BEHAVE-UAV: A Behaviour-Aware Synthetic Data Pipeline for Wildlife Detection from UAV Imagery

Highlights

- We introduce a behaviour-aware Unreal Engine 5 pipeline (BEHAVE-UAV) that jointly models animal group dynamics, UAV flight geometry and camera readout to generate detector- and tracker-ready synthetic wildlife imagery.

- High-resolution synthetic pre-training at 1280 px, followed by fine-tuning on only half of the real Rucervus UAV images, recovers nearly all detection performance of a model trained on the fully labelled real dataset.

- Behaviour-aware synthetic data can substantially reduce manual annotation effort in UAV wildlife monitoring by enabling sample-efficient training from high-altitude imagery.

- The results provide practical guidance for configuring resolution, synthetic pre-training and fractional real fine-tuning when designing object detectors for long-range ecological UAV applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Related Works

1.2.1. Synthetic Data for Computer Vision and Ecology

1.2.2. Behaviour Modelling and Animal Movement

1.2.3. UAV Datasets for Object Detection and Long-Range Monitoring

1.2.4. Research Gaps in Existing Synthetic Pipelines

1.3. Research Questions and Contributions

- We introduce a behaviour-aware UE5 pipeline that jointly models animal group dynamics, UAV flight geometry, and camera readout, and exports detector-ready YOLO annotations together with instance masks and tracking metadata, bridging the gap between visual realism, behavioural realism, and UAV-accurate imaging;

- We instantiate this pipeline for high-altitude deer monitoring and generate a synthetic UAV dataset with automatically produced labels, enabling reproducible experiments in long-range wildlife detection and releasing the data for public use.

- We conduct a controlled evaluation of YOLOv8s under six training regimes and two image resolutions on both synthetic and real deer imagery, quantifying the effect of synthetic pre-training and scale on transfer performance.

- Based on these experiments, we derive practical guidelines for sample-efficient UAV wildlife detection, showing that high-resolution synthetic pre-training followed by fine-tuning on only a fraction of the real data can approach the accuracy of fully supervised training while substantially reducing manual annotation effort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. BEHAVE-UAV Synthetic Pipeline

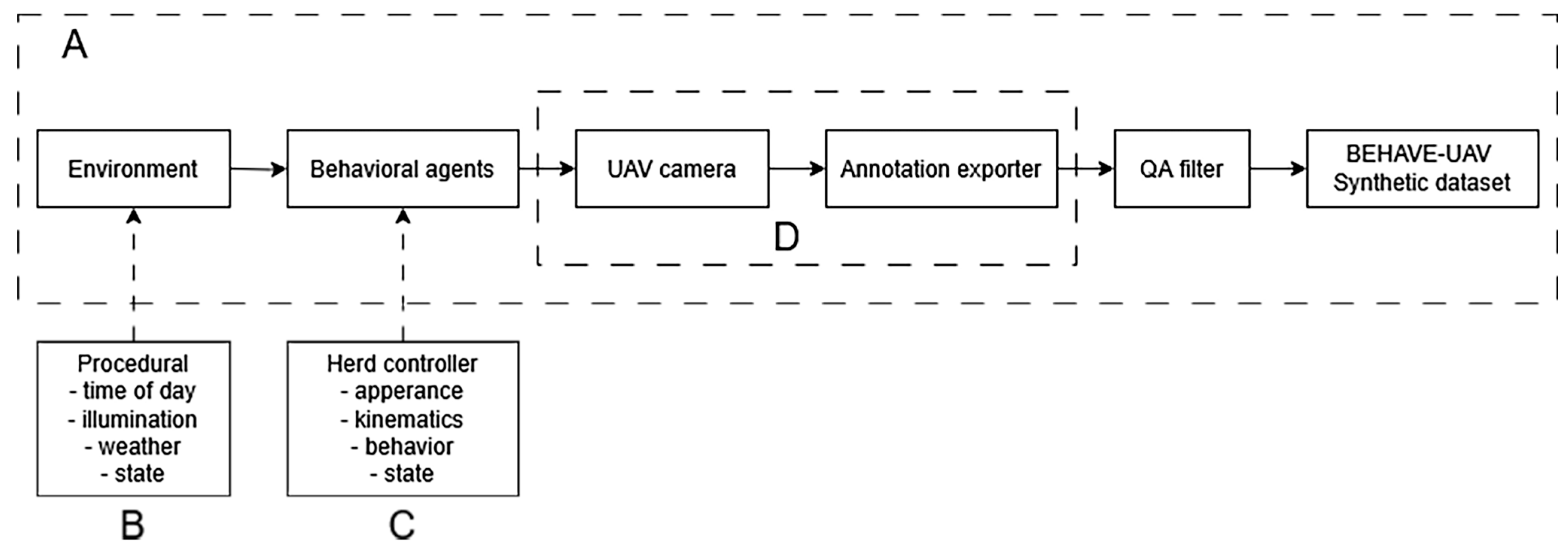

2.1.1. Overall Pipeline

2.1.2. Environment and Domain Randomization

- time of day (e.g., morning, midday, evening);

- illumination conditions (direct sun, overcast, low sun angle);

- atmospheric effects (haze intensity, aerial perspective);

- ground moisture and vegetation state (dry and wet soil, green and brown foliage).

