Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Control for Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems Under DoS Attacks and Uncertain Emission Probabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A Novel System Model: In contrast to existing works that either assume fully known system modes or operate in attack-free environments [9,10,11,12], this work introduces a more realistic framework for hidden semi-Markov jump systems by simultaneously accounting for both incomplete emission probabilities and DoS attacks. This integrated model captures the compounded uncertainties arising from partial observability and adversarial interference, significantly enhancing its applicability to real-world networked control systems under imperfect and insecure communication conditions.

- A Pioneering FOSMC Strategy: Departing from prior control designs [16,23,24], this paper proposes, to the best of our knowledge, the first FOSMC scheme for HS-MJSs. The core of this strategy is a novel sliding surface constructed using the Grünwald–Letnikov (G-L) difference operator, which actively leverages the entire history of system states and sojourn times. This inherent memory effect is the key to achieving accelerated convergence and enhanced robustness against the combined uncertainties of DoS attacks and incomplete emission probabilities.

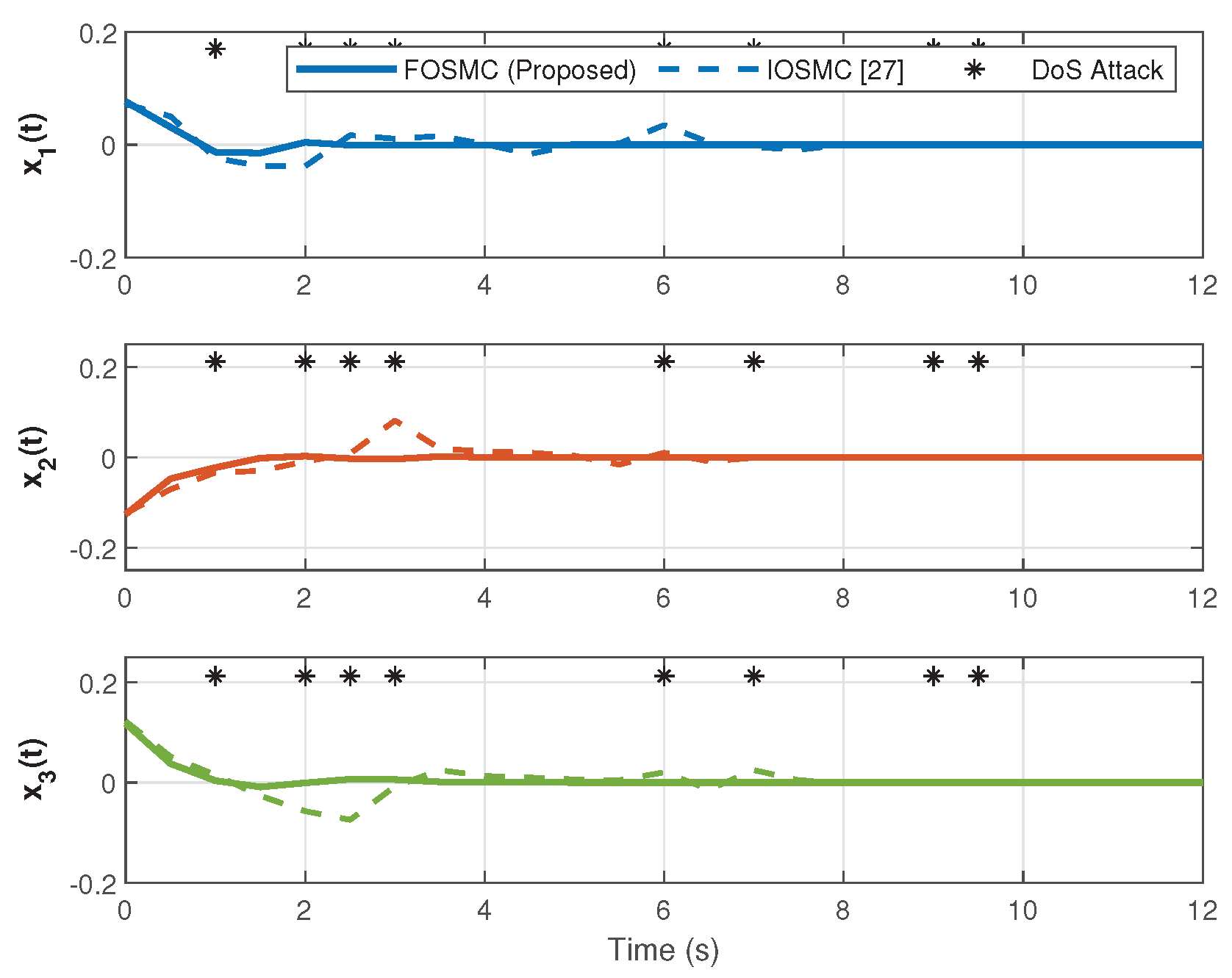

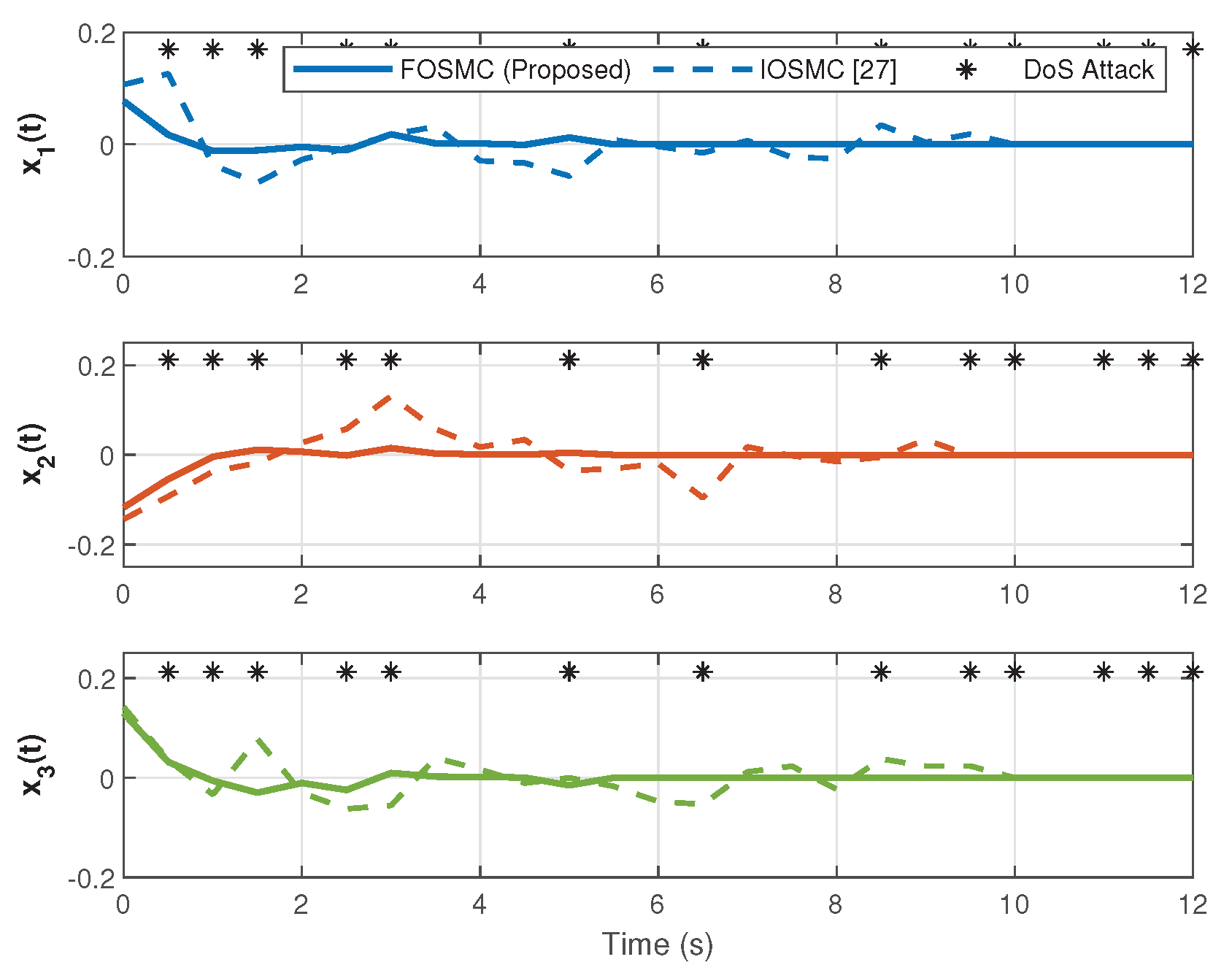

