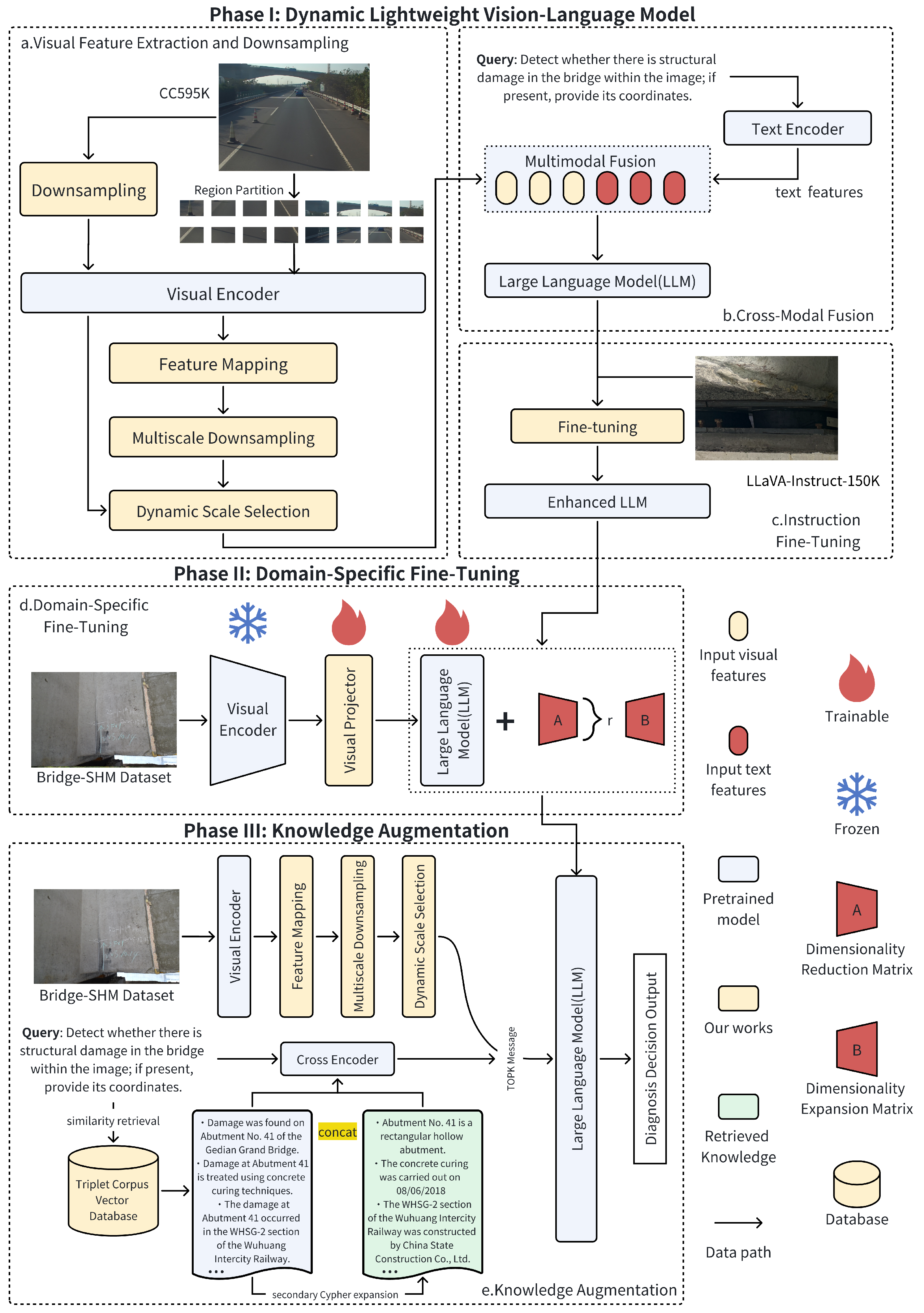

4.4.1. Experiments on the General DL-VLM

- (1)

Comparison Studies

The proposed model demonstrates consistent advantages across different parameter scales. For small-parameter configurations, the model achieves varying degrees of improvement on multiple benchmark tests, indicating that it can effectively enhance performance even under resource-constrained settings. Such gains may stem from architectural optimizations, improved training strategies, or enhanced task-specific adaptability.

In experiments with large-parameter configurations, although the model does not significantly surpass competing methods on all benchmarks, its performance remains comparable to state-of-the-art models, showing that it retains strong competitiveness in high-complexity tasks. This suggests that the proposed method is not only suitable for small-scale models but also maintains stable performance in large-scale settings, further validating its generalization ability and robustness.

Table 3 and

Table 4 report comparative results across multiple benchmarks.

To further highlight the lightweight nature of our framework,

Table 5 provides a comparison of the model sizes and computational requirements of the LLM backbones used in the evaluated systems. Our method is built on the Phi2-2.7B backbone, which contains only 2.7B parameters and requires approximately 4–6 GB of GPU memory for FP16 inference. In contrast, the 7B–8B backbones used by large-scale baselines (e.g., Vicuna-7B, Qwen-7B, and Qwen-8B) require 13–16 GB of memory and incur 2.4–3.0× higher FLOPs per token.

