The Research on Pore Fractal Identification and Evolution of Cement Mortar Based on Real-Time CT Scanning Under Uniaxial Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Method

2.1. Samples

2.2. RT-CT Experiments

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Augmentation and Image Segmentation

3.2. Reconstruction of Pore Structures

4. Data Analysis

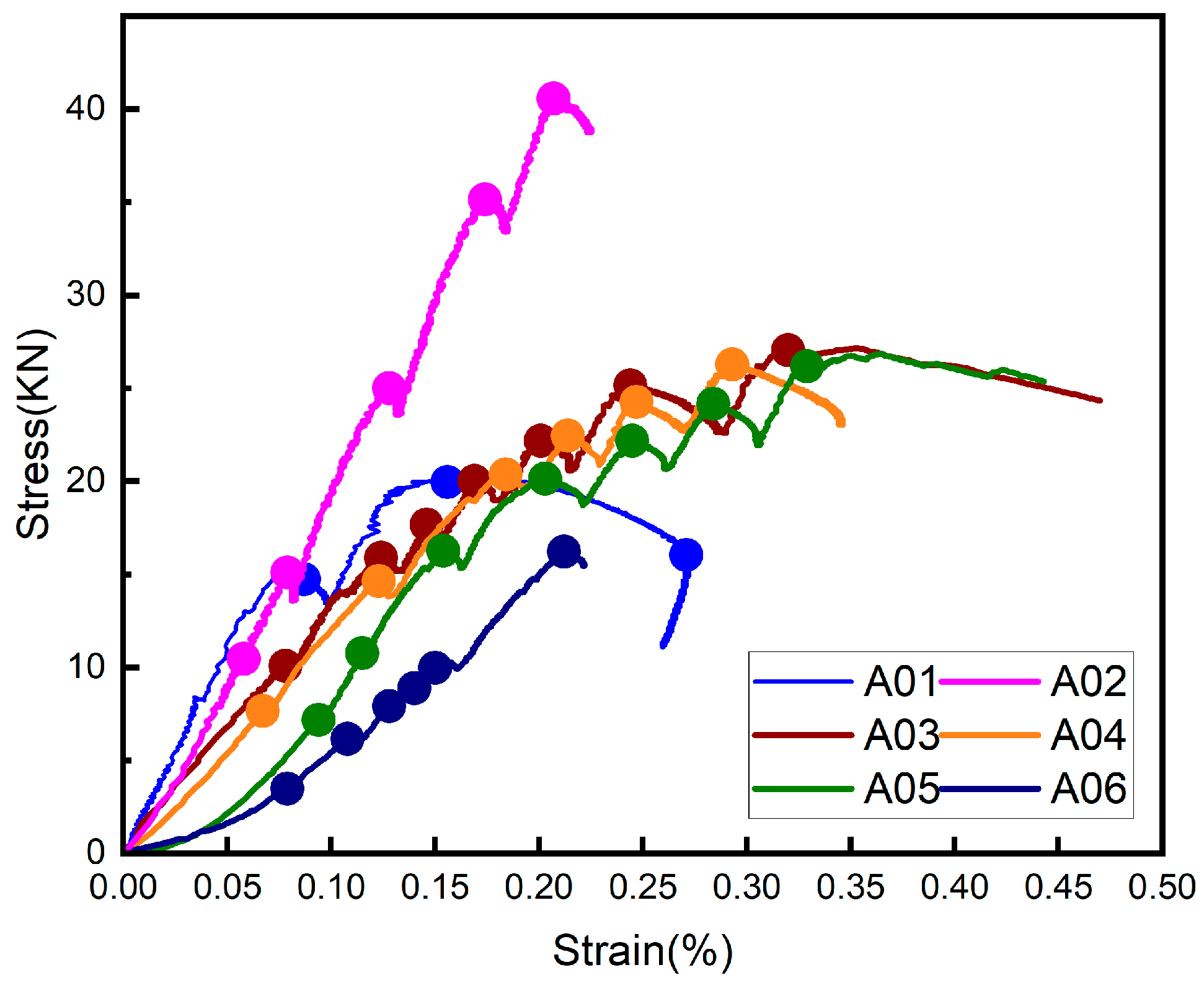

4.1. Experimental Analysis

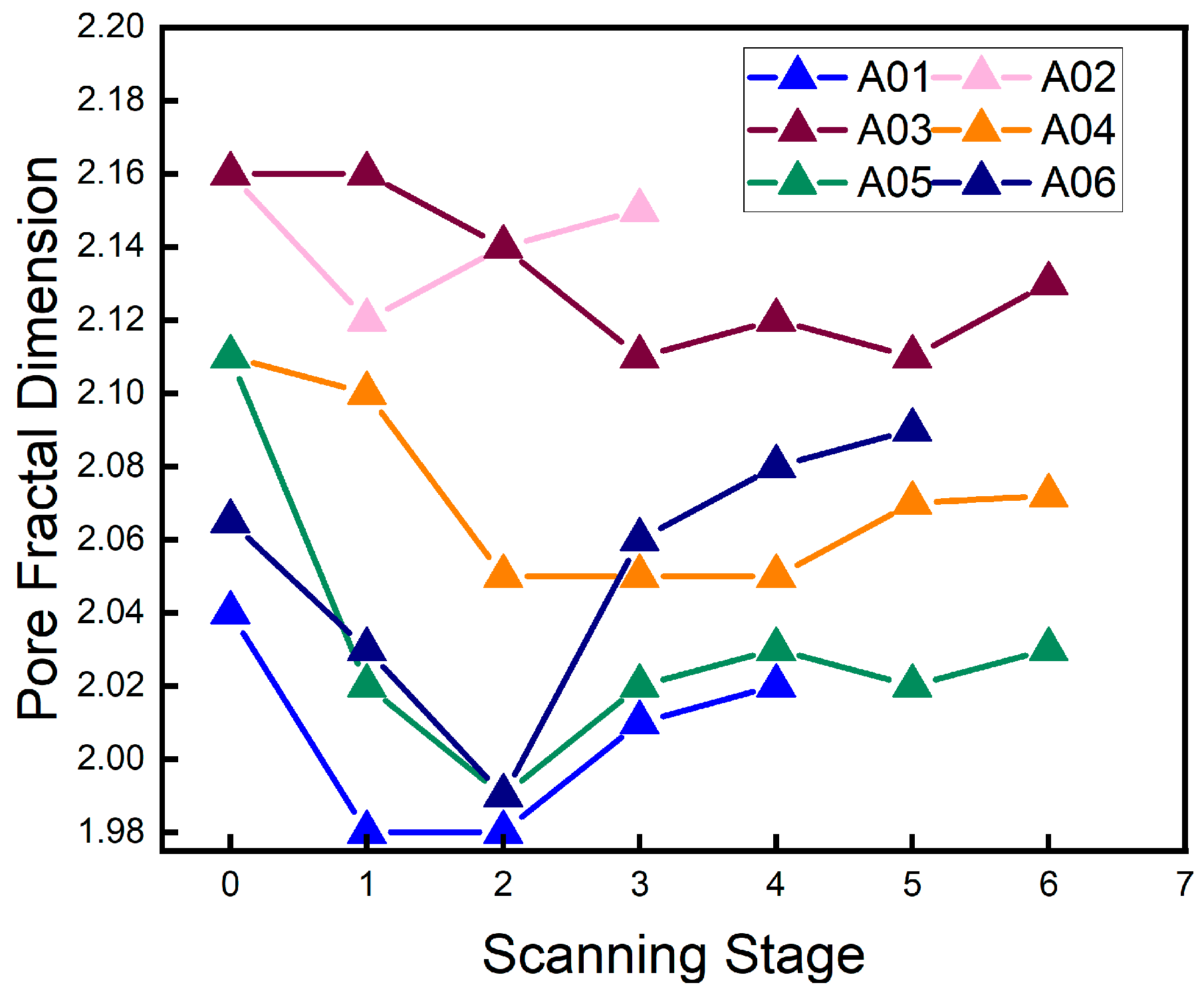

4.2. Pore Fractal Dimension Evolution

5. Discussion

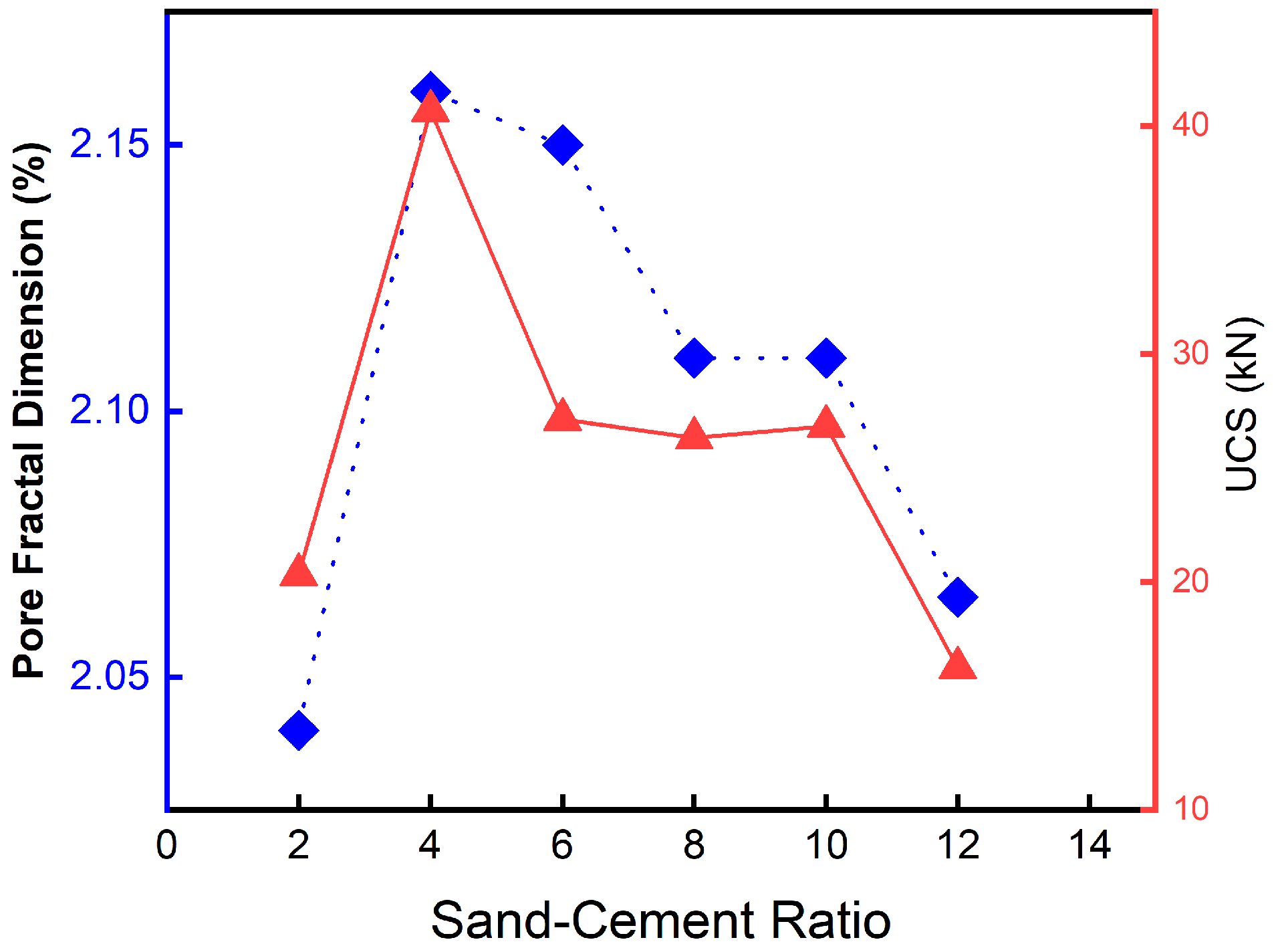

5.1. Fractal Dimensions and UCS Analysis

5.2. Statistical Methods and Analysis

6. Conclusions

- In the application of real-time loading scanning tests on rocks, the results from the stress–strain analysis show that the strength is