1. Museum Didactics and Heritage Education

When didactics approaches artworks, museums, monuments and, more generally, culture places takes the name of “museum education” which can be defined as the range of methodologies and tools employed by museum institutions to make accessible works, exhibits, documents, sources, collections and exhibitions targeted at the general public [

1]. Just as didactics copes with an extraordinarily complex field, where it is difficult to grasp the regularity elements present in the structures of reality and consequently intervene in such structure by an analytical breakdown of variables, so also museum education is required to maintain a complex approach to investigation, necessary to connect all the elements typical of museum context. With reference to such features both social and intellectual practices become an integral part of the museum premises which are increasingly characterized as symbolic mediation spaces where people can share objects, gestures, attitudes and thoughts. Museum education, as a specific area of education, becomes—therefore—a mediation tool-place promoting a complex of planning, implementing and evaluating actions with a symbolic negotiation feature [

2]. Such activities develop processes of knowledge construction effectively through heritage objects, using specific training devices, properly selected and set up by competent museum educators. As a result the museum is recognised as the ownership of a training action, being thus a full educational and didactic place, a privileged space to “light” the culture of curiosity and visual enjoyment, where promoting creative and imaginative freedom open to the interpretation adventure, through the use of a wide range of languages [

3,

4].

Heritage education can be considered part of such context: education meant as an activity which, while educating to heritage knowledge and respect, set the very heritage as a research and interpretation object, by adopting the perspective of the active and responsible citizenship. The different learning and mediation models have definitely contributed to describe the educational function of heritage and museums in a broader sense, with a particular attention to visitors and to the meaning that they attribute to their own experience. Nevertheless the educational action to heritage does not consist uniquely in communicating the symbolic and cultural contents, or in the set of actions meant to consolidate the relationship between the public and the objects, yet and mostly in the possibility of reflecting on the identity of man and his community of belonging, which heritage is an expression of. This aspect points out how heritage experience cannot be considered just as an active methodology aiming at the knowledge of objects placed in specially set up places, yet it must be conceived and collocated within a problematizing pedagogy. Methods and strategies should guarantee educational excellence, with a continuous attention to man and community needs; thus education would become the final object of each heritage experience, not only the means through which the experience itself is carried out. In such a sense the museum becomes a welcoming place when it supports an opening attitude to the person through different educational dimensions, among which the intellectual, emotional-relational, ethic and aesthetic ones. Such opening, integrated with a design action, capable of promoting the necessary languages and tools, lets the museum become an institution able to guarantee an accessibility for all and each single person. This definition is reflected in particular in the very etymological meaning of the term heritage, defined as “ a complex of material and immaterial goods, of values with more or less far away origins, peculiar of one person, a community and a nation” (Zingarelli Italian Dictionary, 2011).

To go back to a first definition by UNESCO in 1972, heritage is described as a complex of “monumental paintings, plastic or architectural works of art, archeological elements or structures, inscriptions, caves and groups of elements of universal value, extraordinary from an historic, artistic or scientific point of view”, where above all the very substance of heritage is highlighted in terms of a closed system of immoveable sedimented complex of works of art of ‘universal value’, and consequently a heritage to be transmitted and retained. However, to such meaning, in 2003 UNESCO adds an additional reflection on the sense of heritage meant as “the set of practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, know-how—as well as the tools, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces associated to them—which the communities, the groups and, in some cases, the individuals recognise as a part of their own heritage. Such immaterial heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by the communities and groups in response to their environment, to their interaction with nature and history as well”. Heritage is therefore meant as a process, that is as a set of works in its developing to be “put back into circulation”, reconstructed in its meanings, relocated in an exchange social space; or as a resource to reflect, question, get to know each other, recognise and represent oneself as well as have relationships and grow.