- Demonstrated Superiority: Theoretical analysis and numerical simulations demonstrate that the proposed FOSMC law not only ensures MSS but also achieves significantly faster convergence compared to conventional IOSMC, thereby validating its effectiveness in enhancing dynamic performance under compound uncertainties.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. System Description Under DoS Attacks and Uncertainties

2.2. Modeling Framework, Assumptions, and Signal Flow

- Assumption 1 (System Dynamics): The plant is modeled as the discrete-time S-MJS (1). The parameter uncertainty is assumed to be structured as , where and are known matrices, and is an unknown matrix satisfying . The input matrix is assumed to be of full column rank for all modes .

- Assumption 2 (Hidden Semi-Markov Process): The true system mode , which evolves as a semi-Markov chain, is not directly accessible to the controller. Instead, the controller has access to two signals: (1) the observed mode , and (2) the elapsed sojourn time of the activated mode.

- Assumption 3 (Incomplete Emission Probabilities): The relationship between the true mode and the observed mode is governed by the emission probability . These probabilities are partially unknown; for each true mode a, the set of observed modes is partitioned into a known set and an unknown set .

- Assumption 4 (DoS Attack Model): The communication channel from the sensor (measuring ) to the controller’s buffer is vulnerable to DoS attacks. The attacks are modeled as a stochastic process governed by a Bernoulli variable with a known probability .

- –

- If (no attack), the controller’s buffer receives the current state .

- –

- If (attack occurs), the data packet is lost, and the controller must use the previously buffered state .

The resulting state available to the controller is described by the buffer logic in (4): .

2.3. Mathematical Foundations of Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems

2.4. Fractional-Order Operators for Enhanced Control Design

2.5. A Key Stability Lemma

3. Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Controller

3.1. Fractional-Order Sliding Surface Design

3.2. Sliding Mode Dynamics Under Fractional-Order Surface

3.3. Closed-Loop Dynamics and Stability Analysis

3.4. Mean Square Stability Analysis

3.5. Reachability Analysis

4. Numerical Simulation

- Settling Time (): Defined as the time required for the system state norm to enter and permanently remain within a bounded error band (set as of the initial deviation) of the equilibrium point. This index evaluates the convergence speed of the system.

- Integral Square Error (ISE): Calculated as , where is the simulation duration. This index serves as a cumulative measure of the transient response quality and steady-state precision.

- Control Effort (U): Defined as . This index reflects the total energy consumption required by the controller to stabilize the system, characterizing the cost-effectiveness of the control strategy.

