Extracting Metasystem: A Novel Paradigm to Perceive Complex Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

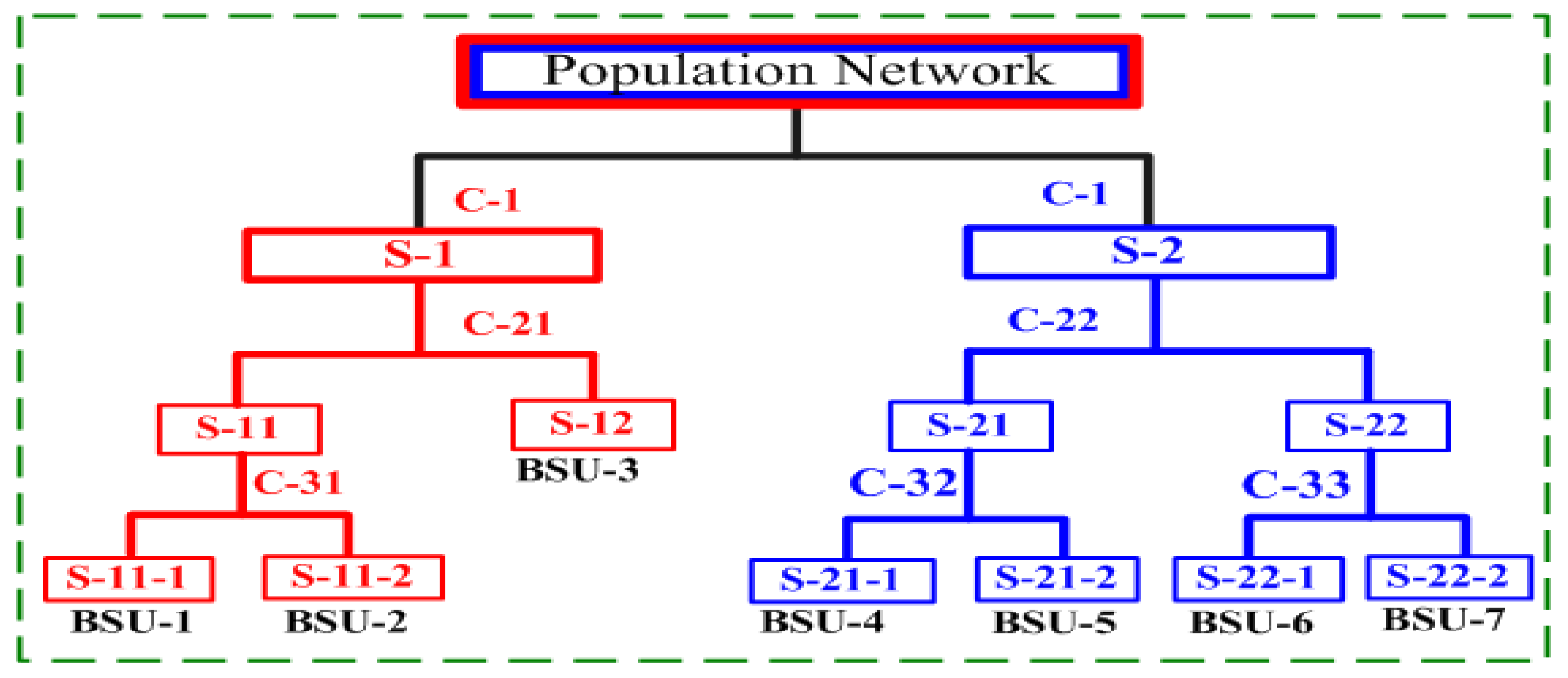

2.1. Stage 1: Partitioning

- (1)

- Given a graph and its Laplacian matrix , the eigenvector–eigenvalue pairs of are solved, and the eigenvalues are labeled in ascending order: . The second eigenvector (the Fiedler vector [29]) of the Laplacian eigenvalue set is employed to partition the original system into 2-way cuts.

- (2)

- The second eigenvector is decomposed into two subsets, with its median as the dividing line. Correspondingly, all nodes in the original system are decomposed into left and right subgraphs following the one-to-one correspondence between eigenvectors and nodes.

