1. Introduction

Crime poses a significant threat to social stability and public safety. According to statistics, more than seven individuals lose their lives to violent causes every hour in the United States [

1], while crimes result in annual losses and associated costs exceeding

$4.9 trillion nationwide [

2]. Confronted with the complex evolution of criminal patterns, traditional passive-reactive governance models urgently require transformation into data-driven proactive early warning mechanisms. Crime spatiotemporal prediction refers to the analysis and modeling of implicit spatiotemporal distribution patterns from historical crime and related data, thereby effectively forecasting the time and location of future criminal activities [

3]. As a crucial tool for preventing and combating crime, the accuracy of such predictions is essential for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of urban security management [

4].

The urban environment influences the spatiotemporal distribution of crime, a mechanism primarily explained by four major theoretical frameworks in environmental criminology: Routine Activity Theory emphasizes that the three conditions for crime occurrence (suitable target, motivated offender, and absence of guardian) are affected by the functional layout of the environment [

5]; Broken Windows Theory focuses on the signal of neglect and lack of control conveyed by physical environmental decay [

6]; Social Disorganization Theory highlights how neighborhood spatial structures shape informal social control [

7]; and Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) proposes proactive intervention strategies through dimensions such as spatial accessibility and natural surveillance [

8].

The evolution of crime prediction models reflects the ongoing pursuit of accurately capturing these complex spatiotemporal dynamics. Early traditional statistical models primarily focused on the overall trends and distribution characteristics of crime phenomena. For instance, Polvi et al., based on the near-repeat victimization effect, found that the risk of burglary increased significantly in the short term but decayed rapidly over time [

9]; Mohler et al. proposed self-exciting point process models, revealing the contagion and diffusion mechanisms of crime risk in space [

10]; Kalinic et al. compared kernel density estimation and hotspot analysis methods, indicating that their combination could effectively improve crime hotspot identification [

11]. Subsequently, machine learning methods demonstrated stronger capabilities in handling heterogeneous crime data, capturing non-linear spatiotemporal relationships, and enabling dynamic predictions. For example, Law et al. used Bayesian models to identify crime trend variations across different areas [

12]; Yi et al. proposed a hybrid model integrating LSTM with autoencoders for crime prediction, maintaining accuracy while reducing computational complexity [

13]. Currently, deep learning has become the primary technical choice for crime spatiotemporal prediction, where Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are widely used to capture spatial dependencies, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants (e.g., LSTM) or Transformer architectures are employed for temporal modeling, continuously pushing the boundaries of predictive accuracy. Representative works include Huang et al.’s DeepCrime and MiST models, which capture complex dependencies in crime sequences through multi-modal encoding and attention mechanisms [

14,

15]; Sun et al.’s CrimeForecaster, which combines Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) with gated recurrent units to effectively model spatiotemporal dynamics [

16]; and addressing the limitations of pre-defined spatial relationships, Sun et al.’s AGL-STAN model, which introduces adaptive graph learning and employs Transformer architecture for more expressive power and parallel computation capability [

17].

A critical enabler for these data-driven models is the incorporation of urban environmental data. In existing research, Point of Interest (POI) data, owing to its open accessibility and ability to quantify urban functional attractiveness, has become a crucial type of urban environmental data in crime spatiotemporal prediction models for characterizing spatial dependencies. By categorizing urban functions, POIs can reflect the three conditions emphasized in Routine Activity Theory, thereby influencing the spatiotemporal distribution of crime. For instance, commercial facilities (e.g., shopping malls, banks) are positively correlated with theft [

18], while transportation hubs (e.g., bus stops) increase the risk of pickpocketing due to complex human flows [

19]. This provides a theoretical foundation for utilizing POI data in crime spatiotemporal prediction. Early studies employed linear regression [

20] and spatiotemporal association mining [

21] to validate the enhancing effect of POI data on community crime rate prediction. With the advancement of spatiotemporal graph neural networks, the application of POIs in crime spatial modeling has become more widespread. For example, Wang et al. [

22] proposed a homogeneity-aware graph neural network that innovatively introduced an adaptive regional graph learning mechanism, using POI and administrative boundary data to generate a homogeneity-aware crime propagation topology. However, although POIs provide urban functional features for crime prediction, they lack spatial morphological information, making it difficult to represent the continuity and mixed-use nature of spatial functions [

23]. As a result, POI data cannot fully capture the physical environmental decay characteristics central to Broken Windows Theory, the neighborhood spatial structural attributes highlighted by Social Disorganization Theory, or the spatial form control mechanisms relied upon in CPTED.

