Abstract

Deaf and hearing-impaired individuals rely on sign language, a visual communication system using hand shapes, facial expressions, and body gestures. Sign languages vary by region. For example, Arabic Sign Language (ArSL) is notably different from American Sign Language (ASL). This project focuses on creating an Arabic Sign Language Recognition (ArSLR) System tailored for healthcare, aiming to bridge communication gaps resulting from a lack of sign-proficient professionals and limited region-specific technological solutions. Our research addresses limitations in sign language recognition systems by introducing a novel framework centered on ResNet50ViT, a hybrid architecture that synergistically combines ResNet50’s robust local feature extraction with the global contextual modeling of Vision Transformers (ViT). We also explored a tailored Vision Transformer variant (SignViT) for Arabic Sign Language as a comparative model. Our main contribution is the ResNet50ViT model, which significantly outperforms existing approaches, specifically targeting the challenges of capturing sequential hand movements, which traditional CNN-based methods struggle with. We utilized an extensive dataset incorporating both static (36 signs) and dynamic (92 signs) medical signs. Through targeted preprocessing techniques and optimization strategies, we achieved significant performance improvements over conventional approaches. In our experiments, the proposed ResNet50-ViT achieved a remarkable 99.86% accuracy on the ArSL dataset, setting a new state-of-the-art, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating ResNet50’s hierarchical local feature extraction with Vision Transformer’s global contextual modeling. For comparison, a fine-tuned Vision Transformer (SignViT) attained 98.03% accuracy, confirming the strength of transformer-based approaches but underscoring the clear performance gain enabled by our hybrid architecture. We expect that RAFID will help deaf patients communicate better with healthcare providers without needing human interpreters.

1. Introduction

Sign Language (SL) serves as the primary non-verbal communication method for the hearing-impaired community, relying on specific body movements, gestures, and facial expressions to convey meaning. The technological field of Sign Language Recognition (SLR) focuses on converting these visual communications, whether from British Sign Language (BSL), American Sign Language (ASL), or other variants, into text or speech through computational means. Communication barriers persist because most hearing people lack fluency in Sign Language. Additionally, the deaf community faces internal communication hurdles due to the wide variety of sign languages. Researchers estimate that approximately 300 distinct sign languages exist globally, though this number continues to evolve as new regional variants develop. While American, British, and Chinese sign languages have the largest user bases, significant variations exist between sign languages used in different geographical areas, creating a complex linguistic landscape. According to Deafness and Hearing Loss [1], approximately 466 million people worldwide experience hearing disorders, including 34 million children, a number expected to exceed 700 million by 2050. Additionally, the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Learning has projected that by 2050, more than 900 million people worldwide will experience disabling hearing loss [2]. It includes individuals with varying degrees of hearing loss, from mild impairment to profound deafness. The World Federation of the Deaf [3] estimates that around 70 million people are deaf, meaning they are unable to perceive sounds in a conversational context. Despite the significant size of the deaf or hard-of-hearing (DHH) population, this community continues to face considerable marginalization due to persistent communication barriers. Moreover, sign languages are not universal; they evolve uniquely within each deaf community [4]. American Sign Language (ASL) and Arabic Sign Language (ArSL) have distinct signs and grammatical structures. Most existing approaches directly translate between Arabic and ArSL. However, Luqman and Mahmoud [5] demonstrated that this approach is inadequate due to significant structural and grammatical differences between the languages. Even within the Arab world, multiple variations in ArSL exist, influenced by regional dialects and differences in spoken language across countries. Additionally, the terms “sign detection” and “sign recognition” are often used interchangeably, which can lead to confusion in the field. To clarify, sign detection refers to identifying the presence and location of signs within images or videos, serving as the first step in any sign language processing system. In contrast, sign recognition follows detection and focuses on interpreting the detected signs, making detection a prerequisite. In this hierarchy, recognition is a more specific task embedded within the broader process of detection. According to Kamal and others [6], sign language recognition involves translating recognized signs into text and may include fingerspelling, isolated word recognition, or continuous signs. Isolated word recognition deals with identifying single signs, while continuous recognition interprets sequences of signs to form complete sentences. However, in [7], the authors affirm that sign languages are broadly classified into two categories: static and dynamic, incorporating both manual and non-manual components. This classification provides a foundational framework for researchers and designers of sign language recognition systems. To develop robust and real-time recognition systems, it is essential to integrate both manual and non-manual elements effectively. Manual signs primarily involve hand configurations and movements. We can further divide them into static signs, which involve fixed hand gestures that may be performed using one or both hands. In contrast, dynamic signs are characterized by movement and can be further categorized into isolated and continuous forms. To enhance expressiveness and include emotional content, dynamic signs often involve non-manual elements, such as facial expressions, head movements, and gestures from body parts like the eyes, lips, and eyebrows. These features play a critical role in conveying meaning and nuance in sign language communication. This study makes the following key contributions:

- Our primary contribution is ResNet50ViT, a novel hybrid architecture that synergistically combines ResNet50’s hierarchical local feature extraction with ViT’s global attention mechanism to achieve superior performance on Arabic Sign Language Recognition (ArSLR). This approach uniquely addresses the challenges of ArSL by simultaneously processing local features through CNNs and capturing long-range dependencies via Transformers.

- A Keyframe Extraction approach leveraging motion detection has been introduced, incorporating a novel configuration strategy that ensures uniform key frame selection. This enhancement improves computational efficiency, making the technique both precise and highly effective.

- A data preprocessing strategy introduces various techniques to preprocess the ASiL dataset using an innovative method that balances performance with computational efficiency.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related and existing work. Section 3 presents the background theory, which includes deep learning methods. Section 4 details the proposed framework. Section 5 provides an in-depth explanation of our novel contributions, particularly the ResNet50-ViT architecture. Section 6 describes the experimental setup and results. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Works

Over the past few decades, sign language detection and recognition have been a major focus for researchers. To address this challenge, researchers have employed various machine learning and deep learning techniques. Since sign languages vary by region, with each often based on the local spoken language, researchers have sought to develop distinct sign language recognition systems for each. Most of the existing work centers around American Sign Language (ASL), Indian Sign Language (ISL), Korean Sign Language (KSL), and Turkish Sign Language (TSL), with comparatively less attention given to Arabic Sign Language (ArSL). This paper reviews recent progress in machine learning and deep learning approaches for visual sign language recognition and its translation into natural language understandable by hearing individuals. In [8], Shin et al. developed a vision-based transformer for KSL recognition. This multi-branch network combines transformers and convolutional approaches to extract long-range dependencies within images. The model achieves a recognition accuracy of 89.00% on a 77-label KSL dataset and 98.30% accuracy on a laboratory dataset. Rathi et al. [9] proposed a two-level ResNet50-based neural network for fingerspelling recognition in ASL. Evaluation was performed on a dataset containing 60,336 images spanning 36 classes (10 digits and 26 letters), achieving a test set accuracy of 99.03%. In [10], Wadhawan and Kumar developed a system for recognizing ISL words, alphabets, and digits. They created a dataset of 35,000 images showing 100 different signs captured in various environments using a webcam. Their system yielded an accuracy rate of 99.72% during training and validation. Thakar et al. [11] focused on converting ASL to text using transfer learning. They employ VGG16, pre-trained and fine-tuned, for the task. The approach highlighted how transfer learning accelerates training while maintaining high accuracy in recognizing ASL gestures from images. The recognition accuracy increased from 94% with CNN to 98.7% using transfer learning. In addition, Areeb et al. [12] presented 412 videos of ISL covering eight emergency scenarios and applied data normalization for uniform pixel distribution. Two classification models were used: a 3D CNN with 82% accuracy, and a pre-trained CNN-LSTM hybrid that achieved 98% accuracy by capturing both spatial and temporal features. However, it struggled with signal recognition due to similar movements. The third model, YOLO v5, an advanced object detection model, was applied after annotating the frames and outperformed the others with a mean average precision of 99.6%. In [13], Zakariah developed a CNN-based system for identifying Arabic letter signs. He used data augmentation to expand 32,000 photos into 160,000 images. The EfficientNetB4 model yielded an accuracy rate of 95% when tested on the ArSL2018 dataset containing 32 classes. Luqman and El-Alfy [14] introduced an ArSL dataset with 6,748 video samples of 50 signs performed by four signers, captured using Kinect sensors. By leveraging transfer learning and fine-tuning, the MobileNet-LSTM model attains 99.7% accuracy in signer-dependent mode and 72.4% in signer-independent mode. In [15], Bora et al. created a system to recognize Assamese Sign Language gestures. They built a dataset with 2D and 3D hand gesture images and used MediaPipe to detect landmarks. Their dataset contains 2094 data points, effectively classifying hand signals, including the alphabet. The model reached 99% accuracy. In [16], Özdemir et al. introduced a signer-independent SLR evaluation benchmark named BosphorusSign22k. The dataset contains over 22,000 isolated video samples showing 744 distinct Turkish sign glosses performed by six native signers. Researchers applied two established video recognition methods: 3D ResNets (MC3) achieved 94.76% accuracy, while IDT reached 88.53% accuracy. In [17], Suardi used a VGG16-based CNN architecture to recognize SIBI, an Indonesian sign language. The study demonstrated that VGG16’s architecture works well for sign language recognition, achieving over 98.32% accuracy in image classification tasks. Moreover, in [18], Islam et al. introduced an ArSLR method utilizing an EfficientNetB3 architecture integrated with an encoder–decoder network. This approach is designed to recognize 28 Arabic letters and numbers ranging from 0 to 10. The proposed method features an efficient CNN model with reduced computational requirements, making it suitable for edge devices while delivering commendable performance. The model achieved an average precision of 99.40%, a recall of 98.90%, an F1-score of 99.10%, and an accuracy of 99.26%. Alamri and Lajmi [19] introduced the ASiL dataset, which comprises 118 static hand signs, with 50 images per class, resulting in a total of 5900 images. This dataset is centered on ArSL and utilizes Static LabelImg for precise annotations [20]. Accurate annotations enhance the quality of the training data, allowing models to learn more effectively from the provided examples. The authors implemented MobileNet along with fine-tuning of the SSD-ResNet50 V1 FPN architecture. The model demonstrates an average F-score of 86.4% and an accuracy of 94%. In [21], Noor et al. built a hybrid CNN-LSTM model for ArSL recognition. They created their dataset with 4,000 images for 10 static gestures and 500 videos for 10 dynamic gestures. Their system achieved 94.40% accuracy for static gestures and 82.70% for dynamic gestures. In [22], Al-Barham et al. used the ArSL-2018 dataset to translate Arabic Sign Language letters into Arabic text. This dataset contains 54,049 images of 32 alphabets performed by 40 signers. They tested several deep learning models, including CNN, VGG-16, and ResNet-18. Their modified ResNet-18 model achieved the best results with a test accuracy of 99.47%. Mahmoud, Wassif, and Bayomi created the ArSL dataset [23]. They aimed to design a hybrid architecture combining Transfer Learning (TL) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to recognize ArSL. By integrating TL and RNNs, the model achieves an accuracy of 93.4%. Moreover, in [24], Gochoo et al. studied ArSL using a small dataset of 49 two-handed signs. They fine-tuned a Vision Transformer model to achieve high accuracy with minimal computing resources. Their dataset included fewer than 10 signers. The model achieves recognition accuracy of 93%. This architecture leverages the exceptional performance of transformers in natural language processing and extends their application to address complex challenges in computer vision. Specifically, transformers are employed for image classification tasks, with attention mechanisms synergistically integrated with convolutional networks to enhance interpretability and accuracy. In this work [25], Liu et al. demonstrated that ViT excels in capturing intricate spatial information. In [26], the authors compared ViT and CNNs, emphasizing how ViT handles complex gesture details and contextual dependencies more effectively. A comparative analysis of existing methodologies for sign language recognition is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative Evaluation of Methodologies for Sign Language Recognition.

