SSCW-YOLO: A Lightweight and High-Precision Model for Small Object Detection in UAV Scenarios

Highlights

- We propose SCoConv and C2f_ScConv, two lightweight modules that enhance spatial features and suppress redundancy in YOLOv8 for UAV-based small object detection.

- Replacing CIoU with WIoU loss reduces missed detections. The full model achieves 37.8 percent mAP50 on VisDrone, which is 5.4 points higher than YOLOv8n at 115.1 FPS.

- The method shows strong cross-domain generalization with 98.7 percent mAP50 on SSDD, supporting real-world UAV tasks such as maritime surveillance and traffic monitoring.

- With fewer parameters at 2.61 million and real-time speed, it is well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained edge drones.

Abstract

1. Introduction

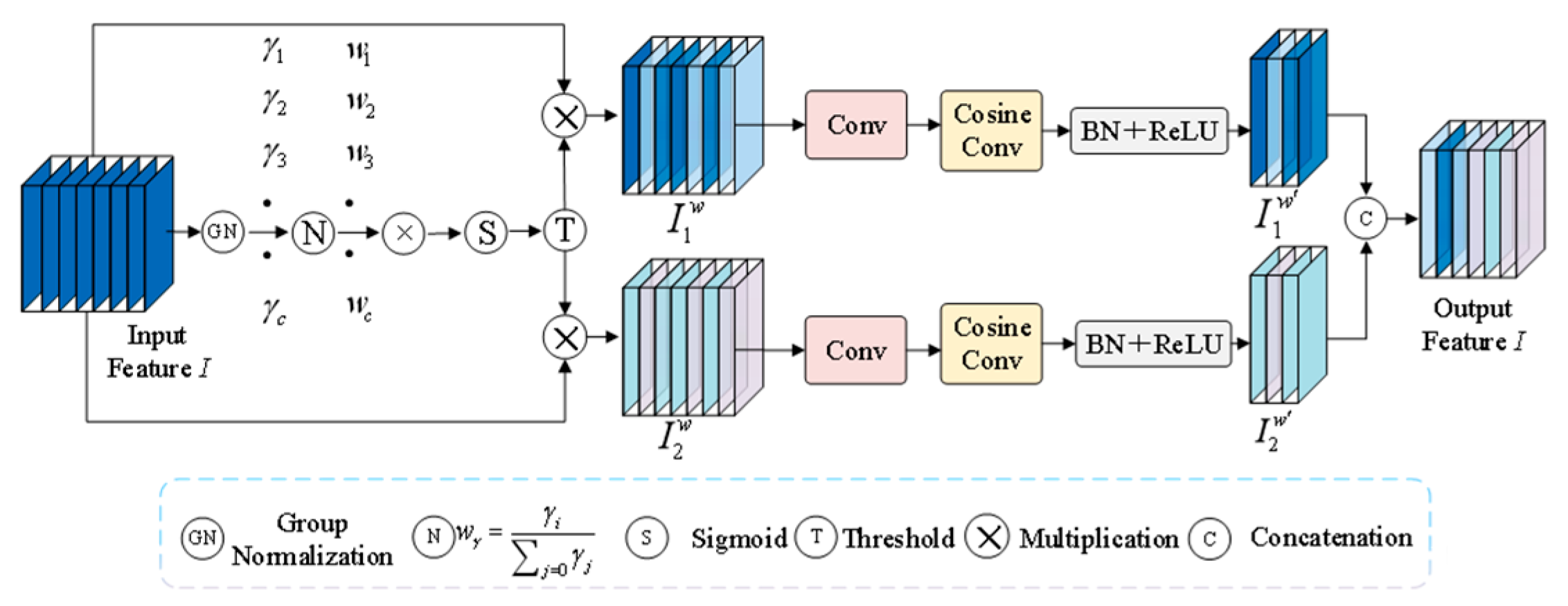

- A Spatial Cosine Convolution (SCoConv) is proposed, integrating the spatial reconstruction mechanism from spatial-channel reconstruction convolution with the directional sensitivity of cosine similarity convolution. This enhances the construction of spatial structural information, reduces contextual information loss, improves feature discriminability, and increases detection accuracy for small UAV targets. Quantitative evidence from ablation experiments (Table 2) validates this claim: compared with the baseline YOLOv8n, the model with SCoConv alone achieves a 1.5% mAP50 improvement (32.4% → 33.9%) and a 1.8% recall increase (31.9% → 33.7%), which confirms that enhanced spatial structural information effectively reduces missed detections of small objects.