2.1.3. Biological Agents and Behaviours

- Appearance: a set of 3D mesh variants with different antler configurations, materials and texture sets.

- Kinematics: base speed, perception radius and maximum acceleration that govern physical motion.

- Social behaviour: interaction rules between nearby agents that approximate herd dynamics.

- High-level states: a finite state machine with states such as idle, walk and run, and context-dependent transitions.

2.1.4. UAV Platform and Automatic Annotation

- an RGB image at 1920 × 1080 resolution (16-bit colour);

- a per-pixel instance segmentation mask for all animal agents;

- per-object metadata (3D position and orientation in the global coordinate system, instantaneous velocity, agent identifier);

- YOLO-format bounding boxes, defined by normalised centre coordinates and box width and height.

2.1.5. Quality-Assurance Filtering

- no valid animal instances are visible in the camera frustum;

- all bounding boxes are degenerate (zero or negative extent after projection);

- all visible animals are truncated at image borders such that their bounding boxes cover only a minimal number of pixels;

- the median bounding-box area across all instances in the frame falls below a small threshold relative to the full image area, i.e., < τ ⋯ W ⋯ H, where W and H are the image width and height.

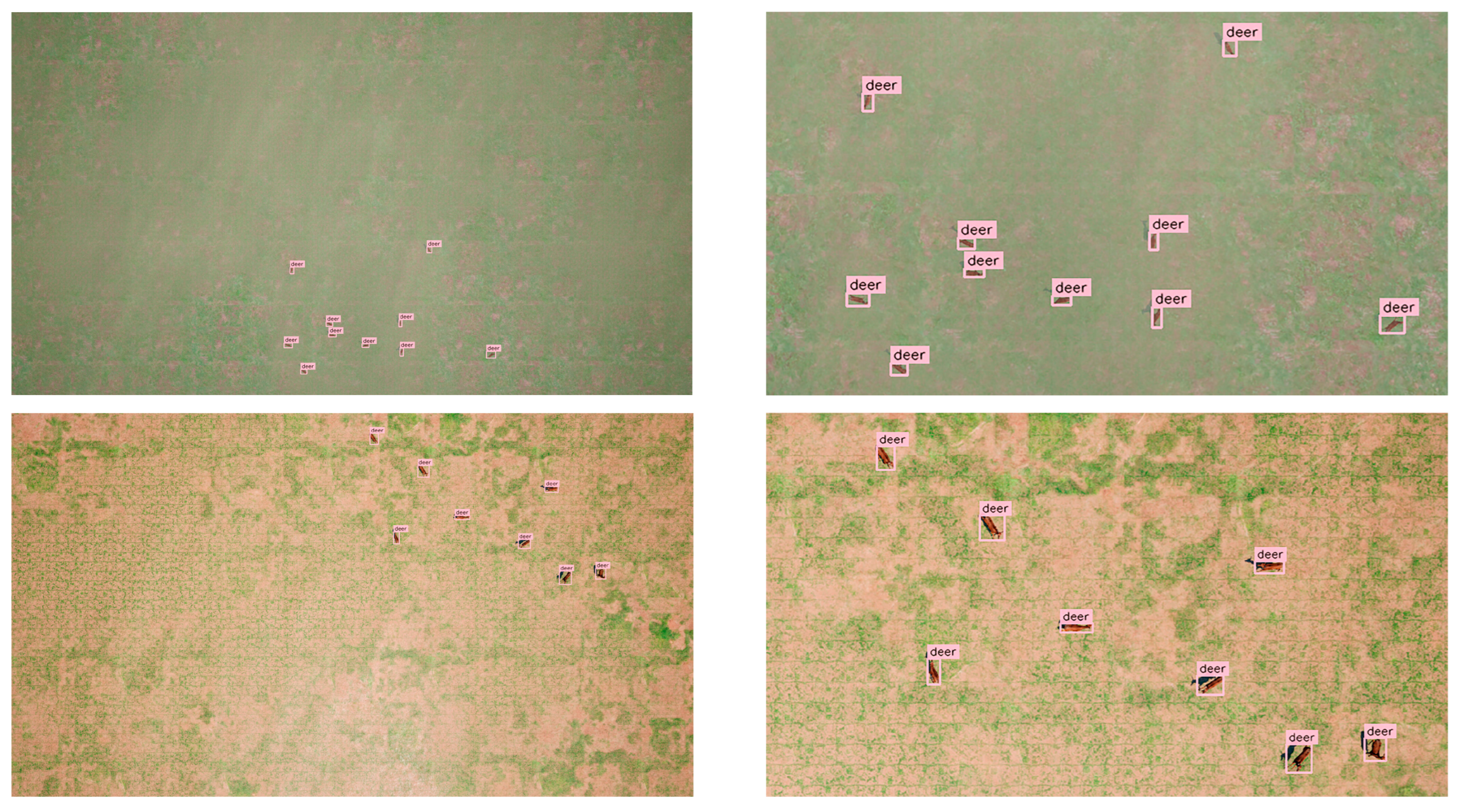

2.2. Synthetic Dataset

- animal count per frame (from isolated individuals to dense herds);

- viewing geometry (altitude, off-nadir angle, UAV heading);

- illumination and background (combinations of season, time of day and vegetation density).