Table 1, previously shown, provides a comprehensive comparison of fifteen research studies based on various criteria, including type of dataset, number of classes, primitive language, sign types, methodology, and accuracy. The availability of datasets varies significantly across sign languages. Many studies focus on ASL and ISL, supported by several well-established public datasets. In contrast, ArSL remains under-researched, primarily due to the lack of a standardized, publicly available dataset. As a result, ArSL research often relies on custom datasets. For example, Al-Nafjan et al. [30] and Luqman and El-Alfy [14] developed an ArSL dataset to account for Arabic’s approximately 3000 words, each represented by unique signs. Most studies employed around twenty-two classes to improve the system’s ability to recognize variations in hand size, position, configuration, and skin tone. CNNs and TL were commonly used to achieve robust results. For languages like American Sign Language (ASL), numerous standard datasets exist, such as the Purdue RVL-SLLL ASL Database [31], Boston ASLLVD [32], and RWTH-BOSTON [33], which support more extensive research. However, Robert and Duraisamy [34] demonstrate that SLR faces multiple challenges, including the complexity of constructing a visual representation that captures gestures, facial expressions, and body movements, as well as accurately identifying and translating gestures. Extracting features from images or videos with varied sizes and postures, and managing the subtle transitional movements in temporal segmentation, is difficult. One significant challenge is the limited availability of datasets, especially for ArSL. Creating a comprehensive dataset is crucial for enhancing recognition. Other challenges include recognizing signs produced by different individuals, accounting for variations in gestures, hand postures, body sizes, operating habits, and rhythms. Additionally, it is difficult to extract common features from different signers without confusion and to track transitional movements between the start and end of signing or between consecutive sentences in continuous SLR. Although many sign language videos are available online, most lack proper and correct annotations, making them unsuitable for use in recognition and translation systems, as highlighted by Luqman and El-Alfy [14]. Moreover, no ArSL database exists that encompasses most sign words, and more particularly in the medical field. Most existing studies primarily focus on isolated signs, which limit their practical applicability. For example, the approach in [29] is constrained by its emphasis on isolated sign recognition, along with challenges such as variability in signing styles, high resource demands, limited dataset size, multilingual support, and the lack of real-time translation capabilities. Another difficulty is accommodating the significant differences in syntax between sign language and spoken language, such as lexicon, word order, and sentence structure. The theoretical accuracy in sign language recognition depends on several factors, including dataset size, image quality, choice of algorithm, and the number of sign classes. Still, practical accuracy varies for each sign based on its complexity and similarity to others. Our work introduces a novel hybrid approach that integrates Vision Transformers (ViTs) to capture global sign characteristics and CNNs to extract local features, effectively overcoming the limitations of prior methods that rely on a single model type. Vision Transformers (ViTs) segment an image into patches and apply self-attention mechanisms to model spatial correlations across the entire image. This enables them to effectively capture high-level semantic content and global contextual relationships, making them well-suited for understanding long-range dependencies. However, ViTs often struggle to preserve fine-grained local details. In contrast, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) excel at extracting localized, low-level features but typically lack the capacity to model broader contextual information. While several studies have attempted to combine these complementary architectures [35,36], their effectiveness is often hindered by suboptimal fusion techniques or unbalanced feature representations. The key contribution lies in a novel integration strategy that effectively combines convolutional and attention-based components, offering a robust framework for video-based sign language recognition and informing future designs of hybrid deep learning systems.

3. Background Theory

Deep learning, a branch of machine learning, leverages artificial neural networks with multiple interconnected layers to automatically extract hierarchical features from data. As noted in [37,38], this approach has transformed fields such as natural language processing and computer vision by enabling the analysis of large and complex datasets. A cornerstone of deep learning is transfer learning, which involves utilizing pre-trained models typically trained on extensive datasets and fine-tuning them for specific tasks. This approach is especially effective in situations with limited labeled data, as it enables knowledge transfer across domains, resulting in robust performance even with minimal resources [39].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the keystone of modern computer vision, designed to automatically learn spatial hierarchical features from edges and textures to complex object representations through convolutional operations [26,40]. Their success has been further amplified by transfer learning, where models pre-trained on large-scale datasets are fine-tuned for specialized tasks such as sign language recognition (SLR).

Among the most influential CNN architectures is ResNet50 [41], which introduces residual connections to address vanishing gradients in deep networks. These skip connections enable stable training of networks with dozens or even hundreds of layers by allowing gradients to flow directly through identity mappings. An enhanced variant, ResNet50V2 [42], refines the original architecture by repositioning batch normalization and activation layers, resulting in improved performance and generalization. While these architectures have demonstrated good performance in image classification and related tasks, they primarily model local spatial dependencies.

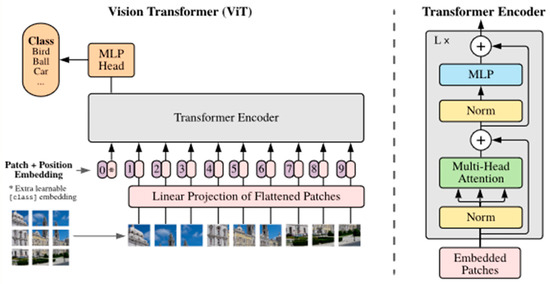

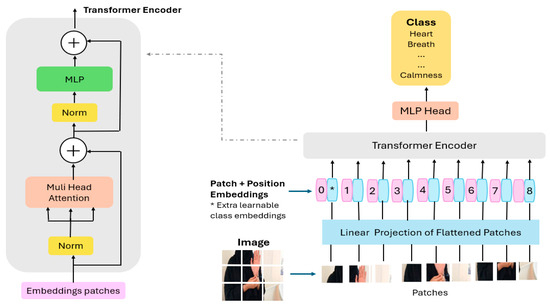

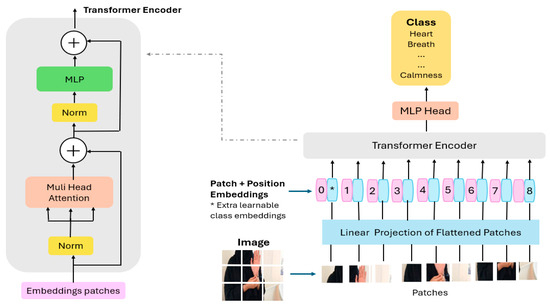

In contrast, Vision Transformers (ViT) [43] outperform CNNs in terms of computational capabilities, accuracy, and efficiency [44]. They offer key advantages for image-related tasks, including the ability to model long-range dependencies, accommodate variable input sizes, and enable parallel processing. These features make ViTs a promising alternative to CNNs. However, they also present certain limitations. ViTs often require substantial computational resources, involve large model sizes, and may struggle with scalability on huge datasets. Additional concerns include limited interpretability, susceptibility to adversarial attacks, and potential challenges in achieving strong generalization [26]. In this study, we focus on a medium-sized dataset, which helps mitigate some of these challenges and allows for a more balanced comparison between ViTs and CNNs. The original ViT, introduced by Dosovitskiy et al. [43], demonstrated impressive performance across various image classification benchmarks. Unlike CNN-based approaches, ViT directly processes sequences of image patches using a pure transformer encoder. ViT provides two major advantages. The first is the self-attention mechanism, which enables the model to process a broad range of input tokens within a global context, and the second is the capacity to train effectively on large-scale tasks. To better understand this architecture, Figure 1 illustrates the workflow of ViT. The input image in ViT is first segmented into a series of non-overlapping patches, which are then projected into patch embeddings. The patch embedding is then enhanced with a one-dimensional, learnable positional encoding to retain spatial information. This is because a transformer has no inherent understanding of sequence order, so positional information is incorporated before the joint embeddings are passed into the encoder. As described in [7], the encoding process consists of two main components: Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) and the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). The input embeddings are first normalized using a normalization layer, producing normalized values used to calculate Query (q), Key (k), and Value (v) matrices. The MHSA module then applies the attention mechanism using Equation (1).

where refers to the keys of dimension dk. The attention weights are obtained by computing the dot product between the query and each key, scaling the results by √dk, and then applying the softmax function to produce a probability distribution over the values.

Figure 1.

The architecture of the vision transformer [43], where (*), an extra learnable [class] embedding is appended to the patch embeddings to represent global image information.

This operation captures relationships across different patches. The output from the attention layer is passed to the feed-forward layer, which generates the final encoder output. Finally, a learned [class] token is connected to the patch embeddings to aggregate the global representation, and it functions as the classification’s final output [25].

Recent research highlights the advantages of combining ViT and CNNs for feature extraction, leveraging their respective strengths in global and local feature representation. For example, in [45], Nojood M. and Salha M. demonstrated that ViT effectively captures contextual dependencies in ArSL, enabling better classification compared to CNNs.

4. System Framework

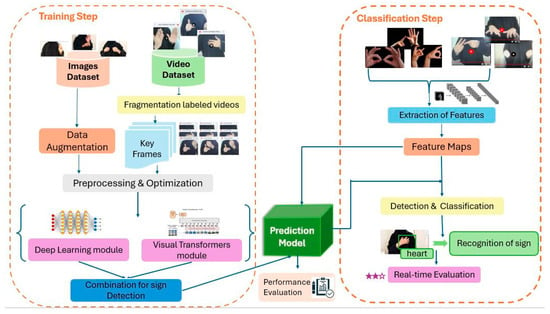

Through this work, we aimed to propose a novel system to recognize ArSL from an input set of images or videos. This proposed approach begins by collecting the dataset called ASiL, built by Alamri and Lajmi [19]. Our framework is presented in Figure 2. The innovative aspect of this system lies in the optimization of video fragmentation, data preprocessing, and the construction of a hybrid model. The system operates through a two-phase process:

Figure 2.

