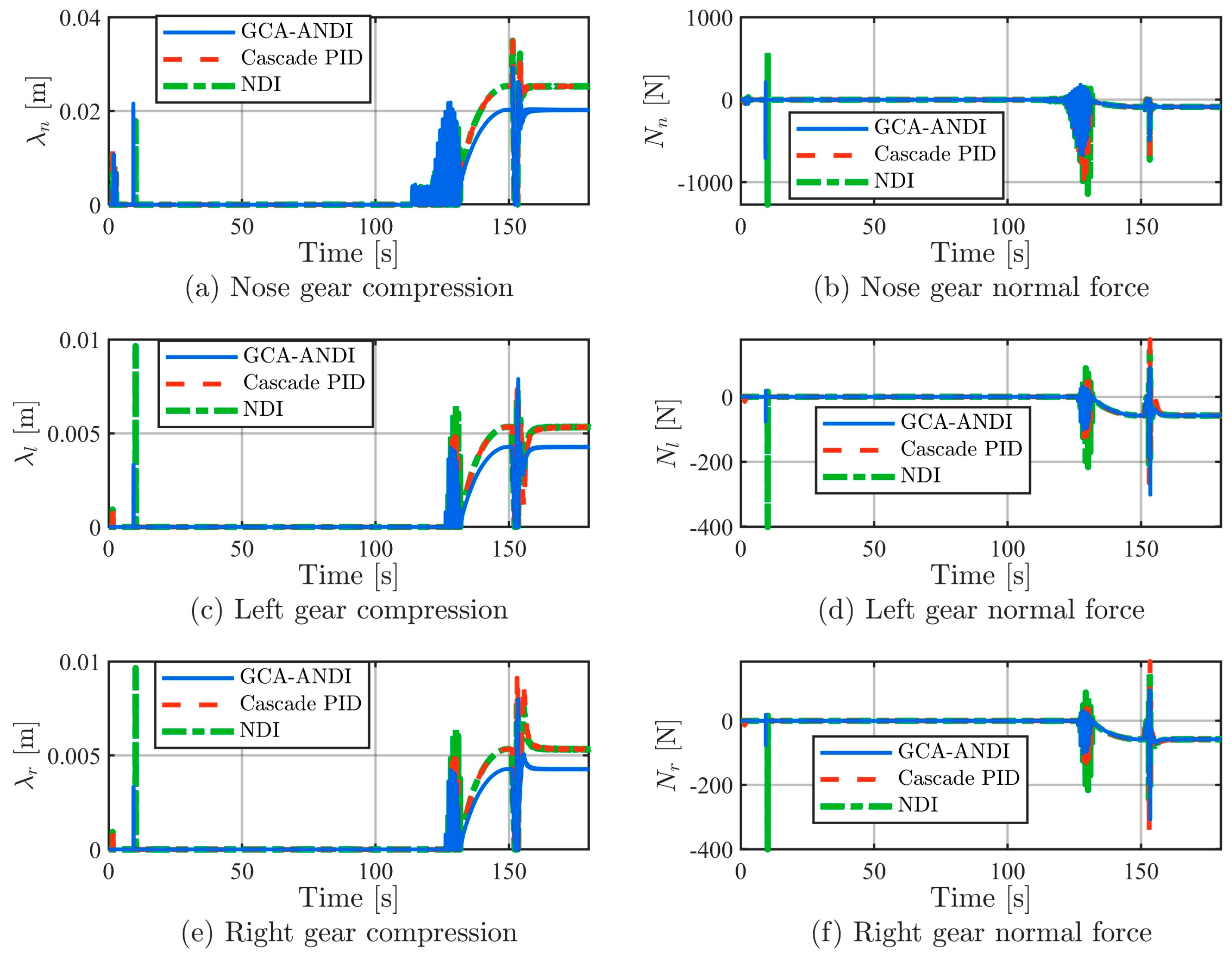

In the landing-gear mechanical response (as shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), under the GCA-ANDI control strategy, the compression of each tire is effectively suppressed, with significantly lower peak values compared to the cascade PID and NDI methods (as shown in

Figure 8). GCA-ANDI, by integrating a high-fidelity landing gear model, enables the controller to sense and predict the changes in normal loads on the front and main wheels in real time. Utilizing this information allows the controller to adaptively adjust the aircraft’s pitch attitude and descent rate, achieving feedforward management and closed-loop control of the support forces. Consequently, despite the support force distribution being influenced by the center of gravity layout, the observed balanced and smooth transition characteristics are actually the result of proactive controller intervention. Compared to other methods, GCA-ANDI effectively reduces the load differences between wheels, significantly enhancing the smoothness of force transitions during the landing phase, thereby reducing impact loads and the risk of unilateral overloads, showcasing excellent impact protection capabilities for the structure.

