1. Introduction

Mental images, such as dreams, are emerging symbols from the unconscious that can be investigated and understood to modify and enhance the approach to the real world, but also with oneself. To imagine is not always a simple process to put into practice: for some the production may be excessive or disorderly, for other deficient or problematic and moreover the mind may not be able to distinguish reality from fantasy. Even in dubious terms, one can ask whether it makes sense to talk about “re-education to the imagination”, operated with the aid of vision.

According to Bianca Mariano [

1], the therapist’s task might also be to guide the visualization into pathological or discomfort situations, for explore the unconscious symbols, and to stimulate the patient to recall—for example through metaphorical images—seemingly removed events, for relive them and understand them. The clinical goal would be to urge the patient to create projections of their lives, in the various stages (for example, in a possible future), by depicting solutions and positive changes.

The benefits of visualization so understood would seem to be many: to promote learning and creative project in neurological rehabilitation, or as a result of injuries and trauma; improve performance in the sports field; desensitize anxiety or overcome phobias; contemplate other perspectives, prepare for change and produce new connections; dialogue with inner world; listen to own needs, desires, and conflicts.

In other respects, fantasy is by now considered to be a true therapeutic tool in the clinical field [

2] and it is also singled out in many contexts, without excluding religious ones. The first findings are already in antiquity (in Egyptian and Greek civilizations): it was thought that the images were able to release energy into the brain to stimulate the heart and other parts of the body and that a very vivid image of a disease could cause its symptoms. Roger Frétigny and André Virel [

3] remember that, in the sacred places of ancient Greece, the healer ministers placed their patients in a state of reduced vigilance, in silence and in complete darkness, to favor a condition of introversion and therefore the emergence of dreams or visions. This technique was, by itself, the cure. It wasn’t an imaginary world to be interpreted, but an experience to live, an authentically psychotherapeutic experience.

As Claudio Widmann reports [

4,

5], some sources describe exactly how this particular therapeutic treatment was performed: the patient placed in a lying position, the lights were obscured, and the “

neocori” invoked silence and rest (

Figure 1). Darkness, silence and sleep were essential conditions, and all this confirms that imaginative experiences took place in a state of introversion. In the hypnosary rooms of sacred temples to Asclepius God, the faithful-patients were induced to a state of sleep (hypnos). Modern hypnotists claim that it was “artificial sleep”, in other words, hypnosis.

There is no exact knowledge of the methods used to induce sleep, but it is well known that ritual formulas were recited, rhythmic instruments were played and incense, laurel and other herbs were used. In sleep, the faithful-patient had a dreams. It was not always nocturnal dreams, but it was certainly an image that appeared in a changed state of awareness. Those who received a grace from Asclepius, to show their gratitude, made votive gifts (terracotta or stone reproductions of parts of the diseased body which supposedly had been healed), duly inscribed and hung on the temple walls (

Figure 2).

In other respects, the same Sigmund Freud [

6] didn’t always use hypnosis to acquire unconscious material: sometimes he caused visual phenomena by pressure on the forehead, and then he asked the patients to describe everything that they had imagined.

Several recent studies [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] suggest that imagination can relax, promote healing processes, or increase intelligence, by creating new connections between neurons.

Visualization is also a useful tool to relieve stress. Some guided fantasies are even able to influence, for example, heartbeat, blood pressure, breathing, oxygen consumption, or carbon dioxide elimination.

In the medical field, in the application of the concept of vision and imagination, it is evident that no generalizations can be made for two reasons: the first is that it is necessary to differentiate the various types of upsets and psychological upsets; the second is that several authors have proposed equally differentiated therapies over time: Carl Jung’s “Active Imagination” [

15], Leopoldo Rigo’s “Imaginative Technique of Analysis and Restructuring of Unconscious” [

16], Robert Desoille’s “

Rêve éveillé dirigé (RED)” [

17]; Andrè Virel’s ”Oniroterapia” [

18]; Roberto Assagioli’s “Psychosynthesis” [

19], Joseph Wolpe’s “Systematic Desensitization” [

20] and Luigi Peresson’s ” Imaginative Analysis” [

21].

Carl Gustav Jung was one of the first researcher of the active imagination, succeeding in capturing the therapeutic potential of the imagination. Simplifying, his method can be described as observation of the flow of fantasies that emerge spontaneously, without guiding or criticizing them, but by helping the patient to express them creatively.