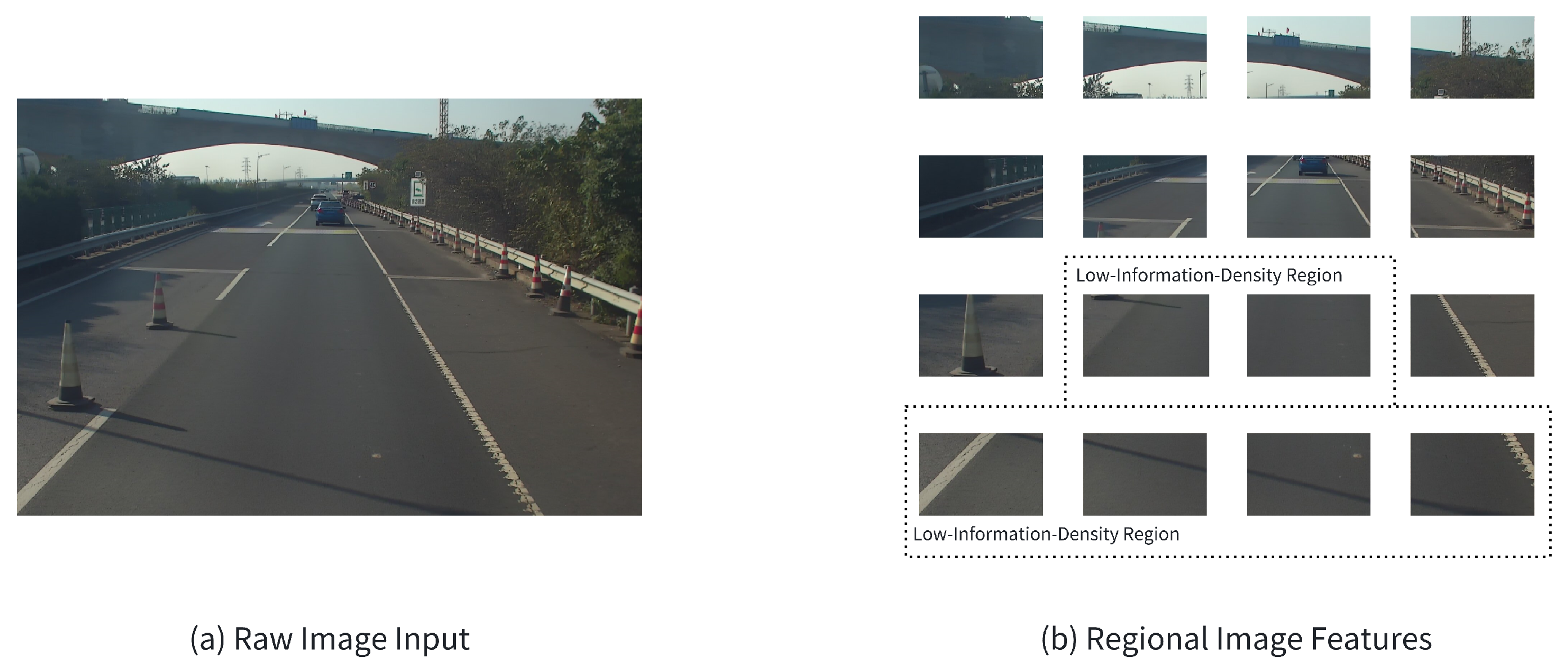

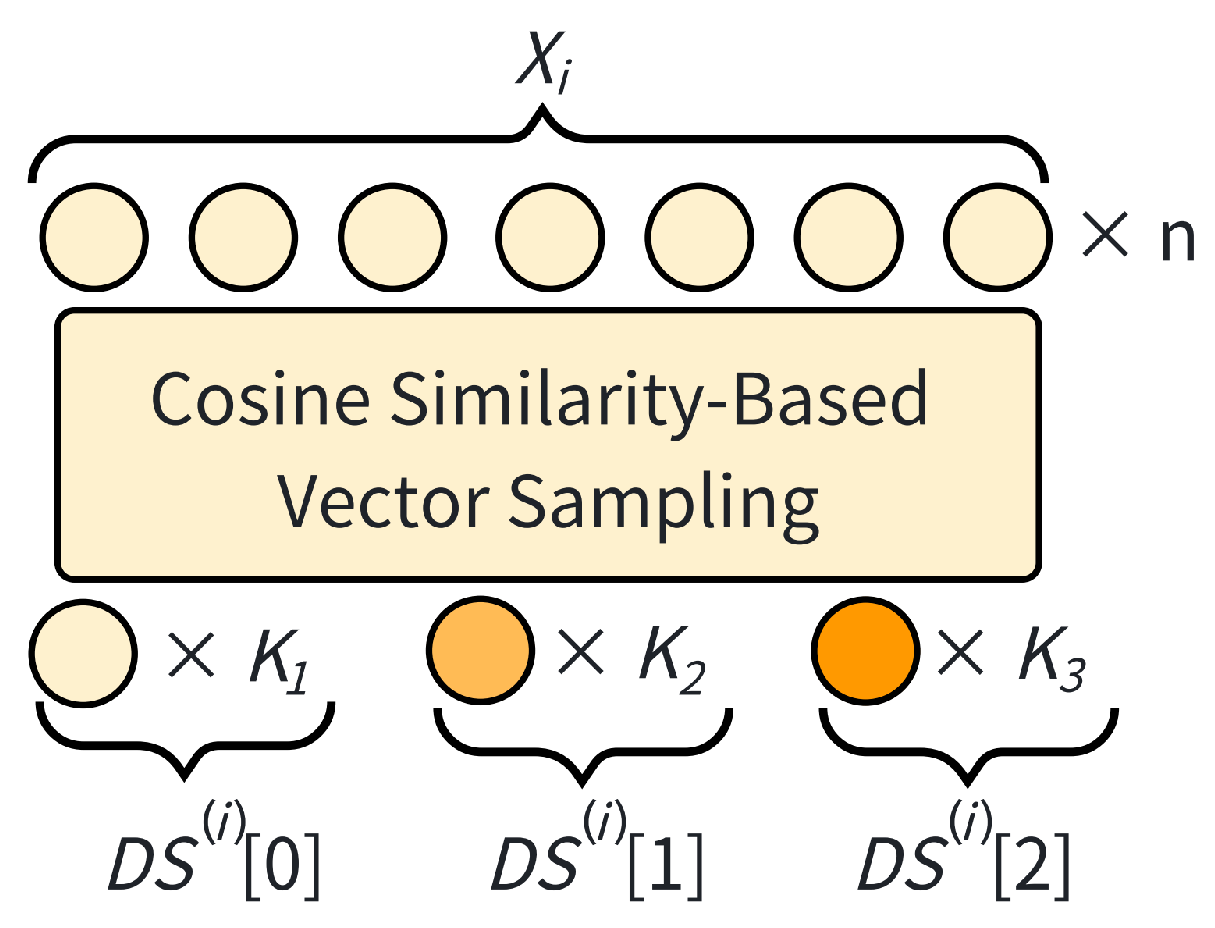

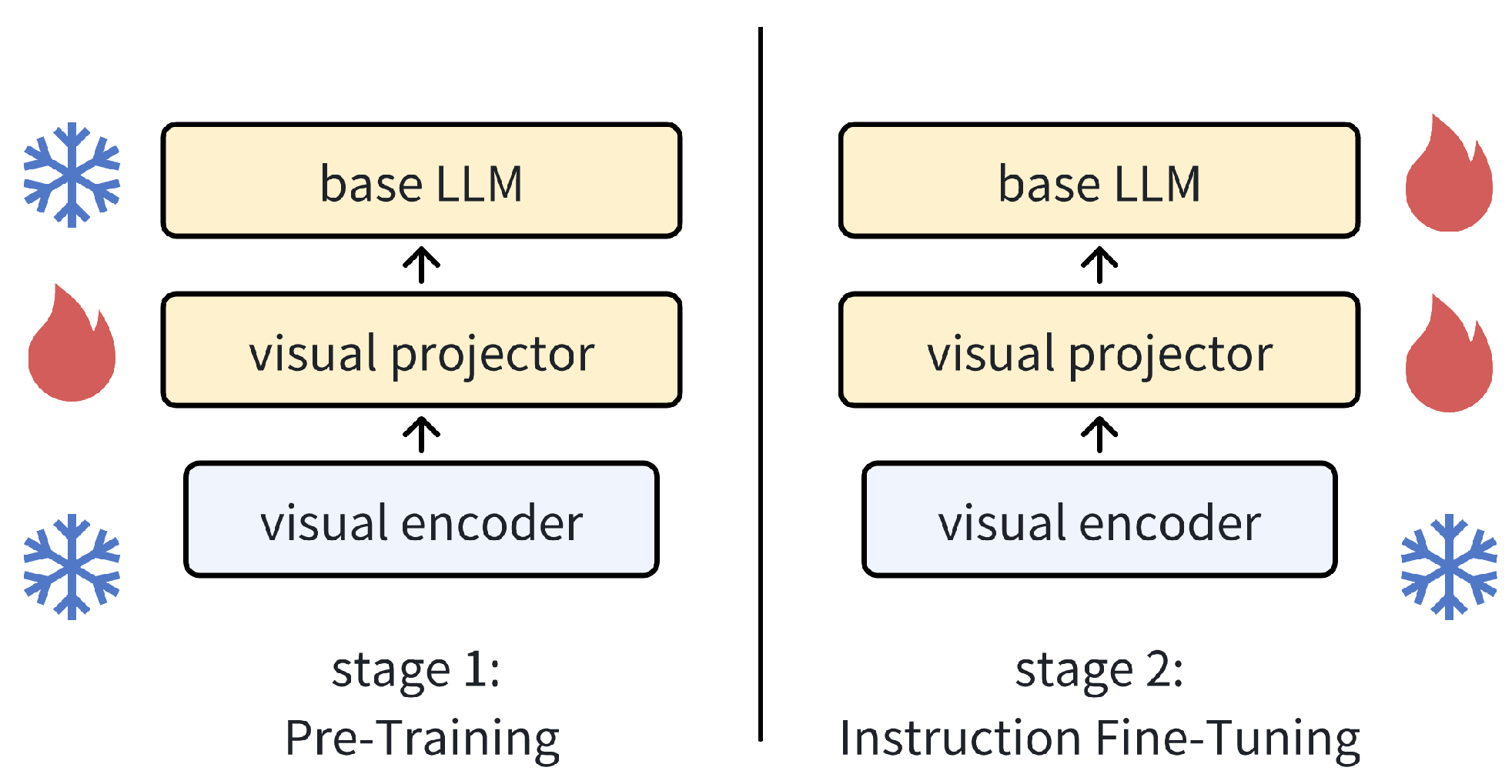

This substantial reduction in model size directly contributes to lower computation cost, smaller memory footprint, and faster inference, enabling deployment in resource-constrained SHM scenarios. More importantly, the proposed dynamic down-sampling strategy further reduces latency by adaptively selecting an appropriate feature resolution for each input instead of processing all images at a fixed high resolution. By avoiding unnecessary high-resolution encoding when coarse-grained features are sufficient, the model significantly decreases ViT encoder workload while still preserving task-critical visual cues. Combined with the efficient projection design, this adaptive mechanism enables the model to achieve competitive or even superior performance compared to larger LLM-based frameworks, demonstrating that task-relevant visual information can be retained without relying on large model capacity.