Buildings are a fundamental component of urban spaces. As open-source urban environmental data, building footprints provide detailed information on urban structure and spatial layout. Identifying and analyzing their morphology is of great significance for modeling and characterizing urban geography, semantically classifying social functions, and predicting economic activities [

24]. Extracted from remote sensing imagery, building footprints capture the geometric forms and spatial distribution features of structures, offering a high-resolution continuous representation for analyzing the spatiotemporal distribution of crime. A separate line of research in urban analytics and criminology has leveraged building footprints to uncover correlations with crime, providing empirical support for the environmental criminology theories. For example, Pation et al. [

25] extracted structural and textural features from remote sensing imagery in a study conducted in Medellín, Colombia, and found that areas with high homicide rates often exhibit higher local variability and lower overall homogeneity. This indicates more crowded and disordered urban layouts, which are associated with weaker social cohesion, consistent with Social Disorganization Theory. Meanwhile, Broken Windows Theory suggests that chaotic building layouts may signal physical disorder in an area, thereby attracting criminal activity. For example, Silva and Li [

26] developed multiple metrics based on building footprints in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, and conducted regression analyses between these metrics and crime rates. They found that a higher percentage of open space is correlated with lower crime rates, whereas older neighborhood age is associated with higher crime rates. According to CPTED, open spaces enhance visibility and reduce fear of crime, thereby improving safety. Broken Windows Theory, in turn, explains that older neighborhoods with more dilapidated and damaged buildings tend to experience higher crime rates. Ioannidis et al. [

27] investigated the correlation between building density and crimes such as burglary and street theft using remote sensing imagery from Stockholm, Sweden. The results indicated that both types of crime are associated with building density: burglary occurs more frequently in areas with high building density, while the relationship between street theft and building density varies significantly across different planning zones and is easily influenced by other factors. Routine Activity Theory suggests that areas with higher building density offer more criminal opportunities, such as a greater number of valuable targets.

These studies demonstrate that building footprints can represent the continuous and mixed-use nature of urban spatial functions and provide theoretical support for explaining crime distribution. However, they have primarily focused on macro-level correlation analysis or static regression modeling, and have not been sufficiently explored as deep features for enhancing end-to-end spatiotemporal prediction models. This creates a gap between the proven explanatory power of building morphology and its underutilization in dynamic forecasting frameworks.

To address this gap, this paper applies building footprint data to characterize urban regions to construct spatial dependencies in crime spatiotemporal prediction models. Specially, we first fuse building footprints and POI data using Region Dual Contrastive Learning (RegionDCL) [

28] to represent urban areas. Then, the learned region representations are incorporated as a region graph into crime prediction models based on different technical approaches. Finally, we use these prediction models to predict the occurrence of four types of crimes (Burglary, Robbery, Felony Assault, and Grand Larceny) to validate the effectiveness of building footprints in crime spatiotemporal prediction. The experimental results on New York City crime data indicate that: (1) the region representations significantly improve deep learning model performance, with the most improved LSTM achieving average increases of 5.66% in Macro-F1 and 18.57% in Micro-F1, particularly benefiting baseline models with lower accuracy; (2) the region representations yields more significant improvements for low-frequency crime categories and mitigates temporal memory decay in long-term predictions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 elaborates on the proposed methodology, including the construction of the region graph based on building footprints, the formation of the crime tensor, the fusion module, and the spatiotemporal prediction models.

Section 3 introduces the study area and describes the datasets used in this research.