- (3)

- The modularity [30] of the partitioned subgraphs is estimated to determine whether further partitioning is required. Specifically, if the modularity is below a predefined threshold (critical value = 0.4), it indicates the original system is sufficiently decoupled; otherwise, the above process will continue.

2.2. Stage-2: Sampling

- (1)

- The PageRank of each node in a BSU is estimated, and the node with the maximum value is selected as the initial seed to guide the sampler. In terms of the implication of PageRank, we can conclude that the node with the maximum value certainly positions at the core area of the BSU.

- (2)

- The DRSM is applied to select appropriate edges within the BSUs from the core toward the periphery. All selected samples are then incorporated to construct a preliminary metasystem, an intermediate version of the final metasystem.

- (3)

- To capture the overall structure within a BSU, the DRSM terminates as soon as all the edges within the BSU are visited at least once. This is necessary because the elements belonging to a metasystem may be distributed across both the core and the periphery areas.

2.3. Stage 3: Optimizing

- (1)

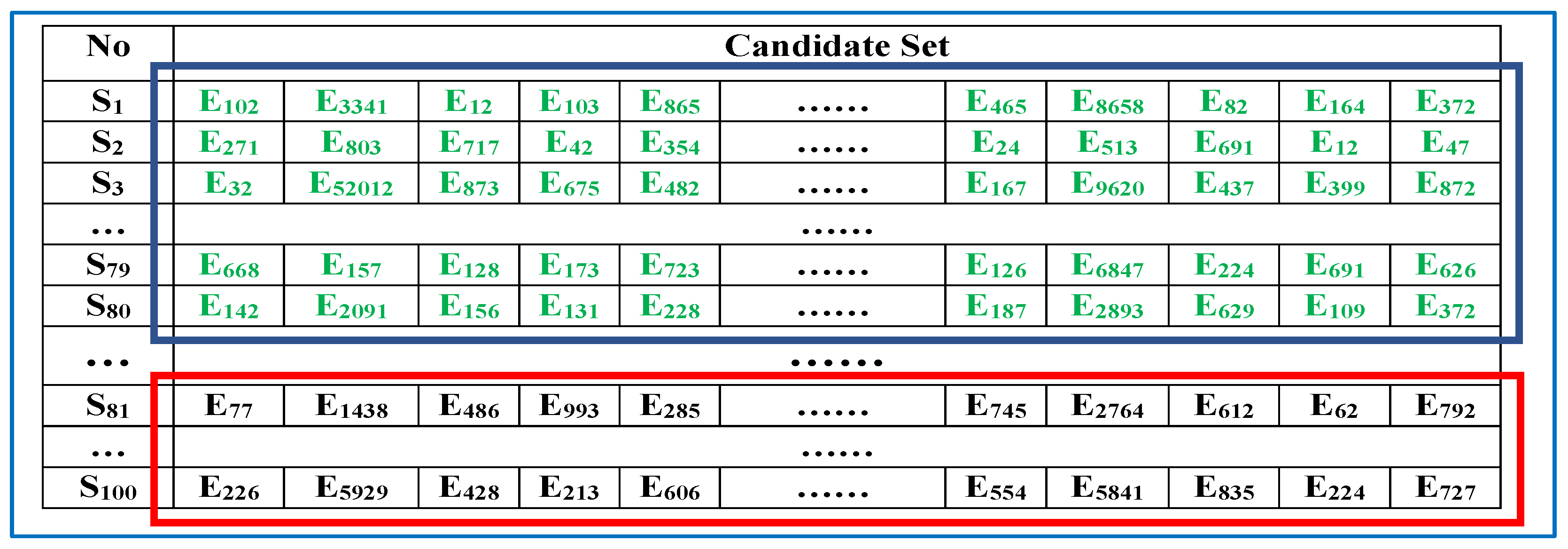

- Selection operator: Figure 2 describes the selection operator of the GA, in which S1–S100 represent all the edges in . The elements in the blue frame (S1–S80) represent the retained sequences, whereas those in the red frame (S81–S100) represent the new sequences selected from the candidate set to replace the eliminated sequences within . The rule of the selection operator is fairly straightforward: the top 80% of the sequences in are preserved, and the others are replaced by new sequences from .