The experimental results in

Table 3 and

Table 4 demonstrate that our method achieves a strong balance between accuracy and efficiency across different parameter scales. For small-scale backbones, our model attains competitive or leading performance on several key metrics: SQA = 63.4 (close to the best 65.4 of LLaVA-Phi), VQA = 49.6 (the best among listed small models), GQA = 60.3 (the best), MMB = 58.1 (near the top), and POPE = 86.2 (the best). These results indicate that the proposed dynamic multi-scale down-sampling and similarity-driven token selection effectively preserve task-relevant structural details, which is particularly reflected in the improvements on GQA and POPE. In comparison with MobileVLM and Xmodel-VLM variants, our method consistently improves VQA and GQA, demonstrating superior fine-grained visual–text alignment under constrained model capacity.

For 7B-scale comparisons, our framework remains competitive: although some very large baselines (e.g., mPlugOwl3 and Qwen-VL) achieve higher VQA or SQA scores (VQA up to 69.0 and SQA up to 67.1), our model (SQA = 63.4, VQA = 49.6, GQA = 60.3, MMB = 58.1) delivers comparable GQA and maintains solid performance across tasks while using a substantially smaller LLM. This highlights the efficiency advantages of our dynamic down-sampling strategy—the model is able to approach the reasoning capability of larger systems while requiring significantly fewer computational resources.

- (2)

Ablation Studies

To investigate the contributions of individual components, we conduct a series of ablation studies.

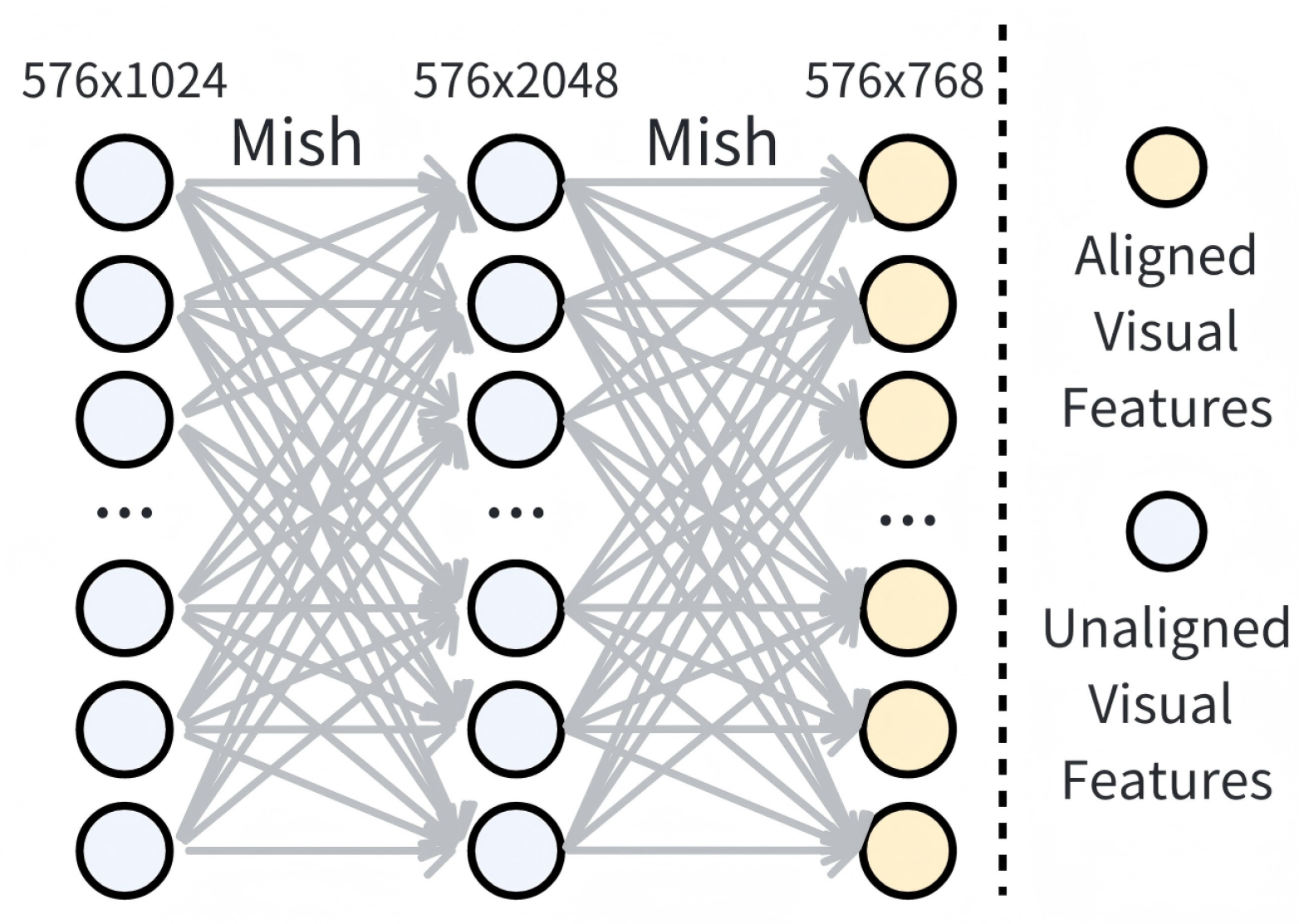

To investigate the impact of the visual projection mechanism on multimodal feature representation, we compare several projection architectures, including Linear, Q-Former, LDP, LDPv2, XDP, and our proposed dynamic down-sampling projection.

Table 6 summarizes the performance across multiple benchmarks. The results indicate that selecting an appropriate projection module significantly enhances cross-modal feature complementarity, which directly improves downstream task performance. While Q-Former demonstrates higher accuracy in image-text matching tasks, our dynamic down-sampling projection consistently achieves superior results on SQA, VQA, GQA, and MMB, highlighting its effectiveness in preserving task-relevant visual information under resource-constrained settings.

Table 7 reports results using different backbone LLMs while keeping the vision encoder and projector fixed. Larger LLMs significantly improve overall performance, indicating that scaling the language model is an effective strategy when computational resources allow.