Section 4 presents the experimental results and discussions, covering model comparisons, predictions for different crime types, and ablation studies. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future work.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

The learned region representations are tensors with a shape of 71 × 64, meaning each of the 71 communities is characterized by a 64-dimensional vector. Following the dataset partitioning method used in prior studies [

16,

17], the crime data are divided chronologically into 6.5 months for training, 0.5 months for validation, and 5 months for testing. The training window length

K is set to 10 days, and the prediction period

S to 1 day. The geographic units of analysis are the 71 communities in New York City. For the fusion module, a three-layer MLP is used to map the region representations to the tensor space of the crime tensor, after which the mapped representations and the original crime tensor are combined via element-wise addition. The code is released in

https://github.com/Erdengxin/BF2Crime (accessed on 7 September 2025).

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Prediction Performance Across Models

Different models are tested with and without the region representations for multi-class prediction of the four crime types mentioned above. Daily predictions are averaged monthly, and the results are shown in

Table 3.

The “BF” column shows the baseline performance, while the “BF” column presents the absolute performance difference after integrating the region representations based on building footprints. A positive value indicates a performance gain. The rows labeled “Avg Macro↑” and “Avg Micro↑” display the average improvement ratios of Macro-F1 and Micro-F1. To statistically validate these improvements, we conducted one-tailed paired t-tests comparing the daily prediction performance with and without the region representations across the entire test period. The t-statistics and their significance levels are reported at the bottom of the table. Key observations include:

(1) All models except LR exhibit statistically significant improved prediction accuracy after integrating the region representations. As a machine learning model with only dozens of parameters and low complexity, LR is unable to utilize the high-dimensional region representations. Other models, whether based on RNN frameworks, Transformer frameworks, or encoder–decoder architectures, demonstrate consistent performance improvements following the integration of the region representations. These results indicate that deep learning frameworks for crime spatiotemporal prediction can effectively leverage the rich urban spatial semantics encoded in the region representations to enhance prediction performance.

(2) Models lacking explicit spatial dependency modeling experience significant performance gains when incorporating the region representations. For example, LSTM with the region representations achieves substantial improvements in both Macro-F1 and Micro-F1, outperforming the original RNN-based models MiST and CF. This finding confirms the effectiveness of the region representations in strengthening spatial dependency modeling.

(3) The improved accuracy of AGL-STAN with the region representations suggests that the predefined graph derived from the region representations complements the adaptive graph learning module. While the adaptive graph learning module dynamically captures spatial relationships through data-driven approaches, it may overlook complex or implicit spatial correlations. The region representations provide complementary urban spatial semantics, offering a comprehensive and accurate initial spatial framework to refine adaptive graph learning.

(4) The region representations yield more substantial improvements in long-term prediction tasks. For instance, LSTM with the region representations achieves increases of 2.82% in Macro-F1 and 14.60% in Micro-F1 in August, while 9.48% and 24.35% in December, respectively. Similar trends observed across models indicate that temporal dependencies degrade in long-term forecasting [

41], while the region representations mitigate this degradation by reinforcing the models’ understanding of urban spatial structures.

To summarize, the region representations enhance prediction accuracy across all deep learning frameworks, particularly for models with lower baseline performance and long-term forecasting tasks, where the improvements are more pronounced.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Prediction Performance Across Crime Types

Following a comprehensive evaluation of multi-class crime prediction performance with and without the region representations, the impact of the region representations on the prediction performance for specific crime types is further examined. Using different models (excluding LR due to its lack of improvement), binary classification predictions are conducted for Burglary, Robbery, Felony Assault, and Grand Larceny under two conditions: with and without the region representations. This granular analysis aims to uncover differences in spatiotemporal prediction across crime types and elucidate how the region representations enhance the models’ ability to capture these variations. Experimental results are shown in

Figure 4, where the y-axis represents F1-scores and the x-axis denotes months. Key findings are as follows:

Burglary: As shown in

Figure 4, LSTM, MiST, and CF exhibit limited predictive capability for Burglary without the region representations. It suggests that while these models can capture temporal dependencies, they lack sufficient spatial feature modeling. After integrating the region representations, LSTM achieves an average monthly improvement of 639.48%, MiST 112.03%, and CF 53.68%. Notably, AGL-STAN, which already demonstrates strong baseline performance without the region representations, still improves by 13.77% on average across months. These results indicate that even models explicitly modeling spatial dependencies can benefit from the additional spatial semantics provided by the region representations.