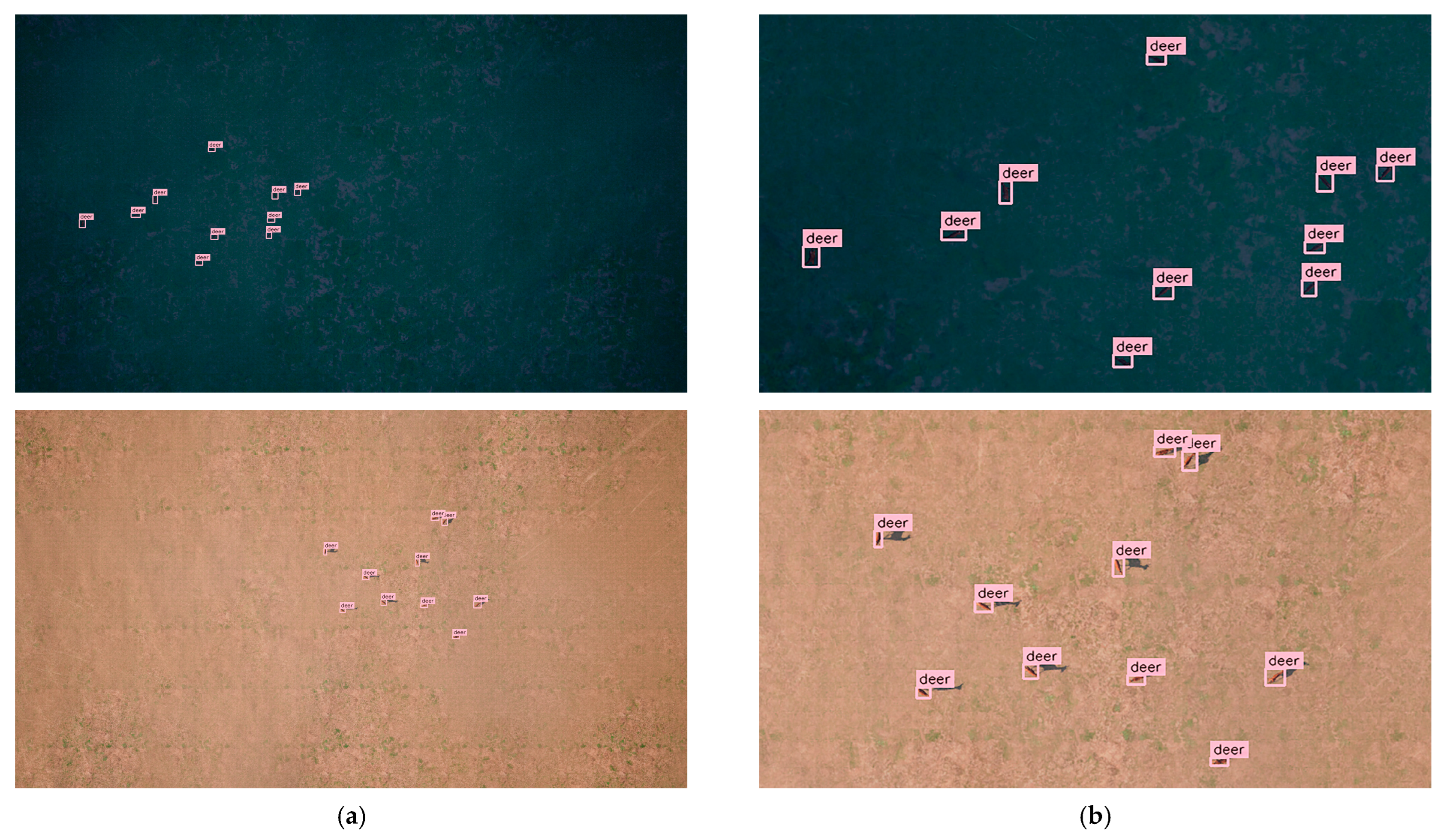

2.3. Real Dataset

2.4. COCO-Pretrained Baseline

- initialised from COCO-pretrained weights and trained directly on real Rucervus images (real-only regimes), or

- initialised from COCO-pretrained weights, trained on synthetic BEHAVE-UAV data, and then fine-tuned on real Rucervus images (synthetic-pretrained regimes).

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

- Precision (P) and recall (R) at IoU = 0.5, where a detection is counted as correct if its IoU with a ground-truth box is greater than 0.5;

- Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 (AP@0.5), defined as the area under the precision–recall curve obtained by varying the detection confidence threshold at IoU = 0.5;

- Mean Average Precision (mAP) computed as the mean of AP over classes (single class in our case) and, where relevant, over multiple IoU thresholds.

Smedium = {A|0.02 ≤ A < 0.10},

Slarge = {A|0.10 ≤ A ≤ 1.0}.

2.6. Training Regimes and Experimental Design

- Synthetic-only @640 px. The model is initialised from COCO-pretrained YOLOv8s weights and trained on the BEHAVE-UAV training split using 640 × 640 px inputs. Validation and test evaluation are performed on the internal synthetic splits to verify that the synthetic pipeline and label export are functional.

- Real-only (COCO-pretrained) @640 px. The model is initialised from the same COCO-pretrained weights and trained solely on the Rucervus training split at 640 × 640 px. This regime represents the standard “real-only” baseline for the real dataset.

