Evaluation of Food Technologies and Farmers’ Practices Related to Sorghum Cultivation in Central and Northern Benin †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

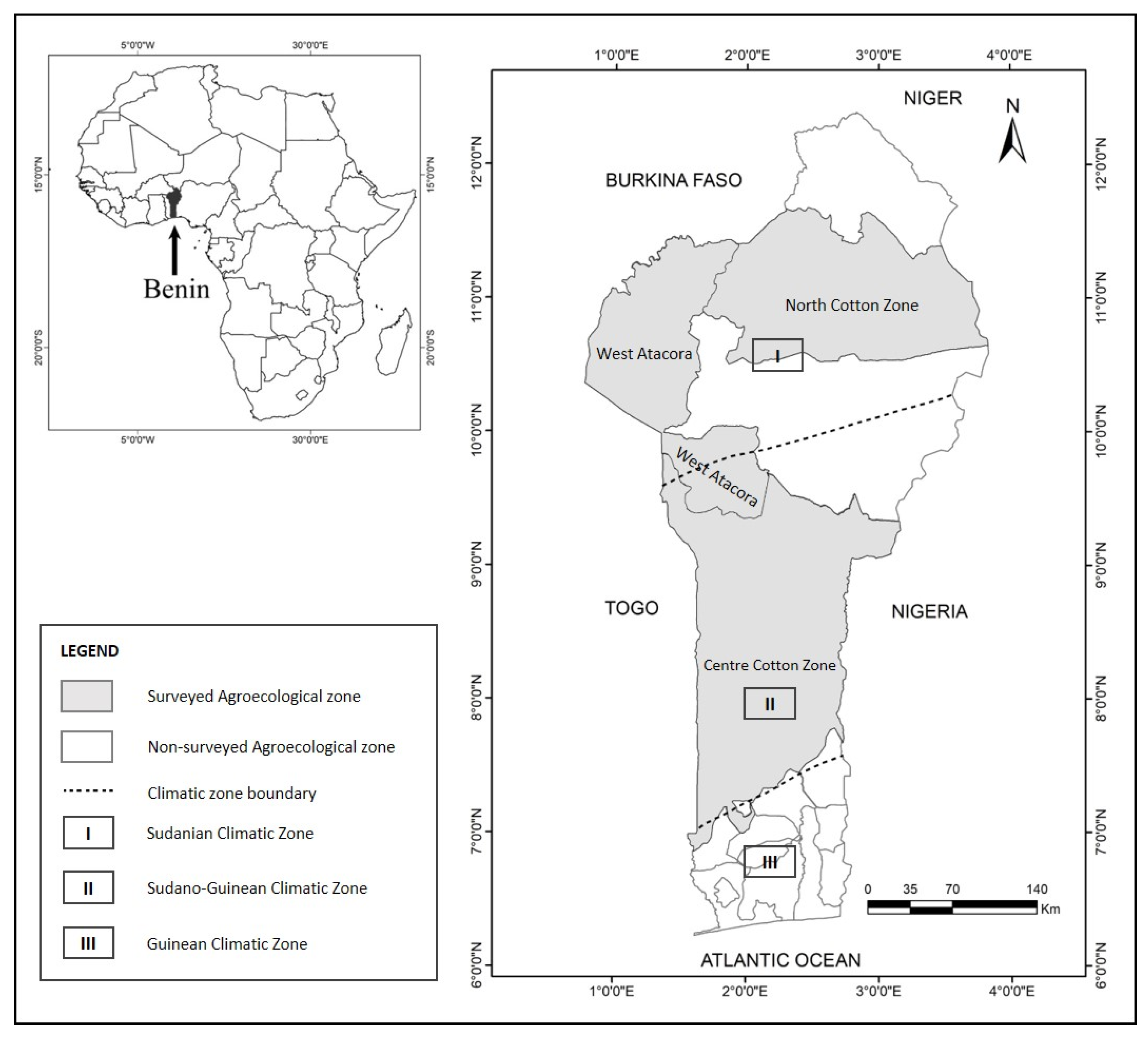

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Method

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Categories and Forms of Sorghum Use in Central and Northern Benin