- (1)

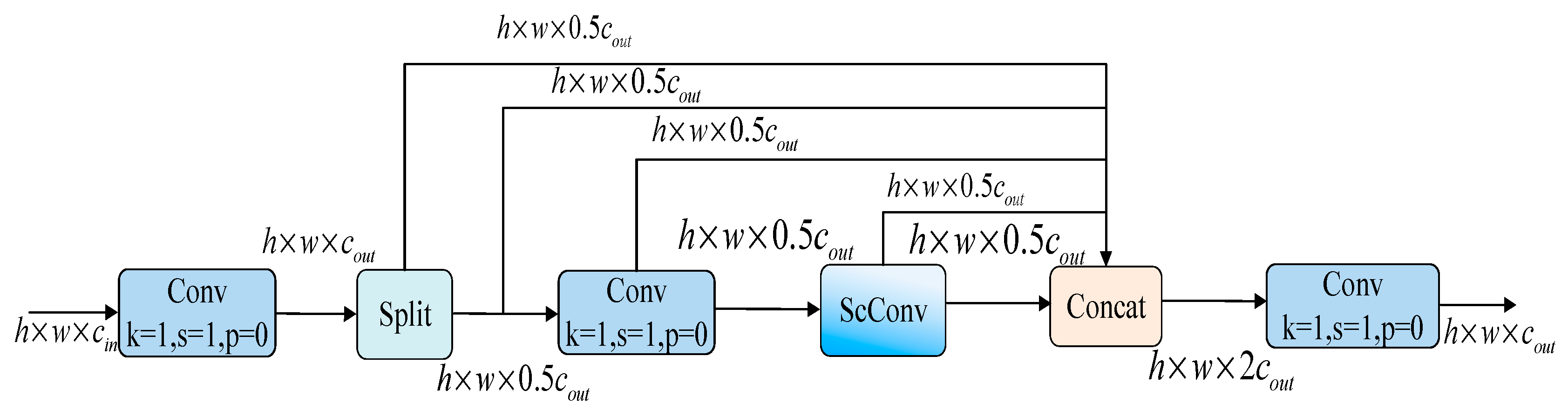

- A new feature fusion module, C2f_ScConv, is designed based on spatial-channel reconstruction convolution, which limits feature redundancy in spatial and channel dimensions, reducing both the model’s parameter count and computational cost.

- (2)

- The WIoU loss function, based on a dynamic non-monotonic focusing mechanism, is adopted as the model’s loss function to address the issue of uneven quality in small object anchor boxes, thereby improving the model’s detection accuracy for small targets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