- Synthetic-pretrained + real fine-tuning (100%) @640 px. We first train the detector on the synthetic training split as in regime (1), then fine-tune the resulting weights on 100% of the Rucervus training split at 640 × 640 px. This regime isolates the effect of synthetic pre-training when the amount of real supervision is fixed.

- Synthetic-only @1280 px. As in regime (1), but with 1280 × 1280 px inputs. This configuration probes how much synthetic-only performance can be improved by increasing the input resolution, keeping the data source and optimisation settings fixed.

- Real-only (COCO-pretrained) @1280 px. As in regime (2), but with 1280 × 1280 px inputs. Together with regime (4), this regime quantifies the effect of higher input resolution on real-only training.

- Synthetic-pretrained + real fine-tuning with fractional real data @1280 px. We first train on synthetic data at 1280 × 1280 px as in regime (4), then fine-tune the resulting model on different fractions f of the Rucervus training split, with f ∈ {10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100}%. For each fraction f we draw a random subset of the training images of the corresponding size using a fixed random seed and keep the validation and test splits unchanged. Each fraction is trained once under the same optimisation settings and early-stopping rule. This design allows us to quantify how performance on the real test set grows with additional real supervision after synthetic pre-training, and to identify the point at which adding more real images yields diminishing returns.

2.7. Use of Generative AI

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Detection Performance Across Training Regimes