Architecture of the proposed approach.

- Training: In the training phase, beginning with a diverse image and video dataset, which is presented in Section 4. This image dataset is enhanced through data augmentation techniques, such as geometric transformations. In contrast, the video dataset is converted into key frames, each annotated with labels, resulting in a total of 23,000 frames. This extraction is performed using a motion-based method, as detailed later. These two datasets are then subjected to preprocessing and optimization steps to standardize the data for efficient model training. Multiple models are employed in Section 5: a deep learning-based sign detection model extracts static features from the augmented images, while a vision transformer model captures dynamic features from key frames. Then, we combined one of these trained models with a vision transformer to create a unified hybrid model that learns both the local and global information flow of ArSL. The model’s performance is rigorously evaluated using various performance metrics during training.

- Classification: A video input or image is processed through the trained model to extract feature maps, which are used for the detection and classification of signs. The classified signs are subsequently translated into textual output, facilitating the translation of ArSL gestures into corresponding words. The system will incorporate continuous evaluation to monitor performance, ensuring robust and accurate recognition. Thus, this approach utilizes cutting-edge deep learning techniques combined with transformer architecture to provide a scalable solution for ArSL recognition.

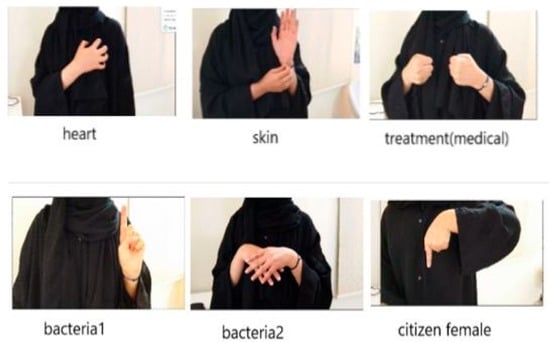

4.1. ASiL Dataset

According to researchers, a few datasets are available for ArSL. Researchers often lack access to a reliable ArSL database due to the complexity of the Arabic language [4]. As a result, they are required to manually construct datasets, a process that is both time-consuming and resource-intensive. For this work, we created a new dataset using the most significant words in the medical context, as presented in Figure 3. The ASiL dataset was compiled from the dictionary curated by the League of Arab States (LAS) and the Arab League Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization (ALECSO), which in 1999 proposed a standardized Arabic Sign Language (ArSL) to unify diverse regional variants into a single system. For this language, a lexicon containing 3000 signs was published in two sections [46,47]. The dataset encompasses various medical terminology including anatomical terms (e.g., ‘vein,’ ‘feet’), conditions (‘burn,’ ‘accident’), treatments (‘antibiotic,’ ‘vitamin,’ ‘dose’), sensations (‘high,’ ‘to suffer’), concepts (‘compulsion,’ ‘benefit,’ ‘system,’ ‘insignificance’), and spatial references like (‘everywhere,’ ‘falling’), providing thorough coverage of medical vocabulary.

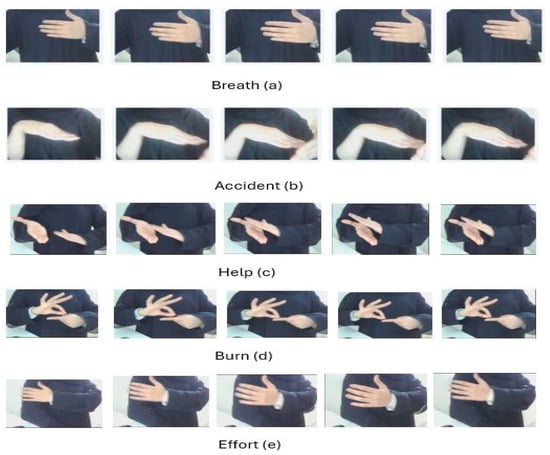

Figure 3.

Dataset ASiL Examples.

To ensure consistency during data collection, four students recorded videos using a high-definition phone camera under uniform lighting conditions. While this approach guarantees standardized environmental settings, it may introduce biases due to limited diversity in recording conditions and participants. Before data collection, all students signed a consent form explicitly agreeing to the use of their video data for this research and its subsequent publication. Even with signed consent forms, ethical considerations regarding the long-term use, storage, and potential re-identification of participants need careful management.

4.2. Video Fragmentation

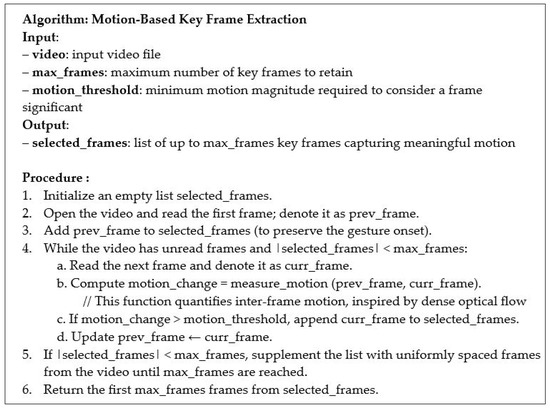

In this work, we are handling videos that feature movements representing signs. Our goal is to extract key frames that best capture the dynamics of these movements. These key frames are selected based on their relevance, with a particular emphasis on frame-to-frame differences that reflect meaningful changes in motion. The method we adopt is motion-driven: a new key frame is identified whenever significant movement is detected between consecutive frames. This motion-based selection, driven by changes in motion, helps isolate important transitions within a video, thereby improving the accuracy and efficiency of subsequent processing stages.

To quantify motion, our approach is inspired by the principle of dense optical flow, which captures pixel-level displacements between frames. By analyzing motion changes between consecutive frames, we identify moments where the content evolves substantially, such as the start or transition of a sign. This ensures that the extracted frames correspond to the most informative temporal points, effectively isolating the essential segments for gesture representation. Our motion-aware keyframe extraction procedure, summarized in a simple algorithm in Figure 4, prioritizes frames exhibiting high motion magnitude.

Figure 4.

Motion-Aware Key Frame Extraction.

Using this procedure, we extract up to five key frames per video, prioritizing those that reflect clear movement changes while skipping redundant frames. In cases where fewer than five motion-relevant frames are detected, the selection is supplemented with evenly spaced frames to maintain consistency across samples. This strategy not only reduces data redundancy but also enhances the representativeness of the selected frames, leading to more efficient and accurate processing. Our method aligns with prior findings that human actions, including sign language gestures, can often be recognized reliably from as few as 1 to 7 well-chosen frames [48,49]. In summary, our dataset of 92 classes (4600 videos) broke down into five frames per video, as shown in Figure 5, resulting in a total of 23,000 key frames.

Figure 5.

Sample key frames extracted from ArSL videos.

4.3. Histogram Equalization

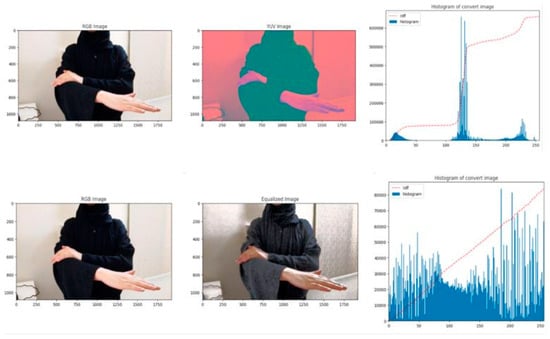

Data pre-processing is a critical step in deep learning that transforms data into a format suitable for efficient analysis by machine learning models. It enhances the model’s ability to interpret features and significantly impacts the generalization performance of supervised algorithms. Higher input dimensionality generally increases the sample complexity of learning, meaning that more training data are typically needed to achieve reliable generalization and mitigate overfitting. Improving data quality through pre-processing is essential for better model performance [50]. The preprocessing phase begins by resizing all input images from their original resolution of 1080 × 1920 pixels to 400 × 400 pixels to standardize input dimensions and reduce computational load. To address variability in lighting conditions, common in real-world sign language recordings, we apply histogram equalization (HE) [51], a contrast enhancement technique, to improve the visibility of hand gestures and facial expressions. While Histogram Equalization (HE) is a well-established method (see [52,53] for more details), its application in Arabic Sign Language Recognition (ArSLR) helps mitigate challenges posed by low-contrast frames, thereby improving input quality. This preprocessing step aims to make discriminative visual features more discernible, which may support better model performance. Figure 6 illustrates the process of HE, an image processing technique that enhances contrast and improves overall image quality by redistributing intensity values. This method adjusts the intensity levels to ensure better contrast, making dark areas darker and bright areas brighter, thereby revealing details that may otherwise be difficult to perceive in regions with suboptimal contrast.

Figure 6.

Our histogram equalization process.

4.4. Application of a Noise Reduction Filter

Noise, introduced by camera limitations, compression artifacts, and low resolution, can disrupt feature detection. Common denoising techniques include Gaussian, median, Wiener, bilateral, and non-local means filters. A comparative analysis in [54] evaluated the effectiveness of these methods across different types of noise. We adopt the Non-Local Means (NLM) filter because it effectively reduces noise while preserving important structural details, as shown in [55]. For the full comparison of denoising techniques, see [56]. Our focus is on optimizing NLM’s parameters for the ArSL dataset, as detailed below. Although the NLM filter is highly effective at preserving fine details while reducing noise, it is computationally intensive, which can hinder real-time performance. To address the tradeoff between denoising performance and computational efficiency, Algorithm 1 optimizes the parameters of the Non-Local Means (NLM) filter. Specifically, it optimizes four parameters: h, hColor, template_size, and search_size, which influence the denoising quality. The algorithm begins by initializing tracking variables: best_result (to store the best denoised image), best_params (to record the corresponding parameters), and best_quality (initialized to infinity to ensure any valid MSE will improve it). It also records the global start time and computes the total number of parameter combinations as the product of the sizes of the four parameter lists: h_values, hColor_values, template_sizes, and search_sizes. The input image (img) in BGR format is first converted to RGB. The algorithm then exhaustively iterates over all possible combinations of the NLM denoising parameters. For each combination, the image is denoised using the Non-Local Means (NLM) algorithm with the current parameter set, the quality of the result is evaluated by computing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the RGB image and the denoised output, if the current MSE is lower than the best quality observed so far, the algorithm updates best_quality, best_result, and best_params. After all combinations have been evaluated, the total execution time is calculated as the difference between the current time and the initial start time. Finally, the algorithm returns the optimal parameter set (h, hColor, template_size, search_size), the corresponding denoised image, and the total runtime. This brute-force strategy guarantees identification of the parameter configuration that minimizes reconstruction error (MSE) over the defined search space.

| Algorithm 1. Optimization of NLM parameters (, search_sizes) |

| Input: initial value for h_values ← [5, 10, 15], hColor_values ← [5, 10, 15], template_sizes ← [7, 10, 15], search_sizes ← [21, 35, 45] Output: Best parameter value of h, hColor, template_size, search_size, total_time Initialization: tracking variables: best_result←None, best_params←None, best_quality← Infinity, start_time ← CurrentTime (), num_combinations ← Size(h_values) * Size(hColor_values) * Size(template_sizes) * Size(search_sizes) combination_counter ← 0 //Construct a Learning model

For each h in h_values Do

|

On the other hand, this algorithm is mathematically grounded in the computation of MSE between the input and the denoised images. Given the input image I and a denoised image D (h, hColor, t, s) produced by the parameters h, hColor, t, and s, the MSE is defined in Equation (2).