Gestalt images can also be a therapeutic aid. In some applications, Gestalt can work on spontaneous and guided dreams: every part of them represents a person’s appearance and can provide meaningful responses to unresolved aspects of life or inner reality.

But it’s only thanks to French engineer Robert Desoille and his technique of “Guided Dream” that the use of mental images has become a real therapeutic tool. Its method is used in a clinical setting because it permits, with relative simplicity, access to that inexhaustible reserve of resources that subjects have acquired during their lifetime. Some researchers agree that the mental state triggered by the “guided dream” is a state that is halfway between wakefulness and sleep, similar to an hypnotic state.

Roberto Assagioli’s “Psychosynthesis”, on the other hand, considers the human being with a deep centre of awareness and will (the Self), whose task is to direct personal, relational and environmental aspects in an harmonic synthesis. Suffering comes from the fragmentation of the personality and the loss of contact with the centre. By means of imagination, it is possible to find balance, by implementing a sort of transposition into what is elaborated by our mind; in practice if we focus on a positive mental image, this latter can pervade the mind until it becomes an action; in the same way it is possible to effectively replace negative thoughts with other more constructive.

The “Systematic desensitization” is another imaginative technique introduced by Wolpe in the 1950s and used in cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The patient is encouraged to build a hierarchy of situations that cause anxiety, which he will have to reconsider when he will be more relaxed; then, in order to weaken the link between anxiety and its causes, the patient must visualize a pleasant image. In this way, the relaxation increases and the invalidate emotion decreases.

In the field of Psychodynamics, Psychopathology and Psychotherapy, even Marco Casonato [

22] experiments imagination and metaphor in therapeutic change.

2. Imagination and Psychoanalysis in Film Projection

If, as Oscar Wilde argues, “the true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible”, in interdisciplinary comparison between psychoanalysis and representation, it may be useful and relevant to recall some particular films that recourse to visual projects (such as for example citations of famous paintings), to evoke fantastical and surreal sceneries, which represent moods, even pathologic. The interpretation of the subconscious is used in film representation through images and imagination, which are rendered more fluid by visual narrative.

One of the films that best represents this concept of “citation” is Io ti salverò (Spellbound), a 1945 film produced by David O. Selznick and directed by Alfred Hitchcock, with Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck. The film is taken from the novel “The House of Dr. Edwards,” by Francys Bedding.

Hitchcock entrusted the scenographic creation of the most important film scene to Salvador Dalì, the greatest expert in the figurative representation of oneiric material [

23].

The most important moment of Hitchcock’s film was exactly a dream: what Gregory Peck describes to psychiatrists who are helping him recover lost memory. Dalì designed a sequence that became cult: eyes that appear of the walls and curtains, men without face, and objects with twisted edges (

Figure 3).

What gives more charm to the whole scene is the psychological aspect: all the elements of the dream have a definite meaning, which will be unveiled at the stage of psychoanalysis and will constitute the final turning point of the film.

It’s no coincidence that we can talk about “citations” of other paintings: throughout the scene of the dream there are continuous references to the artist’s painting works; on the other hand Dali, the only surrealist painter who personally met Sigmund Freud, is also an artist who has been able to make good use of dreams and stress through pictorial representations.

In the scenography there isn’t reproduction of a specific work, but a synthesis of the surrealistic styles of the Spanish artist (

Figure 4). The director doesn’t just want to “narrate dreams”, but also wants to describe hallucinations, to transmit the sensations of a nightmare. The protagonist of the film searches in her own psyche the reasons for his discomfort, his phobias and his guilt feelings.

Another film that narrates and describes the atmospheres of an heartfelt dream is Portrait of Jennie (USA 1949) of William Dieterle, which is inspired by Robert Nathan’s novel.

We are in New York, but it is a “different city”: not chaotic, but crystallized by a frosty winter, which imparts a sense of “timelessness”. In fact, all the film narration moves toward a “suspended time”, somewhere fantastic or phantasmagoric, as if the diachronic had jammed in the picture.

Eben Adams (Joseph Cotten), a painter who fights against the indifference of the world, while walking in Central Park, meets a child, Jennie (Jennifer Jones), who expresses the desire to “burn the stages of time and become her peer” so that love between them is possible. Eben is fascinated by Jennie and he decides to make her a portrait, getting a great result, maybe one of his best work.

At each meeting, Jennie “appears” grown with incredible speed, from child to girl, from girl to woman, as if her desire had been heard from sunset to dawn.