- (2)

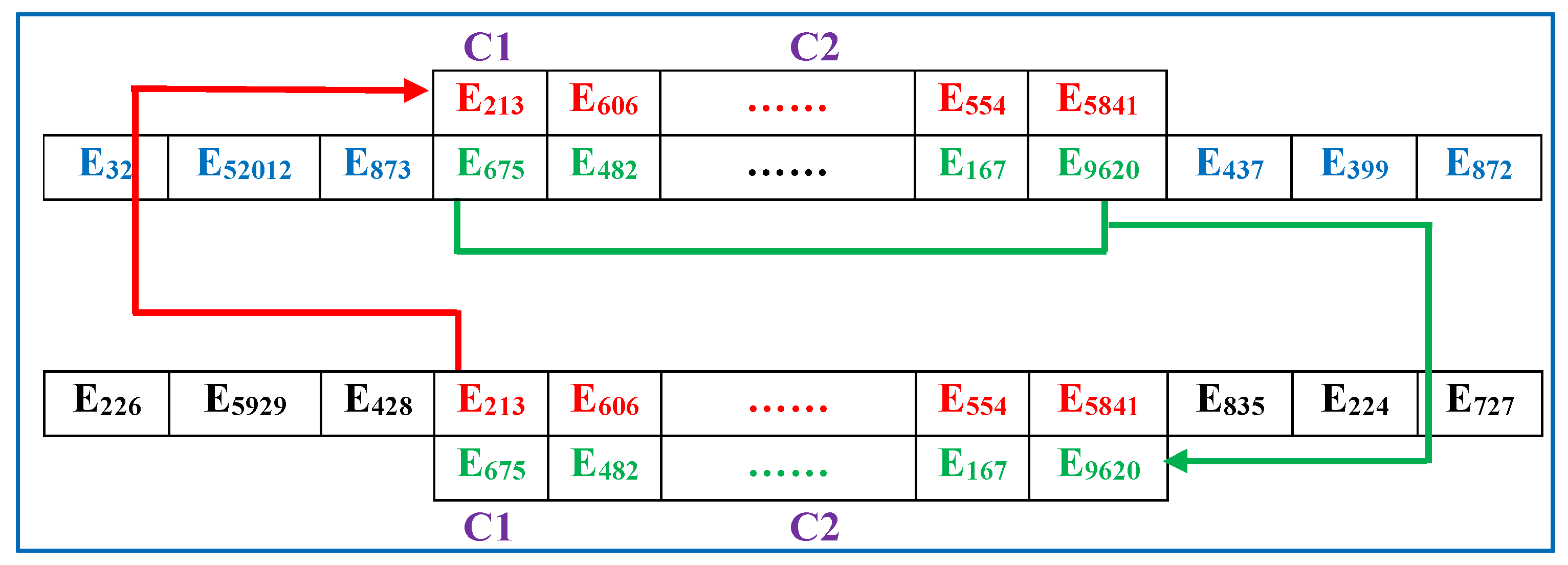

- Crossover operator: Any two sequences in are randomly selected, and a classic crossover approach, the partially mapped crossover [32], is applied to generate two new sequences to replace the original sequences.

- (3)