N is the number of pixels in the image, Ii and Di are the pixel values at corresponding locations in the input and denoised images, respectively. The algorithm iteratively computes the MSE for all parameter combinations, selecting the one that yields the lowest error. The goal is to find the set of parameters that maximizes denoising effectiveness while minimizing the loss of image detail. The total number of combinations tested by the algorithm is shown in Equation (3) below.

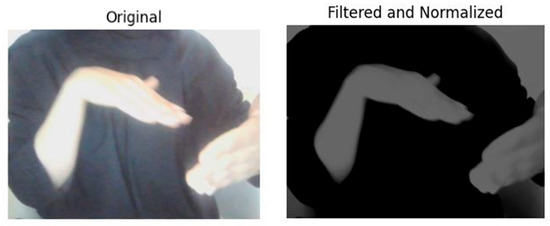

|h|, |hColor|, |t|, and |s| represent the sizes of the sets of possible values for each parameter. This results in a time complexity of O(n), meaning that the number of combinations grows exponentially as more parameter values are added. Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of the NLM filter for noise reduction, particularly in handling Poisson and speckle noise, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

NLM Filter optimized.

Our algorithm achieves an optimal tradeoff between denoising quality and computational efficiency by systematically optimizing the NLM filter’s parameters. Additionally, we apply feature normalization to ensure consistent scaling across input attributes, which is essential when combining heterogeneous features. Without normalization, differences in scale can bias learning and degrade model performance. Standard techniques such as min-max are employed for this purpose.

4.5. Data Augmentation

Deep CNNs benefit from increased depth, which generally improves representational capacity more than width. However, deeper networks are prone to overfitting, particularly on limited datasets, where the network overfits specific features instead of learning general patterns, leading to high training accuracy but poor performance on test data.

To mitigate this, a wide body of research has explored data augmentation in [50,56,57], particularly the popular geometric transformations, such as flipping, rotation, shifting, scaling, shearing, cropping, and noise addition. In our work, we employ a set of geometric data augmentation techniques during training. These transformations increase dataset diversity and improve the model’s robustness to real-world variations in pose, lighting, and framing. Specifically, we apply random horizontal flipping, rotation (±30°), width and height shifts (20% and 10%, respectively), zooming (±20%), and minor affine distortions. This strategy enhances generalization without requiring additional data collection, enabling the model to reliably recognize signs under varying positions, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Application of geometric transformations for data augmentation.

5. Arabic Sign Language Recognition Approaches

In this study, we proposed six proposals to advance the field of ArSL recognition. The first approach introduces two CNNs with varying numbers of layers. The second and third approaches involve two modified transfer learning models, incorporating fine-tuning techniques. Then we present a Vision Transformer (ViT) tailored for ArSL recognition. Finally, the last proposal presents a hybrid model that combines pretrained CNN-based architecture with ViT to leverage the strengths of both paradigms.

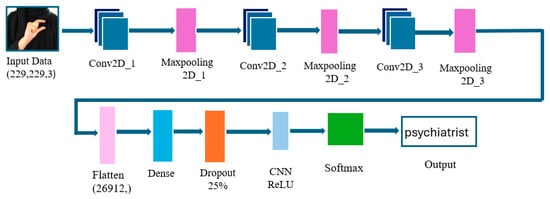

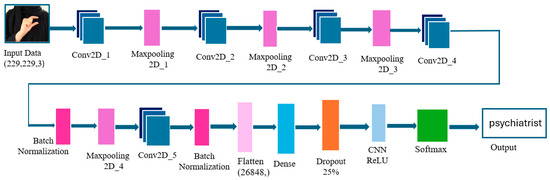

5.1. Approach 1: Architectures of Custom CNN

We developed two distinct CNN architectures from scratch to determine their effectiveness on our dataset, each with unique structural designs aimed at balancing complexity, training efficiency, and accuracy. The first architecture is relatively simple, a three-layer CNN, inspired by [4], featuring progressively reduced filter counts (128 → 64 → 32) and ReLU activations, followed by max-pooling and a fully connected classifier with dropout (rate = 0.25) and a 36-unit softmax output layer. Full architectural details are provided in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Illustration of our 3-Layer CNN Model.

Table 2 offers a summary of the parameters for each layer of the proposed network, along with the total number of parameters. Due to its relatively shallow structure, this model is efficient in terms of both computational resources and training time, making it suitable for smaller datasets, like those cases where overfitting is a concern. The faster training and reduced risk of overfitting make it a good candidate for environments with limited data and resources.

Table 2.

Summary of our 3-layer CNN model.

In contrast, the second architecture presented in Figure 10 is more complex. It consists of five convolutional layers with progressively decreasing filter counts (256 → 16) and a transition from 5 × 5 to 2 × 2 kernels to capture increasingly fine-grained features. It incorporates batch normalization around the final convolutional layer to improve training stability and a dropout layer (rate = 0.25) in the fully connected section to reduce overfitting. The network ends with a 512-unit ReLU dense layer and a 36-class softmax output. Full layer-wise specifications and parameter counts are provided in Table 3 below.

Figure 10.

Illustration of our 5-Layer CNN Model.

Table 3.

Summary of our 5-layer CNN model.

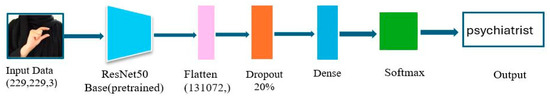

5.2. Approach 2: Architecture of ResNet50 Modified

High-resolution ArSL images present significant challenges in extracting meaningful features. Recent advances in technology have significantly improved the ability to carry out tasks like image classification and object identification on large-scale image datasets. The main driving force behind these developments has been the application of supervised learning methods on labeled datasets. However, in the specific context of sign language images, labeled data is often limited. To address this challenge, transfer learning is utilized to classify the ASiL images in this study. For the ASiL dataset in this study, two models were retrained, including ResNet50 and ResNet50V2.

The first transfer learning model uses ResNet50, pre-trained on ImageNet [58], with its top classification layers removed and all base layers frozen to preserve learned features [59]. Input images are resized to 229×229 pixels. The extracted features are passed through a custom head consisting of a flattening layer, a dropout layer (rate = 0.2), and a 36-unit softmax output layer for classification. The full architecture is illustrated in Figure 11, and the model is trained using the Adam optimizer with categorical cross-entropy loss.

Figure 11.

Architecture of ResNet50 modified.

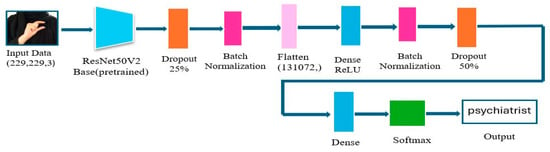

5.3. Approach 3: Architecture of ResNet50V2 Modified

The second transfer learning model employs Resnet50V2, pre-trained on ImageNet. As depicted in Figure 12, the ResNet50V2 model with its top layers removed and all base layers frozen to preserve learned features. The input images are sized at 229 × 229 pixels. A custom classification head is added, comprising batch normalization to improve model stability and generalization, dropout (25%), a 64-unit ReLU dense layer, an additional batch normalization and dropout (50%), and a final 36-unit softmax output layer for multi-class classification.

Figure 12.

Architecture of ResNet50V2 modified.

5.4. Fine-Tuning

Fine-tuning is a pre-trained CNN that involves leveraging the weights and biases of an existing model and adapting them to a new target dataset. Unlike standard CNN training, where weights and biases are randomly initialized and updated through backpropagation, requiring large datasets to avoid suboptimal results. Fine-tuning addresses the challenge of limited data. Instead of training the model from scratch, pre-trained models initialize convolutional layers with pre-learned weights, reducing the need for extensive datasets. During the fine-tuning process, these weights are gradually updated on the target dataset, enabling the model to refine its features while preserving the general knowledge learned from the pre-trained network. Various techniques exist for fine-tuning CNN hyperparameters, including Grid Search, Random Search, Bayesian Optimization, Hyperband, Genetic Algorithms, and Gradient-Based Tuning [60,61]. For hyperparameter tuning, we used Keras Tuner with Random Search, which is well-suited for smaller datasets and moderate search spaces [61,62]. We applied a search space for the number of neurons that was defined between 64 and 256, with increments of 16. The tuning process was conducted over four trials, with the number of epochs set to 15 per trial to expedite computation while still guiding toward optimal hyperparameters. The process begins with training the models on the new dataset while keeping certain layers frozen to maintain the learned features. Following this, a targeted fine-tuning phase is undertaken, where specific high-level layers are unfrozen and trained using a very low learning rate to prevent overfitting. During this phase, the weights are recalculated and backpropagated through the pre-trained layers, while the deeper layers remain unchanged. This approach strategically allows for incremental improvements, minimizing the risk of overfitting by carefully adjusting the pre-trained weights.

5.5. Approach 4: Architecture of SignViT

We implement a task-adapted Vision Transformer, denoted SignViT, designed for sign recognition. Figure 13 illustrates the architecture of the SignViT, showcasing its embedding layer, transformer encoder, and multi-layer perceptron (MLP).

Figure 13.

The SignViT architecture, where (*), an additional learnable [class] embedding is added to the patch embeddings to capture global image information. The process starts by dividing image I (H, W, C) into a set of patches, denoted as N, and converting these into sequences of flattened 2D patches. Where H represents the height, W the width of the input image, C the number of channels, and (P, P) the resolution of each patch. The total number of patches [63], N, is determined in Equation (4).