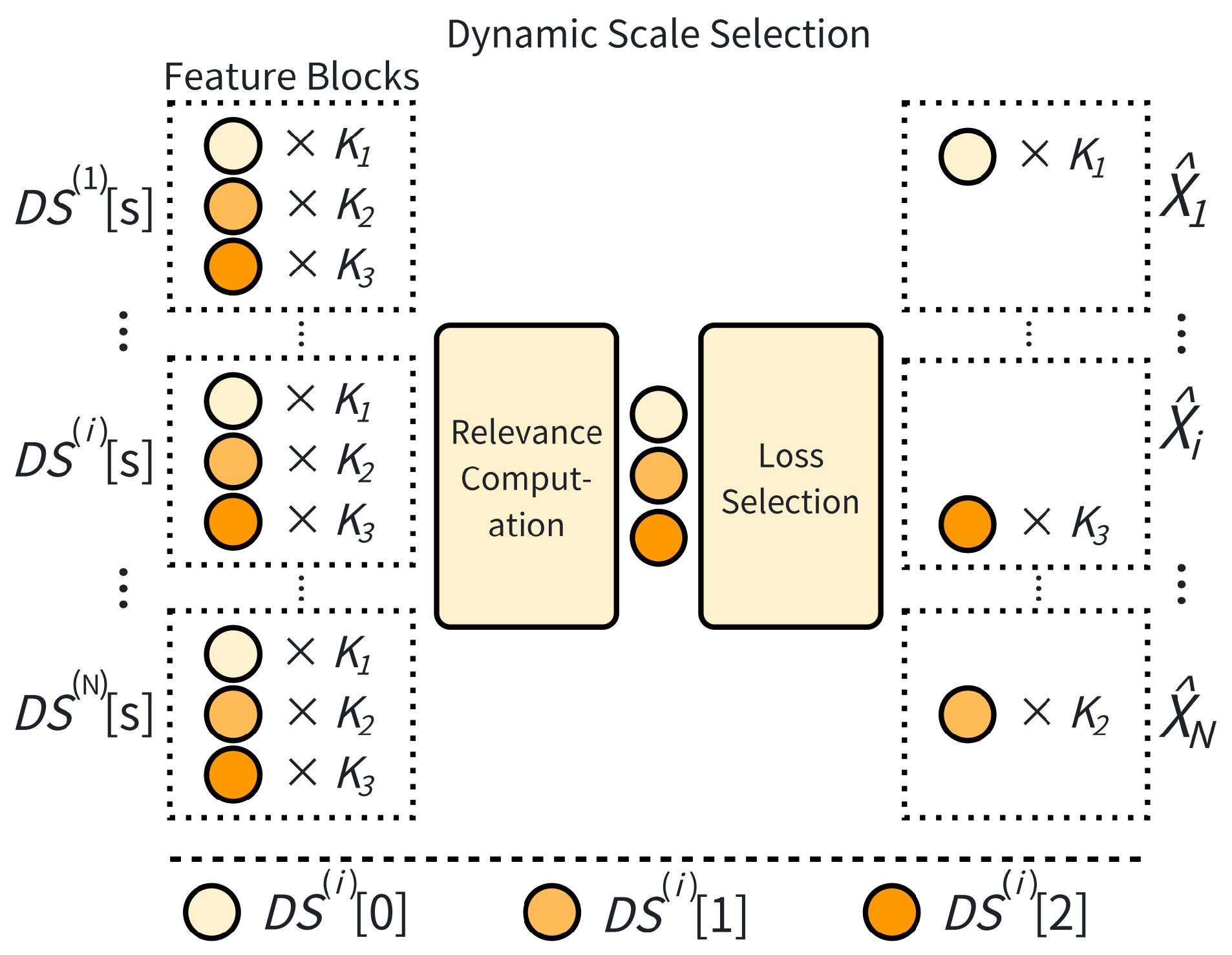

Table 8 compares different scale configurations. The combination

yields the best performance, especially on GQA, MMB and POPE, suggesting an effective balance between feature detail preservation and semantic abstraction.

Finally, we evaluate the impact of balancing loss weights (

Table 9). Results show that very small weights fail to guide the sampling module effectively, while an intermediate setting 0.1 achieves the best trade-off, leading to improvements in VQA and GQA. Excessively large weights, however, interfere with the main task, limiting further gains.

The ablation experiments demonstrate the effectiveness and necessity of the proposed components. From

Table 6, the dynamic down-sampling visual projection consistently outperforms alternative architectures, confirming its ability to preserve task-relevant visual features while enhancing cross-modal alignment. From

Table 7, using a larger backbone LLM significantly improves overall performance, showing that language model capacity directly influences multimodal reasoning capability. From

Table 8, the multi-scale down-sampling configuration

achieves the best trade-off between preserving fine-grained structural details and abstracting semantic information, particularly benefiting GQA and POPE. Finally, from

Table 9, tuning the loss weight is critical for guiding the dynamic sampling module: an intermediate value (0.1) provides the optimal balance, improving task performance without destabilizing the main objectives. Overall, these studies confirm that each individual component contributes to the efficiency and accuracy of the proposed framework, and their combined design enables strong performance under both small- and large-scale settings.

