Fractional Grey Breakpoint Model for Forecasting PM2.5 Under Energy Policy Shock

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fractional Breakpoint Grey Model

2.1. Novel Fractional Breakpoint Grey Model FBGM(s,t)

2.2. Model Application Hypothesis

2.3. FBGM(s,t) Empirical Framework Design

3. Empirical Research

3.1. Case Characteristics

3.2. Model Validation

3.3. Robustness Analyze

4. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

4.1. Research Conclusions

- (1)

- The new-energy demonstration policy has effectively reduced high-emission fossil fuels’ proportion in end-use sectors through multiple synergistic mechanisms, including energy structural adjustment, end-use transformation, and infrastructural coordination. It has created stable PM2.5 emission reduction effects over time. Because of the highly concentrated pollution emissions and significant cross-boundary transmission within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei agglomeration, the policy shock presents strong marginal emission reduction flexibility and regional linkage characteristics in this region. This study has validated the demonstration policies’ practical effectiveness in highly sensitive regions.

- (2)

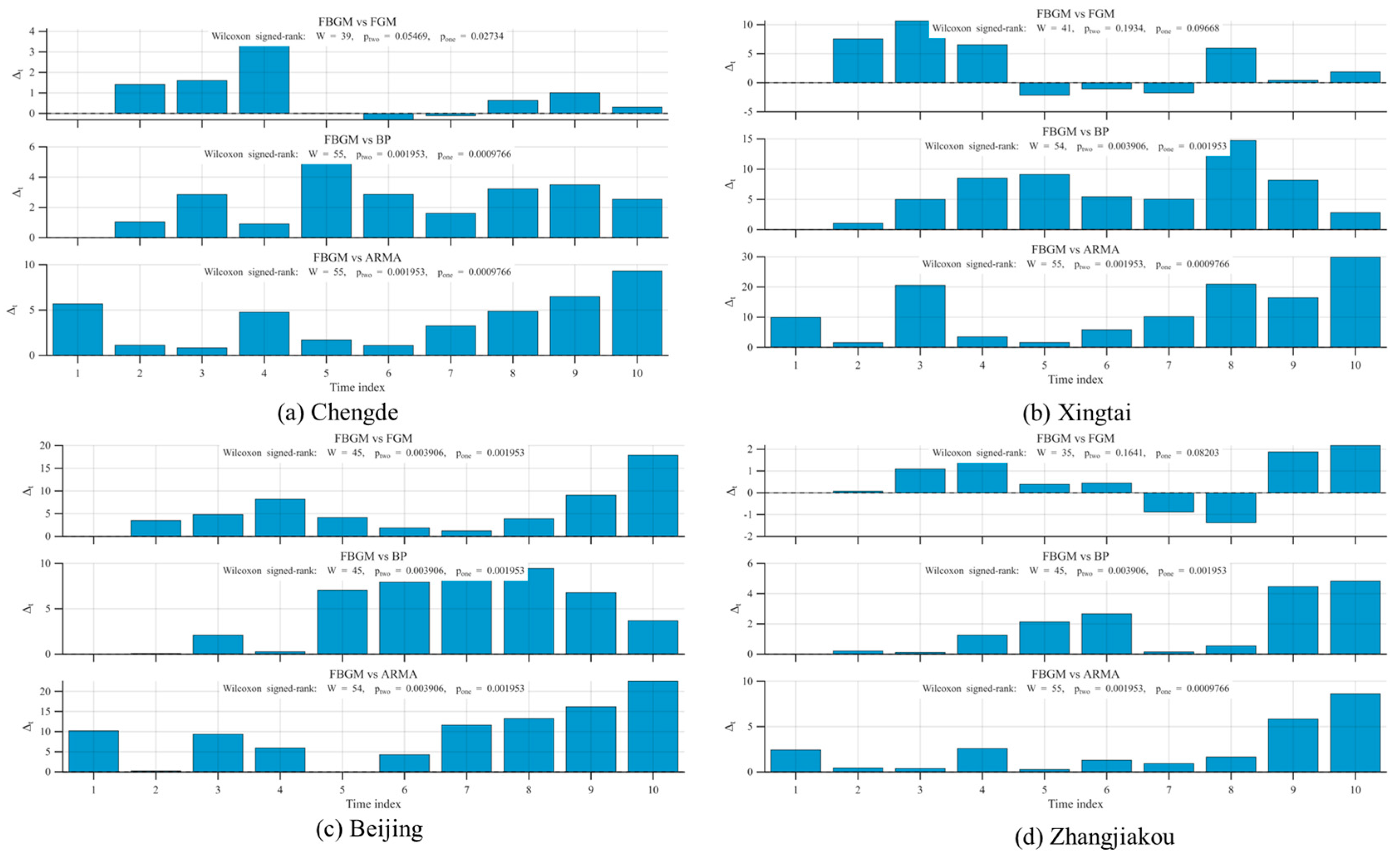

- Multidimensional error indicators showed that FBGM(s,t) significantly outperformed traditional grey models, neural network models, and statistical models across all four pilot cities. Its superiority manifested not only in in-sample fitting accuracy but also in out-of-sample forecasting and stability under policy shock scenarios. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that the advantage was statistically significant over time.It suggested that the model performance improvement was not driven by individual extreme observations, but rather possessed systematicity and generalizability.

- (3)

