Multifractality Between PM2.5, Air Quality Index and Ozone for Sites of California

Abstract

1. Introduction

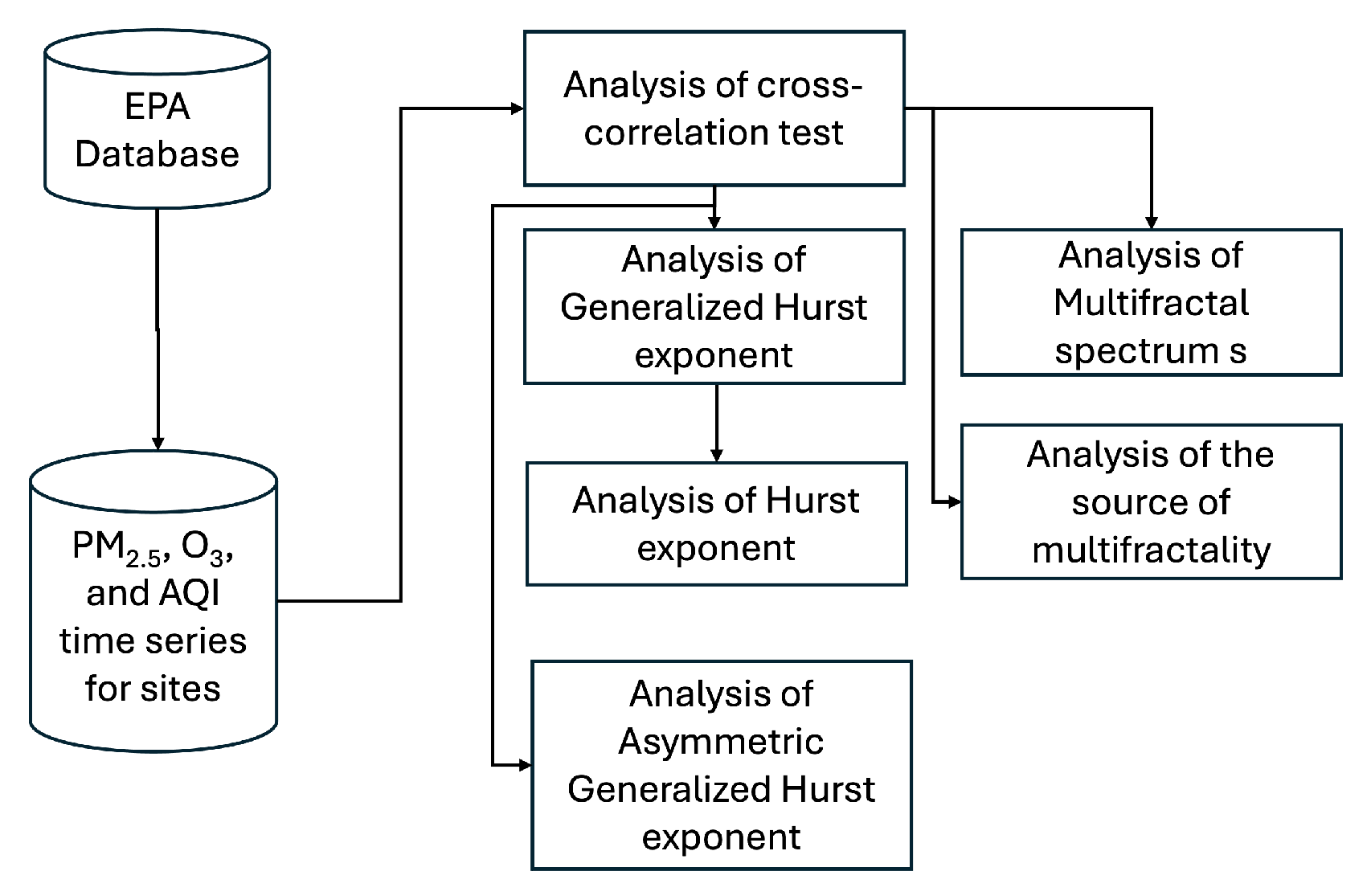