Robbery: After incorporating the region representations, LSTM shows consistent improvements in Robbery prediction. From August to December, F1-scores increase by 4.42%, 13.55%, 12.40%, 19.82%, and 11.18%, respectively, with a notable 19.82% improvement in November, validating the effectiveness of the region representations for long-term forecasting. The sustained 11.18% gain in December may be attributed to the region representations’ ability to capture spatial heterogeneity in street crimes, enhancing cross-temporal prediction robustness. AGL-STAN also records long-term improvements. However, MiST and CF exhibit unstable results: MiST’s attention mechanisms for spatial dependency modeling do not benefit from the region representations, while CF improves in August, November, and December but declines in September and October.

Felony Assault: All models exhibit strong baseline performance for Felony Assault but are affected by significant temporal performance decay. The region representations not only mitigate this decay but also improve accuracy in most months. For example, LSTM achieves a 24.80% improvement in December, substantially outperforming the baseline model’s long-term decay trend.

Grand Larceny: As shown in

Figure 4, all baseline models achieve F1-scores above 0.8 across all months for Grand Larceny, with minimal impact observed from the region representations. This crime type has the highest case count (43,116 cases), far exceeding the others, reducing the impact of spatiotemporal data sparsity [

3]. Models effectively capture its spatiotemporal patterns even in the absence of the region representations.

