A Novel Framework for Evaluating Polarization in Online Social Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is it possible to evaluate the polarization of OSNs based on user interactions within them?

- Can there be different polarization levels for different types of interactions considered in an OSN?

- What role do influential users play in promoting or hindering polarization?

- If information about the aggressiveness of each interaction is provided, is it possible to evaluate the aggressiveness level of different groups in a polarized OSN?

- It shows that it is possible to define a framework to evaluate the polarization of users in OSNs.

- Our framework evaluates the polarization level of an OSN taking into account user interactions; it is able to evaluate the polarization level separately for each type of interactions.

- Our framework is able to evaluate the role of influential users in promoting polarization.

- Our framework is able to evaluate the aggressiveness level of different groups in a polarized OSN if the aggressiveness of each message between two users is provided.

2. Related Literature

3. Materials and Methods

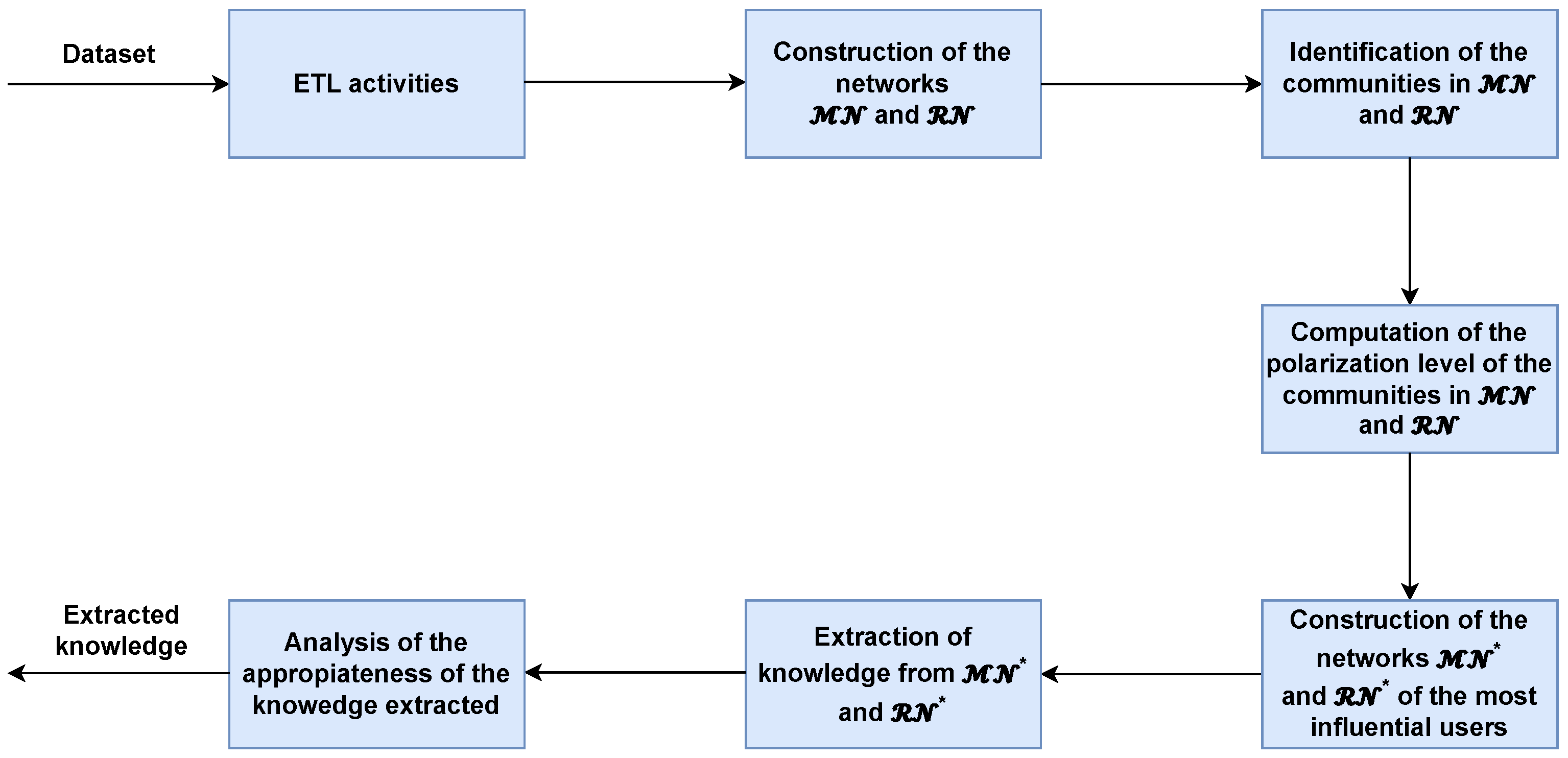

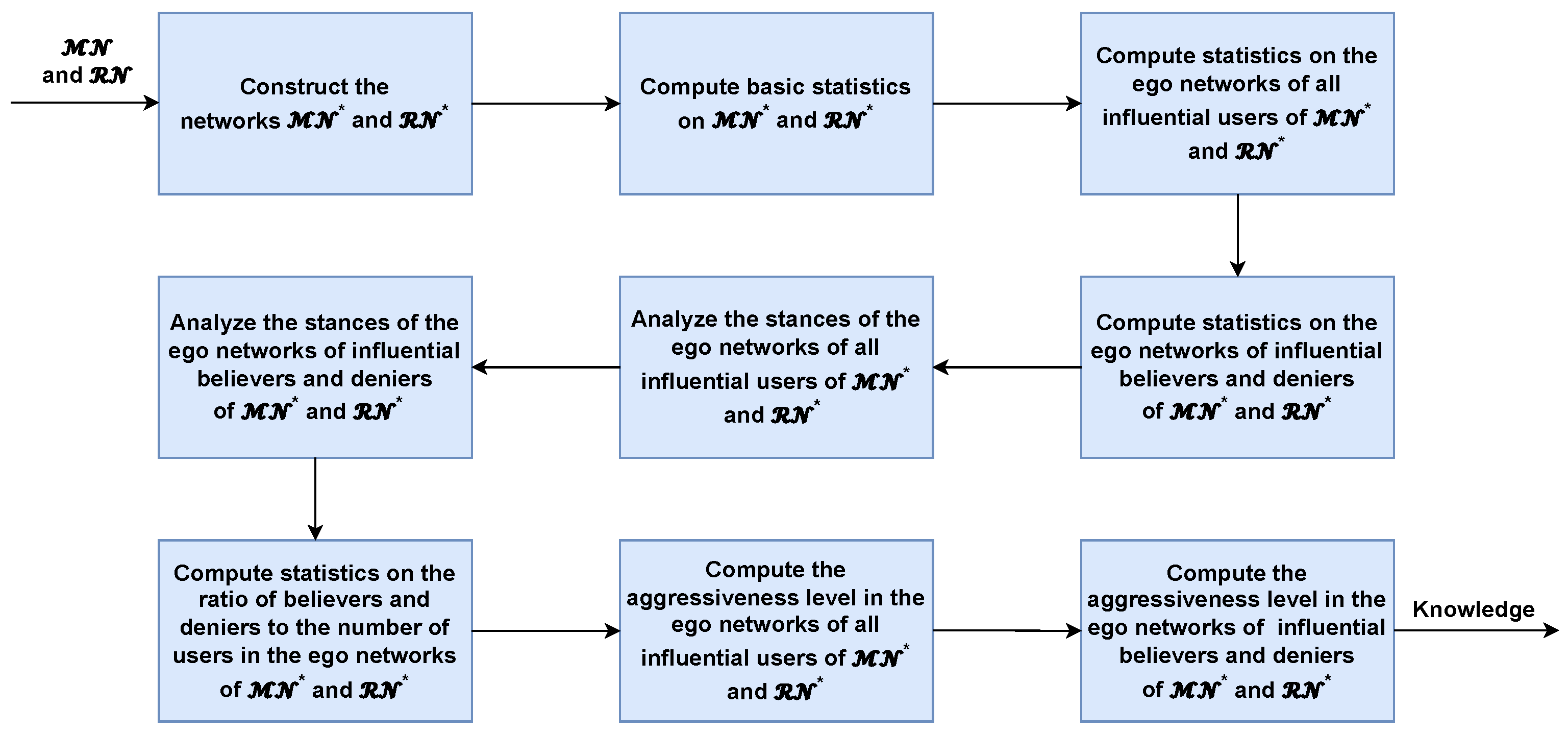

3.1. Overview of Our Framework Behavior

3.2. Data Model

- : it receives a comment and returns the user of who posted .

- : it receives a comment and returns the subset of the users of who interacted with .

- : it receives a comment and returns the stance expressed by with respect to the general topic characterizing .

- : it receives a user and returns the stance of with respect to the general topic characterizing . This stance is obtained by considering the stance most prevalent in the comments that posted on the OSN. The stance of a comment is obtained by computing . Therefore, allows us to have an insight of how a single user perceives or aligns with the general topic of reference for . Finally, it allows us to classify the users of based on their stance. For example, in the case of climate change, it allows us to classify users of into “believers” (that is, those who believe in climate change), “neutrals”, or “deniers” (that is, those who believe that climate change is a fraud).