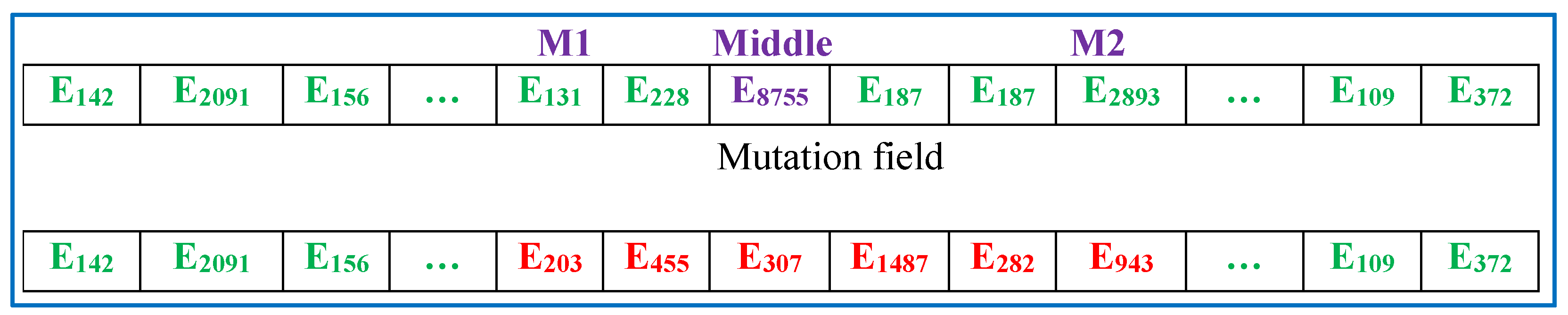

- Mutation operator: The mutation operator employs a common method, the simple mutation method. Specifically, elements randomly selected within sequence are replaced by an equal number of elements from the candidate set . In Figure 4, two random numbers and () are first generated as control parameters to set the mutation field. Then, the elements within the mutation field in sequence are replaced by new elements from the original system not chosen in the previous steps. Like the crossover operator, the mutation operator has a low incidence of validity of 3–5%. Moreover, the total number of mutation bits is finite, up to 50% of the entire length of the sequence .