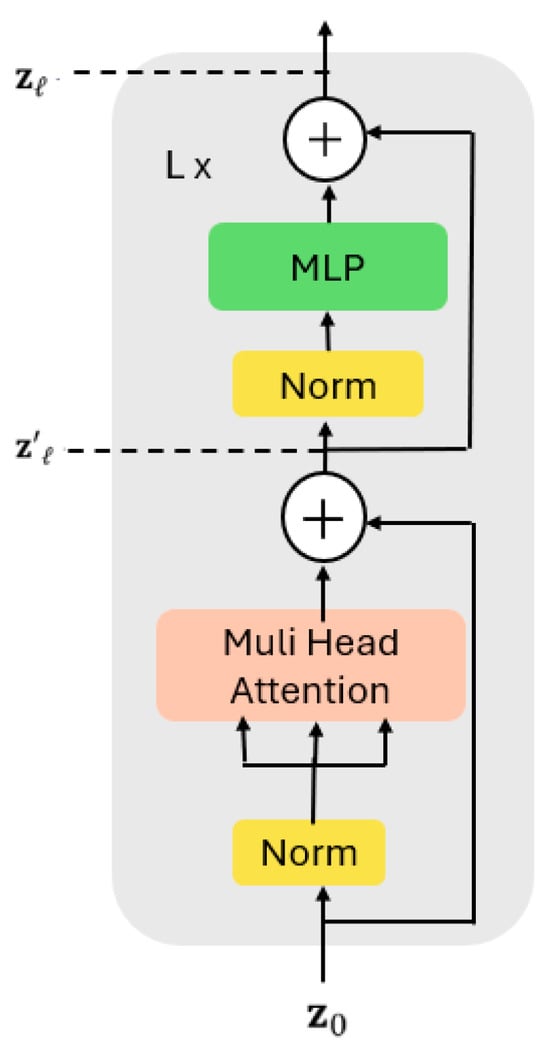

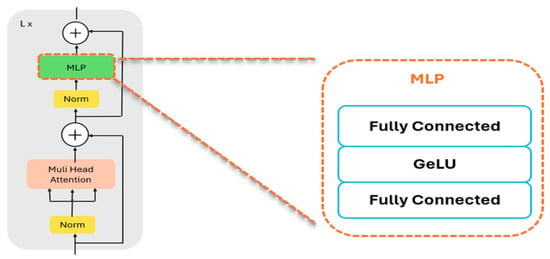

This process effectively converts the image into a sequence of flattened 2D patches, each reshaped into a 1D representation with a shape of (). Splitting the image into patches helps reduce the quadratic computational cost of processing all pixels individually. These flattened patches are then passed through a linear projection layer before being fed into a Transformer. Additionally, a positional embedding tensor (, with a shape of (N, D) is used to encode the positional information of each patch. This embedding generates a spatial representation of the patches, enabling the Transformer to preserve the spatial relationships within the input image while processing the sequence. The final representation is produced by running the encoded image patches through the Transformer encoder. The output is finally classified by the MLP using the sequence’s first token as a basis. The Transformer encoder comprises L identical blocks, with each block having two sublayers: a fully connected feed-forward multi-layer perceptron (MLP) and a multi-head self-attention (MSAH) mechanism, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The architecture of the transformer encoder. Where each encoder layer consists of a Multi-Head Self-Attention block followed by a Feed-Forward Network (MLP), with Layer Normalization and residual (skip) connections. The arrows indicate the flow of data between components and across the L stacked layers of the encoder. denotes the input embedding to the encoder, while and represent intermediate outputs after the attention and MLP sublayers, respectively.

In the encoder layer, the input sequence, denoted as , is received from the preceding layer and initially undergoes layer normalization. This process standardizes the input values across the feature dimension, which aids in reducing training time and improving performance. After normalization, the output is passed through the multi-head self-attention (MHSA) layer, which will be presented below. The multi-layer perceptron (MLP) layer receives the output from the MSA layer after it has been once more normalized. Relative connections, also known as skip connections, are used in the encoder layer to facilitate layer-to-layer information transfer. By avoiding non-linear activation functions, these connections enable gradient flow throughout the network and avoid the vanishing gradient issue. The gradient flow within the encoder layer is described as follows in Equations (5) and (6)

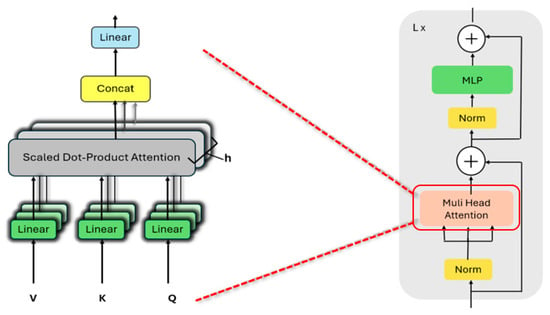

where LN indicates the layer normalization. In addition, the MHSA consists of a concatenation layer, a linear layer, a self-attention mechanism, and a final linear layer, as illustrated in Figure 15 below.

Figure 15.

MHSA architecture. This figure shows how the Multi-Head Attention works and where it is used in the Transformer encoder. On the left, the attention mechanism takes Q (queries), K (keys), and V (values), applies linear projections, computes attention, and combines the outputs. The red dashed arrow shows that this attention block is the same module used in the Transformer encoder layer shown on the right.

Multiple self-attention operations (MSAs) are carried out concurrently according to the number of heads (h). The D-dimensional patch embedding z is multiplied by three weight matrices, Uq, Uk, and Uv, to produce the query (q), key (k), and value (v) matrices for each head. This multiplication is expressed in Equation (7) [63].

Following the projection of the resultant matrices q, k, and v into k subspaces, the weighted sum over all values V is calculated. Each head’s attention weights are derived from the dot product of qi and kj, which represents the relationship between two elements (i, j). The output of this dot product indicates the significance of the patches within the sequence. In particular, the attention weights are obtained by computing the dot product of q and k and then applying the softmax function as follows in Equation (8) [63].

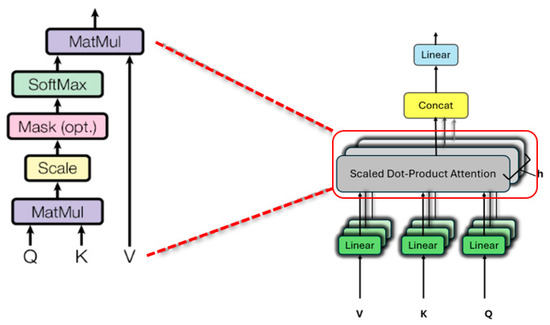

Here, is defined as . The term “scaled dot-product” refers to the use of the key’s dimension , as a scaling factor, which is the primary distinction between standard dot-product operations and the self-attention (SA) dot-product operation. Finally, the value v of each patch embedding vector is multiplied by the softmax output to find the patch with the highest attention score, as presented in Figure 16 and calculated as Equation (9)

Figure 16.

Process of scaled dot-product attention. This figure explains the Scaled Dot-Product Attention mechanism and its role inside the Multi-Head Attention block. On the left, the steps of attention are shown: multiplying queries and keys, scaling, applying an optional mask, softmax, and multiplying by the values. The red dashed arrow indicates that this process corresponds to the Scaled Dot-Product Attention module used inside each attention head on the right.

The self-attention outputs from each head are then concatenated and passed through a single linear layer with a learnable weight matrix Umsa, as shown in Equation (10).

The model can encode more complex features concurrently because each head in the MSA collects data from various angles and positions. Additionally, due to this parallel structure, the computational cost of MSA remains comparable to that of single-head attention. Following the multi-head attention mechanism, the output is normalized and then passed through the MLP for further processing, which comprises two fully connected layers with Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GeLU) activation function, as demonstrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Architecture of a multi-layer perceptron MLP. This figure highlights the Feed-Forward Network (MLP) inside the Transformer encoder layer. As shown on the right, the MLP consists of two fully connected layers with a GeLU activation function in between. The dashed arrow indicates how this MLP block fits into each encoder layer after the Multi-Head Attention and normalization.

In the MLP, the GeLU function plays a crucial role by weighing inputs based on their value rather than their sign, allowing it to estimate complex functions more effectively than the ReLU function due to its ability to handle both positive and negative values with greater curvature. In the final layer of the encoder, the first token of the sequence is selected, and layer normalization is applied to generate the image representation (r). This representation is then passed to a small head, which is a single hidden layer with dimension D = 512, with a sigmoid function, to perform classification.

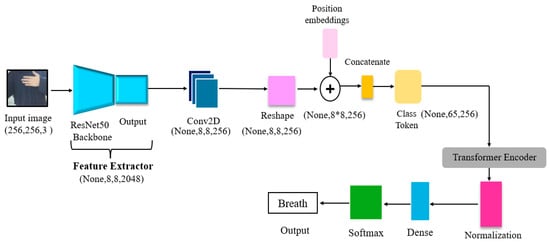

5.6. Approach 5: Architecture of ResNet50ViT

Figure 18 presents our proposed architecture, known as ResNet50ViT. This architecture is a hybrid model that effectively combines the strengths of ResNet50 and ViT for superior image multiclassification performance. While ResNet50, a convolutional neural network, excels in deep feature extraction by leveraging residual connections to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, enabling the extraction of detailed, multi-level features that capture both low-level textures and high-level semantics. Initially, the input image with size (256, 256, 3) is processed by a pre-trained ResNet50 model, where the final classification head, trained on the ImageNet dataset, is removed. This modification repurposes ResNet50 purely as a feature extractor, producing rich feature maps without performing any classification. The output feature map, typically of size (8, 8, 2048). These feature maps are then refined and reduced in dimensionality using a Conv2D layer to be (8, 8, 256), which prepares them for the ViT component by transforming them into patch embeddings. Unlike a standalone ViT, which specializes in global context modeling by treating images as sequences of patches, ResNet50ViT leverages the deep convolutional layers of ResNet50 to extract more complex and informative features. These feature maps are then treated as patches for the ViT component. Then, the patch embeddings are combined with positional encodings, and a custom class token is prepended to the sequence. This sequence is processed through multiple transformer encoder layers that apply self-attention and MLP blocks to capture intricate dependencies between images. In addition, the MLP dimension is equal to 1024. Finally, the enriched class token is passed through a dense layer with a softmax activation to classify the image into one of 92 classes. By integrating ResNet50’s detailed feature extraction capabilities with ViT’s advanced sequence modeling, the ResNet50ViT architecture offers enhanced performance, particularly in tasks that demand detailed image recognition.

Figure 18.

Proposed architecture of ResNet50ViT, where in the notation (None, 8 ∗ 8, 256), the symbol (∗) represents multiplication. For example, 8 ∗ 8 = 64 patches, so the tensor shape becomes (None, 64, 256), where “None” refers to the batch size.

6. The Experimental Setup and Results

6.1. Performance Metrics and Callbacks

To assess the performance of the proposed models, and according to Vujovic [64], we employed evaluation metrics like accuracy and loss were calculated as Equations (11) and (12), that explain how they are classified as true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN).