3.3. Approaches for Polarization Analysis

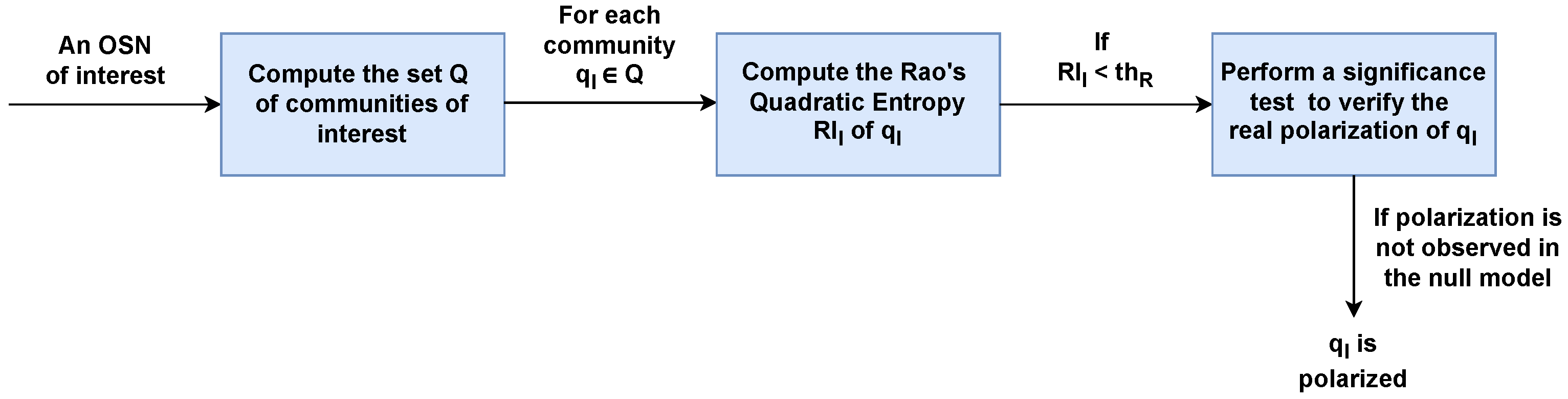

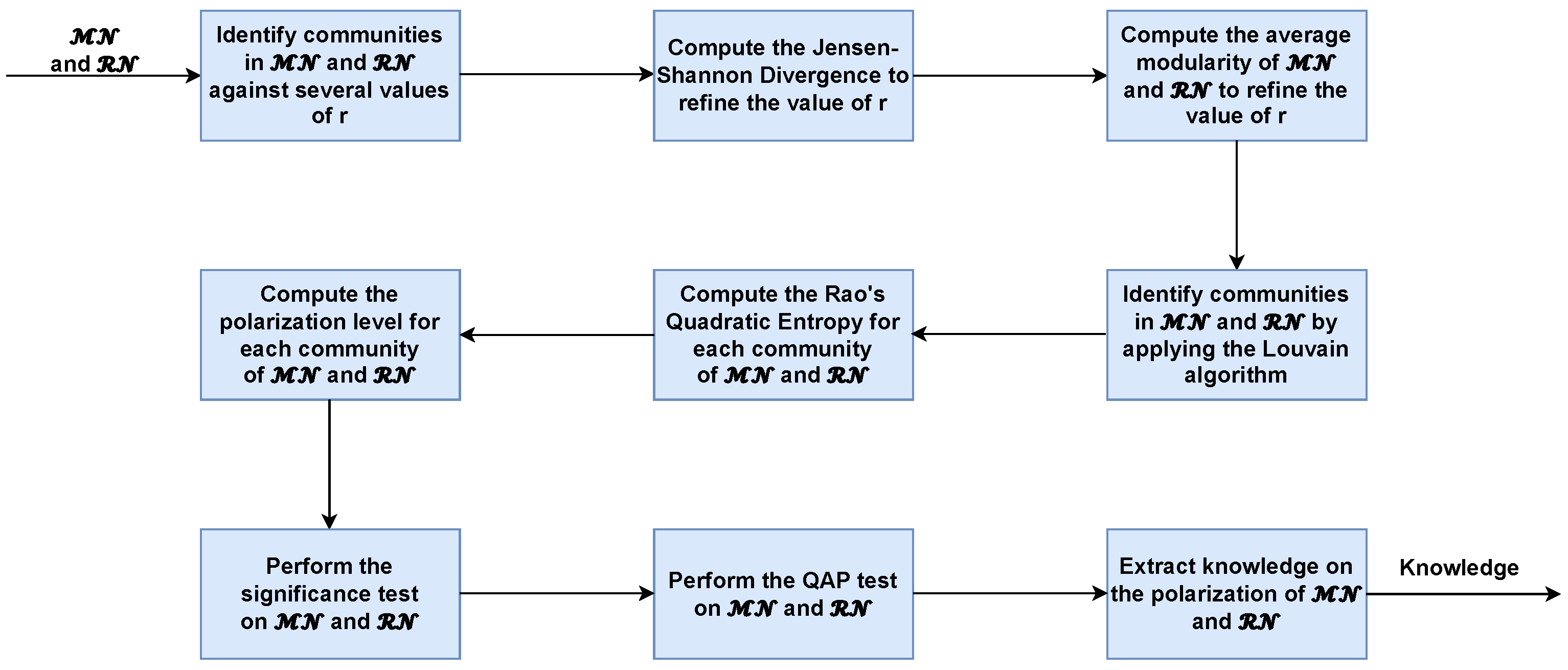

3.3.1. Approach to Evaluate Community Polarization

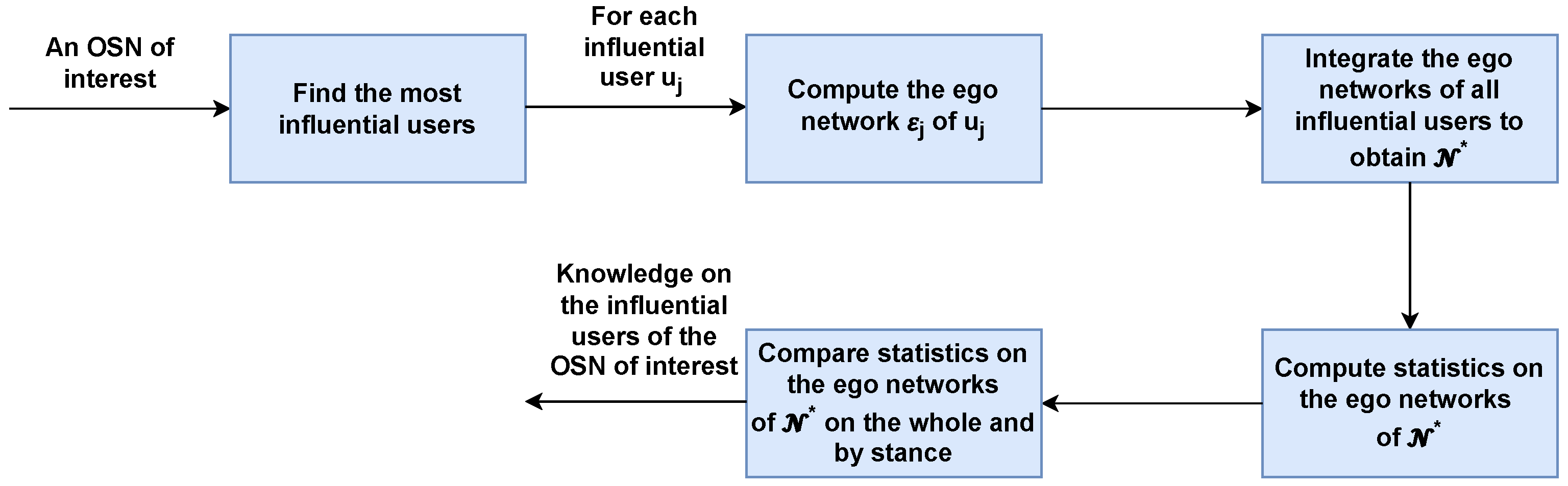

3.3.2. Approach to Investigate Influential User Polarization

- Number of nodes;

- Number of edges;

- Density;

- Average sentiments of the comments posted;

- Average number of aggressive comments;

- Average number of non-aggressive comments;

- For each stance, average number of users following it;

- Average clustering coefficient.