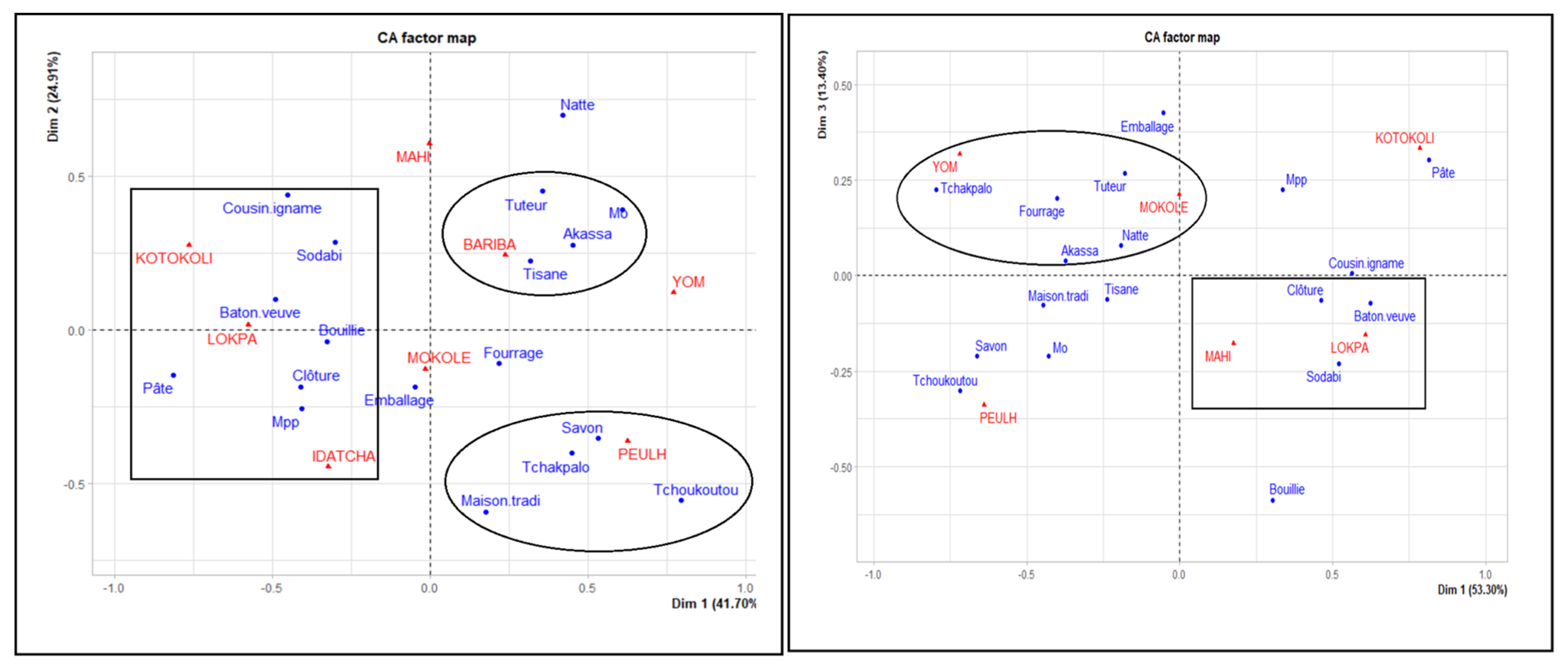

3.3. Relationship Between the Different Categories and Forms of Sorghum Use and the Different Sociocultural Groups of Northern and Central Benin