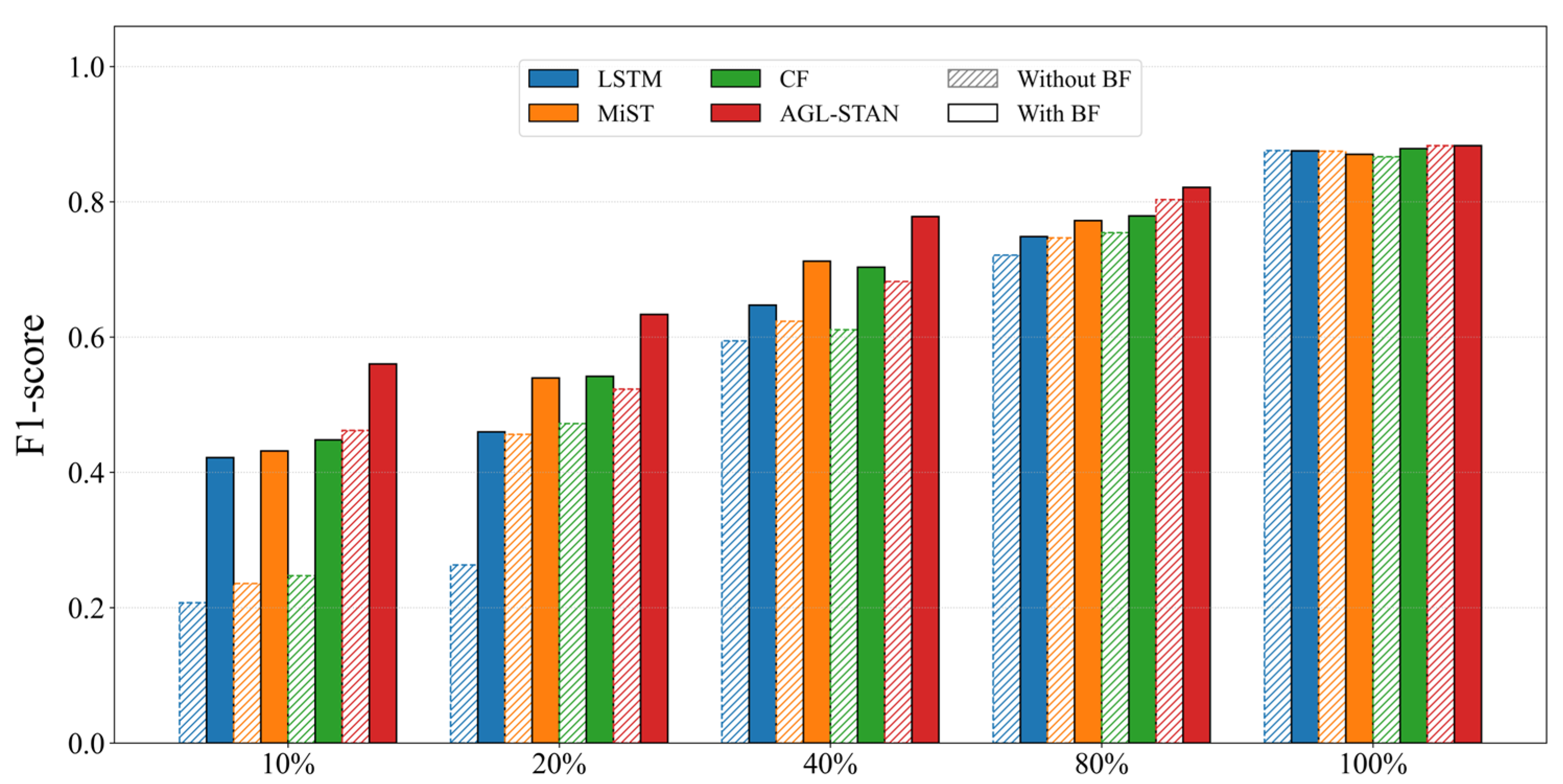

To further investigate the relationship between data volume, model performance, and the utility of our region representations, we conducted a down-sampling analysis on Grand Larceny. The results, illustrated in

Figure 5, compellingly demonstrate that the benefit of the region representations is profoundly modulated by data sparsity. When the data is severely limited (e.g., at 10% and 20% sampling rates), the incorporation of BF provides a dramatic performance boost across all models. For instance, the F1-score of LSTM more than doubles at the 10% level with BF, transforming it from a weak predictor to a reasonably accurate one. This indicates that the rich spatial semantics from building footprints serve as a critical source of information, effectively compensating for the lack of training examples. As the volume of training data increases (to 40% and 80%), the relative advantage of BF gradually diminishes, though it continues to deliver consistent improvements. Finally, when the entire dataset (100%) is utilized, the models become sufficiently saturated with crime-specific data, and the marginal gain from the spatial prior provided by BF becomes negligible, as originally observed.

Overall, the accuracy improvement provided by the region representations exhibits an inverse correlation with crime frequency, significantly alleviating spatiotemporal sparsity challenges for low-frequency crimes. In long-term forecasting tasks, the region representations effectively counteract performance degradation by capturing the persistent influence of spatial factors, thereby maintaining temporal stability in predictive efficacy.

4.4. Ablation Study

4.4.1. Ablation Analysis of Components in the Region Representations

To analyze the impact of different components on improving crime spatiotemporal prediction performance through the region representations, feature ablation experiments were conducted across various models. Each model was evaluated under the following four experimental settings for multi-class crime prediction:

(1) Base model: without incorporating any region representations.

(2) Base model + POI: the base model augmented with region representations constructed solely from POI data.

(3) Base model + building footprints: the base model enhanced with region representations derived only from building footprints.

(4) Base model + POI + building footprints: the base model integrated with the complete region representations combining both POI and building footprints.