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Our Experimental Campaign

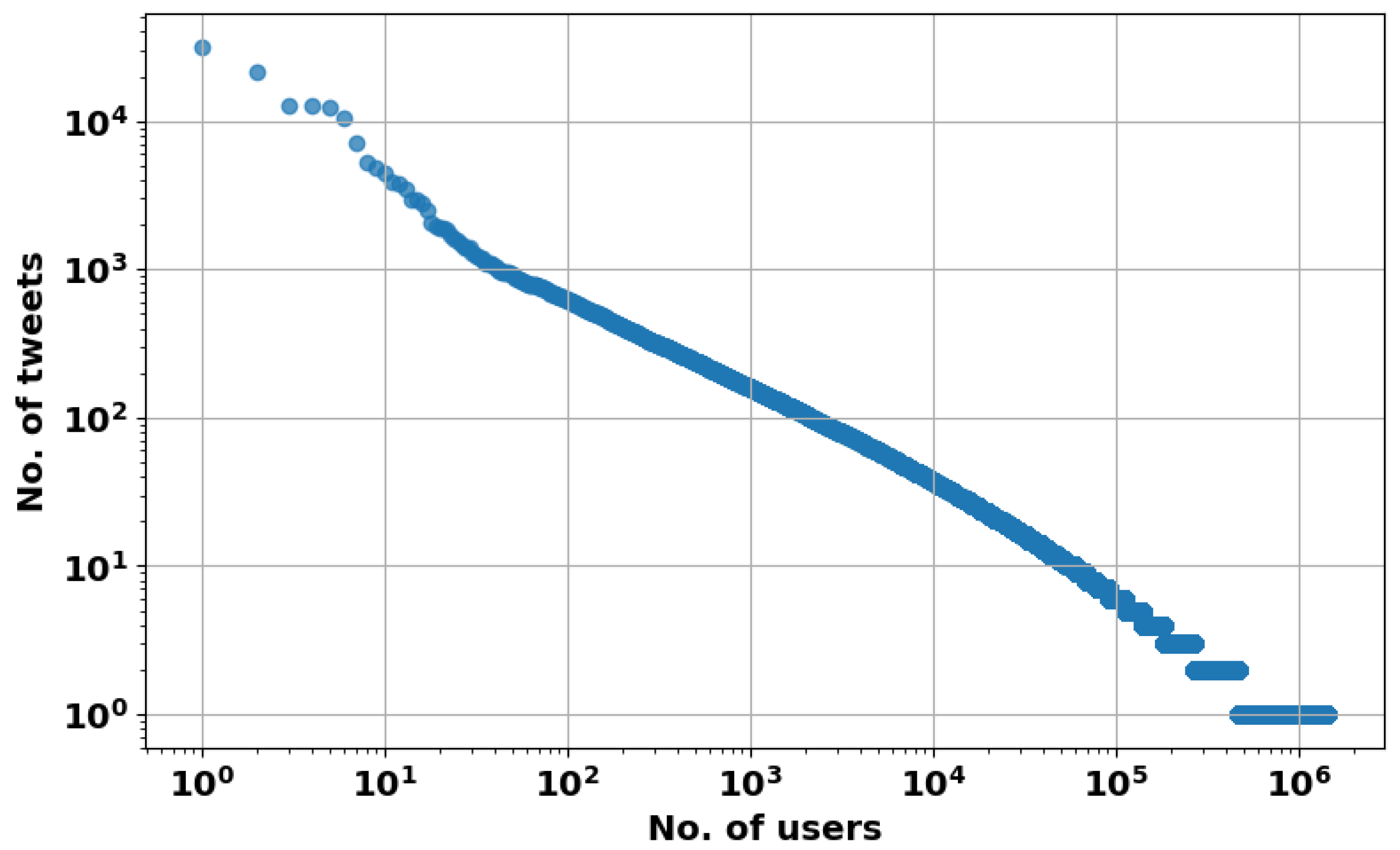

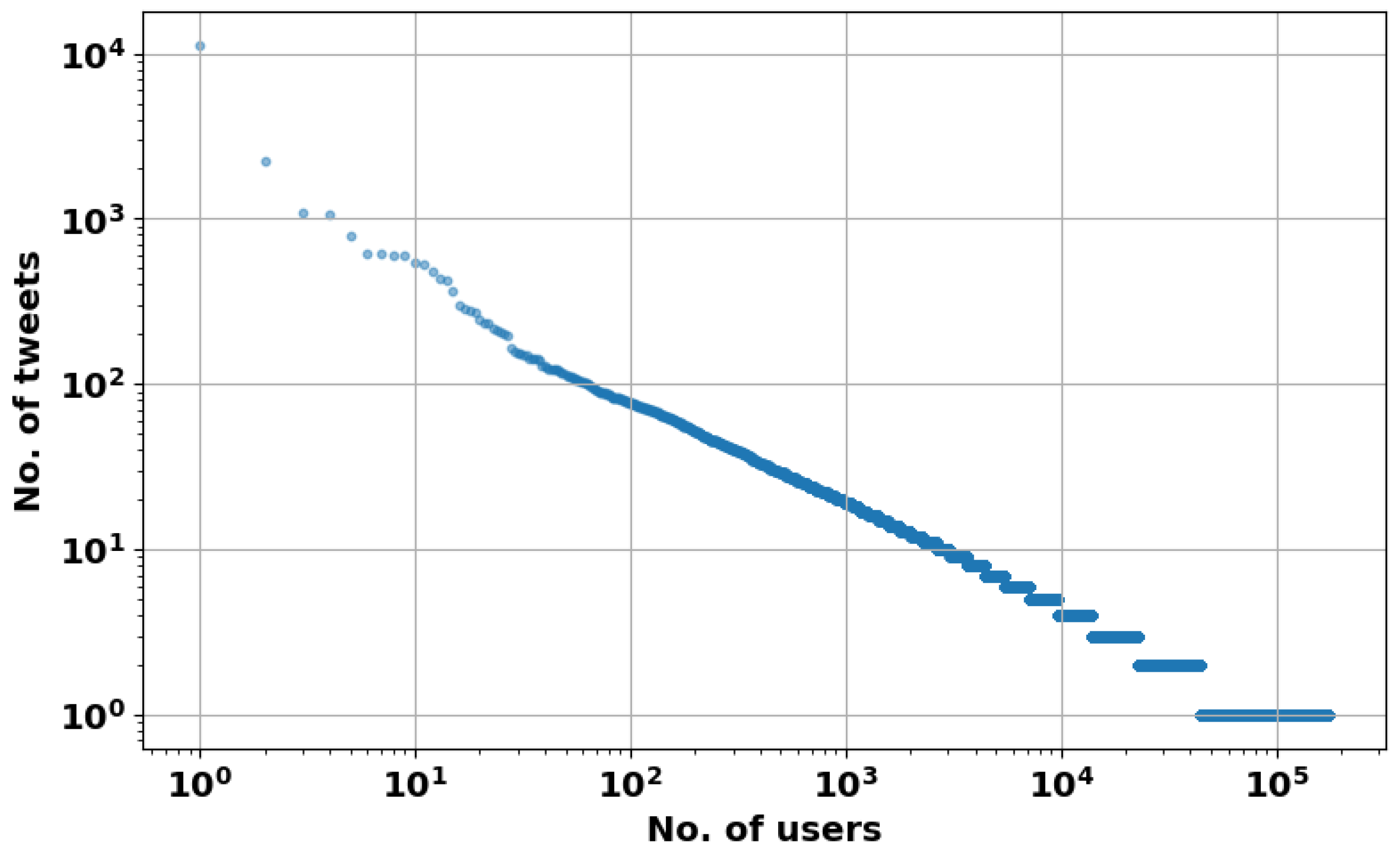

4.2. Dataset

4.2.1. Overview

4.2.2. Technical Details

4.2.3. Evaluation of the Labels of the Original Dataset

- We constructed 10 sets of tweets; each set contained 250 believer tweets and 250 denier tweets randomly selected from the reference dataset.

- We asked 10 different human experts to label the constructed sets of tweets; specifically, we assigned one set to each expert and, of course, for the tweets in the set, we did not report their stance specified in the dataset so that the expert would not be influenced by this information.

- We constructed the confusion matrix between the stances given by the experts and the ones in the dataset. This matrix is reported in Figure 10.

- We calculated the values of some quality metrics, namely:

- –

- Precision =

- –

- Recall (Sensitivity) =

- –

- Specificity =

- –

- Accuracy =

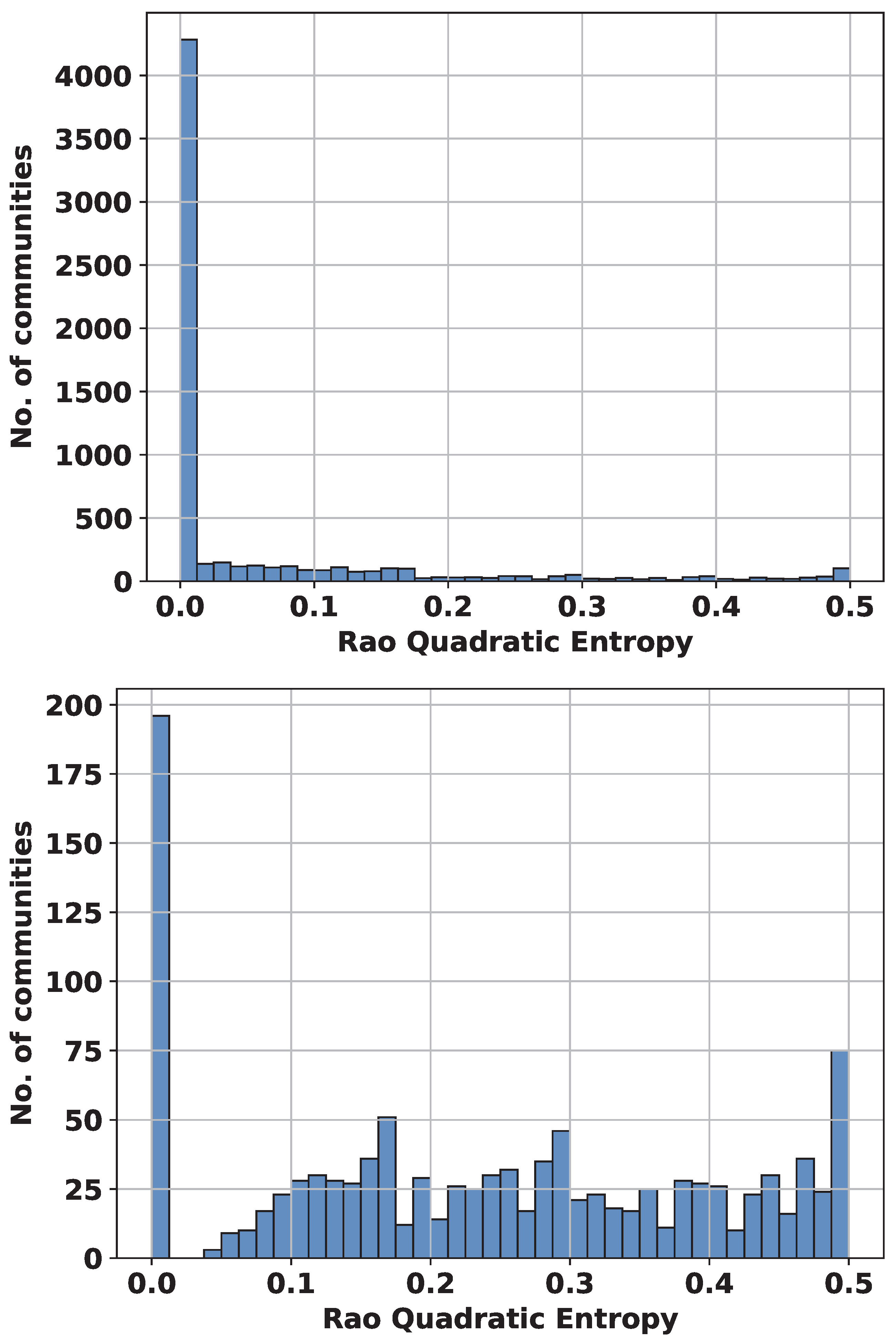

4.3. Analysis of Community Polarization

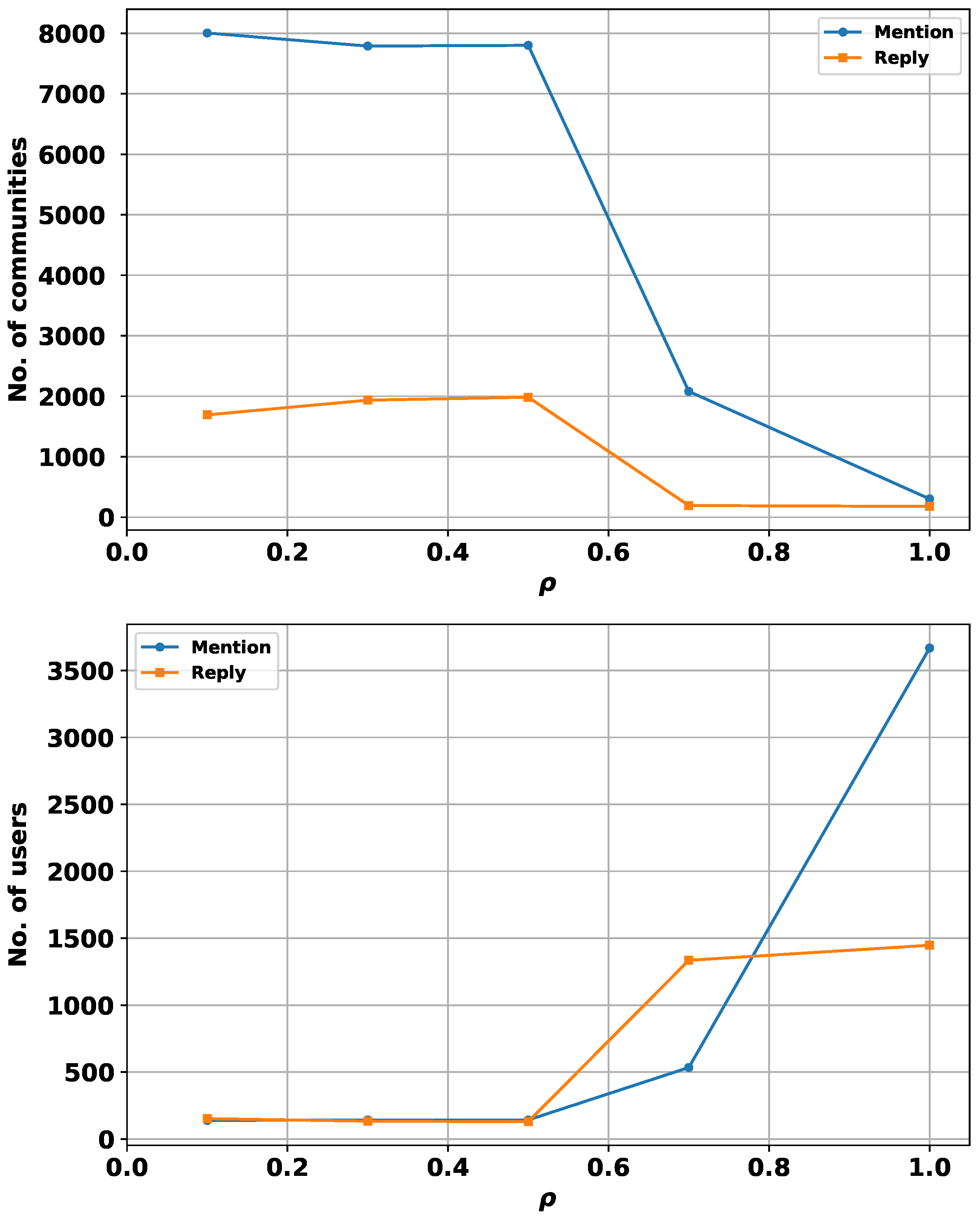

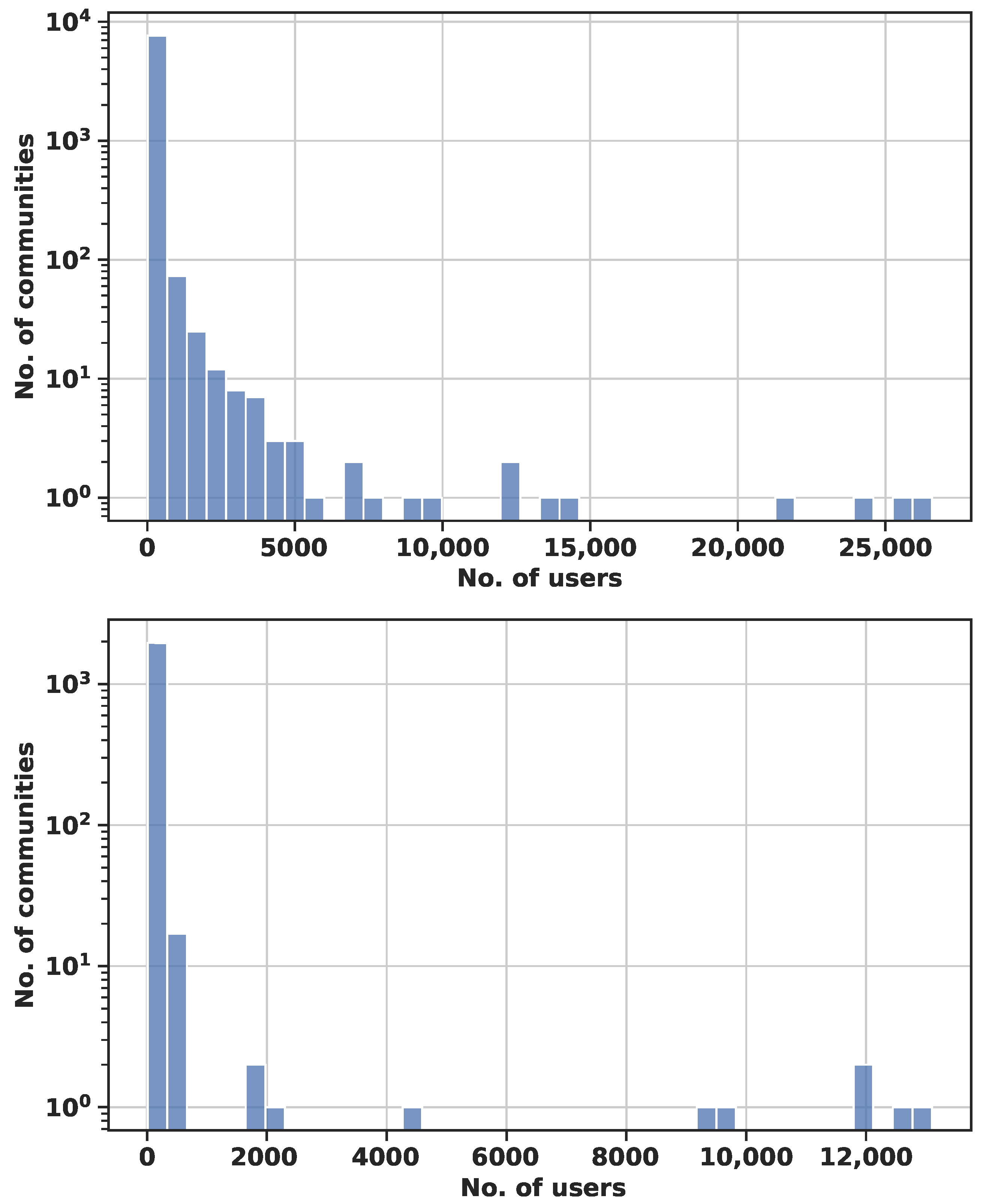

4.3.1. Identification of Communities

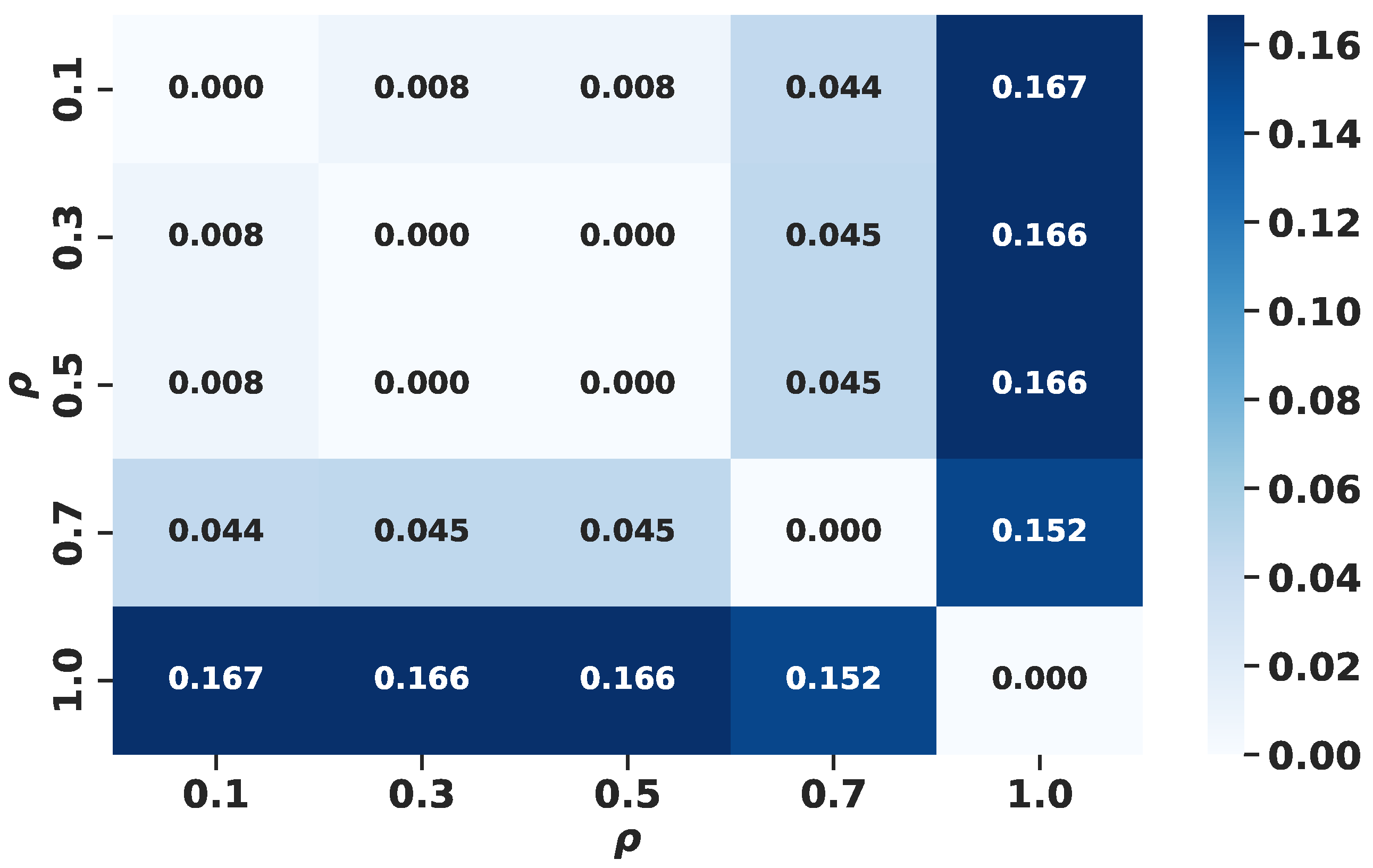

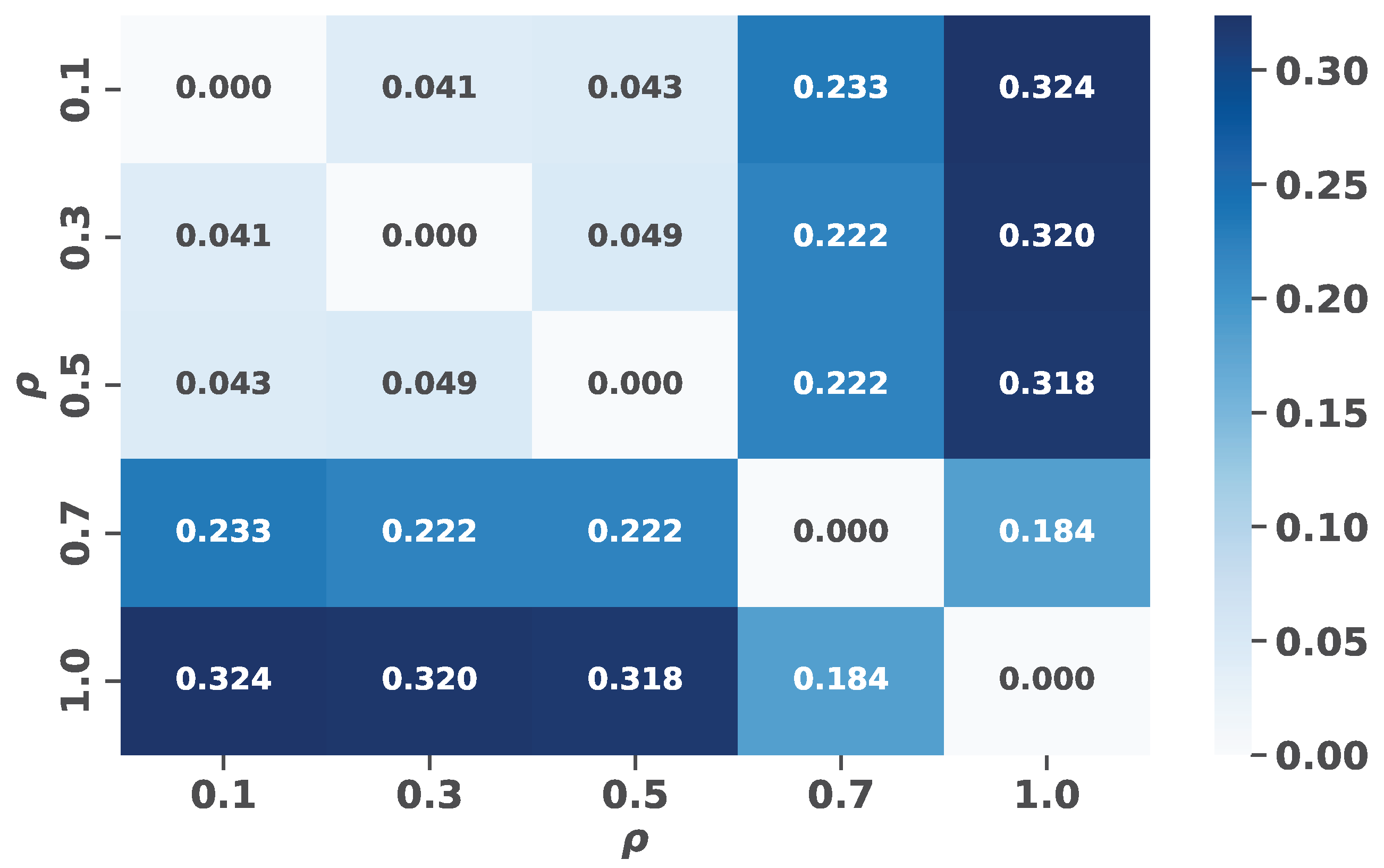

4.3.2. Analysis of Polarization Within Communities

4.4. Analysis of Influential User Polarization

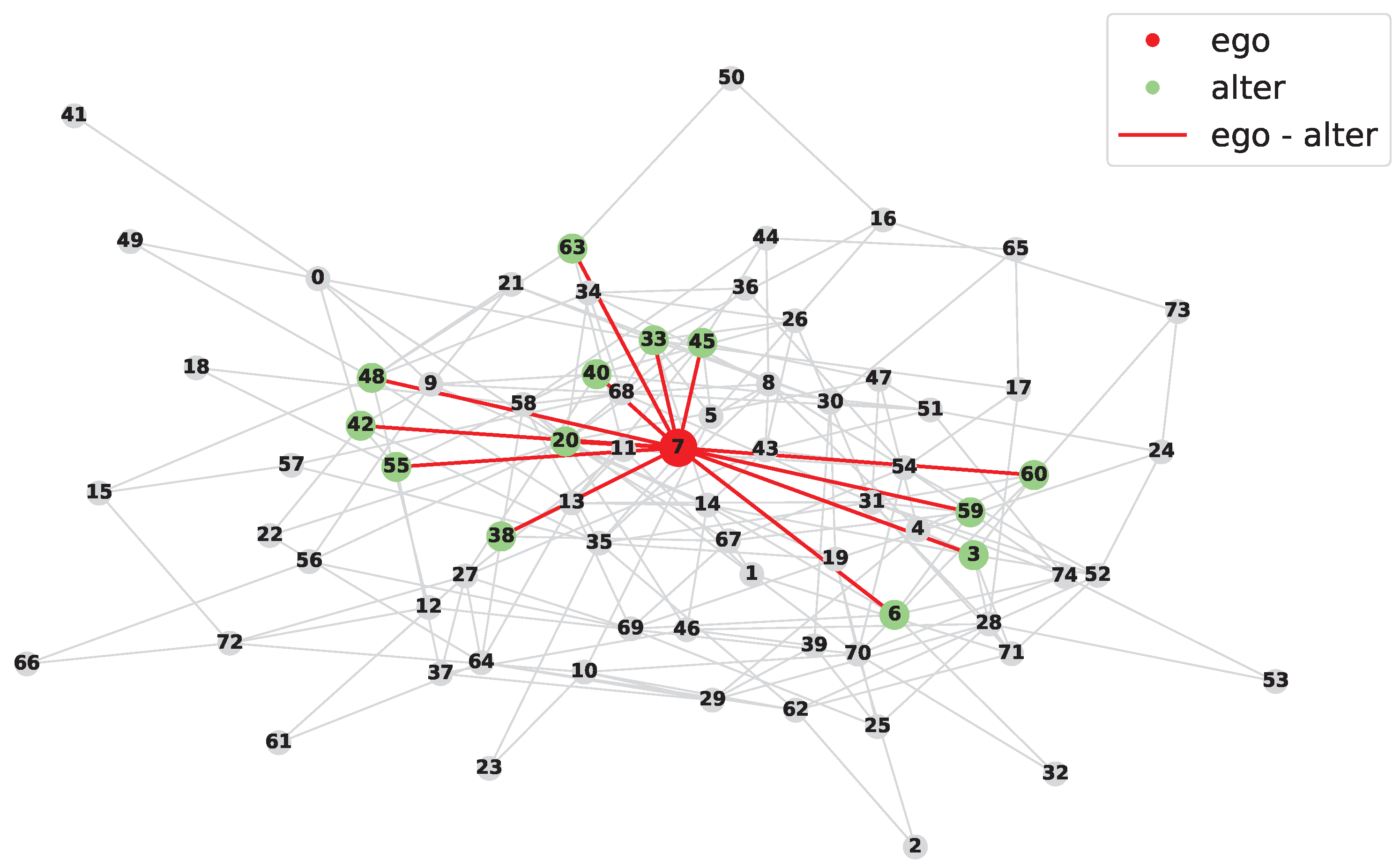

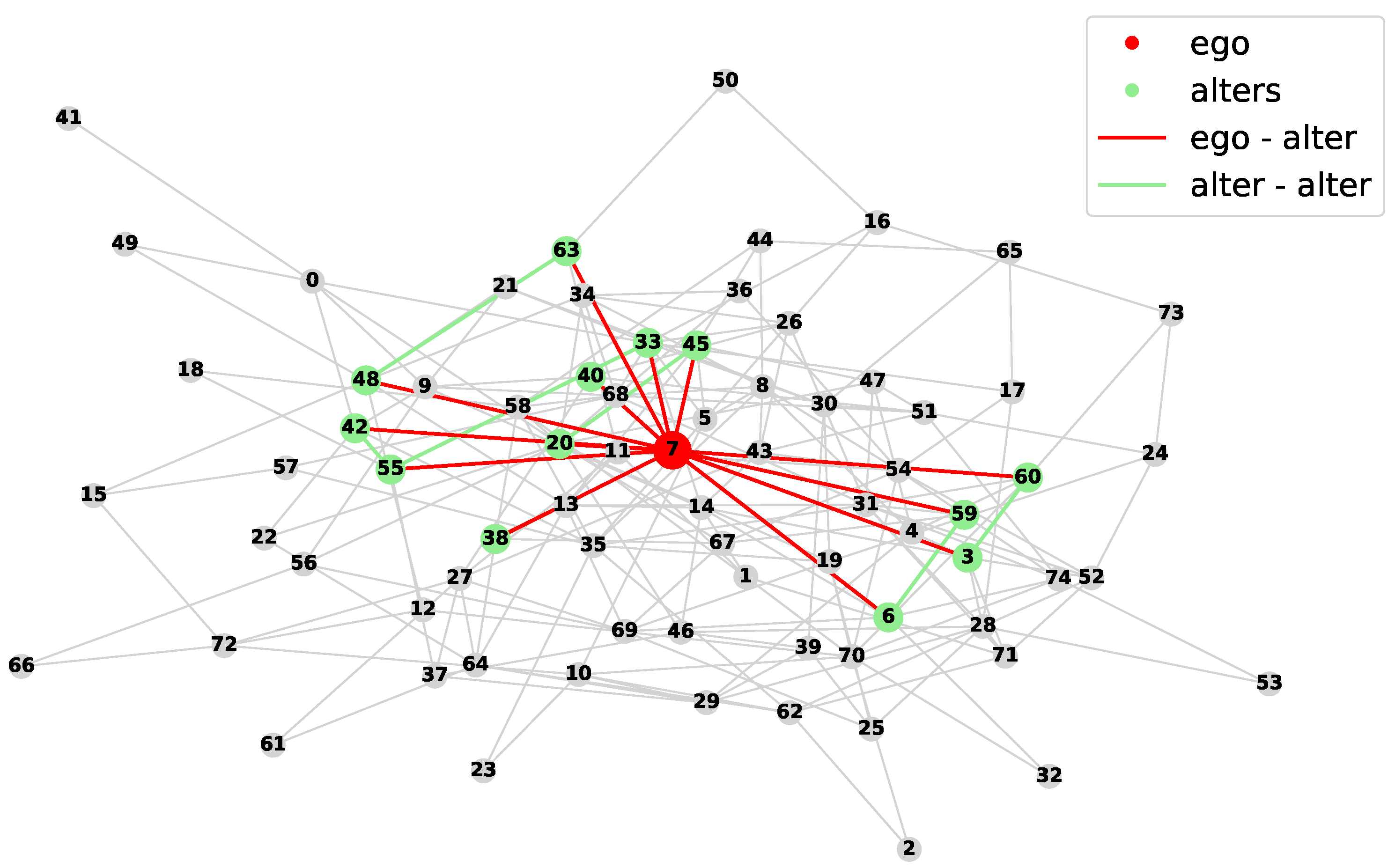

4.4.1. Analysis of the Ego Networks of All Users

4.4.2. Analysis of the Ego Networks of Believers and Deniers

4.4.3. Analysis of the Aggressiveness Level of the Tweets in the Ego Networks of Believers and Deniers

4.4.4. Analysis of the Appropriateness of the Chosen Value of T

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. A Possible Extension Toward Time Modeling

- Basic analyses, such as identifying the maximum, minimum, mean, standard deviation, trend and spikes.

- Event alignment analyses, aimed to identify temporal correlation between exogenous phenomena (such as political announcements, or extreme events) and changes in communities or corresponding polarization indices within the reference OSN.

- Early warning analyses, which identify the initial signs preceding certain phenomena, such as community splitting, echo chamber consolidation, the reduction, or even disappearance, of the polarization level of a community, etc.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baym, N.K. Personal Connections in the Digital Age; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifazi, G.; Corradini, E.; Marchetti, M.; Sciarretta, L.; Ursino, D.; Virgili, L. A Space-Time Framework for Sentiment Scope Analysis in Social Media. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Weaver, D. On-line democracy or on-line demagoguery? Public opinion “polls” on the Internet. Harv. Int. J. Press. 1997, 2, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Tsai, F. A Systematic Review of Internet Public Opinion Manipulation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 3159–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qais, A. The Internet and Its Impact on Free Speech. Indian J. Law Leg. Res. 2023, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, J. Risky and cautious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 4, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Breve, B.; Cirillo, S.; Corradini, E.; Virgili, L. Investigating the COVID-19 vaccine discussions on Twitter through a multilayer network-based approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casañ, R.; García-Vidal, E.; Grimaldi, D.; Carrasco-Farré, C.; Vaquer-Estalrich, F.; Vila-Francés, J. Online polarization and cross-fertilization in multi-cleavage societies: The case of Spain. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2022, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantini, R.; Marozzo, F.; Talia, D.; Trunfio, P. Analyzing political polarization on social media by deleting bot spamming. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P.; Merton, R. Friendship as a social process: A substantive and methodological analysis. Freedom Control Mod. Soc. 1954, 18, 18–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; Pelicon, A.; Mozetič, I.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Novak, P.; Zollo, F. Dynamics of online hate and misinformation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjolras, B.; Salway, A. Homophily and polarization on political twitter during the 2017 Norwegian election. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2022, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, A.; Singh, S. Investigating political polarization in India through the lens of Twitter. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2022, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaroussi, R.; Noufe, S.C.; Dupin, F.; Vandanjon, P.O. Polarity of Yelp Reviews: A BERT–LSTM Comparative Study. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäs, M.; Flache, A. Differentiation without distancing. Explaining bi-polarization of opinions without negative influence. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtte, M. School type and academic culture: Evidence for the differentiation–polarization theory. J. Curric. Stud. 2006, 38, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Jiang, T.; Jin, C.; Li, Q.; Jin, X. Endogenetic structure of filter bubble in social networks. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitra, U.; Musco, C. Analyzing the impact of filter bubbles on social network polarization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM’20), Houston, TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; pp. 