2. The Role of the Audience: A Look at Young People

The museum can represent a privileged place for research for young people where to be guided, at first, to use the look as a sensory and intellectual “tool” necessary to discover the “signs” of the communicative messages and, secondly, to reflect and interpret the contents of works, exhibits, evidence of historical memory of past and recent times. According to such interpretation the museum becomes a workshop of experiences, where the history and meaning of works and the intellectual and sensory work of people meet, giving birth to original forms of knowledge. In relation to this specific field, the need is urgent to safeguard the sense of museum experience, whose activities refer not only to a museum meant as a single institution carrying out projects in special sections dedicated to didactics, but also operating within the cultural landscape where the museum is located. It is in fact through its very opening to society that the museum is defined and takes its shape thus becoming “house of culture in dialogue with the city” in the perspective of a cultural networked system which, starting from an itinerary within a specific museum, takes the visitor towards other museums, which, in turn, are connected to other local educational agencies: libraries, archives, playrooms and recreation centres.

In this way the city becomes the museum of museums, capable of spreading a sense of attachment and responsibility to heritage by all citizens, from children to young people. Therefore the discussion on the relationship between museums and young generations goes far beyond the reading of the single experiences carried out; yet it is important to see and consider how it is not the specific activity determining the educational characterisation of the museum rather the reference to theoretical and practical approaches which allow the identification of its educational dimensions. The need is highlighted for an educational experiential model of museums to be defined, having the sciences of Pedagogy and Education as its principal point of reference.

The role of the audience in heritage and museum contexts is central [

5]: the visitor represents a priority party, an active and integral part of the museum communication process, where the museum educator plays a strategic role. More specifically, the public, formed by students and young people in training, interacts, reinterprets and give meaning back to heritage, transforming it from a little known or rather unknown whole to a whole which can be adopted and thanks to which the past and the present can get in touch and talk; definitely the audience relates to it through multiple meanings and interpretations. Therefore heritage can become an essential tool to work in educational projects based also on imagination in order to build up stories told through objects. The most interesting aspect is that of changing “the order of things” as pointed out by Neil MacGregor in

A history of the world in 100 objects, according to which an impressive number of objects transforms, taking on different meanings, even a long time after their creation, allowing young people to read and interpret the modern world. The need for art and heritage education addressed mostly to young generations, stated in different international documents [

6], calls for a rethinking of educational professionalism engaged in different cultural contexts, such as museums, theatres, cinemas, libraries and archives and that daily interacts with different types of users among which young people play an outstanding role.

3. Mediators in Disability Contexts

If the central core of the teaching/learning relationship is the relationship between a meaningful adult and his/her students/minors, we can say that the responsibility of the relationship with the other is the structural dimension of teaching, and therefore also of those situations involving the museum educator’s activity [

7].

Didactics, in a broad sense, can therefore represent a place where familiarisation with persons with disabilities can take place, the situation where that direct getting in touch allows the mitigation of stereotypes, the evolution of personal and social representations and a realistic knowledge of disability [

8]. And we believe, as scholars and experts engaged in this field, that, within the contexts of belonging of everybody—schools, museums, theatres, cinemas, sports facilities—the reduction of handicap, for people with disabilities, can/must be accompanied by a similar reduction for those who have no such impairments. To our concern the pre-requisites for an inclusive education are the imagination of the adult and the person with disability’s getting involved in the situation where he/she is [

9]. H. von Foester reminds us that in the support relationship it is necessary

to believe in order to see, and not viceversa: it lies therefore in our capacity/ability as adults of dreaming, imagining, believing that a person with disability, even a serious one, can have an evolution; only such an operation can implement and give a positive feedback to our educational choices [

10].

And let’s not consider the capability of imagining just as an inborn feature: such ability needs training and experimenting, in order for the people involved to understand the limit of dreaming, too, without becoming almighty. This can be considered as the first and perhaps the most urgent form of disability reduction, viable in educational choices, in relation to which we must/can be committed, even inside a museum.