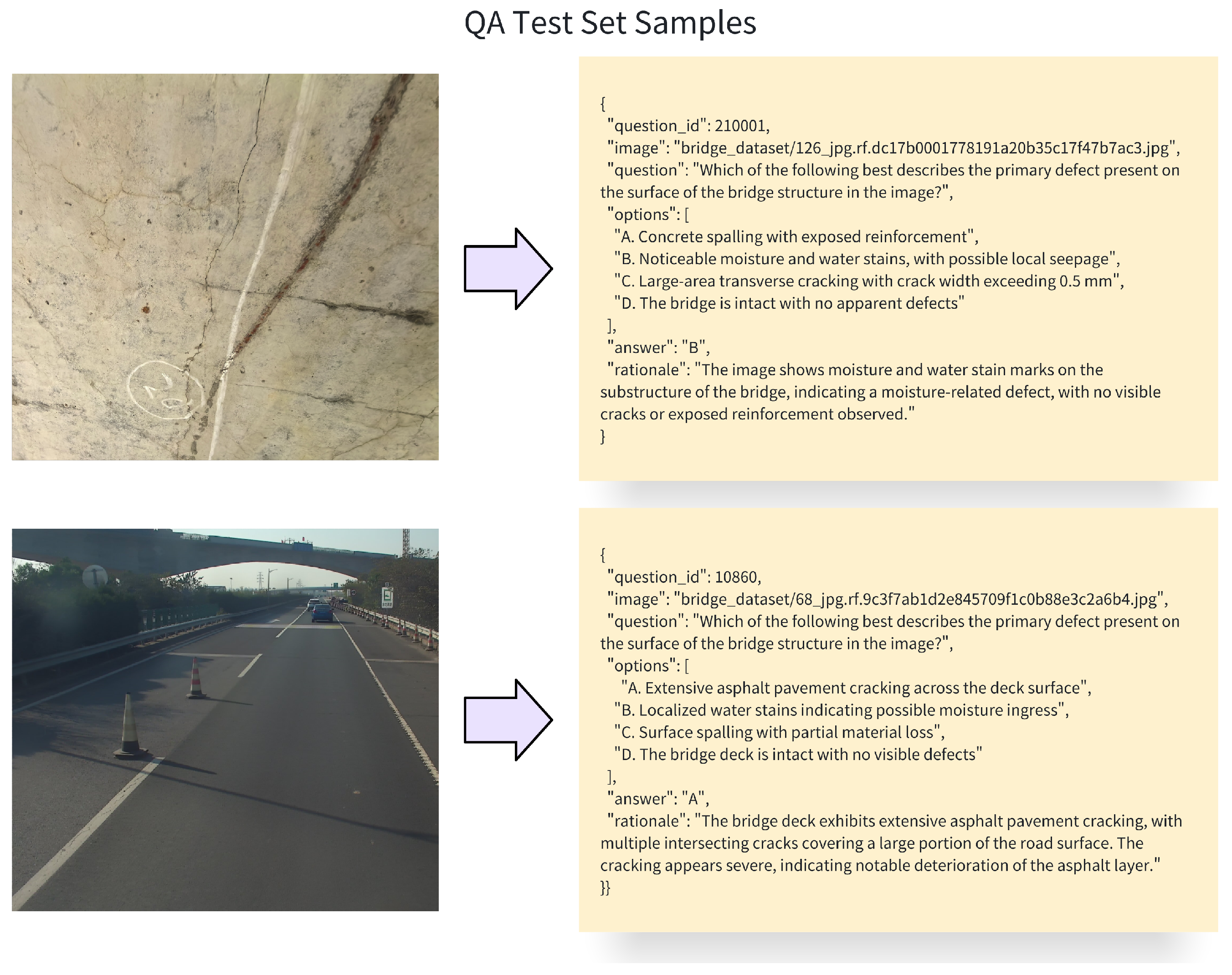

4.4.2. Experiments of Domain-Specialized Fine-Tuning

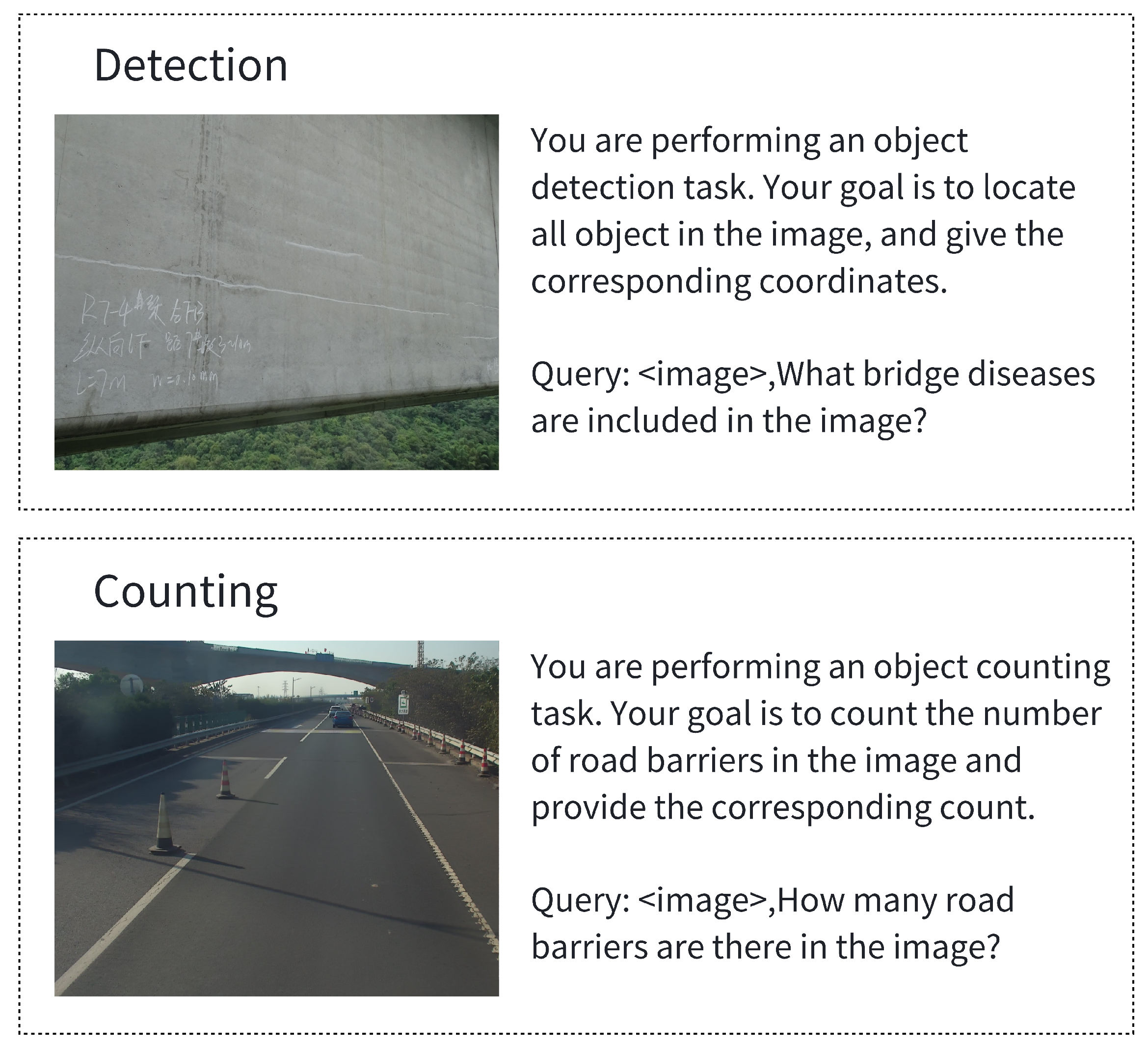

To verify the effectiveness of the fine-tuning strategies, we compare different visual projection mechanisms and parameter-efficient tuning methods on the test set. The results are summarized in

Table 10 and examples of the QA task are presented in

Figure 10. Here,

Linear denotes a simple linear visual projector,

DSFD refers to the dynamic sampling module proposed in

Section 3.2, and

LoRA and

QLoRA represent the two parameter-efficient tuning techniques adopted in this module. QLoRA extends LoRA by incorporating quantization to further reduce storage and computational cost.

The results indicate that compared with the linear projector, the dynamic sampling module consistently improves performance across all three bridge-related tasks.

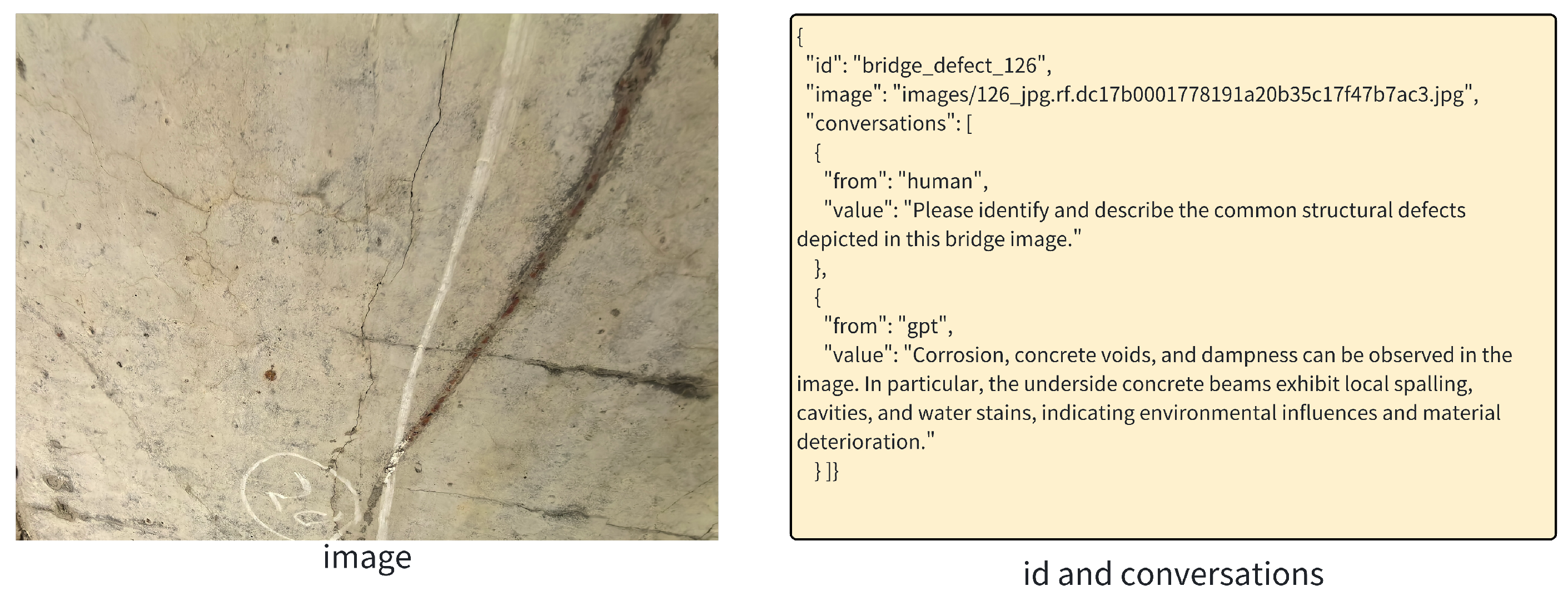

To further analyze the differences across image categories, we separately evaluate the model on construction-site images, surface-defect images, and structural-inspection images. The results show that the most significant improvements appear in surface defect and structural inspection images, where the average Top-1 accuracy increases from 43.7% and 48.6% before fine-tuning to 69.3% and 68.5% after fine-tuning.

Surface defect images often contain high–semantic-density patterns such as cracks, corrosion, and spalling. These details are difficult for general vision models to recognize, as such defects rarely appear in large-scale pretraining corpora.

In contrast, construction-site images already exhibit relatively good baseline accuracy prior to fine-tuning. This is likely because the vision encoders used in mainstream VLMs (e.g., CLIP in LLaVA) are pretrained on large-scale datasets such as LAION-400M, which contain many images with labels related to construction machinery, engineering scenes, and urban infrastructure. These images share semantic overlap with construction-site scenarios, enabling decent recognition without domain-specific fine-tuning.

However, bridge defect images (e.g., cracks, delamination, moisture, hollowing) appear very infrequently in open-source pretraining datasets and therefore belong to “rare semantic categories.” As a result, domain-specific fine-tuning yields substantial improvements for such images.

Finally, although QLoRA significantly reduces memory and computation, the quantization process may introduce accuracy loss—particularly for tasks requiring fine-grained semantic precision, such as defect recognition and structural analysis—resulting in slightly lower performance compared with LoRA.

4.4.3. Experiments on Knowledge Augmentation

- (1)