maximized at a 4:1 ratio, where a skeleton structure is formed internally. This skeleton structure provides better support and stability, thereby enhancing the overall compressive performance of the material. At a 12:1 ratio, the strength is weaker, and the number of internal interfaces increases. As the samples lack sufficient tensile strength to withstand this internal pressure, microcracks will develop. The optimal 4:1 sand–cement ratio could provide a quantitative framework for High-Performance Concrete (HPC) Design in Construction Engineering.

- The sand–cement ratio significantly influences both porosity and fractal characteristics. As the sand content increases, the fractal dimensions also rise. However, when the sand content reaches a ratio of 4:1, the specimens exhibit maximum uniaxial compressive strength (UCS). The fractal characteristics align with the UCS behavior. Beyond the 4:1 ratio, the fractal dimensions begin to decrease. The growth of fractals enhances the contact area between particles, facilitating the formation of a skeletal structure. The relationship between porosity, fractal dimension, and strength can help understand the pavement deformation under cyclic traffic loads.

- Three statistical correlation analyses, Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall, were conducted among UCS, porosity, fractal dimension and pore diameter variance. The analysis revealed that increased porosity and variance of pore diameter negatively impact UCS, while a significant positive correlation exists between fractal dimensions. A multiple linear regression model demonstrated reliable predictors, with VIF values smaller than 10, indicating stability in the regression coefficients. Additionally, the results from the Lasso regression were consistent with those obtained from the linear regression model. The results indicate that the mechanism of rock strength formation is relatively complex and is not controlled by a single factor. The differences in UCS are likely due to the combined effects of pore size distribution and skeletal strength. This research offers theoretical methods and practical references for related cement mortar engineering fields.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sand to Cement Ratio | 2:1 | 4:1 | 6:1 | 8:1 | 10:1 | 12:1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCS/kN | 20.33 | 40.67 | 27.14 | 26.32 | 26.83 | 16.24 |