4.1. System Configuration and Parameters

4.2. Simulation Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| System state vector | |

| Underlying operational mode (inaccessible) | |

| Emitted mode (available for controller) | |

| Elapsed sojourn time in the activated mode | |

| System matrices for mode a | |

| Parameter uncertainty | |

| Emission probability | |

| Sets of known and unknown observed modes | |

| Bernoulli variable for DoS attack | |

| Mean DoS attack probability | |

| Buffered state available to the controller | |

| Maximum sojourn time for mode a | |

| Fractional-order sum operator (G-L) | |

| Fractional-order sliding surface variable | |

| Controller gain for observed mode i and sojourn time | |

| Dimensions of state, true modes, and observed modes | |

| Mathematical expectation |

References

- Lian, J.; Wu, F.Y. Stabilization of switched linear systems subject to actuator saturation via invariant semiellipsoids. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 4332–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Niu, Y.G.; Xu, J. An event-triggered approach to sliding mode control of Markovian jump Lur’e systems under hidden mode detections. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kchaou, M.; Jerbi, H.; Abassi, R.; VijiPriya, J.; Hmidi, F.; Kouzou, A. Passivity-based asynchronous fault-tolerant control for nonlinear discrete-time singular Markovian jump systems: A sliding-mode approach. Eur. J. Control 2021, 60, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. Razumikhin-type theorem for stochastic functional differential equations with lévy noise and Markov switching. Int. J. Control 2017, 90, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, Q. Stability analysis of Markov switched stochastic differential equations with both stable and unstable subsystems. Syst. Control Lett. 2017, 105, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C.; Haddad, A.H. Control of jump linear systems having semi-Markov sojourn times. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE International Conference on Decision and Control, Maui, HI, USA, 9–12 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Shi, Y. Stochastic stability and robust stabilization of semi-Markov jump linear systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2013, 23, 2028–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Han, Q.-L.; Wang, L.; Sindi, E. Distributed cooperative optimal control of DC microgrids with communication delays. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 3924–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, Q. Stability Analysis of discrete-time Semi-Markov jump linear systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 5415–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, F.; Xu, S.; Sreeram, V. Slow state variables feedback stabilization for semi-Markov jump systems with singular perturbations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 63, 2709–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Cai, B.; Weng, R.; Su, S.-F. Stability and control of fuzzy semi-Markov jump systems under unknown semi-Markov kernel. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 2452–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Sha, M.; Park, J.H.; Wu, Z.-G.; Yan, H. Observer-Based Asynchronous Control of discrete-time Semi-Markov Switching Power Systems Under DoS Attacks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 6424–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, W. Energy-to-peak state estimation for Markov jump RNNs with time-varying delays via nonsynchronous filter with nonstationary mode transitions. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 2346–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, W. Synchronization and state estimation of a class of hierarchical hybrid neural networks with time-varying delays. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 27, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, B.; Shi, Y. Stabilization of hidden semi-Markov jump systems: Emission probability approach. Automatica 2019, 101, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, B.; Tan, T. Stabilization of non-homogeneous hidden semi-Markov Jump systems with limited sojourn time information. Automatica 2020, 117, 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, Z.; Niu, B.; Zhao, N. Dynamic-Event-Based Reachable Set Synthesis for Nonlinear Delayed Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems Under Multiple Cyber-Attacks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 55, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.G. Dynamic Event-Triggered Resilient Control of Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems Against Asynchronous DoS Attacks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 13635–13645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lam, H.K. Security-based fuzzy control for nonlinear networked control systems with DoS attacks via a resilient event-triggered scheme. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 4359–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suid, M.H.; Ahmad, M.A.; Ismail, R.M.T.R. Optimal tuning of sigmoid PID controller using Nonlinear Sine Cosine Algorithm for the Automatic Voltage Regulator system. ISA Trans. 2022, 128, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Tumari, M.Z.; Ahmad, M.A.; Suid, M.H. An improved marine predators algorithm tuned data-driven multiple-node hormone regulation neuroendocrine-PID controller for multi-input–multi-output gantry crane system. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2023, 42, 1666–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etedali, S.; Sohrabi, M.R. Novel Adaptive Intelligent Control Scheme with Self-Evolving Genetic Fuzzy BELBIC for Enhancing the Seismic Resilience of Smart Building Structures. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2025, 11, 04025019. [Google Scholar]