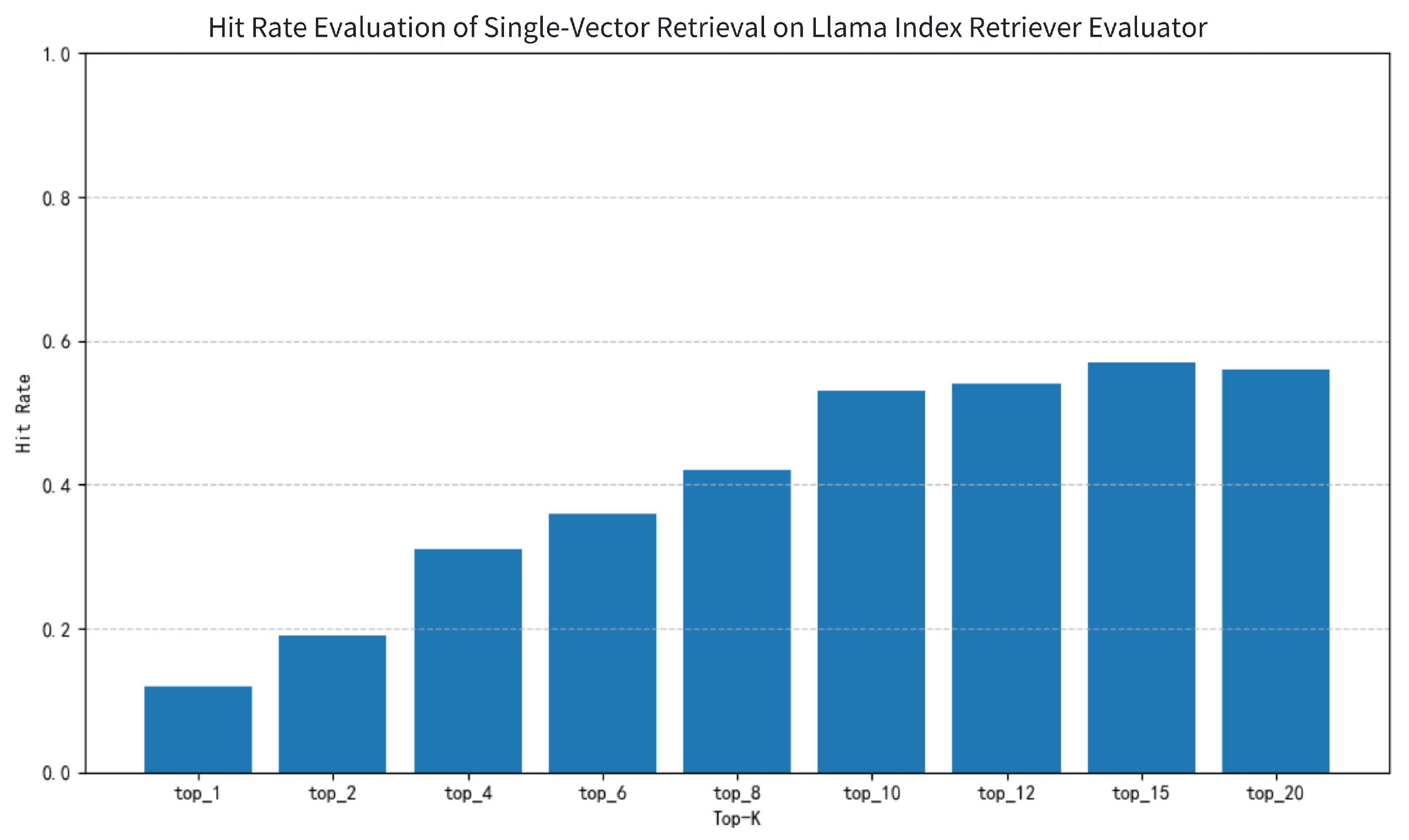

Single-Vector Retrieval

In the single-vector retrieval task, the retrieval model demonstrates a relatively stable Hit Rate under the Llama Index evaluation framework, as shown in

Figure 11. The results indicate that as Top-

K increases, the Hit Rate generally rises: it reaches 0.12 at Top-1, gradually increases to 0.57 at Top-15, and slightly decreases to 0.56 at Top-20, reflecting the positive impact of expanding the retrieval range. However, the improvement is not linear; the temporary drop at Top-12 suggests that the model may introduce ranking interference or redundant results in some samples, limiting further Hit Rate improvement.

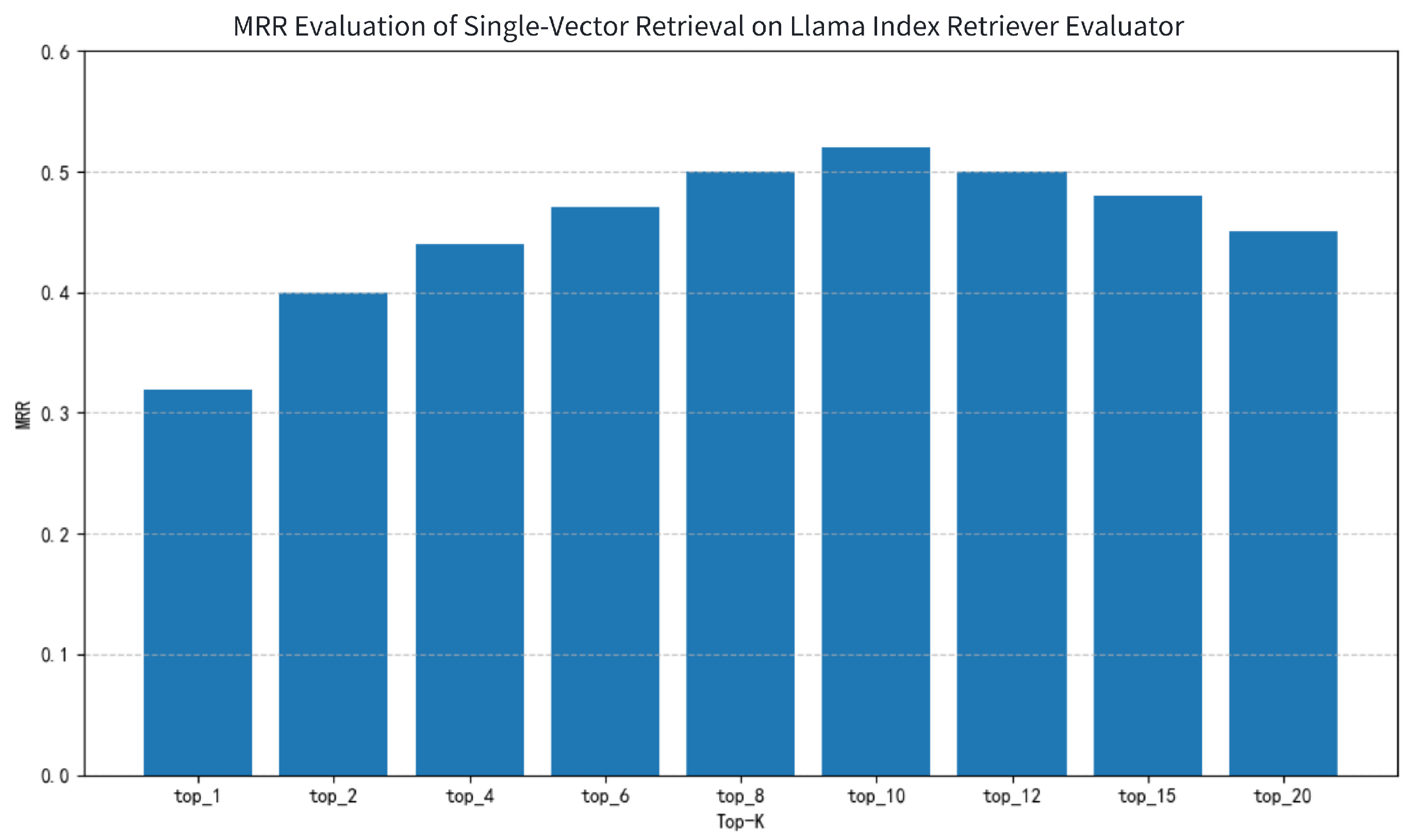

The MRR evaluation, illustrated in

Figure 12, shows that the DPR model exhibits strong top-ranked retrieval capability, reaching 0.32 at Top-1 and peaking at 0.52 at Top-10. This indicates that the model can rank correct documents high for most queries. Although MRR slightly drops after Top-12, it remains above 0.45 overall, demonstrating stable ranking precision even as Top-

K increases. This trend confirms the practical usability of the DPR model in semantically dense matching tasks, especially for downstream tasks with high ranking quality requirements.