Jennie is a ghost introduced into an increasingly dreary present; nobody sees her, apart from Eben. The ambiguity of her body becomes the leitmotiv of the film, which emphasizes the theme of return; a mystical return which is reinforced by the metaphor of “love that breaks the boundaries of time”. All this seems a bit resizing and trivial, but there is more; Jennie, as a ghost, becomes “cinematographic simulacrum”. Bodies dancing on the white screen appear static in the frame, so they already look like non-bodies.

The “return” is an essential feature of cinema; when we look at a movie, we do nothing else than seeing actions already done in other places and in other times. If you happen to see a dated movie, we are likely to see deceased people, who are trapped in an obsessive and infinitely reproducible tunnel. The actors seem to be pigeonholed and tight in a frame: eternal and locked.

Luis Buñuel, director and screenwriter, who was very fascinated by this film, defined it as a “fragile ghost story” that lives on the screen for a kind of magical balance between dreamy atmospheres (New York under the snow) and a illusory and disturbing timelessness.

The original version included sequences turned in different colours, from black and white to green (green is the color of the putrefaction of the bodies and therefore of the death) (

Figure 5) and a finale in technicolor [

24]. In addition to overcoming the line separating the kingdom of the living with that of the dead, the film gains another passage: the final explosion of the Technicolor that framing the portrait of Jennie, painted by Eben, in a museum.

Portrait of Jennie was certainly a source of inspiration for another great film, Vertigo (The Woman Who Lived Twice), drawn from a book written for Alfred Hitchcock (D’entre les morts by Boileau-Narcejac). The analogies with Dieterle’s film are many.

3. “Vertigo” as a Psychic Experience and Mental Image

The protagonist of Vertigo is Scottie (James Stuart) a policeman with acrophobia; precisely due to of the fear of emptiness and height, he cannot save a colleague who dies during a pursuit on the roofs. He is commissioned by a long time friend to chase his wife Madeleine (Kim Novak) in the grip of a strange psychic turmoil. Scottie ends up falling in love with her, but she cannot impede her death: the woman in fact climbs up to a bell tower and throws herself in the void. Stewart’s sense of guilt for a pathology that he has developed during an unpleasant accident at work: that unattainable bell tower is the worst nightmare you can imagine. The vertigo, invalidating disorder, will force him to retire and make him the perfect victim of the murderous plan. In a strong succession of subjective shots, the viewer shares with Scottie the experience of “vertigo”, that is technically achieved through the synchronicity of the behind zoom and the forward movement.

The film space is set with a continuous “high” and “low” alternation: the flat surfaces, on which the protagonist moves himself safely, opposes themselves the verticality of the monastery bell tower or the roofs, where Scottie is in obvious difficulty.

In the case of protagonist’s pathology (vertigo), the process of gestaltic psychology occurs through visual narrative, which associates the spiral of vertigo with the gestaltic spiral of the form psychology: the so-called Mach effect [

25].

Even the use of colour is interesting: it is red when the Scottie restaurant sees Madeleine for the first time, while green and cold hues allude to the death blast: there are dresses that are worn to rebuild the past while gray replaces the dominant shade that is green. The sequence of evergreen trees acts as a catalyst to the prevailing color in the dress worn by Madeleine the first time that she appears on the screen.

In the second part of the film, images with the mirror are particularly important (almost a Droste effect). The mirror represents the element through which the protagonist sees himself, because he looks at the woman, that at the same time observe herself on the surface reflective (

Figure 6).