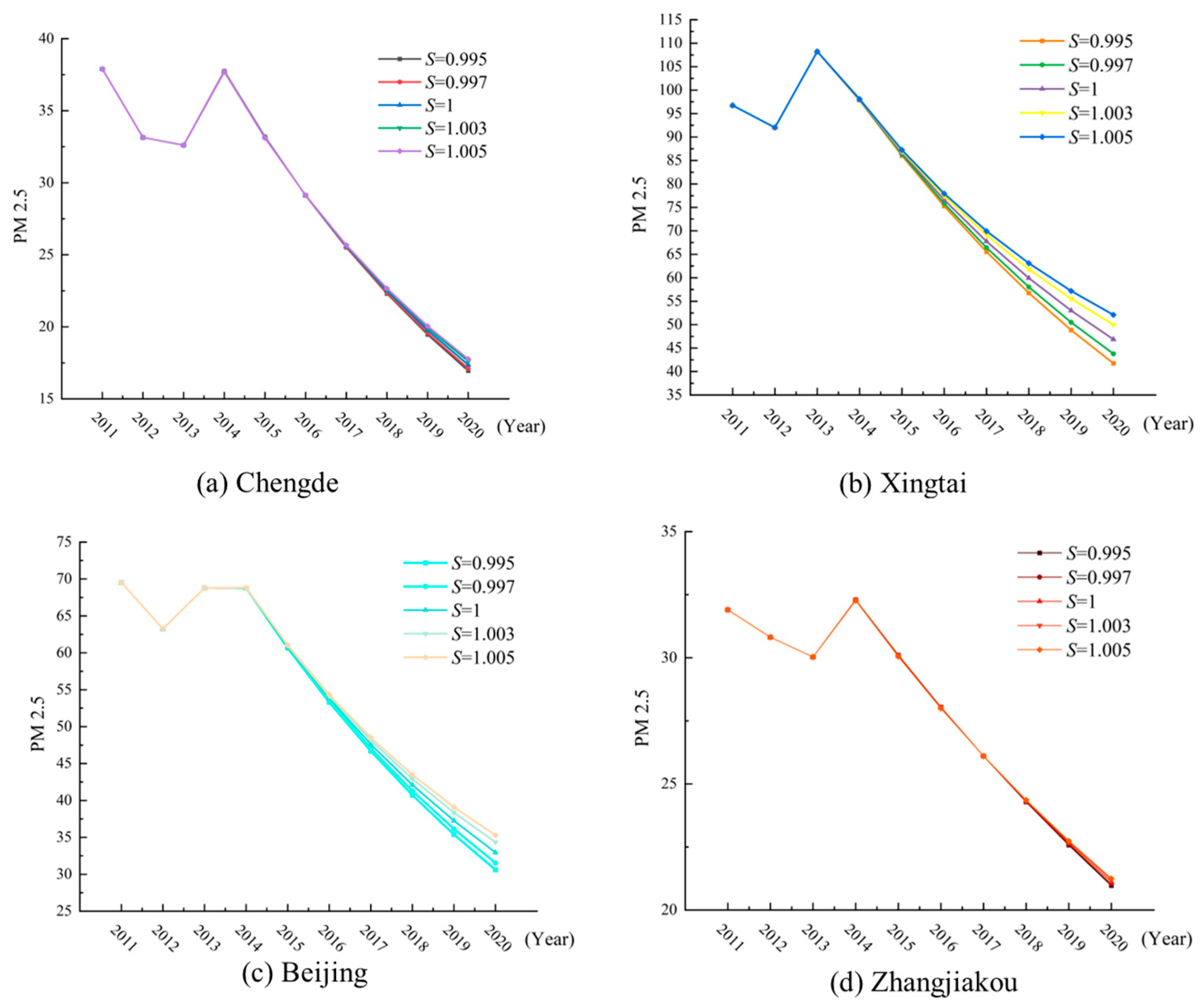

- Robustness analyzes revealed largely unchanged relative performance ranks of FBGM(s,t) across cities when adjusting the shock parameter within a reasonable range. Forecast errors only showed smooth fluctuations. This result indicated that the model’s policy shock evolution mechanism benefitted primarily from structural design rather than a reliance on specific parameters. This characteristic enhanced the model’s applicability and credibility within heterogeneous city scenarios.

4.2. Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Government department. Considering that the new-energy demonstration policy has continuous and systematic suppression effects on PM2.5 in highly pollution-sensitive regions, government departments should integrate new-energy substitution with air quality improvement targets into a medium-to-long-term coordinated governance framework. This approach will mitigate policy ineffectiveness risks. In regions with significant cross-boundary pollution, governments should leverage unified planning, coordinated assessment, and information-sharing mechanisms to expand the new-energy policy’s spillover emission reduction effect, enhancing policy implementation stability and continuity.

- (2)

- Energy system. New-energy policy effectiveness is highly contingent upon end-use energy structures and the system integration capacity. Therefore, grid operators and energy infrastructural companies should concurrently promote the new-energy grid integration capacity and end-use substitution capacity. The energy system should focus on enhancing distribution network flexibility, improving distribution energy grid integration conditions, and elevating the multi-energy complementary dispatch capability. This will avoid clean energy’s structural constraints, transforming the policy shock into a sustainable emission reduction.

- (3)

- City governance participant. Industrial actors and urban governance stakeholders should implement a specialized low-carbon transition strategy based on the respective energy structures and emission characteristics. High emission cities should promote clean substitution in their industrial and transport sectors as the first priority. Cities endowed with renewable energy resources should enhance the coordination between clean energy transmission and local consumption. Meanwhile, urban development processes should enhance public awareness of the energy transition’s environmental benefit, establishing a mutually reinforced emission reduction mechanism driven by policy and the market response.