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.L.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A.; Betsch, C.; Quattrociocchi, W. Polarization of the vaccination debate on Facebook. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3606–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moernaut, R.; Mast, J.; Temmerman, M.; Broersma, M. Hot weather, hot topic. Polarization and sceptical framing in the climate debate on Twitter. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2022, 25, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garimella, K.; Morales, G.D.F.; Gionis, A.; Mathioudakis, M. Political discourse on social media: Echo chambers, gatekeepers, and the price of bipartisanship. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference (WWW’18), Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 913–922. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, M.; Ratkiewicz, J.; Francisco, M.; Gonçalves, B.; Menczer, F.; Flammini, A. Political polarization on Twitter. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM’11), Barcelona, Spain, 17–21 July 2011; Volume 5, pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Scaglione, A.; Swam, A.; Zhao, Q. Consensus, polarization and clustering of opinions in social networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.; Lorenz-Spreen, P.; Sokolov, I.; Starnini, M. Modeling echo chambers and polarization dynamics in social networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 048301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Singh, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Maity, M. Polarization and social media: A systematic review and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibagheri, A.; Sukthankar, G. Political Polarization Over Global Warming: Analyzing Twitter Data on Climate Change; Academy of Science and Engineering (ASE): Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Overgaard, C.; Woolley, S. How Social Media Platforms Can Reduce Polarization; Technical report; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Wang, D.; Ma, F. Analysis of individual characteristics influencing user polarization in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Uyheng, J.; Carley, K. Affective polarization in online climate change discourse on twitter. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM ’20), IEEE, Virtual Event, 7–10 December 2020; pp. 443–447. [Google Scholar]