To optimize the results and mitigate overfitting, we integrated several advanced callbacks, including EarlyStopping [65]. This technique is a regularization technique used to halt the training process when the validation loss plateaus or begins to increase. In addition, Model Checkpoint [66] plays a critical role in preventing the loss of progress due to unexpected interruptions, enabling the resumption of training from the last saved point rather than starting over. We also apply ReduceLROnPlateau [67], which decreases the learning rate when a monitored metric stops improving, which can be beneficial when learning stagnates, and CSVLogger that helps in tracking and analyzing the progress of the model by saving epoch-wise information, such as loss and accuracy, to a CSV file. These techniques played an important role in enhancing model performance, stabilizing training, and ensuring efficient convergence.

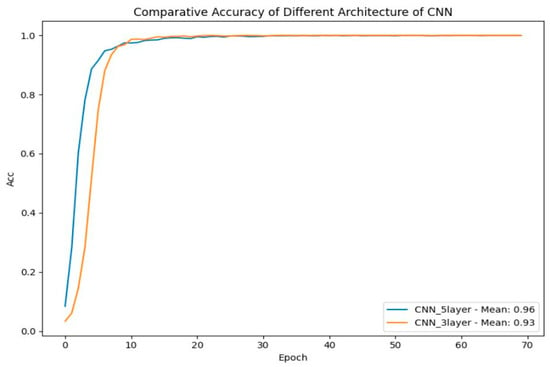

6.2. Results of Custom CNNs

In this experiment, we examine the performance of the six proposals. We assessed both manual and non-manual features for ArSL using the proposed datasets. The dataset ASiL was created using 36 classes, which correspond to 36 static hand signs. We created 50 images for each class, for a total of 1800 images, while a video dataset contains 92 classes, each class contains 50 videos, which means 4600 videos. Initially, we focused on evaluating static gestures for the automatic recognition of sign language. Subsequently, we expanded the experiments to include the evaluation of dynamic signs. Each dataset was split into the training set 75%, validation set 15% and test set 10%. Our procedure started with preprocessing, during which images were preprocessed and filtered as detailed in Section 4. We then fed the preprocessed data into the first architecture, featuring a three-layer design, which is characterized by its simplicity and efficiency in training. It is easier and faster to train. In addition, the model was trained with a batch size of 32. This choice of batch size was recommended by Kandel and Castelli [68], which provides good results. This model achieved a mean accuracy of 93%, with a mean loss of 0.28 as presented in Figure 19. This architecture is particularly well-suited for smaller datasets where overfitting could be a concern. On the other hand, the second model, with its deeper five-layer structure, achieves a mean accuracy of 96%, with a mean loss of 0.24, indicating better overall performance in capturing complex patterns. The inclusion of batch normalization in this architecture helps stabilize the training process, making it more precise in classification tasks, particularly on datasets that require intricate feature extraction. In conclusion, both architectures demonstrate remarkable performance, but given its superior accuracy and enhanced feature extraction capabilities, the five-layer architecture is the preferred baseline choice.

Figure 19.

Comparison of the accuracy of Custom CNNs.

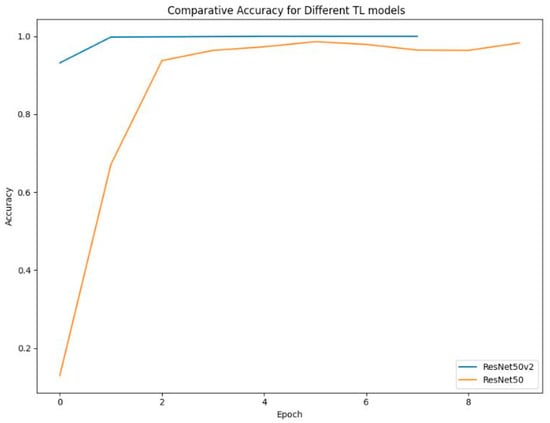

6.3. Results of Transfer Learning Models Modified

The plot below presents a comparison of the accuracy rates for the two transfer learning models over multiple epochs trained on a dataset containing 36 classes: ResNet50 modified and ResNet50V2 modified. ResNet50V2 rapidly achieves high mean accuracy, stabilizing around 99% early, as shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Comparative Accuracy for TL models modified.

However, ResNet50 achieves a steady accuracy of approximately 98% with a smooth learning curve, suggesting consistent and logical training progression. Despite its slightly lower final accuracy, it is known for its architectural efficiency, especially in deeper networks, making it well-suited for large-scale tasks. Additionally, based on some studies, ResNet50 consistently outperforms ResNet50V2 in object recognition tasks. For example, this study [69] compares VGG16, ResNet-50, and ResNet-50v2 in sign language recognition. ResNet-50 was found to be a strong choice, performing competitively against ResNet-50v2, particularly in feature extraction efficiency. Also, in [70], the authors highlight that while ResNet-50v2 offers improvements, ResNet-50 maintains strong accuracy in sign language recognition tasks. Therefore, ResNet50 provides a more balanced and efficient foundation for future improvement.

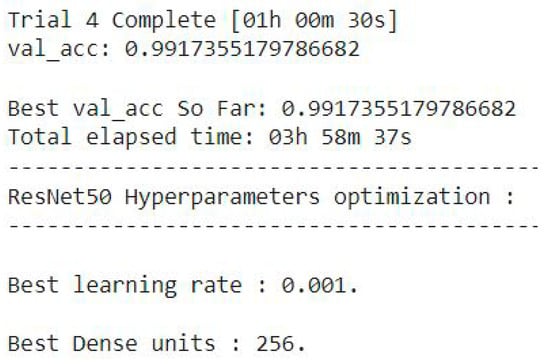

6.4. Results of ResNet50 Fine-Tuned

As shown in Figure 21, the best parameters were identified as a learning rate of 0.001 and 256 dense units. The tuning process yielded a validation accuracy of 99.173% after multiple trials. Following tuning of ResNet50, these optimal hyperparameters were applied, and the last 23 convolutional layers were fine-tuned over 30 epochs. The fine-tuned ResNet50 model demonstrates outstanding performance and stability.

Figure 21.

Optimization of ResNet50 hyperparameters.

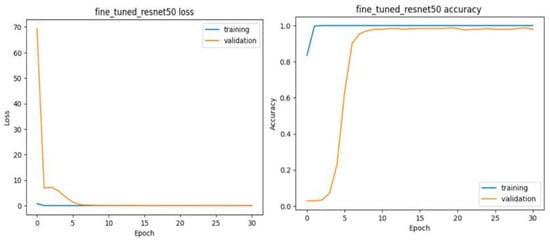

As shown in Figure 22, both training and validation accuracy increased sharply in the early epoch, with training accuracy nearing 100% and validation accuracy stabilizing at around 9% by epoch 8. This indicates strong generalization and consistent performance throughout training. Training loss starts low and drops to near-zero (0.0007) by epoch 5, while validation loss, initially higher, decreases steeply and stabilizes close to zero (0.05). The smooth and stable accuracy and loss curves, free from fluctuations, suggest controlled learning without overfitting or instability. The fine-tuning process, combined with the selected hyperparameters, proves highly effective, enabling the model to achieve perfect accuracy and rapid convergence, demonstrating optimal performance on the sign recognition task.

Figure 22.

Results of ResNet50 fine-tuned.

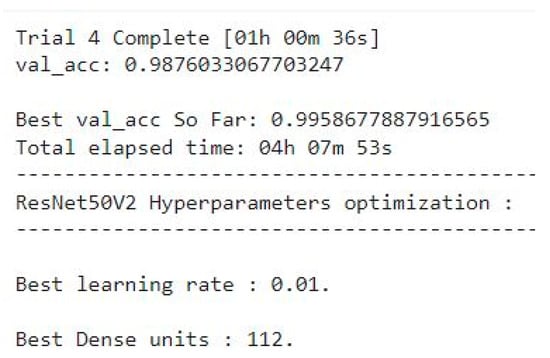

6.5. Results of ResNet50V2 Tuned

The optimal hyperparameters for ResNet50V2 were identified through tuning, yielding a learning rate of 0.01 and 112 units in the dense layer, as shown in Figure 23. This configuration achieved a validation accuracy of 99.586% after multiple trials, with the full optimization process completed in approximately 4 h and 7 min.

Figure 23.

Optimization of ResNet50v2 hyperparameters.

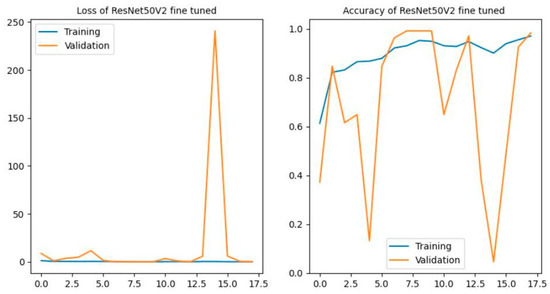

Figure 24 below illustrates the performance of a fine-tuned ResNet50V2 model, where the last 50 convolutional layers were adjusted. The training loss remains consistently low, reaching around 0.14 by the 10th epoch, while training accuracy steadily increases to near-perfect levels of 95.23% by the same epoch, indicating effective learning on the training set. After the 12th epoch, the validation loss spikes sharply, and validation accuracy fluctuates drastically, ranging from nearly 98% to almost 0.045. This stark divergence between training and validation performance strongly suggests overfitting, where the model performs well on training data but fails to generalize to unseen data. The instability in validation metrics is likely due to the high learning rate used during the fine-tuning process. The large variance in validation accuracy and the sharp increase in validation loss highlight the model’s instability. While fine-tuning improved training performance, the poor validation results indicate a lack of generalization. To address this, regularization techniques such as increasing dropout rates and reducing the learning rate could help mitigate overfitting and enhance the model’s stability and overall performance.

Figure 24.

Results of ResNet50V2 fine-tuned.

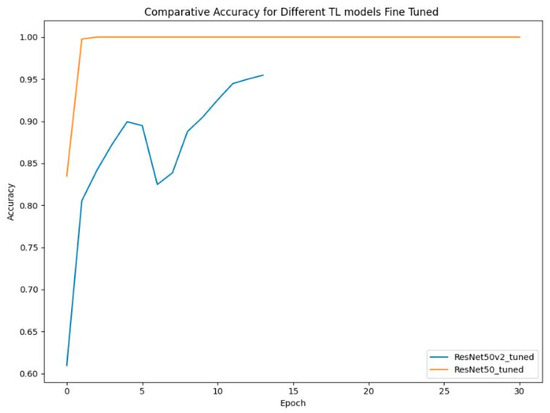

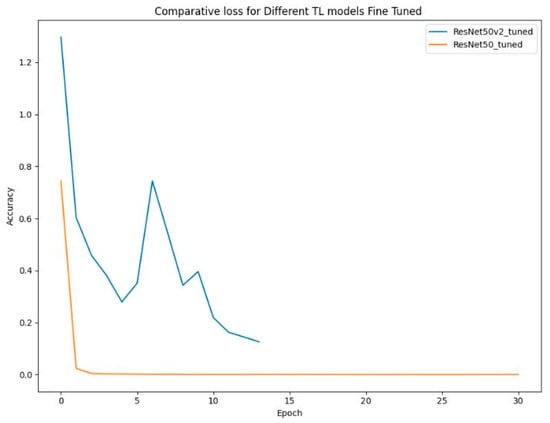

A comparative analysis of the fine-tuned ResNet50 and ResNet50V2 models over 30 epochs reveals notable differences in their performance. As presented in Figure 25. ResNet50 demonstrates exceptional learning speed, reaching perfect mean accuracy (99%) by the 5th epoch and maintaining stability throughout training. Moreover, it achieved a mean loss of around 0.03, meaning efficient learning with a very low error rate. ResNet50V2 performs well but achieves slightly lower accuracy than ResNet50, stabilizing at around 90% after 10 epochs. Its loss value stabilizes at 0.35 as presented in Figure 26. Although higher than ResNet50’s, this value still indicates good learning efficiency. In terms of stability, ResNet50 demonstrates consistent accuracy and low loss. Learning speed further differentiates the models: ResNet50 achieves optimal accuracy fastest, followed by ResNet50V2. Overall, ResNet50 emerges as the optimal model, excelling in accuracy, stability, and learning speed with minimal loss, making it the best choice for this task.