The

mediators can be people, objects, situations, contexts having a supporting role (temporary and/or permanent and/or cyclic) leading to further development in the persons involved [

11]. We wonder: is it possible to predict, design, develop and monitor mediators having an effective mediation between persons with disabilities and operators living difficult situations (even if partially or temporarily)? What is the meaning with which we connotate the word

mediator? If we start considering the very meaning of mediator as an illustrator of…, indicator of…, we can understand what an adult—specifically a museum operator—can do: he/she can illustrate, describe and tell other people—in a problematic situation with maybe some disabilities as well—something which the other person is not able to determine by him/herself. Infact such otherwise impossible experiences can be made accessible and ‘knowledgeable’ by the voice, hands, eyes and ears accompanying the exploration (also tactile); thanks to the closeness of this friendly presence, the mediator, the person with disabilities is introduced the artwork and the whole museum structure from a space, emotional and cognitive point of view. Indeed, in this way, a virtuous cycle is started intertwining systemic and reciprocal dimensions, where

mediators and

mediated (grant us such improper term) evolve together.

The research, through the analysis and comparison of training projects addressed mainly to museum operators, aims to detect the

relevant issues [

12] (pp. 8–9) so that it is possible to talk about

cultural mediators with educational competences. Specifically the study intends to outline what the most inclusive educational methodologies are in order for the museum operator to be able to fully promote visual and cultural heritage knowledge in schools, museums and local cultural contexts. This is meant to occur also through the use of more communicative mediators, thus defining some of the areas of high profile professional competence.

4. Heritage Usability: Taking Care of Accessibility

Article 6 of the Code of cultural Heritage and Landscape—Legislative Decree 22 January 2004, n.42 which contains the “Code of cultural Heritage and Landscape” in accordance with the intent of article 10 of Law n.6 July 2002, n.137—defines the promotion of cultural heritage as specified hereafter: “The promotion consists of the exercise of functions and regulations of the activities meant to promote heritage knowledge and to secure the best conditions of public usability and accessibility of the heritage itself, in order to promote culture development. It includes also the promotion and support to heritage conservation measures. With reference to landscape the appreciation consists also of the renovation of buildings and of the areas subject to protection, compromised or damaged, or the carrying out of new coherent and integrated landscape values”. The connection between appreciation and usability, highlighted by the above mentioned article, shows the promotion as an activity meant to improve heritage and environmental knowledge conditions and to increase their enjoyment.

At this point it is necessary to proceed to a clarification of the meaning of the term accommodation as it appears in article 2 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; such matching allows us to better understand the meaning of the term accessibility and of that, even broader, of universal design.

Article 2 of the UN Convention states what follows: “[...] Reasonable accommodation’ means necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or [...] undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms” (UN Convention, 2006, article 2).

The context is a potential resource that can allow the achievement of levels of realisation and autonomy for persons with disabilities; the central role of the context however excludes discrimination and on account of this implies an adjustment of the context itself to the specific needs of the person with disability. Examples of reasonable adjustments are the presence of a special needs teacher, with reference to school context, the ramps or other architectural solutions necessary to the overcoming of environmental barriers; reasonable adjustment is also the supply of information not only in paper format [

13].

The principle of universal design (Universal Design or Design for All) defined as “planning of goods and environments usable by all, in the broader sense possible, without special aids or adjustments”, was originally coined in architecture, in the late eighties, by the American architect Ronald Lawrence Mace, founder of the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University and today this model, includes every field where Information and Communication Technologies are used.

The UN Convention has spread a new perspective as to universal design, which is not limited to identifying a law dealing with the protection of the needs and requirements of a “disadvantaged” category of people, yet, instead, aligned with a vision of accessibility intended as a right of universal interest.