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, J.; Caplliure-Giner, E.-M.; Adame-Sánchez, C. Individualized evaluation of health cost and health risks. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Qu, G.; Zhang, X.; Robert, D. The impact of public participation in environmental behavior on haze pollution and public health in China. Econ. Model. 2021, 98, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lu, Z. What is the health cost of haze pollution? Evidence from China. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, 1290–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; van Donkelaar, A.; Hammer, M.S.; McDuffie, E.E.; Burnett, R.T.; Spadaro, J.V.; Chatterjee, D.; Cohen, A.J.; Apte, J.S.; Southerland, V.A.; et al. Reversal of trends in global fine particulate matter air pollution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, Y.; Han, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, S. Synthetic natural gas as an alternative to coal for power generation in China: Life cycle analysis of haze pollution, greenhouse gas emission, and resource consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2503–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Ru, M.; Du, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shen, H.; Yun, X.; Meng, W.; Liu, J.; et al. Impacts of air pollutants from rural Chinese households under the rapid residential energy transition. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Tian, P. Polluting thy neighbor or benefiting thy neighbor: Effects of the clean energy development on haze pollution in China. Energy 2023, 268, 126685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Ma, F.; Pan, S.; Zhao, Q.; Fu, G.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Liang, Y.; Lin, M.; et al. Global energy transition revolution and the connotation and pathway of the green and intelligent energy system. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hong, X.; Wang, J. Evaluating the impact of clean energy consumption and factor allocation on China’s air pollution: A spatial econometric approach. Energy 2020, 195, 116842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F.; Sadiq, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, M.S.; Tran, T.D.; Le Thanh, T. A step toward reducing air pollution in top asian economies: The role of green energy, eco-innovation, and environmental taxes. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Cameron, M.A.; Hennessy, E.M.; Petkov, I.; Meyer, C.B.; Gambhir, T.K.; Maki, A.T.; Pfleeger, K.; Clonts, H.; McEvoy, A.L.; et al. 100% clean and renewable wind, water, and sunlight (WWS) all-sector energy roadmaps for 53 towns and cities in north America. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Adams, S. Renewable energy, nuclear energy, and environmental pollution: Accounting for political institutional quality in South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; He, L.; Shen, J. Optimization-based provincial hybrid renewable and non-renewable energy planning—A case study of shanxi, China. Energy 2017, 128, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.R.; Zaini, F.; Mathew, S.; Dagar, L.; Petra, M.I.; De Silva, L.C. Sustainable energy towards air pollution and climate change mitigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 109978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Thuy, T.D.; Kittner, N. Will the public in emerging economies support renewable energy? evidence from ho chi minh city, vietnam. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, B.; Azevedo, I.; Xia, T.; Davis, A.; Xu, J. Support for emissions reductions based on immediate and long-term pollution exposure in China. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 158, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Leitão, N.C.; Murshed, M. The carbon dioxide neutralizing effect of energy innovation on international tourism in EU-5 countries under the prism of the EKC hypothesis. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Koondhar, M.A.; Nawaz, K.; Malik, M.N.; Khan, Z.A.; Koondhar, M.A. Foreign direct investment, financial development, energy consumption, and air quality: A way for carbon neutrality in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ke, H. The new smart city programme: Evaluating the effect of the internet of energy on air quality in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O.; Klepacka, A.M.; Florkowski, W.J. Achieving renewable energy, climate, and air quality policy goals: Rural residential investment in solar panel. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koengkan, M.