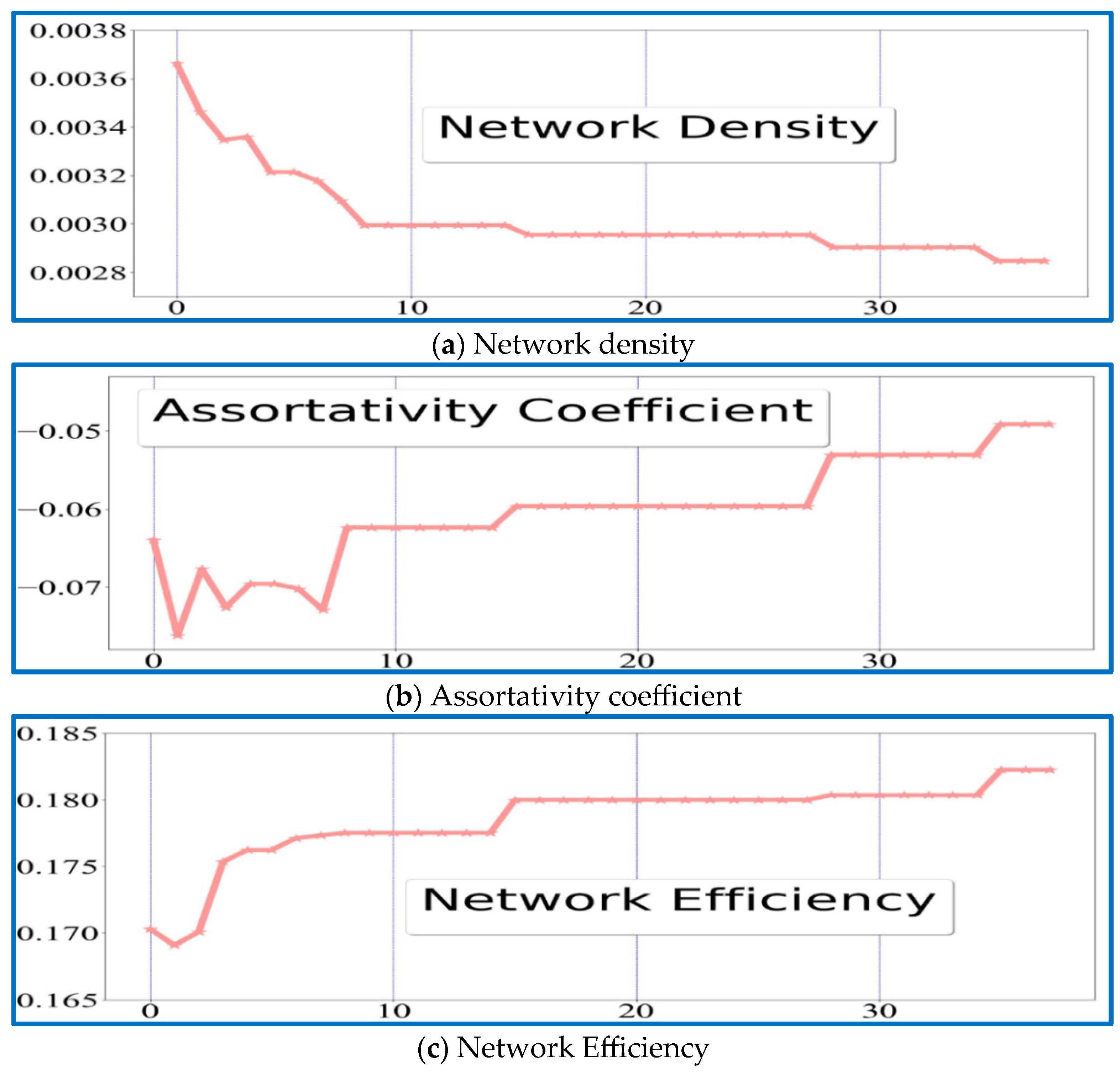

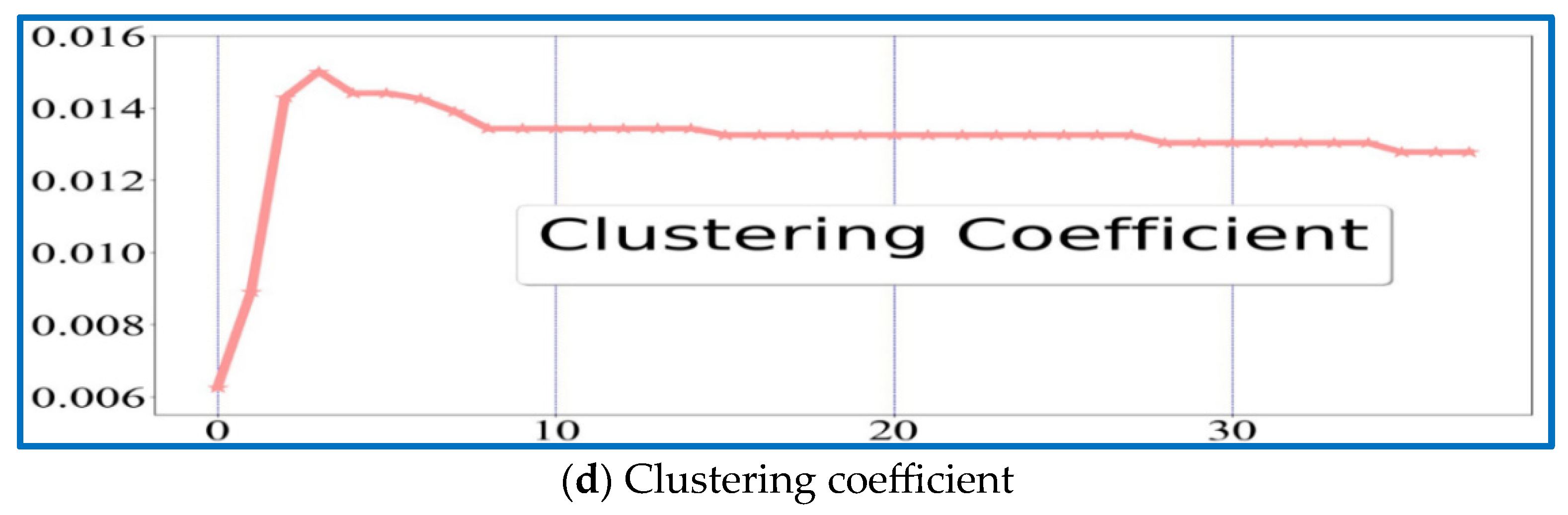

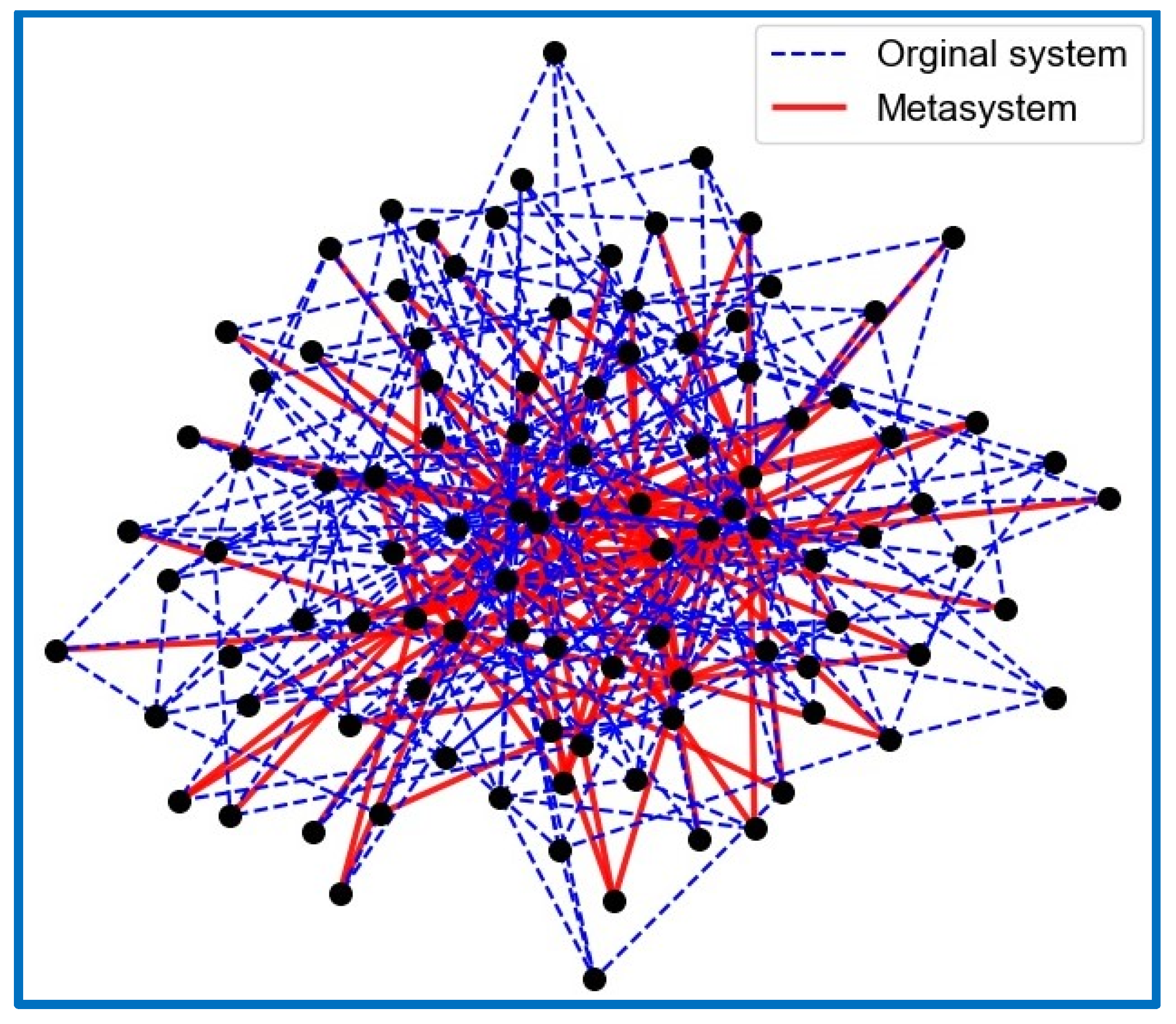

3. Results

4. Discussion

- (1)

- key points in stage 1

- (2)

- key points in stage 2

| Algorithm 1 DRSM |

| Input: Basic sampling units |

| 1: // is the exit criterion of the DRSM While () { 2: //Select a node with maximum PageRank as an initial seed. IS = GetSeed () 3: //Select a candidate element using the original MHRW 4: //If is rejected, delayed rejection is launched. one of the immediate neighbors upon the current candidate rejected will be proposed as a new candidate with the following new probability 5: //The edges or nodes unselected in previous steps will be add into the preliminarily metasystem PMe = Add(elements) } |

| Output: A preliminary metasystem |

- (3)