In the pedagogical field the inclusive approach underlying the principle of universal design is relevant: according to it is necessary to overcome the logic of the ‘special’ solution dedicated to the person with disability and the logic of the adaptation of the existing, in order to propose systems and methods making products, contexts and facilities usable and accessible to as many people as possible, setting out remarkable innovations in various fields and contexts.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom defined reasonable accomodation as the set of necessary and appropriate modifications and adjustments for persons with disabilities to be guaranteed the exercise and enjoyment of the human rights and fundamental freedoms under the principle of equality.

Ordinarily special solutions for people with disabilities should not be provided for but when you think of how to offer a good or a facility/service it is indispensable to consider also the individual needs involved, aiming at standard solutions, using extraordinary reasonable adjustment/adaptation only if really necessary. The concept of disproportionate burden is not to be meant as a financial cost and consequently too expensive, yet as the one implementing too many resources.

The perspective of universal design should not be limited to the identification of a rule addressed to the protection of a disadvantaged category of people’s needs, on the contrary, it should be aligned with a vision of accessibility intended as a right of universal interest. The idea of an accessible design or design-for-a-few should be overcome—as it appears in article 2 of the Convention specified hereafter—in order to propose a gradual passage from extraordinary adaptation to a universal design: “[...] “universal design” means the design of products, structures, programmes and services usable by all persons, to the greatest extent possible, without the need of specialised adaptations or design. Universal shall not exclude assistive devices for particular groups of persons with disabilities where this is needed (UN Convention 2). There is need for each person dealing with cultural heritage to accept and implement the following purpose: promoting a culture of accessibility, intended not only as a possibility of overcoming architectural, environmental, cultural obstacles for an easy use of cultural heritage and local interest areas, but like a wider possibility of implementing best practices [

14].

“This is the dynamic of the Good Practices and, therefore, a dynamic having as its basic element that of recognising a reality as a whole and not an [...] “amputed” reality. Cultural institutions, like museums, must make an effort and use every possible occasion (modernisation, maintenance, access to special funding, etc.) in order to develop an organisation based on good practices. [...] The person with disabilities themselves could have as a reference for the response to their needs a model not following the good practices standard and therefore they could ask, maybe with a certain urgency, just like when the request is fulfilled, special paths which cannot be integrated in the reorganisation: obtaining financial support, special devices, easy paths, and once more always referring to practices considered exceptional rather than standard and accepted; as a result it can be stated that persons with disabilities need getting involved in the design of good practices, in the understanding of the logic underlying the good practices, and must become protagonists of a realisation which goes a little beyond the immediate satisfaction of a need, because it requires not only the overcoming of the obstacle by any means, but also and above all the organisation allowing to reduce or eliminate organisational obstacles” [

15] (p. 300).

Nowadays the perspective of universal design may seem still far away and, for this reason, the solution related to adjustment design is dominant and not even given for granted; such designs tend to include all aspects of the overall accessibility to the working and living environment of the person with disabilities. An action of double protection is required: the first one addressed to culture and to the heritage related to it; the second one conceived for the individual modelling/enjoying it; it is necessary to protect both heritage and the man, because never are they incompatible.

5. The Competences of the Museum Educator: For a Training Model

The condition featuring the museum educator’s professional acting as a mediator is that of building up a reciprocal relationship with the different audiences through a negotiation-sharing of meanings and practices, aiming at finding a sense to the museum experience which is different for each person. With reference to the professionals operating in the museum at an educational level, it is relevant to point out that it is the Guidelines on the technical-scientific criteria and on the museum development and working standards of 2001 that define the professionalism of the Cultural operator. His/her specific acting consists in planning the educational activity aiming at valuing heritage, besides managing the didactic activity. A further development in this field is determined by the