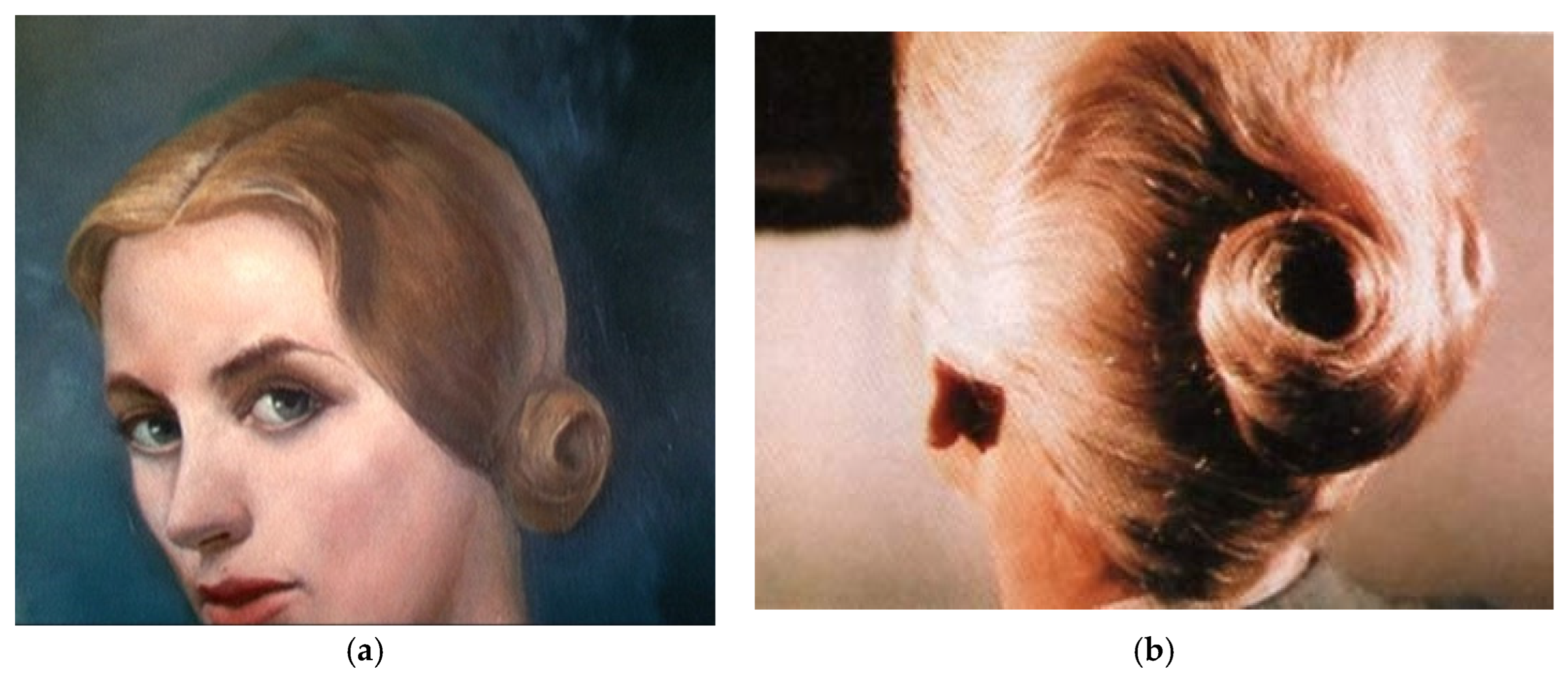

The protagonist, Kim Novak, plays a mysterious and enigmatic dual role. She appears “doubled in four”: she is the fake Madeleine Elster (who is sitting in front of the picture of Carlotta Valdès, the suicide victim forefather, almost replicating her in some details of clothing) (

Figure 7), then Judy Barton, who confesses the fairy tale of the first part. She dies two times falling from the bell tower, the first simulating, the second really.

In

Vertigo, the concept of the psychiatrist and French philosopher Jacques Lacan [

26] on the formation of the ego (thanks to the image in the mirror of the other) is placed by the director at the center of an illusory mechanism. In fact, when Judy became completely identical to Madeleine, Scottie recognizes himself again thanks to the image of the other woman, or rather to the illusion of the other woman’s image.

In this game of illusions, the identity of the subjects is deleted; the characters of the history are manipulated, so their mental image appears to be changed. For example, the protagonist of the film is a highly ambiguous, conscious victim of the deception that she interprets. The whole history is centred on the concept of illusion, optic too. On top of everything and everyone the concept of “double” dominates.

The bell tower from which Madeleine launch herself is the image of the convent of San Juan Battista, that is inserted whit special effects of the time. In the film, the sense of vertigo that assails the protagonist is expressed through an exceptional expedient of direction [

27].

The urban location is also of great semantic depth: Hitchcock’s San Francisco is the mirror of Dieterle’s New York, and both climaxes are reached in towers in suburbs (in Vertigo from a church bell tower, in Portrait of Jennie from a lighthouse by the sea); the spiral staircases filmed in plongèe, appear in both films (although with different results and meanings).

Hitchcock used fog filters to film Madeleine/Judy, getting a green effect; in the spectacular sequence of the stormy sea of Dieterle’s film there is a turn from black and white to green; Jennie is green as Madeleine/Judy is in the hotel, when she is illuminated by the green neon light [

28].

If a feature of Dieterle’s film is the “spiritualist fantasy”, that is an extra-daily bonded to the realm of shadows, in Vertigo the fantasy is false, because it hides a well-organized criminal intrigue.