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Kazemzadeh, E.; Alavijeh, N.K.; De Araujo, S.J. The impact of renewable energy policies on deaths from outdoor and indoor air pollution: Empirical evidence from latin American and caribbean countries. Energy 2022, 245, 123209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, D.; Liu, Y.; Ma, H.; Hong, C.; Geng, G.; Guan, D.; He, K.; et al. Co-benefits of CO2 emission reduction from China’s clean air actions between 2013–2020. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhong, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shen, H.; Yun, X.; Smith, K.R.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; et al. Energy and air pollution benefits of household fuel policies in northern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16773–16780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Bao, R.; McFarland, M. Clean energy substitution: The effect of transitioning from coal to gas on air pollution. Energy Econ. 2022, 107, 105816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, T.; Feiock, R.; Li, F. The impacts of China’s provincial energy policies on major air pollutants: A spatial econometric analysis. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Ulgiati, S. Prevention and control policy analysis for energy-related regional pollution management in China. Appl. Energy 2016, 166, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, S.; Lei, Y.; Li, S. Interprovincial transfer of embodied energy between the Jing-Jin-Ji area and other provinces in China: A quantification using interprovincial input-output model. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, L.; Lei, Y.; Li, L.; Ge, J. Interprovincial transfer of ecological footprint among the region of Jing-Jin-Ji and other provinces in China: A quantification based on MRIO model. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Casazza, M.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liang, S.; Giannetti, B.F. Tracing the inter-regional coal flows and environmental impacts in Jing-Jin-Ji region. Ecol. Model. 2017, 364, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y. Using the fractional order method to generalize strengthening buffer operator and weakening buffer operator. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2018, 5, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Duan, H.; Bai, Y.; Meng, W. Forecasting the output of shale gas in China using an unbiased grey model and weakening buffer operator. Energy 2018, 151, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.-X. Predicting the capital intensity of the new energy industry in China using a new hybrid grey model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 126, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, X.; Yang, C. Prediction of spontaneous combustion in the coal stockpile based on an improved metabolic grey model. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 116, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lifeng, W.; Lianyi, L.; Kai, Z. Fractional hausdorff grey model and its properties. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 138, 109915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Duan, H. A new grey model for traffic flow mechanics. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 88, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.A.; Zhu, B.; Liu, S. Forecast of biofuel production and consumption in top CO2 emitting countries using a novel grey model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wu, W.-Z.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J. Forecasting annual electricity consumption in China by employing a conformable fractional grey model in opposite direction. Energy 2020, 202, 117682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Li, S.H.; Huang, R.Q.; Xu, Q. A new grey prediction model and its application to predicting landslide displacement. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 95, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wu, X.; Ding, S.; Pan, J. Application of a novel discrete grey model for forecasting natural gas consumption: A case study of jiangsu province in China. Energy 2020, 200, 117443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Li, R.; Wu, S.; Zhou, W. Application of a novel structure-adaptative grey model with adjustable time power item for nuclear energy consumption forecasting. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Li, R.; Tao, Z. A novel adaptive discrete grey model with time-varying parameters for long-term photovoltaic power generation forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 227, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Indicator | FBGM(s,t) | FGM(r,1) | BP | ARMA(1,1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chengde | MAPE (%) | 2.761 | 5.485 | 11.557 | 17.459 |