2. Materials and Methods

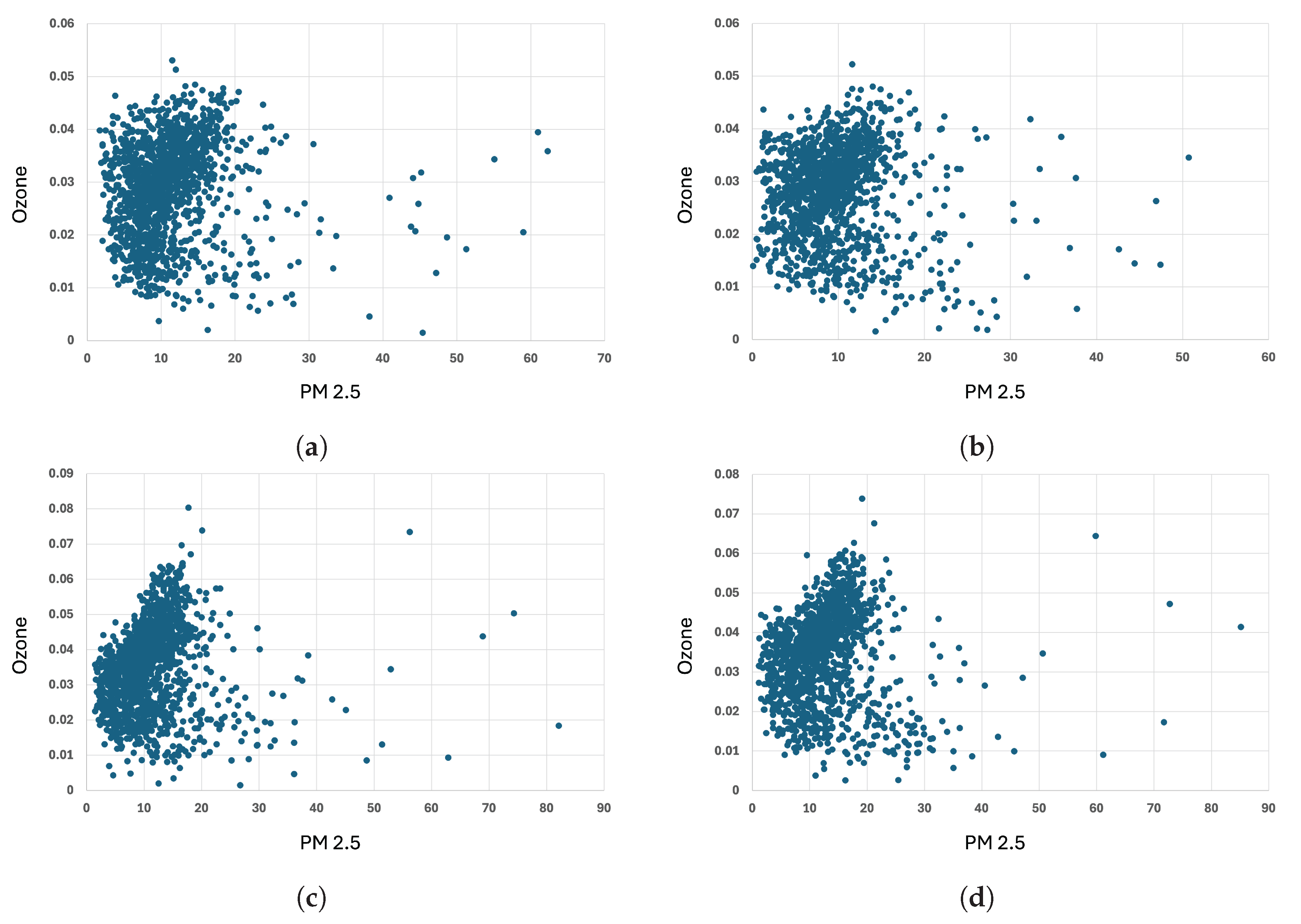

2.1. Data

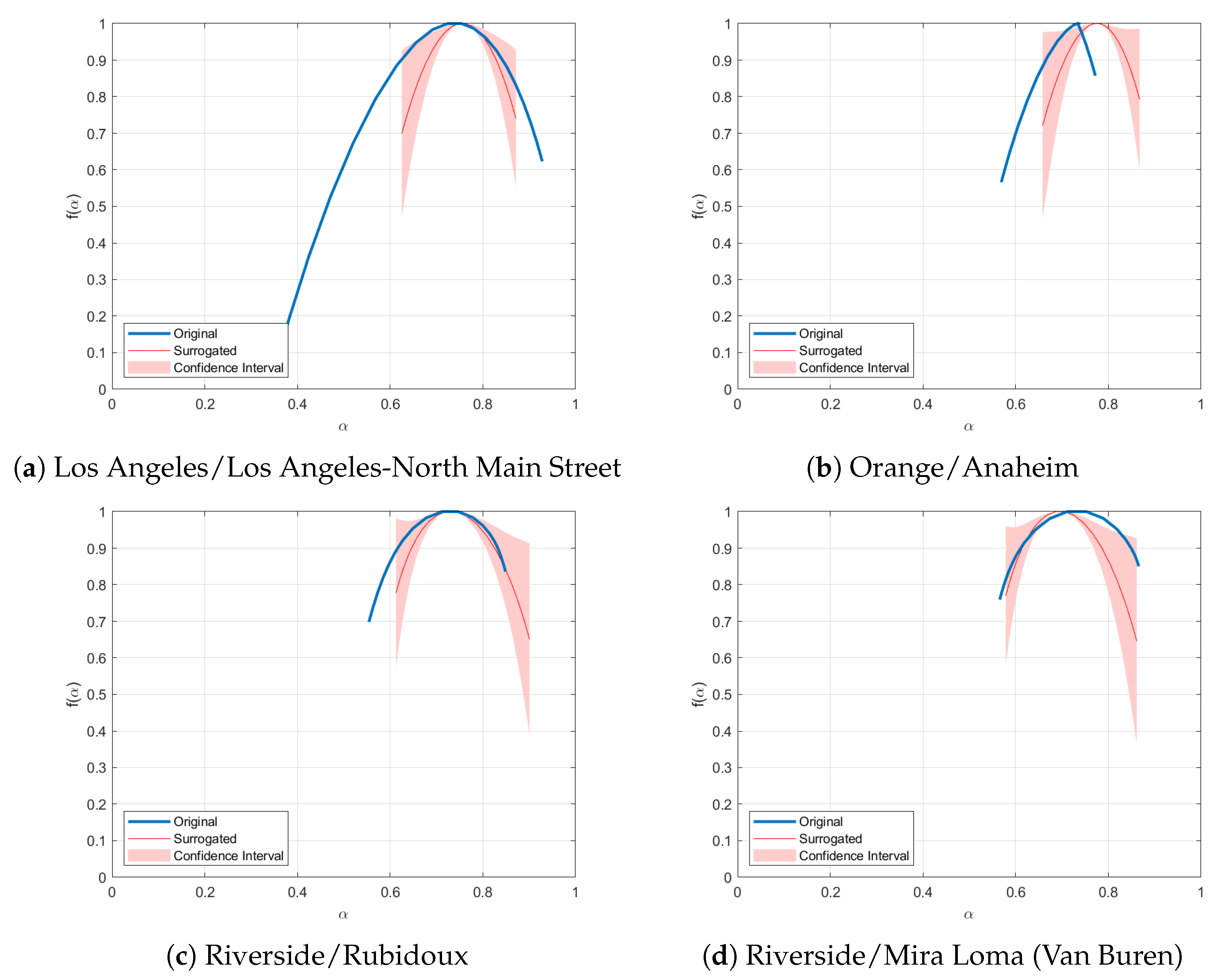