- (2)

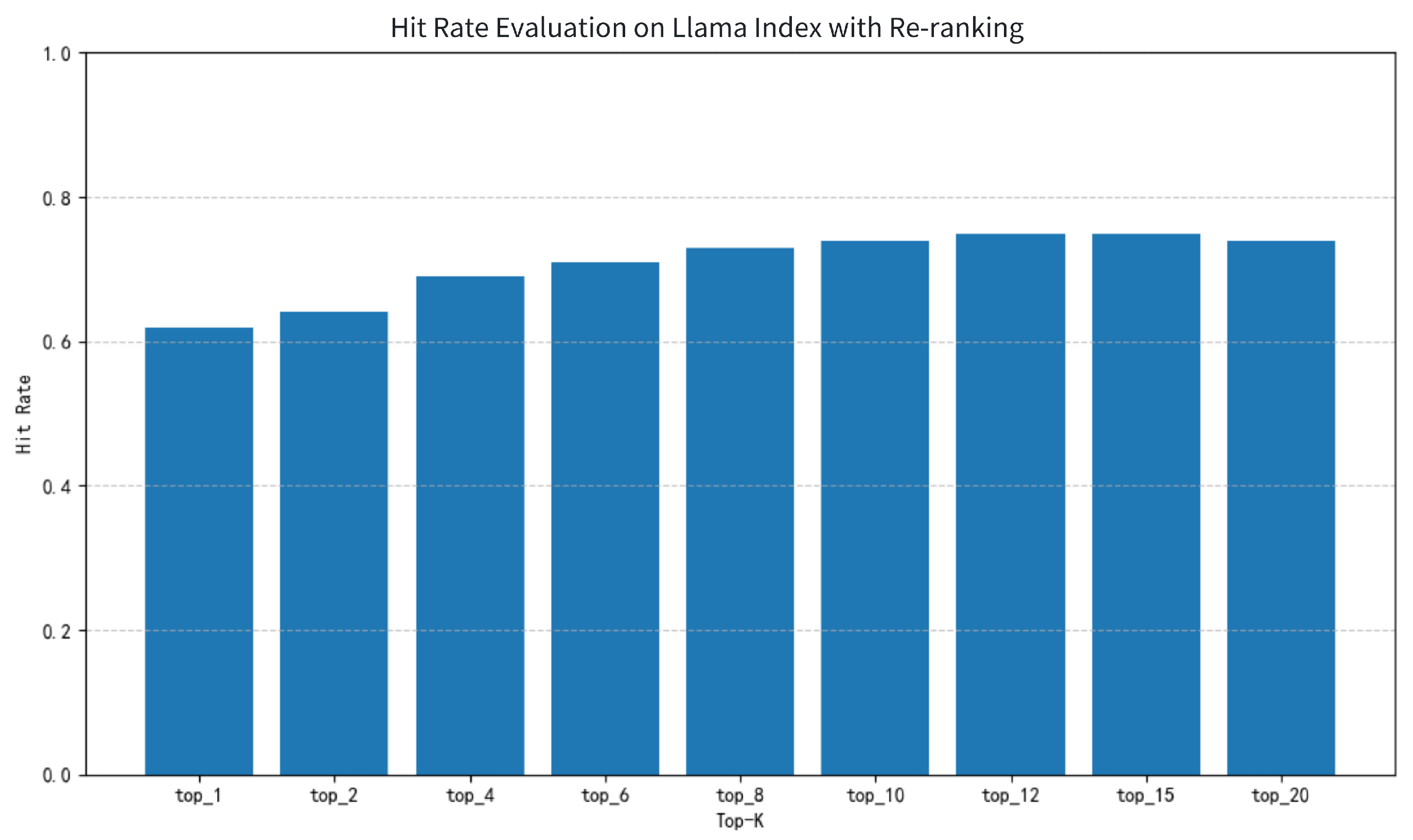

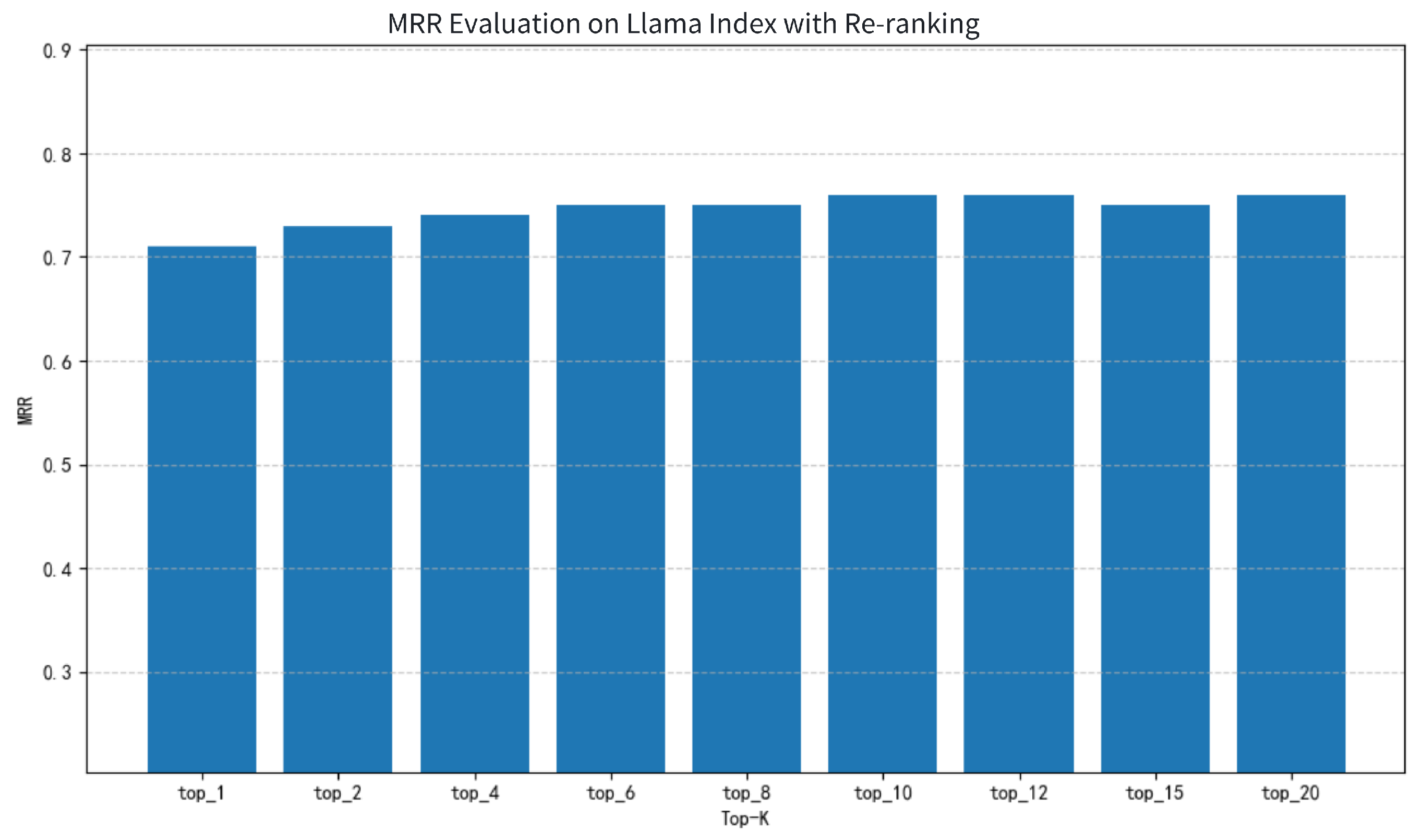

Re-ranking Model

After initial single-vector retrieval, a re-ranking model is applied to refine the ranking of retrieved results. With the re-ranking module added, the Hit Rate under Llama Index is significantly enhanced, as shown in

Figure 13. The overall curve becomes steeper and more stable compared with the baseline. Top-1 Hit Rate increases to 0.15, indicating improved first-position recall. As Top-

K grows, the Hit Rate steadily rises, reaching 0.58 at Top-10 and peaking at 0.65 at Top-20, reflecting the Reranker’s effectiveness in reducing non-relevant documents and improving the discrimination of high-quality candidates. Overall, the two-stage retrieval strategy achieves a better balance between retrieval breadth and precision.

For MRR, the introduction of the re-ranking model significantly improves ranking quality, as shown in

Figure 14. Top-1 MRR reaches 0.38, noticeably higher than the baseline without re-ranking, and peaks at 0.56 at Top-10. This demonstrates that the model effectively ranks correct results higher. These improvements highlight the Reranker’s advantage in fine-grained semantic understanding and its contribution to first-position recall in complex document retrieval tasks. Together with the Hit Rate enhancement, this shows that the Reranker substantially improves retrieval accuracy on top of DPR, making it a key component for high-performance retrieval systems.