- Musco, C.; Musco, C.; Tsourakakis, C.E. Minimizing polarization and disagreement in social networks. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web conference (WWW’18), Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Lijffijt, J.; Bie, T.D. Quantifying and minimizing risk of conflict in social networks. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD’18), London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 1197–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Effrosynidis, D.; Karasakalidis, A.; Sylaios, G.; Arampatzis, A. The climate change Twitter dataset. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.; Guess, A.; Barberá, P.; Vaccari, C.; Siegel, A.; Sanovich, S.; Stukal, D.; Nyhan, B. Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, M.; Galeazzi, A.; Torricelli, M.; Marco, N.D.; Larosa, F.; Sas, M.; Mekacher, A.; Pearce, W.; Zollo, F.; Quattrociocchi, W. Growing polarization around climate change on social media. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakos, A.; Terzi, E.; Tsaparas, P. Measuring and moderating opinion polarization in social networks. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2017, 31, 1480–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, O.; Smith, R.; Vivo, P.; Livan, G. A minimalistic model of bias, polarization and misinformation in social networks. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Roy, J. Investigating political polarization on Twitter: A Canadian perspective. Policy Internet 2014, 6, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Shin, J.; Hong, A. Does social media use really make people politically polarized? Direct and indirect effects of social media use on political polarization in South Korea. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaufort, M. Digital media, political polarization and challenges to democracy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garimella, V.; Weber, I. A long-term analysis of polarization on Twitter. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM’17), Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–18 May 2017; Volume 11, pp. 528–531. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Alostad, H.; Davulcu, H. Quantifying Variations in Controversial Discussions within Kuwaiti Social Networks. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberá, P. Social media, echo chambers, and political polarization. Soc. Media Democr. State Field Prospect. Reform 2020, 34, 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gillani, N.; Yuan, A.; Saveski, M.; Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D. Me, my echo chamber, and I: Introspection on social media polarization. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference (WWW’18), Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 823–831. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, T.; Miller, S.; Roberts, J. Bots and online climate discourses: Twitter discourse on President Trump’s announcement of US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, M.; Painter, J.; Yasseri, T.; Lorimer, J. Controversy around climate change reports: A case study of Twitter responses to the 2019 IPCC report on land. Clim. Change 2021, 167, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S.; Lörcher, I.; Brüggemann, M. Scientific networks on Twitter: Analyzing scientists’ interactions in the climate change debate. Public Underst. Sci. 2019, 28, 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, W.; Niederer, S.; Özkula, S.M.; Querubín, N.S. The social media life of climate change: Platforms, publics, and future imaginaries. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2019, 10, e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakieh, Y. Shaping climate change discourse: The nexus between political media landscape and recommendation systems in social networks. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2023, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Babcock, M.; Carley, K.; Sicker, D. Polarizing tweets on climate change. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction and Behavior Representation in Modeling and Simulation (SBP-BRiMS’20), Washington, DC, USA, 18–21 October 2020; Springer: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Treen, K.; Williams, H.; O’Neill, S.; Coan, T.G. Discussion of Climate Change on Reddit: Polarized Discourse or Deliberative Debate? Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Morales, G.D.F.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, R.; Nobre, J.; Becker, K. A multi-dimensional framework to analyze group behavior based on political polarization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 233, 120768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C. Diversity and dissimilarity coefficients: A unified approach. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1982, 21, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harenberg, S.; Bello, G.; Gjeltema, L.; Ranshous, S.; Harlalka, J.; Seay, R.; Padmanabhan, K.; Samatova, N. Community detection in large-scale networks: A survey and empirical evaluation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2014, 6, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.; Guillaume, J.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauset, A.; Newman, M.; Moore, C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys. Rev. Part E 2004, 70, 066111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8577–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, P.; Bruce, A.; Gedeck, P. Practical Statistics for Data Scientist, Second Edition; O’Reilly: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wandelt, S.; Sun, X.; Menasalvas, E.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Zanin, M. On the use of random graphs as null model of large connected networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 119, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, V.; Zhou, Y. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test: Overview. In Wiley Statsref: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifazi, G.; Cauteruccio, F.; Corradini, E.; Marchetti, M.; Pierini, A.; Terracina, G.; Ursino, D.; Virgili, L. An approach to detect backbones of information diffusers among different communities of a social platform. Data Knowl. Eng. 2022, 140, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestel, R. Graph Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clauset, A.; Shalizi, C.; Newman, M. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Rev. 2009, 51, 661–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jr, F.M. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1951, 46, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, E.; Weitkamp, E.; Webb, P. The visual vaccine debate on Twitter: A social network analysis. Media Commun. 2020, 8, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauteruccio, F.; Corradini, E.; Marchetti, M.; Ursino, D.; Virgili, L. A Framework for Investigating Discording Communities on Social Platforms. Electronics 2025, 14, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yao, X.; Guo, C.; Wei, X. Can we forecast presidential election using twitter data? an integrative modelling approach. Ann. GIS 2021, 27, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, L.; Schultz, J. Quadratic assignment as a general data analysis strategy. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1976, 29, 190–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, M.L.; Pardo, J.A.; Pardo, L.; Pardo, M.D.C. The jensen-shannon divergence. J. Frankl. Inst. 1997, 334, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zade, H.; Williams, S.; Tran, T.T.; Smith, C.; Venkatagiri, S.; Hsieh, G.; Starbird, K. To reply or to quote: Comparing conversational framing strategies on Twitter. ACM J. Comput. Sustain. Soc. 2024, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buder, J.; Rabl, L.; Feiks, M.; Badermann, M.; Zurstiege, G. Does negatively toned language use on social media lead to attitude polarization? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 116, 106663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetovat, M.; Kouznetsov, A. Social Network Analysis for Startups: Finding Connections on the Social Web; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfowicz, M.; Weisburd, D.; Hasisi, B. Examining the interactive effects of the filter bubble and the echo chamber on radicalization. J. Exp. Criminol. 2023, 19, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce-García, S.; Díaz-Campo, J.; Cambronero-Saiz, B. Online hate speech and emotions on Twitter: A case study of Greta Thunberg at the UN Climate Change Conference COP25 in 2019. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2023, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C. Does the internet make the world worse? Depression, aggression and polarization in the social media age. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2021, 41, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinus, F.; Minici, M.; Monti, C.; Bonchi, F. The effect of people recommenders on echo chambers and polarization. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM’22), Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 June 2022; Volume 16, pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| tweet_id | It is the unique identifier of the tweet. |

| created_at | It is the timestamp when the tweet was posted. |

| sentiment | It is the sentiment of the tweet. Its value varies in the real interval [−1,1]. A value less (resp., greater) than 0 indicates negative (resp., positive) sentiment. |

| stance | It is the stance of the tweet according to the climate change debate. If the tweet is in favor of the anthropogenic origin of climate change, it is labeled as believer. Conversely, if it is against that origin, it is labeled as a denier. Finally, if it maintains a neutral position on this issue, it is labeled as neutral. |

| aggressiveness | It is the tone and demeanor of the tweet. If the inherent language is confrontational, the tweet is classified as aggressive; otherwise, it is classified as non-aggressive. |

| topic | It is the topic discussed in the tweet. |

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| tweet_id | It is the unique identifier of the tweet. |

| user_id | It is the unique identifier of the author of the tweet. |

| in_reply_to_user_id | If the tweet is a reply to another tweet, it is the identifier of the recipient of the reply. |

| user_mentions_id | If the tweet mentions another user, it is the identifier of the user mentioned. |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of users | 1,435,545 |

| Number of tweets | 4,190,961 |

| Number of mentions | 3,130,909 |

| Number of replies | 454,073 |

| Minimum number of tweets per user | 1 |

| Average number of tweets per user | 2.92 |

| Maximum number of tweets per user | 31,762 |

| Number of believer tweets | 3,314,625 |

| Number of denier tweets | 254,528 |

| Number of neutral tweets | 622,198 |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of users | 1,329,329 |

| Number of tweets | 3,569,153 |

| Number of mentions | 2,666,379 |

| Number of replies | 386,702 |

| Minimum number of tweets per user | 1 |

| Average number of tweets per user | 2.86 |

| Maximum number of tweets per user | 31,762 |

| Number of believer tweets | 3,314,625 |

| Number of denier tweets | 254,528 |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of users | 1,329,307 |