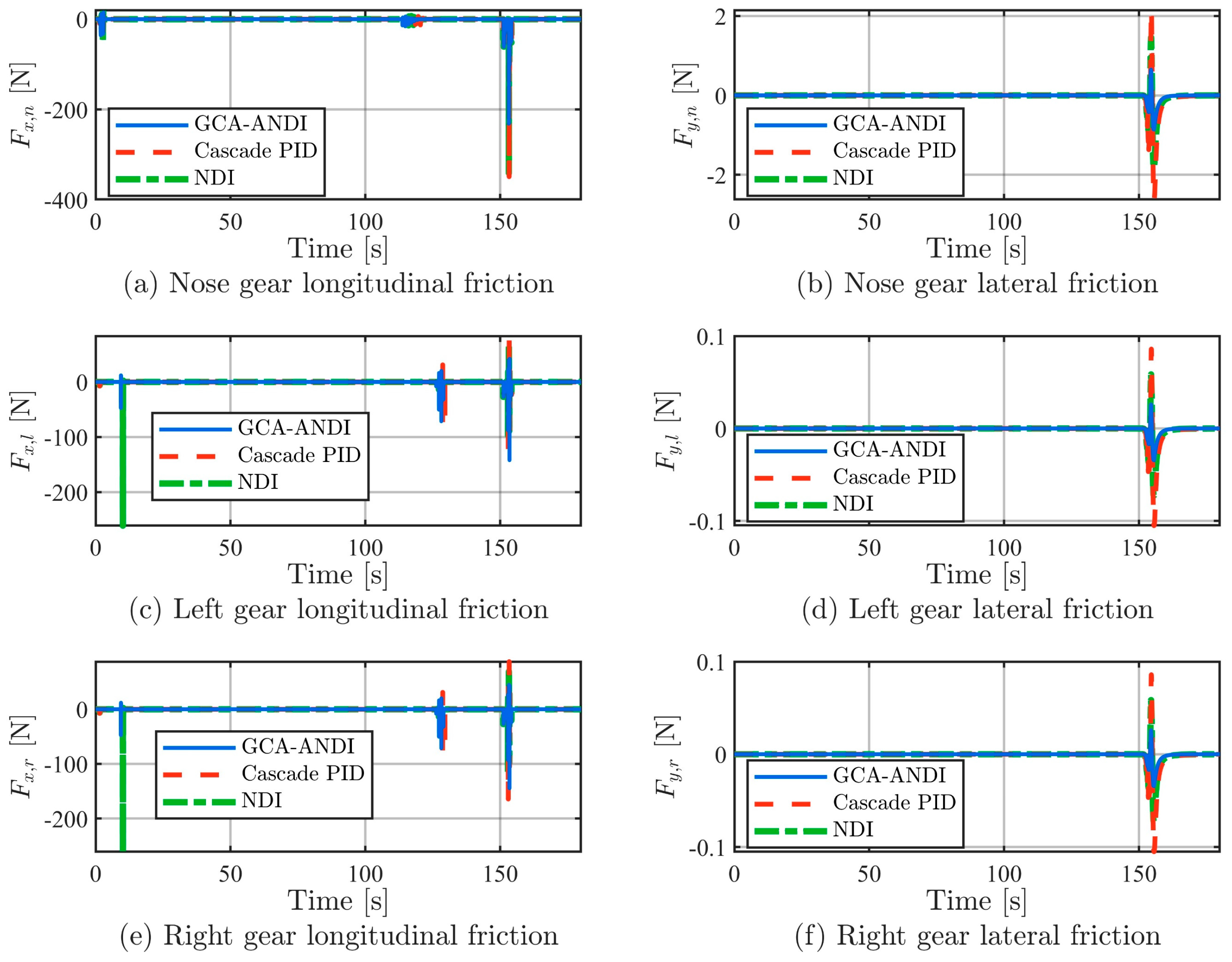

In longitudinal control (

Figure 9), GCA-ANDI combines an accurate landing gear dynamics model, treating the interaction forces and moments between the tires and the ground as key state variables that are fed back to the core controller in real-time. This unique closed-loop control architecture allows the system to make adaptive decisions based on actual physical interactions. By coordinating adjustments in pitch attitude and forward speed, this method dynamically optimizes the longitudinal forces on the nose and main landing gears. Compared to cascade PID and NDI, the control outcomes achieved by GCA-ANDI are more consistent with physical constraints, effectively mitigating “lock-slip” oscillations caused by model mismatch and feedback delays, thereby significantly improving the smoothness of response during acceleration and deceleration processes.

