Observing the Spectral Collapse of Two-Photon Interaction Models †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

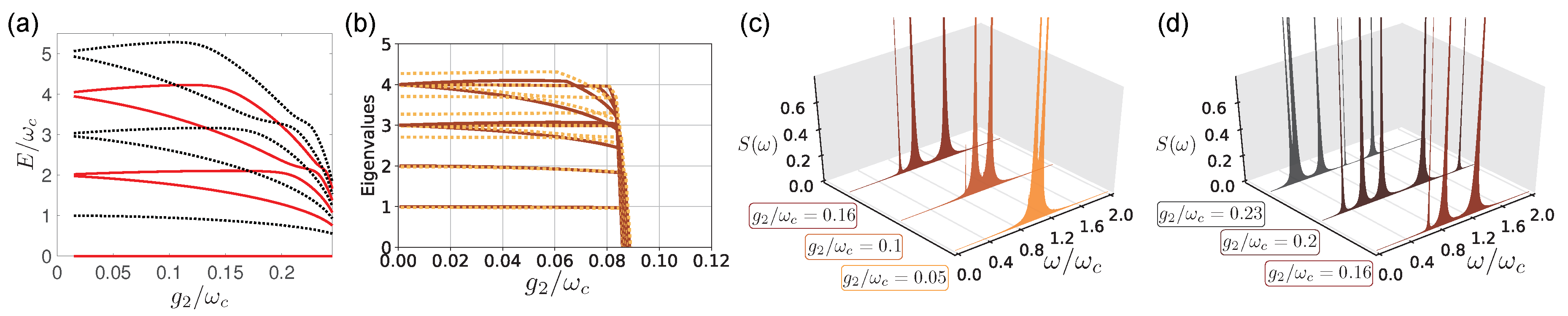

2. The Spectral Collapse

3. Fluorescence Spectrum

4. Concusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forn-Díaz, P.; Lamata, L.; Rico, E.; Kono, J.; Solano, E. Ultrastrong coupling regimes of light-matter interaction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2019, 91, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travenec, I. Solvability of the two-photon Rabi Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 043805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, V.V.; Scholes, G.D.; Brumer, P. Symmetric rotating-wave approximation for the generalized single-mode spin-boson system. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 042110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Xie, Y.-F.; Braak, D.; Chen, Q.-H. Two-photon Rabi model: Analytic solutions and spectral collapse. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2016, 49, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Cao, J.-P.; Fan, H.; Amico, L. Exact analysis of the spectral properties of the anisotropic two-bosons Rabi model. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2017, 50, 204001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, E.; Napoli, A.; Messina, A.; Solano, E.; Egusquiza, I.L. A continued fraction based approach for the Two-photon Quantum Rabi Model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Z.-J.; Cong, L.; Sun, X. Quantum phase transition and spontaneous symmetry breaking in a nonlinear quantum Rabi model. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.08128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Xie, Y.-F.; Chen, Q.-H. Solutions to the mixed quantum Rabi model. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.02676. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L.; Sun, X.-M.; Liu, M.; Ying, Z.-J.; Luo, H.-G. Polaron picture of the two-photon quantum Rabi model. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 013815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, L.; Egusquiza, I.L.; Solano, E.; Ciuti, C.; Coudreau, T.; Milman, P.; Felicetti, S. Superradiant phase transition in the ultrastrong-coupling regime of the two-photon Dicke model. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 053854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y. Finite-size scaling analysis in the two-photon Dicke model. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 053821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Piazza, A.; Müller, C.; Hatsagortsyan, K.Z.; Keitel, C.H. Extremely high-intensity laser interactions with fundamental quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicetti, S.; Pedernales, J.S.; Egusquiza, I.L.; Romero, G.; Lamata, L.; Braak, D.; Solano, E. Spectral collapse via two-phonon interactions in trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 033817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puebla, R.; Hwang, M.-J.; Casanova, J.; Plenio, M.B. Protected ultrastrong coupling regime of the two-photon quantum Rabi model with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 063844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeweiss, P.; Dareau, A.; Sayrin, C. Cold-atom based implementation of the quantum Rabi model. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 021801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-H.; Arrazola, I.; Pedernales, J.S.; Lamata, L.; Chen, X.; Solano, E. Nonlinear quantum Rabi model in trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 023624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedernales, J.S.; Beau, M.; Pittman, S.M.; Egusquiza, I.L.; Lamata, L.; Solano, E.; del Campo, A. Dirac Equation in (1+1)-Dimensional Curved Spacetime and the multiphoton quantum rabi model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 160403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, C.J.; Rossatto, D.Z. Multiphoton Jaynes-Cummings Model: Arbitrary Rotations in Fock Space and Quantum Filters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 123604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felicetti, S.; Rossatto, D.Z.; Rico, E.; Solano, E.; Forn-Díaz, P. Two-photon quantum Rabi model with superconducting circuits. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 013851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicetti, S.; Hwang, M.-J.; le Boité, A. Ultrastrong coupling regime of non-dipolar light-matter interactions. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 053859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaako, T.; Xiang, Z.-L.; Garcia-Ripoll, J.J.; Rabl, P. Ultrastrong-coupling phenomena beyond the Dicke model. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 033850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolfo, A.; Leib, M.; Savasta, S.; Hartmann, M.J. Photon Blockade in the Ultrastrong Coupling Regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 193602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Boité, A.; Hwang, M.J.; Plenio, M.B. Metastability in the driven-dissipative Rabi model. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 023829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Felicetti, S.; Boité, A.L. Observing the Spectral Collapse of Two-Photon Interaction Models. Proceedings 2019, 12, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019012041

Felicetti S, Boité AL. Observing the Spectral Collapse of Two-Photon Interaction Models. Proceedings. 2019; 12(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019012041

Chicago/Turabian StyleFelicetti, Simone, and Alexandre Le Boité. 2019. "Observing the Spectral Collapse of Two-Photon Interaction Models" Proceedings 12, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019012041

APA StyleFelicetti, S., & Boité, A. L. (2019). Observing the Spectral Collapse of Two-Photon Interaction Models. Proceedings, 12(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019012041