In Francois Truffaut’s book-interview [

29], the British director explains the motive of the film: “I was very interested by James Stewart’s efforts to recreate a woman, starting with the image of a woman who no longer exists.” The actor reinvents the beloved woman, who is dead (this is her thoughts) because of her

defaillance. On the contrary,

Portrait of Jennie is based on the structure of the fantastic subject. There isn’t rational explanation, but a surreal meeting that shocks the painter’s everyday life, irremediably altering his existence.

4. The “Charm of Fascination” through the Images

“The absorption of conscience through the show can be called fascination: the impossibility to grasp at the images, the imperceptible movement to the screen, the annulment of the ego in the wonders of a universe in which even death is at the extreme of desire”. The main project of the filmmaker is precisely to bring this attention to the screen [

30].

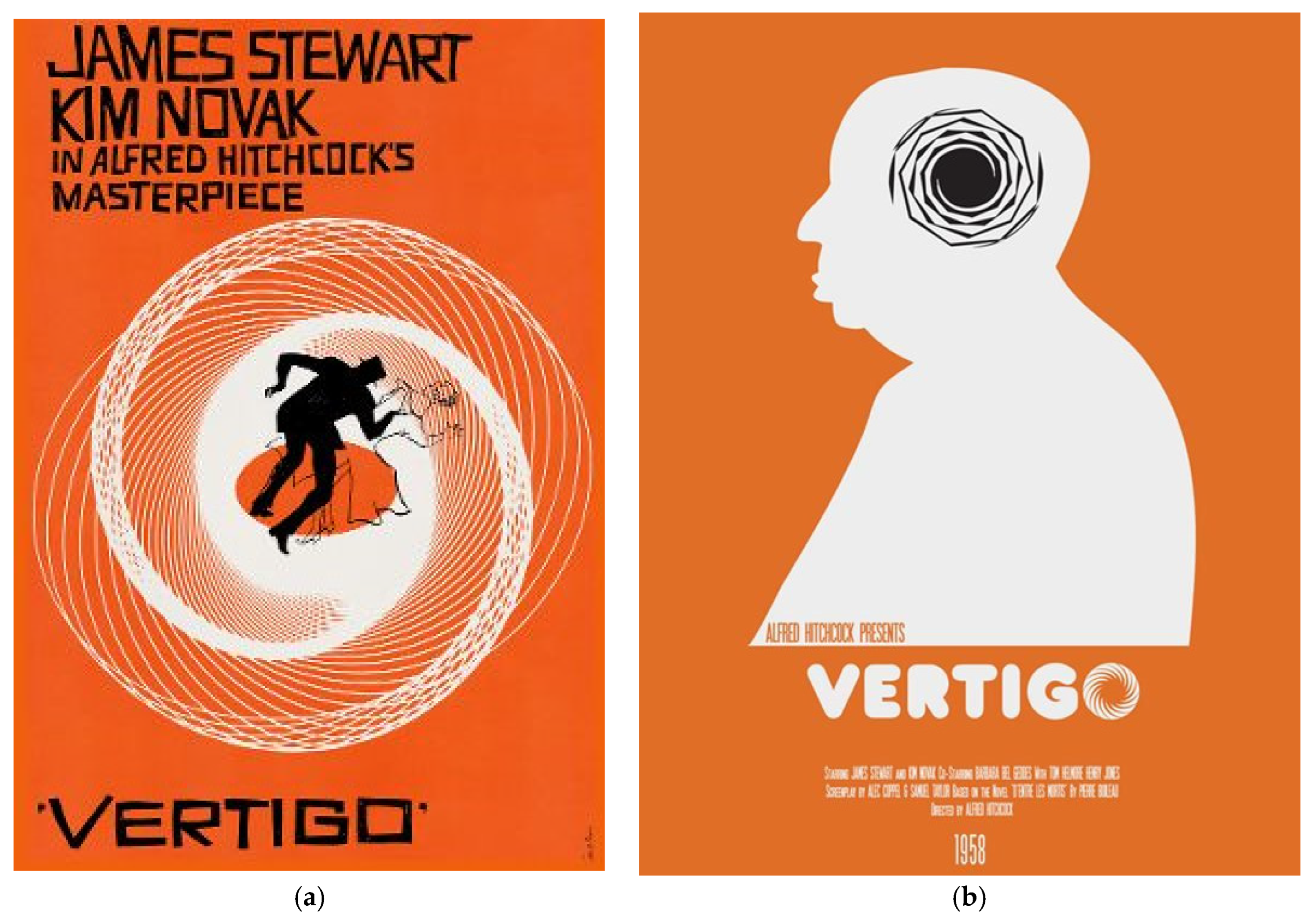

As some critics consider, the first and fundamental field of action of

Vertigo is the sensory one. For explain this consideration, the headlines made by Saul Bass come to our aid. Hitchcock imagined them as a conceptual condensation of the entire film. Very close details of a black-and-white woman’s face: mouth, nose, and an eye in which, in series, colourful spirals rotate. Regardless of the many iconographic and metaphorical shapes that the spiral figure assumes during the film [