3.4. Relationship Between the Parts of the Plant Used and the Sociocultural Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kangama, C.O. Importance of Sorghum Bicolor in African’s Cultures. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2017, 6, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Proietti, I.; Frazzoli, C.; Mantovani, A. Exploiting Nutritional Value of Staple Foods in the World’s Semi-Arid Areas: Risks, Benefits, Challenges and Opportunities of Sorghum. Healthcare 2015, 3, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, B.; Guan, K.; Kouressy, M.; Biasutti, M.; Piani, C.; Hammer, G.L.; McLean, G.; Lobell, D.B. Robust Features of Future Climate Change Impacts on Sorghum Yields in West Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouzou, K.A.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Naab, J.B.; Borgemeister, C.; Vlek, P.L.G.; Becker, M. Climate Change Impact on Water- and Nitrogen-Use Efficiencies and Yields of Maize and Sorghum in the Northern Benin Dry Savanna, West Africa. Field Crops Res. 2019, 235, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helida, A.; Zuhud, E.A.; Hardjanto, H.; Purwanto, Y.; Hikmat, A. Index of Cultural Significance as a Potential Tool for Conservation of Plants Diversity by Communities in The Kerinci Seblat National Park. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. J. Trop. For. Manag. 2015, 21, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supiandi, M.I.; Mahanal, S.; Zubaidah, S.; Julung, H.; Ege, B. Ethnobotany of Traditional Medicinal Plants Used by Dayak Desa Community in Sintang, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2019, 20, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masengo, C.A.; Bongo, G.N.; Robijaona, B.; Ilumbe, G.B.; Koto-Te-Nyiwa, J.-P.N.; Mpiana, P.T. Étude ethnobotanique quantitative et valeur socioculturelle de Lippia multiflora Moldenke (Verbenaceae) à Kinshasa, République Démocratique du Congo. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét. 2021, 9, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sourabie, S.; Zerbo, P.; Yonli, D.; Boussim, J.I. Connaissances Traditionnelles Des Plantes Locales Utilisées Contre Les Bio-Agresseurs Des Cultures et Produits Agricoles Chez Le Peuple Turka Au Burkina Faso. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2020, 14, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloukoi, J.; Yabi, I.; Houssou, C.S. Perceptions et Stratégies Paysannes d’adaptation à La Variabilité Pluviométrique Au Centre Du Bénin. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hu, R.; Lin, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Plants Used by Mulam People in Guangxi, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2020, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjiba, S.T.C.; Adegbola, Y.P.; Yabi, J.A. Genre, Diffusion et Adoption Des Technologies de Gestion Durable Des Terres Dans Les Petites Exploitations Familiales Des Pays En Voie de Développement: Une Revue: Gender, Diffusion and Adoption of Sustainable Land Management Technologies in Small Family Farms in Developing Countries: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2022, 15, 2118–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikuku, K.M. Information Exchange Links, Knowledge Exposure, and Adoption of Agricultural Technologies in Northern Uganda. World Dev. 2019, 115, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, P.P.; Addison, M.; Wongnaa, C.A. Assessment of Impact of Adoption of Improved Cassava Varieties on Yields in Ghana: An Endogenous Switching Approach. Cogent Econ. Finance 2022, 10, 2008587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiarena, M.L.; Temudo, M.P. Endogenous Learning and Innovation in African Smallholder Agriculture: Lessons from Guinea-Bissau. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2023, 30, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, M. Sanni Cadre de Gestion Environnementale et Sociale; Ministère de l’Agriculture de l’Elevage et de la Pêche: Cotonou, Bénin, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dossou-Aminon, I.; Dansi, A.; Ahissou, H.; Cissé, N.; Vodouhè, R.; Sanni, A. Climate Variability and Status of the Production and Diversity of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) in the Arid Zone of Northwest Benin. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2016, 63, 1181–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnélie, P. Statistiques Théoriques et Appliquées; De Boeck: Bruxelles, Belgique, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chantereau, J.; Cruz, J.-F.; Ratnadass, A.; Trouche, G.; Fliedel, G. Le Sorgho; éditions Quae: Versailles, France, 2013; ISBN 978-2-7592-2062-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dabija, A.; Ciocan, M.E.; Chetrariu, A.; Codină, G.G. Maize and Sorghum as Raw Materials for Brewing, a Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A. African Sorghum-Based Fermented Foods: Past, Current and Future Prospects. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djohy, G.L.; Bouko, B.S.; Djohy, G.; Dossou, P.J.; Yabi, J.A. Contribution des résidus de culture à la réduction du déficit alimentaire des troupeaux de ruminants dans l’Ouémé Supérieur au Bénin. Cah. Agric. 2023, 32, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuistion, K.C.; Selle, P.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Goodband, R.D. Sorghum as a Feed Grain for Animal Production. Sorghum and Millets; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 355–391. ISBN 978-0-12-811527-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, J. The Role of Sorghum in Renewables and Biofuels. Sorghum: Methods and Protocols; Zhao, Z.-Y., Dahlberg, J., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 269–277. ISBN 978-1-4939-9039-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.S.; Vinutha, K.S.; Kumar, G.S.A.; Chiranjeevi, T.; Uma, A.; Lal, P.; Prakasham, R.S.; Singh, H.P.; Rao, R.S.; Chopra, S.; et al. Sorghum: A Multipurpose Bioenergy Crop. In Agronomy Monographs; Ciampitti, I.A., Vara Prasad, P.V., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2019; pp. 399–424. ISBN 978-0-89118-628-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stefoska-Needham, A.; Beck, E.J.; Johnson, S.K.; Tapsell, L.C. Sorghum: An Underutilized Cereal Whole Grain with the Potential to Assist in the Prevention of Chronic Disease. Food Rev. Int. 2015, 31, 401–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu, F.K.; Elahi, F.; Daliri, E.B.-M.; Yeon, S.-J.; Ham, H.J.; Kim, J.-H.; Han, S.-I.; Oh, D.-H. Flavonoids in Decorticated Sorghum Grains Exert Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Antiobesity Activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricas, N. Cadre Conceptuel et Méthodologique Pour L’analyse de la Consommation Alimentaire Urbaine en Afrique; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 1998; 48p. [Google Scholar]