Figure 25.

Comparative accuracy of fine-tuned models.

Figure 26.

Comparative loss of fine-tuned models.

6.6. Results of SignViT

The dataset that we utilized for training contains over 13,800 key frames of 92 unique classes in ArSL. The data was split into three, of which 10,488 samples were selected for training,1932 samples for validation, and to assess the performance of the trained model, a testing dataset of 1380 samples was used. To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, this part discusses the hyperparameter settings as shown in Table 4 and the effectiveness of the proposed regularization methods. The acquired image’s dimensions are set to H = 256 and W = 256. Since the inputs consist of RGB images, there are three channels (C = 3). The ‘Base’ variant (ViT-B/32) with patch size p = 32 is used for the ViT model. Because patch size 16 × 16 requires more computation due to the longer sequence, patch size 32 × 32 is selected. With these settings, the number of patches is . The MSA consists of L, which is the number of encoder layers = 8 encoder layers, and k, the number of heads = 8 heads in each layer. In addition, the MLP dimension is equal to 2048.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters of SignViT.

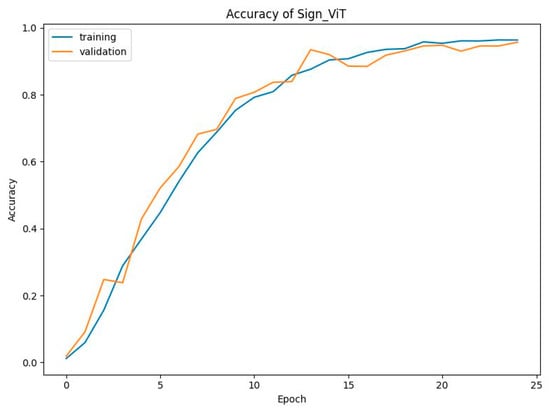

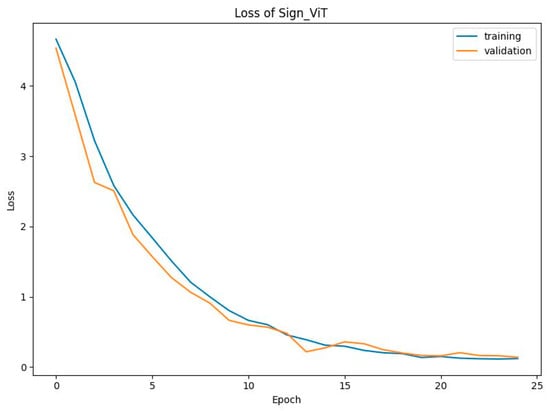

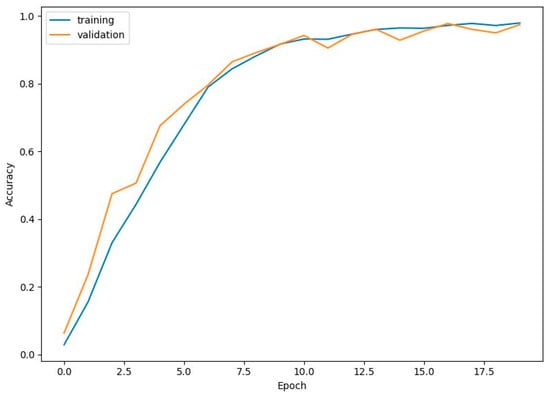

Figure 27 shows that SignViT starts with an initial accuracy of around 10% for both training and validation, showing steady improvement up to epoch 10, where the training accuracy reaches approximately 80% and 80.72% for validation accuracy. From there, the model continues improving, with both the training and validation accuracy converging to about 97% by epoch 25, reflecting strong convergence and high performance. The loss curve reveals that the initial loss is quite high, around 4.5, for both training and testing sets. As presented in Figure 28, there is a sharp decline in loss values as the model learns, dropping below 0.66 by epoch 10 for training loss and 0.59 for validation loss. This downward trend continues, and by epoch 25, the loss stabilizes around 0.11 for both sets, indicating an effective reduction in prediction errors. These results demonstrate the robustness and efficiency of the SignViT model. The close alignment between training and validation accuracy and loss curves suggests minimal overfitting, with the model generalizing well across unseen data. The steady improvement in accuracy and sharp reduction in loss show that SignViT successfully learns from scratch, with strong final performance and the potential for sign recognition.

Figure 27.

Accuracy of the SignViT model.

Figure 28.

Loss of SignViT model.

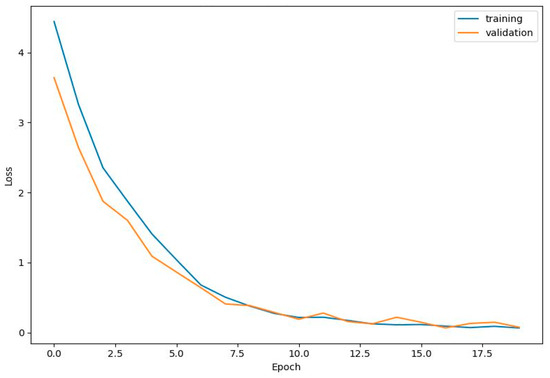

Additional data was incorporated to illustrate the impact of increased data on enhancing the model’s performance. The training dataset comprises 13,800 key frames to 23,000 key frames representing 92 distinct ArSL classes, divided into 17,480 samples for training, 3220 for validation, and 2300 for testing. The SignViT model’s performance was evaluated at 25 epochs. Figure 29 shows consistent improvement, with training accuracy rising from near zero to 95% by epoch 10 and stabilizing just under 98% by epoch 18. Validation accuracy closely follows, indicating effective generalization with minimal divergence. Early stopping was applied at epoch 18. Figure 30 presents a rapid decline in both training and validation loss, starting from 4.5 and stabilizing around 0.1 at epoch 10, with minimal fluctuations thereafter. This parallel decrease and the low gap between curves suggest efficient learning and no overfitting. Overall, the SignViT model exhibits robust performance with increased data, showing rapid learning in the early epochs, followed by stabilization in both accuracy and loss, achieving optimal results from epoch 10 onward, effectively leveraging the dataset without overfitting.

Figure 29.

Accuracy of SignViT with increased data.

Figure 30.

Loss of SignViT with increased data.

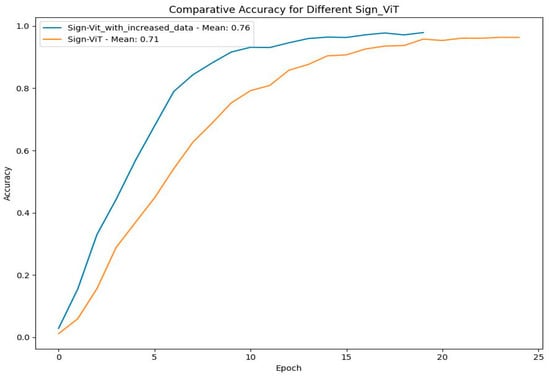

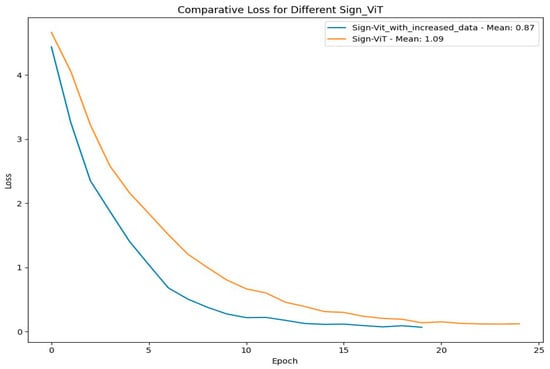

The comparison of the SignViT model trained on two dataset sizes highlights key differences in performance, stability, and convergence over 25 epochs. Figure 31 shows that the enhanced model attained a mean accuracy of 76%, surpassing the standard model’s 71%. Moreover, the use of a larger dataset yielded smoother accuracy and loss trajectories, reflecting enhanced training stability. The model trained with additional data demonstrates superior performance, achieving a mean loss of 0.87 compared to 1.09 for the standard model, as shown in Figure 32, indicating faster and more stable convergence.

Figure 31.

Comparative accuracy for SignViT with different-sized datasets.

Figure 32.

Comparative loss for SignViT with different-sized datasets.

Overall, the model with increased data achieves optimal performance faster, maintains consistent trends, and generalizes better. In contrast, the SignViT model requires more epochs to reach close accuracy and exhibits greater instability, particularly in validation metrics. These findings emphasize the critical role of data size in improving model performance, stability, and reliability, especially for tasks like sign recognition, where consistent performance on unseen data is essential.

6.7. Results of ResNet50ViT

The dataset used for training over 25 epochs consists of over 13,800 key frames from 92 ArSL classes, divided into 10,488 samples for training, 1932 samples for validation, and 1380 samples for testing. To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, this section discusses the hyperparameter settings as presented in Table 5 and the effectiveness of the proposed regularization methods. The input image has dimensions of H = 256 and W = 256. Three channels (C = 3) are present because the inputs are RGB images. The ‘Base’ variant (ViT-B/32) with patch size P = 32 is used for the ViT component. Each layer of the MSA has k = 6 heads and L = 6 encoder layers.

Table 5.

Hyperparameters for ResNet50ViT.