| Porosity/% | 2.90 | 2.20 | 2.70 | 2.10 | 2.30 | 2.08 |

| Fractal Dimension | 2.04 | 2.16 | 2.15 | 2.11 | 2.11 | 2.06 |

| EqDiameter Variance | 12.02 | 8.34 | 12.43 | 5.87 | 7.36 | 12.47 |

References

- Fathifazl, G.; Abbas, A.; Razaqpur, A.G.; Isgor, O.B.; Fournier, B.; Foo, S. New mixture proportioning method for concrete made with coarse recycled concrete aggregate. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2009, 21, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, W.; Ou, J. Material and structural properties of recycled coarse aggregate concrete made with seawater and sea-sand: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ding, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. Bond behavior between BFRP bar and basalt fiber reinforced seawater sea-sand recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, T.; Sun, H.; Li, C.; Yin, L.; Wang, Q. Mechanical properties of fibre reinforced seawater sea-sand recycled aggregate concrete under axial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 331, 127338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Yaseen, S.A.; Chen, K.; Niu, D.; Leung, C.K.Y.; Li, Z. Study of the influence of seawater and sea sand on the mechanical and microstructural properties of concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, M.; Gonzalez-Corominas, A.; Pardo, P. Influence of seawater and blast furnace cement employment on recycled aggregate concretes’ properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 115, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.C.; Mena, Á.; Mínguez, J.; Vicente, M.A. Influence of air-entraining agent and freeze-thaw action on pore structure in high-strength concrete by using CT-Scan technology. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 192, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Tian, W. Experimental study on the dynamic mechanical properties of concrete under freeze–thaw cycles. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Su, C.; Qiao, P.; Sun, L. Microstructural damage evolution and its effect on fracture behavior of concrete subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2018, 27, 1272–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W.; Zhou, S.; Long, K.; Xie, B.; Ai, C.; Yan, C. Investigation of key morphological parameters of pores in different grades of asphalt mixture based on CT scanning technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 434, 136770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chaouadi, R.; Noels, L.; Uytdenhouwen, I.; Lambrecht, M.; Pardoen, T. Effect of pre-crack non-uniformity for mini-CT geometry in ductile tearing regime. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 2023, 126, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yang, S.; Xi, X.; Shipton, Z.K.; Minto, J.; Hu, X. In-situ X-ray micro-CT quantitative analysis and modelling the damage evolution in granite rock. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 2024, 133, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stappen, J.F.; De Kock, T.; De Schutter, G.; Cnudde, V. Uniaxial compressive strength measurements of limestone plugs and cores: A size comparison and X-ray CT study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 5301–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dai, X.; Yang, G.; Shen, Y.; Pan, P.; Xi, J.; Li, B.; Liang, B.; Wei, Y.; Huang, H. Damage evolution characteristics of freeze–thaw rock combined with CT image and deep learning technology. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlach, M.B.; Kalbitzer, H.R.; Winter, R.; Kremer, W. Conformational substates of amyloidogenic hIAPP revealed by high pressure NMR spectroscopy. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 3239–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifai, H.; Staude, A.; Meinel, D.; Illerhaus, B.; Bruno, G. In-situ pore size investigations of loaded porous concrete with non-destructive methods. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 111, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Badger, S.; Thaulow, N.; Lee, R. Determination of water–cement ratio of hardened concrete by scanning electron microscopy. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, S.; Lyu, Z.; Shen, A.; Yin, L.; Xue, C. Pore structure characteristics and performance of construction waste composite powder-modified concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Huo, W.; Sun, H.; Ma, B.; Yang, L. Correlations between unconfined compressive strength, sorptivity and pore structures for geopolymer based on SEM and MIP measurements. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ding, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, F. Fractal analysis of cement-based composite microstructure and its application in evaluation of macroscopic performance of cement-based composites: A review. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuldasheva, A.; Huang, B.; Kuldashev, K.; Li, B.; Saidmuratov, B. Fractal Geometry-based Porosity Analysis of Cementitious Composite Material Using Wollastonite Under Freeze-thaw Condition. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2025, 40, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, W.; Ren, P. Overview of the application of quantitative backscattered electron (QBSE) image analysis to characterize the cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 406, 133332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.D.; Rahul, A.; Santhanam, M. A multi-analytical approach for pore structure assessment in historic lime mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, R.S.; Mushthofa, M.; Gruyaert, E.; De Belie, N. Quantitative analysis on porosity of reactive powder concrete based on automated analysis of back-scattered-electron images. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żak, A.M.; Wieczorek, A.; Chowaniec, A.; Sadowski, Ł. Segmentation of pores in cementitious materials based on backscattered electron measurements: A new proposal of regression-based approach for threshold estimation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Sun, D.; Yu, F.; Gao, Z.; Sun, S.; Zheng, Z. Analyzing the pore structure of pervious concrete based on the deep learning framework of Mask R-CNN. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318, 125987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, Z. Intelligent inspection of appearance quality for precast concrete components based on improved YOLO model and multi-source data. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 32, 1691–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheniour, A.; Ziabari, A.K.; Le Pape, Y. A mesoscale 3D model of irradiated concrete informed via a 2.5 U-Net semantic segmentation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 412, 134392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangaru, S.S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Hassan, M. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image segmentation for microstructure analysis of concrete using U-net convolutional neural network. Autom. Constr. 2022, 144, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ma, F.; Guo, J.; Zhao, H. Experimental study on similar materials ratio used in large-scale engineering model test. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 41, 1653. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T-50266-2013; Standard for Tests Method of Engineering Rock Mass. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Clavaud, J.B.; Maineult, A.; Zamora, M.; Rasolofosaon, P.; Schlitter, C. Permeability anisotropy and its relations with porous medium structure. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2008, 113, B01202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatakakis, N.; Koukis, G.; Tsiambaos, G.; Papanakli, S. Index properties and strength variation controlled by microstructure for sedimentary rocks. Eng. Geol. 2008, 97, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; He, J.; Ma, C. Experimental Investigations On rate-Dependent Stress-Strain Characteristics and Energy Mechanism of Rock Under Uniaixal Compression. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2012, 31, 1830–1838. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: High quality object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 43, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, B.; He, J.; Hao, J. Cracking evolution and failure characteristics of Longmaxi shale under uniaxial compression using real-time computed tomography scanning. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 3003–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, X.; Mao, T.; Zheng, B.; Wu, Y.; Li, G. Fracture evolution analysis of soil-rock mixture in contrast with soil by CT scanning under uniaxial compressive conditions. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 64, 2771–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.H.; Hu, Y.Z. 3D image visualization of meso-structural changes in a bimsoil under uniaxial compression using X-ray computed tomography (CT). Eng. Geol. 2019, 248, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palchik, V. Application of Mohr–Coulomb failure theory to very porous sandy shales. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2006, 43, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Qiao, L.; Li, Q. Study on cross-scale pores fractal characteristics of granite after high temperature and rock failure precursor under uniaxial compression. Powder Technol. 2022, 401, 117330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarian, B. Estimating the scale dependence of permeability at pore and core scales: Incorporating effects of porosity and finite size. Adv. Water Resour. 2022, 161, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, L.; Hu, F.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Xu, H.; Lu, S.; Xue, Q. Pore-scale characterization of tight sandstone in Yanchang Formation Ordos Basin China using micro-CT and SEM imaging from nm-to cm-scale. Fuel 2017, 209, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Number | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A012:1 | 0.03 | 8.39 | 0.87 | 14.73 | 0.156 | 19.95 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| A024:1 | 0.08 | 15.10 | 0.12 | 25.09 | 0.173 | 35.26 | 0.21 | 40.58 | - | - | - | - |