3.2. Effect of Real-Data Fraction After Synthetic Pre-Training

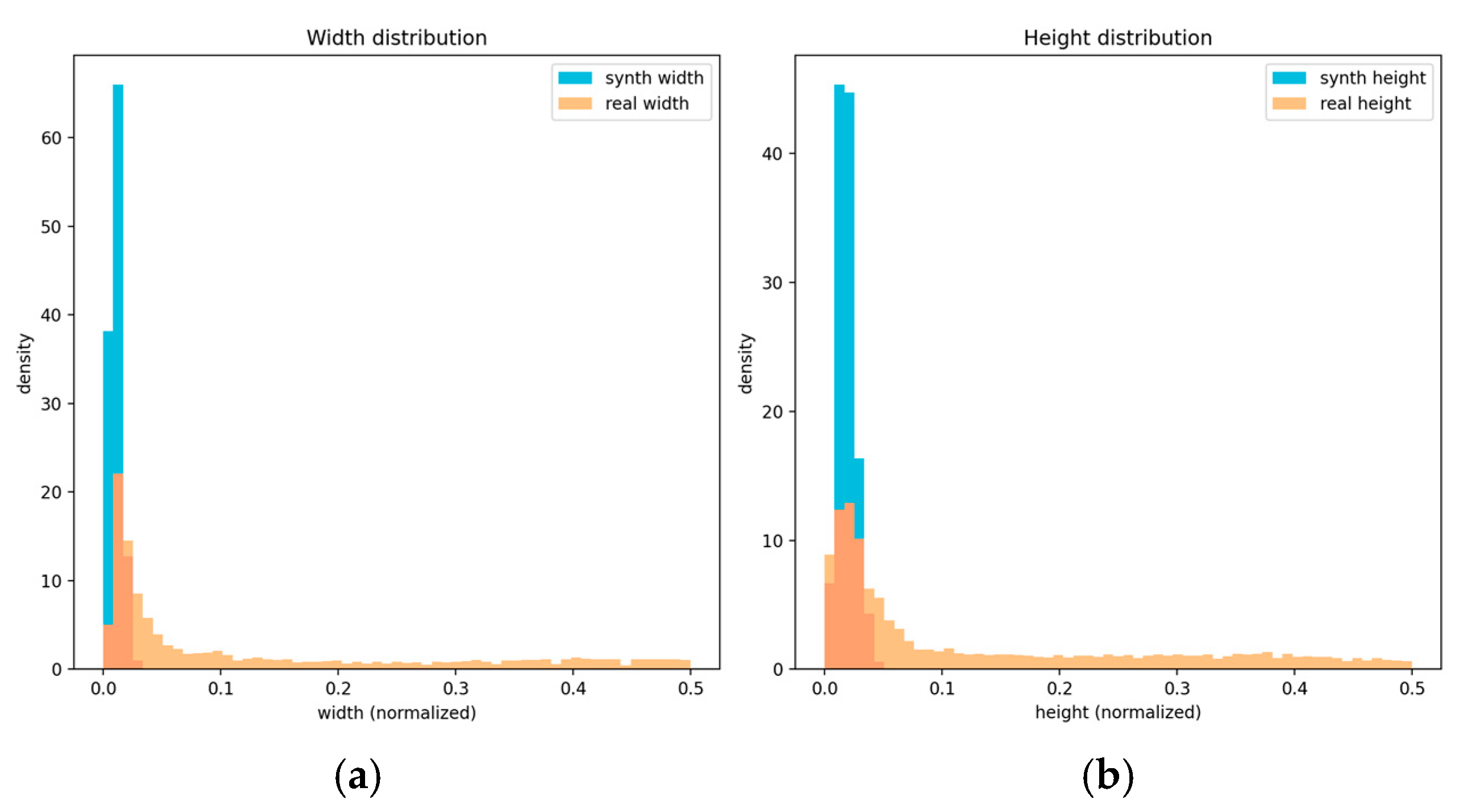

3.3. Scale-Aware Behaviour and Distribution Shift

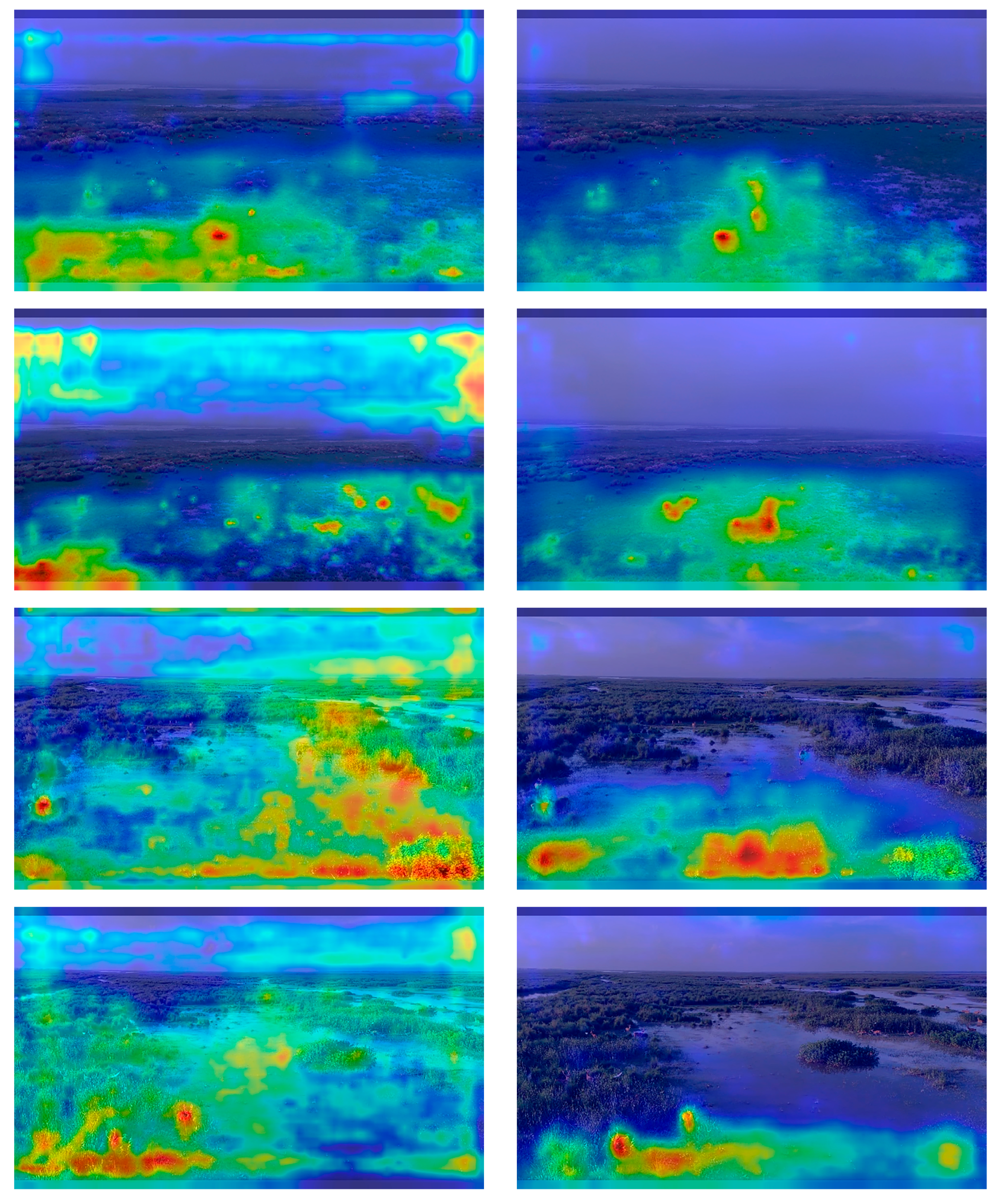

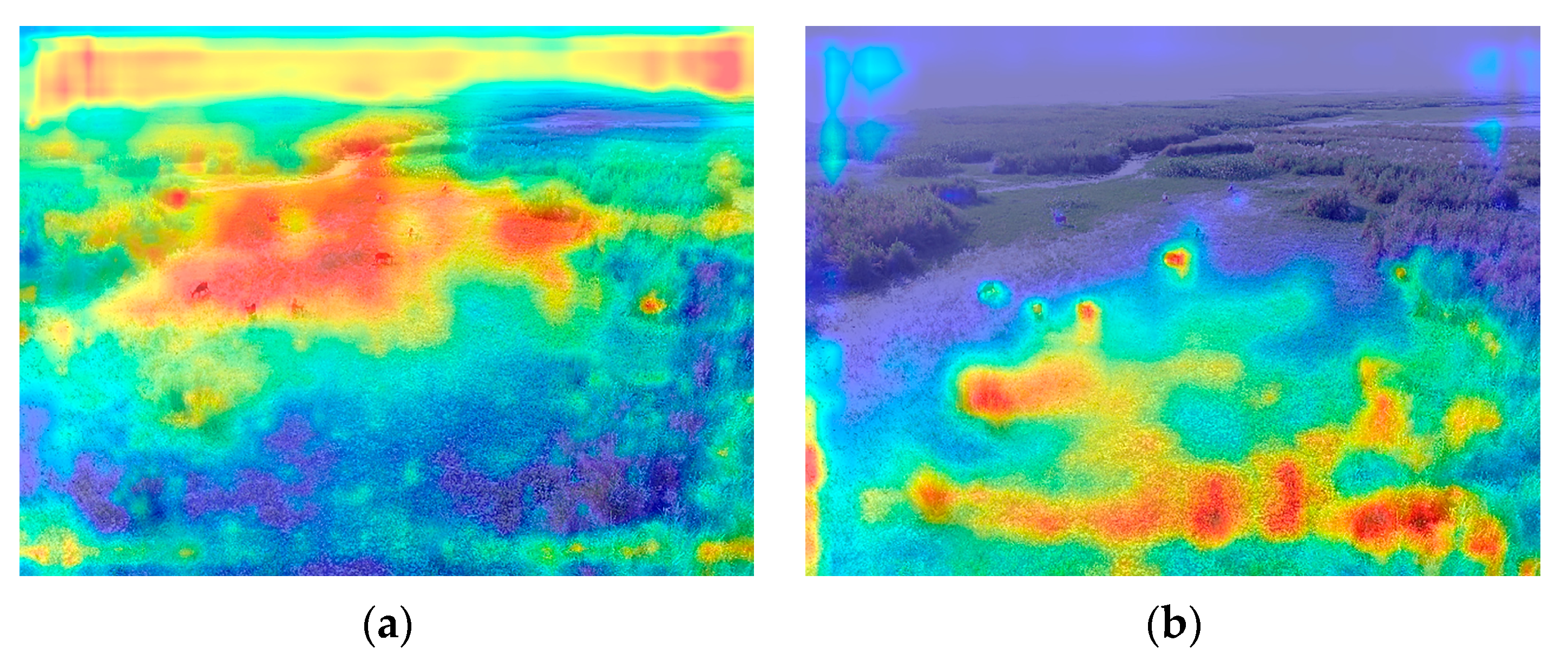

3.4. Qualitative Analysis on Real UAV Images

- Small and distant animals. In frames where deer occupy only a few dozen pixels, the synthetic-pretrained model tends to detect more true positives than the real-only model, producing fewer missed small objects at similar precision. This aligns with the quantitative behaviour in Section 3.3, where improvements are concentrated in the APsmall regime.

- Moderate scale and partial occlusion. For medium-sized deer under partial occlusion by vegetation or other animals, the synthetic-pretrained model often recovers occluded individuals that the real-only model misses, resulting in higher recall at comparable precision.

- Close-up animals. When deer are large in the frame, both models perform well in most cases. Occasional failures are typically due to annotation issues (e.g., ambiguous or incomplete labels) or boundary truncation at image edges rather than systematic detector errors.

- Background confounders. False positives, though infrequent, tend to arise from background structures, such as logs, rocks or high-contrast vegetation patches, that resemble deer in shape or texture at long range. Both models can be affected, indicating that these errors stem from scene-appearance ambiguity rather than from the specific training regime.

4. Discussion

- High-resolution input is essential for the target use case. In the simulated high-altitude regime, increasing the input size from 640 px to 1280 px substantially boosts mAP@[0.5:0.95] (from 0.54 to 0.79 in our setting) and nearly saturates the precision–recall curves. This confirms that providing more pixels per deer is critical for small-object detection in wide-area UAV imagery and that low-resolution configurations under-exploit the available information.