| RMSPEPR (%) | 1.652 | 5.517 | 10.431 | 12.201 | |

| RMSPEPO (%) | 4.315 | 5.888 | 10.627 | 20.344 | |

| Xingtai | MAPE (%) | 2.705 | 5.949 | 11.023 | 20.467 |

| RMSPEPR (%) | 2.121 | 6.989 | 12.469 | 17.075 | |

| RMSPEPO (%) | 3.158 | 4.200 | 7.654 | 23.000 | |

| Beijing | MAPE (%) | 2.566 | 15.300 | 12.867 | 24.386 |

| RMSPEPR (%) | 1.285 | 7.750 | 13.822 | 17.794 | |

| RMSPEPO (%) | 4.581 | 23.710 | 11.084 | 30.711 | |

| Zhangjiakou | MAPE (%) | 1.022 | 3.194 | 7.768 | 11.188 |

| RMSPEPR (%) | 2.346 | 2.307 | 5.476 | 6.608 | |

| RMSPEPO (%) | 0.174 | 4.351 | 9.824 | 15.625 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, T. Fractional Grey Breakpoint Model for Forecasting PM2.5 Under Energy Policy Shock. Fractal Fract. 2026, 10, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010024

Gu H, Wang Y, Yang T. Fractional Grey Breakpoint Model for Forecasting PM2.5 Under Energy Policy Shock. Fractal and Fractional. 2026; 10(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Haolei, Yuchen Wang, and Tongyang Yang. 2026. "Fractional Grey Breakpoint Model for Forecasting PM2.5 Under Energy Policy Shock" Fractal and Fractional 10, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010024

APA StyleGu, H., Wang, Y., & Yang, T. (2026). Fractional Grey Breakpoint Model for Forecasting PM2.5 Under Energy Policy Shock. Fractal and Fractional, 10(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract10010024