National Guidelines for Museum professionals [

6] introducing the professional profiles of the Responsible for the Educational Services and of the Museum educator. In particular the museum educator is mainly engaged with designing and implementing the educational activities planned by the museum, with reference also to the needs of the different recipients, to the different field of competence related to knowledge, to relationship and strategies. In such a sense the educator is a learned, collaborative and technical specialist, providing knowledge related to the cultural heritage and/or collections and to the didactic methodologies necessary to meet visitors. It is in fact in accordance with his/her cooperation skills that the museum educator can establish meaningful relationships with different audiences and define the connections with different types of institutions/organisations (school and university groups, volunteering, business world). Besides the museum educator owns both theoretical and practical knowledge and performs specialised duties, among which customer care, besides the communication and dialogue skills in at least one foreign language and the use of technology, audiovisual and multimedia tools. In

Curricula Guidelines for Museum Professional Development, approved by ICOM in 2000, some guidelines are detected in relation to museum professional training and National Guidelines for museum educators, with the goal of emphasising the central role of museum professionals and to remedy the historical lack of definition of museum professionals [

16].

Such approach leads to detecting some competence-based elements of major impact for museum educators, thus summarised:

interdisciplinary knowledge;

psyco-pedagogic knowledge;

educational mediation methodologies;

relation strategies;

organization strategies;

research and development.