- Synthetic pre-training followed by fractional real fine-tuning is sample-efficient. At 1280 px, fine-tuning on 50% of the real Rucervus data achieves around 95% of the best average precision obtained with the full real training set, and the performance curve plateaus around 0.42 mAP@[0.5:0.95] as the fraction of real data grows. This suggests a practical workflow for ecological UAV monitoring: generate synthetic data at the correct altitude and scale, then annotate and fine-tune on only half of the real corpus while retaining most of the achievable accuracy. These findings are consistent with prior studies on synthetic-to-real transfer and domain randomization for robotics and autonomous driving, where synthetic pre-training plus limited real fine-tuning yields strong downstream performance [11,15,24].

- Domain shift is dominated by scale. Deer appear substantially larger in real frames than in our synthetic distribution, especially when UAVs fly at lower altitudes or orbit closer to the animals. Without explicit scale-aware augmentation, models remain biased toward tiny objects and underperform on close-ups, consistent with the scale-specific AP breakdown: improvements on synthetic-like small targets do not fully transfer to large, near-field animals.

- Synthetic initialisation behaves differently for convolutional and transformer-based detectors. For convolutional models (YOLOv8s and YOLO11n), synthetic pre-training followed by fine-tuning on 50% of the real data yields mAP@[0.5:0.95] that is within 1–2 percentage points of the full real-only baselines (0.46 vs. 0.41–0.42), while slightly increasing precision and incurring only modest recall loss. This indicates that behaviour-aware synthetic pre-training preserves most detection quality while halving the real annotation budget, and tends to bias the models towards more conservative, high-precision predictions. In contrast, the transformer-based RT-DETR-L benefits much more strongly: its real-only training reaches only 0.11 mAP, whereas synthetic pre-training plus fine-tuning on 50% of the real data raises mAP to 0.31 and markedly improves both precision and recall. Synthetic pre-training also shifts the best epoch earlier in training, suggesting more stable optimisation. Together, these cross-architecture results indicate that our synthetic pipeline is particularly helpful for data-hungry transformer-based detectors, while still providing competitive, sample-efficient performance for more mature convolutional families.