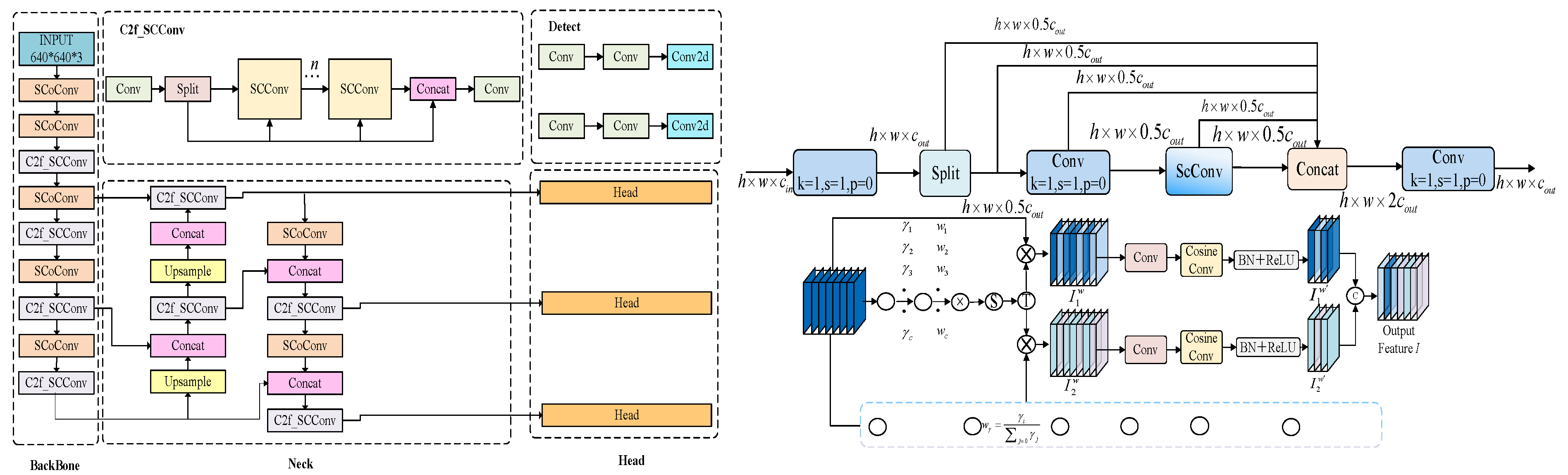

2.2. SSCW-YOLO

2.2.1. Architecture

2.2.2. SCoConv

2.2.3. C2f_ScConv

2.2.4. WIoU Loss

2.2.5. Synergistic Design Philosophy

2.3. Experimental Settings

2.3.1. Experimental Environment

2.3.2. Evaluation Metrics

- (1)

- Precision (P): measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples. In object detection, a prediction is considered correct if the predicted bounding box sufficiently overlaps with the ground-truth bounding box. It is calculated as follows:

- (2)

- Recall (R): measures the proportion of all true positive samples that the model can correctly identify. In object detection, a sample is considered correctly recalled if the ground-truth bounding box sufficiently overlaps with the predicted bounding box. It is calculated as follows:

- The mean Average Precision (mAP) is reported in two forms: mAP50, which considers a single IoU threshold of 0.5, providing a measure of basic detection capability; and mAP50–95, which averages the precision over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05. The latter is the standard metric for comprehensive benchmarks like COCO and provides a more rigorous assessment of localization accuracy. This is particularly crucial for evaluating small object detection, where precise bounding box regression is challenging. Here, n denotes the number of categories. The calculation formula is as follows:

2.3.3. Generalization Experiment Protocol

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Ablation Experiments

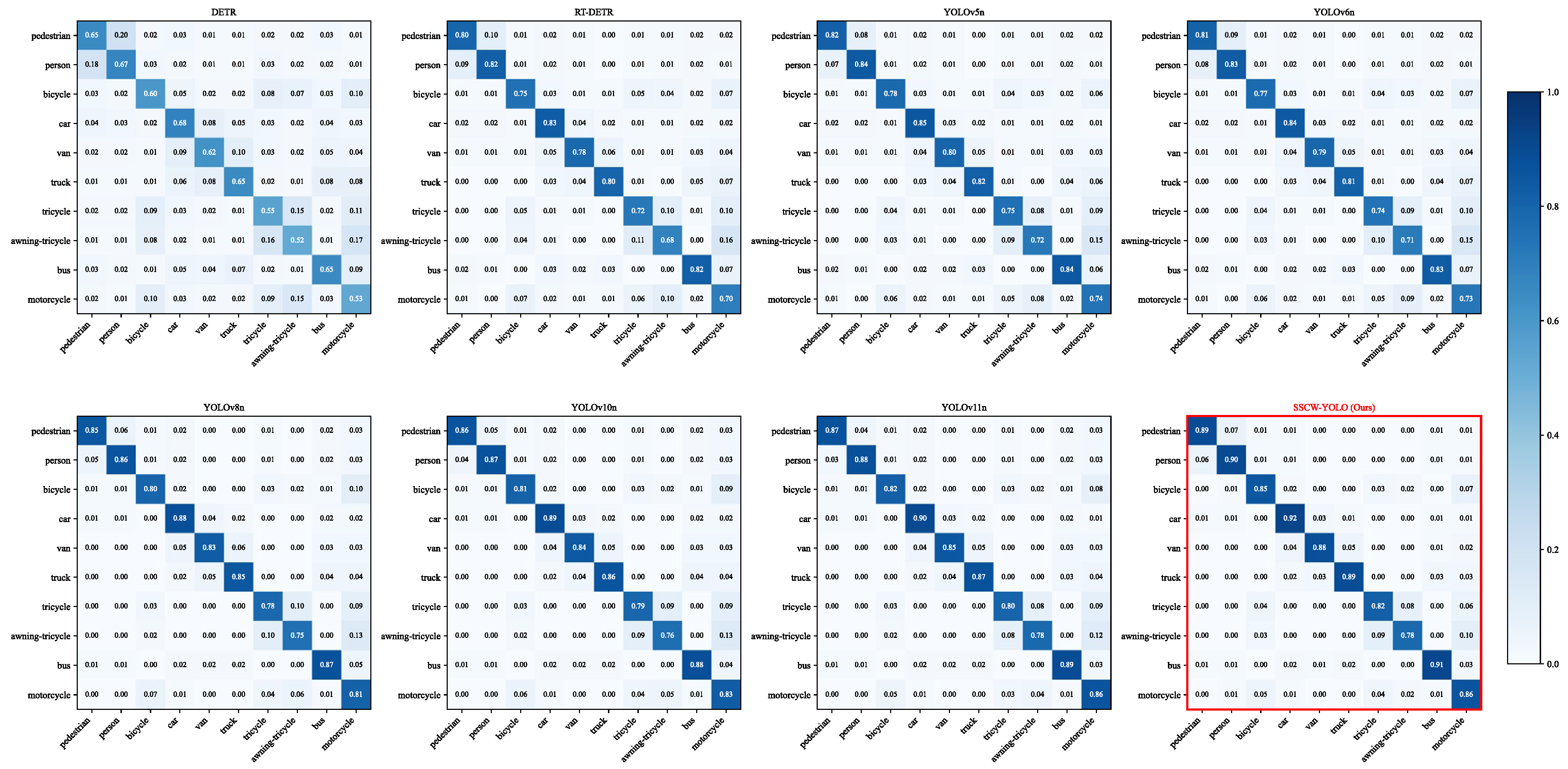

3.2. Comparative Experiments

3.3. In-Depth Analysis of Small Object Detection Performance

3.4. Visualization

3.5. Generalization Experiments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCoConv | Spatial Cosine Convolution |

| ScConv | Spatial and Channel Reconstruction Convolution |

| WIoU | Wise-IoU |

| CIoU | Complete-IoU |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| GN | Group Normalization |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