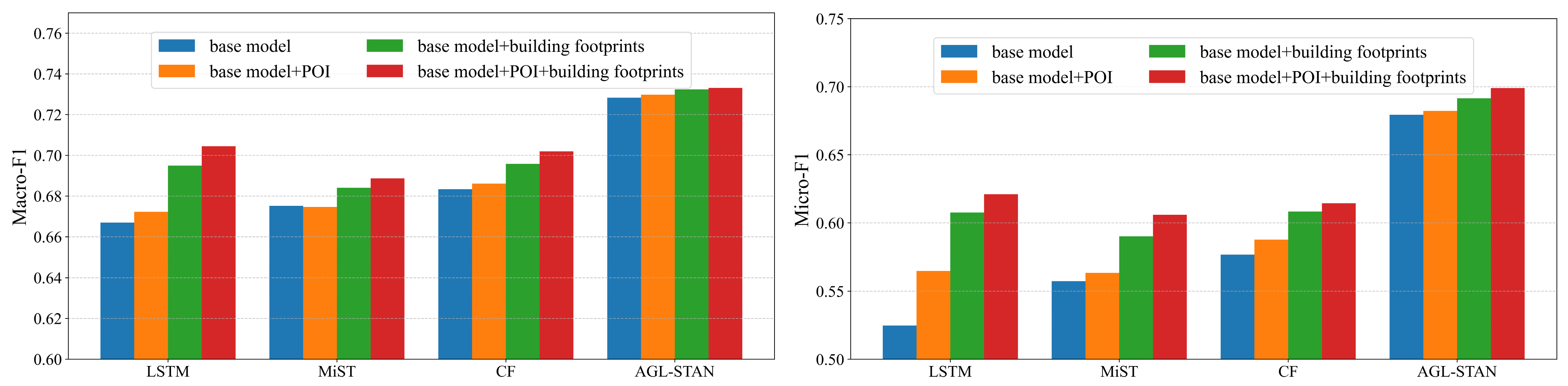

The experimental results, shown in

Figure 6, demonstrate that the incorporation of the region representations generally improves the predictive performance of the base models, with the complete representation yielding the most significant gains, confirming the effectiveness of each component. Furthermore, the region representations based on building footprints contribute more notably to performance improvement than those based solely on POI, underscoring the dominant role of building footprints in constituting the region representations.

4.4.2. Comparison of Two Fusion Modules

To effectively integrate the region representations with the crime tensor for enhancing prediction performance, two fusion modules are explored: a CNN-based module and an MLP-based module. The CNN-based module employs convolutional layers to extract local spatial features from the region representations, generating high-dimensional embeddings that are then fused with the crime tensor. In contrast, the MLP-based module applies nonlinear transformations via multi-layer perceptrons to map the region representations into more expressive feature vectors before fusion.

Table 4 compares the prediction performance of models using the two fusion strategies, with the last two rows indicating the average improvement of MLP-based fusion over CNN-based fusion.

Experimental results demonstrate that the MLP-based fusion module enables models to leverage the region representations more effectively, leading to greater performance gains compared to the CNN-based approach. For LSTM, the CNN-based module performs comparably to the MLP-based module in August and September but exhibits noticeable declines in October, November, and December. This can be attributed to the limitations of convolutional layers in processing high-dimensional features, which may cause information loss, whereas MLPs better preserve and utilize rich high-dimensional information [

42,

43]. These results suggest that information loss in the region representations degrades long-term prediction accuracy, further supporting the role of region representations in compensating for temporal dependency decay by reinforcing spatial structure understanding. For MiST, CF, and AGL-STAN, models using CNN-based fusion underperform compared to their counterparts without the region representations in most months. This implies that information loss in the region representations introduces additional noise, which is particularly detrimental to complex models.

Although the incorporation of building footprints based contextual information generally enhances model performance, slight declines are observed in some cases. These variations can be attributed to several factors. First, the added high-dimensional structural features may overlap with spatial dependencies already captured by crime or POI data, leading to feature redundancy and potential overfitting in models with limited regularization capacity, such as MiST and CF. Second, not all models are equally compatible with heterogeneous spatial features. CNN-based fusion modules, for instance, may suffer from information loss when processing dense embeddings. Third, for high-frequency crime types such as Grand Larceny, the spatiotemporal signals are already strong, and additional structural features contribute less marginal information, occasionally introducing minor instability. Lastly, inconsistencies in the completeness or labeling quality of OpenStreetMap footprint data across communities may introduce noise into model learning.