- Che, Z.; Yu, H.; Yang, C.; Zhou, L. Passivity analysis and disturbance observer-based adaptive integral sliding mode control for uncertain singularly perturbed systems with input non-linearity. IET Control Theory Appl. 2019, 13, 3174–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kao, Y.; Xie, J. Adaptive sliding mode control for semi-Markov jump uncertain discrete-time singular systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2023, 33, 10824–10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Song, Z. Sliding mode control for discrete-time descriptor Markovian jump systems with two Markov chains. Optim. Lett. 2018, 12, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Ma, Y.; Wang, C. Memory sliding mode control for semi-Markov jump system with quantization via singular system strategy. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2019, 29, 6555–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, G. Sliding-mode-based admissible consensus of nonlinear singular stochastic uncertain semi-Markov multi-agent systems with time-varying delay. J. Eng. 2022, 7, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Ho, D.W.C. Design of Sliding Mode Control Subject to Packet Losses. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2010, 55, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.H.; Hou, Y.K.; Park, J.H.; Zong, G.D.; Shi, Y. SMC for uncertain discrete-time semi-Markov switching systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst.—II Express Briefs 2021, 69, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.H.; Zhang, N.; Zong, G.D.; Su, S.F.; Cao, J.D.; Cheng, J. Asynchronous sliding-mode control for discrete-time networked hidden stochastic jump systems with cyber attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.B.; Kar, I.N. Observer-based synchronization scheme for a class of chaotic nonlinear systems using fractional-order non-singular terminal sliding mode control. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 78, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Aghababa, M.P. No-chatter variable structure control for fractional-order nonlinear systems with unknown disturbances. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 73, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Duan, R. Mode-dependent non-fragile observer-based controller design for fractional-order T-S fuzzy systems with Markovian jump via non-PDC scheme. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2019, 34, 74–91. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Kao, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhao, X. Observer-Based Adaptive Sliding Mode Control for Markovian Jumping Fuzzy Systems with Fractional Brownian Motions. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 32, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwas, M.; Mozyrska, D. Stability of Linear Discrete–Time Systems with Fractional Positive Orders. In Theoretical Developments and Applications of Non-Integer Order Systems, Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Non-Integer Order Calculus and Its Applications, Szczecin, Poland, 28–29 August 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Du, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L. Finite-Time Stability and Stabilization for Discrete-Time Fractional-Order Systems with Time-Varying Delay. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 6674–6684. [Google Scholar]

| Ref. | System Model a | DoS Attacks | Incomplete Emission | Control Method b | LMI-Based Proof | Computational Complexity c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | ∘ | √ | × | ∘ | √ | ∘ |

| [29] | □ | × | × | □ | √ | ∘ |

| [30] | ■ | √ | × | □ | × | □ |

| This paper | ■ | √ | √ | ■ | √ | ■ |

| Performance Index | FOSMC (This Work) (Mean ± Std) | IOSMC [30] (Mean ± Std) |

|---|---|---|

| Settling Time () | ||

| Error (ISE) | ||

| Control Effort (U) |

| Performance Index | FOSMC (This Work) (Mean ± Std) | IOSMC [30] (Mean ± Std) |

|---|---|---|

| Settling Time () | ||

| Error (ISE) | ||

| Control Effort (U) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Peng, S. Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Control for Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems Under DoS Attacks and Uncertain Emission Probabilities. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120776

Wang J, Peng S. Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Control for Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems Under DoS Attacks and Uncertain Emission Probabilities. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):776. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120776

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Juan, and Shiguo Peng. 2025. "Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Control for Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems Under DoS Attacks and Uncertain Emission Probabilities" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120776

APA StyleWang, J., & Peng, S. (2025). Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Control for Hidden Semi-Markov Jump Systems Under DoS Attacks and Uncertain Emission Probabilities. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120776