References

- Choi, H.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, S.-K.; Na, W.S. An overview of drone applications in the construction industry. Drones 2023, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, S.; Swarnkar, R.; Bhukya, S.; Namwade, G. Application of drone in agriculture. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 2500–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.-C.; Pan, J.-S.; Chao, H.-C.; Chu, S.-C. Collaborative Hotspot Data Collection with Drones and 5G Edge Computing in Smart City. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2023, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Singh, H.; Sharma, D.K.; Kumar, A.; Nayyar, A.; Krishnamurthi, R. Dynamic models and control techniques for drone delivery of medications and other healthcare items in COVID-19 hotspots. In Emerging Technologies for Battling COVID-19: Applications and Innovations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, P. The military utility of drones. CSS Anal. Secur. Policy 2010, 78, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, A.; Rabah, M.; Kim, S.-H. Convolutional neural network-based real-time object detection and tracking for parrot AR drone 2. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 69575–69584. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cloutier, R.S. Review on one-stage object detection based on deep learning. EAI Endorsed Trans. e-Learn. 2021, 7, e5. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Auerbach, P.; Okhrin, O. Autonomous Driving Small-Scale Cars: A Survey of Recent Development. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 14591–14614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Krähenbühl, P. Objects as points. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.07850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Qi, X.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Dab-detr: Dynamic anchor boxes are better queries for detr. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.-Y. Dino: Detr with improved denoising anchor boxes for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.03605. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, W.; Peng, J.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Contextual Transformer Based Small Targets Detection for Cervical Cell. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Image Processing and Media Computing (ICIPMC), Hefei, China, 17–19 May 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Guo, J.; Arnatovich, Y.; Liu, Z. Lightweight deep neural network with data redundancy removal and regression for DOA estimation in sensor array. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. UAV-DETR: An enhanced RT-DETR architecture for efficient small object detection in UAV imagery. Sensors 2025, 25, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhi, X.; Hu, J.; Yu, L.; Han, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W. FDDBA-NET: Frequency domain decoupling bidirectional interactive attention network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xie, X.; Xi, J.; Yang, X. GM-DETR: Infrared Detection of Small UAV Swarm Targets Based on Detection Transformer. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwiwu, Q. Object Detection, Segmentation, and Distance Estimation Using YOLOv8; SAVONIA: Kuopio, Finland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. YOLOv8-QSD: An improved small object detection algorithm for autonomous vehicles based on YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, P.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S. Marine Small Object Detection Algorithm in UAV Aerial Images Based on Improved YOLOv8. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 176527–176538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Liang, G.; Wang, X.; Song, Y. Application of the YOLOv6 Combining CBAM and CIoU in Forest Fire and Smoke Detection. Forests 2023, 14, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Ni, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Cao, W. A Survey of Object Detection for UAVs Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Li, Y.; Alsharif, M.H.; Khan, M.A. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Practical Aspects, Applications, Open Challenges, Security Issues, and Future Trends. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2023, 16, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Z. The UAV Target Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, Machine Learning and Pattern Recognition, Guangzhou, China, 13–15 September 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. VisDrone-DET2019: The vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. Scconv: Spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Tian, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, W. Cosine convolutional neural network and its application for seizure detection. Neural Netw. 2024, 174, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, R. Wise-IoU: Bounding box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism. arXiv 2023, arXiv:230110051. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Bao, W.; Shang, H.; Yuan, M.; Cheng, Q. GCL-YOLO: A GhostConv-based lightweight yolo network for UAV small object detection. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Key Improvements | Attention Mechanism | Loss Function | Primary Dataset | mAP50 (%) (VisDrone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5n (Ultralytics) | - | - | CIoU | COCO | 32.3 |

| YOLOv6n (Meituan) | - | - | SIoU | COCO | 30.3 |

| YOLOv8n (Baseline) | - | - | CIoU | COCO | 32.4 |

| YOLOv8Ghost | GhostNet | - | CIoU | COCO | 29.3 |

| YOLOv10n | - | - | - | - | 32.5 |

| YOLO11 | - | - | - | - | 32.9 |

| YOLOv12n | - | - | - | - | 30.9 |

| Wang et al. [23] | BiFPN, Reparam. Blocks | - | - | SODA-A | 33.5 (Estimated) |

| Wei et al. [24] | Micro-head, CA | Coordinate Attention | CIoU | SeaDronesSee | 34.1 (Estimated) |

| Zhou et al. [25] | CBAM, SENet | CBAM, SENet | WIoU | Private | 35.0 (Estimated) |

| SSCW-YOLO (Ours) | SCoConv, C2f_ScConv | Spatial-Cosine (Novel) | WIoU | VisDrone | 37.8 |

| Experimental Setup | P/% | R/% | mAP50(%) | Params | FPS(f/s) | Gflops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n | 44.2 | 31.9 | 32.4 | 3.01 | 101.1 | 8.1 |

| YOLOv8n + SCoConv | 43.9 | 33.7 | 33.9 | 2.82 | 109.3 | 8.4 |

| YOLOv8n + C2f_ScConv | 44.5 | 33.2 | 34.3 | 2.81 | 84.8 | 6.9 |

| YOLOv8n + WIoU | 44.4 | 33.6 | 33.2 | 3.01 | 91.2 | 8.6 |

| YOLOv8n + SCoConv+C2f_ScConv | 46.2 | 36.0 | 35.1 | 3.17 | 105.4 | 9.1 |

| YOLOv8n + SCoConv + WIoU | 44.1 | 33.8 | 33.5 | 3.01 | 103.2 | 8.3 |

| YOLOv8n + C2f_ScConv + WIoU | 45.6 | 34.4 | 35.4 | 2.86 | 87.4 | 9.4 |

| SSCW-YOLO (All modules) | 46.9 | 38.5 | 37.8 | 2.61 | 115.1 | 8.7 |

| Experimental Environment | Related Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Specification | Parameter | Specification |