- (3)

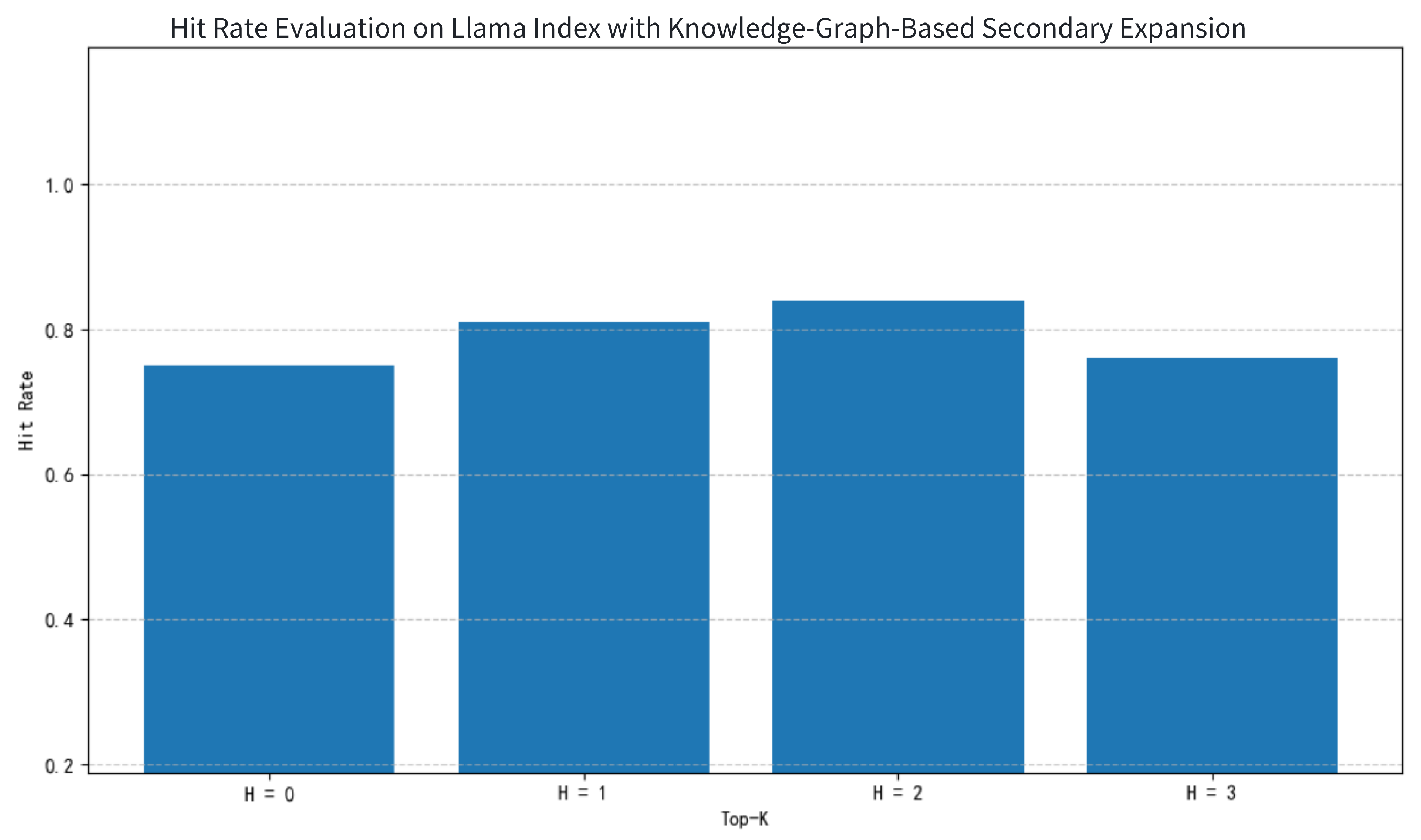

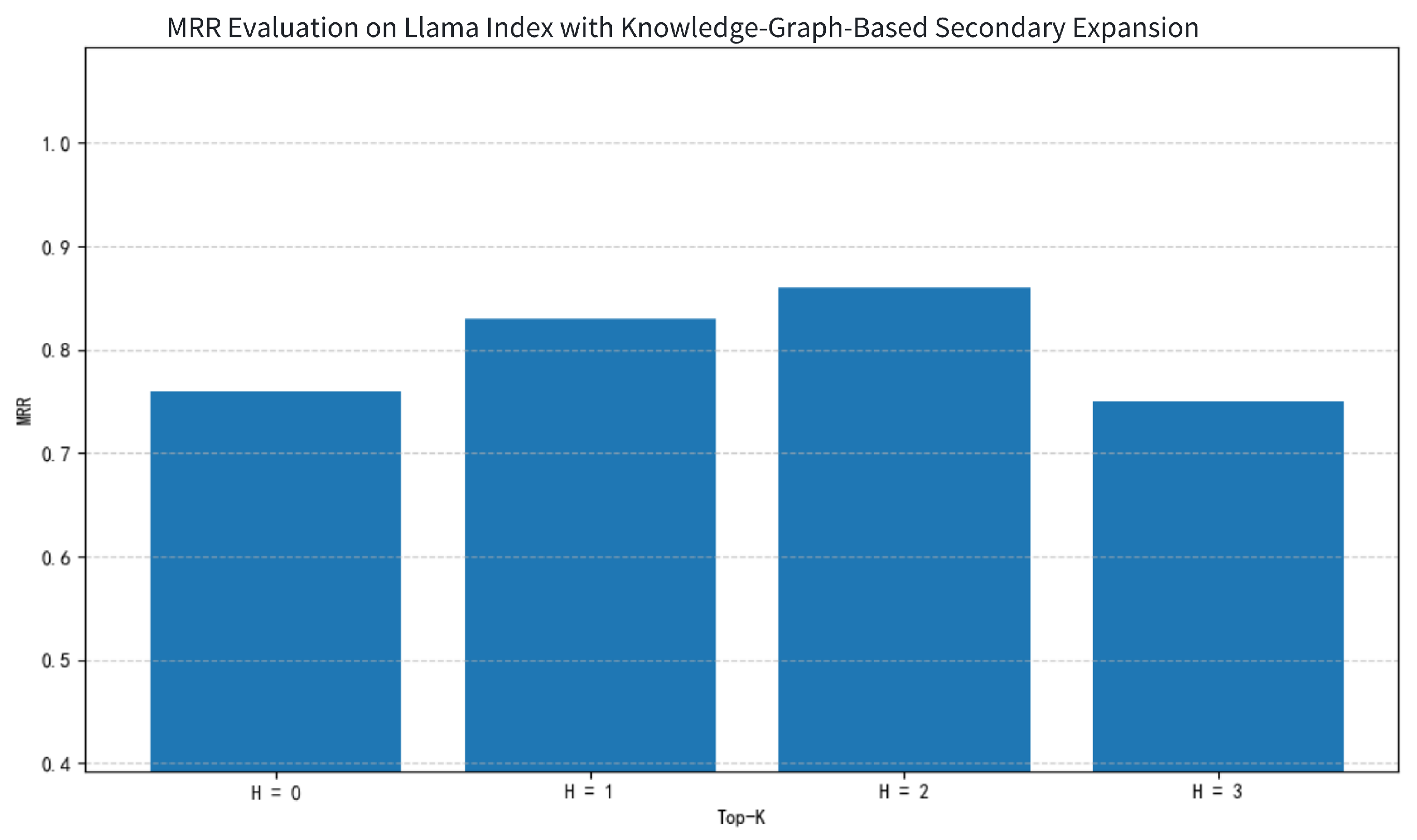

Knowledge-Graph-Based Secondary Expansion

After introducing semantic expansion via a knowledge graph, the experimental results are shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, indicating overall Hit Rate improvement, particularly in the one-hop and two-hop expansion stages. Compared with vector retrieval + re-ranking alone, adding one-hop knowledge-graph expansion allows the system to better associate semantically related concepts, with Hit Rate increasing from 0.75 to 0.81, and two-hop expansion further improving it to 0.84. This demonstrates that moderate semantic expansion helps capture deeper related information, enhancing the system’s understanding and recall of complex queries. At this stage, the knowledge graph effectively “extends semantic coverage,” which is particularly useful for retrieval tasks involving entity substitution, concept variation, or indirect reference. MRR trends similarly improve, especially in one-hop and two-hop expansions, indicating that knowledge-enhanced semantic representations not only improve recall but also significantly optimize ranking positions for relevant documents.

However, performance drops markedly after three-hop expansion, with Hit Rate returning close to the original vector retrieval + re-ranking level, and MRR also declining. This indicates that excessive expansion introduces semantic dilution and potential ranking interference. The degradation trend demonstrates that too many additional entities and noisy information can disrupt effective ranking and matching, diluting the semantic focus of the original query. Overall, the system exhibits a “rise-then-fall” trend with increasing expansion hops, suggesting that knowledge-graph expansion should be controlled within a reasonable range to maintain a balance between semantic relevance and information density, which is crucial for enhancing retrieval system performance.