Adaptive Fuzzy Finite-Time Synchronization Control of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Uncertain Dynamics, Unknown Parameters and Input Nonlinearities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- (2)

- FLSs are employed to approximate uncertain dynamics, while the NGF is applied to address unknown control directions arising from input nonlinearities. Furthermore, some parameter adaptive laws are designed to achieve bounded estimation of these unknown parameters. Compared with these methods in [26,29,30,32,35], this approach enables a more streamlined controller design.

- (3)

- An adaptive fuzzy FTSC scheme is designed, which guarantees that the SE converges to a SNoZ within a FT, and all signals of the CLS remain ultimately bounded.

- (4)

- Compared with the traditional PID controller and another FT control method, the proposed control method in this work can achieve better synchronization performance in a shorter FT.

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

2.1. Preliminaries

2.2. FLS

2.3. Problem Formulation

3. Control Strategy Design and Stability Analysis

3.1. Adaptive Fuzzy FT Control Strategy Design

3.2. Stability Analysis

4. Simulation Analysis

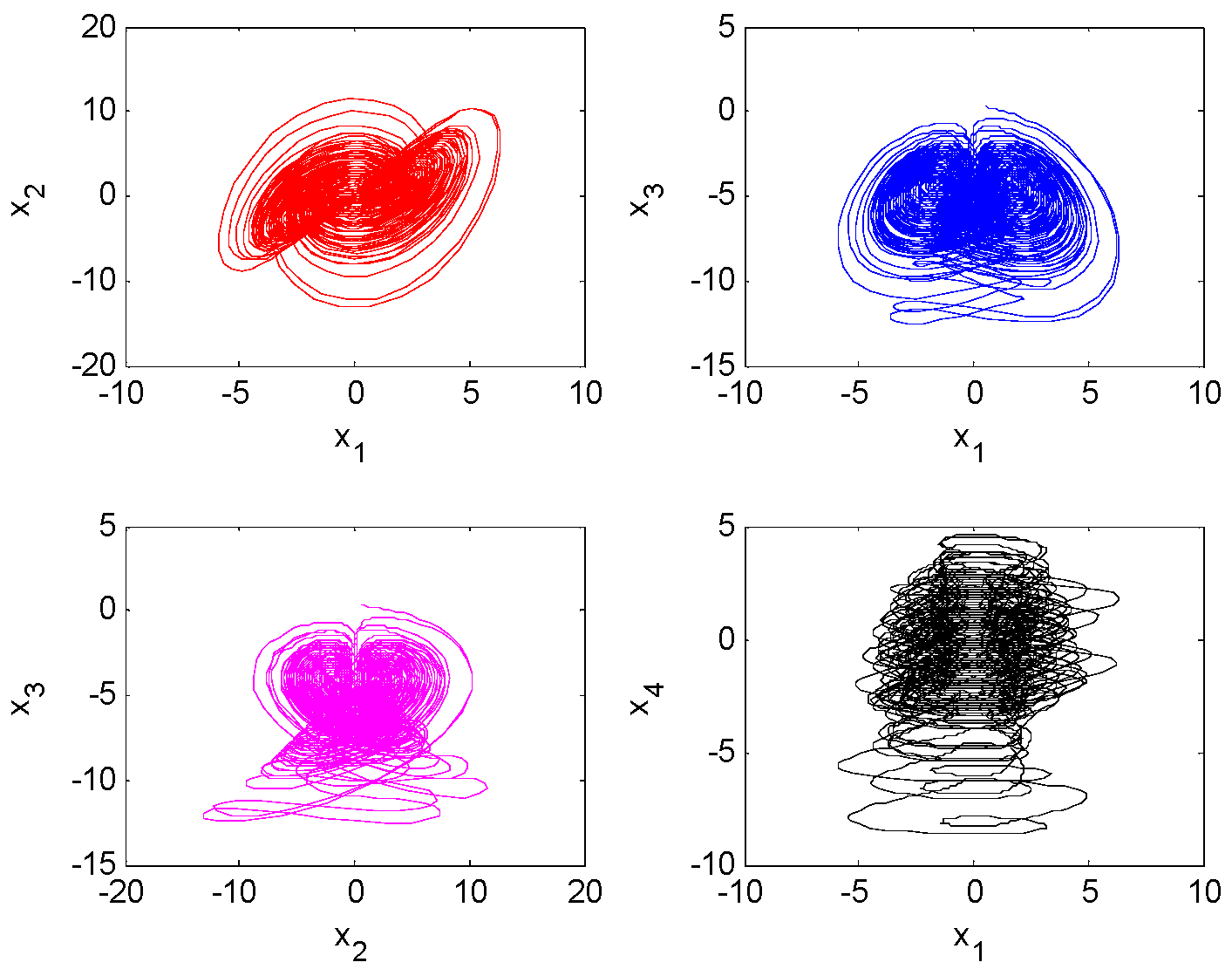

4.1. FTSC of FO Liu Hyperchaotic System

4.2. FTSC Between FO Chen System and FO Lorenz System

4.3. Comparative Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rabah, K.; Ladaci, S. A fractional adaptive sliding mode control configuration for synchronizing disturbed fractional-order chaotic systems. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 39, 1244–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaslik, E.; Rădulescu, I.R. Dynamics of complex-valued fractional-order neural networks. Neural Netw. 2017, 89, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biolek, D.; Petráš, I. Models of nonlinear higher-order elements for autonomous fractional circuits. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 34405–34421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.U.; Prakash, T. Recurrent neural network based design of fractional order power system stabilizer for effective damping of power oscillations in multimachine system. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Agerkvist, F. Fractional derivative loudspeaker models for nonlinear suspensions and voice coils. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 2018, 66, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Luo, H. Two-dimensional control of a fractional-order permanent magnetsynchronous motor model for industrial robots. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 249, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, S.; Chen, Z. Multi-objective optimal design of an optimal fuzzy fractional order PID controller for fractional order hydraulic turbine regulating system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 286, 127904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, K.; Kumar, S.; Alkahtani, B.S.; Alzaid, S.S. A numerical study on fractional order financial system with chaotic and Lyapunov stability analysis. Results Phys. 2024, 60, 107685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A.G.; Emira, A.A.; AbdelAty, A.M.; Azar, A.T. Modeling and analysis of fractional order DC-DC converter. ISA Trans. 2018, 82, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.I.; Adam, H.D.; Almutairi, N.; Saber, S. Analytical solutions for a class of variable-order fractional Liu system under time-dependent variable coefficients. Results Phys. 2024, 56, 107311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, A.H.; Shoaib, M.; Kiani, A.K.; Chaudhary, N.I.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Shu, C.-M. Dynamical analysis of nonlinear fractional order Lorenz system with a novel design of intelligent solution predictive radial base networks. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 213, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheghan, M.M.; Beheshti, M.T.H.; Tavazoei, M.S. Robust synchronization of perturbed Chen’s fractional-orderchaotic systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2011, 16, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fu, L.; He, S.; Yao, Z.; Wang, H.; Han, J. Hidden attractors in a new fractional-order Chua system with arctan nonlinearity and its DSP implementation. Results Phys. 2023, 52, 106866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional-order systems and PIλDμ-controllers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 1999, 44, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Fang, H. Deep fusion of discrete-time and continuous-time models for long-term prediction of chaotic dynamical systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 12545–12563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, K.; Yang, L. A novel chaotic system with 2-D grid multi-scroll chaotic attractors through quasi-sine function. Analog. Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2025, 123, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Sha, H.; Guo, R. Disturbance estimator-based reinforcement learning robust stabilization control for a class of chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 198, 116547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Li, H.; Dai, Q.; Yang, J. A deep reinforcement learning method to control chaos synchronization between two identical chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Li, H.; Liang, J.; Dai, Q.; Yang, J. Generalized synchronization between two distinct chaotic systems through deep reinforcement learning. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirandaz, H.; Hajipour, A. Adaptive synchronization and anti-synchronization of TSUCS and Lü unified chaotic systems with unknown parameters. Optik 2017, 130, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, P.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, S. Fixed-time cross-combination synchronization of complex chaotic systems with unknown parameters and perturbations. Integration 2025, 101, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora, L.M.; Carroll, T.L. Synchronization of Chaotic Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, X.; Fang, J.; Wang, Y. Autonomous memristor chaotic systems of infinite chaotic attractors and circuitry realization. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 94, 2879–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Lai, Y.-C. Long-term prediction of chaotic systems with machine learning. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Jin, J. A novel adaptive parameter zeroing neural network for the synchronization of complex chaotic systems and its field programmable gate array implementation. Measurement 2025, 242, 115989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binazadeh, T.; Jafari, E. Synchronization of chaotic fractional-order systems with input saturation and non-vanishing perturbations: Ultimate boundedness analysis and transient behavior improvement. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 2025, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Chen, F. Command filtered adaptive backstepping fuzzy synchronization control of uncertain fractional order chaotic systems with external disturbance. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 26, 2394–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Su, H.; Zeng, Y. Synchronization of uncertain fractional-order chaotic systemsvia a novel adaptive controller. Chin. J. Phys. 2017, 55, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Chen, L.; Liu, H. Command filtered adaptive neural network synchronization control of fractional-order chaotic systems subject to unknown dead zones. J. Frankl. Inst. 2021, 358, 3376–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, H. Adaptive T-S fuzzy synchronization for uncertain fractional-order chaotic systems with input saturation and disturbance. Inf. Sci. 2024, 666, 120423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modiri, A.; Mobayen, S. Adaptive terminal sliding mode control scheme for synchronization of fractional-order uncertain chaotic systems. ISA Trans. 2020, 105, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Roohi, M. Design of a model-free adaptive sliding mode control to synchronize chaotic fractional-order systems with input saturation: An application in secure communications. J. Frankl. Inst. 2021, 358, 8109–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z. Synchronization of fractional-order chaotic systems with non-identical orders, unknown parameters and disturbances via sliding mode control. Chin. J. Phys. 2018, 56, 2553–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabasi, M.; Hosseini, S.A.; Houshmand, M. Stable fractional-order adaptive sliding-based control and synchronization of two fractional-order Duffing-Holmes chaotic systems. J. Control. Autom. Electr. Syst. 2025, 36, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianwei, E.; Yu, L.; Heng, L.; Xiulan, Z. Adaptive fuzzy fault-tolerant control of fractional-order chaotic systems with full state constraints and actuator faults. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 27, 2322–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Hajipour, A.; Aminabadi, S.S. Synchronization of chaotic Arneodo system of incommensurate fractional order with unknown parameters using adaptive method. Optik 2016, 127, 7704–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Cai, L.; Cao, J. Linear control for synchronization of a fractional-order time-delayed chaotic financial system. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2018, 113, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulkroune, A.; Boubellouta, A.; Bouzeriba, A.; Zouari, F. Practical Finite-time fuzzy synchronization of chaotic systems with non-integer orders: Two chattering-free approaches. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2025, 34, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassafi, M.O.; Ha, S.; Alsaadi, F.E.; Ahmad, A.M.; Cao, J. Fuzzy synchronization of fractional-order chaotic systems using finite-time command filter. Inf. Sci. 2021, 579, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y. Novel finite-time convergent neural dynamics for practical synchronization of diverse chaotic systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 151, 109122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetha, S.; Sakthivel, R.; Harshavarthini, S. Finite-time synchronization of nonlinear fractional chaotic systems with stochastic actuator faults. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 142, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Berardehi, Z.R.; Roohi, M.; Khooban, M.H. A finite-time sliding mode control technique for synchronization chaotic fractional-order laser systems with application on encryption of color images. Optik 2023, 285, 170948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, H.; Mohadeszadeh, M. Robust Finite-time synchronization of non-identical fractional-order hyperchaotic systems and its application in secure communication. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2019, 6, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, X. Fixed-time tracking control for fractional-order uncertain parametric nonlinear systems with input delay: A command filter-based neuroadaptive control method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H. Leader-follower synchronization of heterogeneous dynamical networks with unknown parameters. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2025, 85, 104341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, Q.; Zhan, H.; Li, W.; Li, T. Command filter approximator-based fixed-time fuzzy control for uncertain nonlinear systems with input saturation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 147, 108808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, C.; Ge, Y. Adaptive neural network dynamic surface control of uncertain strict-feedback nonlinear systems with unknown control direction and unknown actuator fault. J. Frankl. Inst. 2022, 359, 4054–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishro, A.; Montazeri, S.J.; Shahrokhi, M. Fuzzy event-triggered control of fractional-order non-affine systems subject to unknown control directions, communication limitation, output constraints and input nonlinearities. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2025, 513, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Bao, H.; Guo, C.; Zhang, H. Adaptive fuzzy optimal attitude control for AUVs with input nonlinearity. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 329, 121105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zheng, S.; Ahn, C.K.; Liu, F. Adaptive fuzzy control for fractional-order interconnected systems with unknown control directions. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Dian, S.; Liu, K.; Guo, B.; Xiang, G.; Zhu, Y. Command filter-based adaptive fuzzy finite-time tracking control for uncertain fractional-order nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-X.; Wei, M.; Tong, S. Event-triggered adaptive neural control for fractional-order nonlinear systems based on finite-time scheme. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 9481–9489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Hu, X. Fractional order fixed-time nonsingular terminal sliding mode synchronization and control of fractional order chaotic systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 89, 2065–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Ma, C. A novel adaptive predefined-time sliding mode control scheme for synchronizing fractional order chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 189, 115610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, X. Finite-time tracking control for fractional-order nonlinear high-order parametric systems with time-varying control gain and external disturbances: An approximation-based adaptive control method. Adv. Contin. Discret. Models 2025, 2025, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, X. Adaptive Fuzzy Finite-Time Synchronization Control of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Uncertain Dynamics, Unknown Parameters and Input Nonlinearities. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120805

Zhang X, Feng C, Zhou Y, Deng X. Adaptive Fuzzy Finite-Time Synchronization Control of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Uncertain Dynamics, Unknown Parameters and Input Nonlinearities. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120805

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiyu, Chun Feng, Youjun Zhou, and Xiongfeng Deng. 2025. "Adaptive Fuzzy Finite-Time Synchronization Control of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Uncertain Dynamics, Unknown Parameters and Input Nonlinearities" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120805

APA StyleZhang, X., Feng, C., Zhou, Y., & Deng, X. (2025). Adaptive Fuzzy Finite-Time Synchronization Control of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Uncertain Dynamics, Unknown Parameters and Input Nonlinearities. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120805