| Operating system | Ubuntu20.04 | Weight decay factor | 0.0005 |

| Python | Version 3.10 | Initial learning rate | 0.01 |

| Pytorch | Version 2.3.0 | Image_size | 640 × 640 |

| CUDA | Version 12.1 | Momentum | 0.937 |

| CPU | Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6154 CPU @ 3.00 GHz | Optimizer | SGD |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX3090@24 G | Epoch | 200 |

| Method | P(%) | R(%) | mAP50(%) | mAP50–95(%) | Param/M | FPS(f/s) | Gflops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster R-CNN | - | - | 21.7 | - | - | - | - |

| Center Net [34] | - | - | 26.0 | - | - | - | - |

| DETR | 35.2 | 22.8 | 20.1 | 11.5 | 41.5 | 12.3 | 10.8 |

| RT-DETR | 40.1 | 28.5 | 28.7 | 16.2 | 28.3 | 35.7 | 8.9 |

| YOLOv3-tiny | 37.6 | 24.0 | 23.4 | 12.8 | 12.1 | 55.6 | 7.4 |

| YOLOv5n | 42.8 | 32.0 | 32.3 | 18.2 | 2.19 | 88.5 | 9.2 |

| YOLOv6 | 39.8 | 31.2 | 30.3 | 17.5 | 4.2 | 67.3 | 6.7 |

| YOLOv8n | 44.2 | 31.9 | 32.4 | 19.0 | 3.0 | 101.5 | 8.1 |

| YOLOv8ghost | 40.0 | 29.8 | 29.3 | 16.5 | 1.72 | 94.6 | 7.7 |

| YOLOv8Ghostp2 | 44.0 | 32.3 | 32.6 | 18.8 | 1.6 | 97.7 | 8.9 |

| YOLOv10 | 43.0 | 32.4 | 32.5 | 18.7 | 2.71 | 70.2 | 8.2 |

| YOLO11 | 42.7 | 33.0 | 32.9 | 18.8 | 2.59 | 82.3 | 6.3 |

| YOLOv12n | 41.6 | 31.3 | 30.9 | 17.8 | 2.5 | 47.7 | 6.0 |

| SSCW-YOLO | 46.9 | 38.5 | 37.8 | 22.3 | 2.73 | 115.1 | 8.7 |

| Method | mAP50 (Overall) | AP50-Small | AP50-Medium | AP50-Large | Param (M) | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Models | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DETR | 20.1 | 8.2 | 25.3 | 32.7 | 41.5 | 10.8 | 12.3 |

| RT-DETR | 28.7 | 15.6 | 33.2 | 40.1 | 28.3 | 8.9 | 35.7 |

| YOLOv5n | 32.3 | 15.2 | 40.5 | 55.1 | 2.19 | 9.2 | 88.5 |

| YOLOv6n | 30.3 | 14.1 | 39.8 | 54.2 | 4.20 | 6.7 | 67.3 |

| YOLOv8n | 32.4 | 16.8 | 41.3 | 56.0 | 3.01 | 8.1 | 101.1 |

| YOLOv8ghost | 29.3 | 13.5 | 38.9 | 53.7 | 1.72 | 7.7 | 94.6 |

| YOLOv8Ghostp2 | 32.6 | 16.9 | 41.5 | 56.3 | 1.60 | 8.9 | 97.7 |

| YOLOv10n | 32.5 | 17.5 | 41.9 | 56.5 | 2.71 | 8.2 | 70.2 |

| Scene Type | Model | mAP50 (%) | mAP50–95 (%) | Miss Rate (%) | False Detection Count (Per Image) | Inference Speed (FPS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dense Crowds (VisDrone) | YOLOv8n | 72.3 | 45.6 | 18.7 | 12 | 115 |