| Number of tweets | 3,569,089 |

| Number of mentions | 2,666,332 |

| Number of replies | 386,696 |

| Minimum number of tweets per user | 1 |

| Average number of tweets per user | 2.86 |

| Maximum number of tweets per user | 31,762 |

| Number of believer tweets | 3,314,561 |

| Percentage of believer tweets | 92.87% |

| Number of denier tweets | 254,464 |

| Percentage of denier tweets | 7.13% |

| Number of believer users | 1,233,779 |

| Percentage of believer users | 92.81% |

| Number of denier users | 95,528 |

| Percentage of denier users | 7.19% |

| Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 1,255,244 | 293,226 |

| Number of edges | 2,266,566 | 308,471 |

| Density | 2.88 | 7.18 |

| Minimum degree of a node | 1 | 1 |

| Average degree of a node | 3.61 | 2.10 |

| Maximum degree of a node | 41,012 | 9434 |

| 0.5085 | 0.6800 | |

| 0.5188 | 0.8076 | |

| 0.5836 | 0.8423 |

| Statistic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of communities | 7801 | 7585 | 1984 | 3214 |

| Average size of communities | 142.47 | 93.12 | 129.87 | 41.84 |

| User Stance | Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Believers | 94.06% | 0.078 | 62.95% | 0.044 |

| Deniers | 5.94% | 0.014 | 13.60% | 0.014 |

| User Stance | Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Believers | 84.09% | 0.011 | 93.88% | 0.012 |

| Deniers | 15.91% | 0.003 | 6.12% | 0.005 |

| 12.91 | 15.84 | 4.63 |

| Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 49,894 | 35,828 |

| Number of edges | 103,875 | 53,894 |

| Density | 8346·10−5 | 8.397·10−5 |

| Statistic | Mean in | Variance in | Mean in | Variance in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 45.324 | 189.943 | 22.467 | 174.321 |

| Number of edges | 153.125 | 443.454 | 26.235 | 182.458 |

| Density | 0.262 | 0.231 | 0.228 | 0.172 |

| Average sentiment | 0.013 | 0.196 | −0.070 | 0.167 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 30.965 | 42.176 | 19.005 | 46.443 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 104.765 | 171.375 | 61.496 | 235.485 |

| Average number of believers | 12.374 | 25.358 | 3.932 | 6.365 |

| Average number of deniers | 5.521 | 15.284 | 1.792 | 4.473 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.315 | 0.228 | 0.109 | 0.159 |

| Statistic | Mean in | Variance in | Mean in | Variance in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 28.634 | 321.127 | 13.834 | 302.189 |

| Number of edges | 117.589 | 685.323 | 15.976 | 308.143 |

| Density | 0.68 | 0.168 | 0.053 | 0.170 |

| Average sentiment | 0.022 | 0.134 | −0.014 | 0.139 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 17.298 | 42.843 | 7.101 | 38.224 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 58.234 | 155.743 | 20.698 | 168.342 |

| Average number of believers | 10.598 | 36.265 | 2.732 | 8.178 |

| Average number of deniers | 1.210 | 13.321 | 0.741 | 6.548 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.481 | 0.178 | 0.041 | 0.141 |

| Statistic | Mean in | Variance in | Mean in | Variance in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 9.352 | 33.634 | 4.701 | 16.575 |

| Number of edges | 23.82 | 211.789 | 5.124 | 24.212 |

| Density | 0.066 | 0.168 | 0.073 | 0.156 |

| Average sentiment | −0.031 | 0.115 | −0.036 | 0.147 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 7.198 | 32.856 | 4.243 | 37.097 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 22.098 | 149.043 | 13.498 | 182.201 |

| Average number of believers | 1.187 | 3.765 | 0.749 | 2.597 |

| Average number of deniers | 3.069 | 19.401 | 0.725 | 4.111 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.202 | 0.224 | 0.033 | 0.098 |

| Network | ||

|---|---|---|

| ego networks of believers | ||

| 0.361 | 0.041 | |

| 0.201 | 0.054 | |

| ego networks of deniers | ||

| 0.124 | 0.318 | |

| 0.161 | 0.156 |

| Network | in | in |

|---|---|---|

| Ego networks of believers | 0.298 | 0.343 |

| Ego networks of deniers | 0.326 | 0.314 |

| Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|

| T = 1500 | ||

| Number of nodes | 49,894 | 35,828 |

| Number of edges | 103,875 | 53,894 |

| Density | 8346·10−5 | 8.397·10−5 |

| T = 3000 | ||

| Number of nodes | 111,675 | 74,734 |

| Number of edges | 412,923 | 238,195 |

| Density | 6622·10−5 | 8.530·10−5 |

| T = 5000 | ||

| Number of nodes | 184,486 | 123,934 |

| Number of edges | 723,538 | 521,584 |

| Density | 4252·10−5 | 6.792·10−5 |

| T = 10,000 | ||

| Number of nodes | 326,936 | 206,376 |

| Number of edges | 1,325,734 | 984,038 |

| Density | 2.482·10−5 | 4621·10−5 |

| T = 20,000 | ||

| Number of nodes | 584,194 | 398,240 |

| Number of edges | 2,421,947 | 1,723,484 |

| Density | 1.419·10−5 | 2.173·10−5 |

| textbfStatistic | Mean in | Variance in | Mean in | Variance in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = 1000 | ||||

| Number of nodes | 44.324 | 189.943 | 22.467 | 174.321 |

| Number of edges | 153.125 | 443.454 | 26.235 | 182.458 |

| Density | 0.262 | 0.231 | 0.228 | 0.172 |

| Average sentiment | 0.013 | 0.196 | −0.070 | 0.167 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 30.965 | 42.176 | 19.005 | 46.443 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 104.765 | 171.375 | 61.496 | 235.485 |

| Average number of believers | 12.374 | 25.358 | 3.932 | 6.365 |

| Average number of deniers | 5.521 | 15.284 | 1.792 | 4.473 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.315 | 0.228 | 0.109 | 0.159 |

| T = 3000 | ||||

| Number of nodes | 43.834 | 201.276 | 21.985 | 190.321 |

| Number of edges | 152.236 | 446.296 | 25.756 | 188.539 |

| Density | 0.251 | 0.281 | 0.226 | 0.192 |

| Average sentiment | 0.014 | 0.220 | −0.068 | 0.194 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 29.243 | 48.155 | 20.432 | 54.224 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 103.265 | 182.238 | 60.947 | 236.345 |

| Average number of believers | 11.845 | 28.275 | 4.184 | 8.998 |

| Average number of deniers | 5.025 | 19.995 | 1.653 | 6.007 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.314 | 0.258 | 0.111 | 0.189 |

| T = 5000 | ||||

| Number of nodes | 44.538 | 205.639 | 22.364 | 193.735 |

| Number of edges | 153.395 | 463.037 | 26.007 | 192.343 |

| Density | 0.241 | 0.281 | 0.227 | 0.192 |

| Average sentiment | 0.015 | 0.220 | −0.065 | 0.198 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 30.284 | 52.690 | 19.003 | 57.012 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 104.103 | 193.107 | 61.496 | 243.369 |

| Average number of believers | 12.048 | 32.395 | 4.385 | 10.952 |

| Average number of deniers | 5.194 | 22.952 | 1.229 | 8.285 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.294 | 0.328 | 0.121 | 0.219 |

| T = 10,000 | ||||

| Number of nodes | 44.749 | 208.265 | 22.740 | 198.101 |

| Number of edges | 151.374 | 673.285 | 23.295 | 196.375 |

| Density | 0.251 | 0.281 | 0.236 | 0.192 |

| Average sentiment | 0.013 | 0.245 | −0.070 | 0.221 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 28.264 | 55.386 | 19.409 | 59.495 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 104.395 | 198.285 | 59.090 | 247.308 |

| Average number of believers | 10.908 | 34.006 | 4.506 | 12.375 |

| Average number of deniers | 5.432 | 25.658 | 1.258 | 10.497 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.304 | 0.321 | 0.121 | 0.234 |

| T = 20,000 | ||||

| Number of nodes | 43.638 | 214.259 | 23.047 | 201.285 |

| Number of edges | 150.285 | 679.222 | 24.465 | 202.089 |

| Density | 0.241 | 0.321 | 0.226 | 0.221 |

| Average sentiment | 0.014 | 0.264 | −0.069 | 0.234 |

| Average number of aggressive tweets | 27.285 | 58.887 | 20.994 | 61.438 |

| Average number of non-aggressive tweets | 103.295 | 210.480 | 60.184 | 253.158 |

| Average number of believers | 11.205 | 36.375 | 5.298 | 13.002 |

| Average number of deniers | 4.859 | 27.320 | 1.264 | 12.376 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.294 | 0.367 | 0.119 | 0.289 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buratti, C.; Marchetti, M.; Parlapiano, F.; Ursino, D.; Virgili, L. A Novel Framework for Evaluating Polarization in Online Social Networks. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9090227

Buratti C, Marchetti M, Parlapiano F, Ursino D, Virgili L. A Novel Framework for Evaluating Polarization in Online Social Networks. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2025; 9(9):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9090227

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuratti, Christopher, Michele Marchetti, Federica Parlapiano, Domenico Ursino, and Luca Virgili. 2025. "A Novel Framework for Evaluating Polarization in Online Social Networks" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 9, no. 9: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9090227

APA StyleBuratti, C., Marchetti, M., Parlapiano, F., Ursino, D., & Virgili, L. (2025). A Novel Framework for Evaluating Polarization in Online Social Networks. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 9(9), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc9090227