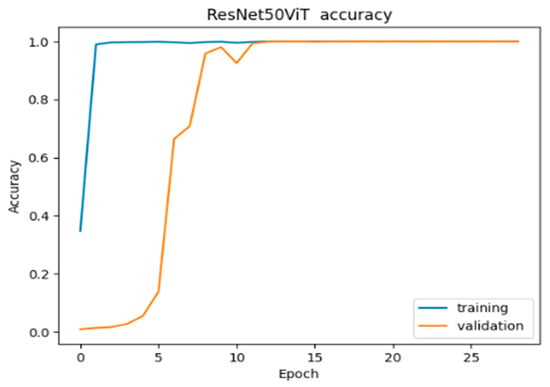

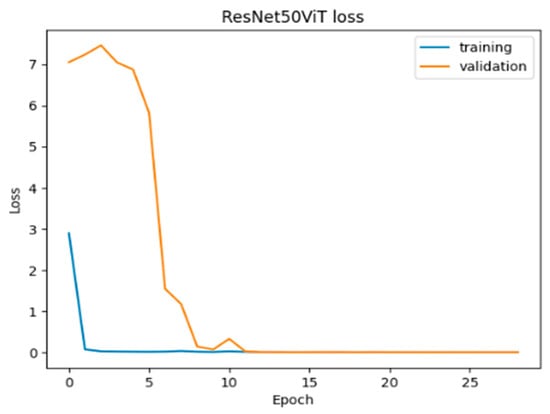

Our innovative model demonstrates robust performance, as presented in Figure 33, training accuracy rapidly reaching 99.76% in the early epoch and stabilizing at 100% by epoch 12. Validation accuracy follows a sharp upward trend, stabilizing at 99.92% after epoch 8, indicating a strong generalization with minimal variability.

Figure 33.

Accuracy of ResNet50ViT.

Regarding loss, Figure 34 shows a rapid decline for both training and validation loss, with training loss dropping to near zero (0.00019) by epoch 10 and validation loss stabilizing at 0.0010. The close alignment between training and validation loss curves suggests effective learning without overfitting. Both accuracy and loss stabilize by epoch 10, reflecting a well-trained model with balanced bias and variance. The model leverages ResNet50 for feature extraction and ViT for capturing complex relationships, achieving good generalization and consistent performance across epochs. This convergence highlights the model’s effectiveness in learning key dataset features without underfitting or overfitting.

Figure 34.

Loss of ResNet50ViT.

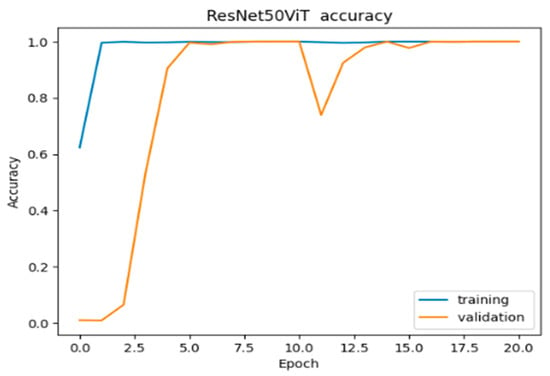

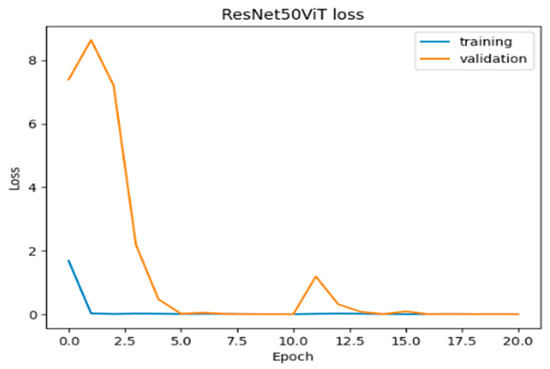

To demonstrate how increased data enhances the performance of ResNet50-ViT, additional data was added to the training process, which comprises over 23,000 key frames representing 92 distinct ArSL classes, divided into 17,480 samples for training, 3220 for validation, and 2300 for testing. ResNet50-ViT model, trained with more data, demonstrates strong performance with some key differences. As shown in Figure 35, training accuracy remains consistently high, reaching 99.69% by the 4th epoch and stabilizing near 100%, indicating efficient learning with minimal variability. Validation accuracy starts lower but rises rapidly after epoch 2, converging with training accuracy by epoch 5. A minor drop around epoch 10 is quickly corrected, with validation accuracy stabilizing at 99.90%, reflecting improved generalization due to the additional data.

Figure 35.

Accuracy of ResNet50ViT with increased data.

In terms of loss (Figure 36), training loss drops sharply to near-zero (0.0053) by epoch 5 and stabilizes at 0.0003, while validation loss, initially high (~7), also decreases significantly, nearing zero by epoch 5. Overall, the model shows high accuracy, low loss, and minimal divergence between training and validation metrics, indicating effective learning and generalization. The brief fluctuation around epoch 10 highlights a minor learning challenge, but the model’s rapid recovery demonstrates its ability to handle the larger dataset without significant overfitting or underfitting, maintaining strong performance and stability.

Figure 36.

Loss of ResNet50ViT with increased data.

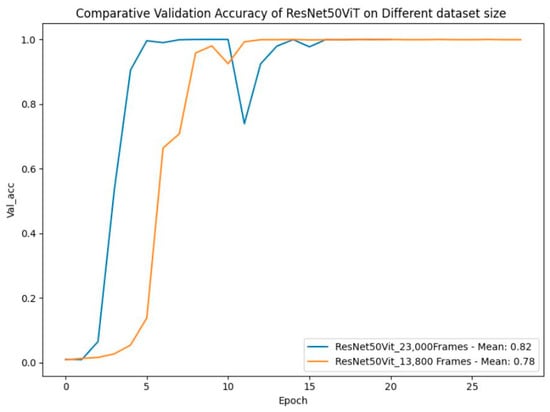

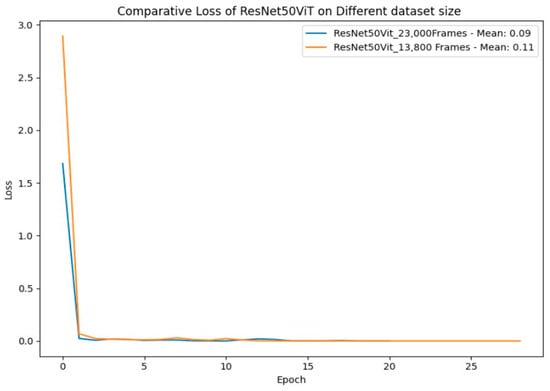

The comparison of ResNet50ViT models trained on 13,800 and 23,000 key frames reveals key performance differences, particularly in validation accuracy and loss. Both models achieve near-perfect training accuracy (98%) early and remain stable, showing effective learning across dataset sizes. However, the model trained on 23,000 frames experiences a brief dip in validation accuracy and a spike in validation loss around the 10th epoch. Despite this, it stabilizes with a higher mean validation accuracy (82%) compared to 78% for the smaller dataset model (Figure 37).

Figure 37.

Comparative validation accuracy of ResNet50ViT on different dataset sizes.

In terms of loss (Figure 38), the larger dataset model stabilizes at a lower value (0.09) versus 0.11 for the smaller dataset, suggesting better generalization despite initial challenges. The smaller dataset model converges more smoothly but may lack the capacity to handle complex data. Neither model shows significant overfitting, as validation accuracy closely follows training accuracy, and losses remain low after convergence. However, the larger dataset model exhibits slightly more variability, reflecting the added complexity of the data.

Figure 38.

Comparative loss for ResNet50ViT on different dataset sizes.

In conclusion, while both models perform well but ResNet50ViT trained on 23,000 key frames ultimately proves to be the superior choice and stands out as the best option for tackling complex data in ArSLR.

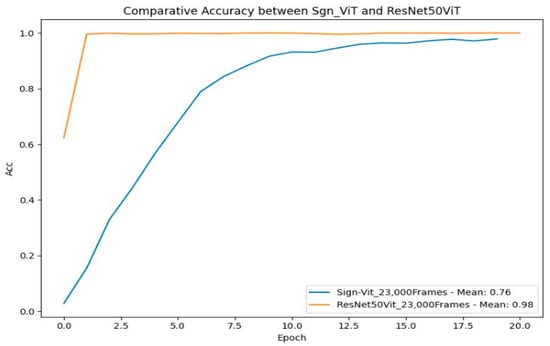

6.8. Comparison of SignViT and ResNet50ViT

For SLR, selecting between Sign-ViT and ResNet50ViT hinges on key factors such as accuracy, stability, and learning speed. As shown in Figure 39, ResNet50ViT outperforms SignViT. The hybrid ResNet50ViT architecture achieves steep accuracy gains within the initial training epochs, stabilizing at a near-perfect mean accuracy of 98%. This rapid convergence underscores its methodological synergy: ResNet50’s robust feature extraction capabilities coupled with ViT classification prowess. While early performance plateaus suggest architectural limitations in scalability, the model maintains exceptional operational stability, making it ideal for time-sensitive deployments.

Figure 39.

Comparative accuracy between SignViT and ResNet50ViT.

In contrast, SignViT achieves a mean accuracy of 76% with incremental improvements over extended training. Though this slower progression hints at untapped long-term learning potential, its inferior convergence rate and subpar final performance render it impractical for real-world applications prioritizing speed and reliability.

In conclusion, ResNet50ViT’s superior accuracy, rapid learning dynamics, and sustained stability position as the optimal solution for ArSL tasks, particularly where computational efficiency and real-time performance are paramount.

6.9. Comparison with Other Model Performances

This paper provides a detailed comparison of various models. Beginning with baseline CNN models (CNN 3 Layers and CNN 5 Layers) trained on a 36-class dataset. As shown in Table 6, both models achieved 96% accuracy with moderate loss values. Subsequent evaluation of transfer learning models ResNet50 and ResNet50V2 revealed distinct performance trends. For the 36-class static dataset, the ResNet50 model, fine-tuned using a CNN-based approach, achieved an outstanding test accuracy of 98.03%, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling a smaller set of classes. On the other hand, Table 7 provides a summary of the results for models trained on the 92-class dataset. The hybrid ResNet50ViT architecture, integrating a pre-trained ResNet-50 backbone with a ViT component, delivered exceptional performance, achieving a remarkable test accuracy of 99.86%. This highlights the superior capability of the ResNet50ViT architecture in managing larger and more diverse datasets, showcasing its potential for advanced sign language recognition tasks.

Table 6.

Summary of performance of proposed models on the static dataset.

Table 7.

Summary of performance of proposed models on the dynamic dataset.

In conclusion, our hybrid model ResNet50ViT stands out as the top performer, combining ResNet50’s feature extraction strengths with ViT’s capabilities to achieve high accuracy and stability. The results highlight the effectiveness of transfer learning and the potential of integrating CNNs with transformers for superior performance in sign recognition tasks. The final part of the evaluation involves comparing our system with the most relevant existing approaches in the literature. Our comparison with other existing systems in the literature is constrained by the lack of a directly comparable dataset.