5. Conclusions

Currently, POI data applied in crime spatiotemporal prediction exhibit limitations in providing urban spatial semantic information, as they struggle to represent the continuity and mixed-use nature of urban spatial functions. To address this issue, this study introduces open-source building footprint data as a new influencing factor. By generating urban region representation based on building footprints and integrating them into various crime spatiotemporal prediction models, the effectiveness of building footprints in enhancing prediction accuracy is validated through multi-dimensional evaluations, including cross-model comparison, long-term forecasting analysis, and fine-grained prediction across different crime types.

Using New York City’s building footprints, POIs and community boundaries, region representations were generated for NYC communities. Leveraging 2019 crime data, these representations were integrated into models such as LR, LSTM, MiST, CF, and AGL-STAN for multi-class predictions (covering Burglary, Robbery, Felony Assault, and Grand Larceny) as well as binary classification tasks for each of these four crime types.

The experimental results of multi-class predictions demonstrate that the region representations significantly enhance the prediction performance of LSTM, MiST, CF, and AGL-STAN models, proving their universal enhancement effect across deep learning frameworks. These representations exhibit cross-model generalizability and deliver greater improvements for models with lower baseline accuracy. Specifically, the region representations show more pronounced enhancements for models lacking spatial dependency modeling, such as LSTM, MiST, and CF, highlighting their capacity to encode rich urban spatial semantics. For AGL-STAN, the integration of the region representations also improves prediction performance, indicating that the predefined graph derived from these representations effectively collaborates with adaptive graph learning. This underscores the complementary value of combining prior knowledge with data-driven approaches in spatial relationship modeling.

The binary classification results for the four crime types reveal that incorporating the region representations leads to massive accuracy improvements for Burglary; results in greater long-term accuracy gains than short-term improvements for Robbery and Felony Assault; and yields limited enhancements for Grand Larceny due to its large sample size, where baseline models already achieve high accuracy. From the perspective of case volume, crimes with fewer instances exhibit lower prediction accuracy, while the region representations provide more significant improvements for these crimes. These patterns reveal varying levels of sensitivity across crime types to the urban spatial semantics embedded in the region representations.

For both multi-class crime predictions and type-specific tasks, the region representations consistently yield greater accuracy improvements in long-term forecasting. This is further supported by the fusion module experiments: CNN-based fusion causes information loss in the region representations, resulting in inferior long-term improvements compared to MLP-based fusion. By providing stable urban spatial semantics, the region representations effectively alleviate the memory decay issue in long-term predictions for temporal models.

The region representations offer a practical, low-cost pathway to enhance policing efficiency and strategic planning. By enabling lightweight models like LSTM to achieve performance competitive with complex architectures, this approach makes effective crime prediction accessible even for resource-limited police departments, lowering the barrier to adopting data-driven strategies. The marked improvement in forecasting low-frequency crimes such as Burglary allows law enforcement to move beyond generic alerts and conduct precisely targeted interventions in specific spatiotemporal contexts, addressing the challenge of data sparsity for these crime types. Furthermore, the stability of these representations supports not only dynamic resource allocation across different time scales but also provides a foundation for long-term urban safety planning. Insights derived from the built environment can inform crime prevention through CPTED, guiding infrastructure investments and urban management dec isions to proactively create safer communities.

Despite the promising results, this study has limitations that offer avenues for future work. The primary limitation is the external validity, as our experiments were conducted on data from New York City for the year 2019. Consequently, the generalizability of the findings to other urban contexts with different spatial structures (e.g., low-density cities, grid-based layouts) or to different time periods affected by unique socioeconomic factors or events (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) remains to be fully established. Therefore, a key direction for future research is to validate and potentially adapt the proposed framework across a diverse set of cities and over extended multi-year periods to rigorously assess its robustness and transferability. Future work also includes benchmarking against other representation methods and enhancing the interpretability of the learned features to better understand the specific urban factors driving the predictions. Additionally, the crime-influencing factors used in this study are all derived from open-source urban environmental data. In future research targeting specific cities, other types of influencing factors (such as population and weather data) could be integrated to further enhance the accuracy of crime spatiotemporal prediction.