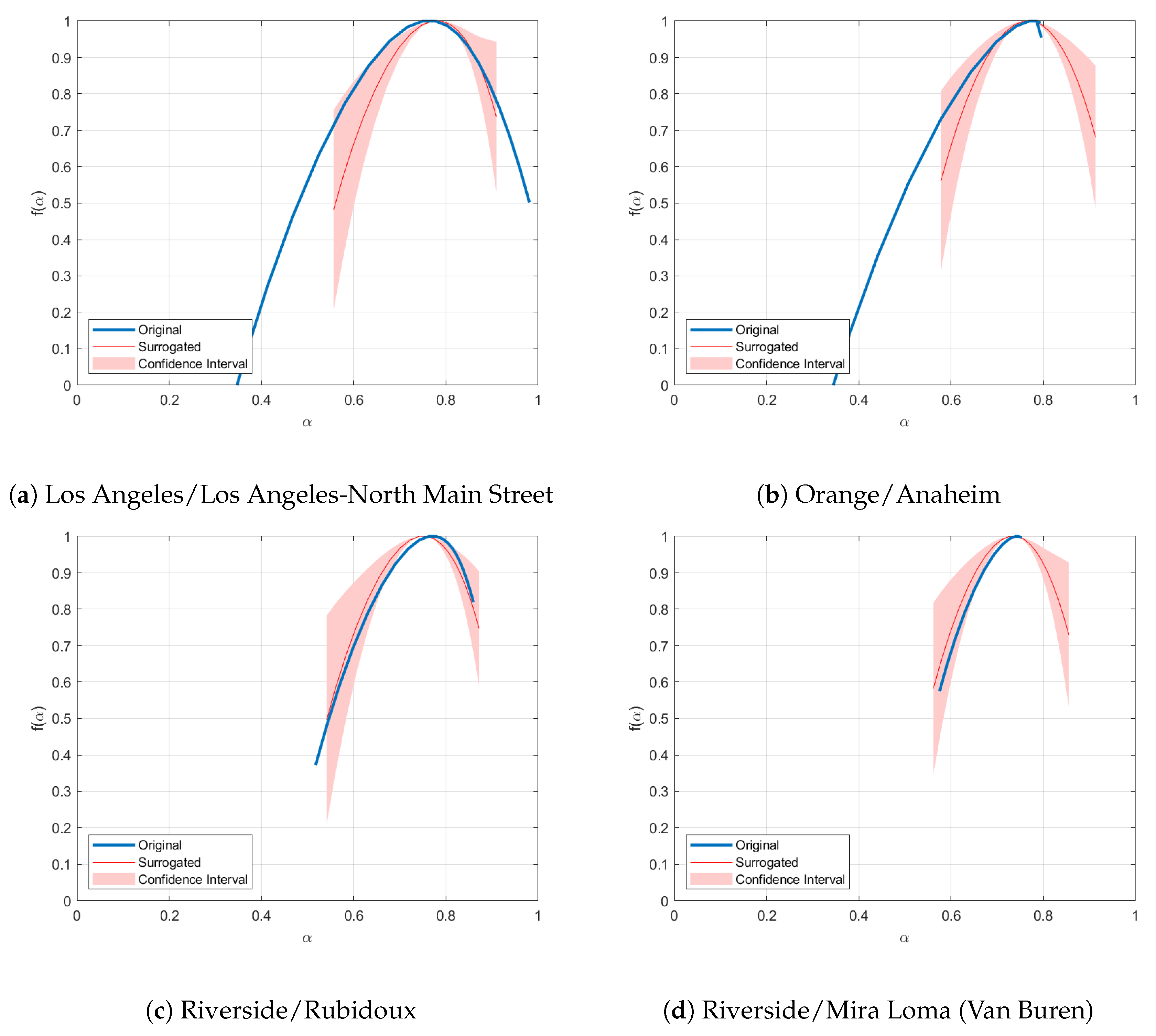

- Los Angeles—North Main Street (NMS)

- Orange—Anaheim (A)

- Riverside—Rubidoux (R)

- Riverside—Mira Loma, Van Buren (ML)