| YOLOv11n | 74.8 | 48.2 | 15.3 | 9 | 108 | |

| SSCW-YOLO | 79.5 | 53.8 | 9.2 | 5 | 102 | |

| Small Vehicles in Complex Backgrounds (VisDrone) | YOLOv8n | 68.5 | 41.3 | 22.1 | 15 | 112 |

| YOLOv11n | 71.2 | 43.7 | 18.5 | 11 | 105 | |

| SSCW-YOLO | 76.9 | 49.5 | 11.8 | 6 | 99 | |

| Edge Small Objects (VisDrone) | YOLOv8n | 63.7 | 37.5 | 27.4 | 18 | 110 |

| YOLOv11n | 66.4 | 39.8 | 23.6 | 14 | 103 | |

| SSCW-YOLO | 73.2 | 45.1 | 15.7 | 8 | 97 |

| Model | Feature Response Mean | Small Object Region Response Intensity | Background Redundancy Response Ratio (%) | Feature Focus Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n | 0.62 | 0.48 | 28.3 | 65.7 |

| YOLO11 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 24.1 | 70.3 |

| SSCW-YOLO | 0.73 | 0.61 | 16.8 | 78.9 |

| Datasets | Models | P(%) | R(%) | mAP50(%) | mAP50–95(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | DETR | 61.3 | 45.2 | 35.7 | 19.2 |

| RT-DETR | 64.2 | 50.1 | 42.6 | 23.8 | |

| YOLOv3-Tiny | 68.3 | 27.9 | 31.5 | 18.3 | |

| YOLOv5 | 63.5 | 35.0 | 37.6 | 22.2 | |

| YOLOv6 | 71.0 | 33.4 | 36.0 | 21.4 | |

| YOLOv8 | 62.9 | 37.0 | 39.5 | 23.6 | |

| YOLOv10 | 55.7 | 34.0 | 35.0 | 20.9 | |

| YOLO11 | 64.6 | 35.8 | 38.3 | 22.9 |

| Datasets | Models | P(%) | R(%) | mAP50(%) | mAP50–95(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSDD | DETR | 93.1 | 85.7 | 90.2 | 68.5 |

| RT-DETR | 96.8 | 92.1 | 94.5 | 70.8 | |

| YOLOv3-Tiny | 94.1 | 88.2 | 95.7 | 71.0 | |

| YOLOv5n | 95.4 | 94.1 | 97.7 | 71.9 | |

| YOLOv6n | 96.0 | 92.9 | 97.0 | 72.8 | |

| YOLOv8n | 95.5 | 93.6 | 97.2 | 72.1 | |

| YOLOv10n | 94.9 | 92.7 | 97.2 | 72.2 |

| Dataset | Model | mAP50 (%) | mAP50–95 (%) | Large Object mAP (%) | Small Object mAP (%) | Inference Speed (FPS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | YOLOv8n | 75.6 | 49.2 | 82.3 | 58.7 | 98 |

| YOLOv11n | 78.1 | 51.8 | 84.5 | 62.3 | 92 | |

| SSCW-YOLO | 83.4 | 57.5 | 88.6 | 69.8 | 86 | |

| SSDD | YOLOv8n | 70.2 | 43.5 | 76.8 | 52.1 | 105 |

| YOLOv11n | 72.9 | 46.3 | 79.4 | 55.8 | 99 | |

| SSCW-YOLO | 78.7 | 52.6 | 84.2 | 63.4 | 93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Z.; She, R.; Tan, B.; Li, J.; Lei, X. SSCW-YOLO: A Lightweight and High-Precision Model for Small Object Detection in UAV Scenarios. Drones 2026, 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010041

He Z, She R, Tan B, Li J, Lei X. SSCW-YOLO: A Lightweight and High-Precision Model for Small Object Detection in UAV Scenarios. Drones. 2026; 10(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhuolun, Rui She, Bo Tan, Jiajian Li, and Xiaolong Lei. 2026. "SSCW-YOLO: A Lightweight and High-Precision Model for Small Object Detection in UAV Scenarios" Drones 10, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010041

APA StyleHe, Z., She, R., Tan, B., Li, J., & Lei, X. (2026). SSCW-YOLO: A Lightweight and High-Precision Model for Small Object Detection in UAV Scenarios. Drones, 10(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010041