31], those polychrome vortices—probably inspired by Man Ray’s drawings, for poetry

La logique assassine and Rotorelief, contained in

Anemic cinema by Marcel Duchamp—with their unstoppable hypnotic movement, are a network that extends to capture the spectator (

Figure 8).

That eye, belonging to an unknown female entity, is the eye of the screen that with its lively spirals kidnaps those who are watching. It is difficult to imagine a more comprehensive graphic and iconographic summary of the concept of fascination. It is a concept that doesn’t concern the mere emotional involvement or empathic participation of those who watch a show, but it refers to a totalizing experience, a kind of temporary possession by the entire audiovisual system.

And, still in reference to the encounter between psychoanalysis and representation in cinematic performance, what are the elements and tools that so much enhance the narration for moving images, especially in the illusory dimension? Answers can be multiple: images, words, music, noises; but not only. Everyone can compete (through relationships of various kinds) with the definition of audiovisual as a complex language, on the "plane of expression" and, to some extent, also on the “content plan” [

32].

The “illusory works”, therefore, can represent a real world, maked of experiences that can be lived from within and personally.

As Bela Balazs [

33] and Jean Mitry [

34] have already seen, “cinematographic art creates in the spectator the illusion of being at the centre of the action in the places that the film represents”, namely it offers the ability to identify with characters in history and to get excited with them. Secondly, if there is affinity and contiguity between experience of life and optical and sensory experience (many talk of an “experiential continuum” that is difficult to segment), it isn’t just because the films resemble life, but also because, in a way, life resembles films.

Psychology and psychoanalysis persist from some time that, in order to truly experience life, we must “tell ourselves”, our personal history: to put events in line, not only on the temporal level, but also on the logical and causal one; reconstruct the intentions of the subjects in the field and their motivations.

5. The “Polysemic Labyrinth” and the Interpretative Vertigo

As is known, in the course of his films, Hitchcock in a central position often it poses long sequences with no dialogues, in which to tell are only the images, the duration, the movement.

In the case of the film The woman who lived twice (for example) the mute 10 min in which Scottie follows the Madeleine’s car reveal by themself the essence of the work: in the gradual changes of expression he matures his sick passion, in the inextricable maze of roads and paths.

Parallel to the desire to bring the film medium to the maximum expressive clarity, there is the awareness that the seventh art borns hybrid and that the simultaneous presence of various codes (visual and polysensory, even before artistic) is inherent in its nature.

So the director draws upon full hands from the nearby universes of painting, architecture, graphics, music, dance to compose his films, intersecting and superimposing layers of meaning.

Consequently, Vertigo can only be a “polysemic labyrinth” in which the use of multiple arrays produces a surplus of sense and suggestion, in which the whole is always discovers (“gestalticamente”, we could say) greater than the sum of the individual parts. To achieve this, the contribution of his collaborators has been obviously very valuable.

Saul Bass’s graphic nightmares draw the trajectories of the absurd, Robert Burks’s photography enhances the changes of light and the interventions of colour as a reflection of the inner disorders of the characters; the sublime hypnosis of Bernard Herrmann’s Symphony evolves, recursively, into a sort of paradoxical “Droste effect” musical. Then, the one created by Hitchcock becomes ultimately an “interpretative dizziness” that, through the stories of many interpreters, transforms the hermeneutic dimension into pure spectacle.

At the concluding stage it would be appropriate and congruent to provide a concise review of visual and graphic images of the illustrated features: for a purely exemplifying example, reference is made to Marco Teti’s work “La vertigine in una spirale. La centralità della figura spiraliforme in La donna che visse due volte”.

The protagonist of

Vertigo might be an

alter ego of Hitchcock, because he (likewise the director) thinks to create through images—manipulating Judy—an “invented” subject (

Figure 9). And this can be confirmed as a distinctive feature of the artistic personality of the great director, and of all his film production.