- key points in stage 3

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perez, I.A.; Ben Porath, D.; La Rocca, C.E.; Braunstein, L.A.; Havlin, S. Critical behavior of cascading failures in overloaded networks. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 034302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, A.S.C.; Nakas, G.A.; Papadopoulos, P.N. A Method for Variance-Based Sensitivity Analysis of Cascading Failures. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, B.-C.; Zhang, H. Asymptotically Optimal Distributed Control for Linear–Quadratic Mean Field Social Systems with Heterogeneous Agents. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2025, 70, 3197–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Xu, Y.; Guo, S.; Tian, Y.; Sun, P. Quasi-critical dynamics in large-scale social systems regulated by sudden events. Chaos 2024, 34, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Valencia, I.; Kocabas, A.; Rodriguez-Navas, C.; Miloushev, V.Z.; González-Rodríguez, M.; Lees, H.; Henry, K.E.; Vaynshteyn, J.; Longo, V.; Deh, K.; et al. Imaging brain glucose metabolism in vivo reveals propionate as a major anaplerotic substrate in pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1394–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Hodder, T.; Wang, W.; Myers, C.L.; Yilmaz, L.S.; Walhout, A.J.M. Systems-level design principles of metabolic rewiring in an animal. Nature 2025, 640, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, D.; Xu, S.; Sandberg, T.E.; Brunk, E.; Hefner, Y.; Szubin, R.; Feist, A.M.; Palsson, B.O. Evolution of gene knockout strains of E. coli reveal regulatory architectures governed by metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlechte, J.; Zucoloto, A.Z.; Yu, I.-L.; Doig, C.J.; Dunbar, M.J.; McCoy, K.D.; McDonald, B. Dysbiosis of a microbiota–immune metasystem in critical illness is associated with nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, N.; Erős, T.; Heino, J.; Singer, G.; Jähnig, S.C.; Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Bonada, N.; Sarremejane, R.; Mykrä, H.; Sandin, L.; et al. From meta-system theory to the sustainable management of rivers in the Anthropocene. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 20, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.-Y.; Liu, X.-J.; Peng, Y.-Q.; Zhang, D.-S.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Xiao, J.-J. On-chip integrated metasystem for spin-dependent multi-channel color holography. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 3114–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messager, M.L.; Olden, J.D.; Tonkin, J.D.; Stubbington, R.; Rogosch, J.S.; Busch, M.H.; Little, C.J.; Walters, A.W.; Atkinson, C.L.; Shanafield, M.; et al. A metasystem approach to designing environmental flows. BioScience 2023, 73, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolskaya, M.; Madzhuga, A.; Babieva, N.; Khvostunov, K.; Moskvina, A.; Abdullina, L.; Kanbekova, R.; Salimova, R.; Golovneva, E. The effect of personal health on the formation of human capital: A metasystem approach. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 2019, 8, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, P.F. Metasystem Pathologies in Complex System Governance. Complex System Governance: Theory and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 241–282. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, D.; Li, Q.; Lei, Y.; Shen, X.; Qian, M.; Zhang, C. Extreme vulnerability of high-order organization in complex networks. Phys. Lett. A 2021, 424, 127829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Kaddoum, G. Enhancing Resilience Against Jamming Attacks: A Cooperative Anti-Jamming Method Using Direction Estimation. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2025, 73, 12696–12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buede, D.M.; Miller, W.D. The Engineering Design of Systems: Models and Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Patra, K.L. On the super graphs and reduced super graphs of some finite groups. Discret. Math. 2024, 347, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzeha, A.; Ashrafia, A.R. Spectrum and L-spectrum of the power graph and its main super graph for certain finite groups. Filomat 2017, 31, 5323–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.N.; Siggia, E.D.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Self-organization of stem cells into embryos: A window on early mammalian development. Science 2019, 364, 948–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, J. Robust Controller Design for Robot Joint Motor Modules Based on Dynamical Model. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artur, P.D.; Parter, M. Graph sparsification for derandomizing massively parallel computation with low space. ACM Trans. Algorithms 2021, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Robledo, A.; Diaz-Perez, A.; Morales-Luna, G. Characterization and coarsening of autonomous system networks: Measuring and simplifying the internet. In Advanced Methods for Complex Network Analysis; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 148–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ubaru, S.; Saad, Y. Sampling and multilevel coarsening algorithms for fast matrix approximations. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 2019, 26, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, S. A unified framework for optimization-based graph coarsening. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas, A.; Vandergheynst, P. Spectrally approximating large graphs with smaller graphs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; PMLR: Westminster, UK, 2018; pp. 3237–3246. [Google Scholar]