In the lateral control dimension (

Figure 9), the advantage of GCA-ANDI lies in directly considering the lateral friction force of the landing gear as a key control state and constraint. Through real-time lateral force feedback, the controller adaptively coordinates roll and sideslip angle commands, aiming to actively manage rather than passively endure the inherent asymmetric force distributions caused by factors such as propeller torque. This strategy effectively prevents force oscillations resulting from mismatches between controller commands and ground physical responses, thereby significantly reducing the risk of lateral sliding.

Evaluation data during ground operation indicates that GCA-ANDI reduces the root mean square value of landing gear compression by approximately 19.87%, lowers the peak compression by over 16.24%, and significantly decreases the peak normal load by 26.35% to 44.40%. This improvement directly translates to a substantial reduction in impact loads on the landing gear structure, effectively extending the service life of critical components. This control framework exhibits good adaptability to physical parameters. By adjusting the embedded landing gear model parameters in the controller (such as damping coefficients and stiffness), the system can flexibly adapt to landing gear systems with different material properties and structural designs, ensuring optimal support force management and reliable operation of the landing gear structure within its design load range under various operating conditions.

The primary performance metrics encompass three aspects: steady-state fluctuation amplitude of the quantified physical quantity, dynamic tracking accuracy evaluation, and peak performance.

The steady-state fluctuation amplitude is represented by

, which is defined as follows:

where

denotes the time-varying physical quantity under consideration, such as position error or landing gear parameters (including compression

, longitudinal friction force

, lateral friction force

, and normal force

) averaged from the front, left, and right wheel data points. Here,

represents the total measurement duration.

Dynamic tracking accuracy is assessed by

, calculated as

where

represents the error between the reference signal

and the actual output

. The variable

serves as a time weighting factor to emphasize the impact of later-stage errors in the tracking process, with

again denoting the measurement period.

Peak performance is characterized by

, defined as

This metric reflects the maximum fluctuation amplitude of the physical quantity over the entire time range, which is crucial for evaluating the system’s performance under extreme conditions and its safety.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a control system design, the Ground-Contact-Aware Adaptive Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion (GCA-ANDI) method, for fixed-wing UAVs. It aims to manage the complete flight envelope—from taxiing and autonomous takeoff to climb, cruise, descent, and autonomous landing. The GCA-ANDI framework integrates real-time ground contact sensing with phase-adaptive strategies. This approach addresses the strong nonlinear coupling between aircraft dynamics and landing gear–ground interactions during ground phases, as well as aerodynamic uncertainties and phase-specific disturbances during flight. Unlike traditional cascade PID or pure nonlinear dynamic inversion controllers, which lack either phase awareness or explicit handling of ground reaction forces, GCA-ANDI establishes a unified control architecture. It synergistically achieves trajectory tracking, attitude stabilization, and landing gear load management. The system dynamically adjusts control strategies and optimizes control allocation in real-time based on the identified flight phase and ground contact state. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed system enhances overall performance across the entire flight envelope. It significantly improves trajectory tracking accuracy, effectively suppresses attitude fluctuations due to ground disturbances or aerodynamic uncertainties, optimizes landing gear load distribution, and reduces structural impacts during autonomous takeoff and landing. This advancement thereby enhances the autonomy and reliability of UAV operations.

However, this study primarily focuses on aircraft–ground coupled dynamics and the control of conventional flight uncertainties, without considering wind-field disturbances with extreme spatiotemporal discontinuities (e.g., microbursts). Such disturbances induce high-frequency, large-magnitude variations in aerodynamic loads, posing qualitatively different challenges to control loops predicated on feedback compensation and smooth, continuous model assumptions. To enhance UAV survivability and mission success across the full operational envelope under complex meteorological conditions, future work will fuse real-time wind-field sensing and, on this basis, investigate predictive control or adaptive–robust control strategies with anticipatory compensation as major extensions of the present framework.