1. Introduction

The progression of technology has greatly improved the ability to measure the game of tennis. Early work focused on physical interactions of the ball and racket in isolation [

1,

2] or on player movement in controlled conditions [

3,

4]. As technology developed, sophisticated measurements of racket movement could be made during free-play (non-competitive) conditions [

5]. However, in all cases, data was collected non-routinely as part of a specific research investigation.

In the modern era, technology allows sophisticated ball and player tracking during competition conditions. This data is collected routinely as part of the Hawk-Eye™ Electronic Line-calling System (ELS) which is used at many competitions and has given players the ability to challenge line-calling decisions. The camera-based system automatically detects the ball and players during play and calculates their position with relation to the court—giving metrics such as velocities, bounce locations and flight trajectories. The data is used to generate match-statistics during play but has also been used in scientific research. The large datasets formed over the course of tournaments have given sports engineers new tools for analysing and understanding the effects of equipment on sporting performance. A number of authors have used data captured by the Hawkeye system to investigate aspects of Tennis. Whiteside et al. [

6] examined metrics that distinguish between lower and higher ranked players in the Australian Open. Lane et al. [

7] looked for differences in ball performance during ball degradation. Wei et al. used sophisticated modelling and statistical techniques to try to predict shot outcomes [

8,

9,

10].

A Hawk-Eye dataset is not as detailed as previous research—it contains no player joint angles or racket movements. However, because the data is captured during competition it can be used to reveal aspects of the game which are difficult to quantify using conventional means.

The aerodynamic effects of ball wear have been investigated by several authors. The predominant method of quantifying aerodynamic performance has been the wind-tunnel. Wear has been simulated through abrasion or shaving of the felt [

11] or by using balls which have been used in play [

12]. Current consensus is that a ‘used’ tournament ball (9 games of play) has reduced aerodynamic drag due to wearing of the felt [

13]. The Hawk-Eye dataset allows us to investigate the effect of wear on the aerodynamics of the tennis ball and the associated effects on play. This investigation will not use wind-tunnel data but infer ball properties from the recorded trajectories contained within the Hawk-Eye dataset.

Our aim was to identify and quantify changes in ball aerodynamics which results from ball wear.

2. Methods

A dataset was formed from Hawk-Eye data recorded during 354 matches of the Davis and Fed Cup tournaments (2012 to 2017), it comprised 71,019 points in total.

The data was organized in a hierarchy of data tables, match→point→shot. The match table contained meta-data about the match itself (players, tournament, dates etc.), the point table contained information regarding the flow of the game (identity of server, current score, point winner etc.). The shot data table was the largest and contained detailed information regarding the physical characteristics of a shot—summarized in

Figure 1.

In tournament play a new set of 6 balls is introduced after the first 7 games of play and after every following 9 games. The games in the dataset were counted to identify the points of play when balls were changed. A new ball was defined as a ball used in the first two games following a change. A used ball was defined as a ball used in the last two games preceding a change. Shots were tagged according to whether the ball used was new or used. Balls which were neither new or used were not used in this research.

On average, 235 racket impacts were made between ball changes—39 per ball. This tallies closely with other research, Lane et al. found 318 racket impacts, on average, every 9 games [

7],

Figure 2 shows the distribution within the dataset.

The aerodynamic performance of new and used balls was explored by examining first serves—a relatively constrained delivery compared to open play. Second serves were discounted because they tend to be hit with large amounts of spin [

14].

The dataset was filtered to include only male players (to examine higher speed shots) and exclude tie-breaks (which were counted as one game in the data). In total, 4651 serves were made with new balls, 4573 serves were made with used balls.

The aerodynamic properties of the balls were assessed by calculating the average deceleration of the ball in the period from racket impact until contact with the court. To simplify calculations, gravity was discounted by only considering the horizontal components of velocity. Coefficients of drag (Cd) for new and used balls were calculated by simulating the flight of each serve.

A trajectory model was created in Matlab which accounted for deceleration due to aerodynamic drag,

, the density of air was assumed to be 1.2 kg/m

3, the frontal area was equivalent to a tennis ball of 6.7 cm diameter and mass was 58 grams. Coefficient of drag was assumed to be constant throughout the flight, this assumption was deemed suitable; previous authors have found C

d to be relatively stable above speeds typical in the serve [

13] and as a gross representation of aerodynamic drag a constant value is suitable for the aims of this research.