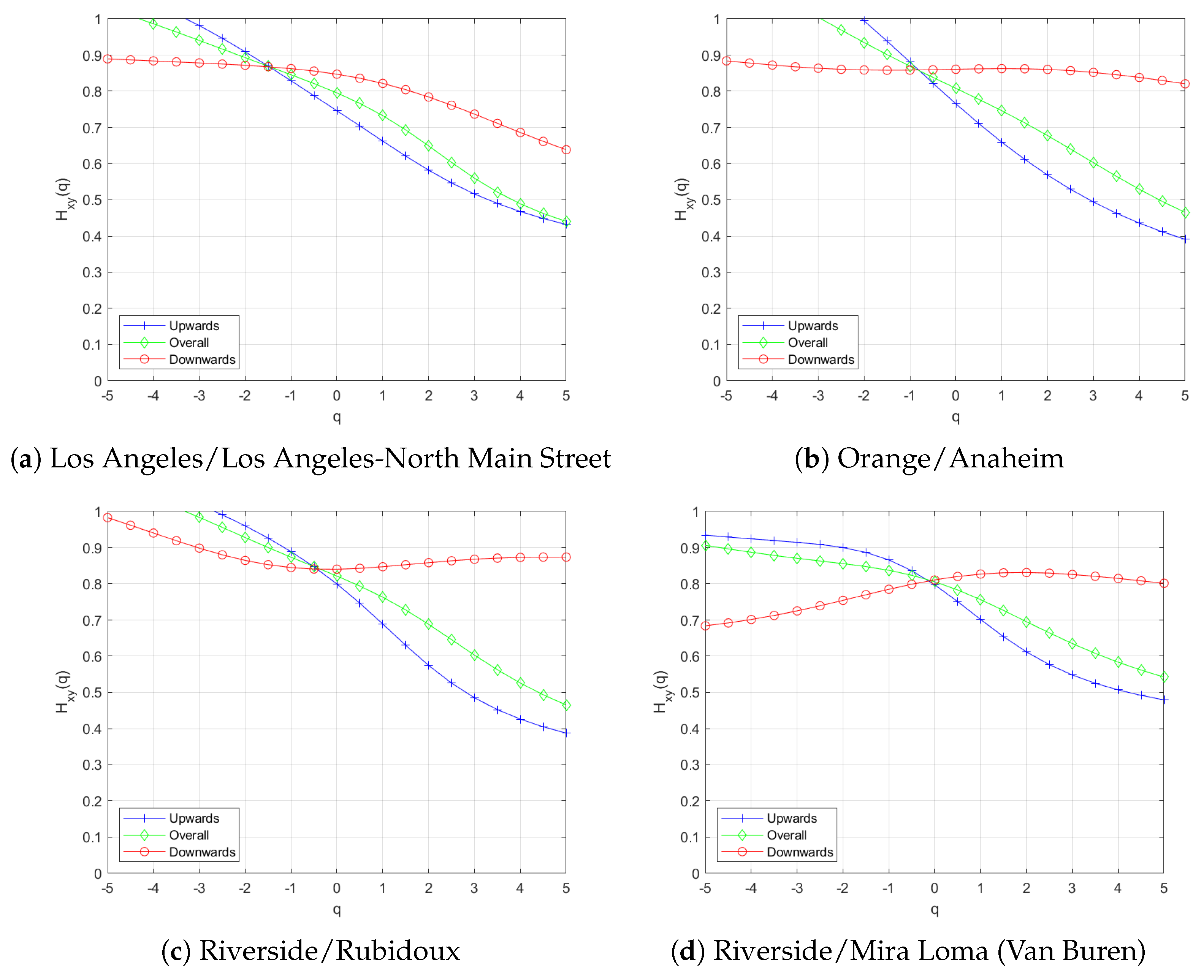

2.2. Methodology

- If , the series exhibits persistence, meaning a positive (negative) change in one measure is statistically more likely to be followed by a positive (negative) change in the other.

- If , the series is antipersistent, indicating that a positive (negative) change in one measure is more likely to be followed by a negative (positive) change in the other.

- If , the series displays short-range or no auto-correlations, consistent with the behavior of a random walk.