- Kayodé, A.P.; Linnemann, A.R.; Nout, M.R.; Hounhouigan, J.D.; Stomph, T.J.; Smulders, M.J. Diversity and Food Quality Properties of Farmers’ Varieties of Sorghum from Bénin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sop, T.K.; Oldeland, J.; Bognounou, F.; Schmiedel, U.; Thiombiano, A. Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Valuation of Woody Plants Species: A Comparative Analysis of Three Ethnic Groups from the Sub-Sahel of Burkina Faso. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assogba, G.A.; Fandohan, A.B.; Salako, V.K.; Assogbadjo, A.E. Usages de Bombax Costatum (Malvaceae) Dans Les Terroirs Riverains de La Réserve de Biosphère de La Pendjari, République Du Bénin. Bois Forets Trop. 2017, 333, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houètchégnon, T.; Gbèmavo, D.S.J.C.; Ouinsavi, C.A.I.N.; Sokpon, N. Structural Characterization of Prosopis Africana Populations (Guill., Perrott., and Rich.) Taub in Benin. Int. J. For. Res. 2015, 2015, 101373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regions of Benin | Sociocultural Groups | Absolute Frequencies | Relative Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Bariba | 13 | 4.50 |

| Idacha | 38 | 13.15 | |

| Mahi | 19 | 6.57 | |

| Peulh | 10 | 3.46 | |

| Total | Total | 80 | 27.68 |

| Northern | Kotokoli | 12 | 4.15 |

| Lokpa | 11 | 3.81 | |

| Bariba | 75 | 25.95 | |

| Mokolé | 10 | 3.46 | |

| Fulani | 34 | 11.76 | |

| Peulh | 20 | 6.92 | |

| Yom | 47 | 16.26 | |

| Total | - | 209 | 72.32 |

| Total surveyed | - | 289 | 100 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 244 | 84.43 |

| Female | 45 | 15.57 | |

| Ages | 18 to 30 years (young) | 32 | 11.07 |

| 31 to 60 years (adults) | 235 | 81.31 | |

| Over 60 years old (elderly) | 22 | 7.61 | |

| Education level | Primary | 31 | 10.73 |

| Secondary | 14 | 4.84 | |

| None | 244 | 84.43 | |

| Main activity | Agriculture | 286 | 98.96 |

| Livestock | 3 | 1.04 | |

| Trade | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Secondary activity | Livestock | 251 | 86.85 |

| Agriculture | 26 | 9.00 | |

| Trade | 12 | 4.15 | |

| Sorghum cultivation areas | <1 ha | 96 | 33.22 |

| ≥1 ha | 193 | 66.78 | |

| Categories of Use | Parts Used | Forms of Use | Number of Citations | FRC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Grains, leaves | Porridge | 283 | 97.92 |

| Paste | 265 | 91.69 | ||

| Fodder | 229 | 79.24 | ||

| Akassa | 117 | 40.48 | ||

| Feed | 88 | 30.45 | ||

| Beverage (traditional drinks) | Grains | Tchakpalo | 216 | 74.74 |

| Tchoukoutou | 182 | 62.98 | ||

| Sodabi | 75 | 25.95 | ||

| Agronomic | Stems, leaves | Organic fertilizer | 76 | 26.30 |

| Yam support | 71 | 24.57 | ||

| Cushions (yam) | 75 | 25.95 | ||

| Artisanal | Stems, leaves | Fence | 242 | 83.74 |

| Traditional houses | 160 | 55.36 | ||

| Mats | 168 | 58.13 | ||

| Cultural | Stems | Widow’s stick | 46 | 15.92 |

| Medicinal | Leaves | Malaria and anemia | 117 | 40.48 |

| Cosmetic | Stems, leaves | Soap | 86 | 29.76 |

| Packaging | 65 | 22.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Megnonhou, S.; Montcho, D.; Akpo, E.; Dandjlessa, J.; Kpocheme, A.O.E.K. Evaluation of Food Technologies and Farmers’ Practices Related to Sorghum Cultivation in Central and Northern Benin. Proceedings 2025, 118, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025118005

Megnonhou S, Montcho D, Akpo E, Dandjlessa J, Kpocheme AOEK. Evaluation of Food Technologies and Farmers’ Practices Related to Sorghum Cultivation in Central and Northern Benin. Proceedings. 2025; 118(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025118005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMegnonhou, Sylvain, David Montcho, Essegbemon Akpo, Judicaël Dandjlessa, and Adjaho Olatondji Eustache Kévin Kpocheme. 2025. "Evaluation of Food Technologies and Farmers’ Practices Related to Sorghum Cultivation in Central and Northern Benin" Proceedings 118, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025118005

APA StyleMegnonhou, S., Montcho, D., Akpo, E., Dandjlessa, J., & Kpocheme, A. O. E. K. (2025). Evaluation of Food Technologies and Farmers’ Practices Related to Sorghum Cultivation in Central and Northern Benin. Proceedings, 118(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025118005