- Keep the effective input size around 1280 px and enable multi-scale training or inference to better cover the range of UAV altitudes encountered in practice;

- Use tile-based inference for scenes with very small deer in very wide fields-of-view, so that each tile preserves sufficient resolution per animal without exceeding memory constraints;

- Add scale-mix augmentations (for example, random crops and resizes that keep animals large within the crop) to better cover the real close-up distribution and explicitly address the observed scale mismatch;

- Expand or rebalance the real training split with additional empty frames and a small set of deliberately hard examples (occlusions, shadows, cluttered backgrounds), and revisit label noise, because our qualitative analysis indicate false negatives when deer are heavily clustered or partially occluded.

5. Conclusions

Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thatikonda, M.; PK, M.K.; Amsaad, F. A Novel Dynamic Confidence Threshold Estimation AI Algorithm for Enhanced Object Detection. In Proceedings of the NAECON 2024—IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, Dayton, OH, USA, 15–18 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latief, A.D.; Jarin, A.; Yaniasih, Y.; Afra, D.I.N.; Nurfadhilah, E.; Pebiana, S. Latest Research in Data Augmentation for Low Resource Language Text Translation: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer, Control, Informatics and Its Applications (IC3INA), Bandung, Indonesia, 9–10 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Burridge, J.; Blok, P.M.; Guo, W. A Patch-Level Data Synthesis Pipeline Enhances Species-Level Crop and Weed Segmentation in Natural Agricultural Scenes. Agriculture 2025, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadesmaeilketabforoosh, K.; Parfitt, J.; Nikan, S.; Pearce, J.M. From blender to farm: Transforming controlled environment agriculture with synthetic data and SwinUNet for precision crop monitoring. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, B.B.; Popescu, S.; Rajan, N.; Leon, R.G.; Reberg-Horton, C.; Mirsky, S.; Bagavathiannan, M.V. Use of synthetic images for training a deep learning model for weed detection and biomass estimation in cotton. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumoglou, N.; Pechlivani, E.M.; Tzovaras, D. Generate-Paste-Blend-Detect: Synthetic dataset for object detection in the agriculture domain. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 5, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, H. ObjectDetection in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pavlick, E. Does Training on Synthetic Data Make Models Less Robust? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.07164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. YOLO by Ultralytics, Version 8.0.0. Computer Software. Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, K.; Chahl, J. A Review of Synthetic Image Data and Its Use in Computer Vision. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkman, S.; Crespi, A.; Dhakad, S.; Ganguly, S.; Hogins, J. Unity Perception: Generate Synthetic Data for Computer Vision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.04259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plum, F.; Bulla, R.; Beck, H.K. replicAnt: A pipeline for generating annotated images of animals in complex environments using Unreal Engine. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, I.; Qiu, W.; Hager, G.; Yuille, A. Learning from Synthetic Animals. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.08265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J.; Fong, R.; Ray, A.; Schneider, J.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Domain Randomization for Transferring Deep Neural Networks from Simulation to the Real World. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Dong, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xu, D.; Xu, F.; Chen, F. Wildlife Real-Time Detection in Complex Forest Scenes Based on YOLOv5s Deep Learning Network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klukowski, D.; Lubczonek, J.; Adamski, P. A Method of Simplified Synthetic Objects Creation for Detection of Underwater Objects from Remote Sensing Data Using YOLO Networks. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.W. Flocks, Herds, and Schools: A Distributed Behavioural Model. In ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 21, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koger, B.; Deshpande, A.; Kerby, J.T.; Graving, J.M.; Costelloe, B.R.; Couzin, I.D. Quantifying the movement, behaviour and environmental context of group-living animals using drones and computer vision. J. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DetReIDx Dataset Page. Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/detreidxv1 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Geng, W.; Yi, J.; Li, N.; Ji, C.; Cong, Y.; Cheng, L. RCSD-UAV: An object detection dataset for unmanned aerial vehicles in realistic complex scenarios. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 151, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucervus, D. Duvaucelii (Barasingha) UAV Dataset. Mendeley Data (Version 1). Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/53nvjhh5pg/1 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Romero, A.; Carvalho, P.; Côrte-Real, L.; Pereira, A. Synthesizing Human Activity for Data Generation. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, L.; Gupta, A.; Kaveti, P.; Singh, H.; Ostadabbas, S. Bridging the Domain Gap between Synthetic and Real-World Data for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.02631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epic Games. UE5 Lumen Global Illumination and Reflections—Technical Documentation. Available online: https://docs.unrealengine.com/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Shah, S.; Dey, D.; Lovett, C.; Kapoor, A. AirSim: High-Fidelity Visual and Physical Simulation for Autonomous Vehicles. In Field and Service Robotics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. ByteTrack: Multi-Object Tracking by Associating Every Detection Box. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Pang, J.; Weng, X.; Khirodkar, R.; Kitani, K. Observation-Centric SORT: Rethinking SORT for Robust Multi-Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 9686–9696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiten, J.; Osep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. HOTA: A Higher Order Metric for Evaluating Multi-Object Tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristani, E.; Tomasi, C. Features for Multi-Target Multi-Camera Tracking and Identification. In CVPR Workshops 2016; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.J.; Patel, P.; Tesch, J.; Yang, J. BEDLAM: A Synthetic Dataset of Bodies Exhibiting Detailed Lifelike Animated Motion. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.16940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voudouris, K.; Slater, B.; Cheke, L.G.; Schellaert, W.; Hernández-Orallo, J.; Halina, M.; Patel, M.; Alhas, I.; Mecattaf, M.G.; Burden, J.; et al. The Animal-AI Environment: A virtual laboratory for comparative cognition and artificial intelligence research. Behav. Res. 2025, 57, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Training Data | YOLOv8s | YOLOv11s | RT-DETR-L |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimizer | SGD | SGD | AdamW |