- Bick, C.; Gross, E.; Harrington, H.A.; Schaub, M.T. What are higher-order networks? SIAM Rev. 2023, 65, 686–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.; Cencetti, G.; Battiston, F. Multiorder Laplacian for synchronization in higher-order networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 033410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovász, L. Large Networks and Graph Limits; American Mathematical Society (AMS): Providence, RI, USA, 2012; Volume 60. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, M. Algebraic connectivity of graphs. Czechoslov. Math. J. 1973, 23, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8577–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanini, D.; Morosi, G.; Tarasco, S.; Mira, A. Delayed rejection variational Monte Carlo. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121, 3446–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavai, G.; Geetha, T.V. A Survey on Crossover Operators. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 49, 72.1–72.43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noldus, R.; Van Mieghem, P. Assortativity in complex networks. J. Complex Netw. 2015, 3, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szemerédi, E. Regular Partitions of Graphs; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A. Szemerédi’s Regularity Lemma for Matrices and Sparse Graphs. Comb. Probab. Comput. 2011, 20, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buluç, A.; Meyerhenke, H.; Safro, I.; Sanders, P.; Schulz, C. Recent Advances in Graph Partitioning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X. A survey of sampling method for social media embeddedness relationship. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Maiorino, E.; Halu, A.; Glass, K.; Prasad, R.B.; Loscalzo, J.; Gao, J.; Sharma, A. Robustness and lethality in multilayer biological molecular networks. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valejo, A.; Ferreira, V.; Fabbri, R.; de Oliveira, M.C.F.; Lopes, A.d.A. A Critical Survey of the Multilevel Method in Complex Networks. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Abbass, H.A.; Tan, K.C. Evolutionary Computation and Complex Networks; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yam, Y. From big data to important information. Complexity 2016, 21, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yam, Y. A mathematical theory of strong emergence using multiscale variety. Complexity 2004, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yam, Y. Multiscale complexity-entropy. Adv. Complex Syst. 2004, 7, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 | I5 | I6 | I7 | I8 | I9 | I10 | I11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactivity | Connectivity | Aggregation | |||||||||

| Original System | −0.0493 | 13.95 | 0.0071 | 0.026 | 16 | 10 | 6.096 | 0.164 | 0.0145 | 0.0102 | 10.936 |

| Metasystem | −0.0445 | 2.88 | 0.00284 | 0.017 | 32 | 18 | 12 | 0.090 | 0.0064 | 0.0048 | 10.025 |

| I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 | I5 | I6 | I7 | I8 | I9 | I10 | I11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactivity | Connectivity | Aggregation | |||||||||

| Original System | 0.00038 | 57.59 | 0.00477 | 0.041 | 44 | 35 | 31 | 0.03419 | 0.004347 | 0.00435 | 23.885 |

| Metasystem | 0.00019 | 10.95 | 0.00119 | 0.078 | 87 | 63 | 47 | 0.02553 | 0.002457 | 0.00258 | 21.913 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Cui, Y. Extracting Metasystem: A Novel Paradigm to Perceive Complex Systems. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010036

Li X, Cui Y. Extracting Metasystem: A Novel Paradigm to Perceive Complex Systems. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xue, and Ying’an Cui. 2026. "Extracting Metasystem: A Novel Paradigm to Perceive Complex Systems" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010036

APA StyleLi, X., & Cui, Y. (2026). Extracting Metasystem: A Novel Paradigm to Perceive Complex Systems. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010036