Each serve in the database was simulated by using the horizontal serve velocity in the trajectory model. The model was run for the same time as the serve in the database (i.e., the time between racket impact and court impact). An error between simulation and the data was formed from the difference between the distance travelled by the ball in the simulated serve and as recorded in the database.

The error between the simulation and data was minimized by systematically altering the coefficient of drag values using a minimization algorithm based on golden section search [

15] (Matlab’s ‘fminbnd’ function). The Cd for each serve was calculated individually.

The coefficient of drag (as given by simulation), time to impact and serve speeds (from the data) were analysed to determine whether they differed between new and used balls. Significance was assessed using unpaired t-tests.

3. Results

Serve speeds were 0.27 m s−1 higher for new balls (p = 0.012). While the effect is small, new balls were travelling 0.79 m s−1 faster by the time they reached the court surface (p < 0.0001). The new balls reached the court 0.0074 s sooner than used balls (p = 0.0091) on average.

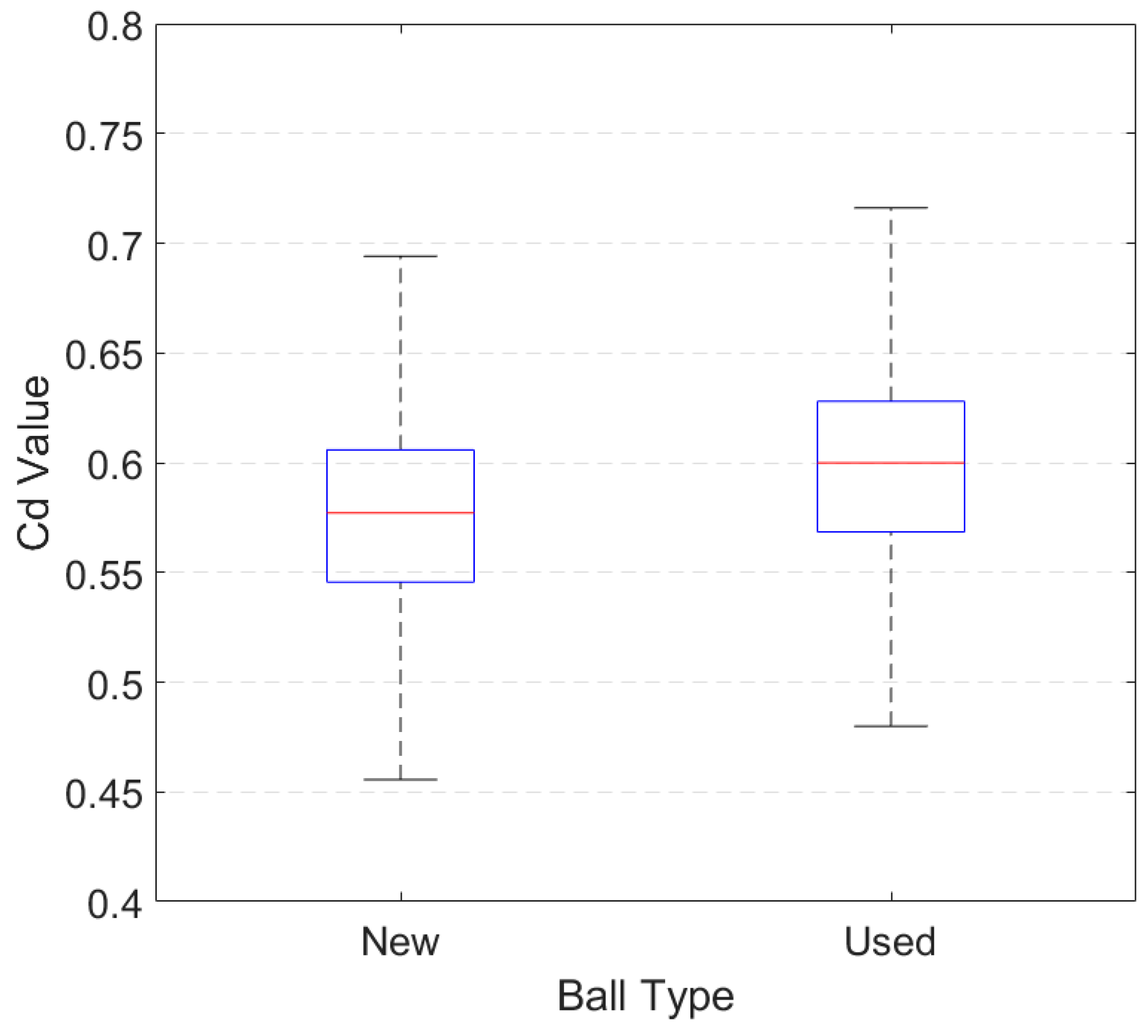

As calculated, the mean Cd value of new balls was 0.579 and the mean Cd value of used balls was significantly higher at 0.603 (

p < 0.0001), a 4.15% increase.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of Cd values for new and used balls.

4. Discussion

In the first serve, new balls slow down less than used balls. Previous research has shown that the aerodynamics of a tennis ball change due to wear [

11,

12] and that the felt is an important component of drag. Wind tunnel tests show aerodynamic drag to increase when the felt’s filaments are raised and decrease when the filaments are shaved [

11]. Wind tunnel tests show the coefficient of drag to be between 0.55 and 0.68 (depending on the condition of the tennis ball).

The slightly higher values for new balls in wind-tunnel studies (>0.6 as opposed to 0.579 on average in this study) could be due to assumptions we made regarding air density and ball diameter which were not measured directly.

The results of this study show that in the Davis Cup, a used tennis ball has higher aerodynamic drag than a new ball. This suggests that the felt of a used ball is raised and not worn down. Mehta and Pallis tested a ball from the US Open that had been played in 9 games of competition. The ball had significant wear and demonstrated a large reduction in coefficient of drag compared to the unused condition—this is contrary to the findings of this study. A possible explanation is that wear was more accelerated than is typical in the Davis Cup. However, both tournaments use a hardcourt surface so this could be an anomaly (only a single ball was tested in the wind-tunnel). In the wind-tunnel study, the reduction in drag was found after 9 full games, it is possible that the wearing of felt filaments observed by Mehta and Pallis occurred in the latter stages of play—the corresponding reduction in drag would not have time to affect the playing data before the balls were changed.