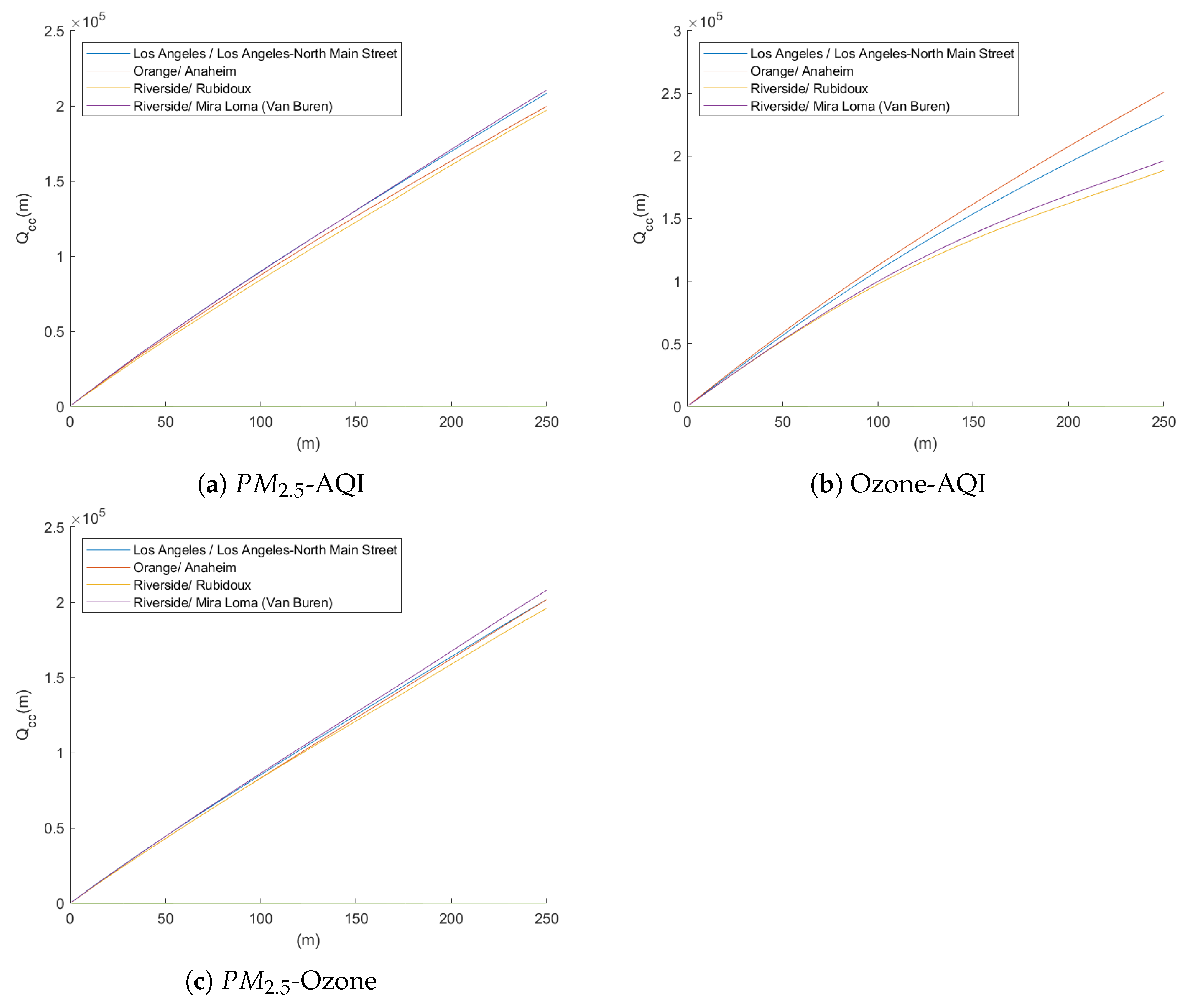

Cross-Correlation Test

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Calculating the AQI

- 1.

- Identify the highest concentration among all of the monitors within each reporting area and truncate as follows:Ozone (ppm)—truncate to 3 decimal places.(µg/m3)—truncate to 1 decimal place.(µg/m3)—truncate to integer.CO (ppm)—truncate to 1 decimal place.(ppb)—truncate to integer.(ppb)—truncate to integer.

- 2.

- Using Figure A1, find the two breakpoints that contain the concentration.

- 3.

- Equation (1), calculate the index.

- 4.

- Round the index to the nearest integer.