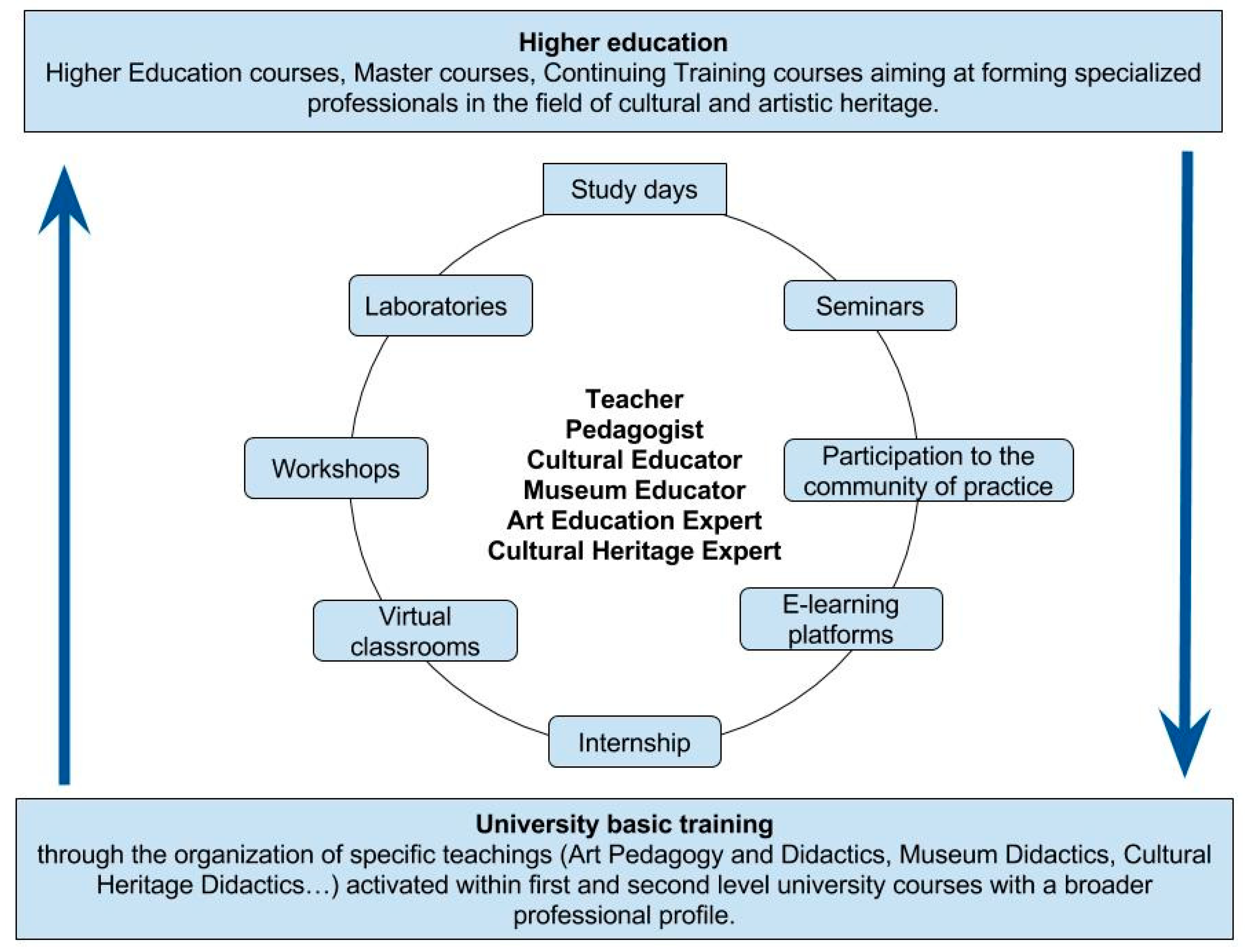

Such definition of competence can contribute to detect shared training paths towards an integrated training model for museum educators, according to which more educational professionals are involved, like teachers, pedagogists and art education experts (

Figure 1).

The museum educator, together with the teacher and through real situation analysis, will be increasingly required to build a possible panorama of the meaning of educating and training in relation to the continuous outcomes of studies and experimentations towards the development of a professional identity based on co-research processes, too.

6. Training and Disability: The Example of Paideia and CRT Foundation

“Museum operators and disability” is a training project born from the cooperation between CRT and Paideia Foundation, with the goal of increasing knowledge and implementing relational and professional competences of museum operators, in order to promote an inclusive and acceptance culture, with a special attention to the persons with disabilities. The project relies on a specific training addressed not only to the museum operators in the Turin and Piemonte area but to the whole national territory as well. It provides for the development of paths allowing a real implementation of the participants’ competences and skills in welcoming visitors with disabilities and special needs. The training proposal aims mainly at improving the knowledge related to disabilities, at implementing relational and professional competences, at better managing communication towards all users and at qualifying public communication. In short:

Improving the knowledge related to disabilities—When you speak of disability from a general point of view different characteristics, sometimes requiring completely different relational approaches, are instead included in the same category. Getting to know the different disabilities and their related needs is the first step to improve the consciousness and to overcome wrong ideas or prejudices.

Managing communication to all users more effectively—Satisfying ‘special’ needs by adapting museum relational, communication and welcoming competences, namely by qualifying the operators in relation to this goal, makes the structure overall more flexible and capable of managing the to-all-users-communication, thus making the facility a really inclusive and integrated one.

Qualifying public communication—The perception emerging from a visit experience contributes to creating, in the mind of the visitor, an overall idea of the city and its territory as well. Such perception has a lot to do with the immaterial elements of communication and interaction with the people you meet: this is often what determines the welcoming level of a place or a structure, ultimately leaving a good or a bad memory. Interacting correctly with people with disabilities is a key goal to be attained in order to obtain an effective and correct public communication competence. The training path has been strengthened in many ways in relation to the training activities and territorial extension finding an always growing consensus. Since the first basic course in January 2012, the following implementations have been carried out: 23 basic course editions, 16 workshops, 5 Italian Sign Language basic literacy courses applied to museum contexts and 3 social stories production laboratories. On the whole 86 museums on the national territory and over 600 museum operators took part in such educational initiative and proposals.

The training model involves a structure articulated on different formative paths:

four basic courses (among which two intensive ones addressed to museum operators coming from all over Italy);

two workshops on didactics design and intellectual disabilities;

a second level laboratory path aiming at producing social stories addressed to visitors with special needs.

The project design is flexible and open to receiving inputs and proposals coming from Museums themselves in order for the Turin experience to be built up, exported and replicated in other situations as well.

Translated by Simona Candeli, Unibo, Primary Education Sciences.