The small difference in aerodynamic drag we observed results in new balls reaching the court 0.0074 s sooner than used balls. This may present a small advantage to the server, as the receiving player less time to react. In the Hawk-Eye data, 96.5% of games played with new balls were won by the server, dropping to 86.3% of games played with used balls. It could be that new balls give the server a psychological advantage, further study is required to isolate the psychological and physical effects; an earlier study suggests that new balls do not provide an advantage to the server [

16]. This study used the results of games and matches only, so it is not possible to determine whether the aerodynamic properties of the balls changed in the same way during play; the data was from Wimbledon so it is possible that the grass surface affected the balls in a different way to the hard courts of the Davis Cup.

While large datasets such as these have benefits, there are also limitations. It is likely that wear rates are uneven, that certain balls from the set were used more frequently than others and that air pressures varied according to the venues in the database. This could be improved in future studies by supplementing the database with additional information, but this is unlikely in the short to medium term. With the development of markerless motion capture techniques, it is possible that future datasets could contain more detailed information such as player joint angles [

17].

We have observed a large range of racket impacts between ball changes (

Figure 2), future work should focus on accounting for this in the analysis. It would be useful to know whether this approach is able to detect more subtle difference in aerodynamic behaviour. This dataset only includes impacts on a hard-court surface. This work should be repeated with data from tournaments played on different surfaces.

5. Conclusions

In the Davis Cup, aerodynamic drag increases due to ball wear. The likely mechanism is a raising of the felt filaments during the wear process. This research shows the power of large datasets. Despite the relative lack of precision in the Hawk-Eye data, a small difference in aerodynamic properties can be inferred due to the large number of results. This has a number of advantages; the data is obtained during competitive play and findings are not restricted to investigations of physical properties but can be combined with tactical decisions and player movement. Future studies should exploit the richness of large sport datasets to explore representative physical and tactical behaviours.