References

- Edo, G.I.; Itoje-akpokiniovo, L.O.; Obasohan, P.; Ikpekoro, V.O.; Samuel, P.O.; Jikah, A.N.; Nosu, L.C.; Ekokotu, H.A.; Ugbune, U.; Oghroro, E.E.A.; et al. Impact of environmental pollution from human activities on water, air quality and climate change. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fang, C.; Wang, S.; Sun, S. The effect of economic growth, urbanization, and industrialization on fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11452–11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszar, P.; Perez, A.P.P.; Bartík, L.; Karlický, J.; Villalba-Pradas, A. Impact of urbanization on fine particulate matter concentrations over central Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Nathani, M.; Mishra, R. Comprehensive evaluation of deep ltsf models for forecasting of air quality index. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 4410–4419. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Jing, X.; Ling, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jing, N.; Yuan, R.; Liu, Y. Optimized air quality management based on air quality index prediction and air pollutants identification in representative cities in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: A review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Pechuho, T.; Safdar, M.; Islam, R.; Durrani, F.; Rashid, S.; Khan, K.N.; Chohan, A.A. Air pollution and climate change: A dual threat to ecosystems and human health. J. Med. Health Sci. Rev. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. What Are the WHO Air Quality Guidelines? Improving Health by Reducing Air Pollution. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/what-are-the-who-air-quality-guidelines#:~:text=What%20do%20the%20guidelines%20recommend,evaluation%20of%20current%20scientific%20evidence (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Air Quality Data. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Hou, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, L.; Gao, T. The effect of visibility on green space recovery, perception and preference. Trees For. People 2024, 16, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, J.; Broberg, M.; Strandberg, B.; Thorsson, P.; Pleijel, H. Influence of urban vegetation on air pollution and noise exposure—A case study in Gothenburg, Sweden. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599, 1728–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.S.; Vidal, D.G.; Cherif, N.; Silva, L.; Remoaldo, P.C. Green infrastructure and its influence on urban heat island, heat risk, and air pollution: A case study of Porto (Portugal). J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Cao, S.J. Spatial synergistic effect of urban green space ecosystem on air pollution and heat island effect. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriazu-Ramos, A.; Santamaría, J.M.; Monge-Barrio, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Gutierrez Gabriel, S.; Benito Frias, N.; Sánchez-Ostiz, A. Health Impacts of Urban Environmental Parameters: A Review of Air Pollution, Heat, Noise, Green Spaces and Mobility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. New urban models for more sustainable, liveable and healthier cities post COVID-19; reducing air pollution, noise and heat island effects and increasing green space and physical activity. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ni, Z.; Ni, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, L. Asymmetric multifractal detrending moving average analysis in time series of PM2. 5 concentration. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 457, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Multifractal characterization of air polluted time series in China. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 514, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, K. Fractal analysis of impact of PM2.5 on surface O3 sensitivity regime based on field observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.E. Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1951, 116, 770–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.E. A suggested statistical model of some time series which occur in nature. Nature 1957, 180, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.K.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Havlin, S.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H.E.; Goldberger, A.L. Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.K.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Goldberger, A.L.; Havlin, S.; Sciortino, F.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H.E. Long-range correlations in nucleotide sequences. Nature 1992, 356, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Ivanov, P.C.; Chen, Z.; Carpena, P.; Stanley, H.E. Effect of trends on detrended fluctuation analysis. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 011114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantelhardt, J.W.; Koscielny-Bunde, E.; Rego, H.H.; Havlin, S.; Bunde, A. Detecting long-range correlations with detrended fluctuation analysis. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2001, 295, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Rodriguez, E.; Echeverria, J.C. A DFA approach for assessing asymmetric correlations. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2009, 388, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Cao, J.; Xu, L. Asymmetric multifractal scaling behavior in the Chinese stock market: Based on asymmetric MF-DFA. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2013, 392, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossadnik, S.; Buldyrev, S.; Goldberger, A.; Havlin, S.; Mantegna, R.; Peng, C.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H. Correlation approach to identify coding regions in DNA sequences. Biophys. J. 1994, 67, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavasseri, R.G.; Nagarajan, R. A multifractal description of wind speed records. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2005, 24, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, K.; Ausloos, M. Application of the detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) method for describing cloud breaking. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1999, 274, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Fu, Z.; Deng, X.; Mao, J. A brief description to different multi-fractal behaviors of daily wind speed records over China. Phys. Lett. A 2009, 373, 4134–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, F. Multi-fractal scaling comparison of the air temperature and the surface temperature over China. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 462, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitanov, N.K.; Yankulova, E.D. Multifractal analysis of the long-range correlations in the cardiac dynamics of Drosophila melanogaster. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2006, 28, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunde, A.; Havlin, S.; Kantelhardt, J.W.; Penzel, T.; Peter, J.H.; Voigt, K. Correlated and uncorrelated regions in heart-rate fluctuations during sleep. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazy, Y.; Ivanov, P.C.; Havlin, S.; Peng, C.K.; Goldberger, A.L.; Stanley, H.E. Magnitude and sign correlations in heartbeat fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Song, W.; Wang, J. Detrended fluctuation analysis of forest fires and related weather parameters. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2008, 387, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X.P.; Tao, W.Q. A multi-level fractal model for the effective thermal conductivity of silica aerogel. J.-Non-Cryst. Solids 2015, 430, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumara, P.; Wu, L.; Lu, T.; Tan, C.L.; Blumenstein, M.; Anami, B.S. Fractals based multi-oriented text detection system for recognition in mobile video images. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 68, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wu, X.; Fu, B.; Chen, W.; Feng, H. Fast face recognition based on fractal theory. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 321, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalajmasoumi, M.; Sadeghi, B.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Sadeghi, M. Geochemical anomaly recognition of rare earth elements using multi-fractal modeling correlated with geological features, Central Iran. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 181, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masugi, M. Multi-fractal analysis of IP-network traffic based on a hierarchical clustering approach. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2007, 12, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Wang, S.P. Improved multi-fractal network traffic model and its performance analysis. J. China Univ. Posts Telecommun. 2011, 18, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S. Multi-fractal analysis for pavement roughness evaluation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 96, 2684–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.K.; Pastén, D.; Khan, P.K. Multifractal analysis of 2001 Mw7. 7 Bhuj earthquake sequence in Gujarat, western India. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2017, 488, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, M.; Severino, G.; De Bartolo, S.; Fallico, C.; Santini, A. Scaling analysis of water retention curves: A multi-fractal approach. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 19, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lv, X.; Yin, J.; Tian, L.; Liang, J. Multifractality and market efficiency of carbon emission trading market: Analysis using the multifractal detrended fluctuation technique. Appl. Energy 2019, 251, 113333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ni, Z.; Ni, L. Multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis between PM2. 5 and meteorological factors. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2015, 438, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Moreno, P.; Moreno-Torres, L.; Lovallo, M.; Telesca, L.; Ramírez-Rojas, A. Spectral, multifractal and informational analysis of PM10 time series measured in Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 565, 125545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantelhardt, J.W.; Zschiegner, S.A.; Koscielny-Bunde, E.; Havlin, S.; Bunde, A.; Stanley, H.E. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of nonstationary time series. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2002, 316, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podobnik, B.; Grosse, I.; Horvatić, D.; Ilic, S.; Ivanov, P.C.; Stanley, H.E. Quantifying cross-correlations using local and global detrending approaches. Eur. Phys. J. B 2009, 71, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perišić, M.; Vuković, G.; Stanišić, S.M. Multifractal Characteristics of Criteria Air Pollutant Time Series in Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the Sinteza 2020-International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Data Related Research, Stanford, CA, USA, 1–2 August 2020; Singidunum University: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, P. Multifractal behavior of an air pollutant time series and the relevance to the predictability. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, B.; Shi, K. A study of cross-correlations between PM2.5 and O3 based on Copula and Multifractal methods. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 589, 126651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, N.S.; Morawska, L. A review of dispersion modelling and its application to the dispersion of particles: An overview of different dispersion models available. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 5902–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Du, J.; Shi, K. The multifractal evaluation of PM2.5-O3 coordinated control capability in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masseran, N. Multifractal characteristics on temporal maximum of air pollution series. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Ou, C.Q. Nonlinear and lagged meteorological effects on daily levels of ambient PM2.5 and O3: Evidence from 284 Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AQI () | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMS | A | R | ML | NMS | A | R | ML | |