| LR0 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0005 |

| LR schedule | Cosine, lrf = 0.01 | Cosine, lrf = 0.01 | Cosine, lrf = 0.01 |

| Epochs max | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Input size | 640 px, 1280 px | 1280 px | 1280 px |

| Batch size | 16 (640 px), 8 (1280 px) | 8 | 2 |

| Patience | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Mosaic | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Multi-scale | True | True | True |

| HSV aug | h = 0.015, s = 0.60, v = 0.45 | h = 0.015, s = 0.60, v = 0.45 | h = 0.015, s = 0.60, v = 0.45 |

| Flip | fliplr = 0.5, flipud = 0.0 | fliplr = 0.5, flipud = 0.0 | fliplr = 0.5, flipud = 0.0 |

| Training Data | Best Epoch | mAP@[0.5:0.95] | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic-only @640px | 50 | 0.54155 | 0.91315 | 0.79816 |

| Real-only (COCO-pretrained) @640px | 44 | 0.41528 | 0.79452 | 0.65988 |

| Fine-tune on real (100%) @640px | 29 | 0.39844 | 0.76439 | 0.65836 |

| Synthetic-only @1280px | 50 | 0.78639 | 0.97145 | 0.96506 |

| Real-only (COCO-pretrained) @1280px | 32 | 0.45855 | 0.78235 | 0.71199 |

| Model and Training Regime | Architecture | Best Epoch | mAP@[0.5:0.95] | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8s, Real-only @1280px | Conv | 32 | 0.45855 | 0.78235 | 0.71199 |

| YOLOv8s, Synth-init + 50% real @1280px | Conv | 48 | 0.41039 | 0.81112 | 0.68991 |

| YOLO11n, Real-only @1280px | Conv | 50 | 0.42218 | 0.77811 | 0.68454 |

| YOLO11n, Synth-init + 50% real @1280px | Conv | 43 | 0.41397 | 0.78979 | 0.67918 |

| RT-DETR-L, Real-only @1280px | Transformer | 49 | 0.13015 | 0.35401 | 0.44637 |

| RT-DETR-L, Synth-init + 50% real @1280px | Transformer | 43 | 0.30661 | 0.73381 | 0.62875 |

| Training Data | Best Epoch | mAP@[0.5:0.95] | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-tune on 10% real data | 46 | 0.27755 | 0.77108 | 0.4877 |

| Fine-tune on 20% real data | 43 | 0.27939 | 0.75038 | 0.52061 |

| Fine-tune on 30% real data | 50 | 0.34109 | 0.76294 | 0.60568 |

| Fine-tune on 40% real data | 49 | 0.36611 | 0.74702 | 0.64646 |

| Fine-tune on 50% real data | 48 | 0.41039 | 0.81112 | 0.68991 |

| Fine-tune on 60% real data | 45 | 0.41888 | 0.79945 | 0.67224 |

| Fine-tune on 70% real data | 45 | 0.41245 | 0.79386 | 0.67445 |

| Fine-tune on 80% real data | 47 | 0.42014 | 0.7914 | 0.66909 |

| Fine-tune on 90% real data | 43 | 0.40672 | 0.78067 | 0.68157 |

| Fine-tune on 100% real data | 50 | 0.41213 | 0.77049 | 0.69117 |

| Synthetic-only | 50 | 0.78639 | 0.97145 | 0.96506 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Taskina, L.; Vorobyev, K.; Abakumov, L.; Kazarkin, T. BEHAVE-UAV: A Behaviour-Aware Synthetic Data Pipeline for Wildlife Detection from UAV Imagery. Drones 2026, 10, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010029

Taskina L, Vorobyev K, Abakumov L, Kazarkin T. BEHAVE-UAV: A Behaviour-Aware Synthetic Data Pipeline for Wildlife Detection from UAV Imagery. Drones. 2026; 10(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaskina, Larisa, Kirill Vorobyev, Leonid Abakumov, and Timofey Kazarkin. 2026. "BEHAVE-UAV: A Behaviour-Aware Synthetic Data Pipeline for Wildlife Detection from UAV Imagery" Drones 10, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010029

APA StyleTaskina, L., Vorobyev, K., Abakumov, L., & Kazarkin, T. (2026). BEHAVE-UAV: A Behaviour-Aware Synthetic Data Pipeline for Wildlife Detection from UAV Imagery. Drones, 10(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10010029