| A036:1 | 0.07 | 10.06 | 0.12 | 15.87 | 0.146 | 17.67 | 0.169 | 19.99 | 0.24 | 25.16 | 0.32 | 27.02 |

| A048:1 | 0.06 | 7.64 | 0.12 | 14.62 | 0.18 | 20.35 | 0.21 | 22.45 | 0.24 | 24.25 | 0.29 | 26.27 |

| A0510:1 | 0.94 | 7.18 | 0.15 | 16.26 | 0.20 | 20.12 | 0.24 | 22.18 | 0.28 | 24.17 | 0.32 | 26.17 |

| A0612:1 | 0.79 | 3.47 | 0.10 | 6.15 | 0.12 | 7.90 | 0.14 | 8.88 | 0.15 | 9.97 | 0.21 | 16.20 |

| s-w | p < 0.05 | Normal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCS | 0.906 | N | Y |

| Pore Fractal | 0.934 | N | Y |

| Porosity | 0.856 | N | Y |

| Diameter | 0.845 | N | Y |

| Pearson (r) | UCS | Pore Fractal | Porosity | EqDiameter Var |

| UCS | 1 | 0.8456 | −0.1735 | −0.4983 |

| Pore Fractal | 0.8456 | 1 | −0.0938 | −0.3719 |

| Porosity | −0.1735 | −0.0938 | 1 | 0.5862 |

| EqDiameterVar | −0.4983 | −0.3719 | 0.5862 | 1 |

| Spearman (ρ) | UCS | Pore Fractal | Porosity | EqDiameter Var |

| UCS | 1 | 0.9276 | 0.2571 | −0.3143 |

| Pore Fractal | 0.9276 | 1 | 0.0294 | −0.2319 |

| Porosity | 0.2571 | 0.0294 | 1 | 0.0580 |

| EqDiameterVar | −0.3143 | −0.2319 | 0.0580 | 1 |

| Kendall (τ) | UCS | Pore Fractal | Porosity | EqDiameter Var |

| UCS | 1 | 0.8281 | 0.2000 | −0.2000 |

| Pore Fractal | 0.8281 | 1 | 0.0714 | −0.1380 |

| Porosity | 0.2000 | 0.0714 | 1 | 0.1380 |

| EqDiameterVar | −0.2000 | −0.1380 | 0.1380 | 1 |

| Pearson | UCS | Pore Fractal | Porosity | EqDiameter Var |

| UCS | 1 | 0.0339 | 0.7423 | 0.3144 |

| Pore Fractal | 0.033 | 1 | 0.8598 | 0.4679 |

| Porosity | 0.7423 | 0.8598 | 1 | 0.2215 |

| EqDiameterVar | 0.3144 | 0.4679 | 0.2215 | 1 |

| Spearman | UCS | Pore Fractal | Porosity | EqDiameter Var |

| UCS | 1 | 0.0077 | 0.6228 | 0.5441 |

| Pore Fractal | 0.0077 | 1 | 0.9559 | 0.6584 |

| Porosity | 0.6228 | 0.9559 | 1 | 0.9131 |

| EqDiameterVar | 0.5441 | 0.6584 | 0.9131 | 1 |

| Kendall | UCS | Pore Fractal | Porosity | EqDiameter Var |

| UCS | 1 | 0.0217 | 0.7194 | 0.7194 |

| Pore Fractal | 0.0217 | 1 | 0.8457 | 0.7021 |

| Porosity | 0.7194 | 0.8457 | 1 | 0.7021 |

| EqDiameterVar | 0.7194 | 0.7021 | 0.7021 | 1 |

| Variable | Coefficient | p < 0.05 | VIF | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −256.3452 | N | 0.7721 | F = 2.2583 p = 0.3216 | |

| Porosity | 3.9077 | N | 1.445 | ||

| Pore Fractal | 133.8091 | N | 1.161 | ||

| EqDiameter Var | −0.8584 | N | 1.598 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Zou, Y.; Mao, T.; Chen, P.; Kong, H.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Li, G. The Research on Pore Fractal Identification and Evolution of Cement Mortar Based on Real-Time CT Scanning Under Uniaxial Loading. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110689

Wu Y, Li X, Zou Y, Mao T, Chen P, Kong H, Li J, Li M, Li G. The Research on Pore Fractal Identification and Evolution of Cement Mortar Based on Real-Time CT Scanning Under Uniaxial Loading. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(11):689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110689

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yanfang, Xiao Li, Yu Zou, Tianqiao Mao, Ping Chen, Huihua Kong, Jinmiao Li, Mingtao Li, and Guang Li. 2025. "The Research on Pore Fractal Identification and Evolution of Cement Mortar Based on Real-Time CT Scanning Under Uniaxial Loading" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 11: 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110689

APA StyleWu, Y., Li, X., Zou, Y., Mao, T., Chen, P., Kong, H., Li, J., Li, M., & Li, G. (2025). The Research on Pore Fractal Identification and Evolution of Cement Mortar Based on Real-Time CT Scanning Under Uniaxial Loading. Fractal and Fractional, 9(11), 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110689