| Average | 11.30 | 9.62 | 11.46 | 13.01 | 51.31 | 45.67 | 51.19 | 55.09 |

| St. Dev | 6.28 | 5.57 | 6.86 | 7.16 | 16.56 | 17.51 | 18.02 | 17.95 |

| Min | 1.70 | 0.10 | 1.50 | 1.10 | 9.00 | 1.00 | 8.00 | 6.00 |

| Max | 62.30 | 50.70 | 82.10 | 85.10 | 156.00 | 138.00 | 170.00 | 172.00 |

| Ozone | AQI (Ozone) | |||||||

| NMS | A | R | ML | NMS | A | R | ML | |

| Average | 0.0285 | 0.0280 | 0.0352 | 0.0345 | 42.58 | 36.96 | 64.42 | 62.75 |

| St. Dev | 0.0094 | 0.0089 | 0.0125 | 0.0118 | 16.32 | 10.69 | 40.74 | 37.32 |

| Min | 0.0015 | 0.0015 | 0.0015 | 0.0025 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 |

| Max | 0.0531 | 0.0522 | 0.0803 | 0.0738 | 161.00 | 119.00 | 206.00 | 197.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kristjanpoller, W.; Minutolo, M.C. Multifractality Between PM2.5, Air Quality Index and Ozone for Sites of California. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120821

Kristjanpoller W, Minutolo MC. Multifractality Between PM2.5, Air Quality Index and Ozone for Sites of California. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):821. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120821

Chicago/Turabian StyleKristjanpoller, Werner, and Marcel C. Minutolo. 2025. "Multifractality Between PM2.5, Air Quality Index and Ozone for Sites of California" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120821

APA StyleKristjanpoller, W., & Minutolo, M. C. (2025). Multifractality Between PM2.5, Air Quality Index and Ozone for Sites of California. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120821